Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Article Three

Article Three

Uploaded by

林采琪0 ratings0% found this document useful (0 votes)

25 views6 pagesCopyright

© © All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

DOCX, PDF, TXT or read online from Scribd

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

© All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

Download as DOCX, PDF, TXT or read online from Scribd

0 ratings0% found this document useful (0 votes)

25 views6 pagesArticle Three

Article Three

Uploaded by

林采琪Copyright:

© All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

Download as DOCX, PDF, TXT or read online from Scribd

You are on page 1of 6

Article Three

(CNN)Hidden in the halls of the Fashion Institute of Technology in New York are

historic textiles and glamorous garments, many of which hold secrets from years

past.

Yet no matter how aesthetically unique or historically significant a particular piece of

fashion may be, most visitors to the museum typically ask one question, said Emma

McClendon, the museum's associate curator of costume.

"People come and always want to know what size something is," said McClendon,

who organized the exhibition "The Body: Fashion and Physique," about the history of

the idealized body type in fashion, which is on display until May.

"Whether it's contemporary or 19th century, they want to know what size it is or

what size it would correlate to, or what measurement it is," she said. "We as a

culture, as a society, are obsessed with size. It's become connected to our identity as

people."

This obsession fuels societal pressures to appear a certain way and to have a certain

body type, particularly among young women, stemming from a cultural construct of

the "ideal" body, which has in turn changed over time -- as long ago as pre-history.

Thousands of years ago, sculptures and artworks portrayed curvaceous, thickset

silhouettes. More recently, in the late 20th century, thin, waif-like models filled the

pages of fashion magazines. Now, shapely backsides are celebrated with "likes" on

social media.

To mark International Women's Day, we explore how this "ideal" is ever-changing,

forming a complex history throughout art and fashion -- with damaging impacts on

women who try to conform in each era.

Prehistory-1900s: A focus on full-figured silhouettes

Some of the earliest known representations of a woman's body are the "Venus

figurines," small statues from 23,000 to 25,000 years ago in Europe.

The figurines -- including the "Venus of Willendorf," found in 1908 at Willendorf,

Austria -- portray round, pear-shaped women's bodies, many with large breasts.

Experts have long debated whether the figurines symbolize attractiveness or fertility.

In ancient Greece, Aphrodite, the goddess of sexual love and beauty, was often

portrayed with curves.

A statue commonly thought to represent Aphrodite, called the Venus de Milo,

depicts small breasts but is shaped with a twisted figure and elongated body,

characteristic of that time period.

Artists continued to portray the "ideal" woman as curvy and voluptuous all the way

through to the 17th and 18th centuries.

The 17th century Flemish painter Peter Paul Rubens was even the namesake of the

term "rubenesque," meaning plump or rounded, as he often depicted women with

curvy body types.

To achieve this in reality, the corset became a popular undergarment among women

in the Western world from the late Renaissance into the 20th century. It helped

accentuate a woman's curves by holding in her waist and supporting her bosom.

As societal views of a woman's body changed over time, so did the shape and

construction of the corset, also sometimes referred to as stays.

The 18th-century stay mirrored a cone-shaped silhouette, but by the 1790s, shorter

stays emerged, resembling proto-brassieres, which complemented the new fashion

trend of high-waisted dresses.

"There was an emphasis on under-structure to shape the body. That's true for skirts

as well," McClendon said.

"Whether it be hooped or caged or padded, under-structures were worn around the

lower body to create a specific volume," she said. "In the 18th and the 19th

centuries, the idealized fashionable body -- so this is talking specifically about what's

promoted in the fashion industry itself -- was much more curvaceous and much more

voluptuous."

In the 1890s, American artist Charles Dana Gibson drew images of tall, slim-waisted

yet voluptuous women in illustrations for mainstream magazines, and these

depictions of the new feminine ideal were referred to as the "Gibson Girl."

Going into the early 20th century, the portrayal of women's bodies in art was

constantly evolving, as seen in French artist Henri Matisse's oil paintings showing

lithe, flowing bodies and then Spanish artist Pablo Picasso's paintings showing

plump, contorted nude bodies in vivid detail.

"Then, in the 20th century, there's a very defined shift towards an increasingly young

and increasingly kind of athletic and slender body," McClendon said.

It remains somewhat unclear what triggered this shift, but the interest in thin bodies

would continue well into the modern day.

1920s-'50s: Eating disorders -- and a changing bust-to-waist ratio

The rise of the 1920s flapper reflected this shift toward the Western world desiring a

more slim physique.

As slender women's bodies started to appear in magazines In the mid-1920s, an

epidemic of eating disorders also occurred among young women, according to some

studies.

