Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Triage Process in Emergency Departments: An Indonesian Study

Uploaded by

IntanPermataSyariOriginal Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Triage Process in Emergency Departments: An Indonesian Study

Uploaded by

IntanPermataSyariCopyright:

Available Formats

See discussions, stats, and author profiles for this publication at: https://www.researchgate.

net/publication/307615148

Triage process in Emergency Departments: an Indonesian Study

Article in Nurse Media Journal of Nursing · June 2016

DOI: 10.14710/nmjn.v6i1.11819

CITATIONS READS

2 2,568

3 authors:

Nana Rochana Julia Morphet

3 PUBLICATIONS 4 CITATIONS

Monash University (Australia)

67 PUBLICATIONS 939 CITATIONS

SEE PROFILE

SEE PROFILE

Virginia Plummer

Federation University Australia

162 PUBLICATIONS 1,350 CITATIONS

SEE PROFILE

Some of the authors of this publication are also working on these related projects:

Peninsula Health Mental Health Research View project

Construction and set up of field hospital View project

All content following this page was uploaded by Virginia Plummer on 02 December 2016.

The user has requested enhancement of the downloaded file.

Nurse Media Journal of Nursing, 6 (1), 2016, 37 - 46

Available Online at http://ejournal.undip.ac.id/index.php/medianers

Triage process in Emergency Departments: an Indonesian

Study

Nana Rochana1, Julia Morphet2, Virginia Plummer3

1

Department of Nursing, Diponegoro University, Indonesia

2

School of Nursing and Midwifery, Monash University, Australia

3

School of Nursing and Midwifery, Monash University, Australia

Corresponding author: na2rochana@gmail.com

ABSTRACT

Background: Triage process has rapidly developed in some countries in the last three

decades in order to respond to the demand for emergency services by growing

population and emergency health needs. However, this development does not appear to

match in Indonesian hospitals. The triage process in Indonesia remains obscure.

Purpose: This study aimed to describe triage process in Indonesia from a range of

different perspectives.

Methods: The research design of this study was descriptive qualitative using semi-

structured interviews of 12 policy makers or persons responsible from 5 different

organizations which informed triage practice in Indonesia. The data were analyzed

using a three step content analysis.

Results: The result produced 3 themes. First, four steps of triage process ranging from

receiving to prioritizing were reported as the triaging procedures in Indonesia which

were almost similar to the international literature except for a re-triage step. Second,

primary and secondary triage processes were also applied in all emergency departments

in Indonesia. Last, no prolonged waiting time in Indonesia could be assumed whether

the triage process was effective and efficient or it was only a quick process of sorting to

rapidly increase the number of patients in the treatment rooms. Out of the themes, the

result also indicated that the involvement of nurses in health policy development in

Indonesia needed support

Conclusion: Triage process in Indonesia still needs improvements. Patient’s re-triage

and evaluating secondary triage should be given more frameworks in the future. An

effective and efficient triage process in Indonesia will best manage the number of

patients in the treatment rooms and therefore further observational researches on

patterns and trends are needed. Moreover, including the role of nurses as policy makers

in the curriculum of nursing undergraduate and post-graduate degrees would give nurses

the evidence to seek out policy making positions in the future

Keywords: Triage process, emergency department, Indonesia, triage practice, waiting

times

Copyright © 2016, NMJN, p-ISSN 2087-7811, e-ISSN 2406-8799

Nurse Media Journal of Nursing, 6 (1), 2016, 38

BACKGROUND

The triage process has become an important element of emergency care service since it

is a continuous process which ensures that patients obtain a level of care appropriate to

their clinical need and in a timely manner (FitzGerald, Jelinek, Scott, & Gerdtz, 2010).

Prior to the 1960s, the emergency triage process was performed by doctors. However,

nurses have taken this role from doctors in the last fifty years in the US (Lahdet,

Suserud, Jonsson, & Lundberg, 2009). Nurses then have become the first health care

professionals, especially in the US, the UK, and Australia to assess and prioritize the

patients presenting to EDs, while physicians attend to the appropriate treatments in the

next step of emergency care (Brown, Higgins, Bridge, & Cooke, 2001; College of

Emergency Nursing Australasia (CENA), 2007; Nixon, 2008). The roles of triage nurses

have developed markedly in line with the needs for immediate emergency care which

requires rapid triage process, and the development of National Health Policies (Brown,

et al., 2001; Funderburke, 2008; Nixon, 2008).

In addition to the expanding roles of triage nurses, the development of triage systems in

some countries has increased significantly in the last three decades ranging from three

to five triage scales (Cooper, 2004; FitzGerald, et al., 2010; Funderburke, 2008; Gilboy,

Tanabe, Travers, & Rosenau, 2011; Lahdet, et al., 2009). A rapid and efficient process

of these systems have been proven to generate some positive aspects in Emergency

Departments (EDs), such as reducing overcrowding and patient waiting times;

increasing immediate assessment, flow of patients, and patient satisfaction; improving

patient outcomes and patient safety; and controlling infection (Augustyn, Ehlers, &

Hattingh, 2009; Bruijns, Wallis, & Burch, 2008; Chan & Chau, 2005; Coughlan &

Corry, 2007; Göransson & von Rosen, 2010; Woolwich, 2000). Funderburke (2008,

p.181) also recommends that a shortened and focused triage process with standing

orders for care initiation either by nurses or doctors can reduce admission and ‘door-to-

physician’ times in EDs. Cooper (2004) and Funderburke (2008) point out that this

process, a method to sort and prioritize the ED patients based on their clinical

conditions, has become a research agenda in EDs.

