Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Academia and Clinic: CONSORT 2010 Statement: Updated Guidelines For Reporting Parallel Group Randomized Trials

Academia and Clinic: CONSORT 2010 Statement: Updated Guidelines For Reporting Parallel Group Randomized Trials

Uploaded by

EkaOriginal Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Academia and Clinic: CONSORT 2010 Statement: Updated Guidelines For Reporting Parallel Group Randomized Trials

Academia and Clinic: CONSORT 2010 Statement: Updated Guidelines For Reporting Parallel Group Randomized Trials

Uploaded by

EkaCopyright:

Available Formats

Academia and Clinic Annals of Internal Medicine

CONSORT 2010 Statement: Updated Guidelines for Reporting Parallel

Group Randomized Trials

Kenneth F. Schulz, PhD, MBA; Douglas G. Altman, DSc; and David Moher, PhD, for the CONSORT Group*

The CONSORT (Consolidated Standards of Reporting Trials) state- Ann Intern Med. 2010;152:726-732. www.annals.org

ment is used worldwide to improve the reporting of randomized, For author affiliations, see end of text.

controlled trials. Schulz and colleagues describe the latest version, * For the CONSORT Group contributors to CONSORT 2010, see the Appen-

CONSORT 2010, which updates the reporting guideline based on dix (available at www.annals.org).

new methodological evidence and accumulating experience. This article was published at www.annals.org on 24 March 2010.

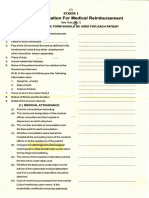

Editor’s Note: In order to encourage dissemination of the (Figure). It provides guidance for reporting all random-

CONSORT 2010 Statement, this article is freely accessible on ized, controlled trials but focuses on the most common

www.annals.org and will also be published in BMJ, The design type—individually randomized, 2-group, parallel

Lancet, Obstetrics & Gynecology, PLoS Medicine, Open trials. Other trial designs, such as cluster randomized trials

Medicine, Journal of Clinical Epidemiology, BMC Medi- and noninferiority trials, require varying amounts of addi-

cine, and Trials. The authors jointly hold the copyright of this tional information. CONSORT extensions for these de-

article. For details on further use, see the CONSORT Web site signs (11, 12), and other CONSORT products, can be

(www.consort-statement.org). found through the CONSORT Web site (www.consort-

statement.org). Along with the CONSORT statement, we

R andomized, controlled trials, when appropriately de-

signed, conducted, and reported, represent the gold

standard in evaluating health care interventions. However,

have updated the explanation and elaboration article (13),

which explains the inclusion of each checklist item, pro-

vides methodological background, and gives published ex-

randomized trials can yield biased results if they lack meth- amples of transparent reporting.

odological rigor (1). To assess a trial accurately, readers of Diligent adherence by authors to the checklist items

a published report need complete, clear, and transparent facilitates clarity, completeness, and transparency of report-

information on its methodology and findings. Unfortu- ing. Explicit descriptions, not ambiguity or omission, best

nately, attempted assessments frequently fail because authors serve the interests of all readers. Note that the CONSORT

of many trial reports neglect to provide lucid and complete 2010 Statement does not include recommendations for de-

descriptions of that critical information (2– 4). signing, conducting, and analyzing trials. It solely addresses

That lack of adequate reporting fueled the develop- the reporting of what was done and what was found.

ment of the original CONSORT (Consolidated Standards Nevertheless, CONSORT does indirectly affect design

of Reporting Trials) statement in 1996 (5) and its revision and conduct. Transparent reporting reveals deficiencies in

5 years later (6 – 8). While those statements improved the research if they exist. Thus, investigators who conduct in-

reporting quality for some randomized, controlled trials (9, adequate trials, but who must transparently report, should

10), many trial reports still remain inadequate (2). Further- not be able to pass through the publication process without

more, new methodological evidence and additional experi- revelation of their trials’ inadequacies. That emerging real-

ence has accumulated since the last revision in 2001. Con- ity should provide impetus to improved trial design and

sequently, we organized a CONSORT Group meeting to conduct in the future, a secondary indirect goal of our

update the 2001 statement (6 – 8). We introduce here the work. Moreover, CONSORT can help researchers in de-

result of that process, CONSORT 2010. signing their trial.

