Professional Documents

Culture Documents

The Making of Modern Malayalam Prose and Fiction: Translations From European Languages Into Malayalam in The First Half of The Twentieth Century

Uploaded by

Jijo George0 ratings0% found this document useful (0 votes)

18 views6 pagesOriginal Title

Artic7X

Copyright

© © All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

PDF, TXT or read online from Scribd

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

© All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

Download as PDF, TXT or read online from Scribd

0 ratings0% found this document useful (0 votes)

18 views6 pagesThe Making of Modern Malayalam Prose and Fiction: Translations From European Languages Into Malayalam in The First Half of The Twentieth Century

Uploaded by

Jijo GeorgeCopyright:

© All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

Download as PDF, TXT or read online from Scribd

You are on page 1of 6

The Making of Modern Malayalam Prose and

Fiction: Translations from European Languages

into Malayalam in the First Half of the Twentieth

Century

K.M. Sherrif

Abstract

Translations from European languages have played a crucial

role in the evolution of Malayalam prose and fiction in the first half of

the Twentieth Century. Many of them are directly linked to the socio-

political movements in Kerala which have been collectively designated

‘Kerala’s Renaissance.’ The nature of the translated texts reveal the

operation of ideological and aesthetic filters in the interface between

literatures, while the overwhelming presence of secondary translations

indicate the hegemonic status of English as a receptor language. The

translations never occupied a central position in the Malayalam

literature and served mostly as mere literary and political stimulants.

Keywords: Translation - evolution of genres, canon - political

intervention

The role of translation in the development of languages and

literatures has been extensively discussed by translation scholars in

the West during the last quarter of a century. The proliferation of

diachronic translation studies that accompanied the revolutionary

breakthroughs in translation theory in the mid-Eighties of the

Twentieth Century resulted in the extensive mapping of the

intervention of translation in the development of discourses and

shifts of ideological paradigms in cultures, in the development of

genres and the construction and disruption of the canon in literatures

and in altering the idiomatic and structural paradigms of languages.

One of the most detailed studies in the area was made by

Andre Lefevere (1988, pp 75-114) Lefevere showed with convincing

118 Translation Today

K.M. Sherrif

examples from a number of literary systems how translation makes

decisive interventions in literary systems and the role played by

translated literature in literary polysystems. A large number of

translations are made by authors who are eager to introduce a

particular genre or mode (in which they have already made, or

wish to make, experiments on their own) into a literary system.

They would, naturally, like to invoke the masters in that particular

genre or mode in the source literary system. Translation acquires

a more social motive when enterprising translators who inhabit

relatively young languages/literary systems import texts from more

established languages/literary systems for the enrichment of various

discourses in their system. Such well-intentioned attempts can go to

extremes, as when Czech literature (like other discourses in the Czech

language) at the end of the Nineteenth century virtually became a

clone of contemporary German literature (Macura, 1990). In this

case literary translation occupied only a small percentage of the total

volume of translation. Even today knowledge texts in translation

outnumber their literary counterparts many times over (Venuti,

P.67) But translation is often called upon to perform political roles

too, the earliest examples in history for which are Bible translations

in various languages of the world. A large part of the American

translation scholar Eugene A Nida’s work on translation deals with

the strategies of Bible translation and their implications in the target

culture. A more recent example is the Communist Manifesto. Apart

from such ‘core texts’ like the Bible or the Communist Manifesto,

there are a large number of less known translated texts which are

made to serve the interests of dynamic socio-political movements in

cultures. Nationalist and Communist movements in various cultures

have extensively used translated texts for their immediate or long-

term objectives. Revivalist movements have also used translated

texts for similar objectives, although to a lesser extent.

Translation can also seriously disrupt or dislocate the

structural patterns of the target language or the aesthetic paradigms

of the target literary system. The classical instance pointed out

by Lefevere is translation from Arabic to Turkish. In many cases

‘progressive’ elements often view these effects are beneficial to the

Translation Today 119

The Making of Modern Malayalam Prose and Fiction

culture, while they are vehemently decried by more conservative

elements including cultural purists. The current tendency is to

regard such disruptions and dislocations as natural phenomena. No

academy can today dictate language use or literary practice.

Although the history of European colonialism begins in

many regions of what is today the state of Kerala as early as the late

Eighteenth Century, translation from English on a considerable

scale took off only as late as the beginning of the Twentieth Century.

