Professional Documents

Culture Documents

J ctv4cbhdf 9

Uploaded by

mauro2021Original Description:

Original Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

J ctv4cbhdf 9

Uploaded by

mauro2021Copyright:

Available Formats

Chapter Title: CONCLUSIONS

Book Title: History of the Opium Problem

Book Subtitle: The Assault on the East, ca. 1600-1950

Book Author(s): Hans Derks

Published by: Brill

Stable URL: http://www.jstor.com/stable/10.1163/j.ctv4cbhdf.9

JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide

range of content in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and

facilitate new forms of scholarship. For more information about JSTOR, please contact support@jstor.org.

Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of the Terms & Conditions of Use, available at

https://about.jstor.org/terms

This content is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0

International License (CC BY-NC 4.0). To view a copy of this license, visit

https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/.

Brill is collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve and extend access to History of the

Opium Problem

This content downloaded from

190.101.140.103 on Mon, 01 Jun 2020 02:04:17 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

conclusions 31

chapter four

CONCLUSIONs

The search for the original sin brings us, indeed, in or near the Garden of

Eden, the Middle East. More importantly, we are confronted with many

connotations surrounding the use of Papaver species, including the opi-

um poppy, Papaver somniferum. So, up to the beginning of the 16th-cen-

tury small quantities of Papavers are used among many herbs for personal

food and energy (oil of the seeds) and for economic, medical and luxury

or recreational reasons. The last two applications in particular could be

directly connected to death and poison, to impotence as well as to a sex-

ual palliative or temporary stronger sex activity, to a restricted use among

the elite (warriors, etc.). Indeed, in the Middle Eastern medical and court

life of the Ottoman empire, many of these elements of Papavers were

known. It was surrounded with legends and more or less embedded in an

elite culture.

Arab and Muslim traders spread hallucinogenic products, knowledge

and customs from the Middle East into the North Indian societies via

Hormuz, Surat and similar merchant cities from—say—the 14th-century

onwards. At that time it was just a very small item in an extensive trade

assortment of these caravan and maritime merchants.

In other words, China has nothing to do with this “original sin”. It is

also ridiculous to refer to Neolithic circumstances to explain the use of

opium as an aphrodisiac; its history can only start where all relevant ele-

ments are available concerning ecological, economic, social and cultural

preconditions. The most important aspect for our study is: there was no

opium problem nor an “Opium Question” as a mass phenomenon!

But why then referring to some “original sin”? The answer can be found

at the provisional end of our history. A modern highly ambiguous British

writer on The Paradise also came across Muslim opium producers and

traders in Afghanistan. To introduce the second part of his historical anal-

ysis, covering the years 1000-1500 (ACE), he talks about such a meeting

with an Afghan opium farmer and ‘his dangerous but very pretty crops’ (!):

The opium, the farmer said, was not as healthy as it looked … Did he smoke

it? No. People said Iranians liked it, but he personally had never tried the

This content downloaded from

190.101.140.103 on Mon, 01 Jun 2020 02:04:17 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

32 chapter four

stuff. How did it make them feel? He shrugged. Like they were in al-jenna,

the Garden of Paradise. No, he couldn’t sell me a few kilos ...1

This British dealer in Paradise reacts like one of the British soldiers in

Helmland, who are accused of only guarding the poppy fields and playing

arch-angel at the gate of Paradise in stead of fighting the Taliban, who

‘also got rid of hashish and opium.’2

The earliest Western intruders in the Middle Eastern world, those of

the 16th and 17th centuries, started to create these “Afghanistan interest(s)”

and committed the original sin. They pointed to bewildering aspects of

the opium use in a contradictory way as well, because they were confront-

ed for the first time with a regular use of new kinds of herbs and plants in

medicine, the kitchen, religion or elsewhere in the Levant, Middle East or

India. Their curiosity about what could be useful for themselves or in the

militant exchange they organized with these new worlds, also changed in

these centuries in a rather drastic way in the wake of an intensification of

Western imperialism and colonialism: opium became, first and foremost,

an isolated “Asian product” unconnected to any original social, ecological

and economic context. This isolation was executed under the most barba-

rous circumstances: the original sin.

