Professional Documents

Culture Documents

KemeE Abiayala 2018

Uploaded by

vilchesfOriginal Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

KemeE Abiayala 2018

Uploaded by

vilchesfCopyright:

Available Formats

For Abiayala to Live, the Americas Must Die: Toward a Transhemispheric Indigeneity

Author(s): Emil Keme and Adam Coon

Source: Native American and Indigenous Studies , Vol. 5, No. 1 (Spring 2018), pp. 42-68

Published by: University of Minnesota Press

Stable URL: https://www.jstor.org/stable/10.5749/natiindistudj.5.1.0042

REFERENCES

Linked references are available on JSTOR for this article:

https://www.jstor.org/stable/10.5749/natiindistudj.5.1.0042?seq=1&cid=pdf-

reference#references_tab_contents

You may need to log in to JSTOR to access the linked references.

JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide

range of content in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and

facilitate new forms of scholarship. For more information about JSTOR, please contact support@jstor.org.

Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of the Terms & Conditions of Use, available at

https://about.jstor.org/terms

University of Minnesota Press is collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve and extend access

to Native American and Indigenous Studies

This content downloaded from

128.83.214.19 on Tue, 19 Jan 2021 06:57:10 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

EMIL KEME

For Abiayala to Live, the Americas

Must Die: Toward a Transhemispheric

Indigeneity

Translated by Adam Coon

We don’t need permission to be free.

—ZAPATISTA ARMY OF NATIONAL LIBERATION

FOR THE READER not yet familiar with the category of Abiayala,1 it comes from

the cosmogony of the Guna population, an Indigenous nation in the region

of Guna Yala (or the land of the Guna), formally known as San Blas in pres-

ent-day Panama.2 Abiayala in the Guna language means “land in full matu-

rity” or “saved territory” (Aiban Wagua, 342). According to Guna cosmogony,

up to the present, four historical stages have occurred in the evolution and

formation of Mother Earth. Each stage is designated by a different name. The

first is Gwalagunyala. At this stage, after being created, the earth was conse-

quently hit by cyclones. The second, Dagargunyala, is characterized by being

a stage of chaos, disease, and fear that culminates in darkness. In the third,

Dinguayala, Mother Earth is tormented by fire. Today we live in the fourth

stage: Abiayala, that of the “territory saved, preferred, and loved by Baba

and Nana” (Aiban Wagua, 342). Abiayala is also the name that the Guna use

to refer to what for others is the American continent as a whole. The con-

cept came to have continental repercussions after the Aymara leader Takir

Mamani, one of the founders of the Tupaj Katari Indigenous rights move-

ment in Bolivia, arrived in Panama. He heard about the conflict between

Guna authorities and the American investor Thomas M. Moody, who in 1977

had “bought” the island of Pidertupi in the Guna Yala territory and who since

then has begun to exploit tourism in the region. Moody consequently prohib-

ited the Guna from fishing around the island, which created a deep tension

between the Indigenous people and the American. The Guna then “requested

the intervention of the president of the republic [Omar T orrijos Herrera]

to eliminate Moody’s tourist enterprise and also requested his support to

establish tourist hotels operated by the Guna themselves” (Pereiro et al., 82).

When the Indigenous demands were ignored, young Guna attacked Moody

42 Emil Keme NA IS 5:1 2 0 18

This content downloaded from

128.83.214.19 on Tue, 19 Jan 2021 06:57:10 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

and his wife, burned their hotel and their yacht, and killed two policemen.

Moody subsequently took refuge in the U.S. embassy and accused the Guna of

being “communists” who sought to take over the country and do away with

the “Yankees.” The news was widely disseminated by newspapers and tele-

vision news programs in Panama. But in the end, the Guna were victorious in

winning a legal claim against Moody for the defense of their territories and

autonomy, which forced Moody to leave Guna Yala. The island of Pidertupi

consequently passed into the hands of the General Guna Congress (CGK).3

After hearing about these conflicts and the struggles for their territorial

autonomy in the Guna Yala territory, Mamani met with the saylas or Guna

authorities on the island of Ustupu. There they told him: “Everyone uses the

name of America for our continent, but we hold the true name Abya Yala” (in

Quillaguamán Sánchez, 3). Given his ability to travel to international forums,

the saylas then entrusted Mamani to disseminate this message to leaders

and representatives of other Indigenous nations with the goal of using the

“real name” of the continent. Mamani followed the saylas’ advice and spread

the message in various gatherings and international forums, asking Indige-

nous representatives and organizations that instead of using the names of

“America” or “Latin America” they use Abiayala to refer to the continent in

their official declarations. Mamani argues that “placing foreign names on

our villages, our cities, and our continents is equivalent to subjecting our

identities to the will of our invaders and their heirs” (in Quillaguamán Sán-

chez, 3, my translation). Therefore, renaming the continent would be the

first step toward epistemic decolonization and the establishment of Indig-

enous peoples’ autonomy and self-determination.4 Since the 1980s, many

Indigenous activists, writers, and organizations have embraced the Guna

people’s and Mamani’s suggestion, and Abiayala has become a way to refer

not only to the continent but also to a differentiated Indigenous locus of

cultural and political enunciation (Muyolema, 329).5

In this essay, I would also like to embrace the Guna people’s and M

amani’s

petition with the objective of proposing Abiayala as a transhemispheric

Indigenous bridge. By invoking this category, I propose to develop a dialogue

that could potentially lead us to develop political alliances in the forma-

tion of a new Indigenous and non-Indigenous historical bloc that opposes

ideas and civilizational Eurocentric projects like “Latin (America),” “Lati-

nity,” or “Americas,” as well as extractivist economies based on capitalism

and socialism at national, continental, and intercontinental levels.6 I believe

that the moment is appropriate given the permanent threats to our cul-

tures, languages, territories, and identities we face in every country in and

out of the hemisphere, against nation-states that characterize themselves

by recycling colonialist logics that continue disfavoring us. Like the struggle

N A I S 5: 1 2 0 18 For Abiayala to Live, the Americas Must Die 43

This content downloaded from

128.83.214.19 on Tue, 19 Jan 2021 06:57:10 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

of the Guna people against Moody and their epistemological articulation of

the category of Abiayala, we need to develop collective Indigenous strate-

gies and knowledges in the restitution and dignification of Indigenous life

and our sovereignties.

Transhemispheric Indigeneity

Before proceeding, I must offer some clarification. First, I evoke “Indige-

nous peoples” as a category that takes into account the contradictions this

entails. As is well known, when Christopher Columbus invaded our territo-

ries, he called the “New World” the “West Indies” and imposed on us the cat-

egory “Indian,” which imprisoned us epistemologically, erasing our “density”

or our deep complexities as Indigenous societies (Andersen). Since 1492 in

Abiayala, the category Indian “applied indiscriminately to the entire aborig-

inal population, without taking into account any of the profound differ-

ences that separated distinct peoples and without making concessions for

preexisting identities” (Bonfil Batalla, 111). Not only that, “Indian” has been

used to control and subjugate our identities in order to weaken our right to

use ethnic affiliations that mark our differences as nations, that is, as Nava-

jos, Cherokees, Aymaras, Mohawk, Mapuches, Maya K’iche’, and so on. We

should take into account, for example, that the first peoples of this conti-

nent “were by modern estimates divided into at least two thousand cultures

and more societies, practiced a multiplicity of customs and lifestyles, held

an enormous variety of values and beliefs, spoke numerous languages mutu-

ally unintelligible to the many speakers, and did not conceive of themselves

as a single people—if they knew about each other at all” (Berkhofer, 3).7 It

is important to recognize that definitions of Indigenous identity have colo-

nial origins and that instead of constituting unified, fixed, and unchangeable

constructions, these are characterized by being hybrid, restructured, and

renegotiated constantly and historically at the local, national, and global

levels.8

Hence we must also recognize that we are colonized subjects, operat-

ing within the spaces and institutional structures established by Spanish,

French, Dutch, Portuguese, and British colonialisms and the consequent

internal/settler colonialisms established by the descendants of the first

invaders. These experiences have obviously generated complicated rela-

tionships between Indigenous nations, our territories, the nation-state,

and modernity that are characterized by what Osage Nation anthropologist

Jean Dennison has called “colonial entanglements.” That is, our struggles

for self-determination depend on continual negotiations, as well as on the

development and construction of criticisms that decentralize and dismantle

44 Emil Keme NA IS 5:1 2 0 18

This content downloaded from

128.83.214.19 on Tue, 19 Jan 2021 06:57:10 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

dominant Latin American narratives based on our sacrifices and the appro-

priation of our knowledges. We must recognize that the processes of con-

quest have not been finished or abandoned. Rather, the “logic of elimina-

tion of the native”—to evoke the work of Patrick Wolfe—continues to be the

organizing principle of modern nation-states and their hegemonic institu-

tions. These use various tactics to access Indigenous territories, often with

the complicity or strategies of co-optation of Indigenous sectors that have

allowed the nation-state to achieve its political and economic objectives. It

is, then, a question of counteracting these logics by questioning the forces

that shape, restrict, or create opportunities for the transformation and con-

sequent articulation of a project that vindicates us individually and collec-

tively. Decolonization should not be a metaphor (Tuck and Yung) given that

today—as in the past—from south to north, from east to west, we continue

fighting to defend our territories and to regain our sovereignties. We have

every right to restore and dignify our lives as Indigenous peoples given that

we have been here for thousands of years.

