Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Corruption and Foreign Direct Investment

Uploaded by

saraCopyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Corruption and Foreign Direct Investment

Uploaded by

saraCopyright:

Available Formats

Corruption and Foreign Direct Investment

Author(s): Mohsin Habib and Leon Zurawicki

Source: Journal of International Business Studies , 2nd Qtr., 2002, Vol. 33, No. 2 (2nd

Qtr., 2002), pp. 291-307

Published by: Published by: Palgrave Macmillan Journals on behalf of Academy of

International Business.

Stable URL: https://www.jstor.org/stable/3069545

JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide

range of content in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and

facilitate new forms of scholarship. For more information about JSTOR, please contact support@jstor.org.

Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of the Terms & Conditions of Use, available at

https://about.jstor.org/terms

Palgrave Macmillan Journals is collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve and extend access

to Journal of International Business Studies

This content downloaded from

202.125.103.103 on Mon, 28 Jun 2021 23:21:51 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

Corruption and Foreign Direct

Investment

Mohsin Habib*

UNIVERSITY OF MASSACHUSETTS, BOSTON

Leon Zurawicki**

UNIVERSITY OF MASSACHUSETTS, BOSTON

This study examines the impact of ined. The analysis provides support

corruption on foreign direct invest- for the negative impacts of both.

ment (FDI). First, the level of cor- The results suggest that foreign

ruption in the host country is ana- investors generally avoid corrup-

lyzed. Second, the absolute differ- tion because it is considered wrong

ence in the corruption level between and it can create operational in-

the host and home country is exam- efficiencies.

INTRODUCTION ment intervention, barriers to entry and

Since 1986, with the liberalization of competitive climate, are much less so.

the regimes in many FDI recipient coun- The analysis is further complicated, as it

tries, the volume of foreign direct invest- is not clear at what stage of the FDI de-

ment (FDI) has been growing over 20% cision-making process specific variables

annually (WIR, 2001). Even though FDI are considered (Schniederjans, 1999).

is a popular subject in international busi- One factor that has drawn attention

ness literature (see Caves, 1996; and En- lately is corruption in the host countries.

sign, 1996), the recent surge in FDI de- Corruption has gained prominence as

mands new attention. Numerous statisti- the contacts between less corrupt and

cal and econometric analyses addressed corrupt countries intensified in the

more

the spatial distribution of FDI and the last decade. Corruption does not seem to

underlying forces. Modeling FDI isdeter

a FDI in absolute terms. China, Bra-

zil, Thailand and Mexico attract large

complicated task because so many vari-

ables intervene. Among explanatory

flows of FDI despite their perceived high

variables, general economic phenomenacorruption. Within the industrialized

are quantifiable and available. Others,

world, while Italy is perceived relatively

corrupt and receives modest inflows of

like the quality of workforce, govern-

* Mohsin Habib is Assistant Professor of Management at the University of Massach

Boston. His research interests include FDI and ethics in the context of multinationals.

** Leon Zurawicki is Professor of Marketing at the University of Massachusetts, Boston. H

interests focus on competition among multinational corporations and locus of their FDI.

We wish to thank the anonymous referees and the editor for their valuable comments on ear

drafts of this paper.

291

JOURNAL OF INTERNATIONAL BUSINESS STUDIES, 33, 2 (SECOND QUARTER 2002): 291-307

This content downloaded from

202.125.103.103 on Mon, 28 Jun 2021 23:21:51 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

CORRUPTION AND FDI

FDI, Belgium, which is similarly rated bilities, and the reduction in transaction

on corruption (by Transparency Interna- costs. The third element, location (L) ad-

tional), attracts substantial FDI. Address- vantages, has attracted renewed atten-

ing such a paradox requires careful anal- tion due to (1) changes in the extent,

ysis. So far, scholars in economics and character and geography of MNE activity

public policy have dealt with corruption in the last two decades, and (2) the link-

(Bardhan, 1997). Analogous empirical ages of the spatial aspects of the MNE

research from the international business

value-added activities to firm competi-

perspective is scanty. tiveness (Dunning, 1998). The location

Understanding the pernicious role ofof FDI is driven by the search for (1)

corruption in FDI is important since itmarkets, (2) resources, (3) efficiency, and

produces bottlenecks, heightens uncer-(4) strategic assets (Dunning, 1998). This

tainty, and raises costs. Further, corrup-implies that different location selection

tion creates distortions by providing criteria apply to projects of different mo-

some companies preferential access totivation. Thus, identifying the variables

profitable markets. The difference in theexerting the strongest impact on particu-

exposure to corruption between the host lar types of investment is important.1

and home countries can also be a con- The majority of previous studies have

relied on total FDI inflow data, obscuring

cern for investors. The greater such dif-

ference between the two countries, the the links between specific location char-

lower the likelihood that they know how acteristics and the type of motivation.

to deal mutually. Given a choice be- This study also uses aggregate FDI data,

tween a familiar and a less familiar en-

however, when appropriate, the location

variables relevant to specific FDI orien-

vironment, firms will prefer the former

(Davidson, 1980). tation are highlighted.

This paper adopts a dual approach in Identifying additional variables can

assessing the impact of corruption on expand our knowledge of the (L) advan-

FDI. First, the effect of the level of cor- tages and their influence on FDI. To this

ruption in the host country is investi- end, corruption, a factor that has re-

gated. Second, the effect of the difference ceived attention lately, is included

in the corruption levels between the among the descriptors of the attractive-

home and host countries is examined. ness of a location. Corruption is defined

The paper is organized as follows. Ain various ways. International organiza-

re-

view of corruption and its impact on tions

FDI (UN) and Western governments

equate corruption with "improbity",

are presented first. Based on this review,

hypotheses are developed. Analysis which

and encompasses not only what is il-

results are then reported. Finally, legal,

the but also improper (Malta Confer-

end section discusses the findings ence,

and 1994). The World Bank empha-

their implications. sizes the abuse of public power for pri-

vate benefit (Tanzi, 1998). Whereas

THEORY

corruption of public employees is a dom-

inant theme, Coase (1979) also argues

The OLI paradigm (Dunning, 1988)

that corruption exists between private

provides guidance for FDI activities. The

ownership (0) and internalization (I) parties.

ad- Although corruption can be op-

vantages are derived from the exploita-erationalized as an all-inclusive variable,

comprising bribes, bureaucratic ineffi-

tion of firm-specific resources and capa-

292 JOURNAL OF INTERNATIONAL BUSINESS STUDIES

This content downloaded from

202.125.103.103 on Mon, 28 Jun 2021 23:21:51 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

MOHSIN HABIB, LEON ZURAWICKI

ciency, and political instability, it is proximations of the economic and polit-

used here to describe bribery in private ical risks of host countries. Foreign in-

and public sectors. vestors may consider corruption morally

Studies have looked into the anteced- wrong and stay away from countries

ents and consequences of corruption for

with high levels of corruption. For exam-

the national economy. Rose-Ackerman ple, a number of African countries where

(1975), Shleifer and Vishny (1993), Mac-

corruption is rampant, the economy poor

rae (1982), and Husted (1994) providedand not growing, receive very little FDI

the theoretical frameworks using public

(WIR, 2001). Honesty has its price, how-

choice, game theory, and transaction- ever, if it means inability to compete in

cost economics. Shleifer and Vishny

some markets.

(1993) argued that in countries with dis- Corruption is widespread in countries

organized corruption, economic growth where the administrative apparatus en-

would suffer. Mauro (1995) linked the joys excessive and discretionary power,

corrupt institutions with the perpetua- and where laws and processes are barely

tion of inefficiency. Gupta, Davoodi and transparent (Tanzi, 1998; LaPalombara,

Alonso-Terme (1998) demonstrated how 1994). Also, lack of economic develop-

corruption impacts economic develop- ment and income inequalities increase

ment and worsens poverty. corruption (Alam, 1995; Macrae, 1982).

