Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Sage Publications, Inc. Johnson Graduate School of Management, Cornell University

Uploaded by

Marielle LituanasOriginal Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Sage Publications, Inc. Johnson Graduate School of Management, Cornell University

Uploaded by

Marielle LituanasCopyright:

Available Formats

Professional Autonomy and Bureaucratic Organization

Author(s): Gloria V. Engel

Source: Administrative Science Quarterly, Vol. 15, No. 1 (Mar., 1970), pp. 12-21

Published by: Sage Publications, Inc. on behalf of the Johnson Graduate School of Management, Cornell

University

Stable URL: http://www.jstor.org/stable/2391182 .

Accessed: 28/11/2013 01:20

Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of the Terms & Conditions of Use, available at .

http://www.jstor.org/page/info/about/policies/terms.jsp

.

JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide range of

content in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and facilitate new forms

of scholarship. For more information about JSTOR, please contact support@jstor.org.

Sage Publications, Inc. and Johnson Graduate School of Management, Cornell University are collaborating

with JSTOR to digitize, preserve and extend access to Administrative Science Quarterly.

http://www.jstor.org

This content downloaded from 35.8.11.2 on Thu, 28 Nov 2013 01:20:29 AM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

Gloria V. Engel

Professional Autonomy and BureaucraticOrganization

Autonomy is regarded as an important dimension of professionalism. A number

of investigators claim that bureaucratic organization limits professional auton-

omy. This study was undertaken to determine empirically the validity of this

claim. The relationship between bureaucratic structure and degree of professional

autonomy within the client-professional relationship was examined by system-

atically comparing the perceived autonomy of professionals in three types of

bureaucratic settings, nonbureaucratic, moderately bureaucratic, and highly

bureaucratic. The data revealed that those professionals associated with the

moderately bureaucratic setting are most likely and those in the highly bureau-

cratic setting are least likely to perceive themselves as autonomous. These find-

ings do not support the contention that bureaucracy is necessarily detrimental to

professional autonomy.

Much of the literature on organizations anecdotal and general, this study was under-

shares an antibureaucratic orientation (cf. taken to determine empirically whether

Hickson, 1966). Because such factors as in- bureaucratic organization does limit in-

novative behavior, upward and lateral com- dividual professional autonomy.' Goode

munication, and individual responsibility are (1960:903) has stated that "the two ... core

not strongly evidenced in a bureaucratic characteristics [of a profession] are a pro-

structure, it is portrayed as nonviable for longed specialized training in a body of

many types of organizations. The reduced abstract knowledge and a . .. service orien-

range of activities or discretions permitted tation." This definition will be used in this

within bureaucracies is assumed to bring article.

about lowered influence and autonomy for As an ideal, typical conceptualization,

those associated with them. professional autonomy can be viewed as

Merton (1957), Mills (1951), Lewis and existing on two separate but related levels:

Maude (1953), and other investigators (1) with respect to the individual profes-

(White, 1957; Ben-David, 1958; Bendix, sional, and (2) with respect to the occupa-

1960; Dixon, 1964; Goldner and Ritti, 1967; tional group or profession. The former is

Hall, 1968; and Daniels, 1969) contend that the concern of this paper and is refined into

bureaucracy can be particularly detrimental personal and work-related autonomy.

to the professions because it limits auton- Personal autonomy is freedom to conduct

omy, an important element of professional- tangential work activities in a normative

ism. Other investigators, however, do not manner in accordance with one's own dis-

regard bureaucracy as completely harmful cretion. Work-related autonomy for the

to the professional (Barnard, 1938; Blau, professional is freedom to practice his pro-

1955; Goss, 1959; Janowitz, 1960; Dalton, fession in accordance with his training. It is

1961; Kornhauser, 1962; Glaser, 1964; and this type of autonomy which appears to be

Bucher and Stelling, 1967). Since everyone important for the professional, since a loss

is increasingly dependent upon professional of work-related autonomy or control to his

services, and since today's professionals are

1 The author acknowledges the

entering bureaucratic organizations in larger help given by Ray-

mond J. Murphy of the University of Rochester.

numbers, it is expedient to determine An abridged version of this paper was presented at

whether these allegations can be substan- the American Sociological Association meeting in

tiated. Because much of the literature is San Francisco, 1969.

12

This content downloaded from 35.8.11.2 on Thu, 28 Nov 2013 01:20:29 AM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

Engel: PROFESSIONAL AUTONOMY 13

client, or to any lay individual or group, studied because their occupation has been

might reduce the quality of the service he widely used as the basis for the traditional

renders. The studies instigated by the concept of a profession by both laymen and

Human Relations School (Roethlisberger social scientists (cf. Flexner, 1915; Carr-

and Dickson, 1939; Mayo and Lombard, Saunders and Wilson, 1933; Marshall, 1939;

1944), which stressed the importance of Cogan, 1953; Parsons, 1954; Goode, 1957

personal freedom and morale to the per- and 1960; Bucher and Strauss, 1961; Becker,

formance of the worker, have pointed out 1962; Wilensky, 1964; and Bullough, 1966).

the importance of personal autonomy. Be-

cause of the theoretical separation of in- SAMPLE

dividual autonomy into personal and work- A total of 1,628 questionnaires was sent to

related autonomy, variables suggested by physicians who work in (1) solo or small

the Human Relations School which are re- group practice, (2) a privately owned,

lated to personal autonomy will be controlled closed-panel medical organization, and (3)

so that findings related to work autonomy a governmentally associated medical or-

can be interpreted. The range of activities ganization. Of the 684 (42 percent) returns,

in which a loss of work-related autonomy is 40 percent (230 of 580) were received from

most likely to be a problem for the pro- those in solo practice, 54 percent (276 of

fessional is examined in this study. 520) from those in the privately owned

The definition of bureaucracy used was medical organization, and 34 percent (178

derived from the Weberian tradition, with of 528) from those in the governmentally

some modification. Weber conceived of associated organization. While the physi-

bureaucracy as an administrative structure cians in solo practice were selected by

based on legal domination, highly rational random sampling procedures, the total pop-

in its organization, and therefore effective ulation of physicians in the two organiza-

for goal attainment (Blau and Scott, 1962). tions was used to obtain a sufficiently large

