Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Holy Images and Likeness, Gilbert Dagron - Article

Uploaded by

Pishoi ArmaniosOriginal Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Holy Images and Likeness, Gilbert Dagron - Article

Uploaded by

Pishoi ArmaniosCopyright:

Available Formats

Holy Images and Likeness

Author(s): Gilbert Dagron

Source: Dumbarton Oaks Papers , 1991, Vol. 45 (1991), pp. 23-33

Published by: Dumbarton Oaks, Trustees for Harvard University

Stable URL: https://www.jstor.org/stable/1291689

JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide

range of content in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and

facilitate new forms of scholarship. For more information about JSTOR, please contact support@jstor.org.

Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of the Terms & Conditions of Use, available at

https://about.jstor.org/terms

Dumbarton Oaks, Trustees for Harvard University is collaborating with JSTOR to digitize,

preserve and extend access to Dumbarton Oaks Papers

This content downloaded from

82.191.49.154 on Thu, 15 Apr 2021 07:25:41 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

Holy Images and Likeness

GILBERT DAGRON

Your artists, then, like Phidias and Praxiteles, went recognized as true and, therefore, valid if the artist

up, I suppose, to heaven and took a copy of the and the art disappear, in other words, if subjectiv-

forms of the gods, and then reproduced these by

ity acting as a screen, and if an illusion which

their art, or was there any other influence which

presided over and guided their moulding?

would be a lie, disappear.

To obtain such a representation "naturally" con-

There these

wrought was, said Apollonius.

works, a wiser and.... Imagination

subtler artist by forming to its "prototype," only hagiography is ca-

far than imitation; for imitation can only create as pable of a radical solution, because it is miraculous.

its handiwork what it has seen, but imagination The saint or Christ himself helps the powerless

equally what it has not seen; for it will conceive of

its ideal with reference to the reality.

artist, or takes his place in order to achieve an ab-

Philostratus, The Life of Apollonius of Tyana, VI, 19 solute likeness.2 In this multiform topos, the image

creates itself; it is a photograph, a relic. In the ab-

I. PAINTING AFTER THE MODEL'S LIKENESS

sence of the shortcut of the miracle, there is also

the longer route of tradition, which traces the most

The Byzantines said that their beautiful icons, sacred iconographic types back to images suppos-

which seem to us to be disembodied, stylized,

idealized images, were the exact likeness of their edly taken from life (like the portraits of St. Luke3

models, that they were both the reproduction of or those of the painter of the Life of Pancratius of

Taormina4). This does not eliminate the artist but

(ixtThzwta) and equivalent to (6[tolwiia) the mod-

els. Sometimes, however, this resemblance seems depersonalizes him by placing him within a line of

to be concrete, as are facial features, physical char- copyists. He is not responsible for the likeness. An

acteristics, dress, and posture; sometimes it is con- ambiguous anecdote was related to Russian pil-

ceived of as more abstract, like the relationship be- grims in Constantinople before a mosaic of Christ

tween a word and what it represents. For instance,

both an inscription and a drawing were called 2See, e.g., Vita S. Niconis Metanoeite (BHG, 1666-67), ed. Sp.

yQau~i, and the verb yQd4Etv means the act of Lambros, N oog'Ekk. 3 (1906), 179-80; ed. O. Lampsides,'O t0?

6vTov Log NCxo)v 6 METavoE~tE (Athens, 1983), 90-92 and

painting as well as describing.' One must be able 202-4; trans. in C. Mango, The Art of the Byzantine Empire, 312-

to say "It is he" or "It is she," and thereby confer 1453 (Englewood Cliffs, N.J., 1972), 212-13. The artist was un-

successful in drawing the portrait of the saint from an oral de-

on an unambiguous, agreed upon, stable pictorial scription. Suddenly a monk appeared and told him that he- re-

language of a given culture, a status similar to that sembled Nikon. It was Nikon himself, a post mortem apparition.

of the written or spoken word. It has to do with The artist discovered the exact image of the saint miraculously

the truth but also with effectiveness, since the be- reproduced on the icon, and all he had to do was add the colors.

3See now H. Belting, Bild und Kult: Eine Geschichte des Bildes

liever hopes for a direct relationship with the holy vor dem Zeitalter der Kunst (Munich, 1990), 70-72. The legend

one through his or her image. In a religious paint- grew as time went on and made St. Luke into a painter of the

Apostles and notjust of the Virgin and Child.

ing, one can recognize not only a model but also 4Pending Cynthia J. Stallman's edition, the text of the Vita of

an artist ("It is a Virgin by Raphael"); one can St. Pancratius of Taormina (BHG, 1410) must be consulted in the

vaunt the skill of this artist and compete with him excerpts given by A. N. Veselovskij, Iz istorii romana i povesti, in

Sbornik otdelenija russkago jazika i slovesnosti imperatorskoj Akademii

by trying to create the same illusion with rheto- Nauk 40, 2 (St. Petersburg, 1886), 65-128. This work was writ-

ric-in an ix~ Qaotg- instead of with form and ten in the latter half of the 8th century to prove the quasi-

color. On the contrary, a cult image can only be apostolicity of the seat of Taormina, but may contain an older

core; cf. M. Van Esbroeck and U. Zanetti, "Le dossier hagio-

graphique de S. Pancrace de Taormina," paper read at the sym-

'Cf. H. Maguire, Art and Eloquence in Byzantium (Princeton, posium Storia della Sicilia e tradizione agiografica nella tarda

1981), 9. antichitai, Catania, 20-22 May 1986.

This content downloaded from

82.191.49.154 on Thu, 15 Apr 2021 07:25:41 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

24 GILBERT DAGRON

in St. Sophia.5 Pleased with

non sit, aut etiam si verum his

est-quod rarissime po- n

work, the artist test accidere-non hoc

cried out,tamen fide ut teneamus

"I have m

quidquam prodest,

you were!" To which an sed ad aliud aliquid

angry utile, q

Chri

fore paralysing perthehoc insinuatur").

artist, Augustine "And

excluded a prior w

the possibility

ever seen me?" The of an image resembling

likeness wasitsper subje

He recognized

was not due to the painter. that "the face of the Lord (or

Virgin or St. Paul) varied infinitely

Apart from hagiography, there according

the different representations

sponses, less definitive but more which each th per

the conundrum of makes" authentic

("Nam et ipsius Dominicaereprod

facies carnis i

numerabilium

at least demonstrate an cogitationum

awarenessdiversitate variatur

o

fingitur at

Let us look briefly ..."). He accepted this diversity

three well-kn due to

through them, at personal

threeimagination of each believer and arta

different

sensibilities. and he understood that this implies an inher

(1) In possibly authentic fragments read at the contradiction, since Christ, the historical charact

iconoclastic Synod of Hieria in 754 and preserved "was unique, whoever he was" ("... quae tame

in the refutation made by Patriarch Nicephorus, unica erat, quaecumque erat"). The solution is

Epiphanius of Salamis denied any historical truth accept these dubious representations, but so as n

for the false images of the prophets, the Apostles, to render them "false objects" ("Nimirum aut

and Christ which were produced by painters solely cavendum est, ne credens animus id quod non v

from their own imagination (i~ L6Wag at<6v det, fingat sibi aliquid quod non est, et speret di

Evvo(ag ... i~ Unovomag ... a&6 6iUag ~vvoUag 6t- gatque quod falsum est"); one must not stop her

but reach beyond them, by thought and throug

avoovttEvot). The representations of Christ with

long hair, a bearded Peter with short hair, and a faith, to the truth that they depict. This text offer

bald-headed Paul were not supported by any his- the basis for religious painting as it will be pra

torical evidence .6 Like Christ in the anecdote, Epi- ticed in the West, but does not take cult images i

phanius and the iconoclasts echoed his words in account, as it leaves figurative representation o

asking the painter, "When did you see them?" but the level of individual imagination and accepts

came to the conclusion that there was a total ab- image only as a necessary but insufficient tran

sence of likeness and condemned the sacred image tion stage.

as a degrading invention. (3) In an answer in the Amphilochia, Photius, like

(2) In some beautiful passages of the De Trini- Augustine, does not believe in the possibility of

painting Christ and the saints as they were, but the

tate,' Augustine explains that one cannot love with-

differences which he recognizes and acknowledges

out knowing nor know without seeing or imagin-

between various representations of the same holy

ing ("Sed quis diligit quod ignorat ... Nemo diligit

person, in particular Christ, are for him cultural

Deum antequam sciat. Et quid est Deum scire, nisi

eum mente conspicere firmeque perspicere?"). and not individual.8 The Greeks, the Indians, and

The believer who reads the Gospel or Paul's the Ethiopians think that the Savior came on earth

Epistles cannot but represent Christ and the in their likeness; but this is no reason for doubting

Apostles with bodily forms. "Whether this image the existence of a historic and unique Christ.