I must reiterate that in saying this I do not think only of our epistemo-

logical and political challenges to the West and its colonial legacies. Several

Indigenous women and men have also internalized and recycled the values

bequeathed by the invaders and their descendants. We must not ignore

those criticisms that point to how the internalization of European values

among black and Indigenous classes granted some authority have led them

to oppress their own sisters and brothers, at times in even more cruel and

ferocious fashion. A confrontation with the hegemonic system must begin

with an assessment and confrontation with ourselves. We must recog-

nize that at many historical moments we have been active participants in

the affirmation of Western values, which include, among other things, the

assertion of a heteropatriarchal and heterosexual system that excludes

Indigenous women or attitudes that disrespect the rights of those with dif-

ferent sexual orientations.

In sum, while we recognize the limits of the category “Indian” or “Indig-

enous,” the homogenization of our experiences has articulated principles

that united us. As Craig Womack underscores, though Indigenous Nations

“have different languages, different ceremonies, different religions, dif-

ferent economies, different histories, different forms of government, they

all share a legacy of stolen land, decimated populations, and engineered

cultural theft” (237). In this sense, despite the colonial and entangled ori-

gins, the concepts of “Indigenous” and “Indigeneity” continue to be useful

tools for political persuasion: they are contingent historically and situa-

tionally and maintain legal validity when we deal with hegemonic institu-

tions, depending on the historical context and situation. I invoke the idea of

N A I S 5: 1 2 0 18 For Abiayala to Live, the Americas Must Die 45

This content downloaded from

128.83.214.19 on Tue, 19 Jan 2021 06:57:10 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

transhemispheric or global Indigeneity not with the intention of articulat-

ing essentialism or a generalization of our densities, but rather as a collec-

tive Indigenous proposal that originates from those experiences that unite

us. My objective is to interpellate a collectivity of Indigenous nations, as well

as non-Indigenous allies that struggle to transcend the conditions of inter-

nal/external colonialisms and their logics of elimination.

In proposing Abiayala as our locus of Indigenous transhemispheric enun-

ciation, I am fully aware of the ideological and political complications that

this also entails. Some critics will surely draw attention to linguistic barriers

and to the present contradictions in speaking of processes of decoloniza-

tion or self-determination in hegemonic languages. One of the ironies, for

example, is that the dialogue and exchange between Takir Mamani and the

Guna saylas about the Abiayala project likely happened in Spanish. Despite

taking into account the incredible weight of colonization in the hegemonic

languages, these have also facilitated dialogues and exchanges among us.

Nevertheless, while it is understandable to consider these languages and

their potential to create Indigenous bridges, we must also be aware of the

dangers in overvaluing them.

As a way of example, we can underscore certain contradictions and

limitations with regard to proposals about global Indigeneity from the

perspective of dominant languages. In his book Trans-Indigenous (2012),

Chadwick Allen reminds us several times of his interest to expand “the

archive and [explore] new methodologies for a global Indigenous literary

studies in English” (xxxii). Throughout his study, Allen constantly repeats

that his proposal is based on texts written and produced by writers “pri-

marily in English” (xi, xii–xv, xviii, xxxii, 135, etc.). Despite his valuable

contribution, Allen’s proposal, in his call for a “global Indigeneity,” obliter-

ates the contributions of activists and intellectuals from other parts of the

“globe” (particularly the south of Abiayala), even when such contributions

have been translated to English. This position becomes more evident in

his article “Decolonizing Comparison,” which complements his book. Allen

calls attention to “an impressive list of Indigenous activist-intellectuals

from around the globe” (emphasis added, 378) who have effectively artic-

ulated responses and strategies to promote the causes of Indigenous free-

dom “within, through, or beyond the ever-evolving contexts of colonialism

and imperialism” (378). In his list, he includes Taiaiake Alfred from Canada,

“Linda Tuhiwai Smith in Aotearoa New Zealand; Aileen Morton Robinson

in Australia; Noenoe Silva in Hawai’i; and Simon Ortiz, Jack Forbes, Gerald

Vizenor, Robert Warrior, Craig Womack, Jace Weaver, Jolene Rickard, and

Lisa Brooks in the United States among others” (378). I do not doubt the

valuable contributions of the activists/academics mentioned by Allen, but

46 Emil Keme NA IS 5:1 2 0 18

This content downloaded from

128.83.214.19 on Tue, 19 Jan 2021 06:57:10 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

rather his geopolitical privilege of articulating a “global Indigeneity” from

just the geographical contexts demarcated by an Anglophone colonial-

linguistic genealogy.9 Such a proposal justifies the complaints expressed by

Victoria Bomberry with regard to the development of Indigenous studies

in what is today the United States and Canada: “It seems that the devel-

opment of the field of Native American studies has suffered from a myopic

focus within U.S. national borders that denies current realities and rep-

licates colonial constructs, including the othering of Indigenous peoples

from south of the U.S.-Mexico border” (213).

Here it is important to underscore that such attitudes are not character-

istic of the Indigenous north of Abiayala. A similar “myopic focus” of Allen’s

characterizes many Indigenous positions in the south and the insistence

that Abiayala is a project that only corresponds to the geopolitical con-

text of what is today “Latin America.” Contrary to existing proposals about

global Indigeneity, which privilege exchanges primarily in English, Spanish,

French, or Portuguese, my proposal intends to operate through an epistemic

disobedience (Mignolo) that transcends the linguistic and geopolitical bor-

ders and generates alliances that lead us to constitute and materialize—like

the Zapatista slogan—a world where many worlds can fit.

Abiayala: Our Locus of Political Enunciation

This in turn leads me to ask: What does it mean to think about the world

from the plurality of our Indigenous experiences? To think from the over

one thousand Indigenous languages still spoken in our hemisphere? As

Linda Tuhiwai Smith indicates, in the twenty-first century “a new agenda

for indigenous activity [extends] . . . beyond the decolonization aspirations

of a particular indigenous community [and moves] . . . towards the devel-

opment of global ‘indigenous strategic alliances’” (108). Indeed, we are at a

moment when we need to learn from each other as Indigenous peoples and

share our stories and experiences among ourselves and with others in order

to disclose our similarities and differences in terms of languages, cultures,

ideologies, politics . . . We are at a moment where many of our histories and

struggles are becoming more and more visible, affording us opportunities

to develop new and fresh alliances and exchanges where we can develop

agendas against economic, political, and cultural oppressions that have kept

us in conditions of subalternity.

