Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Data Response 2

Uploaded by

Saad AhmedCopyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Data Response 2

Uploaded by

Saad AhmedCopyright:

Available Formats

2

Section A

Answer all questions.

1 Egypt’s economic difficulties

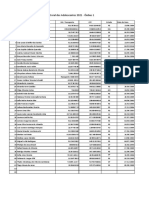

Table 1.1: Egypt, selected economic indicators, 2014–2019

Consumer Price Current account Unemployment

Index balance rate

(base year 2000) (US$ billion) (% of total labour force)

2014 304 −2.356 13.4

2015 337 −12.182 12.9

2016 371 −18.659 12.7

2017 453* not available 12.6*

2018 530* not available 11.8*

2019 587* not available 10.7*

* International Monetary Fund (IMF) estimates

Source: International Monetary Fund, World Economic Outlook Database, April 2017

Egypt’s Central Agency for Public Mobilization and Statistics (CAPMAS) reported that Egypt’s

annual inflation rate surged to 32.9% in April 2017, compared to 10.9% in 2016. This is considerably

higher than the expected rate that was estimated by the IMF shown in Table 1.1.

Inflation had been rising in Egypt since the decision of the Central Bank of Egypt (CBE) in

November 2016 to float Egypt’s currency (the Egyptian pound) in a move that caused a 50%

depreciation in its value against the US dollar. This came as part of the Egyptian government’s

reform programme, started in 2014, to reduce the budget deficit and acquire a US$12 billion loan

from the IMF to ease the US dollar shortage that had restricted Egypt’s business activity.

A macroeconomic research group has said that ‘The sharp rise in inflation could largely be

attributed to the effects of the weaker Egyptian pound. Inflation was also made worse by levying a

new indirect tax called Value Added Tax (VAT), and cutting subsidies on energy in November 2016.’

On the same day as the CBE floated the Egyptian pound it raised the interest rate by 3 percentage

points to 14.75%.

Egypt’s VAT replaced the previous sales tax, which economists said created market distortions.

It was expected to broaden the tax base in a country where the government struggles to collect

income tax because of a large informal economy and widespread tax avoidance. The VAT does

not apply to basic goods and services to protect the poor.

Source: Islam Al Naggar, Egypt Today, 10 May 2017, and Reuters, 29 August 2016

© UCLES 2019 9708/22/M/J/19

3

(a) (i) What happened to Egypt’s current account balance between 2014 and 2016? [1]

(ii) With reference to Table 1.1 calculate the percentage rate of inflation in Egypt between

2016 and 2017 that was estimated by the IMF. [1]

(b) Identify two Canons of Taxation satisfied by Egypt’s new VAT. [2]

(c) Explain how the decline in the value of the Egyptian pound could cause demand-pull inflation

and cost-push inflation in Egypt. [4]

(d) Explain how the estimated changes in unemployment in Table 1.1 might be expected to affect

the current account balance of Egypt after 2016. [6]

(e) Discuss whether the Egyptian government’s fiscal and monetary policies in the article are

likely to succeed in curing the inflation problem. [6]

Section B

Answer one question.

2 (a) Explain how economists use the concept of elasticity to distinguish between inferior goods

and necessary goods when consumer incomes change. [8]

(b) Discuss how businesses might attempt to change the price elasticity of demand for their

products and consider which approach is most likely to be successful. [12]

3 (a) Distinguish between regressive and progressive taxes and explain whether you would use an

income tax or a specific indirect tax to make post-tax incomes more equal. [8]

(b) Discuss whether subsidies on the production of all types of good will lead to an improved

allocation of resources. [12]

4 (a) Explain, using examples, what is meant by ‘protectionism’ and show with the help of a diagram

how export subsidies can be considered as a form of protectionism. [8]

(b) Discuss the arguments that are used to justify protectionism and consider whether these

arguments can ever be justified. [12]

© UCLES 2019 9708/22/M/J/19

You might also like

- Cambridge International Advanced Subsidiary and Advanced LevelDocument4 pagesCambridge International Advanced Subsidiary and Advanced LevelSyed Amir AhmedNo ratings yet

- Cambridge International AS & A Level: ECONOMICS 9708/43Document4 pagesCambridge International AS & A Level: ECONOMICS 9708/43KeithNo ratings yet

- Cambridge International AS & A Level: ECONOMICS 9708/02Document4 pagesCambridge International AS & A Level: ECONOMICS 9708/02Hasnain ShahNo ratings yet

- Cambridge International AS & A Level: ECONOMICS 9708/22Document4 pagesCambridge International AS & A Level: ECONOMICS 9708/22tawandaNo ratings yet

