Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Why Do Adolescents Self Harm

Uploaded by

Carlos Alejandro PinedaCopyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Why Do Adolescents Self Harm

Uploaded by

Carlos Alejandro PinedaCopyright:

Available Formats

Research Trends

Why Do Adolescents Self-Harm?

An Investigation of Motives in a Community Sample

Susan Rasmussen1, Keith Hawton2,

Sion Philpott-Morgan1, and Rory C. O’Connor3

This article is intended solely for the personal use of the individual user and is not to be disseminated broadly.

This document is copyrighted by the American Psychological Association or one of its allied publishers.

1

School of Psychological Sciences and Health, University of Strathclyde, Glasgow, UK

2

Centre for Suicide Research, University Department of Psychiatry, Warnford Hospital, Oxford, UK

3

Suicidal Behaviour Research Laboratory, Institute of Health and Wellbeing, College of Medical,

Veterinary and Life Sciences, University of Glasgow, Glasgow, UK

Abstract. Background: Given the high rates of self-harm among adolescents, recent research has focused on a better understanding of the

motives for the behavior. Aims: The present study had three aims: to investigate (a) which motives are most frequently endorsed by adolescents

who report self-harm; (b) whether motives reported at baseline predict repetition of self-harm over a 6-month period; and (c) whether self-harm

motives differ between boys and girls. Method: In all, 987 school pupils aged 14–16 years completed a lifestyle and coping questionnaire at two

time points 6 months apart that recorded self-harm and the associated motives. Results: The motive “to get relief from a terrible state of mind”

was the most commonly endorsed reason for self-harm (in boys and girls). Interpersonal reasons (e.g., “to frighten someone”) were least com-

monly endorsed. Regression analyses showed that adolescents who endorsed wanting to get relief from a terrible state of mind at baseline were

significantly more likely to repeat self-harm at follow-up than those adolescents who did not cite this motive. Conclusion: The results highlight

the complex nature of self-harm. They have implications for mental health provision in educational settings, especially in relation to encouraging

regulation of emotions and help-seeking.

Keywords: self-harm, reasons, motives, adolescent, repetition

Self-harm, defined as any type of intentional self-inju- has highlighted a number of risk (e.g., depression, hope-

ry or self-injurious behavior regardless of suicidal intent lessness, bullying, sexual/physical abuse, exposure to the

(Hawton et al., 2003), is a significant public health prob- self-harm of others) and protective factors (e.g., good

lem, especially among young people (Hawton, Saunders, problem-solving skills, peer relationships), which gives

& O’Connor, 2012). Adolescent self-harm also repre- insight into why some adolescents are more vulnerable to

sents one of the leading causes of hospital admission in self-harm than others (e.g., Fliege, Lee, Grimm, & Klapp,

young people in the UK (e.g., O’Loughlin & Sherwood, 2009; Gutierrez, 2006; Hawton et al., 2012; O’Connor

2005) and it is strongly associated with risk of future et al., 2012); however, our understanding of the motives

suicide (Goldacre & Hawton, 1985; Owens, Horrocks, behind these behaviors remains limited. A more detailed

& House, 2002). Whereas much research has highlight- appreciation is imperative for the development of inter-

ed the characteristics of those individuals who present ventions in this population (Hawton, Cole, O’Grady, &

to hospital following self-harm, there are relatively few Osborn, 1982).

large-scale studies of adolescent self-harm in the com-

munity (O’Connor, Rasmussen, Miles, & Hawton, 2009).

This is problematic as the majority of adolescents who Motives for Adolescent Self-Harm

self-harm do not present to clinical services (Groholt,

Ekeberg, Wichstrom, & Haldorsen, 2000; King, 1997; There is growing evidence that adolescents report multiple

Ystgaard et al., 2009). reasons for self-harm, and that the behavior is primarily an

Recent attempts to investigate the prevalence of ado- expression of intolerable psychological pain. For example,

lescent self-harm in the community in the UK have found Scoliers and colleagues (2009) investigated self-harm mo-

that approximately 13–14% of adolescents report having tives in a sample of 30,477 adolescents from six European

engaged in self-harm, with girls being significantly more countries by examining motives in terms of two overarching

likely to self-harm than boys (Hawton, Rodham, Evans, dimensions; one which represents externally directed rea-

& Weatherall, 2002; O’Connor et al., 2009; O’Connor, sons (e.g., “I wanted to find out if someone really loved me”)

Rasmussen, & Hawton, 2012, 2014). In addition, research and the other reflecting internally directed reasons (e.g., “I

Crisis 2016; Vol. 37(3):176–183 © 2016 Hogrefe Publishing

DOI: 10.1027/0227-5910/a000369

S. Rasmussen et al.: Why Do Adolescents Self-Harm? 177

wanted to get relief form a terrible state of mind”). The find- The Present Study

ings were clear: Adolescents were significantly more likely

to report wanting to die, escape, or obtain relief from their This investigation stems from a wider study of self-harm

situation, than they were to report wanting to change or in Northern Irish adolescents aged 14–16 years, the full

“manipulate” another person (Scoliers et al., 2009). details of which are described elsewhere (O’Connor, Ras-

This finding is consistent with research from adult pop- mussen, & Hawton, 2014). In the current paper, our prima-

ulations (Bancroft et al., 1979; Michel, Valach, & Waeber, ry aim was to examine the motives reported by adolescent

1994). For example, Holden, Kerr, Mendoca, and Velamoor boys and girls who had self-harmed. More specifically, we

(1998) examined the motives of 251 individuals (aged 14– wished to examine (a) whether these motives were more

63 years) who attended a crisis and short-term intervention likely to be intrapersonal or interpersonal, (b) whether dif-

unit of a psychiatric hospital and concluded that internally ferences existed in the motives chosen by girls when com-

directed motivations for suicidal behavior represent valid pared with boys, and (c) whether motives at baseline were

indicators of intent to die as well as overall suicide risk. In predictive of future self-harm over a 6-month follow-up

addition, research has also shown that self-harm is rarely period. This study is important as no research, to date, has

This article is intended solely for the personal use of the individual user and is not to be disseminated broadly.

the result of a single motive (e.g., to get attention), as most investigated whether motivations for past self-harm are

This document is copyrighted by the American Psychological Association or one of its allied publishers.

individuals identify multiple reasons/motives for the behav- predictive of self-harm over time in a community adoles-

ior (e.g., Hjelmeland et al., 2002; McAuliffe, Arensman, cent sample, and the findings could have potential utility in

Keeley, Corcoran, & Fitzgerald, 2007). terms of intervention and prevention efforts.

