Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Stenge, Csaba B. 2019. Forgotten Heroes: Aces of The Royal Company. 438 PP

Uploaded by

Jerome EncinaresOriginal Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Stenge, Csaba B. 2019. Forgotten Heroes: Aces of The Royal Company. 438 PP

Uploaded by

Jerome EncinaresCopyright:

Available Formats

Szentkirályi, Endre. “Stenge, Csaba B. 2019.

Forgotten Heroes: Aces of the Royal Hungarian Air Force in the

Second World War. London: Helion & Company. 438 pp. ” Hungarian Cultural Studies. e-Journal of the American

Hungarian Educators Association, Volume 13 (2020) DOI: 10.5195/ahea.2020.411

Stenge, Csaba B. 2019. Forgotten Heroes: Aces of the Royal

Hungarian Air Force in the Second World War. London: Helion &

Company. 438 pp.

Reviewed by Endre Szentkirályi, Nordonia Hills City Schools

In air force circles, an "ace" is a pilot who is credited with at least five enemy kills. Why

should aficionados care about Hungary’s Air Force during the Second World War, puny by

comparison to other European countries? Quite simply, because the number of aces from

Hungary are proportionally quite impressive. Dwarfed by countries like Germany, Finland, the

U.S.A., and Norway, which had twenty-nine aces per million inhabitants (c. 1939), twenty-four

aces, nine aces, and seven aces per million, respectively, Hungary nevertheless produced thirty-

eight aces with a population of approximately nine million. When compared to countries two to

five times its size, its proportional output of aces of about four per million inhabitants still beats

Italy, Poland, and Romania (two-and-a-half to three aces per million inhabitants). In some sense,

no less of an achievement is the work of Hungarian historian Csaba B. Stenge, who devoted the

past two decades to researching the life stories of every single Hungarian ace. Forgotten Heroes:

Aces of the Royal Hungarian Air Force in the Second World War is the product of his meticulous

research, and this 438 page book is no less of a feat than flying a fighter aircraft during wartime:

both require concentration, attention to detail, creativity, and persistence against all odds.

The book under review here is an updated translation of Stenge’s 2016 edition of

Elfelejtett hősök ['Forgotten Heroes']. Somewhat smaller in size and with black and white versus

color pictures in the original Hungarian version published by Zrinyi Kiadó, this new and

improved 2019 edition published by London-based Helion & Company is a worthwhile addition

to military history scholarship. With two Forwards, one by János Mátyás, an actual ace, written

for the 2016 Hungarian edition, and a second one written by Dezső Szentgyörgyi Jr, the son of

the top scoring Hungarian ace, the book’s main feature is its biographies of all thirty-eight

Hungarian aces, with extended summaries of their careers and detailed descriptions of their air

combats. Forgotten Heroes is Stenge’s second English-language monograph on Royal

Hungarian Air Force history, the first being Baptism of Fire (2013, also by Helion & Company).

As such, Stenge’s works are situated among Frank Olynyk’s Stars & Bars, a historical

monograph on American aces, and Mihail Bikov’s study of Soviet flying aces, Sovjetskie Asy

1941-1945 Pobedy Stalinskih. Not only is this new book an interesting read, but it also contains

extremely useful supplementary material, such as air-combat tactics and methods, decorations,

szentkiralyi@nordoniaschools.org

New articles in this journal are licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

This journal is published by the University Library System of the University of Pittsburgh as part of its

D-Scribe Digital Publishing Program and is cosponsored by the University of Pittsburgh Press

ISSN 2471-965X (online)

Szentkirályi, Endre. “Stenge, Csaba B. 2019. Forgotten Heroes: Aces of the Royal Hungarian Air Force in the

Second World War. London: Helion & Company. 438 pp. ” Hungarian Cultural Studies. e-Journal of the American

Hungarian Educators Association, Volume 13 (2020) DOI: 10.5195/ahea.2020.411

comparative ranks, abbreviations, explanations and listings of units, and useful explanations of

military concepts, including the vastly differing criteria that various countries used to award

enemy kills. The only fault of the book is its lack of an index of names.

The compelling stories of air combat and subsequent life journeys of all of the aces,

however, are the work of painstaking research, despite an appalling lack of official

documentation in Hungarian government archives. This research is useful in and of itself, but it

is doubly impressive because of the lengths to which Stenge had to go to acquire and verify the

facts in these stories; almost all of the records of the Royal Hungarian Air Force during the

Second World War were destroyed, and most of its officer corps was persecuted during

communist times, so Stenge had to travel extensively to unearth these facts. Not only did he visit

government and military archives in Russia, Germany, the United States, and Hungary, but he

also found living relatives of many of the aces, tracking them down wherever they may have

ended up after the war, including North and South America.

