Professional Documents

Culture Documents

This Content Downloaded From 129.120.93.218 On Mon, 21 Dec 2020 16:59:11 UTC

Uploaded by

Garrison GerardOriginal Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

This Content Downloaded From 129.120.93.218 On Mon, 21 Dec 2020 16:59:11 UTC

Uploaded by

Garrison GerardCopyright:

Available Formats

Consciousness, Creativity, and Complex Time in MusicAuthor(s): Guerino Mazzola

Source: Perspectives of New Music , Vol. 57, No. 1-2, Perspectives on and around John

Rahn (Winter/Summer 2019), pp. 431-439

Published by: Perspectives of New Music

Stable URL: https://www.jstor.org/stable/10.7757/persnewmusi.57.1-2.0431

JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide

range of content in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and

facilitate new forms of scholarship. For more information about JSTOR, please contact support@jstor.org.

Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of the Terms & Conditions of Use, available at

https://about.jstor.org/terms

Perspectives of New Music is collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve and extend access

to Perspectives of New Music

This content downloaded from

129.120.93.218 on Mon, 21 Dec 2020 16:59:11 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

CONSCIOUSNESS, CREATIVITY, AND

COMPLEX TIME IN MUSIC

GUERINO MAZZOLA

1. TIME IN PHYSICS

in modern

Ophysics of the twentieth century was the revolutionary reconceptu-

NE OF THE MOST DRAMATIC ONTOLOGICAL CHANGES

alization of time. It started with Albert Einstein’s special relativity,

where he embedded time in a four-dimensional space-time. Einstein

had adopted the space-time approach of Hermann Minkowski, who, in

a famous statement stated that “[h]enceforth, space for itself, and time

for itself shall completely reduce to a mere shadow, and only some sort

of union of the two shall preserve independence.”1 Time then became

a multiple variable, the Newtonian singular “divine” time was replaced

by a plurality, one in every frame of reference, and different frame times

being related to each other by the Lorentz transformation of space-time.

The second revolution of the time concept was introduced by

Stephen Hawking (among others) in order to solve singularity

problems of the Big Bang model of the evolution of our universe in

the initial moment some 13.8 billion years ago. Hawking’s concept of

time steps from the real time axis to the plane of complex numbers:

Time now has two coordinates t = tR + i tI, the real time tR and the

This content downloaded from

129.120.93.218 on Mon, 21 Dec 2020 16:59:11 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

432 Perspectives of New Music

imaginary time tI. This complex ontology has also been proposed and

studied by physicists Itzak Bar and John Terning (2010).

These two revolutions in the concept of time, however, did not apply

to the human cognitive reality, except in Einstein’s case for the meta-

phorical and vague popular statement that “everything is relative.”2

In what follows, I will introduce the thesis that complex time could

be a key to some of the most virulent problems in the artistic reality of

music, namely the nature of artistic consciousness and creativity,

especially from the perspective of musical performance. This thesis is

also in the spirit of John Rahn’s unique proactive spirit in music theory.

2. CONSCIOUSNESS AND CREATIVITY IN MUSIC

The performing musician, whether rendering a composed work from a

score, or creating in a more-or-less free or improvisatory fashion—in

jazz for example—faces a complex combination of memory, technique,

gestures, and the balance in the famous temporal καιρός (Kairos)

between past and future moments. Successful musical performance is a

highly creative and complex activity, at the very center of which is the

sophisticated consciousness of the artist which manages the harmo-

nious collaboration of the above-mentioned components in real time.

“In real time” means in every moment of the performance; more

precisely, in every infinitesimal point of physical time. I know as a per-

forming free jazz pianist what every good performer experiences: the

complex processual unfolding of musical performance is a rich machinery

that defines and is happening in a big space of consciousness and

presence. This configuration is described in Mazzola (2011, ch. 4.12).

