Professional Documents

Culture Documents

D.C. Bhattacharya and Abdur Rahman Chowdhury, JJ.: Equiv Alent Citation: 27 DLR (1975) 122

Uploaded by

Md Ikra0 ratings0% found this document useful (0 votes)

241 views29 pagesOriginal Title

Mrs_Aruna_Sen_vs_Govt_of_the_Peoples_Republic_of_BBDHC740015COM645258_high

Copyright

© © All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

PDF, TXT or read online from Scribd

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

© All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

Download as PDF, TXT or read online from Scribd

0 ratings0% found this document useful (0 votes)

241 views29 pagesD.C. Bhattacharya and Abdur Rahman Chowdhury, JJ.: Equiv Alent Citation: 27 DLR (1975) 122

Uploaded by

Md IkraCopyright:

© All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

Download as PDF, TXT or read online from Scribd

You are on page 1of 29

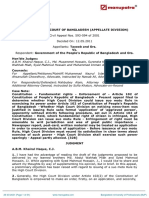

LEX/BDHC/0015/1974

Equivalent Citation: 27 DLR (1975) 122

IN THE SUPREME COURT OF BANGLADESH

(HIGH COURT DIVISION)

Petition No. 407 of 1974

Decided On: 17.09.1974

Appellants: Mrs. Aruna Sen

Vs.

Respondent: Govt. of the People's Republic of Bangladesh through the

Secretary, Ministry of Home Affairs, Dacca, The Director, Rakhi Bahini, Sher-

e-Bangla Nagar, Dacca and The Deputy Commissioner, Dacca and Ors.

Hon'ble Judges:

D.C. Bhattacharya and Abdur Rahman Chowdhury, JJ.

Counsels:

For Appellant/Petitioner/Plaintiff: Moudud Ahmed, Jamiruddin Sircar, Advocates

For Respondents/Defendant: K.Z. Alam, Deputy Attorney-General

JUDGMENT

D.C. Bhattacharya, J.

1. In this petition the validity of the arrest and detention of one Chanchal Sen, who

happens to be the son of the petitioner, has been challenged. According to the case

made out in the petition, in the morning of the 30th March, 1974, the said Chanchal

was attacked by a group of young-men who tried to kidnap him while he was passing

along Sat Masjid Road. Some of the Student and teachers of the Graphic Art College

which is close to the place of occurrence having intervened the said group did not

succeed in their attempt and left the place. But shortly thereafter some members of

the Rakkhi Bahini appeared on the scene and took away the said Chanchal Sen. The

petitioner having failed to trace the whereabouts of her son after making all enquiries

from the local police and also from the authority of the Dacca Central Jail issued a

statement in the Newspapers on the first April, 1974. On the 2nd April, the

petitioner's lawyers served a notice upon the respondents 1, 2 and 3 asking for

information as to the charges against him, the place of his custody and the authority

under which he was being held. On the 3rd April a friend of the petitioner having

rung up the Director of the Rakkhi Bahini was informed by the said officer that

Chanchal was still in custody and there was nothing to worry about it. On the 5th

April, the petitioner's lawyers received a letter from the Deputy Director

(Administration), Jatiya Rakkhi Bahini stating that Chanchal Sen had been handed

over to the Special Branch Police on the 30th March, 1974. Thereafter the petitioner

having learnt on the 6th April, 1974 that her son had been in custody at

Mohammadpur police-station, saw him there and found him in miserable condition.

He complained of physical tortures also. Thereafter on the 8th April the petition under

Article 102 of the Constitution was moved in this Court on which the present Rule

was issued. An affidavit-in-opposition has been sworn by a Section Officer of the

Ministry of Home Affairs on the 17th of May, 1974 in which it has been stated that

11-04-2021 (Page 1 of 29) www.manupatra.com Bangladesh University of Professionals (BUP)

Chanchal Was arrested in the evening of the 30th March, 1974 from Mohammadpur

and was handed over to Mohammadpur Police Station soon thereafter, that he was

produced before the Sub-Divisional Magistrate (Sadar), Dacca on the 31st March,

1974, who remanded him to police custody for seven days and that he was initially

arrested under section 54 of the Code of Criminal Procedure, but has subsequently

been detained under section 3(1)(a) of the Special Powers Act, 1974 on the basis of

the order by the Government dated the 9th April; 1974. It has been further asserted

that the detenu is an active worker of a secret subversive organization and was

carrying on the activities of the said organization regaining underground; that he and

the said organization are involved in committing murders, armed robberies, etc. with

unauthorized arms and that in February, 1974 the Rakkhi Bahini recovered a huge

quantity of arms and amunitions from his house and nearby places and also certain

prejudicial documents, booklets and leaflets from his house in course of the search.

It has been further alleged in the said affidavit that the detenu is also wanted as an

accused in Bhederganj P.S. Case No. 8 dated 15-7-72 under section 364, 307 and 34

of Bangladesh Penal Code and also Bhederganj P.S. Case No. 1 dated 9-1-74 under

section 302 of the Bangladesh Penal Code.

2 . An affidavit-in-reply has been filed contesting the statements made in the

affidavit-in-opposition. It has been asserted in the said affidavit that the order of

detention under the Special Powers Act is an afterthought and an abuse of the

executive authority and that the allegation as to the recovery of arms and

ammunitions as well as certain prejudicial papers from the, house of the detenu and

also the allegation relating to the commission of murders, armed robberies etc. are

false. The statements as to two Bhederganj P.S. cases also have been denied.

3 . This matter came up for hearing on the 17th June, 1974, but no materials were

placed before this Court by the respondents for determining whether there was

reasonable basis for the satisfaction of the detaining authority as required under the

law. No copy of the grounds of detention was produced in Court nor it was averred in

the affidavit filed on behalf of the respondents that such grounds were served upon

the detenu within the time as directed in the Constitution. It being pointed out that it

was the duty of the detaining authority to satisfy the Court that all constitutional

requirements had been complied with and that there were no materials from which a

reasonable man may be satisfied as to the necessity of the impugned detention, the

learned Deputy Attorney General prayed for time for filing a supplementary affidavit

containing the required particulars and the said prayer was granted.

4 . A supplementary affidavit-in-opposition has been sworn by another Section

Officer, to which a copy of the grounds learning the date of 9-4-74, a copy of the

order sheet of the Court of S.D.O. (S) Dacca and also a copy of a document said to-

be a police message dated 16-4-74 showing that a charge-sheet had been filed in one

of the two police cases against the detenu as an accused and that the detenu was

wanted in the other case also, have been annexed.

5. A supplementary affidavit-in-reply has been sworn by the petitioner contesting the

validity of the arrest of the detenu under section 54 of the Code of Criminal Procedure

and remand under section 167 of the Code of Criminal Procedure and denying the

connection of the detenu with the Bhederganj P.S. Cases. It has been further asserted

that the allegation contained in the grounds of detention are false, concocted and

baseless.

