Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Curriculum Mapping Aligns Learning

Uploaded by

Qhutie Little CatOriginal Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Curriculum Mapping Aligns Learning

Uploaded by

Qhutie Little CatCopyright:

Available Formats

https://www.edglossary.

org/alignment/

Curriculum mapping is the process indexing or diagraming a curriculum to identify and

address academic gaps, redundancies, and misalignments for purposes of improving the overall

coherence of a course of study and, by extension, its effectiveness (a curriculum, in the sense

that the term is typically used by educators, encompasses everything that teachers teach to

students in a school or course, including the instructional materials and techniques they use).

In most cases, curriculum mapping refers to the alignment of learning standards and teaching

—i.e., how well and to what extent a school or teacher has matched the content that students

are actually taught with the academic expectations described in learning standards—but it may

also refer to the mapping and alignment of all the many elements that are entailed in educating

students, including assessments, textbooks, assignments, lessons, and instructional

techniques.

The term alignment is widely used by educators in a variety of contexts, most commonly

in reference to reforms that are intended to bring greater coherence or efficiency to

a curriculum, program, initiative, or education system.

When the term is used in educational contexts without qualification, specific examples,

or additional explanation, it may be difficult to determine precisely what alignment is

referring to. In some cases, the term may have a very specific, technical meaning, but in

others it may be vague, undecipherable jargon. Generally speaking, the use of

alignment tends to become less precise and meaningful when its object grows in size,

scope, or ambition. For example, when teachers talk about “aligning curriculum,” they

are likely referring to a specific, technical process being used to develop lessons,

deliver instruction, and evaluate student learning growth and achievement. On the other

hand, some education reports, improvement plans, and policy proposals may refer to

the “alignment” of various elements of an education system without describing precisely

what might be entailed in the proposed alignment process. And, of course, some

“alignments” may be practical, thoughtful strategies that produce tangible improvements

in schools and student learning, while others may be unspecific “action items” that never

get acted on, or they may be strategies that show promise in theory, but that turn out to

be overly complex and burdensome when executed in states, districts, and schools.

The following are a few representative examples of how the term is used in reference to

education reforms:

Policy: Educators, reformers, policy makers, and elected officials may call for the

“alignment of policy and practice.” For example, federal or state laws, regulations,

and rules may not be enacted in districts or schools, or educators may not follow

policies established by school boards and districts. Or enacted laws and regulations

may contradict one another, leaving school leaders and teachers wondering which

laws and rules they should follow. In addition, the interpretation and implementation

of a given education policy in schools may diverge significantly from the guidance

and objectives of a policy, which may then require modifications to—or the

alignment of—the policy language and resulting “practices” used by

educators. Generally speaking, the alignment of policy usually entails a process of

refinement, iteration, clarification, and communication during the development, and

following the adoption, of a new policy or set of policies.

Strategy: School leaders may work to “align” the organization and operation of a

district or school, including how students are taught, with a given school-

improvement plan, reform strategy, or educational model. In this case, the alignment

process might entail a wide variety of reforms—from reallocating budgetary

expenditures to restructuring school schedules to redesigning courses and lessons—

in ways that are intended to achieve the objectives of the improvement plan, while

also ensuring that its parts are working together coherently and effectively. For a

related discussion, see action plan.

Learning Standards: Educators may work to “align” what and how they teach with

a given set of learning standards, such as the Common Core State Standards or the

subject-area standards developed by states and national organizations. In this case,

modifications may be made to lessons, course designs, academic programs, and

instructional techniques so that the concepts and skills described in the standards are

taught to students at certain times, in certain sequences, or in certain ways. For

related discussions, see learning progression and proficiency-based learning.

Assessment: Teachers may “align” assessments, standards, lessons, and instruction

so that the assessments evaluate the material they are teaching in a unit or

course. Test-development companies also “align” standardized tests to a state’s

learning standards so that test questions and tasks address the specific concepts and

skills described in the standards for a certain subject area and grade level. In

individual cases, teachers may align assessments and lessons more or less precisely,

but developers of large-scale standardized tests utilize sophisticated psychometric

strategies intended to improve the validity and accuracy of the assessment results

(although this is a source of ongoing debate). For a related discussion,

see measurement error.

