Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Elasticity of Demand: What You'll Learn To Do: Explain The Concept of Elasticity

Uploaded by

Carla Mae F. DaduralOriginal Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Elasticity of Demand: What You'll Learn To Do: Explain The Concept of Elasticity

Uploaded by

Carla Mae F. DaduralCopyright:

Available Formats

Module 5

Elasticity of Demand

What you’ll learn to do: explain the concept of elasticity

Elasticity is an economics concept that measures the responsiveness of one variable to

changes in another variable. For example, if you raise the price of your product, how will

that affect your sales numbers? The variables in this question are price and sales

numbers. Elasticity explains how much one variable, say sales numbers, will change in

response to another variable, like the price of the product.

Mastering this concept resembles learning to ride a bike: it’s tough at first, but when you

get it, you won’t forget. A rookie mistake is learning the calculations of elasticity but

failing to grasp the idea. Make sure you don’t do this! First take time to understand the

concepts—then the calculations can be used simply to explain them in a numerical way.

Think about the word elastic. It suggests that an item can be stretched. In economics,

when we talk about elasticity, we’re referring to how much something will stretch or

change in response to another variable. Consider a rubber band, a leather strap, and a

steel ring. If you pull on two sides of a rubber band (or Mr. Fantastic), the force will

cause it to stretch a lot. If you use the same amount of force to pull on the ends of a

leather strap, it will stretch somewhat, but not as much as the rubber band. If you pull on

either side of a steel ring, applying the same amount of force, it probably won’t stretch at

all (unless you’re very strong). Each of these materials (the rubber band, the leather

strap, and the steel ring) displays a different amount of elasticity in response to being

pulled, and all three fall somewhere on a continuum from very stretchy (elastic) to

barely stretchy (inelastic).

There are different kinds of economic elasticity—for example, price elasticity of demand,

price elasticity of supply, income elasticity of demand, and cross-price elasticity of

demand—but the underlying property is always the same: how responsive or sensitive

one thing is to a change in another thing.

Elastic and Inelastic Demand

Let’s think about elasticity in the context of price and quantity demanded. While the law

of demand does tell us that more of a good will be bought at a lower price, it does not

tell us how much the quantity demanded will increase because of the price change. For

example, if a store owner raises prices, she can expect that the quantity demanded will

drop, but she might not know how sensitive customers will be to the change. How many

people will buy her products despite the price increase and how many people will be

driven away?

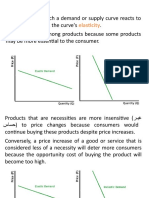

If a small change in price creates a large change in the quantity demanded, then we

would say that the demand is very elastic—that is, the demand is very sensitive to a

change in price. If, on the other hand, a large change in price results in a very small

change in demand in the quantity demanded, then we would say the demand

is inelastic. As we will see later, elastic and inelastic are relative concepts. Here’s

a way to keep this straight: demand is inelastic when consumers are insensitive to

changes in price.

Consider the example of cigarette taxes and smoking rates—a classic example of

inelastic demand. Cigarettes are taxed at both the state and federal level. As you might

expect, the greater the amount of the tax increase, the fewer cigarettes are bought and

consumed. While the taxes are somewhat of a deterrent, demand doesn’t decrease as

much as the price increase, though. We can say, then, that the demand for cigarettes is

relatively inelastic.

You might think that elasticity isn’t an important consideration when it comes to the price

of cigarettes. Surely any reduction in the demand for cigarettes would be a good thing,

right? Does it really matter whether whether the demand is elastic or inelastic? It does.

The reason is that taxes on cigarettes serve two purposes: to raise tax revenue for

government and to discourage smoking. On one hand, if a higher cigarette tax

discourages consumption by quite a lot—meaning a very large reduction in cigarette

sales—then the cigarette tax on each pack will not raise much revenue for the

government. On the other hand, a higher cigarette tax that does not discourage

consumption by much will actually raise more tax revenue for the government (but not

have much impact on smoking rates). Thus, when Congress tries to calculate the

effects of altering its cigarette tax, it must analyze how much the tax affects the quantity

of cigarettes consumed. In other words, understanding the elasticity of cigarette

demand is key to measuring the impact of taxes on government revenue AND public

health.

https://courses.lumenlearning.com/wmopen-microeconomics/chapter/elasticity-of-demand/

You might also like

- League Bowling Training HandoutDocument22 pagesLeague Bowling Training HandoutAdam OgelsbyNo ratings yet

