Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Effect of Intensive Patient Education Vs Placebo Patient Education On Outcomes in Patients With Acute Low Back Pain A Randomized Clinical Trial

Uploaded by

soylahijadeunvampiroOriginal Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Effect of Intensive Patient Education Vs Placebo Patient Education On Outcomes in Patients With Acute Low Back Pain A Randomized Clinical Trial

Uploaded by

soylahijadeunvampiroCopyright:

Available Formats

Research

JAMA Neurology | Original Investigation

Effect of Intensive Patient Education vs Placebo Patient

Education on Outcomes in Patients With Acute Low Back Pain

A Randomized Clinical Trial

Adrian C. Traeger, PhD; Hopin Lee, PhD; Markus Hübscher, PhD; Ian W. Skinner, PhD; G. Lorimer Moseley, PhD; Michael K. Nicholas, PhD;

Nicholas Henschke, PhD; Kathryn M. Refshauge, PhD; Fiona M. Blyth, PhD; Chris J. Main, PhD; Julia M. Hush, PhD;

Serigne Lo, PhD; James H. McAuley, PhD

Supplemental content

IMPORTANCE Many patients with acute low back pain do not recover with basic first-line care

(advice, reassurance, and simple analgesia, if necessary). It is unclear whether intensive

patient education improves clinical outcomes for those patients already receiving first-line

care.

OBJECTIVE To determine the effectiveness of intensive patient education for patients

with acute low back pain.

DESIGN, SETTING, AND PARTICIPANTS This randomized, placebo-controlled clinical trial

recruited patients from general practices, physiotherapy clinics, and a research center in

Sydney, Australia, between September 10, 2013, and December 2, 2015. Trial follow-up was

completed in December 17, 2016. Primary care practitioners invited 618 patients presenting

with acute low back pain to participate. Researchers excluded 416 potential participants.

All of the 202 eligible participants had low back pain of fewer than 6 weeks’ duration and a

high risk of developing chronic low back pain according to Predicting the Inception of Chronic

Pain (PICKUP) Tool, a validated prognostic model. Participants were randomized in a 1:1 ratio

to either patient education or placebo patient education.

INTERVENTIONS All participants received recommended first-line care for acute low back pain

from their usual practitioner. Participants received additional 2 × 1-hour sessions of patient

education (information on pain and biopsychosocial contributors plus self-management

techniques, such as remaining active and pacing) or placebo patient education (active

listening, without information or advice).

MAIN OUTCOMES AND MEASURES The primary outcome was pain intensity (11-point numeric

rating scale) at 3 months. Secondary outcomes included disability (24-point Roland Morris

Disability Questionnaire) at 1 week, and at 3, 6, and 12 months.

RESULTS Of 202 participants randomized for the trial, the mean (SD) age of participants was

45 (14.5) years and 103 (51.0%) were female. Retention rates were greater than 90% at all

time points. Intensive patient education was not more effective than placebo patient

education at reducing pain intensity (3-month mean [SD] pain intensity: 2.1 [2.4] vs 2.4 [2.2];

mean difference at 3 months, –0.3 [95% CI, –1.0 to 0.3]). There was a small effect of intensive

patient education on the secondary outcome of disability at 1 week (mean difference, –1.6

points on a 24-point scale [95% CI, –3.1 to –0.1]) and 3 months (mean difference, –1.7 points,

[95% CI, –3.2 to –0.2]) but not at 6 or 12 months.

Author Affiliations: Author

CONCLUSIONS AND RELEVANCE Adding 2 hours of patient education to recommended affiliations are listed at the end of this

first-line care for patients with acute low back pain did not improve pain outcomes. Clinical article.

guideline recommendations to provide complex and intensive support to high-risk patients Corresponding Author: Adrian C.

Traeger, PhD, Sydney School of Public

with acute low back pain may have been premature.

Health, Faculty of Medicine and

Health, The University of Sydney,

TRIAL REGISTRATION Australian Clinical Trial Registration Number: 12612001180808 Level 10 King George V Bldg, 10

Missenden Rd, Camperdown,

JAMA Neurol. 2019;76(2):161-169. doi:10.1001/jamaneurol.2018.3376 New South Wales, 2050 Australia

Published online November 5, 2018. (adrian.traeger@sydney.edu.au).

(Reprinted) 161

© 2018 American Medical Association. All rights reserved.

Downloaded From: https://jamanetwork.com/ on 09/01/2020

Research Original Investigation Effect of Intensive Patient Education on Pain Outcomes in Patients With Acute Low Back Pain

F

or the past 5 years, the Global Burden of Disease Study1

has consistently ranked low back pain as the leading Key Points

cause of disability worldwide. Low back pain is second

Question Is intensive patient education effective as part of

only to the common cold as a reason for consulting a general first-line care for patients with acute low back pain?

practitioner.2 A recent international review highlighted a global

Findings In this randomized clinical trial of 202 adults with acute

crisis in the mismanagement of low back pain, with high rates

low back pain from Sydney, Australia, adding intensive patient

of guideline-discordant care in both high- and low-middle in-

education to first-line care of patients was no better at improving

come countries.3-5 In their call to action, the Lancet Low Back pain outcomes than a placebo intervention.

Pain Series Working Group authors recommended that re-

Meaning Intensive patient education should not be offered to

searchers and policy makers: “Develop and implement strat-

patients with acute low back pain who are receiving first-line care.

egies to ensure early identification and adequate education of

patients with low back pain at risk for persistence of pain and

disability.”3-5

To manage uncomplicated acute low back pain (fewer than to enrolling participants15 (the original trial protocol is avail-

6 weeks of pain duration), international guidelines recom- able in Supplement 1). The trial was prospectively registered.

mend that general practitioners provide advice, education, re- The University of New South Wales Human Research Ethics

assurance, and simple analgesics, if necessary.6 Although many Committee, Sydney, New South Wales, Australia, approved the

patients receiving this care improve rapidly, 33% experience study on February 5, 2013 (reference number: HC12664). We

a recurrence in the next 12 months7 and 20% to 30% develop obtained written, informed consent from all participants be-

chronic pain (defined as pain duration of 3 months or more).8 fore they enrolled in the trial.

Patients who are at high risk of pain chronicity may require Treatments took place at physiotherapy clinics, general

additional care, including second-line options such as physical practices, or clinic rooms at a research institute (Neurosci-

(eg, spinal manipulation) and/or psychological therapies (eg, psy- ence Research Australia) in Sydney, Australia. One of 2 trial cli-

chologically informed physiotherapy).6 However, most trials that nicians (A.C.T. and I.W.S.) provided the treatment at partici-

have evaluated adding second-line treatment options to standard pating centers. We recruited participants between September

guideline care for patients with acute low back pain have failed 10, 2013, and December 2, 2015. Trial follow-up was com-

to demonstrate effectiveness compared with placebo (eg, addi- pleted on December 17, 2016.

tion of spinal manipulation, nonsteroidal antiinflammatory

drugs, or both9; addition of structured exercises10; and addition Participants

of acupuncture, massage, or chiropractic care11). Patient educa- We sought to recruit participants aged 18 to 75 years who were

tion, a treatment that authors of a 2008 Cochrane review12 con- seeking care for acute low back pain with or without referred

cluded was effective for acute low back pain when applied in an leg pain. Participants with signs of radiculopathy (spinal nerve

intensive format and that every major clinical guideline recom- root compromise) were included. All participants were re-

mends (but with little instruction on intensity),13 has never been ferred from general practitioners or physiotherapists. We ex-

tested in a placebo-controlled trial. Any benefits observed in pre- cluded potential participants if they had the following: (1)

vious trials of patient education for acute low back pain could be chronic low back pain (more than 1 on a 11-point pain inten-

explained by nonspecific effects of the clinical encounter or the sity numeric rating scale for more than 3 months), (2) less than

characteristics of the usual care comparison. 3 of 10 on the pain intensity numeric rating scale over the past

Pain education, a form of intensive patient education that week, (3) low risk of pain chronicity (less than 30% absolute

is often included in pain management programs, requires up to risk of chronic pain according to the Predicting Inception of

2 hours during several encounters with a trained health practi- Chronic Pain (PICKUP) Tool8 [eMethods 1 in Supplement 2]),

tioner. It involves detailed discussion of pain, including psycho- (4) clinical features of serious spinal pathology (eg, cauda

social contributors and advice about pacing and activity. Trials equina syndrome, infection, fracture, or cancer) assessed by

have found clinically meaningful effects of pain education on pain a clinician, (5) poor command of the English language, (6) pre-

and disability in samples of patients with chronic pain.14 vious spinal surgery, or (7) a mental health condition that would

It is unknown whether intensive patient education, in ad- preclude study participation. Referring clinicians were trained

dition to recommended first-line care, can improve outcomes for to provide all recruited participants with guideline-based care

patients with acute low back pain. To address this gap in the lit- (advice to stay active, avoid bed rest, option of spinal manipu-

erature, we conducted, to our knowledge, the first randomized, lation, and/or simple analgesics). Staff were reimbursed per par-

placebo-controlled trial of patient education for acute low back ticipant recruited for time spent on the study.

pain (Preventing Chronic Low Back Pain [PREVENT] Trial).15

Randomization and Masking

We randomized participants in a 1:1 ratio to either intensive pa-

tient education or placebo patient education. The allocation

Methods schedule was generated by a researcher not involved in any other

Study Design aspect of the study. That researcher used a computerized random

This was an assessor-blinded, 1:1 parallel group, randomized, number table to generate the allocation sequence in random

placebo-controlled trial. We published a study protocol prior block sizes of 4, 6, 8, and 10. The same researcher who generated

162 JAMA Neurology February 2019 Volume 76, Number 2 (Reprinted) jamaneurology.com

© 2018 American Medical Association. All rights reserved.

