Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Religious Affiliations and Political All

Religious Affiliations and Political All

Uploaded by

Jovana DimkićCopyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Religious Affiliations and Political All

Religious Affiliations and Political All

Uploaded by

Jovana DimkićCopyright:

Available Formats

Medieval

Jewish, Christian and Muslim Culture

Encounters

in Confluence and Dialogue

Medieval Encounters 13 (2007) 222-242 www.brill.nl/me

Religious Affiliations and Political Alliances in the

Ottoman Succession Wars of 1402-1413

Dimitris J. Kastritsis

University of St Andrews

Abstract

This article examines the complex political alliances that developed during the Ottoman

civil war of 1402-1413. This civil war, which followed Timur’s defeat of the Ottomans at

Ankara and the dismemberment of Bayezid I’s empire, provided an excellent opportunity

for the many Christian powers threatened by the Ottomans to cooperate against them; but

in fact, apart from a failed attempt by Byzantium in 1409, there was little such cooperation.

Instead, the period is noteworthy for the absence of any serious attempt at a crusade, since

the interests of the main Christian powers were often at odds. It is ironic that the only large-

scale alliance involving a wide array of Christian powers was engineered in 1413 by an

Ottoman prince, Mehmed Çelebi (Sultan Mehmed I), who was thereby able to reunite the

Ottoman Empire under his rule. In fact, the story of the Ottoman civil war is one of indi-

vidual power brokers with divided loyalties trying to survive and further the interests of

their constituencies. What brought these people together in 1413 was their opposition to

Mehmed’s rival Musa Çelebi, who had revived Bayezid I’s policies of territorial expansion

and political centralization. While there is no denying the importance of Islam and Chris-

tianity both as faith systems and as rallying calls, the political scene was too complex to allow

faith alone to determine political developments. In such politically fragmented times, the

only way to survive was through shrewd diplomacy and alliance building.

Keywords

Ottoman Empire, Ottoman Interregnum, Ottoman Civil War, Mehmed I, Musa Çelebi,

Süleyman Çelebi, Byzantium, Manuel II Palaiologos, Stefan Lazarević

The Ottoman defeat at Ankara (28 July 1402) came at a critical time for

Christian-Muslim relations. Under Sultan Bayezid I (1389-1402), Otto-

man expansion in southeastern Europe had provoked widespread alarm in

the Christian world. In 1396 the Ottomans had crushed a crusader army

at Nicopolis, and since 1394 Constantinople had been subjected to its first

Ottoman siege. In the years preceding 1402, the situation of the Byzantine

© Koninklijke Brill NV, Leiden, 2007 DOI: 10.1163/157006707X194977

ME 13,2_f5_222-242.indd 222 5/30/07 4:34:04 PM

D. J. Kastritsis / Medieval Encounters 13 (2007) 222-242 223

capital had become so dire that Emperor Manuel II Palaiologos was forced

to leave the city for several years to seek assistance in various Christian

courts. Given this situation, one might have expected news of Timur’s

crushing defeat of the Ottomans at Ankara to have united Christendom in

a new crusade to drive the Ottomans out of Europe. But neither the Otto-

man defeat at Ankara, which resulted in the death of Bayezid I and the

dismemberment of his empire, nor the ensuing decade of Ottoman dynas-

tic wars (the interregnum of 1402-1413) resulted in any significant cru-

sading activity on the part of the Ottomans’ Christian enemies. Instead,

those powers followed a defensive policy of supporting whichever of Bayezid’s

sons appeared to offer them the most advantages and pose the least danger.

It was this policy that made it possible for Mehmed I to reunite the Otto-

man Empire under his rule. In 1413, Mehmed was able to bring together

most of the regional power brokers—both Christian and Muslim—in an

alliance against his brother Musa, who like Bayezid I had pursued an

aggressive agenda of conquest and centralization. In this manner, the

Christian powers of southeastern Europe contributed to their own demise,

for during the reigns of Mehmed I (1413-1421) and Murad II (1421-

1451), the ground was laid for the conquest of Constantinople and the

establishment of the great Ottoman Empire of Mehmed II.

Given the very real threat posed by the Ottomans prior to 1402, how is

it possible to explain the neglect of the crusade during the period 1402-

1413, when the Ottomans were weak and divided? Among the obvious

explanations are the disastrous results of the Crusade of Nicopolis (1396)

and the European disunity of the time, which resulted in conflicting inter-

ests among the powers that might have organized such a crusade.1 To these

should be added also a natural complacency: after 1402 the Ottomans

no longer seemed to pose such a serious threat, and it was hoped that their

civil wars might cause them to self-destruct. However obvious these expla-

nations, the international politics of the period has received little serious

1

See, for example, Aziz S. Atiya, “The Crusade in the Fourteenth Century,” in A History

of the Crusades, ed. K. M. Setton, 6 vols. (Madison: University of Wisconsin Press, 1975),

3:25: “The downfall of the western chivalry on the field of Nicopolis marked the end of any

hope that the Ottoman empire could be destroyed by Christendom, and Turkey was

accepted as a European power. . . . . . . [T]he crusade had become an anachronism.” The

author is exaggerating somewhat when he states that “Turkey was accepted as a European

power” after Nicopolis, but there is little doubt that the defeat had a chilling effect on

European chivalry.

ME 13,2_f5_222-242.indd 223 5/30/07 4:34:06 PM

224 D. J. Kastritsis / Medieval Encounters 13 (2007) 222-242

examination. The present article constitutes a first attempt at tracing the

political alliances of the Ottoman civil war, whose outcome was to have

such serious repercussions for the history of the region. Such an examina-

tion is of value not only because it fills a narrative gap but also because it

contributes to the ongoing debate about the nature of the early Ottoman

state and our understanding of Balkan and Anatolian society in the late

Middle Ages.2 As we will see, during this time of fragmentation and decen-

tralization, political exigencies made it difficult for individual power bro-

kers (including the Ottomans) to reconcile their religious affiliation with

loyalties toward multiple states and constituencies. In such times, flexibility

was a virtue, but one that if carried too far could bring accusations of trea-

son. It was such accusations that led to the downfall of the Ottoman prince

Emir Süleyman in 1411. On the Christian side, the policies of Venice and

other Catholic powers contributed to the animosity many Byzantines felt

toward them on the eve of the conquest of Constantinople. Before explor-

ing these ideas in more detail, it is first necessary to provide some historical

background.

The political scene inhabited by the Ottomans and their neighbors dur-

ing this time was extremely complex. Apart from the Ottomans, the other

major power in the Balkans was Catholic Hungary. However, since 1382

Hungary had also been divided by a major succession struggle, unleashed

by the death of the Angevin King Louis I, who had died without a male

heir. Like the Ottoman succession wars, this struggle for the Hungarian

throne drew in all those who stood to gain or lose from Hungarian suprem-

acy in the region. The de facto king was Sigismund of Luxemburg, a man

who represented the strong central government of Louis I; Sigismund’s

enemies supported a rival contender, Ladislas of Naples, who was the clos-

est blood relation of the deceased Angevin king. In 1401 Sigismund was

briefly imprisoned by his own noblemen, but by 1404 his situation was

improving, so that many of these started to desert Ladislas and join Sigis-

mund’s side. Meanwhile, many local rulers in Croatia, Slavonia, Dalmatia,

and Bosnia had taken advantage of King Louis’s death to throw off their

vassalage to Hungary. At first they supported Ladislas, as did Venice, which

2

For the most recent installments in the debate on Ottoman origins (and detailed biblio-

graphies of the earlier ones), see Cemal Kafadar, Between Two Worlds: The Construction of

the Ottoman State (Berkeley and Los Angeles: University of California Press, 1995); and

Heath Lowry, The Nature of the Early Ottoman State (Albany: State University of New York

Press, 2003). On Ottoman identity, see also Salih Özbaran, Bir Osmanlı kimlig i: 14.-17.

yüzyıllarda Rûm/Rûmi aidiyet ve imgeleri (Istanbul: Kitap, 2004).

ME 13,2_f5_222-242.indd 224 5/30/07 4:34:06 PM

D. J. Kastritsis / Medieval Encounters 13 (2007) 222-242 225

took advantage of the situation to increase its holdings on the Dalmatian

coast. But by 1409, Sigismund was able to take advantage of local divisions

and fear of Venetian expansion to create his own factions, eventually

emerging as the winner.3

It should be noted that the intense phase of the war for the Hungarian

throne coincided exactly with the Ottoman succession wars, which goes a

long way toward explaining why the Christian powers of the area were

unable to take unified action against the Ottomans at this time. But there

were also other important divisions within Latin Europe affecting the cru-

sading movement, such as that within the papacy itself. Crusades were

always dependent on the cooperation of secular powers with the pope,

who alone had the power to proclaim them and grant spiritual rewards to

their participants. At this time, the papacy was divided by the Great Schism

(1378-1417), which meant that there were at any given moment two rival

popes, one in Rome and another in Avignon. Both popes had supported

the Crusade of Nicopolis, but in light of its failure and the struggle for the

Hungarian throne, such unity had become increasingly difficult to pro-

cure. In 1398, during the Byzantine Emperor Manuel II’s visit to western

Europe, the Roman Pope Boniface IX (who supported Ladislas) had

preached a crusade against the Ottomans with little effect; but, in May

1400, for unknown reasons, Rome’s preaching of the crusade was com-

pletely abandoned.4 The only real crusading activity at this time was under-

taken by the French marshal Boucicault, who for this reason has been

called “a one-man crusade.”5 It was also possible to form crusading leagues

when this served the interests of powers threatened by Ottoman expan-

sion, such as the league that came into existence late in 1402, which

included Venice, Genoa, Rhodes, Naxos, and Chios.6 But such leagues

3

See John V. A. Fine, The Late Medieval Balkans: A Critical Survey from the Late Twelfth

Century to the Ottoman Conquest (Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press, 1987), 395-8;

Émile G. Léonard, Les Angevins de Naples (Paris: Presses universitaires de France, 1954);

Alessandro Cutolo, Il re Ladislao d’Angiò-Durazzo (Milan: U. Hoepli, 1936); and

K. M. Setton, The Papacy and the Levant, 1204-1571, 4 vols. (Philadelphia: American

Philosophical Society, 1976), 1:342.