- Price Elasticity Week 5Document38 pagesPrice Elasticity Week 5Katrina LabisNo ratings yet

- Concepts of Elasticity Luke - 124908Document27 pagesConcepts of Elasticity Luke - 124908edseldelacruz333No ratings yet

- CONCEPT of ELASTICITYDocument60 pagesCONCEPT of ELASTICITYBjun Curada LoretoNo ratings yet

- Subsea Innovation Pipeline RepairDocument7 pagesSubsea Innovation Pipeline RepairVeena S VNo ratings yet

- Assignment Economic Stud 1Document9 pagesAssignment Economic Stud 1Masri Abdul LasiNo ratings yet

- Project On Elasticity of DemandDocument11 pagesProject On Elasticity of Demandjitesh82% (50)

- Boq & SC For Paint AmcDocument4 pagesBoq & SC For Paint AmcTusar KoleNo ratings yet

- Chapter 2 Demand and SupplyDocument34 pagesChapter 2 Demand and SupplyAbdul-Mumin AlhassanNo ratings yet

- Project Report On Tyre RetreadingDocument9 pagesProject Report On Tyre RetreadingEIRI Board of Consultants and PublishersNo ratings yet

- Anchors: Handling, Storage, Installation and Maintenance ManualDocument30 pagesAnchors: Handling, Storage, Installation and Maintenance Manualpandu lambangNo ratings yet

- The Relationship Between The Price of A Good and How Much of It SB Wants To BuyDocument6 pagesThe Relationship Between The Price of A Good and How Much of It SB Wants To Buy3.Lưu Bảo AnhNo ratings yet

- Micro Vs Macro EconomicsDocument22 pagesMicro Vs Macro Economicsrics_alias087196No ratings yet

- Lesson 7 ElasticityDocument8 pagesLesson 7 ElasticityleblanjoNo ratings yet

- Objectives For Chapter 4: Elasticity and Its ApplicationDocument19 pagesObjectives For Chapter 4: Elasticity and Its ApplicationAnonymous BBs1xxk96VNo ratings yet

- What Is 'Elasticity'Document6 pagesWhat Is 'Elasticity'Joyce ballescas100% (1)

- ELASTICITY of DemandDocument16 pagesELASTICITY of DemandKyla TorcatosNo ratings yet

- Microeconomics - Internal AssignmentDocument9 pagesMicroeconomics - Internal AssignmentAratrika SinghNo ratings yet

- Elasticity in Economics & BeyondDocument19 pagesElasticity in Economics & BeyondHarishNo ratings yet

- I 4 0 EC Introduction-Elasticity-UtilityDocument39 pagesI 4 0 EC Introduction-Elasticity-UtilityDaliah Abu JamousNo ratings yet

- Price Elasticity of Demand: Price Elasticity % Change in Quantity / % Change in PriceDocument13 pagesPrice Elasticity of Demand: Price Elasticity % Change in Quantity / % Change in PriceMarielle SisonNo ratings yet

- Unit 3 - Demand and SupplyDocument32 pagesUnit 3 - Demand and SupplyLillian NgubaniNo ratings yet

- Aasignment - Elasticity of DemandDocument15 pagesAasignment - Elasticity of Demandacidreign100% (1)

- ElasticitiesDocument4 pagesElasticitiesEsfar JawadNo ratings yet

- Elasticity (Economy)Document42 pagesElasticity (Economy)Весна ЛетоNo ratings yet

- Economics Basics: Elasticity: Sponsor: Cook Up A Market-Stomping Stock Portfolio With Our FREE ReportDocument4 pagesEconomics Basics: Elasticity: Sponsor: Cook Up A Market-Stomping Stock Portfolio With Our FREE ReportamitkumartechnowizeNo ratings yet

- Managerial EconomicsDocument9 pagesManagerial Economicsnehaupreti86No ratings yet

- Demand - Supply 2Document13 pagesDemand - Supply 2Mazen YasserNo ratings yet

- AEG114 - Final Assessment - ReadingDocument6 pagesAEG114 - Final Assessment - ReadingNguyễn AnNo ratings yet

- Lesson 1 - Introduction To Elasticity - Managerial EconomicsDocument3 pagesLesson 1 - Introduction To Elasticity - Managerial EconomicsLovely MontederamosNo ratings yet

