Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Group Family Psychotherapy During Relapse. Case Report of A Novel Intervention For Severe and Enduring Anorexia Nervosa

Uploaded by

ALOriginal Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Group Family Psychotherapy During Relapse. Case Report of A Novel Intervention For Severe and Enduring Anorexia Nervosa

Uploaded by

ALCopyright:

Available Formats

CLINICAL CASE

Volume 44, Issue 1, January-February 2021

doi: 10.17711/SM.0185-3325.2021.006

Group family psychotherapy during relapse.

Case report of a novel intervention for severe

and enduring anorexia nervosa

Laura González-Macías,1 Alejandro Caballero-Romo,1 María García-Anaya2

1

Clínica de la Conducta Alimentaria, ABSTRACT

Dirección de Servicios Clínicos,

Instituto Nacional de Psiquiatría

Background. Anorexia nervosa is a complex and highly variable disorder. Preventing patients from becoming

Ramón de la Fuente Muñiz, Ciudad

de México, México. resistant to treatments is fundamental since an important percentage develops a severe and enduring disorder;

2

Subdirección de Investigaciones and because relapse is highly associated with psychiatric comorbidity, poor prognosis, and serious medical

Clínicas, Instituto Nacional de consequences due to malnutrition. Contemporary treatments for anorexia nervosa support the benefits of in-

Psiquiatría Ramón de la Fuente volving the family in treatment, and although the gold standard of family psychotherapy offers an excellent

Muñiz, Ciudad de México, México.

option for anorexia nervosa, that intervention is aimed at early stages, and therapeutic options for later stages

Correspondence: of the disorder are reduced and not clearly established. Objective. Expose the therapeutic effect of the proto-

María García-Anaya col for severe and enduring cases of anorexia nervosa at relapse, used at the Clinic of Eating Behavior of the

División de Investigación Clínica,

National Institute of Psychiatry, Ramón de la Fuente Muñiz, whose theoretical foundation is systemic therapy.

Instituto Nacional de Psiquiatría

Ramón de la Fuente Muñiz. Method. To develop this case report, we carried out an in-depth review of the clinical records, and of the clinic

Calzada México-Xochimilco 101, attendance records of the case presented here. CARE clinical case report guidelines format were used. Re-

Colonia San Lorenzo Huipulco, sults. The case shows how a young woman, diagnosed with anorexia nervosa with clinical signs of severe and

Tlalpan 14370,

enduring anorexia nervosa (SE-AN), was able to achieve symptomatic remission after her parents, but not her,

Ciudad de México, México.

Phone: 55 4160-5453 were administered the protocol for SE-AN. Discussion and conclusion. Here we present an emblematic case

Email: garcia.anaya@gmail.com showing the importance of getting the parents involved in the treatment of anorexia nervosa.

Received: 16 November 2019

Accepted: 11 March 2020 Keywords: Anorexia nervosa, family psychotherapy, relapse, chronicity, maintaining factors.

Citation:

González-Macías, L., Caballero-Ro-

mo, A., & García-Anaya, M. (2021). RESUMEN

Group family psychotherapy during

relapse. Case report of a novel in- Antecedentes. La anorexia nervosa es un trastorno complejo y muy variable. Evitar que los pacientes se

tervention for severe and enduring

vuelvan resistentes a los tratamientos es fundamental, pues un porcentaje importante desarrolla un trastorno

anorexia nervosa. Salud Mental,

44(1), 31-37. grave y duradero; adicionalmente, la recaída está muy asociada con una alta comorbilidad psiquiátrica, un

mal pronóstico y graves consecuencias médicas debido a la desnutrición. El tratamiento actual de la anorexia

DOI: 10.17711/SM.0185-3325.2021.006

nervosa respalda los beneficios de involucrar a la familia en el tratamiento, y, aunque el estándar de oro en

psicoterapia familiar ofrece una excelente opción para la anorexia nervosa, dicha intervención está orientada

a etapas tempranas y las opciones para las etapas tardías del trastorno son reducidas, además de no estar

claramente establecidas. Objetivo. Exponer el efecto terapéutico del protocolo para casos graves y durade-

ros de anorexia nervosa en recaída, de la Clínica de Trastornos de la Conducta Alimentaria (CTA) del Instituto

Nacional de Psiquiatría Ramón de la Fuente Muñiz, cuya base teórica es la terapia sistémica. Método. Para

integrar este caso, realizamos una revisión a fondo del expediente clínico y de los registros asistenciales del

caso que aquí presentamos. Se utilizó el formato de reporte de caso de las guías CARE. Resultados. El caso

muestra cómo una joven, con signos clínicos de anorexia nervosa grave y duradera (AN-GD), pudo lograr

remisión sintomatológica después de que sus padres, pero no ella, recibieran tratamiento con el protocolo

para AN-GD. Discusión y conclusión. Aquí presentamos un caso emblemático que muestra la importancia

de involucrar a los padres en el tratamiento de la anorexia nervosa.

Palabras clave: Anorexia nervosa, psicoterapia familiar, recaída, cronicidad, factores mantenedores.

Salud Mental | www.revistasaludmental.mx 31

González-Macías et al.

BACKGROUND ment, the prolonged impasse, and the relapse that character-

ize this case, we consider this to be a disorder where early

Anorexia nervosa (AN) is a complex disorder. Its clinical signs of SEAN are manifested.

course is highly variable and the reasons why some indi- In this article we expose the therapeutic effect of the

viduals evolve towards chronicity, whereas others achieve protocol for severe and enduring cases of anorexia nervosa

remission and recovery, are not yet clear. Thus, preventing at relapse used at the Eating Behavior Clinic of the Insti-

patients from becoming resistant to treatments is fundamen- tuto Nacional de Psiquiatría Ramón de la Fuente Muñiz

tal since unfortunately, an important percentage of them (INPRFM, National Institute of Psychiatry). This protocol

tend to develop a severe and enduring disorder, and because is addressed to individuals diagnosed with anorexia ner-

relapse is highly associated with psychiatric comorbidity, vosa, and to their families; particularly their parents. In

poor prognosis, and serious medical consequences due to addition to the psychiatric and nutritional management

malnutrition (Treasure, Stein, & Maguire, 2015). administered according to treatment guidelines (National

The contemporary view on the therapeutics of anorexia Institute for Clinical Excellence, 2004), the protocol com-

nervosa supports the benefits of involving the family in the prehends attendance to the psychotherapeutic group for pa-

treatment, and over the years it has been demonstrated that tients with anorexia nervosa, and to the psychotherapeutic

better results are obtained if parents are committed to the support group for parents; administered separately. Group

treatment (Treasure & Cardi, 2017). sessions are held weekly for 2 hr., with an open format and

Among the current, most used interventions for the there is not a determined number of sessions conforming

treatment of AN, we can mention the Maudsley model and this intervention. In this format, both veteran and new in-

the new Maudsley model, intended for the management dividuals co-participate. The therapeutic intervention is ad-

of adolescents and adults (Rhodes, 2003; Schmidt, Wade, ministered by one psychotherapist and two co-therapist ex-

& Treasure, 2014); as well as the family-based treatment pert in eating disorders. It combines a psychodynamic style

and the emotion-focused family therapy, both based in the with cognitive analytical and supportive psychotherapy

transdiagnostic theory (Fairburn, Cooper, & Shafran, 2003; interventions. The protocol was developed upon the base