This artistic complexification is however a miraculous phenomenon

since it happens in “no time,” in the physical moment of presence. We

are confronted with a big “space” of consciousness that occupies no

time in the physical time line. This makes evident the problematic

status of creative artistic consciousness, and of consciousness in

general: How can it be that a rich processuality is construed in no

physical time? It seems that this type of phenomenon is enabled by the

existence of a huge “space” of consciousness that is attached to every

moment of physical time. This situation in its acute extremism in

performing arts questions a classical rationale for understanding and

even defining consciousness in cognitive and neuroscience. If no extra

“space” is added to the classical physical ontology, consciousness

cannot cope with its performative quality. So let us present the

following thesis:

This content downloaded from

129.120.93.218 on Mon, 21 Dec 2020 16:59:11 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

Consciousness, Creativity, and Complex Time in Music 433

Thesis: Any workable concept of consciousness, and in particular

artistic consciousness in the performing arts, must be built upon a “space-

time” that is added to the classical physical spatio-temporal ontology.

3. CARTESIAN DUALISM

The above thesis is given a familiar philosophical perspective if we

review the Cartesian dualism which Descartes set up in his Principia

philosophiae (Descartes 1983), where he describes the three substances

of being: res extensa, res cogitans, and God. Human existence is

comprised of res extensa and res cogitans, and their mysterious

interaction. Res cogitans is strongly associated with consciousness. It is

not clear where this interaction should happen (Descartes’s idea of the

pineal gland being the crossing locus simply locates the interaction in

the physical, which would negate the dualism, but which would also

make res cogitans secondary to res extensa, thus res cogitans would no

longer be a substance). For Descartes a substance is something that

can exist without the existence of any other substance and can stand as

the indubitable foundation for knowledge and science, which means in

particular that the substance of res cogitans is not comprised in the

physical ontology of res extensa (and vice versa).

Cartesian dualism is derived from this double substantiality of

human existence; we are “split” into the physicality of our embodi-

ment and the mentality of consciousness. This configuration is not

only related to a dual metaphysics, but more specifically to a double

locality: there is a physical space as well as a mental space, and both are

irreducibly separate from each other. Let us be clear about the still-

valid dualism that is opposed to the often erroneously claimed

reductionism of mentality to physics in neurosciences. The partisans of

radical neuroscience (see Gazzaniga [2018], for example) claim that

ultimately, our thoughts are (however complex) neuronal activities:

i.e., that thinking is the surface of physical activities. This argument is

invalid for the following reason. Suppose we could, for example,

explain mathematical thoughts by neuronal activities. Then the

description and analysis of such activities would necessarily be enabled

by complex mathematical formulas, such as those difficult partial

differential equations that describe the axonal transfer of electrical

voltage. In other words, the explanation of mathematical thoughts

would presuppose a sophisticated mathematical machinery, which is a

vicious circle: explaining math by use of math has no added value.

This content downloaded from

129.120.93.218 on Mon, 21 Dec 2020 16:59:11 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

434 Perspectives of New Music

Cartesian dualism therefore is a second argument for our above

thesis that consciousness in creative artistic performance must occur in

a “space” of consciousness that is added to the physical space-time

ontology.

But we have to understand that this dualism is not the solution of

the question about the ontology of consciousness, the question of how

the mental space is added to the physical reality.

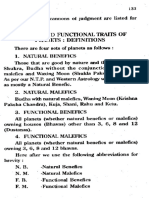

4. INTRODUCING COMPLEX TIME IN MUSIC: A SOLUTION?

My proposal regarding the added mental space of consciousness relates

to complex time. The fundamental idea is that time has a real and an

imaginary coordinate, as suggested by theoretical physics. When we

consider space-time with complex time, we get a five-dimensional real

vector space ST = ℝ3 ⊕ ℂ that is the union of two four-dimensional

subspaces, ST = RST + IST = ℝ3 ⊕ ℝ + ℝ3 ⊕ iℝ, the physical space-

time RST and the mental space-time IST; see Example 1.

