Professional Documents

Culture Documents

FPA Journal-August 2009-The 1

Uploaded by

Rajesh RishiCopyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

FPA Journal-August 2009-The 1

Uploaded by

Rajesh RishiCopyright:

Available Formats

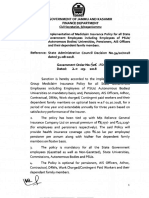

Contributions DUBOFSKY | SUSSMAN

The Changing Role of the Financial

Planner Part 1: From Financial Analytics

to Coaching and Life Planning

by David Dubofsky, Ph.D., CFA, and Lyle Sussman, Ph.D.

David Dubofsky, Ph.D., CFA, is professor of finance and

associate dean for research, University of Louisville. He Executive Summary

has published more than 25 academic journal articles and

• This report is the first in a two-part completed some portion of the survey.

is the author of two textbooks.

study of the emerging role of coaching • Approximately 25 percent of the

in financial planning.This first paper respondents’ contact with clients is

Lyle Sussman, Ph.D., is professor and chairman of the

reports the results of our survey, which devoted to non-financial issues. About

department of management and entrepreneurship,

support the thesis that financial 74 percent of planners estimate that

University of Louisville. He has written 65 scholarly articles

acumen is necessary for financial plan- the amount of time they are spending

and 9 management books translated into 17 languages that

ning, but not sufficient. Implications for on these issues has increased over the

have sold a total of 1 million copies worldwide.

training and professional development last five years.

are extensively discussed in Part 2. • Most respondents believe that their

• An online survey was sent to 38,810 non-financial coaching and counseling

O

ur research into the emerging

role of the financial planner as members of the Financial Planning makes them better planners and helps

life coach is presented in two Association and CFP Board mailing list their clients, but are less certain that

separate reports. This first report focuses participants, to determine the non- these activities increase business.

on the descriptive results of a large scale financial coaching and life planning • Planners help clients with critical issues

Web-based survey, and provides empirical activities of financial planners. that reflect human drama and frailties:

data clarifying the scope, trends, and • The primary research question for this religion and spirituality, death, family dys-

coaching-related practices of financial study concerns the changing role of the function, illness, divorce, and depression.

planners. The second report, which will be financial planner and the major implica- • Most respondents have at least some

published in the September issue of the tions of that change for the financial training to equip them to help clients

Journal (Sussman and Dubofsky, 2009), is planner of today and tomorrow. with non-financial issues, but 40 per-

an extension of the descriptive summary • A total of 1,374 planners completed cent have had no training or profes-

and focuses on the implications of our the entire survey, though 2,006 sional development in this area.

empirical results for financial planners.

This first report thus sets the stage for the

second report. As a set, the reports answer the following overarching question: How is It reveals a 2,000+ word description of the

the role of the financial planner changing nature of the work, training, and qualifica-

and what are the major implications of that tions for this occupation. The results of

change for the financial planner of today the survey we conducted suggest that the

Acknowledgement: We could not have conducted this and tomorrow? Department of Labor’s description

survey without the assistance of Rebecca King of the Finan- A description of the profession known accounts for only 75 percent of the actual

cial Planning Association and Asha Williams of Certified as “personal financial adviser,” can be work financial advisers perform for their

Financial Planner Board of Standards. Rachel Candelora found by visiting the U.S. Department of clients. The other 25 percent of the work

provided valuable research assistance. We also thank the Labor Occupational Outlook Handbook involves dealing with non-financial

participants in our focus group. Web page (www.bls.gov/oco/ocos259.htm). issues—human drama and frailties.

48 Journal of Financial Planning | AUGUST 2009 www.FPAjournal.org

DUBOFSKY | SUSSMAN Contributions

In dealing with these personal, non- plans. Retiring baby boomers are thus dis- Research Questions

financial issues, financial planners forge covering that managing a retirement

bonds with their clients that we may charac- account is difficult at best and gut Because the study is exploratory in

terize as special and endearing. There are wrenching at worst. nature we pose research questions rather

precious few interpersonal bonds worthy of than test theoretically grounded

this label. Examples include parent and Purpose hypotheses. Specifically, this study was

child, minister and parishioner, teacher and designed to empirically answer the

student, physician and patient. We posit Given the potential of the planner-client research question posed above: How is

that the relationship between financial plan- engagement to be executed on an emotional the role of the financial planner chang-

ner and client is also worthy of the label. minefield (Kahn, 2001), it is not surprising ing, and what are the major implications

Discussing personal financial assets, that a body of literature focusing on the of that change for the financial planner

personal life goals, and articulating plans planner as coach and counselor has of today and tomorrow?

for achieving those goals relies on trust, emerged. This literature speaks to the need This major question suggested five corol-

candor, and a client’s willingness to be and importance of the non-financial coach- lary questions:

open and potentially vulnerable. These ing and counseling role of financial planners RQ1: Planners’ Perceptions of the

characteristics are the essence of special (Kahler, 2005; Warner, 2006; Wagner, 2000; Coaching Role. To what extent do finan-

and endearing relationships. “People who O’Neill, 1991; Matson, 2003), and the skills cial planners perceive their role as encom-

would not dream of seeking out a thera- required of this new role (Christiansen and passing coaching and counseling? Do plan-

pist, counselor, or clergyman for emo- DeVaney, 1998; Collier, 2004; Miller and ners see this role as increasing or

tional support may find themselves emo- Koesten, 2008). Two dominant themes decreasing in importance?

tionally overcome or vulnerable when emerge from this literature. First, financial RQ2: The Issues. What are the most

talking with a planner about a pending acumen is necessary for financial planning common personal, non-financial issues

divorce, planning for death, or in the but may not be sufficient. “The most effective financial planners confront in their

aftermath of losing a loved one, caring financial planning will combine the cogni- engagements with clients?

for a special needs family member, or tive talents of the traditional financial plan- RQ3: Perceived Value of the Coaching

leaving a legacy” (Kinder and Galvan, ner with the emotional skills of a counselor” Role. Do planners perceive the coaching

2006, p. 197). Thus, financial planners, (Kahler, 2005, p.62). Secondly, financial role as important for them, their clients,

whether they planned for it or not, may planners must seek out professional develop- and their business?

become personal coaches and counselors ment opportunities to increase their coach- RQ4: Coaching and Counseling Critical

for their clients. ing and life planning skills. Incidents and Behaviors. What are the crit-

Moreover, given the demographic The literature supporting these two ical incidents reflecting the non-financial

trends of retiring baby boomers, the themes, however, is primarily anecdotal coaching/counseling role of financial

wealth they are likely to inherit from par- and prescriptive. Thus, we have case stud- planners? What behaviors do financial

ents or distribute to children, and deci- ies highlighting the

sions regarding Social Security benefits emergence and impor-

Financial planners, whether they

(Congressional Budget Office, 2003), tance of this new finan-

financial planners are in a growth indus-

try. The Department of Labor forecasts

that it will be the sixth-fastest growing

cial planning role, per-

sonal accounts of specific

issues raised in life plan- “ planned for it or not, may become

personal coaches and counselors for

their clients.