Lafrance Robinson, Dolhanty, Stillar, Henderson, & May- of systemic therapy theoretical foundations, which have

man, 2016; Loeb, Lock, Le Grange, & Greif, 2012). Despite widely described the influence of the family on predispos-

the great body of evidence supporting the effectiveness of ing and maintaining factors of the disorder (Bruch, 1978;

these interventions, they are intended for the treatment of Minuchin et al., 1975; Rausch Herscovici & Bay, 1990;

early stages of the disorder. Currently, therapeutic options Selvini-Palazzoli, Cirillo, Selvini, & Sorrentino, 1998).

are reduced for those individuals who begin to show signs Here we present an emblematic case, showing the im-

of a severe and enduring disorder (Touyz & Hay, 2015), and portance of getting the parents involved in the treatment of

they are not as clearly established as the effective treatments anorexia nervosa. This is the case of K, a young woman

for initial stages. diagnosed with anorexia nervosa with clinical signs of a se-

It is complex to talk about severe and enduring anorex- vere and enduring disorder, who achieved clinical improve-

ia nervosa (SEAN) given the lack of consensus about how ment after her parents, but nor her, were administered an

to best define this population (Ciao, Accurso, & Wonder- intervention with group family psychotherapy.

lich, 2016).

Defining SEAN has been operationalized in several dif-

ferent ways. Early theoretical perspectives highlighted mo-

CASE REPORT

tivational aspects such as “resistance” (Hamburg, Herzog,

Patient information

Brotman, & Stasior, 1989) or “refusal” (Goldner, 1989) to

treatment. It has also been broadly defined placing the fo- We present the case of K, a 23-year-old woman who showed

cus on “chronicity.” Others have defined it by chronicity up at the Eating Behavior Clinic (EBC) from the INPRFM

(as a duration of illness greater than ten years) and clinical six years ago, accompanied by her mother and father. Upon

severity (as the point at which symptoms significantly im- admission she was single, she had no romantic partner, and

pair quality of life (Robinson, 2009). Perhaps, currently the she was studying high school. Her socio-economic status

most comprehensive definition describes a combination of was medium.

clinical severity (as the difficulty in maintaining a regular

functioning), treatment failure (as failure to reach sustained Reason for consultation

improvement with previous treatments), and chronicity

(Golan, 2013). She was referred to psychiatric attention by the high school

Just as there is no current consensus about the defini- psychologist, given her poor academic performance and

tion of SEAN, there is no agreement about what is the best because of recurrent behavioral problems with her school-

way to treat it. So, given the poor response to standard treat- mates and with authority. It is noteworthy that they were K’

32 Salud Mental, Vol. 44, Issue 1, January-February 2021

Novel intervention for anorexia relapse

parents who sought psychiatric attention on the recommen- Her eating disorder started when she was 12 years old.

dation of the school psychologist, but not because of the The first behavior she identified was the change in the way

symptoms of the eating disorder. she ate, decreasing the intake of everything she considered

had excess calories, such as sweet food, flour, fat, and cere-

Family and psychosocial history als. Later she began restricting the intake of proteins until

she sustained a vegetarian diet. In addition, she regularly

They presented a familiar dysfunctional style characterized fasted and counted the ingested calories.

by an overprotective mother and a symbiotic relationship

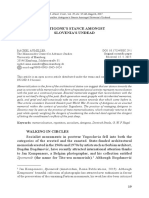

of the mother-daughter dyad. The father was emotionally Timeline (Figure 1)

detached from the family, and his roll was that of an eco-

nomic provider. K’s sister is eight years younger than her. Upon admission

K referred she had felt jealous from her sister since she was at the Eating

Reason for consultation

Disorders Clinic

born and so their siblings’ relationship has been troubled Poor academic performance and recurrent

behavioral problems with her schoolmates and

over the years. K’s parents presented a dysfunctional rela- with authority.

tionship characterized by lack of communication, frequent Family history

History of overprotective mother and symbiotic

conflicts, and infidelity of the father; they have separated relationship of the mother-daughter dyad. Emotionally

twice because of violence problems among them. detached father, functioning as economic provider.

Troubled relationship with her sister. Disruptive and

K’s relationship with her family was characterized for aggressive behavior towards her family.

Psychosocial history

showing disruptive and aggressive behavior towards her Frequent problems at school. Absence of lasting

parents and sister. At school, she had a long history of prob- friendships and romantic relationships.

lems such as being abusive with her peers, showing defi-

ant attitudes towards authority, and being frequently absent Clinical findings

BMI of 16.0 (malnutrition), vomiting frequency of 70/

from classroom and school. Regarding social functioning, week, compulsive exercise, self-injuries, frequent

casual sex, substance abuse, and depressive

K referred having no lasting friendships. She also said she symptoms. Poor to bad global functioning.

had never been able to keep a romantic relationship.

As for the nuclear family of K’s mother, her older sister Diagnostic assessment

had cerebral palsy, which caused K’s mother to function as Diagnosis made on information from the medical

history, and on clinical criteria for anorexia nervosa

mother of her siblings, while K’s grandmother took care of according to DSM-V.

the sister with the disability. She described that both her sib-

lings and her parents had always had problems controlling Initial treatment

Comprehensive treatment prescribed, according

their impulses. K’s mother reported having an eating disor- to the NICE guidelines (psychiatric and nutritional,

der during adolescence. She has also had multiple episodes plus psycho educative sessions).

of depression and anxiety, and is currently under pharmaco- Partial remission

logical treatment. after treatment, and

relapse thereafter Subsequent treatment

In reference to the nuclear family of K’s father, he re- EBC´s protocol for severe and enduring cases

ported that everyone in his family, including him, has had of anorexia nervosa at relapse (psychiatric

and nutritional attention according to the NICE

multiple stories of both, interpersonal and couple conflicts guidelines, plus psychotherapeutic attention for

the person with AN, and for parents).

due to the fact they have had both physical and verbal vio-

lent behaviors. K’s father has been an alcohol user since he

Reluctance to

was 18 years old. He is currently diagnosed with depression adhering to treatment

and is under pharmacological treatment. by the patient, with no Change in the protocol

clinical response for severe and enduring cases

Parents were encouraged to continue attending

Clinical findings group sessions, and stick to their daughter´s

treatment.

Upon admission, K presented a BMI of 16.0 ‒indicative of

Follow-up

malnutrition‒, frequency of vomiting of 70 a week, com- and outcomes Patient

pulsive exercise, self-injuries, risk behaviors, such as fre- Compliance of pharmacological treatment,

maintenance of an average of 23.0 BMI. As

quent casual sex and substance abuse, and depressive symp- for global functioning: completion of academic

toms. She also showed distortion and dissatisfaction with studies, improvement of her family relationship,

absence of aggressive behavior. She has entered

her body image, and refered perceiving herself as “big and in romantic relationship for the first time in life.

fat.” As for her global functioning, she presented lack of Parents

Enhancement of reflexive function in both

healthy coping strategies, interpersonal troubles, difficulties parents. Improvement of their partner relationship.

Progress in paternal/maternal functions.

completing high school, and serious defiant and violent be-

havior towards her parents and other authority figures. Figure 1. Case report flow diagram.

Salud Mental, Vol. 44, Issue 1, January-February 2021 33

González-Macías et al.