On the other hand, this growth of triage process is not happening worldwide and for

many countries including Indonesia, the development of emergency triage remains

stagnant. According to the guideline of the triage system endorsed by the Ministry of

Health in 1992 (Ministry of Health The Republic of Indonesia, 1999), the triage process

includes receiving the patients, a primary and brief assessment, and triage decision

making. Every patient presenting to EDs should be triaged. The implementation of

triage process in EDs varies amongst hospitals according to the level of the emergency

department, though the basic principle of the triage system is still the same within this

guideline. The decree of the Minister of Health no 856/Menkes/SK/IX/2009 declares

that emergency departments are classified into four levels which are level I, II, III, and

IV ranging from the lowest to the highest. Each level has criteria of emergency services

and human resources availability. These levels of EDs are closely related to the types of

hospitals. Emergency department level IV should be owned by type “A” hospitals while

type B hospitals should have emergency level III and so on. The decree also states that

the triage room should be separated from other rooms for ED level II to IV. This triage

Copyright © 2016, NMJN,p-ISSN 2087-7811, e-ISSN 2406-87

Nurse Media Journal of Nursing, 6 (1), 2016, 39

room contains simple equipment, stretchers, triage documentation, and colored tags

(Minister of Health The Republic of Indonesia, 2009).

Even though there is a guideline of the triage process endorsed by the Ministry of

Health in 1992, an evaluation of its implementation seems unlikely and has not been

published. Little new information has been gained about triage systems in Indonesia in

the 24 years since the decree of Health Minister regarding the guideline of the current

triage system. There have been no published studies comprehensively investigating the

triage systems including triage process in Indonesia. Consequently, the triage process in

Indonesia is not clearly defined. Therefore, this study is needed to undertake in order to

get better understanding of Indonesian triage process so providing a new perspective to

the future development of the local triage system and its contribution to emergency

health.

OBJECTIVE

This study aims to describe triage process in Indonesia from a range of different

perspectives.

METHODS

The study was a descriptive qualitative research involving interviews with policy

makers such as directors/ chairman, vice chairman, policy advisors, senior

administrators, heads of installation, unit managers/ coordinators, heads of department/

division, heads of organizations or members of standing committees in the organizations

from five different organizations which informed triage practice in Indonesia. The data

reached saturation when twelve participants had already been recruited. The researchers

had obtained ethics clearance and approvals from an Australian university and

Indonesian authorities prior to data collection. The data were analyzed manually using

content analysis to produce themes. The quality of the data had been established through

member checking, peer debriefing and audit trail. However, only seven out of twelve

participants provided the feedback for member checking.

RESULTS

The result showed that the majority of participants (n=8) were doctors and four

participants were nurses. Content analysis resulted in 3 themes which were: triage

procedure in Indonesian emergency departments consisted of receiving patients,

assessing, deciding, and prioritizing; that two types of triage process implemented in all

EDs in Indonesia were primary and secondary triage process; and no long waiting times,

either pre-triage or post-triage waiting times, found in EDs in Indonesia except mass

casualty incidents occurred.

Triaging procedure

All participants agreed that triage process occurred from patient’s arrivals to

prioritization according to their clinical conditions. This triaging procedure consisted of

receiving patients, assessing, deciding, and prioritizing. Each process of the triaging

procedures will be outlined in the following.

Copyright © 2016, NMJN,p-ISSN 2087-7811, e-ISSN 2406-87

Nurse Media Journal of Nursing, 6 (1), 2016, 40

During the first process, two participants reported that emergency patients would meet

trieurs and emergency helpers within five minutes from arrivals.

“Triage process is started when patients arrive at the emergency departments. The

triage officers will proactively pick the patients up at their arrivals … they do not

just sit and wait for the patients to come …” (Doctor 5).

“When the patients come, they will be accepted by triage officers and emergency

helpers. They will come to the patients according to their conditions whether the

patients need stretchers, wheelchair, or can walk.” (Nurse 1)

Afterward, the patients would be assessed by trieurs through brief primary assessments

which was called assessing process. The majority of participants reported that primary

emergency assessments consisting of airway, breathing, and circulation examinations

were commonly applied to the patients in this process. Two participants added other

assessments which were levels of consciousness, general complaints, and medical

histories. Trieurs usually used a form or checklist which included a set of assessments

and the triage categories.

“First of all, we will do anamnesis … just like common anamnesis … chief

complaints and medical histories … and then physical examinations” (Doctor 4).

“We use an emergency patient form which is consisted of colored labels of

categories and an assessment format … when the patients arrive, they will be

observed their level of consciousness; assessed their airway, breathing, and

circulation functions; and asked their medical histories and chief complaints.”

(Nurse 2)

On the other hand, there were different implementations of vital sign assessments in

triage. Two participants reported that vital sign assessments were done during triage.

“Patients will be physically assessed their airway, breathing, and circulation status

… their vital signs … during triage …” (Doctor 2).

“Clinical urgency will be assessed during triage based on the assessment of vital

signs.” (Doctor 5).

However, one participant explained that these assessments were conducted in the

treatment rooms since these assessments took time and needed proper equipment.

“The assessment of vital signs … no, it will be done later … in the treatment room

… not in the triage area … too long as it requires equipment.” (Nurse 3).

Two other participants described that these assessments were part of triage activities

though several conditions were applied, especially for blood pressure and temperature

measurements.

“Physical examination and vital sign assessment are done according to assessment

format, for example respiratory … it can be assessed through inspection, look …

Copyright © 2016, NMJN,p-ISSN 2087-7811, e-ISSN 2406-87

Nurse Media Journal of Nursing, 6 (1), 2016, 41

and then heart rate and pulse were done by palpation. Assessments which do not

need equipment yet can be done quickly.” (Nurse 2).

