Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Topical Quinolone vs. Antiseptic For Treating Chronic Suppurative Otitis Media: A Randomized Controlled Trial

Uploaded by

fatinfatharaniOriginal Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Topical Quinolone vs. Antiseptic For Treating Chronic Suppurative Otitis Media: A Randomized Controlled Trial

Uploaded by

fatinfatharaniCopyright:

Available Formats

Tropical Medicine and International Health

volume 10 no 2 pp 190–197 february 2005

Topical quinolone vs. antiseptic for treating chronic suppurative

otitis media: a randomized controlled trial

Carolyn Macfadyen1, Carrol Gamble2, Paul Garner1, Isaac Macharia3, Ian Mackenzie1, Peter Mugwe3, Herbert

Oburra3, Kennedy Otwombe1, Stephen Taylor2 and Paula Williamson2

1 International Health Research Group, Liverpool School of Tropical Medicine, Liverpool, UK

2 Centre for Medical Statistics and Health Evaluation, School of Health Sciences, University of Liverpool, Liverpool, UK

3 Section of Ear, Nose and Throat Diseases, University of Nairobi, Kenyatta National Hospital, Nairobi, Kenya

Summary objective To compare a topical quinolone antibiotic (ciprofloxacin) with a cheaper topical antiseptic

(boric acid) for treating chronic suppurative otitis media in children.

design Randomized controlled trial.

setting and participants A total of 427 children with chronic suppurative otitis media enrolled from

141 schools following screening of 39 841 schoolchildren in Kenya.

intervention Topical ciprofloxacin (n ¼ 216) or boric acid in alcohol (n ¼ 211); child-to-child

treatment twice daily for 2 weeks.

main outcome measures Resolution of discharge (at 2 weeks for primary outcome), healing of the

tympanic membrane, and change in hearing threshold from baseline, all at 2 and 4 weeks.

results At 2 weeks, discharge was resolved in 123 of 207 (59%) children given ciprofloxacin, and in

65 of 204 (32%) given boric acid (relative risk 1.86; 95% CI 1.48–2.35; P < 0.0001). This effect was

also significant at 4 weeks, and ciprofloxacin was associated with better hearing at both visits. No

difference with respect to tympanic membrane healing was detected. There were significantly fewer

adverse events of ear pain, irritation, and bleeding on mopping with ciprofloxacin than boric acid.

conclusions Ciprofloxacin performed better than boric acid and alcohol for treating chronic

suppurative otitis media in children in Kenya.

keywords randomized controlled trial, otitis media, suppurative, fluoroquinolones, antiseptics,

eardrops, instillation, drug, hearing impairment, developing countries

1998 (Acuin et al. 2004) concluded that topical treatment

Introduction

with antibiotics or antiseptics is more effective than

Chronic suppurative otitis media (CSOM) is a common systemic antibiotics, aural toilet alone, or no treatment at

cause of hearing impairment in low- and middle-income all; and topical quinolones were better than topical

countries [Berman 1995; World Health Organization non-quinolone antibiotics.

(WHO) 1998]. It is defined as chronically discharging ears Antiseptic drops, such as boric acid, are cheap and listed

(for at least the preceding 2 weeks) associated with in country guidelines of some low-income countries; e.g. in

persistent eardrum perforations. Data on prevalence of Papua New Guinea (Standard Treatment for Common

CSOM are uncommon, although one study estimated it at Illnesses of Children in Papua New Guinea 1993). The

1.1% in Kenyan schoolchildren (Hatcher et al. 1995). Cochrane Review identified three small studies (n ¼ 126)

Treatment aims to eradicate infection, prevent complica- comparing topical antiseptics with topical antibiotics, and

tions, heal the tympanic membrane, and improve hearing. did not demonstrate a difference for the outcome ‘wet ear’

Treatment options include dry mopping, ear wicking, (Acuin et al. 2004).

gentle syringing, or suctioning; systemic antibiotics; and Topical ciprofloxacin, a quinolone antibiotic, has

topical treatment with either antiseptics or antibiotics, recently become available, is licensed in the European

sometimes with steroids. A Cochrane Review published in Union, but is expensive: £5 per 5 ml bottle in the UK. The

190 ª 2005 Blackwell Publishing Ltd

Tropical Medicine and International Health volume 10 no 2 pp 190–197 february 2005

C. Macfadyen et al. Topical quinolone vs. antiseptic for chronic suppurative otitis media

Cochrane Review found quinolones superior to other experienced in ENT] screened children by class, inviting

topical antibiotics for CSOM; we conducted a randomized children with CSOM and their guardians to an induction

trial to evaluate this expensive but apparently effective visit, usually two school days later. At induction, a child’s

drug against topical antiseptics in Kenyan schoolchildren. legal guardian(s) provided signed informed consent before

assessments. After consent, but before randomization,

teams performed baseline and eligibility assessments.

Methods Demographic data and a medical history were taken.