6 . While hearing this matter, it has struck us that there has not been adequate

11-04-2021 (Page 2 of 29) www.manupatra.com Bangladesh University of Professionals (BUP)

appreciation on behalf of the respondents as to the duty and responsibilities in regard

to the return to be made to a Rule, issued by the Court under Article 102(2)(b) of the

Constitution. The English principle as expressed by Lord Atkin in his dissenting

speech in Diversidge Vs. Anderson that every imprisonment without trial and

conviction is prima facie unlawful and the onus is upon the detaining authority to

justify the detention by establishing the legality of its action according to the

principles of English law has been adopted in the legal system of this Subcontinent,

as has been rightly observed by Hamoodur Rahman, J., (as he then was) in the

Government of West Pakistan and another Vs. Begum Agha Abdul Karim Shorish

Kashmiri 21 D.L.R. (S.C.) 1-P.L.D. 1969 (S.C.) 14. The Constitution having

highlighted the rule of law and the fundamental human rights and freedom in the

preamble of the Constitution, and personal liberty being the subject of more than one

fundamental being the subject of more than one fundamental rights as guaranteed

under)the Constitution, a heavy onus is cast by the Constitution itself upon the

authority, seeking to take away the said liberty on the avowed basis of legal sanction,

to justify such action strictly according to law and the Constitution. In such a case

where detention of a citizen has been challenged as violative of his fundamental right

as guaranteed under the Constitution, the foremost duty of the detaining authority is

to establish that the constitutional requirements as provided in clauses (4) and (5) of

Article 33 of the Constitution have been strictly complied with and that there are

materials as the basis of the satisfaction of a reasonable man as to the necessity of

the detention for the purpose of preventing the detenu from committing a prejudicial

act. The onus is completely on the authority who has deprived a citizen of his

personal liberty by detaining him in custody for satisfying the court that the detenu is

being held not only with the lawful authority, but also in lawful- manner,

7 . In the present case the authority concerned having claimed to detain the detenu

under section 3 of the Special Powers Act, it is to be shows that the action is justified

according to the said provision which is to the following effect

3 (1) The Government may; if satisfied with respect to any person that with a

view to preventing him from doing any prejudicial act it is necessary so to

do, make the order-

(a) directing that such person be detained...

****

8. Having regard to the constitutional jurisdiction exercisable by this Court, it is now

well-established that the satisfaction of the Government as has been referred to in

the aforesaid provision is amenable to objective test and is justiciable. The learned

Deputy Attorney General has tried to submit that the satisfaction of a person being a

subjective concept and no mention of reasonableness being made in the statute itself,

it does not appear to be the legislative intent that the satisfaction of the detaining

authority should be the subject of judicial review and has referred to a decision from

the Indian Jurisdiction in the case of Pushkar Mukharjee Vs. The State of West

Bengal, A.I.R. 1970 (S.C.) 852 in support of his contention.

The competition for judicial recognition between these two contending concepts us to

subjective and objective tests for proving satisfaction of the authority concerned has

got a chequered history.

9 . In Shearer Vs. Shields, 1914 A.C. 808, the House of Lords had to construe a

provision, in the Glasgow Police Act authorising constables to arrest if they had

11-04-2021 (Page 3 of 29) www.manupatra.com Bangladesh University of Professionals (BUP)

'reasonable grounds of suspicion' and the House held that the burden vested upon the

constable concerned to show that the suspicion was reasonable.. In Liversidge, Vs.

Anderson, 1942 A.C. 206, the House of Lords had to construe a provision of a

Regulation made under the Emergency Power (Defence) Act, 1939, authorising

detention of a person if the Secretary of State had 'reasonable cause to believe that

he comes within the category mentioned in the regulation and the majority of the

House, with the exception of Lord Atkin, held that the subjective satisfaction of the

Secretary of State was enough.

10. The earliest case in the Indian subcontinent which had to consider the, Liversidge

case is the case of Keshab Talpade Vs. Emperor, A.I.R. 1943 F.C.l where the Federal

Court of India was called upon to consider the legality of the detention of the

appellant under the Defense of India Rules made under the Defense of Indian Act,

1939, which were similar to the Regulation and the Emergency Powers (Defense) Act,

1939 under which the said Regulation was made on an application under section 491

of the Code of Criminal Procedure. There were two rules in Defense of India Rules

viz. Rule 26 and Rule 129, under which, an order of detention or arrest could he

made. Under Rule 26, the Central Government or Provincial Government could make

an order of detention of a person if it 'was satisfied' that with a view to prevent him

from acting in any manner prejudicial to the defense of India Act, it was necessary so

to do. Under Rule 129, a police officer could arrest a person whom he reasonably

suspected of having acted or acting or being about to act in a particular manner.

Chief Justice Goayer, who delivered the judgment of the Court, though posed the

question whether the satisfaction of the detaining authority as referred to in the rule-

making power contained in section 2 of the Defense of India Act should be subjective

or objective did not answer it was Rule 26 under which the impugned order of

detention was made was itself struck down on the ground that it did not provide for

reasonable satisfaction notwithstanding the fact that section 2(2) under which the

said rule was made itself provided for reasonable satisfaction.

11. The decision of Keshav Talpade was however overrulled in the case of Emperor

Vs. Shib Nath Banerjee, AIR 1945 (PC) 156 where Lord Thankerton L.C. held that the

Rule making power being conferred both under subsection (1) and (2) of section 2 of

the Defense of India Act, one being general and the other particular, and the

limitation of reasonable satisfaction being not incorporated in the general powers

under sub-section (1) of section 2, Rule 26 could be regarded to be validly framed

under sub-section (1), rather than under sub-section (2), The detention of all the

detenue dealt in that case being under Rule 26 of Defense of India Rules, which

provided for more satisfaction of the Provincial Government one of the questions

raised was whether there had been necessary satisfaction of the appropriate authority

in respect of the order of detention and the Judicial Committee was of the opinion

that in view of section, 16(2) of the Defense of India Act which provided for

presumption as to authenticity, the orders of detention in each of those cases must

be taken ex facie regular and proper and that there was a heavy burden on the

respondents to displace the said presumption. The impugned orders showed that they

were by orders of the Governor, but signed by the Additional Secretary or Additional

Deputy Secretary to the Government of Bengal. The affidavits on behalf of the

respondents were sworn by Mr. Porter Additional Home Secretary to the Government

of Bengal who signed the order in most cases and these affidavits showed that in

certain cases, he passed merely a routine order in accordance with the

recommendation of the police and in certain other cases applied his mind to the facts

of the case before signing the order. According to the Judicial Committee, routine

orders which showed that there was no application of the mind for the formation of

11-04-2021 (Page 4 of 29) www.manupatra.com Bangladesh University of Professionals (BUP)

the opinion of the signing officer were declared to be invalid, but the orders which

were averred by the signing officer to have been made after consideration of the

relevant materials or in respect of which there was no contrary evidence, were held to

be valid.

12. The case of Liversidge Vs. Anderson was distinguished in the case of Emperor

Vs. Vimlabai Deshpand, ( : MANU/PR/0009/1946 : A.I.R. 1946 P.C. 123) on the

ground that the authority was a high officer of the State and there was obvious

inconvenience and danger to the public in case of disclosure of confidential

information. In Vimlabai Deshpande's case a distinction, was made between rule 26

and rule 129. AS has been pointed out above, under rule 26 an order of detention

could be made if the Government was satisfied as to the necessity of making such an

order and under rule 129(1) any police officer might arrest any person whom be

reasonably suspected of having acted in a manner prejudicial to the public safety or

the efficient prosecution of the war. According to the Privy Council in the case of an

arrest under rule 129(1) the burden lay upon the police officer to satisfy the court

that his suspicion was reasonable.