These differences are of the same nature as lin-

corresponds to reality, which is rare, or not, what

is important is not to believe in it, but to achieve guistic differences; the Gospels are the Gospels

another worthwhile knowledge which is suggested whether written in Greek or in another language.

by this representation" (". .. quod autem verum One can hesitate over the physical appearance of

Christ without doubting his incarnation. The icon

5Anthony of Novgorod (1200), ed. Hr. M. Loparev, "Kniga defines itself not only by the form of the model,

palomnik. Skazanie mest svjatyh vo Caregrade Antonija arhie- but by the subject's disposition, the localization of

piscopa Novgorodskago v 1200 godu," Pravoslavnyi Palestinskij

Sbornik 17, 3 (St. Petersburg, 1899), 7; trans. B. de Khitrowo, the image in a holy place, the forms of worship

Itindraires russes en Orient (Geneva, 1889), 90. surrounding it, the inscription and the symbols ac-

6Ed. G. Ostrogorsky, Studien zur Geschichte des byzantinischen

companying it. In spite of cultural specificities, the

Bilderstreites (Breslau, 1929), 71-72, ? 24-26; on the problem of

authenticity, see most recently P. Maraval's clarification, "Epi- icon's meaning, structure, and finality are every-

phane, docteur des iconoclastes," in Nicee II. 787-1987, douze

siecles d'images religieuses, ed. Fr. Boespflug and N. Lossky (Paris, sAmphilochia, 205, PG 101, cols. 948-52; ed. B. Laourdas and

1987), 51-62. L. G. Westerink, Epistulae et Amphilochia, I (Leipzig, 1983), 108-

7VIII, 4-5. 11, ep. 65, to the abba Theodore (864/865?).

This content downloaded from

82.191.49.154 on Thu, 15 Apr 2021 07:25:41 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

HOLY IMAGES AND LIKENESS 25

where the same. An important step of

could be read in the horoscope has been

the new-born

taken. Photius no longer spoke

child,'4 a thief or a of the

fugitive icon

slave could as a

be identi-

simple representation but fied as

fromahiscultural object

description, fraudulent and

substitutions

an object of worship with could be foiled, or the portrait of the typical He

its own raison d'etre. am-

no longer evoked the imagination

bitious or jealous personof couldthe painter

be drawn. About a

but collective imagination, that

hundred words,of a Christian

classified under elementarycivi-

head-

lization which recognizes ings,

itselfenabled in

one to"its" holy

differentiate peopleimages

positively

and possesses the code for them.

by height, skin color,A shapeslightly

of the nose, hairspe-

color

cious analogy with the plurality

and style, the colorof languages

and cut of the beard, etc.al-

In

lows us to set aside the problem of

the first century the

A.D.(?), image's

Diktys like-

and Dares had used

ness, and to replace it thewith

formula the problem

of the eikonismos of its

in their "Journals"

identification. on the Trojan War to paint a portrait of sixteen

Greek and twelve Trojan heroes whom the authors

were supposed to have seen with their own eyes.'15

II. IDENTIFYING BY WORD AND IMAGE

Ajax, the son of Oileus, is "tall, robust, with honey-

To identify a person using simple physical char-colored skin, he has a squint, a beautiful nose,

acteristics, the Greeks and Romans had a codified black curly hair, a thick beard, an elongated face,

vocabulary and a formula, the eikonismos, at theiris a bold warrior, magnanimous, obsessed with

disposal. This formula was widely used in fiscalwomen." 16

and administrative documents in Egypt,9 in works Thereby a curiosity was satisfied that had not

of physiognomy'0 and astrology," and in the been sated in the Iliad, and Homer's poem was

Chronicles of the Reigns.'2 By tradition, an unknown transformed into a kind of Hollywood film. It is

person could be described,'3 a former or future hardly surprising to find in Malalas, in the sixth

emperor could be evoked, the future face of a mancentury, descriptions of several emperors and of

the apostles Peter and Paul in the same style as of

9See J. Fuirst, "Untersuchungen zur Ephemeris des Diktys those of the Trojan War, for the Gospels, by virtue

von Kreta," Philologus 61 (1902), 377-79 and 597-614; J. Hase- of their lacunas, call on the imagination as much

brick, Das Signalement in den Papyrusurkunden, Papyrusinstitut

Heidelberg 3 (Berlin-Leipzig, 1921); A. Caldara, I connotati per-

as the Iliad. Around the same period as the Troika

sonali nei documenti d'Egitto dell'et& greca e romana, Studi della forgers,

Scu- their counterparts, the makers of Chris-

ola papirologica 4, 2 (Milan, 1924); G. Misener, "Iconistic tian Por- apocrypha, readily gave the heroes of the New

traits," CPh 19 (1924), 97-123; G. Hiibsch, Die Personalangaben

als Identifizierungsvermerke im Recht der grdko-dgyptischen Papyri,

Testament a face, a recognizable appearance, a

Berliner juristische Abhandlungen 20 (Berlin, 1968). summary portrait drawn up and transmitted from

'0See esp. E. Evans, "Descriptions of Personal Appearance

aninalleged visual account," an icon in words in re-

Roman History and Biography," HSCPh 46 (1935), 43-84;

eadem, Physiognomics in the Ancient World, TAPS, n.s. 59, 5 (Phil-

sponse to an immense desire to visualize. From an

adelphia, 1969); G. Dagron, "Image de bete et image de Dieu:

La physiognomonie animale dans la tradition grecque et ses '4See, e.g., D. Pingree, "The Horoscope of Constantine VII

Porphyrogenitus," DOP 27 (1973), 224, 229.

avatars byzantins," in Poikilia: Etudes offertes dJ. -P Vernant (Paris,

1987), 69-80.

15Under the name of Diktys and Dares, two forged "Ac-

" See esp. Ptolemy, Apotelesmatica, 111.12, ed. F. Boll and counts"

A. E. of the Trojan War written by presumed eyewitnesses

Boer (Leipzig, 1957), 142-47. Ptolemy is cited word for word have survived: Diktys of Crete claimed he was Idomeneus' com-

in Hephaestio Thebanus, Apotelesmatica, 11.12, ed. D. Pingree, panion, and Dares asserted he had fought in defense of Troy.

I, (Leipzig, 1973), 137-40; see also Abf Ma'shar-Albumasaris, Both texts were apparently written in Greek in the first century

De revolutionibus nativitatum, app. 2, ed. D. Pingree (Leipzig,A.D., but they have been transmitted only in much later Latin

1968), 245 f. A standard usage of eikonismoi is to be found intranslations

the (4th and 5th-6th centuries?): Dictys Cretensis,

texts edited in the Catalogus codicum astrologorum graecorum, I-

Ephemeris belli Troiani, ed. W Eisenhut (Leipzig, 1958); Dares

XII (Brussels, 1898-1953). Phrygii, De excidio Troiae historia, ed. F. Meister (Leipzig, 1873).

12For instance, in Malalas and Cedrenus, Leo Grammaticus, The physical descriptions of twelve Trojan heroes and sixteen

the Ps.-Symeon, the Scriptor incertus de Leone Armenio, forGreekthe heroes disappeared in the Latin Diktys, but were taken

Byzantine emperors; in a horoscope wrongly ascribed tofrom Ste- the Greek Diktys and were reproduced verbatim by Mal-

phanus of Alexandria and in the Annals of Eutychius of Alex- alas (Chronographia, Bonn ed., 103-6) and by Isaac Porphyro-

andria for the caliphs. Cf. Ffirst, "Untersuchungen," 616-22; genitus, son of Alexis I Comnenus (ed. H. Hinck, in Polemonis

C. Head, "Physical Description of the Emperors in Byzantine Declamationes [Leipzig, 1873], 80-88).

Historical Writing," Byzantion 50 (1980), 226-40; eadem, Impe- '6Malalas, Chronographia, 104; Isaac Porphyrogenitus, op. cit.,

rial Byzantine Portrait: A Verbal and Graphic Gallery (New York,

83. Ajax is said to be "obsessed by women" because the authors

1982); B. Baldwin, "Physical Description of Byzantine Emper- of posthomerica declared he had raped Cassandra in Athena's

ors," Byzantion 51 (1981), 8-20. temple.

"3As did the astrologist whom Liutprand met in 968 in Con- '7For Paul, Acta Pauli et Theclae, 3, ed. R. A. Lipsius and M.

stantinople, Liudprendi legatio, 42, ed. J. Becker, Die Werke Bonnet,

Liud- Acta apostolorum apocrypha, I (Leipzig, 1891), 237, and

prands von Cremona, MGH, ScriptRerGerm, 3rd ed., 198. Acta Petri et Pauli, 9 and 21, ibid., I, 183, 188; for Bartholomeus,

This content downloaded from

82.191.49.154 on Thu, 15 Apr 2021 07:25:41 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

26 GILBERT DAGRON

unknown source, Malalasage,

zus),23 tellshair

us t

"old, of medium convenience,

height, with costu

a r

white skin, pale butes. The cult

complexion, eyesi

thick beard, biglike

nose, eyebrows

the t

"identikit

gators by approxi

right posture, intelligent, quick-te

able, cowardly (3)

[or Neither the e

at least timid

"denial"], inspired pletely by the breaks Holy aw Sp

miracles." 18 described or repr

fiable categories

Let us pause a moment to evoke

analogies between diers). a verbal The person eiko

painted icon. moral and physi

(1) Contrary to painter

the ~xQaotg, brings his wh

artistic effects and viduality, establishes butthe it

reader aims

ist, eikonismos simply or spectat at cha

son, never putting fixed him form, or give her " i

making the subjectimage. appear posed,

cant expression, (4) The

as ill-defined,

in uncompleted

anquality of the

identit

papyri it is the icon and the eikonismos springs from their of

equivalent common a sig

historical accounts

function: to identifythe equivalen

the runaway slave, the proph-

ness.20 esied emperor, the saint, that other "wanted" man,

when he appears.