“In the triage area, a set of vital sign equipment has been prepared yet we need to

look at the patients’ condition … if they are false emergent patients, vital sign

assessments can be carried out. However, if the patients are emergent patients,

they will be directly brought to the treatment room without being assessed their

vital signs.” (Nurse 1)

Following the assessment, triage decision was made by trieurs. All participants

described that the patients were sorted based on the data gained from assessment. The

accuracy of triage decision would be depending on trieurs’ ability and complete

assessment data. The patients then were prioritized to one of four categories: red,

yellow, green, or black and were sent to the related treatment rooms. This was called

prioritizing. Once the patients were sent to the treatment rooms, this triage process

ended.

Primary and secondary triage process

All participants pointed out that primary triage including assessing and prioritizing was

the basic activities of triage in Indonesia. Nevertheless, there were some other additional

activities done during triage process which were simple medications and simple

interventions.

“We usually provide simple medications in the triage area … such as antipyretics

… to convince the patients that they have already got help and to relieve their pain

…” (Doctor 2).

“Basically, what we are doing during triage is pure assessment and prioritization.

However, when the patients come and require emergency care then simple

interventions can be given during triage, for example applying oxygen mask and

administering oxygen therapy. On the other hand, laboratory and radiology

examinations are rarely conducted during triage.” (Nurse 3).

One participant explained that secondary triage was often conducted in type C and D

hospitals as triage doctors in these hospitals were also working as emergency doctors.

As a result, doctor’s orders or treatments were done during the triage process.

“Triage doctors are not given authorities to do any interventions related to airway,

breathing, and circulation problems in teaching hospitals. They only sort and

prioritize the patients. On the other hand, their authority is different in the lower

level hospitals, such as type C and D hospitals as well as private hospitals. Since

triage doctors in these hospitals are also emergency doctors, they commonly give

interventions and treatments in the triage area. In other words, they have double

jobs here … as triage doctors and as emergency doctors.” (Doctor 2)

No prolonged waiting times

Related to the length of stay in EDs, all participants outlined that the maximum hours

patients could stay in EDs were 6-8 hours.

Copyright © 2016, NMJN,p-ISSN 2087-7811, e-ISSN 2406-87

Nurse Media Journal of Nursing, 6 (1), 2016, 42

“Ideally, the patients can stay in the emergency departments for maximum 6 hours

as the standard” (Nurse 3).

This duration was a standard of time endorsed by the Ministry of Health. However, this

maximum length of stay could be extended to 1x24 hours, 2x24 hours, and 5x24 hours

when access block happened. Furthermore, almost all participants described that the

triage process commonly took less than 5 minutes and reported that there was no long

pre-triage waiting time except mass casualty situation occurred.

“The triage process is about 5 minutes … or less because the government states

that the response time is maximum 5 minutes” (Doctor 2).

“The standard says 5 minutes so we try to fit with that” (Nurse 4)

The majority of the participants reported that ED patients did not wait to obtain

treatments after being triaged. The patient would be sent to the related treatment rooms

based on triage decision without wait although the possibility to have overcrowding in

the treatment rooms, especially label green, was high. However, they explained that

long post triage waiting times and overcrowding in the treatment rooms were rarely

happened in tertiary EDs as they had adequate nurses and doctors. On the other hand,

the phenomena were likely to occur in the lower level EDs.

“For the detail how long patients wait, it depends on the hospital and the

availability of human resources…in the low level of EDs, how long patients wait

will rely on the skill and the speed of triage doctors…but triage doctors generally

are also emergency doctors in the low level EDs, so the patients will have to wait

longer for treatments in these EDs.” (Doctor 1)

DISCUSSION

The result showed that doctors dominated the positions of policy makers in emergency

settings in Indonesia. This is supported by Shields and Hartati (2003) in their study

regarding nursing and health care in Indonesia. They report that one problem in

Indonesian health structure is the lack of nurses’ status compared with doctors. Doctors

dominate health services especially vital and powerful positions. The researchers

suggest that nurse leaders should in the future seek to achieve key positions in

organizations or government bodies to influence policy, services and as a result change

their status and the status of nursing. Even though this study involved a small sample, it

was noted that four nurses and eight doctors were in policy making positions and that

the involvement of nurses in health policy development in Indonesia needed support as

it did internationally. Nurses should ensure that they were invited to consult on policy

making positions. Including the role of nurses as policy makers in the curriculum of

nursing undergraduate and post-graduate degrees would give nurses the evidence to

seek out policy making positions in the future.

Triaging procedure

The triaging procedure consisted of receiving patients, assessing, deciding, and

prioritizing. These steps are almost similar to the six steps of triage process by Ganley

and Gloster (2011) which start from establishing rapport at the initial contact to

Copyright © 2016, NMJN,p-ISSN 2087-7811, e-ISSN 2406-87

Nurse Media Journal of Nursing, 6 (1), 2016, 43

monitoring and evaluation. However, there was no monitoring and evaluation step in

Indonesian triage process since this step was no longer the responsibility of trieurs but

emergency officers in the treatment rooms. According to the literature, patients’

reassessment, especially those who are waiting for treatment, should be done

periodically by trieurs for patient safety (Ganley & Gloster, 2011; Mackway-Jones,

Marsden, & Windle, 2006). During the first step, triage officers who received the

emergency patients were not only doctors and nurses but the helper also accepted them.