Some will say that an obvious problem is the lack of multilingual episte-

mological exchanges. Very few works of Indigenous intellectuals and activ-

ists from northern Abia Yala have been translated into Spanish and Portu-

guese.10 Although still limited, a better job has been done translating and

N A I S 5: 1 2 0 18 For Abiayala to Live, the Americas Must Die 47

This content downloaded from

128.83.214.19 on Tue, 19 Jan 2021 06:57:10 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

publishing texts from southern Abia Yala into English.11 In spite of these lim-

itations, important conversations have been generated about global Indi-

geneity with academic publications such as Indigenous Experience Today

(edited by Orin Starn and Marisol de la Cadena, 2009), Indigenous Peoples

and Autonomy (edited by Mario Blaser and others), Decolonizing Native His-

tories (edited by Florencia Mallon, 2012), Comparative Indigeneities of the

Americas (edited by Bianet Castellanos and Lourdes Gutierrez), Indigeneity

(edited by Guillermo Delgado and John Brown, 2012), The World of Indige-

nous North America (edited by Robert Warrior, 2014), The Oxford Handbook

of Indigenous American Literature (edited by Daniel Heath Justice and James

Cox, 2014), The Five Cardinal Points in Contemporary Indigenous Literature

(edited by Gloria Chacon et al., 2015). Ironically, perhaps, it has been social

networks such as Facebook that have also enabled a valuable exchange of

dialogues and knowledges through the constant dissemination of articles

and books in PDF, facilitating access to many Indigenous works and in some

cases eliminating the high cost to obtain them in print.

Nevertheless, while it is important to celebrate these steps toward the

creation of transhemispheric Indigenous bridges, we must not forget the

fact that more than a thousand Indigenous languages survive in our hemi-

sphere and that it is essential to generate support for the survival and revi-

talization of these languages. This must be one of our priorities.

This brings me to the project of Abiayala. A lot of you may be wonder-

ing: Why this particular category and not another one, like Turtle Island,

Anahuac, Tawantinsuyu, or Pindorama?12 As far as I know, while these cat-

egories evoke narratives of the creation of humanity and the world similar

to that of Abiayala, their uses in contemporary Indigenous societies have

been associated in relation to certain Indigenous geopolitical territories and

peoples, much of the time following and legitimizing the divisions that we

have inherited from Spanish, Portuguese, British, French, and Dutch colo-

nialisms. That is, Turtle Island usually refers to Indigenous peoples and

territories in the “North,” particularly those where the British marked and

divided Indigenous territories and where English has become the adopted

language of many Native Americans. Similarly, Tawantinsuyu refers mostly

to the Andean region, particularly the territories and peoples associated

with the Inca and Aymara Empires, which were later colonized by the Span-

ish. Abiayala, contrary to these assumptions, has been consciously and

politically articulated as a broader geopolitical locus of enunciation with

clear transnational claims. Its epistemological articulation emerges against

ideas of (Latin) America in order to counteract their colonial legacies and

recover the hemisphere for Indigenous peoples. Abiayala offers us the pos-

sibility to articulate a collective locus of enunciation that goes beyond the

48 Emil Keme NA IS 5:1 2 0 18

This content downloaded from

128.83.214.19 on Tue, 19 Jan 2021 06:57:10 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

borders imposed on us by Europeans and their descendants, the possibility

to rethink and recover the world from our own epistemological millenar-

ian legacies. Do we need to underscore how we as Indigenous peoples have

lived in the hemisphere way before settlers and their descendants forged

the ideas of “(Latin) America,” “Hispanic America,” “Iberian America,” “West

Indies”? Our necessity to rethink our hemisphere from Abiayala is urgent.

As far as I know, there is no other Indigenous nation that identifies and

imagines a name for our hemisphere as an Indigenous collective project.

To be clear, when I speak of Abiayala, I am not proposing the cancella-

tion or omission of categories like Turtle Island, Tawantinsuyu, Anahuac,

Pindorama, or any other used and recognized by an Indigenous nation in

the continent. Instead, I am proposing to reconfigure the map of our hemi-

sphere according to the names and parameters employed by our ancestors

and descendants. Abiayala could be the Indigenous name of our hemisphere,

and then we should activate other Indigenous categories within Abiayala.

Besides continuing to affirm the categories of Turtle Island, Mayab’, Pin-

dorama, Anahuac, and Tawantinsuyu, we should recover and affirm many

other ones, such as Wallmapu the name that the Mapuche Nation uses to

refer to the Araucanía Region in what is today Chile and Argentina, or Gua-

jira, the category that the Wayuu Nation employs to refer to the coastal

regions of what is today Colombia and Venezuela. We could restitute the

Indigenous name Guanahani to rename San Salvador in the Bahamas, and in

that way we can reactivate the memory of the Lucaya Indians in the Carib-

bean. As we know, that memory was trampled by Christopher Columbus

during the so-called discovery of the New World.13

Now these struggles to revive and recover the ancestral names of our

territories are nothing new. They have even culminated in successful cam-

paigns to assert our historical memory. Since 1975 the Koyukon people,

members of the Athabasca Nation in what is now Alaska, United States,

petitioned the U.S. federal government to change the name of the highest

mountain in northern Abiayala. The federal government in 1917 had offi-

cially named the mountain McKinley to honor American president William

McKinley (1897–1901). The Indigenous settlers, however, long before 1917,

recognized the mountain as Denali or Deenaalee (“the highest” in the Koyu-

kon language). On his visit to Alaska in September 2015, President Barack

Obama finally acknowledged the demands of the Koyukon nation and the

state of Alaska to reclaim and rename the mountain as Denali.

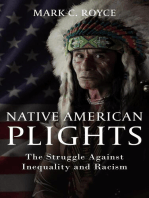

Efforts to recover the Indigenous names of our territories also charac-

terize the valuable work of cartographer Aaron Carapella, who for more

than fifteen years has worked to reconfigure the map of our hemisphere

with thousands of Indigenous names. His map, Tribal Nations of the Western

N A I S 5: 1 2 0 18 For Abiayala to Live, the Americas Must Die 49

This content downloaded from

128.83.214.19 on Tue, 19 Jan 2021 06:57:10 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

Hemisphere, is an essential contribution to rethinking our continent from

our ancestors’ memory (Figure 1). According to Carapella, the map contains

the names of approximately three thousand Indigenous nations throughout

our hemisphere’s geography and is to date the most complete map of names

originating in our territories before and after the arrival of Europeans.

Carapella indicates that the map is a “visual reminder of who called this land

home for tens of thousands of years before any European set foot, creating

a sense of pride for modern-day Native Americans as well as educating the

non-Native public. To Native Americans, this land will always be our ances-

tral homeland.”

Although Abiayala and other Indigenous names within our continent

are not yet well-known concepts among people in faraway communities,

it is a question of working so that the wings of these projects gradually

reach a multiplicity of spaces in order to stimulate and dignify our ances-

tral memory. Let this be the first step in the creation of a global Indigenous

and non-Indigenous movement against predatory neoliberalism. Let these,

among others, be the plural principles that guide our paths toward our col-

lective strengthening.

I also understand that some readers will think that in proposing Abiayala

as our locus of enunciation I am proposing a civilizing project that brings

the danger of recycling a “reverse racism,” or the same colonial logics that

the European invaders and their descendants have bequeathed to us. First,

the development and assertion of a collective cultural and political Indige-

nous consciousness is not the same as racism. As I mentioned earlier, we are

colonized subjects, and every day both the nation-state and its hegemonic

institutions exhort and teach us to hate ourselves, to internalize ideas of

white and criollo-mestizo supremacy regarding ideas of beauty, religion, his-

tory, and so on. Hence the urgent need to dignify our cultures through our

own civilizing project that emanates from our over-one-thousand-year-old

histories and our ancestral values.

In second place, when I say this, I don’t pretend to obscure the complex

hegemonic narratives nor our human experiences. I am fully conscious

about how alliances to certain Indigenous sectors and not others may gen-

erate profound tensions. This is exemplified by the Evo Morales government

in Bolivia, which in 2011 approved the construction of a highway that would

run through the Parque Nacional y Territorio Indígena y Parque Nacional

Isiboro Sécure, or Isiboro Sécure National Park and Indigenous Territory

(TIPNIS). This territory, which encompasses 1.2 million hectares of land, is

inhabited by Amazonian Indigenous nations like the Mojeños-Trinitarios,

Chimanes, and Yuracarés in the North and by Quechua and Aymaras in the

South. The latter are called colonizadores (colonizers), since they migrated

50 Emil Keme NA IS 5:1 2 0 18

This content downloaded from

128.83.214.19 on Tue, 19 Jan 2021 06:57:10 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

to and established themselves in the region in the 1970s. Besides, these

Indigenous sectors in the south of the TIPNIS represent Morales’s constit-

uency and supported the construction of the highway, given that it would

facilitate transporting their merchandise. The approval of this “modern”

project generated the resistance of the Amazonian populations in the north

who argued that the highway would bring serious ecological consequences

to the region, including the displacement of various populations from their

ancestral lands. Morales’s decision to build the highway led to a sixty-five-

day march in August 2011 by Amazonian Indigenous nations to La Paz to pro-

test the project. Initially, the marches were denounced by the government

as an “imperialist conspiracy” and were violently repressed in September

2011 (Webber). Morales insisted that “the road was needed to bring eco-

nomic development to poor [Amazonian] indigenous communities” (Frantz).