But let us look at some of the stories recounted by Stenge. Categorized into chapters by

aces with more than twenty victories, those with more than ten, and those with five to nine

confirmed kills, Stenge gives the reader details based not only on archival and family research,

but he also interviewed the families of their victims and the families of their foes. When one

reads about American and Soviet pilots who shot down these aces or who were shot down by

them, one cannot help but admire the objectivity and empathy of Stenge’s work. Filled with 350

rare photographs and images provided by the families on both sides of the war, the book gives a

window to a previously unknown aspect of Hungary’s military history. Some of the stories are

heroic, such as one where Miklós Kenyeres rescued György Debrődy, a fellow pilot whose plane

had just been shot down. Kenyeres landed next to the plane in knee-deep snow amid a hail of

bullets; then, sitting the injured pilot into his own plane and himself in his lap, they flew home,

with one controlling the pedals and the other the manual controls in a cockpit designed for a

single pilot. Others are funny, like the picture of pilot Mátyás Lőrincz bathing in Lake Balaton,

sitting in a boat modified from a droppable extra fuel tank of a P-51 Mustang airplane. And some

are tragic, such as a bombing by Soviet aircraft during ace Lajos Buday’s funeral in March of

1945, which killed a ground crew member in attendance as well as destroyed Buday’s coffin.

And all of the detailed descriptions of the thirty-eight Hungarian aces are enhanced by numerous

contemporary maps and drawings unearthed by Stenge’s research.

Another facet besides the fascinating stories that keeps this book from being a dry

military history is that each biography contains at least a paragraph of the pilots’ postwar lives.

Some stayed in Hungary and continued as pilots in the new socialist air force until they were

imprisoned by the communist authorities. Others emigrated to Western Europe, to Canada, to the

United States, or to countries in South America, many becoming agricultural pilots and living out

the rest of their lives in these new homelands. Interestingly enough, many of their sons and

grandchildren eventually also became pilots. Striking also is that Stenge was able to interview

many of these families, wherever in the world the pilots ended up. And in the most noteworthy

example of turning swords into ploughshares, a Hungarian ace, after fleeing to the United States,

became friends with many of his former adversaries, the former U.S. fighter pilots. But the most

surprising fact of the book is that one Hungarian ace, László Dániel, ninety-seven years old, of

Chile, was still alive at the time of its writing. These forgotten heroes, for forty-four years

outcast as enemies of the state in Hungary, as imperialist reactionaries unfit to build the glorious

socialist homeland, are no longer forgotten, due in no small part to Csaba B. Stenge’s meticulous

work.

256

You might also like

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)From EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Rating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (121)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryFrom EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (231)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceFrom EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (588)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaFrom EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (266)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItFrom EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (838)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerFrom EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (271)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingFrom EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (400)

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeFrom EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (5794)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyFrom EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (2259)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeFrom EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (537)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreFrom EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (1090)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersFrom EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (345)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnFrom EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (234)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesFrom EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (821)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceFrom EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (895)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaFrom EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (45)

- 16 Flight Emergency Landings Proving Flat Earth - Eddie Alencar - 2019Document173 pages16 Flight Emergency Landings Proving Flat Earth - Eddie Alencar - 2019icxc nika100% (5)

- Aircraft Aircraft Structure and Terminology: VocabularyDocument6 pagesAircraft Aircraft Structure and Terminology: VocabularyОксана ПаськоNo ratings yet

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureFrom EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (474)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealFrom EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (74)

- Air International-January 2021 PDFDocument100 pagesAir International-January 2021 PDFCristian Paraianu100% (1)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)From EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Rating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (98)

- E-Ticket Itinerary Receipt 96857973 (Iqmal)Document11 pagesE-Ticket Itinerary Receipt 96857973 (Iqmal)Choon Zhe ShyiNo ratings yet

- 737 300 Systems Study Guide PDFDocument34 pages737 300 Systems Study Guide PDFDiego Pazmiño100% (3)

- ETOPS - Ask Captain LimDocument18 pagesETOPS - Ask Captain LimtugayyoungNo ratings yet

- Air Regulation Dgca Question PaperDocument8 pagesAir Regulation Dgca Question PaperprachatNo ratings yet

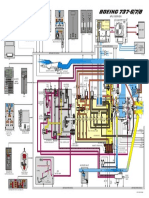

- B737NG - 49 00 A3 01 PDFDocument1 pageB737NG - 49 00 A3 01 PDFMuhammed MudassirNo ratings yet

- Emerging Nationalism by Rosalinas Hist3bDocument3 pagesEmerging Nationalism by Rosalinas Hist3bJerome EncinaresNo ratings yet

- Objective: AffiliationsDocument3 pagesObjective: AffiliationsJerome EncinaresNo ratings yet