- Group 5 - Group Assignment - ECO111Document6 pagesGroup 5 - Group Assignment - ECO111Trần Thị Thu Hiền K17 HLNo ratings yet

- Elasticity Continued : Determinants of Price Elasticity of DemandDocument24 pagesElasticity Continued : Determinants of Price Elasticity of Demandfoyzul 2001No ratings yet

- Reaction Paper ElasticityDocument2 pagesReaction Paper Elasticityelizabeth_cruz_53100% (1)

- Eco ProjectDocument22 pagesEco ProjectShashiRaiNo ratings yet

- Lesson 6 AnswersDocument7 pagesLesson 6 AnswersAbegail BlancoNo ratings yet

- downloadEconomicsA LevelNotesEdexcel ATheme 1Summary1.2.20How20Markets20Work PDFDocument37 pagesdownloadEconomicsA LevelNotesEdexcel ATheme 1Summary1.2.20How20Markets20Work PDFotsuaigbodesiNo ratings yet

- Business Economics BCADocument25 pagesBusiness Economics BCAamjoshuabNo ratings yet

- Module 2 - The Basic Theory Using Demand and SupplyDocument20 pagesModule 2 - The Basic Theory Using Demand and Supplykyle markNo ratings yet

- How Markets Work SummaryDocument37 pagesHow Markets Work SummaryGavin WongNo ratings yet

- Econ124 Chapter 5Document5 pagesEcon124 Chapter 5Piola Marie LibaNo ratings yet

- Assignment 2Document7 pagesAssignment 2Art EastNo ratings yet

- Demand and Consumer BehaviourDocument6 pagesDemand and Consumer BehaviourshubhamNo ratings yet

- Final Notes For QTMDocument24 pagesFinal Notes For QTMsupponiNo ratings yet

- Economics Chapter 5 SummaryDocument6 pagesEconomics Chapter 5 SummaryAlex HdzNo ratings yet

- Final Exam ManaDocument7 pagesFinal Exam Manaale montalvnNo ratings yet

- 2manegerial Economics Module 5Document4 pages2manegerial Economics Module 5kim fernandoNo ratings yet

- Chapter 3: Demand, Supply, and Market Equilibrium 16Document15 pagesChapter 3: Demand, Supply, and Market Equilibrium 16Karen Delos Reyes SolanoNo ratings yet

- The Market Forces of Supply & DemandDocument37 pagesThe Market Forces of Supply & Demandhasanimam mahiNo ratings yet

- Price DiscriminationDocument58 pagesPrice DiscriminationBalamani Kandeswaran M100% (1)

- Procurement Practitioners Will Only Add Sustainable Value To An Organisation's Bottom-Line If They Understand The Environment in Which They OperateDocument85 pagesProcurement Practitioners Will Only Add Sustainable Value To An Organisation's Bottom-Line If They Understand The Environment in Which They OperateBenjamin Adelwini BugriNo ratings yet

- Economics NotesDocument75 pagesEconomics NotesLoverofAliNo ratings yet

- What Is 'Elasticity'Document4 pagesWhat Is 'Elasticity'Helena MontgomeryNo ratings yet

- Elasticity NotesDocument11 pagesElasticity NotesQueenie Joy GadianoNo ratings yet

- Resources 2Document6 pagesResources 2kerminabosyNo ratings yet

- Introduction To EconomicsDocument7 pagesIntroduction To EconomicsKavafyNo ratings yet

- Eco561 Lecture+NotesDocument71 pagesEco561 Lecture+NotesRolando RodriguezNo ratings yet

- Module No. 2 Lesson 1 ABM112Document10 pagesModule No. 2 Lesson 1 ABM112Rush RushNo ratings yet

- MBA-I Semester Managerial Economics MB0026: For More Solved Assignments, Assignment and Project Help - Visit - orDocument12 pagesMBA-I Semester Managerial Economics MB0026: For More Solved Assignments, Assignment and Project Help - Visit - orRohit MukherjeeNo ratings yet

- Final Summary of ElasticityDocument3 pagesFinal Summary of ElasticityJeffrey FernandezNo ratings yet

- Elasticity of DemandDocument21 pagesElasticity of Demandapi-262416934No ratings yet

- 2013 Half Yearly Exam SolutionsDocument5 pages2013 Half Yearly Exam SolutionsBinnie KaurNo ratings yet

- Unit - 2 Meaning of DemandDocument12 pagesUnit - 2 Meaning of DemandmussaiyibNo ratings yet