Similarly, the cult Recognition is theeliminat

image important

cumstantial, and thing. aims

The physical features

atof Christ, the Virgin,

pure pre

or the saints, recorded

(2) The eikonismos focuses by presumed eyewitnesses,

on the

are transmitted by description

painstakingly records every or painting in scar

the o

expectation of a reappearance.

point that in papyri thisThis is what we

singulari

might call the prospective dimension of the eikon-

condense the description, and t

ismos and the icon, the importance of which we

("scar") and ?dxovLto6g

shall see later.

are often

Such is the icon, where individu

tained, Ernst Since the genre existed, we might

Kitzinger as have expected

observe

lated details which gradually

to find in hagiographic literature--which was not m

reluctant to make

schema: sometimes forgeries-an eikonismos

a scar (for for al-

Gre

most every saint, vouching for his or her historicity

and foreshadowing his icon. If there were at-

Passio Bartholomei, 2, ibid., II, 1 (Leipzig, 1898), 131; for An- tempts in this direction, they must have been quite

drew, Acta Andreae apostoli cum laudatione contexta, 12, ed. M.

Bonnet, AnalBoll 13 (1894), 320. For a good overview, see Fdirst, limited. As mentioned earlier, the apocryphal Acts

"Untersuchungen," 407-17. give painters some clues; the two main apostles are

'8Chronographia, 256: ... y&gQv 3 f1iQXe, Tfi i XLx described in Malalas as we see them in paintings;

6IOLQLaog, & ava Xdkcag, xov660QL, 6kon6kLog TV e xQav at and several authors of saints' lives describe their

y~cEov,, keux6g, U3t6XkXOQOg, oivotahg roiWg 660aXtoS;g, e- heroes with the obvious intention of fixing an ico-

mbywv, tcdxQ6QLYvog, oa5voQu;g, avaxaetievog, (q6vLjtog, 6 i-

XoXog, t6REtblpTvrog, 6ELk6;, ~0eyy6tevog Ik aveEtcarog nography by this kind of eye-witness account.25

&y(ov Xi 0v aUjLaTovQy6V. See ibid., 257 for Paul.

'9Cf. HUbsch, Die Personalangaben, 96-108, in comments on

But the cases are rare. The Synaxarion of Constan-

formulae such as eix6vLxa (or typd(i xxat exovya0ol) actLvou tinople, compiled in the second half of the tenth

Ltj eL&val ypdppCaTa. century from other synaxaria and menologia,26 gives

20So much so that the eikonismos has become an essential re-

quisite for historical forgeries, associated with expressions like,

some interesting indications, which I summarize

"I saw it with my own eyes"; cf. W Speyer, Die literarische Fil- here. Only thirty-two from more than a thousand

schung im Altertum (Munich, 1971), 73-74; for Diktys: Malalas,

Chronographia, 107.1-8.

21For instance, in P. Oxy. VII, 1022 (A.D. 103): "sine iconismo" 23See the eikonismos given for Gregory in the "Descriptions of

("no special sign"; in Greek, o0khjv o3x iXEt); "iconismus super- the 'God-bearing' Fathers," M. Chatzidakis, 'Ex Tov 'Ehkov Toy

cilio sinistro" ("with a scar on his left eyebrow"); "iconismus

'Palov, 'Ea.'ET.Bvt.Xa. 14 (1938), 412; reproduced in the

Synaxarium CP, cols. 422-23.

frontis parte dextra" ("with a scar on the right-hand side of his

forehead"). Since Antiquity the significance of scars in recogni- 24Cf. Dagron, "Image de bete," 72-74.

tion is a literary topos: in Euripides' Electra, Orestes is identified 25See, for example, the descriptions of Euthymius and Cyria-

by a scar near his eyebrow; in the Odyssey, Ulysses is recognized cus, Theodore the Studite, and Paul of Latros, cited below,

by a scar on his knee. notes 34 and 37-38.

22"Some Reflections on Portraiture in Byzantine Art," ZRVI 26Cf. H. Delehaye, "Le Synaxaire de Sirmond," AnalBoll 14

8.1 ( = M9langes Georges Ostrogorsky) (1963), 185-93. (1895), 396-434; idem, Synaxarium CP, Prolegomena, II-VI; J.

This content downloaded from

82.191.49.154 on Thu, 15 Apr 2021 07:25:41 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

HOLY IMAGES AND LIKENESS 27

notices of prophets and jorsaints

and minor give prophets

physical ma de

fore type.27

scriptions of the eikonismos entirely different ino

Twenty-four

which

these thirty-two eikonismoi areappear

to be found in thein Synax

wha

of the called

is commonly, but incorrectly, apostles the Peter

"Handbookand P

alas, but

of Painting by Elpios-Ulpius the which

Roman,"28 are enrichewhich

is a mixture of disparatefromelements:

the Acta (1)apocrypha

physical de- Pau

scriptions of eleven "God-bearing

The eight eikonismoi Fathers" ofex-

th

in either

tracted from a compilation of these sources

of ecclesiastical history

hagiographic

by a certain Elpios-Ulpius, ten of which origin:

appear in in

th

Macarius of Alexandria,32

the Synaxarion;29 (2) a description of in aseventeen

laudatio derived ma-

from it for Mark the Monk,33 in the works of Cyril

of Scythopolis for abbas Euthymius and Cyria-

Noret, "Menologes, Synaxaires, Men&es, essai de clarification cus,34 in the Apophthegmata Patrum for Arsenius,35

d'une terminologie," AnalBoll 86 (1968), 21-24.

27If one excludes the ekphraseis of martyrs, written in a com- in diverse hagiographic texts for Mark the Evan-

pletely different style, drawing a conventional, unpersonalized gelist,36 Theodore the Studite,37 and Paul of La-

model-portrait: tall in stature, with skin as white as snow, red

cheeks, hair like gold (see the descriptions of Theodore of

Perge, Mercurius, Sabas Stratelates, Philaretus, Synaxarium CP, the Synaxarium under the date of 23 August (ed. H. Delehaye,

cols. 65, 259, 627, 695); and if one excludes the theatrical evo- cols. 917-18, apparatus, lines 56-58); in the Synaxarium "of Sir-

cations of Judas (ibid., col. 788) and John the Baptist (ibid., cols. mond," the notice about Eustathius appears under the date of

931-32), which are also ekphraseis rather than eikonismoi. 21 February (ibid., cols. 480-81) and does not include an eikon-

28The text was first published by A. F. C. Tischendorf, Anec- ismos.

dota sacra et profana (Leipzig, 1861), 129 ff, based on Coislin 296 30 Isaiah, Jeremiah, Ezekiel, Daniel, Malachi, Zephaniah, Hag-

(12th century); M. Chatzidakis published a much better edition, gai, Habakkuk, Nahum, Jonas, Amos, and Hosea (Chatzidakis,

based on an examination of Mosquensis synod. 108, of 993, and op. cit., 409-10; Synaxarium CP, cols. 667, 647, 833, 317, 368,

not just the Coislin: 'Ex Tv 'EhTov roio 'P0aPoCaov, 275, 313, 272-73, 269, 64, 750, 144). These physical descrip-

'En.'ET.Bvu.Itt. 14 (1938), 393-414; fairly recently, F. Winkel- tions gathered by the 12th-century copyist aimed solely at pro-

mann took up the subject afresh and published a text which viding artists with models for distinguishing one prophet from

juxtaposes the "Ulpius Extracts" and their transcription in the another. Some indications, such as "Zephaniah: resembles John

Synaxarium: "Uber die k6rperlichen Merkmale der gottbeseel- the Theologian with a slightly rounded beard," do not imply

ten Viter," in Fest und Alltag in Byzanz, a collection of articles that the "handbook" contained a description of John the Theo-

dedicated to H.-G. Beck, ed. G. Prinzing and D. Simon (Mu- logian now lost: the artists knew how to represent him. The

nich, 1990), 107-27. These authors, especially Winkelmann, Synaxarium CP draws on the same source, but transcribes the

think that the Coislin retains the original form of a handbook notices in a more literary style, misunderstands some words,

for painters written by Elpios-Ulpius after 836 and before 993, and produces some misinterpretations; five eikonismoi were,

which the Synaxarium CP used as a direct source. It is difficult to moreover, omitted for obvious reasons: some words not under-

accept this interpretation, as I shall have the opportunity to stood for Baruch and Joel, indications contrary to tradition for

point out elsewhere at greater length. The title of the Moscow Zechariah (young instead of old), comparisons for Obadiah and

Micah ("resembles the apostle James," "resembles Cosmas the

manuscript ('Ex idv Oih(oU TOO DPotacxlov &QXaLOXOYOUVtYv V

Anargyrus").