occupation between 2006 and 2016, with ning sessions (for exam-

”

the number of personal financial advisers ple, succession planning,

rising from 176,000 to 248,000 during blended families, clients

this period (see www.bls.gov/oco/ocos and/or family members

259.htm#projections_data and with Alzheimer’s), and

www.bls.gov/oco/oco2003.htm). The advice on how planners

demand for qualified financial planning should execute that role. But this literature planners engage in as part of their coach-

also reflects the American worker’s fails to provide an empirically based, com- ing and counseling?

increased exposure to financial uncer- prehensive view of the underlying dynam- RQ5: Training and Preparation. Of

tainty, a result of the corporate world’s ics and scope of the role. The purpose of what type and how extensive is the train-

transition from offering defined benefit this study is to provide that view and fill ing financial planners have received in life

pension plans to defined contribution that void. planning and coaching?

www.FPAjournal.org AUGUST 2009 | Journal of Financial Planning 49

Contributions DUBOFSKY | SUSSMAN

Table

Table 1: Respondent, CFP C

Respondent, Certificant,

ertificant, and FPA

FPA Membership

Membership tions. The e-mail directed recipients to an

Demographics

Demographics online survey.

A total of 2,006 financial planners

This

This Study

Study CFP C

Certificants

ertificants FPA

FPAMMembership

embership logged on to the survey, representing a 5.2

Gender

Gender percent response rate. The introduction to

Male

Male 79.6% 76.5% 75.0% the survey explicitly assured anonymity

Female

Female 20.4% 23.3% 25.0% and confidentiality and provided the fol-

Age

Age lowing rationale:

< 30 3.2% 3.0% 2.0%

31–40 17.9% 20.4% 12.0% We have partnered with Certified

41–50 27.3% 28.0% 26.0% Financial Planner Board of Standards

51–60 35.3% 30.2% 35.0% and the Financial Planning Associa-

> 60 16.4% 17.3% 25.0% tion to conduct a survey of your per-

Education

Education ceptions of the changing role of finan-

High school

school 0.8% cial planners. This questionnaire

Some

Some college

college 8.6% probes the nature and frequency of

College

College degree

degree 43.7% 60.3%* 70%*** personal, non-financial problems and

Advanced

Advanced degree

degree 46.9% 34.7%** 33%*** issues raised during planning sessions.

Professional

Professional Designations

Designations Both anecdotal data and published

CFP 97.6% 100%1 67.0% reports highlight the importance of

RIA 41.7% --- 64.6%2 the coaching and counseling aspects

ChFC

ChFC 15.6% 10.8% 9.7% within a financial planning engage-

CLU

CLU 13.3% 10.1% 9.2% ment. We define coaching and coun-

CPA

CPA 6.9% 12.9% 11.0% seling as using your non-financial

PFS 3.1% 3.0% 3.7% skills, ability, and knowledge to help

J.D..

J.D 2.3% 4.2% 2.9% your clients achieve personal fulfill-

CF

CFAA 1.5% 2.4% 2.1% ment and their life goals.

Assets

Assets Under Management3

Under Management

< $20 million 25.0% Of the 2,006 surveys started, 1,374 were

< $25 million 38.0% completed, representing a 68.5 percent

$20–50 million 28.0% completion rate. Because the survey

$25–50 million 18.0% probed highly sensitive information, we

$51–100 million 22.0% 13.0% correctly anticipated that some respon-

$101–250 million 17.0% 9.0% dents might skip or disregard some ques-

> $250 million 8.0% 4.0% tions. In order to obtain the highest

Don’t

Don’t manage assets 17.5% response rate possible, respondents were

*AAssociate’s

ssociate’s and bachelor’s

bachelor’s degrees

degrees Continued on page 52 urged but not required to answer every

** MMaster’s,

aster’s, Ph.D.,

Ph.D., and JJuris

uris Doctor

Doctor degr

degrees

ees question. A question could be skipped

*** FPA

FPA memb

members ers ccould

ould selec

selectt b

both;

oth; ther

therefore,

efore, the sum eexceeds

xceeds 100%.

1

100% arare

e CFP ccertificants.

ertificants. 70% arare

e CFP prpractitioners.

actitioners.

without automatically terminating the

2

Includes dually-r

dually-registered

egistered ad

advisers

visers questionnaire. We thus recorded responses

3

Information

Information from

from CFP Board

Board not available

available from complete and incomplete surveys. In

general, the number of responses declined

as respondents went deeper into the

Method and Sample wanted to opt out of e-mail communica- survey. The number of responses to any

tion. The Financial Planning Association one question ranged between 1,087 and

Our survey was e-mailed to 38,810 finan- sent the survey to an additional 16,000 1,517. For dichotomous questions, within

cial planners. CFP Board sent it to 22,810 members who accept e-mail and research- this range of responses, the sampling error

registered CERTIFIED FINANCIAL related communications. CFP Board and ranges from ±2.52 to ±2.97 at the 95 per-

PLANNER™ certificants who were self- FPA collaborated so that a respondent cent confidence level.

identified practitioners and who previ- should not have received a request to par- Table 1 provides demographic characteris-

ously never notified CFP Board that they ticipate in the survey from both organiza- tics of our respondents and compares them

50 Journal of Financial Planning | AUGUST 2009 www.FPAjournal.org

DUBOFSKY | SUSSMAN Contributions

to the population demographics of CFP cer- Almost 98 percent of our respondents addition, 17 percent of respondents

tificants and FPA members.1 Comparison are CERTIFIED FINANCIAL PLANNER manage portfolios of $101–$250 million,

data address the issue of nonresponse bias. (CFP) practitioners. Many of them hold and another 8 percent manage more than

This comparison suggests reasonable com- other professional designations or titles as $250 million.

parability of sample characteristics to popu- well, such as Registered Investment Respondents are compensated in a vari-

lation characteristics. Moreover, it is impor- Adviser (RIA, 41.7 percent), Chartered ety of ways; the two compensation meth-

tant to note that 30 percent of CFP Financial Consultant (ChFC, 15.6 per- ods most frequently mentioned were

certificants and many FPA members are not cent), and Char-

CFP practitioners, so that some demo- tered Life Under-

We have partnered with Certified

graphic differences between our respon- writer (CLU, 13.3

dents (all of whom stated that they supply

financial planning services directly to indi-

viduals and families) and the other two

percent).

Almost 88 per-

cent of our respon-

“ Financial Planner Board of Standards

and the Financial Planning Association to

conduct a survey of your perceptions of

groups are expected. dents have more

the changing role of financial planners.

Eighty percent of our respondents are than 30 clients. The

”

male, and 20 percent female. In terms of value of assets

race, 94 percent are white. The largest age under advisement

group is 51–60 (35 percent), followed by was clustered in the

41–50 (27 percent). Ninety-one percent of categories of “less

the respondents have either an undergradu- than $20 million,”

ate or graduate degree. All but 11 percent of “$20–$50 million,” and “$51–$100 mil- “percent of assets” and “commission,”

the respondents have more than five years of lion,” with 25 percent, 28 percent, and 22 cited by 69 percent and 64 percent of our

experience working as a financial planner. percent representation, respectively. In respondents, respectively.

www.FPAjournal.org AUGUST 2009 | Journal of Financial Planning 51

Contributions DUBOFSKY | SUSSMAN

was developed through two sources: (1) a

Table

Table 1 (continued):

(continued)

(continued): Respondent,

Respondent, CFP C

Certificant,

ertificant, and FPA

FPA Membership

Membership summary of the anecdotal literature dis-

Demographics

Demographics cussed earlier, and (2) a summary of a

Compensation M

Compensation ethods

Methods T

This

his S

Study

tudy FPA

FPAMMembership

embership focus group conducted with six financial

Percent

Percent of assets 68.7% 66.2% planners, convened to help design the

C ommission

Commission 63.9% 63% questionnaire.