Theoretical work in the field also supports the idea that Consistent with Scoliers et al. (2009), we hypothesized

self-harm often serves multiple functions (Brown, Com- that young people would be significantly more likely to

tois, & Linehan, 2002; Haines, Williams, Brain, & Brown, endorse internally directed (intrapersonal) “cry of pain”

1995), and that it is important to distinguish between in- motives than externally directed “cry for help” (interper-

terpersonal and intrapersonal/automatic functions (Klon- sonal) motives (Hypothesis 1). Such a hypothesis is con-

sky & Glenn, 2009; Nock & Prinstein, 2004). In addition, sistent with recent theoretical developments that highlight

this work suggests that considering the functions of self- the role of feelings of defeat and entrapment (i.e., inter-

harm may be particularly relevant within a clinical context nal pain) in self-harm and suicidal behavior (e.g., O’Con-

as the functions may have implications not only for the nor, 2011; Williams, 2014). Second, given the ambiguous

assessment but also the treatment of self-harm (Nock & findings on gender differences, we also wished to exam-

Prinstein, 2005). These findings are unfortunately in stark ine whether boys and girls differed in the motives they

contrast to the view often expressed by professionals, who reported following self-harm. In a cross-sectional study,

perceive adolescent self-harm as being driven by a wish Scoliers et al. (2009) found that girls were more likely to

to manipulate others (see Hawton et al., 1982; Schnyder, report multiple motives than boys. We therefore hypothe-

Vlach, Bichsel, & Konrad, 1999). sized that girls would report more reasons for self-harm

than boys would (Hypothesis 2). Finally, building on the

evidence that psychological pain is particularly associated

Gender Differences with self-harm, we also predicted that those adolescents

who reported intrapersonal motives for self-harm at base-

While research into adolescent self-harm shows clear dif- line would be significantly more likely to repeat self-harm

ferences in prevalence rates between boys and girls, with over the follow-up period than those individuals who did

girls being significantly more likely to self-harm than boys not report intrapersonal reasons at baseline (Hypothesis 3).

(Hawton & Harris, 2008; Madge et al., 2008; O’Connor et

al., 2009), evidence for the existence of gender differenc-

es in motivation is equivocal. On the one hand, Scoliers

et al. (2009) found that girls reported significantly more

motives for their self-harm than boys did, and this differ- Method

ence held for both intrapersonal and interpersonal motives.

These findings could possibly be interpreted as girls hav- Sample

ing greater insight into the complexity of the motivations

or simply that they are generally more emotionally literate The sample included 987 school pupils aged 14–16 years

or willing to admit to diverse motives. By contrast, how- (mean age 14.7 years, SD = .60). There were 423 boys

ever, Hjelmeland and colleagues (2002) and Skögman and (43%) and 564 girls, with 97% of the sample being White.

Öjehagen (2003) found no significant gender differences They were a subsample of 3,596 pupils who completed

in self-reported motivations for self-harm (although it is the Northern Ireland Lifestyle and Coping Survey (O’Con-

worth bearing in mind that most of the patients in both nor et al., 2014). The subsample represents all participants

of the latter studies were adults). Given the gender differ- who completed the survey at two time points (time one

ences in self-harm rates, and the potential differences in [T1] and time two [T2] 6 months later). In the original sur-

motives for self-harm, we thought it was important to look vey, a representative sample of all schools in Northern Ire-

again at gender within the current study. To allow compa- land agreed to take part (n = 28) and although all schools

rability with other adolescent studies, we chose to employ were invited to take part in the 6-month follow-up, only 16

the same methodology as Scoliers et al. (2009). out of the 28 schools agreed. The present study is based

© 2016 Hogrefe Publishing Crisis 2016; Vol. 37(3):176–183

178 S. Rasmussen et al.: Why Do Adolescents Self-Harm?

on responses from pupils in these 16 schools. A compari- “I wanted to frighten someone,” “I wanted to get my own

son of the schools that participated in both the T1 and T2 back on someone,” “I wanted to get relief form a terrible

parts of the study showed that pupils who took part in both state of mind,” “I wanted to find out if someone really

parts of the study were significantly more likely to be from loved me,” and “I wanted to get some attention” (derived

the grammar rather than the secondary school sector, χ2(1, from Bancroft et al., 1979). At follow-up 6 months later,

n = 3,596) = 5.71, p < .02. In addition, significantly few- respondents were asked whether they had self-harmed

er schools with more than 17% of pupils eligible for free since they first completed the survey.

school meals agreed to participate in the follow-up, χ2(1, Ethical approval was obtained from the Department of

n = 3,596) = 101.48, p < .001. There was no difference Psychology Ethics Committee at the University of Stirling.

based on the location of the school; urban versus rural, Parents were informed of the study by letter and asked to

χ2(1, n = 3,596) = .62, ns. Finally, when comparing the notify the school if they did not want their child to par-

original sample (n = 35,960) with the subsample included ticipate. On the day of participation, pupils were given

in the following analyses (n = 987) we did not find any the choice of opting out and not participating. The survey

difference in self-harm rate, χ2(1, n = 3,520) = 1.76, ns. was administered in a school assembly hall or classroom

This article is intended solely for the personal use of the individual user and is not to be disseminated broadly.

The follow-up response rate within schools varied setting, and each pupil was provided with a sealed, anon-

This document is copyrighted by the American Psychological Association or one of its allied publishers.

between 19 and 79%.Therefore, to determine whether ymous envelope in which to return their questionnaire.

the young people who took part in the follow-up survey All pupils were given a debriefing sheet containing infor-

differed from those who declined, we conducted further mation about support organizations (e.g., helplines). An

analysis. This demonstrated that those young people who anonymous and confidential code was employed to link

reported self-harm at T1 were less likely to complete the the pupils’ responses between the two time points. All data

follow-up questionnaire than those young people who did were collected in 2009.

not report self-harm at T1, χ2(1, n = 2,235) = 7.46, p < .05;

however, they did not differ in terms of the motives provid-

ed for self-harm at T1. Statistical Analyses

A series of univariate logistic regression analyses and chi-

Measures and Procedure square tests were conducted to test the association between

self-harm and associated variables and to determine entry

All participants completed the Northern Ireland Lifestyle into the multivariate analyses. In the univariate logistic

and Coping Survey in school. This was adapted from the regression analyses, to adjust for potential clustering ef-

Child and Adolescent Self-Harm in Europe (CASE) Life- fects, the Huber–White sandwich estimator method using

style and Coping Questionnaire (Hawton et al., 2002; logistic regression with school as a clustering variable was

Madge et al., 2008). They also completed a brief version of used. Within the multivariate logistic regression analyses,

standard errors were again adjusted for within-school clus-

the survey 6 months later. The original questionnaire was

tering. All analyses were conducted using SPSS (version

developed in collaboration with experts in school-based

21). For comparison purposes, we chose to report the data

studies and underwent extensive piloting in schools and an

without controlling for depression and anxiety as this has

adolescent psychiatric unit and has already been admin-

not been done in previous research using the same meth-

istered in eight countries (England, Republic of Ireland,

odology (e.g., Madge et al., 2008; Scoliers et al., 2009);

Scotland, The Netherlands, Belgium, Norway, Hungary,

however, separate analyses were conducted that controlled

and Australia). We only report on those questions pertinent

for these variables and this did not affect the outcomes.