Tfg (xxhTroLaOTLox1g itoQ(Cag nEQt ~ XaQaXTQ(O v o)aTLXOv O o-

6Qoyv narQoW) seems to indicate that Ulpius was the compiler 31Chatzidakis, op. cit., 400-402, 411-12; Synaxarium CP, cols.

of an ecclesiastical history, living in Rome or Roman in origin, 778 (Peter), 779-80 (Paul). On references given in the Acta

and probably writing at a fairly early period (5th-6th century?), Pauli et Theclae, see above note 17.

from whose work a later copyist must have extracted various 32Synaxarium CP, col. 404; Palladius, Historia Lausiaca, 18, ed.

eikonismoi from the 4th-5th century Fathers, adding portraits of C. Butler, The Lausiac History of Palladius (Cambridge, 1898-

Patriarchs Tarasius (d. 806) and Nicephorus (d. 828/829). Soon 1904; repr. Hildesheim, 1967), II, 58, where the eikonismos is

other extracts were welded onto this core, which grew like a really equivalent to an eyewitness, since the author asserted he

snowball, and the text of the 12th-century Coislin, with a title had seen Macarius of Alexandria with his own eyes (prooim.,

that artificially retained the name of Elpios-Ulpius, and refer- ibid., 11, 4).

ences to the "God-bearing" Fathers, is only a jumble of odd, 33Synaxarium CP, col. 511; unpublished laudatio, BHG, 2246.

short extracts on Adam, the prophets, Christ, Peter, and Paul. Mark the Monk is apparently a replica of Mark of Alexandria.

As a result, it cannot be said that the Synaxarium CP drew its 34Synaxarium CP, cols. 405 and 89; Cyril of Scythopolis, Vita

descriptive notes from a handbook of the later 10th century Euthymii, 40, 50, ed. E. Schwartz, Kyrillos von Skythopolis (Leipzig,

which was identical to the Coislin, and, even less, can the Syn- 1939), 59, 73; Vita Cyriaci, 21, ibid., 235.

axarium be used as Winkelmann did, to reconstitute this hand- 35Synaxarium CP, cols. 663-64, apparatus, lines 53-55;

book in its most comprehensive state: the Synaxarium borrowed Apophthegmata patrum, Arsenius, 42, PG 65, col. 108.

from the "Ulpius Extracts" for the "God-bearing" Fathers, and 36Synaxarium CP, col. 630, in a hyper-rhetorical style. A por-

from other sources-the same as the Coislin's copyist tran- trait of Mark is preserved in the Passio S. Marci evangelistae

scribed-for the prophets and apostles. (BHG, 1035), 11, ActaSS, April III, XLVII; see also the brief text

29Dionysius Areopagita, Gregory of Nazianzus, Basil of Cae- Deforma corporis ejus (BHG, 1038f) in Perizonianus F 10 C. Van

sarea, Gregory of Nyssa, Athanasius of Alexandria, John Chry- de Vorst and H. Delehaye, Catalogus codicum hagiographicorum

sostom, Cyril of Alexandria, Cyril of Jerusalem, Patriarchs Tar- graecorum Germaniae, Belgiae, Angliae, SubsHag 13 (Brussels,

asius and Nicephorus (Chatzidakis, op cit., 412-14; Synaxarium 1913), 250.7, and in Vaticanus gr. 1660, an April menologion,

CP, cols. 102, 422-23, 366, 383, 399, 219, 399-400, 546, 488, dated 916, C. Giannelli, Codices Vaticani Graeci. Codices 1485-

724). The eikonismos of Eustathius of Antioch, a relatively minor 1683 (Vatican, 1950), 397.22.

character who is, moreover, chronologically misplaced in the 37 Synaxarium CP, col. 216; Vita Theodori Studitae a Michaele mon.

Moscow manuscript, appears in only one of the manuscripts of (BHG, 1754), 56, PG 99, col. 313, description reproduced in the

This content downloaded from

82.191.49.154 on Thu, 15 Apr 2021 07:25:41 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

28 GILBERT DAGRON

appearance was unworthy andtherefore

tros.38 We can conclude, made all men reject

him"),40

arist carried out a tosystematic

Psalm 22:7 ("But I am a worm and no

inqu

carefully man, a reproach of men

reproduced alland despised

the by the

des

saints which he came across in the texts and to people"), and 2 Cor. 5:16 ("Though we have

known Christ after the flesh, yet now henceforth

which he gave the status of eye-witness accounts.

But he found only a few and invented none, by we him no more"). This &"t'tog and tELig

know

proceeding, for example, with a sort of retrover- Christ4' discourages representation, just as the

sion of images into words. And yet, he did polymorphism

occa- that various currents (including the

sionally examine the icons for information not Gnostic) attributed to the Savior. This polymorph-

found in books: if he declared St. Therapon ofism Cy-made him appear to the disciples and later

prus to be an ascetic monk before he became a

generations in the symbolic forms of a child, an

bishop, it was because he had seem him portrayed adult, and an old man (as is the case in the apoc-

as such.39 ryphal Acta Iohannis),42 and, more generally, in the

If the written eikonismos does not long continue form adapted to the level of perfection and psy-

to accompany the cult image, it is because sacred chology of everyone: with Paul's features for The-

iconography soon had no longer any need for the cla, who loves Christ through Paul.43 Origen wrote:

detour of words. From the sixth century onward, "Even if there was just one Jesus, he was multiple

and especially during the iconoclastic period, leg- in aspect for the spirit, and those who looked at

ends proclamed the main types of icons l'sLpo- him did not see him in the same way."44 The poly-

no0CToy (not made by human hands) or "apostolic,"

and certainly miraculous. Since then, the image

40Here I have translated the Greek text of the Septuagint,

simply reproduced itself. It bore its own justifica- which is unambiguous.

tion. It no longer needed historical confirmation, 41Justin, Dialogus cum Tryphone Judaeo, 14 and 49, PG 6, cols.

for it was history itself. 505, 584; Tf [toQ4P akxroO )q 6uoEtoEardur in the Apocryphal

Acts of Thomas, ed. R. A. Lipsius and M. Bonnet, Acta aposto-

lorum apocrypha, II, 2 (Leipzig, 1903), 162. Other references,

III. CONSENSUS: AN EXAMPLE OF notably to Clement of Alexandria and Origen, are to be found

THE IMAGE OF CHRIST in the article "J6sus," DACL, VII, 2 (1927), cols. 2395, 2397-

2400, and in A. Grillmeier, Der Logos am Kreuz: Zur christolo-

It is the consensus of those who look at the cult gischen Symbolik der iilteren Kreuzigungsdarstellungen (Munich,

1956), 42-47.

image which gives it what could be called its truth. 42Acta loannis, 88-89, 93, ed. E. Junod and J.-D. Kaestli, Cor-

When this consensus is created, the image has only pus christianorum, series apocryphorum 1 (Turnhout, 1983),

to resemble itself: it is its own point of reference. 191-93, 197-99; see also Acta Petri cum Simone, 21, ed. R. A.

Lipsius and M. Bonnet, I (Leipzig, 1891), 69; Acta Andreae et

For iconography escapes not only from the ca- Matthiae, 17-18 and 33, ibid., II, 1 (Leipzig, 1898), 84-89, 115-

prices of the artist, but also from the constraints of16; Acta Petri et Andreae, 2 and 16, ibid., II, 1, 117-18, 124; The

historicity. Nothing illustrates this better than theShepherd of Hermas, 18-23, ed. and trans. R. Joly, Hermas. Le

Pasteur, 2nd ed. (Paris, 1968), 126-39. Cf. J. E. Weis-

progressive elaboration of the image of Christ, of Liebersdorf, Christus und Apostelbilder: Einfluss der Apokryphen auf

which a series of texts helps us to retrace the vari- die iiltesten Kunsttypen (Freiburg im Breisgau, 1902), 30-52. On

ous stages. the polymorphism of Christ, see Grillmeier, Der Logos, 49-55;

J. E. Menard, "Transfiguration et polymorphie chez Origene,"

It begins with a refusal. Christ was ugly accord-in Epektasis: Melanges patristiques offerts au Cardinal Jean Danielou

ing to numerous Christians during the first centu- (Paris, 1972), 367-83; A. Orbe, Christologia gnostica (Madrid,

ries, who refer to Isaiah 53:2-3 ("He had neither 1976), II, 127-34; E. Junod, "Polymorphie du Dieu Sauveur,"

in Gnosticisme et monde hellnistique, Publication de l'Institut Ori-

good appearance nor glory; we have seen him and entaliste de Louvain 27 (Louvain, 1982), 38-46; Junod and

he was without good appearance or beauty, but hisKaestli, eds., Acta lohannis, II, 466-93 and 698-700, which in-

cludes a more comprehensive bibliography (470 note 1).