"The highest reported prevalence of disordered eating occurred during the 1920s

and 1980s, the two periods during which the 'ideal woman' was thinnest in US

history," researchers at the University of Wisconsin-Madison wrote in a paper in the

Journal of Communication in 1997.

The bust-to-waist ratios among women featured in the magazines Vogue and Ladies

Home Journal dwindled by about 60% between 1901 and 1925, according to an

analysis in a study published in the journal Sex Roles in 1986.

"Such findings would constitute empirical support for the hypothesis that the mass

media play a role in promoting the slim standard of bodily attractiveness fashionable

among women," the researchers wrote. "Through this standard perhaps the eating

disorders that have become increasingly common."

By the late 1940s, that ratio climbed back, increasing by about one-third in both

magazines, the study found.

Around that time, the fuller body types of pinup models and actresses like Marilyn

Monroe grew in popularity, and the first issue of Playboy magazine was published in

1953.

The ratio then dropped again.

By the late 1960s, the ratio had returned to approximately the same level it was in

the 1920s, the study found.

1960s-'70s: 'A complete fallacy' revealed

The historical shift from a rounded to a thinner body preference led to the rise of

British fashion model Lesley Lawson, known as Twiggy, and other slender models.

They seemed to symbolize a shift away from the corsets and pinup girls of years past.

Simultaneously, the "second wave" of the women's rights movement began.

In 1960, the US Food and Drug Administration approved the birth control pill. In

1963, women's rights activist Betty Friedan published her book "The Feminine

Mystique." In 1966, the National Organization for Women in the US was founded.

"People talk about the '60s, even the '70s, as this moment when the woman's body

is freed," McClendon said. "But that notion that women were all of a sudden

completely free in their bodies after that point is a complete fallacy."

Although women were no longer squeezing themselves into corsets, the media

messaging and societal pressures to adhere to an "ideal" body still continued. That

"ideal" was instead a very young and thin body type.

"Foundation garments were replaced by diet and exercise," McClendon said.

What remained was the "notion that in order for your body to be truly fashionable,

you had to probably change it some way," she said. "You had to maintain it in some

way."

The incidence of severe anorexia nervosa requiring hospital admission rose

significant during the 1960s and '70s to reach a plateau, according to a study in the

journal Current Psychiatry Reports in 2012.

1980s-'90s: The rise of the supermodels -- and obesity

Though images of thin women continued to be mainstream well into the 1980s,

there became more of an emphasis on strong, athletic and toned body types.

"We do see an interest in a fit, toned, strong body -- still lean but athletic. So this is

where you get the emphasis on those classic supermodels like Cindy Crawford and

Naomi Campbell," McClendon said.

Though there still was an emphasis on a thin body, there was also emphasis on a

healthier and fitter body.

Then, by the '90s, that emphasis shifted back to more skinny, waif-like body types.

"The term that gets so much associated with that decade is the '90s is the moment of

the waif," McClendon said. "Kate Moss is the epitome of that. Her nickname was 'the

waif.' She became a household name from Calvin Klein ads in the early 1990s."

Anorexia nervosa was associated with the highest rate of mortality among all mental

disorders during the 1990s, according to the study in Current Psychiatry Reports.

Around that same time, the World Health Organization began sounding the alarm

about the growing global obesity epidemic.

Obesity means a person has too much body fat, and it can increase the risk of health

problems including diabetes, heart disease, stroke, arthritis and even some cancers.

The prevalence of obesity sharply increased in the '90s. An estimated 200 million

adults worldwide were obese, and that number rose to more than 300 million by

2000, according to the WHO.

As images of obesity flashed across media screens as a part of public health outreach

efforts, in contrast so did images of skinny models, McClendon said.

"We begin to see a stark divide in the way bodies are presented across the media,

with extreme thinness celebrated in fashion imagery while larger bodies are

highlighted as 'unhealthy' and bad in reporting on obesity. And we begin to judge our

own bodies through the same binary lens," she said.

So, it seems, the psychological impacts from that included impacts on body image.

2000s: Loss of self-confidence

Nearly a third of children aged 5 to 6 in the US select an ideal body size that is

thinner than their current perceived size when given the option, and by age 7, one in

four children has engaged in some kind of dieting behavior, according to a Common

Sense Media report published in 2015.

The report, based on a review of existing studies on body image and media, also

found that between 1999 and 2006, hospitalizations for eating disorders in the US

spiked 119% among children under age 12.

