Professional Documents

Culture Documents

BenBaranke Role-of-Govt in Reserach

Uploaded by

sushilkhannaOriginal Description:

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

BenBaranke Role-of-Govt in Reserach

Uploaded by

sushilkhannaCopyright:

Available Formats

Promoting Research and Development The Goverment's Role

Author(s): BEN S. BERNANKE

Source: Issues in Science and Technology , SUMMER 2011, Vol. 27, No. 4 (SUMMER 2011),

pp. 37-41

Published by: University of Texas at Dallas

Stable URL: https://www.jstor.org/stable/43315514

REFERENCES

Linked references are available on JSTOR for this article:

https://www.jstor.org/stable/43315514?seq=1&cid=pdf-

reference#references_tab_contents

You may need to log in to JSTOR to access the linked references.

JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide

range of content in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and

facilitate new forms of scholarship. For more information about JSTOR, please contact support@jstor.org.

Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of the Terms & Conditions of Use, available at

https://about.jstor.org/terms

is collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve and extend access to Issues in Science and

Technology

This content downloaded from

52.66.50.17 on Fri, 02 Jul 2021 11:49:41 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

BEN S. BERNANKE

Promoting Research

and Development

The Governments Role

The rationale for federal support for basic research

is well established, but the best policy for

implementing this principle remains open to debate.

les , if output per person increases more rapidly, the

Robert E. Lucas Jr. wrote that once one prospects for greater and more broad-based prosperity are

starts thinking about long-run growth significantly enhanced.

and economic development, "it is hard Over long spans of time, economic growth and the as o-

to think about anything else." Although ciated improvements in living standards reflect a number

I dont think I would go quite that far, it of determinants, including increases in workers' skil s, rates

The to starts and Robert is I dont certainly think Nobel economic thinking think E.isacbeortuatinlLyutrcuaesthtartureelaPtirviezlye-smwailndi-ing I would anything development, about that Jr. wrote relatively go long-run else." quite that economist "it that Although once smal growth is far, hard one di- it of saving and capital ac umulation, and institutional fac-

ferences in rates of economic growth, maintained over a tors ranging from the flexibility of markets to the quality of

sustained period, can have enormous implications for ma- the legal and regulatory frameworks. However, in ovation

terial living standards. A growth rate of output per person and technological change are undoubtedly central to the

of 2.5% per year doubles average living standards in 28 growth proces ; over the past 20 years or so, in ovation,

years - about one generation - whereas output per person technical advances, and investment in capital go ds em-

growing at what se ms a modestly slower rate of 1.5% a year bodying new technologies have transformed economies

leads to a doubling in average living standards in about 47 around the world. In recent decades, as this audience wel

years- roughly two generations. Compound interest is pow- knows, advances in semiconductor technology have radi-

erful! Of course, factors other than ag regate economic cal y changed many aspects of our lives, from communica-

growth contribute to changes in living standards for dif er- tion to health care. Technological developments further in

ent segments of the population, including shifts in relative the past, such as electrification or the internal combustion

wages and in rates of labor market participation. Nonethe- engine, were equal y revolutionary, if not more so. In ad i-

SUMMER 201 1 37

This content downloaded from

52.66.50.17 on Fri, 02 Jul 2021 11:49:41 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

tion, recent research has highlighted the important role private market would not adequately supply certain types

played by intangible capital, such as the knowledge embod- of research. The argument, which applies particularly

ied in the workforce, business plans and practices, and brand strongly to basic or fundamental research, is that the full

names. This research suggests that technological progress economic value of a scientific advance is unlikely to accrue

and the accumulation of intangible capital have together ac- to its discoverer, especially if the new knowledge can be

counted for well over half of the increase in output per hour replicated or disseminated at low cost. For example, James

in the United States during the past several decades. Watson and Francis Crick received a minute fraction of the

Innovation has not only led to new products and more-ef- economic benefits that have flowed from their discovery of

ficient production methods, but it has also induced dramatic the structure of DNA. If many people are able to exploit, or

changes in how businesses are organized and managed, high- otherwise benefit from, research done by others, then the

lighting the connections between new ideas and methods total or social return to research may be higher on average

and the organizational structure needed to implement them. than the private return to those who bear the costs and risks

For example, in the 19th century, the development of the of innovation. As a result, market forces will lead to under-

railroad and telegraph, along with a host of other technolo- investment in R&D from society's perspective, providing a

gies, was associated with the rise of large businesses with na- rationale for government intervention.