- Cambridge International AS & A Level: ECONOMICS 9708/22Document8 pagesCambridge International AS & A Level: ECONOMICS 9708/22kitszimbabweNo ratings yet

- ECONOMICS P2 M18 To J22 C.VDocument392 pagesECONOMICS P2 M18 To J22 C.VsukaNo ratings yet

- November 2020 (v3) QP - Paper 4 CAIE Economics A-LevelDocument4 pagesNovember 2020 (v3) QP - Paper 4 CAIE Economics A-LevellongNo ratings yet

- 9708 w19 QP 42 PDFDocument4 pages9708 w19 QP 42 PDFkazamNo ratings yet

- Cambridge International Advanced Subsidiary and Advanced LevelDocument4 pagesCambridge International Advanced Subsidiary and Advanced LevelShah RahiNo ratings yet

- Cambridge International AS & A Level: ECONOMICS 9708/43Document4 pagesCambridge International AS & A Level: ECONOMICS 9708/43tawandaNo ratings yet

- Cambridge International AS & A Level: ECONOMICS 9708/42Document4 pagesCambridge International AS & A Level: ECONOMICS 9708/42tawandaNo ratings yet

- Cambridge International AS & A Level: ECONOMICS 9708/22Document4 pagesCambridge International AS & A Level: ECONOMICS 9708/22tawandaNo ratings yet

- Cambridge International General Certificate of Secondary EducationDocument4 pagesCambridge International General Certificate of Secondary EducationShadyNo ratings yet

- Cambridge International AS & A Level: ECONOMICS 9708/41Document4 pagesCambridge International AS & A Level: ECONOMICS 9708/41Poh CarineNo ratings yet

- 03 9708 22 2023 2RP Afp M23 20022023Document4 pages03 9708 22 2023 2RP Afp M23 20022023Kalsoom SoniNo ratings yet

- Cambridge International AS & A Level: ECONOMICS 9708/21Document4 pagesCambridge International AS & A Level: ECONOMICS 9708/21tawandaNo ratings yet

- Igcse-Economics-Online-Examination (Without Edits)Document9 pagesIgcse-Economics-Online-Examination (Without Edits)Zuhair MahmudNo ratings yet

- 2022 Jc2 h2 Prelims p2 Qp-3Document1 page2022 Jc2 h2 Prelims p2 Qp-3Sebastian ZhangNo ratings yet

- 9708 Economics: MARK SCHEME For The October/November 2010 Question Paper For The Guidance of TeachersDocument4 pages9708 Economics: MARK SCHEME For The October/November 2010 Question Paper For The Guidance of TeacherskutsofatsoNo ratings yet

- Components of Ad Dp2Document7 pagesComponents of Ad Dp2sunshineNo ratings yet

- 9708 m17 QP 42Document4 pages9708 m17 QP 42MelissaNo ratings yet

- Ecr p2 PDFDocument60 pagesEcr p2 PDFShehzad QureshiNo ratings yet

- Cambridge International Advanced Subsidiary and Advanced LevelDocument4 pagesCambridge International Advanced Subsidiary and Advanced LevelDanny DrinkwaterNo ratings yet

- Cambridge International Advanced Subsidiary and Advanced LevelDocument4 pagesCambridge International Advanced Subsidiary and Advanced LevelkutsofatsoNo ratings yet

- DBA Macroeconomics Tutorial Questions 2017Document10 pagesDBA Macroeconomics Tutorial Questions 2017Limatono Nixon 7033RVXLNo ratings yet

- 2021 J2 H2 Prelim P2 9757eeDocument3 pages2021 J2 H2 Prelim P2 9757eeSNo ratings yet

- Cambridge International AS & A Level: ECONOMICS 9708/21Document4 pagesCambridge International AS & A Level: ECONOMICS 9708/21Aina AmirNo ratings yet

- Cambridge International AS & A Level: Economics 9708/23Document4 pagesCambridge International AS & A Level: Economics 9708/23Ibrahim AbidNo ratings yet

- Cambridge International AS & A Level: ECONOMICS 9708/22Document4 pagesCambridge International AS & A Level: ECONOMICS 9708/22Nguyen KevinNo ratings yet

- Cambridge International Advanced Subsidiary and Advanced LevelDocument4 pagesCambridge International Advanced Subsidiary and Advanced LevelWai HponeNo ratings yet

- Economics: PAPER 4 Data Response and Essays (Extension)Document4 pagesEconomics: PAPER 4 Data Response and Essays (Extension)roukaiya_peerkhanNo ratings yet

