Professional Documents

Culture Documents

The Wheelair III-A: Yesterday's Wings

Uploaded by

sandyOriginal Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

The Wheelair III-A: Yesterday's Wings

Uploaded by

sandyCopyright:

Available Formats

Yesterday's Wings

The Wheelair III-A

by PETER M. BOWERS / AOPA 54408

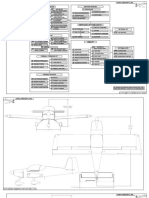

WHEELAIR Ill-A

Specifications and Performance

Span 37 ft 0 in

Length 26 ft 61/2 in

Wing area 180 sq ft

Powerplant Lycoming 0·435·AP,

190 hp @ 2,550 rpm

Empty weight 1,350 Ib

•• Aviation's archives are liberally Gross weight 2,500 Ib

much more angular body than that

sprinkled with examples of promising High speed 140 mph shown in the promotional literature. Ex-

new general aviation designs that for Cruise speed 125 mph cept for the nose cone, all the fuselage

various reasons did not make it past the Landing speed 55 mph skin was flat-wrap.

prototype stage. Only in rare cases have Initial climb 760 fpm The advertising bore down heavily on

single new models developed by new Service ceiling 11,500 ft the automobilelike atmosphere of the

and small firms become significant items Range 600 mi on 50 gal roomy cabin, where the throwover con-

in the marketplace. trol wheel was actually one from a

One of the long-forgotten one-and- Mercury automobile. Emphasis was also

onlies that had better-than-average po- placed on the easy, two-control flying

tential was the Wheelair 111-A of the plant in Tacoma, Wash. that made piloting no more tiring than

early post-World War II years. The airplane, the Wheelair ll1-A (not driving a car. It was a two-control plane.

Back in 1944, Popular Science maga- roman numeral III, as sometimes mis- Like the Ercoupe, it eliminated the rud-

zine held a paper design contest for printed) was unconventional only in der pedals but did not tie the rudder

what was hoped would be the postwar that it revived the tail-boom pusher con- (or rudders in this case) into the aileron

family airplane. The contest was won cept last seen in general aviation on the control. There were no rudders; the two

by Donald J. Wheeler, an aeronautical famous Stearman-Hammond Y of the fins at the ends of the tubular booms

engineer then working for Boeing in mid-1930s. Particularly in plan view, were fixed. The need for rudder control

Seattle. On the strength of his win, the Wheel air looked like the Stearman- was eliminated by "new design" ailerons

Wheeler left Boeing, secured $500,000 Hammond stretched to make a four- that could handle the turning job all

in backing, and formed a new company seater. Wheeler's tooling was no match alone.

to develop and market his design. This for Stearman-Hammond's, however, and The powerplant for the all-metal

was Puget Pacific Planes, Inc., with a the prototype 111-A proved to have II Wheelair was to have been the 125-hp

~"

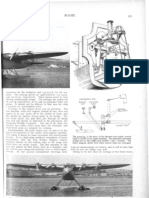

As a "pod·and-boom pusher," the Whee/air l11·A naturally invites comparison with the famous Stearman-Hammond Y of the 1930s. Tricycle landing

gear was an innovation when the Y appeared. hut was rapidly becoming the standard when the 111-A was introduced.

OCTOBER 1975 I THE AOPA PILOT 73

WH££LAIR 11l·A continued Completed in 1947, the Wheelair

encountered the usual problems of pod-

and-boom pushers: engine overheating

Lycoming 0-290, but the prototype and loss of propeller efficiency through

ended up with a 190-hp Lycoming 0-435. blanketing. In the latter case, the 52-

This was mounted high in the rear of inch-wide cabin, praised for its roomy

the pod and drew cooling air through a comfort in the promotional literature,

single scoop on top of the cabin. was a definite handicap.

While the Wheel air did have its

shortcomings, it was not a "dog" and

The four-place cabin of the Whee/air was modeled like the interior of the family actually came quite close to some of the

sedan and was intended to be one of the design's strongest selling points_ preflight claims. With a little more de-

The seats and even the control wheel were automotive items. tail refinement, it might have been able

to make a place for itself, even though

its performance was well below such

four-place contemporaries as the new

Beech Bonanza and North American

Navion, and even the strut-braced, fixed-

gear Stinson Station Wagon. Unfortu-

nately, the company ran out of money

before the test and certification program

could be completed. Wheeler had left

earlier, and his design never did get

certificated or into production.

