Professional Documents

Culture Documents

The Catalogus Baronum

Uploaded by

Patrick JenkinsCopyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

The Catalogus Baronum

Uploaded by

Patrick JenkinsCopyright:

Available Formats

bs_bs_banner

The Catalogus Baronum and the recruitment and

administration of the armies of the Norman kingdom

of Sicily: a re-examination*

James Hill

University of Leeds

Abstract

The Catalogus Baronum has long been overlooked in the corpus of texts relating to the Norman

period of south Italy due to its chaotic nature and the difficulties of obtaining information

from it. Seeking to rectify this situation, this article re-evaluates the current conclusions drawn

from the Catalogus by academics such as Jamison using data derived from a statistical analysis of

the document. By abandoning a rigidly ‘feudal’ interpretation of the document new areas of

research are opened up. Additionally, it offers new theories on the use and nature of the

Catalogus, informed by this research and approach.

The main source of information concerning the theoretical provision of troops for

military service in the kingdom of Sicily during the so-called Norman period in the

twelfth century is the Catalogus Baronum.1 This was a register of military obligations in

the duchy of Apulia, the principality of Capua and the Abruzzi region which had

recently been conquered by King Roger, based on fiefs held from the crown. It was

first compiled c.1150, potentially in response to the threat of invasion by both Manuel

Komnenus and Conrad III. The only known manuscript was destroyed in the Second

World War, but has been preserved through photographs, from which the modern

edition was compiled in 1972.

This article seeks to explore the importance of the Catalogus for the military

organization of the mainland regions of Apulia and Calabria in the twelfth century,

which are detailed in the section of the document titled the Quaternus Magne

Expeditionis. It will also seek to reconcile the textual problems of the Catalogus with the

historiography surrounding it, and attempt to establish what the purpose of the

document actually was.

In order to understand the Catalogus, it must be placed in context. Thus, what

understanding there is of the military administration in the Norman period before the

establishment of the kingdom must be considered first. This period extends from

the beginning of Norman infiltration of the region in roughly the ten-twenties to the

foundation of the kingdom in 1130. What military recruitment systems existed before

the mid twelfth century, and the extent to which they differ from the system described

in the Catalogus, needs to be addressed. Military obligation and service in Normandy,

* This article was first given as a paper at the International Medieval Congress at Leeds in July 2011. The

author would like to thank Prof. G. A. Loud for his assistance.

1

The edition used in this project is Jamison’s (Catalogus Baronum, ed. E. M. Jamison (Rome, 1972) (hereafter

Catalogus)). The manuscript itself was destroyed in Sept. 1943 when German troops burned the contents of the

Naples State Archive. This edition, edited from photocopies and previous transcripts, is the most complete.

Copyright © 2012 Institute of Historical Research DOI: 10.1111/j.1468-2281.2012.00605.x

Published by Blackwell Publishing Ltd., 9600 Garsington Road, Oxford, OX4 2DQ, UK and 350 Main Street, Malden, MA 02148, USA.

2 The Catalogus Baronum: a re-examination

at the time when the Normans first came to southern Italy, has been well discussed by

Chibnall,2 and this article will see how this model can fit with the south Italian

experience. However, it is not the intention to re-work Reynolds’s authoritative

research on fiefs,3 and this section will only consider the development of the south

Italian feudum in so much as it pertains to vassalage and the Catalogus.

With its context established, the content of the Catalogus and how this has been

treated can be considered.This will be done by looking at the superficial data that can

be gathered from the Catalogus and the extent to which these overall totals and patterns

support the existing scholarship on the document. Additionally, the nature of the

document and its intended purpose must be examined; where the evidence conflicts

with the conclusions of modern scholarship, alternatives which are supported by the

evidence will be suggested.

Finally, the problems contained within the Catalogus must be investigated, as well as

how these can be dealt with.Verification of the data contained within the document

can be done partially by comparison with narrative sources, and partially through

studying the internal consistency of the document. The article will also examine how

the document can be used to establish patterns in types of landholding, and will

compare this to other such patterns in similar kingdoms.

Rather than being a single item, the manuscript, which was copied in the mid

thirteenth century, was in fact a compendium of three different documents. The

earliest and largest, the Quaternus Magne Expeditionis, was compiled c.1150 and revised

around 1168. The second document, which lists the milites of Arce, Sora and Aquino,

three settlements on the northern border of the kingdom, was drawn up soon

afterwards in 1175.4 The final document, entitled Pheudatarii Justitiariatus Capitanante

(‘the feudatories of the justiciarship of the Capitanata’), was drawn up c.1240.5

However, these two final documents are very short, and in the latter case did not even

pertain to the Norman period of the kingdom; the Quaternus makes up the vast bulk

of the overall manuscript. This collection of documents, generally referred to as the

Catalogus Baronum, was only copied a century after the original composition of the

Quaternus, and while all three documents relate to fief-holding and military service,

they would not necessarily have been associated with each other when they were in

use. It is unclear if the names of the individual documents were originally used, or if

they were later interpolations when the documents were brought together.

The manuscript of the Quaternus itself was copied several times before it reached

the last surviving copy. In addition to this, it was heavily modified in the period

between 1150 and 1168, when the register was updated as it was needed.This extensive

removal from the original has left its mark on the text, with one substantial section

copied twice, and a myriad of other scribal errors also present in the manuscript.6

Nevertheless, it remains the only register of military obligation contemporary with the

period from this area.

In order to address the nature of the Catalogus, it must first be placed into context.The

period before the foundation of the kingdom in 1130 was one of division and dispute.

M. Chibnall, ‘Military service in Normandy before 1066’, Anglo-Norman Stud., v (1982), 65–77.

2

S. Reynolds, Fiefs and Vassals: the Medieval Evidence Reinterpreted (Oxford, 1994).

3

Catalogus, entries 1263–372.

4

5

Catalogus, entries 1373–442; and foreword, p. xv.

6

Catalogus, entries 1230–62 duplicate entries 1053–84, while entries 65, 199–209, 268, 392, 446, 586 are all

examples of scribal errors, but this is by no means a comprehensive list.

Copyright © 2012 Institute of Historical Research

The Catalogus Baronum: a re-examination 3

Thus, identifying an overall trend in the patterns of military service during these

years is problematic, although once political unity was established a more unified

military structure began to emerge. The mainland of south Italy was divided before

the Norman takeover between a predominantly Lombard set of city states in the

north-west and west, while the eastern and southern parts were directly ruled as part

of the Byzantine empire. These regions were separated ethnically, politically and

religiously, but not along the same boundaries: the north of Apulia was predominantly

Lombard, while Latin and Greek rites occurred with little regard to political borders.

The fractured nature of the conflicts before 1130 also presents a problem: at no point

before the acceptance of Roger II’s authority was there any sort of unified army, so

any military figures that do exist represent a myriad of groups that were rarely the

same in each conflict.

The Lombard states had a system of military service similar to that of the Normans

before their arrival, which is to say, personal and direct rather than institutionalized.7

However, the pre-kingdom period had no real idea of ‘feudal’ relationships in the

institutional sense. Land was recorded as being given as a gift for loyal and effective

service, rather than as a condition for continued duty.8 Before the Normans, the coastal

cities of Gaeta and Naples had land set aside which appears to have been designated

exclusively as a reward for service to the city, but it was not granted in an institutional

fashion. Where a reason for a land grant is given, it is always as a reward for a single

action, rather than for a defined term of service.9 In this way, the grant of Aversa to

Count Rainulf by Sergius, duke of Naples can be seen as normal for the time, as this

model predated the Norman takeover as well as being the usual practice in Norman

south Italy before the creation of the unified kingdom.10 Hence a grant by Robert

Guiscard to his master of the wardrobe in 1079 suggests that Robert was conferring

the land and other property therein as a reward for loyal service, rather than as a

contractual obligation to continue providing support.11 This is not to suggest that

continued loyalty was not the desired result of the gift; merely that the gift did not

come with any contractual requirements for service attached to the land.