INTENT OF CONSORT 2010

BACKGROUND TO CONSORT

The CONSORT 2010 Statement is this paper, in-

Efforts to improve the reporting of randomized, con-

cluding the 25-item checklist (Table) and the flow diagram

trolled trials accelerated in the mid-1990s, spurred partly

by methodological research. Researchers had shown for

many years that authors reported such trials poorly, and

See also: empirical evidence began to accumulate that some poorly

conducted or poorly reported aspects of trials were associ-

Web-Only ated with bias (14). Two initiatives aimed at developing

Appendix reporting guidelines culminated in one of us (D.M.) and

Conversion of graphics into slides Drummond Rennie organizing the first CONSORT state-

ment in 1996 (5). Further methodological research on sim-

726 1 June 2010 Annals of Internal Medicine Volume 152 • Number 11 www.annals.org

Downloaded From: http://annals.org/ on 11/01/2016

CONSORT 2010 Statement Academia and Clinic

Table. CONSORT 2010 Checklist of Information to Include When Reporting a Randomized Trial*

Section/Topic Item Checklist Item Reported on

Number Page Number

Title and abstract 1a Identification as a randomized trial in the title

1b Structured summary of trial design, methods, results, and conclusions (for specific

guidance, see CONSORT for abstracts [21, 31])

Introduction

Background and objectives 2a Scientific background and explanation of rationale

2b Specific objectives or hypotheses

Methods

Trial design 3a Description of trial design (such as parallel, factorial), including allocation ratio

3b Important changes to methods after trial commencement (such as eligibility

criteria), with reasons

Participants 4a Eligibility criteria for participants

4b Settings and locations where the data were collected

Interventions 5 The interventions for each group with sufficient details to allow replication,

including how and when they were actually administered

Outcomes 6a Completely defined prespecified primary and secondary outcome measures,

including how and when they were assessed

6b Any changes to trial outcomes after the trial commenced, with reasons

Sample size 7a How sample size was determined

7b When applicable, explanation of any interim analyses and stopping guidelines

Randomization

Sequence generation 8a Method used to generate the random allocation sequence

8b Type of randomization; details of any restriction (such as blocking and block size)

Allocation concealment mechanism 9 Mechanism used to implement the random allocation sequence (such as

sequentially numbered containers), describing any steps taken to conceal the

sequence until interventions were assigned

Implementation 10 Who generated the random allocation sequence, who enrolled participants, and

who assigned participants to interventions

Blinding 11a If done, who was blinded after assignment to interventions (for example,

participants, care providers, those assessing outcomes) and how

11b If relevant, description of the similarity of interventions

Statistical methods 12a Statistical methods used to compare groups for primary and secondary outcomes

12b Methods for additional analyses, such as subgroup analyses and adjusted analyses

Results

Participant flow (a diagram is 13a For each group, the numbers of participants who were randomly assigned,

strongly recommended) received intended treatment, and were analyzed for the primary outcome

13b For each group, losses and exclusions after randomization, together with reasons

Recruitment 14a Dates defining the periods of recruitment and follow-up

14b Why the trial ended or was stopped

Baseline data 15 A table showing baseline demographic and clinical characteristics for each group

Numbers analyzed 16 For each group, number of participants (denominator) included in each analysis

and whether the analysis was by original assigned groups

Outcomes and estimation 17a For each primary and secondary outcome, results for each group, and the

estimated effect size and its precision (such as 95% confidence interval)

17b For binary outcomes, presentation of both absolute and relative effect sizes is

recommended

Ancillary analyses 18 Results of any other analyses performed, including subgroup analyses and

adjusted analyses, distinguishing prespecified from exploratory

Harms 19 All important harms or unintended effects in each group (for specific guidance,

see CONSORT for harms [28])

Discussion

Limitations 20 Trial limitations; addressing sources of potential bias; imprecision; and, if relevant,

multiplicity of analyses

Generalizability 21 Generalizability (external validity, applicability) of the trial findings

Interpretation 22 Interpretation consistent with results, balancing benefits and harms, and

considering other relevant evidence

Other information

Registration 23 Registration number and name of trial registry

Protocol 24 Where the full trial protocol can be accessed, if available

Funding 25 Sources of funding and other support (such as supply of drugs), role of funders

CONSORT ⫽ Consolidated Standards of Reporting Trials.

* We strongly recommend reading this statement in conjunction with the CONSORT 2010 Explanation and Elaboration (13) for important clarifications on all the items.