Fixed fee

Fixed fee 31.1% 24.8% We probed these 17 issues in two ways:

H ourly

Hourly 27.5% 17.5% assessing the percentage of clients who

Annual retainer

Annual or retainer 21.5% 14.7% raised each issue, and assessing which

SSalary

alary 14.2% 9% three issues took up most of the planners’

O ther

Other 3.2% 0% time. Figure 1 summarizes the answers to

N umber of C

Number lients

Clients This

T Study

his Study the first question. Depending upon the

1–10 3.8% specific issue, the number of responses

11–20 3.9% ranges from 1,266 to 1,307. Figure 1 shows

21–30 4.8% that, given that a financial planner has

> 30 87.6% engaged in non-financial coaching and

counseling, personal life goals were dis-

Number

Number of Y

Years

ears A

Ass a F

Financial

inancial P

Planner

lanner

cussed with 64 percent of the planner’s

This

T Study

his Study FPA

FPAMMembership

embership

clients on average. Other prominent issues

<— 5 10.6% 0–4 27% deal with a client’s physical health (52 per-

6–10 24.8% 5–9 9% cent of clients) and a client’s job, career, or

11–20 32.8% 10–14 13% profession (50 percent of clients). All other

> 20 31.8% > 15 49% issues involve less than 50 percent of a

Note:

Note: Inf

Information

ormation fr

from

om CFP B

Board

oard not aavailable.

vailable. financial planner’s clients.

When asked which three non-financial

Results planning (monetary) issues, and that 25 issues take up the most time, 81 percent of

percent of their time is spent on non- the respondents cited a client’s personal

Perceptions of the Non-financial Coach- financial issues.2 life goals; 66 percent cited a client’s job,

ing Role. Because some financial plan- We asked our respondents whether they career, or profession; and 44 percent

ners do not have direct contact with are engaged in non-financial coaching included a client’s physical health, thus val-

clients and because some planners may activities because their clients demanded idating responses to the first question. The

view their role as “purely” financial plan- these services or because they supply these fourth most frequently stated issue, death

ning, we posed an introductory question services as part of their business strategy. of someone close, was selected by 19 per-

designed to clearly dichotomize the Sixty-six percent respond to their clients’ cent of the financial planners as one of the

sample into those who coach and counsel requests, while 34 percent supply these three most time-consuming issues.

and those who do not: “In your role as a services as part of their business strategy. Only two issues received distinctly dif-

financial planner, do you ever engage in The Issues. At the end of our survey, ferent rankings in terms of the percentage

non-financial coaching and counseling?” respondents had the opportunity to pro- of clients who raise the issue versus the

Of the 1,726 planners who answered the vide any other information they thought time spent dealing with the issue. The

question, 1,540 (89 percent) answered yes was relevant to our study. One comment first is a client’s legal problems, other

and 186 (11 percent) answered no. All stood out: “… when someone trusts you than those dealing with estate, tax, and/or

subsequent results that we report come enough to open up about finances, usually divorce. While it ranked eleventh in terms

from those who answered yes. they will open up about other more per- of the number of clients who raise these

Of those who answered yes, 74 percent sonal issues.” The following results expli- issues to their financial planners (21.3

believe that during the past five years, they cate this sentiment. percent of clients), it ranked fifth in

have increased their coaching and counsel- We asked our respondents whether they terms of the number of financial planners

ing involvement with their clients; and 26 had dealt with 17 personal and sensitive who said it was among the top three most

percent believe that the frequency of deal- issues their clients might experience, time-consuming issues (17 percent of

ing with non-financial issues has decreased. issues concerning a client’s work, family, financial planners). The second issue is a

Respondents estimate that 75 percent of and a wide range of emotional, physical, client’s marital problems. When consider-

their time is spent dealing with financial and mental problems. The list of 17 issues ing the number of clients who raise this

52 Journal of Financial Planning | AUGUST 2009 www.FPAjournal.org

DUBOFSKY | SUSSMAN Contributions

issue to financial planners, it ranked sixth

(23 percent of clients). But in terms of Figure 1: Non-financial Issues that Clients Raise with Financial Planners

time spent, it ranked thirteenth (only 4

Average Percentage of Clients

percent of all financial planners said that

Who Raise the Issue

the issue was in their top three most

0 10 20 30 40 50 60 70

time-consuming issues).

Even beyond the most prominently cited Personal life goals

issues, we were struck by the numbers of Physical health

respondents who have dealt with the issues

Job/career/profession

at the bottom of Figure 1. The fact that

10–20 percent of clients talk about addic- The death of someone very close to the client

tions, divorce, mental health, depression, Conflict with children

and spirituality underscores the reality that

Marital problem

financial planners provide their services on

an emotional minefield. Children’s medical/emotional problems

Perceived Value of Coaching. Our Divorce (pending or final)

respondents generally believe that their Conflicts with extended family members (other than

non-financial coaching and counseling spouse and/or children)

helps their clients, lets them be better Spending addiction

financial planners, and, perhaps to a lesser Legal problems (excluding estate, tax,

and/or divorce issues)

extent, helps their businesses. Table 2 (on

Religious/spiritual issues

page 54) presents the responses to a set of

four questions that deal with the possible Mental health

benefits of non-financial coaching. Depression/general unhappiness

The first two questions address client Children’s addictions (drugs, gambling, eating,

outcomes. Less than 3 percent of financial spending, sex, etc.)

planners disagreed or strongly disagreed Client’s addictions, other than spending

(substance abuse, gambling, sex)

with statements that their clients’ families Sexual problems

communicated better with each other and

that their clients seem to be living and

enjoying a life closer to their core values.