However, on a lower level such dependent tenure did occur, as in the case of a

charter issued by Bishop Rainulf of Chieti (in office from 1087 to 1101), which

describes in detail a ‘feudal’ practice: a certain Geoffrey of Vulturara owed forty days’

service a year in exchange for land from the church.12 Nevertheless, the term feudum

(or any term which might denote an entity such as a ‘fief ’) does not appear at any

point in this charter, nor does the phrasing or language of the later documents. It is

also an isolated case – the document is the only one we have for the entire Norman

period that stipulates a term of service. Indeed, the problem is considerably more

7

C. Cahen, Le régime féodal de l’Italie Normande (Paris, 1940), pp. 29–30; P. Skinner, ‘When was southern Italy

“feudal”?’, Settimane di studio del centro italiano di studi sull’alto medioevo, xlvii (2000), 309–45, at p. 320.

8

J.-M. Martin, ‘Les structures féodales normanno-souabes et la Terre Sainte’, in Il mezzogiorno normanno-svevo

e le crociate (Atti delle quattordicesime giornate normanno-sveve, Bari 17–20 ottobre 2000), ed. G. Musca (Bari, 2002),

pp. 225–50, at p. 229.

9

Skinner, p. 322.

10

Skinner, pp. 323–4. Amatus of Montecassino, The History of the Normans, trans. P. N. Dunbar, rev. G. A. Loud

(Woodbridge, 2004) (hereafter Amatus), bk. I, ch. 42, p. 60.

11

Recueil des actes des ducs normands d’Italie (1046–1127), i: les premiers ducs (1046–87), ed. L.-R. Ménager (Bari,

1980), pp. 97–8, no. 28. This is not strictly a land charter, but rather the grant of a house and some land in

Salerno. However, given the uncertainty about the use of the term feudum when it does appear in the 12th

century, this grant remains relevant to the discussion.

12

F. Ughelli, Italia sacra: sive de episcopis Italiæ (10 vols., Venice, 1717–22), vi. 700.

Copyright © 2012 Institute of Historical Research

4 The Catalogus Baronum: a re-examination

general: the term feudum does not appear until well after the first decade of the twelfth

century, and phidon only appears in Greek in 1120.13 This makes it difficult to think of

the term as a Norman import, and although it was in use in Normandy and England

far earlier than it was in south Italy,14 this was still well after the majority of

immigration from Normandy had ceased and the uses of the term in both regions are

not easy to reconcile. Furthermore, some of the best evidence for dependent tenure

and military service in the early twelfth century actually derives from the Abruzzi

region, which was only partly penetrated by the Normans, and was certainly not

confined to those of Norman descent.15 This suggests, therefore, that these ‘feudal

practices’ were widely diffused and were not necessarily a purely Norman import.

A term that may have been introduced by the Normans, however, was beneficium,

which appears in two early charters from Aversa.16 These, however, are inconclusive –

they appear to offer knight service, but in no defined way at all, and certainly do not

qualify as evidence for the elaborate ‘feudal’ structures posited by scholars such as Cahen

and Cuozzo. It is interesting that the term beneficium seems only to have appeared in

Aversa, a town founded and largely inhabited by Normans, and seems to have fallen out

of use as time goes on. So while the formalized structures described in the mid twelfth

century cannot be seen during the pre-kingdom period, the Lombard states were clearly

the closest to them of the political groups that the Normans came to dominate.

The Byzantine territories were significantly different from the Lombard states.

Rather than consisting of small independent states, all of Apulia and Calabria were part

of the empire and thus were organized within the administrative structures that it

possessed. The towns of these areas were expected to levy their own militia while

any major military campaigns were the responsibility of the military command in

Constantinople.17 However, in practice, south Italy ranked low on the list of Byzantine

problems in comparison with the empire’s woes in Asia Minor and the Balkans. The

ultimately unsuccessful 1038 campaign to reclaim Sicily was the last serious expedition

sent by Constantinople until the establishment of the Norman kingdom (with the

exception of a few small relief forces sent over during the conquest of Apulia, which

were entirely unsuccessful, it was the only major expedition sent in the eleventh

century). So the Greek settlements on the mainland were largely left to fend for

themselves without the aid of the professional Byzantine army: service was presumably

performed by the citizens of a town, as was required. Furthermore, while the nature

and size of the aristocracy in Byzantine Apulia is disputed, it is clear that the social

elites of the region were not dominated by a warrior class.18

Following the conquest, the greatest changes appear to have been outside the

towns, where lordships were given to Normans and occupied by them, forming the

basis for a Lombard/Norman style of military service.19 The practice in Apulia can

13

Cahen, p. 48.

14

Chibnall, p. 74.

15

E.g., Il cartulario della chiesa Teramana, ed. F. Savini (Rome, 1910), pp. 68–9, no. 35 (1114), in which an

aristocrat agrees to hold his land from the bishop of Aprutium, and provide military service to him (cf. pp. 70–2,

no. 38 (1116)). It should be noted that in neither of these two charters is the word feudum actually employed.

16

Codice diplomatico normanno di Aversa, ed. A. Gallo (Naples, 1926), pp. 386–7, no. 43 (1068); pp. 399–401,

no. 53 (1073).

17

G. A. Loud, The Age of Robert Guiscard: Southern Italy and the Norman Conquest (Harlow, 2000), p. 77.

18

Skinner, p. 331.

19

V. von Falkenhausen, ‘Il popolamento: etniè, fedi, insediamenti’, in Terra e uomini nel mezzogiorno

normanno-svevo (Atti delle settime giornate normanno-sveve, Bari, 15–17 ottobre 1985), ed. G. Musca (Bari, 1987),

pp. 68–9.

Copyright © 2012 Institute of Historical Research

The Catalogus Baronum: a re-examination 5

be seen to begin with the division of the region among the Norman lords at Melfi,

separating it into twelve counties, including land they had not yet conquered.20

However, as with the Lombard states, the terminology of a ‘feudal’ system was

missing: lands were granted to loyal knights, but without constitutional requirement

for service to the duke of Apulia. Ties of service were personal and based on loyalty

(or coercion, as will be seen) rather than on legal bonds. However, the process of

settlement and adjustment from local custom to a centralized ‘Norman’ system must

be seen as a gradual one, instituted much later than the point at which the land was

notionally divided among the Normans. Additionally, the large towns in Apulia

appear to have been almost unaffected by this gradual shift. In Bari, where a wealth

of documentation exists, there is little evidence of interference from its Norman

overlords. Aside from a nominal lord appointed by the duke after its conquest in

1071, virtually no attempts to enforce ducal power or draw forces from Bari were

made until the reforms of the mid twelfth century. Furthermore, after the reduction

in ducal authority during the rule of Roger Borsa, cities like Bari appear to have

claimed virtual autonomy, forcing the duke to deal with rather than command

them.21

Thus, these varied geographical areas, encompassing different religious and ethnic

groups under Norman influence, appear eventually to have adopted a new, relatively

universal ‘Norman’ system by the mid twelfth century. However, it is difficult to

establish the course of these events. While the creation of dependent tenures can be

seen right from Count Rainulf’s operations in Aversa to the division of land between

the Norman lords in 1042 at Melfi, the ‘feudal’ language of the later twelfth century

is simply absent. Notably, the land charter issued by Bishop Rainulf of Chieti does

describe a traditional vassal relationship in exchange for land, but without the

ideological and legal terminology of French ‘feudal’ relationships. Thus, it appears that

the great shift in the attitude of nobles and administrators between the pre- and

post-kingdom period was not one of dependent tenure, which seemed to exist in

both, but to whom the land ultimately belonged. This change in attitudes to ducal

and eventually royal authority can be traced through the pattern of rebellions against

the expanding authority of the Hauteville lords and kings. This helps to provide a

rough guide to the expansion of central authority and the institutionalization of

military service. While early revolts during Guiscard’s rule were generally incited

by his dispossessed cousins attempting to regain their power, the 1082 rebellion

following the invasion of Byzantium in 1081 was a much more universal action.22

The invasion was deeply unpopular, as William of Apulia states: ‘it seemed to many

that this expedition was an unfair and burdensome matter, and in particular those

who had wives and much-loved children at home were reluctant to fight such a war.

