Professional Documents

Culture Documents

The English Version of The Chinese Personality Assessment Inventory

Uploaded by

Tarek SadekOriginal Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

The English Version of The Chinese Personality Assessment Inventory

Uploaded by

Tarek SadekCopyright:

Available Formats

10.

1177/0022022103254170 ARTICLE

JOURNAL OF CROSS-CULTURAL PSYCHOLOGY

Cheung et al. / ENGLISH CPAI

THE ENGLISH VERSION OF THE

CHINESE PERSONALITY ASSESSMENT INVENTORY

FANNY M. CHEUNG

SHU FAI CHEUNG

Chinese University of Hong Kong

KWOK LEUNG

City University of Hong Kong

COLLEEN WARD

Victoria University of Wellington

FREDERICK LEONG

Ohio State University

The article examines the structure of the Chinese Personality Assessment Inventory (CPAI), an indigenous

Chinese assessment instrument, in two English-speaking samples. In Study 1, the English version of the

CPAI was developed and administered to a sample of 675 Singaporean Chinese. Factor analysis showed that

the factor structure of the English version CPAI was similar to the structure of the original Chinese version in

the normative sample. Joint factor analysis of the English version CPAI and the NEO-FFI showed that the

Interpersonal Relatedness factor of the CPAI was not covered by the NEO-FFI, whereas the Openness

domain of the NEO-FFI was not covered by the CPAI. In Study 2, the English version CPAI was adminis-

tered to a Caucasian American sample. The factor structure was similar to those of the Singaporean sample

and Chinese normative sample. The implications of administering the CPAI in non-Chinese cultures are dis-

cussed.

Keywords: personality; Chinese Personality Assessment Inventory; cross-cultural personality assessment;

five-factor model

In the early development of psychology in Asian countries, psychologists relied on the

adoption of Western personality assessment instruments. For example, in the early 1970s,

the Minnesota Multiphasic Personality Inventory (MMPI) and the Eysenck Personality

Questionnaire (EPQ) have been translated and used in clinical settings in Hong Kong, India,

Japan, and Taiwan (Cheung, in press; Thakur & Thakur, 1973). This strategy is called the

“imposed etic” strategy (Berry, 1989; Church & Lonner, 1998). In this strategy, assessment

instruments developed in one culture are adopted in another culture, assuming that the under-

lying theories and constructs are universal.

In the 1990s, the development of cross-cultural study of personality psychology has led to

questions about the appropriateness of using translated personality tests that are developed in

the Western countries. The imposed-etic strategy may “optimize the chances of finding

cross-cultural comparability and exclude culture-specific dimensions” (Church & Lonner,

AUTHORS’NOTE: This project was partially supported by the Hong Kong Government Research Grants Council Earmarked Grant

Project CUHK4333/00H and Direct Grant no. 2020662 of the Chinese University of Hong Kong. Correspondence concerning this

article and permission for the use of the Chinese Personality Assessment Inventory should be addressed to Fanny M. Cheung,

Department of Psychology, The Chinese University of Hong Kong, Hong Kong; e-mail: fmcheung@cuhk.edu.hk.

JOURNAL OF CROSS-CULTURAL PSYCHOLOGY, Vol. 34 No. 4, July 2003 433-452

DOI: 10.1177/0022022103254170

© 2003 Western Washington University

433

Downloaded from jcc.sagepub.com at University of Ulster Library on March 6, 2015

434 JOURNAL OF CROSS-CULTURAL PSYCHOLOGY

1998, p. 36). Moreover, the specific values and tendencies of the Western culture may

unknowingly lead to the de-emphasis or omission of some universal constructs. For exam-

ple, Ellemers, Spears, and Doosje (2002) argued that the individualistic culture of Western

societies might have led to the dominant adoption of personal self and personal identity as the

explanatory framework to explain group process and intergroup relations, although substan-

tial empirical findings also supported the importance of social identity in understanding

group dynamic. It is true that imposing a culture’s instruments and constructs onto other cul-

tures does not preclude the discovery of universal constructs. However, this strategy may

lead to a biased picture based on a selective subset of universal constructs. Consequently,

some psychologists in non-Western countries began to develop indigenous personality

instruments (e.g., Cheung & Leung, 1998). The Chinese Personality Assessment Inventory

(CPAI), an indigenous personality test developed by Chinese psychologists in mainland

China and Hong Kong, provides a means to complement the predominance of Western

instruments.

THE CPAI

The CPAI was developed as an indigenous instrument to measure Chinese personality

(Cheung, Leung, Fan, et al., 1996). A combined etic-emic approach was adopted in the

development of the CPAI. In addition to personality traits that are found in English-language

personality tests (i.e., the etics), the CPAI includes personality traits that are not found in

these tests but are considered to be important to the Chinese (i.e., the emics). The CPAI con-

sists of 22 personality scales and 12 clinical scales (one scale is used both as a personality

scale and a clinical scale). The CPAI was standardized on a representative sample of Chinese

people in the People’s Republic of China and in Hong Kong. Four personality factors are

extracted from the personality scales of the CPAI, namely Dependability, Social Potency,

Individualism, and Interpersonal Relatedness. To assess the validity of a protocol, the CPAI

also has three validity scales, namely the Infrequency Scale, Response Consistency Index,

and Good Impression Scale. The Infrequency Scale consists of 16 items that have a low

endorsement rate in the normative sample. The Response Consistency Index consists of

three pairs of repeated items and five pairs of reversed items. A low score on the Response

Consistency Index suggests that a respondent answered in an inconsistent way. The Good

Impression Scale consists of 12 items used to identify respondents who tend to fake well. For

a full description of the development of the CPAI, please refer to Cheung, Leung, Fan, et al.’s

1996 article.

In a subsequent study, Cheung and colleagues (Cheung, Leung, Zhang, et al., 2001) com-

pared the CPAI with the NEO-PI-R, an instrument that is based on the Western five-factor

model (Costa & McCrae, 1992). The five-factor model, originally developed in the Western

culture, posited the existence of five universal domains (the so-called Big Five dimensions)

that characterize personality, namely, Neuroticism, Extraversion, Openness, Agreeableness,

and Conscientiousness. Three of the CPAI personality factors (Dependability, Social

Potency, and Individualism) converged with the Neuroticism, Extraversion, and Agreeable-

ness factors of the NEO-PI-R (Costa & McCrae, 1992) in a joint factor analysis (Cheung,

Leung, Zhang, et al., 2001). The Interpersonal Relatedness factor on the CPAI was not

loaded by any of the NEO-PI-R facets, and none of the CPAI scales loaded on the Openness

facet of the NEO-PI-R. These results were confirmed in two independent samples reported in

Cheung, Leung, Zhang, et al. (2001).

Downloaded from jcc.sagepub.com at University of Ulster Library on March 6, 2015

Cheung et al. / ENGLISH CPAI 435

The FFM has been examined in several other cultures, including Japanese, Korean, and

Chinese (for a review, see McCrae & Costa, 1997; McCrae, Costa, Del-Pilar, Rolland, &

Parker, 1998). For Chinese culture in particular, the studies reviewed by McCrae, Costa, and

Yik (1996) suggested that the five factors could be identified in several Chinese samples.

McCrae, Costa, and Yik claimed that the FFM “can be said to summarize aspects of Chinese

personality structure that are universal” (p. 198). However, despite the universality of the

FFM, it is still possible that the Chinese people “cut the social-perceptual world differently”

(Yik & Bond, 1993, p. 92). This possibility is supported by the identification of a unique

Interpersonal Relatedness factor in the aforementioned joint factor analysis of NEO-PI-R

and CPAI (Cheung, Leung, Zhang, et al., 2001).

The Interpersonal Relatedness factor of the CPAI consists of scales that measure the

emphasis on interdependent interpersonal relationship, which is characteristic of the Chi-

nese culture. The Interpersonal Relatedness factor was found to be a useful predictor of

behaviors among the Chinese, including filial piety, trust, persuasiveness, and communica-

tion (Sun & Bond, 2000; Zhang, 1997; Zhang & Bond, 1998). Cheung, Leung, Zhang, et al.

(2001) showed that the Interpersonal Relatedness factor might also be relevant to popula-

tions outside of China as well as to non-Chinese populations.

The CPAI provides a means to find cultural differences as well as similarities in personal-

ity between an imported Western instrument and an indigenous instrument in the Chinese

culture (Cheung, Leung, Zhang, et al., 2001). For example, it provides a measure of the inter-

dependent domains of personality and person perception for non-Chinese. It has been argued

that the conception of personality in Western cultures is more independent oriented, whereas

that of the Asian cultures is more interdependent oriented (e.g., Markus & Kitayama, 1998).

However, as implied by Yang and Bond (1990, p. 1094), imported and indigenous instru-

ments may have different theorizations of the same culture and are, at the same time, both

useful.

To extend the findings of jointly analyzing the CPAI and NEO-PI-R in a Chinese sample,

the next step is to administer the CPAI and Western instruments to non-Chinese cultures.

This is analogous to what Van de Vijver and Leung (1997) called the convergence approach.

This approach can provide further support to the universality of a construct if this construct

was found in both cultures irrespective of whether an indigenous or an imported instrument

was used. Moreover, it would help to expand the applicability of an indigenous instrument.