Diagnostic assessment Subsequent treatment

In this occasion, the prescription was the EBC’s protocol for

K was diagnosed with anorexia nervosa, binge-purgative sub-

severe and enduring cases of anorexia nervosa at relapse,

type. Diagnosis was established based on information from

which sustain psychiatric and nutritional treatment accord-

the medical history and on clinical criteria for anorexia ner-

ing to guidelines (National Institute for Clinical Excellence,

vosa according to the DSM-V, assessed through a semi-struc-

2004), and adds psychotherapeutic attention for the diag-

tured interview by a psychiatrist expert in eating disorders.

nosed individual and also for her parents. The protocol sets

After relapse, an expert psychiatrist made the clinical

the administration of a weekly session of 2 hr. at the psycho-

assessment, through semi-structured interview, in order to

therapeutic group for patients with anorexia nervosa, and

determine subsequent treatment.

the psychotherapeutic support group for the parents of those

patients; delivered in separated groups.

Treatment history

Although K was still reluctant to continue under treat-

Psychotherapy ment; she agreed to attend the psychotherapeutic group un-

der her parents’ pressure. After six sessions, she decided to

During the first interview with the psychotherapist, K re-

stop attending the psychotherapeutic group arguing that her

ferred she had received multiple psychological treatments,

medical condition was much better than the condition of

with no effect at childhood, because she regularly showed

the other attendees to the group. She additionally said, she

aggressive behaviors and harassment towards her school-

got worse each time she got exposed to the patients’ group.

mates, as well as lack of limits and defiant attitudes towards

authority. She revealed she used to make fun and ignore the Change in the protocol for severe and enduring cases

advice from all child psychologists who treated her.

The protocol states psychotherapeutic attention for both the

Psychiatry diagnosed individual and her parents. Given K’s refusal to

stick to the protocol, from that moment to date, she has only

She had never received psychiatric treatment up to her ad-

attended the psychiatrist appointments for pharmacological

mission at the EBC.

follow-up, every three to six months. However, her parents

were highly encouraged to continue attending their group

Therapeutic intervention along the case

sessions, and to stick to the prescriptions ordered by the psy-

Initial treatment chiatrist and the nutritionist to their daughter. They did it so.

A comprehensive treatment was prescribed for K at the

Follow-up and outcomes

EBC, according to the NICE guidelines (National Institute

for Clinical Excellence, 2004), including attention by a psy-

At the present time, K is 23 years old and her parents contin-

chiatrist and a nutritionist, plus psycho-educative sessions.

ue attending the psychotherapeutic support group sessions.

After 25 weeks of treatment, medical stabilization, de-

In order to know the outcomes of the protocol adminis-

crease of vomiting frequency and compulsive exercise was

tration, a semi-structured interview by a psychiatrist expert

achieved. However, K remained in impasse for the follow-

in eating disorders was applied to K, and clinical assessment

ing three years, showing amenorrhea, and a BMI of 18.5,

based on expertise was adapted for K’s parents. As for the

indicative of poor nutrition. As for behaviors such as casual

therapeutic achievements we can report the following.

sex, abusive behavior with her peers, and violent behavior

In regards to K’s actual condition, she has been able to

towards her parents also remained unchanged. Despite the

stick to the pharmacological treatment and maintain a sta-

impasse, it should be noted that during those three years she

ble and healthy BMI of 23.0 on average. As for her global

presented decrease of scholar absences, of defiant attitudes

functioning, she has completed academic studies at the uni-

towards school authority, and of substance use as well; so

versity, she has significantly improved the relationship with

she was able to complete high school.

her sister and her interpersonal relationships as well (for the

Relapse first time she has been able to keep romantic relationships

in two different occasions), and she has been able to keep

Shortly after K finished high school she relapsed, presenting

under control all her risk behaviors.

compulsive behaviors and weight loss again with a BMI of

In relation to K’s parents, we can say that the reflex-

17.5; this time she was reluctant to go on with her psychiat-

ive function of both parents has notably improved. They

ric treatment and her academic studies. For that reason, her

have referred that through the observation and analysis of

parents returned to the EBC to ask for help. They referred

the experiences shared at the group, they have been able to

feeling helpless and exceeded by her daughter’s attitudes,

identify their own behavior and, consequently, modify it.

and being afraid to face a situation they did not knew how

Likewise, they have been able to improve their ability to ob-

to handle.

34 Salud Mental, Vol. 44, Issue 1, January-February 2021

Novel intervention for anorexia relapse

serve their daughter’s behavior and, consequently, change treat of SEAN at relapse. We believe this is an emblemat-

the way they relate to her. ic case of the clinical application of the Eating Behavior

They have mentioned that the psychotherapeutic sup- Clinic’s protocol for SEAN since, after relapse, the patient

port group has helped them to recognize that they used to has only attended psychiatric and nutritional follow-up con-

have aggressive attitudes towards K, and they understood sultations, and she has not received any psychotherapeutic

that those attitudes were related to the anger they felt to- treatment again.

wards her. They also have been able to observe and modify Treatment guidelines for the early stages of the disorder

the ambivalence they showed for years about their daugh- (National Institute for Clinical Excellence, 2004) indicate the

ter’s improvement. In relation to it, they have acknowl- administration of cognitive behavioral psychotherapy as a re-

edged how for them it was more difficult to be parents of a quired condition in order to achieve an effective modification

healthy daughter than of a sick one, since in that way there of the symptomatology. Thus, we could expect, in late stages

was no longer someone to blame for situations such as fam- of the disorder, psychotherapy to be one pillar of the patient’s

ily dysfunction or lack of money. treatment. It is notorious that while in the case we present

They have also reported the treatment has helped them here such a condition did not happen, it is still remarkable

improve their partner relationship. They have noted an im- that the patient’s sympotmatology is currently in remission.

portant reduction in the conflicts related to their different In saying the above, we do not try to understate the psycho-

points of view, and of their recurrent struggles to reach therapeutic intervention that a patient should receive. On the

agreement and to give in to each other. contrary, the fact that in this case there was a modification in

Specifically, as for K’s mother, she knows now how to the patient’s condition through psychotherapeutic work with

set limits, which has helped her daughter to comply with her parents, supports the idea about there is a type of family

pharmacological treatment and continue her academic stud- functioning that in some cases predisposes and/or perpetu-

ies. In relation to the insight arising from the group ses- ates the disorder. Virtually all current interventions involve

sions, K’s mother granted having been negligent, and ad- the family taking an active part in the treatment (Fairburn et

mitted that K suffered abuse being a child. She was also al., 2003; Lock & Le Grange, 2005; Loeb et al., 2012; Raus-

able to identify certain affections she had had towards her ch Herscovici, 2013; Rhodes, 2003; Schmidt et al., 2014;

daughter that contributed to maintain K’s disorder; for ex- Treasure, Rhind, Macdonald, & Todd, 2015). This aims to

ample, giving birth at a troubled time of their marriage, or empower them, to provide them with information and tools

the fact that she wished a son instead of a daughter. She to improve their coping strategies and their understanding of

could also acknowledge that her daughter had not fulfilled the disorder, and to help them modify the ways in which they

her expectations as mother, and as a consequence she fo- relate to each other that might be perpetuating the disorder.

mented a troubled relationship. So, the family has become one of the focus of the treatment