This result was quite opposite with the literature. The literature points out that nurses

and doctors are the responsible persons in triage process as trieurs. (Beveridge, 1998;

Brown, et al., 2001; Bruijns, et al., 2008; Chan & Chau, 2005; College of Emergency

Nursing Australasia (CENA), 2007; FitzGerald, et al., 2010; Gilboy, et al., 2011; Ng et

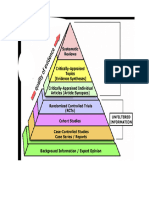

al., 2010; Russ, Jones, Aronsky, Dittus, & Slovis, 2010). In the assessment step, the

assessment techniques were almost similar to the assessments suggested by CENA in

the ETEK (Figure 2). They consist of chief complaint, general appearance, airway,

breathing, circulation, disability, environment, limited history, and co-morbidities

(Department of Health and Ageing, 2007). However, there were different

implementations of vital sign assessments in Indonesian triage. Vital sign assessment

was not consistently conducted in triage process. According to the literature, the

assessment of vital signs is important to carry out during triage. The ATS recommends

assessing vital signs during triage process except blood pressure. However, the other

vital signs, such as respiratory rate, work of breathing, heart rate, pulse, pulse

characteristics, and conscious state should be conducted (Department of Health and

Ageing, 2007). Assessing vital signs is also supported by Sieger, et al. (2011) who show

that a high reference urgency of under-triage in children is caused by lack of vital sign

assessment. Therefore, a systematic assessment is recommended. On the other hand,

Gerdtz and Bucknall (2001) find that objective physiological data, such as vital signs

are rarely used by nurses to decide patient category. Therefore, trieurs should be

encouraged to conduct vital sign assessments during triage process.

The triage assessments in Indonesia

1. Airway, breathing, and circulation assessments

2. Level of consciousness

3. Chief complaints

4. Medical histories

5. Vital sign assessments

Figure 1. The summary of triage assessment in Indonesia

Primary and secondary triage process

Even though primary triage process was the main process in Indonesia, the secondary

triage, such as simple medication and interventions, was also conducted in EDs. This

phenomenon might happen due to dual responsibilities of doctors as triage doctors and

emergency doctors in EDs of type C and D hospitals. Apart from this reason, the

literature also describes a broad use of secondary triage which contains additional triage

activities during triage process beside sorting and categorizing. They include

Copyright © 2016, NMJN,p-ISSN 2087-7811, e-ISSN 2406-87

Nurse Media Journal of Nursing, 6 (1), 2016, 44

administering simple medications, ordering x-ray and laboratory examination, providing

prescriptions and procedures, requesting bed and referring (Brown, et al., 2001; Cronin

& Wright, 2005; Lindley-Jones & Finlayson, 2000a, 2000b; Nixon, 2008). Even though

these activities may improve the triage process, Brown, et al. (2001) still recommend

future studies to evaluate this expanding triage process.

No prolonged waiting times

Long waiting times, either pre-triage or post-triage waiting times, were not found in

EDs in Indonesia except mass casualty incidents occurred. The Ministry of Health also

set 5 minutes of maximum response time for ED patients (Minister of Health The

Republic of Indonesia, 2009). This meant that all patients presenting EDs regardless

their urgency should have initial contact with health care professional or trieurs within 5

minutes from arrival. Consequently, patients might not need to wait to be triaged though

this response time seemed too long for patients who needed resuscitation. On the other

hand, considering a high number of ED presentations in Indonesia yet limited ED

resources, some problems such as long waiting times and overcrowding should

potentially be yielded. However, they were not reported by the finding. This finding was

surprisingly different with the literature. According to the literature, long ED waiting

times and overcrowding are likely to happen when a number of ED presentations are

high (Quattrini & Swan, 2011). In order to solve these problems, a rapid and effective

triage process should be applied. It has been proven to reduce ED overcrowding and

long waiting times (Bruijns, et al., 2008; Quattrini & Swan, 2011). No prolonged

waiting time in Indonesia could be assumed whether the triage process was effective

and efficient or it was only a quick process of sorting to rapidly increase the number of

patients in the treatment rooms. Little information is gained regarding this. Therefore,

further observational research is needed to explore the triage process in Indonesia.

This study had two limitations that should be addressed. First, the results of this study

only represented the participants’ experiences without attempting general findings so

these results might not be generalized to all EDs in Indonesia. However, some

participants had broad experiences of triage practice in many EDs throughout Indonesia.

Therefore, the findings were likely to describe the current triage system in EDs in

Indonesia. Second, a possible bias could be related to the participants as two thirds of

the participants were doctors. The results would possibly voice the doctor’s view.

However, it was very important that all participants’ insights are acknowledged and

reported.

CONCLUSION

In conclusion, four steps of triage process ranging from receiving to prioritizing were

reported as the triaging procedures in Indonesia which were almost similar to the

international literature except for a re-triage step. Primary and secondary triage

processes were also applied in all emergency departments in Indonesia. No prolonged

waiting time in Indonesia could be assumed whether the triage process was effective

and efficient or it was only a quick process of sorting to rapidly increase the number of

patients in the treatment rooms. Also, the involvement of nurses in health policy

development in Indonesia still needed support. Therefore, the study recommends

patient’s re-triage and evaluating secondary triage to be given more frameworks in the

Copyright © 2016, NMJN,p-ISSN 2087-7811, e-ISSN 2406-87

Nurse Media Journal of Nursing, 6 (1), 2016, 45

future, an effective and efficient triage process in Indonesia to best manage the number

of patients in the treatment rooms, further observational research on patterns and trends

of triage process, and to include the role of nurses as policy makers in the curriculum of

nursing undergraduate and post-graduate degrees.

REFERENCES

Augustyn, J. E., Ehlers, V. J., & Hattingh, S. P. (2009). Nurses' and doctors' perceptions

regarding the implementation of a triage system in an emergency unit in South

Africa.(Original Research)(Report). Health SA Gesondheid, 14(1), 104(108).

Brown, P. O., Higgins, J., Bridge, P., & Cooke, M. (2001). What does the triage nurse

do? Emergency Nurse, 8(10), 30.