13. The Judicial Committee of the Privy Council had to consider the true meaning of

the expression "reasonable grounds to believe" in an appeal from Ceylon in the case

Nakhuda Ali Vs. M. F. De S. Jayaratne, (1951) A.C. 66 and the Judicial Committee

differed from the majority view in Liversidge Vs. Anderson, in regard to the

construction of such an expression and Lord Badcliffe in delivering the judgment of

the Privy Council made the following observation:

Their Lordships do not adopt a similar construction of the words in reg. 62

which are now before them. Indeed, it would be a very unfortunate thing if

the decision of Liversidge case came to be regarded as laying down any

general rule as to the construction of such phrases when they appear in

statutory enactments. It is an authority for the proposition that the words "if

A, B. has reasonable cause to believe" are capable of meaning "if A. B.

honestly thinks that he has reasonable cause to believe" and that in the

context and attendant circumstances of Defense Regulation 18B they did in

fact mean just that. But the elaborate consideration which the majority of the

House gave to the context and circumstances before adopting that

construction itself shows that there is no general principle that such wore are

to be so understood; and the dissenting speech of Lord Atkin at least serves

as a reminder of the many occasions when they have been treated as

meaning "if there is in fact reasonable cause for A.B. so to believe". After all,

words such as these are commonly found when a legislature or law-making

authority confers powers on a minister or official. However read, they must

be intended to serve in some sense as a condition limiting the exercise of an

otherwise arbitrary power. But if the question whether the condition has been

satisfied is to be conclusively decided by the man who wields the power, the

value of the intended restraint is in effect nothing. No doubt he must not

exercise the power in bad faith; but the field in which this kind of question

arises is such that the reservation for the case of bad faith is hardly more

than a formality. Their Lordships therefore treat the words in reg. 62, "where

the Controller has reasonable grounds to believe that any dealer is unfit to be

allowed to continue as a dealer" as imposing a- condition that there must in

fact exist such reasonable grounds, known to the Controller before he can

validly exercise the power of cancellation.

11-04-2021 (Page 5 of 29) www.manupatra.com Bangladesh University of Professionals (BUP)

14. The Judicial Committee however took the view in the said case relying upon the

view of Lord Atkin, L.J. in Rex Vs. Electricity Commission (1924) 1 K.B. 171 and Lord

Hewart, C.J. in Rex Vs. Legislative Committee of the Church Assembly (1928) 1 K.B.

411, that to enable a superior Court in intervene by a writ of certiorari it was not

enough that a body of persons should be charged with a legal authority to determine

questions affecting the rights of the people, but there must be superadded to that

characteristic the further characteristic that the body had also the duty to act

judicially.

1 5 . Whatever departure was made in the Nakkuda Ali's case from the theory of

subjective satisfaction as formulated in Liversidge Vs. Anderson, was nullified to a

certain extent by the further formulation of an additional condition that the statute in

question must require the relevant body to act judicially.

In the case of Messrs Faridson Ltd. and another Vs. Government of Pakistan and

others, 13 DLR (SC) 233-PLD 1961 (SC) 537 S.A. Rahman, J. (as he then was)

noticed, in course of his separate judgment, that in Nakkuda Ali's case and the earlier

case of Franklin Vs. Minister of Town and Country Planning (1948) A.C. 87 decided

by the House of Lords, the judicial pendulun swung to the other extreme and that

they ran counter to a long line of decisions in the English Courts extending back for

more than a century, in which the requirement of an impartial fact-finding and good

faith had been insisted upon the administrative bodies in regard to their

administrative decisions affecting individual's rights and liberties.

16. The House of Lords was confronted with the question as to correctness of the

decision in Nakkuda Ali's case in Hidge Vs. Baldwin and others (1964) A.C. 40. After

quoting the oft quoted passage from the judgment of Lord Atkin, L.J. in Rex Vs.

Electricity Commissioners and also the observation of Lord Hewart C.J. in Rex Vs.

Legislative Committee of Church Assembly, Lord Reid (with whom all the Law Lords

excepting Lord Evershed agreed) observed that the matter had been complicated by

what he believed to be a misunderstanding of the said passage of Lord Atkin and that

a gloss had been put on the same by Lord Hewart C.J. The opinion of Lord Reid in

this regard was expressed in his speech in the followings manner :

I have quoted the whole of this passage by cause it is typical of what has

been said on several subsequent cases. Lord Hewart meant that it is never

enough that a body simply has duty to determine what the rights of an

individual should be, but that there must always be something more to

impose on it a duty to act judicially before it can be found to observe the

principles of natural justice, then that appears to me impossible to reconcile

with the earlier authorities. I could not reconcile it with what Lord Denman

C.J. said in Reg. Vs. Smith, 5 Q.B. 615, or what Lord Campbeel, C.J. said in

Ex parte Ramshay, 18 Q.B. 173, or what Lord Hatharlev D.C. said in Osgood

Vs. Nelson, L.R. 5 H.L. 636, or that was decided in Cooper Vs. Wandsworth

Board of Works, 14 C.B.N.S. 180 or Hopkins Vs. Smethwick Local Board, 24

Q.B.D. 712, or what Lord Parmoor said in De Verteuil V. Knaggs, (1918) A.C.

557, or what Kelly C.B. said with the subsequent approval of Lord

Macnaughten, in Wood V. Woad, L.R. 9 Ex. 190, or what Jessel M.R. said in

Fisher V. Keane, 11 Ch. D. 353, or what Lord Birkenhead L.C. Said in

Weinberger V. Inglis, (1919) A.C; 606, and that is only a selection of the

earlier authorities. And, as I shall try to show, it cannot be what Atkin L.J.

'meant. In Rex V. Electricity Commissioners, Ex parte London Electricity Joint

Committee Co., the Commissioners had a statutory duty to make schemes

11-04-2021 (Page 6 of 29) www.manupatra.com Bangladesh University of Professionals (BUP)

with regard to electricity districts and to hold local inquiries before making

them. They made a draft scheme which in effect allocated duties too one

body which the Act required should be allocated to a different kind of body.

This was held to be ultra vires, and the question was whether prohibition

would lie. It was argued that the proceedings of the Commissioners were

purely executive and controllable by Parliament alone. Bankes L.J. said : "On

principle and on authority it is in my opinion open to this court to hold, and I

consider that it should hold, that powers so far reaching, affecting as they do

individuals as well as property, are powers to be exercised judicially, and not

ministerially or merely, to use the language of Palles C.B., as proceedings

towards legislation" So he inferred the judicial element from the nature of

the power. And I think that Atkin L.J. did the same. Immediately after the

passage which I said has been misunderstood, he cited a variety of cases and

in most of them I can see nothing "superadded" (to use Lord hew-art's word)

to the duty itself.

17. An analysis of these cases will show that the dictum of subjective satisfaction as

laid down in the majority decision in Liversidge V. Anderson has been whittled down

to a large extent by confining its application to exceptional condition prevailing

during war time. The later cases have sought to invest an administrative action with

an attribute which renders such action amenable to judicial scrutiny not so much,

upon the language used in authorizing such action as upon the nature of the authority

created thereby. If the authority purports to interfere with the rights or liberties of the

citizens such authority has he concomitant duty of discharging its function judicially.

That is to say, it shall give opportunity to the affected person of being heard and also

it shall have to arrive at its decision after consideration of the relevant materials.

Some limitation may of course be imposed in respect of affording this opportunity of

being heard by a positive provision in the statute, but having regard to the nature of

the power weilded by the authority in the exercise of which individual rights and

liberties may be affected, the satisfaction which is enjoined by the statute as a

condition precedent to the exercise of such power must necessarily be judicially

arrived at and as such, be objective in its content.

18. The Supreme Court of Pakistan had to examine this question of subjective or

objective satisfaction, in construing the provisions of Public Safety Ordinance, 1958

authorizing a police officer to "arrest any person whom he reasonably suspects of

having done or doing or about to do a prejudicial act" in the light of the dictum of

Liversidge V. Anderson in the case of Government of East Pakistan V. Mrs. Roushan

Bejoya Shankat Ali Khan, 18 DLR (SC) 214. Section41 (1) of the East Pakistan Public

Safety Ordinance was analogous to rule 129 of the Defense of India Rules which was

examined by the Judicial Committee of the Privy Council in the case of Emperor V.