Nurses established pure tone hearing threshold for air

Study site

conduction, in decibels at 500 Hz, 1 kHz, 2 kHz, 4 kHz

Rural primary schools in Kisumu District, West Kenya: we and 8 kHz, in a quiet location and by a standard technique

visited 165 of the 186 total. The District has the highest using portable Kamplex screening audiometers (AKM KS8

infant (116.7/1000) and under 5-year (194.7/1000) MP, battery operated); they recorded ambient noise levels

mortality in Kenya, and ear infection is common (Ministry using sound level meters. After audiometry, registrars and

of Planning and National Development 2004). clinical officers swabbed infected ears (for bacteriology and

sensitivity analysis in Kisumu), then examined both ears for

presence and degree of discharge, tympanic membrane

Participants

perforation, and any other otoscopic findings using Earlite

School children aged 5 years and older, with (a) purulent, Kite and Heine mini otoscopes.

aural discharge for 14 days or longer; (b) pus in the After completing all induction assessments, eligible

external canal on otoscopy; and (c) perforation of the children were allocated their sequential treatment pack;

tympanic membrane. We excluded children who had been clinical officers trained children and teachers and super-

treated for ear infection or received antibiotics for any vised the first dose. Every child was given a treatment

other disorder in the previous 2 weeks, or who had other record to complete to monitor treatment administration.

ear problems (pre-existing disease, complicated otitis

media, anatomical abnormalities) or allergy to study drugs.

Follow-up and outcomes

Children were seen at 2 and 4 weeks to collect data. Where

Interventions

children were absent, we revisited the school the next day.

Topical eardrops were given twice daily, after dry mop- All teams rotated schools for follow-up visits, to avoid

ping, for 10 consecutive school days (no treatment at them assessing children they had previously seen. Out-

weekends) with either ciprofloxacin eardrops (Ciloxan comes were (a) resolution of aural discharge; (b) healing of

0.3%; Alcon), or antiseptic eardrops (2% boric acid in tympanic membrane; and (c) change in hearing threshold.

45% alcohol). Older children were appointed as ‘ear The primary outcome was resolution of aural discharge at

monitors’ and trained to clean and treat the infected ears, 2 weeks. We also recorded adverse events.

under the supervision of trained teachers, as described in Children with persistent discharge at week 2 were

Smith et al. (1996). instructed to dry mop the ear(s) until week 4; those

discharging at week 4 were also instructed to dry mop, and

given a new bottle of eardrops and referred, with children

Randomization and masking

with persistent perforation or other ear pathology, to the

Children were randomized in a 1:1 ratio using computer- ENT surgeon in Kisumu. Children with other illnesses were

generated block randomization, stratified by school. Each referred to the nearby clinic or hospital. Any children

treatment pack contained two bottles of randomized referred during the study, remained in the study, and details

treatment and remained sealed until allocated to a child; of their referral and subsequent treatment were collected.

packs and the bottles were identical in appearance and

both treatments identical in colour and smell. Participants,

Sample size

carers, and outcome assessors remained blind to the

treatment allocated throughout the study. Rates of CSOM may be higher in Kisumu than the 1.1%

found other parts of Kenya, with its higher infant mortality

rates (http://www.cbs.go.ke) and higher rates of ear diseases

Field procedures

estimated by local medical staff and local surveys conducted

Four trained teams [each consisting of an Ear Nose and in 2000 (Educational Assessment and Resource Centre

Throat (ENT) registrar, clinical officer, and a nurse Kisumu, and New Nyanza Provincial General Hospital

ª 2005 Blackwell Publishing Ltd 191

Tropical Medicine and International Health volume 10 no 2 pp 190–197 february 2005

C. Macfadyen et al. Topical quinolone vs. antiseptic for chronic suppurative otitis media

(NNPGH) ENT Clinic, Kisumu, unpublished data; and ficance using the Pearson’s chi-square statistic. We used

Dr David Odeny, personal communication) – we therefore logistic regression for resolution at 2 weeks, to assess

used a higher estimate than that of Hatcher et al. 1995, but whether the age of the child, bilateral disease, length of

more conservative than the local Kisumu estimates, 15.1%, current CSOM episode and degree of perforation at

which were judged to be overestimated as they were based induction affected the relative treatment effect. Results are

on 900 students screened in three schools selected following expressed as odds ratio (OR).

high referral numbers to the education assessment and For audiometry, analysis of covariance (ancova) was

rehabilitation centre in Kisumu and rates may not be undertaken for hearing threshold, according to the study

limited to CSOM. Assuming a prevalence of 2%, and a total protocol. The WHO classifications were also used to

of 46,116 children in 186 schools in February 2002 (Office describe hearing impairment levels and Fisher’s exact test

of the District Education Officer 2002), we estimated that was used consider changes between levels.

920 children would be potentially eligible for the study. We report adverse events, notably local symptoms such

Assuming 750 agreed to participate and an estimated 50% as pain, irritation or bleeding (for example on mopping), as

resolution rate at 2 weeks in the antiseptic group (Acuin a secondary outcome.

et al. 2004), we calculated the study would have a power of

79% to detect the defined minimum clinically worthwhile

Ethical approval

absolute difference in resolution rates of 10%, at a two-

sided significance level of 5%. We obtained ethical approval from the Ministries of

An interim analysis was carried out for the first 200 Education and Health, the Provincial Ethical Review

study participants to check the estimated resolution rate for Committee, the Kenyatta National Hospital Institutional

the control group. The results indicated a resolution rate at Review Board in Kenya, and the Liverpool School of

2 weeks of 0.31 (95% CI 0.22–0.40) in the boric acid Tropical Medicine Research Ethics Committee in the UK.