In contrast, almost 60 percent of financial they are less certain that it has a positive planner into the event, and was followed by

planners agreed or strongly agreed with effect on the bottom line. a description of the incident.

those statements. Critical Incidents and Planners’ Behav- We assessed the critical incidents by

The last two questions in the set iors. This research question has two parts. posing a dichotomous question, asking

solicited perceptions of personal perform- The first posed several critical incidents simply whether the planner had or had not

ance and business potential. Almost 90 financial planners might experience in serv- experienced the incident. Table 3 (on page

percent of respondents agreed or strongly icing a client’s needs. A critical incident pro- 55) ranks the incidents by the percentage

agreed that their ability to be a good finan- totypically reflects significant events and of yes answers. Seventy-four percent of the

cial planner is enhanced or improved processes, from the respondents’ perspec- planners have experienced a session in

because they discuss non-financial issues tive. The second part presented a series of which a client became emotionally dis-

with their clients. Perhaps surprising, how- specific coaching and counseling behaviors traught. The emotional bond between

ever, are the respondents’ answers to the financial planners may engage in when deal- planner and client is illustrated by the

fourth question. Almost 13 percent do not ing with a client’s personal problems. second most prevalent incident: 58 percent

believe that their business has increased The critical incidents, drawn from the lit- of our respondents have been told a secret

because of their non-financial counseling, erature discussed earlier and from our focus by a client, dealing with a non-financial

while 39 percent believe business has group of financial planners, reflected signifi- issue, that no other person knows.

increased because of their non-financial cant examples of coaching and counseling Religion and spirituality have been the

counseling. Thus, while financial planners events, processes, and actions planners are focus of considerable discussion in the

strongly believe they are doing a better job likely to experience. The incidents included financial planning world. Our data confirm

because of their non-financial coaching, the pronoun “you,” putting the financial their importance: 49 percent of respondents

www.FPAjournal.org AUGUST 2009 | Journal of Financial Planning 53

Contributions DUBOFSKY | SUSSMAN

Other stakeholders recognize this intense

Table

Table 2: Has N

Has Non-financial

on-financial C

Coaching

oaching Been

Been of Value

Value for

for Clients

Clients and/or

bond. Thirty-three percent of our respon-

Planners?

Planners?

dents have been lobbied by an organiza-

Strongly

Strongly DDisagree

isagree N

Neutral

eutral A

Agree

gree S

Strongly

trongly Total

Total tion for philanthropic donations, and 26

Disagree

D isagree Agree

Agree Responses

Responses percent were lobbied to include an organ-

Because of m

Because myy discussion ization in a client’s will. Thirty-two per-

of sensitive,

sensitive, p personal

ersonal non- cent have been lobbied by a member of a

financial issues with my my client’s family to get special considera-

clients

clients ther

there e is mor

more e 9 24 418 562 110 1,123 tion. These critical incidents expose the

effective

effec

eff ective communication

communication (1%) (2%) (37%) (50%) (10%) financial planner to complex ethical

between

bet

etwween husband and wife wife,

wif e, issues and dilemmas, and to the risk that

parents children,

parents and childr en, he or she might reveal confidential infor-

or others who may may b be e mation about the client.

significant

significant in my

my clien

clients’

ts’ liv

lives.

lives

es. As noted above, we also asked several

Because

Because of m myy discussion questions related to non-financial coaching

of sensitive,

sensitive, p personal

ersonal non- and counseling behaviors planners might

financial issues with my my engage in during the course of their client

clients theyy seem tto

clients the ob be e 5 23 468 543 80 1,119 engagement. Figure 2 (on page 56) pres-

living a life

life closer tto

o their (0%) (2%) (42%) (49%) (7%) ents the results.

core

core values, enjoying

values, and enjo ying Ninety percent of our respondents explic-

what

what is most imp important

ortant itly state that any information disclosed by

to

to them. the client will be held in strictest confidence.

Because

Because of m myy discussion Twelve percent of financial planners always

of sensitive,

sensitive, p personal

ersonal non- try to establish rapport by sharing their own

financial issues with my my sensitive personal information, in order to

clients

clients mmyy ability

ability tto

o do 5 8 104 694 300 1,111 make their clients more comfortable dis-

a good

good job aatt financial (0%) (1%) (9%) (62%) (27%) cussing their own problems. Another 55 per-

planning is enhanced

enhanced cent sometimes engage in this practice.

or improved.

improved. Thirty-eight percent of our respondents

Because

Because of m myy non- always help their clients understand how a

financial counseling

counseling 29 113 549 344 84 1,119 financial plan may be affected by psycho-

my

my business has (3%) (10%) (49%) (31%) (8%) logical issues, such as security, fear, status,

increased.

increased. or self esteem. Only 17 percent of respon-

dents include information about life plan-

have offered to pray for a client, and 36 per- ners have been asked whether or not their ning and/or personal coaching services in

cent said that a client has asked the finan- client should have children. their promotional and marketing materials.

cial planner to pray with them. Twenty-two We were astonished at the array of Twenty-eight percent make it a point to

percent of our respondents have tried to human frailties emerging in the client- discuss their role as a coach or counselor

bring a client closer to God or to the client’s planner relationship. Our respondents have in life planning during their initial contact

spiritual core values.3 faced client issues including suicide, 10 with prospective clients. We find these per-

Clients’ marriage and other family prob- percent; therapy, 7 percent–9 percent; and centages reflective of the prominent role

lems are issues for many financial planners. drugs, 3 percent–5 percent. Twenty-six that non-financial planning has assumed in

Forty-eight percent of our respondents have percent of respondents have had to the financial planning profession. We also

mediated marital discord. Another 44 per- reschedule a session because of a client’s found it interesting that even with this

cent have mediated problems between a emotional distress. prominent role, only 1.8 percent of our

client and his or her children. Client prob- The intensity of the bond between respondents report that their firm has

lems with extended family members were financial planner and client is illustrated hired a therapist or family counselor in the

experienced by 29 percent of respondents. by our finding that 21 percent of respon- past five years.

Clients have asked 34 percent of planners dents have had a client who established a Because the issues and incidents pre-

whether they should or should not get trust and listed the financial planner as sented in Figure 1 and Table 3 could

divorced, and another 12 percent of plan- either the sole or co-executor of the trust. create personal and administrative costs

54 Journal of Financial Planning | AUGUST 2009 www.FPAjournal.org

DUBOFSKY | SUSSMAN Contributions

for the planner, we probed another behav- Table

Table 3: Rank Or

Rank Order

der of Coaching/Counseling

Coaching/Counseling C

Critical

ritical Inciden

Incidents

ts F

Faced

aced b

by

y

ior: the decision to no longer serve a Financial

F Planners

inancial Planners

client and terminate the relationship.

Inciden

Incidentt Yess

Ye No Responses

Resp onses

Seventy-one percent of respondents

report that they have essentially “fired” a 1 During

During a planning session a client

client became

became 973 334 1,307

emotionally distraught

distraught (e.g.,

(e.g., star

started

ted cr

crying,

ying, (74.4%)

client. Demanding too much time and

trembling,

trembling, sobbing,

sobbing, or became

became violent).

violent).

attention was most frequently cited (by 65

2 You

You w

were

ere ttold

old a secr

secret

et by

by your

your clien

clientt (other than 732 539 1,271

percent of respondents) for a financial

relevant

relevant financial facts),

facts), who said that

that yyou

ou ar

are

e the (57.6%)

planner terminating the relationship. But, only person

person who kknows

nows this

this..

in support of the idea that non-financial 3 You offered

You offered to

to pray

pray for

for yyour

our client.

client. 630 645 1,275

issues and incidents create dissonance in (49.4%)

the planner-client relationship, 40 per- 4 You

You served

served as a mediator

mediator between

between a husband and 620 686 1,306

cent of respondents said they fired a wife because

wife because of their marital

marital discord.

discord. (47.5%)

client because the client’s values or 5 You

You served

served as a mediator

mediator between

between a clien

clientt and his/ 574 731 1,305

lifestyle made the financial planner her children.

children. (44.0%)

uncomfortable. This finding underscores 6 Your

Your client

client asked

asked you

you to

to pray

pray with him/her.

him/her. 461 807 1,268

the personal and administrative costs (36.4%)

incurred when financial planners engage 7 Your

Your client

client designated

designated you you as the person

person tto o ccontact

ontact 446 859 1,305

in non-financial coaching and counseling. event of an emergency.

in the event emergency. (34.2%)

Training and Preparation. This 8 Your

Your client

client asked

asked youyou whether he/she should or 430 842 1,272

divorced.

should not get divorced. (33.8%)

research question deals with the training

9 You

You were

were ask

asked ed by

by an organization

organization to to lobby

lobby your

your 421 853 1,274

that financial planners may have received

client ffor

client or philanthropic

philanthropic donations.

donations. (33.0%)

to properly deal with non-financial issues.