Downloaded From: https://jamanetwork.com/ on 09/01/2020

Effect of Intensive Patient Education on Pain Outcomes in Patients With Acute Low Back Pain Original Investigation Research

the allocation sequence placed allocation codes into sequentially ing interest, and attention of the clinician) but without the edu-

numbered, sealed, opaque envelopes. cation component. Participants in the placebo patient educa-

Before randomization, all participants completed base- tion group received no information, advice, or education about

line data collection and received a standardized short history low back pain from the trial clinician. Participants were en-

and physical examination (approximately 10-minute length) couraged to talk about any topic that they desired. Trial clini-

with the trial clinicians (A.C.T. and I.W.S.). The short history cian responses were aimed to maintain the discussion for the

and physical examination were standardized using pro forma duration of the session. We included additional detail on the

documents (eMethods 2 in Supplement 2). The trial clini- placebo intervention in eMethods 4 in Supplement 2.

cians opened the envelope containing the group allocation. The

allocation was concealed from participants, referring clini- Outcomes and Measurements

cians, other trial staff, and outcome assessors. We collected self-reported data from participants at baseline

All treatment was provided during the acute phase of low (the first intervention session); 1 week after the 2 interven-

back pain within 6 weeks of pain onset. Each participant re- tion sessions were complete; and 3, 6, and 12 months after the

ceived 2 × 1–hour individual, face-to-face sessions of either pa- date of low back pain onset. Participants used online forms to

tient education or placebo patient education. The trial clini- complete outcome assessments. Baseline data included age,

cians (A.C.T. and I.W.S.) who provided the patient education sex, duration of episode, number of previous episodes, other

sessions were the same clinicians who provided the placebo painful areas, and work status. An assessor who was masked

patient education. An expert in pain education (G.L.M.) trained to treatment allocation arranged the collection of outcome data

both trial clinicians to deliver the patient education interven- using online forms. Participants completed the credibility and

tion. An expert clinical psychologist in pain management expectancy questionnaire17 in paper format immediately af-

(M.K.N.) trained both trial clinicians in the placebo patient edu- ter the trial clinician explained the rationale for the study and

cation intervention. Training for the patient education inter- before randomization. Trial staff monitored adherence to the

vention took approximately 16 hours, with 6 to 8 hours allo- 2 intervention sessions using a study calendar. The trial clini-

cated for practicing role-play scenarios. Training for the placebo cian audio recorded all intervention sessions, with the par-

patient education took approximately 4 hours and was supple- ticipants’ verbal consent, to monitor treatment fidelity. Treat-

mented with 4 online 45-minute videos demonstrating tech- ment fidelity was evaluated by 2 researchers (G.L.M. and

niques for providing a credible consultation that did not in- M.K.N.), who listened to the first and second sessions from 10

clude advice or education. randomly selected participants and judged whether the ses-

sions were patient education or placebo patient education. We

Interventions used κ to determine agreement.

Intensive Patient Education The primary outcome was mean pain intensity during the

We adapted the information and advice provided in the pa- past week (reported on an 11-point pain intensity numeric rat-

tient education group from the book Explain Pain,16 a text typi- ing scale), assessed 3 months after the onset of low back pain.

cally used for people with chronic pain. The intervention is de- Secondary outcomes and process measures are described in

scribed in full and according to the template for intervention eMethods 5 of Supplement 2.

description and replication (TIDieR) checklist in eMethods 3

in Supplement 2. In short, participants in the patient educa- Statistical Analysis

tion group were provided with a detailed explanation about We published our statistical analysis plan before analyzing our

the biopsychosocial nature of pain in the format of diagrams, results.18 A sample of 202 participants was required to en-

metaphors, and stories. The patient education intervention in- sure 80% power to detect a mean difference of 1 point on an

volved 3 main components: (1) reframing unhelpful beliefs 11-point numeric rating scale for pain intensity. Our power cal-

about low back pain, (2) presenting information about the bio- culation assumed an SD of 2.3 and a 2-sided α of .05 and was

logic basis and protective nature of both acute and chronic low adjusted with 15% loss to follow-up. We estimated the effect

back pain, and (3) evaluating understanding of new concepts of the intervention on the primary outcome using a mixed

and discussing techniques to promote recovery. Content was model for repeated measures. We treated time as a categori-

tailored to the individual according to specific concerns cal variable (1 week and 3, 6, or 12 months) and included

(eg, “I am worried I will have this back problem forever”) and group × time interactions to determine treatment effects at

misconceptions (eg, “I can’t work because my back is perma- each time point. As an exploratory sensitivity analysis, we

nently damaged”) that participants expressed during the con- calculated P values from mixed models for repeated mea-

sultation. Trial clinicians encouraged all participants to self- sures comparing between-group difference during the full 12-

manage their low back pain by remaining active and avoiding month trial, controlling for baseline and including all time

bed rest. Trial clinicians also instructed participants on be- points as categorical. We determined statistical significance

havioral therapy techniques such as pacing. to be P < .05 for a 2-sided test. We did not include study site

(physiotherapy practice, general practice, or research insti-

Placebo Patient Education tute) in the model because there was no evidence of site

We designed the placebo patient education sessions to con- differences between groups (χ2 test, P = .14). Details of the

trol for time with an expert clinician. The sessions mimicked analysis of secondary outcomes is provided in eMethods 5

all aspects of the patient education sessions (listening, show- of Supplement 2 and the complete mediation analysis19 in

jamaneurology.com (Reprinted) JAMA Neurology February 2019 Volume 76, Number 2 163

© 2018 American Medical Association. All rights reserved.

Downloaded From: https://jamanetwork.com/ on 09/01/2020

Research Original Investigation Effect of Intensive Patient Education on Pain Outcomes in Patients With Acute Low Back Pain

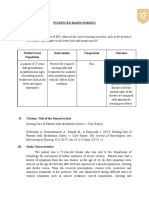

Figure 1. Flowchart of the Preventing Chronic Low Back Pain (PREVENT) Randomized Placebo-Controlled Trial

618 Participants referred from primary care

practitioners and assessed for eligibility

416 Excluded

266 Did not meet inclusion criteria

146 Low risk of pain chronicity

79 Persistent pain

18 Low pain intensity (<3/10)

7 Pain duration >6 wk

6 Previous spinal surgery

5 Age <18 or >75 y

4 Primary pain not in low back

1 Pregnancy

150 Other reasons

75 Could not be contacted

75 Declined

202 Randomized

101 Allocated to two 1-h treatments with patient 101 Allocated to two 1-h treatments with placebo

education patient education

98 Completed 1-wk follow-up 96 Completed 1-wk follow-up

3 Lost to follow-up (lost contact) 5 Lost to follow-up (lost contact)

97 Completed 3-mo follow-up 97 Completed 3-mo follow-up

4 Lost to follow-up (lost contact) 4 Lost to follow-up (lost contact)

96 Completed 6-mo follow-up 95 Completed 6-mo follow-up

5 Lost to follow-up (lost contact) 6 Lost to follow-up (lost contact)

94 Completed 12-mo follow-up 89 Completed 12-mo follow-up

7 Lost to follow-up (lost contact) 12 Lost to follow-up (lost contact)

101 Included in primary analysis 101 Included in primary analysis

eResults 1 of Supplement 2. Two authors (S.L. and H.L.) per- for further investigation of their symptoms. Psychological char-

formed the statistical analyses. acteristics were similar between groups; scores for depres-

sion and catastrophizing scales were lower and scores for self-

efficacy were higher than those seen in samples from patients

with chronic pain who attended tertiary care.20

Results All participants completed both trial sessions. Treatment

Between September 10, 2013, and December 2, 2015, we credibility scores were not different between groups (mean [SD]

screened 618 potential participants. Figure 1 shows the flow credibility and expectancy questionnaire score for patient edu-

of participants through the trial. The main reasons for partici- cation vs placebo patient education: 36.6 [8.8] vs 35.3 [10.5];

pant exclusion included low risk of pain chronicity (n = 146), mean difference, –1.3; 95% CI, –4.0 to 1.4). For our treatment

chronic pain (n = 79), declined participation (n = 75), or could fidelity check, raters correctly categorized all recordings as pa-

not be contacted after initial referral from the primary care prac- tient education or placebo patient education. There was per-

titioner (n = 75). Other reasons for exclusion are shown in fect agreement between raters (κ = 1).