group. Although the original estimate of 0.5 was excluded We received consent for the study from local education and

from the confidence interval, further sample size calcula- medical staff, from head teachers of the schools, who

tions assuming, in turn, the limits of this interval to be the informed students, and parents. We obtained informed

true proportion (i.e. 0.22 and 0.40 respectively), showed parental consent from eligible children’s legally acceptable

our original numbers would still be sufficient to provide representatives.

approximately 80% power to detect an absolute difference

of 10% in either of these scenarios. Thus our target sample

Results

size seemed compatible with the plausible estimates for the

control group resolution rate from our interim analysis. As We conducted the study in 165 of the 186 Kisumu rural

this calculation did not involve any comparison between primary schools in the May to August 2002 school term.

the two groups, the overall type 1 error rate is unaffected Twenty-one schools were not reached in the time

(Wittes et al. 1999). available. We reviewed 39 266 children at the screening

visit, plus an additional 575 children seen at the

induction visit. We found eligible children in 141

Statistical methods (analyses)

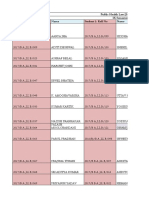

schools, and randomized a total of 427 children (Fig-

All analyses followed the intention-to-treat principle and ure 1). At the week 4 visit, three subjects in the boric

were conducted using SAS v8.2 2001. For bilateral disease, acid group and one in the ciprofloxacin group were seen

resolution and healing were considered to occur when both 1 week late. Seven children received some or all of the

ears were resolved or healed. We also carried out sensitivity wrong treatment because of switching with other par-

analyses defining bilateral resolution and healing to have ticipants’ bottles at allocation or during treatment

occurred when either or both ears resolved or healed. (Figure 1). All participants were analysed in the group

For audiometry readings, a single reading was taken they were initially randomized to. The groups were

from the diseased ear in unilateral cases, whilst the average comparable with respect to baseline data (Table 1).

across the two ears was calculated for bilateral disease.

Hearing threshold was recorded in dBHL and was

Outcomes

averaged across the 500 Hz, 1 kHz, 2 kHz and 4 kHz

frequency range. Resolution of aural discharge is higher with ciprofloxacin

For resolution and healing outcomes, ciprofloxacin was at 2 and 4 weeks (Table 2). Sensitivity analyses allowing

compared with boric acid using the relative risk (RR) and for varying outcome definition in bilateral disease did not

95% confidence interval. We assessed the statistical signi- significantly affect the results. The estimated treatment

192 ª 2005 Blackwell Publishing Ltd

Tropical Medicine and International Health volume 10 no 2 pp 190–197 february 2005

C. Macfadyen et al. Topical quinolone vs. antiseptic for chronic suppurative otitis media

Assessed for eligibility (n = 39 841*)

*39, 266 at screen + 575 at induction

Diagnosed with CSOM (n = 548*)

*489 at screen + 59 at induction

Children with CSOM not entered trial (n = 121)

• Invited but absent at induction (n = 19)

• Declined to give consent (n = 2)

• Did not meet inclusion criteria (n = 100)*

Dry perforation (n = 40)

Other diagnoses (n = 19)

Other medications (n = 21)

Too young (n = 14)

Other reasons (n = 22)

*16 children met two exclusion criteria

Randomised (n = 427)

Allocated to ciprofloxacin (n = 216) Allocated to boric acid (n = 211)

• Received cipro only (n = 212) • Received boric acid only (n = 208)

• Received cipro and boric (n = 3) • Received boric and cipro (n = 2)

• Received boric only (n = 1) • Received cipro only (n = 1)

Treat 10 schooldays (twice daily)

Child to child approach

Week 2 follow-up Week 2 follow-up

Attended (n = 207) Attended (n = 204)

Absent but not withdrawn (n = 3) Absent but not withdrawn (n = 2)

Absent and withdrawn at week 2 (n = 6) Absent and withdrawn at week 2 (n = 5)

• Lost to follow-up (n = 5) • Lost to follow-up (n = 5)

• Consent withdrawn (n = 1) • Consent withdrawn (n = 0)

Week 4 follow-up Week 4 follow-up

Attended: (n = 200) Attended (n = 202)

Withdrawn at week 2 (n = 6) Withdrawn at week 2 (n = 5)

Absent and withdrawn at week 4 (n = 10) Absent and withdrawn at week 4 (n = 4)

• Lost to follow -up (n = 10) • Lost to follow -up (n = 4)

Figure 1 Flow of participants through the study.

effect for resolution of discharge did not differ substantially expressed as OR, 95% CI were 3.13, 2.09–4.69 (unad-

after adjusting for age of the child, bilateral disease, length justed); 3.16, 2.04–4.93 (adjusted); and at 4 weeks were

of current CSOM episode and degree of perforation at 2.86, 1.91–4.27 (unadjusted); and 2.91, 1.88–4.50

induction, using logistic regression: at 2 weeks, the results, (adjusted).