10 You were

You were ask

asked ed by

by a client’s

client’s family member

member tto o 406 864 1,270

We have documented that financial plan-

lobby the client

lobby client on behalf

behalf of that

that family memb

member er (32.0%)

ners face a wide array of human problems (e.g., a child asked

(e.g., asked youyou toto approach

approach his/her parent

parent

that are usually handled by psychologists, [your client]

[your client] ffor

or special

special consideration).

consideration).

psychiatrists, family therapists, and/or 11 You served

You served as a mediator

mediator between

between a clien

clientt and 374 928 1,302

members of the clergy. A priori, we extended family member(s)

extended member(s) (other than sp ouse

spouse (28.7%)

hypothesized that courses and training in children).

and/or children).

therapy, social work, psychology, or coun- 12 You were

You were ask

asked ed by

by an organization

organization to to lobb

lobbyy yyour

our 335 932 1,267

seling should help a financial planner deal client tto

client o include that

that organization

organization as a beneficiary

beneficiary (26.4%)

with these issues. However 40 percent of in a will.

our respondents have had no coursework 13 Either you

Either you or a client

client rrequested

equested thatthat a planning 334 972 1,306

or training related to any kind of non- session be be rescheduled

rescheduled b ecause the client’s

because client’s (25.6%)

financial coaching or counseling. Thirty- distress prevented

emotional distress prevented continuation

continuation of thatthat

nine percent have had one or more col- session.

14 You tried

You tried bringing

bringing a clien

clientt closer to

to God

God (or toto his/ 273 996 1,269

lege courses in therapy, social work,

spiritual “core

her spiritual “core values”).

values”). (21.5%)

psychology, or counseling; 6 percent have

15 Your client

Your client established a trust trust and list ed yyou

listed ou as 268 998 1,266

an undergraduate degree in one of these

co-executor of the trust.

either the sole or co-executor trust. (21.2%)

areas; and 3 percent have a related gradu- 16 Your client

Your client asked

asked youyou whether he/she should or 150 1,118 1,268

ate degree. Thirty-two percent have taken should not havehave children.

children. (11.8%)

professional development seminars or 17 You learned

You learned that

that a clien

clientt was

was thinking

thinking of suicide

suicide.. 129 1,143 1,272

workshops. (10.1%)

Finally, perhaps one’s own personal 18 You were

You were in volved in an intervention

involved intervention to

to get a client

client 110 1,191 1,301

experiences with a professional counselor into therapy.

into therapy. (8.5%)

or life planning coach may help a financial 19 You were

You were in volved in an intervention

involved intervention to

to get a 90 1,212 1,302

planner do a better job handling his/her client’s family memb

client’s member er into

into therapy.

therapy. (6.9%)

clients’ non-financial problems. Thirty-nine 20 You w

You ere in

were volved in an intervention

involved intervention to

to get a 58 1,243 1,301

percent of our respondents have them- client’s family memb

client’s member er into

into drug

drug treatment.

treatment. (4.5%)

selves received psychological counseling 21 You w

You ere in

were volved in an intervention

involved intervention to

to get a 41 1,261 1,302

from a professional counselor; 35 percent client in

client to drug

into drug treatment.

treatment. (3.1%)

www.FPAjournal.org AUGUST 2009 | Journal of Financial Planning 55

Contributions DUBOFSKY | SUSSMAN

Figure 2: Financial Planners’ Behaviors Associated with Non-financial have received some other form of counsel-

Coaching/Counseling ing or therapy from a professional coun-

1. Do you explicitly state that any information the client chooses to disclose will be held selor; and 22 percent have received coach-

in the strictest confidence? ing from a life planning coach. Of those

who have been trained in life planning and

Answer Responses %

coaching, 65 percent said it was important

Yes 1,057 90% or very important, 27 percent said it was

No 120 10% somewhat important, and only 8 percent

said it was not important.

Total 1,177 100%

2. Do you try to establish rapport by sharing sensitive, personal information about your

Discussion

health, family, or history to make the client more comfortable discussing his or her

problems? All survey research is based on samples,

and all conclusions based on those sam-

Answer Responses % ples are subject to questions related to

Always 138 12% validity and reliability. Our results are also

Sometimes 639 55%

subject to those questions. Nevertheless,

the relatively large sample (1,374), com-

Rarely 318 27%

parability of sample characteristics to

Never 72 6% population characteristics, and our

Total 100%

exploratory purpose lead us not to a defin-

1,167

itive conclusion, but to valuable and

3. Do you try to help your clients understand how their financial plans may be affected provocative conclusions.

by psychological issues related to the role money plays in their lives (e.g., security, fear, Spreadsheets, optimization algorithms,

status, self esteem)? Monte Carlo simulations, economic fore-

Answer Responses % casts, and actuarial tables have been and

will continue to be necessary tools for

Always 443 38%

financial planners. But our study under-

Sometimes 600 52% scores and empirically supports the thesis

Rarely 101 9% highlighted in our introduction: financial

acumen is necessary for financial planning

Never 15 1%

but not sufficient. Our study also under-

Total 1,159 100% scores the need for a new set of tools.

In the words of two of our respondents:

4. Do your promotion and marketing materials include information about life planning

and/or personal coaching services you provide?

When people pour out their life’s

Answer Responses % financial history to you, their goals,

Yes 198 17%

their aspirations, it is very difficult for

them not to pour out non-financial

No 954 83% information ... and when they provide

Total 1,152 100% you the non-financial information they

expect non-financial advice. To most

5. During your initial contact with a prospective client do you make it a point to discuss people it is hard to separate the two. I

your role as a coach and/or counselor in life planning? am often asked, ‘How can you know

my goals, if you do not know me?’

Answer Responses %

Yes 323 28% Money is really the last taboo. More

No 820 72%

people will speak to their friends (and

pastors) about their sex life than their

Total 1,143 100% money. Who can admit to friends that

they’ve racked up $103,000 in credit

56 Journal of Financial Planning | AUGUST 2009 www.FPAjournal.org

DUBOFSKY | SUSSMAN Contributions

card bills? Or who can stand up in training of any kind related to non-finan- under-management-528415-1.html.

church (or at the water cooler at work) cial coaching or counseling. Spreadsheets August.

and ask for help in how to allocate their and forecasting, yes, therapy intervention Congressional Budget Office. 2003. Baby

$4 million estate among their children? strategies and counseling, no. Our results Boomers Retirement Prospects: An

indicate that financial Overview. Retrieved from www.cbo.gov/

planners need to listen ftpdoc.cfm?index=4863&type=0.