Figure 1. One potential participant was excluded in error be- The primary analysis (Table 2) showed that patient edu-

cause of pregnancy. cation was not more effective than placebo patient education

The 2 groups had similar demographic and clinical char- at reducing pain intensity at our primary end point (3-month

acteristics at baseline (Table 1). Of 202 participants random- follow-up mean difference, –0.3 points on an 11-point scale;

ized for the trial, 103 (51.0%) were female. Participants were 95% CI, –1.0 to 0.3; P = .31). Mean (SD) pain intensity de-

middle-aged (mean [SD] age, 45.1 [14.5] years), had fewer than creased from 6.3 [2.4] at baseline to 2.1 [2.4] at 3 months in the

2 weeks of low back pain, and had experienced 3 previous epi- patient education group and from 6.1 [2.2] at baseline to 2.4

sodes of low back pain. Physiotherapists referred most par- [2.2] at 3 months in the placebo patient education group.

ticipants (83%). Half of the sample (52%) felt there was a need (Figure 2).

164 JAMA Neurology February 2019 Volume 76, Number 2 (Reprinted) jamaneurology.com

© 2018 American Medical Association. All rights reserved.

Downloaded From: https://jamanetwork.com/ on 09/01/2020

Effect of Intensive Patient Education on Pain Outcomes in Patients With Acute Low Back Pain Original Investigation Research

Table 1. Baseline Characteristicsa

Characteristic Patient Education (n = 101) Placebo Patient Education (n = 101)

Age, mean (SD), y 46.5 (14.7) 43.8 (14.1)

Female sex 53 (52.5) 50 (49.5)

Clinical characteristic

Pain duration, mean (SD), d 12.5 (7.7) 13.5 (8.7)

No. of previous episodes, median (IQR) 3 (5) 3 (7)

No. of other pain sites, mean (SD) 1.0 (1.2) 1.1 (1.3)

Referred by general practitioner 19 (18.8) 16 (15.8)

Referred by physiotherapist 82 (81.2) 85 (84.2)

First episode of back pain 21 (20.8) 18 (17.8)

Pain referred to leg 47 (46.5) 57 (56.4)

Pain in areas other than back or leg 57 (56.4) 55 (54.5)

Work absence or reduced hours 22 (21.8) 31 (30.7)

Receiving pain medication 50 (49.5) 54 (53.5)

Outcome scores at baseline

Pain intensity, mean (SD)b

Week 6.3 (2.4) 6.1 (2.2)

Current 4.0 (2.2) 4.0 (2.3)

Pain interference, mean (SD)c 6.0 (2.5) 6.4 (2.6)

Disability, mean (SD)d 11.0 (5.4) 11.7 (5.8)

Depressive symptoms, mean (SD)e 4.1 (3.7) 5.1 (5.0)

Reassurance

Nothing seriously wrong, mean (SD)f 5.6 (2.7) 5.4 (2.7)

Yes, perceive a need for further tests 51 (50.5) 55 (54.5)

Process measures at baseline, mean (SD)

Neuroscience knowledgeg 6.0 (1.8) 5.9 (1.6)

Pain attitudes: pain is sign of damageh 2.3 (1.2) 2.5 (1.1)

Pain self-efficacyi 35.5 (13.1) 33.1 (13.0)

Catastrophizingj 18.3 (12.0) 19.9 (11.2)

Back beliefsk 27.7 (6.8) 28.3 (6.4)

g

Abbreviation: IQR, interquartile range. Neurophysiology of Pain Questionnaire with range from 0 (no knowledge)

a

Data are presented as number (percentage) of patients unless otherwise to 19 (highest knowledge).

h

indicated. Survey of Pain Attitudes, question 3 from 1-item version: “The pain I feel is a

b

Numeric rating scale with range from 0 (no pain) to 10 (worst pain possible). sign that damage is being done.” Range from 0 (very untrue for me) to 4

c

(very true for me).

Numeric rating scale with range from 0 (no interference) to 10 (highest

i

interference possible). Pain Self-Efficacy Questionnaire with range from 0 (low pain self-efficacy)

d

to 60 (high pain self-efficacy).

Roland Morris Disability Questionnaire with range from 0 (no disability) to 24

j

(high disability). Pain Catastrophizing Scale with range from 0 (low catastrophizing) to 52

e

(high catastrophizing).

Depression severity scale of Depression, Anxiety and Stress Scale with range

k

from 0 (no depressive symptoms) to 42 (high depressive symptoms). Back Beliefs Questionnaire with range from 9 (maladaptive or pessimistic

f“

beliefs) to 45 (helpful or positive beliefs).

How reassured do you feel that there is no serious condition causing your back

pain?” Range from 0 (not reassured at all) to 10 (completely reassured).

Table 2. Primary Outcomes for the Patient Education and Placebo Patient Education Groups

at 1 Week and 3, 6, and 12 Months

Point Estimates, Mean (SD)

Patient Placebo Patient

Variable Education Education Mean Difference (95% CI) P Value

Pain intensity during the past week

Abbreviation: NA, not applicable.

1 wk 3.2 (2.4) 3.1 (2.2) 0.1 (−0.5 to 0.8) .69

a

P value is from mixed models for

3 mo 2.1 (2.4) 2.4 (2.2) −0.3 (−1.0 to 0.3) .31

repeated measures comparing

6 mo 2.3 (2.6) 2.5 (2.3) −0.2 (−0.8 to 0.5) .59 between-group difference during

12 mo 1.8 (2.2) 2.5 (2.4) −0.6 (−1.3 to 0.1) .07 the full 12-month trial, controlling

for baseline and including time

Overall intervention effecta NA NA NA .26

points as a categorical variable.

jamaneurology.com (Reprinted) JAMA Neurology February 2019 Volume 76, Number 2 165

© 2018 American Medical Association. All rights reserved.

Downloaded From: https://jamanetwork.com/ on 09/01/2020

Research Original Investigation Effect of Intensive Patient Education on Pain Outcomes in Patients With Acute Low Back Pain

Figure 2. Treatment Effects of Intensive Patient Education on Pain and Disability

A Pain intensity B Disability

8 14

7 12

Patient education

6 Placebo patient education

10

Pain Intensity

Disability

8 A, Mean pain intensity score (primary

4 outcome) using a numeric rating scale

6 ranging from 0 (no pain) to 10 (worst

3

4 pain possible). B, Mean disability

2

outcomes score at 1 week and 3, 6,

1 2 and 12 months using the Roland

0 0 Morris Disability Questionnaire

1 wk 3 mo 6 mo 12 mo 1 wk 3 mo 6 mo 12 mo ranging from 0 (no disability) to 24

Baseline Time Baseline Time (high disability). Whiskers indicate

95% CIs.