to the present study here (see O’Connor et al. 2014 for

full details of the procedure and measures included in the

Northern Ireland Lifestyle and Coping Survey). As part of

the survey, the young people were asked to answer ques-

tions on self-harm. Self-harm (at baseline) was recorded Results

if an adolescent responded yes to the following question

“Have you ever deliberately taken an overdose (e.g., of Self-Harm Motives at Baseline

pills or other medication) or tried to harm yourself in some

other way (such as cut yourself)?” While this methodology At baseline, 8.9% (n = 88) of the 987 respondents (564

does include a description of the act in terms of method girls and 423 boys) reported at least one episode of self-

used, for the current analyses we did not use the descrip- harm in their lifetime. Girls were almost 2.5 times (OR =

tion to classify the act as self-harm because excluding 2.43; 95% CI = 1.472–4.002) more likely to report self-

those who chose not to write a description might yield an harm than boys were (11.8% [66/558] vs. 5.2% [22/420],

underestimate of prevalence as some respondents deemed respectively). “Wanting to get relief from a terrible state

describing the act as too personal and painful. of mind” was the most commonly reported motive by the

In addition, respondents were asked to endorse if their young people (62.5%). “Wanting to frighten someone”

most recent self-harm episode was explained by any of the (14.8%), “wanting to get their own back on someone”

following motives: “I wanted to show how desperate I was (10.2%), and “wanting to get some attention” (12.5%)

feeling,” “I wanted to die,” “I wanted to punish myself,” were the least commonly reported (see Table 1). Based on

Crisis 2016; Vol. 37(3):176–183 © 2016 Hogrefe Publishing

S. Rasmussen et al.: Why Do Adolescents Self-Harm? 179

the classification scheme of Scoliers et al. (2009), 79.5% boys did not differ in how frequently they reported multi-

of those who had self-harmed reported at least one intrap- ple motives (54.5% and 59.1%, respectively, χ2 = 1.82, df =

ersonal motive, 40.9% reported at least one intrapersonal 1, 14; p = ns). See Table 1 for a breakdown of the motives

motive, and 31.8% reported at least one intrapersonal to- cited by gender.

gether with one interpersonal motive.

Predicting Repeat Self-Harm

Gender Differences in Baseline Motives

for Self-Harm During the 6-month follow-up period, 26.1% (n = 23) of

those who self-harmed at baseline reported having self-

More boys than girls reported wanting to frighten someone harmed again (four boys and 19 girls). Univariate logistic

(χ2 = 18.90, df = 1, 14; p < .05), and significantly more girls regression was used to determine which motives cited by

than boys reported wanting to die (χ2 = 3.79, df = 1, 14; those who engaged in self-harm at baseline predicted re-

This article is intended solely for the personal use of the individual user and is not to be disseminated broadly.

p < .05). Additionally, more boys than girls reported at peat self-harm in the subsequent 6-month period. These

This document is copyrighted by the American Psychological Association or one of its allied publishers.

least one cry for help motive (59.1% and 34.8%, respec- analyses revealed that the motives “I wanted to get relief

tively, χ2 = 4.01, df = 1, 14; p < .05), but there was no from a terrible state of mind” (intrapersonal) and “I want-

significant difference with respect to intrapersonal motives ed to find out whether someone really loved me” (inter-

(χ2 = .84, df = 1, 14; p = ns). personal) were independently associated with repeat self-

About half of those who self-harmed (55.6%) reported harm (see Table 2). Reporting a wish to die at baseline was

more than one self-harm motive (n = 49), but girls and not predictive of further self-harm during the follow-up.

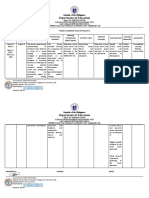

Table 1. Motives given for most recent episode of self-harm, by gender (n = 66 girls, 22 boys)

Motive Girls N N (%) Boys N N (%) Total %

To show how desperate I was feeling 13 19.7 6 27.3 21.6

To die 28 42.4 5 22.7 37.5

To punish myself 24 36.4 6 27.3 34.1

To frighten someone 6 9.1 7 31.8 14.8

To get my own back on someone 5 7.5 4 18.2 10.2

To get relief from a terrible state of mind 44 66.7 11 50.0 62.5

To find out whether someone really loved me 12 18.2 6 27.3 20.5

To get some attention 5 10.6 4 18.2 12.5

Citing at least one type of motive:

Intrapersonal 54 81.8 16 72.7 79.5

Interpersonal 23 42.4 13 59.4 40.9

Note. Similar to Scoliers et al. (2009), Motives 1, 4, 5, 7, and 8 are categorized as interpersonal, while Motives 2, 3, and 6 are categorized as intraper-

sonal reasons.

Table 2. Univariate logistic regression analyses of motives predicting repeat self-harm at Time 2 (at 6 months)

OR 95% CI p

To show how desperate I was feeling 0.350 0.04–2.95 .29

To die 0.469 0.11–1.99 .26

To punish myself 1.434 0.540–3.82 .43

To frighten someone 0.620 0.06–7.03 .67

To get my own back on someone 0.918 0.07–12.87 .95

To get relief from a terrible state of mind 14.448 1.43–145.71 .01

To find out whether someone really loved me 0.064 0.00–0.99 .03

To get some attention 0.425 0.03–5.31 .47

Citing at least one type of motive:

Intrapersonal N/A N/A .00

Interpersonal 0.398 0.08–1.93 .21

© 2016 Hogrefe Publishing Crisis 2016; Vol. 37(3):176–183

180 S. Rasmussen et al.: Why Do Adolescents Self-Harm?

Table 3. Multivariate associations of most recent episode of self-harm at baseline with repeat self-harm

OR 95% CI p

To get relief from a terrible state of mind 11.194 1.383–90.595 .024

To find out whether someone really loved me 0.099 0.012–0.843 .034

Univariate logistic regression was also used to deter- intention to die has been expressed or not is misleading

mine whether citing intrapersonal or interpersonal motives (Loughrey & Kerr, 1989).

at baseline predicted repeat self-harm in the subsequent From a theoretical point of view, our findings lend sup-

6-month period. Only intrapersonal responses were found port to research that has argued for a need to distinguish

to have a significant relationship with repeat self-harm (p < between different functional reasons for engaging in self-

.005). As there were no cases of repeat self-harm where the harm. For example, Nock and Prinstein (2004) proposed

young person did not cite at least one intrapersonal motive, four primary functions that fit along two dichotomous

This article is intended solely for the personal use of the individual user and is not to be disseminated broadly.

This document is copyrighted by the American Psychological Association or one of its allied publishers.

the odds ratio could not be calculated. dimensions of automatic versus social behavior and re-

Next, the two self-harm motives that emerged from inforcement that is either positive or negative. While the

the univariate analyses (i.e., “I wanted to get relief from a measure of motives included in our study does not allow for

terrible state of mind” and “I wanted to find out whether a full evaluation according to this framework, our findings

someone really loved me”) were entered into multivariate certainly map onto the distinction between social/interper-

regression analyses (see Table 3). Adolescents who cited sonal and intrapersonal/automatic behaviors. More specif-

“I wanted to get relief from a terrible state of mind” as a ically, our findings are consistent with functional research

motive were more than 17 times more likely (OR = 17.77, that suggests that the most frequently endorsed function

95% CI = 1.63–190.70) to report self-harm at the 6-month among adolescents is to reduce negative emotions (auto-

follow-up period (controlling for the other motive). By matic negative reinforcement; Nock & Prinstein, 2004).

contrast, those who cited “I wanted to find out whether In support of the second hypothesis, we found evi-

someone really loved me” as a motive at baseline were dence of significant gender differences, with girls being

significantly less likely (OR = 0.047, 95% CI = .004–.569) more likely to report “wanting to die,” and boys being

to repeat self-harm (controlling for the other motives). more likely to endorse wanting “to frighten someone.”