Vimlabai Deshpande, AIR. 1946'PC 123 and S. A. Rahman, J (as he then was) in

delivering the judgment of the majority in Shaukat Ali's case followed the said

decision of the Judicial Committee and observed as follows :

The words that fell to be construed in Liversidge V. Anderson were

"reasonably satisfied" and they were held to signify, only the personal

satisfaction of the Home Secretary. It may be added that the construction in

question was adopted in connection with a war-time measure. We are here

dealing with peace time legislation and though questions of security of the

State or public order may involve at times, considerations of a confidential

character and of the greatest urgency, yet it; would be difficult to uphold a

construction which jeopardizes the precious right of personal liberty of a

11-04-2021 (Page 7 of 29) www.manupatra.com Bangladesh University of Professionals (BUP)

citizen, during peace time, on the mere ipse dixit of a police offices. I am

therefore in agreement with the High Court in holding that in the present

case it lay on the arresting officer to justify the arrest by revealing

reasonable grounds such as could satisfy the judicial conscience.

19. The Supreme Court of Pakistan had to examine several orders of detention made

under rule 32 of the Defense of Pakistan Rules, 1965 which empowered the Central

Government to make an order of detention if it was 'satisfied with respect to certain

matters (and it was analogous to rule 26 of the Defense of India Rules, 1939) in the

case of Gholam Jilani Vs. Government of West Pakistan, 19 DLR (SC) 403. There, was

no mention of "reasonable" in regard to satisfaction required under the said rule.

Cornelius, C.J. who delivered the judgment of the Bench shed new light on the

construction of relevant provisions of detention laws by relating the administrative

actions as to preventive detention to the constitutional powers of the superior courts:

In pre-independence India such matters came under the jurisdiction, of the Court as

exercisable under section 491 of the, Code of Criminal Procedure, as writ jurisdictions

which are now exercised by such courts in the Indian subcontinent were not available

to them. Although in England these matters came within the jurisdiction of

prerogative writs, the constitutional jurisdiction which was conferred upon the

superior courts in Pakistan under 1962 Constitution as incorporated in Article 98 of

the Constitution was of wider scope. This is how Chief Justice Cornelius, interpreted

rule 32 of the Defense of Pakistan Rules :

Under the Constitution of Pakistan a wholly different state of affairs prevails.

Power is expressly given by Article 98 to the Superior Courts to probe into

the exercise of public power by executive authorities, how high soever, to

determine whether they have acted with lawful-Authority. The judicial power

is reduced to a nullity if laws art so worded interpreted that the executive,

authorities may make what statutory rules they please thereunder, and may

use this freedom to make themselves the final judges of their won

"satisfaction" for imposing restraints on the enjoyment of the fundamental

rights of citizens. Article 2 of the Constitution could be deprived of all its

content through this process, and the courts would cease to be guardians of

the nations liberties. It is therefore impossible to construe the relevant

provisions in the defense of Pakistan. Ordinance in the manner adopted by

the Judicial Committee in the case of Shibnath Banerjee for interpreting the

somewhat similar provisions in the Defense of India Act and Rules. Clause

(x) of sub-section (2) of section 3 must be construed as providing the

specific guidelines which control any rules as to apprehension and detention

that are to be made under the power given by sub-section (1) of section 3

On that view, it is clear that "Satisfaction" of the detaining authority acting

under rule 32 must be a state of mind, which has been induced by the

existence of Reasonable grounds for such satisfaction. The power of an

authority acting under rule 32 is therefore no more immune to judicial review

than is the power of a police officer acting under rule 204. With reference to

rule 129 of the Defense of India Rules (corresponding to our rule 204) the

Judicial Committee felt no hesitation in finding that there was an onus upon a

police officer to satisfy the Court that he had reasonable ground's for his

suspicion. Suspicion would include belief or knowledge, whether inferential

or actual. On the same reasoning, it must follow that options by other and

perhaps higher authorities, under rule 32, like all other actions relatable to

the power delineated in clause (x) aforesaid, are equally susceptible of

judicial review, subject, or course to the right of the State to claim privilege

11-04-2021 (Page 8 of 29) www.manupatra.com Bangladesh University of Professionals (BUP)

in respect of secret information, and the Court's power to hold proceeding in

camera.

20. It should, however, be noticed that the Chief Justice Cornelius drew support to a

certain extent for his view as to the court's power of judicial review of Government

actions regarding preventive detention, from the mention of the word 'reasonable' in

clause (x) of sub-section (2) of section 3 of the Defence of Pakistan Ordinance, 1965,

although the Judicial Committee of the Privy Council in Shibnath Banerjee's case

held, in over-ruling the decision of the Federal Court of India in Kesbav Talpada's

case, that rule 26 of Defense of India Rules (which was analogous to rule 29 of the

Defense of Pakistan Rules) could very well be regarded as framed under sub-section

(1) of section 2 of Defense of India Act, 1939 (analogous to section 3 (1) of Defense

of Pakistan Ordinance, 1965) which bad no reference to reasonable grounds.

21. To obviate the effect of the judgment in Gholam Jilani's case, the Defense of

Pakistan Ordinance, 1965 was amended by the President of Pakistan by Ordinance No.

II of 1968 on the 4th March, 1968 by substituting new clauses in sec. 3 (2) of the

Ordinance, the effect of which was that it was no longer necessary for the authority

concerned to be "satisfied" as to the necessity of detention but it would be sufficient

if he was "of the opinion" that it was necessary to do, so. Furthermore, an

explanation was added to the effect that "for the avoidance of doubt it is hereby

declared that the sufficiency of the grounds on which such opinion as aforesaid is

based shall be determined by the authority forming such opinion"

22. The question as to the effect of this amendment was raised in the next case

decided by the Supreme Court of Pakistan, viz., Mir Abdul Baqi Baluch Vs.

Government of Pakistan, 20 DLR (SC) 249= PLD 1968 (SC)313. But no decision was

given on this question as the orders of the detention under rule 32 of the Defense of

Pakistan Rules impugned in the said case were; made long before the enacting of the

said amendment, but the nature and scope of judicial review of such orders was

however, further elucidated in the said case, as will be found in the following

observation of Hamoodur Rahman, J. (as he then was) who delivered the judgment of

the Bench :

However, as I have said earlier, my reading of the majority decision in

Ghulam Jilani's case, to which lama party, it that it alters the law laid down

in Liversidge's case only to the extent that it is no longer regarded as

sufficient for the executive authority, merely to produce its order, saying that

it is satisfied; It must also place before a court the material upon which it so

claims to have been satisfied so that the Court can, in discharge of its duty

under Article 98(2)(b)(i) be in turn satisfied that the detenu is not being held

without lawful authority or in an unlawful manner. The wording of clause (b)

(i) of Article 98(2) shows that not only the jurisdiction but also the manner

of the exercise of that jurisdiction is subject to judicial review. If this

function is to be discharged in a judicial manner then it is necessary that the

court should have before it the materials upon which the authorities have

purported to act. If any such material is of a nature for which privilege can

be claimed, then that too would be a matter for the Court to decide as to

whether the document concerned is really so privileged. In exercising this

power the High Court does not sit as an appellate authority nor does it

substitute its own Opinion for the opinion of the authority concerned.

23. It will also be useful to quote the following observation of the learned Judge in

11-04-2021 (Page 9 of 29) www.manupatra.com Bangladesh University of Professionals (BUP)

another part of the judgment :

Under a Constitutional system which provides for a judicial review of

executive action, it is, in my opinion a fallacy to think that such a judicial

review must be in the nature of an appeal against the decision of the

executive authority. It is not the purpose of a judicial authority reviewing

executive actions to sit on appeal over the executive of to substitute the

discretion of the Court for that of the administrative agency. What the court

is concerned with is to see that the executive or administrative authority had

before it sufficient materials upon which a reasonable person could have

come to the conclusion that the requirements of law were satisfied. It is not

uncommon that even high executive authorities act upon the basis of

information supplied to, them by their subordinates. In the circumstances, it

cannot be said that it would, be unreasonable for the court, in the proper

exercise of its constitutional duty, to insist upon a disclosure of the materials

upon which the authority bad acted so that it should satisfy itself that the

authority had not acted in an "unlawful manner.