Did an Opium Question originate in the 17th, develop in the 18th-cen-

tury and explode in the 19th-century? Indeed, how this happened and

what are the consequences still felt today form the subject of the follow-

ing historical analysis, which does not aim at legitimizing any behavior.

Because the English were by far the most exuberant profiteers of the

Opium Problem, their performance will be discussed first. It gives us the

opportunity to sketch the general case, whereupon the analysis of the

Dutch, French or Chinese performances can provide us with the neces-

sary details, definitions of an Opium Question and comparisons. In par-

ticular the Dutch assault of the East is interesting not so much due to Jan

Huygen van Linschoten’s text as to their “first commitment of the original

sin”, the example which was followed by all other Western opium inter-

ests.

1 K. Rushby, p. 39.

2 Idem, p. 43.

This content downloaded from

190.101.140.103 on Mon, 01 Jun 2020 02:04:17 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

You might also like

- MYRES Anthropology and Political ScienceDocument98 pagesMYRES Anthropology and Political Sciencefortunesold00No ratings yet

- The Myers-Briggs, Enneagram, and SpiritualityDocument11 pagesThe Myers-Briggs, Enneagram, and SpiritualityMehmet EkinNo ratings yet

- TinyRituals-Healing Crystals GuideDocument46 pagesTinyRituals-Healing Crystals GuideJetaun Banks100% (1)

- Reflection Paper On D. Bonhoeffer's: "Life Together"-By Maria Grace, Ph.D.Document10 pagesReflection Paper On D. Bonhoeffer's: "Life Together"-By Maria Grace, Ph.D.Monika-Maria Grace100% (1)

- HistoryOfZoroastrianism 1Document375 pagesHistoryOfZoroastrianism 1Icaro MoreiraNo ratings yet

- Alchemy in Popular Culture - William EamonDocument19 pagesAlchemy in Popular Culture - William EamonPaulo BentoNo ratings yet

- RICE, Timothy. Ethnomusicology in Times of TroubleDocument20 pagesRICE, Timothy. Ethnomusicology in Times of TroublePaula BessaNo ratings yet

- Foreign AffairsDocument268 pagesForeign AffairsRashid AliNo ratings yet

- The Good Book - A Humanist BibleDocument11 pagesThe Good Book - A Humanist Biblehnif2009No ratings yet

- Orthodox Psychotherapy: D.A. AvdeevDocument47 pagesOrthodox Psychotherapy: D.A. AvdeevLGNo ratings yet

- The Ostrich FactorDocument177 pagesThe Ostrich Factorjov25100% (1)

- The Physiology of Taste; Or, Transcendental GastronomyFrom EverandThe Physiology of Taste; Or, Transcendental GastronomyRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (2)

- Opium Culture: The Art and Ritual of the Chinese TraditionFrom EverandOpium Culture: The Art and Ritual of the Chinese TraditionRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (3)

- Crime and Custom in Savage Society: An Anthropological Study of SavageryFrom EverandCrime and Custom in Savage Society: An Anthropological Study of SavageryNo ratings yet

- HistoricalRoots of EcologicalCrisisDocument6 pagesHistoricalRoots of EcologicalCrisisJabłkowyBałwanek100% (1)

- Chimpanzee Culture Wars: Rethinking Human Nature alongside Japanese, European, and American Cultural PrimatologistsFrom EverandChimpanzee Culture Wars: Rethinking Human Nature alongside Japanese, European, and American Cultural PrimatologistsNo ratings yet

- J ctv4cbhdf 8Document13 pagesJ ctv4cbhdf 8mauro2021No ratings yet

- This Content Downloaded From 190.101.140.103 On Mon, 01 Jun 2020 02:04:48 UTCDocument17 pagesThis Content Downloaded From 190.101.140.103 On Mon, 01 Jun 2020 02:04:48 UTCmauro2021No ratings yet

