Professional Documents

Culture Documents

On The Writing of Philippnes History

Uploaded by

Jared TancoOriginal Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

On The Writing of Philippnes History

Uploaded by

Jared TancoCopyright:

Available Formats

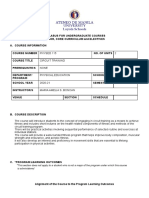

On The Writing Of Philippine History

Author(s): Nicolas Zafra

Source: Philippine Studies , NOVEMBER 1958, Vol. 6, No. 4 (NOVEMBER 1958), pp. 454-

460

Published by: Ateneo de Manila University

Stable URL: https://www.jstor.org/stable/42720410

JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide

range of content in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and

facilitate new forms of scholarship. For more information about JSTOR, please contact support@jstor.org.

Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of the Terms & Conditions of Use, available at

https://about.jstor.org/terms

Ateneo de Manila University is collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve and extend access

to Philippine Studies

This content downloaded from

52.74.166.170 on Tue, 23 Feb 2021 03:35:33 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

Notes and Comment

On The Writing Of Philippine History

THE article by Prof. Teodoro A. Agoncillo which appeared in

a local publication under the title "An Interpretation of Our His-

tory Under Spain"1 could not but arouse the interest and curiosity

of many people, for the matter dealt with, namely, the need for

an adequate and satisfying history of the Philippines, concerns the

public welfare. It is vitally important that such history should be

adequate in the sense that it should come up to universally recog-

nized standards of historical scholarship.

Prof. Agoncillo is of opinion that before 1872 the Filipinos had

no history of their own. What is regarded as Philippine history be-

fore that date is, according to him, not Philippine but Spanish.

In pursuance of this idea, Professor Agoncillo wrould exclude from

his proposed history the narration of events in which Filipinos

did not play what he calls "an active role in carving out their des-

tiny."

Many of Prof. Agoncillo's colleagues in the historical profes-

sion will not subscribe to his views. Certainly not to his concept

of how the relevance or irrelevance of historical facts should be

determined. His idea that only those events in which the Filipinos

played an "active role in carving out their destiny" are relevant

and, therefore, are the only ones to figure in the written history

of the Filipino people is, from the standpoint of historical scholar-

ship, wholly unacceptable. For it ignores or overlooks the fact

that the Filipinos during the Spanish period were subjects of

1 Sunday Times Magazine , 24 August 1958.

454

This content downloaded from

52.74.166.170 on Tue, 23 Feb 2021 03:35:33 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

NOTES AND COMMENT 455

Spain. As such, they could not have played a

of subjects of a colonial power. To present them in a different

role, as masters of their situation, or as being in a position to

"carve out their destiny," is to distort or falsify the truths of his-

tory.

It is well to remind ourselves that the prime duty and respon-

sibility of a historian is to present accurately and truthfully from

available sources what can be known about the past. "It is not

patriotism, nor religion, nor art, but the attainment of truth that

is and must be the historian's single aim."2

When Prof. Agoncillo tells us that prior to 1872 the Filipinos

had no history of their own, one wonders whether he intends to

be taken seriously or not. For his statement implies that there

are no sources of information whatsoever on the period prior to

1872. Such an assumption is of course entirely unfounded as any

one who knows something of Philippine historiography can tell.

Prof. Agoncillo in his article brought up the story about Fr.

Manuel Blanco to emphasize his point. The moral of the story,

according to him, is that the period before 1872 is a blank page

comparable or analogous to the blank pages in the manuscript

which Fr. Manuel Blanco is alleged to have intended to write on

the history of the Philippines. Parenthetically, one is tempted to

ask, How authentic is the story about Fr. Blanco? Is it true that

he seriously attempted to write on the history of the Philippines?

As his particular interest as a scholar was botany, not Philippine

history, one has good reason to doubt that he was serious about his

supposed intention to write a history of the Philippines. He must

have been aware of the fact that distinguished members of his

Order such as Juan de Gri jaiva, Gaspar de San Agustín, Juan de

Medina, Casimiro Diaz, and Martinez de Zúñiga, had left valuable

writings on the history of the Philippines. It was therefore un-

likely that he failed to see the absurdity of the idea that there

was absolutely nothing to write about. In any event, it would be

interesting to know the source and authenticity of the story.