While the need for coaching is

to what their clients are Kahler, Richard S. 2005. “Financial Inte-

“increasing and while the bond between

planner and client creates the foundation late, and be able to

saying, accurately infer

what clients want to say

but are afraid to articu-

gration: Connecting the Client’s Past,

Present, and Future.” Journal of Financial

Planning 18, 5 (May): 62–71.

for discussing those issues, the ability of

Kahn, Ronnie. 2001. “Money Conscious-

respond appropriately. ness: A Psychospiritual View of Finan-

planners to provide that coaching is

The second article in this cial Planning.” Journal of Financial Plan-

problematic at best.

two-part series (to be ning 14, 2: 128–139.

” published in the Septem-

ber Journal) elaborates

and expands on the spe-

cific strategies for

Kinder, George. 1999. Seven Stages of

Money Maturity. New York: Bantam

Doubleday Dell Publications.

Kinder, George and Susan Galvan. 2006.

acquiring the coaching Lighting the Torch. Denver: FPA Press.

It would have to be a very wealthy skills implicitly and explicitly required by Matson, Mark. 2003. “Shifting From Advi-

parish/employee group to embrace that today’s and tomorrow’s clients. sor to Coach.” Advisor Today 98, 2: 50.

kind of discussion. As a result, a finan- Miller, Katherine and Joy Koesten. 2008.

cial planner is one of the few people

JFP “An Investigation of Emotion and Com-

that clients can speak to about such Endnotes munication in the Workplace.” Journal of

sensitive topics. They often seem eager Applied Communication Research 36, 1.

to share tough decisions and issues. 1. Data for CFP certificants are from O’Neill, Barbara. 1991. “Baby-Boom Eco-

www.cfp.net/media/profile.asp. Data for nomics: Financial Planning for the ‘Big

Divorce, family strife, suicide, drugs, FPA members were provided by FPA. Chill’ Generation.” Journal of Financial

mental health, religion and spirituality, ill- 2. We recognize and stress that ambiguity Planning 4, 3 (July): 142–146.

ness, and death—this reads like a list of exists between the meaning of “finan- Sussman, Lyle and David Dubofsky. 2009.

issues that would and should be managed cial” and “non-financial” issues. Cer- “The Changing Role of the Financial

by a member of the clergy, social worker, tainly, many non-financial coaching and Planner Part 2: Prescriptions for Coach-

psychologist, or physician. Our research counseling activities have important ing and Life Planning.” Journal of Finan-

reveals that financial planners often face financial ramifications. cial Planning 22, 9 (September).

these issues. Knowledge about investments 3. All of the percentages we are presenting Wagner, R. 2000. “The Soul of Money.”

and insurance will not solve these prob- imply that the incident happened at Journal of Financial Planning 13, 8

lems. Possessing advanced degrees in least once for the respondent. (August): 50–54.

accounting, taxation, finance, or invest- Warner, Joan. 2006. “Life Planning Goes

ments will serve planners well, but will not References Mainstream.” Financial Planning 36, 9

be sufficient. To the extent that financial (September): 1–2.

planning is designed to help a client meet Christiansen, Tim and Sharon DeVaney.

personal life goals, coaching and life plan- 1998. “Antecedents of Trust and Com-

ning skills will become requisite skills for mitment in the Financial Planner-Client

financial planners. Relationship.” Financial Counseling and

Herein lies the rub. While the need for Planning 9, 2: 1–10.

coaching is increasing and while the bond Collier, Charles. 2004. “A True Counselor.”

between planner and client creates the Trust and Estates 143, 5: 164.

foundation for discussing those issues, the Compere, Luliane. 2007 “Explosive Growth

ability of planners to provide that coaching for Assets Under Management.”

is problematic at best. Almost half of our Retrieved from www.financial-plan-

sample, 40 percent, had no coursework or ning.com/news/explosive-growth-assets-

www.FPAjournal.org AUGUST 2009 | Journal of Financial Planning 57

You might also like

- The Process of Financial Planning, 2nd Edition: Developing a Financial PlanFrom EverandThe Process of Financial Planning, 2nd Edition: Developing a Financial PlanNo ratings yet

- Four Stages of Planning and Implementation During Covid-19: One Rural Hospital'S Preparations.Document14 pagesFour Stages of Planning and Implementation During Covid-19: One Rural Hospital'S Preparations.Irish ButtNo ratings yet

- Management Practices in The United States of America, Japan, China, Germany, and BangladeshDocument41 pagesManagement Practices in The United States of America, Japan, China, Germany, and BangladeshZahirul Islam86% (7)

- Nonprofit For-Profit Boards VS.: Critical DifferencesDocument8 pagesNonprofit For-Profit Boards VS.: Critical DifferencesDellon-Dale Bennett100% (2)

- Critical Role of Self-Efficacy in Financ PDFDocument8 pagesCritical Role of Self-Efficacy in Financ PDFRjendra LamsalNo ratings yet

- Martines Krista Sum2015Document26 pagesMartines Krista Sum2015Ariel Carl Angelo BalletaNo ratings yet

- Review & Discussion 1-8-9Document7 pagesReview & Discussion 1-8-9ashek123mNo ratings yet

- Research Paper On Job Stress in Banking SectorDocument5 pagesResearch Paper On Job Stress in Banking Sectoraypewibkf100% (1)

- Journal of Personal FinanceDocument13 pagesJournal of Personal FinanceHabib SimorangkirNo ratings yet

- ID 536 Business Planning For Health Organizations Course Syllabus For Spring 2 Term, 2009 April 3 - May 22Document7 pagesID 536 Business Planning For Health Organizations Course Syllabus For Spring 2 Term, 2009 April 3 - May 22Lovis NKNo ratings yet

- Creative DisruptionDocument24 pagesCreative DisruptionJulius WrightNo ratings yet

- 11 PDFDocument15 pages11 PDFWin BoNo ratings yet

- Ej 1088924Document15 pagesEj 1088924Ronaliza GrimpulaNo ratings yet

- 3 1 RohsDocument13 pages3 1 Rohs2056160075No ratings yet

- Employees' Financial Literacy, Behavior, Stress and WellnessDocument12 pagesEmployees' Financial Literacy, Behavior, Stress and WellnessYong Leigh LocusamNo ratings yet

- The Psychology of Financial PlanningFrom EverandThe Psychology of Financial PlanningNo ratings yet

- Financial Literacy and Financial Planning Among Teachers of Higher Education - A Study of Critical Factors of Select VariablesDocument10 pagesFinancial Literacy and Financial Planning Among Teachers of Higher Education - A Study of Critical Factors of Select Variablesrap pedroso100% (1)

- Professional Meeting PaperDocument7 pagesProfessional Meeting Paperapi-355221395No ratings yet

- Finance for Strategic Decision-Making: What Non-Financial Managers Need to KnowFrom EverandFinance for Strategic Decision-Making: What Non-Financial Managers Need to KnowNo ratings yet