For example, if the Interpersonal Relatedness factor was found not just in China and Hong

Kong, then it would suggest that the Interpersonal Relatedness factor was not specific to the

Chinese context. As suggested by Church (2001), one question related to indigenous mea-

sures is whether “they contribute incremental validity beyond that provided by imported

measures” (p. 987).

In the two studies presented below, we administered the CPAI to locations other than

mainland China and Hong Kong, including Chinese in Singapore and Caucasians in the

United States. In Study 1, the English version of the CPAI was developed and administered to

a sample of Singaporean Chinese of diverse demographic background. This step was neces-

sary to ensure that the English instrument had structural equivalence with the Chinese CPAI

in a similar culture. We also administered the abridged version of the NEO-PI-R, the NEO-

FFI, to the Singaporean sample. We compared the structure of the English version of the

CPAI in the Chinese to that of the Chinese CPAI in the standardization sample (Cheung,

Leung, Fan, et al., 1996). We also compared the joint factor analysis of the CPAI and the

NEO-FFI. In Study 2, we presented a preliminary validation of the English version of the

Downloaded from jcc.sagepub.com at University of Ulster Library on March 6, 2015

436 JOURNAL OF CROSS-CULTURAL PSYCHOLOGY

CPAI in a Caucasian American sample. The factor structures of the CPAI in the Caucasian

sample and the Chinese standardization sample were compared. We discussed the potential

contributions of applying the CPAI in non-Chinese cultures.

STUDY 1

In Study 1, the Singaporean Chinese were selected as the population to examine the struc-

ture of the English CPAI. English is the dominant language in Singapore. More than 70% of

Singaporean are literate in English (Singapore Department of Statistics, 2001b), and English

is one of four official languages of the country, as well as the language of education, law, and

politics. From 1995 to 2000, approximately 77% of the Singapore population consist of eth-

nic Chinese (Singapore Department of Statistics, 2001a). Given the similarity in cultural

contexts, we expect to find similar personality structures for the CPAI.

We administered the English versions of the CPAI and the NEO-FFI to a Chinese sample

in Singapore to examine whether we could obtain results similar to that reported by Cheung,

Leung, Zhang, et al. (2001). This can provide further support for the structural equivalence

between the English and Chinese versions of the CPAI. The objectives of Study 1 were two-

fold. First, we attempted to replicate the factor structure of the English version of the CPAI.

Second, we attempted to replicate the joint factor structure of the English CPAI personality

scales and the NEO-FFI scales, an abridged version of the NEO-PI-R (Costa & McCrae,

1992), in another Chinese cultural context. Specifically, the study examined whether the

Interpersonal Relatedness factor stood out as a unique factor of the English CPAI not covered

by the NEO-FFI, and Openness as a unique factor of NEO-FFI not covered by the English

CPAI.

METHOD

PARTICIPANTS

A quota sample of Singapore ethnic Chinese approximating the demographic back-

ground of the population was recruited. Using the CPAI standard screening criteria, partici-

pants with a Response Consistency Index score less than 4 (out of a maximum of 8), an Infre-

quency Scale score greater than 4 (out of a maximum of 16), or had 30 or more items

unanswered were classified as invalid cases and deleted from subsequent analyses. The num-

ber of valid cases retained was 531. The age of the respondents ranged from 18 to 73 (M =

33.23, SD = 12.81). There were 238 males and 294 females, with the remaining cases

unknown. Approximately 40% of the participants had at least undergraduate level education,

whereas 38.5% of the participants had education levels ranging from primary school to sec-

ondary school. The percentage of respondents having achieved the level of technical institute

or professional diploma was 17.1%. The remaining cases were either not reported or

unclassified.

Downloaded from jcc.sagepub.com at University of Ulster Library on March 6, 2015

Cheung et al. / ENGLISH CPAI 437

INSTRUMENTS

CPAI. The English version of the CPAI used in this study was based on a preliminary Eng-

lish version developed as part of the doctoral dissertation of Gan (1998). The back-translation

technique outlined by Brislin (1970) was used to develop the English CPAI. This procedure

was analogous to the procedure commonly used to translate Western instruments into Chi-

nese. First, the 22 personality scales and three validity scales of the original Chinese CPAI

(Cheung, Leung, Fan, et al., 1996) were translated into English by three bilingual research

assistants specializing in translation, one a native English speaker. Special attention was paid

to idiomatic items, and equivalent meaning was ascertained in the English version. The initial

English items were then back translated into Chinese. The original and the back-translated

Chinese items were compared for any major distortion in meaning. The process was repeated

to ensure the conceptual equivalence between the Chinese and English items (Cheung,

1985). A partial list of the English CPAI scales was administered to a multiethnic, Hawaiian

undergraduate sample in Gan’s (1998) study. The results were used to further refine the Eng-

lish items used in the present study. The median Cronbach’s alpha of the 22 English personal-

ity scales was .67, about the same magnitude as the median Cronbach’s alpha in the Chinese

normative sample.

NEO-FFI. The NEO-FFI is an abridged version of the NEO-PI-R (Costa & McCrae,

1992), which measures the Big Five of the five-factor model: Neuroticism (N), Extraversion

(E), Openness (O), Agreeableness (A), and Conscientiousness (C). The NEO-FFI measures

the domain scores of the Big Five. Each domain is represented by 12 items. The total number

of items is 60. The Cronbach’s alphas for the present study ranged from .58 for Openness to

.83 for Conscientiousness.

PROCEDURES

About 30 students were asked to recruit, through personal contacts and snowballing

method, respondents that roughly fit the demographics of the Singapore population in terms

of gender and age. The students were asked to ensure that respondents had adequate lan-

guage ability to complete the questionnaire in English. After being giving a standard instruc-

tion, the respondents filled in the questionnaires on their own and returned it to the students

when completed.

ANALYSIS

Principal component analysis with varimax rotation was conducted separately for the

English CPAI and the NEO-FFI scales. In this study, principal component analysis was pre-

ferred to confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) in examining personality structures (McCrae,

Zonderman, Costa, Bond, & Paunonen, 1996). First, there is no theoretical reason to assume

strictly that all personality traits or scales load on only single factors. Moreover, the second-

ary loadings in a factor structure can be meaningful and replicable. Third, in the case of

NEO-PI-R, McCrae, Costa, and Yik (1996) argued that even though a limited number of sec-

ondary loadings can be specified in CFA, the most appropriate model should be a model in

which all traits or scales are allowed to load on all the factors. Despite the lack of goodness-

Downloaded from jcc.sagepub.com at University of Ulster Library on March 6, 2015

438 JOURNAL OF CROSS-CULTURAL PSYCHOLOGY

of-fit indices as in the CFA, McCrae and colleagues suggested that the degree of replication

could be evaluated by orthogonal Procrustes rotation and congruence coefficients. In

orthogonal Procrustes rotation, the initial factor structure is rotated orthogonally as close as

possible to a target structure (Mulaik, 1972). The factor congruence coefficients are com-

puted to quantify the degree that a factor structure is replicated (Wrigley & Neuhaus, 1955).

Finally, we are comparing the present results with those obtained in the Cheung, Leung,

Zhang, et al. (2001) study, which used the same methods of analysis.

The English CPAI was factor analyzed at the scale level. Following the procedures in

Cheung, Leung, Zhang, et al. (2001), three subscales of four items each were formed for each

NEO-FFI domain. The 15 NEO-FFI subscales were then factor analyzed in an attempt to

recover the five-factor model. For the English CPAI, orthogonal Procrustes rotation was per-

formed using as target the standardization sample of 2,444 Chinese respondents in China

and Hong Kong SAR (Cheung, Leung, Zhang, et al., 2001). Orthogonal Procrustes rotation

was used to test replicability. Factor congruence coefficients were computed to compare the

English CPAI structure with the structure of the Chinese CPAI. The 22 English CPAI person-

ality scales and the 15 NEO-FFI subscales were then jointly factor analyzed by principal

component analysis.

RESULTS

FACTOR STRUCTURE OF THE ENGLISH CPAI

Because the goal of the analysis was to compare the structure of the English CPAI with

that of the Chinese CPAI in the standardization sample, we chose a four-factor solution in the

principal component analysis. Procrustes rotation was performed with the factor structure

reported in the Cheung, Leung, Zhang, et al. (2001) article as the target. The factor loadings

are presented in Table 1. After Procrustes rotation, the factor congruence coefficients are sat-

isfactory, ranging from .92 to .99, with a total congruence coefficient of .97. The variance

explained for the Procrustes rotated structure ranges from 9.5% to 20.0%, with a total

explained variance of 57.8%. Only a few secondary loadings are different between the two

structures. Of the 22 CPAI personality scales, 20 have the same primary loadings in both

structures. Only 2 scales, Veraciousness versus Slickness and Face, loaded differently. Vera-

ciousness versus Slickness has a primary loading on Individualism in the Singaporean Chi-

nese sample, although it loads primarily on Dependability in the Chinese normative sample.

Face loads primarily on Dependability in the Singaporean sample, although it loads primar-

ily on Interpersonal Relatedness in the Chinese normative sample. Nonetheless, the second-

ary loadings of Veraciousness versus Slickness on Dependability and Face on Interpersonal

Relatedness are higher than .40 in both samples. Five other scales also have double loadings,

namely, Graciousness versus Meanness, Meticulousness, Flexibility, Logical versus Affec-

tive Orientation, and Defensiveness. The patterns of double loadings of these five scales are

consistent across the two samples. Essentially, the factor structure of the English CPAI in the

present Singaporean sample is similar to the Chinese CPAI factor structure obtained for the

standardization samples in China and Hong Kong (Cheung, Leung, Zhang, et al., 2001). The

Procrustes rotated factor structure is described in detail below.