But the duke reinforced his gentle persuasions with threats, and forced many to

go’.23

Robert’s difficulty in coercing his vassals into sending troops, the extent of the

rebellion and the length of time it took him to subdue it suggests that this was a

20

Amatus, bk. II, ch. 31, p. 77; Loud, Age of Robert Guiscard, p. 95.

21

P. Oldfield, City and Community in Norman Italy (Cambridge, 2009), p. 34.

22

While the rebellion was once again led by Guiscard’s dispossessed nephew, Abelard, this one appears to have

included a significantly larger portion of the higher nobility (Loud, Age of Robert Guiscard, pp. 217–19).

23

Guillaume de Pouille, La Geste de Robert Guiscard, ed. M. Mathieu (Palermo, 1961), bk. IV, ll. 128–32, p. 210

(English trans. by G. A. Loud).

Copyright © 2012 Institute of Historical Research

6 The Catalogus Baronum: a re-examination

serious challenge to his authority to draw the required number of troops.24 A similar

pattern can be seen after the death of Robert Guiscard, when his centralized rule,

based on his own personal connections, collapsed, as his sons and other nobles

quarrelled among themselves.25 From this period to Roger II’s creation of the

kingdom, the conflicts that occurred were between the various barons and counts on

the mainland. Roger Borsa’s status as duke of Apulia had minimal impact and he was

effectively reduced to little more than a territorial count in terms of his authority; he

was also forced to concede land to secure the assistance of his uncle Count Roger

against rebellious counts, rather than simply commanding his obedience.26 However,

after Roger II attempted to install his own authority over all of mainland southern

Italy, many of the mainland nobles, particularly from the principality of Capua, united

against him under Count Rainulf of Caiazzo, in defence of their own freedoms.27

Therefore, during the course of Norman occupation and rule before the

establishment of the kingdom a gradual transfer can be perceived away from the

existing systems present in the various regions of south Italy towards a new and distinct

‘south Italian Norman’ style of rule.This gradual centralizing trend can be seen to have

had the greatest effect in this period in the Byzantine regions, where the most dramatic

shift must have been, as well as some of the largest settlements of Norman knights.

The area least affected was the Lombard principalities, where a system similar to the

emerging ‘Norman’ one already existed. Nevertheless, this was still to a large extent

dependent on personal ties and gifts, rather than on an institutional system of holding

land in exchange for service.

The mid twelfth century appears to show a significant departure from the previous

models of service presented by Norman rule. Alterations in administrative departments

under Roger II prompted the creation of the defensive and financial records of the

kingdom and gave rise to the Catalogus Baronum,28 detailing the military strength of

Apulia and Capua.The provenance of the Catalogus has already been outlined: what is

more directly relevant is its intended purpose.

The book is structured as a tiered hierarchy of service organized principally by

region. As a general rule, counts are listed, followed by their barons, who in turn may

have had dependants. However, outside comital regions, land was usually divided by

city and surrounding territory, with the exception of some records between entries

700 and 800 in the Catalogus, which are on the border between Apulia and Capua and

24

For the rebellion, see G. Malaterra, De Rebus Gestis Rogerii Calabriae et Siciliae Comitis et Roberti Guiscardi

Ducis Fratris eius, ed. E. Pontieri (Bologna, 1927), bk. III, ch. 34, pp. 77–8; Loud, Age of Robert Guiscard, p. 244.

Malaterra gives a figure of 1,300 knights who took part in the expedition (Malaterra, bk. III, ch. 24,

p. 71); however, most of the more powerful nobles appear to have remained behind in Italy. This is still a

strikingly large expeditionary force, given that only 20 years before the number of Normans available to leave

their lands and assist in the invasion of Sicily was fewer than 700 at its highest (Malaterra, bk. II., ch. 17, p. 34)

and was quickly reduced to under 150 following the battle outside Cerami in 1063 (Malaterra, bk. II, ch. 33,

pp. 42–3). Even if the numbers are Malaterra’s best guesses, it can only be hoped that he is consistent with his

margins of error.

25

Loud, Age of Robert Guiscard, pp. 246–60; for the role of Bohemond, see also Martin, ‘Les structures féodales

normanno-souabes’, in Musca, pp. 229–30.

26

E.g., Malaterra, bk. IV, ch. 12, pp. 96–7.

27

See, esp., H. Houben, Roger II of Sicily: a Ruler between East and West, trans. G. A. Loud and D. Milburn

(Cambridge, 2002), pp. 60–73; and G. A. Loud, Roger II and the Creation of the Kingdom of Sicily (Manchester,

2012).

28

For discussion of the reforms in this period on the island of Sicily and in Calabria, see H. Takayama, The

Administration of the Norman Kingdom of Sicily (Leiden, 1993), pp. 47–71.

Copyright © 2012 Institute of Historical Research

The Catalogus Baronum: a re-examination 7

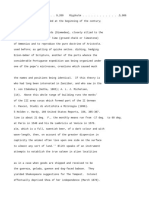

Table 1. A summary of the totals of the Catalogus Baronum

Region Milites Villani Milites Servientes/ Ballistarii

(augmentum) Pedites (augmentum)

(augmentum)

Abruzzi 1,024.85 0 2,322 4,464 0

Duchy of Apulia 1,442.686 2,127 3,238 4,657 2

Principality of Capua 674.5 0 1,456 1,911 13

Principality of Taranto 44 0 151 181 0

Terra de Bari 97.75 11 204 241 0

Totals 3,283.786 2,138 7,371 11,169 15

contain a confusion of overlapping information and lordships.29 The document moves

roughly from the south to the north of the region, beginning with the Terra de Bari

and Taranto, followed by mid Apulia, then the lower old city-states such as Salerno,

proceeding to northern Apulia and Capua, and concluding with the Abruzzi region in

the very north of the kingdom.

From these entries broad patterns can be determined. The entire Quaternus

document as it currently exists gives a total of 7,371 knights, if one includes the extra

contingents listed there under the term ‘augmentum’ (about which more will be said

below). However, this figure is almost certainly too low; the omissions which are

traceable include eighty-seven knights for the count of Molise alone,30 as well as others

which are not immediately obvious. Another fifty individuals appear as ‘milites non

habentes feuda’,31 which brings the grand total to a minimum of 7,508. Similarly, the

total number of serjeants listed by the Catalogus is 11,169, but this figure too is plagued

by omissions. Some 211 of these men are referred to as ‘pedites’, while 10,958 are

called ‘servientes’. This distinction appears to be arbitrary: there is no logic as to

when one term is used instead of the other, and they are occasionally deployed

interchangeably within the same entry. Also included in the ‘augmentum’ is one final

field, ‘ballistarii’, and in one instance, ‘ballista’. Ballista usually translates as crossbows,

and ballistarii as something pertaining to artillery (or crossbows).32 However, in this

context the term is difficult to determine; just fifteen ‘ballistarii’ are recorded as being

offered (‘obtulit’) by only four men, all of whom are large landholders, and only with

the ‘augmentum’. Thus, the term may refer to some manner of artillery rather than to

crossbowmen. The totals by region for all categories are given in Table 1.

Therefore, as can be seen, the intended purpose of the Catalogus was unquestionably

as a record of military service owed, but the extent to which the information in the

document has been discussed requires reviewing. Contained within the Catalogus is a

detailed collection of figures and arrangements, however incomplete and distorted it

may be. The vast majority of records are in the format of: (1) The count or baron of

the landholder; (2) The landholder of the fief; (3) The location of the fief; (4) An initial

fief figure; and (5) An ‘augmentum’ figure. The accepted view, put forward by Jamison

29

Redundant information can be found in Catalogus, entries 726/799, 743/755, 778/793 and 761/798.