24. The constitutional power enjoyed by a High Court under Article 98 of the Pakistan

Constitution of 1962 was further, more throughly examined, in the case of

Government of West Pakistan Vs. Begum Agha Adbul Karim Sherish Kashmiri, 21 DLR

(SC) 1. and it was noticed therein that Article 98 (which is the same as Article, 102 of

our Constitution) was different from Article 170 of the Pakistan Constitution of 1956

or Article 226 of the Indian Constitution, Hamoodur Rahman, J. (as he then was) in

delivering the judgment of the Court in this case also observed as follows :

In my view the words "in an unlawful manner" in sub-clause (b) of Article 98

(2) have been used deliberately to give meaning and content to the solemn

declaration under Article 2 of the Constitution itself that it is the inalienable

right of every citizen to be treated in accordance with law and only in

accordance With law. To my mind, therefore, in determining as to how and in

what circumstances a detention would be detention in an unlawful manner

one would invitably have first to see whether the action is in accordance with

law, if not, then it is action in an unlawful manner. Law is here not confined

to statute law alone but is used in its generic sense as connoting all that is

treated as law in this country including even the judicial principles laid down

from time to time by the Superior Courts. It means according to the accepted

forms of legal process and postulate a strict performance of all the functions

and duties laid down by law. It may well be, as has been suggested in some

quarters, that in this sense it is as comprehensive as the American "due

process" clause in a new grab. It is in this sense that an action which is

malafide or colorable is not regarded as action in accordance with law

Similarly, action taken upon extraneous or irrelevant considerations is also

not action in accordance with law. Action taken upon no ground at all or

without proper application of the mind of the detaining authority would also

not qualify as action in accordance with law and would, therefore, have to be

struck down as being action taken in an unlawful manner, It would seem,

therefore, that by these words at any rate, so far as the deprivation of the

liberty of a citizen was concerned, the Constitution makers intended that this

most cheristed right should not be taken away in an arbitrary manner and

hence by sub-clause (b) of clause (2) of Article 98 they advisedly left it to

the High Courts to review the actions of the detaining authority, untramelled

by the formalities or technicalities of either sectional of the Criminal

11-04-2021 (Page 10 of 29) www.manupatra.com Bangladesh University of Professionals (BUP)

Procedure Code or the old prerogative writ, of habeas corpus, not only with

regard to the- vires of the law or the officer concerned but also enjoined

upon them to satisfy themselves that the detection is not in any manner

contrary to law. The Scope of the enquiry is, therefore, not in any way

fettered by procedure of a writ of habeas corpus Acts. The Court must,

neverthless, in deciding this question necessarily have regard to the language

of the statute under which the power is exercised, the purpose for which the;

detention is sought to be made and the circumstances in which it came to be

ordered The content of the power vested by the Constitution in the High

Court cannot be limited or taken away by a sub-Constitutional legislation but

the reference to the statute and the other factors mentioned above is rather

for determining its true nature, scope and legality.

25. With regard to the amendment introduced by Ordinance No. II of 1968 it was

held in the said judgment to be an exercise in futility and the view of the said court

has been, further expressed in the following observation:

The splitting up of the provision has in no way affected the reasons given by

this court in Ghulam Jialni's case. If it is an incident of the power of judicial

review granted to this Court by Article 98 of the Constitution. Then the

question as to whether there are grounds upon which a, reasonable person

would have formed the same opinion is certainly within the ambit of the

power of judicial review, no matter what the language used in the sub-

Constitutional legislation.

26. We shall have to refer to one observation of Mr. Justice Hamoodur Rahman (as

he then was) made in the case of Baqui Baluch, before we part with the discussion of

this series of decisions of the Supreme Court of Pakistan which made an important

contribution to the evolution of the precedent law and in which the constitutional

powers of the Pakistan High Court s in regard to the judicial review had been so

clearly expounded.

27. In repelling: an argument made at the bar relying upon the decision in Faridson's

case as to the necessity of service of a show cause notice before an order of

detention had been made, the learned Judge made the following observations :

Another point that remains to be dealt with is as to whether a show cause

notice ought to have been given to the appellant before making the

Impugned order. For this purpose reliance is placed upon the decision of this

Court in the case of Messrs. Faridsons Limited Vs. The Government of

Pakistan. But it has to be pointed out that the principles laid down in that

case are not attracted in the case of a preventive detention for, such orders

are made purely on considerations of policy or expedience. There can be no

question of the detaining authority being Under any obligation to act

judicially or even quasi-judicially. It is only where there is a duty to decide

judicially of quasi-judicially that the principles of natural justice referred to

in: Faridsons case are attracted.

2 8 . With great respect, we may say that the law laid down in English judicial

decisions of unquestioned-authority, to which reference has already been made, is

that in all cases in which a person is invested with the legal authority to take decision

affecting individual rights or liberties of the citizen, he is required to act judicially

and observe the principles of natural justice. It does not seem to be in consonance

11-04-2021 (Page 11 of 29) www.manupatra.com Bangladesh University of Professionals (BUP)

with justice or equity nor does there appear to be any valid reason for departing from

the said rule in case of a person who is completely deprived of his liberty altogether,

unless there is a positive provisions to the said effect in the statute providing for

such preventive detention. If on an interpretation of the statutory provision it is found

that prior serving of show cause notice is not contemplated, in that case there cannot

be any instance on a show cause notice, but even then, the obligation of the

detaining authority to act judicially informing its opinion in favor of deprivation of the

liberty of a citizen, cannot be deemed to have been done away with.

29. Homoodur Rahman, J. himself has accepted this position to be correct in the

subsequent case of Begum Shorish Kashmiri when he was analysing the nature and

extent of the power and duty of the detaining authority acting under the Defence of

Pakistan Ordinance and the Rules framed thereunder in the following words:

In this connection I would also like to point out that it is a misconception to

think that either under the Defense of Pakistan Ordinance or the Rules framed

thereunder any arbitrary, unguided, uncontrolled or naked power has been

given to any authority. My approach to these provisions is that they only

confer a power which is coupled with a duty. The power can only be

exercised after the duty has been discharged in accordance with the

guidelines provided in the statute and the rules. Thus under clause (x) of

sub-section (2) of section 3 of the Ordinance and rule 32 of the Rules, the

duty cast upon the authority empowered to detain is to apply its mind to the

particular matters mentioned therein, namely, as to whether the action of the

person sought to be detained was in any manner prejudicial to Pakistan's

relations with foreign powers or to the security, the public safety or interest,

the defense of Pakistan or any part thereof, the maintenance of supplies and

services essential to the life of the community, the maintenance of peaceful

conditions, in any part of Pakistan or the efficient conduct of military

operations for the prosecution of war and then to form an opinion as to the

necessity of the detention. Until such opinion is formed by the honest

application of the mind of the detaining authority the jurisdiction to j make

the order of detention cannot arise.

30. It should be noticed that this view as to the extent of the power of the detaining

authority has been expressed after the word "reasonable" has been deleted from the

relevant provision of the Defense of Pakistan Ordinance and the Rules framed

thereunder.