The definition considered the effect of both sample.

the administrative structure with which

Weber dealt-in particular, the hierarchical Solo Practitioners

authority structure and the rules and regula- The solo practitioners were sampled from

tions-and the physical structure, which in- a highly urbanized area in California. They

cludes the amount and types of supplies, worked in an office obtained and equipped

tools, and large items of equipment with with their own funds and attended patients

which work is performed, the number of who had voluntarily chosen them as their

men working together in a department or physicians on a fee for service basis. Most

section, and the availability of funds for respondents were specialists: 15 percent

such endeavors as research and continuing were internists, 60 percent were in other

education. Since the authority structure of specialties, and 25 percent were general

bureaucracies is more rigid and confining practitioners. Although the major work task

than that of the professions (Blau and Scott, for most was clinical practice, approximately

1962), if a professional works in a bureau- 30 percent had part-time clinical appoint-

cracy, he could undergo a loss of autonomy. ments at a medical school. Only a small per-

centage participated in clinical research.

HYPOTHESIS All sampled solo physicians were members

It was hypothesized that as the degree of of the local and national medical societies

bureaucracy increased, professional auton- and were affiliated with at least one private,

omy would decrease. This hypothesis was accredited hospital, varying in bed size from

tested by comparing degree of autonomy 20 to 500. The respondents' modal salaries

with respect to both clinical practice and were $35,000 or more. A small number of

clinical research as perceived by three solo practitioners was interviewed to obtain

groups of physicians employed in a highly a close range perspective of their perceived

bureaucratic, a moderately bureaucratic, and autonomy. Most of the interviewees claimed

a nonbureaucratic setting. Physicians were to be highly autonomous.

This content downloaded from 35.8.11.2 on Thu, 28 Nov 2013 01:20:29 AM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

14 ADMINISTRATIVE SCIENCE QUARTERLY

Physicians in the Privately Owned physician from those who worked in the

Organization organization, and the physician was per-

mitted to care only for those patients who

The physicians in the closed-panel medi-

were members of the health plan. A physi-

cal group provided medical services within

cian was assigned to a patient, unless the

an integrated clinic and/or hospital to pa-

patient requested a specific doctor.

tients who had voluntarily joined a prepaid

health plan. More than 500 salaried physi-

cians worked in this organization. Their Physicians in the Governmentally

modal salary was in the $25,000 to $30,000 Associated Organization

range. Approximately 17 percent were gen- The physicians in the governmentally asso-

eral practitioners, 27 percent were internists, ciated organization provided medical care

and the remainder were members of other for a select group of individuals who quali-

specialties. While the organization was not fied under federal regulations. The organiza-

officially associated with any university med- tion employed more than 500 physicians,

ical school, 33 percent of the physicians had about the same number as the privately

part-time teaching appointments. owned bureaucracy. Four percent were gen-

As with solo practitioners, the major goal eral practitioners, 37 percent were internists,

of this organization was the clinical practice and the remainder were engaged in other

of medicine, although clinical research could specialties.

be undertaken by those interested. The or- The four subunits of this organization

ganization was headed by a medical director studied were in the same geographical area

and was divided into five subunits, all lo- as the other two groups. Between 20 and

cated in a highly urbanized area of Cali- 200 physicians were associated with these

fornia. Each subunit was organized into de- subunits.

partments according to medical specialty While this organization was similar to the

and was affiliated with a modern, well- privately owned bureaucracy with regard to

equipped general hospital, which varied in the type and accessibility of hospital facili-

size from 170 to 450 beds. Between 30 and ties, it differed in number of hospital beds,

200 physicians were associated with each freedom of choice between physician and

subunit. Business administrative services patient, and patient population. The hospital

were provided by a nonmedical service cor- sizes varied from 519 to 1,675 beds; patients

poration. were assigned to the physicians who, in turn,

The organization was structured so that a were permitted to treat only those who

physician could become a profit-sharing part- qualified under governmental regulations;

ner, as well as a salaried employee, after and its patient population was not represen-

three years of full-time employment. Ap- tative of the community, most being males

proximately 350 physicians in the organiza- with chronic illnesses.

tion were partners. As with solo practice and the privately

The partnership was carried on by a board owned organization, one of the major activ-

of directors, consisting of 13 elected and 7 ities of the governmentally associated or-

ex officio members who were directly re- ganization was clinical medical practice.

sponsible to the partnership members. Since However, research and teaching were also

they were incorporated within the authority stressed, and financial provisions were made

structure, the partners had substantial con- in each of the subunits for those who wanted

trol over organizational policies. to participate in clinical research. The sub-

The organization's patient population was units were also used as teaching settings,

quite similar to that treated by the physi- with the local university medical school

cians in solo practice and represented a supplying a number of consultants and de-

cross-section of the community. The free- partmental chiefs who, in turn, provided in-

dom of choice between patient and physi- struction to residents and interns. Three

cian found in individual practice was re- hundred residents and 36 interns were asso-

duced, since the patient had to select his ciated with the organization. Almost half of

This content downloaded from 35.8.11.2 on Thu, 28 Nov 2013 01:20:29 AM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

Engel: PROFESSIONAL AUTONOMY 15

all physicians in the organization held part- changes in policy had to be set and ap-

time teaching appointments. proved from a geographical distance. By

The governmentally employed physician contrast, the policies of the privately owned

had no opportunity to become a partner in bureaucracy were mainly determined within

the organization. He could attain higher the structure.

rank only if such a position became avail- A larger number of rules and regulations

able, and he remained an employee as long existed in the governmentally associated

as he was associated with the organization. than in the privately owned setting. When

Higher positions were awarded on the basis the operating manuals and other printed

of ratings which physicians received from materials from the two organizations were

their superiors. compared and information from interviews

Interviews were also conducted with a with physicians employed by the two orga-

small number of physicians from the pri- nizations was evaluated, it was noted that the

vately owned and governmentally associated former had approximately four times as

organizations to obtain the flavor of the au- many recorded rules related to patient care

tonomy in these two settings. As with the as the latter. In many instances these rules

solo practitioners, the majority in both or- were more specific and covered a greater

ganizations attested to their autonomy. Most number of the physicians' activities. The

stated that practicing in an organization was physicians were also required to fill out ap-

no different from practicing solo. proximately twice as many forms related to

patient care as those in the privately owned

VARIABLES AND MEASURES organization.