Curriculum: Educators may “align” curriculum in different ways, but perhaps the

most common forms are (1) aligning curriculum—the knowledge, skills, topics, and

concepts that are taught to students, and the lessons, units, assignments, readings,

and materials used in the teaching process—with specific learning standards, and (2)

aligning various curricula within a school, such as the curriculum for a particular

course, with other curricula in the school to improve overall coherence and

effectiveness. In the second case, for example, educators may align curricula by

making sure that courses follow a logical learning sequence, within and across

subject areas and grade levels, so that new concepts build on previously taught

concepts. For a more detailed discussion, see coherent curriculum.

Professional Development: School leaders, educational experts, reform

organizations, and government agencies may “align” professional development—

such as training sessions, workshops, conferences, and resources—with the

objectives of specific policies, improvement plans, or educational models. For

example, state education agencies may provide training sessions for superintendents

and principals to help them implement new teacher-evaluation requirements, or

districts and schools may contract with experts and outside organizations to help

their faculties learn new educational approaches or teaching techniques.

Horizontal coherence: When a curriculum is horizontally aligned or horizontally

coherent, what students are learning in one ninth-grade biology course, for example,

mirrors what other students are learning in a different ninth-grade biology

course. Curriculum mapping aims to ensure that the assessments, tests, and other methods

teachers use to evaluate learning achievement and progress are based on what has

actually been taught to students and on the learning standards that the students are

expected to meet in a particular course, subject area, or grade level.

Subject-area coherence: When a curriculum is coherent within a subject area—such as

mathematics, science, or history—it may be aligned both within and across grade

levels. Curriculum mapping for subject-area coherence aims to ensure that teachers are

working toward the same learning standards in similar courses (say, three different ninth-

grade algebra courses taught by different teachers), and that students are also learning the

same amount of content, and receiving the same quality of instruction, across subject-area

courses.

Interdisciplinary coherence: When a curriculum is coherent across multiple subject

areas—such as mathematics, science, and history—it may be aligned both within and

across grade levels. Curriculum mapping for interdisciplinary coherence may focus on

skills and work habits that students need to succeed in any academic course or discipline,

such as reading skills, writing skills, technology skills, and critical-thinking

skills. Improving interdisciplinary coherence across a curriculum, for example, might

entail teaching students reading and writing skills in all academic courses, not just

English courses.

You might also like

- Minutes of Faculty Showing Announcement of DepEd OrdersDocument1 pageMinutes of Faculty Showing Announcement of DepEd OrdersEdrian Peter VillanuevaNo ratings yet

- Cb-Past Form 1Document6 pagesCb-Past Form 1Virgilio BoadoNo ratings yet

- Vertical Learning Progression in MathDocument3 pagesVertical Learning Progression in MathReyboy TagsipNo ratings yet

- Administrators ProfileDocument2 pagesAdministrators ProfileCharley Vill Credo100% (1)

- Classroom Orientation ProgramDocument3 pagesClassroom Orientation Programjomar famaNo ratings yet

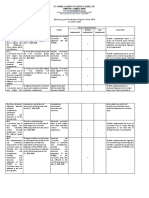

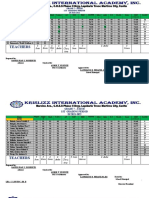

- System Learning Plan Preparation: Krislizz International AcademyDocument11 pagesSystem Learning Plan Preparation: Krislizz International AcademyQhutie Little CatNo ratings yet

- Ssip School: Maryknoll School of Lupon, Inc. Region: 11 AREA: Physical Plant and Instructional Support Facilities and Resource ManagementDocument7 pagesSsip School: Maryknoll School of Lupon, Inc. Region: 11 AREA: Physical Plant and Instructional Support Facilities and Resource ManagementRexelle NavalesNo ratings yet

- Monitoring-and-Evaluation-Report-of-the-SSIP AREA BDocument5 pagesMonitoring-and-Evaluation-Report-of-the-SSIP AREA Bmira rochenieNo ratings yet

- PLC Goals and ObjectivesDocument2 pagesPLC Goals and ObjectivesIzzati AzmanNo ratings yet

- System for Updating Curriculum ProceduresDocument8 pagesSystem for Updating Curriculum ProceduresAngelica Wenceslao100% (1)

