Professional Documents

Culture Documents

MacLean (2015) Tribal Modern - Branding New Nations in The Arab Gulf (Review)

Uploaded by

Philip BeardOriginal Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

MacLean (2015) Tribal Modern - Branding New Nations in The Arab Gulf (Review)

Uploaded by

Philip BeardCopyright:

Available Formats

Review

Reviewed Work(s): TRIBAL MODERN: BRANDING NEW NATIONS IN THE ARAB GULF by

miriam cooke

Review by: Matthew MacLean

Source: The Arab Studies Journal , Fall 2015, Vol. 23, No. 1 (Fall 2015), pp. 423-427

Published by: Arab Studies Institute

Stable URL: https://www.jstor.org/stable/44744924

JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide

range of content in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and

facilitate new forms of scholarship. For more information about JSTOR, please contact support@jstor.org.

Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of the Terms & Conditions of Use, available at

https://about.jstor.org/terms

Arab Studies Institute is collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve and extend access to

The Arab Studies Journal

This content downloaded from

161.6.94.193 on Mon, 18 Jan 2021 14:48:40 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

TRIBAL MODERN:

BRANDING NEW NATIONS IN THE ARAB GULF

miriamcooke

Berkeley: University of California Press, 2014

(214 pages, notes, references, index) $25.65 (paper)

Reviewed by Matthew MacLean

Tribal Modern: Branding New Nations in the Arab Gulf is the latest of a

growing body of work seeking to explain the rapid transformations of Arab

Gulf states and their emergence as regional and global actors over the past

decade. This scholarship has been dominated by historical studies drawing

on the British archives, state-centric studies of political legitimation, rentier-

state theory, and more recent work in urban studies and spatial theory. In

a departure from these trends, miriam cooke locates Gulf Arab modernity

not in material transformation but in cultural production. As a study of

contemporary Gulf Arab art, literature, and poetry, Tribal Modern is a

welcome addition to an expanding field. It also stands out as a work focused

on Qatar, the least studied of the Gulf states, where cooke did much of the

fieldwork on which the book is based.

At its outset, Tribal Modern argues against the equation of the tribal

with the primitive and non-Western, exemplified by the debate over a 1980s

MoMA exhibit titled "Primitivism in Modern Art," which juxtaposed

Western modernist and "tribal" non-Western works of art. Even critics of

Matthew MacLean is a PhD student in the Departments of History and Middle

Eastern and Islamic Studies at NYU

and a Humanities Research Fellow at NYU Abu Dhabi.

423

This content downloaded from

161.6.94.193 on Mon, 18 Jan 2021 14:48:40 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

the exhibition's binary premise, she notes, reproduced the binaries of West/

other and tribal/modern. More commonly, cooke criticizes the tendency of

Gulf observers and expatriates to assume that Gulf Arabs must constantly

negotiate contradictory demands of tradition and modernity. Instead, she

argues, the tribal and modern are mutually constitutive and lived simultane-

ously. Here cooke employs the Quranic term barzakhy variously described

as signifying "undiluted convergence" (10), "the simultaneous process of

mixing and separation," (13), and a liminal "metaphysical space between

life and the hereafter and also the physical space between sweet and salt

water" (71). This last definition, drawn from the Quran, probably describes

the Gulf near Bahrain, where pearl divers found freshwater springs on the

Gulf floor, and salt and fresh waters mingled. Cooke's interpretation of the

barzakh is less literal; she wants the reader to think of Gulf Arab societies

as inhabiting a barzakh space where the tribal and modern converge but

remain undiluted. This barzakh forms the core of the national "brands"

that Gulf states employ to legitimize themselves in the eyes of foreigners

and citizens alike. In this way, the barzakh and the "tribal modern" are one

way to get past the tradition/modernity binary that still characterize much

of the scholarly and popular debate on Gulf societies.