- J ctv4cbhdf 15Document31 pagesJ ctv4cbhdf 15mauro2021No ratings yet

- J ctv4cbhdf 10Document17 pagesJ ctv4cbhdf 10mauro2021No ratings yet

- J ctv4cbhdf 6Document11 pagesJ ctv4cbhdf 6mauro2021No ratings yet

- This Content Downloaded From 190.101.140.103 On Mon, 01 Jun 2020 02:05:29 UTCDocument51 pagesThis Content Downloaded From 190.101.140.103 On Mon, 01 Jun 2020 02:05:29 UTCmauro2021No ratings yet

- J ctv4cbhdf 26Document9 pagesJ ctv4cbhdf 26mauro2021No ratings yet

- Essay EmpiresDocument12 pagesEssay Empires8yyqmxb2zjNo ratings yet

- Pierre Poivre and the Networking Naturalists: Pioneering Environmentalists of the Eighteenth CenturyFrom EverandPierre Poivre and the Networking Naturalists: Pioneering Environmentalists of the Eighteenth CenturyNo ratings yet

- Demystifying A Change in Taste Spices, Space, and Social Hierarchy in Europe, 1380-1750 Author(s) Stefan Halikowski SmithDocument22 pagesDemystifying A Change in Taste Spices, Space, and Social Hierarchy in Europe, 1380-1750 Author(s) Stefan Halikowski SmithAlexandra Roldán TobónNo ratings yet

- Malcolm X Essay TopicsDocument5 pagesMalcolm X Essay Topicslpuaduwhd100% (2)

- Save The World EssayDocument5 pagesSave The World Essayafabkkkrb100% (2)

- Preuss ObituaryDocument3 pagesPreuss ObituaryHéctor MedinaNo ratings yet

- 11 - Chapter 2Document64 pages11 - Chapter 2Vinay Kumar KumarNo ratings yet

- French Anthropology in 1800Document18 pagesFrench Anthropology in 1800Marcio GoldmanNo ratings yet

- Great Depression EssaysDocument5 pagesGreat Depression Essaysflrzcpaeg100% (2)

- Happiness, Final 10 SubtitledDocument25 pagesHappiness, Final 10 SubtitlednegritomonitaNo ratings yet

- J ctv4cbhdf 17Document19 pagesJ ctv4cbhdf 17mauro2021No ratings yet

- An Introduction To Social Anthropology - Mair, Lucy Philip, 1901 - 1972 - Oxford Clarendon Press - 9780198740100 - Anna's ArchiveDocument332 pagesAn Introduction To Social Anthropology - Mair, Lucy Philip, 1901 - 1972 - Oxford Clarendon Press - 9780198740100 - Anna's Archivec130makNo ratings yet

- A Brief Introduction To The HistoryDocument13 pagesA Brief Introduction To The Historybasco costasNo ratings yet

- Strong Drink and Tobacco Smoke - The Structure, Growth, and Uses of Malt, Hops, Yeast, and TobaccoFrom EverandStrong Drink and Tobacco Smoke - The Structure, Growth, and Uses of Malt, Hops, Yeast, and TobaccoNo ratings yet

- Futures Volume 4 Issue 2 1972 (Doi 10.1016/0016-3287 (72) 90041-9) I.F. Clarke - 3. More's Utopia - The Myth and The Method PDFDocument6 pagesFutures Volume 4 Issue 2 1972 (Doi 10.1016/0016-3287 (72) 90041-9) I.F. Clarke - 3. More's Utopia - The Myth and The Method PDFManticora VenerabilisNo ratings yet

- The Battle For International Law South North Perspectives On The Decolonization Era Jochen Von Bernstorff and Philipp Dann Full ChapterDocument68 pagesThe Battle For International Law South North Perspectives On The Decolonization Era Jochen Von Bernstorff and Philipp Dann Full Chaptertodd.hogan318100% (5)

- Spectres of Fascism: Historical, Theoretical, and International PerspectivesFrom EverandSpectres of Fascism: Historical, Theoretical, and International PerspectivesNo ratings yet

- TRANSLATION SENTENCES - QuestionsDocument5 pagesTRANSLATION SENTENCES - QuestionsYekta CengizNo ratings yet

- Essay Topics For Oedipus RexDocument9 pagesEssay Topics For Oedipus Rexb7263nq2100% (2)