The physical and mental subspaces have the spatial part in common:

RST ∩ IST = ℝ3. This is what replaces Descartes’s pineal gland. This

configuration separates res extensa from res cogitans, but it also gives

them a shared subspace.

EXAMPLE 1: DESCARTES’S DUALISM RESOLVED

IN A SPACE-TIME WITH COMPLEX TIME

This content downloaded from

129.120.93.218 on Mon, 21 Dec 2020 16:59:11 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

Consciousness, Creativity, and Complex Time in Music 435

The next step must be a theory of interaction between these four-

dimensional subspaces which comprises the laws of physics and the

dynamics of consciousness. No such model has been proposed so far,

but we have nevertheless initiated research that models musical

performance as a transformation of symbolic reality (of a score for

example) to physical reality, see Mazzola (2018, Vol. III).

5. SYMBOLIC AND PHYSICAL GESTURES IN PERFORMANCE

In my previous performance theory, I dealt with the transformation of

note symbols, as given in a common score, to physical (acoustical)

events. This is also the approach that is taken by contemporary per-

formance theory as initiated by the Swedish school of Johan Sundberg

(1991). My theory used quite sophisticated methods of differential

geometry (see Mazzola [2018], Vol. II). It was one of the most

important results of my research that the refinement process of

performance involves Lie derivatives of performance vector fields.

In view of the union of physical and symbolic/mental realities as

suggested by the above model of space-time, it became necessary to

also represent the performance process more as embodied than as the

acoustical rendition of abstract note symbols in performance. In Mazzola

(2018, Vol. III), I set forth an embodied performance theory which

instead of note sequences deals with musical gestures, configurations of

curves in space-time that may be realized by the movements of parts of

the human body: the limbs, arms, and hands of pianists, for example.

This gestural approach is also paralleled by the attractive physical

theory of strings. String theory does not describe elementary objects as

points that move in space-time, but as parametrized curves which move

through space-time and thereby trace a “world-sheet” (instead of the

well-known “world-line” of traditional particle dynamics). In my

musical performance theory, the string would be a musical gesture, for

example an up-down movement of a pianist’s finger (Mazzola 2018,

Vol. II) Its world-sheet would be the surface that is spanned between

the symbolic finger movement as described on the score and the

physical movement in performance, where a real physical gesture is

happening. See Example 2 for an illustration of such a world-sheet.

The left blue rectangular line is the symbolic gesture, while the right

red curve is the physical realization thereof.

The performance theory of musical gesture strings parallels the

physical theory in that the shape of such a world-sheet is determined

by the minimization of a Lagrange potential that is associated with a

world-sheet (see Mazzola [2018, Vol. III] for details).

This content downloaded from

129.120.93.218 on Mon, 21 Dec 2020 16:59:11 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

436 Perspectives of New Music

In this model, the symbolic gesture evolves in imaginary time of

consciousness, while the physical one evolves in physical time. This

means that we have a world-sheet of time from the symbolic/mental

time line to the physical one. In our theory, this world-sheet turns out

to be a conformal mapping in complex space. Example 3 shows the

temporal world-sheet and its intermediate levels when viewed as a

function of real/physical time.

Here we face a completely new research into time when morphing

from mental to physical time.

One of the important new results of this theory is completely parallel

to the result mentioned above from classical performance theory

regarding the role of the Lie derivative in the refinement process of

performance vector fields. Again, there is an operator of Lie derivative

type that captures refinements of gestural performance.