- p1 Be313Document3 pagesp1 Be313Febemay LindaNo ratings yet

- Regulating Natural MonopoliesDocument5 pagesRegulating Natural MonopoliesCarla Mae F. DaduralNo ratings yet

- Negative Externalities: PollutionDocument8 pagesNegative Externalities: PollutionCarla Mae F. DaduralNo ratings yet

- Causes of Growing Inequality: Changing Composition of American HouseholdsDocument3 pagesCauses of Growing Inequality: Changing Composition of American HouseholdsCarla Mae F. DaduralNo ratings yet

- Equilibrium, Surplus, and ShortageDocument4 pagesEquilibrium, Surplus, and ShortageCarla Mae F. DaduralNo ratings yet

- Economies of ScaleDocument5 pagesEconomies of ScaleCarla Mae F. DaduralNo ratings yet

- The Shutdown Point: Scenario 1Document10 pagesThe Shutdown Point: Scenario 1Carla Mae F. DaduralNo ratings yet

- Rules For Maximizing UtilityDocument7 pagesRules For Maximizing UtilityCarla Mae F. DaduralNo ratings yet

- Profit Maximization For A Monopoly: Demand Curves Perceived by A Perfectly Competitive Firm and by A MonopolyDocument8 pagesProfit Maximization For A Monopoly: Demand Curves Perceived by A Perfectly Competitive Firm and by A MonopolyCarla Mae F. DaduralNo ratings yet

- Employment Discrimination: Earnings Gaps by Race and GenderDocument7 pagesEmployment Discrimination: Earnings Gaps by Race and GenderCarla Mae F. DaduralNo ratings yet

- Labor Market Power by EmployersDocument7 pagesLabor Market Power by EmployersCarla Mae F. DaduralNo ratings yet

- Supply and Demand in Labor MarketsDocument4 pagesSupply and Demand in Labor MarketsCarla Mae F. DaduralNo ratings yet

- The Role of The GATT in Reducing Barriers To TradeDocument6 pagesThe Role of The GATT in Reducing Barriers To TradeCarla Mae F. DaduralNo ratings yet

- Figure 1. A Production Possibilities Frontier Showing Health Care and EducationDocument2 pagesFigure 1. A Production Possibilities Frontier Showing Health Care and EducationCarla Mae F. DaduralNo ratings yet

- The Foundations of The Demand CurveDocument4 pagesThe Foundations of The Demand CurveCarla Mae F. DaduralNo ratings yet

- Outcome: Entry and Exit DecisionsDocument4 pagesOutcome: Entry and Exit DecisionsCarla Mae F. DaduralNo ratings yet

- Market-Oriented Environmental Tools: Effluent ChargesDocument6 pagesMarket-Oriented Environmental Tools: Effluent ChargesCarla Mae F. DaduralNo ratings yet

- Trade and Efficiency: Getting A Good Deal or Making A Good DealDocument3 pagesTrade and Efficiency: Getting A Good Deal or Making A Good DealCarla Mae F. DaduralNo ratings yet

- Regulating Anticompetitive BehaviorDocument7 pagesRegulating Anticompetitive BehaviorCarla Mae F. DaduralNo ratings yet

- Outcome: Math in Economics: What You'll Learn To Do: Use Mathematics in Common Economic ApplicationsDocument5 pagesOutcome: Math in Economics: What You'll Learn To Do: Use Mathematics in Common Economic ApplicationsCarla Mae F. DaduralNo ratings yet

- Customers and Changing CostsDocument3 pagesCustomers and Changing CostsCarla Mae F. DaduralNo ratings yet

- Outcome: The Shutdown PointDocument10 pagesOutcome: The Shutdown PointCarla Mae F. DaduralNo ratings yet

- Unit 1: Introduction To EconomicsDocument2 pagesUnit 1: Introduction To EconomicsCarla Mae F. DaduralNo ratings yet

- Reading: Measuring Income Inequality: How Do You Separate Poverty and Income Inequality?Document6 pagesReading: Measuring Income Inequality: How Do You Separate Poverty and Income Inequality?Carla Mae F. DaduralNo ratings yet

- Profit Maximization Under Monopolistic Competition: Choosing The Profit-Maximizing Output and PriceDocument5 pagesProfit Maximization Under Monopolistic Competition: Choosing The Profit-Maximizing Output and PriceCarla Mae F. DaduralNo ratings yet