It has been contended by the learned Deputy Attorney-General that the provisions of

the Special Powers Act have been so worded as to clearly indicate that the subjective

satisfaction of the appropriate Government functionary is sufficient for taken action

under the said Act, and relying upon a decision of the Supreme Court of India in the

case, of Pushkar Mukharjee Vs. The State of West Bengal, AIR 1970 (SC) 852, he has

submitted that the rule of objective test as laid down by the. Supreme: Court of

Pakistan for judicial review of the satisfaction of the detaining authority may be

reviewed.

3 1 . In Pushkar Mukharjee's case the Supreme Court of India was examining the

question of the validity of certain orders of detention made by the Government of

West Bengal under Preventive Detention Act, 1950, the provisions of which are

similar to those of Bangladesh Special Powers Act, 1974, so far as the provisions

relating to the preventive detention are concerned, Under section 3(1) of the Indian

11-04-2021 (Page 12 of 29) www.manupatra.com Bangladesh University of Professionals (BUP)

Act, the Central Government or the State Government may, if satisfied with respect to

any persons that with a view to preventing him from acting in any manner prejudicial

to certain matters, it is necessary so to do, make an order directing that such persons

be detained. With regard, to the question of satisfaction as referred to in the

aforesaid provision, the Supreme Court of India expressed itself in the following

manner

It is well-settled that the satisfaction of the detaining authority to which

section 3 (1) (a) refers is a subjective satisfaction, and so is not justiciable.

Therefore, it would not be open to the detenu to ask the court to consider the

question as to whether the said satisfaction of the detaining authority can be

justified by the application of objective tests. It would not be open, for

instance, to the detenu to contend that the grounds supplied to him do not

necessarily or reasonably lead to the conclusion that if he is not detained he

would indulge in prejudicial activities. The reasonableness of the satisfaction

of the detaining authority cannot be questioned in a court of law; the

adequacy of the material on which the said satisfaction purports to rest also

cannot be examined in a court of law. That is the effect of the true legal

position in regard to the satisfaction contemplated by section 3(1)(a) of the

Act-See the decision of this court in the State of Bombay V. Atmaram

Shridhar Vaidya, AIR 1951 (SC) 157.

32. It is necessary to critically examine this view of the Indian Supreme Court, in

order to see if there is any wide divergence between this view and that of the

Pakistan Supreme Court which is being followed in this Court. It is, of course, to be

remembered that the Contention as to the subjective test was urged before the

Supreme Court of Pakistan in the case of Begum Shorish Kashmiri, on the basis of

certain Indian decisions and Hamoodur Rahman, J. (as he then was) repelled the;

said contention by pointing out that the constitutional provisions as to judicial

review; as incorporated in Article 98 of the Pakistan Constitution of 1962 which is

exactly the same as Article 102 of the Bangladesh Constitution gave much wider

power to the High Court than the corresponding provision of the Indian Constitution

or the Pakistan Constitution of 1956. It is according to the Supreme Court of Pakistan

certainly an important element of difference having a bearing upon the constitutional

powers of a High Court operating under the Pakistan Constitution, 1962. It should

not, however, be overlooked that notwithstanding the adopting of the rule as to

subjective satisfaction by the Supreme Court of India the powers of Judicial review

exercised by the Supreme Court in India are sufficiently wide, particularly in a case

where the question of mala fide is raised.

33. For a correct appraisal of this question it is necessary to refer to the decision of

the Supreme Court of. India in the case of the State of Bombay Vs. Atmaram Shridhar

Vaidya, AIR 1951 (SC) 157, on which reliance was placed in Pushkar Mukharjee's

case, Chief Justice Kania who delivered the leading judgment in the case, interpreted

the provisions of the Preventive Detention Act as to the satisfaction of the detaining

authority in the following terms:

The wording of the section thus clearly shows that it is the satisfaction of the

Central Government or the State Government on the point which alone is

necessary to be established. It is significant that while the objects intended

to be defeated are mentioned, the different methods, acts or omission by

which that can be done are not mentioned, as it is not humanly possible to

give such an exhaustive list. The satisfaction Of the Government; however,

11-04-2021 (Page 13 of 29) www.manupatra.com Bangladesh University of Professionals (BUP)

must be based on some grounds. There can be no satisfaction if there are no

grounds for the same. There may be a divergence of opinion as to whether

certain grounds are sufficient to bring about the satisfaction required by the

section. One person may think one way, another the other way. If, therefore,

the grounds on which it is stated that the Central Government, or the State

Government was satisfied are such as a rational human being can consider

connected in some manner with the objects which were to be prevented from

being attained, the question of satisfaction except on the ground of mala

fides cannot be challenged in a Court.

34. It will be noticed that while laying down the rule as to subjective satisfaction of

the detaining authority on the question of sufficiency of the grounds it has also been

made clear that, the relevancy of the grounds is certainly justiciable and an objective

standard of rational human being for connecting the grounds with the objects which

were to be prevented from being attained was laid down. This was the unanimous,

view of the Court consisting of six learned Judges including the Chief Justice.

35. On the question of vagueness and in definiteness of grounds Chief Justice Kama

expounding the majority view also laid down that the grounds of detention which the

detaining authority was under a constitutional obligation to communicate to the

detenu at the earliest opportunity in order to enable him to make a representation

must not be vague and indefinite and observed that the question whether such

ground could give rise to the satisfaction required for making the order was outside

the scope of the enquiry on the Court, but the question whether the vagueness, and

indefinite nature, of the statement furnished to the detained persons was such as to

give him the earliest opportunity to make a representation to the authority was a

matter within the jurisdiction of the Court's enquiry and subject to the Court's,

decision.

36. B. K. Mukharjee, J., as he then was, restated this rule in the case of Shibban Lal

Saxena Vs. The State of Uttar Pradesh, AIR 1954 (SC) 179 in the following words:

It has been repeatedly held by this Court that the power to issue a detention

order under section 3 of the Preventive Detention Act depends entirely upon

the satisfaction of the appropriate authority specified in that section. The

sufficiency of the grounds upon which such satisfaction purports to be based

provided they have a rational probative value and are not extraneous to the

scope or purpose of the legislative provision cannot be challenged in a court

of law except on the grounds of mala fide.

37. It will be found that the rule as to subjective satisfaction was made subject to

some important qualifications, viz., firstly the grounds should have rational probative

value, secondly they should not fee extraneous to the scope or purpose of the

legislative provision and thirdly in case of the plea of mala fide, the grounds would

be subjected to further judicial security for finding out whether there had been a

colorable exercise of the power.

3 8 . In the case, referred to above another important point considered by the

Supreme Court of India was the question whether a detention could be considered to

be legal, if one of the two grounds on which the said detention was based was found

to be irrelevant, or non-existent. A similar question arose-in the case of Keshav

Talpade Vs. King Emperor, : MANU/PR/0001/1942 : AIR 1943 P.C. 1, referred to

above in another connection and in the said case Gowyer, C.J. expressed the view, of

11-04-2021 (Page 14 of 29) www.manupatra.com Bangladesh University of Professionals (BUP)

the Federal. Court of India in this regard in the following words at page 8 of the

report :

If a detaining authority give four reasons for detaining a man, without

distinguishing between them, and any two or three of the reasons are held to

be bad, it can never be certain, to what extent the bad reasons operated on

the mind of the authority or whether the detention order would have been

made at all if one or two good reasons had been before him.

39. In Shibban Lai Saxena's case, subsequent to the making the order of detention,

the Government' itself appears to have stated that one of the two grounds on which

the original order of detention was made was unsubstantial or non-existent, but it

was insisted that the remaining ground was sufficient to sustain the order of

detention. Mukharjee, J. expressed the view of the Court endorsing the above quoted

principle recognized by the Federal Court of India in Keshav Talpade's case which,

according to him, was sound and applicable to the facts of the case, in the following

words :

To say that the other ground, which still remains is quite sufficient to sustain

the order would be to substitute an objective judicial test for the subjective

decision of the executive authority which is against the legislative policy

underlying the statute, in such cases we think the position would be the

same as if one of these grounds was irrelevant for the purpose of the Act or

was wholly illusory and this would vitiate the detention order as a whole.