The prototype languished on Seattle's

Boeing Field for a couple of years and

then vanished into the same oblivion

shared by many other interesting but

unsuccessful designs. Whether it was

scrapped or stored in someone's barn is

not known. If it still exists, the son of

one of the original backers would like

to restore it as a unique and flyable

antique. It is hoped that an AOPA mem-

ber in the Northwest might have the

answer. 0

You might also like

- Piper 235Document9 pagesPiper 235cjtrybiecNo ratings yet

- Koala Specs and PicsDocument4 pagesKoala Specs and PicsstoliNo ratings yet

- Hawker 900XP Review Flying 2009Document5 pagesHawker 900XP Review Flying 2009albucur100% (1)

- Rolls-Royce Griffon II VIDocument3 pagesRolls-Royce Griffon II VIReyhan Fanny PratamaNo ratings yet

- British Aerospace Hawk: Armed Light Attack and Multi-Combat Fighter TrainerFrom EverandBritish Aerospace Hawk: Armed Light Attack and Multi-Combat Fighter TrainerNo ratings yet

- Heath Parasol: Under The Heath Umbrella-Airplanes and Hi-Fi KitsDocument3 pagesHeath Parasol: Under The Heath Umbrella-Airplanes and Hi-Fi KitsJohn McGillisNo ratings yet

- Big Deal From BEDEDocument1 pageBig Deal From BEDEseafire47No ratings yet

- Flight. 453: OCTOBER 3T, 1935Document1 pageFlight. 453: OCTOBER 3T, 1935seafire47No ratings yet

- GLIDER AssignmentDocument5 pagesGLIDER AssignmentArief SambestNo ratings yet

- Aw AlbermarleDocument7 pagesAw Albermarlepachdgdhanguro100% (4)

- Comanche Training ManualDocument218 pagesComanche Training ManualLuis Amaya100% (4)

- Wallis Pag1 1966 - 0899Document1 pageWallis Pag1 1966 - 0899Mariela TisseraNo ratings yet

- Sport & Experimental Aircraft Aircraft List S e Q U o I A F A L C oDocument3 pagesSport & Experimental Aircraft Aircraft List S e Q U o I A F A L C oPredrag PavlovićNo ratings yet

- King Air 350ER: Longer-Legged Model Is Flexible and CapableDocument2 pagesKing Air 350ER: Longer-Legged Model Is Flexible and CapableStefan DolapchievNo ratings yet

- 1994 Ruschmeyer R90 230 RGDocument6 pages1994 Ruschmeyer R90 230 RGsandyNo ratings yet

- Full Download Original PDF Macroeconomics 7th Edition by R Glenn Hubbard PDFDocument22 pagesFull Download Original PDF Macroeconomics 7th Edition by R Glenn Hubbard PDFjustine.karcher887100% (35)

- Rearwin Cloudster Monoplane (1940)Document4 pagesRearwin Cloudster Monoplane (1940)CAP History Library100% (1)

- Napier SabreDocument3 pagesNapier SabrePekka PuurtajaNo ratings yet

- The Little Engine That CouldnDocument8 pagesThe Little Engine That CouldnMorgen Gump100% (1)

- Piper PA-28 WarriorDocument8 pagesPiper PA-28 Warriorvidc870% (1)

- Flying the Light Retractables: A guided tour through the most popular complex single-engine airplanesFrom EverandFlying the Light Retractables: A guided tour through the most popular complex single-engine airplanesNo ratings yet

- DCS AV-8B Harrier Guide PDFDocument258 pagesDCS AV-8B Harrier Guide PDFtinozaraNo ratings yet

- Cherokee Archerii: All Rights Reserved Carenado Company 2002Document4 pagesCherokee Archerii: All Rights Reserved Carenado Company 2002Diego Beirão100% (1)

- Falco - F.8L CAFE Article PDFDocument9 pagesFalco - F.8L CAFE Article PDFPredrag PavlovićNo ratings yet

- DCS AV-8B Harrier GuideDocument277 pagesDCS AV-8B Harrier GuideKusunoki MasashigeNo ratings yet

- DCS AV-8B Harrier GuideDocument278 pagesDCS AV-8B Harrier GuideDarksniped flying madnessNo ratings yet

- DCS AV-8B Harrier GuideDocument278 pagesDCS AV-8B Harrier Guideonukvedat7219No ratings yet

- 670 Flight.: JUNE 25, 1936Document1 page670 Flight.: JUNE 25, 1936seafire47No ratings yet