- Reading: The Production Possibilities FrontierDocument9 pagesReading: The Production Possibilities FrontierCarla Mae F. DaduralNo ratings yet

- Government Policies To Reduce Income InequalityDocument6 pagesGovernment Policies To Reduce Income InequalityCarla Mae F. DaduralNo ratings yet

- 122333Document2 pages122333Carla Mae F. DaduralNo ratings yet

- Behavioral Economics: An Alternative Viewpoint: Irrational Consumer BehaviorDocument2 pagesBehavioral Economics: An Alternative Viewpoint: Irrational Consumer BehaviorCarla Mae F. DaduralNo ratings yet

- The Economists' Tool Kit: Lea RN in G Obj Ectiv EsDocument7 pagesThe Economists' Tool Kit: Lea RN in G Obj Ectiv EsCarla Mae F. DaduralNo ratings yet

- Positive and Normative StatementsDocument2 pagesPositive and Normative StatementsCarla Mae F. DaduralNo ratings yet

- Plastic Mark SpecificationsDocument16 pagesPlastic Mark SpecificationszuconjaNo ratings yet

- Din 6311Document1 pageDin 6311Dule JovanovicNo ratings yet

- Introduction To Synchronous BeltsDocument63 pagesIntroduction To Synchronous BeltsAnonymous fQAeGFNo ratings yet

- BrochureDocument11 pagesBrochureDieguitoOmarMoralesNo ratings yet

- 7314 E SiliconeSealants WNDocument6 pages7314 E SiliconeSealants WNAlanoud AlmutairiNo ratings yet

- Leaflets AXIS.14.02.001Document2 pagesLeaflets AXIS.14.02.001EriIlyasaNo ratings yet

- MCPP Series: Centrifugal Process PumpDocument8 pagesMCPP Series: Centrifugal Process PumpOmar SunasaraNo ratings yet

- A Report On Industrial Visit To Relaxo Footwear Limited's Manufacturing Unit III, Bhiwadi, Dist. Alwar (Rajasthan)Document10 pagesA Report On Industrial Visit To Relaxo Footwear Limited's Manufacturing Unit III, Bhiwadi, Dist. Alwar (Rajasthan)DineshYadavNo ratings yet

- Sanitary Fittings and Tubes: The Complete LineDocument6 pagesSanitary Fittings and Tubes: The Complete LineFelipe Cruvinel DamascenoNo ratings yet

- TEB0041 - Rubber BrochureDocument12 pagesTEB0041 - Rubber BrochureChetal BholeNo ratings yet

- Shri SK Bagchi OISD PDFDocument25 pagesShri SK Bagchi OISD PDFM Kumar KumarNo ratings yet

- Styrenated Phenol Cristol SP SeriesDocument1 pageStyrenated Phenol Cristol SP SeriesTejas SalianNo ratings yet

- IDS 302 1001 002 General Purpose MEK BlackDocument3 pagesIDS 302 1001 002 General Purpose MEK BlackFarid DiazNo ratings yet

- The Ford Firestone CaseDocument8 pagesThe Ford Firestone CaseRoman -No ratings yet

- Mukul Shankhwar JK TyreDocument44 pagesMukul Shankhwar JK Tyrevishnu0751No ratings yet

- 4190 HPRVDocument12 pages4190 HPRVvadivel415No ratings yet

- Power Transmission & Conveyor BeltsDocument16 pagesPower Transmission & Conveyor BeltsSumanth AttadaNo ratings yet

- Aerosil R 974 - Evonik PDFDocument2 pagesAerosil R 974 - Evonik PDFZaimi Husni HussainNo ratings yet

- 9732 Hydraulic Seals Technical Manual 270513 PDFDocument20 pages9732 Hydraulic Seals Technical Manual 270513 PDFEdwin AraqueNo ratings yet

- Cabot Corporation As3586Document6 pagesCabot Corporation As3586Abhijeet SinghNo ratings yet

- APODocument82 pagesAPOamandp83No ratings yet

- RAVO Genuine Parts BrushesDocument3 pagesRAVO Genuine Parts BrushesEsteban RetrepoNo ratings yet

- Tolerances: Guide To Standard Industry TolerancesDocument2 pagesTolerances: Guide To Standard Industry Tolerancespk cfctkNo ratings yet

- Polyflon Ptfe D-210: Aqueous DispersionDocument1 pagePolyflon Ptfe D-210: Aqueous DispersionRajanSharmaNo ratings yet