Simultaneously, another stream of Corruption inhibits the development of

thought (Leff, 1964; Braguinsky, 1996) fair and efficient markets (Boatright,

holds that in case of rigid egalitarian re- 2000). A corrupt economy does not pro-

gimes, corruption need not deteriorate vide open and equal market access to all

economic performance. In this context, competitors. Price and quality become

bribes "grease" the system and contrib- less important than access, since bribery

ute to Pareto optimality (Rashid, 1981). takes place in secret. Payments to the

However, Kaufmann and Wei (1999) host country officials do not have a mar-

showed that companies that pay more ket value and, hence, raise the cost of

goods when compared to a competitive

bribes waste more time negotiating with

bureaucrats. Hence, because of the greedmarket. This can be a major disincentive

of the corrupt officials the "grease effect"

for foreign investors. Corruption persists

might not materialize (Tanzi, 1998). because some companies can use it to

Beck and Maker (1986) and Lien (1986) advance their own interests. Had each

showed that in bidding competition, the and every investor (local and foreign)

most efficient firms pay the most bribes. resisted corruption, their combined

Lui (1985) suggested that firms placing a power would have eradicated it. That

high value on time offer bribes to make does not happen because a game of "out-

decisions quickly. Thus, corruption en- smarting" others is sometimes played.

hances allocation efficiency. However, Empirical analyses have not yet con-

Tanzi (1998) suggested that those paying sistently confirmed the negative relation-

the highest bribes are not necessarily the ship between corruption and FDI. Hines

most efficient firms but successful rent- (1995) found a non-significant relation-

seekers. ship between the two. Also, Wheeler and

Corruption and FDI have only recently Mody (1992) did not detect a significant

been jointly considered. Previously, cor- negative relationship between FDI and

ruption was incorporated in different ap- the host country risk factor, a composite

VOL. 33, No. 2, SECOND QUARTER, 2002 293

This content downloaded from

202.125.103.103 on Mon, 28 Jun 2021 23:21:51 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

CORRUPTION AND FDI

measure including corruption. However, under control. Also, the host country's

this result could be affected by the mea- willingness to accept the presence of TI

sure itself since, besides corruption, it chapter sends a positive signal. If, how-

combined twelve other indicators, some ever, corruption is deeply ingrained,

of them marginally important for FDI bringing in TI can help improve the cur-

(Wei, 2000). Drabek and Payne (1999) rent FDI situation but may not do much

tested how FDI was affected by non- to actually combat corruption. Empiri-

transparency, a composite of corruption, cally, the impact of corruption on FDI

unstable economic policies, weak and when a corporate watchdog is present is

poor property rights protection, and poor yet to be determined. Hence, the follow-

governance. Results indicated the nega- ing hypothesis is proposed.

tive impact of high levels of non-trans-

Hypothesis lb: Corruption will con-

parency on FDI.

tinue to have a negative effect on FDI

Other studies identified a negative re-

when TI in the host country is in-

lationship between corruption and FDI.

cluded as an independent variable in

Wei (2000) analyzed data on FDI in the

the analysis.

early 1990s from 12 source countries to

45 host countries. Corruption revealed a It is believed that political stability

significant and negative effect on FDI. positively affects FDI (Kobrin, 1976) and

Busse et al. (1996) looked at the relation- that political stability and corruption are

ship between FDI and the level of cor- negatively correlated (Wei, 2000). Uncer-

ruption exposed by the local media. tain political situations make investors

Reviewing the inconsistent results per- and public officials short-term oriented

taining to different countries, they hy- and pursuing personal gains while sacri-

pothesized that FDI increased when in- ficing the legality. Alternatively, a stable

vestors believed that the government political environment encourages a long-

would curb corruption. Alternatively, term orientation and reduces incentives

FDI would decrease with media expo- for quick illegal returns. In the end,

sure should investors assume that the

whether the dual effects of political sta-

government was unwilling to improve

bility will actually change the FDI-cor-

the environment. This suggestion, how- ruption relationship is an open question.

ever, was not rigorously validated. Given

The following hypothesis is suggested.

the state of the literature, the following

basic hypothesis is proposed first. Hypothesis lc: Corruption will con-

tinue to have a negative effect on FDI

Hypothesis la: Corruption will havewhen

a political stability is included as

negative effect on FDI. an independent variable in the analy-

Various institutions monitor and ex- sis.

pose corruption. International organiza-

tions are better suited to perform this Difference Between Home and

task objectively as the local (corrupt) en- Host Country Corruption

vironment influences them less. Watch-

Levels and FDI

dogs like Transparency International (TI) For a long time, researchers looked at

can serve two purposes: as a deterrent to the order of selection of foreign markets

corrupt officials and as a reassurance to Since Cyert and March (1963), the be-

havioral model attempted to identify th

the investors that the situation is getting

294 JOURNAL OF INTERNATIONAL BUSINESS STUDIE

This content downloaded from

202.125.103.103 on Mon, 28 Jun 2021 23:21:51 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

MoHSIN HAIB, LEON ZURAWICKI

markets firms enter first and determine and risky commitment among the inter-

how they organize at each stage of devel-national business activities (Johanson

opment within the new market. A deci- and Wiedersheim-Paul, 1975). Two in-

sion to enter a foreign market is a func- fluences of opposing directions can oc-

tion of knowledge and experience, andcur. First, psychic distance can prove a

the selection of a similar market reduces

greater impediment to FDI in a particular

uncertainty (Aharoni, 1966). In the 70's,

country than to other modes of interna-

the Scandinavian authors categorized tional business. Second, applying previ-

the "psychic distance," to assert that ous lessons from exporting and licens-

companies enter markets perceived to being, the international investors may

psychologically closer before consider-bridge their knowledge and experience

ing the remote ones (Johanson and Wied- gap.

ersheim-Paul, 1975; Johanson and In this study, the notion of similarity

Vahlne, 1977, 1990). Two importantthat as- closely resembles the psychic dis-

pects are emphasized: (1) lower leveltanceof idea is adopted. The similarity ap-

uncertainty in psychically close coun- proach is simpler and more clear-cut as

tries (Johanson and Vahlne, 1990), and it does not presuppose managers' level of

(2) psychic closeness facilitating learn-

knowledge about the host country. Cor-

ing about the target countries (Kogutruptand practices represent a component of

Singh, 1988). local business and administrative cus-

Over the years, more studies were un- toms. Inability to handle corruption

dertaken. Some (Davidson, 1980; Nord- makes FDI challenging for companies

strom and Vahlne, 1992) corroborated from less corrupt countries and can re-

the hypothesis that firms expand first to sult in a negative FDI decision. Alterna-

the psychically close and then to the tively, exposure to corruption at home

more psychically remote countries. Yet, provides a learning experience preparing

Benito and Gripsrud (1992) and Engwall the individual companies to handle

and Walenstal (1988) found no support them abroad. Hence, acquiring skills in

for the hypothesis that the first FDIs are managing corruption helps develop a

made in the countries that are culturally certain competitive advantage. This ad-

closer to the home country. Recently, vantage is lost or turned into disadvan-

Ghemawat (2001) suggested that four di- tage when expertise in corruption be-

mensions of distance namely cultural, comes redundant in "clean" markets.

administrative, geographic and eco- While it is easy to comprehend that the

nomic, influence companies considering difference in corruption level between

global expansion. Within this taxonomy, two countries would be more problem-

difference in corruption levels between atic for investors coming from a less cor-

the host and home countries is part of rupt environment than those from a

the administrative distance that creates

more corrupt one, it still constitutes a

significant barriers for foreign investors.

"distance" that both types of investors

To complicate matters further, the psy-

have to overcome. Applying the similar-

chic distance can exert different effects

ity approach to corruption, the following

depending on the mode of firms' in-

hypothesis is proposed.

volvement in international business. To

date, only a handful of psychic distance Hypothesis 2: The greater the absolute

studies addressed FDI, the most serious difference in the corruption levels be-

VOL. 33, No. 2, SECOND QUARTER, 2002 295

This content downloaded from

202.125.103.103 on Mon, 28 Jun 2021 23:21:51 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

CORRUPTION AND FDI

tween the home and the host coun- ables in the study. In this model, the

tries, the lesser the FDI inflow for dependent

the variable is the log of FDI. FDI

host country. is the annual inflow between the home

and the host country. Log of FDI is used

METHODOLOGY

in the analysis to render the distribu-

tions

The study includes a large number of nearly normal and the error term

host countries offering a broad perspec- homoscedastic. Data on FDI is collected

tive on FDI and corruption. The statistics from the IMF (2000).

on aggregate bilateral FDI flows are ana- The key independent variables are cor-

lyzed in conjunction with key observa- ruption (measured by CPI) and the abso-

tional variables. Most of the data for the lute difference in corruption (Abs. Diff.

sample is derived from the Internationalin CPI) between the host and the home

Monetary Fund (IMF, 2000). The latestcountry. Measuring corruption is prob-

three years with significant country datalematic. There is no consensus among

(1996-1998) are chosen. Altogether, 89researchers regarding what should be

countries are included. These countries measured (Lambsdorff, 1999). Objective

represent the whole spectrum, compris- measures are hardly available because of

ing developed, developing, and the tran- the secrecy of corrupt dealings. Subjec-

sition economies. The selection of the tive measures relying on questionnaire-

home countries: Germany, Italy, Japan, based surveys represent an acceptable al-

Korea, Spain, UK and the USA aims to

ternative for this problem. They measure

provide a fair representation of the

theperception of corruption rather than

Triad, while incorporating countries

corruption per se. Such surveys are com-

piled by organizations like Transparency

with markedly varying levels of Corrup-

International (TI), Political Risk Ser-

tion Perception Index (CPI), a measure

produced by Transparency International and World Economic Forum. In-

vices,

(TI). This is very important, as based terestingly,

on the respective indices are

the methodology applied by TI relatively highly correlated (Tanzi, 1998). In this

small differences in CPI for individual study, the corruption measure collected

by TI (1999) is used. TI, a non-govern-

countries are not statistically significant.