Following previous CPAI interpretation, Factor 1 is labeled as Dependability, character-

ized by positive loadings of Practical Mindedness, Responsibility, Graciousness versus

Meanness, Veraciousness versus Slickness, Optimism versus Pessimism, Meticulousness,

Downloaded from jcc.sagepub.com at University of Ulster Library on March 6, 2015

Cheung et al. / ENGLISH CPAI 439

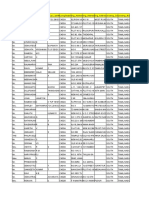

TABLE 1

Four-Factor Principal Component Analysis With Procrustes Rotation

of the English CPAI (Chinese Personality Assessment Inventory)

Cheung, Leung,

Zhang, et al. (2001)

Singapore (N = 531)

Normative Sample

Initial Solution Procrustes Rotated (N = 2,444)

DEP IR SOC IND DEP IR SOC IND DEP IR SOC IND

Practical Mindedness .71 .24 –.18 –.08 .75 .09 –.13 .12 .74 .14 –.30 –.11

Emotionality –.72 –.24 –.10 .10 –.74 –.11 –.15 –.08 –.73 –.02 –.17 .01

Responsibility .69 .29 .09 .09 .68 .16 .13 .27 .73 .28 .07 .23

Inferiority versus

Self-Acceptance –.78 .22 –.17 .13 –.72 .34 –.26 –.03 –.65 .36 –.39 .05

Graciousness versus

Meanness .47 –.10 .01 –.63 .58 –.16 .06 –.51 .65 –.21 .01 –.44

Veraciousness versus

Slickness .33 .15 –.07 –.65 .50 .11 –.05 –.54 .61 .09 –.18 –.30

Optimism versus Pessimism .65 –.10 .32 –.15 .62 –.18 .38 –.01 .59 –.20 .51 –.03

Meticulousness .50 .56 –.11 .13 .55 .43 –.10 .29 .57 .32 –.03 .25

External versus Internal

Locus of Control –.45 .17 –.22 .31 –.46 .22 –.28 .22 –.57 .20 –.19 .05

Family Orientation .50 .26 .01 –.35 .61 .18 .03 –.20 .54 .21 .19 –.42

Ren Qing (Relationship

Orientation) –.16 .70 .23 –.04 –.03 .74 .16 –.02 –.11 .73 .12 .00

Harmony .13 .80 .09 –.05 .27 .76 .04 .05 .26 .70 –.07 .09

Flexibility –.05 –.66 .04 –.45 –.06 –.62 .08 –.51 .00 –.60 –.01 –.47

Modernization .02 –.62 .13 –.04 –.10 –.59 .17 –.10 .00 –.57 .16 .03

Face –.62 .42 .06 .21 –.57 .52 –.03 .09 –.54 .55 .07 .17

Thrift versus Extravagance .08 .56 –.12 .10 .16 .52 –.15 .17 .27 .49 –.36 .17

Introversion versus

Extraversion .02 .02 –.79 .28 .01 –.06 –.78 .30 .04 –.04 –.79 .17

Leadership .16 .17 .80 .28 .05 .20 .80 .31 .04 .15 .73 .40

Adventurousness .48 –.31 .59 .09 .33 –.34 .65 .16 .26 –.41 .67 .10

Self versus Social

Orientation .11 .14 –.12 .71 –.04 .08 –.12 .73 –.15 .01 –.06 .81

Logical versus Affective

Orientation .40 .50 .28 .38 .35 .42 .28 .49 .24 .38 .31 .53

Defensiveness

(Ah-Q Mentality) –.27 .40 .14 .62 –.35 .43 .09 .57 –.38 .44 .18 .45

Factor congruence .96 .96 .95 .92 .99 .99 .96 .94

Sum of squared loadings 4.49 3.68 2.06 2.57 4.75 3.42 2.21 2.42 4.87 3.31 2.55 2.22

Variance explained (%) 20.4 16.7 9.4 11.7 21.6 15.6 10.1 11.0 22.1 15.1 11.6 10.1

NOTE: Initial solution = varimax orthogonal rotated solution. Procrustes rotated = after Procrustes rotation using

the standardization sample as the target. DEP = Dependability. IR = Interpersonal Relatedness. SOC = Social

Potency. IND = Individualism. Factor loadings with a magnitude of at least .40 and factor congruence coefficients

larger than .90 are in boldface.

Family Orientation, Face, and negative loadings of Inferiority versus Self-Acceptance,

External versus Internal Locus of Control, and Emotionality. The variance explained by

Dependability is 21.6%.

Factor 2 is labeled as Interpersonal Relatedness, characterized by positive loadings of

Ren Qing (Relationship Orientation), Harmony, Face, Thrift versus Extravagance, and

Downloaded from jcc.sagepub.com at University of Ulster Library on March 6, 2015

440 JOURNAL OF CROSS-CULTURAL PSYCHOLOGY

TABLE 2

Five-Factor Principal Component Analysis of NEO-FFI (N = 531)

Neuroticism Extraversion Openness Agreeableness Conscientiousness

Neuroticism 1 .84 –.13 –.05 –.04 –.15

Neuroticism 2 .84 –.11 –.04 –.20 –.07

Neuroticism 3 .83 –.17 .05 .00 –.24

Extraversion 1 .00 .82 .07 .12 –.08

Extraversion 2 –.21 .81 .03 .02 .17

Extraversion 3 –.29 .71 .08 .00 .23

Openness 1 –.04 .24 .53 –.33 –.18

Openness 2 –.02 –.04 .81 –.03 .06

Openness 3 –.01 .08 .82 .12 –.02

Agreeableness 1 –.06 .19 –.01 .76 .23

Agreeableness 2 –.39 .29 .11 .62 .06

Agreeableness 3 –.03 –.14 –.08 .85 .02

Conscientiousness 1 –.04 .05 –.09 .17 .85

Conscientiousness 2 –.23 .04 .01 .08 .84

Conscientiousness 3 –.19 .15 .02 .05 .83

Sum of squared loadings 2.47 2.13 1.67 1.90 2.40

Variance explained (%) 16.4 14.2 11.1 12.6 16.0

NOTE: Loadings after varimax orthogonal rotation. Factor loadings with a magnitude of at least .40 are in

boldface.

negative loadings of Flexibility and Modernization. Meticulousness, Logical versus Affec-

tive Orientation, and Defensiveness (Ah-Q Mentality) also have secondary positive loadings

on this factor. The variance explained by Interpersonal Relatedness is 15.6%.

Factor 3 is labeled as Social Potency, characterized by positive loadings of Leadership

and Adventurousness and negative loading of Introversion versus Extraversion. The vari-

ance explained by Social Potency is 10.1%.

Factor 4 is labeled as Individualism, characterized by Self versus Social Orientation, Log-

ical versus Affective Orientation, and Defensiveness. Graciousness versus Meanness also

has a secondary positive loading on this factor. The variance explained by Individualism is

11.0%.

FACTOR STRUCTURE OF NEO-FFI

The principal component analysis results using of the NEO-FFI are presented in Table 2.

Varimax orthogonal rotation is used on the factor structure. The variance explained ranges

from 11.1% to 16.3%, with a total explained variance of 69.8%. Generally, the Big Five

structure is recovered, with the exception of one secondary loading in Agreeableness. This is

not an artifact of the formation of subscales, as follow-up analysis at the item level also dis-

covered some non-negligible secondary loadings.

JOINT FACTOR ANALYSIS OF ENGLISH CPAI AND NEO-FFI

The 22 English CPAI personality scales and the 15 NEO-FFI subscales were jointly ana-

lyzed by principal component analysis coupled with varimax orthogonal rotation. To com-

pare with the findings in Cheung, Leung, Zhang, et al. (2001) study in which jointly factor

analyzed Chinese CPAI and Chinese NEO-PI-R in a Chinese sample, the six- and five-factor

Downloaded from jcc.sagepub.com at University of Ulster Library on March 6, 2015

Cheung et al. / ENGLISH CPAI 441

TABLE 3

Six-Factor Solution for the Joint Factor Analysis of NEO-FFI and CPAI

(Chinese Personality Assessment Inventory) (N = 531)