While these reasons were the most infrequent motives

reported by both boys and girls more generally, the gen-

der difference is similar to findings by Laye-Gindhu and

Schonert-Reichl (2005) that boys more frequently reported

Discussion self-harming in order to communicate with others. Sim-

ilarly, Lloyd-Richardson, Perrine, Dierker, and Kelley

This school-based study addressed three research aims (2007) found that boys were more likely than girls to ex-

and three associated specific hypotheses. First, in support press wanting to make others angry, while girls were more

of Hypothesis 1, we found clear evidence that intraper- likely than boys to want to punish themselves. It is possi-

sonal self-harm motives were more likely to be endorsed ble that these gender differences are related to differences

by the adolescents than interpersonal motives. However, it in socialization patterns, with girls being more likely to

is worth noting that over half of the adolescents reported direct their feelings inward, whereas boys are more like-

multiple motives, with “I wanted to get relief from a ter- ly to direct their distress outwards (Crick & Zahn-Waxler,

rible state of mind” being the most frequently endorsed 2003; Parker et al., 1998). This suggestion may also help

motive by both boys and girls. This is in keeping with to explain the gender difference in intention to die, as we

previous research in adolescent samples from England found girls were more likely than boys to report wishing

(Hawton et al., 2002), Scotland (O’Connor et al., 2009), to die. Overall, such findings support the conclusion by

Continental Europe (Scoliers et al., 2009), and studies of Laye-Gindhu and Schonert-Reichl (2005) that research on

both adolescents (Hawton et al, 1982) and adults present- self-harm should always take into account differences be-

ing to hospital following self-harm (Bancroft et al., 1979; tween boys and girls.

Hjelmeland et al., 2002; Schnyder, Valach, Bichsel, & Finally, we were specifically interested in examining

Michel, 1999). It is also consistent with previous research whether self-harm motives at baseline predicted future

that has suggested that it is likely that self-harm serves self-harm, 6 months following baseline. To this end, the

several functions concurrently (Suyemoto, 1998), and analyses showed that adolescents who reported self-harm-

therefore the complexity of self-harm must not be under- ing to “get relief from a terrible state of mind” were sig-

estimated (Skegg, 2005). Importantly, while the behavior nificantly more likely to repeat self-harm, while those who

may have some communicative element, the overarching reported self-harming to “find out whether someone real-

theme of the behavior in adolescents is related to emotion- ly loved me” were significantly less likely to repeat self-

al pain. The present findings reinforce the notion that for harm. This finding supports our hypothesis (Hypothesis 3)

the majority of young people self-harm is not primarily a and is consonant with earlier research that has suggested

manipulative act. They also illustrate that to simply con- that more intense emotions may be implicated in greater

sider the seriousness of a behavior in relation to whether emotional dysregulation, which, in turn, increases the risk

Crisis 2016; Vol. 37(3):176–183 © 2016 Hogrefe Publishing

S. Rasmussen et al.: Why Do Adolescents Self-Harm? 181

of self-harm (Gratz, 2006). However, this finding is at odds ple who did not report self-harm at T1, which could have

with Hjelmeland et al. (1998), who reported that motives led to a bias in the final sample composition. We therefore

for self-harm did not predict repetition of self-harming be- acknowledge that reliance on self-reported behavior only

havior in a European sample of 776 self-harming individu- is a limitation that could have resulted in an underestima-

als aged 15+ who took part in the WHO/Euro Multicentre tion of the rates of self-harm. We also recognize that both

Study on Parasuicide. Crucially, though, this latter study substance use and self-injurious acts are covered within

focused largely on adults (the majority of participants were our self-harm question. While these behaviors are often

aged 30–59 years) who presented to hospital following a discussed separately in the literature, in studies where the

self-harm episode (primarily following an overdose). We young people’s answer to this question has been compared

believe the prospective element of this study is important with a description of the self-harm act, the overwhelming

because it highlights two key motives that ought to be tak- majority of the acts are of self-harm. In addition, as the

en into consideration when assessing risk of future self- study involved a standardized list of self-harm motives it

harm in community-based, school-attending adolescents. precluded respondents generating any additional motives,

and the format did not allow us to measure the degree of

This article is intended solely for the personal use of the individual user and is not to be disseminated broadly.

wish to die. Given the variation in extent of intent to die

This document is copyrighted by the American Psychological Association or one of its allied publishers.

Implications (Harriss, Hawton, & Zahl, 2005), this may explain why

we did not find that reporting a wish to die at T1 was pre-

Understanding the motives that underpin self-harm in dictive of self-harm at follow-up. Furthermore, this list is

young people is vital to the development of appropriate not exhaustive, and does not, for example, include motives

intervention and treatment programs. Research has shown such as lack of social connectedness or a wish to belong,

that young people often do not seek help before self-harm- which have been highlighted elsewhere as being important

ing (Hargus, Hawton, & Rodham, 2009; Ystgaard et al., interpersonal factors related to adolescent self-harm (e.g.,

2009), which is a concern given our finding that the most Kaminski et al., 2010). However, we believe that the utility

frequently endorsed reason for self-harm in our study was of administering a standardized questionnaire outweighs

to get relief from a terrible state of mind. This finding mir- the limitations as it allows for direct comparison across

rors what has been reported elsewhere (Boergers, Spririto, different studies and countries. Given our limited sample

& Donaldson, 1998; Hawton et al., 1982; Rodham, Haw- size, unlike Scoliers et al. we were unable to explore dif-

ton, & Evans, 2004). What is more, those young people ferences in motives in younger versus older adolescents.

who reported self-harming as a result of psychological Thus, it is possible that further gender differences may

pain were 17 times more likely to repeat self-harm over the have been evident if our sample had been amenable to fur-

6-month follow-up period. Given the gender differences in ther analysis by age.

motives, we also believe that there is value in considering

whether interventions and treatments to reduce/manage

self-harm should be tailored separately for girls and boys.

An additional challenge is how to encourage young peo- Conclusion

ple to seek help earlier and how to determine whether the

pattern of help-seeking varies as a function of self-harm The findings of this study highlight the utility of examining

motives. The findings also suggest that personal and social the motives underpinning adolescent self-harm. In particu-

development efforts should usefully be aimed at promot- lar, they point to specific motives that predicted self-harm

ing emotional regulation skills and developing effective repetition over 6 months, which ought to be considered

methods for dealing with stress and communication. when assessing risk of self-harm repetition. Clearly, an

enhanced understanding of the motives behind self-harm

can play a valuable role in the prevention of further self-

Limitations and Future Research harm through the development of appropriate treatment or

coping strategies. Furthermore, the results highlight the

Although these findings offer additional insights regarding complexity of the motives underpinning self-harm, the

the motives for adolescent self-harm and therefore contrib- fact that the motives are many, and that efforts to tackle

ute to our understanding of adolescent self-harm more gen- adolescent self-harm need to be made with recognition of

erally, they must be interpreted in the light of some limita- this complexity.

tions. First, although the study sample was relatively large,

the proportion of adolescents who reported self-harm at

baseline was modest (8.9%; n = 88) and the number of Acknowledgments

people who self-harmed between T1 and T2 was small (n =

23). Although the odds ratio in the predictive analyses for The study was funded by the Department of Health, Social

“I wanted to get relief from a terrible state of mind” is im- Services and Public Safety (NI) and supported by the De-

pressive, we would urge caution given that the confidence partment of Education (NI). KH is a National Institute for

intervals are also large. Similarly, it is worth noting that Health Research (England) Senior Investigator and is also

the follow-up response rate for those young people who supported by Oxford Health NHS Foundation Trust.

reported self-harm at T1 was lower than for young peo-

© 2016 Hogrefe Publishing Crisis 2016; Vol. 37(3):176–183

182 S. Rasmussen et al.: Why Do Adolescents Self-Harm?

References Holden, R. R., Kerr, P. S., Mendonca, J. D., & Velamoor, V. R.