40. This principle was further explained in the case of Dwarkadas Bhatia Vs. State of

Jammu and Kashmir, AIR 1957 (SC) 164 in the following manner at page 168 of the

report:

Where power is vested in a statutory authority to deprive the liberty of a

subject on its subjective satisfaction with reference to specified matter, if

that satisfaction is stated to be based on a number of grounds or for variety

of reasons, all taken together, and if some out of them are found to be non-

existent or irrelevant the very exercise of that power is.

bad......................... because the matter being one for subjective

satisfaction, it must be properly based on all the reasons on which it purports

to be based. If some out of them are found to be non-existent or irrelevant

the Court cannot predicate what the subjective satisfaction of the said

authority would have been on the exclusion of those grounds or reasons. To

uphold the validity of such an order inspite of the invalidity of some of the

reasons or grounds would be to substitute the objective standards of the

Court for the subjective satisfaction of the statutory authority.

A qualification was however added to the above quoted extract to the following

effect:

...................................the Court must be satisfied that the vague and

irrelevant grounds are such as, if excluded, might reasonably have affected

the subjective satisfaction of the appropriate authority. It is not merely

because some, grounds or reason of a comparatively unessential nature is

defective that such an order based on subjective satisfaction can be held to

be invalid. The Court while anxious to safeguard the personal liberty of the

individual will not lightly interfere with such orders.

11-04-2021 (Page 15 of 29) www.manupatra.com Bangladesh University of Professionals (BUP)

41. It should however be noticed that there is a difference between a case in which,

some or one of the grounds are irrelevant or non-existent and a case in which some

or one of the grounds are vague or indefinite. In one case the order of detention

itself is rendered bad because of absence of proof of the necessary satisfaction of the

detaining authority, which is the foundation of the impugned order. But in the other

case, the furnishing of one or more vague grounds dots not affect the validity of the

order of detention itself, if such grounds though vague or indefinite, are not

irrelevant, but such grounds being vague or indefinite deprive the detenu of his

constitutional right of making representation at the earliest opportunity and thus

make continuation of detention illegal. When in the passage from the judgment in

Dwarkadas Bhatia's case as quoted above, the word, "vague" was used together with

the word "irrelevant", the word "vague" appears to have been used in the sense of

"non-existent" and not in its ordinary connotation.

42. The first case in which the Supreme Court of India had to consider the question

of vagueness of one of the several grounds and its effect upon the detention of the

detenu as the case of Dr Ram Krishna Bharadwaj Vs. The State of Delhi and others,

AIR 1953 (SC) 318. In the said case, one of the grounds on which the detenu was

charged with organizing the movement by enrolling volunteers among the refugees in

his capacity as the President of the Refugee Association in a certain area in Delhi was

adjudged to be vague, as no period of time was particularized. The other question

with arose in the said case is whether the detention of the detenu is rendered illegal

because of the fact that one of the several grounds is too vague to enable the detenu

to make a representation in respect of the said ground, and Patanjali Shastri, C.J. in

delivering the judgment of the Court laid down the law and explained the principle

underlying the same in the following words:

Preventive detention is a serious invasion of personal liberty and such

meagre safeguards as the constitution has provided against improper

exercise of the power must be jealously watched and enforced by the Court.

In this case the petitioner has the right, under Article 22(5) as interpreted by

this Court by a majority, to be furnished with particulars of the grounds of

his detention "sufficient to enable him to make a representation which on

being considered may give relief to him. We are of opinion that this

constitutional requirement must be satisfied with respect to each of the

grounds communicated to the person detained, subject of course to a claim

of privilege under clause (6) of Article 22. That not having been done with

regard to the ground mentioned in sub-para (e) of para 2 of the statement of

grounds, the petitioner's detention cannot be held to be in accordance with

the procedure established by law within the meaning of Article 21.

4 3 . In the case of Rameshwar Shaw Vs. The District Magistrate, Bardwan and

another, AIR 1964 (SC) 334, the Supreme Court of India, had to consider the affect

of both kinds of bad grounds, viz., irrelevant or non-existent grounds and Vague or

indefinite grounds and Gajendragadkar, J (as he then, was) after reference to law as

to subjective satisfaction as enunciated in the case of the State of Bombay Vs.

Atmaram Shridhan, AIR 1951 (SC) 157, stated the rule as to both kinds of bad

grounds in the following manner :

There is also no doubt that if any of the grounds furnished to the detenu are

found to be irrelevant while considering the application of the clauses (1) to

(iii) of section 3 (1) (a) and in that sense are foreign to the Act, the

satisfaction of the detaining authority on which the order of detention is

11-04-2021 (Page 16 of 29) www.manupatra.com Bangladesh University of Professionals (BUP)

based is open to challenge and the detention order is liable to the quashed.

Similarly, if some of the grounds supplied to the detenu are so vague that

they would virtually deprive the detenu of his statutory light of making a

representation that again may introduce a serious infirmity in the order of his

detention. If, however, the grounds on which the order of detention proceeds

are relevant and germane to the matters which fall to be considered under

section 3 (1)(a), it would not be open to the detenu to challenge the order of

detention by arguing that the satisfaction of the detaining authority is not

reasonably based on any of the said grounds.

44. The learned Judge went on to point out that in a case where the question of mala

fide is raised, the court is to apply an objective test to determine the state of

satisfaction of the detaining authority and made the following observation to explain

the principle involved in it:

It is however necessary to emphasize in this connection that though the

satisfaction of the detaining authority contemplated by section S (1) (a) is

the subjective satisfaction of the said authority, the cases may arise when the

detenu challenge the validity of his detention on the ground of mala fides

and in support of the said plea urge that along with other facts which show

mala fides, the court may also consider his grievance that the grounds served

on him cannot possibly or rationally support the conclusion drawn against

him by the detaining authority. It is only in this incidental manner and in

support of the plea of mala fides that this question can become

justiciable.............

45. In the case of Rameshar Lal Patwari Vs. The State of Bihar, AIR 1968(SC) 1303,

the Supreme Court of India appears to have examined the materials relating, to the

grounds of detention and found that, one of the grounds was false and two of the

grounds were vague, that another ground was "a case of jumping to a conclusion

which is being lamely justified, when it is questioned with written record" and that as

to the remaining one, there was no reply on behalf of the detaining authority to the

denial given by the detenu to the allegations contained in the said ground and held

that the detention had been vitiated by both kinds of defective grounds. In this cases

the materials on record were subjected to judicial scrutiny for determining whether

there was any factual basis of the grounds communicated to the detenu,

independently of the question of mala fide, notwithstanding a contrary opinion

expressed in some of the earlier cases.

4 6 . Hidayatullah, J, as he then was, who delivered the judgment of the court,

explained the view of the court of pages 1305 to 1306 of the report in the following

words:

The formation of the opinion about detention rests with the Government or

the officer authorized. Their satisfaction is all that the law speaks of and the

courts are not constituted an appellate authority. Thus the sufficiency of the

grounds cannot be agitated before the court. However, the detention of a

person without a trial, merely on the subjective satisfaction of an authority

however, high, is a serious matter. It must require the closest scrutiny of the

material on which the decision is formed, of leaving no room for errors or at

least avoidable errors. The very reason that the courts do not consider the

reasonableness of the opinion formed or the sufficiency of the material on

which it is based, indicates the need for the greatest circumspection on the

11-04-2021 (Page 17 of 29) www.manupatra.com Bangladesh University of Professionals (BUP)

part of those who wield this power over others. Since the detenu is not

placed before a Magistrate and has only a right of being supplied the grounds

of detention with a view to his making representation to the Advisory Board,

the grounds must not be vague or indefinite and must afford a real

opportunity to make a representation against the detention. Similarly, if a

vital ground is shown to be nonexisting so that it could not have and ought

not to have played a part in the material for consideration, the court may

attach some importance to this fact.