ª 2005 Blackwell Publishing Ltd 193

Tropical Medicine and International Health volume 10 no 2 pp 190–197 february 2005

C. Macfadyen et al. Topical quinolone vs. antiseptic for chronic suppurative otitis media

Table 1 Baseline comparison

Antibiotic (Cipro) Antiseptic (Boric)

Characteristic N* N*

Total randomized 216 211

Age [mean (SD) (range)] 215 11.0 (3.15) 211 11.3 (3.15)

(5.1–19.0) (4.1–19.3)

Male [n (%N)] 216 128 (59) 211 123 (58)

Bilateral [n (%N)] 216 48 (22) 211 58 (27)

Weeks since start of current episode 196 8 (4–16) 194 8 (4–20)

[median (IQR)]

Start of current episode [n (%N)] 216 211

Ear ache 127 (59) 126 (60)

Cough or cold 75 (35) 75 (36)

Fever 61 (28) 54 (26)

Other 50 (23) 65 (31)

Not known 39 (18) 26 (12)

Any treatment ever received for ear 214 117 (55) 210 122 (58)

problems [n (%N)]

Audiometry [mean (SD) (range)] 212 41.0 (13.3) 209 42.3 (13.4)

(16.9–100) (11.3–100)

Degree of perforation [n (%N)]

Unilateral disease (diseased ear) 166 149

Small 28 (17) 22 (15)

Medium 70 (42) 61 (41)

Large 56 (34) 56 (38)

Total 11 (7) 10 (7)

Bilateral disease (both ears) 47 56

Both small 5 (11) 4 (7)

Both medium 14 (30) 18 (32)

Both large 11 (23) 17 (30)

Both total 5 (11) 2 (4)

One small, one medium 4 (9) 5 (9)

One small, one total 1 (2) 0

One medium, one large 5 (11) 8 (14)

One large, one total 2 (4) 2 (4)

* N is the number available or eligible for each characteristic.

Table 2 Resolution of aural discharge at 2 and 4 weeks

Antibiotic (cipro) Antiseptic (boric)à

[n/N (%)] [n/N (%)] RR (95% CI) P-value

Resolution at 2 weeks

1. Both ears resolve 123/207 (59.4) 65/204 (31.9) 1.86 (1.48–2.35) <0.0001

2. Either or both ears resolve 132/207 (63.8) 77/202 (38.1) 1.67 (1.36–2.05) <0.0001

Resolution at 4 weeks

1. Both ears resolve 130/196 (66.3) 90/198 (45.5) 1.46 (1.22–1.75) <0.0001

2. Either or both ears resolve 143/197 (72.6) 105/198 (53.0) 1.37 (1.17–1.60) <0.0001

Total randomized: N ¼ 216; à N ¼ 211.

Results include all children, treated for unilateral disease and for bilateral disease. Only the study ear has been considered for children

with unilateral disease in all analyses. Two approaches for handling children treated for bilateral disease: counted as success where

(1) both ears resolve, or (2) either or both ears resolve.

194 ª 2005 Blackwell Publishing Ltd

Tropical Medicine and International Health volume 10 no 2 pp 190–197 february 2005

C. Macfadyen et al. Topical quinolone vs. antiseptic for chronic suppurative otitis media

Table 3 Complete healing of tympanic

membrane at 2 and 4 weeks Antibiotic Antiseptic

(cipro) (boric)à

[n/N (%)] [n/N (%)] RR (95% CI) P-value

Healing at 2 weeks

1. Both ears healed 15/207 (7.2) 14/204 (6.9) 1.06 (0.52–2.13) 0.879

2. Either or both ears 19/207 (9.2) 18/202 (8.9) 1.03 (0.56–1.90) 0.925

healed

Healing at 4 weeks

1. Both ears healed 31/200 (15.5) 20/199 (10.1) 1.54 (0.91–2.61) 0.103

2. Either or both ears 38/200 (19.0) 28/199 (14.1) 1.35 (0.86–2.11) 0.185

healed

Total randomized: N ¼ 216; à N ¼ 211.

Results include all children, treated for unilateral disease and for bilateral disease. Only the

study ear has been considered for children with unilateral disease in all analyses. Two

approaches for handling children treated for bilateral disease: counted as success where (1)

both ears healed, or (2) either or both ears healed.

Healing of the tympanic membrane at 2 and 4 weeks

Discussion

showed no statistically significant difference between the

treatments (Table 3), although the estimated relative risk This study is the largest trial to date comparing an

suggests an effect in favour of ciprofloxacin at week 4. antiseptic with a quinolone antibiotic. Our results show

Sensitivity analyses did not significantly affect the results. better resolution and hearing threshold with a quinolone

Audiometry (controlling for baseline threshold with antibiotic over antiseptic. Since the Cochrane Review,

ancova) showed a trend to improved hearing for which found no trials of quinolones, there have been four

ciprofloxacin at 2 weeks and a significant effect at 4 weeks additional trials with mixed results: a study in Malawi

(Table 4). The conclusions did not change when suggested ofloxacin was better than 2% acetic acid in 25%

controlling for background noise as an additional spirit and 30% glycerine (for dry ears at 2 weeks, RR 6.13;

covariate. Tables 5 and 6 show the WHO classifications 95% CI, 2.59–14.53; n ¼ 53 ears) (van Hasselt 1997),

for the level and change in level of hearing impairment while another Malawi study (van Hasselt 1998, cited in

by treatment group. van Hasselt & van Kregten 2002), found a single dose of

For adverse events of ear pain, irritation, and bleeding ofloxacin 0.075% in hydroxypropyl methyl-cellulose 1.5%

on mopping, there was a significantly higher frequency in (HPMC) was better than one dose of povidone iodine 1%

the boric acid group (30/206, 14.6%) than in the ciprofl- in HPMC 1.5% (for dry ears after 1 week, RR 3.87, 95%

oxacin group (17/210, 8.1%), giving a difference (95% CI) CI 2.31–6.47, n ¼ 170). However, two trials did not find a

of 6.5% (0.3–12.7%) (Pearson’s chi-squared P-value significant effect in favour of topical quinolone antibiotics,