However, as the protests grew to the point of acquiring national and inter-

national attention, Morales gave in to the demands and in December of the

same year signed the untouchable law (ley intangible), which states that

the national park cannot be exploited by commercial enterprises. The deci-

sion, however, led to new protests by Indigenous sectors that had supported

Morales’s initial decision and represented his constituency, like the Consejo

Indígena del Sur (Indigenous Council of the South [CONISUR]), residents of

Cochabamba and San Ignacio de Moxos, and Cocaleros (Frantz). The con-

flict showed the tensions between the various Indigenous peoples and, at

the same time, some of the contradictions of Morales’s socialist and sover-

eign agenda. The debate continues today as to whether or not moderniza-

tion projects based on extractivism are the most adequate to respond to the

necessities of Indigenous peoples.

Contradictions and tensions between Indigenous sectors such as those

that have occurred in Bolivia characterize many of our experiences at the

communal, national, and transnational levels. These contradictions and

tensions are also not at all new and certainly precede the European inva-

sions of our territories; they are a part of our complex human experience,

which, as I have suggested above, has on many occasions been obliterated

by both the hegemonic discourses elaborated by the European invaders and

their descendants, as well as by our allies and even by ourselves.

By calling attention to these complexities, my purpose is to make them

visible. It is a matter of showing that carrying out the Abiayala project brings

with it many challenges within and outside the academic field. Is it impossi-

ble to transcend them? I do not think so. Rather, we must deepen the exist-

ing dialogues and exchanges inside and outside institutional spaces. Inter-

national meetings such as those sponsored by the United Nations General

Assembly, which in 2014 held the World Conference on Indigenous Peoples,

N A I S 5: 1 2 0 18 For Abiayala to Live, the Americas Must Die 51

This content downloaded from

128.83.214.19 on Tue, 19 Jan 2021 06:57:10 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

have been important. At the organizational level, we can also mention the

work of the International Indian Treaty Council (IITC) and the World Council

of Indigenous Peoples (WCIP). Academic conferences include the Interna-

tional Congress: Indigenous Peoples of Latin America (CIPIAL); the Native

American and Indigenous Studies Association (NAISA), which has approved

the creation of the Abiayala Working Group; and the Latin American Studies

Association (LASA) and its Ethnicity, Race, and Indigenous Peoples (ERIP)

and Otros Saberes / Other Knowledges sections; among several others.14

These spaces have been important for exchanges of ideas and knowledge,

which in some cases have permitted us to transcend linguistic barriers in

the formulation of policies that allow us to imagine the potential of a trans

hemispheric Abiayala project.

Along with these exchanges, it is also necessary to champion perma-

nent criticism of all those positions that threaten our efforts to recover and

defend our ancestral territories and to dignify and restore our Indigenous

life. I believe that we must develop categories of analysis that do not lose

sight of the materiality of our experiences in economics, society, culture,

linguistics, gender, and so on. Similarly, we must continue to revitalize the

emancipatory principles of our peoples, that is, to start from our own cos-

mogonies and those forms of social cohesion that have been the cornerstone

of our survival. In these steps we must follow and discuss the proposals of

Indigenous women and men who today, as in the past, are guiding the paths

of our emancipation. Suffice it to mention here Zapatismo in what is now

Chiapas, Mexico, the Water Protectors in Standing Rock, North Dakota, and

Idle No More in what is now Canada. May these movements, and those Indig-

enous and non-Indigenous women and men who struggle to defend Mother

Earth, be our point of departure in our efforts to restore our memory and

our organic relationship with our territories. It is therefore a matter of con-

tinuing to generate collective consensus that shows our historical opposi-

tion to the deplorable mercantilist and ethnocentric economic principles

that have kept us in conditions of subalternity.

Here I should also underscore that by proposing Abiayala as our locus of

political enunciation I am not suggesting a civilizational project that is exclu-

sive to Indigenous peoples. In our movement toward emancipation, there

have been many non-Indigenous sisters and brothers who have walked with

us and at times have even sacrificed much more than we have. As Leanne

Simpson states, “Every hard-fought victory has been a direct result of the

alliances and relationships of solidarity we have forged, maintained, and

nurtured with supporting Indigenous nations, environmental networks,

and social justice organizations” like church groups and human rights activ-

ists who “have stood alongside us as allies and as friends, often juggling a

52 Emil Keme NA IS 5:1 2 0 18

This content downloaded from

128.83.214.19 on Tue, 19 Jan 2021 06:57:10 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

variety of roles and responsibilities, always under very challenging circum-

stances” (xiii).

We cannot overlook the force, resonance, and potential that the project

of Abiayala has among Indigenous and non-Indigenous activists and aca-

demics. This allows us to take advantage of an important opportunity in the

articulation of a civilizational Indigenous politics urgently needed in a new

epoch of challenges for Indigenous nations in our hemisphere and in other

parts of the planet.

The Americas Must Die

When I propose an epistemological and geopolitical resignification of our

hemisphere from the perspective of Abiayala, I should also clarify that I am

not proposing a cancellation of the ideas of “America” and “Latin America.”

Instead, I am proposing the end of our affective and political affiliation to

these categories as Indigenous peoples. Given that we have a very strong

cultural capital, it is our duty to unearth and affirm our own points of mil-

lenarian references in order to recognize ourselves in our own hemisphere.

Besides, ideas like “(Latin) America” for us represent Eurocentric projects

that consciously or unconsciously justify our exclusion and colonization.

From such exclusions, marginalization, and colonization emanates Abiayala

as our own cultural and civilizational project.

Indeed, following Kichwa scholar Armando Muyolema’s theorization of

the concept, Abiayala is a term that challenges the idea of Latin America, or

the “Americas,” because these projects continue to be constitutive of eth-

nocentric and colonialist logics. They endorse and affirm the aspirations

and geopolitical projects of the white and criollo-mestizo populations. While

many “modern” nation-states have “officialized” Indigenous languages,

such languages and cultures have not acquired national status; that is, they

are not part of educational curricula accessible to all peoples within “mod-

ern” nation-states. On the other hand, the idea of citizenship endorsed by

the state through narratives of mestizaje or “blood quantum” only aims to

erase our millenarian origins.

For example, recognizing the oppressive dimension of these hegemonic

narratives has led many Indigenous activists and intellectuals to deny

them. In her study Hawaiian Blood (2008), J. Kêhaulani Kauanui develops

a rigorous critique of blood quantum policies in Hawai’i. Such policies have

historically served those in power to develop strategies to undermine not

only Kanaka Maoli identity but also fuel their land dispossession. This pol-

icy, which was introduced in the island in 1920, has culturally and politi-

cally operated through a reductive logic, destabilizing notions of Indigenous

N A I S 5: 1 2 0 18 For Abiayala to Live, the Americas Must Die 53

This content downloaded from

128.83.214.19 on Tue, 19 Jan 2021 06:57:10 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

identity based on genealogy. According to Kauanui, the policy of classifi-

cation based on “blood quantum is a colonial project in the service of land

alienation and dispossession. Blood quantum classification does not allow

for the building of Kanaka Maoli political power because it is ultimately

about exclusion, while it also reduces Hawaiians to a racial minority rather

than an indigenous people with national sovereignty claims” (10). Similar to

the blood quantum policies, mestizaje has been employed to justify projects

of deindianization and territorial dispossession. Mestizaje is the category

that many people use in Latin America to deny their Indigeneity and affirm

a criollo-mestizo racial/ethnic and economic status. Because of this, many

Indigenous activists and scholars reject mestizaje. In his Revolución india,

Aymara intellectual Fausto Reinaga states: “I am not a mestizo writer or

man of letters. I am an Indian. An Indian who thinks, who develops ideas,

who creates ideas. My ambition is to forge an Indian ideology, an ideology

of my people” (60, my translation). Similarly, Kaqchikel Maya writer Luis

de Lión states: “I cannot participate in the so-called mestizaje because His-

panism is precisely the negation of my language, of my culture” (cited in

Montenegro, 8, my translation). More recently, members of the Nican Tlaca

(“we the people here” in Nahuatl) movement in California have developed

a campaign to reject categories like “Hispanic,” “Latina/o,” and “American”

and to recover their Indigenous heritage. They have developed posters and

several videos on YouTube to justify their claim to Indigeneity (Figure 2).15

They state: “We must reconstruct our Anahuac nation in order to be liber-

ated from the European occupation under which we are enslaved. We must

declare ourselves as the Nican Tlaca race, using Mexica civilization, and the

Anahuac nation as points of unity and points of liberation.”