CON IR AGR NEU EXT OPE

a

Conscientiousness 1 .75 .15 .14 –.05 .12 –.07

Conscientiousness 2a .75 .16 .08 –.23 .11 .01

Conscientiousness 3a .73 .07 .04 –.17 .22 .04

Meticulousness .76 .23 .07 –.03 –.07 –.11

Responsibility .78 .03 .01 –.28 .04 .05

Practical Mindedness .58 –.05 .19 –.36 –.17 –.14

Family Orientation .42 –.13 .26 –.27 .04 –.19

Harmony .31 .62 .33 –.03 .05 –.24

Ren Qing (Relationship Orientation) .11 .61 .25 .17 .13 –.10

Thrift versus Extravagance .28 .45 .19 .14 –.14 .00

Flexibility –.46 –.58 .20 –.18 .04 .20

Logical versus Affective Orientation .43 .60 –.01 –.23 .04 .24

Self versus Social Orientation .02 .57 –.31 –.13 –.35 .18

Defensiveness (Ah-Q Mentality) –.02 .66 –.42 .14 .05 –.14

Agreeableness 1a .19 .18 .68 –.09 .17 –.02

Agreeableness 2a .06 –.08 .58 –.31 .33 .09

Agreeableness 3a –.03 .13 .74 –.03 –.12 –.06

Graciousness versus Meanness .14 –.38 .55 –.35 .04 .07

Veraciousness versus Slickness .20 –.24 .61 –.15 .01 –.02

Neuroticism 1a –.05 –.09 –.07 .80 –.18 .00

Neuroticism 2a –.05 .09 –.23 .74 –.15 –.03

Neuroticism 3a –.19 .09 –.04 .75 –.19 .06

Optimism versus Pessimism .16 –.07 .14 –.74 .15 .04

Emotionality –.39 –.10 –.21 .63 .01 .13

Inferiority versus Self-Acceptance –.40 .33 –.06 .63 –.03 –.15

Adventurousness .11 –.13 –.20 –.57 .38 .25

Face –.17 .47 –.10 .50 .12 –.22

Extraversion 1a –.09 .01 .14 –.02 .75 .05

Extraversion 2a .11 .00 .06 –.24 .76 –.01

Extraversion 3a .18 .00 .02 –.31 .67 .04

Introversion versus Extraversion .00 .09 –.02 .08 –.77 –.08

Leadership .22 .36 –.22 –.20 .57 .29

Openness 1a –.17 –.06 –.29 –.02 .20 .54

Openness 2a .06 .02 –.03 .00 .04 .72

Openness 3a –.02 –.04 .15 –.02 .08 .77

Modernization –.23 –.35 .03 –.07 –.03 .58

External versus Internal Locus of Control –.26 .36 –.18 .32 –.15 –.10

Sum of squared loadings 4.72 3.60 3.07 4.74 3.27 2.29

Variance explained (%) 12.7 9.7 8.3 12.8 8.8 6.2

NOTE: CON = Conscientiousness. IR = Interpersonal Relatedness. AGR = Agreeableness. NEU = Neuroticism.

EXT = Extraversion. OPE = Openness. Factor loadings with a magnitude of at least .40 are in boldface.

a. Facet of the NEO-FFI.

solutions were attempted. The factor loadings of the two solutions are presented in Table 3

and Table 4.

The six-factor solution presented in Table 3 explains 59% of the total variance. Instead of

arranging by decreasing order in terms of variance explained, the six factors are arranged

such that the differences between the six-factor and the five-factor solutions can be readily

shown. Factor 1 is characterized by positive loadings of Conscientiousness of NEO-FFI, and

Downloaded from jcc.sagepub.com at University of Ulster Library on March 6, 2015

442 JOURNAL OF CROSS-CULTURAL PSYCHOLOGY

the four CPAI scales, namely, Meticulousness, Responsibility, Practical Mindedness, and

Family Orientation. Flexibility and Inferiority versus Self-Acceptance of the CPAI have neg-

ative secondary loadings, whereas Logical versus Affective Orientation has a positive sec-

ondary loading on Factor 1. This factor is similar to the Conscientiousness factor in the five-

factor model. The variance explained by Conscientiousness is 12.7%.

Factor 2 is characterized by positive loadings of seven CPAI scales, namely, Harmony,

Ren Qing (Relationship Orientation), Thrift versus Extravagance, Logical versus Affective

Orientation, Self versus Social Orientation, and Defensiveness, and a negative loading of

Flexibility. Face has a secondary loading on this factor. None of the NEO-FFI subscales

loads on this factor. This factor defines the Interpersonal Relatedness in the CPAI (Cheung,

Leung, Zhang, et al., 2001). The variance explained by this factor is 9.7%.

Factor 3 is characterized by Agreeableness in NEO-FFI, as well as Graciousness versus

Meanness and Veraciousness versus Slickness of the CPAI. Defensiveness (Ah-Q Mentality)

of the CPAI also has a negative secondary loading on Factor 3. This factor is interpreted as the

Agreeableness factor of the five-factor model. The variance explained by this factor is 6.3%.

Factor 4 is characterized by Neuroticism of NEO-FFI, as well as Emotionality, Inferiority

versus Self-acceptance, and Face, and negative loadings of Adventurousness and Optimism

versus Pessimism from the CPAI. The factor is a blend of Neuroticism factor of the five-factor

model and the Dependability factor of the CPAI. This factor is defined as the Neuroticism

factor of the five-factor model. The variance explained by this factor is 12.8%.

Factor 5 is characterized by Extraversion of NEO-FFI and Leadership of the CPAI, and a

negative loading of Introversion-Extraversion of the CPAI. This factor defines the

Extraversion factor of the five-factor model. The variance explained by this factor is 8.8%.

Factor 6 is characterized by Openness of NEO-FFI, and Modernization of the CPAI. This

factor is similar to the Openness factor of the five-factor model. The variance explained by

this factor is 6.2%.

In sum, the Big Five factors are clearly recovered in the six-factor solution. All five NEO-

FFI factors are supplemented by some CPAI scales that are conceptually similar. Moreover,

the Interpersonal Relatedness of the CPAI is also recovered in the six-factor solution. This

factor is defined solely by scales of the CPAI. None of the NEO-FFI subscales loads on this

factor.

The five-factor solution is presented in Table 4. The independence of the Big Five is not as

clear-cut in the five-factor solution. Two of the subscales of Conscientiousness of the NEO-

FFI, as well as Practical Mindedness and Family Orientation, load on both Conscientious-

ness and Neuroticism factors. Most of the scales from the Interpersonal Relatedness factor

load on the NEO-FFI Conscientiousness factor, whereas Self versus Social Orientation and

Defensiveness load on the NEO-FFI Agreeableness factor. The five-factor solution explains

55% of the total variance. Comparison of the six- and five-factor solutions suggests that the

Interpersonal Relatedness factor can be extracted as a separate factor independent of the Big

Five.

The six-factor solution in this study is compared with the six-factor solution reported in

Cheung, Leung, Zhang, et al. (2001), which jointly factor analyzed the Chinese version of

the CPAI and NEO-PI-R (pp. 413-414). The two factor structures are considerably similar in

terms of the relation between the CPAI and the Big Five Factors. The CPAI Meticulousness,

Responsibility, and Practical Mindedness scales load together with the NEO-FFI Conscien-

tiousness facets in both the present study and the study by Cheung, Leung, Zhang, et al.

(2001). Moreover, the CPAI Graciousness versus Meanness and Veraciousness versus Slick-

ness scales load together with the NEO-FFI Agreeableness facets in both studies. The CPAI

Downloaded from jcc.sagepub.com at University of Ulster Library on March 6, 2015

Cheung et al. / ENGLISH CPAI 443

TABLE 4

Five-Factor Solution for the Joint Factor Analysis of NEO-FFI and CPAI

(Chinese Personality Assessment Inventory) (N = 531)

CON AGR NEU EXT OPE

a

Conscientiousness 1 .66 .14 –.27 .05 –.07

Conscientiousness 2a .66 .06 –.42 .07 .00

Conscientiousness 3a .58 .05 –.40 .16 .05

Meticulousness .71 .05 –.24 –.13 –.11

Responsibility .58 .02 –.53 –.02 .05

Practical Mindedness .40 .19 –.54 –.20 –.14

Family Orientation .23 .28 –.42 .01 –.18

Harmony .67 .21 .11 .12 –.28

Ren Qing (Relationship Orientation) .52 .14 .35 .19 –.13

Thrift versus Extravagance .54 .10 .18 –.11 –.02

Flexibility –.71 .29 –.19 .03 .22

Logical versus Affective Orientation .72 –.14 –.13 .13 .20

Self versus Social Orientation .37 –.45 .10 –.22 .13

Defensiveness (Ah-Q Mentality) .39 –.54 .36 .13 –.18

Agreeableness 1a .33 .64 –.05 .20 –.03

Agreeableness 2a .05 .57 –.28 .35 .08

Agreeableness 3a .15 .69 .07 –.07 –.07

Graciousness versus Meanness –.10 .60 –.47 .02 .08

Veraciousness versus Slickness .06 .64 –.27 –.03 –.01

Neuroticism 1a –.08 .00 .64 –.31 .04

Neuroticism 2a .02 –.20 .66 –.24 –.01

Neuroticism 3a –.06 –.02 .73 –.26 .09

Optimism versus Pessimism .07 .11 –.69 .23 .02

Emotionality –.36 –.15 .63 –.05 .16

Inferiority versus Self-Acceptance –.07 –.10 .81 –.02 –.15

Adventurousness –.05 –.19 –.58 .41 .23

Face .19 –.16 .66 .13 –.24

Extraversion 1a –.05 .16 .04 .74 .05

Extraversion 2a .06 .07 –.24 .75 –.02

Extraversion 3a .11 .03 –.33 .67 .04

Introversion versus Extraversion .07 –.06 .10 –.73 –.09

Leadership .37 –.28 –.12 .61 .26

Openness 1a –.18 –.29 .01 .21 .54

Openness 2a .07 –.05 –.01 .05 .72

Openness 3a .00 .14 –.02 .10 .77

Modernization –.39 .08 –.11 –.04 .59

External versus Internal Locus of Control .04 –.25 .50 –.10 –.11

Sum of squared loadings 5.26 3.20 6.08 3.42 2.32

Variance explained (%) 14.2 8.6 16.4 9.2 6.3

NOTE: CON = Conscientiousness. AGR = Agreeableness. NEU = Neuroticism. EXT = Extraversion. OPE = Open-

ness. The table is arranged for easier comparison with the six-factor solution. Factor loadings with a magnitude of

at least .40 are in boldface.

a. Facet of the NEO-FFI.