Specifically, as for K’s father, he was able to recognize not because they necessarily have caused the disorder. How-

how through his daughter he tried to compensate the short- ever, the reorganization around the disorder generates dy-

comings of his life as student involving her, against her will, namics that in some families perpetuate the disorder in such a

at extra-curricular activities he would have liked to develop way they have become a part of it (Rausch Herscovici, 2013).

at. He could also acknowledge how his daughter’s disorder In relation to this, it has been described the influence of the

helped him to keep the mother engaged with K full time, so relatives, as well as the type of close interpersonal interaction

he could let unattended his family’s emotional needs. There- ‒crystallized through the expressed emotion (EE) construct‒,

fore, he was able to go out with friends as much as he wanted, affecting the adherence to treatment and outcome of the AN.

to get drunk, and be unfaithful to his wife; and even when he It also has been shown there is an interaction between the

used to be the economic provider for the family, he used to level of EE and the type of family intervention, so families

avoid his emotional responsibility as a father and husband. with higher levels of EE have a better outcome with sepa-

In summary, after the treatment of K’s parents at the rate family therapy (the subject with AN and the parents are

psychotherapeutic support group, emotions, thoughts, be- treated apart), compared to cojoint family therapy (Allan, Le

haviors, and global functioning were notoriously modified Grange, Sawyer, McLean, & Hughes, 2018; Duclos et al.,

in a positive way, both in K and her parents, at individual 2018; Eisler et al., 2000; Le Grange, Hoste, Lock, & Bryson,

and family level. Currently, K can be considered to be in 2011; Moskovich, Timko, Honeycutt, Zucker, & Merwin,

remission of the symptoms she formerly presented. 2017; Schmidt & Treasure, 2006; Uehara, Kawashima, Goto,

Tasaki, & Someya, 2001).

Regarding the findings mentioned above, we want to

DISCUSSION AND CONCLUSION point out that since the late 70’s it has been described that

eating disorders take place in the context of specific family

The clinical evolution observed in this case supports the dynamics driven by a set of rules in which family members

indication that group family psychotherapy is effective to tend to repeat behaviors that compromise the autonomy of

Salud Mental, Vol. 44, Issue 1, January-February 2021 35

González-Macías et al.

other members. Thus, a maintenance circuit for those behav- Finally, through this clinical case, we have sought to

iors emerges and the psychosomatic symptom is self-perpet- strength on the notion of treating the family to manage

uated over time (Dawson, Rhodes, & Touyz, 2014; Lecom- SEAN early during relapse. We consider the protocol we

te et al., 2019; Liebman, Minuchin, & Baker, 1974; Pace, used to treat this case constitutes a novel intervention for

Cavanna, Guiducci, & Bizzi, 2015; Reich, von Boetticher, several reasons which, additionally represent strengths

& Cierpka, 2016). This mechanism has been described as in our approach to this case: it addresses the need for fea-

characteristic of alexithymic (Onnis & Di Gennaro, 1987) or sible alternatives to treat anorexia nervosa in late stages,

psychosomatic families (Minuchin et al., 1975) in which the it places relapse as the opportunity to engage family into

eating disorder acts as a symptom that helps the family to treatment, it brings back to psychotherapy the approach

avoid conflict and emotional stress, or to express the conflict of systemic theory regarding family functioning in an-

somatically. Systemic therapy has described how communi- orexia nervosa, and it sheds light on systemic therapy

cation in these families occurs through the eating disorder, as a current and effective intervention for severe and en-

which becomes a channel needed to connect and cope with during cases.

the emotional world (Minuchin, Rosman, & Baker, 1978). We consider it is necessary to extend the follow-up pe-

The dynamics displayed by these families show character- riod in order to assess the protocol, and settle its strength

istics matching the toxic family stress, a term referring to a and application for anorexia nervosa with early signs severe

particular type of stress exposure that is frequent, sustained, and enduring disorder. We additionally acknowledge the

and uncontrollable, and which occurs in the absence of buff- need of further research of this intervention through ran-

ering protective factors. From that perspective, EE may rep- domized clinical trials.

resent a form of toxic family stress, since it corresponds to

Funding

maladaptive patterns of response to psychiatric illness (Peris

& Miklowitz, 2015). In that sense, EE can on the one hand None.

occur as a result of unresolved predisposing factors that act Conflict of interest

individually through attitudes such as high criticism, hostility

and/or emotional over-involvement expressed by relatives of The authors declare they have no conflicts of interest.

the patient with a psychiatric disorder. On the other hand, EE Informed consent

may become a factor that perpetuates the disorder and/or pre-

K and her parents orally consented to report their clinical case for

disposes a poor outcome (Allan et al., 2018; Le Grange et al.,

academic and research purposes.

2011; Moskovich et al., 2017; Schmidt & Treasure, 2006).

The Eating Behavior Clinic’s protocol for severe and en-

during anorexia nervosa is based in the theoretical principles REFERENCES

and clinical application of the systemic approach proposed Allan, E., Le Grange, D., Sawyer, S. M., McLean, L. A., & Hughes, E. K. (2018).

by Minuchin, Bruch, and Selvini (Bruch, 1978; Minuchin et Parental expressed emotion during two forms of family-based treatment for

al., 1975; Selvini-Palazzoli et al., 1998). This protocol focus- adolescent anorexia nervosa. European Eating Disorders Review, 26(1), 46-52.

es on the individual condition of each participant in relation doi: 10.1002/erv.2564

Bruch, H. (1978). The Golden Cage, (3a. Ed.). Cambridge, Massachusetts: Harvard

to the eating disorder acknowledging that, according to sys-

University Press.

temic theory, the achievement of modifications in the behav- Ciao, A. C., Accurso, E. C., & Wonderlich, S. A. (2016). What do we know about

ior of each individual family member is able to elicit changes severe and enduring anorexia nervosa? In S., Touyz, D., Le Grange, J. H.,

in the previous configuration of the whole system. So, one Lacey, & P., Hay, (Eds.). Managing Severe and Enduring Anorexia Nervosa. A

plausible reason why K was able to achieve remission, even clinician’s guide, (1st. Ed), (p. 299). New York City: Routledge.

Dawson, L., Rhodes, P., & Touyz, S. (2014). The recovery model and anorexia

when only her parents attended the psychotherapeutic ses-

nervosa. Australian & New Zealand Journal of Psychiatry, 48(11), 1009-1016.

sions, is that the modification of the parents’ behavior was doi: 10.1177/0004867414539398

able to elicit a reorganization of the family dynamics that Duclos, J., Dorard, G., Cook-Darzens, S., Curt, F., Faucher, S., Berthoz, S., …

directly impacted the way they related to her daughter and Godart, N. (2018). Predictive factors for outcome in adolescents with anorexia

the disorder. More technically, we may say that group fam- nervosa: To what extent does parental Expressed Emotion play a role? PLoS