This content downloaded from

129.120.93.218 on Mon, 21 Dec 2020 16:59:11 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

Consciousness, Creativity, and Complex Time in Music 437

x

4 6

0 2

s 0

-1

6

4

2

y

0

EXAMPLE 2: WORLD-SHEET OF AN UP-DOWN MOVEMENT

OF A PIANIST’S FINGER

fixed

fixed

intermediate states

intermediate states

at initial real time open

at real time t

intermediate states

1.0

at real time t

a(s) 0.8

0.6

0.4

0.2

a(0) 0.0

-0.2

0.0 0.2 0.4 0.6 0.8 1.0 1.2

initial real time real time t

EXAMPLE 3: THE WORLD-SHEET OF COMPLEX TIME OF A GESTURE

AND ITS INTERMEDIATE STATES

This content downloaded from

129.120.93.218 on Mon, 21 Dec 2020 16:59:11 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

438 Perspectives of New Music

NO T E S

1. Hermann Minkowski, “Space and Time,” in Hendrik A. Lorentz,

Albert Einstein, Hermann Minkowski, and Hermann Weyl, The

Principle of Relativity: A Collection of Original Memoirs on the

Special and General Theory of Relativity (Dover, New York, 1952),

p. 75.

2. In the case of complex time, I repeatedly emailed Hawking, but never

got an answer. I also discussed the issue with other theoretical

physicists, but they consistently thought of the imaginary component

as being a mathematical method, not an ontological or even

human cognitive topic.

This content downloaded from

129.120.93.218 on Mon, 21 Dec 2020 16:59:11 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

Consciousness, Creativity, and Complex Time in Music 439

REFERENCES

Bar, Iztak, and John Terning. 2010. Extra Dimensions in Space and

Time. Heidelberg: Springer.

Descartes, René. 1983. Principles of Philosophy [Principia philosophiae].

Translated and edited by Valentine Rodger and Reese P. Miller.

Dordrecht: Reidel.

Gazzaniga, Michael. 2018. The Consciousness Instinct: Unraveling the

Mystery of How the Brain Makes the Mind. New York: Farrar, Straus

and Giroux.

Mazzola, Guerino. 2011. Musical Performance. Heidelberg: Springer.

Mazzola, Guerino, et al. 2018. The Topos of Music, Second edition in

four volumes (Theory, Performance, Gestures, Roots). Heidelberg:

Springer.

Sundberg, Johan. 1991. “Music Performance Research. An Overview,”

in Music language, Speech and Brain, edited by Johan Sundberg,

Lennart Nord, and Rolf Carlson. London: Palgrave, 173–183.

This content downloaded from

129.1ff:ffff:ffff:ffff:ffff on Thu, 01 Jan 1976 12:34:56 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

You might also like

- Humanity, What a Story!: A Compelling Portrait of Our SocietyFrom EverandHumanity, What a Story!: A Compelling Portrait of Our SocietyNo ratings yet

- Chapter Iii: Time Disclosed. An Investigation of Time, Space, and BeingDocument31 pagesChapter Iii: Time Disclosed. An Investigation of Time, Space, and BeingJuan Trujillo MendezNo ratings yet

- Visions of The Emerald BeyondDocument8 pagesVisions of The Emerald BeyondAlienne V.No ratings yet

- Sorli Ineractions Between SDocument5 pagesSorli Ineractions Between SDeepak GoyalNo ratings yet

- Godel, Escherian Staircase and Possibility of Quantum Wormhole With Liquid Crystalline Phase of Iced-Water - Part I: Theoretical UnderpinningDocument6 pagesGodel, Escherian Staircase and Possibility of Quantum Wormhole With Liquid Crystalline Phase of Iced-Water - Part I: Theoretical UnderpinningScience DirectNo ratings yet

- The Tao of Physics - A Very Brief SummaryDocument7 pagesThe Tao of Physics - A Very Brief SummaryRishabh JainNo ratings yet

- Matter Is Not Matter PDFDocument10 pagesMatter Is Not Matter PDFrajishrrr100% (6)

- The Purpose of Life PDFDocument11 pagesThe Purpose of Life PDFHeoel GreopNo ratings yet

- A Systemic and Hyperdimensional Model of A Conscious Cosmos and The Ontology of Consciousness in The UniverseDocument17 pagesA Systemic and Hyperdimensional Model of A Conscious Cosmos and The Ontology of Consciousness in The UniverseMythastriaNo ratings yet