The three-year bilateral FDI data wasmental organization, publishes the Cor-

ruption Perception Index (CPI), which is

pooled together for statistical analysis.

an average of multiple surveys of coun-

Accordingly, a maximum of (7 x 89 x 3)

1869 observations for the variables wastry and business experts. The index

expected. However, a large number of ranks up to 100 countries from the most

missing values related to a country ortoa the least corrupt on a 0 to 10 scale.

year produced fewer total observations.Since its inception in 1995, academics

Two different models are used in this and companies have used the CPI exten-

sively.

study to analyze the effects of corruption

on FDI. The first is an OLS regressionBesides the key independent vari-

model. The second is a PROBIT model, ables, the regression model includes

devised to assess the impact on FDI of"control" variables reflecting the deter-

the absolute differences in corruptionminants of FDI suggested in the litera-

ture. First, variables that affect all FDI

levels between the home and the host

endeavors are included. Second, vari-

countries. The OLS approach is appro-

ables that influence the location of spe-

priate given the use of continuous vari-

296 JOURNAL OF INTERNATIONAL BUSINESS STUDIES

This content downloaded from

202.125.103.103 on Mon, 28 Jun 2021 23:21:51 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

MOHSIN HABIB, LEON ZURAWICKI

cific types of FDI are highlighted. A brief (Billington, 1999). Under high unem-

discussion of the variables follows. ployment, workers value their current

A classic reason for FDI is the search job higher and are willing to accept

lower wages to keep the jobs. Thus, a

for new markets. FDI is positively influ-

enced by the size of the host economy high unemployment would positively af-

measured by its GDP or population (Ko-fect the resource-seeking FDI. The unem-

brin, 1976). Large markets provide a rea-

ployment data was gathered from the In-

sonable scope for investment and hence ternational Labor Organization (ILO,

influence market-seeking FDI. Log of 2001).

population is our measure of countryStrategic linkage theory (Nohria and

size. Garcia-Pont, 1991) and the network ap-

Host countries' growth rates of GDP proach (Johanson and Mattson, 1988)

seem to be positively related to FDI (Ko- have been presented as other explana-

brin, 1976; Nigh, 1986). High growth en-tions for FDI. Accordingly, FDI serves to

sures demand for the output of the localacquire strategic resources that the firms

market-oriented FDI. GDP growth is in- are lacking. Dunning (1998) and Doz,

cluded in this study. Santos & Williamson (2001) emphasized

GDP/capita is a significant explanatorythe need for most foreign firms to find

variable for FDI (Wells and Wint, 2000; locations supporting innovative activi-

Grosse and Trevino, 1996). High GDP/ ties. Host countries with higher scores

capita reflects high consumption poten- on science and technology will be pre-

tial in the host country. Log of GDP per ferred for asset-seeking FDI. Country rat-

capita is used in this study. ings for science and technology are

Export orientation of the host country adopted for this study from the World

can stimulate FDI (Jun and Singh, 1996). Competitiveness Yearbook (1999).

Countries open to international trade It has been shown that the duration of

provide a good platform for global busi- diplomatic and economic ties between

ness operations. Also, a country's inter- the home and host country increases the

national orientation reflects its competi- likelihood of FDI (Tse, Pan and Au,

tiveness. International orientation of a 1997). Greater business interactions

country is measured as the trade/GDP should promote understanding between

ratio from the IMF (2000) data. the home and host country that is con-

ducive to FDI. Economic ties reflecting

Political stability strongly affects FDI

(Kobrin, 1976). It is considered an imper-

the home and the host country participa-

ative for planning, profitability, andtion in the same common market areas

(EU, NAFTA, ASEAN) or preferential

long-run success. Political Risk Services,

Inc. (2000) publishes Political Risk In-

trade agreements (Lome Convention, Ca-

dex, which is on a scale of 0 to 100, with

ribbean Initiative) are included as a

100 being the most politically stable. The

(dummy) variable in this study. Data was

index is used in this study. collected from the official membership

Labor is another factor importantliststo of the regional blocs.

foreign investors. The more abundant As mentioned earlier, cultural and

(with lower costs) labor is, the more at-

geographic distance affects FDI. Cultural

tractive the location becomes. Country-proximity between the two countries

level unemployment figures have been will facilitate FDI operations. It was cal-

culated applying the Kogut and Singh

considered a proxy for labor availability

VOL. 33, No. 2, SECOND QUARTER, 2002 297

This content downloaded from

202.125.103.103 on Mon, 28 Jun 2021 23:21:51 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

CORRUPTION AND FDI

(1988) formula to Hofstede's four dimen- Then a categorical variable was devel-

sions of culture. Geographic proximity oped. 0 is assigned if the host country's

exerts a multifaceted impact on FDI, fa- share in global FDI exceeds its share in

cilitating contact with host country and the home country's total outgoing FDI

reducing the transportation costs. Also, (under-investment). 1 applies to cases

in case of large geographic distance, the when the host country's share in global

transportation costs encourage substitu- FDI is equal to or lower than its share in

tion of exports by market-oriented FDI the home country's total FDI (over-in-

(Brainard, 1997). Log of geographic dis- vestment). This categorical variable

tance between the home and the host which focused on relative "under-invest-

countries was calculated from Hen- ment," as opposed to relative "over-in-

geveld (1996). vestment," is subsequently used as a de-

pendent variable in the PROBIT analy-

Finally, the presence of the corporate

watchdogs in the host countrysis, is to

in-estimate the probability that the

cluded as a variable affecting FDI.bilateral

It is FDI flows would fit one or an-

other category as a function of a set of

expected that the presence of organiza-

independent variables. Data on a coun-

tions such as TI will improve the invest-

ment climate. Representation of TI try's

in theshare in global FDI is calculated

from the IMF (2000). Data on the coun-

host country was included as a dummy

variable in the study (TI, 1999). try's share in the total FDI of the home

country

In order to avoid a problem known as is calculated from the OECD

(2000) statistics.

the "omitted variable bias," the regres-

Most of the independent variables

sion model is developed to be as inclu-

sive as possible. All the independent included referred to the same factors as

variables described earlier are included in the OLS regression model.2 How-

in the same model. A test of multicol- ever, since the PROBIT model focuses

linearity among independent variables on the impact of similarities, except for

the geographic distance and economic

using the variance-inflation factor (VIF)

ties, all other independent variables

did not suggest any serious problem.

None of the VIF values exceeded 3. VIF are considered in terms of absolute dif-

values of 5.3 (Hair, Anderson, Tatham ferences between the home and the

and Black, 1992) and 10 (Studenmund, host country levels. It is expected tha

1992) have been suggested as cutoffs for these differences would lead to greate

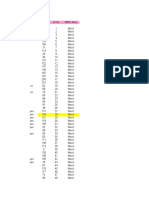

multicollinearity. Table 1 reports the de- difficulties in operations of foreign

scriptive statistics. firms and, hence, deter FDI. The only

The second (PROBIT) model attempts new variable added is the log of the

to explain the differences between the absolute difference in Gross Capital

host country's share in the global (total) Formation/capita. Like most other vari-

incoming FDI and the same country's ables, it is included to capture as much

share in a specific home country's FDI. as possible the macro environmental

First, the raw differences were calcu- differences between the host and home

lated: countries. GCF data is calculated from

the IMF (2000). Table 2 presents the

Difference in share of FDI = Global

descriptive

Share - Countryi Share, where i denote a statistics for the PROBIT

particular home country of outgoingmodel.

FDI.

298 JOURNAL OF INTERNATIONAL BUSINESS STUDIES

This content downloaded from

202.125.103.103 on Mon, 28 Jun 2021 23:21:51 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

C

o

t TABLE 1

MEANS, ST

Variable Mean s.d. N 1 2 3 4 5 6 7

C) 1. Log population 2.70 1.48 1785

2. GDP Growth 3.65 4.49 1750 -.05*

3. Log GDP/Capita 8.01 1.44 1750 -.12** -..12***

4. Unemployment 7.82 4.09 889 .05 -.07* .02

O 5. Trade/GDP 0.69 0.51 1750 -.35*** .08** .12*** -.15***

t 6. 6Science &

Technology 50.72 14.55 903 -.01 -.09* .62*** -.09' -.03

7. Cultural

Distance 59.74 22.97 1029 -.12*** .02 -.15*** -.20*** .23*** -.08*

8. Political

Stability 72.41 11.71 1582 -.26**" -.07** .78"** -.19**" .31*** .41*** -.05

9. Log Distance 8.11 0.89 1848 .09*** .06* -.25*** -.13*** -.09*** -.14*** .14*** -.27

10. Economic Ties 0.20 0.40 1830 .07** -.05 .31** .11 .07** .12"'* -.17*** .2

11. Corruption

Perceptio

Index (CPI) 4.96 2.45 1491 -.30*** -.03 .868' -.07 .20** .55**

12. Abs. Diff. In

CPI 2.79 1.72 1465 .12**' .01 -.31*** -.00 -.14'** -.17*** .42*** -.

13. LogFDI 4.34 2.45 785 .20*** .02 .23"* -.00 -.06 .22'' -.14'* .1

*p < .05, **p < .01, ***p < .001.