ONE, 13(7), e0196820. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0196820

ily psychotherapy offered a reflective space for K’s parents,

Eisler, I., Dare, C., Hodes, M., Russell, G., Dodge, E., & Le Grange, D. (2000). Family

where they were able to identify what was their internal rep- therapy for adolescent anorexia nervosa: The results of a controlled comparison

resentation of their daughter, so they could understand, rec- of two family interventions. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, and

ognize and modify the behaviors held up by them that were Allied Disciplines, 41(6), 727-736. doi: 10.1017/S0021963099005922

perpetuating the disorder. We can also suggest that clinical Fairburn, C. G., Cooper, Z., & Shafran, R. (2003). Cognitive behaviour therapy for

eating disorders: A “transdiagnostic” theory and treatment. Behaviour Research

application of the protocol for severe and enduring anorexia

and Therapy, 41(5), 509-528. doi: 10.1016/S0005-7967(02)00088-8

nervosa was able to stimulate reflective function (Fonagy & Fonagy, P., & Target, M. (1997). Attachment and reflective function: their role in self-

Target, 1997) of K’s parents. We think this was a crucial ele- organization. Development and Psychopathology, 9(4), 679-700. doi: 10.1017/

ment to modify the dysfunction in the family. s0954579497001399

36 Salud Mental, Vol. 44, Issue 1, January-February 2021

Novel intervention for anorexia relapse

Golan, M. (2013). The journey from opposition to recovery from eating disorders: with eating disorders. Frontiers in Psychology, 6, 1145. doi: 10.3389/

Multidisciplinary model integrating narrative counseling and motivational fpsyg.2015.01145

interviewing in traditional approaches. Journal of Eating Disorders, 1, 19. doi: Peris, T. S., & Miklowitz, D. J. (2015). Parental expressed emotion and youth

10.1186/2050-2974-1-19 psychopathology: New directions for an old construct. Child Psychiatry and

Goldner, E. (1989). Treatment refusal in anorexia nervosa. International Journal of Human Behavior, 46(6), 863-873. doi: 10.1007/s10578-014-0526-7

Eating Disorders, 8(3), 297-306. doi: 10.1002/1098-108x(198905)8:3<297::aid- Rausch Herscovici, C. (2013). Family approaches. In B., Lask & R., Bryant-Waugh

eat2260080305>3.0.co;2-h (Eds.). Eating Disorders in Childhood and Adolescence, (4th. Ed.), (pp. 239-

Hamburg, P., Herzog, D. B., Brotman, A. W., & Stasior, J. K. (1989). The treatment 257). London: Routledge.

resistant eating disordered patient. Psychiatric Annals, 19(9), 494-499. doi: Rausch Herscovici, C., & Bay, L. (1990). Aspectos generales. In Anorexia nerviosa

10.3928/0048-5713-19890901-11 y bulimia. Amenazas a la autonomía, (1a. Ed.), (p. 198). Buenos Aires: Paidós.

Lafrance Robinson, A., Dolhanty, J., Stillar, A., Henderson, K., & Mayman, S. (2016). Reich, G., von Boetticher, A., & Cierpka, M. (2016). Terapia familiar psicodinámica

Emotion-focused family therapy for eating disorders across the lifespan: A pilot de la anorexia nerviosa. Revista de Psicopatología y Salud Mental del Niño y

study of a 2-day transdiagnostic intervention for parents. Clinical Psychology & del Adolescente, 27, 69-75. Retrieved from https://www.fundacioorienta.com/

Psychotherapy, 23(1), 14-23. doi: 10.1002/cpp.1933 wp-content/uploads/2019/02/Reich-G-R27.pdf

Le Grange, D., Hoste, R. R., Lock, J., & Bryson, S. W. (2011). Parental Expressed Rhodes, P. (2003). The Maudsley model of family therapy for children and

Emotion of Adolescents with Anorexia: Outcome in Family-Based Treatment. adolescents with anorexia nervosa: Theory, clinical practice, and empirical

Internal Journal of Eating Disorders, 44(8), 731-734. doi: 10.1002/eat.20877 support. Australian & New Zealand Journal of Family Therapy, 24(4), 191-

Lecomte, A., Zerrouk, A., Sibeoni, J., Khan, S., Revah-Levy, A., & Lachal, J. (2019). 198. doi: 10.1002/j.1467-8438.2003.tb00559.x

The role of food in family relationships amongst adolescents with bulimia Robinson, P. H. (2009). Severe and enduring eating disorder (SEED): Management

nervosa: A qualitative study using photo-elicitation. Appetite, 141, 104305. doi: of Complex Presentations of Anorexia and Bulimia Nervosa. West Sussex, UK:

10.1016/j.appet.2019.05.036 Wiley-Blackwell.

Liebman, R., Minuchin, S., & Baker, L. (1974). The role of the family in the treatment Schmidt, U., & Treasure, J. (2006). Anorexia nervosa: Valued and visible. A

of anorexia nervosa. Journal of the American Academy of Child Psychiatry, cognitive-interpersonal maintenance model and its implications for research

13(2), 264-274. doi: 10.1016/S0002-7138(09)61315-7 and practice. British Journal of Clinical Psychology, 45(3), 343-366. doi:

Lock, J., & Le Grange, D. (2005). Family-based treatment of eating disorders. 10.1348/014466505X53902

International Journal of Eating Disorders, 37(S1), S64-S67. doi: 10.1002/ Schmidt, U., Wade, T. D., & Treasure, J. (2014). The Maudsley Model of Anorexia

eat.20122 Nervosa Treatment for Adults (MANTRA): Development, Key Features, and

Loeb, K. L., Lock, J., Le Grange, D, & Greif, R. (2012). Transdiagnostic Preliminary Evidence. Journal of Cognitive Psychotherapy, 28(1), 48-71. doi:

Theory and Application of Family-Based Treatment for Youth with Eating 10.1891/0889-8391.28.1.48

Disorders. Cognitive and Behavioral Practice, 19(1), 17-30. doi: 10.1016/j. Selvini-Palazzoli, M., Cirillo, S., Selvini, M., & Sorrentino, A. M. (1998). Ragazze

cbpra.2010.04.005 anoressiche e bulimiche. La terapia familiare. Milano: Raffaello Cortina

Minuchin, S., Baker, L., Rosman, B. L., Liebman, R., Milman, L., & Todd, T. C. Editore.

(1975). A conceptual model of psychosomatic illness in children. Family Touyz, S., & Hay, P. (2015). Severe and enduring anorexia nervosa (SE-AN): in

organization and family therapy. Archives of General Psychiatry, 32(8), 1031- search of a new paradigm. Journal of Eating Disorders, 3(1), 26. doi: 10.1186/

1038. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1975.01760260095008 s40337-015-0065-z

Minuchin, S., Rosman, B. L., & Baker, L. (1978). Psychosomatic Families: Anorexia Treasure, J., & Cardi, V. (2017). Anorexia Nervosa, Theory and Treatment: Where

Nervosa in Context. Cambridge, Massachusetts and London, England: Harvard Are We 35 Years on from Hilde Bruch’s Foundation Lecture ? European Eating

University Press. Disorders Review, 25(3), 139-147. doi: 10.1002/erv.2511

Moskovich, A. A., Timko, C. A., Honeycutt, L. K., Zucker, N. L., & Merwin, Treasure, J., Rhind, C., Macdonald, P., & Todd, G. (2015). Collaborative

R. M. (2017). Change in expressed emotion and treatment outcome Care: The New Maudsley Model. Eating Disorders, 23(4), 366-376. doi:

in adolescent anorexia nervosa. Eating Disorders, 25(1), 80-91. doi: 10.1080/10640266.2015.1044351

10.1080/10640266.2016.1255111 Treasure, J., Stein, D., & Maguire, S. (2015). Has the time come for a staging model

National Institute for Clinical Excellence. (2004). Eating Disorders. Core to map the course of eating disorders from high risk to severe enduring illness?

interventions in the treatment and management of anorexia nervosa, bulimia An examination of the evidence. Early Intervention in Psychiatry, 9(3), 173-

nervosa, and related eating disorders. UK: National Institute for Clinical 184. doi: 10.1111/eip.12170

Excellence. Uehara, T., Kawashima, Y., Goto, M., Tasaki, S., & Someya, T. (2001).