tional reach. And as transportation and communication tech- One possible policy response to the market underprovi-

nologies developed further in the 20th century, multinational sion problem would be to substantially strengthen the in-

corporations became more feasible and prevalent. tellectual property rights regime; for example, by granting the

Economic policy affects innovation and long-run eco- developers of new ideas strong and long-lasting claims to

nomic growth in many ways. A stable macroeconomic en- the economic benefits of their discoveries - perhaps by ex-

vironment; sound public finances; and well-functioning fi- tending and expanding patent rights. This approach has sig-

nancial, labor, and product markets all support innovation, nificant drawbacks of its own, however, in that strict limita-

entrepreneurship, and growth, as do effective tax, trade, and tions on the free use of new ideas would inhibit both further

regulatory policies. Policies directed at objectives such as research and the development of valuable commercial appli-

the protection of intellectual property rights and the pro- cations. Thus, although patent protections and similar rules

motion of research and development, or R&D, promote in- remain an important part of innovation policy, governments

novation and technological change more directly. have also turned to direct support of R&D activities.

I will focus on one important component of innovation Of course, the rationale for government support of R&D

policy: government support for R&D. As I have already sug- would be weakened if governments had consistently per-

gested, the effective commercial application of new ideas formed poorly in this sphere. Certainly there have been dis-

involves much more than just pure research. Many other appointments; for example, the surge in federal investment

factors are relevant, including the extent of market compe- in energy technology research in the 1970s, a response to

tition, the intellectual property regime, and the availability the energy crisis of that decade, achieved less than its initia-

of financing for innovative enterprises. That said, the ten- tors hoped. In the United States, however, we have seen many

dency of the market to supply too little of certain types of examples- in some cases extending back to the late 19th and

R&D provides a rationale for government intervention; and early 20th centuries- of federal research initiatives and gov-

no matter how good the policy environment, big new ideas ernment support enabling the emergence of new technolo-

are often ultimately rooted in well-executed R&D. gies in areas that include agriculture, chemicals, health care,

and information technology. A case that has been particularly

The rationale for a government role well documented and closely studied is the development of

Governments in many countries directly support scientific hybrid seed corn in the United States during the firßt half of

and technical research; for example, through grant-provid- the 20th century. Two other examples of innovations that

ing agencies (like the National Science Foundation in the received critical federal support are gene splicing- federal

United States) or through tax incentives (like the R&D tax R&D underwrote the techniques that opened up the field of

credit). In addition, the governments of the United States genetic engineering - and the lithium-ion battery; which was

and many other countries run their own research facilities, developed by federally sponsored materials research in the

including facilities focused on nonmilitary applications such 1980s. And recent research on the governments so-called

as health. The primary economic rationale for a govern- War on Cancer, initiated by President Nixon in 1971, finds

ment role in R&D is that, without such intervention, the that the effort has produced a very high social rate of return,

38 ISSUES IN SCIENCE AND TECHNOLOGY

This content downloaded from

52.66.50.17 on Fri, 02 Jul 2021 11:49:41 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

GOVERNMENT ROLE IN R&D

Contrary to the notion that highly trained and talented immigrants

displace native-born workers in the labor market, scientists and other

highly trained professionals who come to the United States tend to enhan

the productivity and employment opportunities of those already here.

notwithstanding its failure to achieve its original ambitious

be sure, R&D spending remains concentrated in the most

goal of eradicating the disease. developed countries, with the United States still the leade

What about the present? Is government supportin

ofoverall

R&D R&D spending. However, in recent years, spend

ing on R&D has increased sharply in some emerging mar

today at the "right" level? This question is not easily answered;

ketalso

it involves not only difficult technical assessments but economies,

a most notably in China and India. In partic

number of value judgments about public priorities. As back-

ular, spending for R&D by China has increased rapidly in ab-

ground, however, a consideration of recent trends insolute

expen-terms, although recent estimates still show its R&

ditures on R&D in the United States and the rest of the world to be smaller relative to GDP than in the Unite

spending

should be instructive. In the United States, total R&DStates.

spend- Reflecting the increased research activity in emerg

ing (both public and private) has been relatively stable over

ing market economies, the share of world R&D expendi

the past three decades, at roughly 2.5% of gross domestic

tures by member nations of the Organization for Econom

product (GDP). However, this apparent stability masks some

Co-Operation and Development, which mostly comprises

important underlying trends. First, since the 1970s,advanced

R&D economies, has fallen relative to nonmember na

spending by the federal government has trended down

tions,aswhich

a tend to be less developed. A similar trend

share of GDP, while the share of R&D done by the privateby the way, with respect to science and engineering

evident,

sector has correspondingly increased. Second, the workforces.