Cooke begins the book with a description of the Gulf's cosmopolitan

pre-oil past, in which it was a critical node in Western Indian Ocean com-

mercial networks and a borderless, stateless center of the world's pearling

industry. The marginalizing of this polyglot world in contemporary Gulf

memory is the necessary precondition for the emergence of cooke's "tribal

modern." The decline of pearling, the rise of oil, and the subsequent spec-

tacular transformations of Gulf cities led to a massive influx of foreign

workers and new forms of cultural and economic exclusion. The emergence

of states meant that citizens began to identify themselves along national

lines, in the process downplaying or denying the cosmopolitan heritage of

the recent past. New discourses of local rootedness and cultural authen-

ticity-exemplified, in cooke's analysis, by Abdelrahman Munif 's Cities of

Salty which was long banned in Gulf countries- justify citizens' claims to

oil-generated wealth distributed by the state.

Chapters two through four analyze the nexus between tribe and

nation as categories of belonging among Gulf Arabs, and how they have

become racialized through genetic research on tribal origins. The tribe and

424

This content downloaded from

161.6.94.193 on Mon, 18 Jan 2021 14:48:40 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

Tribal Modem

nation exist in tension with each other, as cooke explores through her study

of marriage practices. Gulf Arabs, like many people from various regions,

seek to marry spouses of similar social status; membership in a prestig-

ious tribe and citizenship in Gulf Cooperation Council nations are both

forms of social capital, which cooke illustrates with many entertaining and

informative anecdotes from her fieldwork in Qatar. Many extended families

spread across two or more Gulf states. But institutions like the United Arab

Emirates' marriage fund, which gives cash grants to Emirati nationals who

marry each other, challenge prenational and subnational tribal networks by

privileging national over tribal affiliation. Indeed, members of tribes with

transnational affiliations, such as the Qatar i- Saudi al-Murra, found their

citizenship temporarily revoked in the mid-2000s. However, tribal identities

are also reworked and performed to demonstrate allegiance to the nation

and ruling family, as when members of the Dukhan Camel Club in western

Qatar rode into Doha to congratulate the emir when Qatar was awarded the

2022 FIFA World Cup. Tribal identity and status- supposedly bolstered by

genetic research to provide scientific proof of lineage- become a substitute

for class among Qatari citizens. Gulf Arabs' discourse of "authenticity,"

which cooke compares to mid-twentieth-century Arab anticolonial rhetoric,

further undergirds their claims to tribal and national belonging and thus

also access to wealth. Here cooke critically analyzes Gulf Arabs' invention

of authenticity while also taking their use of the term seriously.

The strongest section of Tribal Modern is the discussion of museums,

architecture, and heritage in chapters five through seven. Cooke focuses on

the work of Qatari architect Muhammad Ali, who used pre-oil vernacular

forms to construct his own modern home and was also the mastermind

of the rebuilding of Suq Waqif in central Doha. Muhammad Ali based

his work on commercial records dating back to the late 1800s describing

the location of different sections in the market, their relation to the kharis

(flood channel), and the market's critical role in relations between bedouin

and the city. While not intended as a restoration of the "authentic" pre-oil

past, the new Suq Waqif was praised and criticized for being just that. By

contrast, cooke argues that Muhammad Ali succeeded in creating an urban

space used both by Qataris and expatriates that is reminiscent enough of

the past to lessen Qataris' nostalgia for what has been lost in their nation's

rapid transformation. This simulacrum, like the Qatar National Museum

425

This content downloaded from

161.6.94.193 on Mon, 18 Jan 2021 14:48:40 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

and the Zayed National Museum in Abu Dhabi (both designed by foreigners),

is a fine example of cooke s barzakh theory.