Emotionality, Inferiority versus Self-Acceptance, and Adventurousness scales load together

with the NEO-FFI Neuroticism facets in both studies. Introversion versus Extraversion of the

CPAI also consistently loads together with Extraversion of the five-factor model. In both

studies, the CPAI Ren Qing (Relationship Orientation), Harmony, Flexibility, Logical versus

Downloaded from jcc.sagepub.com at University of Ulster Library on March 6, 2015

444 JOURNAL OF CROSS-CULTURAL PSYCHOLOGY

Affective Orientation, and Defensiveness (Ah-Q Mentality) scales form the Interpersonal

Relatedness factor that is not found in the five-factor model.

Some discrepancies are found between the two studies. For example, Optimism versus

Pessimism loads on the Interpersonal Relatedness factor in Cheung, Leung, Zhang, et al.

(2001) but loads on Neuroticism in this study. Thrift versus Extravagance loads on the Inter-

personal Relatedness factor in this study but not in Cheung, Leung, Zhang, et al. (2001). Self

versus Social Orientation double-loads on Agreeableness and Extraversion in Cheung,

Leung, Zhang, et al. (2001), whereas it loads on Interpersonal Relatedness in this study.

Moreover, Modernization of the CPAI loads together with Openness in the Singapore study

but not in Cheung, Leung, Zhang, et al. (2001). In their earlier study with students in main-

land China, none of the CPAI scales load on the Openness factor. Nevertheless, 14 CPAI

scales load on similar factors in the two studies in terms of the primary loadings. Albeit strict

comparison is not possible because of the different inventories used for the FFM, the results

confirm that the English CPAI relates to the FFM in a pattern similar to Cheung, Leung,

Zhang, et al.’s (2001) findings using the Chinese versions of the measures.

STUDY 2

With the establishment of the English version of the CPAI, the next step is to examine

whether the Interpersonal Relatedness factor is also relevant to Western cultures. In a mirror

position, the CPAI is an imported instrument to Western cultures, just as the NEO-PI-R or

NEO-FFI is an imported instrument to the Chinese cultures. Two important questions were

examined. The first was whether the same four-factor structure of the CPAI would be found

in non-Chinese respondents. Following this, the second question was whether the Interper-

sonal Relatedness factor of the CPAI would be found in non-Chinese respondents. As shown

in Study 1, Interpersonal Relatedness was independent of the five-factor model in the joint

factor analysis of the NEO-FFI and the CPAI. If the Interpersonal Relatedness factor was

also found in a Caucasian sample, then it would suggest that Interpersonal Relatedness,

although developed indigenously in the Chinese culture, may be a construct relevant to other

cultures.

A preliminary study has been reported on the use of the English version of the CPAI in a

non-Chinese culture (Cheung, Leung, Zhang, et al., 2001, Study 3). That study was based on

Gan’s (1998) doctoral research, in which she administered 16 scales of the CPAI along with

the NEO-FFI to a sample of 273 Hawaiian undergraduate students. Cheung, Leung, Zhang,

et al. (2001) found that the selected scales of the Interpersonal Related factor cannot be sub-

sumed under the five-factor model, providing a partial support of the uniqueness of the Inter-

personal Related factor. However, Gan’s (1998) study had two limitations. First, only a par-

tial list of the CPAI scales was used in that study. Second, the Hawaiian sample is a

multiethnic sample, including respondents who are ethnic Asian Americans. Study 2 exam-

ined the structure of all 22 personality scales of the CPAI in a single-ethnic sample, namely a

Caucasian college sample in the United States. Similar to the importation of translated West-

ern instruments such as the NEO-PI-R and the NEO-FFI to Asian cultures, the exportation of

the CPAI to a Western culture is an example of the imposed etic approach. In this study, we

examined the factor structure of the CPAI and the presence or absence of the Interpersonal

Relatedness factor in the Caucasian American sample.

Downloaded from jcc.sagepub.com at University of Ulster Library on March 6, 2015

Cheung et al. / ENGLISH CPAI 445

METHOD

PARTICIPANTS

The sample consisted of 144 college students studying in a Midwestern university in the

United States (41 males, 103 females). Only Caucasian Americans were included in this

sample. Using the standard CPAI screening criteria, participants with a Response Consis-

tency Index less than 4, an Infrequency Scale score greater than 4, or had 30 or more items

unanswered were classed as invalid protocols and deleted from subsequent analysis. The

number of cases retained was 137 (38 males, 99 females).

INSTRUMENT

The English version of the CPAI developed in Study 1 was used. The median Cronbach’s

alpha of the 22 CPAI personality scales for this sample was .62 (ranging from .33 to .78).

Specifically, the Cronbach’s alphas of the six Interpersonal Relatedness scales, Ren Qing,

Harmony, Flexibility, Modernization, Face, and Thrift versus Extravagance were .53, .56,

.74, .57, .66, and .57, respectively. The corresponding Cronbach’s alphas in the Singaporean

Chinese sample were .58, .72, .72, .59, .73, and .56, respectively. Although one scale, the

Harmony scale, had a smaller Cronbach’s alpha in the United States Caucasian sample, the

other results were generally similar between the two samples.

PROCEDURE

The participants signed up for the study via the department’s Web page that listed all of

the current research studies that were available for course credit. At the beginning of the ses-

sion, the participants were given a packet that contained an introductory statement and the

survey instruments. The introductory statement described the purpose of the study and

informed the respondents that their participation was voluntary and that they could withdraw

from the study at any time. It also reminded them that their continuation in the study repre-

sented their informed consent to participate. The respondents completed the English version

of the CPAI and a short demographic survey in small groups ranging from 10 to 25 people.

They completed these instruments individually and anonymously and in exchange for aca-

demic course credit in an introductory psychology course. At the end of the study, they were

read a brief debriefing statement concerning the purpose of the study and that no deception

was used in the study.

ANALYSIS

In conformance with the reasons mentioned in Study 1, as well as because of the relatively

small sample size of the Caucasian sample, we examined the factor structure of the English

CPAI using principal component analysis instead of confirmatory factor analysis. The focus

was on the four-factor solution, to examine whether the Caucasian factor structure was simi-

lar to that of the normative Chinese sample. Procrustes rotation was conducted to rotate the

Caucasian sample structure to the normative Chinese structure. We computed factor congru-

ence coefficients to assess the similarity of factor structures. We also compared the Cauca-

sian factor structure to the Singaporean factor structure, as both samples used the same lan-

guage version of the CPAI.

Downloaded from jcc.sagepub.com at University of Ulster Library on March 6, 2015

446 JOURNAL OF CROSS-CULTURAL PSYCHOLOGY

RESULTS

COMPARISON BETWEEN THE CAUCASIAN AND THE

CHINESE NORMATIVE FACTOR STRUCTURES

Table 5 shows the initial varimax-rotated four-factor solution of the Caucasian English

CPAI data and the Procrustes-rotated solution using the Chinese normative factor structure

as the target. When compared to the Singapore results reported in Study 1, the initial

varimax-rotated solution is less similar to the Chinese normative factor structure. However,

when the initial factor structure is rotated by Procrustes rotation using the Chinese normative

factor structure as the target, the two structures have similar patterns of loadings. All factor

congruence coefficients are at or higher than .90. The total variance explained by the four-

factor solution is 54.6%, and the variance explained by individual factors are 21.9%, 11.5%,

11.7%, and 9.5% for Dependability, Interpersonal Relatedness, Social Potency, and Individ-

ualism, respectively. The patterns of variance explained are similar between the two struc-

tures. Moreover, the factor congruence coefficients are .98, .93, .90, and .95 for Dependabil-

ity, Interpersonal Relatedness, Social Potency, and Individualism, respectively, and the total

congruence coefficient of the two factor structures is .95. Of the 22 CPAI personality scales,

20 have the same primary loading in the two samples. Only 2 scales, Face and Defensiveness,

load differently across the two samples. In the Caucasian sample, Face loads primarily on

Dependability, whereas in the Chinese normative sample, Face is a double-loading scale. It

loads primarily on Interpersonal Relatedness while having a negative secondary loading on

Dependability. Defensiveness (Ah-Q Mentality) loads primarily on Dependability in the

Caucasian sample, although it loads primarily on Individualism in the Chinese normative

sample. Essentially, the four-factor structure in the Chinese normative sample is recovered in

the Caucasian sample when the English version of the CPAI was administered.

COMPARISON BETWEEN THE CAUCASIAN AND THE

SINGAPOREAN CHINESE FACTOR STRUCTURES

We compared the Procrustes-rotated solutions of the Singaporean Chinese sample (in

Table 1) and the Caucasian sample (in Table 5). Because both solutions used the same Chi-

nese normative structure as the target, no further Procrustes rotation is necessary to rotate the

factor structure to each other. The factor congruence coefficients are .98, .94, .91, and .95 for

Dependability, Interpersonal Relatedness, Social Potency, and Individualism, respectively,

all higher than .90. The total congruence coefficient between the two structures is .95. Of the

22 CPAI personality scales, 21 have the same primary loadings in the two samples. Only one

scale, Veraciousness versus Slickness, loads differently across the two samples. In the Cau-

casian sample, Veraciousness versus Slickness loads primarily on Dependability, whereas in

the Singaporean Chinese sample Veraciousness versus Slickness loads primarily on Individ-

ualism. In short, a similar four-factor structure is found in both the Singaporean Chinese

sample and the Caucasian sample.