share of

R&D spending targeted to basic research, as opposed to more

How should policymakers think about the increasing

applied R&D activities, has also been declining. These two

globalization of R&D spending? On the one hand, the di

trends- the declines in the share of basic research and in the

fusion of scientific and technological research throughout th

federal share of R&D spending - are related, as government

world potentially benefits everyone by increasing the pac

R&D spending tends to be more heavily weightedoftowardinnovation globally. For example, the development of the

basic research and science. The declining emphasis polio ba-

on vaccine in the United States in the 1950s provided

sic research is somewhat concerning because fundamental re-

enormous benefits to people globally, not just Americans

search is ultimately the source of most innovation, albeit of-

Moreover, in a globalized economy, product and process in

ten with long lags. Indeed, some economists havenovations

argued in one country can lead to employment oppor

that because of the potentially high social return to basic re- and improved goods and services around the worl

tunities

search, expanded government support for R&D could, Onover

the other hand, in some circumstances the locatio

time, significantly boost economic growth. That said,

of R&Din aactivity can matter. For example, technologic

time of fiscal stringency, Congress and the administration

prowess may help a country reap the financial and employ

will clearly need to carefully weigh competing priorities in

ment benefits of leadership in a strategic industry. A cutting

their budgetary decisions. edge scientific or technological center can create a variety of

Another argument sometimes made for expanding gov- that promote innovation, quality, skills acquisi

spillovers

ernment support for R&D is the need to keep pace with

tion, and productivity in industries located nearby; suc

technological advances in other countries. R&D hasspillovers

become are the reason that high-tech firms often locate in

increasingly international, thanks to improved communi-

clusters or near leading universities. To the extent that coun

cation and dissemination of research results, the spread of from leadership in technologically vibrant indu

tries gain

scientific and engineering talent around the world, and the

tries or from local spillovers arising from inventive activity

transfer of technologies through trade, foreign direct

theinvest-

case for government support of R&D within a given coun

ment, and the activities of multinational corporations.

try is To

stronger.

SUMMER 2011 39

This content downloaded from

52.66.50.17 on Fri, 02 Jul 2021 11:49:41 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

How should governments provide support? However it is channeled, government support for inno-

The economic arguments for government support of inno- vation and R&D will be more effective if it is thought of as

vation generally imply that governments should focus par- a long-run investment. Gestation lags from basic research to

ticularly on fostering basic, or foundational, research. The commercial application to the ultimate economic benefits can

most applied and commercially relevant research is likely be very long. The Internet revolution of the 1990s was based

to be done in any case by the private sector, as private firms on scientific investments made in the 1970s and 1980s. And

have strong incentives to determine what the market de- todays widespread commercialization of biotechnology was

mands and to meet those needs. based, in part, on key research findings developed in the

If the government decides to foster R&D, what policy in- 1950s. Thus, governments that choose to provide support

struments should it use? A number of potential tools exist,for R&D are likely to get better results if that support is sta-

including direct funding of government research facilities,ble, avoiding a pattern of feast or famine.

grants to university or private-sector researchers, contracts Government support for R&D presumes sufficient na-

for specific projects, and tax incentives. Moreover, withintional capacity to engage in effective research at the desired

each of these categories, many choices must be made aboutscale. That capacity, in turn, depends importantly on the

how to structure specific programs. Unfortunately, econo-supply of qualified scientists, engineers, and other technical

mists know less about how best to channel public support for workers. Although the system of higher education in the

R&D than we would like; it is good news, therefore, thatUnited States remains among the finest in the world, nu-

considerable new work is being done on this topic, includ-merous concerns have been raised about this country's abil-

ing recent initiatives on science policy by the National Sci-ity to ensure adequate supplies of highly skilled workers.