Independent Variable: Degree of Dependent Variable: Degree of

Bureaucracy Professional Autonomy

The degree of bureaucratization of the In his relationship with his client, the pro-

three settings was determined by noting fessional is usually expected to be autono-

(1) the number of hierarchical levels in mous with respect to such factors as respon-

each setting, (2) the degree to which rules sibility, communication, and innovation, if

and regulations were utilized, and (3) the he is to provide adequate service (Engel,

presence or absence of a physical setting in 1968). He assumes the responsibility for his

which work could be performed in teams or client's welfare because he is more knowl-

groups. edgeable and is acting on his client's behalf.

The settings used represented three dif- He defines the problem, determines proce-

ferent levels of bureaucratic organization: dures, and is accountable for the adequacy

nonbureaucratic, moderately bureaucratic, of his services.

and highly bureaucratic. Solo practice was However, the professional should be free

classified as nonbureaucratic because most to communicate with his client and with his

of the elements defined as bureaucratic were fellow professionals. He should have access

only indirectly present in this type of medi- to privileged information concerning his

cal practice. The governmentally associated client, and he should be free to communi-

organization was categorized as highly bu- cate with those in his field who might pos-

reaucratic and the privately owned orga- sess information which could help him

nization as moderately bureaucratic for the render a better service to his client.

following reasons. The professional should also be able to

When the formal organizational charts innovate. Each client's problem tends to

were compared, the authority structure of require a singular solution. The professional

the governmental organization was noted to should be able to alter typical procedures or

have a greater number of hierarchical levels instigate changes necessary for the solution

than that of the privately owned organiza- of the specific problem.

tion. Because the center of authority, the Professional autonomy within the client-

administrative head, was not located within professional relationship was therefore di-

the local organization, new policies and vided into three dimensions-autonomy

This content downloaded from 35.8.11.2 on Thu, 28 Nov 2013 01:20:29 AM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

16 ADMINISTRATIVE SCIENCE QUARTERLY

with regard to innovation, individual respon- sional relationship was then related to the

sibility, and communication-which were degree of bureaucracy.

operationalized as follows.

Autonomy with regard to innovation ex- FINDINGS AND CONCLUSIONS

isted when the physician instigated changes Table 1 shows that a greater percentage

related to work tasks, was responsible for of the physicians in the moderately bureau-

TABLE 1. CLINICAL PRACTICE AND RESEARCH AUTONOMY BY BUREAUCRACY

Professional autonomy

Low Medium High

Bureaucracy S % % N X2-test

Low 40.8 35.5 23.7 152 2= 66.96

Medium 14.0 34.8 51.1 221 4 df

High 46.2 32.1 21.8 156 p < .001

origination, altered established work meth- cratic setting perceived themselves as high

ods, and produced novel ideas and/or in autonomy than in either of the other two

methods. Autonomy with regard to individ- settings. A slightly greater percentage of

ual responsibility occurred when the physi- those in the nonbureaucratic setting saw

cian determined the uses to which his work themselves as moderately autonomous than

was put, was not subordinate to those less those in either of the other two settings,

knowledgeable, defined his own work goals, while a greater percentage of those in the

and was permitted to act and think without highly bureaucratic setting perceived them-

interference. A physician was autonomous selves as low in autonomy.

with regard to free communication when he The findings did not support the hypoth-

had access to all vital information, could esis concerning the inverse relationship be-

communicate without interference or obsta- tween degree of bureaucracy and degree of

cles, and participated in democratically or- autonomy. They might, however, be spuri-

ganized discussions. ous. The apparent anomaly concerning the

A professional autonomy questionnaire lower perceived autonomy of the individual

was designed to determine the degree of practitioners, as compared with physicians

autonomy which the members of each group in the privately owned organization, re-

possessed. It dealt with the physicians' per- quires further examination. Perhaps some

ceptions of their autonomy with regard to of the other variables on which the solo and

clinical practice (part I) and research (part organizational physicians differed could ac-

II) and with the various relevant control count for the results.

variables (part III). The solo practitioners appeared to be the

Since the data did not lend themselves to more highly professional group. Their modal

Guttman-scaling techniques, two Likert-type, salaries were higher. They were more active

professional autonomy scales were con- in their professional organizations, sub-

structed from the responses to parts I and scribed to a larger number of journals, and

II of the questionnaire. Each scale was con- enrolled in more graduate courses. Accord-

sidered to represent a separate aspect of ingly, they should have been more, rather

autonomy. They were combined to form a than less, autonomous.

third, overall autonomy scale. One background variable on which the

Each of the three scales was empirically groups differed, and which might partially

divided into thirds. The upper third was account for the lower perceived autonomy

designated as high autonomy, the middle of the solo physicians, was type of medical

third as moderate autonomy, and the lower specialty, if any. Depending on their spe-

third as low autonomy. The degree of per- cialty, solo physicians tended to have dif-

ceived autonomy within the client-profes- ferent referral sources.