(1998). Are some motives more linked to suicide proneness

than others? Journal of Clinical Psychology, 54, 569–576.

Bancroft, J., Hawton, K., Simkin, S., Kingston, B., Cumming,

Kaminski, J. W., Puddy, R. W., Hall, D. M., Cashman, S. Y., Cros-

C., & Whitwell, D. (1979). The reasons people give for tak-

by, A. E., & Ortega, L. A. G. (2010). The relative influence

ing overdoses: A further inquiry. British Journal of Medical

of different domains of social connectedness on self-directed

Psychology, 52, 353–365.

violence in adolescence. Journal of Youth and Adolescence,

Boergers, J., Spirito, A., & Donaldson, D. (1998). Reasons for

adolescent suicide attempts: Associations with psychological 39, 460–473.

functioning. Journal of the American Academy of Child and King, C. A. (1997). Suicidal behavior in adolescence. In R. W.

Adolescent Psychiatry, 37, 1287–1293. Maris, M. M. Silverman, & S. S. Canetto (Eds.), Review of

Brown, M., Comtois, K., & Linehan, M. (2002). Reasons for suicidology (pp. 61–95). New York, NY: Guilford.

suicide attempts and nonsuicidal self-injury in women with Klonsky, E. D., & Glenn, C. R. (2009). Assessing the functions

borderline personality disorder. Journal of Abnormal Psy- of non-suicidal self-injury: Psychometric properties of the

chology, 111, 198–202. inventory of statements about self-injury (ISAS). Journal of

Crick, N. R., & Zahn-Waxler, C. (2003). The development of Psychopathology and Behavioural Assessment, 31, 215–219.

Laye-Gindhu, A., & Schonert-Reichl, K. A. (2005). Nonsuicidal

This article is intended solely for the personal use of the individual user and is not to be disseminated broadly.

psychopathology in females and males: Current progress and

self-harm among community adolescents: Understanding the

This document is copyrighted by the American Psychological Association or one of its allied publishers.

future challenges. Development and Psychopathology, 15,

719–742. “Whats” and “Whys” of self-harm. Journal of Youth and Ad-

Fliege, H., Lee, J-R., Grimm, A., & Klapp, B. F. (2009). Risk olescence, 34, 447–457.

factors and correlates of deliberate self-harm: A systematic Lloyd-Richardson, E. E., Perrine, N., Dierker, L., & Kelley, M. L.

review. Journal of Psychosomatic Research, 66, 477–493. (2007). Characteristics and functions of nonsuicidal self-in-

Goldacre, M., & Hawton, K. (1985). Repetition of self-poison- jury in a community sample of adolescents. Psychological

ing and subsequent death in adolescents who take overdoses. Medicine, 37, 1183–1192.

British Journal of Psychiatry, 146, 395–398. Loughrey, G., & Kerr, A. (1989). Motivation in deliberate self-

Gratz, L. (2006). Risk factors for and functions of deliberate self- harm. The Ulster Medical Journal, 58, 46–50.

harm: An empirical and conceptual review. Clinical Psycho- Madge, N., Hewitt, A., Hawton, K., De Wilde, E. J., Corcoran,

logy Review, 27, 236–239. P., Fekete, S., … Ystgaard, M. (2008). Deliberate self-harm

Groholt, B., Ekeberg, O., Wichstrom, L., & Haldorsen, T. (2000). within an international community sample of young people:

Young suicide attempters: A comparison between a clinical Comparative findings from the child and adolescent self-

and an epidemiological sample. Journal of the American harm in Europe (CASE) study. Journal of Child Psychology

Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry, 39, 868–875. and Psychiatry, 49, 667–677.

Gutierrez, P. M. (2006). Integratively assessing risk and protective McAuliffe, C., Arensman, E., Keeley, H. S., Corcoran, P., & Fitz-

factors for adolescent suicide. Suicide and Life-Threatening gerald, A. P. (2007). Motives and suicide intent underlying

Behavior, 36, 129–135. hospital treated deliberate self-harm and their association

Haines, J., Williams, C. L., Brain, K. L., & Wilson, G. V. (1995). with repetition. Suicide and Life-Threatening Behavior, 37,

The psychophysiology of self-mutilation. Journal of Abnor- 397–408.

mal Psychology, 104, 471–489. Michel, K., Valach, L., & Waeber, V. (1994). Understanding de-

Hargus, E., Hawton, K., & Rodham, K. (2009). Distinguishing liberate self-harm: The patients’ views. Crisis, 15, 172–178.

between subgroups of adolescents who self-harm. Suicide Nock, M. K., & Prinstein, M. J. (2004). A functional approach to

and Life-Threatening Behavior, 39, 518–537. the assessment of self-mutilative behavior. Journal of Con-

Harriss, L., Hawton, K., & Zahl, D. (2005). Value of measuring sulting and Clinical Psychology, 72, 885–890.

suicidal intent in the assessment of people attending hospi- Nock, M. K., & Prinstein, M. J. (2005). Contextual features and

tal following self-poisoning or self-injury. British Journal of behavioral functions of self-mutilation among adolescents.

Psychiatry, 186, 60–66. Journal of Abnormal Psychology, 114, 140–146.

Hawton, K., Cole, D., O’Grady, J., & Osborn, M. (1982). Moti- O’Connor, R. C. (2011). Towards an integrated motivational-vo-

vational aspects of deliberate self poisoning in adolescents. litional of suicidal behaviour. In R. O’Connor, S. Platt, & J.

British Journal of Psychiatry, 141, 286–291. Gordon (Eds.), International handbook of suicide preven-

Hawton, K., & Harris, L. (2008). Deliberate self-harm by under tion: research, policy and practice (pp. 181–198). Chiches-

15 year olds: Characteristics, trends and outcomes. Journal ter, UK: Wiley Blackwell.

of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 49, 441–448. O’Connor, R. C., Rasmussen, S., & Hawton, K. (2012). Distin-

Hawton, K., Harriss, L., Hall, S., Simkin, S., Bale, E., & Bond, A. guishing adolescents who think about self-harm from those

(2003). Deliberate self-harm in Oxford, 1990–2000: A time who engage in self-harm. British Journal of Psychiatry, 200,

of change in patient characteristics. Psychological Medicine, 330–335.