N~~c~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~~D~~IN

CD

CO

This content downloaded from

202.125.103.103 on Mon, 28 Jun 2021 23:21:51 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

o ~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

MEANs, STANDARD DEvIATIONs, AND CORRxELTIONS FOR

Variable Mean s.d. N 1 2 3 4 5

1. FDI Mode .229 .4205 1283

2. Abs. Diff. In GDP

Growvth 2.298 2.144 1785 -.074**

3. Log Abs. Diff. in

GDP/Capnita 4.071 .3884 1785 -~.214** -.175**

4. Log Abs. Diff. In

GCF/Capita 3.362 .4062 1785 -.111** .209* .512*

5. Abs. Diff. In

Uniemployment 6.276 4.767 747 -.109** -.049 -.019 -.O85*

6. Abs. Diff. In

Trade/GDP 18.599 13.712 879 -.100** -.076* .178** -.115** -.174**

7. Abs. Diff. In

Science & Techn. 23.070 18.402 879 -.039 .005 .261 ** .218* -.108* .416*

8. Abs. Diii. In

Political Stability 11.970 9.571 1562 -~.113** .259** .415 ** .403* -.050 .123*

9. Log- Distance 3.523 0.3190 1764 -~.271** .051* .170** .229* * .049 .247*

10. Economic Ties 0.206 0.405 1758 .431* -.178** -.275** -.248* * -.030** -.193**

11. Abs. Diff. In CPI 2.780 1.722 1431 -~.138** .051 ,335** .142** -.093** .345*

*p <.05, **pK<.01.

This content downloaded from

202.125.103.103 on Mon, 28 Jun 2021 23:21:51 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

MOHSIN HABIB, LEON ZURAWICKI

RESULTS p < .001, adjusted R2 = 0.165). This sup-

The OLS regression results for the full ports Hypothesis la.

sample are presented in Table 3. Five Models 3 and 4 are used to test Hypoth-

regression models are run. Model 1 in- eses lb and Ic. Model 3 added political

cludes all the independent variables ex- stability as a variable. As expected, it

shows a significant positive effect on FDI.

cept political stability, TI chapters, CPI,

and absolute difference in CPI. In modelMore importantly, CPI remains a signifi-

cant variable affecting FDI but only at the

1, log of population, log GDP/capita, and

economic ties are significant while p < 0.10 level and the value of its coeffi-

trade/GDP is marginally significant. cient drops from 0.25 to 0.18. Model 4

Hence, consistent with the extant litera- added "TI Chapters" variable that also

ture, country size, consumer purchasing shows a significant positive effect on FDI.

power, open economy, and network of In this model, the CPI variable continues

economies positively affect FDI. The to have a significant, albeit weaker (p <

overall model is statistically significant 0.10), negative effect on FDI (coefficient

and explains 15 percent of the variance drops from 0.25 to 0.18). These results

(F = 9.01, p < .001, adjusted R2 = 0.151). support Hypotheses lb and Ic.

Model 2 introduces the corruption vari- In model 5, the absolute difference in

able, CPI. CPI is significant and nega- CPI is included. The results show that

tively affects FDI (3 = 0.25, p < .05). The difference in CPI negatively affects FDI

standardized coefficient is positive be- (p = - 0.18, p < .001). Also, CPI remains

cause a high CPI means less corruption. significant. The overall model explains

Overall, model 2 is significant (F = 8.97, 20 percent of the variance (adjusted R2 =

TABLE 3

REGRESSION RESULTS FOR THE FULL SAMPLE

(DEPENDENT VARIABLE = LOG FDI)

Variable Model 1 Model 2 Model 3 Model 4 Model 5

Log Population 0.33*** (0.14) 0.43*** (0.16) 0.40*** (0.17) 0.39*** (0.16) 0.44*** (0.16)

GDP Growth 0.01 (0.06) -0.03 (0.06) -0.02 (0.06) -0.04 (0.06) -0.04 (0.06)

Log GDP/Capita 0.22** (0.25) 0.05 (0.31) -0.08 (0.35) 0.14 (0.32) 0.05 (0.31)

Unemployment 0.04 (0.03) 0.07 (0.03) 0.11t (0.03) 0.07 (0.03) 0.06 (0.03)

Trade/GDP 0.11t (0.22) 0.15** (0.22) 0.13* (0.22) 0.11t (0.23) 0.12* (0.22)

Science &

Technology 0.02 (0.01) -0.02 (0.01) 0.04 (0.01) -0.03 (0.01) -0.05 (0.01)

Cultural Distance -0.05 (0.01) -0.06 (0.01) -0.07 (0.01) -0.04 (0.01) 0.02 (0.01)

Log Distance -0.01 (0.15) -0.05 (0.15) -0.07 (0.15) -0.03 (0.16) -0.05 (0.15)

Economic Ties 0.19** (0.31) 0.15* (0.32) 0.13* (0.32) 0.15* (0.32) 0.16** (0.32)

CPI 0.25* (0.11) 0.18t (0.11) 0.18t (0.11) 0.26** (0.11)

Political Stability 0.18* (0.02)

TI Chapters 0.14** (0.30)

Abs. Diff. In CPI -0.18*** (0.09)

Adjusted R2 0.151 0.165 0.173 0.179 0.203

Change in Adj. R2 0.014 0.008 0.006

F 9.01*** 8.97*** 8.68*** 9.00*** 9.48***

N 405 405 405 405 403

Standardized regressio

tp < 0.10, *p < 0.05,

VOL. 33, No. 2, SEC

301

This content downloaded from

ff:ffff:ffff:ffff:ffff:ffff on Thu, 01 Jan 1976 12:34:56 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

CORRUPTION AND FDI

0.203). Model 5 supports both Hypothe- was done because it has been suggested

ses la and 2.3 that GDP/capita and political stability

Hypothesis 2 is also tested using the not only affect FDI, but also corruption

PROBIT model. The results are shown in (Wei, 2000; Husted, 1999). In both mod-

Table 4. Model 1 includes all the control els, difference in CPI remains significant

variables, several of which show signifi-and negatively affects FDI. In fact, the

cant results (discussed later). In model 2,significance level increases to p < 0.05

the difference in the CPI variable is in- level when the two variables are ex-

cluded from the regression model

troduced and shows a marginally signif-

(Model 4). Looking at the coefficients

icant negative effect on the share of FDI

of the difference in CPI across models,

flow (3 = -0.09, p < .10). To further test

the robustness of the difference in CPI there is no indication that the effect is

effect, two additional models were run weaker in the presence of two other

without the absolute difference in GDP/ variables. The results support the neg-

ative effect of the difference in CPI on

capita and the absolute difference in po-

litical stability (Models 3 and 4). This

FDI.

TABLE 4

PROBIT ESTIMATON RESULTS FOR FDI

(0 = LESS SHARE OF FDI, 1 = MORE SHARE OF FDI)

Variable Model 1 Model 2 Model 3 Model 4

Constant -0.37 (1.02) -0.37 (1.02) -1.01 (0.86) -0.96 (0.84)

Abs. Difference in GDP

Growth 0.04 (0.05) 0.04 (0.05) 0.04 (0.05) 0.04 (0.05)

Log Abs. Difference in

GDP/Capita -0.31t (0.18) -0.24 (0.19)

Log Abs. Difference in

Gross Capital

Formation per capita 0.41* (0.20) 0.37t (0.20) 0.30t (0.19) 0.31t (0.18)

Abs. Difference in

Unemployment -0.00 (0.02) -0.00 (0.02) -0.00 (0.02) -0.00 (0.02)

Abs. Difference in

Trade/GDP 0.00 (0.01) 0.01+ (0.01) 0.01t (0.01) 0.01+ (0.01)

Abs. Difference in

Science &

Technology 0.01* (0.01) 0.01* (0.01) 0.01* (0.01) 0.01t (0.01)

Abs. Difference in

Political Stability 0.00 (0.01) 0.01 (0.01) 0.01 (0.01)

Log Distance -0.42* (0.19) -0.43* (0.19) -0.42* (0.19) -0.42* (0.19)

Economic Ties 1.19*** (0.18) 1.18*** (0.19) 1.20*** (0.18) 1.19*** (0.18)

Abs. Difference in CPI -0.09t (0.05) -0.10t (0.05) -0.10* (0.05)

,z 109.61*** 110.23*** 108.75*** 110.59***

N 475 471 471 474

Correctly Predicted 73.7% 74.3% 74.1% 74.1%

-2 Log ikelihood 425.35 420.23 421.71 423.75

Pseudo R2 0.300 0.304 0.300 0.303

Standard errors are in parenthesis.

tp < .10, *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p

302 JOURNAL OF INTER

This content downloaded from

202.125.103.103 on Mon, 28 Jun 2021 23:21:51 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

MOHSIN HABIB, LEON ZURAWICKI

Apart from the difference in CPI, tries. This further suggests that foreign

geographic distance and economic ties firms are unwilling to deal with the plan-

show expected significant results in the ning and operational pitfalls related to