30

This number has been drawn from the totals of the lands of the county of Molise in Catalogus, entry 805.

The personal lands of Count Hugh and an unknown number of his vassals are omitted in the text.

31

Catalogus, entries 406/407.

32

Mediae Latinitatis Lexicon Minus, ed. J. F. Niermeyer (Leiden, 2002), p. 79.

Copyright © 2012 Institute of Historical Research

8 The Catalogus Baronum: a re-examination

and Cahen, is that the initial figure for a fief, occasionally referred to in the text as the

‘feudum proprium’, is the agreed figure of service decided on enfeoffment, while the

second number, almost always named as the ‘augmentum’, is a theoretical maximum

that each landholder can provide if called upon.33 While modern scholarship has

generally moved away from the idea of ‘feudalism’, many of the conclusions rooted in

this notion are still accepted.Thus, while the language of the Catalogus appears ‘feudal’,

this does not seem to be the relationship it is describing. Nevertheless, much of the

existing research drawing on the Catalogus fits it into a framework of vassalage and land

tenure for service, despite the lack of evidence for this actually taking place.The simple

presence of ‘feudal’ language in the document is usually enough for it to be considered

proof of the development of ‘feudal’ structures in south Italy, and it is usually

referenced purely to demonstrate the ‘feudalization’ of that region by the mid twelfth

century.

While the name Quaternus Magne Expeditionis suggests to the modern mind a

purely military document, there seems no reason to assume that this is the case. The

main problem arises from the first figure, the so-called ‘feudum proprium’, which

appears far too regularly to have no military application whatsoever. While it is

reasonable to consider the ‘augmentum’ as a military figure that deals with actual

people (and explaining the title), the ‘feudum proprium’ figure is problematic in this

respect. Several bishoprics and abbeys offer no fief figures, merely giving the phrase

‘pro magnae expeditionis’ and what can only be an ‘augmentum’ figure,34 as do

several areas of small-holdings.35 Some of these omissions are obviously copying

errors on the part of scribes where the regular formula is intact but figures are

missing; however, where the formula is significantly altered it would appear to be a

deliberate omission. Jamison justifies this by suggesting that churches and free-

holdings were exempt from normal service.36 This could be true if there was any

internal consistency within the document, but some churches do offer fief figures,37

as do the vast majority of small-holdings, albeit in fractional figures. Some of these

are clearly copyist errors, but many more are clearly not: it is a problem that cannot

be easily explained.

The initial fief figure is a little more straightforward than the ‘augmentum’

figure: it contains only three variations, ‘milites’, ‘villani’ and in one instance,

‘commendatarii’,38 which appears to be another form of ‘villani’. There are 3,283.786

knights fiefs recorded in total for the size of fiefs, while a further 2,138 ‘villani’ are

recorded and twenty ‘commendatarii’. If this in fact represented the mainland activities

of the armies of the kingdom of Sicily outside a crisis, it would represent an army that

was both small and entirely devoid of supporting troops.‘Villani’ were not soldiers, and

thus presumably would be paying a rent rather than providing service.This means that

this figure cannot be showing the kingdom’s main recruitment policy. Additionally,

Niketas Choniates tells us that in 1147 Roger II garrisoned Corfu with 1,000 knights

33

E. M. Jamison, ‘Additional work on the Catalogus Baronum’, Bullettino dell⬘Istituto Storico Italiano per il medio

evo, lxxxiii (1971), 1–63, at pp. 6–9; Cahen, pp. 41–51.

34

The figures can be reasonably considered an ‘augmentum’ because they often include ‘servientes’ in addition

to ‘milites’, and never offer fractional figures. They fit the pattern of ‘augmentum’ far better than a ‘feudum

proprium’ (see Catalogus, entry 491).

35

Catalogus, entries 124, 145, 282–90, 408, 490–1, 691–2, 823.

36

Jamison, ‘Additional work’, p. 11.

37

Catalogus, entries 107, 137, 386, 402, 492, 1104, 1204, 1218, 1221–2.

38

‘commended men’ (Niermeyer, p. 216).

Copyright © 2012 Institute of Historical Research

The Catalogus Baronum: a re-examination 9

and siege engines, while the fleet continued to plunder the Aegean coast.39 The

mainland provinces included in the Catalogus comprise approximately 60 per cent of

the area covered by the kingdom, and so if Calabria and Sicily could provide the same

ratio of knights, the total army of the kingdom would have been roughly 5,500

knights, at the very most.40 The garrison on Corfu, then, would represent a fifth of the

total and a serious commitment for the south Italians, as well as a serious blow to the

total troops available to the king when they surrendered.Yet no outcry is heard from

the narrative sources, which surely would have had something to say about so many of

the kingdom’s soldiers being lost.

Similarly to the ‘villani’, it has also been suggested that the fractional fiefs which

appeared in the Catalogus were money fiefs: 103 references are smaller than a fief (a

total of 41.986), while fifty-six entries contain no survey figure of any kind. Only a

very small proportion of these can be attributed to scribal error while copying the

manuscript. Furthermore, fifty-five entries are for fractional fiefs over one (for example,

one and a half fiefs or two and a half fiefs), made up of composite parts that are

geographically divided, accounting for a further twenty-seven knights. While several

sections of the small fractional fiefs are recorded together, the larger fractional fiefs are

almost never near one another, and thus it is difficult to suggest that these landholders

would have banded together to produce one over the distances involved. Therefore

another problem arises from the fractions of fiefs given in the more ‘regular’ entries.

Jamison’s assertion that fractional fiefs would have been expected to band together to

provide the knights which they owed sounds entirely plausible.41 However, it does not

help to explain what should happen to fractional fiefs that are geographically isolated,

or how a knight who holds two and half fiefs should behave. Further compounding

this problem is the additional variation in a sizeable selection of the entries giving the

initial figure in terms of ‘villani’ instead of ‘milites’. These ‘villani’ would clearly not

have been expected to serve for general combat duties and held no ties of vassalage,

and thus have no logical place in the Catalogus as proposed by Jamison and Cahen.

Cuozzo goes as far as saying that a knight’s fief held a standard monetary value,

suggested at twenty ounces of gold.42 This offers weight to the idea of fractional fiefs

being monetary, but stops short of explaining all the other difficulties of the Catalogus

because of the insistence on forcing the available data into a ‘feudal’ framework.

Cuozzo persists in the assumption that because the Catalogus uses the word ‘feudum’,

it must refer to a fief linked with vassalage. From a very similar document, the Cartae

Baronum of England, written only a few years later in 1166, it can be seen that

fractional fiefs are very common: the archbishop of York’s return alone contains

twenty-two fractional fiefs, including some extremely small ones.43 This document uses

similar language to the Catalogus, but it is clear that its general purpose is financial,

39

Niketas Choniates, O City of Byzantium, trans. H. J. Magoulias (Detroit, Mich., 1984) (hereafter Choniates),

p. 43, repeated p. 51.

40

This calculation is rough and based purely on areas of land; documentation has not survived that shows

what military forces were levied from Sicily and Calabria. Given the heavily Muslim population of the island,

it is possible that more infantry and archers than heavy cavalry would have been recruited from there. Equally,

Calabria is extremely mountainous, and the available pasture for horses is significantly lower than in other parts

of the kingdom. Nevertheless, this is purely speculative, with no evidence apart from the fact that the Catalogus

does not mention from where the kingdom’s army was getting any ranged troops.

41

Jamison, ‘Additional work’, p. 8.

42

E. Cuozzo, La cavalleria nel regno normanno di Sicilia (Atripalda, 2002), p. 153.

43

English Historical Documents, ii: 1042–1189, ed. D. C. Douglas and G. W. Greenaway (1953), pp. 971–2.