Prof. Agoncillo seems somewhat confused in his use of the

word "history." When he speaks of the "texture and substance of

2 F. York Powell quoted in Langlois and Seignobos, Introduction

to the Study of History (New York, 1898) preface.

This content downloaded from

52.74.166.170 on Tue, 23 Feb 2021 03:35:33 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

456 PHILIPPINE STUDIES

our history," it is not certain whether h

sense of "written history" or "history as actuality." If he means

"written history" what he says is quite true for there are, indeed,

historical works which, in content and in point of view, are Span-

ish rather than Filipino. This is true particularly of works au-

thored by Spanish writers. If, however, he refers to the events

themselves, that is "history as actuality," then it is inexcusable

for him to launch forth the idea that the Filipinos had no history

of their own prior to 1872.

A case in point is the representation of the Philippines in the

Spanish Cortes. Philippine representation, according to him, was

neither "Philippine" nor "representation." The representatives were

Spaniards, not Filipinos, and they did not have the interests of the

Philippines at heart. "There is, therefore, neither rhyme nor rea-

son," Professor Agoncillo tells us, "in discussing the so-called Phil-

ippine representation in the Cortes, much less in making it a

chapter of our history."

While it is true that the delegates who represented the Phil-

ippines in the Cortes, were, by and large, not exactly what Pro-

fessor Agoncillo would call "Filipinos de cara y corazón," there

was, nevertheless, at least one who, although Spanish by blood,

had the interests of the Philippines at heart: Ventura de los Re-

yes, who represented the Philippines in the Cortes of 1810-1813.

As a delegate, Ventura de los Reyes worked for measures that he

believed would redound to the benefit of the Philippines. At one

time he proposed in the Cortes a special election law designed not

only to make the representation less burdensome financially for

the Philippines, but also to make representation truly representa-

tive of the Philippines. For this, if for no other reason, the re-

presentation of the Philippines in the Cortes deserves to be noted

in any account designed to present with a reasonable degree of

completeness the history of the Philippines.

But even admitting, for the sake of argument, that the repre-

sentation of the Philippines was neither "Philippine" nor "repre-

sentation," there are good reasons for giving that event a place

among the truly significant facts of Philippine history. For one

thing, the developments connected with that event had notable re-

percussions in the Philippines. In llocos they generated a chain

of reactions culminating in the llocos uprisings of 1814-1815. The

facts of the llocos episode have a significance of their own which

This content downloaded from

52.74.166.170 on Tue, 23 Feb 2021 03:35:33 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

NOTES AND COMMENT 457

is of no little interest to the student of Philippine nationalism.

The reaction of the people of llocos to the events of their time

reveals in some way the extent to which the people in llocos had,

by then, advanced in their concept of country.

Besides, Philippine representation in the Cortes was an ex-

perience the memory of which long lingered among the Filipinos.

It was cherished by the spokesmen of Philippine nationalism in the

latter part of the 19th century. Restoration to the Philippines of

the privilege of representation in the Cortes was, as we all know,

one of the reforms insistently demanded by the leaders of the Pro-

paganda Movement. Obviously, for a sound understanding of that

Movement as a fact of history, the historical background of Fil-

ipino interest in Philippine representation in the Spanish Cortes

should be told.

If Philippine history is to be written strictly in accordance

with Professor Agoncillo's principle of selection and presentation

of historical facts, the reader would be kept in the dark with regard

to facts having direct or indirect relation to the progress of the Fil-

ipino people in various fields of human endeavor. Acquaintance

with these facts is important for a sound understanding and ap-

preciation of events and conditions, not only of the last years of

Spanish rule, but also of the contemporary period in Philippine

history.