The reasons are obvious. The rump of the Malayalam literary elite

continued to operate in a largely pre-colonial literary atmosphere,

while the new English-reading elite had little interest in using

translations to make interventions in Malayalam literature. Writers

like O Chandu Menon short-circuited the process by directly imitating

English novels rather than by translating any into Malayalam.

The proliferation of translations into Malayalam from the

beginning of the Twentieth Century can be directly related to the

socio-political movements in Kerala during the period which have

been collectively designated ‘Kerala’s Renaissance.’ The reformist

movements among the various religious communities of the

Malayalam speaking-territories, the anti-caste movements, the

emerging Malayali nationalism and the politicization of workers

and peasants which culminated in the formation of the Kerala unit

of the Communist Party of India in 1939 are the chief ingredients

of the Kerala Renaissance. The exhaustive catalogue of translations

into Malayalam compiled by K M Govi and published by the Kerala

Sahitya Akademi in 1995 helps in discerning some of the major

trends in translation into Malayalam in the Twentieth Century. It

will be useful to take 1960 as a cut-off year as it marks the subsiding

of the first wave of Leftist politics in Kerala and the beginning of

modernism in Malayalam literature.

One of the most interesting facts that emerge from an

examination of these translations is that although English is the

predominant source language, Russian and French have been widely

120 Translation Today

K.M. Sherrif

represented. As can be expected, fiction dominates the list. More

than a dozen works each of Balzac, Maupassant, Zola, Tolstoy and

Gorky were translated into Malayalam during this period. Other

major authors include Dostoevsky, Turgenev, Gogol, Chekhov,

Sholokhov and Poliyev in Russian and Voltaire, Hugo, Dumas,

Jules Verne and Anatole France in French. All of Ibsen’s plays also

came into Malayalam during this period. It is easy to relate these

translations to the rise of social realism in Malayalam fiction in the

Thirties on the one hand and the political and cultural assertion of

the Communist Party on the other. The translations of the works

of American fictionists Howard Fast, Upton Sinclair and John

Steinbeck and the Chinese fictionist Lu Xun also comes into this

frame. Among the translations during this period figure a smattering

of what Left-leaning intellectuals during those times branded ‘anti-

communist literature.’ Koestler’s Darkness at Noon, Orwell’s Animal

Farm, Narakov’s Chain of Terror and Pasternak’s Doctor Zhivago may

be considered representative.

An aesthetic filter (the kind described by Lefevere as

decisive in translation) appears to have prevented the translation of

what are distinctly modernist texts from European languages into

Malayalam during this period. The only possible exception is a novel

of Pirandello’s translated by A Balakrishna Pillai. The title of the

translation is given as Omanakal (The Beloved) in the catalogue, while

the original title is not mentioned. The filter was faithfully guarding

the frontiers Malayalam literature, in which Modernist experiments

in both poetry and fiction emerged only in the mid-Sixties, and

those in drama only in the early Seventies. Pulimana Parameswaran

Pillai’s Samatvavadi (The Socialist, 1940) and C J Thomas’s Aayirathi

Orunootti Irupathezhil Crime lrupathettu (Crime No. Twenty Eight

of Eleven Hundred and Twenty Seven, 1951), although they are still

among the most symptomatic expressionist plays in the language,

can only be considered flashes in the pan.

Another interesting feature of translations during this

period is that the overwhelming majority of the translations have

Translation Today 121

The Making of Modern Malayalam Prose and Fiction

come through English, with the exception of a few from Russian.

As a result, the translations were putting tremendous pressure on

Malayalam grammar, usage and lexis, as Kuttikrishna Marar, the

Malayalam critic regretfully notes in Malayalashaili (Malayalam

Usage, 1942), his monumental work on Malayalam usage. Early

changes were visible in journalism, but soon the literary language

too came under assault from English. Mostof the ‘new fangled’

expressions borrowed from English that Marar denounced in his

book are today part of accepted Malayalam usage.

Perhaps the most influential single work that influenced

Malayalam usage is Nalappattu Narayana Menon’s translation of

Victor Hugo’s magnum opus Les Miserables as paavangal. Like the

French texts that entered the Malayalam literary system a little later

in the mid-Thirties of the century, paavangal was also an indirect

translation, Isabel F Hapgood’s English translation being the source

text. Kuttippuzha Krishnappillai’s study of paavangal (1958) is the

first symptomatic translation study in Malayalam. Like the modernist

experiments in drama in Malayalam, Kuttippuzha’s essay was much

ahead of it’s times. Nearly a quarter of a century before translation

studies in the West seriously started discussing the interventions

made by translation in the development of languages and literatures,

Kuttippuzha showed with telling examples how translations from

English could give Malayalam prose and fiction a new strength and

vitality.