This content downloaded from 35.8.11.2 on Thu, 28 Nov 2013 01:20:29 AM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

Engel: PROFESSIONAL AUTONOMY 17

Freidson ( 1960) pointed out that there those who had prepaid, and were required

were two basic sources of referrals: client to use, the organization for all medical ex-

and colleague. Individual general practition- igencies.

ers maintained their practices mainly by re- Further, even though the social, economic,

ferrals from their clients. Most solo medical and religious characteristics of the privately

specialists obtained referrals primarily from owned organization's clients were quite

colleagues (Hall, 1948). Internists had two similar to those of solo physicians, the clients

sources of referrals, colleagues and clients, probably differed with respect to their psy-

and it is likely that they were less dependent chological makeup. Perhaps those who pa-

on either source and thus more autonomous tronized solo physicians did not join prepaid

than the general practitioners or the other medical plans because they preferred to ex-

specialists. Because the sample of solo physi- ercise more control over their choice of

cians contained both a greater percentage of physicians. Several patients of solo physi-

general practitioners and specialists other cians who were interviewed remarked that

than internists, the groups were separated they would not be interested in going to a

by medical specialty to determine the effect clinic or joining a prepaid group because

of this variable. they might not be able to get the same physi-

The type of medical specialty as it related cian whenever they needed him. Others just

to client and colleague control had little wanted the freedom to choose their own

effect on the individual practitioner's per- doctor.

ception of his autonomy, as Table 2 shows. The three groups of physicians also dif-

TABLE 2. AUTONOMY AND BUREAUCRACY BY MEDICAL SPECIALTY

Professional autonomy

Low Medium High

Bureaucracy % % % N X2-test

General practitioner

Low 48.4 41.9 9.7 31 X2= 6.78

Medium 33.3 30.6 36.1 36 4 df

High 50.0 33.3 16.7 6 P > .10

Internist

Low 26.1 43.5 30.4 23 2 = 14.22

Medium 13.8 39.7 46.6 58 4 df

High 42.4 35.6 22.0 59 P < .01

Other specialties

Low 41.8 29.1 29.1 79 X2 = 54.00

Medium 8.5 30.8 60.7 117 4 df

High 52.0 26.7 21.3 75 P < .001

Regardless of specialty, differences in the fered on personal satisfaction and length of

basic doctor-patient relationship and the time in practice, but these were not critical

type of client routinely seen by the solo and factors, as Tables 3 and 4 indicate. Variables

private organizational physicians were rele- such as organizational size, rank in the or-

vant variables. The organizational physicians ganization, and time in the organization

probably had more control than the solo were also introduced as controls to deter-

physicians because they did not depend di- mine their effect on the degree of autonomy

rectly upon patients for their income. Since of the two organizational groups, but no sys-

the solo physicians' clients paid for each tematic differences were found.

service rendered and were not bound to a Since 62 percent of the solo physicians

single group of physicians, they were prob- had not participated in research, while 58

ably less docile and more demanding than percent of those in the privately owned or-

This content downloaded from 35.8.11.2 on Thu, 28 Nov 2013 01:20:29 AM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

18 ADMINISTRATIVE SCIENCE QUARTERLY

TABLE 3. AUTONOMY AND BUREAUCRACY BY PERSONAL SATISFACTION

Professional autonomy

Low Medium High

Bureaucracy % % % N X2-test

Less satisfying

Low 36.1 39.8 24.1 83 2= 15.56

Medium 26.3 50.0 23.7 38 4 df

High 60.9 29.7 9.4 64 p < .01

Equally satisfying

Low 39.5 34.2 26.3 38 2 = 24.62

Medium 12.9 30.7 56.4 101 4 df

High 40.7 33.3 25.9 54 p < .001

More satisfying

Low 50.0 25.0 25.0 16 2 = 16.00

Medium 10.5 32.9 56.6 76 4 df

High 25.8 38.7 35.5 31 p < .01

TABLE 4. AUTONOMY AND BUREAUCRACYBY TIME IN PRACTICE

Professional autonomy

Low Medium High

Bureaucracy % N % N X2-test

Short time

Low 47.4 28.9 23.7 38 2= 26.19

Medium 14.4 39.2 46.4 97 4 df

High 51.2 20.9 27.9 43 p < .001

Long time

Low 38.0 41.0 21.0 100 x2 = 32.81

Medium 12.5 30.0 57.5 80 4 df

High 38.4 35.6 26.0 73 p < .001

TABLE 5. CLINICAL PRACTICE AUTONOMY BY BUREAUCRACY

Professional autonomy

Low Medium High

Bureaucracy N % % N X2-test

Low 37.9 37.5 24.6 224 x2 123.06

Medium 16.2 36.5 47.2 271 4 df

High 64.9 23.8 11.3 168 p < .001

TABLE 6. CLINICAL RESEARCH AUTONOMY BY BUREAUCRACY

Professional autonomy

Low Medium High

Bureaucracy % S % N X2-test

Low 35.8 41.8 22.4 67 x2 = 7.74

Medium 41.2 30.6 28.2 85 4 df

High 29.8 29.8 40.5 84 p> .10

This content downloaded from 35.8.11.2 on Thu, 28 Nov 2013 01:20:29 AM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

Engel: PROFESSIONAL AUTONOMY 19

ganization and 32 percent of those in the explained by considering recent changes in

governmentally associated setting had not society and their effect on the professions.

participated, the autonomy scores were ex- The scientific and technological innovations

amined separately with respect to clinical which have been developed since World

practice and research, and the relationships War II have had a major impact on the

shown in Tables 5 and 6 were obtained. structure of all professions (Kast and Rosen-

With respect to clinical practice, physi- zweig, 1963:39-40; Levitt et al., 1963:16).

cians who worked within a moderately bu- Their number, size, work settings, and in-

reaucratic setting again perceived them- ternal patterns of relationships have been

selves as experiencing a greater degree of altered. New types of tools and skills have

autonomy than those in the other two set- become essential. Professionalism has be-

tings. In clinical research, however, while come, of necessity, a collective enterprise.

physicians in the nonbureaucratic setting Societal changes have also affected the

tended to maintain their moderate position, traditional bureaucratic form. Unlike the

those in the other two settings reversed their rigid structures of the past, many bureau-

positions. cracies are now adaptive, fluid systems devel-

It was not surprising that physicians in the oped for the solution of complex problems

nonbureaucratic setting were not more au- which require the services and skills of pro-

tonomous than those in the other two groups fessionals from diverse fields (Bennis,

with respect to clinical research. Physicians 1969:45).