There was a small effect of treatment group on disability, with 6 months, or 12 months after the onset of acute low back pain.

patient education lower than placebo patient education at 1 week Disability was significantly lower in the intervention group

(mean difference, –1.6 points on a 24-point scale; 95% CI, –3.1 to compared with the placebo group at 1 week and 3 months but

–0.1; P = .03) and at 3 months (mean difference, –1.7 points; not at 6 months or 12 months. The short-term effects on dis-

95% CI, –3.2 to –0.2; P = .03) (Table 3). There were no between- ability, although consistent with those from similar trials,21

group differences in disability at 6- or 12-month follow-up. were below published guidance on clinically meaningful ef-

There were some significant between-group differences fects (2 points on a 24-point Roland Morris Disability Ques-

in secondary outcomes (Table 3). The odds of having a recur- tionnaire and 1 point on a 10-point numeric rating scale).22 Our

rence of low back pain at 12 months were lower in the patient results suggest that offering more intensive patient educa-

education group than in the placebo patient education group tion to patients with acute low back pain than that provided

(odds ratio, 0.44; 95% CI, 0.24-0.82). Pain interference and the as part of standard practice does not reduce pain intensity or

odds of seeking health care were also lower in the patient edu- lead to meaningful reductions in disability.

cation group at 3 months (pain interference: mean differ- Our results challenge a widespread belief that patient edu-

ence, –0.8; 95% CI, –1.5 to –0.1; P = .02; health care seeking: cation is an effective strategy for treatment of acute low back

odds ratio, 0.43; 95% CI, 0.19-0.93), but results for these vari- pain. For example, every clinical guideline recommends pa-

ables were not lower at 6 or 12 months. Pain attitudes and re- tient education to manage acute low back pain.13 These rec-

assurance at 1 week were higher in the patient education group ommendations are, however, often unaccompanied by an evi-

(pain attitudes: mean difference, –0.9; 95% CI, –1.2 to –0.5; dence statement (eg, neither US23 nor UK22 guidelines cite

P < .001; reassurance [“How reassured do you feel that there evidence for patient education) or instruction on how patient

is no serious condition causing your back pain?”]: mean dif- education interventions should be conducted.24 Two system-

ference, 1.2; 95% CI, 0.4-2.0; P = .003), and the effect on pain atic reviews have concluded that primary care–based patient

attitudes persisted at 12 months. education is effective for acute low back pain.12,25 The avail-

Patient education was not more effective than placebo pa- able Cochrane review12 of individual patient education in-

tient education for reducing depressive symptoms, the incidence cluded 6 trials of patient education compared with usual care:

of chronic low back pain, or global perceived change (Table 3). 3 trials of brief interventions (<20 minutes) and 3 trials of in-

The causal mediation analysis confirmed that patient education tensive interventions (>2 hours). The authors concluded that

reduced catastrophizing and unhelpful beliefs (primary treatment intensive patient education may be more effective at increas-

targets), but these psychologic mechanisms did not reduce pain ing return-to-work rates compared with usual care based on

intensity (full results of mediation analysis reported in eResults 2 trials (n = 1432). However, those trials did not include pain

1, eTables 1 and 2, and eFigures 1-3 in Supplement 2). There were or disability outcomes. Although a more recent review of 14

no reported adverse events in either treatment group. There was trials found that brief patient education could reduce back pain–

no evidence that out-of-trial therapy confounded treatment ef- related distress (n = 4872),25 it was unclear whether these in-

fects (eResults 2 and eTable 2 in Supplement 2). terventions could improve other clinical outcomes such as

pain.26 Of importance, our mediation analysis (eResults 1 in

Supplement 2) suggests that interventions aimed at reducing

pain-related distress (eg, catastrophization) are unlikely to in-

Discussion fluence the pain experience as much as previously thought.

Our study provides evidence that intensive patient educa-

tion is not effective compared with placebo for patients with Strengths and Limitations

acute low back pain. Two 1-hour sessions of patient educa- This trial15 had several strengths. It was the first trial, to our knowl-

tion were no more effective than a placebo intervention for im- edge, to test a patient education intervention against a credible

proving pain at our primary end point of 3 months or at 1 week, placebo (ie, a professional consultation without any information

166 JAMA Neurology February 2019 Volume 76, Number 2 (Reprinted) jamaneurology.com

© 2018 American Medical Association. All rights reserved.

Downloaded From: https://jamanetwork.com/ on 09/01/2020

Effect of Intensive Patient Education on Pain Outcomes in Patients With Acute Low Back Pain Original Investigation Research

Table 3. Secondary Outcomes for the Patient Education and Placebo Patient Education Groups

at 1 Week and 3, 6, and 12 Monthsa

Placebo Patient Effect Measure Mean Difference

Variable Patient Education Education or OR (95% CI) P Value

Chronic low back pain at 3 mo, 33/96 (34.4) 42/93 (45.1) 0.63 (0.32 to 1.14) .13

No./total No. (%)b

Disabilityc

1 wk 5.6 (5.2) 7.1 (5.8) −1.6 (−3.1 to −0.1) .03

3 mo 3.5 (4.6) 4.9 (6.0) −1.7 (−3.2 to −0.2) .03 Abbreviations: NA, not applicable;

OR, odds ratio.

6 mo 3.8 (5.2) 4.3 (5.2) −0.8 (−2.4 to 0.7) .28 a

Data are presented as mean (SD)

12 mo 3.0 (4.7) 3.8 (5.1) −0.8 (−2.4 to 0.7) .29 unless otherwise indicated.

Overall intervention effectd NA NA NA .17 b

Reporting 2 or more on an 11-point

Pain interferencee pain intensity numeric rating scale

during the past week and no periods

1 wk 2.8 (2.7) 2.9 (2.5) −0.1 (−0.8 to 0.6) .71

of recovery at that time.

3 mo 1.5 (2.1) 2.3 (2.4) −0.8 (−1.5 to −0.1) .02 c

Roland Morris Disability

6 mo 1.8 (2.6) 1.9 (2.3) −0.1 (−0.8 to 0.6) .87 Questionnaire with range from 0

12 mo 1.6 (2.4) 2.0 (2.5) −0.4 (−1.1 to 0.3) .30 (no disability) to 24 (high disability).

d

Overall intervention effectd NA NA NA .16 P value is from mixed models for

repeated measures comparing

Depressive symptomsf

between-group difference during

1 wk 2.6 (4.1) 3.3 (4.3) −0.7 (−1.8 to 0.5) .26 the full 12-month trial, controlling

3 mo 2.1 (3.9) 2.5 (4.1) −0.5 (−1.7 to 0.6) .36 for baseline and including time

points as a categorical variable.

Overall intervention effectd NA NA NA .89

e

Numeric rating scale with range

Current pain intensityg

from 0 (no interference) to 10

1 wk 2.3 (2.1) 2.2 (2.1) 0.1 (−0.5 to 0.7) .69 (highest interference possible).

f

3 mo 1.5 (2.0) 2.1 (2.1) −0.6 (−1.2 to −0) .04 Depression severity scale of

6 mo 1.8 (2.5) 1.8 (1.9) −0.1 (−0.7 to 0.5) .78 Depression, Anxiety, and Stress

Scale with range from 0 (no

12 mo 1.4 (2.1) 1.7 (2.1) −0.3 (−0.9 to 0.3) .33 depressive symptoms) to 42 (high

Overall intervention effectd NA NA NA .13 depressive symptoms).

g

Seeking health care for low Numeric rating scale with range

back pain, No./total No. (%) from 0 (no pain) to 10 (worst pain

3 mo 73/96 (76.0) 82/93 (88.2) 0.43 (0.19 to 0.93) .03 possible).

h

6 mo 44/95 (46.3) 48/91 (52.7) 0.77 (0.43 to 1.38) .38 Global Back Recovery Scale.

i

12 mo 32/91 (35.2) 38/87 (43.7) 0.70 (0.38 to 1.28) .25 Recurrence was defined as

h answering yes to both of the

Global change at 3 mo 8.1 (1.7) 7.8 (2.0) −0.3 (−0.9 to 0.2) .11

following questions: (1) “In the last 6

Recurrence at 12 mo, 26/91 (28.6) 41/87 (47.1) 0.44 (0.24 to 0.82) .01 months/12 months, has your lower

No./total No. (%)i back pain gone away completely for

Pain attitudes a period of more than 30 days, only

1 wk 1.3 (1.2) 2.2 (1.3) −0.9 (−1.2 to −0.5) <.001 to return later on?” and (2) “If yes,

did the return of low back pain last

12 mo 1.2 (1.2) 1.6 (1.3) −0.4 (−0.7 to 0) .03

at least 24 hours with a pain

Overall intervention effectd NA NA NA .16 intensity of more than 2/10?”