6, 987–995. O’Connor, R. C., Rasmussen, S., & Hawton, K. (2014). Adoles-

Hawton, K., Rodham, K., Evans, E., & Weatherall, R. (2002). cent self-harm: A school-based study in Northern Ireland.

Deliberate self-harm in adolescents: Self-report survey in Journal of Affective Disorders, 159, 46–52.

schools in England. British Medical Journal, 325, 1207– O’Connor, R. C., Rasmussen, S., Miles, J., & Hawton, K. (2009).

1211. Self-harm in adolescents: Self-report survey in schools in

Hawton, K., Saunders, K. E. A., & O’Connor, R. C. (2012). Self- Scotland. British Journal of Psychiatry, 194, 68–72.

harm and suicide in adolescents. The Lancet, 379, 2373– O’Louglin, S., & Sherwood, J. (2005). A 20-year review of trends

2382. in deliberate self-harm in a British town, 1981-2000. Social

Hjelmeland, H., Hawton, K., Nordvik, H., Bille-Brahe, U., De Psychiatry and Psychiatric Epidemiology, 40, 446–453.

Leo, D., Fekete, S., … Wasserman, D. (2002). Why people Owens, D., Horrocks, J., & House, A. (2002). Fatal and non-fatal

engage in parasuicide: A cross-cultural study of intentions. repetition of self-harm. Systematic review. British Journal of

Suicide and Life-Threatening Behavior, 32, 380–393. Psychiatry, 181, 193–199.

Hjelmeland, H., Stiles, T. C., Bille-Brahe, U., Ostamo, A., Ren- Parker, G., Roy, K., Wilhelm, K., Austin, M., Mitchell, P., & Had-

berg, E. S., & Wasserman, D. (1998). Parasuicide: The value zi-Pavlovic, D. (1998). “Acting out” and “acting in” as be-

of suicidal intent and various motives as predictors of future havioural responses to stress: A qualitative and quantitative

suicidal behaviour. Archives of Suicide Research, 4, 209–225. study. Journal of Personality Disorders, 12, 338–350.

Crisis 2016; Vol. 37(3):176–183 © 2016 Hogrefe Publishing

S. Rasmussen et al.: Why Do Adolescents Self-Harm? 183

Rodham, K., Hawton, K., & Evans, E. (2004). Reasons for delib- About the authors

erate self-harm: Comparison of self-poisoners and self-cut-

ters in a community sample of adolescents. Journal of the Susan Rasmussen is a chartered health psychologist and senior

American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry, 43, lecturer at the University of Strathclyde, UK. She is an affiliate

1–8. member of the Suicidal Behaviour Research Laboratory, Univer-

Schnyder, U., Valach, L., Bichsel, K., & Michel, K. (1999). At- sity of Glasgow, UK. Her interest lies in the testing of theoretical

tempted suicide − do we understand the patients’ reasons? models to explain risk and protective factors implicated in sui-

General Hospital Psychiatry, 21, 62–69. cide/self-harm.

Scoliers, G., Portzky, G., Madge, N., Hewitt, A., Hawton, K.,

de Wilde, E. J., & van Heeringen, K. (2009). Reasons for Keith Hawton, DSc, FMedSci, is Professor of Psychiatry at

adolescent deliberate self-harm: A cry of pain and/or a cry Oxford University Department of Psychiatry, UK, where he is

for help? Findings from the Child & Adolescent Self-Harm Director of the Centre for Suicide Research. His research en-

in Europe (CASE) Study. Social Psychiatry and Psychiatric compasses epidemiology, causes, treatment and prevention of

Epidemiology, 44, 601–607. suicidal behavior. He has a longstanding interest in self-harm in

Skegg, K. (2005). Self-harm. The Lancet, 366, 1471–1483. adolescents.

Skögman, K., & Öjehagen, A. (2003). Motives for suicide at-

This article is intended solely for the personal use of the individual user and is not to be disseminated broadly.

tempts − the views of the patients. Archives of Suicide Re- Siôn Philpott-Morgan received an MSci degree in Mathemati-

This document is copyrighted by the American Psychological Association or one of its allied publishers.

search, 7, 193–206. cal Sciences and Psychology from Durham University, UK, in

Suyemoto, K. L. (1998). The functions of self-mutilation. Clini- 2007. More recently he has worked as a research assistant for

cal Psychology Review, 18, 531–554. Strathclyde University and King’s College London, UK. He is a

Williams, J. M. G. (2014). Cry of pain. London, UK: Little, member of the Royal Statistical Society.

Brown Book Group.

Ystgaard, M., Arensman, E., Hawton, K., Madge, N., van Heerin- Rory O’Connor, Professor of Health Psychology, leads the Sui-

gen, K., Hewitt, A., … Fekete, S. (2009). Deliberate self- cidal Behaviour Research Laboratory at University of Glasgow

harm in adolescents: Comparison between those who receive (http://www.suicideresearch.info), UK. He is President of the

help following self-harm and those who do not. Journal of International Academy of Suicide Research and has a longstand-

Adolescence, 32, 875–891. ing interest in understanding the psychological and psychosocial

factors implicated in the etiology and course of suicide and self-

harm.

Received November 19, 2014

Revision received September 1, 2015

Accepted September 7, 2015 Susan Rasmussen

Published online February 2, 2016

School of Psychological Sciences and Health

University of Strathclyde

Graham Hills Building

40 George Street

Glasgow G1 1QE

UK

Tel. +44 (0)141 548-2575

E-mail s.a.rasmussen@strath.ac.uk

© 2016 Hogrefe Publishing Crisis 2016; Vol. 37(3):176–183

You might also like

- Dazzi Et Al. (2014) Does Asking About Suicide and Related Behaviours Induce Suicidal IdeationDocument3 pagesDazzi Et Al. (2014) Does Asking About Suicide and Related Behaviours Induce Suicidal IdeationSebastián BravoNo ratings yet

- Suicidal Thoughts, Suicidal Behaviours and Self-Harm in Daily Life - A Systematic Review of Ecological Momentary Assessment StudiesDocument38 pagesSuicidal Thoughts, Suicidal Behaviours and Self-Harm in Daily Life - A Systematic Review of Ecological Momentary Assessment Studiesgs67461No ratings yet

- A Qualitative Investigation of Self-Stigma Among Adolescents Taking Psychiatric MedicationDocument7 pagesA Qualitative Investigation of Self-Stigma Among Adolescents Taking Psychiatric MedicationErwinElmaRacasaNo ratings yet

- Epp A000402Document21 pagesEpp A000402Research Articles/Book HubNo ratings yet

- Suicide 2: The Psychology of Suicidal BehaviourDocument13 pagesSuicide 2: The Psychology of Suicidal BehaviourzefmaniaNo ratings yet

- A Survey On Anxiety On The Students of PharmacyDocument4 pagesA Survey On Anxiety On The Students of PharmacyInternational Journal of Innovative Science and Research TechnologyNo ratings yet

- Self-Diagnosis in Psychology Students: The International Journal of Indian Psychology January 2017Document21 pagesSelf-Diagnosis in Psychology Students: The International Journal of Indian Psychology January 2017Ayu ApridaNo ratings yet

- Oconnor Nock Lancet Psychiatry 2014Document14 pagesOconnor Nock Lancet Psychiatry 2014Adonai Jireh Dionne BaliteNo ratings yet