in solo practice did not have ready access to Bureaucracies, especially professional bu-

research funds, nor did they deal with the reaucracies, can serve the needs created by

kinds of patients who were willing subjects these alterations in professional practice by

for research. However, the reversal between supplying those professionals who work

physicians in the two organizations requires within bureaucracies with funds, various

further explication. kinds of equipment, technical personnel, and

While both organizations viewed patient other physical facilities essential for con-

care as a major function, the governmentally temporary professional performance, and

associated setting stressed research in addi- with a stimulating intellectual climate for

tion to patient care, and funds were set aside interchanging information and controlling

for physicians who desired to undertake a quality of performance. These organizational

research project of merit. Also, the highly characteristics will enhance the development

bureaucratic setting was less bureaucrati- and performance of today's professional.

cally organized with respect to clinical re- Working in isolation, he is less likely to have

search than the moderately bureaucratic access to the social and physical features

setting. In the former, administrative proce- which bureaucracies can provide.

dures were often less formal, in that fewer This could explain why the professionals

rules and regulations were imposed upon in the moderate bureaucracy perceived

physicians who were pursuing research ac- themselves as having more autonomy than

tivities. those in either the nonbureaucratic or the

Further, unlike the other two settings, the highly bureaucratic setting. The nonbureau-

patient population of the governmentally cratically employed may have experienced

associated organization lent itself to re- a lack of essential physical facilities, while

search. There were no out-patients; most those who worked in the highly bureaucratic

patients were chronically ill and had to be organization might have felt limited by its

housed within the organization for long rigid administrative structure. Those in the

periods; and since their medical treatment moderate setting, on the other hand, may

was provided without charge, they were less have experienced fewer of these limitations

likely to resist being employed as research upon their professional autonomy. These

subjects. findings suggest that the professional type

Since the controlled variables did not ac- of bureaucratic organization is not neces-

count for the findings, the results may be sarily detrimental to professional autonomy.

This content downloaded from 35.8.11.2 on Thu, 28 Nov 2013 01:20:29 AM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

20 ADMINISTRATIVE SCIENCE QUARTERLY

Gloria V. Engel is an assistant professor military psychiatry." Journal of

in the department of community medicine Health and Social Behavior, 10: 255-

and public health at the University of South- 265.

ern California. Dixon, Marlene D.

1964 Professionalism in Engineering, Part

I. Working paper, University of Cali-

REFERENCES

fornia at Los Angeles.

Barnard, Chester I. Engel, Gloria V.

1938 The Functions of the Executive. Cam- 1968 The Effect of Bureaucracy on the Pro-

bridge: Harvard University Press. fessional Autonomy of the Physician.

Becker, Howard Doctoral dissertation, University of

1962 "The nature of a profession." In Nel- California at Los Angeles.

son B. Henry (ed.), Education for Flexner, Abraham

the Professions: 27-46. Chicago: Uni- 1915 "Is social work a profession?" School

versity of Chicago Press. and Society, 1:901-911.

Ben-David, Joseph Freidson, Eliot

1958 "The professional role of the physi- 1960 "Client control and medical practice."

cian in bureaucratized medicine: a American Journal of Sociology, 65:

study in role conflict." Human Rela- 374-382.

tions, 2:901-911. Glaser, Barney G.

Bendix, Reinhardt 1964 Organizational Scientists. New York:

1960 Max Weber: An Intellectual Portrait. Bobbs-Merrill.

Garden City, N.Y.: Doubleday. Goldner, Fred H., and R. R. Ritti

Bennis, Warren G. 1967 "Professionalization as career immo-

1969 "Post-bureaucratic leadership." Trans- bility." American Journal of Sociology,

action, 6:44-61. 72:489-502.

Blau, Peter M. Goode, William J.

1955 The Dynamics of Bureaucracy. Chi- 1957 "Community within a community: the

cago: University of Chicago Press. professions." American Sociological

Blau, Peter M., and W. Richard Scott Review, 22:194-208.

1962 Formal Organizations. San Francisco: 1960 "Encroachment, charlatanism, and the

Chandler. emerging profession: psychology, so-

Blauner, Robert ciology, and medicine." American So-

1964 Alienation and Freedom. Chicago: ciological Review, 25:902-914.

University of Chicago Press. Goss, Mary E. Weber

Bucher, Rue, and Joan Stelling 1959 Physicians in Bureaucracy: a Case

1967 Characteristics of Professional Orga- Study of Professional Pressures on Or-

nizations. Working paper, College of ganizational Roles. Doctoral disserta-

Medicine, University of Illinois. tion, Columbia University.

Bucher, Rue, and Anselm Strauss Hall, Oswald

1961 "Professions in process." American 1948 "The stages of a medical career."

Journal of Sociology, 66:325-334. American Journal of Sociology, 53:

Bullough, Vern L. 327-336.

1966 The Development of Medicine as a Hall, Richard

Profession. New York: Karger. 1968 "Professionalization and bureaucratiza-

Carr-Saunders, A. M., and P. A. Wilson tion." American Sociological Review,

1933 Professions. London: Oxford Univer- 33:92-104.

sity Press. Hickson, D. F.

Cogan, Morris L. 1966 "A convergence in organizational

1953 "Toward a definition of a profession." theory." Administrative Science Quar-

Harvard Educational Review, 23:33- terly, 11:224-237.

50. Hughes, Everett C.

Dalton, Melville 1958 Men and Their Work. Glencoe, Ill.:

1961 Men Who Manage. New York: Wiley. Free Press.

Daniels, Arlene K. janowitz, Morris

1969 "The captive professional: bureau- 1960 The Professional Soldier. Glencoe, Ill.:

cratic limitations in the practice of Free Press.

This content downloaded from 35.8.11.2 on Thu, 28 Nov 2013 01:20:29 AM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

Engel: PROFESSIONAL AUTONOMY 21

Kast, Fremont E., and James E. Rosenzweig Mayo, E., and G. F. Lombard

1963 "Management and acclerating tech- 1944 Teamwork and Labor Turnover in the

nology." California Management Re- Aircraft Industry of Southern Cali-

view, 6:39-48. fornia. Boston: Graduate School of

Kornhauser, William Business Administration, Harvard Uni-

1962 Scientists in Industry. Berkeley and versity.

Los Angeles: University of California Merton, Robert K.

Press. 1957 Social Theory and Social Structure.

Levitt, Theodore, Ray R. Eppert, Willis M. Glencoe, Ill.: Free Press.