PROBIT analysis (negative and positive an environment with a different corrup-

relationships to FDI, respectively). How- tion level. This important fine point is

ever, some unexpected results emerge. worth emphasizing, as it has not yet been

Log of absolute difference in GCF/capita, empirically tested in the literature.

absolute difference in internationaliza- Including corruption in the FDI model

tion, and absolute difference in scienceshould help the companies realize the

and technology all showed positive sig- individual importance of that factor in

nificant relationships to the share of FDI the site selection.4 More importantly, in

(some only marginally significant at the a dynamic business environment, con-

p < 0.10 level). It seems the greater the sidering corruption relative to other di-

difference the higher the FDI flows into mensions will help the managers imple-

the host country. These results require ment complex analyses and refine coun-

further inspection for possible explana- try evaluation procedures. Based on this

tions. study, even small changes in corruption

matter. Thus, once companies determine

DISCUSSION AND CONCLUSION

the importance of corruption for FDI,

This study examined the relationship their response to the expected deteriora-

between corruption and FDI based on tion/improvement in the host country

the recent three-year data. The findings corruption level would have to be pro-

are consistent with the arguments pre- grammed.

sented in the literature and suggest that Foreign investors should take an ag-

corruption is a serious obstacle for in- gressive stance and combat corruption

vestment. The data for this study are ob- for their own long-term interest. For ex-

tained from international statistics onample, if a competitor obtains a license

FDI, aggregated by countries of origin to operate or secures a contract through

and destination. As such, it generalizes

corrupt dealings it is up to the disad-

the individual experiences of thousandsvantaged companies left behind to blow

of investment projects and adds to the ourwhistle. In many national legal sys-

understanding of the pattern of inves- tems, one can render null and void the

tors' reactions to corruption. agreements obtained through corrupt

activities provided convincing proof is

The theoretical arguments against cor-

presented (Malta Conference, 1994). Ex-

ruption derive from both ethics and eco-

nomics. Foreign investors may shun cor-change of information within the busi-

ruption because they believe it is mor-ness community can foster the process.

ally wrong. They may also try to avoid Examples can be found where compa-

corruption because it can be difficult nies

to have made a difference in the way

manage, risky, and costly. The negativethey managed FDI in a relatively "cor-

rupt" country. McDonalds opened its

effect of corruption on FDI found in this

study suggests that firms, as a whole,successful

do outlet in Moscow instilling its

not support corruption. However, in ad-

international standards and making no

dition, the study also found a negative

compromise for the local "corrupt" envi-

ronment. The name McDonald, obvi-

effect due to the difference in corruption

levels between the home and host coun- ously helped maintain a strong stand

VOL. 33, No. 2, SECOND QUARTER, 2002 303

This content downloaded from

202.125.103.103 on Mon, 28 Jun 2021 23:21:51 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

CORRUPTION AND FDI

against corruption. Another example in- 2. The only omission is the cultural

volving Russia is the 3M Inc., which cap- distance variable. The regression analy-

italized on both the strengths and weak- sis did not find it significant (Table 3).

nesses of the Russian culture positioning Given its correlation with several control

itself as a socially and morally responsi- variables (Table 1), we decided to ex-

ble company. It raised its involvement clude it from further analysis.

with the locals by creating successful 3. As an additional test of the hypoth-

networks but at the same time actively eses, regressions for the FDI samples of

promoted ethical behavior, training its individual home countries are run.

salespeople to avoid illegal acts and per- Apart from CPI and difference in C

sonal harm (Gratchev, 2001). Notwith- variables, fewer control variables are in-

standing such encouraging but infre- cluded so as to accommodate the samp

quently reported initiatives, a continu- size. The majority of the results are co

ing challenge for the companies is how sistent with hypotheses la and 2.

to achieve a unified stance when some 4. Highlighting, for example, that

companies can obtain an unfair advan- change in the level of corruption m

tage through corruption and, in that re- have the same impact on FDI as a chang

spect, outperform their competitors. in the tax rate on earned income.

This study has its limitations. It relied

on the perception-based measure of cor- REFERENCES

ruption. The measure is broad and fails

Aharoni, Yair. 1966. The Foreign Invest-

to capture the different forms of corrup-

ment Decision Process. Division of Re-

tion, which can exert varying impacts on

search, Harvard Business School, Bos-

FDI. Including specific indices of corrup-

ton.

tion in future analyses can help uncover

Alam, M. 1995. A Theory of Limits on

important nuances regarding the overall

Corruption and Some Applications.

burden for the investors (e.g. between a

Kyklos, 48: 419-435.

petty and grand corruption). Another

Bardhan, Pranab. 1997. Corruption and

limitation of this study is that it could

Development: A Review of Issues.

not probe into the specific impact of cor-

Journal of Economic Literature, XXXV

ruption on FDI driven by contrasting mo-

(September): 1320-46.

tives (e.g. market vs. asset-seeking FDI).

Beck, Paul & Michael Maker. 1986. A

FDI data classified by projects (reflecting

Comparison of Bribery and Bidding in

different motives) will be required to ad-

Thin Markets. Economic Letters, 20:

dress this issue. Finally, it is worthwhile

1-5.

to examine if the impact of corruption on

Benito, Gabriel & Geir Gripsrud. 1992.

FDI varies with the size of the company,

The Expansion of Foreign Direct

the project, or the nature of the industry

Investments: Discrete Rational Loca-

in question. Addressing those issues is

tion Choices or a Cultural Learning

an important and timely task.

Process? Journal of International Busi-

ness Studies, 3: 461-476.

NOTES

Billington, Nicholas. 1999. The Location

1. Various motives can be present si- of Foreign Direct Investment: An Em-

multaneously (Chudnovsky, Lopez and pirical Analysis. Applied Economics,

Porta, 1995) and blur the distinctions. Jan, 31: 65-80.

304 JOURNAL OF INTERNATIONAL BUSINESS STUDIES

This content downloaded from

202.125.103.103 on Mon, 28 Jun 2021 23:21:51 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

MOHSIN HABIB, LEON ZURAWICKI

Boatright, John. 2000. Ethics and the Economy. Boston: Harvard Business

Conduct of Business. Third Edition. School Publishing.

New Jersey: Prentice Hall. Drabek, Zdenek & Warren Payne. 1999.

Braguinsky, Serguey. 1996. Corruption The Impact of Transparency on For-

and Schumpeterian Growth in Differ- eign Direct Investment. Staff Working

ent Economic Environments. Contem- Paper ERAD-99-02, Geneva, World

porary Economic Policy, XIV, July: 14- Trade Organization.

25. Dunning, John. 1988. The Eclectic Para-

Brainard, Lael. 1997. An Empirical As- digm of International Production: A

sessment of the Proximity-Concentra- Restatement and Some Possible Exten-

tion Tradeoff Between Multinational sions. Journal of International Busi-

Sales and Trade. American Economic ness Studies, 19 (Spring): 1-31.

Review, 87: 520-544. . 1998. Location and the Multina-

Busse, Laurence, Noboru Ishikawa, Mor- tional Enterprise: A Neglected Factor?

gan Mitra, David Primmer, Kenneth Journal of International Business

Surjadinata & Tolga Yaveroglu. 1996. Studies, 29 (1): 45-66.

The Perception of Corruption: A Mar- Engwall, Lars & M. Wallenstal. 1988. Tit

ket Discipline Approach. Working Pa- for Tat in Small Steps: The Interna-

per, Emory University, Atlanta, GA. tionalization of Swedish Banks. Scan-

Caves, Richard. 1996. Multinational En- dinavian Journal of Management, 4 (3/

terprise and Economic Analysis. Sec- 4): 147-55.

ond Edition. Cambridge: Cambridge Ensign, Prescott. 1996. An Examination

University Press. of Foreign Direct Investment Theories

Chudnovsky, D., Andre Lopez, & Fer- and the Multinational Firm: A Busi-

nando Porta. 1995. New Foreign Direct ness/Economics Perspective. In M.

Investment in Argentina: Privatiza- Green & R. McNaughton, editors, The

tion, the Domestic Market, and Re- Location of Foreign Direct Investment,

gional Integration. In Agosin, Manuel, Avebury: Aldershot.

editor, Foreign Direct Investment in Ghemawat, Pankaj. 2001. Distance Still

Latin America. Washington, D.C.: In- Matters: The Hard Reality of Global

ter-American Development Bank and Expansion. Harvard Business Review,

the Johns Hopkins University Press. September: 3-11.

Coase, Ronald. 1979. Payola in Radio Gratchev, Mikhail. 2001. Forethought:

and Television Broadcasting. Journal Making the Most of Cultural Differ-

of Law and Economics, 22: 269-328. ences. Harvard Business Review,

Cyert, Richard & James March. 1963. A October: 2-3.