4

Deno Geanakoplos, “Byzantium and the Crusades, 1354-1453,” in A History of the

Crusades, 3:85-6; Setton, The Papacy and the Levant, 1:370.

5

Setton, The Papacy and the Levant, 1:371.

6

For this league which appears in Emir Süleyman’s Treaty of 1403, see E. A. Zachari-

adou, “Süleyman Celebi in Rumili and the Ottoman Chronicles,” Der Islam, 60 (1983):

268-96, esp. 274.

ME 13,2_f5_222-242.indd 225 5/30/07 4:34:07 PM

226 D. J. Kastritsis / Medieval Encounters 13 (2007) 222-242

were generally short-lived, especially when they included traditional ene-

mies like Venice and Genoa.

Let us now turn to the Ottomans after their defeat in 1402.7 Following

the Battle of Ankara, a large number of people fled to the straits and

attempted to cross to Europe to escape the depredations of Timur’s armies.

These included Christians and Muslims, peasants and soldiers, as well as

Ottoman princes and magnates. The influx caused problems because

members of the crusading league were prohibited from assisting Muslims,

but nevertheless the captains of many Venetian and Genoese ships sought

to profit by ferrying people across for a fee regardless of their religion.8 Two

sons of the captured Sultan Bayezid were able to cross to the main Otto-

man naval base of Gallipoli: Emir Süleyman and Isa. Süleyman was clearly

the more powerful of the two, and in the company of his advisers and the

frontier lords of the Balkans (Rumili) he immediately began peace nego-

tiations with Byzantium, Venice, Genoa, and other Christian powers.

These negotiations were delayed by the absence of Manuel II in the West

and the objections of the Ottoman frontier lords of Rumili, who were

reluctant to give up hard-won territory to the infidel.

Eventually a treaty was signed in January-February 1403, by which

Emir Süleyman made extensive territorial concessions to Byzantium

(including the important cities of Thessaloniki and Mesembria) but was

allowed to keep Gallipoli.9 Genoa was exempted from certain tributes paid

in the past, Venice gained some territory in central Greece, and both

7

Until recently, the only aspect of the period to receive systematic treatment was the

Treaty of 1403, by which the Ottoman prince Emir Süleyman made various concessions to

Byzantium and other Christian powers. See Zachariadou, “Süleyman Çelebi in Rumili”;

and George T. Dennis, “The Byzantine-Turkish Treaty of 1403,” Orientalia Christiana Peri-

odica, 33 (1967): 72-88. For a detailed treatment of the Ottoman succession wars, see

Dimitris J. Kastritsis, “The Ottoman Interregnum (1402-1413): Politics and Narratives of

Dynastic Succession,” (Ph.D. diss., Harvard University, 2005). A revised version of this

work is forthcoming from Brill with the title The Sons of Bayezid: Empire Building and

Representation in the Ottoman Civil War of 1402-13.

8

The Venetian Senate reprimanded the captain of a ship belonging to the colony of

Crete, but in a letter to the Senate the captain defended himself by citing the fact that the

Genoese had broken the agreement first and that he was only doing the same as everyone

else. For this document, see Marie Mathilde Alexandrescu-Dersca, La campagne de Timur

en Anatolie (1402) (Bucharest: Monitorul Oficial si Imprimeriile Statului, 1942), 125-8.

9

For the text of the Treaty of 1403 and an analysis of its clauses, see Dennis, “The

Byzantine-Turkish Treaty of 1403.” See also Zachariadou, “Süleyman Çelebi in Rumili”;

and Kastritsis, “The Ottoman Interregnum,” 67-78.

ME 13,2_f5_222-242.indd 226 5/30/07 4:34:07 PM

D. J. Kastritsis / Medieval Encounters 13 (2007) 222-242 227

republics gained the release of prisoners captured by the Ottomans. Most

importantly, the merchant republics received guarantees that they would

be free to conduct their maritime trade unimpeded by Ottoman attacks.

This was helped by the fact that Süleyman had essentially given up control

of the straits to Byzantium and the Christian league and was only allowed

to keep a limited number of ships, which he promised not to use without

explicit permission. It is clear from the text of the treaty, which survives in

a Venetian translation, that Timur’s prolonged presence in Anatolia was

still causing concern to all parties, for Süleyman and the Christian powers

swore united action against him should he attempt to cross the straits.

Timur seems to have had no such intention, but it is interesting to note the

unity of Christendom and the Muslim Ottomans in the face of an outside

enemy.

The Treaty of 1403 was signed during Manuel II’s absence in the west

by his regent John VII and was then confirmed by Manuel upon his return

to Constantinople. Meanwhile the Venetians and Genoese had also signed

a treaty with Süleyman’s brother Isa, who was ruling at the time in the

Ottoman capital of Bursa, and Venice decided to confirm both treaties

by sending a proper embassy under Jacobo Suriano.10 Throughout the

Ottoman civil war, the Venetian Republic pursued its own interests by

signing treaties with whichever Ottoman prince happened to be in power

at a given time. Similarly, Genoa, which was under French rule, appointed

Marshal Boucicaut’s lieutenant Jean de Châteaumorand, who was taking

Manuel back to Constantinople, as envoy to the entire region including

Anatolia, with authority to negotiate with all parties.11

However willing the Italian merchant republics might have been to

negotiate with the Ottomans and other Turkish rulers in Anatolia, the

instability there following Timur’s departure made such negotiations

extremely difficult. By 18 May 1403, Isa had been replaced in Bursa by his

brother Mehmed, and by September of the same year he had apparently

died. The battles between the two Ottoman princes drew in the other

Turkish principalities of Anatolia (the beyliks), a pattern that would con-

tinue for the duration of the Ottoman civil war.12 Shortly after Isa’s death,

10

Suriano had reached the Levant by early May 1403 and was back in Venice by

September of the same year. See Zachariadou, “Süleyman Çelebi in Rumili,” 283-4.

11

Dennis, “The Byzantine-Turkish Treaty of 1403,” 73-4.

12

For Isa’s battles with Mehmed, see Kastritsis, “The Ottoman Interregnum,” 102-44.

Zachariadou’s theory about Isa is not to be accepted, as it is based on a mistaken interpreta-

tion of confusing sources.

ME 13,2_f5_222-242.indd 227 5/30/07 4:34:07 PM

228 D. J. Kastritsis / Medieval Encounters 13 (2007) 222-242

Süleyman crossed the straits with a large army and took from Mehmed

all of Ottoman Anatolia except for the Tokat-Amasya area, which was

Mehmed’s base.13 The long stalemate that ensued ended in 1409 with the

appearance of a fourth brother named Musa in the Black Sea–Danubian

region of the Balkans. This event was the product of concerted action on

the part of Mehmed, the beyliks of Karaman and Isfendiyar, the Voyvoda

of Wallachia Mircea the Elder, and probably also the Byzantine Emperor.

The eventual result was Süleyman’s death and the transfer of power in the

Ottoman Balkans (Rumili) to Musa. This juncture in the civil war deserves

to be examined in greater detail, for it reveals the policies of the various

Christian powers toward the Ottomans at that time. But to do so, it is first

necessary to go back a few years.

In 1404 King Sigismund of Hungary wrote the following words to the

Duke of Burgundy:

Be informed that certain agreements have been concluded between me and my brother

Wenceslas, King of the Romans and of Bohemia; that I have made peace and an alli-

ance with Ostoja, the King of Bosnia, and turned Stefan [Lazarević], the Duke of

Rascia, into my vassal; and that I have applied great force against the Turks and reported

some victories, sending strong auxiliary forces to join the Emperor of Constantinople

and the Voyvoda of Wallachia in carrying out some noble deeds against them.14

This passage provides some badly needed information on the actual situa-

tion in the Balkans following the Treaty of 1403. Three of the rulers men-

tioned by Sigismund were major Christian players in the Ottoman civil

war: Stefan Lazarević, Mircea the Elder (the Voyvoda of Wallachia), and of

course the Byzantine Emperor Manuel II Palaiologos. Manuel Palaiologos

13

On Süleyman’s crossing to Anatolia and his battles with Mehmed, see Kastritsis, “The

Ottoman Interregnum,” 145-54.