- DocumentDocument18 pagesDocumentJerome EncinaresNo ratings yet

- Output IN Bicol Literature: BY: Maricar A. Rosalinas History 2B Submitted To: Mr. Sammy P. PitoyDocument6 pagesOutput IN Bicol Literature: BY: Maricar A. Rosalinas History 2B Submitted To: Mr. Sammy P. PitoyJerome EncinaresNo ratings yet

- Assignment #1Document23 pagesAssignment #1Jerome EncinaresNo ratings yet

- Chapter 2Document9 pagesChapter 2Jerome EncinaresNo ratings yet

- Spanish History, Religion and GovernmentDocument123 pagesSpanish History, Religion and GovernmentJerome EncinaresNo ratings yet

- Philippine AssemblyDocument3 pagesPhilippine AssemblyJerome EncinaresNo ratings yet

- Rosalinas, Maricar A. Ba History3BDocument5 pagesRosalinas, Maricar A. Ba History3BJerome EncinaresNo ratings yet

- Forgotten Heroes, Who Are Remembered Forever: Gábor Ferenc KissDocument3 pagesForgotten Heroes, Who Are Remembered Forever: Gábor Ferenc KissJerome EncinaresNo ratings yet

- Economy and SocietyDocument2 pagesEconomy and SocietyJerome EncinaresNo ratings yet

- Final Chapter 2Document9 pagesFinal Chapter 2Jerome EncinaresNo ratings yet

- Act 2. Reflective EssayDocument2 pagesAct 2. Reflective EssayJerome EncinaresNo ratings yet

- Lifeboat StationDocument6 pagesLifeboat StationJerome EncinaresNo ratings yet

- Surface Safety: EnhancingDocument44 pagesSurface Safety: Enhancingdionicio perezNo ratings yet

- Check My TripDocument2 pagesCheck My TripSEPESNo ratings yet

- IELTS - Unit 01, Lesson 09 (Simulation Test)Document7 pagesIELTS - Unit 01, Lesson 09 (Simulation Test)AhmedNo ratings yet

- Eticket - DHEDI ANDRI YULIANTO 9902171111413Document2 pagesEticket - DHEDI ANDRI YULIANTO 9902171111413Satria laksana ariNo ratings yet

- Resumen Entrevista Ingles 3 UdeCDocument41 pagesResumen Entrevista Ingles 3 UdeCNicolas GalvezNo ratings yet

- Jumpseat GuideDocument8 pagesJumpseat GuideCarlos DelgadoNo ratings yet

- Veronica Reni Puspita Dps WRNMWM CGK Flight - OriginatingDocument4 pagesVeronica Reni Puspita Dps WRNMWM CGK Flight - OriginatingAnang KoswaraNo ratings yet

- 7 Brave Female ExplorersDocument15 pages7 Brave Female ExplorersWai Lana ButlerNo ratings yet

- M As1 Formative Task: Review Questions: Star Alliance Sky Team OneworldDocument4 pagesM As1 Formative Task: Review Questions: Star Alliance Sky Team OneworldSharlyne PimentelNo ratings yet

- Get Ready For IELTS Listening Pre Intermediate A2 RED 7 12Document6 pagesGet Ready For IELTS Listening Pre Intermediate A2 RED 7 12Mai Phương LêNo ratings yet

- Worksheet 5Document3 pagesWorksheet 5Rohan SinghNo ratings yet

- Air Canada Customer SupportDocument1 pageAir Canada Customer SupportFakharNo ratings yet

- British Airways EmiratesDocument5 pagesBritish Airways Emiratesmubeen yaminNo ratings yet

- Plan Sched 20 Mar 23Document12 pagesPlan Sched 20 Mar 23alwanbagasNo ratings yet

- Moca 003079 1 PDFDocument6 pagesMoca 003079 1 PDFNitinNo ratings yet

- IT Park in GurgaonDocument5 pagesIT Park in Gurgaonanarang2523No ratings yet

- Unit 6Document56 pagesUnit 6Jeirey Bylle Aban MendozaNo ratings yet

- American Airlines Airlines Reservations - Book CHDocument1 pageAmerican Airlines Airlines Reservations - Book CHblackwoodnogayNo ratings yet

- Travel Document For Maallemi - Amel - Olvp8qDocument1 pageTravel Document For Maallemi - Amel - Olvp8qAmalNo ratings yet

- TiketDocument4 pagesTiketYati Narafa SagaLokaNo ratings yet

- Majestic Dash8 Checklists PDFDocument13 pagesMajestic Dash8 Checklists PDFDanielNo ratings yet

- California Wing - Jun 1997Document60 pagesCalifornia Wing - Jun 1997CAP History LibraryNo ratings yet