Hawkins, Franklin A. Lindsay, and Mills, C. Wright

John T. Ryan, Jr. 1951 White Collar. New York: Oxford Uni-

1963 "When science supplants technology." versity Press.

Harvard Business Review, 41:14-24, Parsons, Talcott

28, and 182-190. 1954 "The professions and social structure."

In Talcott Parsons (ed.), Essays in

Lewis, Roy, and Angus Maude

Sociological Theory: 34-49. Glencoe,

1953 Professional People in England. Cam- Ill.: Free Press.

bridge: Harvard University Press. Roethlisberger,F. J., and W. J. Dickson

Lieberman, Myron 1939 Management and the Worker. Cam-

1956 Education as a Profession. Englewood bridge: Harvard University Press.

Cliffs, N.J.: Prentice-Hall. Whyte, William H., Jr.

Marshall, T. H. 1957 The Organization Man. Garden City,

1939 "The recent history of professionalism N.Y.: Doubleday.

in relation to social structure and so- Wilensky, Harold

cial policy." Canadian Journal of Eco- 1964 "The professionalization of everyone?"

nomics and Political Science, 5:325- American Journal of Sociology, 70:

340. 137-150.

This content downloaded from 35.8.11.2 on Thu, 28 Nov 2013 01:20:29 AM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

You might also like

- Constructive and Destructive Deviance in OrganizationsDocument12 pagesConstructive and Destructive Deviance in OrganizationsSenthamizh SankarNo ratings yet

- New Institutionalism - PowellDocument11 pagesNew Institutionalism - PowellAbdelkader Abdelali100% (1)

- Therm Coal Out LookDocument27 pagesTherm Coal Out LookMai Kim Ngan100% (1)

- Professional EthicsDocument32 pagesProfessional EthicsAleksandra MarkovicNo ratings yet

- Hodgson 2006Document26 pagesHodgson 2006Yanuar Akbar WardoyoNo ratings yet

- Formal Organization, Dimensions of AnalysisDocument13 pagesFormal Organization, Dimensions of AnalysisFernando PouyNo ratings yet

- 10 - March J. G., 1958, OrganizationsDocument4 pages10 - March J. G., 1958, OrganizationsLe Thi Mai ChiNo ratings yet

- Professions in A Globalizing World: Towards A Transnational Sociology of The Professions?Document41 pagesProfessions in A Globalizing World: Towards A Transnational Sociology of The Professions?charles_j_gomezNo ratings yet

- OBM-Toward A General Theory of Hierarchy - Books, Bureaucrats, Basketball Tournaments, and The Administrative Structure of The Nation-StateDocument27 pagesOBM-Toward A General Theory of Hierarchy - Books, Bureaucrats, Basketball Tournaments, and The Administrative Structure of The Nation-StateYifeng KuoNo ratings yet

- J Organ Behavior - 2003 - Kreiner - Evidence Toward An Expanded Model of Organizational IdentificationDocument27 pagesJ Organ Behavior - 2003 - Kreiner - Evidence Toward An Expanded Model of Organizational IdentificationMelita Balas RantNo ratings yet

- Agents and StructuresDocument26 pagesAgents and StructuresYaggo AgraNo ratings yet

- Typology of Voluntary AssociationsDocument9 pagesTypology of Voluntary AssociationsFoteini PanaNo ratings yet

- 1962 Sources of Power of Lower Participants in Complex OrganizationsDocument19 pages1962 Sources of Power of Lower Participants in Complex OrganizationsmaxNo ratings yet

- Critically Analyze The Statement That Is An Ideal Solution To The Problems ofDocument8 pagesCritically Analyze The Statement That Is An Ideal Solution To The Problems ofAhmed JamallNo ratings yet

- Goldiamon - Toward A Constructional Approach To Social Problems Ethical and Constitutional Issues Raised by Applied Behavior Analysis PDFDocument90 pagesGoldiamon - Toward A Constructional Approach To Social Problems Ethical and Constitutional Issues Raised by Applied Behavior Analysis PDFPamelaLiraNo ratings yet

- Human Relations 2010 Brown 525 49Document26 pagesHuman Relations 2010 Brown 525 49Leonardo TononNo ratings yet

- J Organ Behavior - 2022 - Sun - Workplace Gossip An Integrative Review of Its Antecedents Functions and ConsequencesDocument24 pagesJ Organ Behavior - 2022 - Sun - Workplace Gossip An Integrative Review of Its Antecedents Functions and ConsequencesDavid RodríguezNo ratings yet

- Impact 2.0 - The Production of Subjectivity, Expertise, and The Responsibility in A Necrogeographical WorldDocument5 pagesImpact 2.0 - The Production of Subjectivity, Expertise, and The Responsibility in A Necrogeographical WorldJay GasonNo ratings yet

- Mor 2014Document29 pagesMor 2014MUHAMMAD ARIIQ AL FAYYADH IPBNo ratings yet

- The Rise of Professionalism: August 2017Document19 pagesThe Rise of Professionalism: August 2017Pedro CavalcantiNo ratings yet

- The Importance of StakeholdersDocument9 pagesThe Importance of StakeholdersmimiNo ratings yet

- La Herencia AfricanaDocument26 pagesLa Herencia AfricanaAngel Delgado CastroNo ratings yet

- Mechanic SourcesPowerLower 1962Document17 pagesMechanic SourcesPowerLower 1962jojokawayNo ratings yet

- The American Journal of SociologyDocument22 pagesThe American Journal of SociologyShree DeshpandeNo ratings yet

- Garston. The Study of BureaucracyDocument22 pagesGarston. The Study of BureaucracyRamdanNo ratings yet

- Sources of Power of Lower Participants in Complex OrganizationsDocument17 pagesSources of Power of Lower Participants in Complex OrganizationsFrancisco MedinaNo ratings yet

- Sage Publications, Inc. Johnson Graduate School of Management, Cornell UniversityDocument21 pagesSage Publications, Inc. Johnson Graduate School of Management, Cornell UniversitysabaNo ratings yet