Nothing seriously wrong 7.6 (2.5) 6.5 (2.9) 1.2 (0.4 to 2.0) .003 j

“How reassured do you feel that

(0-10) at 1 wkj there is no serious condition causing

Yes, perceive a need for 25/98 (25.5) 36/96 (37.5) 0.57 (0.31 to 1.05) .07 your back pain?” Range from 0 (not

further tests at 1 wk, reassured at all) to 10 (completely

No./total No. (%) reassured).

or advice) in patients with acute low back pain. This strategy al- other trials on acute low back pain conducted in the same geo-

lowed us to determine the specific effects of patient education graphical area of Sydney (approximately 15%-20%).9,27 We are

and control for effects produced by a clinical encounter, for ex- therefore confident that we included participants who were at

ample, those from the attention of a health professional or from high risk of pain chronicity.

the credibility of an impending treatment. We trained 2 trial cli- This study also has limitations. First, trial clinicians could not

nicians to ensure treatment fidelity. Retention rates were high be blinded to treatment allocation. However, results of our au-

(>90% at all time points). We followed a published trial protocol15 dit suggested that there were no systematic differences in treat-

and statistical analysis plan.18 Data were collected and analyzed ment credibility or treatment fidelity. Second, interventions in

by researchers who were masked to group allocation. the PREVENT trial15 were provided by trial physiotherapists, and

We used PICKUP, a validated prognosis model,8 to exclude it is unclear whether our results would have been the same if the

people with acute low back pain who were at lower than aver- participant’s health practitioner provided the intervention. Third,

age risk of pain chronicity. Approximately 40% of included par- we performed a number of statistical comparisons, which al-

ticipants developed chronic low back pain, a rate twice that of though planned, increased the risk of Type I error. Interpretation

jamaneurology.com (Reprinted) JAMA Neurology February 2019 Volume 76, Number 2 167

© 2018 American Medical Association. All rights reserved.

Downloaded From: https://jamanetwork.com/ on 09/01/2020

Research Original Investigation Effect of Intensive Patient Education on Pain Outcomes in Patients With Acute Low Back Pain

of the statistically significant effects of intensive patient educa-

tion on some secondary outcomes, such as pain interference and Conclusions

recurrence and odds of seeking health care (Table 3), must con-

sider this potential limitation. Finally, because both groups re- For patients with acute low back pain who received first-line

ceived basic patient education as part of recommended first-line care, intensive patient education was no more effective than

care and many recovered despite being classified as being high a placebo intervention. Adding complex, time-consuming treat-

risk, the potential for between-group differences may have been ments to primary-care based advice and reassurance is likely

reduced. to be unnecessary for most patients with acute low back pain.

ARTICLE INFORMATION Henschke, Refshauge, McAuley. 6. Traeger A, Buchbinder R, Harris I, Maher C.

Accepted for Publication: August 24, 2018. Conflict of Interest Disclosures: Prof Moseley Diagnosis and management of low-back pain in

reported receiving author royalties for books primary care. CMAJ. 2017;189(45):E1386-E1395.

Published Online: November 5, 2018. doi:10.1503/cmaj.170527

doi:10.1001/jamaneurol.2018.3376 entitled Explain Pain. No other disclosures were

reported. 7. da Silva T, Mills K, Brown BT, Herbert RD,

Author Affiliations: Neuroscience Research Maher CG, Hancock MJ. Risk of recurrence of low

Australia, Sydney, New South Wales, Australia Funding/Support: The Australian National Health

and Medical Research Council funded this trial back pain: a systematic review. J Orthop Sports Phys

(Traeger, Lee, Hübscher, Skinner, Moseley, Ther. 2017;47(5):305-313. doi:10.2519/jospt.2017.7415

McAuley); Sydney School of Public Health, Faculty (project identification number: 1047827), which

of Medicine and Health, The University of Sydney, was investigator initiated (chief investigator, Prof 8. Traeger AC, Henschke N, Hübscher M, et al.

Sydney, New South Wales, Australia (Traeger, McAuley; coinvestigators, Dr Henschke and Prof Estimating the risk of chronic pain: development

Henschke); Centre for Statistics in Medicine, Nicholas, Moseley, Main, Blyth, and Refshauge). and validation of a prognostic model (PICKUP) for

Nuffield Department of Orthopaedics, Dr Traeger, Dr Lee, and Prof Moseley were patients with acute low back pain. PLoS Med. 2016;

Rheumatology and Musculoskeletal Sciences, supported by National Health and Medical Research 13(5):e1002019. doi:10.1371/journal.pmed.1002019

University of Oxford, Oxford, United Kingdom Council research fellowships. 9. Hancock MJ, Maher CG, Latimer J, et al.

(Lee); Graduate School of Health, University of Role of the Funder/Sponsor: The funding Assessment of diclofenac or spinal manipulative

Technology, Sydney, New South Wales, Australia organizations had no role in the design and conduct therapy, or both, in addition to recommended

(Skinner); Sansom Institute for Health Research, of the study; collection, management, analysis, and first-line treatment for acute low back pain:

University of South Australia, Adelaide, South interpretation of the data; preparation, review, or a randomised controlled trial. Lancet. 2007;370

Australia, Australia (Moseley); University of Sydney approval of the manuscript; and decision to submit (9599):1638-1643. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(07)

at Royal North Shore Hospital, Pain Management the manuscript for publication. 61686-9

Research Institute, Sydney, New South Wales, Data Sharing Statement: See Supplement 3. 10. Machado LA, Maher CG, Herbert RD, Clare H,

Australia (Nicholas); Faculty of Health Sciences, The McAuley JH. The effectiveness of the McKenzie

University of Sydney, Sydney, New South Wales, Additional Contributions: The staff of primary care

practices in Sydney, Australia, recruited participants method in addition to first-line care for acute low

Australia (Refshauge); Centre for Education and back pain: a randomized controlled trial. BMC Med.

Research on Ageing, The University of Sydney, for the trial and were reimbursed per participant for

time spent on the study. Chris Maher, PhD, The 2010;8:10. doi:10.1186/1741-7015-8-10

Sydney, New South Wales, Australia (Blyth);

Arthritis Care UK National Primary Care Centre, University of Sydney, gave his advice on early 11. Eisenberg DM, Post DE, Davis RB, et al. Addition

Keele University, North Staffordshire, United versions of the manuscript. We acknowledge the of choice of complementary therapies to usual care

Kingdom (Main); Department of Health invaluable contribution of Garry Pearce, MBBS, MD, for acute low back pain: a randomized controlled

Professions, Macquarie University, Sydney, who died in 2017. Prof Maher and Dr Pearce were trial. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 2007;32(2):151-158.

New South Wales, Australia (Hush); Melanoma not financially compensated for their contributions. doi:10.1097/01.brs.0000252697.07214.65

Institute Australia, The University of Sydney, 12. Engers A, Jellema P, Wensing M,

Sydney, New South Wales, Australia (Lo); Institute REFERENCES van der Windt DA, Grol R, van Tulder MW. Individual

for Research and Medical Consultations, University 1. GBD 2016 Disease and Injury Incidence and patient education for low back pain. Cochrane

of Dammam, Dammam, Kingdom of Saudi Arabia Prevalence Collaborators. Global, regional, and Database Syst Rev. 2008;(1):CD004057. doi:10.

(Lo); Exercise Physiology, School of Medical national incidence, prevalence, and years lived with 1002/14651858.CD004057.pub3

Sciences, Faculty of Medicine, University of disability for 328 diseases and injuries for 195 13. Koes BW, van Tulder M, Lin CW, Macedo LG,

New South Wales, Sydney, New South Wales, countries, 1990-2016: a systematic analysis for the McAuley J, Maher C. An updated overview of

Australia (McAuley). Global Burden of Disease Study 2016. Lancet. 2017; clinical guidelines for the management of

Author Contributions: Drs Traeger and McAuley 390(10100):1211-1259. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(17) non-specific low back pain in primary care. Eur

had full access to all the data in the study and take 32154-2 Spine J. 2010;19(12):2075-2094. doi:10.1007/

responsibility for the integrity of the data and the 2. Deyo RA, Weinstein JN. Low back pain. N Engl J s00586-010-1502-y

accuracy of the data analysis. Med. 2001;344(5):363-370. doi:10.1056/ 14. Louw A, Zimney K, Puentedura EJ, Diener I.

Concept and design: Traeger, Lee, Hübscher, NEJM200102013440508 The efficacy of pain neuroscience education on

Moseley, Nicholas, Henschke, Refshauge, Blyth, 3. Hartvigsen J, Hancock MJ, Kongsted A, et al; musculoskeletal pain: a systematic review of the

Main, McAuley. Lancet Low Back Pain Series Working Group. What literature. Physiother Theory Pract. 2016;32(5):

Acquisition, analysis, or interpretation of data: low back pain is and why we need to pay attention. 332-355. doi:10.1080/09593985.2016.1194646

Traeger, Lee, Hübscher, Skinner, Moseley, Nicholas, Lancet. 2018;391(10137):2356-2367. doi:10.1016/

Henschke, Refshauge, Blyth, Hush, Lo, McAuley. 15. Traeger AC, Moseley GL, Hübscher M, et al. Pain

S0140-6736(18)30480-X education to prevent chronic low back pain: a study

Drafting of the manuscript: Traeger, Lee, Hübscher,

Skinner, Refshauge, Hush, McAuley. 4. Foster NE, Anema JR, Cherkin D, et al; Lancet protocol for a randomised controlled trial. BMJ Open.