References

Govi, K M. 1995. Malalyala Granthasooji (Index of Books Published

in Malayalam). Thrissur: Kerala Sahitya Akademi.

Hapwood, Isabel F. 2008. trans. Les Miserables. By Victor Hugo.

1862. 5 Vols. New York:Thomas Y Cromwell & Co., 1887. Project

Gutenberg. June 22, 2008. 18 August, 2012. http://www.gutenberg.

org/files/135/135-h/135-h.htm.

Krishnappillai, Kuttippuzha. 2000. “Paavangal.” Kuttippuzhayude

122 Translation Today

K.M. Sherrif

Prabandhangai’(Essays by Kuttippuzha). 1990. Rpt. Thrissur: Kerala

Sahitya Akademi. pp. 67-84.

Lefevere, Andre. 1988. “Beyond Interpretation or the Business of

(Re)writing.” Essays in Comparative Literature. Calcutta: Papyrus.

Macura, Vladimir. 1990. “Culture as Translation.” In Trnslation,

History, Culture. Ed. Susan Bassnett and Andre Lefevere. London:

Routledge. PP. 64-70.

Marar, Kuttikrishna. 1985. Malayalashaili (Malayalam Usage). 1942.

Rpt. Kozhikode: Mathrubhumi Books.

Menon, Nalappattu Narayana. trans. Paavangal (Les Miserables ).By

Victor Hugo. 3 Vols. Thrissur: Yogakshemam, 1925-’28.

Parameswaran Pillai, Pulimana. 1966. Samatvavadi (The Socialist).

1940. Rpt. Thrissur: G Sankara Pillai Memorial for Theatre Studies.

Thomas, C J. 1982. Ayiraihi Orunootti Irupathettil Crime Irupathezhu

(Crime Number Twenty Seven of One Thousand One Hundred and

Twenty Eight). 1954. Kottayam: DC Books.

Venuti, Lawrence. 1995. The Scandals of Translation. London:

Routledge.

(Paper presented in the seminar, “Growth of Malayalam Language

and the Role of Knowledge Text Translation” on January 29, 2011.)

Translation Today 123

You might also like

- Cultural and Ideological TurnsDocument3 pagesCultural and Ideological TurnsJovanaSimijonović50% (2)

- UNIT 1. An Introduction To Translation Theory (Tema A Tema)Document6 pagesUNIT 1. An Introduction To Translation Theory (Tema A Tema)LorenaNo ratings yet

- ПерекладознавствоDocument128 pagesПерекладознавствоNataliia DerzhyloNo ratings yet

- Translation in African Contexts: Postcolonial Texts, Queer Sexuality, and Cosmopolitan FluencyFrom EverandTranslation in African Contexts: Postcolonial Texts, Queer Sexuality, and Cosmopolitan FluencyNo ratings yet

- Luise Von Flotow 2010 - Gender in TranslationDocument7 pagesLuise Von Flotow 2010 - Gender in TranslationMaria Gabriela PatricioNo ratings yet

- Essentially Translatable Poetry The Case of Lorca S Poet in New YorkDocument13 pagesEssentially Translatable Poetry The Case of Lorca S Poet in New YorkfrankNo ratings yet

- Turkish TranslatiosDocument18 pagesTurkish TranslatiossolNo ratings yet

- Historical Aspects of TranslationDocument6 pagesHistorical Aspects of TranslationGabriel Dan BărbulețNo ratings yet

- Theory of TranslationDocument36 pagesTheory of TranslationLalit Mishra50% (2)

- Theories of Translation: An Anthology of Essays from Dryden to DerridaFrom EverandTheories of Translation: An Anthology of Essays from Dryden to DerridaRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (13)

- Russian Translations of Thomas Grey's Elegy Written in A Country Church-Yard in 18th-19th CenturiesDocument8 pagesRussian Translations of Thomas Grey's Elegy Written in A Country Church-Yard in 18th-19th CenturiesnavquaNo ratings yet

- Translation Theory - Demands 2022Document45 pagesTranslation Theory - Demands 2022Nataliia DerzhyloNo ratings yet

- A Review of The History of Translation Studies PDFDocument10 pagesA Review of The History of Translation Studies PDFMohammed Mohammed Shoukry NaiemNo ratings yet

- Etymology of TranslationDocument2 pagesEtymology of TranslationCindy BuhianNo ratings yet