Bruijns, S. R., Wallis, L. A., & Burch, V. C. (2008). Effect of introduction of nurse

triage on waiting times in a South African emergency department. Emergency

Medicine Journal, 25(7), 395-397. doi: 10.1136/emj.2007.049411

Chan, J. N. H., & Chau, J. (2005). Patient satisfaction with triage nursing care in Hong

Kong. Journal of Advanced Nursing, 50(5), 498-507. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-

2648.2005.03428.x

College of Emergency Nursing Australasia (CENA). (2007). Position Statement Triage

Nurse. Australasian Emergency Nursing Journal, 10(2), 93-95. doi:

10.1016/s1574-6267(07)00062-6

Cooper, R. J. (2004). Emergency department triage: Why we need a research agenda.

Annals of Emergency Medicine, 44(5), 524-526. doi:

10.1016/j.annemergmed.2004.07.432

Coughlan, M., & Corry, M. (2007). The experiences of patients and relatives/significant

others of overcrowding in accident and emergency in Ireland: A qualitative

descriptive study. Accident and Emergency Nursing, 15(4), 201-209. doi:

10.1016/j.aaen.2007.07.009

Cronin, J. G., & Wright, J. (2005). Rapid assessment and initial patient treatment team -

a way forward for emergency care. Accident and Emergency Nursing, 13(2), 87-

92. doi: 10.1016/j.aaen.2004.12.002

Department of Health and Ageing. (2007). Emergency triage education kit. Canberra:

Commonwealth of Australia.

FitzGerald, G., Jelinek, G. A., Scott, D., & Gerdtz, M. F. (2010). Emergency

department triage revisited. Emergency Medicine Journal, 27(2), 86-92. doi:

10.1136/emj.2009.077081

Funderburke, P. (2008). Exploring Best Practice for Triage. Journal of Emergency

Nursing, 34(2), 180-182. doi: 10.1016/j.jen.2007.11.013

Ganley, L., & Gloster, A. S. (2011). An overview of triage in the emergency

department.(Learning zone: emergency care). Nursing Standard, 26, 49(49).

Gerdtz, M. F., & Bucknall, T. K. (2001). Triage nurses’ clinical decision making. An

observational study of urgency assessment. Journal of Advanced Nursing, 35(4),

550-561. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2648.2001.01871.x

Gilboy, N., Tanabe, P., Travers, D., & Rosenau, A. M. (2011). Emergency Severity

Index (ESI): A Triage Tool for Emergency Department Care, Version 4,

Implementation Handbook 2012 Edition. Rockville: Agency for Healthcare

Research and Quality.

Copyright © 2016, NMJN,p-ISSN 2087-7811, e-ISSN 2406-87

Nurse Media Journal of Nursing, 6 (1), 2016, 46

Göransson, K. E., & von Rosen, A. (2010). Patient experience of the triage encounter in

a Swedish emergency department. International Emergency Nursing, 18(1), 36-

40. doi: 10.1016/j.ienj.2009.10.001

Lahdet, E. F., Suserud, B.-O., Jonsson, A., & Lundberg, L. (2009). Analysis of triage

worldwide. Emergency Nurse, 17(4), 16(14).

Lindley-Jones, M., & Finlayson, B. J. (2000a). Triage nurse requested x-ray: the results

of a national survey in UK. Journal of Accident & Emergency Medicine, 17(2),

108-110.

Lindley-Jones, M., & Finlayson, B. J. (2000b). Triage nurse requested x rays—are they

worthwhile? Journal of Accident & Emergency Medicine, 17(2), 103-107. doi:

10.1136/emj.17.2.103

Mackway-Jones, K., Marsden, J., & Windle, J. (Eds.). (2006). Emergency triage-

Manchester Triage Group (2 ed.). Oxford: Blackwell Publishing Ltd.

Minister of Health The Republic of Indonesia. (2009). The standard of emergency

departments in the hospitals. (856/Menkes/SK/IX/2009). Jakarta: Ministry of

Health The Republic of Indonesia.

Ministry of Health The Republic of Indonesia. (1999). Material of PPGD training

series: emergency care system and national policy (1 ed.). Jakarta: Ministry of

Health The Republic of Indonesia.

Nixon, V. (2008). Identification of the development needs for the emergency care

nursing workforce. International Emergency Nursing, 16(1), 14-22. doi:

10.1016/j.ienj.2007.10.001

Quattrini, V., & Swan, B. A. (2011). Evaluating Care in ED Fast Tracks. Journal of

Emergency Nursing, 37(1), 40-46. doi: 10.1016/j.jen.2009.10.016

Seiger, N., van Veen, M., Steyerberg, E. W., Ruige, M., van Meurs, A. H. J., & Moll, H.

A. (2011). Undertriage in the Manchester triage system: an assessment of

severity and options for improvement. Archives of Disease in Childhood, 96(7),

653-657. doi: 10.1136/adc.2010.206797

Shields, L., & Hartati, L. E. (2003). Nursing and health care in Indonesia. Journal of

Advanced Nursing, 44(2), 209.

Woolwich, C. (2000). Accident and emergency: theory into practice. London: Balliliere

Tindall.