If relevant, we also recommend reading CONSORT extensions for cluster randomized trials (11), noninferiority and equivalence trials (12), nonpharmacologic treatments

(32), herbal interventions (33), and pragmatic trials (34). Additional extensions are forthcoming: For those and for up-to-date references relevant to this checklist, see

www.consort-statement.org.

www.annals.org 1 June 2010 Annals of Internal Medicine Volume 152 • Number 11 727

Downloaded From: http://annals.org/ on 11/01/2016

Academia and Clinic CONSORT 2010 Statement

needed expertise, we invite new members to contribute. As

Figure. Flow diagram of the progress through the phases of

such, CONSORT continually assimilates new ideas and

a parallel randomized trial of 2 groups (that is, enrollment,

perspectives. That process informs the continually evolving

intervention allocation, follow-up, and data analysis).

CONSORT statement.

Over time, CONSORT has garnered much support.

Assessed for More than 400 journals, published around the world

eligibility (n = ...) and in many languages, have explicitly supported the

CONSORT statement. Many other health care journals

Excluded (n = ...) support it without our knowledge. Moreover, thousands

more have implicitly supported it with the endorsement of

Enrollment

Not meeting inclusion

criteria (n = ...) the CONSORT statement by the International Commit-

Declined to participate

(n = ...) tee of Medical Journal Editors (www.icmje.org). Other

Other reasons (n = ...) prominent editorial groups, the Council of Science Editors

and the World Association of Medical Editors, officially

Randomized (n = ...) support CONSORT. That support seems warranted:

When used by authors and journals, CONSORT seems to

improve reporting (9).

Allocated to intervention Allocated to intervention DEVELOPMENT OF CONSORT 2010

(n = ...) (n = ...)

Thirty-one members of the CONSORT 2010 Group

Allocation

Received allocated Received allocated

intervention (n = ...) intervention (n = ...) met in Montebello, Quebec, Canada, in January 2007 to

Did not receive allocated Did not receive allocated

intervention (give intervention (give

update the 2001 CONSORT statement. In addition to the

reasons) (n = ...) reasons) (n = ...) accumulating evidence relating to existing checklist items,

several new issues had come to prominence since 2001.

Some participants were given primary responsibility for ag-

Lost to follow-up (give Lost to follow-up (give gregating and synthesizing the relevant evidence on a par-

Follow-up

reasons) (n = ...) reasons) (n = ...) ticular checklist item of interest. Based on that evidence,

Discontinued intervention Discontinued intervention the group deliberated the value of each item. As in prior

(give reasons) (n = ...) (give reasons) (n = ...)

CONSORT versions, we kept only those items deemed

absolutely fundamental to reporting a randomized, con-

trolled trial. Moreover, an item may be fundamental to a

Analyzed (n = ...) Analyzed (n = ...)

Analysis

Excluded from analysis Excluded from analysis trial but not included, such as approval by an institutional

(give reasons) (n = ...) (give reasons) (n = ...) ethical review board, because funding bodies strictly en-

force ethical review and medical journals usually address

reporting ethical review in their instructions for authors.

Other items may seem desirable, such as reporting on

whether on-site monitoring was done, but a lack of empir-

ilar topics reinforced earlier findings (15) and fed into the ical evidence or any consensus on their value cautions

revision of 2001 (6 – 8). Subsequently, the expanding body against inclusion at this point. The CONSORT 2010

of methodological research informed the refinement of Statement thus addresses the minimum criteria, although

CONSORT 2010. More than 700 studies comprise the that should not deter authors from including other infor-

CONSORT database (located on the CONSORT Web mation if they consider it important.

site), which provides the empirical evidence to underpin After the meeting, the CONSORT Executive con-

the CONSORT initiative. vened teleconferences and meetings to revise the checklist.

Indeed, CONSORT Group members continually After 7 major iterations, a revised checklist was distributed

monitor the literature. Information gleaned from these ef- to the larger group for feedback. With that feedback, the

forts provides an evidence base on which to update the Executive met twice in person to consider all the com-

CONSORT statement. We add, drop, or modify items ments and to produce a penultimate version. That served

based on that evidence and the recommendations of the as the basis for writing the first draft of this paper, which

CONSORT Group, an international and eclectic group of was then distributed to the group for feedback. After con-

clinical trialists, statisticians, epidemiologists, and biomed- sideration of their comments, the Executive finalized the

ical editors. The CONSORT Executive (K.F.S., D.G.A., statement.