Copyright © 2012 Institute of Historical Research

10 The Catalogus Baronum: a re-examination

rather than documenting vassalage. Cahen even admits that the early beneficium grants

to Aversa are far more concerned with land than vassalage, but uses the Catalogus to

show that this had changed by the mid twelfth century.44 However, his argument is also

based on the language of the Catalogus, rather than on its content.

In addition to these inexplicable irregularities in the terminology, there is the

context surrounding the creation of the document. As mentioned above, before the

foundation of the kingdom, the model described in the Catalogus simply did not exist.

Thus, it must be seen as a new creation, implemented by the crown, rather than as a

recording of the existing systems. This has parallels on the island of Sicily as well, in

the actions of the dı̄wān, the government ministry responsible for administering and

taxing Sicily and Calabria, set up in 1145.45 The dı̄wān was responsible for recording

land boundaries and the value of land held by individuals. It is possible that the initial

compilation of the Catalogus in the early eleven-fifties was a project in a similar vein,

albeit for different conditions.Within this context, it is much easier to see the Catalogus

as having a different purpose from the ‘feudal’ record suggested in previous scholarship.

In this model the first figure given represents the results of a preliminary land

or wealth survey, indicating the wealth and means of the landholder, while the

‘augmentum’ figure remains a theoretical total of all the military forces that that

landholder might be expected to produce in the event of an invasion. This also helps

to explain the strange inclusion of the ‘feudum pauperum’ clauses (and the variant

clause, where someone offers himself ‘se ipsum’ for service with the ‘augmentum’),46

which might seem odd to find in a document dealing strictly with service.

Jamison states that the ‘milites’ sent from a ‘feudum pauperum’ were combatants who

were less well armoured than a wealthier knight.47 Yet nowhere in the Catalogus is there

any indication of the expected quality of the soldiers to be provided, so the passage

could just as easily refer to the land of the fief rather than the expectations of the

knight serving for it. This view is further strengthened by certain passages which give

their figures in ‘villani’, but state that this is equivalent to a knight’s fief,48 or any of the

countless other irregular entries such as that for Fulcus the doctor, whose initial figure

is given in ‘villani’ and who offers his services (presumably as surgeon) in lieu of any

knights.49 This more universal view of the applications of this document is also

supported by its use and the timing of its updates. In addition to the creation of the

document in very close temporal proximity to the establishment of the dı̄wān in Sicily,

its updating in 1167/8 also coincides with the creation of a sister department to

administer the mainland regions recorded in the Catalogus.50 This reinterpretation of

the purpose of the Catalogus shows a less traditional document in terms of military

figures, one which is sadly less precise than the previous model. It also stresses the lack

of a ‘feudal’ structure: the first figure does not appear to relate directly to service, but

44

Cahen, pp. 47–50.

45

J. Johns, Arabic Administration in Norman Sicily: the Royal Dı̄wān (Cambridge, 2002), p. 115; Takayama, p. 81,

gives the start-up date for the dı̄wān as 1149.

46

See Catalogus, entries 282–90, 481 or 846 for examples.The ‘feudum pauperum’ phrasing is by far the most

common, but that also has variations (cf. entry 481).

47

Jamison, ‘Additional work’, p. 8.

48

Catalogus, entry 58.

49

Catalogus, entry 540: ‘Fulcus medicus filus Sergii medici tenet villanos viginti et debet servire sicut

stabilitum fuit ei a Curia’.

50

For further discussion about the creation of the duana baronum and its links to the revisions of the Catalogus

Baronum, see Takayama, pp. 156–7.

Copyright © 2012 Institute of Historical Research

The Catalogus Baronum: a re-examination 11

rather to wealth, while the ‘augmentum’ seems to be concerned with actual military

totals, although with no indication as to how they were used or if there was any

expectation of service.

In addition to the treatment of the purpose and content of the Catalogus, it is

important to examine the limitations of the document and the problems within the

text that cause difficulties in using it. So the questions raised by the transmission of the

document must be considered, as well as the extent to which the information can be

verified. This can be done by comparing the actions of individuals named in the text

against charters, and by a comparison of the quantity of soldiers listed in the document

with narrative sources.

Aside from the problems surrounding the use and nature of the document and the

risks of anachronism within the text, the content has suffered corruption in its

transmission. Most striking is the omission of the entire personal lands of the count

of Molise and potentially several of his barons, but this is not the only traceable

omission.51 In addition to these errors, there are countless faults in mathematical

addition, both within single entries between the ‘feudum’ and ‘augmentum’ figures

(where both are given),52 and often when the overall figure for a landholder with

vassals is totalled at the end of his holdings.53 Equally pervasive is the provision of

extremely improbable figures, which are difficult to discern as either incorrect or

correct but are clearly irregular. Unfortunately, in these cases there is no way of

supplying an accurate figure as it is almost impossible to identify where the error has

taken place and which numbers are correct. Thus, when working with the Catalogus,

it is important to bear in mind that while it provides very precise figures, totals drawn

from it should not be considered anything more than an approximation of what was

originally written.

However, the Catalogus does allow study of landowning individuals, as well as the

pattern of land distribution, and this can be used to help verify some of the

information that it contains. Individuals named within the Catalogus can be

cross-referenced in charters (where they exist), allowing for crude dating of sections of

the document.54 In addition, the patterns of landholding are of note. A total of 190

fiefs are recorded as being directly held from the king; only five of these are by a

count,55 although while the other counts are not expressly stated as holding land from

the king, it is reasonable to assume that this was the case. The vast majority of direct

royal holdings are in the Abruzzi, which may be due to the small number of comital

holdings in that area: much of the remaining land must have been in royal hands.

These explicitly royal lands account for 756 knights and 1,515 serjeants with the

‘augmentum’, which is 10.33 per cent of the total knights and 13.56 per cent of the

51

The first appearance of a vassal of Hugh of Molise is in Catalogus, entry 740, but it is impossible to

determine how much has been omitted. Entry 805 states that the total for his lands should be 486 knights, only

299 of whom are recorded in the Catalogus – a substantial discrepancy. Even more ‘servientes’ are omitted, with

only 278 recorded of an expected 650. Other probable omissions come in entries 1075 and 1078, and many

other calculation errors are probably caused by this problem.

52

E.g., Catalogus, entries 203, 209, 268.

53

E.g., Catalogus, entries 445, 718, 735. Hugh of Molise’s totals are probably the most obvious in 805.

54

Bohemond Malerba, a knight of Summonte, can be found in Catalogus, entry 393, and also in Codice

Diplomatico Verginiano, ed. P. M. Tropeano (13 vols., Montevergine, 1977–2001), iv. 308, v. 467. Additionally, Roger

de Aquila, count of Avellino, appears in Catalogus, entry 392 and Codice Diplomatico Verginiano, iv. 345, 371; v. 444,

474, 476.

55

Count Godfrey of Lessina (Catalogus, entry 377).

Copyright © 2012 Institute of Historical Research

12 The Catalogus Baronum: a re-examination

serjeants, a ratio of one knight to 2.004 serjeants. In addition to the king, there are

thirty-two men of major landowning class who are listed as having barons, twenty-four

of whom are named as counts.With the ‘augmentum’, these counts are responsible for

2,564 knights, 4,095 serjeants and four ‘balistarii’, while lands held directly from the

king owe a further 761 knights and 1,520 serjeants. This means that 45.41 per cent of

the knights recorded in the Catalogus are from lands of named counts or the king,

50.27 per cent of the serjeants, which is a ratio of 1:1.59. The abbeys and bishoprics

of Apulia and Calabria appear only to have provided 252 knights, but 884 serjeants.

This equates to 3.44 per cent of the total knights, but 7.55 per cent of the serjeants.