Copyright © 2016, NMJN,p-ISSN 2087-7811, e-ISSN 2406-87

View publication stats

You might also like

- LP Fraktur HumerusDocument10 pagesLP Fraktur HumerusMutmin AnsariNo ratings yet

- Ni20162 PDFDocument6 pagesNi20162 PDFAb Staholic BoiiNo ratings yet

- Improving Nurse Knowledge and Attitudes of Early Mobilization ofDocument68 pagesImproving Nurse Knowledge and Attitudes of Early Mobilization ofMuhammad Alif AlfajriqoNo ratings yet

- New Microsoft Word DocumentDocument4 pagesNew Microsoft Word Documentmamita gurungNo ratings yet

- 2277-Article Text-7155-4-10-20200122Document15 pages2277-Article Text-7155-4-10-20200122fadil ahmadiNo ratings yet

- Intensive & Critical Care Nursing: Ziad Alostaz, Louise Rose, Sangeeta Mehta, Linda Johnston, Craig DaleDocument11 pagesIntensive & Critical Care Nursing: Ziad Alostaz, Louise Rose, Sangeeta Mehta, Linda Johnston, Craig DalecindyNo ratings yet

- Journal Homepage: - : Introduction:-Objectives of The StudyDocument4 pagesJournal Homepage: - : Introduction:-Objectives of The StudyIJAR JOURNALNo ratings yet

- Survey Questions For SESDocument101 pagesSurvey Questions For SESShayne FurogNo ratings yet

- Persepsi Dan Penerimaan Interprofessional Collaborative Practice Bidang Maternitas Pada Tenaga KesehatanDocument9 pagesPersepsi Dan Penerimaan Interprofessional Collaborative Practice Bidang Maternitas Pada Tenaga KesehatanLALU PRAYADENo ratings yet

- Operation Assessment On Ambulance Services: A Case Study of Machakos County, KenyaDocument13 pagesOperation Assessment On Ambulance Services: A Case Study of Machakos County, Kenyasiyabonga472No ratings yet

- Clinical Research Nursing: Scope and Standards of PracticeFrom EverandClinical Research Nursing: Scope and Standards of PracticeRating: 5 out of 5 stars5/5 (1)

- Eras Grand PDFDocument9 pagesEras Grand PDFWiwit ClimberNo ratings yet

- EBP in Nursing: Research Roles and ResponsibilitiesDocument11 pagesEBP in Nursing: Research Roles and ResponsibilitiesGlen DaleNo ratings yet

- Advancing Your Practice Through Evidence of Success 1. Contact InformationDocument4 pagesAdvancing Your Practice Through Evidence of Success 1. Contact InformationrbtakemotoNo ratings yet

- Ito Et Al-2012-Pediatrics InternationalDocument19 pagesIto Et Al-2012-Pediatrics Internationalakhmad alya maulanaNo ratings yet

- What Makes Continuing Education Effective PerspectDocument6 pagesWhat Makes Continuing Education Effective PerspecttestNo ratings yet

- Nitrous Oxide in Pediatric Dentistry: A Clinical HandbookFrom EverandNitrous Oxide in Pediatric Dentistry: A Clinical HandbookKunal GuptaNo ratings yet

- IJET2 Comparison TelemedicineDocument11 pagesIJET2 Comparison TelemedicineAndi MarsaliNo ratings yet

- Research: Interpreting AccountabilityDocument76 pagesResearch: Interpreting AccountabilitySubin AugustineNo ratings yet

- The Nursing and Midwifery Content Audit Tool NMCATDocument15 pagesThe Nursing and Midwifery Content Audit Tool NMCATDan kibet TumboNo ratings yet

- Capability Beliefs On, and Use of Evidence-Based Practice Among Four Health Professional and Student Groups in Geriatric Care: A Cross Sectional StudyDocument16 pagesCapability Beliefs On, and Use of Evidence-Based Practice Among Four Health Professional and Student Groups in Geriatric Care: A Cross Sectional StudynofitaNo ratings yet

- Pioneer Nursing College Vadodara Annotated BibliographiesDocument7 pagesPioneer Nursing College Vadodara Annotated BibliographiesKinjalNo ratings yet

- Evidence-Based Practice and Nursing ResearchDocument24 pagesEvidence-Based Practice and Nursing ResearchMelody B. Miguel75% (4)

- TheProfessionalNurseSelf AssessmentScaleDocument14 pagesTheProfessionalNurseSelf AssessmentScaleNabeeha Fazeel100% (1)

- Priorities of Nursing ResearchDocument37 pagesPriorities of Nursing ResearchJisna AlbyNo ratings yet

- Assignment in Research, LagradaDocument2 pagesAssignment in Research, LagradaCate LagradaNo ratings yet

- Jayson NovellesDocument38 pagesJayson Novellesaronara dalampasiganNo ratings yet

- The Benefits of Nurse Prescribing Within Specialist Palliative CareDocument26 pagesThe Benefits of Nurse Prescribing Within Specialist Palliative CarejakkenjuNo ratings yet

- Nursing Research Challenges and OpportunitiesDocument27 pagesNursing Research Challenges and Opportunitiessara mohamedNo ratings yet

- Research Powerpoint by GilDocument34 pagesResearch Powerpoint by GilgilpogsNo ratings yet

- Factors Affecting The Delivery of Care As Experienced by Nurses in Selected Hospitals in Isabela, PhilippinesDocument11 pagesFactors Affecting The Delivery of Care As Experienced by Nurses in Selected Hospitals in Isabela, PhilippinesInternational Journal of Innovative Science and Research TechnologyNo ratings yet

- ResearchDocument36 pagesResearchHarshini BaskaranNo ratings yet

- Woman-Centred Care in Childbirth: A Concept Analysis (Part 1)Document9 pagesWoman-Centred Care in Childbirth: A Concept Analysis (Part 1)lilahgreenyNo ratings yet

- Triangulation in Research With ExamplesDocument3 pagesTriangulation in Research With Exampleslive roseNo ratings yet

- NRSG 7200 EmilyharamesdnpprojectpaperDocument14 pagesNRSG 7200 Emilyharamesdnpprojectpaperapi-582004140No ratings yet