14

Eudoxiu de Hurmuzaki, Documente privitóre la Istoria Românilor (Bucharest, 1890),

429, doc. cccliii (my translation). See also Maria Matilda Alexandrescu-Dersca Bulgaru,

“Les relations du prince de Valachie Mircea l’ancien avec les émirs seldjoukides d’Anatolie

et leur candidat Musa au trône Ottoman,” Tarih Arastirmalari Dergisi, 6, nos. 10-11 (1968):

113-25, esp. 115. Since this is a rare publication, I am also providing the original text:

“Noueritis, inter me ac fratrem meum Venceslaum, Romanorum et Bohemiae Regem, cer-

tas quasdam pactiones esse factas; me cum Ostoja, Rege Bosnae, pacem ac foedus inisse,

Stephanum, Ducem Rasciae, mihi se subiecisse; et contra Turcos magna potentia profec-

tum, victorias aliquas reportasse, Constantinopolitanum Imperatorem ac Vaiuodam Vala-

chiae contra eosdem Turcos pulchra facinora gerere, meque illis magna misisse auxilia.”

ME 13,2_f5_222-242.indd 228 5/30/07 4:34:08 PM

D. J. Kastritsis / Medieval Encounters 13 (2007) 222-242 229

has already been discussed and we will return to his actions in a moment,

but let us first discuss the other two.

Stefan Lazarević was the son of King Lazar of Serbia, who was killed in

the Battle of Kosovo (1389); following that battle, Sultan Bayezid married

Stefan’s sister, and Stefan became one of the Ottoman Sultan’s more

important Balkan Christian vassals. After the Battle of Ankara, in which he

fought valiantly, Stefan Lazarević escaped to Constantinople, where the

Byzantine regent John VII granted him the prestigious title of despot, thus

making him at least nominally a Byzantine vassal. Shortly thereafter, Stefan

also became a vassal of Sigismund (as suggested in the letter quoted above),

who granted him the region of Mačva on the Danube, including the impor-

tant city of Belgrade.15 But Stefan also remained an Ottoman vassal, and

his position as such is recognized in the Treaty of 1403. Thus, we see that

Stefan was considered a vassal by three major powers (Byzantium, Hun-

gary, and the Ottoman Empire) representing the main religious divisions

of the fifteenth-century Balkans (Orthodoxy, Catholicism, and Islam). To

further complicate matters, Stefan Lazarević and his brother Vuk were also

involved in a feud with the rival Serbian clan of the Brankovici: in Novem-

ber 1402, in the immediate aftermath of the Battle of Ankara, Stefan and

his brother defeated the forces of George Branković, which included troops

provided by Süleyman.16 Such events (more of which will be examined

below) demonstrate the interconnectedness of the politics of the period,

which demanded a political calculus of Machiavellian proportions.

Let us turn now to another ruler mentioned in Sigismund’s letter, the

Wallachian Voyvoda Mircea the Elder (Mircea cel Bătrân). This man was an

old enemy of the Ottomans, having invaded their territory in the Balkans

leading up to the Battle of Rovine or Argeș (17 May 1395). There is evi-

dence of alliances dating back to that time between Mircea and several

Anatolian beyliks, especially that of Isfendiyar, and as we will see these come

into play again during Musa’s rise to power.17 Another important factor is

15

Fine, The Late Medieval Balkans, 500-3.

16

Konstanin the Philosopher, Lebensbeschreibung des Despoten Stefan Lazarevic, trans.

Maximilian Braun, Slavo-Orientalia, no. 1 (The Hague: Mouton, 1956): 23-6. See also

Fine, The Late Medieval Balkans, 500-2; Zachariadou, “Süleyman Çelebi in Rumili,” 289-

90; and Kastritsis, “The Ottoman Interregnum,” 75-8. While in Constantinople, Stefan

Lazarević apparently tried to persuade John VII to imprison George Branković upon his

return from Ankara.

17

See Alexandrescu, “Les relations du prince de Valachie Mircea,” 116.

ME 13,2_f5_222-242.indd 229 5/30/07 4:34:08 PM

230 D. J. Kastritsis / Medieval Encounters 13 (2007) 222-242

that while Mircea was primarily a Hungarian vassal, as an Orthodox Chris-

tian he also had a close connection to Byzantium. It is important to remem-

ber that at this time the Orthodox Christians of the Balkans were generally

divided between pro-Ottoman and pro-Catholic factions; Mircea and

Manuel Palaiologos both stood on the pro-Catholic side of this divide.

While the Ottomans were preoccupied with the Battle of Ankara, Mircea

had taken advantage of their weakness and invaded their territory in an

attempt to restore his rule over his old Transdanubian possessions in the

Dobrudja, apparently leading to a separate treaty between Mircea and Sül-

eyman.18 But this treaty did not prevent further hostilities; by 1406, if not

sooner, Mircea had occupied the Dobrudja and its main city of Silistria.19 It

is probably to this sort of activity that Sigismund is referring in his letter.

Seen in this light, it should come as no surprise to learn that Musa’s rise

to power in Rumili resulted from concerted action on the part of several

Christian and Muslim powers. Although such an interpretation has been

overshadowed by Musa’s anti-Christian policies following his rise to power,

in fact all evidence points in that direction. The role of Mircea is recog-

nized by Ottoman and Byzantine sources as well as modern scholarship;

that of Manuel Palaiologos, on the other hand, has been ignored, despite

the existence of several contemporary sources pointing in that direction.

The most important of these is the historical oration of Symeon, the arch-

bishop of Thessaloniki, who describes Musa’s accession as follows:

Not long after that, another evil spawn of that deadly viper, that Payiazit [Bayezid],

rose up against us. He was the infidel Moses [Musa], whom the pious basileus Manuel

invited and honored with much attention, providing him with copious provisions and

competent aides and ferrying him across to Wallachia. He took refuge there with the

assistance of the local Christian ethnarch, who conforming with the royal orders, cared

for that snake during the winter, who after creeping out of poverty and receiving

sufficient warmth from Christians, gaining from them even the power to rule, attacked

us Christians violently and murderously.20

18

See Zachariadou, “Süleyman Çelebi in Rumili,” 272-4.

19

Alexandrescu, “Les relations du prince de Valachie Mircea,” 115-18; and P. Ş. Na sturel,

“Une victoire du Voévoda Mircea l’Ancien sur les Turcs devant Silistria (c. 1407-08),” Stu-

dia et Acta Orientalia, 1 (1957): 239-47. For a detailed discussion of the evidence, see

Kastritsis, “The Ottoman Interregnum,” 182-3.

20

Politico-historical works of Symeon, Archbishop of Thessalonica (1416/17 to 1429): Critical

Greek Text with Introduction and Commentary, ed. David Balfour (Vienna: Verl. d. Österr.

Akad. d. Wiss., 1979), 48.

ME 13,2_f5_222-242.indd 230 5/30/07 4:34:08 PM

D. J. Kastritsis / Medieval Encounters 13 (2007) 222-242 231

Despite the fact that Symeon (writing in 1427 or 1428) was probably pres-

ent in Constantinople at the time he is describing, his editor David Balfour

dismisses his allegation that Manuel was behind the rise of Musa, attribut-

ing it to the author’s Byzantine “imperialist prejudice.”21 But a Byzantine

short chronicle confirms Symeon’s allegation, stating that in January of

1410 “Musa came from the land of the Tatars [i.e., the northern Black Sea

coast] and subjected himself (!"#$%&'() to the basileus Kyr Manuel.”22

The short chronicle’s editor Peter Schreiner also dismisses Manuel’s role

on the grounds that by that time Musa was already attacking, Byzantium

and the Byzantines were supporting his brother Süleyman. But it is clear

that during the Ottoman civil wars the Byzantine policy was to support

rival parties in an effort to crush the Ottomans once and for all. Let us take

a closer look at how this policy was applied.

As we have seen, after the Battle of Ankara, Byzantium and other Chris-

tian powers were eager to make peace with Süleyman and the other Otto-

man princes in an effort to make immediate gains and avoid a possible

crossing of Timur’s armies to Europe. But following Isa’s elimination and

Süleyman’s crossing to Anatolia, it seemed likely that Süleyman would

eliminate his brother Mehmed and reunite all remaining Ottoman terri-

tory under his rule. Such an event had to be avoided at all costs. Seen in

this light, Manuel’s desire to cooperate with Mircea in supporting a rival

claimant to the Ottoman throne seems natural.

This claimant was Musa Çelebi, a young Ottoman prince who had

ended up in Mehmed’s court after the disaster of 1402 and whom Mehmed

decided to release and send to the Balkans to create a diversion, forcing

Süleyman to turn his attention away from Anatolia. Such a diversion was

also in the interest of Byzantium, which hoped to see an all-out Ottoman

civil war break out around the straits in which at least one of the Ottoman

princes would be crushed. To profit as much as possible from this scenario,

Manuel contacted the Venetian Senate and proposed an anti-Turkish

alliance. The Senate’s answer, dated 10 January 1410, is preserved in the

Venetian archives.23 According to this document, Manuel informed Venice

21

Politico-historical works of Symeon, 123-4.

22

Die byzantinischen Kleinchroniken, ed. Peter Schreiner, 3 vols. (Vienna: Verl. d. Österr.

Akad. d. Wiss., 1975), 1:97; 2:397.

23

Acta Albaniae Veneta saeculorum XIV. et XV., ed. Giuseppe Valentini (Palermo: Typis

Josephi Tosini, 1967-), 4:1-3. This document is summarized by Nicolae Iorga (editor) in

Notes et extraits pour servir à l’histoire des Croisades au XV e siècle, in Revue de l’Orient Latin,

4 (1896): 311-12. See also Kastritsis, “The Ottoman Interregnum,” 190-1.