One phase of Philippine history which very likely would not

get in Prof. Agoncillo's proposed history the importance it deserves

is, the role which the Catholic Church played in the political, social

and cultural advancement of the Filipino people. In his article,

he claimed that Catholicism was among the things that the Fil-

ipinos received from Spain for which they "bartered" (to use his

own words) "their freedom, wealth and dignity." He will, there-

fore, not bother about giving his readers an idea of the influence

of Catholicism in the building up of the Filipino people into a

nation. Keen students of history, however, duly understand and

recognize the historical significance of Catholicism in the Philip-

pines. They consider as indisputable the fact that Catholicism gave

to the Filipino pattern of culture its distinctive character. The

distinguished British scholar John Crawford, for one, subscribed

to this view. In a work he wrote in 1820, Crawford declared that

Catholicism raised the moral and intellectual stature of the Fil-

This content downloaded from

52.74.166.170 on Tue, 23 Feb 2021 03:35:33 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

458 PHILIPPINE STUDIES

ipinos.3 "The Filipinos who are Christians," he wrote, "possess

a share of energy and intelligence, not only superior to their pagan

and Mohammedan brothers of the same islands, but also to all the

western inhabitants of the Archipelago, to the very peoples who in

other periods of their history, bestowed laws, language and civil-

ization upon them." Another eminent British scholar, the well

known contemporary historian, Arnold J. Toynbee, upholds sub-

stantially the same view. In an article which recently appeared

in a London newspaper, Toynbee declared as his considered judg-

ment that Catholicism gave to the Filipinos an outlook and a spirit

which distinguished them from their neighbors in South East

Asia.4

Professor Agoncillo is of course entirely at liberty to present

the facts of Philippine history in the way he thinks they should

be presented. But, if he is to write an adequate and satisfying

history of the Philippines as he is planning to do, he is expected

to deal with historical problems in the manner and spirit of a true

and genuine scholar, fully aware of the requirements and standards

of historical scholarship and disposed to live up to them. In other

words, his proposed history should give clear indications of accu-

racy, objectivity, fullness of observation, and, above all, correctness

of reasoning.

Incidentally, it may here be stated that the writing of a scho-

larly history of the Philippines is long overdue. In 1908, at the

request of Felipe Calderón (the author of the Malolos Constitution)

Wenceslao Retana prepared a plan for such a history. The plan

called for a thirteen-volume history of the Philippines, each vol-

ume to consist of from 400 to 500 pages. The work was to be

undertaken, on the basis of available sources, primary and second-

ary, by Filipino scholars themselves. The project had the enthu-

siastic endorsement and approval of prominent scholars at the time

such as Calderón, T. H. Pardo de Tavera, Epifanio de los Santos,

Mariano Ponce, Pedro A. Paterno, Isabelo de los Reyes, and Jaime

C. de Veyra. For certain reasons, however, work on the project

was deferred. For one thing, the needed sources of information

were not then available. For another, the events of the last years

3 History of the Indian Archipelago (Edinburgh) II, 277-278.

4 The Observer 16 December 1956. A copy of Toynbee's article

was received from Mr. Alejandro R. Roces, Dean, Institute of Arts

and Sciences, Far Eastern University.

This content downloaded from

52.74.166.170 on Tue, 23 Feb 2021 03:35:33 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

NOTES AND COMMENT 459

of Spanish rule were deemed too close to perm

historical facts with complete objectivity and

It was thought advisable to postpone the writing of the history

until after the lapse of at least ten years.

In 1918, Epifanio de los Santos urged further postponement.

At that time the needed sources of information were still quite

inadequate. De los Santos suggested that Filipino scholars should,

in the meantime, undertake monographic studies, on the basis of

the source material then available, to clarify vague and obscure

points of history or to bring to light little known facts of Phil-

ippine history.5

A number of excellent monographs on various aspects of Phil-

ippine history were produced by Filipino scholars before the Sec-

ond World War. In the meantime, the resources of the National

Library as regards Filipiniana material were augmented to such

an extent that, before the War, the National Library was reputed

to have one of the richest collections of Filipiniana in existence.