- Winnie Yun Jiang Perceiving Fixed or Flexible MeaningDocument48 pagesWinnie Yun Jiang Perceiving Fixed or Flexible MeaningAnanth BalakrishnanNo ratings yet

- FriedkinDocument28 pagesFriedkinEmmaTeglingNo ratings yet

- Beauty Is in The Eye of The Beholder - The Impact of Organizational Identification, Identity, and Image On The Cooperative Behaviors of PhysiciansDocument28 pagesBeauty Is in The Eye of The Beholder - The Impact of Organizational Identification, Identity, and Image On The Cooperative Behaviors of PhysiciansAlper BilgilNo ratings yet

- Wiley Midwest Sociological SocietyDocument5 pagesWiley Midwest Sociological SocietyGonzalo MoyanoNo ratings yet

- Modern Structural OrganizationsDocument20 pagesModern Structural OrganizationsAngelo PanilaganNo ratings yet

- Organi Zationa L Behavi OURDocument4 pagesOrgani Zationa L Behavi OURhaseeb ahmedNo ratings yet

- Do Public and Private Sector Employees Act DifferentlyDocument31 pagesDo Public and Private Sector Employees Act DifferentlyJill De Dumo-CornistaNo ratings yet

- Duncan 1972Document16 pagesDuncan 1972Qamber AbbasNo ratings yet

- Social PsychologyDocument22 pagesSocial PsychologyHIMANSHU VAIDYANo ratings yet

- PersonalityDocument28 pagesPersonalityRaymond Krishnil KumarNo ratings yet

- Ruef M. (1999) - Social Ontology and the Dynamics of Organizational Forms- Creating Market Actors in the Healthcare Field, 1966–1994Document30 pagesRuef M. (1999) - Social Ontology and the Dynamics of Organizational Forms- Creating Market Actors in the Healthcare Field, 1966–1994Claudyvanne SilvaNo ratings yet

- Peter BlauDocument14 pagesPeter BlauChristian MárquezNo ratings yet

- New Directions For Organization Theory: Problems and ProspectsDocument41 pagesNew Directions For Organization Theory: Problems and ProspectsErick Karim Esparza DominguezNo ratings yet

- This Content Downloaded From 203.124.40.244 On Mon, 18 Oct 2021 04:42:22 UTCDocument11 pagesThis Content Downloaded From 203.124.40.244 On Mon, 18 Oct 2021 04:42:22 UTCSami Ul HaqNo ratings yet

- Goldiamond - Toward A Constructional Approach To Social ProblemsDocument85 pagesGoldiamond - Toward A Constructional Approach To Social ProblemsAngela RNo ratings yet

- Institutions and Social Structures 15Document29 pagesInstitutions and Social Structures 1521augustNo ratings yet

- Teachers of Color Literature ReviewDocument19 pagesTeachers of Color Literature ReviewDavid BrownNo ratings yet

- A Theory of Role StrainDocument15 pagesA Theory of Role StrainFernando PouyNo ratings yet

- Lavena Manuscript 1307 - 607Document45 pagesLavena Manuscript 1307 - 607Yustina Lita SariNo ratings yet

- Consequences of Power Distance Orientation in Organisations: Vision-The Journal of Business Perspective January 2009Document11 pagesConsequences of Power Distance Orientation in Organisations: Vision-The Journal of Business Perspective January 2009athiraNo ratings yet

- HumanRelations 2013Document26 pagesHumanRelations 2013tabrez khanNo ratings yet

- Livne-Ofer Et Al. - (2019 - AMJ) - Perceived Exploitative and Its ConsequecesDocument30 pagesLivne-Ofer Et Al. - (2019 - AMJ) - Perceived Exploitative and Its Consequeces李佩真No ratings yet

- Galea Breaking The Barriers of Insider Research in Occupational Health and SafetyDocument10 pagesGalea Breaking The Barriers of Insider Research in Occupational Health and SafetyAndrew BarbourNo ratings yet

- Kakabadse, A. (1986) - Organizational Alienation and Job Climate. Small Group Behavior, 17 (4), 458-471.Document15 pagesKakabadse, A. (1986) - Organizational Alienation and Job Climate. Small Group Behavior, 17 (4), 458-471.jj49No ratings yet

- Hall 1968Document14 pagesHall 1968Shree DeshpandeNo ratings yet

- How Differentiation and Integration Impact Organizational PerformanceDocument49 pagesHow Differentiation and Integration Impact Organizational PerformanceEllaNatividadNo ratings yet

- Governmentality, Power and Organization: Management & Organizational History February 2012Document15 pagesGovernmentality, Power and Organization: Management & Organizational History February 2012JoãoNo ratings yet

- Geert Hofstede Bram Neuijen Denise Daval Ohayv Geert SandersDocument34 pagesGeert Hofstede Bram Neuijen Denise Daval Ohayv Geert SandersRoxana FasieNo ratings yet

- Cultivating Institutional Ecology: Comment on Hannan, Carroll, Dundon, and TorresDocument11 pagesCultivating Institutional Ecology: Comment on Hannan, Carroll, Dundon, and TorresGloria Donato LopezNo ratings yet

- Wiley The International Studies Association: Info/about/policies/terms - JSPDocument23 pagesWiley The International Studies Association: Info/about/policies/terms - JSPJuan David ChamuseroNo ratings yet

- This Content Downloaded From 189.125.96.10 On Sat, 15 May 2021 14:13:41 UTCDocument16 pagesThis Content Downloaded From 189.125.96.10 On Sat, 15 May 2021 14:13:41 UTCJose Fernandes SantosNo ratings yet

- Bureaucracy: Is It Efficient? Is It Not? Is That The Question? Uncertainty Reduction: An Ignored Element of Bureaucratic RationalityDocument24 pagesBureaucracy: Is It Efficient? Is It Not? Is That The Question? Uncertainty Reduction: An Ignored Element of Bureaucratic RationalityJay-son LuisNo ratings yet

- Encyclopedia of Social Science Research MethodsDocument580 pagesEncyclopedia of Social Science Research Methodsmedeea32100% (3)

- Becoming Bureaucrats: Socialization at the Front Lines of Government ServiceFrom EverandBecoming Bureaucrats: Socialization at the Front Lines of Government ServiceNo ratings yet