ME 13,2_f5_222-242.indd 231 5/30/07 4:34:09 PM

232 D. J. Kastritsis / Medieval Encounters 13 (2007) 222-242

that the time was ripe for a decisive strike against the Ottomans because of

the ongoing conflict between “those two brothers, who are rulers of the

Turks.” Manuel further urged the Venetians to send him eight galleys,

which together with two of his own could block the straits “in order to

obstruct transit from Turkey to Greece and vice versa, [and thereby] doom

them.” If the Venetians decided to help him, Manuel was sure that other

Christian rulers in the area would follow; but if he did not receive assis-

tance, he would have no other choice but to make peace with the Otto-

mans. The Venetian Senate politely refused Manuel’s offer, stating that the

Byzantine ruler should first secure the agreement of the other local powers

and that if they agreed, the Republic would also do its part.

After Venice’s refusal to cooperate in an anti-Muslim league, Manuel

was forced to do what he could on his own. Meanwhile, Musa Çelebi,

regardless of any support that he had received in the past from Manuel

Palaiologos, quickly turned against Byzantium and besieged Mesembria.24

Mesembria, on the Black Sea, was one of the towns returned to Byzantium

by Süleyman in the Treaty of 1403, so Musa’s action was probably moti-

vated by a desire to please his popular base, which included many Muslim

raiders (akıncı, gazi) disaffected with Süleyman’s peaceful policies toward

the Christians.25 Apparently, Musa had also made deals with Stefan

Lazarević and other Serbian leaders; we learn this from Stefan’s biographer

Konstantin the Philosopher, who states that “Musa showed himself upon

first appearance to the entire population in the neighboring regions as

mild and liberal, as if he wanted, as a model of piety, to pacify [the coun-

try]. Later, however, he showed himself to all those [people] to be more

bitter than gall, even for those who had served him.”26

While Musa was busy taking over Süleyman’s territory in the Ottoman

Balkans (Rumili) and returning to the aggressive policies of Bayezid I,

24

The siege took place between September 1409 and January 1410, as attested by a

short chronicle in Die byzantinischen Kleinchroniken, 1:215.

25

For Musa’s support among the raiders, see !Āșik"pașazāde, Die altosmanische Chronik

des !Āșik"pașazāde, ed. F. Giese (Leipzig: O. Harrassowitz, 1929), 73; and Konstantin the

Philosopher, Lebensbeschreibung des Despoten Stefan Lazarević, 31. The tovıca mentioned by

!Āșik"pașazāde were timar-holding (military fief-holding) officers of the akıncı. See Halil

İnalcık, “Notes on N. Beldiceanu’s translation of the K.anūnnāme, fonds turc ancien 39,

Bibliothèque Nationale, Paris,” Der Islam, 43 (1967): 139-57. For a more detailed discus-

sion, see Kastritsis, “The Ottoman Interregnum,” 185-6.

26

Konstantin the Philosopher, Lebensbeschreibung des Despoten Stefan Lazarević, 31 (my

translation from Braun’s German).

ME 13,2_f5_222-242.indd 232 5/30/07 4:34:09 PM

D. J. Kastritsis / Medieval Encounters 13 (2007) 222-242 233

Süleyman was informed of his brother’s actions and hastened to Rumili to

confront him while there was still time. At first Manuel appears to have

adhered to his original plan. According to a Ragusan report dated 30 May

1410:

[N]ow a certain ship captain sailing near those coasts, who returned from Avlona on

the 28th of the present month, reported to us that an ambassador of Lord Mirchxe

[Mircea] disembarked at Avlona from Constantinople on the 15th, saying that the

emperor of Constantinople captured Gallipoli with its fortifications, with the excep-

tion of the citadel, and surrounded [the city] by land as well as by sea with eight ships,

and that a truce has been declared, and [the city] is thought to have been secured. And

that Celopia [Süleyman] has appeared with many men on the coast and has been

diverted, asking the emperor and the Genoese to ferry him across, which was honor-

ably denied to him, and has had to go back on account of the trouble of his brother

Crespia [Kyritzes, i.e., Mehmed]. Avarnas [Evrenos] and six barons of Celopia who

had come to the Gallipoli area plotting [lit., “murmuring”] were captured by Musace-

lopia [Musa Çelebi].27

The contents of this report suggest that in May of 1410, Manuel Palaio-

logos and Mircea (a Hungarian vassal) were still trying to find a way to

exploit the Ottoman predicament, at a time when the Ottomans were split

between no fewer than three rival princes. It seems that the Byzantine

Emperor had succeeded in partially capturing the main Ottoman naval

base of Gallipoli (which remained Ottoman in the end) perhaps with the

help of the Genoese, who are mentioned in the document.28

Apart from the Ragusan report cited above, these events are not attested

in any other source. By 15 June 1410 (the date of the Battle of Kosmid-

ion), Manuel was once again supporting Süleyman, whose army crossed

27

Diplomatarium relationum Reipublicae Ragusanae cum regno Hungariae, ed. Jozsef

Gelcich and Lajos Thalloczy (Budapest: Magyar Tudományos Akadémia, 1887), 195. As

the text is somewhat convoluted, I also give the original: “[H]odie vero ad hec littora navi-

gans quidam brigantinus, qui die XXVIII. presentis de Avalona recesserat, nobis retulit

ambassiatorem domini Mirchxe a partibus Constantinopolis in diebus XV. descendisse ad

Valonam, narrantem Constantinopolitanum imperatorem Gallipoli cum fortiliciis, dempta

magistra turri, cepisse, eandemque circuisse per terram et galeis octo per mare, datisque

induciis creditur nunc adepta; Celopiam vero cum magno gencium apparatu ad littora

declinasse, petentem ab imperatore et Januensibus paregium, cui honesto modo denega-

tum fuit, et propter Crespie fratris molestias retrocessit. Avarnas et sex baronos Celopie, qui

ad partes Galipolis susurantes venerant, a Musicelopia detinentur captivos.”

28

To the best of my knowledge, this brief and partial conquest of Gallipoli by the Byz-

antines has never before been reported in modern scholarly literature.

ME 13,2_f5_222-242.indd 233 5/30/07 4:34:09 PM

234 D. J. Kastritsis / Medieval Encounters 13 (2007) 222-242

the straits to Constantinople on board Byzantine ships.29 The Byzantine

Emperor’s decision to support Süleyman was probably motivated by the

immediate danger posed by Musa, who two weeks earlier had captured

Hagios Phokas (a suburb of Constantinople, modern Ortaköy) from a

force loyal to Süleyman.30 There are also references in Ottoman and Byz-

antine chronicles to renewed concessions from Süleyman to Byzantium

and even to a marriage alliance with the family of Manuel Palaiologos.31

Whatever his reasons, Manuel agreed to support Süleyman against

Musa, and the ensuing Battle of Kosmidion was fought right outside the

land walls of Constantinople within sight of the Byzantine palace of Blach-

ernae. According to Konstantin the Philosopher, Süleyman and his army

“flowed out of the walls of Constantinople,” and Manuel had readied ships

to rescue them if necessary, which were burned by Musa before the battle.

Stefan Lazarević and his brother Vuk took part on opposite sides (Vuk had

deserted to Süleyman on the eve of the battle); after Musa lost and was

routed, Stefan entered Constantinople on board Byzantine ships, so that

29

See “Una inedita cronaca bizantina (dal Marc. Gr. 595),” ed. Elpidio Mioni, Rivista

di Studi Bizantini e Slavi, 1 (1980): 71-87, esp. 75, 82. Peter Schreiner was unable to

include this important short chronicle in his collection, as he was unaware of its existence.

30

“Una inedita cronaca bizantina,” 75, 82. The chronicle states that Musa fought this

battle “with Paschainoi” ( )*+, -./0.12&2), an otherwise unknown term possibly related

to the Turkish baskın (raid), which would then refer to Musa’s popular base among the

raiders of Rumili. I am indebted to Professor Elizabeth Zachariadou for this observation.

31

A contemporary Ottoman chronicle of the Interregnum states that Süleyman renewed

his alliance with Manuel Palaiologos “by promising him some regions.” This chronicle was

composed in the court of Mehmed Çelebi and survives in two later compilations, those of

Neșri and Oxford Anonymous. See Franz Taeshner, Gihānnümā: Die altosmanische Chronik

des Mevlana Mehemmed Neschri, vol. 1: Einleitung und Text des. Cod. Menzel (Leipzig: O.

Harrassowitz, 1951); and F. R. Unat and M. A. Köymen, Kitâb-ı Cihan-nümâ: Neșrî tarihi,

critical ed. in 2 vols. (Ankara: Türk Tarih Kurumu Basimevi, 1949-57). For the Oxford

Anonymous chronicle, see Halil Erdoğan Cengiz and Yașar Yücel, “Rûhî Târîhi,” Belgeler,

14-18 (1989-92): 359-472, as well as unnumbered facsimile folia. A new edition and trans-

lation of the chronicle is available in Kastritsis, “The Ottoman Interregnum,” 313-448

(publication forthcoming in Sources of Oriental Languages and Literatures). For the marriage

alliance between Manuel and Süleyman, see J. W. Barker, Manuel II Palaeologus (1391-

1425): A Study in Late Byzantine Statemanship (New Brunswick, N.J., 1968), 253 n. 88.