- Munday Chapter 7 Systems TheoriesDocument22 pagesMunday Chapter 7 Systems TheoriesFedorchuk AnnaNo ratings yet

- Writing Women in Korea Translation and Feminism in The Early Twentieth Century (Theresa Hyun) (Z-Library)Document192 pagesWriting Women in Korea Translation and Feminism in The Early Twentieth Century (Theresa Hyun) (Z-Library)AlexandraNo ratings yet

- Casanova - Translation As Unequal ExchangeDocument19 pagesCasanova - Translation As Unequal ExchangeFrancisco Rangel100% (1)

- Translation Studies IntroductionDocument30 pagesTranslation Studies IntroductionClarissa PacatangNo ratings yet

- Week 5Document35 pagesWeek 5detektifconnyNo ratings yet

- Рибовалова Periods of the translation theory developmentDocument25 pagesРибовалова Periods of the translation theory developmentValya ChzhaoNo ratings yet

- TranslationDocument2 pagesTranslationSirKeds M GutierrezNo ratings yet

- Resumen Traducción Resumen TraducciónDocument18 pagesResumen Traducción Resumen TraducciónHildaNo ratings yet

- Tong King Lee Discoursing Translation in Modern China On Lu Xun's Dual Registers 2013 PDFDocument18 pagesTong King Lee Discoursing Translation in Modern China On Lu Xun's Dual Registers 2013 PDFAidaNo ratings yet

- Shamma-Translation and ColonialismDocument17 pagesShamma-Translation and ColonialismAndrés RamosNo ratings yet

- Session 2Document5 pagesSession 2Rayan SpardaNo ratings yet

- History of Translation TheoryDocument26 pagesHistory of Translation Theoryعبد الرحيم فاطميNo ratings yet

- Kwaku A. Gyasi, The African Writer As TranslatorDocument17 pagesKwaku A. Gyasi, The African Writer As TranslatorGhe CriNo ratings yet

- Sambasivan S OthelloDocument1 pageSambasivan S OthelloSherrif Kakkuzhi-MaliakkalNo ratings yet

- Translation and Style A Brief Introduction (Jean Boase-Beier)Document4 pagesTranslation and Style A Brief Introduction (Jean Boase-Beier)zardhshNo ratings yet

- In 1990 The Two Theoretical Bassnett and Lefevere Suggested A Breakthrough in The Field of Translation StudiesDocument11 pagesIn 1990 The Two Theoretical Bassnett and Lefevere Suggested A Breakthrough in The Field of Translation StudiesElvira GiannettiNo ratings yet

- A Short History of Malayalam LittDocument44 pagesA Short History of Malayalam LittSona Sebastian100% (1)

- English Literature Cha 2Document18 pagesEnglish Literature Cha 2Tesfu HettoNo ratings yet

- Comparative PostcolonialismsDocument131 pagesComparative Postcolonialismssahmadouk7715No ratings yet

- 18.the Most Prominent Ukrainian Translators of The 19th - 21st Centuries and Their Major TranslationsDocument15 pages18.the Most Prominent Ukrainian Translators of The 19th - 21st Centuries and Their Major TranslationsЮлия БухтаNo ratings yet

- A Short History of Translation Through The AgesDocument9 pagesA Short History of Translation Through The AgesJavaid Haxat100% (1)

- Translation and Translation StudiesDocument8 pagesTranslation and Translation Studiesrony7sar100% (2)

- LefevereDocument19 pagesLefeverePaulo AndradeNo ratings yet

- Monograph in Eng. 508Document9 pagesMonograph in Eng. 508Paolo NapalNo ratings yet

- Susan Bassnett Pages 12 To 44Document21 pagesSusan Bassnett Pages 12 To 44atiyeh irNo ratings yet

- Texto 10 Snell-Hornby - Venuti S ForeignizationDocument4 pagesTexto 10 Snell-Hornby - Venuti S ForeignizationJavier Ulloa AlcántarNo ratings yet

- ActivityDocument2 pagesActivity「 」No ratings yet

- The Man Between: Michael Henry Heim and a Life in TranslationFrom EverandThe Man Between: Michael Henry Heim and a Life in TranslationNo ratings yet

- 05 Said Faiq, Cultural Dislocation Through TranslationDocument20 pages05 Said Faiq, Cultural Dislocation Through TranslationsalteneijiNo ratings yet

- Literary TranslationDocument11 pagesLiterary TranslationLysa Bueza TurredaNo ratings yet