Using orientalist art and Gulf Arab literature, poetry, and film, cooke

proceeds to explain the development over the past few decades of a deep

nostalgia for the pre-oil past and the emergence of a variety of "invented

traditions" and simulacra, including camel racing, pearl- diving classes,

and televised poetry competitions. Urban cores largely abandoned by Gulf

Arabs have been revitalized as heritage districts, a phenomenon cooke

smartly links to global gentrification. In these simulacra of the tribal past

and the modern, the pre-oil era is imagined as a time of social virtue and

close-knit communities; hardship and injustice are for the most part down-

played, though cooke is careful to include the counter-examples of a 1970s

Kuwaiti film and more recent Emirati poetry criticizing the injustices of

the pearling industry. The barzakh "tribal modern" theme emerges again

in her extended description of the Abu Dhabi-sponsored reality TV show

"Millions Poet," a competitive recitation of Nabati poetry. Building on her

earlier discussion of national dress, the final chapter analyzes challenges

to contemporary gender expectations posed by women's education and the

emergence of queer sexualities. Cooke's discussion of coldness as a trope

that Gulf Arab women's literature uses to represent technology and social

alienation is also particularly insightful.

The book's largest problem is the repeated slippage between national

and regional scales. Though Gulf nations cannot be studied in isolation,

Tribal Modern moves too far in the other direction. The strongest vignettes

are those related to Qatar, but the Qatari experience cannot automatically

be generalized to the rest of the Gulf. Though drawing on examples from all

the Gulf states except for Oman in explaining the concept of "tribal modern,"

the book's analysis would have been stronger if more attention had been

paid to variations between and within Gulf states. There are also a number

of factual errors in the text. Not all Gulf Arabs identify as tribal, and cooke's

use of the term as a catch-all phrase for everything that is associated with

the past is perhaps too broad. Unlike Indians in the colonial era, Gulf Arabs

were not British subjects, but subjects of whatever shaykh they recognized

(33). The National is a newspaper based in Abu Dhabi, not Saudi Arabia

(140), and the UAE currency is the dirham, not the dinar (131). Bastakia

district in Dubai was revitalized not by Iranians (though originally settled

426

This content downloaded from

161.6.94.193 on Mon, 18 Jan 2021 14:48:40 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

Tribal Modem

by Arabs migrating from Iran) but by Dubai Municipality (101). These errors

will undoubtedly raise the hackles of Gulf specialists, but do not detract

from the larger argument or cookes creative use of the barzakh as a way to

explain what is often perceived as a contradiction.

Tribal Modern is largely jargon-free and quite easy to read, and thus

is accessible to a wide audience. The book should be read by Gulf specialists

for its focus on cultural production, which will hopefully stimulate further

research along these lines, and by others seeking an introduction to and

survey of contemporary Gulf societies and culture.

427

This content downloaded from

161.6.94.193 on Mon, 18 Jan 2021 14:48:40 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

You might also like

- Croxton, D. (1999) - The Peace of Westphalia of 1648 and The Origins of SovereigntyDocument24 pagesCroxton, D. (1999) - The Peace of Westphalia of 1648 and The Origins of SovereigntyPhilip BeardNo ratings yet

- Daly 1990Document20 pagesDaly 1990mjacquinet100% (1)

- Croxton, D. (1999) - The Peace of Westphalia of 1648 and The Origins of SovereigntyDocument24 pagesCroxton, D. (1999) - The Peace of Westphalia of 1648 and The Origins of SovereigntyPhilip BeardNo ratings yet

- Bratianu, C. (2020) - Toward Understanding The Complexity of The COVID-19 Crisis - A Grounded Theory Approach. Management & Marketing, 15, 410-423.Document15 pagesBratianu, C. (2020) - Toward Understanding The Complexity of The COVID-19 Crisis - A Grounded Theory Approach. Management & Marketing, 15, 410-423.Philip BeardNo ratings yet

- Qualitative Accounting Research: An Account of Glaser's Grounded TheoryDocument20 pagesQualitative Accounting Research: An Account of Glaser's Grounded TheoryPhilip BeardNo ratings yet

- Qualitative Research: 2004 4: 247 Joy D. Bringer, Lynne H. Johnston and Celia H. BrackenridgeDocument20 pagesQualitative Research: 2004 4: 247 Joy D. Bringer, Lynne H. Johnston and Celia H. BrackenridgePhilip BeardNo ratings yet