Behavioral Theory of the Firm. Engle- Grosse, Robert & Len Trevino. 1996. For-

wood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice Hall. eign Direct Investments in the United

Davidson, William. 1980. The Location States: An Analysis by Country of Or-

of Foreign Direct Investment Activity: igin. Journal of International Business

Country Characteristics and Experi- Studies, 27(1): 139-55.

ence Effects. Journal of InternationalGupta, Sanjeev, Hamid Davoodi & Rosa

Business Studies, 11(2): 9-22. Alonso-Terme. 1998. Does Corruption

Doz, Yves, J. Santos, & P. Williamson. Affect Income Inequality and Poverty?

2001. From Global to Metanational: IMF Working Paper, International

How Companies Win in the Knowledge

Monetary Fund, Washington D.C.

VOL. 33, No. 2, SECOND QUARTER, 2002 305

This content downloaded from

202.125.103.103 on Mon, 28 Jun 2021 23:21:51 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

CORRUPTION AND FDI

Hair, Joseph, Rolph Anderson, Ronald Jun, K. & H. Singh. 1996. The Determi-

Tatham & William Black. 1992. Multi- nants of Foreign Direct Investment in

variate Data Analysis. New York, NY:Developing Countries. Transnational

Macmillan. Corporation, 5(2): 67-105.

Hengeveld, W.A.B. 1996. World Dis- Kaufmann, Daniel & Shang-Jin Wei.

tance Tables, 1948-1974 [Computer 1999. Does "Grease Money" Speed Up

File]. Ann Arbor, MI: ICPSR. the Wheels of Commerce? Policy Re-

Hines, James. 1995. Forbidden Pay- search Working Paper 2254, The

ments: Foreign Bribery and American World Bank.

Business After 1977. Working Paper Kobrin, Steven. 1976. The Environmen-

5266, National Bureau of Economic tal Determinants of Foreign Direct

Research, Cambridge. Manufacturing Investment: An Ex-

Husted, Bryan. 1994. Honor Among post Empirical Analysis. Journal of In-

Thieves: A Transaction-Cost Interpre- ternational Business Studies, 7(1): 29-

tation of Corruption in the Third 42.

World. Business Ethics Quarterly, 4(1): Kogut, Bruce & Harbir Singh. 1988. The

17-27. Effect of National Culture on the

.1999. Wealth, Culture, and Cor- Choice of Entry Mode. Journal of Int

ruption. Journal of International Busi- national Business Studies, 19(3): 411-

ness Studies, 30(2): 339-360. 432

ILO. 2001. Yearbook of Labor Statistics. Lambsdorff, Johann. 1999. The Transpar-

International Labor Organization Pub- ency International Corruption Percep-

lications. tions Index 1999-Framework Docu-

IMF. 2000. International Financial Sta- ment, www.transparency.org.

tistics. (CD-ROM). Washington, LaPalombara,

D.C.: Joseph. 1994. Structur

International Monetary Fund. and Institutional Aspects of Corrup

Johanson, Jan & Jan-Erik Vahlne. 1977. tion. Social Research, 61(2): 325-350.

The Internationalization Process of the Leff, Nathaniel. 1964. Economic Devel-

Firm-A Model of Knowledge Devel- opment Through Bureaucratic Corrup-

opment and Increasing Foreign Market tion. American Behavioral Scientist,

Commitment. Journal of International 8-14.

Business Studies, 8 (Spring/Summer):Lien, Donald. 1986. A Note on Compet-

23-32. itive Bribery Games. Economic Letters,

.1990. The Mechanism of Interna- 22: 337-41.

tionalization. International Marketing Lui, Francis. 1985. An Equilibrium

Review, 7 (4): 11-24. Queuing Model of Bribery. Journal of

. & L-G. Mattson.1988. Internation- Political Economy, August: 760-781.

alization in Industrial Systems- Macrae, John. 1982. Underdevelopment

A Network Approach. In N. Hood & J-E. and the Economics of Corruption: A

Vahlne, editors, Strategies in Global Game Theory Approach. World Devel-

Corporation, London: Routledge. opment, 10 (8): 677-87.

. & F.Wiedersheim-Paul. 1975. Malta Conference. 1994. Report of the

The Internationalization of the Firm-

Netherlands Ministry of Justice. Pro-

Four Swedish Cases. Journal of Man-

ceedings of the 19th Conference of the

agement Studies, 8(1): 305-322. European Ministers of Justice. La Val-

306 JOURNAL OF INTERNATIONAL BUSINESS STUDIES

This content downloaded from

202.125.103.103 on Mon, 28 Jun 2021 23:21:51 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

MOHSIN HABIB, LEON ZURAWICKI

etta 14-15th of June, 1994. Strasbourg: Shleifer, Andrei & RobertVishny. 1993.

Council of Europe Publishing. Corruption. Quarterly Journal of Eco-

Mauro, Paolo. 1995. Corruption and nomics. 108(3): 599-617.

Growth. The Quarterly Journal of Eco- Studenmund, A. H. 1992. Using Eco-

nomics, August: 686-706. nometrics: A Practical Guide. New

Nigh, Douglas. 1986. Political Events York, NY: Harper Collins.

and the Foreign Direct Investment Tanzi, Vito. 1998. Corruption Around

Decision: An Empirical Examination. the World: Causes, Consequences,

Managerial and Decision Economics, Scope, and Cures. IMF Working Pape

7: 99-106.

WP/98/63, International Monetar

Nohria, Nitin & Carlos Garcia-Pont.

Fund, Washington, D.C.

1991. Global Strategic Linkages and

TI. 1999. www.transparency.org/

Industry Structure. Strategic Manage- documents/cpi.

ment Journal, 12 (Special Issue): 105-

Tse, David, Yigang Pan & Kevin Au.

24.

1997. How MNCs Choose Entry Modes

Nordstrom, Kjell & Jan-Erik Vahlne.

and Form Alliances: The China Expe-

1992. Is the Globe Shrinking? Psychic

Distance and the Establishment of

rience. Journal of International Busi-

ness Studies, 28(4): 779-805.

Swedish Sales Subsidiaries During the

Wei, Shang-Jin. 2000. How Taxing is

Last 100 years. International Trade

and Finance Association's Annual Corruption on International Investors?

The Review of Economics and Statis-

Conference, April 22-25, Laredo,

Texas.

tics, 82(4): 1-12.

OECD. 2000. International Direct Invest-

Wells, Louis & Alvin Wint. 2000. Mar-

ment Statistics Yearbook 1999, Paris. keting a Country: Promotion as a Tool

Political Risk Services, Inc. 2000. Politi- for Attracting Foreign Investment, Oc-

cal Risk Services Yearbook. Interna- casional Paper no. 13, Washington,

D.C.: World Bank.

tional Country Risk Guide.

Rashid, Salim. 1981. Public Utilities in Wheeler, David & Ashoka Mody. 1992.

International Investment Location

Egalitarian LDC's: The Role of Bribery

Decisions: The Case of U.S. Firms.

in Achieving Pareto Efficiency. Kyklos,

34: 448-60. Journal of International Economics

Rose-Ackerman, Susan. 1975. The Eco- 33: 57-76.

nomics of Corruption. Journal of Pub- World Competitiveness Yearbook. 200

lic Economics, 4: 187-203. Lausanne: Institute for Managemen

Schniederjans, Marc. 1999. International Development.

Facility Acquisition and Locational WIR. 2001. World Investment Repor

Analysis. Westport, CT: Quorum Books. 2001. Geneva: United Nations

VOL. 33, No. 2, SECOND QUARTER, 2002 307

This content downloaded from

202.125.103.103 on Mon, 28 Jun 2021 23:21:51 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

You might also like

- Contemporary Trends in Trade-Based Money Laundering: 1st Edition, February 2024From EverandContemporary Trends in Trade-Based Money Laundering: 1st Edition, February 2024No ratings yet

- Nation-States and the Multinational Corporation: A Political Economy of Foreign Direct InvestmentFrom EverandNation-States and the Multinational Corporation: A Political Economy of Foreign Direct InvestmentNo ratings yet

- 1.the Effect of Corruption On Japanese ForDocument14 pages1.the Effect of Corruption On Japanese ForAzan RasheedNo ratings yet

- Who Cares About Corruption?: Alvaro Cuervo-CazurraDocument16 pagesWho Cares About Corruption?: Alvaro Cuervo-CazurraRESMENNo ratings yet

- Cuervo-Cazurra - Who Cares About Corruption PDFDocument17 pagesCuervo-Cazurra - Who Cares About Corruption PDFalicorpanaoNo ratings yet

- 1 s2.0 S017626801200002X MainDocument11 pages1 s2.0 S017626801200002X MainDefrianto Wahyu Putra PratamaNo ratings yet

- 1-4-1aye Mengistu AlemuDocument69 pages1-4-1aye Mengistu AlemuSean O'PryNo ratings yet

- Effects of Corruption On FDI Inflow in Asian EconomiesDocument26 pagesEffects of Corruption On FDI Inflow in Asian EconomiesGarima DhirNo ratings yet

- Cielik 2018Document13 pagesCielik 2018salman samirNo ratings yet

- OECD Global Forum on International InvestmentDocument35 pagesOECD Global Forum on International InvestmentteremillansNo ratings yet