Ideas like “America” and “Latin America,” for example, were conceived as

projects that sharply excluded us from their civilizational and political ide-

als. As is known, the name of “America” began to acquire hegemonic promi-

nence in what is today the United States toward the end of the seventeenth

century. The British used to refer to the “Indians” and settlers as “Ameri-

cans” in a pejorative manner. From here, settlers who sought independence

from the British began to embrace and adopt the concept in a positive way

to counteract British citizenship. In his farewell address in 1797, George

Washington publicly claimed that “The name of AMERICAN, which belongs

to you, in your national capacity, must always exalt the just pride of Patri-

otism, more than any appellation derived from local discriminations.” John

Adams continued with similar affirmations to those of Washington in March

of the following year in his inaugural discourse as U.S. president. Interpel-

lating the “American People,” he exhorted settlers to adopt and embrace the

term positively.

54 Emil Keme NA IS 5:1 2 0 18

This content downloaded from

128.83.214.19 on Tue, 19 Jan 2021 06:57:10 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

With the adoption of the politics of “manifest destiny” by the United

States at the beginning of the nineteenth century, particularly with the Mexi-

can-American War (1845–48), the idea of “Americanism” and the concept of

“America” entered in a deep tension. According to Arturo Ardao (1981), the

idea of Latin America emerges as a direct response to the growing imperial-

ist aspirations of the “Anglo-Saxon America” or the United States in “Span-

ish America” and the Caribbean. The name was first proposed by Colombian

intellectual José María Caicedo in his poem “Las dos Américas” (The two

Americas), published in 1856. Caicedo states in one of the verses: “La raza

de la América latina al frente tiene la raza sajona” (The Latin American race

has in front of him the Anglo-Saxon race). Caicedo was obviously responding

to the Mexican-American War, during which Mexico lost half of its territory

to the United States. This defeat obviously developed a lot of anxieties—and

rightly so!—among criollo-mestizo intellectuals regarding U.S. imperialist

expansion in the region.16 Caicedo would later obtain a post as ambassador

of Spanish American affairs in Paris. From there, he would write various

articles in which he sought to establish a conciliatory discourse that implic-

itly addressed European colonialisms in various parts of the hemisphere. In

one of his articles, he once again evoked the idea of “Latin America”:

Since 1851 we have started to give Spanish America the denomination of Lat-

in; and this innocent move has brought the anathema of various newspapers

in Puerto Rico and Madrid. It has been said of us: “Because you hate Spain you

unchristen America.” “No,” we responded. “I have never hated a single people,

nor am I one of those that curses Spain in Spanish.” There is an Anglo-Saxon,

Danish, Dutch America, etc.; there is also a Spanish, French, and Portuguese

America; and for this latter group, shouldn’t the scientific denomination be

Latin? Of course, we Spanish Americans are Latin not because of our Indian

heritage but rather because of our Spanish one. (Ardao, 74, emphasis added)

As we can see, the cultural and civilizational project imagined by Caicedo

sharply excludes the “Indians.” The adjective “Latin” is directly associated

with Europe and not Indigenous peoples.

In this sense, “Latin America,” “America,” and the “Americas” are not

just the names of specific territories imagined by settlers. These concepts

also embody the enduring historical and cultural regimes of colonialisms

throughout the hemisphere. Such categories have historically denied us the

right to name our own lands and our own experiences and have entailed—in

the name of white-criollo-mestizo projects—the suppression and margin-

alization of Indigenous languages and ways of thinking and being on the

assumption that Indigenous lives and cultures are “savage,” “barbarous,”

“backward,” or “uncivilized.” We as Indigenous peoples can only be a part

of Latin America or America if we give up our lands, languages, and cultural

N A I S 5: 1 2 0 18 For Abiayala to Live, the Americas Must Die 55

This content downloaded from

128.83.214.19 on Tue, 19 Jan 2021 06:57:10 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

and religious specificities. Contrary to this civilizational project, which

maintains us as slaves in our own lands, Abiayala represents our own polit-

ical project and locus of enunciation.

Indeed, it is important to underscore here that these claims about the

marginalization of Indigenous Nations are not “things from the past” or

things that have been “resolved” by (Latin) American nation-states through

the adoption of “multicultural” or “intercultural” agendas. On the con-

trary, racism, xenophobia, heteronormative politics, and class oppressions

maintain their force and continue to define our experiences globally. It is

enough to just look at our contemporary experiences in order to confirm my

assumptions with regard to our tense relationships with “modern” nation-

states and their hegemonic institutions. For them, those of us who resist

extractivist economic policies continue to be viewed as a “problem” or a

threat to their status quo.

In what is today Chile, the presidents Michelle Bachelet and Sebastina

Piñera have used the antiterrorist law established by General Augusto

Pinochet in 1984 to justify the incarceration and assassination of Mapuche

activists in the southern region of the Araucanía.17 In Totonicapan, Guate-

mala, in early 2012 the Guatemalan army repressed a peaceful protest led

by K’iche’ Maya peoples who demanded that the government not increase

the cost of electricity, not privatize education, and not give more constitu-

tional power to the Guatemalan army. The military response included the

brutal assassination of eight people and the wounding of thirty-five oth-

ers.18 In December of the same year, Saskatchewan, Canada, witnessed the

emergence of the Idle No More movement, which challenged the laws of the

Canadian nation-state to approve the extraction of resources in the territo-

ries of the First Nations. The approval of these laws was made without con-

sulting Indigenous leaders, which was interpreted as an effort of the Cana-

dian government to reduce the rights to sovereignty of the First Nations.19

In Peru in 2009 President Alan García, with the desire to implement neolib-

eral extractivist policies in the Amazonian region, sent the National Guard

to invade Indigenous territories. The Amazonian resistance, similar to the

K’iche’ protest, was met with gunshots from the Peruvian army. García jus-

tified his actions in the following way: “These people don’t have crowns.

They aren’t first-class citizens. What can 400,000 natives tell 28 million

Peruvians? You [the government] don’t have the right to be here? No way!

That is a big mistake, and whoever thinks this way is leading us to irratio-

nality and to a backward primitivism” (in Bebbington, 288, my translation).

Around the corner from Peru, in the southern Amazonian region of what is

today Ecuador, the Shuar peoples in the Condor mountain ranges defend

their territories and resources against the invasion of the Chinese mining

56 Emil Keme NA IS 5:1 2 0 18

This content downloaded from

128.83.214.19 on Tue, 19 Jan 2021 06:57:10 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

company Explorcobres S.A., which aims to exploit the tin underneath the

Shuar’s lands. The Ecuadorian government, which approved the operations

of this mining company, has declared a “state of exception” in the region,

restricting not only the rights of Indigenous communities but also the

demobilization of Acción Ecológica, or Ecological Action, an organization

that has been denouncing attacks against the Shuar population.20 On Sep-

tember 26, 2014, forty-three male Indigenous students from the teachers’

college of Ayotzinapa headed to Guerrero, Mexico, to protest Mayor José

Luis Abarca’s approval and signing of a law to raise the price of tuition for

higher education in the state. On the way to their destination, the students

were intercepted by the local police and handed over to a group of s icarios,

or “hitmen,” who kidnapped them. Their parents are still looking for them

with the hope that they are alive. In March 2016 the Lenca leaders Berta

Caceres and Nelson García, members of the Civic Council of Popular and

Indigenous Organizations of Honduras (COPINH), were assassinated in

what is today Honduras for their efforts to defend their territories against

the hydroelectric company Desarrollos Energéticos (DESA). This company

had obtained the approval and support of the Honduran government to

exploit the water in Lenca territories. They have also claimed that key

documents that denounced the assassination of Caceres and García have

been displaced.21 Since the first of April 2016 the Sioux Nation in North

Dakota, along other Indigenous nations in Turtle Island, have protested and

resisted the construction of an oil pipeline that would cross the Missouri

river—sacred Indigenous territory—and that would cause immeasurable

ecological damage. This resistance, until now, has resulted in attacks and

imprisonment of various “water protectors” and non-Indigenous leaders

fighting for their rights to the sovereignty of the Indigenous nations in

what is today the United States . . .