- Understanding and Resolving Major Contractual Breaches in Buyer - Seller Relationships: A Grounded Theory ApproachDocument21 pagesUnderstanding and Resolving Major Contractual Breaches in Buyer - Seller Relationships: A Grounded Theory ApproachPhilip BeardNo ratings yet

- Moral Stress in International Humanitarian Aid and Rescue Operations: A Grounded Theory StudyDocument21 pagesMoral Stress in International Humanitarian Aid and Rescue Operations: A Grounded Theory StudyPhilip BeardNo ratings yet

- Vogel (2018) The Confessions of Quentin Tarantino - Whitewashing Slave Rebellion in Django UnchainedDocument11 pagesVogel (2018) The Confessions of Quentin Tarantino - Whitewashing Slave Rebellion in Django UnchainedPhilip BeardNo ratings yet

- Stillbirth Registration and Perceptions of Infant Death, 1900-60: The Scottish Case in National ContextDocument26 pagesStillbirth Registration and Perceptions of Infant Death, 1900-60: The Scottish Case in National ContextPhilip BeardNo ratings yet

- Persistent Inaccuracies in Completion of Medical Certificates of Stillbirth: A Cross-Sectional StudyDocument8 pagesPersistent Inaccuracies in Completion of Medical Certificates of Stillbirth: A Cross-Sectional StudyPhilip BeardNo ratings yet

- Are UN and US Economic Sanctions A Cause or Cure For The Environment: Empirical Evidence From IranDocument19 pagesAre UN and US Economic Sanctions A Cause or Cure For The Environment: Empirical Evidence From IranPhilip BeardNo ratings yet

- Gubar (2006) RACIAL CAMP in The Producers and BamboozledDocument12 pagesGubar (2006) RACIAL CAMP in The Producers and BamboozledPhilip BeardNo ratings yet

- Doughty (2017) The Buppie and Authentic BlacknessDocument17 pagesDoughty (2017) The Buppie and Authentic BlacknessPhilip BeardNo ratings yet

- Turim (2016) Experimental Women FilmakersDocument10 pagesTurim (2016) Experimental Women FilmakersPhilip BeardNo ratings yet

- Alissa (2013) The Oil Town of Ahmadi Since 1946 - From Colonial Town To Nostalgic CityDocument19 pagesAlissa (2013) The Oil Town of Ahmadi Since 1946 - From Colonial Town To Nostalgic CityPhilip BeardNo ratings yet

- Ruoff (2011) - The Gulf War, The Iraq War, and Nouri Bouzid's Cinema of Defeat - "It's Scheherazade We're Killing (1993) " and "Making of (2006)Document19 pagesRuoff (2011) - The Gulf War, The Iraq War, and Nouri Bouzid's Cinema of Defeat - "It's Scheherazade We're Killing (1993) " and "Making of (2006)Philip BeardNo ratings yet

- Palis (2018) The Economics and Politics of Auteurism - Spike Lee and Do The Right ThingDocument22 pagesPalis (2018) The Economics and Politics of Auteurism - Spike Lee and Do The Right ThingPhilip BeardNo ratings yet

- Berg (2006) A Taxonomy of Alternative Plots in Recent Films - Classifying The "Tarantino EffectDocument58 pagesBerg (2006) A Taxonomy of Alternative Plots in Recent Films - Classifying The "Tarantino EffectPhilip BeardNo ratings yet

- MacLean (2015) Tribal Modern - Branding New Nations in The Arab Gulf (Review)Document6 pagesMacLean (2015) Tribal Modern - Branding New Nations in The Arab Gulf (Review)Philip BeardNo ratings yet

- Reconsidering Culture, Attachment, and Inequality in The Treatment of A Puerto Rican Migrant: Toward Structural Competence in PsychotherapyDocument13 pagesReconsidering Culture, Attachment, and Inequality in The Treatment of A Puerto Rican Migrant: Toward Structural Competence in PsychotherapyPhilip BeardNo ratings yet

- El-Hibri (2017) Media Studies, The Spatial Turn, and The Middle EastDocument26 pagesEl-Hibri (2017) Media Studies, The Spatial Turn, and The Middle EastPhilip BeardNo ratings yet