- Instructional LeadershipDocument3 pagesInstructional LeadershipAlfonso AmpongNo ratings yet

- ADMINISTRATORS DEVELOPMENT PLANDocument2 pagesADMINISTRATORS DEVELOPMENT PLANLJ Ruiz100% (1)

- PLC Meeting Minutes-2-6-19Document2 pagesPLC Meeting Minutes-2-6-19api-316781445No ratings yet

- Curriculum Map: St. Andrew Christian AcademyDocument3 pagesCurriculum Map: St. Andrew Christian AcademyRoby PadillaNo ratings yet

- Curriculum Development ActivitiesDocument3 pagesCurriculum Development ActivitiesMaria Josefina Acaso AguilarNo ratings yet

- Circles Unit Assessment MapDocument3 pagesCircles Unit Assessment MapYuri IssangNo ratings yet

- UNIT ASSESSMENt 8Document8 pagesUNIT ASSESSMENt 8Junafel Boiser GarciaNo ratings yet

- School-Based Management (SBM) Validated PracticeDocument32 pagesSchool-Based Management (SBM) Validated PracticeArnold A. BaladjayNo ratings yet

- Improvement Plan Item Vertical Learning ProgressionDocument2 pagesImprovement Plan Item Vertical Learning ProgressionRosalyn Mauricio100% (3)

- Peac Certification Peac Official WebsiteDocument60 pagesPeac Certification Peac Official WebsiteMMC BSEDNo ratings yet

- Curriculum Development ActivitiesDocument6 pagesCurriculum Development ActivitiesAgustin P. Baquereza Jr.No ratings yet

- St. Peter's College PEAC RecertificationDocument3 pagesSt. Peter's College PEAC RecertificationGelliane UbaganNo ratings yet

- Recommendations: Private Education Assistance CommitteeDocument15 pagesRecommendations: Private Education Assistance Committeeelvie sabang100% (1)

- Curriculum DevelopmentDocument9 pagesCurriculum DevelopmentChristopher R. Bañez IINo ratings yet

- SSIP G June 2022Document6 pagesSSIP G June 2022Rudy AquinoNo ratings yet

- Handbook on Academic Support System for D.El.Ed ProgrammeDocument66 pagesHandbook on Academic Support System for D.El.Ed ProgrammePrem Sharma100% (3)

- Mmsci - Ssip 2018-2019 - 2022-2023Document32 pagesMmsci - Ssip 2018-2019 - 2022-2023Francis23 De Castro100% (1)

- Vertical Learning Progression MathematicsDocument2 pagesVertical Learning Progression MathematicsEdrian Peter Villanueva100% (3)

- Informal Observation FormDocument1 pageInformal Observation FormCarlo L. TongolNo ratings yet

- PPT Esc Orientation Grade 7 2018 2019Document19 pagesPPT Esc Orientation Grade 7 2018 2019Sfa Mabini BatangasNo ratings yet

- Evaluation For Non PrintDocument10 pagesEvaluation For Non PrintShaira Grace Calderon100% (1)

- S1 - Handout5 - Peac Cai For Curr, Assmt & InstDocument7 pagesS1 - Handout5 - Peac Cai For Curr, Assmt & InstAilyn SorillaNo ratings yet

- Math 7 Subject Vertical Learning Progression MapDocument6 pagesMath 7 Subject Vertical Learning Progression MapReyboy Tagsip100% (1)

- Standard-Based School Improvement Plan HDocument3 pagesStandard-Based School Improvement Plan HLhyn ThonNo ratings yet

- Alternative Delivery Mode Learning Resource StandardsDocument38 pagesAlternative Delivery Mode Learning Resource StandardsCons Agbon Monreal Jr.No ratings yet

- PEAC Classroom Observation FormDocument1 pagePEAC Classroom Observation FormSteven Andrei LorenNo ratings yet

- Instructional Supervision ReportsDocument5 pagesInstructional Supervision ReportsJunafel Boiser GarciaNo ratings yet

- Monitoring and Evaluation of AOPDocument2 pagesMonitoring and Evaluation of AOPLearn with Joy PH100% (1)