The anonymous chronicle in Codex Barberinus Grecus 111 and Pseudo-Phranzes identify

this princess as the daughter of Manuel’s deceased brother Theodore, while Chalkokon-

dyles states that she was the daughter of Hilario Doria, Manuel’s son-in-law through his

illegitimate daughter Zampia. A daughter of the same Doria was supposedly married to

Küçük Mustafa in 1422; this fact could account for the confusion in Chalkokondyles.

ME 13,2_f5_222-242.indd 234 5/30/07 4:34:10 PM

D. J. Kastritsis / Medieval Encounters 13 (2007) 222-242 235

“victors and defeated came into the imperial city together.”32 The Battle of

Kosmidion is thus a prime example of the involvement of Christian pow-

ers in the Ottoman civil war.

This involvement continued in the months following Kosmidion and

was essential to Musa’s eventual seizure of power in Rumili. After his vic-

tory, Süleyman returned to the throne in Edirne, while Mehmed rushed in

to fill the power vacuum created in Anatolia by Süleyman’s departure.

Musa fled to his main power base in the northeastern Balkans, where he

continued to enjoy the support of his Muslim raiders and Christian allies.

According to Konstantin the Philosopher, after his victory Süleyman pun-

ished Stefan Lazarević for supporting Musa by sending his brother Vuk to

seize his lands, but Vuk was captured by one of Musa’s pashas along with

his nephew Lazar Branković. The two Serbs were brought to Musa, who

had Vuk executed but kept Lazar for use in bargaining with his powerful

older brother George Branković. Stefan Lazarević was indebted to Musa

and continued to support him in his struggle against Süleyman, but Lazar

failed to deliver and was executed after Musa failed again to seize power

from his brother at the Battle of Edirne (11 July 1410).33 Thus, we see

that the Ottoman civil strife in the Balkans at this time is directly con-

nected to the power struggles between rival Serbian lords, especially Stefan

Lazarević (who supported Musa) and George Branković (who remained

loyal to Süleyman).

Thanks to the support of Stefan Lazarević and his own loyal raiders,

Musa survived into the winter of 1410-11, when he was finally able to kill

Süleyman and seize from him the throne in Edirne. According to a Byzan-

tine short chronicle, Süleyman “had taken to bathing and was drinking

one glass after another, the lords and grandees got fed up, and the armies

left and started to desert to Musa Beg. When Emir Süleyman heard this,

he was afraid and tried to escape, but was caught in the area of Bryse and

strangled on 17 February [1411], which was a Tuesday.”34 There is no need

to dwell here on this event, which is recounted in different ways in several

sources. Suffice it to say that Süleyman fell from power because he had

32

Konstantin the Philosopher, Lebensbeschreibung des Despoten Stefan Lazarević, 33-5.

33

Konstantin the Philosopher, Lebensbeschreibung des Despoten Stefan Lazarević, 35-8.

For a more detailed treatment of the events surrounding the Battle of Edirne, see Kastritsis,

“The Ottoman Interregnum,” 200-1.

34

Die byzantinischen Kleinchroniken, 1:637 (96/7). Brysē corresponds to the modern

village of Pınarhisar between Kırklareli and Vize.

ME 13,2_f5_222-242.indd 235 5/30/07 4:34:10 PM

236 D. J. Kastritsis / Medieval Encounters 13 (2007) 222-242

followed peaceful policies toward his Christian neighbors, which had alien-

ated those of his subjects whose livelihood depended on war (such as the

akıncı and their leaders, who had joined Musa). When he was apprehended

and strangled, Süleyman was on his way to Constantinople.35

With Musa’s accession to the Ottoman throne in Rumili, Christian-

Muslim relations in the Balkans entered a new phase. Musa refused to accept

Süleyman’s concessions to Byzantium and the other Christian powers there

and unleashed his raiders onto their territory. In so doing, he was returning

to the aggressive imperialist policies of his father, Bayezid I, which aimed to

create a seamless and expanding Ottoman domain. Musa’s first attacks

appear to have been against Stefan Lazarević’s Serbia. The Byzantine chron-

icler Laonikos Chalkokondyles blames these attacks on Stefan’s abandon-

ment of Musa during the Battle of Kosmidion, while Stefan’s biographer

Konstantin the Philosopher (who is of course biased in his favor) blames

them solely on Musa’s duplicity.36 The fact is that in addition to being a loyal

Ottoman vassal, Stefan Lazarević was also a vassal of the Hungarian king

and controlled territory that stood in the way of Ottoman expansion in the

Balkans. For this reason alone, he had to be eliminated and his territory

assimilated into the centralized Ottoman land-tenure system (timar).37

After the souring of relations between the two men, Stefan Lazarević

made the first strike by occupying the town of Pirot (Şehirköy). Musa

responded by ravaging the surrounding area, capturing three towns and

massacring their inhabitants and besieging Smederovo in Stefan’s north-

ernmost province of Mačva.38 According to an Ottoman source, Musa also

attacked Vidin (which had revolted), Provadia (Pravadi) on the Black Sea,

and the Serbian town of Koprian (Köprülü), commanding “raids in every

35

For a detailed discussion of this event and the political significance of its representa-

tion in the sources, see Kastritsis, “The Ottoman Interregnum,” 202-8.

36

Chalkokondyles, Laonici Chalcocandylae historiarum demonstrationes, ed. Jenö Darkó,

(Budapest: Acad. Litterarum Hungaricae, 1922-27), 165; Konstantin the Philosopher,

Lebensbeschreibung des Despoten Stefan Lazarević, 42-3.

37

See Halil İnalcık, “Ottoman Methods of Conquest,” Studia Islamica, 2 (1954): 103-29.

38

Konstantin the Philosopher, Lebensbeschreibung des Despoten Stefan Lazarević, 43;

Politico-historical works of Symeon, 48, 124-5; Doukas, Istoria Turco-Bizantina (1341-1462),

ed. Vasile Grecu (Bucharest: Editura Academiei Republicii Populaire Romîne, 1958),

English trans. in Harry J. Magoulias, Decline and Fall of Byzantium to the Ottoman

Turks (Detroit: Wayne State University Press, 1975), chap. 19, sec. 8. I am referring to

chapters and sections rather than page numbers, so that the reader may use any edition or

translation.

ME 13,2_f5_222-242.indd 236 5/30/07 4:34:11 PM

D. J. Kastritsis / Medieval Encounters 13 (2007) 222-242 237

direction so that his lands were filled [with spoils] and became rich.”39

Raids were also carried out in Albania and southern Greece.40 But in

peripheral regions, following common Ottoman practice, Musa was not

averse to forming alliances with local lords in an effort to gain new vassals

and extend Ottoman influence. By 1413 he had formed such an alliance

with Carlo Tocco of Cephalonia against Tocco’s Albanian enemies, the

Zenevesi, which was sealed by Musa’s marriage to Tocco’s daughter, who

was supposedly illegitimate.41

But no such alliance was possible with Byzantium, which stood in the

way of Ottoman expansion, had supported Süleyman, and continued to

harbor an Ottoman pretender in the person of Süleyman’s son Orhan. In

the summer of 1411, Musa besieged Thessaloniki, Constantinople, and

Selymbria. Thessaloniki was an obvious choice, since it was the most

important city Süleyman had returned to the Byzantines in the Treaty of

1403. Constantinople was besieged both by land and by sea, and many

Byzantines and Turks were killed in sallies outside the city walls.42 To relieve

the imperial city, Manuel II sent the pretender Orhan to Selymbria, thereby

forcing Musa to move his main siege operations to that town.43 When he

went to the siege of Selymbria, Musa took with him George Branković,

apparently trying to poison him along the way; but the Serb survived the

poisoning thanks to an antidote and took refuge within the walls of the

39

This source is preserved in two chronicles: Die altosmanischen anonymen Chroniken:

Tevârîh-i Âl-i !Osmān, ed. Friedrich Giese, 2 vols. (Breslau: Im Selbstverlage Breslau XVI,

1922), 1:51; Die altosmanische Chronik des !Āșik"pașazāde, 74.

40

Freddy Thiriet, Régestes des délibérations du Sénat de Venise concernant la Romanie,

vol. 2:1364-1463 (Paris: Mouton, 1958-61): 98, 106. The citizens of Nauplion complained

that they were suffering greatly from Turkish raids that they were unable to predict, and the

Venetian Senate advised the recruitment of spies to observe Turkish movements in the area.

41

See Cronaca dei Tocco di Cefalonia di anonimo, ed. Giuseppe Schirò (Rome: Acca-

demia nazionale dei Lincei, 1975), 360-2. It is possible that the chronicle’s author is down-

playing the whole affair by claiming that Tocco’s daughter was illegitimate.

42

Chalkokondyles, Laonici Chalcocandylae historiarum demonstrationes, 166, states that

Musa attempted to blockade Constantinople by sea but was defeated by Manuel, “the bas-

tard son of the emperor John,” in a naval battle. Doukas, 19:9, informs us that the son of

Manuel II’s interpreter Nicholas Notaras was captured outside the city walls and executed

by Musa. On this incident, see also A. Acconcia Longo, “Versi di Ioasaf ieromonaco e

grande protosincello in morte di Giovanni Notaras,” Rivista di Studi Bizantini e Neoellenici,

14-16 (1977-79): 249-79.