- Social Media and Public Polarization Over Climate ChangeDocument10 pagesSocial Media and Public Polarization Over Climate ChangeajiebonkraharjoNo ratings yet

- Daily Mindful Responding Mediates The Effect of Meditation Practice On Stress and Mood: The Role of Practice Duration and AdherenceDocument15 pagesDaily Mindful Responding Mediates The Effect of Meditation Practice On Stress and Mood: The Role of Practice Duration and AdherencePhilip BeardNo ratings yet

- Martins Et Al. (2019) Engaging With The Affiliative System Through Mindfulness - The Impact of The Different Types of Positive Affect in PsychosisDocument13 pagesMartins Et Al. (2019) Engaging With The Affiliative System Through Mindfulness - The Impact of The Different Types of Positive Affect in PsychosisPhilip BeardNo ratings yet

- Thaker (2019) Perceived Collective Efficacy and Trust in Government Influence Public Engagement With Climate Change-RelatedDocument20 pagesThaker (2019) Perceived Collective Efficacy and Trust in Government Influence Public Engagement With Climate Change-RelatedPhilip BeardNo ratings yet

- Hronis Et Al. (2019) Fearless Me!© - A Feasibility Case Series of Cognitive Behavioral Therapy For Adolescents With Intellectual DisabilityDocument15 pagesHronis Et Al. (2019) Fearless Me!© - A Feasibility Case Series of Cognitive Behavioral Therapy For Adolescents With Intellectual DisabilityPhilip BeardNo ratings yet

- Forand Et Al. (2019) Guided Internet CBT Versus "Gold Standard" Depression Treatments - An Individual Patient AnalysisDocument14 pagesForand Et Al. (2019) Guided Internet CBT Versus "Gold Standard" Depression Treatments - An Individual Patient AnalysisPhilip BeardNo ratings yet

- Balanzategui (2017) The Babadook and The Haunted Space Between High and Low Genres in The Australian Horror TraditionDocument16 pagesBalanzategui (2017) The Babadook and The Haunted Space Between High and Low Genres in The Australian Horror TraditionPhilip BeardNo ratings yet

- Buerger (2017) The Beak That Grips - Maternal Indifference, Ambivalence and The Abject in The BabadookDocument13 pagesBuerger (2017) The Beak That Grips - Maternal Indifference, Ambivalence and The Abject in The BabadookPhilip BeardNo ratings yet

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeFrom EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (5794)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingFrom EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (400)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeFrom EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (537)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceFrom EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (895)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)From EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Rating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (98)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerFrom EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (271)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryFrom EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (231)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItFrom EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (838)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceFrom EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (588)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealFrom EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (74)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureFrom EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (474)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaFrom EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (266)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaFrom EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (45)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnFrom EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (234)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyFrom EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (2259)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreFrom EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (1090)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersFrom EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (344)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)From EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Rating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (121)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesFrom EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (821)

- Daniel J. Sahas - Byzantium and Islam Collected Studies On Byzantine-Muslim Encounters-Brill (2021) PDFDocument550 pagesDaniel J. Sahas - Byzantium and Islam Collected Studies On Byzantine-Muslim Encounters-Brill (2021) PDFKA Nenov100% (3)

- Islamic Perspectives On LeadershipDocument15 pagesIslamic Perspectives On LeadershipKasimRanderee100% (1)

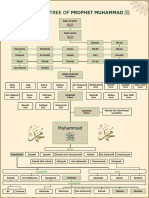

- Family Tree of Prophet MuhammadDocument1 pageFamily Tree of Prophet Muhammadgoogle pro100% (6)

- Silsilah Keturunan Sebagian Manusia Dimuka Bumi Haji MasnunDocument9 pagesSilsilah Keturunan Sebagian Manusia Dimuka Bumi Haji MasnunToko PrintNo ratings yet

- Traces of IranDocument40 pagesTraces of Iranmtajar0% (1)