0.037). but numbers were small: a trial in Israel (Fradis et al. 1997)

compared ciprofloxacin hydrochloride eardrops with a

weak concentration of 1% Burow aluminium acetate

Table 4 Audiometry – average change in hearing from baseline at solution (results for dry ear 24 h after the end of 3 weeks

2 and 4 weeks (dB averaged over 500, 1000, 2000 and 4000 Hz) treatment, RR 2.01; 95% CI 0.76–5.36, n ¼ 36), while a

study in India (Jaya et al. 2003) compared 0.3% ciprofl-

dB mean Difference oxacin and 5% povidone iodine (results for participants

improvement (95% CI*)

with inactive ears at 2 weeks, RR 1.02; 95% CI, 0.82–

N (SD) (Cipro–Boric) P-value*

1.26; n ¼ 39 participants).

2 weeks: We took resolution of discharge as our primary out-

Cipro 201 4.32 (11.18) 2.17 (0.09–4.24) 0.0410 come, as this indicates clearing of the current infection, and

Boric 202 2.69 (11.67) minimizes the risk of progression of the disease. Ciprofl-

4 weeks

oxacin also had an impact on hearing, which underlines the

Cipro 196 5.42 (11.03) 3.43 (1.34–5.52) 0.0014

Boric 194 2.63 (12.18)

long-term purpose of treating this infection appropriately,

as deafness caused by CSOM may contribute to delayed

* Results from ancova controlling for baseline audio level. learning and behavioural disturbance (Klein 2001).

ª 2005 Blackwell Publishing Ltd 195

Tropical Medicine and International Health volume 10 no 2 pp 190–197 february 2005

C. Macfadyen et al. Topical quinolone vs. antiseptic for chronic suppurative otitis media

Table 5 Levels of hearing impairment at each visit (dB averaged over 500, 1000, 2000 and 4000 Hz)

Baseline Week 2 Week 4

Level of hearing

impairment [n (%)]* Boric Cipro Boric Cipro Boric Cipro

25 dB or better (no impairment) 14 (6.7) 17 (8.0) 24 (11.8) 38 (18.6) 30 (15.3) 39 (19.7)

26–40 dB (mild) 91 (43.5) 95 (44.8) 97 (47.6) 98 (48.0) 81 (41.3) 102 (51.5)

41–60 dB (moderate) 88 (42.1) 82 (38.7) 65 (31.8) 62 (30.4) 70 (35.7) 52 (26.3)

61–80 dB (severe) 14 (6.7) 16 (7.6) 16 (7.8) 4 (2.0) 11 (5.6) 4 (2.0)

81 dB or worse (profound) 2 (1.0) 2 (0.9) 2 (1.0) 2 (1.0) 4 (2.0) 1 (0.5)

Chi-square (d.f.), P-value 10.437 (4), 0.034 11.296 (4), 0.023

* Level is according to WHO classification of grades of hearing impairment.

Table 6 Change in level of hearing

Week 2 Week 4 impairment from baseline (dB averaged

Difference in WHO grade of

over 500, 1000, 2000 and 4000 Hz)

hearing impairment [n (%)]* Boric Cipro Boric Cipro

Worse (two-step increment) 3 (1.5) 1 (0.5) 4 (2.1) 0

Worse (one-step increment) 26 (12.9) 28 (13.9) 25 (12.9) 16 (8.2)

No change 116 (57.4) 98 (48.8) 109 (56.2) 108 (55.1)

Improved (one-step decrement) 53 (26.2) 62 (30.9) 49 (25.3) 59 (30.1)

Improved (two-step decrement) 4 (2.0) 11 (5.5) 7 (3.6) 11 (5.6)

Improved (three-step decrement) 0 1 (0.5) 0 2 (1.0)

Chi-square (d.f.), Fisher’s exact 7.557 (5), 0.161 9.785 (5), 0.078

P-value

* An improvement in the level of hearing impairment means there was a decrease in the

average hearing threshold. WHO grades are as presented in Table 5.

Hearing in the diseased ear is usually significantly impaired et al. 2003; Acuin et al. 2004; Acuin 2004). No formal

compared with the uninfected ear, and children with analyses were performed on any other safety findings in our

unilateral disease, as for bilateral impairment, are likely to trial, which was not designed or powered to assess more

have significant educational and social problems (Ballan- specific safety questions, as numbers were small and

tyne & Martin 1984; Brookhouser et al. 1991). Longer- specific adverse event information may not have been

term follow-up would be needed to assess the impact of systematically detected because of the open-ended nature

treatment on hearing in the long-term and on behaviour of the questioning.

and learning. Although ciprofloxacin remains more expensive than

Smith et al. (1996) found that healing of the tympanic antiseptics and other non-quinolone antibiotics (approxi-

membrane was an important factor for improving hearing. mately 12 times the price of boric acid in Kenya), the

While we found few cases of complete healing with either difference varies between countries. It is likely that the cost

treatment, there was a trend towards a small benefit of of quinolone eardrops will fall with time, particularly if

ciprofloxacin by week 4; the wide confidence intervals imply generic preparations are available. In addition to direct

a potentially clinically important benefit cannot be ruled out purchase costs, other treatment-related costs and practi-

for tympanic membrane healing with ciprofloxacin. calities for treatment preparation, transport and storage

We followed up students for just 4 weeks, because of must also be considered when comparing treatments.

logistic and financial constraints. However, longer follow-

up would be needed to assess whether the differences found

Conclusions

here (for resolution, healing and hearing) remain over time.