- Pas Form B-2 Performance Appraisal System For Teachers Past Name ...Document5 pagesPas Form B-2 Performance Appraisal System For Teachers Past Name ...Kaye Tan Garcia67% (3)

- FACULTY ROSTER TemplateDocument5 pagesFACULTY ROSTER TemplateJohn Raygie Ordoñez Cineta100% (1)

- Peac-Cert Program (Peac - Certification Readiness Training) Day 1Document2 pagesPeac-Cert Program (Peac - Certification Readiness Training) Day 1Johnesa Mejias GonzalosNo ratings yet

- System in Selecting and Establishing With SchoolDocument5 pagesSystem in Selecting and Establishing With SchoolCipriano Bayotlang100% (3)

- Awards For TeachersDocument3 pagesAwards For TeachersClaudio MacahilosNo ratings yet

- PeacDocument2 pagesPeacRona Jane Roa Sanchez100% (2)

- Https Admissions - Jnu.ac - in Jnuee Offer Letter MADocument2 pagesHttps Admissions - Jnu.ac - in Jnuee Offer Letter MAJijin UBNo ratings yet

- Description of Curriculum Development Activities PDFDocument3 pagesDescription of Curriculum Development Activities PDFAngelica Wenceslao100% (6)

- Vertical Learning Progression Map Across Grade LevelsDocument3 pagesVertical Learning Progression Map Across Grade LevelsKatherine Pagas Galupo100% (1)

- Mathematics V Achievement Test (MAT) AppendixDocument18 pagesMathematics V Achievement Test (MAT) AppendixRustico Y Jerusalem0% (1)

- Summary of Requirements For PeacDocument15 pagesSummary of Requirements For PeacRhieza Perez UmandalNo ratings yet

- School Professional Development Plan TemplateDocument5 pagesSchool Professional Development Plan TemplateAngelo Garret V. LaherNo ratings yet

- Peac Curriculum, Assessment and Instruction: DescriptionDocument3 pagesPeac Curriculum, Assessment and Instruction: DescriptionJansen BaculiNo ratings yet

- SSIP Annual Operationa PlanDocument20 pagesSSIP Annual Operationa PlanHasnia S. DatukanNo ratings yet

- School improvement plan goalsDocument27 pagesSchool improvement plan goalskhaire jacobNo ratings yet

- Sample 3-Year Ssip Dev PlanDocument4 pagesSample 3-Year Ssip Dev PlanArnel BoholstNo ratings yet

- St. Francis Xavier Coaching and Mentoring ProgramDocument2 pagesSt. Francis Xavier Coaching and Mentoring ProgramAnicadlien Ellipaw IninNo ratings yet

- School Discipline Policy and ProcedureDocument5 pagesSchool Discipline Policy and ProcedureCatherine BautistNo ratings yet

- Saint Martin Academy develops standards-based improvement planDocument3 pagesSaint Martin Academy develops standards-based improvement planNikka Irah CamaristaNo ratings yet

- CURRICULUMDocument2 pagesCURRICULUMFaiqa AtiqueNo ratings yet

- CurriculumDocument3 pagesCurriculumMelody AnggolNo ratings yet

- CurriculumDocument6 pagesCurriculummarlokynNo ratings yet

- Shelby County Schools Science Vision: Tennessee Science Standards ReferenceDocument27 pagesShelby County Schools Science Vision: Tennessee Science Standards ReferenceQhutie Little CatNo ratings yet

- S2 - Apadv - Handout 2.3 - Template of Real Table For Power and Supporting CompetenciesDocument1 pageS2 - Apadv - Handout 2.3 - Template of Real Table For Power and Supporting CompetenciesQhutie Little CatNo ratings yet

- HO1 S1 2021 Program 2021 INSET For JHS TeachersDocument5 pagesHO1 S1 2021 Program 2021 INSET For JHS TeachersGynxi NekoNo ratings yet

- S2 - APADV - Handout 2.4 - TABLE OF CLUSTERING AND BUDGET OF TIME FOR POWER AND SUPPORTING COMPETENCIEDocument1 pageS2 - APADV - Handout 2.4 - TABLE OF CLUSTERING AND BUDGET OF TIME FOR POWER AND SUPPORTING COMPETENCIEQhutie Little CatNo ratings yet