- The Rol of affectinAIDocument31 pagesThe Rol of affectinAIJennifer Andrea SosaNo ratings yet

- From Kant To Cant 7087 Stephen Kern The Culture of Time and Space: 1880-1918.Document5 pagesFrom Kant To Cant 7087 Stephen Kern The Culture of Time and Space: 1880-1918.j9z83fNo ratings yet

- Concerning Time, Space and MusicDocument18 pagesConcerning Time, Space and MusicChrisTselentisNo ratings yet

- Mesquita - Concepts of Time and MusicDocument9 pagesMesquita - Concepts of Time and MusicPaulo Vinícius Panegacci dos SantosNo ratings yet

- Epistemological Problems of Dialectical MaterialismDocument24 pagesEpistemological Problems of Dialectical MaterialismCharles TeixeiraNo ratings yet

- Eli During, Durations and Simultaneities:Temporal Perspectives and Relativistic Time Inwhitehead and BergsonDocument25 pagesEli During, Durations and Simultaneities:Temporal Perspectives and Relativistic Time Inwhitehead and BergsontopperscottNo ratings yet

- Chronotope (NXPowerLite Copy) PDFDocument3 pagesChronotope (NXPowerLite Copy) PDFalpar7377No ratings yet

- The Collapse of Objective Reality 7.3Document32 pagesThe Collapse of Objective Reality 7.3antonio_ponce_1No ratings yet

- Xy The Unity of Human Knowledge: See General Introduction, andDocument6 pagesXy The Unity of Human Knowledge: See General Introduction, andChristos DedesNo ratings yet

- (Henri Lefebvre .8-40Document33 pages(Henri Lefebvre .8-40Ionuts IachimovschiNo ratings yet

- Analogia Entis According To Brentano - MelandriDocument8 pagesAnalogia Entis According To Brentano - MelandriricardoangisNo ratings yet

- God in A Quantum World PDFDocument17 pagesGod in A Quantum World PDFOarga Catalin-Petru100% (1)

- Sixth AttemptDocument21 pagesSixth AttemptBo-ErikNo ratings yet

- Techne 2017 0021 0002 0132 0170Document39 pagesTechne 2017 0021 0002 0132 0170tigubarcelos2427No ratings yet

- Fx0Shbotpg1Fsdfqujpo (Pfuifbo4Djfodfbtb$Vmuvsbmɨfsbqfvujdt: #Sfou O3pccjotDocument14 pagesFx0Shbotpg1Fsdfqujpo (Pfuifbo4Djfodfbtb$Vmuvsbmɨfsbqfvujdt: #Sfou O3pccjotrasmith_idNo ratings yet

- Science and AestheticsDocument5 pagesScience and AestheticsrobertogermanoNo ratings yet

- Grey Room, Inc. and The Massachusetts Institute of TechnologyDocument27 pagesGrey Room, Inc. and The Massachusetts Institute of TechnologyjohnNo ratings yet

- Arne Næss and The Idea of An Ontological Thickness of The LocalDocument9 pagesArne Næss and The Idea of An Ontological Thickness of The LocalAJHSSR JournalNo ratings yet

- Newton - de GravitationeDocument4 pagesNewton - de GravitationeOmar KassemNo ratings yet

- Lefebvre PDFDocument40 pagesLefebvre PDFhokupokus fidibus100% (3)

- Lecture NTUA 11 12 23 10 12 EngDocument93 pagesLecture NTUA 11 12 23 10 12 EngConstantine KirichesNo ratings yet

- Time, Consciousness and Quantum Events in Fundamental Spacetime GeometryDocument10 pagesTime, Consciousness and Quantum Events in Fundamental Spacetime GeometrynikesemperNo ratings yet

- New Dialogue Between Science and Christian FaithDocument5 pagesNew Dialogue Between Science and Christian FaithAlexandre ChoiNo ratings yet