- Self-Leadership in A Critical Care Outreach Service For Quality Patient CareDocument19 pagesSelf-Leadership in A Critical Care Outreach Service For Quality Patient CareKamila AmmarNo ratings yet

- Critical Thinking, Research Utilization and Barriers To This Among Nursing Students in Scandinavia and IndonesiaDocument10 pagesCritical Thinking, Research Utilization and Barriers To This Among Nursing Students in Scandinavia and IndonesiaVara Al kautsarinaNo ratings yet

- Impact of Nursing Diagnoses On Patient and Organisational Outcomes: A Systematic Literature ReviewDocument43 pagesImpact of Nursing Diagnoses On Patient and Organisational Outcomes: A Systematic Literature ReviewLucas Teles IanniNo ratings yet

- Capinding Et Al. Group 1edited DOCSSXDocument88 pagesCapinding Et Al. Group 1edited DOCSSXMargarita Limon BalunesNo ratings yet

- Think-Aloud Technique and Protocol Analysis in Clinical Decision-Making ResearchDocument11 pagesThink-Aloud Technique and Protocol Analysis in Clinical Decision-Making ResearchAyoub MandriNo ratings yet

- Effectivenes of Mentoring Program To Improving Attitude of Pasien SafetyDocument4 pagesEffectivenes of Mentoring Program To Improving Attitude of Pasien SafetyInternational Journal of Innovative Science and Research TechnologyNo ratings yet

- Innovativejournal,+Journal+Manager,+OVERVIEW of NURSING RESEARCHDocument9 pagesInnovativejournal,+Journal+Manager,+OVERVIEW of NURSING RESEARCHEmmanuela AzubugwuNo ratings yet

- Perceptions of Nursing: A Study Involving Nurses, Nursing Students, Patients and Non-Nursing StudentsDocument12 pagesPerceptions of Nursing: A Study Involving Nurses, Nursing Students, Patients and Non-Nursing StudentsErditha MirandaNo ratings yet

- Mhealth: Technology For Nursing Practice, Education, and ResearchDocument12 pagesMhealth: Technology For Nursing Practice, Education, and ResearchNandhini ShreeNo ratings yet

- The Views of Health Workforce Managers On The ImplDocument12 pagesThe Views of Health Workforce Managers On The ImplOUEDRAOGO AlainNo ratings yet

- Individu AzaDocument5 pagesIndividu AzaZachya IslamiaNo ratings yet

- Ambo University College of Health Sciences and Medicine Department of Nursing and MidwiferyDocument33 pagesAmbo University College of Health Sciences and Medicine Department of Nursing and MidwiferyCurios cornerNo ratings yet

- The Factors Affecting The Medication Administration Delivery Times of Nurses in A Tertiary Government Hospital in Cabanatuan CityDocument18 pagesThe Factors Affecting The Medication Administration Delivery Times of Nurses in A Tertiary Government Hospital in Cabanatuan CityCalegan EddieNo ratings yet

- Advanced practice roles in ophthalmic nursing: A comparison of the UK and New ZealandDocument13 pagesAdvanced practice roles in ophthalmic nursing: A comparison of the UK and New ZealandShruthi VMNo ratings yet

- Trends PaperDocument8 pagesTrends PaperLina ProanoNo ratings yet

- Medication Incompatibility in Intravenous Lines in A Paediatric Intensive Care Unit (PICU) of Indonesian Hospital (Kel.8)Document11 pagesMedication Incompatibility in Intravenous Lines in A Paediatric Intensive Care Unit (PICU) of Indonesian Hospital (Kel.8)Rotama GurningNo ratings yet

- Andre, 2016. Embedding Evidence-Based Practice Among Nursing UndergraduatesDocument6 pagesAndre, 2016. Embedding Evidence-Based Practice Among Nursing UndergraduatesLina MarcelaNo ratings yet

- Crozier Et Al INMPP 2012Document10 pagesCrozier Et Al INMPP 2012shejila c hNo ratings yet

- What Is A Clinical Pathway? Development of A Definition To Inform The DebateDocument4 pagesWhat Is A Clinical Pathway? Development of A Definition To Inform The DebateRSIA MOELIANo ratings yet

- Exploring Islamic Based Caring Practice in Intensive Care Unit: A Qualitative StudyDocument10 pagesExploring Islamic Based Caring Practice in Intensive Care Unit: A Qualitative StudyineNo ratings yet

- International Journal of GerontologyDocument5 pagesInternational Journal of GerontologyPurwoko SugengNo ratings yet

- 379 Reflection EssayDocument4 pages379 Reflection Essayapi-639787616No ratings yet

- ICU tracheostomy care assessmentDocument7 pagesICU tracheostomy care assessmentmochkurniawanNo ratings yet

- About 70 % of Medical Error Are Related To Interpersonal Interaction Issues andDocument4 pagesAbout 70 % of Medical Error Are Related To Interpersonal Interaction Issues andIntanPermataSyariNo ratings yet

- Authorized Sentce Station Service Marine Safety Supplier: Survey And丁Es丁ReportDocument5 pagesAuthorized Sentce Station Service Marine Safety Supplier: Survey And丁Es丁ReportIntanPermataSyariNo ratings yet

- GBR Ilr SBLMDocument5 pagesGBR Ilr SBLMIntanPermataSyariNo ratings yet

- Hospital Marketing Strategy Using MBMDocument23 pagesHospital Marketing Strategy Using MBMEldie RahimNo ratings yet

- Patient Triage System For Supporting BMC MedicalDocument16 pagesPatient Triage System For Supporting BMC MedicalIntanPermataSyariNo ratings yet

- Effectiveness of The Manchester Triage System On TimeDocument10 pagesEffectiveness of The Manchester Triage System On TimeIntanPermataSyariNo ratings yet