Onnis, L., & Di Gennaro, A. (1987). Alessitimia: una revisione critica. Medicina Psychoeducation for the families of patients with eating disorders and changes

Psicosomatica, 32, 45-64. in expressed emotion: A preliminary study. Comprehensive Psychiatry, 42(2),

Pace, C. S., Cavanna, D., Guiducci, V., & Bizzi, F. (2015). When parenting fails : 132-138. doi: 10.1053/comp.2001.21215

alexithymia and attachment states of mind in mothers of female patients

Salud Mental, Vol. 44, Issue 1, January-February 2021 37

You might also like

- Resource Guide 2016 For WebDocument34 pagesResource Guide 2016 For WebNotarys To GoNo ratings yet

- Conversations in The Sand: Advanced Sandplay Therapy Training CurDocument169 pagesConversations in The Sand: Advanced Sandplay Therapy Training CurNancy Azanasía KarantziaNo ratings yet

- Family CounsellingDocument5 pagesFamily Counsellingkiran mahalNo ratings yet

- Read UK: Bullying - Exercises: PreparationDocument2 pagesRead UK: Bullying - Exercises: PreparationsttomsNo ratings yet

- Test Bank For Psychiatric and Mental Health Nursing For Canadian Practice 2nd Edition AustinDocument7 pagesTest Bank For Psychiatric and Mental Health Nursing For Canadian Practice 2nd Edition AustinBilly Riddle100% (29)

- The Good Enough Mother - SlidesDocument38 pagesThe Good Enough Mother - SlidesstphaniesNo ratings yet

- Introduction To The Case of StanDocument6 pagesIntroduction To The Case of StanApple Esmenos100% (2)

- Understanding Dementia Types, Stages, and ManagementDocument4 pagesUnderstanding Dementia Types, Stages, and Managementernie16estreraNo ratings yet

- Self-Evaluation Paper Practicum 1Document4 pagesSelf-Evaluation Paper Practicum 1api-326209227No ratings yet

- The Clinical Interview and AssessmentDocument6 pagesThe Clinical Interview and AssessmentIoana Antonesi100% (1)

- A New Therapy For Each Patient 2018Document18 pagesA New Therapy For Each Patient 2018ALNo ratings yet

- Cambridge English Advanced Sample Paper 4 Rue v2Document17 pagesCambridge English Advanced Sample Paper 4 Rue v2alina_nicola77No ratings yet

- Jrsocmed00123 0041Document5 pagesJrsocmed00123 0041Estefania AraqueNo ratings yet

- Adherence of Psychopharmacological Prescriptions To Clinical PDFDocument9 pagesAdherence of Psychopharmacological Prescriptions To Clinical PDFGaby ZavalaNo ratings yet

- bc7c2 ZACCAGNINO2016 - FOR PARTICIPANTS - EMDR Protocol For The Management of Dysfunctional Eating Behaviors in Anorexia NervosaDocument29 pagesbc7c2 ZACCAGNINO2016 - FOR PARTICIPANTS - EMDR Protocol For The Management of Dysfunctional Eating Behaviors in Anorexia Nervosaandreang95No ratings yet

- My ProjectDocument34 pagesMy ProjectrahmatullahqueenmercyNo ratings yet

- A Family Based Intervention of Adolescents With Eating Disorders The Role of AssertivenessDocument1 pageA Family Based Intervention of Adolescents With Eating Disorders The Role of AssertivenessMaria SokoNo ratings yet

- Maintaining Factors of Anorexia Nervosa Addressed From A Psychotherapeutic Group For Parents: Supplementary Report of A Patient's Therapeutic SuccessDocument14 pagesMaintaining Factors of Anorexia Nervosa Addressed From A Psychotherapeutic Group For Parents: Supplementary Report of A Patient's Therapeutic SuccessmargaranaNo ratings yet

- Rummel Kluge 2008Document11 pagesRummel Kluge 2008Patricia RivasNo ratings yet

- Efecto de Programa de 12 Sesiones de Psicoeducación, Mindfulness Basada en Terapia Cognitiva, Remediación Funcional para Trastornos BipolararesDocument9 pagesEfecto de Programa de 12 Sesiones de Psicoeducación, Mindfulness Basada en Terapia Cognitiva, Remediación Funcional para Trastornos BipolararesGiorgio AgostiniNo ratings yet

- The Overdiagnosis of Depression in Non-Depressed Patients in Primary CareDocument7 pagesThe Overdiagnosis of Depression in Non-Depressed Patients in Primary Careengr.alinaqvi40No ratings yet

- Promoção Da Saúde e Qualidade de VidaDocument7 pagesPromoção Da Saúde e Qualidade de VidaAdilson De Oliveira SilvaNo ratings yet

- Castellini 2018Document13 pagesCastellini 2018Maria GemescuNo ratings yet

- Pines City Colleges: College of NursingDocument3 pagesPines City Colleges: College of NursingMara Jon Ocden CasibenNo ratings yet

- The Association Between Personality and Eating Psychopathology in Inpatients With Anorexia NervosaDocument8 pagesThe Association Between Personality and Eating Psychopathology in Inpatients With Anorexia NervosaDaniela Sánchez AcostaNo ratings yet

- Depressive Disorder in Mexican Pediatric Patients With Systemic Lupus Erythematosus (SLE)Document6 pagesDepressive Disorder in Mexican Pediatric Patients With Systemic Lupus Erythematosus (SLE)Random PersonNo ratings yet

- SK891 IMplementation FBTDocument10 pagesSK891 IMplementation FBTmelissa PALACIOSNo ratings yet

- BMJ 334 7595 CR 00686Document10 pagesBMJ 334 7595 CR 00686samiratumananNo ratings yet

- Psychoeducation PsychpsisDocument12 pagesPsychoeducation PsychpsisRoxanaNo ratings yet

- ManiaDocument2 pagesManiajopet8180No ratings yet

- CCR3 8 2827Document8 pagesCCR3 8 2827jacopo pruccoliNo ratings yet

- MetabolicIssuesSevereMentalIllnessReview CITROME SouthernMedJ2005Document7 pagesMetabolicIssuesSevereMentalIllnessReview CITROME SouthernMedJ2005Leslie CitromeNo ratings yet

- Relapse in Anorexia NervosaDocument12 pagesRelapse in Anorexia Nervosacharoline gracetiani nataliaNo ratings yet

- Journal of Affective Disorders en 2010Document8 pagesJournal of Affective Disorders en 2010Valentina Erazo.No ratings yet

- Prospective 10-Year Follow-Up in Adolescent Anorexia Nervosa-Course, Outcome, Psychiatric Comorbidity, and Psychosocial AdaptationDocument10 pagesProspective 10-Year Follow-Up in Adolescent Anorexia Nervosa-Course, Outcome, Psychiatric Comorbidity, and Psychosocial AdaptationCătălina LunguNo ratings yet