- 22 TimeDocument12 pages22 TimeHardik BhandariNo ratings yet

- Advaita Vedanta and Quantum Physics - How Human Consciousness Creates Reality.Document11 pagesAdvaita Vedanta and Quantum Physics - How Human Consciousness Creates Reality.Bryan GraczykNo ratings yet

- Mu Place: Imagining How An Architectural Surface Could Respond To OccupationDocument23 pagesMu Place: Imagining How An Architectural Surface Could Respond To OccupationSarah NeaultNo ratings yet

- What Is Time-Thoughts of A PhysicistDocument12 pagesWhat Is Time-Thoughts of A PhysicistBlup BlupNo ratings yet

- Body, Space, Place - GómezDocument28 pagesBody, Space, Place - GómezmarisagmzNo ratings yet

- The Total Theory IiDocument11 pagesThe Total Theory IiResearch Publish JournalsNo ratings yet

- Philosophies 04 00001Document15 pagesPhilosophies 04 00001Ahmed SpecialNo ratings yet

- Cuencas Hidrograficas - InglesDocument11 pagesCuencas Hidrograficas - InglesRega JuliusNo ratings yet

- The Validity and Significance of Nietzsche's Doctrine of The Eternal Return of The SameDocument12 pagesThe Validity and Significance of Nietzsche's Doctrine of The Eternal Return of The SameRowan G TepperNo ratings yet

- Chomsky, Noam From Language and Problems of Knowledge PDFDocument3 pagesChomsky, Noam From Language and Problems of Knowledge PDFArmando_LavalleNo ratings yet

- Beyond The Material UniverseDocument25 pagesBeyond The Material UniversePaolopiniNo ratings yet

- Gravity BookDocument79 pagesGravity Booksatish acu-healerNo ratings yet

- (Anna Greenspan) Capitalism's Transcendental Time PDFDocument225 pages(Anna Greenspan) Capitalism's Transcendental Time PDFAnonymous SLWWPRNo ratings yet

- How Unconditioned Consciousness, Infinite Information, Potential Energy, and Time Created Our UniverseDocument15 pagesHow Unconditioned Consciousness, Infinite Information, Potential Energy, and Time Created Our UniverseLeon H. MaurerNo ratings yet

- Vol 15 No 1 Roy Why Metaphysics Matters PDFDocument28 pagesVol 15 No 1 Roy Why Metaphysics Matters PDFmrudulaNo ratings yet

- Iannis Xenakis Music Composition Treks: Musical UniversesDocument2 pagesIannis Xenakis Music Composition Treks: Musical UniversesChokoMilkNo ratings yet

- Meaning of Place in Sacred ArchitectureDocument10 pagesMeaning of Place in Sacred ArchitectureRiya JosephNo ratings yet

- Space and Geometry in The B DeductionDocument31 pagesSpace and Geometry in The B DeductionOscar Eduardo Ocampo OrtizNo ratings yet

- 3 The Inaugural Dissertation of 1770 and The Problem of Metaphysics - KopyaDocument3 pages3 The Inaugural Dissertation of 1770 and The Problem of Metaphysics - KopyaÜmit ÇakmakNo ratings yet

- Intraexpressive Resonance in The FragmenDocument13 pagesIntraexpressive Resonance in The FragmenClaudia MonginiNo ratings yet

- Butterfield LeibnClarkeDocument9 pagesButterfield LeibnClarkerebe53No ratings yet

- Musings On Quantum Music: Can Quantum Music Bring Us Closer To Objective Beauty?Document6 pagesMusings On Quantum Music: Can Quantum Music Bring Us Closer To Objective Beauty?Nondoda ChagiNo ratings yet

- Complex Space-Time An Unified Platform - EDocument6 pagesComplex Space-Time An Unified Platform - EX JNo ratings yet

- Space - In.spave. Astrology Ce0174bce3Document6 pagesSpace - In.spave. Astrology Ce0174bce3NateNo ratings yet