The higher number of children reporting adverse events In children with chronic suppurative otitis media, we have

related to ear pain, irritation, and bleeding on mopping found topical ciprofloxacin ear drops to be more effective

with boric acid in alcohol is probably because the alcohol than boric acid at 2 and 4 weeks, for both resolution of

may sting. This finding is in line with other studies to date, discharge and improvement in hearing. We also found

which have supported a good safety profile for quinolone significantly fewer adverse events of ear pain, irritation, and

eardrops (Brownlee et al. 1992; Morpeth et al. 2001; Jaya bleeding on mopping, with ciprofloxacin than boric acid.

196 ª 2005 Blackwell Publishing Ltd

Tropical Medicine and International Health volume 10 no 2 pp 190–197 february 2005

C. Macfadyen et al. Topical quinolone vs. antiseptic for chronic suppurative otitis media

Acknowledgements Development, Kenya. http://www.cbs.go.ke (last accessed 9

February 2004).

We thank Dr AW Smith, World Health Organization, for Morpeth JF, Bent JP & Watson T (2001) A comparison of cor-

his advice; Dr David Odeny, consultant ENT surgeon, for tisporin and ciprofloxacin otic drops as prophylaxis against

his help in Kisumu; and Zedekia Owira, Inspector for post-tympanostomy otorrea. International Journal of Pediatric

Schools. The study was funded by a Project Grant from Otorhinolaryngology 61, 99–104.

The Wellcome Trust (UK Registered Charity Number Office of the District Education Officer (2002) List of School

210183; Grant reference number: 056756/Z/99/Z). Alcon Enrolment in February 2002. Provided by Zedekia Owira,

(Denmark and Belgium) provided the Ciloxan supplies. Inspector of Schools for Kisumu District Education Office,

Kisumu District.

SAS v8.2 (2001) SAS Institute Inc. SAS Institute Inc, Cary, NC,

References USA.

Smith AW, Hatcher J, Mackenzie IJ et al. (1996) Randomised

Acuin J (2004) Chronic suppurative otitis media. In Clinical Evi- controlled trial of treatment of chronic suppurative otitis media

dence 12, 710–729. in Kenyan schoolchildren. Lancet 349, 1133–1138.

Acuin J, Smith A & Mackenzie I (2004) Interventions for chronic Standard Treatment for Common Illnesses of Children in Papua

suppurative otitis media (Cochrane Review). In: The Cochrane New Guinea (1993) A Manual For Nurses, Health Extension

Library, Issue 2, 2004. John Wiley & Sons Ltd, Chichester, UK. Officers and Doctors. G. Dadi, Acting Government Printer, Port

Ballantyne J & Martin JAM (1984) Deafness, 4th edn. Churchill Moresby 1988. 6th Edition, Port Moresby 1993.

Livingstone, London, pp. 222–224. van Hasselt P (1997) Treatment of chronic suppurative otitis media

Berman S (1995) Otitis media in developing countries. Pediatrics with suction cleaning and antiseptic versus antibiotic ear drops.

96, 126–131. Internal report of Christian Blind Mission International.

Brookhouser PE, Worthington DW & Kelly WJ (1991) Unilateral Bensheim, Germany. Also in: van Hasselt & van Kregten 2002.

hearing loss in children. Laryngoscope 101 1264–1272. van Hasselt P (1998) Management of chronic suppurative otitis

Brownlee RE, Hulka GF, Prazma J & Pillsbury HC (1992) media in developing countries. In: Proceedings of the 2nd

Ciprofloxacin. Use as a topical otic preparation. Arch Otolar- European Congress on Tropical Medicine, Liverpool. 1998:57.

yngol Head Neck Surg 118, 392–396. Cited in Van Hasselt and Van Kregten 2002.

Fradis M, Brodsky A, Ben David J, Srugo I, Larboni J & Podoshin van Hasselt P & van Kregten E (2002) Treatment of chronic

L (1997) Chronic otitis media treated topically with cipro- suppurative otitis media with ofloxacin in hydroxypropyl

floxacin or tobramycin. Archives of Otolaryngology Head and methylcellulose ear drops: a clinical/bacteriological study in a

Neck Surgery 123, 1057–1060. rural area of Malawi. International Journal of Pediatric Otor-

Hatcher J, Smith A, Mackenzie I et al. (1995) A prevalence study hinolaryngology 63, 49–56.

of ear problems in school children in Kiambu district, Kenya, Wittes J, Schabenberger O, Zucker D, Brittain E & Proschan M

May 1992. International Journal of Pediatric Otorhinolaryng- (1999) Internal pilot studies I: type I error rate of the naı̈ve t-test.

ology 33, 197–205. Statistics in Medicine 18, 3481–3491.