- Feeling GreatDocument243 pagesFeeling GreatSunny LamNo ratings yet

- Marsipan Management of Really Sick Patients With Anorexia NervosaDocument13 pagesMarsipan Management of Really Sick Patients With Anorexia NervosaGaby ZavalaNo ratings yet

- A Randomized Controlled Trial of A Mindfulness-Based Intervention Program For People With Schizophrenia: 6-Month Follow-UpDocument14 pagesA Randomized Controlled Trial of A Mindfulness-Based Intervention Program For People With Schizophrenia: 6-Month Follow-UpOrion OriNo ratings yet

- Efficacy of Combined Cognitive Behavior Therapy and Hypnotherapy in Anorexia Nervosa A Case StudyDocument8 pagesEfficacy of Combined Cognitive Behavior Therapy and Hypnotherapy in Anorexia Nervosa A Case StudyCarol Rio AguirreNo ratings yet

- The Ability of Multifamily Groups To Improve Treatment Adherence in Mexican Americans With SchizophreniaDocument9 pagesThe Ability of Multifamily Groups To Improve Treatment Adherence in Mexican Americans With SchizophreniaEmaa AmooraNo ratings yet

- Benefits of Cognitive-Motor Intervention in MCI and Mild To Moderate Alzheimer DiseaseDocument6 pagesBenefits of Cognitive-Motor Intervention in MCI and Mild To Moderate Alzheimer DiseaseLaura Alvarez AbenzaNo ratings yet

- Geriatric Nursing: SciencedirectDocument6 pagesGeriatric Nursing: SciencedirectNaila SofwanNo ratings yet

- Dissociative Identity Disorder A Case of Three SelDocument2 pagesDissociative Identity Disorder A Case of Three SelMartín SalamancaNo ratings yet

- Contemporary Psychotherapeutic Interventions in Patients With Anorexia Nervosa - A ReviewDocument10 pagesContemporary Psychotherapeutic Interventions in Patients With Anorexia Nervosa - A ReviewJan LAWNo ratings yet

- Anorexia NervosaDocument4 pagesAnorexia NervosaFarida RahmaNo ratings yet

- Early Outcomes of A Pilot Psychoeducation Group Intervention For Children of A Parent With A Psychiatric Illness - Riebsschleger Et Al (2009)Document7 pagesEarly Outcomes of A Pilot Psychoeducation Group Intervention For Children of A Parent With A Psychiatric Illness - Riebsschleger Et Al (2009)Eduardo Aguirre DávilaNo ratings yet

- Recent Research AnDocument9 pagesRecent Research AnloloasbNo ratings yet

- Clin Psychology and Psychoth - 2021 - Meneguzzo - Alexithymia Dissociation and Emotional Regulation in Eating DisordersDocument7 pagesClin Psychology and Psychoth - 2021 - Meneguzzo - Alexithymia Dissociation and Emotional Regulation in Eating Disorderscatamedellin2011No ratings yet

- Examining The Associations BetDocument7 pagesExamining The Associations BetJenifer C. SalazarNo ratings yet

- Cognitive Behavioral Therapy For DepressDocument5 pagesCognitive Behavioral Therapy For DepressalbertoNo ratings yet

- A Randomized, Multicentre, Open-Label, Comparative Trial of Disulfuram, Naltrexone, and Acamprosate in The Treatment of Alcohol DependenceDocument9 pagesA Randomized, Multicentre, Open-Label, Comparative Trial of Disulfuram, Naltrexone, and Acamprosate in The Treatment of Alcohol DependenceAlexander ColeNo ratings yet

- Impacto de La Duración de La Psicosis No Tratada (DPNT) en El Curso y Pronóstico de La EsquizofreniaDocument7 pagesImpacto de La Duración de La Psicosis No Tratada (DPNT) en El Curso y Pronóstico de La EsquizofreniaDaniel Cossío MiravallesNo ratings yet

- Original Paper: Factors That Impact Caregivers of Patients With SchizophreniaDocument10 pagesOriginal Paper: Factors That Impact Caregivers of Patients With SchizophreniaMichaelus1No ratings yet

- Anorexia Integrated TreatmentDocument6 pagesAnorexia Integrated Treatmentmadequal2658No ratings yet

- An Exploratory Study On The Feasibility and Appropriateness of Family Psychoeducation For Postpartum Women With Psychosis in UgandaDocument13 pagesAn Exploratory Study On The Feasibility and Appropriateness of Family Psychoeducation For Postpartum Women With Psychosis in UgandaEduardo Aguirre DávilaNo ratings yet

- Resilience in Caregivers: A Systematic ReviewDocument11 pagesResilience in Caregivers: A Systematic ReviewNikolass01No ratings yet

- An Illustration of Collaborative Care With A FocusDocument12 pagesAn Illustration of Collaborative Care With A FocuscarolineNo ratings yet

- SchizoDocument4 pagesSchizoArlene Bonife MontallanaNo ratings yet

- Datadrive WWW Psy Wp-Content Uploads 2021 02 11656 Clinical-Guidance-On-Treatment-Resistant-SchizophreniaDocument9 pagesDatadrive WWW Psy Wp-Content Uploads 2021 02 11656 Clinical-Guidance-On-Treatment-Resistant-SchizophreniaDiana IstrateNo ratings yet

- Wpa040142 PDFDocument5 pagesWpa040142 PDFCătălina LunguNo ratings yet

- Articulo 1Document8 pagesArticulo 1Silvia CastellanosNo ratings yet

- Canmat 2005 PDFDocument65 pagesCanmat 2005 PDFFábio C NetoNo ratings yet

- Hypnosis Reduces Nausea and Pain in Cancer PatientsDocument7 pagesHypnosis Reduces Nausea and Pain in Cancer PatientsihsansabridrNo ratings yet

- Psychoeducation Improves Treatment Compliance in Schizophrenia PatientsDocument12 pagesPsychoeducation Improves Treatment Compliance in Schizophrenia PatientsAHNAF MARUF MAHENDRANo ratings yet

- Psychotic and Manic-Like Symptoms During Stimulant Treatment of Attention Deficit Hyperactivity DisorderDocument4 pagesPsychotic and Manic-Like Symptoms During Stimulant Treatment of Attention Deficit Hyperactivity DisorderElla AnggRainiNo ratings yet

- Triple Chronotherapy For The Rapid Treatment and Maintenance of Response in Depressed Outpatients A Feasibility and Pilot Randomised Controlled TrialDocument1 pageTriple Chronotherapy For The Rapid Treatment and Maintenance of Response in Depressed Outpatients A Feasibility and Pilot Randomised Controlled TrialFelipe SilvaNo ratings yet

- RESUMEN POSTERS - ACBS Annual World Conference 13 (Berlín, 2015)Document138 pagesRESUMEN POSTERS - ACBS Annual World Conference 13 (Berlín, 2015)LandoGuillénChávezNo ratings yet

- Development of A New Fear of Hypoglycemia Scale: FH-15Document9 pagesDevelopment of A New Fear of Hypoglycemia Scale: FH-15Javi PatónNo ratings yet

- Am J Psychiatry 2013 May 170-5 - 6 EnigmaticDocument8 pagesAm J Psychiatry 2013 May 170-5 - 6 EnigmaticKarla MenaresNo ratings yet