43

Thanks to the Ottoman-Venetian treaty signed at this time (see below), we know that

Musa was outside the walls of Constantinople by 12 August 1411, but that by 3 September

ME 13,2_f5_222-242.indd 237 5/30/07 4:34:11 PM

238 D. J. Kastritsis / Medieval Encounters 13 (2007) 222-242

besieged city. Still fearing for his life, Branković began negotiations with

his uncle and rival Stefan Lazarević through the intercession of his mother,

who was Stefan’s sister.44 Thus, we see that, less than a year after his acces-

sion, Musa’s hostility was already causing his enemies to overcome their

differences and band together against him. It was precisely that trend that

led to Musa’s eventual overthrow by his brother Mehmed I. Musa alienated

many people, not all of them Christian; his enemies also included power-

ful Ottoman frontier lords (uc begleri) like Evrenos and Mihal-oğlı

Mehmed, who escaped from Selymbria to Mehmed in Anatolia via Con-

stantinople.45 The uc begleri were alienated by Musa’s centralizing policies,

which aimed at undermining their power and replacing them with his own

men, who were often slaves of the Porte (kul ).46

Let us turn now to the position of Venice. As we have seen above,

throughout the Ottoman Interregnum the main concern of the Serenis-

sima was to preserve and enlarge its network of maritime bases and to

guarantee the safety of its merchants. Promises to cooperate with other

Christian powers against the infidel Ottomans were only carried out when

otherwise convenient and took second place to Venice’s main goals, which

were essential to its survival. After the Treaty of 1403, which had been

renewed in 1409, Venice had been at peace with the Ottomans of Rumili

in exchange for the payment of various annual tributes. But following

Süleyman’s death and Musa’s accession to the throne in Edirne, the situa-

tion had changed and the old treaties were no longer valid, resulting in the

capture of some Venetian ships along with their crews and merchandise.

The Venetian Senate was anxious to resolve the situation as soon as pos-

sible. After rejecting a motion to seize Gallipoli from the Ottomans, the

Senate (which had already instructed its bailo in Constantinople to assure

he had moved to Selymbria. For the release of Orhan, see Politico-historical works of Symeon,

49, 125. It has been suggested (Colin Imber, Encyclopedia of Islam, new ed., s.v. “Mūsā

Čelebi”) that Orhan was released immediately upon Musa’s accession, but this is unlikely

as there is no such mention in the sources and Musa would have had to deal with the

challenge immediately.

44

Konstantin the Philosopher, Lebensbeschreibung des Despoten Stefan Lazarević, 43-4;

see also Stanoje Stanojević, “Die Biographie Stefan Lazarević’s von Konstantin dem Phi-

losophen als Geschichtsquelle,” Archiv für Slavische Philologie, 18 (1896): 409-72, esp. 445.

45

On Mihal-oğlı Mehmed’s defection, see Konstantin the Philosopher, Lebensbesch-

reibung des Despoten Stefan Lazarević, 44-5.

46

See Die altosmanischen anonymen Chroniken, 1: 49-50.

ME 13,2_f5_222-242.indd 238 5/30/07 4:34:11 PM

D. J. Kastritsis / Medieval Encounters 13 (2007) 222-242 239

the new Ottoman ruler of the Republic’s goodwill toward his regime)

decided to send an ambassador to negotiate a new treaty.47 On 4 June

1411, the Senate provided its ambassador Giacomo Trevisan with instruc-

tions for his upcoming embassy to Musa.

These instructions are preserved in the Venetian archives and provide a

fascinating glimpse into Venetian policy and the complex situation in

Rumili at the time.48 Due to recent events (propter novitates factas), Trev-

isan was advised to use his own judgment in reaching the person of Musa

and attaining his mission’s objectives. Once he reached the Ottoman ruler,

he was to remind him of the good relations that had existed between Ven-

ice and his predecessors. He was to hint at the fact that various “princes and

communities” had proposed to Venice alliances against Musa based on the

perception that his position was weak, but that the Republic paid no heed

to such proposals, preferring instead to conclude a treaty. The treaty would

guarantee the safety of all Venetian possessions, including those given by

Süleyman in 1403. To attain the success of his mission, Trevisan was given

authority to bribe one of Musa’s “baroni” (i.e., uc begleri), preferably Mihal-

oğlı Mehmed, with an annual tribute of up to one hundred ducats. He was

also to ascertain the relative power in the new regime of the uc begleri Evre-

nos and Pașa Yiğit (with whom the Republic had dealt in the past) to

determine which of them would be most useful in protecting Albania from

the incursions of Balša and other enemies, and bribe them each accord-

ingly. If Trevisan was able to obtain a treaty, he was to ensure its application

by obtaining orders to the relevant Ottoman authorities; if not, he was to

attempt to conclude a truce of one year. If Musa refused to concede to

either a treaty or a truce, Trevisan was to depart for Constantinople, where

he was to inform Venice of the situation as soon as possible. He should

then obtain an audience with the Byzantine Emperor by showing a letter

of credentials provided for that purpose and begin negotiations with him

for joint action against Musa in the name of Christendom. Trevisan was

also provided with a letter of credentials for Musa’s brother Mehmed, in

case in the meantime he had succeeded in seizing power in Rumili.

Trevisan’s embassy was successful. On 12 August 1411, a treaty was drawn

up outside the besieged city of Constantinople (al fanari de Constanti-

nopol ), where Musa was at the time. But because of some disagreements,

47

Thiriet, Régestes des délibérations du Sénat de Venise, 2:98-9.

48

Acta Albaniae Veneta saeculorum XIV. et XV., 6:151-62. For a more detailed English

summary of the text, see Kastritsis, “The Ottoman Interregnum,” 226-35.

ME 13,2_f5_222-242.indd 239 5/30/07 4:34:12 PM

240 D. J. Kastritsis / Medieval Encounters 13 (2007) 222-242

the treaty was not signed until 3 September, by which time Musa had

moved to Selymbria and was besieging that town as well. Needless to say,

the Byzantines were angered that Venice would dare to negotiate and sign

a treaty with the infidel while he was besieging Christian cities. In May

1412, the Senate defended its actions to an ambassador of Manuel II by

stating that it was only natural to sign the treaty in Selymbria, since that

was where the Sultan was at the time, and that Byzantium could also have

benefited from such a treaty.49

But by that time, Byzantium was committed to its own policy of replac-

ing Musa with a rival Ottoman pretender. By the winter of 1411-12, Musa

was faced with a multitude of challenges on several different fronts. The

Byzantines sent Süleyman’s son Orhan from Selymbria to Thessaloniki;

Orhan started a campaign for the Ottoman throne in the surrounding

Ottoman regions, apparently gaining a fair amount of support before

being betrayed by one of his lords and strangled.50 Around the same time,

the Byzantines also sent George Branković to Thessaloniki on board a

ship belonging to the Venetian colony of Crete, an event that caused con-

sternation to the Republic because it threatened the recently signed treaty

with Musa.51 Leaving Thessaloniki, George Branković was eventually

able to join up with his former enemy Stefan Lazarević, who had with

him the Ottoman lords Pașa Yiğit and Yusuf and another Ottoman

pretender known as the “son of Savcı.”52 This prince was apparently

the son of Murad I’s son Savcı, who in 1373 had joined the Byzantine

prince Andronikos in a rebellion against their respective fathers.53 Finally,

Acta Albaniae Veneta saeculorum XIV. et XV., 6:139-40.

49

Orhan issued a document between 26 January and 4 February 1412. See Vančo

50

Boškov, “Ein Nišān des Prinzen Orh#an, Sohn Süleymān Çelebis, aus dem Jahre 1412 im

Athoskloster Sankt Paulus,” Wiener Zeitschrift für die Kunde des Morgenlandes, 71 (1979):

127-52. See also Chalkokondyles, Laonici Chalcocandylae historiarum demonstrationes, 166-7;

and Konstantin the Philosopher, Lebensbeschreibung des Despoten Stefan Lazarević, 50.

51

Konstantin the Philosopher, Lebensbeschreibung des Despoten Stefan Lazarević, 46;

Thiriet, Régestes des délibérations du Sénat de Venise, 104-5. Apparently the ship was

forced by the Byzantines to convey George Branković to Thessaloniki despite a Venetian

prohibition.

52

For these events, see Konstantin the Philosopher, Lebensbeschreibung des Despoten Ste-

fan Lazarević, 46-7; Kastritsis, “The Ottoman Interregnum,” 238-40.

53

See The Oxford Dictionary of Byzantium, s.v. “Savcı Beg.” Apparently Timur had granted

Bursa to the “son of Savcı” immediately after the Battle of Ankara, but he was quickly replaced

there by Isa. According to a contemporary observer, after Timur’s army destroyed the city on

3 August, Timur gave it to “a nephew of Bayezid who was the son of his blind brother.”

ME 13,2_f5_222-242.indd 240 5/30/07 4:34:12 PM

D. J. Kastritsis / Medieval Encounters 13 (2007) 222-242 241

Mehmed Çelebi’s first failed campaign against Musa which resulted in the

Battle of Inceğiz can probably also be placed in the fall of 1411 or spring

of 1412. Mehmed was supported by the Byzantines, who ferried him and

his army across the straits to Constantinople in exchange for oaths of peace

and mutual assistance.54 Mehmed lost the battle and took refuge in the

walls of Constaninople—the resemblance to the Byzantines’ treatment of

Süleyman at the Battle of Kosmidion is obvious.