Jaya C, Job A, Mathai E & Antonisamy B (2003) Evaluation of World Health Organization (1998) Prevention of hearing

topical povidone-iodine in chronic suppurative otitis media. impairment from chronic otitis media. Report of a WHO/CIBA

Archives of Otolaryngology Head and Neck Surgery 129, 1098– Foundation Workshop, held at The CIBA Foundation. World

1100. Health Organization, London, U.K. 19–21 November 1996.

Klein JO (2001) The burden of otitis media. Vaccine 19, S2–S8. [WHO/PDH/98.4 http://www.who.int/pbd/deafness/en/

Ministry of Planning and National Development (2004) The chronic_otitis_media.pdf]

Central Bureau of Statistics. Ministry of Planning and National

Authors

Carolyn Macfadyen (corresponding author), Paul Garner, Ian Mackenzie, Kennedy Otwombe, International Health Research Group,

Liverpool School of Tropical Medicine, Pembroke Place, Liverpool L3 5QA, UK. Fax: +44 (0) 151 705 3364; Tel: +44 (0) 151 708

9393, E-mail: cmacfadyenuk@yahoo.co.uk, pgarner@liverpool.ac.uk, macken34@liverpool.ac.uk, notwombe@yahoo.com

Carrol Gamble, Stephen Taylor, Paula Williamson, Centre for Medical Statistics and Health Evaluation, School of Health Sciences,

Shelley’s Cottage, Brownlow Street, University of Liverpool, Liverpool L69 3GS. Tel.: 44 (0) 151 794 5121; Fax: +44 (0) 151 794 5130;

E-mail: c.gamble@liverpool.ac.uk, s.taylor01@liverpool.ac.uk, p.r.williamson@liverpool.ac.uk

Isaac Macharia, Peter Mugwe, Herbert Oburra, Section of Ear, Nose and Throat Diseases, Department of Surgery, University of

Nairobi, Kenyatta National Hospital, Nairobi, Kenya. E-mail: machariaim@wananchi.com, mugwe@wananchi.com, kansel@

insightkenya.com

ª 2005 Blackwell Publishing Ltd 197

You might also like

- The Role of Polycaprolactone in Asian RhinoplastyDocument4 pagesThe Role of Polycaprolactone in Asian RhinoplastyfatinfatharaniNo ratings yet

- Benefit From Tonsillectomy in Adult Patients With Chronic TonsillitisDocument4 pagesBenefit From Tonsillectomy in Adult Patients With Chronic TonsillitisfatinfatharaniNo ratings yet

- Original Research SyahrijuitaDocument5 pagesOriginal Research SyahrijuitafatinfatharaniNo ratings yet

- Timpanogram Pada Anak Usia 1-5 Tahun: PendahuluanDocument7 pagesTimpanogram Pada Anak Usia 1-5 Tahun: PendahuluanNinikNo ratings yet

- The Role of Polycaprolactone in Asian RhinoplastyDocument4 pagesThe Role of Polycaprolactone in Asian RhinoplastyfatinfatharaniNo ratings yet

- The Role of Polycaprolactone in Asian RhinoplastyDocument4 pagesThe Role of Polycaprolactone in Asian RhinoplastyfatinfatharaniNo ratings yet

- Treatment For Eosinophilic Esophagitis: ReviewDocument6 pagesTreatment For Eosinophilic Esophagitis: ReviewfatinfatharaniNo ratings yet

- Jurnal Baru 3Document6 pagesJurnal Baru 3Amalia GrahaniNo ratings yet

- Comparison of Endoscopic Cartilage Myringoplasty in Dry and Wet Ears With Chronic Suppurative Otitis MediaDocument6 pagesComparison of Endoscopic Cartilage Myringoplasty in Dry and Wet Ears With Chronic Suppurative Otitis MediafatinfatharaniNo ratings yet

- Challenge and Update EEDocument7 pagesChallenge and Update EEfatinfatharaniNo ratings yet

- Proceedings BookDocument12 pagesProceedings BookfatinfatharaniNo ratings yet

- Slide Lapkas ThalassemiaDocument52 pagesSlide Lapkas ThalassemiafatinfatharaniNo ratings yet

- Word HNPDocument14 pagesWord HNPALan ButukNo ratings yet

- Gambaran Hasil Pemeriksaan Laringoskopi Fiber Optik Pada Pasien Rawat Inap Di RSUP. Prof. Dr. R. D. Kandou Periode 2014 - 2017Document5 pagesGambaran Hasil Pemeriksaan Laringoskopi Fiber Optik Pada Pasien Rawat Inap Di RSUP. Prof. Dr. R. D. Kandou Periode 2014 - 2017Syaf emaNo ratings yet

- CochleaDocument4 pagesCochleafatinfatharaniNo ratings yet

- Journal Article ReviewDocument3 pagesJournal Article ReviewdinhchungxdNo ratings yet

- CWLDocument3 pagesCWLfatinfatharaniNo ratings yet

- SPVDocument1 pageSPVfatinfatharaniNo ratings yet

- Pricelist Friggia (Small)Document3 pagesPricelist Friggia (Small)fatinfatharaniNo ratings yet

- CochleaDocument4 pagesCochleafatinfatharaniNo ratings yet

- Slide Lapkas ThalassemiaDocument52 pagesSlide Lapkas ThalassemiafatinfatharaniNo ratings yet