- June 2018 Question Paper 21Document8 pagesJune 2018 Question Paper 21Walter ShonisaniNo ratings yet

- Cambridge International General Certificate of Secondary EducationDocument8 pagesCambridge International General Certificate of Secondary Education8jjkm87pynNo ratings yet

- 9708 w03 QP 4Document4 pages9708 w03 QP 4michael hengNo ratings yet

- Cambridge International AS & A Level: Economics 9708/42Document4 pagesCambridge International AS & A Level: Economics 9708/42Melissa ChaiNo ratings yet

- Cambridge International AS & A Level: ECONOMICS 9708/21Document4 pagesCambridge International AS & A Level: ECONOMICS 9708/21Sraboni ChowdhuryNo ratings yet

- Cambridge Ordinary LevelDocument4 pagesCambridge Ordinary LevelSanjeewani WedamullaNo ratings yet

- University of Cambridge International Examinations General Certificate of Education Advanced LevelDocument4 pagesUniversity of Cambridge International Examinations General Certificate of Education Advanced LevelxuehanyujoyNo ratings yet

- Cambridge International AS & A Level: ECONOMICS 9708/21Document4 pagesCambridge International AS & A Level: ECONOMICS 9708/21李立No ratings yet

- 0455 - m18 - 2 - 2 - QP IGCSEDocument8 pages0455 - m18 - 2 - 2 - QP IGCSEloveupdownNo ratings yet

- Cambridge International AS & A Level: ECONOMICS 9708/22Document4 pagesCambridge International AS & A Level: ECONOMICS 9708/22sharmat1963No ratings yet

- Cambridge International AS & A Level: ECONOMICS 9708/23Document4 pagesCambridge International AS & A Level: ECONOMICS 9708/23santu220875No ratings yet

- Fla Final PlanDocument35 pagesFla Final Planmimo11112222No ratings yet

- Cambridge International AS & A Level: ECONOMICS 9708/41Document4 pagesCambridge International AS & A Level: ECONOMICS 9708/41KeithNo ratings yet

- Cambridge International General Certificate of Secondary EducationDocument8 pagesCambridge International General Certificate of Secondary EducationUzma TahirNo ratings yet

- Cambridge Ordinary Level: Cambridge Assessment International EducationDocument8 pagesCambridge Ordinary Level: Cambridge Assessment International EducationVrushtiNo ratings yet

- Cambridge International AS & A Level: Economics 9708/43Document5 pagesCambridge International AS & A Level: Economics 9708/43Melissa ChaiNo ratings yet

- Cambridge Ordinary Level: Cambridge Assessment International EducationDocument8 pagesCambridge Ordinary Level: Cambridge Assessment International Educationamal shrainNo ratings yet

- Cambridge O Level: ECONOMICS 2281/21Document8 pagesCambridge O Level: ECONOMICS 2281/21Fred SaneNo ratings yet

- Online Special Examination September 2021: Economics Exam Iii 12 (Cambridge) .........Document4 pagesOnline Special Examination September 2021: Economics Exam Iii 12 (Cambridge) .........Chirath FernandoNo ratings yet

- 9708 w17 QP 21 PDFDocument4 pages9708 w17 QP 21 PDFAhmed KhurramNo ratings yet

- 0455 w17 QP 22Document8 pages0455 w17 QP 22Fahad AliNo ratings yet

- Cambridge IGCSE: ECONOMICS 0455/22Document8 pagesCambridge IGCSE: ECONOMICS 0455/22Nii SowahNo ratings yet

- Cambridge International AS & A Level: ECONOMICS 9708/42Document4 pagesCambridge International AS & A Level: ECONOMICS 9708/42MoynaNo ratings yet

- (1205) Q9-14 - H1 Econ IndicatorsDocument7 pages(1205) Q9-14 - H1 Econ IndicatorsDavid LimNo ratings yet

- Cambridge IGCSE: ECONOMICS 0455/21Document8 pagesCambridge IGCSE: ECONOMICS 0455/21Avikamm AgrawalNo ratings yet

- JUNE 2022 O LevelDocument8 pagesJUNE 2022 O Level2e336svetlana sawlaniNo ratings yet

- Cambridge O Level: ECONOMICS 2281/21Document8 pagesCambridge O Level: ECONOMICS 2281/21Shadman ChowdhuryNo ratings yet

- Global Financial Crisis and Short Run Prospects by Raghbander ShahDocument24 pagesGlobal Financial Crisis and Short Run Prospects by Raghbander ShahakshaywaikersNo ratings yet