In the United Kingdom, nearly a quarter, 24%, of child care professionals have

reported seeing signs of body confidence issues in children aged 3 to 5, according to

research from the Professional Association for Childcare and Early Years published in

2016.

Another study found that the incidence rate of eating disorders for people aged 10 to

49 in the UK rose from 32.3 per 100,000 in 2000 to 37.2 per 100,000 in 2009. Yet the

peak age of onset for an eating disorder diagnosis in women was during adolescence,

between 15 and 19, according to that study.

"When kids are entering adolescence, they're developing their own identity and

trying to figure out what's socially acceptable so when they're inundated with images

of a particular body type in appealing scenarios, they're more apt to absorb the idea

that that particular body type is ideal," said Sierra Filucci, executive editor of

parenting content and distribution for Common Sense Media, a nonprofit

organization focused on helping children, parents and educators navigate the world

of media and technology.

Among a sample of 6,411 South Africans 15 and older, 45.3% reported being

generally dissatisfied about their body size, according to a study published in the

journal BMC Public Health in 2015.

Overweight and obese study participants underestimated their body size and desired

to be thinner, whereas normal and underweight participants overestimated their

body size and desired to be fatter, according to the study. Only 12% and 10.1% of

participants attempted to lose or gain weight, respectively, that study found.

2010s: Embracing diversity

Since the start of the 21st century, there has been a shift toward celebrating diverse

body types in the media and fashion. That trend appears to correlate with the use of

social media, where diverse types are represented by everyday users online.

Of course, social media can also give some teens a negative body image. A Common

Sense Media survey found that more than a quarter of teens who are active online

stress about how they look in posted photos.

On the other hand, the rise of social media has allowed for real women to celebrate

real body types. McClendon even called social media a "frontier for body-positive

expression."

"Over the course of the last 50-plus years, the American ideal has shifted from curvy

to androgynous to muscular and everything in between," Filucci said.

"As these ideals change, they are reflected and reinforced in the culture through

media -- whether it's fine art or advertising billboards or music videos," she said,

adding that however those ideals are presented, they can still influence the body

image of young women and even children.

In 2007, the first episode of "Keeping Up With the Kardashians" aired in the US, and

ever since, the Kardashian sisters' bodies have become a frequent focus of celebrity

weekly magazines, ushering in new curvaceous body ideals.

In 2015, Robyn Lawley was the first plus-size model featured in Sports Illustrated's

swimsuit issue.

In 2016, fashion designer Christian Siriano featured five plus-size models in his show

during New York Fashion Week. That same year, toy manufacturing company Mattel

debuted a line of Barbie dolls depicting diverse body types, including curvy shapes.

Last year, reality show Project Runway, included models ranging from size 0 to 22 for

the first time in its history.

As for the current state of beauty, some health experts are warning of the dangers of

the "selfie" and social media culture as influencing body image, as the rise of

Instagram and YouTube has allowed for the bodies of everyday people to be

idealized, not just the bodies of supermodels.

Yet "when that body type is different from the one girls and young women have, they

can be vulnerable to low self-esteem," Filucci said, adding that parents can help

children develop positive body images through role modeling.

"That means refraining from negative body talk both for themselves and others and

speaking positively about their own bodies -- especially emphasizing their body's

abilities like strength, flexibility, resilience, adaptability ... rather than attractiveness,"

she said. "Parents can also look for media that reinforces positive body images and

avoids gender stereotypes."

You might also like

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)From EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Rating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (122)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryFrom EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (231)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceFrom EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (590)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaFrom EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (266)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItFrom EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (844)

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeFrom EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (5810)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeFrom EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (540)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyFrom EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (2259)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesFrom EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (822)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingFrom EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (401)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersFrom EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (348)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreFrom EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (1092)

- Brand Identity Prism - Assignment 1 PDFDocument38 pagesBrand Identity Prism - Assignment 1 PDFMis Khushboo B75% (4)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerFrom EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (271)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceFrom EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (897)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnFrom EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (234)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)From EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Rating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (98)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureFrom EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (474)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealFrom EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (74)

- Biker JacketDocument33 pagesBiker JacketLiliana Falcón0% (1)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaFrom EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (45)

- Sustainable Fashion: A Survey On Global PerspectivesDocument34 pagesSustainable Fashion: A Survey On Global PerspectivesAkankshaNo ratings yet

- Fashion Trends and Their Impact On The Society: September 2015Document11 pagesFashion Trends and Their Impact On The Society: September 2015ihtxamNo ratings yet