Critical revision of the manuscript for important Low Back Pain Series Working Group. Prevention 2014;4(6):e005505. doi:10.1136/bmjopen-2014-

intellectual content: All authors. and treatment of low back pain: evidence, 005505

Statistical analysis: Traeger, Lee, Skinner, Lo, challenges, and promising directions. Lancet. 2018; 16. Butler DS, Moseley GL. Explain Pain. 2nd ed.

McAuley. 391(10137):2368-2383. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(18) Adelaide, South Australia: Noigroup Publications;

Obtained funding: Moseley, Nicholas, Refshauge, 30489-6 2013.

McAuley. 5. Buchbinder R, van Tulder M, Öberg B, et al; 17. Devilly GJ, Borkovec TD. Psychometric

Administrative, technical, or material support: Lancet Low Back Pain Series Working Group. Low properties of the credibility/expectancy

Traeger, Lee, Skinner, Nicholas, McAuley. back pain: a call for action. Lancet. 2018;391(10137): questionnaire. J Behav Ther Exp Psychiatry. 2000;

Supervision: Hübscher, Moseley, Nicholas, 2384-2388. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(18)30488-4 31(2):73-86. doi:10.1016/S0005-7916(00)00012-4

168 JAMA Neurology February 2019 Volume 76, Number 2 (Reprinted) jamaneurology.com

© 2018 American Medical Association. All rights reserved.

Downloaded From: https://jamanetwork.com/ on 09/01/2020

Effect of Intensive Patient Education on Pain Outcomes in Patients With Acute Low Back Pain Original Investigation Research

18. Traeger AC, Skinner IW, Hübscher M, et al. (STarT Back): a randomised controlled trial. Lancet. a comparison of what research supports and what

A randomized, placebo-controlled trial of patient 2011;378(9802):1560-1571. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736 guidelines recommend. Spine J. 2017;17(10):

education for acute low back pain (PREVENT Trial): (11)60937-9 1537-1546. doi:10.1016/j.spinee.2017.05.030

statistical analysis plan. Braz J Phys Ther. 2017;21(3): 22. National Institute for Health and Care 25. Traeger AC, Hübscher M, Henschke N,

219-223. doi:10.1016/j.bjpt.2017.04.005 Excellence (NICE). Clinical Guidelines. Low Back Moseley GL, Lee H, McAuley JH. Effect of primary

19. Lee H, Moseley GL, Hübscher M, et al. Pain and Sciatica in Over 16s: Assessment and care-based education on reassurance in patients

Understanding how pain education causes changes Management. London: National Institute for Health with acute low back pain: systematic review and

in pain and disability: protocol for a causal and Care Excellence; 2016. meta-analysis. JAMA Intern Med. 2015;175(5):

mediation analysis of the PREVENT trial. J Physiother. 23. Qaseem A, Wilt TJ, McLean RM, Forciea MA; 733-743. doi:10.1001/jamainternmed.2015.0217

2015;61(3):156. doi:10.1016/j.jphys.2015.03.004 Clinical Guidelines Committee of the American 26. Chou R. Reassuring patients about low back

20. Nicholas MK, Asghari A, Blyth FM. What do the College of Physicians. Noninvasive treatments for pain. JAMA Intern Med. 2015;175(5):743-744.

numbers mean? normative data in chronic pain acute, subacute, and chronic low back pain: doi:10.1001/jamainternmed.2015.0252

measures. Pain. 2008;134(1-2):158-173. doi:10.1016/ a clinical practice guideline from the American 27. Williams CM, Maher CG, Latimer J, et al.

j.pain.2007.04.007 College of Physicians. Ann Intern Med. 2017;166(7): Efficacy of paracetamol for acute low-back pain:

21. Hill JC, Whitehurst DG, Lewis M, et al. 514-530. doi:10.7326/M16-2367 a double-blind, randomised controlled trial. Lancet.

Comparison of stratified primary care management 24. Stevens ML, Lin CC, de Carvalho FA, Phan K, 2014;384(9954):1586-1596. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736

for low back pain with current best practice Koes B, Maher CG. Advice for acute low back pain: (14)60805-9

jamaneurology.com (Reprinted) JAMA Neurology February 2019 Volume 76, Number 2 169

© 2018 American Medical Association. All rights reserved.

Downloaded From: https://jamanetwork.com/ on 09/01/2020

You might also like

- Integrative Headache Medicine: An Evidence-Based Guide for CliniciansFrom EverandIntegrative Headache Medicine: An Evidence-Based Guide for CliniciansLauren R. NatbonyNo ratings yet

- The Science of Natural Healing (Transcript)From EverandThe Science of Natural Healing (Transcript)Rating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (7)

- MainDocument8 pagesMainLuis DavidNo ratings yet

- Research: Prognosis For Patients With Chronic Low Back Pain: Inception Cohort StudyDocument8 pagesResearch: Prognosis For Patients With Chronic Low Back Pain: Inception Cohort StudyOzy PutraNo ratings yet

- RIZZO Et Al 2018 Hipnose e Dor CrônicaDocument9 pagesRIZZO Et Al 2018 Hipnose e Dor CrônicaBOUGLEUX BOMJARDIM DA SILVA CARMONo ratings yet

- Comments Fritz Jama EBM2016Document1 pageComments Fritz Jama EBM2016Ju ChangNo ratings yet

- 337 FullDocument10 pages337 FullDaniel RojasNo ratings yet

- The Effectiveness and Safety of Manual Therapy On Pain and Disability in Older Persons With Chronic Low Back Pain: A Systematic ReviewDocument8 pagesThe Effectiveness and Safety of Manual Therapy On Pain and Disability in Older Persons With Chronic Low Back Pain: A Systematic ReviewCleyber SantosNo ratings yet

- Exercise in The Management of Chronic Back Pain: Thomas E. Dreisinger, PHD, FacsmDocument7 pagesExercise in The Management of Chronic Back Pain: Thomas E. Dreisinger, PHD, FacsmmazanNo ratings yet

- Joi 140178Document11 pagesJoi 140178holisNo ratings yet

- Nursing Interventions For Identifying and Managing Acute Dysphagia Are Effective For Improving Patient OutcomesDocument9 pagesNursing Interventions For Identifying and Managing Acute Dysphagia Are Effective For Improving Patient OutcomesawinsyNo ratings yet

- A Randomized Controlled Trial of Exercise and Manipulative Therapy For Cervicogenic HeadacheDocument9 pagesA Randomized Controlled Trial of Exercise and Manipulative Therapy For Cervicogenic Headachepaulina_810No ratings yet

- Low Back Pain 2018Document18 pagesLow Back Pain 2018Salazar Ángel100% (1)

- 12 Suppl - 4 S119Document9 pages12 Suppl - 4 S119Dr AliNo ratings yet

- Original Research Using Guided Imagery To Manage.25Document11 pagesOriginal Research Using Guided Imagery To Manage.25wilmaNo ratings yet

- Hancock 2005Document6 pagesHancock 2005Elizabeth VivancoNo ratings yet

- Does Mindfulness Improve Outcomes in Patients With Chronic PainDocument14 pagesDoes Mindfulness Improve Outcomes in Patients With Chronic Painiker1303No ratings yet

- The Treatment of Acute Low Back Pain - Bed Rest, Exercises, or Ordinary Activity?Document5 pagesThe Treatment of Acute Low Back Pain - Bed Rest, Exercises, or Ordinary Activity?Arya Maulana NugrohoNo ratings yet

- Iles, R Et Al. Telephone Coaching Can Increase Activity Levels For People With Non-Chronic Low Back PainDocument8 pagesIles, R Et Al. Telephone Coaching Can Increase Activity Levels For People With Non-Chronic Low Back PainDulce María AlanisNo ratings yet

- Diagnóstico y Manejo: LumbalgiaDocument10 pagesDiagnóstico y Manejo: LumbalgiaMoises OnofreNo ratings yet

- Low Back Pain Prognosis Structured Review of The LiteratureDocument6 pagesLow Back Pain Prognosis Structured Review of The Literaturec5rga5h2No ratings yet

- ptj1275Document12 pagesptj1275Taynah LopesNo ratings yet

- The Effectiveness of Exercise As A Treatment For Postnatal Depression: Study ProtocolDocument8 pagesThe Effectiveness of Exercise As A Treatment For Postnatal Depression: Study ProtocolsangaviNo ratings yet

- The Effect of DismenorhoeDocument18 pagesThe Effect of DismenorhoeNarmin FaisalNo ratings yet