- 4Document18 pages4RossanZapantaNo ratings yet

- AULA 18. THE Opium ProblemDocument17 pagesAULA 18. THE Opium ProblemMaria Leticia de Alencar MachadoNo ratings yet

- A Vindication of England's Policy with Regard to the Opium TradeFrom EverandA Vindication of England's Policy with Regard to the Opium TradeNo ratings yet

- Planning for the Planet: Environmental Expertise and the International Union for Conservation of Nature and Natural Resources, 1960–1980From EverandPlanning for the Planet: Environmental Expertise and the International Union for Conservation of Nature and Natural Resources, 1960–1980No ratings yet

- Benedict PROPAGANDAPRINTPERSUASION 2007Document27 pagesBenedict PROPAGANDAPRINTPERSUASION 2007Αγορίτσα Τσέλιγκα ΑντουράκηNo ratings yet

- Tropical BryologyDocument200 pagesTropical BryologyErica De GuzmanNo ratings yet

- Thompson AnthropologyScience 1907Document9 pagesThompson AnthropologyScience 1907danielNo ratings yet

- The Nature of Agriculture (I) : Joseph B. McdonaldDocument28 pagesThe Nature of Agriculture (I) : Joseph B. Mcdonaldhimanshu singhNo ratings yet

- This Content Downloaded From 197.156.73.170 On Sun, 20 Mar 2022 15:12:18 UTCDocument25 pagesThis Content Downloaded From 197.156.73.170 On Sun, 20 Mar 2022 15:12:18 UTCNatnael TafesseNo ratings yet

- Tobacco and KretekDocument22 pagesTobacco and KretekMarfu'ah Mar'ahNo ratings yet

- Unesco - The Race Concept (1952)Document107 pagesUnesco - The Race Concept (1952)satov999100% (1)

- Especias y Medievo TardíoDocument20 pagesEspecias y Medievo TardíoAntonioGallegoLiébana100% (1)

- J ctv4cbhdf 25Document17 pagesJ ctv4cbhdf 25mauro2021No ratings yet

- J ctv4cbhdf 23Document13 pagesJ ctv4cbhdf 23mauro2021No ratings yet

- J ctv4cbhdf 22Document13 pagesJ ctv4cbhdf 22mauro2021No ratings yet

- J ctv4cbhdf 24Document39 pagesJ ctv4cbhdf 24mauro2021No ratings yet

- J ctv4cbhdf 26Document9 pagesJ ctv4cbhdf 26mauro2021No ratings yet

- This Content Downloaded From 190.101.140.103 On Mon, 01 Jun 2020 02:05:54 UTCDocument19 pagesThis Content Downloaded From 190.101.140.103 On Mon, 01 Jun 2020 02:05:54 UTCmauro2021No ratings yet

- This Content Downloaded From 190.101.140.103 On Mon, 01 Jun 2020 02:05:38 UTCDocument17 pagesThis Content Downloaded From 190.101.140.103 On Mon, 01 Jun 2020 02:05:38 UTCmauro2021No ratings yet

- J ctv4cbhdf 16Document9 pagesJ ctv4cbhdf 16mauro2021No ratings yet

- This Content Downloaded From 190.101.140.103 On Mon, 01 Jun 2020 02:05:29 UTCDocument51 pagesThis Content Downloaded From 190.101.140.103 On Mon, 01 Jun 2020 02:05:29 UTCmauro2021No ratings yet

- J ctv550c6p 4Document5 pagesJ ctv550c6p 4mauro2021No ratings yet

- This Content Downloaded From 190.101.140.103 On Mon, 01 Jun 2020 02:05:44 UTCDocument23 pagesThis Content Downloaded From 190.101.140.103 On Mon, 01 Jun 2020 02:05:44 UTCmauro2021No ratings yet

- J ctv4cbhdf 17Document19 pagesJ ctv4cbhdf 17mauro2021No ratings yet

- J ctv4cbhdf 12Document19 pagesJ ctv4cbhdf 12mauro2021No ratings yet

- J ctv4cbhdf 14Document13 pagesJ ctv4cbhdf 14mauro2021No ratings yet

- J ctv4cbhdf 7Document9 pagesJ ctv4cbhdf 7mauro2021No ratings yet

- CosasDocument5 pagesCosasmauro2021No ratings yet

- CasasDocument3 pagesCasasmauro2021No ratings yet

- Reference Letter Guide2Document2 pagesReference Letter Guide2mauro2021No ratings yet