- Jonathan Owens - Handbook of Arabic Linguistics PDFDocument540 pagesJonathan Owens - Handbook of Arabic Linguistics PDFMahmad Fatih100% (2)

- ISO 3-Digit Alpha Country Code Code ValueDocument5 pagesISO 3-Digit Alpha Country Code Code ValuesatishkhkhNo ratings yet

- IN GOD'S PATH NewDocument330 pagesIN GOD'S PATH NewSharifUddinNo ratings yet

- Khadijah Binti KhuwailidDocument4 pagesKhadijah Binti KhuwailidBursa Kerja KhususNo ratings yet

- MafraqDocument54 pagesMafraqفوزية حمدانNo ratings yet

- Early Islam A Critical Reconstruction Based On Contemporary Sources by Karl-Heinz Ohlig PDFDocument654 pagesEarly Islam A Critical Reconstruction Based On Contemporary Sources by Karl-Heinz Ohlig PDFlansel347807175% (4)

- Maulana Maududi Vitals of FaithDocument26 pagesMaulana Maududi Vitals of FaithThe Time Traveler (1989-....)100% (1)

- Foreign Policy Stance of Pakistan With Middle EastDocument8 pagesForeign Policy Stance of Pakistan With Middle EastEsha JavedNo ratings yet

- HIS 250 - Week Eleven AssignmentDocument2 pagesHIS 250 - Week Eleven AssignmentSamuelNo ratings yet

- 09 Arab LeagueDocument2 pages09 Arab LeagueMy BusinessNo ratings yet

- 227-237 - Shahîd - Arab Christianity in Byzantine PalestineDocument11 pages227-237 - Shahîd - Arab Christianity in Byzantine PalestineArcadie BodaleNo ratings yet

- Etablissements Publics CollegialDocument240 pagesEtablissements Publics CollegialYassir El yazidiNo ratings yet

- Template Nilai Harian-XII - AGAMA.I-Bahasa IndonesiaDocument90 pagesTemplate Nilai Harian-XII - AGAMA.I-Bahasa IndonesiaAnang Danik AlsyahNo ratings yet

- The Barbarous Voice of Democracy: American Captivity in Barbary and The Multicultural SpecterDocument27 pagesThe Barbarous Voice of Democracy: American Captivity in Barbary and The Multicultural SpecterMohamed BenzidanNo ratings yet

- Lebanon CulturegramDocument16 pagesLebanon Culturegramduca166No ratings yet

- Tawfeeq Al Hakim and His Contemporary DramatistsDocument23 pagesTawfeeq Al Hakim and His Contemporary DramatistsDr showkat ahmed shahNo ratings yet

- Airports OperabiltyDocument21 pagesAirports OperabiltyRough IDNo ratings yet

- History of Translation in IslamDocument24 pagesHistory of Translation in IslamKufaku GrixNo ratings yet

- The Contributions of Arabs, Chinese and Hindu in Development of Science and TechnologyDocument24 pagesThe Contributions of Arabs, Chinese and Hindu in Development of Science and TechnologyCastro Lalyska D.No ratings yet

- The 100 - A Ranking of The Most Influential Persons in History - Michael H. Hart (Excrept With Deedat's Forword)Document9 pagesThe 100 - A Ranking of The Most Influential Persons in History - Michael H. Hart (Excrept With Deedat's Forword)Waqas Murtaza50% (2)

- Scattergories Training: CountriesDocument25 pagesScattergories Training: Countriesscribd532No ratings yet

- Provinsi Jawa Timur Kota PasuruanDocument52 pagesProvinsi Jawa Timur Kota Pasuruankang_soerip100% (1)

- Arab Spring: Modernity, Identity and ChangeDocument287 pagesArab Spring: Modernity, Identity and ChangeSouhaSohatnNo ratings yet

- Arabs in Hollywood PDFDocument86 pagesArabs in Hollywood PDFRafay KamalNo ratings yet

- Product Wise For The Month of July-October 2012-13Document513 pagesProduct Wise For The Month of July-October 2012-13Mithu Himu MisirNo ratings yet