By the summer of 1413, the alliances between Musa’s many Christian

and Muslim enemies finally bore fruit, and Musa was defeated and stran-

gled by his brother Mehmed on the battlefield of Çamurlu near Sofia

(5 July 1413). In the buildup to this decisive battle, which is described in

detail in a number of sources and immortalized in an Ottoman epic poem,

Mehmed relied on the assistance of the Anatolian tribal confederacy of

Dulkadır, the Byzantines in Constantinople and Thessaloniki, the discon-

tented Ottoman frontier lords of Rumili, and a host of Serbs and other

Hungarian vassals under the leadership of Stefan Lazarević, including the

Bosnian lord Sandalj.55

In conclusion, while the Ottoman succession wars of 1402-1413 might

have provided an excellent opportunity for Byzantium, Hungary, and

other Christian powers opposed to Ottoman expansion to unite against

the Ottomans and force them out of Europe, this did not happen. On the

contrary, Byzantium and Stefan Lazarević with his fellow Hungarian vas-

sals proved essential to the reunification of the Ottoman realm under

Mehmed I, who repaid the favor by pursuing relatively peaceful policies

toward his former allies until his death in 1421. During the course of the

succession wars, the Byzantine Emperor Manuel II had attempted to coop-

erate with King Sigismund of Hungary, Voyvoda Mircea of Wallachia, and

See the account of Gerardo Sagredo in Alexandrescu, La campagne de Timur en Anatolie,

130. According to the Ottoman chronicle of the Interregnum Ah" vāl-i Sult"ān Meh" emmed, a

man named Ali who was “the son of Savcı” (S"avcı-og$lı) attacked Mehmed Çelebi in the

winter of 1402-3 near Ankara. See Kastritsis, “The Ottoman Interregnum,” 100-1.

54

Doukas, 19:10; Konstantin the Philosopher, Lebensbeschreibung des Despoten Stefan

Lazarević, 45; and Kastritsis, “The Ottoman Interregnum,” 235-7.

55

For a detailed account of the buildup to the Battle of Çamurlu and its sources, see

Kastritsis, “The Ottoman Interregnum,” 247-57. For the Ottoman epic poem, see Abdülvāsi!

Çelebi, Hâlilname, ed. Ayhan Güldaș (Ankara: T. C. Kültür Bakanlığı, 1996), 254-78;

Ayhan Güldaș, “Fetret Devri’ndeki Şehzadeler Mücadelesini Anlatan Ilk$ Manzum Vesika,”

Türk Dünyası Araștırmaları, 72 (June 1991): 99-110; and Kastritsis, “The Ottoman Inter-

regnum,” 451-68 (English trans.).

ME 13,2_f5_222-242.indd 241 5/30/07 4:34:12 PM

242 D. J. Kastritsis / Medieval Encounters 13 (2007) 222-242

the Venetian Senate to destroy the Ottomans; in the end, however, his

efforts had only resulted in the replacement of the relatively friendly Süley-

man with the much more aggressive Musa. This ruler had to be removed at

all costs, hence the support of virtually everyone for his brother Mehmed,

who was proclaimed sole Ottoman Sultan in 1413.

A detailed examination of the period’s politics reveals the important role

of regional power brokers, which transcended their often dubious religious

affiliations: these included Serbian and other Balkan noblemen and the

Ottoman lords of the marches (uc begleri). In a time of political uncer-

tainty and fragmentation, the major powers of the Balkans (the Ottomans,

Hungary, and to a much lesser extent, Byzantium) attempted to assert

their power over regional power brokers by claiming rights of vassalage,

while Venice stayed informed about which of them were most powerful in

order to bribe them. But despite their great power, these men played a

dangerous game, for their loyalties were always shifting so that they might

find themselves owing allegiance to more than one master at the same

time. Finally, the Ottoman succession wars and the strategic position of

Constantinople on the straits allowed Byzantium to develop a policy of

harboring and unleashing Ottoman pretenders to the throne. It was that

policy that enabled Byzantium to survive until 1453. But the opportunity

provided in 1402 for the Ottomans’ Christian enemies to unite and crush

them once and for all had been lost, never to come again.

ME 13,2_f5_222-242.indd 242 5/30/07 4:34:13 PM

You might also like

- Ottoman EmpireDocument246 pagesOttoman EmpireAli Chamseddine100% (8)

- The Fall of Constantinople: The Brutal End of the Byzantine EmpireFrom EverandThe Fall of Constantinople: The Brutal End of the Byzantine EmpireRating: 5 out of 5 stars5/5 (2)

- Crusading Between The Adriatic and The Black Sea - Hungary, Venice and Ottoman Empire After The Fall of NegroponteDocument39 pagesCrusading Between The Adriatic and The Black Sea - Hungary, Venice and Ottoman Empire After The Fall of NegroponteZlatko VlašićNo ratings yet

- Homosexuality in The Ottoman EmpireDocument17 pagesHomosexuality in The Ottoman EmpireDain Demirayak100% (1)

- Falsification and Disinformation - Negative Factors in Turco-Armenian Relations - Salahi R. SonyelDocument34 pagesFalsification and Disinformation - Negative Factors in Turco-Armenian Relations - Salahi R. SonyelTheBrennpunktNo ratings yet

- Geopolitics TriumphDocument17 pagesGeopolitics TriumphAriel RadovanNo ratings yet

- The Fall of ConstantinopleDocument13 pagesThe Fall of Constantinoplediscovery07No ratings yet

- A Crowning in Constantinople On August 1 1203 & Its Significance PDFDocument31 pagesA Crowning in Constantinople On August 1 1203 & Its Significance PDFJosé Luis Fernández BlancoNo ratings yet

- Alexandru Simon Matthias Corvinus' Anti Ottoman Policies in The Early 1470'Document55 pagesAlexandru Simon Matthias Corvinus' Anti Ottoman Policies in The Early 1470'Justin Lazar100% (1)

- SHUKUROV, Trebizond and The SeljuksDocument66 pagesSHUKUROV, Trebizond and The SeljuksDejan MitreaNo ratings yet

- Christians and Jews in The Ottoman Empire - IntroductionDocument52 pagesChristians and Jews in The Ottoman Empire - IntroductionRosa OsbornNo ratings yet

- Sahin 2010 Constantinople and The End TimeDocument38 pagesSahin 2010 Constantinople and The End Timeashakow8849100% (1)

- Michael A. Reynolds - Buffers, Not Brethren: Young Turk Military Policy in The First World War and The Myth of PanturanismDocument43 pagesMichael A. Reynolds - Buffers, Not Brethren: Young Turk Military Policy in The First World War and The Myth of PanturanismSibiryaKurdu100% (1)

- Ottoman Methods of ConquestDocument28 pagesOttoman Methods of Conquestleki86No ratings yet

- The Bektashi Sufi Order: Dr. Hajredin HoxhaDocument38 pagesThe Bektashi Sufi Order: Dr. Hajredin HoxhaMarius100% (1)

- Second Balkan CrisisDocument10 pagesSecond Balkan Crisisapi-317411236No ratings yet

- CrusadesDocument281 pagesCrusadesVladescu AlexandruNo ratings yet

- Qdoc - Tips - The Byzantine Art of WarDocument271 pagesQdoc - Tips - The Byzantine Art of Warpiwipeba100% (1)

- KARPAT, K., Ottoman Views and Policies Towards The Orthodox ChurchDocument26 pagesKARPAT, K., Ottoman Views and Policies Towards The Orthodox Churchbuciumeni100% (1)

- Shadow of The Sultan's Realm - The Destruction of The Ottoman Empire and The Creation of The Modern Middle East (PDFDrive)Document261 pagesShadow of The Sultan's Realm - The Destruction of The Ottoman Empire and The Creation of The Modern Middle East (PDFDrive)coolbuddy2010100% (2)

- Balkan WarsDocument20 pagesBalkan WarsAliNo ratings yet

- Creating East and West: Renaissance Humanists and the Ottoman TurksFrom EverandCreating East and West: Renaissance Humanists and the Ottoman TurksRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (4)

- The Byzantine Legacy and Ottoman FormsDocument59 pagesThe Byzantine Legacy and Ottoman FormsDita Starova QerimiNo ratings yet

- Islam in Global History: Volume Two: From the Death of Prophet Muhammed to the First World WarFrom EverandIslam in Global History: Volume Two: From the Death of Prophet Muhammed to the First World WarNo ratings yet

- Peeters PDFDocument13 pagesPeeters PDFLessieNo ratings yet

- Kastritsis - Dimitris - Religious Affiliations and Political Alliances in The Ottoman Succession Wars of 1402-1413Document21 pagesKastritsis - Dimitris - Religious Affiliations and Political Alliances in The Ottoman Succession Wars of 1402-1413AsekaNo ratings yet

- Gábor Ágoston, Ottoman Expansion and Military Power 1300-1453Document21 pagesGábor Ágoston, Ottoman Expansion and Military Power 1300-1453jenismoNo ratings yet