- Aime201704040 M162367Document29 pagesAime201704040 M162367Thanh Phung PhamNo ratings yet

- Accepted Manuscript: The Spine JournalDocument36 pagesAccepted Manuscript: The Spine JournalRaihan AdamNo ratings yet

- Ludvig S Son 2015Document9 pagesLudvig S Son 2015christianFPTNo ratings yet

- 1 PDFDocument11 pages1 PDFTadea Yasinta100% (1)

- Standardized Vs Individualized Acupuncture For Chronic Back PainDocument8 pagesStandardized Vs Individualized Acupuncture For Chronic Back PainAHNo ratings yet

- Academic Emergency Medicine - 2022 - Broder - Guidelines For Reasonable and Appropriate Care in The Emergency Department 2Document36 pagesAcademic Emergency Medicine - 2022 - Broder - Guidelines For Reasonable and Appropriate Care in The Emergency Department 2Dr. Ricardo NegreteNo ratings yet

- Bai 2017Document4 pagesBai 2017kurnia fitriNo ratings yet

- Michaleff 2014Document9 pagesMichaleff 2014soylahijadeunvampiroNo ratings yet

- Pain Agitation DeliriumDocument10 pagesPain Agitation DeliriumMelati HasnailNo ratings yet

- Stretching Exercises Vs Manual Therapy in Treatment of Chronic Neck Pain: A Randomized, Controlled Cross-Over TrialDocument7 pagesStretching Exercises Vs Manual Therapy in Treatment of Chronic Neck Pain: A Randomized, Controlled Cross-Over TrialUli NurmaNo ratings yet

- Feldenkrais Method Empowers Adults With Chronic.4Document13 pagesFeldenkrais Method Empowers Adults With Chronic.4Yvette M Reyes100% (1)

- Effect of Active and Passive Distraction On Decreasing Pain Associated With Painful Medical Procedures Among School Aged ChildrenDocument11 pagesEffect of Active and Passive Distraction On Decreasing Pain Associated With Painful Medical Procedures Among School Aged ChildrenTadea YasintaNo ratings yet

- NIH Public Access: Author ManuscriptDocument24 pagesNIH Public Access: Author ManuscriptrenatanurulsNo ratings yet

- AINEsDocument13 pagesAINEsSebastian NamikazeNo ratings yet

- Effects of Balance Training Using A Virtual-Reality System in Older FallersDocument7 pagesEffects of Balance Training Using A Virtual-Reality System in Older FallersDaniel Eduardo GaeteNo ratings yet

- Research: The Prognosis of Acute and Persistent Low-Back Pain: A Meta-AnalysisDocument12 pagesResearch: The Prognosis of Acute and Persistent Low-Back Pain: A Meta-AnalysisDeivison Fellipe da Silva CâmaraNo ratings yet

- Adherence To A Stability Exercise Programme in PatDocument8 pagesAdherence To A Stability Exercise Programme in PatMirza Kurnia AngelitaNo ratings yet

- Copia de 09enero Sedacion Prot Vs No ProtDocument22 pagesCopia de 09enero Sedacion Prot Vs No ProtMartin LafuenteNo ratings yet

- Taddio Et Al.Document8 pagesTaddio Et Al.Maria GarabajiuNo ratings yet

- Review Article: Best Practice Management of Neck Pain in The Emergency Department (Part 6 of The Musculoskeletal Injuries Rapid Review Series)Document19 pagesReview Article: Best Practice Management of Neck Pain in The Emergency Department (Part 6 of The Musculoskeletal Injuries Rapid Review Series)Eduardo BarreraNo ratings yet

- Diagnosis Treatment of Back Pain MedicationsDocument41 pagesDiagnosis Treatment of Back Pain Medicationsrabin1994No ratings yet

- Ebn - MG CamposDocument5 pagesEbn - MG CamposLemuel Glenn BautistaNo ratings yet

- Chan, Clara (2017)Document8 pagesChan, Clara (2017)Rafael FontesNo ratings yet

- Naturopathic Care For Chronic Low Back PainDocument7 pagesNaturopathic Care For Chronic Low Back PainDr Siddharth SP YadavNo ratings yet

- Aime201704040 M162367Document29 pagesAime201704040 M162367Ziggy GonNo ratings yet

- Hasil Tugas ConsortDocument15 pagesHasil Tugas ConsortSelly AnggrainiNo ratings yet

- m02-aula-02-historia-natural-da-dor-cervicalDocument6 pagesm02-aula-02-historia-natural-da-dor-cervicalgguida0No ratings yet

- Dutch LBP Physiotherapy Guideline National PDFDocument29 pagesDutch LBP Physiotherapy Guideline National PDFyohanNo ratings yet

- Artigo Care in UCIDocument23 pagesArtigo Care in UCIJuan DiegoNo ratings yet

- Undergraduate Students Attitudes and Beliefs Relating To Pain ManagementDocument2 pagesUndergraduate Students Attitudes and Beliefs Relating To Pain ManagementJustine Ingrid O. FernandezNo ratings yet

- ACT One SessionDocument8 pagesACT One SessioncrrissttiNo ratings yet

- Synthesis PaperDocument10 pagesSynthesis Paperapi-485472556No ratings yet

- Interventions For The Prevention of Pain Associated With The Placement of Intrauterine Contraceptives: An Updated ReviewDocument14 pagesInterventions For The Prevention of Pain Associated With The Placement of Intrauterine Contraceptives: An Updated ReviewLeonardo Daniel MendesNo ratings yet

- Effectiveness of Mindfulness Meditation Vs Headache Education Rebecca WellsDocument12 pagesEffectiveness of Mindfulness Meditation Vs Headache Education Rebecca WellsYunita Christiani BiyangNo ratings yet

- Musculoskeletal Science and PracticeDocument11 pagesMusculoskeletal Science and PracticeAnii warikarNo ratings yet

- Comprehensive Pain Management in the Rehabilitation PatientFrom EverandComprehensive Pain Management in the Rehabilitation PatientAlexios Carayannopoulos DO, MPHNo ratings yet

- Agnes Nogueira Gossenheimer The Power of The PlaceboDocument8 pagesAgnes Nogueira Gossenheimer The Power of The PlacebosoylahijadeunvampiroNo ratings yet

- Jop 164 1181Document19 pagesJop 164 1181soylahijadeunvampiroNo ratings yet

- Applsci 13 00931Document13 pagesApplsci 13 00931soylahijadeunvampiroNo ratings yet

- 1 s2.0 S2589986423000448 MainDocument5 pages1 s2.0 S2589986423000448 MainsoylahijadeunvampiroNo ratings yet

- Menzel Et Al 2005 Temporal Nitric Oxide Dynamics in The Paranasal Sinuses During HummingDocument8 pagesMenzel Et Al 2005 Temporal Nitric Oxide Dynamics in The Paranasal Sinuses During HummingsoylahijadeunvampiroNo ratings yet

- JTCM 1 51Document6 pagesJTCM 1 51soylahijadeunvampiroNo ratings yet

- NEURCLINPRACT2017023598Document7 pagesNEURCLINPRACT2017023598soylahijadeunvampiroNo ratings yet

- Review Article: Acupuncture For Visceral Pain: Neural Substrates and Potential MechanismsDocument13 pagesReview Article: Acupuncture For Visceral Pain: Neural Substrates and Potential MechanismssoylahijadeunvampiroNo ratings yet

- Motor Points of Upper LimbDocument7 pagesMotor Points of Upper LimbsoylahijadeunvampiroNo ratings yet

- Rosenkranz 2016Document6 pagesRosenkranz 2016soylahijadeunvampiroNo ratings yet

- Downregulation of The Spinal NMDA Receptor NR2B Subunit During Electro-Acupuncture Relief of Chronic Visceral HyperalgesiaDocument10 pagesDownregulation of The Spinal NMDA Receptor NR2B Subunit During Electro-Acupuncture Relief of Chronic Visceral HyperalgesiasoylahijadeunvampiroNo ratings yet

- Ecam2019 1304152Document22 pagesEcam2019 1304152soylahijadeunvampiroNo ratings yet

- International Journal of PsychophysiologyDocument9 pagesInternational Journal of PsychophysiologysoylahijadeunvampiroNo ratings yet

- 1 s2.0 S0306452209015620 MainDocument8 pages1 s2.0 S0306452209015620 MainsoylahijadeunvampiroNo ratings yet

- Placebo, Belief, and Health. Cognitive-Emotional: Lars-GuknarDocument16 pagesPlacebo, Belief, and Health. Cognitive-Emotional: Lars-GuknarsoylahijadeunvampiroNo ratings yet