- A Review of Triage Accuracy and FutureDocument7 pagesA Review of Triage Accuracy and FutureJoséRafaelArmasNo ratings yet

- TJEM - Factors Affecting The Accuracy of Nurse Triage in Tertiary Care E.RDocument5 pagesTJEM - Factors Affecting The Accuracy of Nurse Triage in Tertiary Care E.RIntanPermataSyariNo ratings yet

- TJEM - Factors Affecting The Accuracy of Nurse Triage in Tertiary Care E.RDocument5 pagesTJEM - Factors Affecting The Accuracy of Nurse Triage in Tertiary Care E.RIntanPermataSyariNo ratings yet

- 1 SMDocument5 pages1 SMIntanPermataSyariNo ratings yet

- Home Visits A Primer 2012 SilkDocument56 pagesHome Visits A Primer 2012 SilkIntanPermataSyariNo ratings yet

- Alodokter Test: Medical CasesDocument7 pagesAlodokter Test: Medical CasesIntanPermataSyariNo ratings yet

- CPD Inggris 2Document3 pagesCPD Inggris 2IntanPermataSyariNo ratings yet

- SENDY WOWOR 091511070 Akk PDFDocument5 pagesSENDY WOWOR 091511070 Akk PDFIntanPermataSyariNo ratings yet

- Damage Control Orthopaedics PDFDocument6 pagesDamage Control Orthopaedics PDFRakesh KumarNo ratings yet

- Phs Mammographer PresentationDocument10 pagesPhs Mammographer Presentationapi-546893338No ratings yet

- BOLT StudyDocument11 pagesBOLT Studytiago_nelson100% (1)

- Larsen, J.K. (2017)Document8 pagesLarsen, J.K. (2017)Ale ValenciaNo ratings yet

- Tagore Hospital Quality PlanDocument16 pagesTagore Hospital Quality PlanPrabhat Kumar100% (1)

- Juvenile Idiopathic Arthritis TypesDocument1 pageJuvenile Idiopathic Arthritis TypesDinesh ReddyNo ratings yet

- Clinical Review of 24 - 35 Year Olds Conceived With and Without in Vitro Fertilization: Study ProtocolDocument8 pagesClinical Review of 24 - 35 Year Olds Conceived With and Without in Vitro Fertilization: Study ProtocolUmanyan ArtiomNo ratings yet

- Drug AddictionDocument7 pagesDrug AddictionZechariah NicholasNo ratings yet

- Or FormsDocument7 pagesOr FormsJose BernelNo ratings yet

- Laryngeal MassageDocument6 pagesLaryngeal Massageamal100% (1)

- Medical Examiner's HandbookDocument221 pagesMedical Examiner's HandbookMarina SwansonNo ratings yet

- Abrupta Placenta - 4 Pt presents with vaginal bleeding, ABDOMINAL PAIN, and uterine tendernessDocument211 pagesAbrupta Placenta - 4 Pt presents with vaginal bleeding, ABDOMINAL PAIN, and uterine tendernessroad2successNo ratings yet

- Gallbladder and Pancrease PathologyDocument4 pagesGallbladder and Pancrease Pathologyjohn smithNo ratings yet

- Case Files Family MedicineDocument19 pagesCase Files Family MedicineAztecNo ratings yet

- Hauber 2019Document10 pagesHauber 2019Laura HdaNo ratings yet

- Activity For Day 2Document4 pagesActivity For Day 2Catherine MerillenoNo ratings yet

- Information For Patients Having A CT Scan: Oxford University HospitalsDocument8 pagesInformation For Patients Having A CT Scan: Oxford University HospitalsAmirNo ratings yet

- Glomerular Disease - Dr. LuDocument8 pagesGlomerular Disease - Dr. LuMACATANGAY, GAELLE LISETTENo ratings yet

- PEDIATRIC NURSING POST TEST REVIEWDocument26 pagesPEDIATRIC NURSING POST TEST REVIEWTrisha ArizalaNo ratings yet

- Bibliografiaactualizada de Ecografia y RadiologíaDocument2 pagesBibliografiaactualizada de Ecografia y RadiologíaKimberly NicoleNo ratings yet

- Sirenomelia: A Case Report of A Rare Congenital Anamaly and Review of LiteratureDocument3 pagesSirenomelia: A Case Report of A Rare Congenital Anamaly and Review of LiteratureInt Journal of Recent Surgical and Medical SciNo ratings yet

- Pericardial Disease EscDocument44 pagesPericardial Disease EscMelati SatriasNo ratings yet

- Long-Term Surgery Graves Disease 20 YearsDocument3 pagesLong-Term Surgery Graves Disease 20 YearsTambunta TariganNo ratings yet

- Neuropsychology of Bipolar DisorderDocument9 pagesNeuropsychology of Bipolar DisorderwulanfarichahNo ratings yet

- Management of Hypertension: Clinical Practice GuidelinesDocument31 pagesManagement of Hypertension: Clinical Practice GuidelinesKokoland KukusNo ratings yet

- Stupor and Coma in Adults - UpToDateDocument46 pagesStupor and Coma in Adults - UpToDatemgvbNo ratings yet

- Professional Nursing PracticeDocument7 pagesProfessional Nursing PracticePrince K. TaileyNo ratings yet

- Insulin AdministrationDocument9 pagesInsulin AdministrationMonika JosephNo ratings yet

- 1991 Bromberger Fife-Yeomans Deep Sleep Harry Bailey and The Scandal of ChelmsfordDocument202 pages1991 Bromberger Fife-Yeomans Deep Sleep Harry Bailey and The Scandal of ChelmsfordKevin McInnes100% (1)

- PalpitationsDocument3 pagesPalpitationsJessica Febrina WuisanNo ratings yet