- Goethean Science and The Reciprocal SystemDocument7 pagesGoethean Science and The Reciprocal SystemRemus BabeuNo ratings yet

- Cover Letter and Essay For Postdoc Research at Warwick Philosophy - Cengiz ErdemDocument24 pagesCover Letter and Essay For Postdoc Research at Warwick Philosophy - Cengiz ErdemCengiz ErdemNo ratings yet

- Cosmic Understanding: Philosophy and Science of the UniverseFrom EverandCosmic Understanding: Philosophy and Science of the UniverseNo ratings yet

- Hildegard Westerkamp and The Ecology of Sound As Experience. Notes On Beneath The Forest FloorDocument4 pagesHildegard Westerkamp and The Ecology of Sound As Experience. Notes On Beneath The Forest FloorGarrison GerardNo ratings yet

- Roll Over Tchaikovsky - Russian Popular M Amico StephenDocument337 pagesRoll Over Tchaikovsky - Russian Popular M Amico StephenGarrison GerardNo ratings yet

- Cox - 8 Etudes NM9 - 04cox - 051-074Document24 pagesCox - 8 Etudes NM9 - 04cox - 051-074Garrison GerardNo ratings yet

- Cox Clairvoyance NM1Document18 pagesCox Clairvoyance NM1Garrison GerardNo ratings yet

- Cox - 8 Etudes NM9 - 04cox - 051-074Document24 pagesCox - 8 Etudes NM9 - 04cox - 051-074Garrison GerardNo ratings yet

- University of North Texas College of Music: CEMI Computer Music Graduate SymposiumDocument2 pagesUniversity of North Texas College of Music: CEMI Computer Music Graduate SymposiumGarrison GerardNo ratings yet

- Jennifer Stoever The Sonic Color Line - Introduction and NotesDocument34 pagesJennifer Stoever The Sonic Color Line - Introduction and NotesGarrison GerardNo ratings yet

- This Content Downloaded From 129.120.93.218 On Mon, 22 Feb 2021 15:42:05 UTCDocument19 pagesThis Content Downloaded From 129.120.93.218 On Mon, 22 Feb 2021 15:42:05 UTCGarrison GerardNo ratings yet

- Rhythmic Deviance in The Music of MeshuggahDocument17 pagesRhythmic Deviance in The Music of MeshuggahGarrison Gerard100% (2)

- Bajo El Hechizo: Marimba, Guitar, PianoDocument24 pagesBajo El Hechizo: Marimba, Guitar, PianoGarrison Gerard100% (1)

- MICHELLE DUNCAN The Operatic Scandal of The Singing Body - Voice, Presence, PerformativityDocument25 pagesMICHELLE DUNCAN The Operatic Scandal of The Singing Body - Voice, Presence, PerformativityGarrison GerardNo ratings yet

- Teasing The Ever-Expanding Sonnet From Pierre Boulez's Musical PoeticsDocument27 pagesTeasing The Ever-Expanding Sonnet From Pierre Boulez's Musical PoeticsGarrison GerardNo ratings yet

- The Affect Theory Reader - (An Inventory of Shimmers Gregory J. Seigworth & Melissa Gregg)Document26 pagesThe Affect Theory Reader - (An Inventory of Shimmers Gregory J. Seigworth & Melissa Gregg)Garrison GerardNo ratings yet

- William Fourie Musicology and Decoonial Analysis in The Age of BrexitDocument15 pagesWilliam Fourie Musicology and Decoonial Analysis in The Age of BrexitGarrison GerardNo ratings yet

- Morgan On Ives:MahlerDocument10 pagesMorgan On Ives:MahlerGarrison GerardNo ratings yet

- Pro Tester ManualDocument49 pagesPro Tester ManualRobson AlencarNo ratings yet

- Purposive Communication NotesDocument33 pagesPurposive Communication NotesAlexis DapitoNo ratings yet