Unfortunately, the last war wrought havoc to that collection as

well as to Filipiniana collections in private institutions and in the

libraries of private individuals.

Fortunately for us, the National Archives with its rich col-

lection of original documents was saved from destruction. The

Archives is a treasure of incalculable value to the student of Phil-

ippine history. In its present condition, however, the Archives is

not of much value for research purposes. The documents, num-

bering, according to official reports, no less than eleven million,

are in a deplorable state of disarrangement and confusion. A

great portion of the documents are not classified and catalogued.

The government does not seem to be seriously concerned over the

condition in which the collection is at present found. Its attitude

of indifference and neglect does not speak well of our sense of

historical and cultural values.

In the interest of historical scholarship in this country, the

documents in the Archives ¡should as soon as possible be put in

order. Steps must also be taken for the undertaking, under govern-

ment auspices, of a well planned program of acquisition from for-

eign archives of copies of historical material relating to the Phil-

ippines which we do not have here. Much valuable work has been

ò E. de los Santos "Historiografia Filipina" The Philippine Re-

view III (July 1918).

This content downloaded from

52.74.166.170 on Tue, 23 Feb 2021 03:35:33 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

460 PHILIPPINE STUDIES

done along this line by some of our schol

racio de la Costa, S.J., Dr. Domingo Abel

and Mr. Carlos Quirino. The work must be prosecuted in a sus-

tained manner with full financial backing from the government.

There is every reason to believe that Filipino historians, ii

given the necessary facilities, can produce a work of historical

scholarship that can commend itself to the respect and admiration

of scholars anywhere in the world and, at the same time, can meet

adequately our need for a thoroughly satisfactory history of the

Philippines.

Nicolas Zafra

The Good American

THE UGLY AMERICAN is the title of a much-discussed book,

recently published, which purports to be a description of the typical

American who takes up the "white man's burden" in Southeast

Asia. Read with glee by some, with annoyance by others, it has

been condemned in an American magazine as "a series of crude

black-and-white cartoons," a "blatant oversimplification." It is

not our intention at the moment to discus® the merits or demerits

of this book. Ours is a happier - and in another sense a sadder -

task. It is to pay a passing tribute to an American couple whose

visit to the Philippines was a pleasure to us, and whose departure

was a loss. Their names: John and Gloria Reed of the Asia

Foundation.

The extent of their influence in Manila became apparent only

when the news of their imminent departure began to be circulated.

Then people from almost every class of society and from almost

every walk of life joined in a continuous and amazing demonstra-

tion of esteem. One asalto party - when members of Manila's

art circle contributed funds to purchase a painting and then con-

verged upon the Reed home to present it to them - was revealing.

"What touches me," said Mr. Reed in a whisper to one of the

uninvited guests (for none of the guests were invited), "is not the

painting - though I like it - nor the scroll - though I shall always

This content downloaded from

52.74.166.170 on Tue, 23 Feb 2021 03:35:33 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

You might also like

- RegentsQA Ebook Feb5 2016 PDFDocument243 pagesRegentsQA Ebook Feb5 2016 PDFHade LopezNo ratings yet

- Rphist 1 Readings IN Philippine History: A Self-Regulated LearningDocument24 pagesRphist 1 Readings IN Philippine History: A Self-Regulated LearningKief sotero0% (1)

- History 165Document16 pagesHistory 165Maria MontelibanoNo ratings yet

- 2-Stress-Test Your Strategy The 7 Questions To AskDocument9 pages2-Stress-Test Your Strategy The 7 Questions To AskMalaika KhanNo ratings yet

- The Philippines A Past Revisited by RenaDocument10 pagesThe Philippines A Past Revisited by Renastudent researcherNo ratings yet

- The Historian's Task in The PhilippinesDocument3 pagesThe Historian's Task in The PhilippinesMace MaclangNo ratings yet

- Roke TsanDocument53 pagesRoke Tsanhittaf_05No ratings yet

- Physics Universe ModelsDocument14 pagesPhysics Universe ModelsTracy zorca50% (2)