47. In the case of Motilal Jain Vs. The State of Bihar, AIR 1968 (SC) 1309 one of the

grounds was found to be vague, as well as irrelevant and another ground was also

found to be non-existent and the judgment of the Court was to the following effect :

The defects noticed in the two grounds mentioned above are sufficient to

vitiate the order of detention impugned in these proceedings as it is not

possible to hold that those grounds could not have influenced the decision of

the detaining authority. Individual liberty is a cherished right one of the most

valuable fundamental rights guaranteed by our Constitution to the citizens of

this country. If that right is invaded excepting strictly in accordance with law

the aggrieved party is entitled to appeal to the judicial power of the State for

relief. We are not unaware of the fact that the interest of the society is no

less important than that of the individual. Our Constitution has made

provision for safeguarding the interests of the society. Its provisions

harmonies the liberty of the individual with social interests. The authorities

have to act solely on the basis of those provisions. They cannot deal with the

liberty of the individual in a causal manner, as has been done in this case.

Such an approach does not advance the true social interest. Continued

indifference to individual liberty is bound to erode the structure of our

democratic society. We wish that the High Court had examined the complaint

of the appellant more closely.

48. A similar view was expressed in re Shushanta Goswami, AIR 1969 (SC) 1004. We

may also refer in this connection to the view of the Supreme Court of India as

expressed in Pushkar Mukharjee's case on which reliance was placed by the learned

Deputy Attorney-General on the question of subjective satisfaction of the detaining

authority. It has been pointed out in the said case that neither the reasonableness of

the satisfaction of the detaining authority nor the adequacy of the material on which,

the said satisfaction purports to rest can be questioned or examined in a court of law,

but it has, at the same time, been emphasized that the question whether an order of

detention has been vitiated by an irrelevant ground or the detention has been

rendered illegal for communicating vague grounds fails for determination by the

court. It has also been observed in this decision that in case of a plea of mala fide,

the question whether the grounds served on the detenu can rationally support the

conclusion drawn against him becomes justiciable, although in an incidental manner.

49. Another point of some importance which has been decided in this case is that

mere commission of certain specific offences does not bring the offender within the

purview of the Preventive Detention Act unless it can be said that they are likely to

affect public order. A mere disturbance of law and order leading to disorder is not

necessarily sufficient for taking action under the said law, but a disturbance which

will affect public order comes within the scope of this Act This principle was further

elaborated in Arun Ghose Vs. The State of West Bengal, AIR 1970 (SC) 1228.

11-04-2021 (Page 18 of 29) www.manupatra.com Bangladesh University of Professionals (BUP)

50. On an analysis of the decisions of the Indian Supreme Court to which reference

has been made above it is clear that the tests laid down by the said court for

determining whether there had been the necessary satisfaction of the appropriate

authority are not purely subjective and such a question is not, in all cases, beyond

the pale of judicial determination. According to the said view the question whether

the grounds of detention have any relation to the object relevant under the law of

preventive detention is a matter of judicial scrutiny. Whether the grounds are vague

or indefinite and are not sufficient for this purpose of enabling the detained person,

to make an effective representation is also a matter which is to be objectively

determined. We should not, of course, lose sight of the fact that there is a subjective

element also in the rule laid down by the Supreme Court of Pakistan and it may be

noted that it has been emphasized in Baqul Baluch's case that it is not the purpose of

a judicial authority reviewing executive actions to sit on appeal over the executive or

to substitute the discretion of the court for that of the administrative agency and it

has been pointed out also in Begum Shorish Kashmiri's case that the Court is not

concerned with either adequacy or sufficiency of the grounds upon which the action

is taken. On the other hand, it has been conceded also in the Indian cases that when

the question of Bona fide of the executive action is raised, the Court shall have to

apply necessarily the objective test for determining whether the impugned action was

merely a colorable exercise of power or a fraud Upon the statute. Nevertheless, when

the Supreme Court of Pakistan, has stressed in the clearest language that for the

appropriate discharge of its judicial function the superior court must have before it

the materials upon which the executive authority has purported to act and that the

said materials should be such as could have been the basis on which a reasonable

man would have formed the opinion that the person detained had brought himself

within the mischief of the statute, it is undoubtedly a distinct advance the from

hitherto accepted limited jurisdiction of judicial review in respect of the masters

relating to preventive detention.

51. The view of a Full Bench of the Dacca High Court in the case of Mahbub Assam

Vs. The Government of East Pakistan, PLD 1959 Dae. 774 on the question whether

the satisfaction of the detaining authority is subjective or objective deserves special

mention. In that case the detention of Mr. Abul Mansur Ahmed, an Advocate and

some time a Minister in the Central Cabinet of the Government of Pakistan, under the

East Pakistan Public Safety Ordinance, 1958 was challenged. The Division Bench

which heard the case referred it to a Full Bench for a decision on the question

whether in a case where one or more of several grounds, but not all, are beyond the

scope or ambit of the Act or Ordinance conferring power to detain, the detention was

illegal. Amin Ahmed, C.J., in delivering the judgment of the Full Bench, consisting of

himself, Ispahani, Akbar, Hamoodur Rahman and Khan, JJ., generally dealt with the

powers of the court in respect of an order made for preventive detention and made

the following observation at page 809 of the report:

The process of examining the grounds by the court for the purpose of

determining whether they are indefinite or irrelevant, or relevant or sufficient

to enable the detenu to make a representation, or whether the Government

has acted bonafide or not, or whether it is beyond the, ambit of the Act

involves, in my opinion, not only the subjective satisfaction of the detaining

authority but also the objective satisfaction of the court according to the facts

and circumstances of each case though this may be at different stages. The

distinction between facts from which conclusions are drawn and facts which

are called grounds is sometimes a thin one. Similarly, the demarcation

between a subjective standard and objective standard is also sometimes a

11-04-2021 (Page 19 of 29) www.manupatra.com Bangladesh University of Professionals (BUP)

thin one.......................Although the court cannot, as it is judicially held,

consider the sufficiency of the grounds on which satisfaction is based and the

vagueness of the grounds is not justiciable at the initial stage when the order

is made and so the order cannot be said to be invalid ab initio, the same

vagueness of the ground is nevertheless justiciable at a later stage, so that, if

vagueness renders the making of; the presentation difficult, the continuance

of the detention at once becomes illegal. In other words, the implied

requirement that the grounds must be such as will enable the detenu to make

a 'representation indicates the quality of the grounds on which the detention

order is based and involves an objective test, i.e., whether in the opinion of

the court, and not in that of the detaining authority such grounds have the

quality or attribute for making the representation of the detenu and it is not

left to the subjective opinion of the authority which makes the order of

detention.

The Full Bench gave an affirmative answer to the question referred to it,

stating that in a case where one or more but not all, of several grounds of

detention are beyond the scope and ambit of the law authorizing preventive

detention, the detention will be illegal unless the said ground or grounds are

of insignificant or unessential nature.

52. The upshot of all these discussions is that under the well settled principle of law

endorsed by a long line of judicial Authorities, any person charged with the authority

of taking decisions affecting the rights and liberties of the citizens of the State has

the corresponding duty of acting judicially and the superior courts having supervisory