- Broad Historical Context The Rise of The Ottoman Empire and The Formation of Muslim Communities in The Balkans As An Integral Part of The Ottomanization of The RegionDocument27 pagesBroad Historical Context The Rise of The Ottoman Empire and The Formation of Muslim Communities in The Balkans As An Integral Part of The Ottomanization of The Regionali0719ukNo ratings yet

- Spol 24 2-DoboszDocument16 pagesSpol 24 2-DoboszMohand IssmailNo ratings yet

- Islam Dan BaratDocument22 pagesIslam Dan BaratULFIA SAGUSTANo ratings yet

- Lewis Some Reflections On The Decline of The Ottoman EmpireDocument18 pagesLewis Some Reflections On The Decline of The Ottoman EmpireFatih YucelNo ratings yet

- Ottoman Empire Essay ThesisDocument4 pagesOttoman Empire Essay Thesisirywesief100% (2)

- PROBLEMS OF PERIODIZATION IN OTTOMAN HISTORY The Fifteenth Through The Eighteenth CenturiesDocument8 pagesPROBLEMS OF PERIODIZATION IN OTTOMAN HISTORY The Fifteenth Through The Eighteenth CenturiesFırat COŞKUNNo ratings yet

- Ottoman Empire Decline ThesisDocument8 pagesOttoman Empire Decline Thesisheatherharveyanchorage100% (2)

- The Peak of Ottoman PowerDocument7 pagesThe Peak of Ottoman PowerLaloNo ratings yet

- The East, The West, and The Appropriation of The PastDocument25 pagesThe East, The West, and The Appropriation of The PastourbookNo ratings yet

- Ottoman AcehDocument19 pagesOttoman AcehAsep Wahyu HidayatNo ratings yet

- Compare OttmnDocument19 pagesCompare OttmnTurcology TiranaNo ratings yet

- The Changing Landscape: Volume I of the series Reporting a WarFrom EverandThe Changing Landscape: Volume I of the series Reporting a WarNo ratings yet

- Ottoman Tolerance or Pragmatism?Document33 pagesOttoman Tolerance or Pragmatism?af asdwdNo ratings yet

- Osmanli: The Journal of Ottoman Studies XVDocument14 pagesOsmanli: The Journal of Ottoman Studies XVSelin ÇoruhNo ratings yet

- Rise of The Ottoman EmpireDocument14 pagesRise of The Ottoman EmpireThomas JenningsNo ratings yet

- The Ottoman's Empire Police System The Ottoman Empire Law Enforcement SystemDocument21 pagesThe Ottoman's Empire Police System The Ottoman Empire Law Enforcement SystemWal KerNo ratings yet

- A New Approach To The Moldavian Exterior PDFDocument20 pagesA New Approach To The Moldavian Exterior PDFMalina LibitNo ratings yet

- Ottoman Diplomacy PDFDocument13 pagesOttoman Diplomacy PDFSiraj KuvakkattayilNo ratings yet

- K1m 6xH2mVzBDocument3 pagesK1m 6xH2mVzBANo ratings yet

- ByzantineDocument5 pagesByzantinekyla maliwatNo ratings yet

- Gracious Sultan, Grateful SubjectsDocument27 pagesGracious Sultan, Grateful Subjects摩苏尔No ratings yet

- Warfare and Imperial PropagandaDocument32 pagesWarfare and Imperial PropagandaborjaNo ratings yet

- Lewis Ch2 Silver, Inflation and EconomyDocument19 pagesLewis Ch2 Silver, Inflation and EconomySeungjune MinNo ratings yet

- Between Ottoman Empire and Latin Christe PDFDocument25 pagesBetween Ottoman Empire and Latin Christe PDFOleksiy BalukhNo ratings yet

- Pust - Migrations From The Venetian To The Ott Territory (16th C.) PDFDocument39 pagesPust - Migrations From The Venetian To The Ott Territory (16th C.) PDFMegadethNo ratings yet

- The Decline of The Ottoman EmpireDocument7 pagesThe Decline of The Ottoman EmpireNighat BiNo ratings yet

- Out of The Ruins of The Ottoman EmpireDocument21 pagesOut of The Ruins of The Ottoman EmpireDžumhur LejlaNo ratings yet

- The Ottoman EmpireDocument17 pagesThe Ottoman EmpireRoselle AnireNo ratings yet

- Department of Oriental Studies, University of Vienna Wiener Zeitschrift Für Die Kunde Des MorgenlandesDocument12 pagesDepartment of Oriental Studies, University of Vienna Wiener Zeitschrift Für Die Kunde Des MorgenlandesfauzanrasipNo ratings yet

- From The "Turkish Menace" To Exoticism and Orientalism - Islam As Antithesis of Europe (1453-1914) ?Document16 pagesFrom The "Turkish Menace" To Exoticism and Orientalism - Islam As Antithesis of Europe (1453-1914) ?Lynne LarsenNo ratings yet

- Cambridge University Press International Journal of Middle East StudiesDocument7 pagesCambridge University Press International Journal of Middle East StudiesJuan VartzsNo ratings yet

- Week 3.. Darling, Gazi NarrativeDocument41 pagesWeek 3.. Darling, Gazi NarrativeEkin Can GöksoyNo ratings yet

- Preiser WorkingPapersIV ComplexCrisisDocument81 pagesPreiser WorkingPapersIV ComplexCrisisum49420No ratings yet

- Meaning AfDocument12 pagesMeaning AfTurcology TiranaNo ratings yet

- Facts About Ottoman EmpireDocument3 pagesFacts About Ottoman EmpireAlisa Syakila MaharaniNo ratings yet

- Treaty of Bucharest WikipediaDocument2 pagesTreaty of Bucharest WikipediaIdefix1No ratings yet

- Michalis Kourmoulis: BiographyDocument2 pagesMichalis Kourmoulis: BiographyLittle SpidermanNo ratings yet

- Young TurksDocument9 pagesYoung TurksThomas JenningsNo ratings yet

- TAR227U 18V1S1 8 0 1 SV1 EbookDocument231 pagesTAR227U 18V1S1 8 0 1 SV1 EbookUmut YamanNo ratings yet

- 4929 21770 1 PBDocument22 pages4929 21770 1 PBriqi2412No ratings yet

- Tanzimat in The Balkans: Midhat Pasha'S Governorship in The Danube Province (TUNA VILAYETI), 1864-1868Document139 pagesTanzimat in The Balkans: Midhat Pasha'S Governorship in The Danube Province (TUNA VILAYETI), 1864-1868Milan RanđelovićNo ratings yet

- Enver Pasha and His TimesDocument80 pagesEnver Pasha and His TimesMahomad AbenjúcefNo ratings yet

- Attaturk (Week 1-Week13)Document47 pagesAttaturk (Week 1-Week13)shahad hishamNo ratings yet

- Dissolution of The Ottoman Empire: BackgroundDocument18 pagesDissolution of The Ottoman Empire: BackgroundAliNo ratings yet

- Fall of Constantinople Primary SourceDocument2 pagesFall of Constantinople Primary Sourceapi-606623305No ratings yet

- Russo-Ottoman Politics in The Montenegrin-Iskodra Vilayeti Borderland (1878-1912)Document4 pagesRusso-Ottoman Politics in The Montenegrin-Iskodra Vilayeti Borderland (1878-1912)DenisNo ratings yet

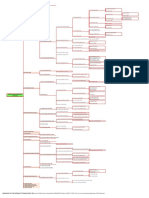

- Arbre Des HamidiensDocument1 pageArbre Des HamidiensAida DianiNo ratings yet

- Middle East 1500 To World War 1 ConflictsDocument3 pagesMiddle East 1500 To World War 1 ConflictsAdrian CabarleNo ratings yet

- Rise and Fall of OttomanDocument2 pagesRise and Fall of OttomanNighat BiNo ratings yet

- Lista de ProductosDocument138 pagesLista de ProductoscomprasindustriaskelNo ratings yet

- Valid TawaeliDocument252 pagesValid TawaeliMisjan MustapaNo ratings yet

- Battle of Pelekanon: Background Clash and Outcome Consequences Notes ReferencesDocument3 pagesBattle of Pelekanon: Background Clash and Outcome Consequences Notes ReferencesFred PianistNo ratings yet

- (Turning Points) Macfie A.L. - The End of The Ottoman Empire, 1908-1923-Addison Wesley (1998) PDFDocument435 pages(Turning Points) Macfie A.L. - The End of The Ottoman Empire, 1908-1923-Addison Wesley (1998) PDFOsman KhanNo ratings yet

- Discurso de Mustafa Kemal (1927)Document2 pagesDiscurso de Mustafa Kemal (1927)Francisco PeláezNo ratings yet

- Discurso de Mustafa Kemal (1927)Document2 pagesDiscurso de Mustafa Kemal (1927)Francisco PeláezNo ratings yet

- Ait103 Corrected 1Document16 pagesAit103 Corrected 1Raymond PakoNo ratings yet

- OttomanDocument3 pagesOttomanhaticesila204No ratings yet

- Dissolution of The EmpireDocument8 pagesDissolution of The EmpireLaloNo ratings yet

- Family of Osman and His RelationsDocument6 pagesFamily of Osman and His RelationsShaikh AdnanNo ratings yet

- Qatar - 5Document1 pageQatar - 5Rohan SharmaNo ratings yet

- Tam Metin DosyasıDocument8 pagesTam Metin DosyasıSüleyman LOKMACINo ratings yet