D.M.) strives for a balance of established and emerging The CONSORT Executive then drafted an updated

researchers. The membership of the group is dynamic. As explanation and elaboration manuscript, with assistance

our work expands in response to emerging projects and from other members of the larger group. The substance of

728 1 June 2010 Annals of Internal Medicine Volume 152 • Number 11 www.annals.org

Downloaded From: http://annals.org/ on 11/01/2016

CONSORT 2010 Statement Academia and Clinic

the 2007 CONSORT meeting provided the material for vides information on all reporting guidelines in health

the update. The updated explanation and elaboration research.

manuscript was distributed to the entire group for addi- With CONSORT 2010, we again intentionally de-

tions, deletions, and changes. That final iterative process clined to produce a rigid structure for the reporting of

converged to the CONSORT 2010 Explanation and randomized trials. Indeed, Standards of Reporting Tri-

Elaboration (13). als (SORT) (19) tried a rigid format, and it failed in a

pilot run with an editor and authors (20). Conse-

CHANGES IN CONSORT 2010 quently, the format of articles should abide by journal

style; editorial directions; the traditions of the research

The revision process resulted in evolutionary, not rev-

field addressed; and, where possible, author preferences.

olutionary, changes to the checklist (Table), and the flow

We do not wish to standardize the structure of report-

diagram was not modified except for 1 word (Figure).

ing. Authors should simply address checklist items

Moreover, because other reporting guidelines augmenting

somewhere in the article, with ample detail and lucidity.

the checklist refer to item numbers, we kept the existing

That stated, we think that manuscripts benefit from fre-

items under their previous item numbers except for some

quent subheadings within the major sections, especially

renumbering of items 2 to 5. We added additional items

the methods and results sections.

either as a subitem under an existing item, an entirely new

CONSORT urges completeness, clarity, and transpar-

item number at the end of the checklist, or (with item 3)

ency of reporting, which simply reflects the actual trial

an interjected item into a renumbered segment. We have

design and conduct. However, as a potential drawback, a

summarized the noteworthy general changes in Box 1 and

reporting guideline might encourage some authors to re-

specific changes in Box 2. The CONSORT Web site con-

port fictitiously the information suggested by the guidance

tains a side-by-side comparison of the 2001 and 2010

rather than what was actually done. Authors, peer review-

versions.

ers, and editors should vigilantly guard against that poten-

tial drawback and refer, for example, to trial protocols, to

IMPLICATIONS AND LIMITATIONS information on trial registers, and to regulatory agency

We developed CONSORT 2010 to assist authors in Web sites. Moreover, the CONSORT 2010 Statement

writing reports of randomized, controlled trials, editors and does not include recommendations for designing and con-

peer reviewers in reviewing manuscripts for publication, ducting randomized trials. The items should elicit clear

and readers in critically appraising published articles. The pronouncements of how and what the authors did, but do

CONSORT 2010 Explanation and Elaboration provides not contain any judgments on how and what the authors

elucidation and context to the checklist items. We strongly should have done. Thus, CONSORT 2010 is not in-

recommend using the explanation and elaboration in con- tended as an instrument to evaluate the quality of a trial.

junction with the checklist to foster complete, clear, and Nor is it appropriate to use the checklist to construct a

transparent reporting and aid appraisal of published trial “quality score.”

reports.

CONSORT 2010 focuses predominantly on the

2-group, parallel randomized, controlled trial, which ac-

counts for over half of trials in the literature (2). Most of Box 1. Noteworthy general changes in the CONSORT 2010

the items from the CONSORT 2010 Statement, however, Statement.

pertain to all types of randomized trials. Nevertheless,

some types of trials or trial situations dictate the need for

We simplified and clarified the wording, such as in items 1, 8, 10, 13,

additional information in the trial report. When in doubt, 15, 16, 18, 19, and 21.

authors, editors, and readers should consult the CONSORT

Web site for any CONSORT extensions, expansions (am- We improved consistency of style across the items by removing the

imperative verbs that were in the 2001 version.

plifications), implementations, or other guidance that may

be relevant. We enhanced specificity of appraisal by breaking some items into

The evidence-based approach we have used for subitems. Many journals expect authors to complete a CONSORT

checklist indicating where in the manuscript the items have been

CONSORT also served as a model for development of addressed. Experience with the checklist noted pragmatic difficulties

other reporting guidelines, such as for reporting systematic when an item comprised multiple elements. For example, item 4

reviews and meta-analyses of studies evaluating interven- addresses eligibility of participants and the settings and locations of

data collection. With the 2001 version, an author could provide a

tions (16), diagnostic studies (17), and observational page number for that item on the checklist but might have reported

studies (18). The explicit goal of all these initiatives is to only eligibility in the paper, for example, and not reported the settings

improve reporting. The Enhancing the Quality and and locations. CONSORT 2010 relieves obfuscations and forces

authors to provide page numbers in the checklist for both eligibility

Transparency of Health Research (EQUATOR) Network and settings.

will facilitate development of reporting guidelines and help

disseminate the guidelines: www.equator-network.org pro-

www.annals.org 1 June 2010 Annals of Internal Medicine Volume 152 • Number 11 729

Downloaded From: http://annals.org/ on 11/01/2016

Academia and Clinic CONSORT 2010 Statement

Box 2. Noteworthy specific changes in the CONSORT 2010 Statement.