The resulting ratio of 1:3.51 is strikingly higher than that of the counts, and can be

seen to have represented a significant difference in the composition of forces levied

from the two types of landholders. This is comparable to the kingdom of Jerusalem,

where the figures recorded by John of Ibelin show that the patriarch and his bishops

also provided a significantly higher ratio of serjeants to knights.56

It is exceedingly difficult to verify the figures themselves, and particularly the extent

to which they represent what happened in reality during crisis. Only one detailed

account of the Byzantine invasion of 1155 exists: that of the notary John Kinnamos.

Unfortunately, the other narrative sources which describe this event are extremely

sparse when it comes to military details, and both sides carefully omit events. The

Greek sources by Kinnamos and Niketas Choniates both fail to include King William

I’s recapture of Bari and subsequent razing of it, with Choniates even portraying the

whole expedition as a resounding success, with troops only withdrawing because of

concerns in the rest of the empire.57 Conversely, the south Italian sources by ‘Hugo

Falcandus’ and Romuald of Salerno gloss over the initial Greek successes and battles

and focus on William’s later victories in the campaign.58 Thus, these sources must all

be treated with caution, as each has an intrinsic bias. However, Kinnamos’s account is

also the only source of data for the 1155 expedition against which to examine the

numbers in the Catalogus.

Narrative sources obviously cannot be treated as accurate data, but the information

given by Kinnamos is interesting: he offers the figure of 2,000 knights and

‘innumerable infantry’ for the first Sicilian army, which was drawn from ‘the barons and

the chancellor’.59 Given the extent of the territory which had already been overrun by

the Greeks at that point, perhaps 5,000 knights registered under the ‘augmentum’ in the

Catalogus were from land still under Sicilian rule. In order to field the 2,000 men

described, all the knights west of Taranto, in the interior counties north of Taranto and

in the lower half of the Campania would have had to be mustered.This is in itself not

unrealistic, for none of these forces would have had to march huge distances, and the

battle took place several months into the invasion, allowing plenty of time for the

muster to have taken place. This calculation, however, does not take into account

the unnamed rebellious nobles who joined the Greeks, or at the very least did not get

drawn into the conflict, offering terms of surrender instead of fighting, which would

have dramatically reduced the available pool of troops. The forces from the island

56

P. W. Edbury, John of Ibelin and the Kingdom of Jerusalem (Woodbridge, 1997), p. 132.

57

Choniates, pp. 53–7; Iōannēs Kinnamos, Deeds of John and Manuel Comnenus, trans. C. M. Brand (New York,

1976), pp. 106–29.

58

‘Hugo Falcandus’, The History of the Tyrants of Sicily, trans. G. A. Loud and T.Wiedemann (Manchester, 1998)

(hereafter Falcandus), pp. 73–5, 223–4.

59

Kinnamos, p. 110.

Copyright © 2012 Institute of Historical Research

The Catalogus Baronum: a re-examination 13

arrived with William I, and the 2,000 knights who are mentioned are explicitly stated

to have come from the barons, and so must have been drawn from the mainland.

Unfortunately, none of the narratives gives any idea of the numbers in William I’s

army, other than vague general statements implying that his forces were large.60 This,

combined with the lack of a similar document cataloguing service owed from Sicily

and Calabria, prevents a complete comparison of the narratives and the surviving

clerical data.

As this article has shown, the Norman period in south Italy was one which saw

significant development and restructuring of the systems of military recruitment and

administration. While the ‘feudal’ language of the Catalogus is largely absent from

documents before the establishment of the kingdom, the notion of dependent tenure

was clearly not alien either to the Norman immigrants or to the inhabitants of the

Lombard principalities. The Lombard states appear to have drawn their military forces

from the landed nobility as well as mercenaries, and entry to this class of nobility could

be achieved through service, as Count Rainulf of Aversa demonstrated. The Normans

also had an idea of rewarding service with land, as can be seen from the division of

Apulia at the council of Melfi in 1042 and the land charters of Robert Guiscard.

However, with the exception of the land charter issued by Bishop Rainulf, none of

these charters implies that land granted as a reward held any legal strings requiring

further service. The actions of the greater nobility in Apulia during the Byzantine

invasion of 1082, many of whom refused to accompany the expedition, reinforce this

idea of semi-independence. Therefore, while the mainland during and after the

Norman conquest had a basic system of dependent landholding (without the use of

‘feudal’ terminology), there was no typically ‘feudal’ system of vassalage or service in

the period before the creation of the Catalogus.

The Catalogus revolutionizes the understanding of the military recruitment and

administration of the mainland. The detail that it offers is unrivalled in any document

produced before or for some time afterwards, although how that data is interpreted is

a matter of difficulty. Rather than accepting the view that the Catalogus was a purely

military document, designed as a record of all military service in Apulia and Capua

both ‘regular’ and in times of crisis, it is probable that the Catalogus had a much more

limited purpose: to record the maximum possible military levy for any given lord,

and the approximate wealth of that lord. Thus, rather than acting as a somewhat

inexplicable ‘feudal’ register, it can be seen much more logically as a land and

emergency defence register. The use of ‘feudal’ language within the document is

simply not indicative of ‘feudal’ practice in terms of service for fiefs, and while it

remains possible that this may have happened, there is no evidence to suggest that the

Catalogus records this practice. The parallels between this interpretation and what

happened in other governmental departments in the Sicilian administration further

help to clarify its position: the Catalogus may have acted as a record for the curia in

much the same manner as the records of the dı̄wān, and it is likely that it was

instrumental in the record-keeping for the duana baronum in the late eleven-sixties.

While the purpose of the Catalogus may not be immediately clear, it has many

serious errors in transmission which make using specific numbers from it problematic.

Nevertheless, the composition of soldiers from different lords holding land allows for

60

Falcandus, pp. 73, 224.

Copyright © 2012 Institute of Historical Research

14 The Catalogus Baronum: a re-examination

interesting comparisons within the document, helping to establish the variations in

military recruitment from different types of landholders. While this reveals patterns in

keeping with the kingdoms of Jerusalem and England, the absence of any other

document remotely similar to the Catalogus from the kingdom of Sicily makes

verifying its data difficult. Some information from narrative sources, particularly that of

John Kinnamos, can be used for comparison with the clerical data of the Catalogus.

This narrative information tends to support the data: nothing presented within the

sources is beyond the realms of what might be levied from the mainland fiefs.

Therefore the Catalogus Baronum, despite its many scribal errors and occasionally

incomprehensible calculations, represents a document of unparalleled depth and detail

in comparison to the other available sources for the administration of the south Italian

military. The wealth of statistical information which can be drawn from it has only

begun to be investigated and much work remains to be done, particularly in

comparisons with narrative and charter sources. Nevertheless, the Catalogus is evidently

a vital and influential source for the military resources of Apulia and Calabria, and one

which has often been overlooked in more recent scholarship. It reveals a complicated

system of landholder promises, extensive hierarchies, individual exceptions, regional

variations and seemingly conflicting ways of interpreting the data: the hallmarks of a

document in need of further study.