- Marketing Management Project: By: Om Shinde J066 Shashank Sharma J062 Miit Matlani J034 Megh Chavan J012Document20 pagesMarketing Management Project: By: Om Shinde J066 Shashank Sharma J062 Miit Matlani J034 Megh Chavan J012MRIGANK SHARMANo ratings yet

- Fashion of Early 20th Century Part1Document38 pagesFashion of Early 20th Century Part1MaggieWoods100% (7)

- Simple Modern Sewing: 8 Basic Patterns To Create 25 Favorite GarmentsDocument8 pagesSimple Modern Sewing: 8 Basic Patterns To Create 25 Favorite GarmentsInterweave67% (3)

- Necklines: Submitted To:-Mrs. Sagarika Submitted By: - Shobha (12010422) Babita (12010429) Himani (12010430)Document24 pagesNecklines: Submitted To:-Mrs. Sagarika Submitted By: - Shobha (12010422) Babita (12010429) Himani (12010430)Sagarika AdityaNo ratings yet

- Fashion Design Business PlanDocument10 pagesFashion Design Business Planbakare ridwanullahiNo ratings yet

- Demand Forescasting in The Fashion IndustryDocument7 pagesDemand Forescasting in The Fashion Industrycludi94No ratings yet

- Mosaic 1 - Extra Practice Unit 7 SB PDFDocument6 pagesMosaic 1 - Extra Practice Unit 7 SB PDFMontse50% (2)

- Pattern Making IntroductionDocument26 pagesPattern Making Introductionsonamanand2008100% (1)

- Lantern FestivalDocument11 pagesLantern Festival林采琪No ratings yet

- Control AI Now or Brace For Nightmare Future, Experts Warn by Sherisse PhamDocument2 pagesControl AI Now or Brace For Nightmare Future, Experts Warn by Sherisse Pham林采琪No ratings yet

- Though Climate Change Is A Crisis, The Population Threat Is Even Worse Stephen EmmottDocument3 pagesThough Climate Change Is A Crisis, The Population Threat Is Even Worse Stephen Emmott林采琪No ratings yet

- Article FourDocument4 pagesArticle Four林采琪No ratings yet

- Biesak Wesselman Influence of Modernism On FashionDocument24 pagesBiesak Wesselman Influence of Modernism On FashionKrista HicksNo ratings yet

- Tauer & Johnson Best Sellers Mini-CatalogDocument9 pagesTauer & Johnson Best Sellers Mini-Catalogshannonie8No ratings yet

- LV PPT 1210Document29 pagesLV PPT 1210Chep AmmarNo ratings yet

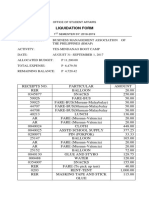

- Liquidation Form: Office of Student AffairsDocument3 pagesLiquidation Form: Office of Student AffairsKent CondinoNo ratings yet

- Definition of TrendsDocument15 pagesDefinition of TrendsHezron DamasoNo ratings yet

- Team Together 2 - WorkbookDocument27 pagesTeam Together 2 - Workbookgabriela ruizNo ratings yet

- thanh thảoDocument10 pagesthanh thảolinhthienan133No ratings yet

- Applications of Embellishment TechniquesDocument4 pagesApplications of Embellishment TechniquesHD MOVIESNo ratings yet

- Lista Arome Dama 124Document1 pageLista Arome Dama 124Lili AnaNo ratings yet

- Dubai Fashion Week 08Document4 pagesDubai Fashion Week 08Shalini Seth50% (2)

- Fashion As Art-Art As FashionDocument2 pagesFashion As Art-Art As Fashionjuvy perezNo ratings yet

- Combined Fashion & Lifestyle ListDocument54 pagesCombined Fashion & Lifestyle Listvivek sharmaNo ratings yet

- Phone: 0878 2334 2266 DateDocument4 pagesPhone: 0878 2334 2266 Dateoman triadiNo ratings yet

- Winter 16: Semi-Jogger Black (VV631)Document2 pagesWinter 16: Semi-Jogger Black (VV631)Khoa NguyenNo ratings yet

- Salwar KameexDocument14 pagesSalwar KameexNaseeb Kaur100% (1)

- Charizma Polly Chiffon Collection Vol-01Document19 pagesCharizma Polly Chiffon Collection Vol-01Snober IqbalNo ratings yet

- Arvind Brands' Competitive Position !!Document38 pagesArvind Brands' Competitive Position !!rjrahul86100% (1)

- Bhartiyam Vidya Niketan Class I Environmental Studies CHAPTER 6 (My Needs: Clothing)Document3 pagesBhartiyam Vidya Niketan Class I Environmental Studies CHAPTER 6 (My Needs: Clothing)ranuNo ratings yet