- 31 Practical Ultralight Aircraft You Can Build PDF Free 2Document28 pages31 Practical Ultralight Aircraft You Can Build PDF Free 2dososaNo ratings yet

- Short Scion SeniorDocument1 pageShort Scion Seniorseafire47No ratings yet

- Brantly Helicopter ReportDocument4 pagesBrantly Helicopter Reportjorge paezNo ratings yet

- Stinson L-5 SentinelDocument19 pagesStinson L-5 SentinelNiki0% (1)

- SEPTEMBER 23, 1920: The Fuselage Is A Rectangular Girder of Ash Members, CoveredDocument1 pageSEPTEMBER 23, 1920: The Fuselage Is A Rectangular Girder of Ash Members, CoveredMark Evan SalutinNo ratings yet

- Rolls-Royce Eagle IX Engine - Flight - March 8th 1923Document1 pageRolls-Royce Eagle IX Engine - Flight - March 8th 1923Floyd PriceNo ratings yet

- Pitts S2B Aircraft Paper ModelDocument6 pagesPitts S2B Aircraft Paper ModelRicardo UribevNo ratings yet

- DCS AV-8B Harrier Guide PDFDocument185 pagesDCS AV-8B Harrier Guide PDFPatrick Adams50% (2)

- A2A Cherokee180 Pilot's ManualDocument104 pagesA2A Cherokee180 Pilot's ManualCapi MarketingNo ratings yet

- 100 Years Aircraft EngineDocument11 pages100 Years Aircraft Enginemkhairuladha100% (1)

- WT9 DynamicDocument5 pagesWT9 Dynamicalbix58No ratings yet

- Rolls Royce DerwentDocument4 pagesRolls Royce DerwentarkazzNo ratings yet

- 10 Airstream Panamerica BrochureDocument6 pages10 Airstream Panamerica BrochureRaleigh HolmesNo ratings yet

- Model Airplane News 1954-08Document61 pagesModel Airplane News 1954-08Thomas KirschNo ratings yet

- Angels and Airspeed - P-39D in CombatDocument4 pagesAngels and Airspeed - P-39D in CombatmitchtanzNo ratings yet

- Eaa Flight Reports - Aeronca ChampDocument4 pagesEaa Flight Reports - Aeronca ChampIdiosocraticNo ratings yet

- The Pegasus Story: ConceptionDocument6 pagesThe Pegasus Story: ConceptionmichaelguzziNo ratings yet

- I.Ae. 22 DL: Technical Description: A Monoplane Build of Wood, Tandem TandemDocument8 pagesI.Ae. 22 DL: Technical Description: A Monoplane Build of Wood, Tandem TandemMartin PataNo ratings yet

- Hawker 900XP Review BJT 2009 BriefDocument3 pagesHawker 900XP Review BJT 2009 BriefalbucurNo ratings yet

- Tanega Z1A APLABDocument2 pagesTanega Z1A APLABAnonamanNo ratings yet

- FalcoDocument6 pagesFalcoPredrag Pavlović100% (1)

- Focke-Wulf FW 190Document30 pagesFocke-Wulf FW 190Eric T Holmes100% (2)

- Wings Across Canada: An Illustrated History of Canadian AviationFrom EverandWings Across Canada: An Illustrated History of Canadian AviationRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (1)

- Antonov, An - 225 PDFDocument2 pagesAntonov, An - 225 PDFDdwengNo ratings yet

- Beech 1900D - Flight TestDocument6 pagesBeech 1900D - Flight Testalbucur100% (1)

- 7 How To Build The Super-Parasol Part IDocument6 pages7 How To Build The Super-Parasol Part IkroitorNo ratings yet

- Model Builder August - 1989Document111 pagesModel Builder August - 1989Paolo Di Marco100% (1)

- Ski Jump Info CVF & Others Testing 28 May 2014 pp163Document163 pagesSki Jump Info CVF & Others Testing 28 May 2014 pp163SpazSinbad2100% (1)

- Flight TestDocument36 pagesFlight TestJUAN MALDONADO100% (2)

- FalcoDocument9 pagesFalcoPredrag PavlovićNo ratings yet

- Welcome To The New Piper M-Class: in This IssueDocument12 pagesWelcome To The New Piper M-Class: in This IssuesandyNo ratings yet