- 1 s2.0 S1090951613000643 MainDocument11 pages1 s2.0 S1090951613000643 Maindasniel3No ratings yet

- Corruption and FDIDocument10 pagesCorruption and FDIShuchi Goel100% (1)

- FDI Effects on Host EconomiesDocument13 pagesFDI Effects on Host Economiesthi100% (1)

- Corruption and Fdi InflowsDocument2 pagesCorruption and Fdi InflowsAyodele SokefunNo ratings yet

- Bureaucratic Corruption, Mnes and Fdi: Andreas Johnson Co-Author: Tobias DahlströmDocument23 pagesBureaucratic Corruption, Mnes and Fdi: Andreas Johnson Co-Author: Tobias Dahlströmpetra1981No ratings yet

- Entry Modes of MNCDocument17 pagesEntry Modes of MNCPrateek Jain100% (1)

- Institutional Reform Foreign Direct Investment and European Transition EconomiesDocument27 pagesInstitutional Reform Foreign Direct Investment and European Transition Economiesimaneamani993No ratings yet

- Corruption's Impact on Foreign Direct InvestmentDocument21 pagesCorruption's Impact on Foreign Direct InvestmentAldina SafiraNo ratings yet

- Corruption and Economic Crime Share Common Characteristics and DriversDocument18 pagesCorruption and Economic Crime Share Common Characteristics and DriverssaraNo ratings yet

- International Business Research PaperDocument45 pagesInternational Business Research PaperRaghav SrivastavaNo ratings yet

- Export of GoodsDocument8 pagesExport of GoodsAli RazaNo ratings yet

- FDI Technology Spillovers and Spatial Diffusion in The People's Republic of ChinaDocument48 pagesFDI Technology Spillovers and Spatial Diffusion in The People's Republic of ChinaAsian Development BankNo ratings yet

- Thick As Thieves Ajcp Panao2021Document20 pagesThick As Thieves Ajcp Panao2021Alicor PanaoNo ratings yet

- Pap 3Document19 pagesPap 3AquaTunisNo ratings yet

- New Evidence On The Determinants of Foreign Direct Investments in Emerging Markets A Panel Data ApproachDocument8 pagesNew Evidence On The Determinants of Foreign Direct Investments in Emerging Markets A Panel Data ApproachEditor IJTSRDNo ratings yet

- 11.the Effects of Corruption On Foreign Direct Investment Inflows Some Empirical Evidence From Less Developed CountriesDocument7 pages11.the Effects of Corruption On Foreign Direct Investment Inflows Some Empirical Evidence From Less Developed CountriesAnand SharmaNo ratings yet

- FDI and Economic Growth: The Role of Local Financial MarketsDocument52 pagesFDI and Economic Growth: The Role of Local Financial MarketsUmair MuzammilNo ratings yet

- Doh Et Al Corruption AME 2003Document15 pagesDoh Et Al Corruption AME 2003Violeta MijatovicNo ratings yet

- فساد مالي 5Document11 pagesفساد مالي 5ali ghaniNo ratings yet

- Chapter 2Document39 pagesChapter 2Witness Wii MujoroNo ratings yet

- Foreign Direct Investment and Growth: L. Alfaro, M.S. JohnsonDocument11 pagesForeign Direct Investment and Growth: L. Alfaro, M.S. JohnsonMCINo ratings yet

- Corruption and Foreign Direct Investment in East Asia and South Asia An Econometric StudyDocument13 pagesCorruption and Foreign Direct Investment in East Asia and South Asia An Econometric StudyAnand SharmaNo ratings yet

- Corruption and The Investment Climate in NigeriaDocument17 pagesCorruption and The Investment Climate in NigeriaiisteNo ratings yet

- The Impact of Corruption On Economic Growth in Developing Countries and A Comparative Analysis of Corruption Measurement IndicatorsDocument31 pagesThe Impact of Corruption On Economic Growth in Developing Countries and A Comparative Analysis of Corruption Measurement IndicatorsTheresiana DeboraNo ratings yet

- Assessment 1 M1Document5 pagesAssessment 1 M1ZACK ELALTONo ratings yet

- The Quality of Institutions and Foreign Direct InvestmentDocument28 pagesThe Quality of Institutions and Foreign Direct InvestmentNoor Preet KaurNo ratings yet

- Regional Intra-And Inter-Industry Externalities From Foreign Direct InvestmentDocument28 pagesRegional Intra-And Inter-Industry Externalities From Foreign Direct InvestmentAdrianaBleahuNo ratings yet

- Foreign Direct Investment, Productivity, and Country Growth, An OverviewDocument18 pagesForeign Direct Investment, Productivity, and Country Growth, An OverviewAna Letícia Palacio HortolaniNo ratings yet

- Kaymak CorruptionEmergingMarkets 2015Document22 pagesKaymak CorruptionEmergingMarkets 2015dasniel3No ratings yet

- Presentation at The 9 International Conference On Macroeconomic Analysis and International Finance May 2005 Rethymno, CreteDocument14 pagesPresentation at The 9 International Conference On Macroeconomic Analysis and International Finance May 2005 Rethymno, CreteHenrique SanchezNo ratings yet

- Dissertation - Literature Review and MethodologyDocument20 pagesDissertation - Literature Review and Methodologyshakila segavanNo ratings yet

- Presentation at JVEC's Meeting 29 May 2004 "Locational Determinants of Foreign Direct Investment: The Case of Vietnam"Document31 pagesPresentation at JVEC's Meeting 29 May 2004 "Locational Determinants of Foreign Direct Investment: The Case of Vietnam"Trần Thị Kim NhungNo ratings yet

- Fdi and The Effects On Society PDFDocument4 pagesFdi and The Effects On Society PDFsamsonNo ratings yet

- Assessment Feedback Form: Ushakov 3 9 Denis Bs10068@qmul - Ac.ukDocument6 pagesAssessment Feedback Form: Ushakov 3 9 Denis Bs10068@qmul - Ac.ukDenis UshakovNo ratings yet

- DissertationDocument17 pagesDissertationshakila segavanNo ratings yet

- 4 Conference Paper EDAMBA52Seetanah - Matadeen - Fauzel - Gopal (Crowding in or Out) - 2Document9 pages4 Conference Paper EDAMBA52Seetanah - Matadeen - Fauzel - Gopal (Crowding in or Out) - 2Ahmad AL-Nawaserh (Hamedo)No ratings yet

- 1 Running Head: Corruption Behaviors and Multinational OrganizationDocument8 pages1 Running Head: Corruption Behaviors and Multinational OrganizationJessyNo ratings yet

- Ratification Counts US Investment Treaties and FDI Flows Into Developing CountriesDocument31 pagesRatification Counts US Investment Treaties and FDI Flows Into Developing CountriesAnand SharmaNo ratings yet

- Determinants of FDI in ZambiaDocument14 pagesDeterminants of FDI in ZambiaBadr AdilNo ratings yet

- Globalization and Developing Countries: Foreign Direct Investment and Growth and Sustainable Human DevelopmentDocument35 pagesGlobalization and Developing Countries: Foreign Direct Investment and Growth and Sustainable Human DevelopmentOradeeNo ratings yet

- FDICapital Formatted 20170922 Final WDocument32 pagesFDICapital Formatted 20170922 Final Wrishitmughalempire23No ratings yet

- Kwok-Reeb2000 Article InternationalizationAndFirmRisDocument19 pagesKwok-Reeb2000 Article InternationalizationAndFirmRisJuliaNo ratings yet

- A Study On The Moderating Role of National Absorptive Capacity Between Institutional Quality and FDI Inflow Evidence From Developing CountriesDocument23 pagesA Study On The Moderating Role of National Absorptive Capacity Between Institutional Quality and FDI Inflow Evidence From Developing CountriesleonardoNo ratings yet

- 532-Article Text-1106-1-10-20190527Document13 pages532-Article Text-1106-1-10-20190527Md FarmanNo ratings yet

- Effect of Corruption On Foreign Direct Investment Inflows in NigeriaDocument13 pagesEffect of Corruption On Foreign Direct Investment Inflows in NigeriaMd FarmanNo ratings yet

- Economics Assignemnt On FdiDocument12 pagesEconomics Assignemnt On FdiAndy ChilaNo ratings yet

- Economics of CorruptionDocument64 pagesEconomics of CorruptionTJ Palanca100% (1)

- Foreign Direct Investment and Growth: Does The Sector Matter?Document32 pagesForeign Direct Investment and Growth: Does The Sector Matter?jigarsampatNo ratings yet

- Greenfield Foreign Direct Investment and Mergers and Acquisitions: Feedback and Macroeconomic EffectsDocument31 pagesGreenfield Foreign Direct Investment and Mergers and Acquisitions: Feedback and Macroeconomic EffectsAli AliNo ratings yet

- Foreign Direct Investment Theories: An Overview of The Main FDI TheoriesDocument17 pagesForeign Direct Investment Theories: An Overview of The Main FDI TheoriesPooja MaliNo ratings yet