- Chapter Vii. Damascius and Hyperignorance: Epublications@BondDocument10 pagesChapter Vii. Damascius and Hyperignorance: Epublications@BondRami TouqanNo ratings yet

- Chapter 10 - Process CostingDocument83 pagesChapter 10 - Process CostingXyne FernandezNo ratings yet

- Topic: Choppers: Presented By: Er. Ram Singh (Asstt. Prof.) Deptt. of EE BHSBIET LehragagaDocument89 pagesTopic: Choppers: Presented By: Er. Ram Singh (Asstt. Prof.) Deptt. of EE BHSBIET LehragagaJanmejaya MishraNo ratings yet

- Daftar Isian 3 Number Plate, Danger Plate, Anti Climbing DeviceDocument2 pagesDaftar Isian 3 Number Plate, Danger Plate, Anti Climbing DeviceMochammad Fauzian RafsyanzaniNo ratings yet

- Autodesk 3ds Max SkillsDocument18 pagesAutodesk 3ds Max SkillsJuan UrdanetaNo ratings yet

- Cibse TM65 (2020)Document67 pagesCibse TM65 (2020)Reli Hano100% (1)

- ISMR B-School BrochureDocument28 pagesISMR B-School Brochurerahul kantNo ratings yet

- List Katalog Fire Hydrant (Box)Document3 pagesList Katalog Fire Hydrant (Box)Sales1 mpicaNo ratings yet

- ABAP On HANA TopicsDocument23 pagesABAP On HANA Topicsrupesh kumarNo ratings yet

- Position, Velocity and AccelerationDocument12 pagesPosition, Velocity and Accelerationpeter vuNo ratings yet

- Jurnal Ari Maulana Ullum Sasmi 1801038Document12 pagesJurnal Ari Maulana Ullum Sasmi 180103803. Ari Maulana Ullum Sasmi / TD 2.10No ratings yet

- Technical Data Sheet: BS-510 All Pressure Solvent CementDocument1 pageTechnical Data Sheet: BS-510 All Pressure Solvent CementBuwanah SelvaarajNo ratings yet

- Eco-Friendly Fire Works CompositionDocument4 pagesEco-Friendly Fire Works CompositionYog EshNo ratings yet

- Energy Epp1924 WildlifeAndAssetProtection EnglishDocument56 pagesEnergy Epp1924 WildlifeAndAssetProtection EnglishFalquian De EleniumNo ratings yet

- Getting Good Grades in School Is What Kids Are Supposed To Be Doing.Document6 pagesGetting Good Grades in School Is What Kids Are Supposed To Be Doing.The QUEENNo ratings yet

- Post Covid StrategyDocument12 pagesPost Covid Strategyadei667062No ratings yet

- Siasun Company IntroDocument34 pagesSiasun Company IntromoneeshveeraNo ratings yet

- MYP Unit Planner - MathDocument5 pagesMYP Unit Planner - MathMarija CvetkovicNo ratings yet

- San Beda University: Integrated Basic Education DepartmentDocument3 pagesSan Beda University: Integrated Basic Education DepartmentEmil SamaniegoNo ratings yet

- Aesa Vs PesaDocument30 pagesAesa Vs Pesakab11512100% (1)

- SuperboltDocument32 pagesSuperboltRajeev Chandel100% (1)

- Gerrard 1966Document13 pagesGerrard 1966AnandhuMANo ratings yet

- Word Formation ListDocument8 pagesWord Formation ListpaticiaNo ratings yet

- ReflectionDocument1 pageReflectionHeaven GuzmanNo ratings yet

- Hydrogen Sulfide and Mercaptan Sulfur in Liquid Hydrocarbons by Potentiometric TitrationDocument8 pagesHydrogen Sulfide and Mercaptan Sulfur in Liquid Hydrocarbons by Potentiometric TitrationINOPETRO DO BRASILNo ratings yet

- New Techniques of Predictions # 1Document5 pagesNew Techniques of Predictions # 1bhagathi nageswara raoNo ratings yet