I can keep giving examples—all day!—showing the constant tensions

and confrontations we continue to have with “modern” nation-states.

These struggles, which did not start recently but rather in October 1492,22

signal that our liberation entails not just dismantling today’s mercantilist

system, which is based on predatory extractivism, but also the destruction

of all those systems that prevent us from expressing ourselves in our Indig-

enous languages and impede the rights of Indigenous women or Indigenous

gays or transsexuals. It entails establishing an Abiayala that recognizes,

accepts, and respects our differences and at the same time asserts a project

of shared Indigenous demands. We would do well to begin by reviving for

our times the proposal of the Cuban writer José Martí, that the history of

Abiayala—of the Incas, Mayas, Nahuas, Navajo, Cherokee, Inuit—up to the

present should be learned inside out, even if we do not learn the history of

N A I S 5: 1 2 0 18 For Abiayala to Live, the Americas Must Die 57

This content downloaded from

128.83.214.19 on Tue, 19 Jan 2021 06:57:10 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

the archons of Greece. Our Greeces are much more preferable to Greeces

that are not ours. We need them most. Let the world be grafted onto our

Indigenous nations, but let the trunk be that of our over-one-thousand-

year-old nations. And let the defeated pedant be silent, for there is no place

where we can feel more pride than in our oppressed Indigenous republics

of Abiayala.23

It is, then, a question of opening the cage in which the invaders placed us

and of listening to the plurality of histories that characterize our peoples,

to break all those exploitative chains that colonialism has imposed on us.

Let us develop processes of relearning to revive our memories and nourish

ourselves with old and current knowledges; let us learn non-Indigenous his-

tories and knowledges as long as these are dissident tools that guide us in

producing categories that help us bring our emancipatory goals to f ruition.

Therefore, for us to recognize and endorse categories like America or Latin

America would contribute to affirming a colonialist logic that overlooks our

needs as Indigenous nations. In particular, our continued efforts to recover

and defend our territories and restitute our linguistic, cultural, and religious

specificities, efforts that Latinamericanism and Americanism in general, in

all of its forms, have failed to deeply address and understand. For these rea-

sons, I would venture to say that the efforts of subaltern-popular Indige-

nous rights movements should be invested in first d eveloping—through the

idea and civilizational project of Abiayala—an Indigenous and even global

historical bloc that, while it addresses internal and external oppressions,

also manages to bring us together as diverse Indigenous nations struggling

to overcome external and internal/settler colonialisms and their logics of

elimination. By positioning ourselves as Indigenous subjects, we can not

only enable the hegemonic articulation of our demands but also negotiate

with non-Indigenous others to secure the constitution of multicultural or

intercultural national and international models based on our own Indige-

nous needs and perspectives.

To conclude, like the Guna Nation and Takir Mamani, I encourage you

to consider and adopt the idea and civilizational project of Abiayala as a

transhemispheric Indigenous category that challenges the Eurocentrism of

(Latin) America, to inscribe it in your official declarations, political mani-

festos, scholarly articles, books, films, and so on. In this way, Abiayala can

become our category, our own locus of political enunciation that can lead

us to restitute our Indigenous life and that of our Mother Earth. At the

same time, it is about not just the vindication of our ancestral categories

and the names of our territories but also our efforts to recover them and

defend them. Indeed, the struggle of Abiayala is a struggle for our territo-

ries, for the richness of our lands, for our rights to our ways of life. These

58 Emil Keme NA IS 5:1 2 0 18

This content downloaded from

128.83.214.19 on Tue, 19 Jan 2021 06:57:10 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

are economic, political, and geocultural struggles that we fight collectively.

Let’s take Abiayala as a point of departure to think of better modes of inter/

multicultural sociability that consequently lead us to materialize, like the

Zapatista slogan, a world where many worlds can fit.

EMIL KEME (aka Emilio del Valle Escalante) is a K’iche’ Maya activist/scholar

from Iximulew (Guatemala). He is an associate professor of Spanish at

the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill.

Bibliography

Aguilar, Daniel. “Ecuador: Tensión en la Amazonía por conflicto entre minera

china y comunidad Shuar.” Mongabay, January 17, 2017. https://es.mongabay

.com/2017/01/ecuador-tension-la-amazonia-conflicto-minera-china

-comunidad-shuar/.

Allen, Chadwick. “Decolonizing Comparison: Toward a Trans-Indigenous Lit-

erary Studies.” In The Oxford Handbook of Indigenous American Literature,

edited by James Cox and Daniel Heath Justice, 377–94. Oxford: Oxford Uni-

versity Press, 2014.

———. Trans-Indigenous: Methodologies for Global Native Literary Studies. Min-

neapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 2012.

———. “2014 NAISA Presidential Address: Centering the ‘I’ in NAISA.” Native

American and Indigenous Studies 2, no. 1 (Spring 2015): 1–14.

Andersen, Chris. “Critical Indigenous Studies: From Difference to Density.” Cul-

tural Studies Review 15, no. 2 (2009): 80–100.

Ardao, Arturo. Génesis de la idea y el nombre de América Latina. Caracas, Vene-

zuela: Centro de Estudios Latinoamericanos Rómulo Gallegos, 1980.

“Asesinan a Lesbia Yaneth: Compañera de Berta Cáceres.” El diario, July 7, 2016.

http://www.eldiario.es/desalambre/Asesinan-Lesbia-Yanet-Berta-Caceres

_0_534746902.html.

Bebbington, Anthony. “La nueva extracción: ¿Se re-escribe la ecología política

de los Andes?” Umbrales 20 (2010): 285–305.

Berkhofer, Robert. The White Man’s Indian: Images of the American Continent

from Columbus to the Present. New York: Vintage Books, 1979.

Blaser, Mario, Revi de Costa, Deborah McGregor, and William Coleman, eds. In-

digenous Peoples and Autonomy: Insights for a Global Age. Vancouver: UBC

Press, 2010.

Bomberry, Victoria. “The Struggle for Indigenous Autonomy in Twentieth-First-

Century Bolivia.” In Comparative Indigeneities of the Américas: Toward a

Hemispheric Approach, edited by Bianet Castellanos, Lourdes Gutierrez, and

Arturo Aldama, 213–26. Tucson: University of Arizona Press, 2012.

Bonfil Batalla, Guillermo. “El concepto de Indio en América: Una categoría colo-

nial.” Anales de la antropología 9 (1972): 106–24.

Cadena, Marisol de, and Orin Starn. Indigenous Experience Today. Oxford: Berg,

2007.

N A I S 5: 1 2 0 18 For Abiayala to Live, the Americas Must Die 59

This content downloaded from

128.83.214.19 on Tue, 19 Jan 2021 06:57:10 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

Calfunao Paillalef, Juana. “Al presidente chileno Sebastian Piñera: Carta abier-

ta de Lonko Juana Calfunao.” Centro de documentación mapuche, January 8,

2013. http://www.mapuche.info/?kat=3&sida=3903.

Carapella, Aaron. Tribal Nations of the Western Hemisphere. Map. Tribal Na-

tions Maps, 2016. http://www.tribalnationsmaps.com/.

Castellanos, Bianet, Lourdes Gutierrez, and Arturo Aldama, eds. Comparative

Indigeneities of the Américas: Toward a Hemispheric Approach. Tucson: Uni-

versity of Arizona Press, 2012.

Chacon, Gloria, and Juan Sánchez. “Los cinco puntos cardinales en la literatu-

ra indígena contemporánea.” Special issue of Diálogos: An Interdisciplinary

Studies Journal 19, no. 2 (2016).

Christenson, Allen. The Popol Vuh: The Sacred Book of the Maya. Oklahoma: Uni-

versity of Oklahoma Press, 2007.