Copyright © 2012 Institute of Historical Research

You might also like

- The Doomsday BookDocument5 pagesThe Doomsday BookAndrea TemponeNo ratings yet

- The Development of Iberian Military OrdersDocument14 pagesThe Development of Iberian Military OrdersmageerauldjsttdNo ratings yet

- Feudal Monarchy in The Latin Kingdom of Jerusalem, 1100-1291 - John L. La MonteDocument309 pagesFeudal Monarchy in The Latin Kingdom of Jerusalem, 1100-1291 - John L. La MonteManuel PérezNo ratings yet

- History of the English People (Vol. 1-8): Complete EditionFrom EverandHistory of the English People (Vol. 1-8): Complete EditionNo ratings yet

- Science2656 7960Document4 pagesScience2656 7960kai toshikiNo ratings yet

- The Ultimate Commentary On 1 Chronicles: The Ultimate Commentary CollectionFrom EverandThe Ultimate Commentary On 1 Chronicles: The Ultimate Commentary CollectionRating: 5 out of 5 stars5/5 (1)

- Honeyman 2010Document45 pagesHoneyman 2010groot marvelNo ratings yet

- The Danelaw Reconsidered Colonization AnDocument40 pagesThe Danelaw Reconsidered Colonization AnumutkNo ratings yet

- The Influence of Sea Power Upon History, 1660-1783From EverandThe Influence of Sea Power Upon History, 1660-1783Rating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (43)

- Hist6366 1739Document4 pagesHist6366 1739Shinichi KudouNo ratings yet

- Soc7696 2744Document4 pagesSoc7696 2744HURIN AL MAZIYYAHNo ratings yet

- Bio2797 499Document4 pagesBio2797 499Vladimir Putin (MallowBuddies)No ratings yet

- Papal Armies in The XIII CenturyDocument31 pagesPapal Armies in The XIII CenturyMauri FurlanNo ratings yet

- Acc6475 2723Document4 pagesAcc6475 2723pak manNo ratings yet

- Comm 3518961 - 7326Document4 pagesComm 3518961 - 7326TWINEX AkaduNo ratings yet

- Chem5532 1749Document4 pagesChem5532 1749rizqi mirzaqulNo ratings yet

- Acc3013 5920Document4 pagesAcc3013 5920Test AccountNo ratings yet

- Italian CastillansDocument293 pagesItalian CastillansMiguel Trindade50% (2)

- Acc40 6036Document4 pagesAcc40 6036faizin ahmadNo ratings yet

- Chem2718 7864Document4 pagesChem2718 7864Mariz RabanalNo ratings yet

- Chem6334 2176Document4 pagesChem6334 2176agung dianNo ratings yet

- Hist4258 587Document4 pagesHist4258 587Just MeNo ratings yet

- Hist2426 2117Document4 pagesHist2426 2117USWATUN HASANAHNo ratings yet

- Eco4374 8742Document4 pagesEco4374 8742Rezky PratamaNo ratings yet

- Fil 1235461 - 1513Document4 pagesFil 1235461 - 1513Vidzdong NavarroNo ratings yet

- Eng9150 4356Document4 pagesEng9150 4356Muhammad FauzanNo ratings yet

- The Formation of The Territorial StructuDocument16 pagesThe Formation of The Territorial StructuStefan StaretuNo ratings yet

- Acc9500 2280Document4 pagesAcc9500 2280Noodles CaptNo ratings yet

- Eng3204 7932Document4 pagesEng3204 7932CUEVA AVILA LUIS STALINNo ratings yet

- Soc3113 6233Document4 pagesSoc3113 6233Gregorius PutraNo ratings yet

- Celtic EmpireDocument183 pagesCeltic Empiretatarka01No ratings yet

- Math2341 7842Document4 pagesMath2341 7842IvanwbsnNo ratings yet

- Law6927 4535Document4 pagesLaw6927 4535Shy premierNo ratings yet

- The Domesday BookDocument11 pagesThe Domesday BookБаранова ЕкатеринаNo ratings yet

- Econ6225 7521Document4 pagesEcon6225 7521angelo carreonNo ratings yet

- System4253 7182Document4 pagesSystem4253 7182faizin ahmadNo ratings yet

- Bio1393 9349Document4 pagesBio1393 9349JA YZ ELNo ratings yet

- CelticDocument143 pagesCeltickariku123No ratings yet

- Chem72 4195Document4 pagesChem72 4195Andres FernandoNo ratings yet

- Chem4799 2716Document4 pagesChem4799 2716Just MeNo ratings yet

- Celtic Scotland Hi 03 S Kenu of TDocument558 pagesCeltic Scotland Hi 03 S Kenu of TRon100% (1)

- Bakteri 6875Document4 pagesBakteri 6875Nur Alfhi FhadilaNo ratings yet

- Soc6734 9269Document4 pagesSoc6734 9269Damian LeeNo ratings yet

- CGR Erth XXXVI Rhif3 2016 2Document60 pagesCGR Erth XXXVI Rhif3 2016 2Dave SatterthwaiteNo ratings yet

- Acc7461 9650Document4 pagesAcc7461 9650upi karkiNo ratings yet

- Chem6828 6062Document4 pagesChem6828 6062Syed RazeenNo ratings yet

- Julio Escalona, Orri Vésteinsson and Stuart Brookes (Eds.) : Polity and Neighbourhood in Early Medieval EuropeDocument42 pagesJulio Escalona, Orri Vésteinsson and Stuart Brookes (Eds.) : Polity and Neighbourhood in Early Medieval Europewa undmeNo ratings yet

- Math2341 7825Document4 pagesMath2341 7825IvanwbsnNo ratings yet

- Spanyol8464 8351Document4 pagesSpanyol8464 8351Bagas KaraNo ratings yet

- Management3644 5978Document4 pagesManagement3644 5978FghostNo ratings yet

- Eng6128 9549Document4 pagesEng6128 9549Test AccountNo ratings yet

- The Anglo-Saxons at War: Nicholas HooperDocument12 pagesThe Anglo-Saxons at War: Nicholas HoopernetvikeNo ratings yet

- Psy2365 7738Document4 pagesPsy2365 7738John Linel D. DakingkingNo ratings yet

- Eco7636 1691Document4 pagesEco7636 1691Bayu AjiNo ratings yet

- AzraelDocument2 pagesAzraelPatrick JenkinsNo ratings yet

- Capital Police Describe Violence and Hate of Jan. 6th During House TestimonyDocument1 pageCapital Police Describe Violence and Hate of Jan. 6th During House TestimonyPatrick JenkinsNo ratings yet

- Thoughts On The Role of Cavalry in Medieval WarfareDocument29 pagesThoughts On The Role of Cavalry in Medieval WarfarePatrick JenkinsNo ratings yet

- CK3 Taxation EfficiencyDocument4 pagesCK3 Taxation EfficiencyPatrick JenkinsNo ratings yet

- CK3 Barony DensityDocument30 pagesCK3 Barony DensityPatrick JenkinsNo ratings yet

- Bretons and Normans NMSDocument38 pagesBretons and Normans NMSPatrick JenkinsNo ratings yet

- CK3 ModifiersDocument2 pagesCK3 ModifiersPatrick JenkinsNo ratings yet

- Law and Monarchy in The SouthDocument29 pagesLaw and Monarchy in The SouthPatrick JenkinsNo ratings yet

- Kaupang and DublinDocument52 pagesKaupang and DublinPatrick JenkinsNo ratings yet

- Module 5-Theme The Cold WarDocument34 pagesModule 5-Theme The Cold WarPatrick JenkinsNo ratings yet

- Norman Identity and The Anonymous Historia SiculaDocument9 pagesNorman Identity and The Anonymous Historia SiculaPatrick JenkinsNo ratings yet

- Servicium Debitum and Scutage in Norman LandsDocument373 pagesServicium Debitum and Scutage in Norman LandsPatrick JenkinsNo ratings yet

- International Relations Syllabus: Course DescriptionDocument13 pagesInternational Relations Syllabus: Course DescriptionPatrick JenkinsNo ratings yet

- Why Israel Won't Accept A Two-State Solution: by Bernard ChazelleDocument6 pagesWhy Israel Won't Accept A Two-State Solution: by Bernard ChazellePatrick JenkinsNo ratings yet

- The Book of Huon de Bordeaux.: John Bourchier, Lord BernersDocument60 pagesThe Book of Huon de Bordeaux.: John Bourchier, Lord BernersPatrick JenkinsNo ratings yet

- Top Features: Voice User Guide Voice User GuideDocument2 pagesTop Features: Voice User Guide Voice User GuidePatrick JenkinsNo ratings yet

- BYOD Security A New Business ChallengeDocument6 pagesBYOD Security A New Business ChallengerizkiNo ratings yet

- The Autonomy Myth. A Theory of Dependency (Martha Fineman)Document426 pagesThe Autonomy Myth. A Theory of Dependency (Martha Fineman)Patrícia CiríacoNo ratings yet