43Acta Pauli et Theclae, 21, ed. R. A. Lipsius and M. Bonnet,

Vita Theodori a Theodoro Daphnopata (?) (BHG, 1755), 113, ibid., Acta apostolorum apocrypha, I (Leipzig, 1891), 250.

col. 216. 44Contra Celsum, II, 64 and IV, 16, ed. and trans. M. Bonnet,

38Synaxarium CP, cols. 312-13, apparatus, lines 44-46; Vita S. I, SC 132 (Paris, 1967), 434-37, II, SC 136 (Paris, 1968), 220-

Pauli junioris, 45, ed. H. Delehaye, in Th. Wiegand, Der Latmos 23; passages cited by Menard, op. cit., 368. See also the Gospel

(Berlin, 1913), 131; description reproduced in the Laudatio, 53, according to Philip, Sentence 26, ed. and trans. J. E. M6nard,

ibid., 154. L'tvangile selon Philippe (Paris, 1967), 58-61 (text), 145-47

39Synaxarium CP, col. 710: "That he had chosen the life of a (commentary): "(Christ) did not reveal himself as he was in re-

monk is what his pictures show by portraying him like one and ality, but as he was seen: great to the great, humble to the

dressed as such." The Synaxarium notice reproduces the indica- humble, an angel for the angels"; the Gospel according to Thomas,

tions of an abbreviated laudatio of Therapon, BHG, 1797-98, log. 13, ed. and trans. A. Guillaumont et al., L'Evangile selon

ed. L. Deubner, De incubatione capita quattuor (Leipzig, 1900), Thomas (Paris, 1959), 8-9, also plays with this subjectivity, which

120-25; it adds only this remark. surprised Photius on reading the Acta apostolorum apocrypha, in

This content downloaded from

82.191.49.154 on Thu, 15 Apr 2021 07:25:41 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

HOLY IMAGES AND LIKENESS 29

morphous Christ had an iconography,45 but

tation.50 A double very no

image

rare, too intellectual and indirect

fact, to for use in wor-chris

Chalcedonian

ship. In this context, only the individual

dicted imagina-

the growing demands

tion could give Christ a true face, and

An anecdote that ex-by

recorded

cluded the possibility of an

in icon.

the early sixth century p

John Chrysostom is probably one of the first

of representation was,to

perh

have proclaimed aloud, on the basis

fifth of a considered

century, new exe- em

gesis of Isaiah and Psalm terpreted

44, that Christ was hand-

as an alternative.5

some,46 but this beautypatriarch (458-471),

was for a long ". ..

time ac-

knowledged as that of the Transfiguration.

painted the portrait Christ

of Our

has in fact two faces: that of an

ered ordinary

hand. It washuman

said that

sioned the of

being and that of the Resurrection, portrait,

which only and th

the disciples Peter, James,

theand John he

Savior were

had witnesses

painted th

by anticipation, when they saw T6b

the middle so asE6og

not tofto hide

3TQoo~htov aToUfir TEQov, children of the

his clothes Hellenes

becoming

white as light, Moses and thatElijah

those appearing

looking at at his

the pic

side (Matt. 17: 12-9; Markthe9: 2-9; Luke 9:

proskynesis was28-36).

address

One wonders why, when have he was thearrested,

presumed he wasorigin

not recognized and had withto belong

pointed

hair: out (Matt.

a crypto-por

26: 46-49). Origen thinks for that he was already

a crypto-pagan by a pain

transfigured and unrecognizable.47

ished for hisOn the con- im

sacrilegious

trary, Epiphanius thinks thethat he looked

Lector added thatlike anothe

the

most ordinary of his disciples.48 For this more

short curly hair, is "more or

less orthodox speculation repov).52

on the only two passages

Tradition soon dist

in the New Testament concerning

retained only the physical

the error ap- of

pearance of Christ, theretween

is an iconographic

two types of tran-

iconog

scription, which is precise but unstable:

straight hair and thethe Syriac

other w

Gospel of Rabbula, whichchose,

was illustrated

as many othersin 586had at do

the convent of Beth Zagda, gives

author ofChrist, depend-

the account or, mo

exact historians"

ing on the illustrated passages, said that t

either a triangular

face with short curly hair and beard,53

appropriate." which would

correspond to the image of Christ among men, or

a long face with long, straight hair, which

50J. D. Breckenridge, Thecorre-

Numismat

(685-695, 705-711 A.D.), American

sponds to his "glory."49 A century later, both faces

York, 1959), 46-62; cf. C. Morrisson

were reproduced on the coins

alogue of

desJustinian II, but

monnaies byzantines (P

in succession and no longer

graphicsimultaneously-as

commentary in Grabar, L'i

39-45, 235-38; E. Kitzinger, "Some

was the case in the Gospel of Rabbula-as if a

in Byzantine Art" (above, note 22),

choice should be made between the two

famous canon 82 oftypes, and in

the Council

as if the decision was made

the after a period

representation of of hesi-

Christ as a hu

ically as a lamb.

51The text can be read in G. C. H

which he saw signs of docetism, i.e., doubts

Anagnostes about the reality

Kirchengeschichte of

(Berlin

the incarnation (Bibliotheca, cod. 114, ed.

ecdote wasR.borrowed

Henry, II,by85).

John of

45 On the iconography of Christ as an

Hist. infant,

eccl., it is young

found man,

in theand

Contra

in old age to signify he encompassed

130, ed. B. time itself,

Kotter, Diecf. H.-Ch. des

Schriften

Puech, Annuaire de l'Ecole Pratique des Hautes Etudes,

(Berlin-New Ve section,

York, 1975),196, 73

and, fu

(1965-66), 122-25; 74 (1966-67), 1115,128-37;

a 75 (1967-68),

conciliar anthology 157-

compose

61.

studied by J. Munitiz, "Le Parisinus

46Expositio in Ps. XLIV, 3, PG 55, cols. 185-86.

arrikre-plan historique," Scriptoriu

47In Matth. commentariorum series, 100, PG 13, col. 1750.

52T6 6 t & l0tXoTEQov UtdQXELv obk

48Ostrogorsky, Studien (above, the

note 6), 72, of

miracle ? 26.

Gennadius, this part

49Cf. J. Leroy, Les manuscrits syriaques a peintures

in the Damascus (Paris, but

extract, 1964),

in Par

117-18, 123, 139 ff, 207-8; pls. by 24-30, 31, 32,of

the Epitome 42. On the lo-

Theodore's Hist. e

cation of the monastery, cf. M. tionMundell Mango,

(see below), "Where

which Was

also justifie

Beth Zagba?" Okeanos (Essays Presented

~tokXOQtXXt toinI. Sevvenko), Har-

6Lky6/TQXcta/6lty6TLX

vard Ukrainian Studies 7 (1983), 405-30; commentary

53Epitome by A.

of Theodore's Gra-

Hist. eccl.

bar, L'iconoclasme byzantin: Dossier

G. archeologique

C. Hansen, op.(Paris,

cit., 1957),

107; 43-

Theoph

44.

de Boor, 112 (reproduced by Leo G

This content downloaded from

82.191.49.154 on Thu, 15 Apr 2021 07:25:41 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

30 GILBERT DAGRON

John of Damascus,

one himself),Theophanes

which was then faithfully repro-Co

Suda, and Nicephorus

duced; (3) a believer whoCallistus

is in the habit of praying h

about this anecdote,

before an icon, which ought

in a church or at home, recognizes

condemnation ofthethe saint fromrepresentation

the image when he appears to him.

like Christ, at a time Such should bewhen

the course of events

this in order torepr

no longer challenged. ensure the logic The debate

of the apparition's on

identification;

face of Christ is for at a loss.

the saint would not be The

recognizediconoif the image

firmed in spite of were not

the like him.texts.