- Understanding Philippine History Through Local PerspectivesDocument24 pagesUnderstanding Philippine History Through Local PerspectivesBobson Lacao-caoNo ratings yet

- Aquilion ONE GENESIS Edition Transforming CTDocument40 pagesAquilion ONE GENESIS Edition Transforming CTSemeeeJuniorNo ratings yet

- Riph2 - Assignamnet 2-Padrigo, Jammie JoyceDocument17 pagesRiph2 - Assignamnet 2-Padrigo, Jammie JoyceJammie Joyce89% (9)

- Module 2 (Reviewer)Document5 pagesModule 2 (Reviewer)Mj PamintuanNo ratings yet

- The Impact of Interest Rates On Economic Growth in KenyaDocument41 pagesThe Impact of Interest Rates On Economic Growth in KenyaSAMUEL KIMANINo ratings yet

- Creative 2nd QuarterDocument6 pagesCreative 2nd QuarterJanice CordovaNo ratings yet

- INTRO TO HISTORY AS DISCIPLINEDocument107 pagesINTRO TO HISTORY AS DISCIPLINELynnNo ratings yet

- The+Filipino+Point+of+View+In+Historical+Interpretation+As+Articulated+By+Teodoro+A +agoncilloDocument29 pagesThe+Filipino+Point+of+View+In+Historical+Interpretation+As+Articulated+By+Teodoro+A +agoncilloMarc GasolNo ratings yet

- The Philippines A Past Revisited Critique PaperDocument10 pagesThe Philippines A Past Revisited Critique PaperIDate DanielNo ratings yet

- Syllabus 1Document12 pagesSyllabus 1Jared TancoNo ratings yet

- 19thC NationalismDocument21 pages19thC NationalismDeanna Pacheco-Sudla100% (1)

- Ang Baho Ni JoshuaDocument3 pagesAng Baho Ni JoshuaDominic ReyesNo ratings yet

- Schumacher The Historians Task in The PhilippinesDocument5 pagesSchumacher The Historians Task in The PhilippinesGRAZIEL ANNE DELA RAMANo ratings yet

- The Filipino Point of View (BlockB)Document2 pagesThe Filipino Point of View (BlockB)LeyCodes LeyCodes100% (1)

- Philippine History from Colonial Era to RevolutionDocument6 pagesPhilippine History from Colonial Era to Revolutionglory ostulanoNo ratings yet

- The Historical Role of the Chinese Mestizo in the PhilippinesDocument40 pagesThe Historical Role of the Chinese Mestizo in the PhilippinesPhoebe ChuaNo ratings yet

- A Legacy of The Propaganda The Tripartite View of Phil History 2Document8 pagesA Legacy of The Propaganda The Tripartite View of Phil History 2mahry0% (1)

- The Filipino POV in Historical Interpretation As Articulated by Teodoro A. AgoncilloDocument3 pagesThe Filipino POV in Historical Interpretation As Articulated by Teodoro A. Agoncilloaminahzosa55No ratings yet

- Lesson 1 History and HistoriographyDocument6 pagesLesson 1 History and HistoriographyJohn Zedrick Iglesia100% (1)

- Philippine StudiesDocument23 pagesPhilippine StudiesYvan rosesherNo ratings yet

- Meaning and Importance of Philippine HistoriographyDocument3 pagesMeaning and Importance of Philippine HistoriographyAlexandra Caoile YuzonNo ratings yet

- Sagge, Bethel Love C. - M2Document19 pagesSagge, Bethel Love C. - M2Bethel Love SaggeNo ratings yet

- 54 Salazar - A Legacy of The PropagandaDocument13 pages54 Salazar - A Legacy of The PropagandaMiguel LigasNo ratings yet

- Klaud AbDocument5 pagesKlaud AbJoycel ManabatNo ratings yet

- A L P: T T V P H: Egacy of The Ropaganda HE Ripartite Iew of Hilippine IstoryDocument13 pagesA L P: T T V P H: Egacy of The Ropaganda HE Ripartite Iew of Hilippine IstoryVincent AgbayaniNo ratings yet