- Article Psychological MedicineDocument12 pagesArticle Psychological MedicineAnnita triyanaNo ratings yet

- Tdah DX & TtoDocument14 pagesTdah DX & TtoalejandroNo ratings yet

- Complex Cases and Comorbidity in Eating Disorders: Assessment and ManagementFrom EverandComplex Cases and Comorbidity in Eating Disorders: Assessment and ManagementNo ratings yet

- International Journal of Clinical and Health PsychologyDocument8 pagesInternational Journal of Clinical and Health PsychologyALNo ratings yet

- Nutrición Hospitalaria: Trabajo OriginalDocument6 pagesNutrición Hospitalaria: Trabajo OriginalPedro J. Conesa CerveraNo ratings yet

- Focus On Palliative Care in The ICUDocument3 pagesFocus On Palliative Care in The ICUALNo ratings yet

- 94-Texto Completo Del Artículo Con Figuras, Tablas, Etc. SIN Datos de Los Autores.-606-1-10-20210214Document8 pages94-Texto Completo Del Artículo Con Figuras, Tablas, Etc. SIN Datos de Los Autores.-606-1-10-20210214ALNo ratings yet

- Epidemiological and Pathological Aspects of Salmonellosis in Cattle in Southern BrazilDocument10 pagesEpidemiological and Pathological Aspects of Salmonellosis in Cattle in Southern BrazilALNo ratings yet

- Antigone'S Stance Amongst Slovenia'S Undead: Spomenik (The Name For Tito-Era Memorials) - Although BogdanovićDocument25 pagesAntigone'S Stance Amongst Slovenia'S Undead: Spomenik (The Name For Tito-Era Memorials) - Although BogdanovićALNo ratings yet

- Physical and Psychosomatic Health Outcomes in People Bereaved by Suicide Compared To People Bereaved by Other Modes of Death: A Systematic ReviewDocument16 pagesPhysical and Psychosomatic Health Outcomes in People Bereaved by Suicide Compared To People Bereaved by Other Modes of Death: A Systematic ReviewALNo ratings yet

- The Three Moral Dimensions of Grief: Bryanna MooreDocument19 pagesThe Three Moral Dimensions of Grief: Bryanna MooreALNo ratings yet

- Pitman2017 Article AttitudesToSuicideFollowingTheDocument11 pagesPitman2017 Article AttitudesToSuicideFollowingTheALNo ratings yet

- Barry, Emhoff, Rabkin, Olezeski, Lehrbach, Szczypinski y Gordis (2017) PDFDocument19 pagesBarry, Emhoff, Rabkin, Olezeski, Lehrbach, Szczypinski y Gordis (2017) PDFALNo ratings yet

- Bourassa, Letourneau, Holden y Turcotte (2017)Document19 pagesBourassa, Letourneau, Holden y Turcotte (2017)ALNo ratings yet

- God On The Fly? The Professional Mandates of Airport ChaplainsDocument19 pagesGod On The Fly? The Professional Mandates of Airport ChaplainsALNo ratings yet

- Alliance Focused Training 2015Document5 pagesAlliance Focused Training 2015ALNo ratings yet

- Boeckel, Wendt, Daruy-Filho, Martínez y Grassi-Oliveira (2017) PDFDocument7 pagesBoeckel, Wendt, Daruy-Filho, Martínez y Grassi-Oliveira (2017) PDFALNo ratings yet

- Orthorexic Eating BehaviorDocument6 pagesOrthorexic Eating BehaviorALNo ratings yet

- Boeckel, Wendt, Daruy-Filho, Martínez y Grassi-Oliveira (2017) PDFDocument7 pagesBoeckel, Wendt, Daruy-Filho, Martínez y Grassi-Oliveira (2017) PDFALNo ratings yet

- Stress Mood Disorders IBDDocument12 pagesStress Mood Disorders IBDALNo ratings yet

- Adapting Psychotherapy To Patient Reactance A Metanalysis 2018 PDFDocument12 pagesAdapting Psychotherapy To Patient Reactance A Metanalysis 2018 PDFALNo ratings yet

- Riew.... : First Firstly, - WLTHDocument2 pagesRiew.... : First Firstly, - WLTHALNo ratings yet

- Recovery from Serious Mental Illnesses: A Journey of HopeDocument1 pageRecovery from Serious Mental Illnesses: A Journey of HopejamieNo ratings yet

- Amets ZurutuzaDocument3 pagesAmets ZurutuzaMaitane ArrietaNo ratings yet

- Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder ADHD in DSM 5 A Trial For Cultural Adaptation in BangladeshDocument4 pagesAttention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder ADHD in DSM 5 A Trial For Cultural Adaptation in BangladeshEditor IJTSRDNo ratings yet

- Psych Viva QuestionsDocument2 pagesPsych Viva QuestionsAkshita BatraNo ratings yet

- Counseling and Mental Health Sample Assessment QuestionsDocument18 pagesCounseling and Mental Health Sample Assessment QuestionsAlok PandeyNo ratings yet

- Indefension AprendidaDocument3 pagesIndefension AprendidaJuan M NegreteNo ratings yet

- Andrew Arche Resume For HavenwyckDocument1 pageAndrew Arche Resume For Havenwyckapi-532284965No ratings yet

- Development of A Child Psychological Effects of Emotional Deprivation Impact On Suicide Rates PDFDocument3 pagesDevelopment of A Child Psychological Effects of Emotional Deprivation Impact On Suicide Rates PDFKhushi KranthiNo ratings yet

- A Greater Sense of Calm or Inner Peace. Increased Self-EsteemDocument2 pagesA Greater Sense of Calm or Inner Peace. Increased Self-EsteemRissa BarridaNo ratings yet

- Integrating Psychosocial Support Into NutritionDocument12 pagesIntegrating Psychosocial Support Into NutritionOgak JerryNo ratings yet

- Mental Health Work in The Community - Theory and Practice in Social Work and Community Psychiatric Nursing (PDFDrive)Document211 pagesMental Health Work in The Community - Theory and Practice in Social Work and Community Psychiatric Nursing (PDFDrive)Agung Gilberth Palumean IINo ratings yet

- Tma 1 Prep & Block 1 Intro SlidesDocument64 pagesTma 1 Prep & Block 1 Intro SlidesashleygvieiraNo ratings yet

- Could You Be Addicted To The Internet - Everyday HealthDocument18 pagesCould You Be Addicted To The Internet - Everyday HealthFranca BorelliniNo ratings yet

- Berg and Hayashi 2013 PDFDocument10 pagesBerg and Hayashi 2013 PDFRAMONA GABRIELA LEBADANo ratings yet

- ForumDocument4 pagesForumdaarshaan100% (2)

- Impact of Domestic Violence on ChildrenDocument5 pagesImpact of Domestic Violence on ChildrenSmallz AkindeleNo ratings yet

- Mental Status Exam GuideDocument8 pagesMental Status Exam GuideDianne GalangNo ratings yet

- Ess 7Document4 pagesEss 7api-582020074No ratings yet

- Senate of Serampore College (University)Document1 pageSenate of Serampore College (University)Valiant UnitedNo ratings yet

- Causes and Treatment of DepressionDocument12 pagesCauses and Treatment of DepressionGEETA MOHANNo ratings yet