- DRAC Combined 07.04.2023Document39 pagesDRAC Combined 07.04.2023Ankit DalalNo ratings yet

- ISLAMIC MISREPRESENTATION - Draft CheckedDocument19 pagesISLAMIC MISREPRESENTATION - Draft CheckedNajmi NasirNo ratings yet

- DDR5 SdramDocument2 pagesDDR5 SdramRayyan RasheedNo ratings yet

- 08 Albay Electric Cooperative Inc Vs MartinezDocument6 pages08 Albay Electric Cooperative Inc Vs MartinezEYNo ratings yet

- Internship Report For Accounting Major - English VerDocument45 pagesInternship Report For Accounting Major - English VerDieu AnhNo ratings yet

- 00 Introduction ATR 72 600Document12 pages00 Introduction ATR 72 600destefani150% (2)

- Aguinaldo DoctrineDocument7 pagesAguinaldo Doctrineapril75No ratings yet

- Al HallajDocument8 pagesAl HallajMuhammad Al-FaruqueNo ratings yet

- RA11201 IRR DHSUD Act 2019Document37 pagesRA11201 IRR DHSUD Act 2019ma9o0No ratings yet

- PeopleSoft Procure To Pay CycleDocument9 pagesPeopleSoft Procure To Pay Cyclejaish2No ratings yet

- Legal OpinionDocument8 pagesLegal OpinionFrancis OcadoNo ratings yet

- Editorial by Vishal Sir: Click Here For Today's Video Basic To High English Click HereDocument22 pagesEditorial by Vishal Sir: Click Here For Today's Video Basic To High English Click Herekrishna nishadNo ratings yet

- Disabled Workers in Workplace DiversityDocument39 pagesDisabled Workers in Workplace DiversityAveveve DeteraNo ratings yet

- Powerpoint For Chapter Four of Our Sacraments CourseDocument23 pagesPowerpoint For Chapter Four of Our Sacraments Courseapi-344737350No ratings yet

- FCI Recruitment NotificationDocument4 pagesFCI Recruitment NotificationAmit KumarNo ratings yet

- YehDocument3 pagesYehDeneree Joi EscotoNo ratings yet

- Activity 2:: Date Account Titles and Explanation P.R. Debit CreditDocument2 pagesActivity 2:: Date Account Titles and Explanation P.R. Debit Creditemem resuentoNo ratings yet

- Baltik Remedial Law ReviewerDocument115 pagesBaltik Remedial Law ReviewerrandellgabrielNo ratings yet

- PAS 19 (Revised) Employee BenefitsDocument35 pagesPAS 19 (Revised) Employee BenefitsReynaldNo ratings yet

- Harvey Vs Defensor Santiago DigestDocument5 pagesHarvey Vs Defensor Santiago DigestLeo Cag0% (1)

- Guide To Confession: The Catholic Diocese of PeoriaDocument2 pagesGuide To Confession: The Catholic Diocese of PeoriaJOSE ANTONYNo ratings yet

- Legal Research BOOKDocument48 pagesLegal Research BOOKJpag100% (1)

- Apostolic Succession and The AnteDocument10 pagesApostolic Succession and The AnteLITTLEWOLFE100% (2)

- Case Name Topic Case No. ǀ Date Ponente Doctrine: USA College of Law Sobredo-1FDocument1 pageCase Name Topic Case No. ǀ Date Ponente Doctrine: USA College of Law Sobredo-1FAphrNo ratings yet

- Needle Stick ProtocolDocument1 pageNeedle Stick ProtocolAli S ArabNo ratings yet

- Industries-Heritage Hotel Manila Supervisors Chapter (Nuwhrain-HHMSC) G.R. No. 178296, January 12, 2011Document2 pagesIndustries-Heritage Hotel Manila Supervisors Chapter (Nuwhrain-HHMSC) G.R. No. 178296, January 12, 2011Pilyang SweetNo ratings yet

- EF4C HDT3 Indicators GDP IIP CSP20 PDFDocument41 pagesEF4C HDT3 Indicators GDP IIP CSP20 PDFNikhil AgrawalNo ratings yet

- Twelve Caesars: Images of Power from the Ancient World to the ModernFrom EverandTwelve Caesars: Images of Power from the Ancient World to the ModernRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (9)

- 1177 B.C.: The Year Civilization Collapsed: Revised and UpdatedFrom Everand1177 B.C.: The Year Civilization Collapsed: Revised and UpdatedRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (111)

- The Riddle of the Labyrinth: The Quest to Crack an Ancient CodeFrom EverandThe Riddle of the Labyrinth: The Quest to Crack an Ancient CodeNo ratings yet

- Gnosticism: The History and Legacy of the Mysterious Ancient ReligionFrom EverandGnosticism: The History and Legacy of the Mysterious Ancient ReligionRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (132)

- Roman History 101: From Republic to EmpireFrom EverandRoman History 101: From Republic to EmpireRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (59)

- Byzantium: The Surprising Life of a Medieval EmpireFrom EverandByzantium: The Surprising Life of a Medieval EmpireRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (138)

- The Decline and Fall of the Roman Empire - Volume IFrom EverandThe Decline and Fall of the Roman Empire - Volume IRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (78)

- Strange Religion: How the First Christians Were Weird, Dangerous, and CompellingFrom EverandStrange Religion: How the First Christians Were Weird, Dangerous, and CompellingRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (3)

- The Emperor's Handbook: A New Translation of The MeditationsFrom EverandThe Emperor's Handbook: A New Translation of The MeditationsRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (10)

- Ancient Egyptian Magic: The Ultimate Guide to Gods, Goddesses, Divination, Amulets, Rituals, and Spells of Ancient EgyptFrom EverandAncient Egyptian Magic: The Ultimate Guide to Gods, Goddesses, Divination, Amulets, Rituals, and Spells of Ancient EgyptNo ratings yet

- Early Christianity and the First ChristiansFrom EverandEarly Christianity and the First ChristiansRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (19)

- Giza: The Tesla Connection: Acoustical Science and the Harvesting of Clean EnergyFrom EverandGiza: The Tesla Connection: Acoustical Science and the Harvesting of Clean EnergyNo ratings yet

- Strange Religion: How the First Christians Were Weird, Dangerous, and CompellingFrom EverandStrange Religion: How the First Christians Were Weird, Dangerous, and CompellingRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (3)

- Past Mistakes: How We Misinterpret History and Why it MattersFrom EverandPast Mistakes: How We Misinterpret History and Why it MattersRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (14)

- The book of Thoth: A Short Essay on the Tarot of the EgyptiansFrom EverandThe book of Thoth: A Short Essay on the Tarot of the EgyptiansRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (7)

- Gods and Robots: Myths, Machines, and Ancient Dreams of TechnologyFrom EverandGods and Robots: Myths, Machines, and Ancient Dreams of TechnologyRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (42)

- The Scythian Empire: Central Eurasia and the Birth of the Classical Age from Persia to ChinaFrom EverandThe Scythian Empire: Central Eurasia and the Birth of the Classical Age from Persia to ChinaRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (6)

- Christian Origins 101: How the First Christians Lived, Believed, and Shaped HistoryFrom EverandChristian Origins 101: How the First Christians Lived, Believed, and Shaped HistoryRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (8)

- The Cambrian Period: The History and Legacy of the Start of Complex Life on EarthFrom EverandThe Cambrian Period: The History and Legacy of the Start of Complex Life on EarthRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (17)

- Ur: The History and Legacy of the Ancient Sumerian CapitalFrom EverandUr: The History and Legacy of the Ancient Sumerian CapitalRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (75)

- Sex and Erotism in Ancient EgyptFrom EverandSex and Erotism in Ancient EgyptRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (7)

- The Writing of the Gods: The Race to Decode the Rosetta StoneFrom EverandThe Writing of the Gods: The Race to Decode the Rosetta StoneRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (33)

- Caligula: The Mad Emperor of RomeFrom EverandCaligula: The Mad Emperor of RomeRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (16)