Colón, Cristóbal. Diario del primer viaje de Colón. Edited by Antonio Vilanova.

Barcelona: Ediciones Nauta, 1965.

Congreso General Guna. 2015. http://www.gunayala.org.pa/.

Coulthard, Glenn S. Red Skin, White Masks: Rejecting the Colonial Politics of

Recognition. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 2014.

“Declaración de Quito.” In Encuentro continental de pueblos indígenas, 89–136.

Quito, Ecuador, 1990.

Delgado, Guillermo, and John Brown Childs. Indigeneity: Collected Essays. Santa

Cruz, CA: New Pacific Press, 2012.

Deloria, Vine, Jr. Custer Died for Your Sins: An Indian Manifesto. Norman: Uni-

versity of Oklahoma Press, 1969. (Spanish edition, El general Custer murio

por vuestros pecados [Barcelona: Barral, 1975].)

Dennison, Jean. Colonial Entanglement: Constituting a Twenty-First-Century

Osage Nation. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2012.

Ethnologue: Languages of the World. https://www.ethnologue.com/region

/Americas.

Frantz, Courtney. “The TIPNIS Affair: Indigenous Conflicts and the Limits on

‘Pink Tide’ States under Capitalist Realities.” Council on Hemispheric Af-

fairs, December 16, 2011. http://www.coha.org/the-tipnis-affair-indigenous

-conflicts- and-the-limits-on-pink-tide-states-under-capitalist-realities/.

Heath Justice, Daniel, and James Cox. The Oxford Handbook of Indigenous

American Literature. New York: Oxford University Press, 2014.

Hernández, Oswaldo. “Totonicapán, todos los ausentes.” Plaza pública, Septem-

ber 10, 2012. https://www.plazapublica.com.gt/content/totonicapan-todos

-los-ausentes.

Hewitt, John Napoleon Brinton. Iroquian Cosmology. New York: AMS Press,

1974.

Idle No More! 2015. http://www.idlenomore.ca/.

Kauanui, J. Kēhaulani. Hawaiian Blood: Colonialism and the Politics of Sover-

eignty and Indigeneity. Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 2008.

Linconao, Francisca. “Carta de la machi Francisca Linconao a Presidenta

Bachelet.” Mapuexpress, April 2016. http://www.mapuexpress.org/?p=8239.

Lión, Luis. Time Commences in Xibalba. Tucson: University of Arizona Press, 2012.

60 Emil Keme NA IS 5:1 2 0 18

This content downloaded from

128.83.214.19 on Tue, 19 Jan 2021 06:57:10 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

Mallon, Florencia, ed. Decolonizing Native Histories: Collaboration, Knowledge,

and Language in the Americas. Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 2012.

Martí, José. Nuestra América. Ayacucho, Venezuela: Biblioteca Ayacucho,

2005.

Maxwell, Judith, and Robert Hill. Kaqchikel Chronicles: The Definitive Edition.

Austin: University of Texas Press, 2006.

Means, Russell. “Para que América viva, Europa debe morir.” En “Artesania

nativa. Blog: Lakotaes.” 2008. http://lakotaes.skyrock.com/1931687975

-Discurso-de-Rusell-Means.html.

Mignolo, Walter D. “Epistemic Disobedience, Independent Thought and Decolo-

nial Freedom.” Theory, Culture & Society 26, nos. 7–8 (2009): 159–81.

Momaday, N. Scott. House Made of Dawn. New York: Harper Perennial, 2010.

(Spanish edition, La casa hecha del alba [Appaloosa, 2011].)

Montenegro, Gustavo Adolfo. “Luis de Lión: ‘Yo siempre tuve un cielo.’” Prensa

libre: Revista domingo, May 9, 2004, 8–11.

Moonen, Francisco. Pindorama conquistada: Repensando a questão indígena no

Brasil. Curitiba, Brazil: Editora Alternativa, 1983.

Muyolema, Armando. “De la ‘cuestión indígena’ a lo ‘indígena’ como cuestion-

amiento: Hacia una crítica del latinoamericanismo, el indigenismo y el mes-

tiz(o)aje.” In Convergencia de tiempos: Estudios subalternos / contextos lati-

noamericanos estado, cultura, subalternidad, edited by Ileana Rodríguez,

327–63. Amsterdam: Rodopi, 2001.

Nakata, Martín. Disciplinar a los salvajes: Violentar las disciplinas. Quito, Ecua-

dor: Abya Yala, 2014.

Pereiro, Xerardo, Cebaldo de León, Mónica Martínez Mauri, Jorge Ventocilla,

and Yadixa del Valle. Los turistores Kunas: Antropología del turismo étnico

en Panamá. Palma, Spain: Universitat de les Illes Balears, 2012.

Quillaguamán Sánchez, Eduardo. “El Abya Yala.” La patria: Periódico de circu-

lación nacional (Bolivia), April 3, 2015, 3. http://www.lapatriaenlinea.com/.

Reinaga, Fausto. “La revolución India.” In Utopía y revolución: El pensamiento

político contemporáneo de los Indios en América Latina, edited by Guillermo

Bonfil Batalla. Mexico City: Editorial Nueva Imagen, 1981.

Reynaga, Ramiro. Tawantinsuyu: Cinco siglos de guerra queswaymara contra

España. La Paz, Bolivia: Centro de Coordinación y Promoción Campesina

Mink’a, La Paz, 1978.

Salomon, Frank, and George Urioste, eds. Huarochiri Manuscript. Austin: Uni-

versity of Texas Press, 1991.

Schertow, John A. “Indigenous Struggles 2012: Dispatches from the Fourth

World.” Intercontinental Cry: A Publication of the Center for World Indig-

enous Studies. https://intercontinentalcry.org/publications/indigenous

-struggles-2012/.

Sevcenko, Nicolau. Pindorama revisitada: Cultura e sociedade em tempos de

virada. São Paulo, Brazil: Editora Peirópolis, 2000.

Simpson, Leanne. “First Words.” In Alliances: Re/envisioning Indigenous/

Non-Indigenous Relationships, edited by Lynne Davis, xiii–xiv. Toronto:

University of Toronto Press, 2010.

N A I S 5: 1 2 0 18 For Abiayala to Live, the Americas Must Die 61

This content downloaded from

128.83.214.19 on Tue, 19 Jan 2021 06:57:10 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

Smith, Linda Tuhiwai. Decolonizing Methodologies: Research and Indigenous

Peoples. 2nd ed. London: Palgrave Macmillan, 2012.

Tuck, Eve, and K. Wayne Yang. “Decolonization Is Not a Metaphor.” Decoloniza-

tion: Indigeneity, Education and Society 1, no. 1 (2012): 1–40.

Wagua, Aiban. Así lo vi y así me lo contaron: Datos de la revolución Kuna; Versión

del Sailadummad Inakeliginya y de kunas que vivieron la revolución de 1925.

Panama: Nan Garburba Oduloged Igar, 2007.

Warrior, Robert, ed. The World of Indigenous North America. London: Rout-

ledge, 2014.

Washington, George. “Farewell Address.” U.S. History Online Textbook. http://

www.ushistory.org/us/17d.asp.

Webber, Jeffrey. R. “Revolution against ‘Progress’: The TIPNIS Struggle and

Class Contradictions in Bolivia.” International Socialism. 2012. http://www

.isj.org.uk/?id=780.

Wolfe, Patrick. “Settler Colonialism and the Elimination of the Native.” Journal

of Genocide Research 8, no. 4 (2006): 387–409.

Womack, Craig. Red on Red: Native American Literary Separatism. Minneapolis:

University of Minnesota Press, 1999.

Notes

Readers familiar with the work of Russell Means (Oglala Lakota) will notice

that the inspiration for the title of my work comes from his essay “For America

to Live, Europe Must Die.” Means’s essay in Spanish can be accessed with the

following link: http://lakotaes.skyrock.com/1931687975-Discurso-de-Rusell

-Means.html.

1. Some academics and activists also use Abya Yala and Abia Yala. In this

work I use spelling used and suggested by the Dule (Guna) historian Aiban

Wagua in his book Así lo vi y así me lo contaron (Thus I saw it and thus they

told me).