- Empowering Educators Through InnovationDocument11 pagesEmpowering Educators Through InnovationQhutie Little CatNo ratings yet

- Work Experience Sheet for Supervising PositionsDocument2 pagesWork Experience Sheet for Supervising PositionsCes Camello100% (1)

- Grade 7 Faith 1ST Grading 2021 2022Document7 pagesGrade 7 Faith 1ST Grading 2021 2022Qhutie Little CatNo ratings yet

- 8 Secrets of The Truly Rich-Bo SanchezDocument213 pages8 Secrets of The Truly Rich-Bo Sanchezundefined_lilai100% (13)

- Criteria For Judging ElementaryDocument6 pagesCriteria For Judging ElementaryQhutie Little CatNo ratings yet

- Instructional Supervisory Plan For ED 22Document12 pagesInstructional Supervisory Plan For ED 22Qhutie Little CatNo ratings yet

- List of Acquisiiton 2020Document4 pagesList of Acquisiiton 2020Qhutie Little CatNo ratings yet

- The Development of Lesson Planning SysteDocument4 pagesThe Development of Lesson Planning SysteQhutie Little CatNo ratings yet

- Comprehensive Table of Specification Science Grade 7 1st QuarterDocument3 pagesComprehensive Table of Specification Science Grade 7 1st QuarterAnnie Bagalacsa Cepe-TeodoroNo ratings yet

- System Learning Plan Preparation: Krislizz International AcademyDocument11 pagesSystem Learning Plan Preparation: Krislizz International AcademyQhutie Little CatNo ratings yet

- ELED ELACurriculumMapforGrade8 0815 PDFDocument22 pagesELED ELACurriculumMapforGrade8 0815 PDFmarvin agubanNo ratings yet

- Ela Grades 6 8 Curriculum Plan PDFDocument2 pagesEla Grades 6 8 Curriculum Plan PDFrawanbai tariwasayNo ratings yet

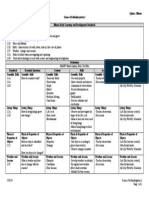

- Unit Plan and Assessment MapDocument4 pagesUnit Plan and Assessment MapQhutie Little CatNo ratings yet

- Reading and Writing Assessment: Grade 4-DaisyDocument6 pagesReading and Writing Assessment: Grade 4-DaisyQhutie Little CatNo ratings yet

- ELED ELACurriculumMapforGrade8 0815 PDFDocument22 pagesELED ELACurriculumMapforGrade8 0815 PDFmarvin agubanNo ratings yet

- Curriculum Map Science PreK 3Document1 pageCurriculum Map Science PreK 3Qhutie Little CatNo ratings yet

- Curriculum Map 2016Document7 pagesCurriculum Map 2016dyonaraNo ratings yet

- Ela Grades 6 8 Curriculum Plan PDFDocument2 pagesEla Grades 6 8 Curriculum Plan PDFrawanbai tariwasayNo ratings yet

- CVC Words FamilyDocument7 pagesCVC Words FamilyQhutie Little CatNo ratings yet

- Plan State College: Example Assessment BismarckDocument1 pagePlan State College: Example Assessment BismarckQhutie Little CatNo ratings yet

- What Is CommunicationDocument2 pagesWhat Is CommunicationQhutie Little CatNo ratings yet

- Rules in Online Learning Class KLIA Provides The Setting in Which Pupils/students Could Practice The Rules of CourtesyDocument2 pagesRules in Online Learning Class KLIA Provides The Setting in Which Pupils/students Could Practice The Rules of CourtesyQhutie Little CatNo ratings yet

- Cover Letter: Do Not Simply Copy This Sample Letter. Use Your Own Words and Writing StyleDocument1 pageCover Letter: Do Not Simply Copy This Sample Letter. Use Your Own Words and Writing StyleMónica Martin IranzoNo ratings yet

- B2 ISESOL Practice Paper 3Document7 pagesB2 ISESOL Practice Paper 3nota32No ratings yet

- Activity 5 Educational Philosophy Inventory: Revision Status: Revision Date: Recommending Approval: Concurred: ApprovedDocument2 pagesActivity 5 Educational Philosophy Inventory: Revision Status: Revision Date: Recommending Approval: Concurred: ApprovedErichIsnainNo ratings yet