- Issues and Problems in Philippine HistoriographyDocument37 pagesIssues and Problems in Philippine HistoriographyJake Canlas100% (1)

- SE Asian History Journal Explores Chinese MestizosDocument40 pagesSE Asian History Journal Explores Chinese MestizosChloe DuarteNo ratings yet

- Dela Vega, Aira Essay 1Document3 pagesDela Vega, Aira Essay 1Aira Dela VegaNo ratings yet

- Chapter 2 SS1CDocument16 pagesChapter 2 SS1CKarl Agustine Guevarra CordovaNo ratings yet

- Sagge, Bethel Love C. - M3Document6 pagesSagge, Bethel Love C. - M3Bethel Love SaggeNo ratings yet

- The Chinese Mestizo in Philippine HistoryDocument42 pagesThe Chinese Mestizo in Philippine HistoryKris Anne Dela PenaNo ratings yet

- The Chinese Mestizo in Philippine HistoryDocument42 pagesThe Chinese Mestizo in Philippine HistoryJACOB AQUINTEYNo ratings yet

- The Chinese Mestizo in Philippine HistoryDocument42 pagesThe Chinese Mestizo in Philippine HistoryGee Lysa Pascua VilbarNo ratings yet

- Chapter 2 "The Awakening" and Chapter 5 "Canes and Paper Fans" Are Devoted To Furnishing ADocument3 pagesChapter 2 "The Awakening" and Chapter 5 "Canes and Paper Fans" Are Devoted To Furnishing ARoscelie KhoNo ratings yet

- Kasaysayan at TunggalianDocument10 pagesKasaysayan at TunggalianJennylyn EspinasNo ratings yet

- A History of Science in the Philippines from Colonial Times to the 1970sDocument33 pagesA History of Science in the Philippines from Colonial Times to the 1970sCarmela BuluranNo ratings yet

- Assign2 - BS Archi 1 4Document8 pagesAssign2 - BS Archi 1 4Lady Claire LeronaNo ratings yet

- Christ The King College: GEC 2: Readings in The Philippine HistoryDocument3 pagesChrist The King College: GEC 2: Readings in The Philippine HistoryMa. Joan ApolinarNo ratings yet

- Aprilyn Aquino SOCSCI 2125 Assignment For Reading 01Document2 pagesAprilyn Aquino SOCSCI 2125 Assignment For Reading 01Aprilyn AquinoNo ratings yet

- 1zeus Salazar - Tripartite View of Phil HistoryDocument13 pages1zeus Salazar - Tripartite View of Phil HistoryJhon Paul NaleNo ratings yet

- Module 1 & 2Document37 pagesModule 1 & 2katie joyNo ratings yet

- Activity1CriticalPaper MendozaNaiahDocument13 pagesActivity1CriticalPaper MendozaNaiahDonclyd JoseNo ratings yet

- CriticalPaper BorjaCharlie BABR1-2DDocument12 pagesCriticalPaper BorjaCharlie BABR1-2DMichael MagbanuaNo ratings yet

- Reading 3Document35 pagesReading 3dianne simanganNo ratings yet

- Significance of Primary Sources in Understanding Philippine HistoryDocument2 pagesSignificance of Primary Sources in Understanding Philippine HistoryShavv FernandezNo ratings yet

- RPH Rough ReportDocument7 pagesRPH Rough Reportsoft dumplingNo ratings yet

- The Philippines A Past RevisitedDocument17 pagesThe Philippines A Past Revisitedtj_simodlanNo ratings yet

- Philippine HistoriographyDocument25 pagesPhilippine HistoriographySUSHI CASPENo ratings yet

- DisinformationDocument15 pagesDisinformationJhenina CapulongNo ratings yet

- Philippine History Module Explores Roots of the DisciplineDocument15 pagesPhilippine History Module Explores Roots of the DisciplineAvery AriaNo ratings yet