- A Systematic Review of Psychological Suicide PreventionDocument16 pagesA Systematic Review of Psychological Suicide PreventionPiramaxNo ratings yet

- Emanuel 2016Document8 pagesEmanuel 2016MajkaMiaskiewiczNo ratings yet

- NSSI - Dr. Gina LamzonDocument75 pagesNSSI - Dr. Gina LamzonGielynn Dave Bagsican Cloma-KatipunanNo ratings yet

- JuredDocument10 pagesJuredANISA RIFKA RIDHONo ratings yet

- Evaluacion Psicometrica Self StigmaDocument12 pagesEvaluacion Psicometrica Self StigmalorenteangelaNo ratings yet

- Suicide Prevention Strategies Revisited 10-Year SystematicDocument14 pagesSuicide Prevention Strategies Revisited 10-Year Systematicmary morelliNo ratings yet

- Oconnor Nock Lancet Psychiatry 2014Document14 pagesOconnor Nock Lancet Psychiatry 2014Amiya LahiriNo ratings yet

- Fpsyt 09 00079Document14 pagesFpsyt 09 00079Residentes PsiquiatríaNo ratings yet

- Ansiedad en AutismoDocument15 pagesAnsiedad en AutismoalexandraNo ratings yet

- 2015 ExccDocument16 pages2015 ExccD.MNo ratings yet

- The Stigma of Addiction: An Essential GuideFrom EverandThe Stigma of Addiction: An Essential GuideJonathan D. AveryNo ratings yet

- Non-Suicidal Self-Injury v. Attempted SuicideDocument4 pagesNon-Suicidal Self-Injury v. Attempted SuicidealeatoriedadNo ratings yet

- Childhood Trauma:Impact On Personality/Role in Personality DisordersDocument13 pagesChildhood Trauma:Impact On Personality/Role in Personality DisordersNancee Y.No ratings yet

- What Is Autistic BurnoutDocument14 pagesWhat Is Autistic BurnoutPolo RibeiroNo ratings yet

- 4810 12376 1 PB1Document23 pages4810 12376 1 PB1VÂN BÙI THỊ TƯỜNGNo ratings yet

- Risk TakersDocument3 pagesRisk TakerskhaivinhdoNo ratings yet

- Prevention of Suicidal Behavior in Older PeopleDocument14 pagesPrevention of Suicidal Behavior in Older PeopleAndres Felipe Arias OrtizNo ratings yet

- McCarthy CBMH 2020Document14 pagesMcCarthy CBMH 2020ArRa Za (Arra)No ratings yet

- Screening Youth For Suicide Risk in MediDocument6 pagesScreening Youth For Suicide Risk in MediPánico FaunoNo ratings yet

- BJP 2018 27Document8 pagesBJP 2018 27Manon MorenoNo ratings yet

- A Study On Stress Among The Institutionalized Care Takeres of Autistic ChildrenDocument5 pagesA Study On Stress Among The Institutionalized Care Takeres of Autistic ChildrenEditor IJTSRDNo ratings yet

- Psychological Characteristics, Stressful Life Events and Deliberate Self-Harm: Findings From The Child & Adolescent Self-Harm in Europe (CASE) StudyDocument10 pagesPsychological Characteristics, Stressful Life Events and Deliberate Self-Harm: Findings From The Child & Adolescent Self-Harm in Europe (CASE) StudyAuzriella Cherrya Dian VeronicaNo ratings yet

- The Effects of A Reality Therapy Program For The Elderly With Depressive Disorder - Ko.enDocument8 pagesThe Effects of A Reality Therapy Program For The Elderly With Depressive Disorder - Ko.enTroy CabrillasNo ratings yet

- Mackintosh2018 Article TheRelationshipsBetweenSelf-CoDocument11 pagesMackintosh2018 Article TheRelationshipsBetweenSelf-CoMUHAMMAD DANY RAHMANNo ratings yet

- Mental Health & Prevention: Ruth Mcintyre, Patrick Smith, Katharine A. RimesDocument15 pagesMental Health & Prevention: Ruth Mcintyre, Patrick Smith, Katharine A. RimesbooksrgoodNo ratings yet

- The Effect of Transactional Analysis On The Selfesteem of Imprisoned Women A Clinical trialBMC PsychologyDocument7 pagesThe Effect of Transactional Analysis On The Selfesteem of Imprisoned Women A Clinical trialBMC PsychologyHabeeb Uppinangady MBANo ratings yet

- Becker 2007Document6 pagesBecker 2007Stroe EmmaNo ratings yet

- Consequences of Bullying in SchoolsDocument8 pagesConsequences of Bullying in SchoolsThe Three QueensNo ratings yet

- Div Class Title Psychosocial Factors That Distinguish Between Men and Women Who Have Suicidal Thoughts and Attempt Suicide Findings From A National Probability Sample of Adults DivDocument9 pagesDiv Class Title Psychosocial Factors That Distinguish Between Men and Women Who Have Suicidal Thoughts and Attempt Suicide Findings From A National Probability Sample of Adults Divsachinkuk6196No ratings yet

- Clinical Psychology ReviewDocument13 pagesClinical Psychology ReviewRiski NovitaNo ratings yet

- Anxiety Disorders and Suicidal Behaviour: An Update: Jacinta Hawgood and Diego de LeoDocument14 pagesAnxiety Disorders and Suicidal Behaviour: An Update: Jacinta Hawgood and Diego de LeoNeiler OverpowerNo ratings yet

- WijanaDocument15 pagesWijanaĐan TâmNo ratings yet

- 2022 - Autocompasion Modera La Insatisfacción Corporal y La Ideación SuicidaDocument18 pages2022 - Autocompasion Modera La Insatisfacción Corporal y La Ideación SuicidaLuis Vicente Rueda LeónNo ratings yet

- 2018 Article - EJP - Schiep - Kazen - Jaworska - Kuhl - Main-1Document11 pages2018 Article - EJP - Schiep - Kazen - Jaworska - Kuhl - Main-1Mubarak MansoorNo ratings yet

- On The Psychology of The Psychology Subject Pool: An Exploratory Test of The Good Student EffectDocument11 pagesOn The Psychology of The Psychology Subject Pool: An Exploratory Test of The Good Student Effectjungseong parkNo ratings yet

- Research Journal 6Document7 pagesResearch Journal 6aimi zamriNo ratings yet

- Psychological Autopsy Studies of Suicide: A Systematic ReviewDocument12 pagesPsychological Autopsy Studies of Suicide: A Systematic ReviewAna Maryory CASTANO ALVAREZNo ratings yet

- Mag Gen 06 Bouchard 1990 Science Minnesota Twin StudyDocument7 pagesMag Gen 06 Bouchard 1990 Science Minnesota Twin StudyCpeti CzingraberNo ratings yet

- NIH Public Access: Author ManuscriptDocument17 pagesNIH Public Access: Author Manuscriptjindgi23No ratings yet

- Psychotic Symptoms and Population Risk For Suicide Attempt A Prospective Cohort StudyDocument9 pagesPsychotic Symptoms and Population Risk For Suicide Attempt A Prospective Cohort StudyGiselle Andrea Naranjo VillateNo ratings yet