- J ctv550c6p 2Document5 pagesJ ctv550c6p 2mauro2021No ratings yet

- J ctv550c6p 3Document3 pagesJ ctv550c6p 3mauro2021No ratings yet

- CosasDocument6 pagesCosasmauro2021No ratings yet

- PomoDocument7 pagesPomomauro2021No ratings yet

- 00155Document1 page00155mauro2021No ratings yet

- Joyful Mysteries: The Mysteries of The RosaryDocument4 pagesJoyful Mysteries: The Mysteries of The RosaryMarius SumiraNo ratings yet

- Jacobean DramaDocument3 pagesJacobean DramaPandiya RajanNo ratings yet

- Comprehensive DuaDocument2 pagesComprehensive DuaMohamed S HusainNo ratings yet

- Literature Eassy 2.0Document6 pagesLiterature Eassy 2.0Vincent LavadorNo ratings yet

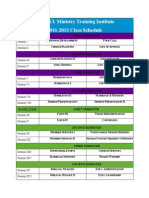

- AZUSA MTI Class Schedule For Blocks 3&4Document1 pageAZUSA MTI Class Schedule For Blocks 3&4AZUSA World Ministries Ministry Training InstituteNo ratings yet

- Book Sample: Chapter EightDocument3 pagesBook Sample: Chapter EightHelio LaureanoNo ratings yet

- B.A.LL. B (Integrated Law Degree Course) Muslim LawDocument9 pagesB.A.LL. B (Integrated Law Degree Course) Muslim LawGaurav GehlotNo ratings yet

- Civic Bab 1Document5 pagesCivic Bab 1Alief Amalia ArdiningsihNo ratings yet

- Some Shubuhat Doubts in Connection With Judging Upon The ApparentDocument25 pagesSome Shubuhat Doubts in Connection With Judging Upon The ApparentHAFEES AMNo ratings yet

- Chapter 15pmdDocument26 pagesChapter 15pmdAbdulmojeed AdisaNo ratings yet

- Form Sinersi Online-1Document10 pagesForm Sinersi Online-1Arim ff8No ratings yet

- Kalam JamaieDocument5 pagesKalam JamaieSharifah NorazlinaNo ratings yet

- Ia List of Delegates PMDocument33 pagesIa List of Delegates PMSTEVE JHONSON LepasanaNo ratings yet

- 15-16 Church Year Calendar - Series CDocument2 pages15-16 Church Year Calendar - Series Capi-223646140No ratings yet

- Jurnal Tugas Uas Isu Isu PendidikanDocument13 pagesJurnal Tugas Uas Isu Isu Pendidikananugrah putraNo ratings yet

- Cure of Ars - Catechism On The PriesthoodDocument2 pagesCure of Ars - Catechism On The PriesthoodJavier lopezNo ratings yet

- Capital of The WorldDocument11 pagesCapital of The WorldAsifNo ratings yet

- 2012-04 - April 2012 2010 Version 4Document4 pages2012-04 - April 2012 2010 Version 4api-525213434No ratings yet

- A Treatise On Revelation 13 18Document9 pagesA Treatise On Revelation 13 18Nicholas LagosNo ratings yet

- Sermon: One ThingDocument1 pageSermon: One ThingRichard MelvilleNo ratings yet

- 0kramer - Sumerian Cosmology - PartialDocument4 pages0kramer - Sumerian Cosmology - Partialapi-493307654No ratings yet

- Presentation (EI)Document11 pagesPresentation (EI)kittissloNo ratings yet

- Structural-Functionalist PerspectiveDocument4 pagesStructural-Functionalist PerspectiveAnirbaan AntareepNo ratings yet

- Hafizabad 8th Class Result 2012Document101 pagesHafizabad 8th Class Result 2012Studentstudy SolNo ratings yet

- Light Novel - Manga ListDocument185 pagesLight Novel - Manga ListariareinaldNo ratings yet