ence Foundation. For example, some observers have suggested that bottle-

Certainly, the characteristics of the research to be sup-necks in the system limit the number of students receiving

ported are important for the choice of the policy tool. Directundergraduate degrees in science and engineering. Surveys

government support or conduct of the research may make of student intentions in the United States consistently show

the most sense if the project is highly focused and large-that the number of students who seek to major in science

scale, possibly involving the need for coordination of theand engineering exceeds the number accommodated by a

wide margin, and waitlists to enroll in technical courses

work of many researchers and subject to relatively tight time

frames. Examples of large-scale government-funded re-have trended up relative to those in other fields, as has the

search include the space program and the construction and time required to graduate with a science or engineering de-

operation of "atom-smashing" facilities for experiments in gree. Moreover, although the relative wages of science and

high-energy physics. Outside of such cases, which often are engineering graduates have increased significantly over the

linked to national defense, a more decentralized model that past few decades, the share of undergraduate degrees

relies on the ideas and initiative of individual researchers

awarded in science and engineering has been roughly stable.

or small research groups may be most effective. Grants to,At the same time, critics of K-12 education in the United

or contracts with, researchers are the typical vehicle for such States have long argued that not enough is being done to

an approach. encourage and support student interest in science and math-

Of course, the success of decentralized models for govern- ematics. Taken together, these trends suggest that more could

ment support depends on the quality of execution. Some be done to increase the number of U.S. students entering

critics believe that funding agencies have been too cautious,scientific and engineering professions.

focusing on a limited number of low- risk projects and tar- At least when viewed from the perspective of a single na-

geting funding to more-established scientists at the expense tion, immigration is another path for increasing the supply

of researchers who are less established or less conventional

of highly skilled scientists and researchers. The technologi-

in their approaches. Supporting multiple approaches to a cal leadership of the United States was and continues to be

given problem at the same time increases the chance of find- built in substantial part on the contributions of foreign-born

scientists and engineers, both permanent immigrants and

ing a solution; it also increases opportunities for cooperation

or constructive competition. The challenge to policymak-those staying in the country only for a time. And, contrary

ers is to encourage experimentation and a greater diversityto the notion that highly trained and talented immigrants

of approaches while simultaneously ensuring that an effec-displace native-born workers in the labor market, scientists

tive peer-review process is in place to guide funding toward and other highly trained professionals who come to the

high-quality science. United States tend to enhance the productivity and employ-

40 ISSUES IN SCIENCE AND TECHNOLOGY

This content downloaded from

52.66.50.17 on Fri, 02 Jul 2021 11:49:41 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

GOVERNMENT ROLE IN R&D

ment opportunities of those already here, reflecting gains Access," Innovation Policy and the E

in Internet

8 (2007): 59-109.

from interaction and cooperation and from the development

Zvi Griliches,

of critical masses of researchers in technical areas. More gen- "Research Cost and Social Returns:

erally, technological progress and innovation around

Corn andthe

Related Innovations," Journal of Political

world would be enhanced by lowering national omy 66, no.

barriers to 5 (1958): 419-431.

Bronwyn H. Hall, Jacques Mairesse, and Pierre M

international scientific cooperation and collaboration.

In the abstract, economists have identified some persua- the Returns to R&D (National Bureau

Measuring

sive justifications for government policies to promote R&D

nomic Research Working Paper 15622, Cambridg

NBER,

activities, especially those related to basic research. 2009).

In prac-

tice, we know less than we would like about Kenneth

whichG.policies

Huang and Fiona E. Murray, "Entrepreneurial

work best. A reasonable strategy for now mayExperiments

be to con-in Science Policy: Analyzing the Human

Genometaking

tinue to use a mix of policies to support R&D while Project," Research Policy 39, no. 5 (2010):

pains to encourage diverse and even competing567-582.

approaches

Adam B. Jaffe, "Real Effects of Academic Research," Amer-

by the scientists and engineers receiving support.

We should also keep in mind that funding R&D icanactivity

Economic Review 79, no. (5 (1989): 957-970.

is only part of what the government can do toCharles

foster I.inno-

Jones and John C. Williams, "Measuring the So-

vation. As I noted, ensuring a sufficient supply ofcial Return to R&D," Quarterly Journal of Economics

individu-

113,

als with science and engineering skills is important forno. 4 (1998): 1119-1135.

pro-

moting innovation, and this need raises questions

Darius about ed- Eric Sun, Anupam Jena, Carolina Reyes,

Lakdawalla,

Dana Golman,

ucation policy as well as immigration policy. Other key and Tomas Philipson, "An Economic

policy issues include the definition and enforcement of of

Evaluation in-the War on Cancer," Journal of Health Eco-

nomics

tellectual property rights and the setting of technical 29, no. 3 (2010): 333-346.