- McCarthy Et Al 2018Document13 pagesMcCarthy Et Al 2018CHARLOTTENo ratings yet

- Pro 31 4 372Document6 pagesPro 31 4 372jamidfNo ratings yet

- Thinking About Suicidal ThinkingDocument4 pagesThinking About Suicidal ThinkingLuísa MartoNo ratings yet

- Silvestri 2018Document22 pagesSilvestri 2018dilla tri audinaNo ratings yet

- Carballo2019 Article PsychosocialRiskFactorsForSuicDocument18 pagesCarballo2019 Article PsychosocialRiskFactorsForSuicAngelina Sosa LoveraNo ratings yet

- Exploring The Risk Factors of Suicide AttemptersDocument25 pagesExploring The Risk Factors of Suicide AttemptersDrkhalidaraufgmail.com RAUFNo ratings yet

- Un Modelo Propuesto Del Desarrollo de Ideas SuicidasDocument10 pagesUn Modelo Propuesto Del Desarrollo de Ideas SuicidasÁngela María Páez BuitragoNo ratings yet

- Autobiographical Memory SpecificityDocument47 pagesAutobiographical Memory SpecificityAnuvinda ManiNo ratings yet

- Effectiveness of Universal Programmes For The Prevention of Suicidal Ideation, Behaviour and Mental Ill Health in Medical StudentsDocument7 pagesEffectiveness of Universal Programmes For The Prevention of Suicidal Ideation, Behaviour and Mental Ill Health in Medical StudentsEsteban MatusNo ratings yet

- 383 12 08 s6 ArticleDocument10 pages383 12 08 s6 ArticleJules IuliaNo ratings yet

- Bradley Et Al 2021 Autistic Adults Experiences of Camouflaging and Its Perceived Impact On Mental HealthDocument10 pagesBradley Et Al 2021 Autistic Adults Experiences of Camouflaging and Its Perceived Impact On Mental HealthLetícia Guedes MouraNo ratings yet

- Relationship Between Inferiority ComplexDocument8 pagesRelationship Between Inferiority ComplexAttiya ZainabNo ratings yet

- Design For Learning Principles Processes and Praxis McDonald and WestDocument435 pagesDesign For Learning Principles Processes and Praxis McDonald and WestCherylNo ratings yet

- (Studies in Feminist Philosophy (Print) ) Cudd, Ann E - Analyzing Oppression-Oxford University Press (2006) PDFDocument293 pages(Studies in Feminist Philosophy (Print) ) Cudd, Ann E - Analyzing Oppression-Oxford University Press (2006) PDFclaubert do valeNo ratings yet

- Chapter 2 DraftDocument20 pagesChapter 2 DraftErica LageraNo ratings yet

- DLL - English 3 - Q1 - W10Document4 pagesDLL - English 3 - Q1 - W10nino nunezNo ratings yet

- Handling Downsizing in The Process Industries - pg11 - 17Document7 pagesHandling Downsizing in The Process Industries - pg11 - 17Soeryanto SlametNo ratings yet

- Volume 3 Issue 2 2023: Newport International Journal of Public Health and Pharmacy (Nijpp)Document11 pagesVolume 3 Issue 2 2023: Newport International Journal of Public Health and Pharmacy (Nijpp)KIU PUBLICATION AND EXTENSIONNo ratings yet

- Teacher Observation Tool Field Study Research ReportDocument33 pagesTeacher Observation Tool Field Study Research ReportAdama DoumbiaNo ratings yet

- The Moderating Effect of Self-Esteem On The Relationship Between Perceived Social Support and Psychological Well-Being Among AdolescentsDocument14 pagesThe Moderating Effect of Self-Esteem On The Relationship Between Perceived Social Support and Psychological Well-Being Among AdolescentsPsychology and Education: A Multidisciplinary JournalNo ratings yet

- Tutor-Marked AssignmentDocument3 pagesTutor-Marked AssignmentZed DyNo ratings yet

- What Is Communication To You?Document18 pagesWhat Is Communication To You?Syeda Farhat QudseeNo ratings yet

- Chap4 PR2 Understanding Data and Ways To Collect DataDocument5 pagesChap4 PR2 Understanding Data and Ways To Collect DataAllyssa RuiNo ratings yet

- Assessment of Learning 1Document5 pagesAssessment of Learning 1Ellaine DuldulaoNo ratings yet

- Ligaya Q. Kasilag Technological Issue ResearchDocument78 pagesLigaya Q. Kasilag Technological Issue ResearchLigaya KasilagNo ratings yet

- Diploma To Degree Engineering Admission 2020-21Document26 pagesDiploma To Degree Engineering Admission 2020-21Prabal KaharNo ratings yet

- Unveiling The Coping Mechanisms of Upcoming Grade 11 Students at Midsayap Dilangalen National High School A Study of Factors and Strategies For Overcoming Challenges in Achieving Grade Requirements.Document8 pagesUnveiling The Coping Mechanisms of Upcoming Grade 11 Students at Midsayap Dilangalen National High School A Study of Factors and Strategies For Overcoming Challenges in Achieving Grade Requirements.CJ CaranzoNo ratings yet

- Team Charter FinalDocument2 pagesTeam Charter Finalapi-641053502No ratings yet

- Control Chart and TypesDocument4 pagesControl Chart and TypesrajaNo ratings yet

- Social Studies SbaDocument14 pagesSocial Studies SbaTedesia AssanahNo ratings yet

- 10 Steps To Writing An Academic ResearchDocument12 pages10 Steps To Writing An Academic Researchabubakar usmanNo ratings yet

- Tos - Ucsp 3rd QRTRDocument1 pageTos - Ucsp 3rd QRTRJessie IsraelNo ratings yet

- Object DetectionDocument7 pagesObject DetectionATISHAY GWARINo ratings yet

- Chavez Ravine Presentation Stealing Home Lesson PlanDocument2 pagesChavez Ravine Presentation Stealing Home Lesson Planapi-501711398No ratings yet

- Paper IiiDocument3 pagesPaper Iiiissa aliNo ratings yet

- Lesson 1-Understanding The Ethical Implications of TechnologyDocument12 pagesLesson 1-Understanding The Ethical Implications of TechnologyVAULTS CHANNELNo ratings yet

- JHS LCP Ap Grade 7 10Document29 pagesJHS LCP Ap Grade 7 10Daryl RiveraNo ratings yet

- International Public Management JournalDocument12 pagesInternational Public Management JournalAmanda PedrosaNo ratings yet

- Lesson PlanDocument6 pagesLesson Plancjeffixcarreon12No ratings yet

- Thess-DLP-COT Q4-Testing HypothesisDocument14 pagesThess-DLP-COT Q4-Testing HypothesisThess ValerosoNo ratings yet

- Brgy. Rizal, Santa Rosa, Nueva Ecija, 3101: Basic Education DepartmentDocument4 pagesBrgy. Rizal, Santa Rosa, Nueva Ecija, 3101: Basic Education DepartmentOfficial Lara Delos SantosNo ratings yet

- Eng8 WLP Q3 Week3Document3 pagesEng8 WLP Q3 Week3ANNABEL PALMARINNo ratings yet