- Curriculum Map: Subject: English Grade Level: 10 Teachers: Keith Miko G. Carpesano Strand (S)Document1 pageCurriculum Map: Subject: English Grade Level: 10 Teachers: Keith Miko G. Carpesano Strand (S)Keith Miko CarpesanoNo ratings yet

- Foundation of EducationDocument15 pagesFoundation of EducationGilbert Mores EsparragoNo ratings yet

- Fix Makalah English Teaching Kel5Document13 pagesFix Makalah English Teaching Kel5RahmaNiatyNo ratings yet

- IMDS Working Series Tapas MajumdarDocument144 pagesIMDS Working Series Tapas Majumdarpragya89No ratings yet

- Collaborative Assessment Log FinalDocument4 pagesCollaborative Assessment Log Finalapi-272657959No ratings yet

- Curriculum DesignDocument45 pagesCurriculum DesignAntonio Delgado100% (1)

- PornoDocument27 pagesPornoOscarNo ratings yet

- Sag RubricDocument1 pageSag Rubricapi-255055274No ratings yet

- Action Research BookletDocument20 pagesAction Research BookletSoft SkillsNo ratings yet

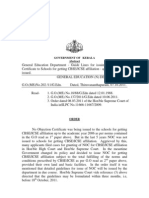

- Noccbseicse 11102011Document6 pagesNoccbseicse 11102011josh2life100% (1)

- Grading Consistency in Online vs F2F CoursesDocument3 pagesGrading Consistency in Online vs F2F CoursesNoranaCantrellNo ratings yet

- Oxford Handbook of Commercial Correspondence (New Edition) : December 2005 Volume 9, Number 3Document3 pagesOxford Handbook of Commercial Correspondence (New Edition) : December 2005 Volume 9, Number 3Huỳnh Hồng HiềnNo ratings yet

- Divergent Thinking Course OverviewDocument6 pagesDivergent Thinking Course OverviewVineet SudevNo ratings yet

- Magna Carta for Disabled Persons Act ExplainedDocument41 pagesMagna Carta for Disabled Persons Act ExplainedJoanne Ario Billones75% (4)

- Year 1 Civic Lesson Plan on Happiness and PatriotismDocument1 pageYear 1 Civic Lesson Plan on Happiness and Patriotismsaifulefpandi7761No ratings yet

- Form 1 English lesson on consumerism and money managementDocument1 pageForm 1 English lesson on consumerism and money managementMiera MijiNo ratings yet

- Montessori Move Case Study Montessori Pedagogical Instructional Principles Implications Community College Course Graduates Career PathsDocument109 pagesMontessori Move Case Study Montessori Pedagogical Instructional Principles Implications Community College Course Graduates Career Paths123_scNo ratings yet

- Gese Grade 3 Directions Local Area JobsDocument4 pagesGese Grade 3 Directions Local Area JobsIrina StratulatNo ratings yet

- CS Form No. 212 Attachment - Work Experience SheetDocument2 pagesCS Form No. 212 Attachment - Work Experience SheetOcehcap Arram100% (2)

- Cv-Yasmin IbrahimDocument2 pagesCv-Yasmin Ibrahimapi-316704749No ratings yet

- ChemistryNMRPupilWorkbookAnswersAH tcm4-723712Document18 pagesChemistryNMRPupilWorkbookAnswersAH tcm4-723712AmmarahBatool95100% (2)

- Grade 11 Math Diagnostic TestDocument3 pagesGrade 11 Math Diagnostic TestRalph75% (4)

- Multiplication Facts and StrategiesDocument22 pagesMultiplication Facts and StrategiesKutty Paiya100% (2)

- Meeting Minutes GuideDocument4 pagesMeeting Minutes GuideJosephine TabajondaNo ratings yet

- CEFR-aligned Curriculum FrameworkDocument29 pagesCEFR-aligned Curriculum Frameworkazeha100% (1)

- Strings MagazineDocument28 pagesStrings MagazineCatarina SilvaNo ratings yet

- CENG 331 Computer Organization Syllabus METUDocument2 pagesCENG 331 Computer Organization Syllabus METUAnonymous GuQd67No ratings yet