DISCUSSION

This article reports the validity of the English CPAI. The first study provides empirical

support for the structural equivalence between the English version of the CPAI and the

Downloaded from jcc.sagepub.com at University of Ulster Library on March 6, 2015

Cheung et al. / ENGLISH CPAI 447

TABLE 5

Four-Factor Principal Component Analysis With Procrustes Rotation of the English

CPAI (Chinese Personality Assessment Inventory) in the U.S. Sample

Cheung, Leung,

Zhang, et al. (2001)

Caucasian Americans (N = 137)

Normative Sample

Initial Solution Procrustes Rotated (N = 2,444)

DEP IR SOC IND DEP IR SOC IND DEP IR SOC IND

Practical Mindedness .63 –.27 .13 .39 .75 –.13 –.23 .00 .74 .14 –.30 –.11

Emotionality –.55 .04 –.51 –.10 –.69 .11 –.30 .08 –.73 –.02 –.17 .01

Responsibility .46 .00 .43 .49 .76 .12 .09 .18 .73 .28 .07 .23

Inferiority versus

Self-Acceptance –.44 .03 –.65 .00 –.61 .16 –.47 .03 –.65 .36 –.39 .05

Graciousness versus

Meanness .74 .08 .27 –.22 .57 –.14 .25 –.52 .65 –.21 .01 –.44

Veraciousness versus

Slickness .67 .10 .02 –.01 .52 .02 –.03 –.44 .61 .09 –.18 –.30

Optimism versus Pessimism .40 –.01 .69 .03 .61 –.13 .50 .03 .59 –.20 .51 –.03

Meticulousness .17 .08 .06 .78 .52 .40 –.27 .38 .57 .32 –.03 .25

External versus Internal

Locus of Control –.44 .30 –.19 .06 –.42 .36 –.02 .14 –.57 .20 –.19 .05

Family Orientation .57 .14 .05 .16 .53 .14 –.05 –.27 .54 .21 .19 –.42

Ren Qing (Relationship

Orientation) –.12 .72 .02 .00 –.16 .64 .28 –.16 –.11 .73 .12 .00

Harmony .16 .71 .18 .21 .23 .68 .29 –.13 .26 .70 –.07 .09

Flexibility .29 –.41 .04 –.59 .00 –.66 .10 –.40 .00 –.60 –.01 –.47

Modernization –.04 –.55 .01 –.20 –.07 –.57 –.09 .08 .00 –.57 .16 .03

Face –.56 .38 –.20 –.07 –.59 .38 .07 .10 –.54 .55 .07 .17

Thrift versus Extravagance –.01 .13 –.15 .62 .21 .42 –.34 .30 .27 .49 –.36 .17

Introversion versus

Extraversion –.09 –.52 –.50 .32 –.07 –.23 –.72 .25 .04 –.04 –.79 .17

Leadership –.24 .19 .72 .02 .09 .09 .69 .36 .04 .15 .73 .40

Adventurousness .20 –.06 .81 –.15 .42 –.26 .69 .09 .26 –.41 .67 .10

Self versus Social

Orientation –.51 –.24 .23 .37 –.11 –.03 .02 .70 –.15 .01 –.06 .81

Logical versus Affective

Orientation –.04 .05 .45 .37 .32 .15 .24 .40 .24 .38 .31 .53

Defensiveness

(Ah-Q Mentality) –.76 .08 –.06 .02 –.61 .16 .07 .43 –.38 .44 .18 .45

Factor congruence .89 .76 .81 .54 .98 .93 .90 .95

Sum of squared loadings 4.19 2.24 3.26 2.31 4.81 2.52 2.58 2.08 4.87 3.31 2.55 2.22

Variance explained (%) 19.1 10.2 14.8 10.5 21.9 11.5 11.7 9.5 22.1 15.1 11.6 10.1

NOTE: Initial solution = varimax orthogonal rotated solution. Procrustes rotated = after Procrustes rotation using

the standardization sample as the target. DEP = Dependability. IR = Interpersonal Relatedness. SOC = Social

Potency. IND = Individualism. Factor loadings with a magnitude of at least .40 and factor congruence coefficients

larger than .90 are in boldface.

original Chinese version in a sample of Singaporean Chinese. In the second study, support

for the cross-cultural relevance of the structure of the CPAI is obtained using the English ver-

sion of the CPAI with a Caucasian American sample.

Downloaded from jcc.sagepub.com at University of Ulster Library on March 6, 2015

448 JOURNAL OF CROSS-CULTURAL PSYCHOLOGY

STRUCTURAL EQUIVALENCE OF THE ENGLISH VERSION OF THE CPAI

The CPAI is translated into English and administered to a diverse sample of Singaporean

Chinese who are proficient in English. We adopt the same Procrustes rotation method used in

examining the cross-cultural similarity of personality factors in the five-factor model to com-

pare the factor structure of the CPAI. The same four-factor structure is found in the Singapore

sample using the translated English CPAI. Quantitatively, the factor congruence coefficients

and the total congruence coefficient are all higher than .90 when the Singaporean structure is

rotated toward the normative structure of the Chinese CPAI by Procrustes rotation. Qualita-

tively, the factor loading structure of the English CPAI in the Singaporean Chinese sample is

highly similar to the structure of normative sample. The pattern of primary factor loadings is

the same for most of the CPAI scales across the two samples.

The joint factor analysis of the English CPAI and the NEO-FFI in the Singapore sample

provides further support for the adequacy of the English CPAI when compared to the find-

ings of Cheung, Leung, Zhang, et al.’s (2001) study in which the Chinese CPAI was jointly

factor analyzed with the NEO-PI-R. Although direct comparison is not possible because of

the different five-factor model instruments used, the patterns of overlap are very similar

between the structures. This provides external support to the structural equivalence between

the two language versions of the CPAI.

COMPARISON BETWEEN THE CPAI AND THE NEO-FFI

IN THE SINGAPOREAN CHINESE SAMPLE

The results of the comparisons between the English CPAI, a measure indigenous to the

Chinese culture, with the NEO-FFI, an imported measure from a Western culture, echo two

findings of Cheung, Leung, Zhang, et al.’s (2001) study. First, the five-factor model does not

cover all the important personality factors in the Chinese culture. Similar to Cheung, Leung,

Zhang, et al.’s (2001) finding on the joint factor analysis of the Chinese CPAI and the NEO-

PI-R, the Interpersonal Relatedness factor of the CPAI is unique and clearly defined in the

six-factor solution. The Interpersonal Relatedness factor is forced to merge with the Consci-

entiousness factor only in the five-factor solution. Moreover, in the five-factor solution, the

NEO-FFI Conscientiousness indicators have secondary loadings on the Neuroticism factor.

Although the six-factor solution is not as clearly defined as the five-factor solution as in

Cheung, Leung, Zhang, et al.’s (2001) study, the results do suggest that the Interpersonal

Relatedness factor can be extracted as a factor independent of the Big Five.1

Second, the Openness factor of the five-factor model is missing from the CPAI and is

defined mainly by NEO-FFI and NEO-PI-R subscales. In Cheung, Leung, Zhang, et al.’s

(2001) study, Openness was defined only by NEO-PI-R Openness facets, and in the present

study Openness is defined mainly by NEO-FFI Openness subscales. Modernization is the

only CPAI scale that loads on this factor. Although the patterns are not exactly identical in the

two studies, it suggests that Openness is a unique FFM domain that is not adequately covered

by the CPAI.

In sum, we provide further support that the Interpersonal Relatedness factor of the CPAI is

an indigenous factor derived from the Chinese culture that is not covered by the Western five-

factor model, whereas the Openness factor of the five-factor model has not been included by

the indigenously derived personality measure.

Downloaded from jcc.sagepub.com at University of Ulster Library on March 6, 2015

Cheung et al. / ENGLISH CPAI 449

EXPORTING THE CPAI TO THE WESTERN CULTURE

We have originally assumed the indigenous Interpersonal Relatedness factor of the CPAI

to be a culturally unique personality construct. Is this indigenous Chinese construct also rele-

vant to non-Chinese cultures? Study 2 provides preliminary support for the four-factor struc-

ture of the CPAI in a Western culture. Both in terms of the pattern of primary loadings and the

congruence coefficients, the factor structure of the English version CPAI in a Caucasian

American college student sample is similar to the structures found in the Chinese normative

sample and the Singaporean Chinese sample. All factor congruence coefficients are higher

than .90. In other words, the same four Chinese personality factors can also be found in the

Caucasian American college student sample.

Similar to the early attempts to replicate the five-factor model by NEO-PI-R in cultures

outside North America (e.g., Guthrie & Bennett, 1971), Study 2 is a promising start to repli-

cate and examine the four Chinese factors of the CPAI in non-Chinese cultures. Using the

same method of analysis and the same index for comparison (i.e., Procrustes-rotation analy-

sis and factor congruence coefficients) that five-factor model researchers used (McCrae &

Costa, 1997; McCrae et al., 1998), the CPAI structure is clearly replicated in the Caucasian

American sample.