- Stylistics and Rhetoric - 074450Document10 pagesStylistics and Rhetoric - 074450Glezyl DestrizaNo ratings yet

- 200 Reviews: Vulgar Latin. Trans. Roger Wright. University Park, Pa.: PennsylvaniaDocument2 pages200 Reviews: Vulgar Latin. Trans. Roger Wright. University Park, Pa.: PennsylvaniaZhe LouNo ratings yet

- 12 Marcinkiewicz Vol1 2017Document20 pages12 Marcinkiewicz Vol1 2017Karolina JeżewskaNo ratings yet

- Reviewer in COGNATE 2Document9 pagesReviewer in COGNATE 2ROSANANo ratings yet

- Translation StudiesDocument11 pagesTranslation Studiessteraiz0% (1)

- A Corpus Based Comparative Study On GeorDocument8 pagesA Corpus Based Comparative Study On Georsara algorianyNo ratings yet

- Conchitina R. Cruz - Recombinant Poetics, The Radical Autonomy of Jose F. Lacaba's Poems in English (Diss.)Document46 pagesConchitina R. Cruz - Recombinant Poetics, The Radical Autonomy of Jose F. Lacaba's Poems in English (Diss.)hmxyaNo ratings yet

- Literary Translation in Ukraine Prior To Soviet RuleDocument5 pagesLiterary Translation in Ukraine Prior To Soviet RuleZahara XavierNo ratings yet

- Heilbron PDFDocument13 pagesHeilbron PDFAilu GeraghtyNo ratings yet

- Main Issues of Translation StudiesDocument4 pagesMain Issues of Translation Studiesmarine29vinnNo ratings yet

- Look Back in Anger AnalysisDocument67 pagesLook Back in Anger AnalysisReshma janeNo ratings yet

- Power Unit & TransmissionDocument3 pagesPower Unit & TransmissionJijo GeorgeNo ratings yet

- Report Aebs enDocument117 pagesReport Aebs enbadboys123No ratings yet

- A Review of Automobile Waste Heat Recovery System: Prof. Murtaza Dholkawala, Mr. Ahire Durgesh VijayDocument7 pagesA Review of Automobile Waste Heat Recovery System: Prof. Murtaza Dholkawala, Mr. Ahire Durgesh VijayJijo GeorgeNo ratings yet

- Basics of Computational Combustion Modeling PDFDocument30 pagesBasics of Computational Combustion Modeling PDFEvelin KochNo ratings yet

- Advantages of Electronic Fuel Injection SystemDocument4 pagesAdvantages of Electronic Fuel Injection SystemJijo GeorgeNo ratings yet

- List of Irregular Verbs: Base Form - Past Simple - Past ParticipleDocument2 pagesList of Irregular Verbs: Base Form - Past Simple - Past ParticipleDaniel MagcalasNo ratings yet

- Coures Code: Coures Name: Automobile Subject Code:Mc21-23 Subject:Fluid Mechanics Exam Session 2020 Semester: 5ThDocument3 pagesCoures Code: Coures Name: Automobile Subject Code:Mc21-23 Subject:Fluid Mechanics Exam Session 2020 Semester: 5ThJijo GeorgeNo ratings yet

- Power Unit & TransmissionDocument3 pagesPower Unit & TransmissionJijo GeorgeNo ratings yet

- English IiiDocument4 pagesEnglish IiiJijo GeorgeNo ratings yet

- Course Code: Course Name:AUTOMOBILE Subject Code: MC21-25 Subject:Automotive ChassisDocument1 pageCourse Code: Course Name:AUTOMOBILE Subject Code: MC21-25 Subject:Automotive ChassisJijo GeorgeNo ratings yet

- Automotive Petrol & Diesel EngineDocument3 pagesAutomotive Petrol & Diesel EngineJijo GeorgeNo ratings yet

- Report Write UpDocument10 pagesReport Write UpAnis AltafNo ratings yet

- (Project Title) : Rizvi College of EngineeringDocument18 pages(Project Title) : Rizvi College of EngineeringJijo GeorgeNo ratings yet

- Automobile Industry in IndiaDocument13 pagesAutomobile Industry in Indiaramniwas sharma0% (1)

- (Project Title) : Rizvi College of EngineeringDocument18 pages(Project Title) : Rizvi College of EngineeringJijo GeorgeNo ratings yet

- (Project Title) : Rizvi College of EngineeringDocument18 pages(Project Title) : Rizvi College of EngineeringJijo GeorgeNo ratings yet