But most of the lives

It of saints

relies,

on images of reference skip a stage and merely note that the saint ap- e

supposedly

time of Christ and peared conserved

not "as he was," but "as hein is depicted

the in

in Jerusalem and thein icons." The monk Cosmas

Rome, or recognized

on ico the

by human hands," which cannot be

apostles Andrew and John 6oov &ant6 fIg wVy &yCLov

consensus, an image of Christ trium

Eix6vYv OEQQag &vakoyL?6Cevog;55 Irene of Chry-

of all the objections sobalantosconcerning

saw appearing before her the great

theo

ness; it had created its own

Basil, Cappadocian like her, history

ToLOftov oLov ai

it had created this imaginary Christ

eLx6veg ypd )ovoL;56 in a letter from Nilus of An-

ours.

cyra, a father implored St. Platon to free his im-

prisoned son, and his son has no hesitation in rec-

IV. THE HAGIOGRAPHIC TOPos OF RECOGNITION ognizing him x toU, MoXdxLg cTby xaaxaTfQa too

&y(ov it 'Tv EiX6vwyv T E6EdOaL. This latter text,

The icon of Christ obviously presents theologi- read at the Second Council of Nicea in 787, was

cal problems of faith and piety that require certain

commented on as follows: "This clearly illustrates

precautions. In the case of the saints, the situation

that it is because he had seen the martyr's icon be-

is much simpler and the triumph of the image is

fore, that he was able to recognize the martyr

assured almost without discussion. From hagiog-

when he came to save him."'57 Note again a varia-

raphy we earlier extracted a topos, that of miracu-

tion of the recognition topos which not only abbre-

lous likeness, which eliminates, by means of mir-viates but furthermore inverts the terms so as to

acle, the hazards of painting and the subjectivity of

highlight the role of cult images: (1) a man has a

the painter to enable the icon to reproduce the ex-

vision of a saint he has never seen portrayed and

act features of its model. But another topos seems

therefore does not recognize him; (2) he gives a

much more widespread, that of recognition, con-

physical description (a written eikonismos) of the

ferring on the image the same function we recog-

person who appeared to a third person, who shows

nized in the eikonismos: it gives particulars permit-

him the saint's icon (or he himself sees an icon of

ting identification. "Such he was," one could say

the saint by chance or design), thus permitting rec-

about a lifelike portrait. "Such he is and you are

ognition. For instance, to take one famous ex-

going to see him as such," one has to say about an

ample: in a life of Constantine, until Pope Sylves-

icon that presages and foreshadows an apparition,

ter has shown the emperor the icons of St. Peter

and whose authenticity no longer requires histori-

and St. Paul, he is unable to identify the figures as

cal proof, since it will be proved by dream or vi-

he saw them in a dream.58 There are many similar

sion.

examples.

The hagiographical topos of recognition should

What conclusion can be drawn? Simply that the

normally be broken down into three sequences: (1)

a witness has seen the saint alive; (2) he has trans-

mitted a precise eikonismos to enable someone to 55Chr. Angelidi, "La Vision du moine Cosmas," AnalBoll 101

(1983), 84.125-28.

paint an icon very like the original (or he painted 56Vita S. Irenae, 13, ed. J. O. Rosenqvist, The Life of St Irene,

Abbess of Chrysobalanton (Uppsala, 1986), 56.9-13; see also 21,

ibid., 94-96.

57Ep. 62, PG 79, cols. 580-81; Mansi, XIII, col. 33: . ..6-

Cedrenus, Bonn ed., I, 611), Souda, s.v. etxo, ed. A. Adler, Sui- 6~eLxta, OTL 6Ldl ZTfg 7EQOeyvwo)~aVrg a Tz 9 elx6vogToo tdtZvQog

dae Lexicon, II (Stuttgart, 1967), 526; Nicephorus Callistus, Hist. gatyvwo aozbv bLtozdvTa, 6O'Yv(xa oCoat a zbv aageytvezo. Cf.

eccl., XV, 23, PG 147, col. 68. H. G. Thfimmel, "Neilos von Ankyra iiber die Bilder," BZ 71

54 The eikonismoi of Christ in a fragment of the Ps.-Andrew of (1978), 10-21.

Crete (E. von Dobschiitz, Christusbilder: Untersuchungen zur christ- 58Vita S. Constantini by Ignatius of Selymbria, 21, ed. Th.

lichen Legenden [Leipzig, 1899], 185*-86*) and in the anony- Ioannou, Mvrl te~ a &ytokoyLxd (Venice, 1886), 186; see also the

mous account on the icon of Maria romana (ibid., 246**-47**) Constitutum Constantini, 8, ed. H. Fuhrmann, Das Constitutum

are in actual fact descriptions of icons said to be consistent with Constantini, Fontesjuris germanici antiqui 10 (Hannover, 1968),

73.

eye-witness accounts of the apostles or Flavius Josephus.

This content downloaded from

82.191.49.154 on Thu, 15 Apr 2021 07:25:41 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

HOLY IMAGES AND LIKENESS 31

relationship between the guised

image and its

as a patriarch, model

6bt ticg has

mQbg T?v ELx6va

been reversed, and that they are no longer at-

6CtoL6OEW0g.63

The image

tached to the past but to the authenticates theIt

future. vision

ismore

no than longer

it

the image that resemblesis authenticated

the saint, by it, because

butconsensus

theis basedsaint

who resembles his image, asimage,

on the is andnaively written

it is from the image that a col- in

the Life of Theodore oflective

Sykeon, where

imagination springs, Sts.

which is simply con- Cos-

mas and Damian appear firmed

to afterwards

Theodore "as

by the imagination of the they

vision- ap-

ary or

pear in their cult images" the dreamer.

(xao' 6 Ino(twoaw

the miracles of Artemius,

oUv a i~ig

girl of twelve

XaTGQgag E~x~vrg i6Ol;oav is snatched from

aVi?T(~ oL the ElQltVOL

"angels of

death" by the saint

&ytol).59 At the Second Council ofand returns to earth.

Nicea, the Thoseread-

ing of a miracle where Cosmas

close to her ask and Damian

her what the appear

angels she had seen

to a patient "in the formwere

they like. They resemble,

take in shetheir

answers, those

repre-

painted standing upright in the church of the

sentations" (iv CxtOvnoiav-UTaL OX[aW), causes the

priest John, topoteretes ofProdromos. She is then asked

the Eastern what Artemius looksto

patriarchs,

make this more than equivocal

like physically. Shecomment:

says that he looks like "This

the icon

clearly shows that it wasonthrough

the left side of the church. This

their confirms,

icons (6LBat

TWv Ex6v(ov) that they oneappeared

and the same time, to the

the reality woman

of the vision and

and healed her."60 Furthermore,

the validity of theif saints

images.64 In herdo not

rapture, the

always resemble their cult images in their visits

little parishioner had simply seen the icons of herto

the faithful, it is becauselocal

they are in disguise. Cos-

church. Her personal imagination was totally

mas and Damian take on the appearance

impregnated of bath

with the imaginary world around

servants or clerks,61 St. Artemius that

her, that of an entire of civilization,

Christian a butcher, which

a sailor, a patrician.62 Thus more

was conceived than

precisely in orderever it is

to avoid strong

their cult image that serves as a reference; to un-

divergences.

mask them one does not refer to their

The scrupulous real

reproduction face,

of icons or

was not

real dress, but to the face

onlyand

fidelitydress as the

to a model but shown in

prevention of any

their icons. That is good enough

divergence, and amounts

the normalization to

of the imagination.

the same thing. At the InSecond Council

eighteenth-century of nun

Bavaria, a pious Nicea,

called

which shows how the Crescentia

Byzantines themselves

posed a difficult problem for the

reacted to hagiographic Church, inventions,

and missed beingBishop Theo-

canonized, for having

dore of Myra confirmed, by of

had visions a the

personal example,

Holy Spirit under the "unusual"

the miracle described in the letter of Nilus of An-

form of a handsome young man, and for having

cyra to which I referred earlier. Something similardistributed images representing these over-

also happened to him: he had difficulties with an personal visions.65 This is exactly what the icon of

archon, and his archdeacon saw in a dream the pa-East Christian civilization was seeking to avoid.

triarch of Constantinople, who said to him: "Let

the metropolitan come to us, and we will make him V. IMAGES OF DREAMS AND VISIONS

give back his possessions." Theodore did not let

himself be taken in: he asked his archdeacon to I recognize the saint from his image, but this im-

age prefigures the vision I shall have of him. This

describe the man who had appeared to him and

is more or less the vicious circle in which we are

noted that the eikonismos did not correspond phys-

ically to the living patriarch, but to St. Nicholas as

he was portrayed on the altar cloth in the church 63Mansi, XIII, cols. 32-33; cf. G. Anrich, Der heilige Hagios

of Myra. The archdeacon himself identified Nikolaos

the in der griechischen Kirche (Leipzig-Berlin, 1913), I, 450.

The Libri Carolini poke fun at Theodore of Myra's simplicity in

man he had seen as having been St. Nicholas dis-

believing in the dream of his archdeacon and his using it as an

argument for cult images (II, 26, ed. H. Bastgen, MGH, Legum

Sectio III, Conc II suppl. 158-61.

59Vita S. Theodori, 39, ed. A. J. Festugi4re, Vie de Theodore de64Miracula S. Artemii, 34, ed. A. Papadopoulos-Kerameus, op.

Sykeon (Brussels, 1970), I, 34; see also 32, ibid., I, 29. cit., 51-55 (esp. 53). On this passage, cf. C. Mango, "On the

60Miracula SS. Cosma et Damiani, 13, ed. L. Deubner, Kosmas History of the Templon and the Martyrion of St. Artemios at

und Damianos (Leipzig, 1907),133; Mansi, XIII, cols. 64-65. Constantinople," Zograf 10 (1979), 43.