- A Comparative Analysis of Tax Administration in Asia and the Pacific: Fifth EditionFrom EverandA Comparative Analysis of Tax Administration in Asia and the Pacific: Fifth EditionNo ratings yet

- Case Study Group 4Document15 pagesCase Study Group 4000No ratings yet

- Allstate Car Application - Sign & ReturnDocument6 pagesAllstate Car Application - Sign & Return廖承钰No ratings yet

- Pidato Bhs Inggris The HomelandDocument1 pagePidato Bhs Inggris The HomelandYeni NuraeniNo ratings yet

- Eo - Bhert 2023Document3 pagesEo - Bhert 2023Cyrus John Velarde100% (1)

- Project Initiation Document (Pid) : PurposeDocument17 pagesProject Initiation Document (Pid) : PurposelucozzadeNo ratings yet

- Running Head: Problem Set # 2Document4 pagesRunning Head: Problem Set # 2aksNo ratings yet

- ACR Format Assisstant and ClerkDocument3 pagesACR Format Assisstant and ClerkJalil badnasebNo ratings yet

- Coral Dos Adolescentes 2021 - Ônibus 1: Num Nome RG / Passaporte CPF Estado Data de NascDocument1 pageCoral Dos Adolescentes 2021 - Ônibus 1: Num Nome RG / Passaporte CPF Estado Data de NascGabriel Kuhs da RosaNo ratings yet

- Completed Jen and Larry's Mini Case Study Working Papers Fall 2014Document10 pagesCompleted Jen and Larry's Mini Case Study Working Papers Fall 2014ZachLoving100% (1)

- Hedge Fund Ranking 1yr 2012Document53 pagesHedge Fund Ranking 1yr 2012Finser GroupNo ratings yet

- Are You ... Already?: BIM ReadyDocument8 pagesAre You ... Already?: BIM ReadyShakti NagrareNo ratings yet

- Enrollment DatesDocument28 pagesEnrollment DatesEdsel Ray VallinasNo ratings yet

- Priyanshu Mts Answer KeyDocument34 pagesPriyanshu Mts Answer KeyAnima BalNo ratings yet

- Term Paper Air PollutionDocument4 pagesTerm Paper Air Pollutionaflsnggww100% (1)

- Cases 1Document79 pagesCases 1Bechay PallasigueNo ratings yet

- Problem 7 Bonds Payable - Straight Line Method Journal Entries Date Account Title & ExplanationDocument15 pagesProblem 7 Bonds Payable - Straight Line Method Journal Entries Date Account Title & ExplanationLovely Anne Dela CruzNo ratings yet

- Invoice: Page 1 of 2Document2 pagesInvoice: Page 1 of 2Gergo JuhaszNo ratings yet

- Grile EnglezaDocument3 pagesGrile Englezakis10No ratings yet

- 304 1 ET V1 S1 - File1Document10 pages304 1 ET V1 S1 - File1Frances Gallano Guzman AplanNo ratings yet

- Does The Stereotypical Personality Reported For The Male Police Officer Fit That of The Female Police OfficerDocument2 pagesDoes The Stereotypical Personality Reported For The Male Police Officer Fit That of The Female Police OfficerIwant HotbabesNo ratings yet

- Blcok 5 MCO 7 Unit 2Document12 pagesBlcok 5 MCO 7 Unit 2Tushar SharmaNo ratings yet

- Ice Cream CaseDocument7 pagesIce Cream Casesardar hussainNo ratings yet

- INFJ SummaryDocument3 pagesINFJ SummarydisbuliaNo ratings yet

- Greek Mythology ReviewerDocument12 pagesGreek Mythology ReviewerSyra JasmineNo ratings yet

- On Islamic Branding Brands As Good DeedsDocument17 pagesOn Islamic Branding Brands As Good Deedstried meNo ratings yet

- Unit 2.exercisesDocument8 pagesUnit 2.exercisesclaudiazdeandresNo ratings yet

- Gillette vs. EnergizerDocument5 pagesGillette vs. EnergizerAshish Singh RainuNo ratings yet

- Updated 2 Campo Santo de La LomaDocument64 pagesUpdated 2 Campo Santo de La LomaRania Mae BalmesNo ratings yet

- Mt-Requirement-01 - Feu CalendarDocument18 pagesMt-Requirement-01 - Feu CalendarGreen ArcNo ratings yet

- English L 18 - With AnswersDocument9 pagesEnglish L 18 - With AnswersErin MalfoyNo ratings yet