In Study 2, an indigenous instrument developed in a Chinese cultural context, the CPAI, is

exported to a foreign culture, the American culture. Had researchers administered only

Western instruments in non-Western cultures and not vice versa, it would not be possible to

assess fully whether the social-perceptual world was “cut” differently across cultures (Yik &

Bond, 1993, p. 92). More studies that cross-validate non-Western indigenous instruments in

Western and other cultures will provide a more complete picture of personality perceptions

across cultures. As argued by Poortinga and Van Hemert (2001), the “indigenous” Euro-

American psychology, which happens to be the mainstream, can benefit from concepts from

other indigenous psychologies.

INTERPERSONAL RELATEDNESS AS A UNIVERSAL CONSTRUCT

The findings of these studies suggest an important research question that needs to be

explored further in the future. Would Interpersonal Relatedness still be obtained as a unique

factor if the CPAI and the NEO-FFI or NEO-PI-R were jointly administered in Western cul-

tures? If we can also find a six-factor structure similar to that found among Chinese partici-

pants in Study 1 and Cheung, Leung, Zhang, et al.’s (2001) study, then it would suggest that

Interpersonal Relatedness factor is not unique to the Chinese culture. In the Caucasian sam-

ple in Study 2, the Interpersonal Relatedness factor is defined mainly by Ren Qing (Relation-

ship Orientation), Harmony, low Modernization, and low Flexibility. The Interpersonal

Relatedness factor reflects “a strong orientation toward instrumental relationships; emphasis

on occupying one’s proper place and engaging in appropriate action; avoidance of internal,

external, and interpersonal conflict; and adherence to norms and traditions” (Cheung,

Leung, Zhang, et al., 2001, p. 425). For example, high Interpersonal Relatedness suggests a

high tendency to accept others’requests but at the same time trying to avoid becoming indebted

to others’ favors (Ren Qing), to avoid offending other people (Harmony), to value traditional

practices and obedience to elders (low Modernization), and to stick to decisions made and to

dislike uncertainty (low Flexibility).

It has been generally believed that this interdependent and relational-oriented aspect of

personality is unique to the Chinese and some other Asian cultures. However, it is also

Downloaded from jcc.sagepub.com at University of Ulster Library on March 6, 2015

450 JOURNAL OF CROSS-CULTURAL PSYCHOLOGY

possible that although the interpersonal aspect is salient and emphasized in the Chinese cul-

ture, the construct is still relevant in other cultures. Using the means and standard deviations

of the Chinese normative sample (Cheung, Leung, Fan, et al., 1996), we converted the Cau-

casian sample’s scores on the Interpersonal Relatedness factor scales to t scores based on the

Chinese norms. The t score means for the Caucasian sample on Ren Qing, Harmony, Mod-

ernization, and Flexibility are 43, 36, 55, and 59, respectively, where 50 is the mean and 10 is

one standard deviation for the Chinese normative sample. The Caucasian sample is less rela-

tionship oriented, less harmonious, higher on modernization, and more flexible than the Chi-

nese normative sample. Although the Caucasian student sample and Chinese normative sam-

ple are not directly comparable, the differences are in the expected directions. Moreover,

there is some evidence that some relationship-related constructs may be relevant in the West-

ern culture. For example, Kwan, Bond, and Singelis (1997) found that in both Hong Kong

and the United States, the more harmonious the significant relationships are, the higher the

life satisfaction is, although the effect is stronger in Hong Kong than in the United States.

In their discussion of independent and interdependent selves, Markus and Kitayama

(1991) argued that “even within highly individualist Western culture, most people are still

much less self-reliant, self-contained, or self-sufficient than the prevailing cultural ideology

suggests that they should be” (p. 247). The standard deviations of the four major Interper-

sonal Relatedness scales in t score unit, as computed above, is consistent with this claim. The

standard deviations for Ren Qing, Harmony, Modernization, and Flexibility of the Caucasian

sample are 10.68, 10.99, 8.54, and 11.21, respectively—close to the value of 10 of the Chi-

nese normative sample. That is, the four scales have similar degrees of intrasample variation

in the two samples. Markus and Kitayama (1998) also suggested that Western theories

should be adapted to reflect the neglected interdependence nature of Western cultures. Ho,

Peng, Cheng-Lai, and Chan (2001) argued that “actions always take place in relational con-

texts” (p. 937), and interpersonal relationships are the most important relational contexts for

an individual. In the early Western history of personality psychology, the interpersonal or

interdependent concern was included in some personality theories (e.g., Sullivan, 1953;

Wiggins, 1979). Perhaps the prevalence of individualistic-collectivistic distinction

(Hofstede, 1980) in the past few decades increased the emphasis on the individualistic and

independent nature of the Western culture, resulting in the relative de-emphasis on the inter-

dependent concern that characterizes Western theories of personality.

FUTURE DIRECTION

In sum, the absence of Interpersonal Relatedness in a Western instrument may “point to a

blind spot” in Western personality theories, specifically the interdependent domains that

receive relatively less attention in Western personality theories (Cheung, Leung, Zhang, et al.,

2001; Cheung, in press). Although both the Singapore and American samples have similar

factor structures with the Chinese normative sample when Procrustes rotation technique is

applied, the initial varimax solution of the American sample is less similar to the Chinese

normative sample solution than that of the Singapore sample. This will warrant further

examination of the external validity and functional relationships of Interpersonal Related-

ness in Western cultures. In future studies, we will validate the functional equivalence of

Interpersonal Relatedness across cultures by examining its external behavioral correlates in

different cultural contexts.

Downloaded from jcc.sagepub.com at University of Ulster Library on March 6, 2015

Cheung et al. / ENGLISH CPAI 451

NOTE

1. One reviewer suggested that acquiescence might be a possible alternative reason for a separate Interpersonal

Relatedness factor—because most of the Interpersonal Relatedness scales were keyed in the same direction. As

argued in Cheung, Leung, Zhang, et al. (2001), this explanation implies that other similarly keyed scales would load

together, which is not the case in the two studies we presented. Nevertheless, to rule out this possibility, reverse items

have been added in the revised version of the CPAI, the CPAI-2 (Cheung, 2002). In the CPAI-2, an independent

Interpersonal Relatedness factor is again extracted, replicating the factor structure of the original CPAI.

REFERENCES

Berry, J. W. (1989). Imposed etics-emics-derived etics: The operationalization of a compelling idea. International

Journal of Psychology, 24, 721-735.

Brislin, R. W. (1970). Back-translation for cross-cultural research. Journal of Cross-Cultural Psychology, 1, 185-

216.

Cheung, F. M. (1985). Cross-cultural considerations for the translation of the Chinese MMPI in Hong Kong. In J. N.

Butcher & C. D. Spelberger (Eds.), Advances in personality assessment (Vol. 4, pp. 131-158). Hillsdale, NJ:

Lawrence Erlbaum.

Cheung, F. M. (2002, July 7-12). Significance of indigenous constructs in the study of personality. Paper presented

at the 25th International Congress of Applied Psychology, Singapore.

Cheung, F. M. (in press). Use of Western- and indigenously-developed personality tests in Asia. Applied Psychol-

ogy: An International Review.

Cheung, F. M., & Leung, K. (1998). Indigenous personality measures: Chinese examples. Journal of Cross-

Cultural Psychology, 29, 233-248.

Cheung, F. M., Leung, K., Fan, R., Song, W. Z., Zhang, J. X., & Zhang, J. P. (1996). Development of the Chinese

Personality Assessment Inventory (CPAI). Journal of Cross-Cultural Psychology, 27, 181-199.

Cheung, F. M., Leung, K., Zhang, J. X., Sun, H. F., Gan, Y. G., Song, W. Z., Xie, D. (2001). Indigenous Chinese per-

sonality constructs: Is the five-factor model complete? Journal of Cross-Cultural Psychology, 32, 407-433.

Church, A. T. (2001). Personality measurement in cross-cultural perspective. Journal of Personality, 69, 979-1006.

Church, A. T., & Lonner, W. J. (1998). The cross-cultural perspective in the study of personality. Journal of Cross-

Cultural Psychology, 29, 32-62.

Costa, P. T., Jr., & McCrae, R. R. (1992). Revised NEO Personality Inventory (NEO-PI-R) and NEO Five-Factor

Inventory (NEO-FFI) professional manual. Odessa, FL: Psychological Assessment Resources.

Ellemers, N., Spears, R., & Doosje, B. (2002). Self and social identity. Annual Review of Psychology, 53, 161-186.

Gan, Y. Q. (1998). Healthy personality traits and unique pathways to psychological adjustment: Cultural and gen-

der perspectives. Unpublished doctoral dissertation, the Chinese University of Hong Kong.

Guthrie, G. M., & Bennett, A. B. (1971). Cultural differences in implicit personality theory. International Journal of

Psychology, 6, 305-312.

Ho, D. Y. F., Peng, S. Q., Cheng-Lai, A., & Chan, S. F. (2001). Personality across cultural traditions. Journal of Per-

sonality, 69, 925-954.

Hofstede, G. (1980). Culture’s consequences. Beverly Hills, CA: Sage.