- Site Controller Iii Board Set Installation Instructions: Expansion Port Screws (Steps 3 and 6)Document1 pageSite Controller Iii Board Set Installation Instructions: Expansion Port Screws (Steps 3 and 6)sarge18No ratings yet

- Product Catalog: Cleveland Wheels & BrakesDocument296 pagesProduct Catalog: Cleveland Wheels & BrakesАлександр ГладкийNo ratings yet

- SB 1103BDocument5 pagesSB 1103BsandyNo ratings yet

- Piper's M600 Personal Turboprop: For The Pilots of Owner-Flown, Cabin-Class AircraftDocument36 pagesPiper's M600 Personal Turboprop: For The Pilots of Owner-Flown, Cabin-Class AircraftsandyNo ratings yet

- Service Bulletin: Alternator Model ALU-6539-4 Installation of Missing SpacerDocument9 pagesService Bulletin: Alternator Model ALU-6539-4 Installation of Missing SpacersandyNo ratings yet

- M600 SLS Halo BrochureDocument2 pagesM600 SLS Halo BrochuresandyNo ratings yet

- Parts Manual: Topkat Fuel Management SystemDocument20 pagesParts Manual: Topkat Fuel Management SystemsandyNo ratings yet

- Current Online CatalogDocument376 pagesCurrent Online CatalogsandyNo ratings yet

- 20110610Document6 pages20110610sandyNo ratings yet

- Service Bulletin: Alternator Model ALU-6539-4 Installation of Missing SpacerDocument9 pagesService Bulletin: Alternator Model ALU-6539-4 Installation of Missing SpacersandyNo ratings yet

- Piper Seminole PA44-180 Checklist: Nice AirDocument4 pagesPiper Seminole PA44-180 Checklist: Nice AirDoĞuŞ SaracNo ratings yet

- PR46BT: 115838449 Rev. A 2016-05-02Document41 pagesPR46BT: 115838449 Rev. A 2016-05-02sandyNo ratings yet

- The New Standard in Aviation: Safety Standards That Exceed Your Highest StandardsDocument2 pagesThe New Standard in Aviation: Safety Standards That Exceed Your Highest StandardssandyNo ratings yet

- ATP CatalogDocument158 pagesATP Catalogsandy100% (1)

- 2019 Specification Book: Cabin Class - Single-Engine - Pressurized TurbopropDocument5 pages2019 Specification Book: Cabin Class - Single-Engine - Pressurized Turbopropsandy100% (1)

- Vans Aircraft Building InstructionDocument6 pagesVans Aircraft Building Instructionsandy100% (1)

- Airworthiness Bulletin: AWB Issue: Date: 1. ApplicabilityDocument2 pagesAirworthiness Bulletin: AWB Issue: Date: 1. ApplicabilitysandyNo ratings yet

- C130 HérculesDocument21 pagesC130 HérculesJesus Ocaña Calderón75% (4)

- Supplemental Type Aertificate: Bepartment of Transportation - Hederal Adiation AdministrationDocument26 pagesSupplemental Type Aertificate: Bepartment of Transportation - Hederal Adiation AdministrationsandyNo ratings yet

- KR 87 PDFDocument45 pagesKR 87 PDFFilip SkultetyNo ratings yet

- Service Letter: Single EngineDocument10 pagesService Letter: Single EnginesandyNo ratings yet

- 230 203-Pa24 Inspection Report-Rev 20090401Document5 pages230 203-Pa24 Inspection Report-Rev 20090401sandyNo ratings yet

- 206L4 Spec Book 22013-WebDocument45 pages206L4 Spec Book 22013-WebSamuel LimaNo ratings yet

- Cessna ConquestDocument18 pagesCessna ConquestsandyNo ratings yet

- Chuck Guide Il 2 Cliffs of Dover He111Document91 pagesChuck Guide Il 2 Cliffs of Dover He111sandyNo ratings yet

- VANTAGE TruckALL and VanGO Series Operation and Service ManualDocument209 pagesVANTAGE TruckALL and VanGO Series Operation and Service ManualsandyNo ratings yet

- Inflight Guide CJ4-V2.0Document30 pagesInflight Guide CJ4-V2.0Phil Marsh100% (3)

- Current Revision Levels FOR Instructions For Continued Airworthiness (Ica), Flight Manual Supplements (FMS) and Sa52Document4 pagesCurrent Revision Levels FOR Instructions For Continued Airworthiness (Ica), Flight Manual Supplements (FMS) and Sa52sandyNo ratings yet