61Ibid., 1.20-21, 14.25, 18.43-44; ed. Deubner, op. cit., 99, 650n the notion of "unusual" iconography, cf. Fr. Boespflug,

135, 145. When the saints appear in unusual dress, the hagiog- Dieu dans l'art: Sollicitudini Nostrae de Benoft XIV (1745) et l'affaire

rapher specifies iv oX(jLRta ob tp sEki06tl aUTCog. Crescente de Kaufbeuren (Paris, 1984), esp. 39, 192, 277. Despite

62Miracula S. Artemii, 6, 14, 15, 25, 37, ed. A. Papadopoulos-

its very general title, this book deals only with Crescentia of

Kerameus, Varia sacra graeca (St. Petersburg, 1909), 7.15-16, Kaufbeuren, the bull Sollicitudini nostrae (1745), and papal re-

14.5, 15.12-13, 60.15-16, 35.21. fusal to have Crescentia canonized.

This content downloaded from

82.191.49.154 on Thu, 15 Apr 2021 07:25:41 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

32 GILBERT DAGRON

caught and which gives

are disembodied the

and possess world

no physical charac-

perfect autonomy. teristics; itWere the

is therefore impossible Byzan

to identify some-

aware of this one-way one visually. Nor will leap recognition

into be any easier

th

eral texts tend to after the Resurrection, because the

suggest bodies will

they we

us to define the relationship betw

have been destroyed, as well as the o0Xl~iaa xat

ages and the images of

o?LUEa xa aOfitaa, dreams

all clothes, distinctive signs, or

In his Quaestiones, or scars which individualize the appearance ofthe

Anastasius

half of the seventh century)

each and every one cons

of us. Every man will therefore

the modality ofbe the in Adam's likeness.

union A single form

of will abolish

the

and concluded that, after

physical individuality death,

without affecting the moral o

prived of physical personality.67 Hence the question:

organs noif such long

is the

remain withdrawn until the Resurrection, inca- case, how is it that saints often appear in their

pable of communicating with the world or recog- churches or by their tombs? The answer: these ap-

nizing parents and friends. An exception is made, paritions are not through the saint's souls, but

however, for the souls of saints, illuminated by the through holy angels who take on the appearance

Holy Spirit; but in this instance communication re- of saints (6t' ayykoyv ayltOVY [ oaot(YXo t otVL v

mains limited and indirect. ig Tb E6log -TWv &y(wv). These holy angels aban-

It must be understood that all visions of saints in don the celestial liturgy, at God's command, in or-

churches or by tombs occur via the intermediary derofto appear before a believer in the form of Pe-

ter, Paul, Demetrius, and so on. And the same

the angels and at God's command (8t' dyCyv dyytgwv

rtEOfvaotit, &t' ttL o EntlT e O0). How would it seemingly

be unassailable argument is put forward: if

possible, before the resurrection of the dead, whileone supposes that the vision is really of St. Peter or

the bones and the flesh are still scattered, to see the

St. Paul themselves, then how can their simulta-

saints themselves as fully formed human beings, often

on horseback and armed as well? And if you disagree, neous appearance in the thousands of churches

dedicated to them be explained?68

tell me, how is it that Paul, Peter, or any other apostle,

though unique, has been seen so often at the same

Communication with the other world by visions

time in different places? It is impossible to be in and

moredreams is described by Anastasius and the Ps.-

than one place at the same time, even for the angels;

only uncircumscribed God is able to do that.66

Athanasius as a striking masquerade regulated by

God (but we assume that it could also be the work

A livelier, more popular version of Anastasius'

of the devil), with angels wearing on their faces-

opinion and argumentation is to be found in the

like masks-the images of the saints they repre-

Quaestiones ad Antiochum ducem falsely attributed to

sent.69 This is by no means literary fantasy but a

Athanasius, where the question of recognitiontheory

in which, at the end of the sixth century, Eus-

the afterlife is treated at length. To summarize:

tratius, a priest of the Great Church, had already

after death, brothers, parents, and friends areundertaken

un- to refute, attributing it to "philoso-

able to recognize one another, because their souls

phers," in other words, "free-thinkers."70 The

66Anastasius, Quaestiones, 89, PG 89, cols. 716-20, esp. 717.

Remember that Anastasius' Quaestiones, edited by J. Gretser (In- 67Ps.-Athanasius, Quaestiones ad Antiochum ducem, 22-25, PG

golstadt, 1617) and reprinted in Migne (PG 89, cols. 311-827), 28, cols. 609-13. Like Anastasius, the author makes an excep-

combines two collections usually kept separate in the manu- tion of the saints, who maintained after death some ability to

scripts; cf. M. Richard, "Les veritables Questions et Reponses recognize those they had known, whether dead or alive.

d'Anastase le Sinaite," Bulletin n' 15 (1967-1968) de l'Institut de 68Quaestio 26, ibid., col. 613. This set of Quaestiones is bor-

Recherche et d'Histoire des Textes (Paris, 1969), 39-56, repr. in rowed from Anastasius the Sinaite.

idem, Opera minora (Turnhout-Louvain, 1977), III, 43-64. 69The theme of apparitions through the "lieutenancy of an-

Quaestio 89, which concerns us here, does belong to the "true gels" occurs in Western literature from Ambrose and Augustine

Questions," an authentic work of Anastasius the Sinaite; this is down to Pope Benedict XIV; cf. Boespflug, Dieu dans l'art, 221

confirmed by B. Flusin, "Demons et Sarrazins: L'auteur et le and notes 36-38.

propos des Diegemata steriktika d'Anastase le Sinaite," TM 11 70On Eustratius, author of a life of the patriarch Eutychius (d.

(1991), 381-409. The greater part of Anastasius' Quaestiones et 582), cf. the brief article by J. Darrouzes, "Eustrate de Constan

Responsiones are to be found, rewritten and redistributed, in a tinople," in DSp, IV.2 (1961), cols. 1718 f. His A6yog

later compilation (probably 8th/9th century in the version avaTrQettLxbg atQbg rotg Xtyov-agg ptl veQyeCv Tdg iTv &v-

known to us), the Quaestiones ad Antiochum ducem, wrongly attrib- Og(baov pVuXdgt... has been edited by Allatius (Leo Allacci), in

uted to Athanasius (PG 28, cols. 597-709). The most knowl- his De utriusque ecclesiae occidentalis atque orientalis perpetua de dog-

edgeable student of this literature, M. Richard, remarked that mate de Purgatorio consensione (Rome, 1654), 336-580. This lively

the question of the relationship between the true Quaestiones by polemical treatise (whose authenticity is confirmed by Photius,

Anastasius and the Quaestiones ad Antiochum ducem by the Ps.- Bibliotheca, cod. 171, ed. R. Henry, II, 165-67), is a response to

Athanasius will be fully elucidated only by a thorough study of the theory on the "inactivity" of the soul after death, of which a

the manuscript tradition, though he still thought Anastasius was muted echo is to be found in Anastasius' Quaestiones over a cen-

the earlier: Le Musefon 79 (1966), 61 note 3. tury later.

This content downloaded from

82.191.49.154 on Thu, 15 Apr 2021 07:25:41 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

HOLY IMAGES AND LIKENESS 33

stakes were high, for if ticularly

thepointless,

saints because

werethe image-and

inactivein the

the beyond, it was nofirst useplacegiving money

the holy image-is to the

always a transfigura-

churches. The souls of the saints, he retorted, tion and does not really belong to the past. An "au-

are in "spiritual places," from whence they can thentic" portrait is an imagined portrait and there-

emerge; at God's command, they come down to fore alive. This is probably why the iconography of

earth and appear to us, just like the angels, xat' Christ and the saints followed its own path, rela-

tively unconcerned with the attacks and scruples of

6va~ xaQ i naQ. One might perhaps put forward

the objection that souls are bodiless, and that saints

Epiphanius or others, breaking with the past and

sometimes appear to us armed, on horseback, or written evidence to turn toward the present of col-

in other apparel. To which we answer as follows: lective devotion and the future of the individual

just as the angels, who are by definition asomatoivision or dream, and tacitly replacing a vain idea

(bodiless), imprint visions (6QdoL;g rTUnof0ot), "soof likeness with the reality of a social consensus.

too the souls (of the saints) give impressions that For cult images may resemble anything, but they

are not real but are nonetheless true. Just as themust be self-resembling and be interpreted by all

painter, who with his diversity of colors, makes ob-unequivocally, like words in a language. Where

faith is concerned, only the community counts;

jects present without their existing in reality, bodi-

therefore one of the main differences between re-

less spirits have a limited capacity to create impres-

sions. These should be taken neither for fantasies ligious paintings and icons is that the first is more

nor for real things, but one would be wrong to con- concerned with individual imagination and the

sider that they are not true."7' Eustratius salvagedsecond more severely regulated by social imagery.

what he considered the essential by establishing The eikonismos gradually lost its testimonial func-

that saints after death have energy and are active,tion and was transformed into a recipe and norm

and so it is worthwhile to pray to them, but thein handbooks on how to paint. And the icon, a pro-

mechanism of their appearing is more or less the duction of this normalization, became itself a

same for him as for Ps.-Athanasius or for Anastas- matrix of images. It tells the faithful under what

ius, except that it is not angels but saints them- form he will see the saint appear, and the saint

selves who are their own image-bearers. The com- what face he must assume and what clothes he

parison with painting is enlightening: we are still must wear in order to be recognized. I have men-

in the realm of the imaginary. Waking visions or tioned on this topic two recurrent topoi in the Lives

dreams define themselves as icons. They are visual of the Saints: that of perfect likeness guaranteed

impressions (Tmno~Gg), which are true because a miracle, and that of the recognition of an ap-

by

holy, but without any basis in reality. parition by means of an image. Both aim at elimi-

nating any doubts concerning the conformity of an

Via a roundabout, twisting path, Christianity si-image to the model or a model to an image. This

lently returned to an idea that was dear to Neo- question is taboo. Hagiography does not take per-