- Background of The StudyDocument49 pagesBackground of The StudyReina dominik JunioNo ratings yet

- The Role of A School Business Manager - A Reflective EssayDocument32 pagesThe Role of A School Business Manager - A Reflective Essaykuirt miguelNo ratings yet

- Executive Coaching:: An HR View of What WorksDocument20 pagesExecutive Coaching:: An HR View of What Worksibayraktar775208No ratings yet

- Human Resource ManagementDocument3 pagesHuman Resource ManagementisaacpapicaNo ratings yet

- Witnessing Your Own Cognitive Bias: A Compendium of Classroom ExercisesDocument23 pagesWitnessing Your Own Cognitive Bias: A Compendium of Classroom ExercisesAdrian GuzmanNo ratings yet

- Lack of Organizational Communication and Feedback in National Bank of Pakistan (NBP)Document7 pagesLack of Organizational Communication and Feedback in National Bank of Pakistan (NBP)rida fatimaNo ratings yet

- Final ReportDocument73 pagesFinal ReportAditi Awasthi100% (2)

- Ten Keys To Successful Strategic Planning For Nonprofit and Foundation LeadersDocument12 pagesTen Keys To Successful Strategic Planning For Nonprofit and Foundation LeadersJaziel CabralNo ratings yet

- Financial Analysis Training ReportDocument71 pagesFinancial Analysis Training ReportSaurav PariyarNo ratings yet

- Literature Review Employee Performance ManagementDocument6 pagesLiterature Review Employee Performance Managementafmzsbnbobbgke100% (1)

- Thesis Topic For Finance StudentDocument7 pagesThesis Topic For Finance Studentgjc8zhqs100% (2)

- CDN ED Strategic Human Resources Planning 5th Edition Belcourt Solutions Manual 1Document8 pagesCDN ED Strategic Human Resources Planning 5th Edition Belcourt Solutions Manual 1beverly100% (31)

- Management Principles For Health Professionals 7th Edition Ebook PDFDocument61 pagesManagement Principles For Health Professionals 7th Edition Ebook PDFmaria.bowman208100% (44)

- The Effectiveness of Youth Financial Education A Review of The LiteratureDocument23 pagesThe Effectiveness of Youth Financial Education A Review of The LiteratureMădălina MarincaşNo ratings yet

- Making A Difference - Confidence and Uncertainty in Demonstrating Impact - June 2008Document1 pageMaking A Difference - Confidence and Uncertainty in Demonstrating Impact - June 2008InterActionNo ratings yet

- Financial Literature ReviewDocument5 pagesFinancial Literature Reviewmpymspvkg100% (1)

- Translating Financial Education Into Behavior Change For Low-Income PopulationsDocument19 pagesTranslating Financial Education Into Behavior Change For Low-Income PopulationsHibaaq AxmedNo ratings yet

- Role of Financial MGR!!Document2 pagesRole of Financial MGR!!meetesha_90No ratings yet

- The Ethical Implications of Underfunding Development EvaluationsDocument8 pagesThe Ethical Implications of Underfunding Development EvaluationsPassmore DubeNo ratings yet

- Financial Literacy Around The World PDFDocument58 pagesFinancial Literacy Around The World PDFYuri SouzaNo ratings yet

- Succession Planning Paper - RevDocument25 pagesSuccession Planning Paper - RevAlessandro IbarraNo ratings yet

- The Voice of Experience: Public Versus Private EquityDocument8 pagesThe Voice of Experience: Public Versus Private EquityilyakoozNo ratings yet

- Research Chapter 12 Final Out Put UletDocument20 pagesResearch Chapter 12 Final Out Put UletAlvin TanNo ratings yet

- Leadership and Change Management ThesisDocument4 pagesLeadership and Change Management Thesisashleyallenshreveport100% (2)

- Eadership Development: The Larger Context: Job-Embedded LearningDocument9 pagesEadership Development: The Larger Context: Job-Embedded LearningDeo Quimpo QuinicioNo ratings yet

- Caso de Ensino - Tema 3 - Roles and Attitudes in The Management Accounting Profession An International Study - MAQ - Spring - 2020 - HortonDocument9 pagesCaso de Ensino - Tema 3 - Roles and Attitudes in The Management Accounting Profession An International Study - MAQ - Spring - 2020 - Hortonsaranascimento2003No ratings yet

- (2012) A Delphi Study To Identify The Personal Finance Core Concepts & CompetenciesDocument2 pages(2012) A Delphi Study To Identify The Personal Finance Core Concepts & CompetenciesEugene M. BijeNo ratings yet

- Corporate Law ProjectDocument21 pagesCorporate Law ProjectapoorvaNo ratings yet

- Literature Review On Sme FinancingDocument5 pagesLiterature Review On Sme Financingaflsimgfs100% (1)

- Studies FundingDocument36 pagesStudies FundingJanice LarsonNo ratings yet

- The Subtle Influence: Conflicts of Interest in Financial PlanningFrom EverandThe Subtle Influence: Conflicts of Interest in Financial PlanningNo ratings yet

- Literature Review Workforce PlanningDocument9 pagesLiterature Review Workforce Planningtys0v0kan1f3100% (1)

- Thesis in FinanceDocument5 pagesThesis in FinanceSarah Morrow100% (2)

- A. Introduction: I. Concepts and Frameworks Applied in The StudyDocument21 pagesA. Introduction: I. Concepts and Frameworks Applied in The StudyKristine Astorga-NgNo ratings yet

- Eight Characteristics of Nonprofit OrganizationsDocument4 pagesEight Characteristics of Nonprofit Organizationskingrizu059387No ratings yet

- Finance S Role in The Organisation Finance Direction PDFDocument12 pagesFinance S Role in The Organisation Finance Direction PDFBiya ButtNo ratings yet

- MGMT 1 Midterm CompilationDocument105 pagesMGMT 1 Midterm CompilationSherwyn NeriNo ratings yet

- French 2016Document11 pagesFrench 2016AnonimousssNo ratings yet

- 6476 19812 1 PBDocument11 pages6476 19812 1 PBJuvy ParaguyaNo ratings yet

- 56 Eval and Impact AssessmentDocument37 pages56 Eval and Impact AssessmentSamoon Khan AhmadzaiNo ratings yet

- Who Seeks A Financial Planner? A Review of Literature: August 2016Document21 pagesWho Seeks A Financial Planner? A Review of Literature: August 2016suraj mathurNo ratings yet

- Ancillary Service Management in Restructuring of Power IndustryDocument6 pagesAncillary Service Management in Restructuring of Power IndustryRajesh RishiNo ratings yet

- 10 Texts To Revise Mixed Tenses With KeyDocument9 pages10 Texts To Revise Mixed Tenses With KeyucitelmalyNo ratings yet

- Rashid, Muhammad AMINA - RAHMAT - , CB646306Document11 pagesRashid, Muhammad AMINA - RAHMAT - , CB646306Rajesh RishiNo ratings yet

- Attar, Zaid Kamal - Abdul - Hussein - U1Document8 pagesAttar, Zaid Kamal - Abdul - Hussein - U1Rajesh RishiNo ratings yet