- Reset Form for Voter RegistrationDocument6 pagesReset Form for Voter RegistrationapolloNo ratings yet

- Farh & Cheng (2000)Document44 pagesFarh & Cheng (2000)Marielle LituanasNo ratings yet

- Graen 1995 - Relationship-Based Approach To Leadership PDFDocument30 pagesGraen 1995 - Relationship-Based Approach To Leadership PDFMarcela Côrtes100% (1)

- COR and Dissaster in Cultural Context - The Caravans and Passageways For Resources (Hobfoll, 2012)Document7 pagesCOR and Dissaster in Cultural Context - The Caravans and Passageways For Resources (Hobfoll, 2012)Marielle LituanasNo ratings yet

- Shung & Zhou (2003)Document13 pagesShung & Zhou (2003)Marielle LituanasNo ratings yet

- Wang & Cheng (2010)Document16 pagesWang & Cheng (2010)Marielle LituanasNo ratings yet

- Preacher & Hayes (2007)Document44 pagesPreacher & Hayes (2007)Marielle LituanasNo ratings yet

- Measuring interpersonal trustDocument16 pagesMeasuring interpersonal trustMarielle LituanasNo ratings yet

- Yuan & Woodman (2010)Document21 pagesYuan & Woodman (2010)Marielle LituanasNo ratings yet

- Montoya & Hayes (2016) - Research DesignDocument23 pagesMontoya & Hayes (2016) - Research DesignMarielle LituanasNo ratings yet

- Case Analysis WhelanDocument5 pagesCase Analysis WhelanRakesh SahooNo ratings yet

- Nozzles - Process Design, From The OutsideDocument12 pagesNozzles - Process Design, From The OutsideperoooNo ratings yet

- 0076 0265 - Thy Baby Food LicenceDocument2 pages0076 0265 - Thy Baby Food LicenceSreedharanPNNo ratings yet

- Article 20 Salary Scales 10-Month Teachers 2019-2020 (Effective July 1, 2019)Document10 pagesArticle 20 Salary Scales 10-Month Teachers 2019-2020 (Effective July 1, 2019)Robert MaglocciNo ratings yet

- Cover Letter EdtDocument2 pagesCover Letter Edtapi-279882071No ratings yet

- Gauge BlockDocument32 pagesGauge Blocksava88100% (1)

- 2 Quarter Examination in Tle 8 (Electrical Installation and Maintenance)Document3 pages2 Quarter Examination in Tle 8 (Electrical Installation and Maintenance)jameswisdom javier100% (4)

- Design and Analysis of 4-2 Compressor For Arithmetic ApplicationDocument4 pagesDesign and Analysis of 4-2 Compressor For Arithmetic ApplicationGaurav PatilNo ratings yet

- Quick Start Guide: Before You BeginDocument13 pagesQuick Start Guide: Before You Beginfrinsa noroesteNo ratings yet

- People of the Philippines vs Leonida Meris y Padilla Joint Decision Convicts Illegal Recruitment EstafaDocument8 pagesPeople of the Philippines vs Leonida Meris y Padilla Joint Decision Convicts Illegal Recruitment Estafarodel_odzNo ratings yet

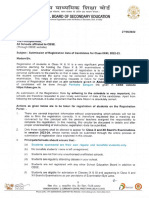

- Submission Registration IX XI For 2022 23 27062022Document23 pagesSubmission Registration IX XI For 2022 23 27062022Karma Not OfficialNo ratings yet

- Police Personnel Management and RecordsDocument26 pagesPolice Personnel Management and RecordsLowie Jay Mier OrilloNo ratings yet

- Isolating Antagonistic BacteriaDocument12 pagesIsolating Antagonistic BacteriaDesy rianitaNo ratings yet

- 4x7.1x8.5 Box CulvertDocument1,133 pages4x7.1x8.5 Box CulvertRudra SharmaNo ratings yet

- Refregeration & Airconditioning 2011-2012Document29 pagesRefregeration & Airconditioning 2011-2012erastus shipaNo ratings yet

- Victorian England in RetrospectDocument174 pagesVictorian England in RetrospectNehuén D'AdamNo ratings yet

- Application of Power Electronic Converters in Electric Vehicles andDocument22 pagesApplication of Power Electronic Converters in Electric Vehicles andfekadu gebeyNo ratings yet

- Improve Asset Performance with Integrated Asset ManagementDocument12 pagesImprove Asset Performance with Integrated Asset ManagementArun KarthikeyanNo ratings yet

- 5-Cyanophthalide ProjDocument7 pages5-Cyanophthalide ProjdrkrishnasarmapathyNo ratings yet

- A Simple Digital Power-Factor CorrectionDocument11 pagesA Simple Digital Power-Factor CorrectionVinoth KumarNo ratings yet

- Nestle Announcement It Is Pulling The Plug On Eldred TownshipDocument2 pagesNestle Announcement It Is Pulling The Plug On Eldred TownshipDickNo ratings yet

- WAPU Kufqr PDFDocument2 pagesWAPU Kufqr PDFAri TanjungNo ratings yet

- MXTX1012 GX PA00Document28 pagesMXTX1012 GX PA00200880956No ratings yet

- GLE 53 4M+ Coupe PMDocument2 pagesGLE 53 4M+ Coupe PMCalvin OhNo ratings yet

- MOA - NDMS Enterprise Inc.Document3 pagesMOA - NDMS Enterprise Inc.merlitamartinez8No ratings yet

- HUT-A Hydraulic Universal Testing Machine 2018.6.26 PDFDocument6 pagesHUT-A Hydraulic Universal Testing Machine 2018.6.26 PDFSoup PongsakornNo ratings yet

- Fundamentals of Cyber Law 2021 t6hzxpREDocument97 pagesFundamentals of Cyber Law 2021 t6hzxpREshivraj satavNo ratings yet

- Lecture 4Document10 pagesLecture 4unknownuser14.1947No ratings yet

- Decoled FR Sas: Account MovementsDocument1 pageDecoled FR Sas: Account Movementsnatali vasylNo ratings yet