stan-

dards. Finally, as someone who spends a lot Julia

of time moni-

Lane, "Assessing the Impact of Science Funding," Sci-

ence

toring the economy, let me put in a plug for more 324on

work (2009): 1273-1275.

finding better ways to measure innovation,Robert E. Lucas Jr., "On the Mechanics of Economic Devel-

R&D activity,

and intangible capital. We will be more likely to promote

opment," Journal of Monetary Economics 22, no. 1 (1988):

3-42. effec-

innovative activity if we are able to measure it more

R. R. Nelson, "The Simple Economics of Basic Scientific Re-

tively and document its role in economic growth.

search," Journal of Political Economy 67, no. 3 (1959):

Recommended reading 297-306.

Kenneth J. Arrow, "The Economic Implications

Rogerof

G. Learn-

Noll, "Federal R&D in the Antiterrorist Era," Inno-

ing by Doing," Review of Economic Studiesvation

29, no. 3

Policy and the Economy 3 (2003): 61-89.

(1962): 155-173. Paul M. Romer, "Should the Government Subsidize Supply

Carol Corrado, Charles Hulten, and Daniel Sichel, "Intan-

or Demand in the Market for Scientists and Engineers?"

gible Capital and U.S. Economic Growth," The ReviewPolicy and the Economy 1 (2000): 221-252.

Innovation

of Income and Wealth 55 (September 2009): 661-685.

Paul A. David, Bronwyn H. Hall, and Andrew A.S.Toole,

Ben "Is is chairman of U.S. Federal Reserve Board

Bernanke

Public R&D a Complement or Substitute This

for article

Private

is derived from a speech he gave at the New Build-

R&D? A Review of the Econometric Evidence," Research

ing Blocks for Jobs and Economic Growth Conference in Wash-

Policy 29, no. 4-5 (2000): 497-529. ington , DC, sponsored by the Organisation for Economic Co-

Richard Freeman and John Van Reenen, "What if Congress

operation and Development; the Athena Alliance; the Confer-

Doubled R&D Spending on the Physical Sciences?"

ence Board ; In-

the Kauffman Foundation ; the National Academies

novation Policy and the Economy 9 (2009): 1-38.

Board on Science , Technology ; and Economic Policy; and the

Shane Greenstein, "Economic Experiments and Neutrality

Georgetown Center for Business and Public Policy.

SUMMER 2011 41

This content downloaded from

52.66.50.17 on Fri, 02 Jul 2021 11:49:41 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

You might also like

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)From EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Rating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (122)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryFrom EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (231)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceFrom EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (589)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingFrom EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (401)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeFrom EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (537)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItFrom EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (842)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceFrom EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (897)

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeFrom EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (5806)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersFrom EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (345)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaFrom EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (266)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerFrom EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (271)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnFrom EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (234)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyFrom EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (2259)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesFrom EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (821)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreFrom EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (1091)

- Cooling System: Description and OperationDocument26 pagesCooling System: Description and OperationrodolfodiazNo ratings yet

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureFrom EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (474)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealFrom EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (74)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)From EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Rating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (98)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaFrom EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (45)

- 2nd QTR 1st Summative Test in TrendsDocument1 page2nd QTR 1st Summative Test in TrendsEbb Tenebroso Judilla100% (1)

- OM Scott Case AnalysisDocument20 pagesOM Scott Case AnalysissushilkhannaNo ratings yet

- 2000 m72M013023 - 02EDocument42 pages2000 m72M013023 - 02EDimas Saputro100% (1)

- Smart Metering - IEEMADocument17 pagesSmart Metering - IEEMARouxcel abutoNo ratings yet

- Flygt F-Pump Series PDFDocument8 pagesFlygt F-Pump Series PDFLungisani100% (1)

- PESTLE Analysis - Doing Business in AustraliaDocument24 pagesPESTLE Analysis - Doing Business in Australiatushars650No ratings yet

- Economics of Unconventional Shale Gas Development - William E. Hefley & Yongsheng WangDocument248 pagesEconomics of Unconventional Shale Gas Development - William E. Hefley & Yongsheng WangAlexEvansNo ratings yet

- CG & AccountabilityDocument60 pagesCG & AccountabilitysushilkhannaNo ratings yet

- 2.SK CorpGovernance AngloSaxonViewDocument15 pages2.SK CorpGovernance AngloSaxonViewsushilkhannaNo ratings yet