- Corruption and The Crisis of DemocracyDocument19 pagesCorruption and The Crisis of DemocracysaraNo ratings yet

- Coping With Corruption in Foreign MarketsDocument17 pagesCoping With Corruption in Foreign MarketssaraNo ratings yet

- Corruption and Economic Crime Share Common Characteristics and DriversDocument18 pagesCorruption and Economic Crime Share Common Characteristics and DriverssaraNo ratings yet

- Union Carbide Vs MNL Digest v2Document2 pagesUnion Carbide Vs MNL Digest v2saraNo ratings yet

- Controlling the Global Corruption Epidemic: A Foreign Policy PriorityDocument20 pagesControlling the Global Corruption Epidemic: A Foreign Policy PrioritysaraNo ratings yet

- 2019 Bar Examinations Civil Law SyllabusDocument4 pages2019 Bar Examinations Civil Law SyllabusclarizzzNo ratings yet

- Aristotle's Views on Corruption and the Public InterestDocument13 pagesAristotle's Views on Corruption and the Public InterestsaraNo ratings yet

- Business Without Bribery - Analyzing The Future of Enforcement For TheDocument21 pagesBusiness Without Bribery - Analyzing The Future of Enforcement For ThesaraNo ratings yet

- 2019 Bar Examinations Civil Law SyllabusDocument4 pages2019 Bar Examinations Civil Law SyllabusclarizzzNo ratings yet

- China's Deliberate Non-Enforcement of Foreign CorruptionDocument27 pagesChina's Deliberate Non-Enforcement of Foreign CorruptionsaraNo ratings yet

- Advance Paper Corp. vs. Arma TradersDocument6 pagesAdvance Paper Corp. vs. Arma TraderssaraNo ratings yet

- E.I. Dupont vs. FranciscoDocument12 pagesE.I. Dupont vs. Franciscosara0% (1)

- Articles of Incorporation and by-laws explainedDocument4 pagesArticles of Incorporation and by-laws explainedsaraNo ratings yet

- Ang vs. American Steamship Agencies Prescription in Carriage of Goods by Sea CasesDocument2 pagesAng vs. American Steamship Agencies Prescription in Carriage of Goods by Sea CasessaraNo ratings yet

- Mercantile LAW: I. Letters of Credit and Trust ReceiptsDocument4 pagesMercantile LAW: I. Letters of Credit and Trust ReceiptsclarizzzNo ratings yet

- Palting vs. San Jose PetroleumDocument5 pagesPalting vs. San Jose PetroleumsaraNo ratings yet

- G.1 Filipinas Compania vs. ChristernDocument1 pageG.1 Filipinas Compania vs. ChristernsaraNo ratings yet

- Yujuico vs. QuiambaoDocument5 pagesYujuico vs. QuiambaosaraNo ratings yet

- Palting vs. San Jose PetroleumDocument5 pagesPalting vs. San Jose PetroleumsaraNo ratings yet

- Yujuico vs. QuiambaoDocument5 pagesYujuico vs. QuiambaosaraNo ratings yet

- Expropriation and Foreclosure ReviewDocument13 pagesExpropriation and Foreclosure ReviewsaraNo ratings yet

- JOSE DE BORJA, Petitioner, Servillano Platon and Francisco de Borja, Respondents. Bocobo, J.Document32 pagesJOSE DE BORJA, Petitioner, Servillano Platon and Francisco de Borja, Respondents. Bocobo, J.saraNo ratings yet

- Filipinas Compania vs. ChristernDocument2 pagesFilipinas Compania vs. ChristernsaraNo ratings yet

- Yujuico vs. QuiambaoDocument2 pagesYujuico vs. QuiambaosaraNo ratings yet

- Conflict of Laws Syllabus 2017Document2 pagesConflict of Laws Syllabus 2017sara100% (1)

- Nissan Vs UnitedDocument2 pagesNissan Vs UnitedsaraNo ratings yet

- 1 Romeo Sison Vs PeopleDocument3 pages1 Romeo Sison Vs PeopleAnne Ausente BerjaNo ratings yet

- Alano Vs ECCDocument2 pagesAlano Vs ECCsaraNo ratings yet

- Ang vs. American Steamship Agencies Prescription in Carriage of Goods by Sea CasesDocument2 pagesAng vs. American Steamship Agencies Prescription in Carriage of Goods by Sea CasessaraNo ratings yet

- CH 02Document60 pagesCH 02kevin echiverriNo ratings yet

- Foreign Trade Multiplier: Meaning, Effects and CriticismsDocument6 pagesForeign Trade Multiplier: Meaning, Effects and CriticismsDONALD DHASNo ratings yet

- Rly Allowances BookDocument146 pagesRly Allowances Bookshivshanker tiwariNo ratings yet

- Impact of The UKVFTA On The Export of Vietnam's Textile and Garment To The UKDocument37 pagesImpact of The UKVFTA On The Export of Vietnam's Textile and Garment To The UKThu Hai LeNo ratings yet

- Rivera, Karen Diane C. - GS REPORTDocument18 pagesRivera, Karen Diane C. - GS REPORTKaren Diane Chua RiveraNo ratings yet

- PDM YumbeDocument18 pagesPDM YumbeAkimu sijaliNo ratings yet

- Retail BankingDocument2 pagesRetail BankingRajni KumariNo ratings yet

- (Routledge Explorations in Economic History) Helen Paul - The South Sea Bubble - An Economic History of Its Origins and Consequences (2010, Routledge) PDFDocument176 pages(Routledge Explorations in Economic History) Helen Paul - The South Sea Bubble - An Economic History of Its Origins and Consequences (2010, Routledge) PDFАрсен ТирчикNo ratings yet

- 02.186 - F - Satr-Nde-2008 Revised (003) 010817 SS JointsDocument2 pages02.186 - F - Satr-Nde-2008 Revised (003) 010817 SS JointsMAZHARULNo ratings yet

- CRISIL Research NBFC Report 2020Document18 pagesCRISIL Research NBFC Report 2020Vishwa KNo ratings yet

- Cambridge International AS & A Level: ECONOMICS 9708/42Document4 pagesCambridge International AS & A Level: ECONOMICS 9708/42MoynaNo ratings yet

- PS Form 3877 - Firm Mailing For Accountable MailDocument1 pagePS Form 3877 - Firm Mailing For Accountable MailLaLa Banks100% (1)

- Contract To Sell LansanganDocument2 pagesContract To Sell LansanganTet BuanNo ratings yet

- Competitive Industrial Performance Index - 2020Document2 pagesCompetitive Industrial Performance Index - 2020Hamit OzmanNo ratings yet

- BS PP1 QN F3 2021 Term 3Document8 pagesBS PP1 QN F3 2021 Term 3EVANSNo ratings yet

- Rural Banking & Financial Institutions in India: Free E-BookDocument8 pagesRural Banking & Financial Institutions in India: Free E-BookPrasun KumarNo ratings yet

- High-tech design and innovations for maximum productivityDocument40 pagesHigh-tech design and innovations for maximum productivityvige50% (2)

- Chin Hin - Quarter Announcement Q4 2021 (Final)Document31 pagesChin Hin - Quarter Announcement Q4 2021 (Final)KentNo ratings yet

- Ch2.1. Optimal ChoiceDocument92 pagesCh2.1. Optimal ChoiceNguyễn Thị Anh ĐàiNo ratings yet

- RBI Keeps Key Policy Rates On HoldDocument15 pagesRBI Keeps Key Policy Rates On HoldNDTVNo ratings yet

- Brijesh - Akshay-RamratanDocument19 pagesBrijesh - Akshay-RamratanshubhamNo ratings yet

- Partnership and Corporation Accounting ReviewerDocument9 pagesPartnership and Corporation Accounting ReviewerMarielle ViolandaNo ratings yet

- The Great Divergence Debate: Structural vs Conjunctural ExplanationsDocument19 pagesThe Great Divergence Debate: Structural vs Conjunctural Explanations8016 Prachi PriyaNo ratings yet

- Annex A Enhanced CPF Housing Grant (EHG) Table A1: EHG StructureDocument1 pageAnnex A Enhanced CPF Housing Grant (EHG) Table A1: EHG StructureFidoNo ratings yet

- Council Tax 2019-20 GuideDocument2 pagesCouncil Tax 2019-20 GuideSteven HamiltonNo ratings yet

- MCQ Problems On Marginal Costing: Q.1 (D) (V) AnsDocument1 pageMCQ Problems On Marginal Costing: Q.1 (D) (V) AnsHasim SaiyedNo ratings yet

- Thomas 05.31.23Document32 pagesThomas 05.31.23Deuntae ThomasNo ratings yet

- MandA UptickDocument3 pagesMandA UptickGordMillerNo ratings yet

- Understand The Impact of Quantity Discounts On Lot Size and Cycle InventoryDocument1 pageUnderstand The Impact of Quantity Discounts On Lot Size and Cycle InventorySreekumar Rajendrababu100% (2)

- Eco RevampDocument21 pagesEco RevampCriese lavileNo ratings yet