- New Microsoft Word DocumentDocument2 pagesNew Microsoft Word DocumentRajesh RishiNo ratings yet

- New Microsoft Word DocumentDocument2 pagesNew Microsoft Word DocumentRajesh RishiNo ratings yet

- Format For DST TSDPDocument24 pagesFormat For DST TSDPRajesh RishiNo ratings yet

- MeetDocument10 pagesMeetRajesh RishiNo ratings yet

- Recommended: Sign UpDocument6 pagesRecommended: Sign UpRajesh RishiNo ratings yet

- SoftDocument7 pagesSoftRajesh RishiNo ratings yet

- WertDocument2 pagesWertRajesh RishiNo ratings yet

- WertDocument2 pagesWertRajesh RishiNo ratings yet

- Stack Overflow Guidelines: - It Is Not Currently Accepting AnswersDocument10 pagesStack Overflow Guidelines: - It Is Not Currently Accepting AnswersRajesh RishiNo ratings yet

- Disable Automatic Launch at StartupDocument8 pagesDisable Automatic Launch at StartupRajesh RishiNo ratings yet

- An Investigation On The CharacteristicsDocument8 pagesAn Investigation On The CharacteristicsRajesh RishiNo ratings yet

- TableDocument1 pageTableRajesh RishiNo ratings yet

- Individual Financial Planning For Retirement 2008Document456 pagesIndividual Financial Planning For Retirement 2008Rajesh Rishi100% (1)

- ErtainDocument8 pagesErtainRajesh RishiNo ratings yet

- Paper Title (24pt, Times New Roman, Upper Case, Line Spacing: Before: 8pt, After: 16pt)Document6 pagesPaper Title (24pt, Times New Roman, Upper Case, Line Spacing: Before: 8pt, After: 16pt)Satyanarayana M SNo ratings yet

- SCRDocument1 pageSCRRajesh RishiNo ratings yet

- SFGSGSGDocument1 pageSFGSGSGRajesh RishiNo ratings yet

- TableDocument1 pageTableRajesh RishiNo ratings yet

- Commercial Energy and Non Commercial EnergyDocument1 pageCommercial Energy and Non Commercial EnergyRajesh RishiNo ratings yet

- Monkey in The CloudDocument2 pagesMonkey in The CloudRajesh RishiNo ratings yet

- MonkeyDocument2 pagesMonkeyRajesh RishiNo ratings yet

- SFGSGSGDocument1 pageSFGSGSGRajesh RishiNo ratings yet

- Indian Energy ScenarioDocument8 pagesIndian Energy ScenarioRajesh RishiNo ratings yet

- New Microsoft Word DocumentDocument2 pagesNew Microsoft Word DocumentRajesh RishiNo ratings yet

- New Microsoft Word DocumentDocument2 pagesNew Microsoft Word DocumentRajesh RishiNo ratings yet

- The 4% Rule Financial CalculatorDocument8 pagesThe 4% Rule Financial Calculatorsiti norfaizahNo ratings yet

- FAQs Military Buy Back Program - 9 - 24 - 20v2Document1 pageFAQs Military Buy Back Program - 9 - 24 - 20v2DeoyinsNo ratings yet

- 2020052336Document4 pages2020052336Kapil GurunathNo ratings yet

- A Project On Insurance and Pension: by KuldeepDocument26 pagesA Project On Insurance and Pension: by KuldeepdhimankuldeepNo ratings yet

- National Pension SystemDocument2 pagesNational Pension Systemjyotsna jhaNo ratings yet

- Application For Fee Waiver Exemption For Part-Time Tuition FeesDocument2 pagesApplication For Fee Waiver Exemption For Part-Time Tuition FeesRafikiMolNo ratings yet

- Updated Pensions Training - Slides 05.03.18Document101 pagesUpdated Pensions Training - Slides 05.03.18archanaanuNo ratings yet

- Office MemorandumDocument7 pagesOffice MemorandumRekha guptaNo ratings yet

- Financial Accounting Fundamentals: John J. Wild 2009 EditionDocument42 pagesFinancial Accounting Fundamentals: John J. Wild 2009 EditionMariamiNo ratings yet

- GO 406-FD of 2018 Dated 20.09.2018 Mediclaim InsuranceDocument6 pagesGO 406-FD of 2018 Dated 20.09.2018 Mediclaim InsuranceRAGHVENDRA PRATAP SINGHNo ratings yet

- SR NotesDocument91 pagesSR Notesvikas rachakonda100% (1)

- Gowthaman Natarajan Prabha P: Name Name of SpouseDocument1 pageGowthaman Natarajan Prabha P: Name Name of SpouseGautam NatrajNo ratings yet

- GAD Computer OperatorsDocument15 pagesGAD Computer OperatorsKazo InktiNo ratings yet

- The Life Assurance Industry: Products Offered in The MarketDocument3 pagesThe Life Assurance Industry: Products Offered in The MarketMoses EagleNo ratings yet

- LadderforLeaders2023 273 PDFDocument699 pagesLadderforLeaders2023 273 PDFsantosh kumarNo ratings yet

- Deferred Income Tax and Employee BenefitsDocument35 pagesDeferred Income Tax and Employee BenefitsHello HiNo ratings yet

- PROJECT Final Vaishali MamDocument51 pagesPROJECT Final Vaishali MamSanket MhetreNo ratings yet

- Quiz 5B - Exclusions From Gross IncomeDocument11 pagesQuiz 5B - Exclusions From Gross IncomeMychie Lynne MayugaNo ratings yet

- Epf Joint Declaration - RajeshDocument3 pagesEpf Joint Declaration - Rajeshravikoriveda123No ratings yet

- Computation of Taxable Income Under Various HeadsDocument155 pagesComputation of Taxable Income Under Various Headsdajit1100% (6)

- Pension FundDocument22 pagesPension FundsyilaNo ratings yet

- Fund, Which Is Separate From The Reporting Entity For The Purpose ofDocument7 pagesFund, Which Is Separate From The Reporting Entity For The Purpose ofNaddieNo ratings yet

- Shareholders' EquityDocument49 pagesShareholders' EquityPeter Banjao50% (2)

- Independent Circumstances Allowance ApplicationDocument12 pagesIndependent Circumstances Allowance ApplicationShannon RosenfeldtNo ratings yet

- Borang Sg20 Dan KodDocument6 pagesBorang Sg20 Dan Kod9W2YABNo ratings yet

- SBI Common Application With SIPDocument4 pagesSBI Common Application With SIPRakesh LahoriNo ratings yet

- Retirement BenefitDocument66 pagesRetirement Benefitmike tandocNo ratings yet

- Finance (PGC) Department: Sl. No. Points Raised ClarificationDocument3 pagesFinance (PGC) Department: Sl. No. Points Raised Clarificationrajkumar_k_99No ratings yet

- Income Tax Notes LecturesDocument11 pagesIncome Tax Notes LecturesPam G.No ratings yet

- Daily Monitoring Report For CGDF: Senior Finance Controller, Air ForcesDocument4 pagesDaily Monitoring Report For CGDF: Senior Finance Controller, Air ForcesShihab HasanNo ratings yet