Item 1b (title and abstract)—We added a subitem on providing a structured summary of trial design, methods, results, and conclusions and referenced

the CONSORT for abstracts article (21).

Item 2b (introduction)—We added a new subitem (formerly item 5 in CONSORT 2001) on “Specific objectives or hypotheses.”

Item 3a (trial design)—We added a new item including this subitem to clarify the basic trial design (such as parallel group, crossover, cluster) and the

allocation ratio.

Item 3b (trial design)—We added a new subitem that addresses any important changes to methods after trial commencement, with a discussion of

reasons.

Item 4 (participants)—Formerly item 3 in CONSORT 2001.

Item 5 (interventions)—Formerly item 4 in CONSORT 2001. We encouraged greater specificity by stating that descriptions of interventions should include

“sufficient details to allow replication” (3).

Item 6 (outcomes)—We added a subitem on identifying any changes to the primary and secondary outcome (end point) measures after the trial started.

This followed from empirical evidence that authors frequently provide analyses of outcomes in their published papers that were not the prespecified

primary and secondary outcomes in their protocols, while ignoring their prespecified outcomes (that is, selective outcome reporting) (4, 22). We eliminated

text on any methods used to enhance the quality of measurements.

Item 9 (allocation concealment mechanism)—We reworded this to include mechanism in both the report topic and the descriptor to reinforce that authors

should report the actual steps taken to ensure allocation concealment rather than simply report imprecise, perhaps banal, assurances of concealment.

Item 11 (blinding)—We added the specification of how blinding was done and, if relevant, a description of the similarity of interventions and procedures.

We also eliminated text on “how the success of blinding (masking) was assessed” because of a lack of empirical evidence supporting the practice, as well

as theoretical concerns about the validity of any such assessment (23, 24).

Item 12a (statistical methods)—We added that statistical methods should also be provided for analysis of secondary outcomes.

Subitem 14b (recruitment)—Based on empirical research, we added a subitem on “Why the trial ended or was stopped” (25).

Item 15 (baseline data)—We specified “A table” to clarify that baseline and clinical characteristics of each group are most clearly expressed in a table.

Item 16 (numbers analyzed)—We replaced mention of “intention to treat” analysis, a widely misused term, by a more explicit request for information

about retaining participants in their original assigned groups (26).

Subitem 17b (outcomes and estimation)—For appropriate clinical interpretability, prevailing experience suggested the addition of “For binary outcomes,

presentation of both relative and absolute effect sizes is recommended” (27).

Item 19 (harms)—We included a reference to the CONSORT paper on harms (28).

Item 20 (limitations)—We changed the topic from “Interpretation” and supplanted the prior text with a sentence focusing on the reporting of sources of

potential bias and imprecision.

Item 22 (interpretation)—We changed the topic from “Overall evidence.” Indeed, we understand that authors should be allowed leeway for

interpretation under this nebulous heading. However, the CONSORT Group expressed concerns that conclusions in papers frequently misrepresented the

actual analytical results and that harms were ignored or marginalized. Therefore, we changed the checklist item to include the concepts of results matching

interpretations and of benefits being balanced with harms.

Item 23 (registration)—We added a new item on trial registration. Empirical evidence supports the need for trial registration, and recent requirements by

journal editors have fostered compliance (29).

Item 24 (protocol)—We added a new item on availability of the trial protocol. Empirical evidence suggests that authors often ignore, in the conduct and

reporting of their trial, what they stated in the protocol (4, 22). Hence, availability of the protocol can instigate adherence to the protocol before

publication and facilitate assessment of adherence after publication.

Item 25 (funding)—We added a new item on funding. Empirical evidence points toward funding source sometimes being associated with estimated

treatment effects (30).