Kwan, V. S. Y., Bond, M. H., & Singelis, T. M. (1997). Pancultural explanations for life satisfaction: Adding rela-

tionship harmony to self-esteem. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 73, 1038-1051.

Markus, H. R., & Kitayama, S. (1991). Culture and the self: Implications for cognition, emotion, and motivation.

Psychological Bulletin, 98, 224-253.

Markus, H. R., & Kitayama, S. (1998). The cultural psychology of personality. Journal of Cross-Cultural Psychol-

ogy, 29, 63-87.

McCrae, R. R., & Costa, P. T., Jr. (1997). Personality trait structure as a human universal. American Psychologist,

52, 509-516.

McCrae, R. R., Costa, P. T., Jr., Del-Pilar, G. H., Rolland, J. P., & Parker, W. D. (1998). Cross-cultural assessment of

the five-factor model: The Revised NEO Personality Inventory. Journal of Cross-Cultural Psychology, 29, 71-

188.

McCrae, R. R., Costa, P. T., Jr., & Yik, M. S. M. (1996). Universal aspects of Chinese personality structure. In M. H.

Bond (Ed.), The handbook of Chinese psychology (pp. 189-207). New York: Oxford University Press.

McCrae, R. R., Zonderman, A. B., Costa, P. T. Jr., Bond, M. H., & Paunonen, S. V. (1996). Evaluating replicability

of factors in the Revised NEO Personality Inventory: Confirmatory factor analysis versus Procrustes rotation.

Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 70, 552-566.

Mulaik, S. A. (1972). The foundations of factor analysis. New York: McGraw-Hill.

Poortinga, Y. H., & Van Hemert, D. A. (2001). Personality and culture demarcating between the common and the

unique. Journal of Personality, 69, 1033-1060.

Downloaded from jcc.sagepub.com at University of Ulster Library on March 6, 2015

452 JOURNAL OF CROSS-CULTURAL PSYCHOLOGY

Singapore Department of Statistics. (2001a). Key demographic indicators. Retrieved from www.singstat.gov.sg/

STATS/demo.pdf

Singapore Department of Statistics. (2001b, July). Latest annual indicators. Retrieved from www.singstat.gov.sg/

FACT/KEYIND/keyind.html

Sullivan, H. S. (1953). The interpersonal theory of psychiatry. New York: Norton.

Sun, H. F., & Bond, M. H. (2000). Choice of influence tactics: Effects of the target person’s behavioral patterns, sta-

tus and the personality influencer. In J. T. Li, A. S. Tusk, & E. Weldon (Eds.), Management and organizations in

the Chinese context (pp. 283-302). London: Macmillan.

Thakur, G. P., & Thakur, M. (1973). Some Indian data on reliability estimates of Forms A and B of the EPI. Journal

of Personality Assessment, 37, 372-374.

Van de Vijver, F. J. R., & Leung, K. (1997). Methods and data analysis of comparative research. In J. W. Berry, Y. H.

Poortinga, & J. Pandey (Eds.), Theory and Method,Vol. 1 of Handbook of Cross-Cultural Psychology (pp. 257-

300, 2nd Ed.). Boston: Allyn & Bacon.

Wiggins, J. S. (1979). A psychological taxonomy of trait-descriptive terms: The interpersonal domain. Journal of

Personality and Social Psychology, 37, 395-412.

Wrigley, C. S., & Neuhaus, J. O. (1955). The matching of two sets of factors. American Psychologist, 10, 418-419.

Yang, K. S., & Bond, M. H. (1990). Exploring implicit personality theories with indigenous or imported constructs:

The Chinese case. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 58, 1087-1095.

Yik, M. S., & Bond, M. H. (1993). Exploring the dimensions of Chinese person perception with indigenous and

imported constructs: Creating a culturally balanced scale. International Journal of Psychology, 28, 75-95.

Zhang, J. X. (1997). Distinction between general trust and specific trust: Their unique patterns with personality

trait domains, distinct roles in interpersonal situations, and different function in path models of trusting behav-

ior. Unpublished doctoral dissertation, Chinese University of Hong Kong.

Zhang, J. X., & Bond, M. H. (1998). Personality and filial piety among college students in two Chinese societies:

The added values of indigenous constructs. Journal of Cross-Cultural Psychology, 29, 402-417.

Fanny M. Cheung (Ph.D., University of Minnesota) is a professor of psychology and chairperson of the

Department of Psychology at the Chinese University of Hong Kong. She is the principal investigator of the

CPAI project. She is responsible for the adaptation and publication of the Chinese MMPI, MMPI-2, and

MMPI-A. Her research interests are personality assessment, Chinese psychopathology, and gender studies.

Shu Fai Cheung (Ph.D., Chinese University of Hong Kong) is currently postdoctoral fellow at the Depart-

ment of Psychology, the Chinese University of Hong Kong. His research interests are personality assess-

ment, meta-analysis, structural equation modeling, and the relationship between attitude and behavior.

Kwok Leung (Ph.D., University of Illinois, Champaign–Urbana) is currently a professor of management at

City University of Hong Kong. He has published widely on the topics of justice, conflict, and cross-cultural

psychology. He is the current editor of Asian Journal of Social Psychology, an associate editor of Asia

Pacific Journal of Management, and a departmental editor of Journal of International Business Studies.

Colleen Ward is currently a professor and head of School of Psychology at Victoria University of Wellington,

New Zealand. She has previously worked at the University of the West Indies, Trinidad; the Science Univer-

sity of Malaysia; National University of Singapore; and Canterbury University, New Zealand. She is former

Secretary General of IACCP. Her primary interest is in acculturation, and her most recent book, co-

authored with Stephen Bochner and Adrian Furnham, The Psychology of Culture Shock, was published in

2001. She also has interests in cross-cultural comparison and measurement.

Frederick Leong is a professor of psychology and director of the Counseling Psychology Program at Ohio

State University. He obtained his Ph.D. from the University of Maryland with a double specialty in counsel-

ing and industrial/organizational psychology. He has authored or coauthored 85 articles in various coun-

seling and psychology journals and 45 book chapters. He is a Fellow of the American Psychological Associ-

ation (Divisions 1, 2, 17, 45, and 52) and the recipient of the 1998 Distinguished Contributions Award from

the Asian American Psychological Association and the 1999 John Holland Award from the APA Division of

Counseling Psychology. His major research interests are in vocational psychology (career development of

ethnic minorities), cross-cultural psychology (particularly culture and mental health and cross-cultural

psychotherapy), and organizational behavior.

Downloaded from jcc.sagepub.com at University of Ulster Library on March 6, 2015

You might also like

- Interview-Based Ratings of DSM-IV Axis IIDSM-5 Section II Personality Disorder Symptoms in Consecutively Admitted Insomnia PatientsDocument25 pagesInterview-Based Ratings of DSM-IV Axis IIDSM-5 Section II Personality Disorder Symptoms in Consecutively Admitted Insomnia PatientsSiti Awalia RamadhaniNo ratings yet

- Definitions of MmpiDocument11 pagesDefinitions of MmpiBook ReaderNo ratings yet

- Key Words: Neuropsychological Evaluation, Standardized AssessmentDocument20 pagesKey Words: Neuropsychological Evaluation, Standardized AssessmentRALUCA COSMINA BUDIANNo ratings yet

- APA DSM 5 Paraphilic DisordersDocument2 pagesAPA DSM 5 Paraphilic DisordersAli FenNo ratings yet

- DSM 5 Intellectual Disability Fact SheetDocument2 pagesDSM 5 Intellectual Disability Fact SheetMelissa Ortega MaguiñaNo ratings yet

- CBT Labelling EmotionsDocument3 pagesCBT Labelling Emotionskicaanu100% (1)

- Interrupting Internalized Racial Oppression - A Community Based ACT InterventionDocument5 pagesInterrupting Internalized Racial Oppression - A Community Based ACT InterventionLINA MARIA MORENONo ratings yet

- Knots R.d.laingDocument12 pagesKnots R.d.lainglandburender100% (1)

- Asperger's Syndrome in AdultsDocument7 pagesAsperger's Syndrome in AdultsWillyOaksNo ratings yet

- List Oflist of 60 Coping Strategies For Hallucinations 60 Coping Strategies For HallucinationsDocument2 pagesList Oflist of 60 Coping Strategies For Hallucinations 60 Coping Strategies For HallucinationsDani CorbuNo ratings yet

- Interoceptive Awareness Skills For Emotion RegulationDocument12 pagesInteroceptive Awareness Skills For Emotion RegulationPoze InstalatiiNo ratings yet

- Cleopatra PDFDocument205 pagesCleopatra PDFlordmiguel100% (1)

- Setting Up A Scoring Sheet: Scoring Sheet With 3 Vertical Columns First Column "Name of Schema" RedDocument2 pagesSetting Up A Scoring Sheet: Scoring Sheet With 3 Vertical Columns First Column "Name of Schema" RedTatiana CastañedaNo ratings yet

- TransDocument20 pagesTransCamilo Echeverri BernalNo ratings yet

- Recovery and Hearing Voices: Resources, Reading List and Links: USADocument7 pagesRecovery and Hearing Voices: Resources, Reading List and Links: USAAivlys100% (1)

- The Self in PsychotherapyDocument26 pagesThe Self in PsychotherapyccvmdNo ratings yet

- Exposition Universelle de 1889Document28 pagesExposition Universelle de 1889Kristan Tybuszewski100% (1)