- PDF 0214 0214ACP KruseDocument9 pagesPDF 0214 0214ACP KrusefatinfatharaniNo ratings yet

- Lapkas Atin3Document23 pagesLapkas Atin3fatinfatharaniNo ratings yet

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeFrom EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (5794)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeFrom EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (537)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)From EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Rating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (98)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceFrom EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (895)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersFrom EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (344)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingFrom EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (399)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceFrom EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (588)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerFrom EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (271)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaFrom EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (266)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItFrom EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (838)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryFrom EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (231)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealFrom EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (73)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureFrom EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (474)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnFrom EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (234)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyFrom EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (2259)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaFrom EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (45)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreFrom EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (1090)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)From EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Rating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (120)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesFrom EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (821)

- Hauber 2019Document10 pagesHauber 2019Laura HdaNo ratings yet

- Module 1 DiversityDocument33 pagesModule 1 DiversityCatherine A. PerezNo ratings yet

- Topic ListDocument6 pagesTopic ListEdwinNo ratings yet

- Pro-Oxidant Strategies - Cancer Treatments ResearchDocument71 pagesPro-Oxidant Strategies - Cancer Treatments ResearchSpore FluxNo ratings yet

- Pharmacy Job InterviewQuestionsDocument4 pagesPharmacy Job InterviewQuestionsRadha MandapalliNo ratings yet

- The Real ThesisDocument35 pagesThe Real ThesisDanielle Cezarra FabellaNo ratings yet

- Pecial Eature: Transitions in Pharmacy Practice, Part 3: Effecting Change-The Three-Ring CircusDocument7 pagesPecial Eature: Transitions in Pharmacy Practice, Part 3: Effecting Change-The Three-Ring CircusSean BlackmerNo ratings yet

- HUMSS - Disciplines and Ideas in The Social Sciences CGDocument1 pageHUMSS - Disciplines and Ideas in The Social Sciences CGDan LiwanagNo ratings yet

- The Diagram Shows How A Company Called HB Office RDocument1 pageThe Diagram Shows How A Company Called HB Office RbugakNo ratings yet

- Set C QP Eng Xii 23-24Document11 pagesSet C QP Eng Xii 23-24mafiajack21No ratings yet

- Career Comparison ChartDocument2 pagesCareer Comparison Chartapi-255605088No ratings yet

- Chalmers Stressful Life Events: Their Past and PresentDocument15 pagesChalmers Stressful Life Events: Their Past and PresentAna Rivera CastañonNo ratings yet

- KEMH Guidelines On Cardiac Disease in PregnancyDocument7 pagesKEMH Guidelines On Cardiac Disease in PregnancyAyesha RazaNo ratings yet

- Job Chart of Physical Education Teachers - AP GOVTDocument3 pagesJob Chart of Physical Education Teachers - AP GOVTRamachandra Rao100% (1)

- Janssen Pharmaceutica NVDocument63 pagesJanssen Pharmaceutica NVRj jNo ratings yet

- Comm 806 NoteDocument201 pagesComm 806 Notelyndaignatius45No ratings yet

- Types of PovertyDocument6 pagesTypes of PovertyJacobNo ratings yet

- Arterial Events, Venous Thromboembolism, Thrombocytopenia, and Bleeding After Vaccination With Oxford-Astrazeneca Chadox1-S in Denmark and Norway: Population Based Cohort StudyDocument10 pagesArterial Events, Venous Thromboembolism, Thrombocytopenia, and Bleeding After Vaccination With Oxford-Astrazeneca Chadox1-S in Denmark and Norway: Population Based Cohort StudyFemale calmNo ratings yet

- Snake Bite SOPDocument5 pagesSnake Bite SOPRaza Muhammad SoomroNo ratings yet

- Disorder and Diseases of Digestive SystemDocument8 pagesDisorder and Diseases of Digestive SystemCristina AnganganNo ratings yet

- Target Heart Rate Lesson PlanDocument4 pagesTarget Heart Rate Lesson PlanEryn YeskeNo ratings yet

- Extend XT - Folleto ComercialDocument6 pagesExtend XT - Folleto ComercialMuhamadZuhdiAlWaliNo ratings yet

- Food StampsDocument80 pagesFood StampsAnvitaRamachandranNo ratings yet

- Burnout Among Secondary School Teachers in Malaysia Sabah: Dr. Balan RathakrishnanDocument8 pagesBurnout Among Secondary School Teachers in Malaysia Sabah: Dr. Balan Rathakrishnanxll21No ratings yet

- Innovations in NursingDocument14 pagesInnovations in NursingDelphy Varghese100% (1)

- Sensus Harian TGL 05 Maret 2022........Document104 pagesSensus Harian TGL 05 Maret 2022........Ruhut Putra SinuratNo ratings yet

- Rachel Tucker Resume 2020Document1 pageRachel Tucker Resume 2020api-489845523No ratings yet

- Requirements Specification For Patient Level Information and Costing Systems (PLICS) Mandatory Collections Continued ImplementationDocument40 pagesRequirements Specification For Patient Level Information and Costing Systems (PLICS) Mandatory Collections Continued ImplementationAbidi HichemNo ratings yet

- Blood Testing For DioxinsDocument2 pagesBlood Testing For DioxinstedmozbiNo ratings yet

- الصحة PDFDocument17 pagesالصحة PDFGamal MansourNo ratings yet