- Active Albuterol or Placebo, Sham Acupuncture, or No Intervention in AsthmaDocument8 pagesActive Albuterol or Placebo, Sham Acupuncture, or No Intervention in AsthmasoylahijadeunvampiroNo ratings yet

- Placebo Expectations Alter Detection of Somatic SensationsDocument10 pagesPlacebo Expectations Alter Detection of Somatic SensationssoylahijadeunvampiroNo ratings yet

- Where Is The Rhythm Generator For Emotional Breathing?: Yuri Masaoka, Masahiko Izumizaki, Ikuo HommaDocument11 pagesWhere Is The Rhythm Generator For Emotional Breathing?: Yuri Masaoka, Masahiko Izumizaki, Ikuo HommasoylahijadeunvampiroNo ratings yet

- The Placebo Response: An Important Part of Treatment: Steve Chaplin MrpharmsDocument4 pagesThe Placebo Response: An Important Part of Treatment: Steve Chaplin MrpharmssoylahijadeunvampiroNo ratings yet

- Neurotransmitter Systems Involved in Placebo and Nocebo Effects in Healthy Participants and Patients With Chronic Pain: A Systematic ReviewDocument13 pagesNeurotransmitter Systems Involved in Placebo and Nocebo Effects in Healthy Participants and Patients With Chronic Pain: A Systematic ReviewsoylahijadeunvampiroNo ratings yet

- Placebo Response in Clinical Randomized Trials of Analgesics in MigraineDocument4 pagesPlacebo Response in Clinical Randomized Trials of Analgesics in MigrainesoylahijadeunvampiroNo ratings yet

- Ejercicios Dolor CuelloDocument13 pagesEjercicios Dolor CuelloMaximiliano LabraNo ratings yet

- Personality Traits Identification Using Rough Sets Based Machine LearningDocument4 pagesPersonality Traits Identification Using Rough Sets Based Machine LearningsoylahijadeunvampiroNo ratings yet

- Protein Expression and PurificationDocument10 pagesProtein Expression and PurificationsoylahijadeunvampiroNo ratings yet

- Srep 18065Document10 pagesSrep 18065soylahijadeunvampiroNo ratings yet

- Positive Airway Pressure Therapy For Chronic Pain in Patients With Obstructive Sleep Apnea - A Systematic ReviewDocument9 pagesPositive Airway Pressure Therapy For Chronic Pain in Patients With Obstructive Sleep Apnea - A Systematic ReviewsoylahijadeunvampiroNo ratings yet

- Placebo Analgesia Induced by Social Observational Learning: Luana Colloca, Fabrizio BenedettiDocument7 pagesPlacebo Analgesia Induced by Social Observational Learning: Luana Colloca, Fabrizio BenedettisoylahijadeunvampiroNo ratings yet

- 3860 - International-Classification-Of-Orofacial-Pain-1st-Ed-Icop-Cha ICOP 1Document93 pages3860 - International-Classification-Of-Orofacial-Pain-1st-Ed-Icop-Cha ICOP 1Gerardo Eguia PastranaNo ratings yet

- Measuring patient expectancy in clinical trialsDocument10 pagesMeasuring patient expectancy in clinical trialssoylahijadeunvampiroNo ratings yet

- Profilins: Mimickers of Allergy or Relevant Allergens?: ReviewDocument14 pagesProfilins: Mimickers of Allergy or Relevant Allergens?: ReviewsoylahijadeunvampiroNo ratings yet

- Harry Guess, Linda Engel, Arthur Kleinman, John Kusek Science of The Placebo Toward An Interdisciplinanary Research Agenda Evidence-Based Medicine Workbks. 2002Document345 pagesHarry Guess, Linda Engel, Arthur Kleinman, John Kusek Science of The Placebo Toward An Interdisciplinanary Research Agenda Evidence-Based Medicine Workbks. 2002rockspirit02No ratings yet

- Journal Club - Ketamine + AUDDocument7 pagesJournal Club - Ketamine + AUDJasNo ratings yet

- Corticosteroid Injections: Glass Half-Full, Half - Empty or Full Then Empty?Document2 pagesCorticosteroid Injections: Glass Half-Full, Half - Empty or Full Then Empty?xavi5_5No ratings yet

- Piascledine CT 5536Document13 pagesPiascledine CT 5536Shahab EdalatianNo ratings yet

- Lonsurf Patient Brochure enDocument23 pagesLonsurf Patient Brochure ennaveen597No ratings yet

- E-Prac CAT # 02 - TestDocument30 pagesE-Prac CAT # 02 - TestUddalak Banerjee100% (1)

- B2 Reading ComprehensionDocument29 pagesB2 Reading ComprehensionTijana Doberšek Ex ŽivkovićNo ratings yet

- Repetition Following Amelioration in Homoeopathy A Randomized Placebo Controlled Pilot StudyDocument7 pagesRepetition Following Amelioration in Homoeopathy A Randomized Placebo Controlled Pilot StudyHomoeopathic PulseNo ratings yet

- Effectiveness of Treatment For Sudden Sensorineural Hearing LossDocument4 pagesEffectiveness of Treatment For Sudden Sensorineural Hearing Lossronaldyohanesf87No ratings yet

- Vichinsky Et Al.2019Document11 pagesVichinsky Et Al.2019Kuliah Semester 4No ratings yet

- The Ethics of PlaceboDocument5 pagesThe Ethics of Placebopsychforall100% (2)

- Digi T Vigilance TestDocument6 pagesDigi T Vigilance TestJillianne FrancoNo ratings yet

- Declaration of Helsinki: PreambleDocument6 pagesDeclaration of Helsinki: PreamblePrincess Alane MorenoNo ratings yet

- Grandjean 2000Document13 pagesGrandjean 2000Ivan VeriswanNo ratings yet

- 12 Science of EmbodimentDocument5 pages12 Science of EmbodimentfelipeNo ratings yet

- Reading The Factor: Of: Vocabulary Section Celebratiiap Genli SDocument23 pagesReading The Factor: Of: Vocabulary Section Celebratiiap Genli SDanieleAddanteNo ratings yet

- Intentional IgnoranceDocument41 pagesIntentional IgnoranceCat SkullNo ratings yet

- Bruce - Lipton - PDF Epigenetics Mindfulnes PDFDocument23 pagesBruce - Lipton - PDF Epigenetics Mindfulnes PDFSwami Mounamurti Saraswati I100% (14)

- The 4th Dimension of FitnessDocument6 pagesThe 4th Dimension of FitnessalmaformaNo ratings yet

- QuestionsDocument28 pagesQuestionsViswanathan NatarajanNo ratings yet

- Mefenamic Acid Public Assessment Report For Pediatric StudiesDocument17 pagesMefenamic Acid Public Assessment Report For Pediatric StudiesNyoman SuryadinataNo ratings yet

- Childhood Schizophrenia A Case of Treatment With Nicotinamide and NiacinDocument11 pagesChildhood Schizophrenia A Case of Treatment With Nicotinamide and NiacinJim BennyNo ratings yet

- The Expectation Effect by David RobsonDocument18 pagesThe Expectation Effect by David RobsonMáy Chiết Rót Hữu Thành100% (1)

- Alexander Technique and Feldenkrais Method: A CriticalDocument16 pagesAlexander Technique and Feldenkrais Method: A CriticalAna Carolina PetrusNo ratings yet

- Magnet Therapy For The Relief of Pain and in Ammation in Rheumatoid Arthritis (CAMBRA) : A Randomised Placebo-Controlled Crossover TrialDocument18 pagesMagnet Therapy For The Relief of Pain and in Ammation in Rheumatoid Arthritis (CAMBRA) : A Randomised Placebo-Controlled Crossover TrialAmr ElDisoukyNo ratings yet

- GS321 Mid OLDDocument94 pagesGS321 Mid OLDmkmh1422No ratings yet

- Dysmenorrhea Definition PDFDocument14 pagesDysmenorrhea Definition PDFYogi HermawanNo ratings yet

- Acupuncture Review and Analysis of Reports On Controlled Clinical Trials PDFDocument96 pagesAcupuncture Review and Analysis of Reports On Controlled Clinical Trials PDFPongsathat TreewisootNo ratings yet

- 26 Pycnogenol EbookDocument36 pages26 Pycnogenol EbookPredrag TerzicNo ratings yet

- Why Is Double-Blind Experiment Scientifically Valuable?: CCHU9021 Critical Thinking in Contemporary SocietyDocument27 pagesWhy Is Double-Blind Experiment Scientifically Valuable?: CCHU9021 Critical Thinking in Contemporary SocietyKaren TseNo ratings yet