- Anglo Saxon ModelDocument1 pageAnglo Saxon ModelsushilkhannaNo ratings yet

- CitiesService Takeover CaseDocument20 pagesCitiesService Takeover CasesushilkhannaNo ratings yet

- SK PoliticalEco SOEs in IndiaREVDocument61 pagesSK PoliticalEco SOEs in IndiaREVsushilkhannaNo ratings yet

- Financialsation & CrisisDocument20 pagesFinancialsation & CrisissushilkhannaNo ratings yet

- Growth and Crisis in Pakistan's Economy: Sushil KhannaDocument8 pagesGrowth and Crisis in Pakistan's Economy: Sushil KhannasushilkhannaNo ratings yet

- Separation of Substances Part ADocument3 pagesSeparation of Substances Part ARahulKumbhareNo ratings yet

- 0089292-OMCompr GEA Grasso Reciprocating 2017Document18 pages0089292-OMCompr GEA Grasso Reciprocating 2017Christian CotteNo ratings yet

- Amm Case StudyDocument7 pagesAmm Case StudyManisha KhuranaNo ratings yet

- 1996-2004 - Ford4.6Mustang Mustang Mustang Mustang GTDocument40 pages1996-2004 - Ford4.6Mustang Mustang Mustang Mustang GTPa RaNo ratings yet

- Digital Power Supply Case (S400) Assembly Instruction PDFDocument11 pagesDigital Power Supply Case (S400) Assembly Instruction PDFtékahef HuideusepNo ratings yet

- Z - Chemical Process Industries - K, N IndustriesDocument68 pagesZ - Chemical Process Industries - K, N IndustriesZVSNo ratings yet

- MG-3010 ManualDocument8 pagesMG-3010 ManualRomulo Oliveira AraujoNo ratings yet

- Problems 3Document2 pagesProblems 3Trần Xuân AnhNo ratings yet

- Rab Task TemplateDocument5 pagesRab Task TemplatelukmanNo ratings yet

- Chapter 3Document29 pagesChapter 32360459No ratings yet

- Chapter 1 Waves SPMDocument4 pagesChapter 1 Waves SPMAzwin NuraznizaNo ratings yet

- Data Sheet: ACPL-C78A, ACPL-C780, ACPL-C784Document17 pagesData Sheet: ACPL-C78A, ACPL-C780, ACPL-C784Jamal NasirNo ratings yet

- Tiger N-Type 60TR: 355-375 WattDocument2 pagesTiger N-Type 60TR: 355-375 WattmoonridergNo ratings yet

- Ratings Guide BrochureDocument18 pagesRatings Guide Brochureengrmafzal89No ratings yet

- Lynx Drilling Mud Decanter Lynx Range Second GenerationDocument4 pagesLynx Drilling Mud Decanter Lynx Range Second GenerationWarlexNo ratings yet

- Overhead Line ConductorDocument30 pagesOverhead Line ConductorArif AliNo ratings yet

- Curriculum Vitae: Examination Name of Institution Month & Year of Passing Class / Grade Name of UniversityDocument3 pagesCurriculum Vitae: Examination Name of Institution Month & Year of Passing Class / Grade Name of Universitybhagirath kansaraNo ratings yet

- Product Data: 39T Central Station Air-Handling UnitsDocument100 pagesProduct Data: 39T Central Station Air-Handling UnitsJesus CantuNo ratings yet

- CP3mini Op Inst 2549076Document56 pagesCP3mini Op Inst 2549076Rawnee HoNo ratings yet

- Product Data Sheet LT 80P: Siegling - Total Belting SolutionsDocument2 pagesProduct Data Sheet LT 80P: Siegling - Total Belting SolutionsGuilherme AugustoNo ratings yet

- Part 4.4 - CivilDocument334 pagesPart 4.4 - Civilanjas_tsNo ratings yet

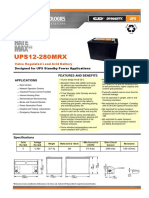

- UPS12-280MRX: Valve Regulated Lead Acid BatteryDocument2 pagesUPS12-280MRX: Valve Regulated Lead Acid BatteryCristopher JayloNo ratings yet

- Vietnam Journal of Chemistry - 2020 - Nam - Pyrolysis of Cashew Nut Shell A Parametric StudyDocument6 pagesVietnam Journal of Chemistry - 2020 - Nam - Pyrolysis of Cashew Nut Shell A Parametric StudyTrần Thuý QuỳnhNo ratings yet