- Introducing VyangyaVyakhyaDocument3 pagesIntroducing VyangyaVyakhyasingingdrumNo ratings yet

- Rural Libraries of KeralaDocument56 pagesRural Libraries of Keralaarjun_nbrNo ratings yet

- Unit 25 PDFDocument15 pagesUnit 25 PDFVinaya BhaskaranNo ratings yet

- Sa Dicts ListDocument11 pagesSa Dicts ListRahul BalakrishanNo ratings yet

- Volume 3, Number 1, January 2015 (IJCLTS)Document73 pagesVolume 3, Number 1, January 2015 (IJCLTS)Md Intaj AliNo ratings yet

- Tulu English DictionaryDocument704 pagesTulu English Dictionaryuskeerthan614575% (4)

- SUbject Codes SSCDocument36 pagesSUbject Codes SSCAbhijit TodkarNo ratings yet

- Sreenath, V. S. 'What To Do With The Past-Sanskrit Literary Criticism in Postcolonial Space'Document16 pagesSreenath, V. S. 'What To Do With The Past-Sanskrit Literary Criticism in Postcolonial Space'Arjuna S RNo ratings yet

- Study On Malayalam ScriptDocument68 pagesStudy On Malayalam Scriptvrkots0% (1)

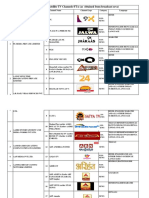

- Breakup of Circulation Figures - Town Wise - District WiseDocument2,147 pagesBreakup of Circulation Figures - Town Wise - District Wiselokmatgroup366033% (3)

- History of MalayalamDocument19 pagesHistory of MalayalamAjeesh C PhilipNo ratings yet

- Malayalam LiteratureDocument64 pagesMalayalam LiteratureShaher AlburaihyNo ratings yet

- AnnamalaiDocument32 pagesAnnamalaiksksasikumarNo ratings yet

- Tamil A Biography - David ShulmanDocument417 pagesTamil A Biography - David ShulmanJeyaraj JSNo ratings yet

- 160 EngDocument3 pages160 EngNithin SurendranNo ratings yet

- Agathiya Spoken Hindi Through Tamil PDF Ebook Down PDFDocument2 pagesAgathiya Spoken Hindi Through Tamil PDF Ebook Down PDFsundarNo ratings yet

- JayaprakashDocument4 pagesJayaprakashRaja RamNo ratings yet

- English To Malayalam Translation A Statistical ApproachDocument7 pagesEnglish To Malayalam Translation A Statistical ApproachsreenathpnrNo ratings yet

- Malayalam Theatre by Krishnapriya SDocument34 pagesMalayalam Theatre by Krishnapriya SKrishnapriya SudarsanNo ratings yet

- List of NairsDocument16 pagesList of NairssheghiljobsNo ratings yet

- Karunatillake & Susseendirajah Pronouns of Address in Tamil and Sinhalese - A Sociolinguistic StudyDocument9 pagesKarunatillake & Susseendirajah Pronouns of Address in Tamil and Sinhalese - A Sociolinguistic StudyJack SidnellNo ratings yet

- University of Madras: Date & Session Subject Subject Code First Semester (Full Time / Part Time)Document62 pagesUniversity of Madras: Date & Session Subject Subject Code First Semester (Full Time / Part Time)Mohan SubramanianNo ratings yet

- Guruvayur Temple Arch PDFDocument46 pagesGuruvayur Temple Arch PDFBasava prabhu prabhu100% (1)

- 17 Annamalai University Degree ExaminationsDocument18 pages17 Annamalai University Degree ExaminationslooserNo ratings yet

- Tamil A Biography (PDFDrive)Document392 pagesTamil A Biography (PDFDrive)Sky TwainNo ratings yet

- Permitted Private Satellite TV Channels-FTA (As Obtained From Broadcast Seva)Document64 pagesPermitted Private Satellite TV Channels-FTA (As Obtained From Broadcast Seva)Aashish JainNo ratings yet

- A History 80 Yrs of Mallu MoviesDocument7 pagesA History 80 Yrs of Mallu MoviesSudha KfNo ratings yet

- Learn Malayalam in 30 DaysDocument164 pagesLearn Malayalam in 30 DaysShweta Amma63% (30)

- PSC 2018 July 15-MinDocument24 pagesPSC 2018 July 15-MinShibin LatheefNo ratings yet

- 12 ReferencesDocument6 pages12 ReferencesAbhilash MalayilNo ratings yet