2. The Guna are one of eight officially recognized Indigenous nations in

Panama. The other seven are Ngäbe, Bugle, Teribe/Naso, Bokota, Embera, Wou-

naan, and Bri Bri. The Guna Yala Shire (also Kuna and Kuna Yala) was created in

September 1938 and comprises an insular area composed of about forty islands

and twelve villages. According to the 2010 population census of the Republic

of Panama, the Indigenous population of the region of Guna Yala represents

33,109 people. According to the same document, in 2010, approximately

30,000 people in other parts of Panama were identified as Gunas (Pereiro et

al., 16). The name of the region officially changed from Kuna to Guna in Octo-

ber 2011, when the Panamanian government acknowledged the petition of the

saylas, or Indigenous authorities, that their mother tongue does not use a pho-

neme for the letter K. Hence, the official name should be Guna and Guna Yala or

Gunayala.

3. The General Guna Congress (CGK) was formed and institutionalized in

1945. It is the highest political-administrative body of this Indigenous nation

and is made up of representatives from forty-nine communities in the Guna

62 Emil Keme NA IS 5:1 2 0 18

This content downloaded from

128.83.214.19 on Tue, 19 Jan 2021 06:57:10 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

Yala Territory. For more information, visit its website: http://www.gunayala.

org.pa/index.htm.

4. I include both terms, “sovereignty” and “autonomy,” taking into

account that they have been used by several Indigenous nations in Abiayala.

Maya Zapatistas in Chiapas, Mexico, for example, speak of “autonomous com-

munities.” Given the history of treaties that recognize their traditional territo-

ries with hegemonic rule, Indigenous nations in what is now the United States

and Canada emphasize their status as “sovereign” nations. These discussions

are complex, and in this article I do not have time to go into greater depth. It is

important to recognize the valuable work of Glen Coulthard on First Nations in

Canada and their struggles for sovereignty. According to Coulthard, we should

not confuse the struggles for our self-determination with policies of recog-

nition. Our work involves invalidating the legitimacy of the modern/colonial

nation-state and its policies of Indigenous “recognition” in order to material-

ize our sovereignties.

5. As far as I am aware, the Quito Declaration of 1990 is the first official

Indigenous document that uses the term Abiayala politically and collectively.

As is known, the meeting “500 Years of Indian Resistance” took place in Q uito,

Ecuador, between July 17 and 21, 1990. It was attended by representatives of

120 Indigenous nations of the hemisphere, international organizations, and

non-Indigenous organizations that support Indigenous rights. The meeting

sought “to establish once and for all areas of work and coordination that will

definitively allow us to advance in our demands for justice, respect, and free-

dom” (89). The declaration, among other things, speaks of “the defense and

conservation of nature, Pachamama (Mother Earth), of Abya-Yala (the Amer-

ican Continent), of the equilibrium of the ecosystem and the conservation of

life” (100).

6. From now on, I will use (Latin) America to refer to this geopolitical

context.

7. Of the thousands of languages mentioned by Berkhofer, today over a

thousand Indigenous languages survive. This speaks of our complex diversity

and differences as Indigenous nations (K’iche’ Maya, Aymara, Quechua, Navajo,

Osage, etc.). See Ethnologue: Languages of the World in order to access the

information about Indigenous languages: https://www.ethnologue.com/region

/Americas.

8. It is also necessary here to take into account the complexity of Indig-

enous notions when considering Indigenous/Afro-descendant populations

that use the notion of Indigeneity in the defense of their cultures. Such is the

case of the Garífuna population in what is now Central America and those who

assert their Indigeneity based on the biological/cultural mixture between Afro-

descendants and Carib-Arawak peoples. Similar experiences emerge in what

is now Surinam and the Guyanas with the Kali’ña, Lokono, and Akawaio pop-

ulations and the Wayuu populations in Guajira in what is today Colombia and

Venezuela.

9. In the same article and in his 2014 NAISA presidential address, Allen has

tried to conciliate his position by recognizing the work that Native American

N A I S 5: 1 2 0 18 For Abiayala to Live, the Americas Must Die 63

This content downloaded from

128.83.214.19 on Tue, 19 Jan 2021 06:57:10 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

writers like Allison Hedge Coke have done in translating and publishing Indige-

nous writers from the south of Abiayala to English or international gatherings

that have led to the formation of important international organizations like

the World Council of Indigenous Peoples.

10. I must confess I was overjoyed to find some Indigenous works in select

Iximulew bookstores, such as House Made of Dawn (La casa hecha de alba) by

N. Scott Momaday and Custer Died for Your Sins (El general Custer murió por

vuestros pecados) by Vine Deloria Jr. The effort of publishers such as Abya Yala

in Ecuador and LOM in Chile is also laudable. They have translated seminal

works into Spanish, such as Disciplining the Savages (Disciplinar a los salvajes)

by Martin Nakata and Decolonizing Methodologies (Descolonizar las metod-

ologías) by Linda Tuhiwai Smith.

11. Works of various time periods such as the Popol Wuj, Annals of the

Kaqchikeles, El Huarochirí, Time Commences in Xibalbá by Luis de Lión, among

many others are available to us in English when it comes to thinking about cur-

ricular strategies or transhemispheric exchanges.

12. The category of Turtle Island has been used to delineate Indigenous ter-

ritories in what is now “North America” (Mexico, the United States, and Can-

ada). Similarly, Tawantinsuyu corresponds to what is now the Andean region

(Peru, Ecuador, Bolivia), Anahuac has been used to refer to what is now Meso-

america (present-day Mexico and Central America), and Pindorma is the cate-

gory which the Tupi-Guarani used before the arrival of the Portuguese in what

is now Brazil. For more detailed discussions regarding these categories, see the

studies of Hewitt; Reynaga; Sevcenko; and Moonen.

13. Let us remember Columbus’s epistemic violence when he sought to erase

the Indigenous memory of Indigenous peoples in the Caribbean: “To the first

island I discovered I gave the name of San Salvador in commemoration of His

Divine Majesty, who has wonderfully granted all this. The Indians call it Gua-

naham. The second I named the Island of Santa María de Concepción; the third,

Fernandina; the fourth, Isabella; the fifth, Juana; and thus to each one I gave a

new name.” Note how the Genoese admiral categorically sets aside the Indige-

nous names of the islands in order to impose Spanish ones.

14. These sections within NAISA and LASA have worked to support the pres-

ence and debates of Indigenous (and Afro-descendant in the case of ERIP and

Otros Saberes) scholars/activists from the south of Abiayala, which has been

significant in creating productive dialogues and exchanges.

15. For more information on the Nican Tlaca Mexica movement, see http://

www.mexica-movement.org/. In addition to posters, they have also created

videos published on social media like YouTube, Facebook, and so on. See, for

example, the video Latinos/Hispanics Have Native American Ancestry, https://

www.youtube.com/watch?v=AHwlgi6zu9E.

16. Indeed, filibusterer William Walker invaded Nicaragua and declared

himself president in 1856.

17. See Calfunao; Linconao.

18. See Hernández.

19. See Idle No More.

64 Emil Keme NA IS 5:1 2 0 18

This content downloaded from

128.83.214.19 on Tue, 19 Jan 2021 06:57:10 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

20. See Aguilar.

21. On July 7, 2016, Cáseres’s fellow team member Lesbia Yaneth Urquía was

also killed because of her struggle against multinational companies. See “Ase-

sinan a Lesbia Yaneth.”

22. For Indigenous struggles in Abiayala solely in 2012, see Schertow.

23. See Martí, 34.

N A I S 5: 1 2 0 18 For Abiayala to Live, the Americas Must Die 65

This content downloaded from

128.83.214.19 on Tue, 19 Jan 2021 06:57:10 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

This content downloaded from

128.83.214.19 on Tue, 19 Jan 2021 06:57:10 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

FIGURE 1. Aaron Carapella, Tribal Nations of the Western Hemisphere. Le wachib’al usipanik le Aaron

Carapella.

IMAGEN 1. Aaron Carapella, Tribal Nations of the Western Hemisphere. Cortesía de Aaron Carapella.

FIGURE 1. Aaron Carapella, Tribal Nations of the Western Hemisphere. Courtesy of Aaron Carapella.

This content downloaded from

128.83.214.19 on Tue, 19 Jan 2021 06:57:10 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

FIGURE 2. “Nican Tlaca,” Mexica Movement. Le wachib’al usipanik le Mexica

Movement.