Platonic and Pythagorean philosophy: that a figu- sonal beliefs into account any more than does ico-

rative representation is never more than an image nography, but rather normalizes them, contribut-

of an image: to portray the "true image" of a holy ing to a discreet but effective enforcement of

man is not simply to make an accurate reproduc- forms.

tion of his physical traits, but to imagine him in a This limitation of the imagination and exaltation

kind of epiphany.72 The problem of historical like- of the miracle probably did not count as much as

ness is not merely dangerous, insofar as alleged might be thought. I admit to not knowing what the

eyewitnesses are not immune to criticism, but par- Byzantines really thought about icons and visions,

but the few texts on which I have commented show

how critical they were and not at all naive. By

71Eustratius, A6yog &vaTQerTLx6g, 24, ed. Allatius, op. cit.,

518 f. means of prudent definitions, they were capable of

72Plotinus, Enneads, V, 8, 1, ed. and trans. E. Brehier, Plotin. defining the vast domain of the imaginary and of

Enneades (Paris, 1931), V, 135-36: "Phidias created his Zeus giving it autonomous (though strictly controlled)

without taking any tangible model; he imagined him as he working rules. If a vision of a saint was no more

would be, if he deigned to appear before us"; on Socrates: VI,

3, 15, ed. E. Brehier, VI, 1, 143; Philostratus, The Life of Apollo- than an animated image, the miracle of appari-

nius of Tyana, VI, 19, ed. and trans. F. C. Conybeare, II (Cam-

bridge, Mass., 1969), 76-79, text cited above in the introductory tions could easily find a place in daily life, inaQp 4

quotation. See A. Grabar, "Plotin et les origines de l'esthetique

medievale," CahArch 1 (1945), 15-34; Junod and Kaestli, Acta

Iohannis, II, 446-56, includes a useful bibliography. Collkge de France

This content downloaded from

82.191.49.154 on Thu, 15 Apr 2021 07:25:41 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

You might also like

- Bible Before Books: A New Year's ResolutionDocument8 pagesBible Before Books: A New Year's ResolutionPishoi ArmaniosNo ratings yet

- God Wrote A Book: The Wonder of Having His WordsDocument11 pagesGod Wrote A Book: The Wonder of Having His WordsPishoi ArmaniosNo ratings yet

- What Will Make Our Children Happy?: Create PDF in Your Applications With The PdfcrowdDocument9 pagesWhat Will Make Our Children Happy?: Create PDF in Your Applications With The PdfcrowdPishoi ArmaniosNo ratings yet

- Yawning at Majesty: How To Fight Boredom With The BibleDocument10 pagesYawning at Majesty: How To Fight Boredom With The BiblePishoi ArmaniosNo ratings yet

- Desiringgod Org Articles I Never Knew YouDocument1 pageDesiringgod Org Articles I Never Knew YouPishoi ArmaniosNo ratings yet

- Desiringgod Org Articles Bright Hope From YesterdayDocument1 pageDesiringgod Org Articles Bright Hope From YesterdayPishoi ArmaniosNo ratings yet

- Unashamed of The Bible: Ten Aspirations For Christian CommunicatorsDocument14 pagesUnashamed of The Bible: Ten Aspirations For Christian CommunicatorsPishoi ArmaniosNo ratings yet

- Are You Hiding From God's Voice?: Create PDF in Your Applications With The PdfcrowdDocument9 pagesAre You Hiding From God's Voice?: Create PDF in Your Applications With The PdfcrowdPishoi ArmaniosNo ratings yet

- Freedman, David Noel - Variant Readings in The Leviticus Scroll From Qumran Cave 11Document10 pagesFreedman, David Noel - Variant Readings in The Leviticus Scroll From Qumran Cave 11Pishoi ArmaniosNo ratings yet

- American Schools of Oriental ResearchDocument9 pagesAmerican Schools of Oriental ResearchPishoi ArmaniosNo ratings yet

- Historical Catalogue of The Printed Editions of HolyDocument457 pagesHistorical Catalogue of The Printed Editions of HolyPishoi ArmaniosNo ratings yet

- Desiringgod Org Articles Tempt Him To Apologize For GodDocument1 pageDesiringgod Org Articles Tempt Him To Apologize For GodPishoi ArmaniosNo ratings yet

- Ezekiel, P, and The Priestly SchoolDocument9 pagesEzekiel, P, and The Priestly SchoolPishoi ArmaniosNo ratings yet

- The Tabernacle and The Temple in Ancient Israel: Michael M. HomanDocument12 pagesThe Tabernacle and The Temple in Ancient Israel: Michael M. HomanPishoi ArmaniosNo ratings yet

- Why Can't The Devil Get A Second Chance - Final For St. Anselm Journal Updated 12-20-17 PDFDocument18 pagesWhy Can't The Devil Get A Second Chance - Final For St. Anselm Journal Updated 12-20-17 PDFBernard CalimlimNo ratings yet

- To Heaven With The Devil: The Importance of Satan's Salvation For God's Goodness in The Works of Gregory of NyssaDocument16 pagesTo Heaven With The Devil: The Importance of Satan's Salvation For God's Goodness in The Works of Gregory of NyssaPishoi ArmaniosNo ratings yet

- This Content Downloaded From 156.219.236.161 On Sun, 29 Aug 2021 11:36:11 UTCDocument24 pagesThis Content Downloaded From 156.219.236.161 On Sun, 29 Aug 2021 11:36:11 UTCPishoi ArmaniosNo ratings yet

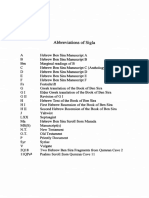

- Abbreviations of SiglaDocument1 pageAbbreviations of SiglaPishoi ArmaniosNo ratings yet

- This Content Downloaded From 197.40.63.213 On Sun, 15 Aug 2021 15:42:47 UTCDocument13 pagesThis Content Downloaded From 197.40.63.213 On Sun, 15 Aug 2021 15:42:47 UTCPishoi ArmaniosNo ratings yet

- This Content Downloaded From 156.219.236.161 On Sun, 29 Aug 2021 11:42:04 UTCDocument13 pagesThis Content Downloaded From 156.219.236.161 On Sun, 29 Aug 2021 11:42:04 UTCPishoi ArmaniosNo ratings yet

- 287029Document7 pages287029Jake RojasNo ratings yet

- Ezekiel Babylonian ContextDocument15 pagesEzekiel Babylonian ContextaslnNo ratings yet

- Matthew'S Sitz Im Leben and The Emphasis On The Torah: F.P. ViljoenDocument23 pagesMatthew'S Sitz Im Leben and The Emphasis On The Torah: F.P. ViljoenPishoi ArmaniosNo ratings yet

- (9789004324732 - Sibyls, Scriptures, and Scrolls) The Social Location of The Scribe in The Second Temple PeriodDocument16 pages(9789004324732 - Sibyls, Scriptures, and Scrolls) The Social Location of The Scribe in The Second Temple PeriodPishoi ArmaniosNo ratings yet

- Confronting Antisemitism NewDocument1 pageConfronting Antisemitism NewPishoi ArmaniosNo ratings yet

- REFLECTIONS ON THE COMPOSITION OF MT 8,1-9,34 Author(s) William G. ThompsonDocument25 pagesREFLECTIONS ON THE COMPOSITION OF MT 8,1-9,34 Author(s) William G. ThompsonPishoi ArmaniosNo ratings yet

- Old TestamentDocument3 pagesOld TestamentPishoi ArmaniosNo ratings yet

- Old TestamentDocument3 pagesOld TestamentPishoi ArmaniosNo ratings yet

- Holy or Foolish Gnostic Concept S of TheDocument18 pagesHoly or Foolish Gnostic Concept S of ThePishoi ArmaniosNo ratings yet

- NCE LifeFaithDocument104 pagesNCE LifeFaithAnuradhatagoreNo ratings yet

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeFrom EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (5794)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingFrom EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (400)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeFrom EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (537)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceFrom EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (895)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)From EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Rating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (98)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerFrom EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (271)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryFrom EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (231)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItFrom EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (838)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceFrom EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (588)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealFrom EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (74)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureFrom EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (474)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaFrom EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (266)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaFrom EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (45)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnFrom EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (234)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyFrom EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (2259)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreFrom EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (1090)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersFrom EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (344)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)From EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Rating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (121)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesFrom EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (821)

- Where Does NBDP Fit in GMDSS and How To Use ItDocument14 pagesWhere Does NBDP Fit in GMDSS and How To Use ItKunal SinghNo ratings yet