- BCAEd01-A - MoniqueTagaban - ACTIVITY TIMEDocument3 pagesBCAEd01-A - MoniqueTagaban - ACTIVITY TIMEMonique G. TagabanNo ratings yet

- HistoryDocument7 pagesHistoryMa Jamil SablaonNo ratings yet

- Ileto, Outlines of A Non-Linear EmplotmentDocument15 pagesIleto, Outlines of A Non-Linear EmplotmentMika Roque100% (1)

- Chapter 1 - Introduction - 1st Sem 2021 2022Document14 pagesChapter 1 - Introduction - 1st Sem 2021 2022good yearNo ratings yet

- LaloyDocument2 pagesLaloyBill John PedregosaNo ratings yet

- 3 HistoriansDocument1 page3 HistoriansMark Luiz OlivarioNo ratings yet

- The Chinese Mestizo in Philippine HistoryDocument40 pagesThe Chinese Mestizo in Philippine HistoryCherie Diaz50% (2)

- EBOJODocument3 pagesEBOJORaselle EbojoNo ratings yet

- THE PHILIIPPINES: The Past Revisited by Renato ConstantinoDocument8 pagesTHE PHILIIPPINES: The Past Revisited by Renato ConstantinoLOIS ANNE RAZONNo ratings yet

- (Additional Notes) Flowcharting SymbolsDocument1 page(Additional Notes) Flowcharting SymbolsJared TancoNo ratings yet

- 1.1.2 How To Construct A FlowchartDocument16 pages1.1.2 How To Construct A FlowchartJared TancoNo ratings yet

- Reflection Paper LAS 20Document3 pagesReflection Paper LAS 20Jared TancoNo ratings yet

- 1.1.3 Flowchart StructureDocument11 pages1.1.3 Flowchart StructureJared TancoNo ratings yet

- 2.2B Log & CondDocument5 pages2.2B Log & CondJared TancoNo ratings yet

- Programmer:Database:Documentation:Testing:SupportDocument100 pagesProgrammer:Database:Documentation:Testing:SupportJessica FuertesNo ratings yet

- EssayDocument5 pagesEssayJared TancoNo ratings yet

- Filipina Immigrant's Struggle Revealed in Kings Cross Fruit StallDocument3 pagesFilipina Immigrant's Struggle Revealed in Kings Cross Fruit StallJared TancoNo ratings yet

- Template For LASDocument9 pagesTemplate For LASJared TancoNo ratings yet

- Thesis Statement:: 1. The Struggle of Asian-Americans With Racial Role InequalityDocument5 pagesThesis Statement:: 1. The Struggle of Asian-Americans With Racial Role InequalityJared TancoNo ratings yet

- Syllabus 2 Template ExampleDocument10 pagesSyllabus 2 Template ExampleJared TancoNo ratings yet

- Thesis Statement:: 1. The Struggle of Asian-Americans With Racial Role InequalityDocument5 pagesThesis Statement:: 1. The Struggle of Asian-Americans With Racial Role InequalityJared TancoNo ratings yet

- They Don'T Think Much About Us in America by Alfrredo Navarro SalangaDocument1 pageThey Don'T Think Much About Us in America by Alfrredo Navarro SalangaJared TancoNo ratings yet

- Laboratory Report # - : Title: Figure 1. Schematic Diagram Showing The Cart, Track and Motion SensorDocument2 pagesLaboratory Report # - : Title: Figure 1. Schematic Diagram Showing The Cart, Track and Motion SensorJared TancoNo ratings yet

- Why Creativity Is More Important Than Ever - IDEO UDocument6 pagesWhy Creativity Is More Important Than Ever - IDEO UJared TancoNo ratings yet

- Laboratory Report # - : Title: Figure 1. Schematic Diagram Showing The Cart, Track and Motion SensorDocument2 pagesLaboratory Report # - : Title: Figure 1. Schematic Diagram Showing The Cart, Track and Motion SensorJared TancoNo ratings yet

- 1920 Manuscript 7789 1 10 20141226Document6 pages1920 Manuscript 7789 1 10 20141226Jared TancoNo ratings yet