- KING KE1107/KEJ1107: Solid Fuel Catalytic StoveDocument60 pagesKING KE1107/KEJ1107: Solid Fuel Catalytic StovesandyNo ratings yet

- Squadron Signal: Aircraft in Action, #1116, MiG-15Document52 pagesSquadron Signal: Aircraft in Action, #1116, MiG-15ghostburned100% (10)

- AAMA RVSM Minimum Monitoring RequirementsDocument18 pagesAAMA RVSM Minimum Monitoring RequirementsUjang SetiawanNo ratings yet

- ALQ-176 (V) - Archived 3/98: OutlookDocument3 pagesALQ-176 (V) - Archived 3/98: OutlookBlaze123xNo ratings yet

- 1 - 32 F-16C - ThunderbirdsDocument3 pages1 - 32 F-16C - ThunderbirdsDesmond GracianniNo ratings yet

- Airbus A300F: European ConsortiumDocument2 pagesAirbus A300F: European ConsortiumNadeemNo ratings yet

- 4.1 Three-View Drawings of Conventional Aircraft ConfigurationsDocument11 pages4.1 Three-View Drawings of Conventional Aircraft ConfigurationsSadhin SaleemNo ratings yet

- Saab 47Document2 pagesSaab 47Gomi9kNo ratings yet

- WindowDocument10 pagesWindowsarvesh_ame2011No ratings yet

- F 15 PDFDocument2 pagesF 15 PDFDavid0% (1)

- F 15e PDFDocument2 pagesF 15e PDFFred0% (3)

- Eduard MiG-21 MF Full Instructions 1-48Document20 pagesEduard MiG-21 MF Full Instructions 1-48Doru Sicoe100% (1)

- 1) Aero L-29 Delfín General Characteristics: WingspanDocument7 pages1) Aero L-29 Delfín General Characteristics: WingspanAjay DevaNo ratings yet

- PresentasiDocument16 pagesPresentasiThomas AmisimNo ratings yet

- The Illustrated History of Fighters PDFDocument276 pagesThe Illustrated History of Fighters PDFvincent216100% (1)

- Selmer Music Guidance BlankDocument1 pageSelmer Music Guidance BlankJazzmond100% (1)

- Marketing Report-Hygiene - 2.0Document1,106 pagesMarketing Report-Hygiene - 2.0nemathNo ratings yet

- User Friendly Conso2017 (35male.35female - Secondary.editedDocument184 pagesUser Friendly Conso2017 (35male.35female - Secondary.editedDaniel NacordaNo ratings yet

- Wing Zero Gundam Color Full by Tos-Craft - Wing Zero Full Color by Tos-CraftDocument25 pagesWing Zero Gundam Color Full by Tos-Craft - Wing Zero Full Color by Tos-Craftfarhan assalamNo ratings yet

- Tail DesignDocument4 pagesTail DesignMuhammed NayeemNo ratings yet

- C-145A, USA - Skytruck Light Twin-Engine AircraftDocument13 pagesC-145A, USA - Skytruck Light Twin-Engine Aircrafthindujudaic100% (1)

- Boeing 787Document7 pagesBoeing 787MARIA ISABEL ARBELAEZNo ratings yet

- De Havilland Sea Venom Flight ManualDocument53 pagesDe Havilland Sea Venom Flight Manualwebmaster1258100% (2)

- CDocument14 pagesCVăn Dương NguyễnNo ratings yet

- Estatus de Publicaciones Manuales PiperDocument68 pagesEstatus de Publicaciones Manuales PiperJesusDavidBlancoNo ratings yet

- Cirrus: Illustrated Parts Catalog Models Sr22 and Sr22TDocument5 pagesCirrus: Illustrated Parts Catalog Models Sr22 and Sr22Thector joel lizarragaNo ratings yet

- Kits OringDocument2 pagesKits OringViniciusNo ratings yet

- Vintage Aircraft Plans List May 17Document51 pagesVintage Aircraft Plans List May 17Rodrigo BasualtoNo ratings yet

- Aircraft Design Project-Ii Supersonic Interceptor FighterDocument5 pagesAircraft Design Project-Ii Supersonic Interceptor FighterJana AeroNo ratings yet

- 1996 - 1113 Tacit BlueDocument1 page1996 - 1113 Tacit Bluedagger21No ratings yet

- AircraftAllocation 01JAN23 V1Document1 pageAircraftAllocation 01JAN23 V1NHS bulawayoNo ratings yet