- 4 Ways To Improve Your Strategic Thinking Skills-1Document4 pages4 Ways To Improve Your Strategic Thinking Skills-1Jared TancoNo ratings yet

- Cpo 09 PDFDocument31 pagesCpo 09 PDFkrvn prkNo ratings yet

- Pixar's Creativity PhilosophyDocument39 pagesPixar's Creativity PhilosophyJared TancoNo ratings yet

- Interconnection of Power SystemsDocument5 pagesInterconnection of Power SystemsRohan Sharma50% (2)

- Biopharma SolutionDocument7 pagesBiopharma SolutionLili O Varela100% (1)

- Pharmaceutical and Software Development ProjectsDocument6 pagesPharmaceutical and Software Development ProjectsAlexandar123No ratings yet

- Lesson 1 G8Document11 pagesLesson 1 G8Malorie Dela CruzNo ratings yet

- Business Ethics Q3 Mod2 Foundations of The Principles of Business1Document5 pagesBusiness Ethics Q3 Mod2 Foundations of The Principles of Business1Julie CabusaoNo ratings yet

- Preschool ADHD QuestionnaireDocument2 pagesPreschool ADHD QuestionnaireAnnaNo ratings yet

- RRB NTPC Cut Off 2022 - CBT 2 Region Wise Cut Off Marks & Answer KeyDocument8 pagesRRB NTPC Cut Off 2022 - CBT 2 Region Wise Cut Off Marks & Answer KeyAkash guptaNo ratings yet

- Solid State Device Analysis ApproximationsDocument34 pagesSolid State Device Analysis Approximationsmrd9991No ratings yet

- GlobexiaDocument18 pagesGlobexianurashenergyNo ratings yet

- Bungsuan NHS Then and Now in PerspectiveDocument2 pagesBungsuan NHS Then and Now in Perspectivedanicafayetamagos02No ratings yet

- Lecture Notes in Computer Science-7Document5 pagesLecture Notes in Computer Science-7Arun SasidharanNo ratings yet

- Radioactive Half LifeDocument5 pagesRadioactive Half LifeVietNo ratings yet

- Downfall of Ayub Khan and Rise of Zulfikar Ali BhuttoDocument9 pagesDownfall of Ayub Khan and Rise of Zulfikar Ali Bhuttoabdullah sheikhNo ratings yet

- Ngāti Kere: What 87 Can Achieve Image 500Document17 pagesNgāti Kere: What 87 Can Achieve Image 500Angela HoukamauNo ratings yet

- DBMS Notes For BCADocument9 pagesDBMS Notes For BCAarndm8967% (6)

- Pharmaco-pornographic Politics and the New Gender EcologyDocument14 pagesPharmaco-pornographic Politics and the New Gender EcologyMgalo MgaloNo ratings yet

- A Lesson Plan in English by Laurence MercadoDocument7 pagesA Lesson Plan in English by Laurence Mercadoapi-251199697No ratings yet

- COLORMATCHING GUIDELINES FOR DEMI-PERMANENT HAIR COLORDocument1 pageCOLORMATCHING GUIDELINES FOR DEMI-PERMANENT HAIR COLORss bbNo ratings yet

- Colossians 1Document1 pageColossians 1aries john mendrezNo ratings yet

- 14-01 Lista de Laptops - DistribuidoresDocument29 pages14-01 Lista de Laptops - DistribuidoresInkil Orellana TorresNo ratings yet

- Aspen Separation Unit-OpsDocument25 pagesAspen Separation Unit-Opsedwin dableoNo ratings yet

- Toufik Hossain Project On ODE Using Fourier TransformDocument6 pagesToufik Hossain Project On ODE Using Fourier TransformToufik HossainNo ratings yet

- Ritual and Religion Course at University of EdinburghDocument10 pagesRitual and Religion Course at University of EdinburghRenata DC MenezesNo ratings yet

- Communalism in India - Causes, Incidents and MeasuresDocument5 pagesCommunalism in India - Causes, Incidents and Measures295Sangita PradhanNo ratings yet