Nevertheless, we suggest that researchers begin trials tant aspects of their trial. The ensuing scrutiny rewards

with their end publication in mind. Poor reporting allows well-conducted trials and penalizes poorly conducted trials.

authors, intentionally or inadvertently, to escape scrutiny Thus, investigators should understand the CONSORT

of any weak aspects of their trials. However, with wide 2010 reporting guidelines before starting a trial as a further

adoption of CONSORT by journals and editorial groups, incentive to design and conduct their trials according to

most authors should have to report transparently all impor- rigorous standards.

730 1 June 2010 Annals of Internal Medicine Volume 152 • Number 11 www.annals.org

Downloaded From: http://annals.org/ on 11/01/2016

CONSORT 2010 Statement Academia and Clinic

CONSORT 2010 supplants the prior version pub- 18583680]

4. Dwan K, Altman DG, Arnaiz JA, Bloom J, Chan AW, Cronin E, et al.

lished in 2001. Any support for the earlier version accu- Systematic review of the empirical evidence of study publication bias and out-

mulated from journals or editorial groups will automati- come reporting bias. PLoS One. 2008;3:e3081. [PMID: 18769481]

cally extend to this newer version, unless specifically 5. Begg C, Cho M, Eastwood S, Horton R, Moher D, Olkin I, et al. Improving

requested otherwise. Journals that do not currently support the quality of reporting of randomized controlled trials. The CONSORT state-

ment. JAMA. 1996;276:637-9. [PMID: 8773637]

CONSORT may do so by registering on the CONSORT 6. Moher D, Schulz KF, Altman DG. The CONSORT statement: revised rec-

Web site. If a journal supports or endorses CONSORT ommendations for improving the quality of reports of parallel-group randomised

2010, it should cite one of the original versions of trials. Lancet. 2001;357:1191-4. [PMID: 11323066]

CONSORT 2010, the CONSORT 2010 Explanation and 7. Moher D, Schulz KF, Altman DG; CONSORT GROUP (Consolidated

Standards of Reporting Trials). The CONSORT statement: revised recommen-

Elaboration, and the CONSORT Web site in their “in- dations for improving the quality of reports of parallel-group randomized trials.

structions to authors.” We suggest that authors who wish Ann Intern Med. 2001;134:657-62. [PMID: 11304106]

to cite CONSORT should cite this or another of the orig- 8. Moher D, Schulz KF, Altman D; CONSORT Group (Consolidated Stan-

inal journal versions of CONSORT 2010 Statement and, dards of Reporting Trials). The CONSORT statement: revised recommenda-

tions for improving the quality of reports of parallel-group randomized trials.

if appropriate, the CONSORT 2010 Explanation and JAMA. 2001;285:1987-91. [PMID: 11308435]

Elaboration (13). All CONSORT material can be accessed 9. Plint AC, Moher D, Morrison A, Schulz K, Altman DG, Hill C, et al. Does

through the original publishing journals or the CONSORT the CONSORT checklist improve the quality of reports of randomised con-

Web site. Groups or individuals who desire to translate the trolled trials? A systematic review. Med J Aust. 2006;185:263-7. [PMID:

16948622]

CONSORT 2010 Statement into other languages should first 10. Hopewell S, Dutton S, Yu LM, Chan AW, Altman DG. The quality of

consult the CONSORT policy statement on the Web site. reports of randomised trials in 2000 and 2006: a comparative study of articles

We emphasize that CONSORT 2010 represents an indexed by PubMed. BMJ. 2010;340:c723.

evolving guideline. It requires perpetual reappraisal and, if 11. Campbell MK, Elbourne DR, Altman DG; CONSORT group. CONSORT

statement: extension to cluster randomised trials. BMJ. 2004;328:702-8.

necessary, modifications. In the future, we will further revise [PMID: 15031246]

the CONSORT material considering comments, criticisms, 12. Piaggio G, Elbourne DR, Altman DG, Pocock SJ, Evans SJ; CONSORT

experiences, and accumulating new evidence. We invite read- Group. Reporting of noninferiority and equivalence randomized trials: an exten-

ers to submit recommendations via the CONSORT Web sion of the CONSORT statement. JAMA. 2006;295:1152-60. [PMID:

16522836]

site. 13. Moher D, Hopewell S, Schulz KF, Montori V, Gøtzsche PC, Devereaux

PJ, et al. CONSORT 2010 Explanation and Elaboration: updated guidelines for

From Family Health International, Research Triangle Park, North Caro- reporting parallel group randomised trials. BMJ. 2010;340:c869.

lina; Centre for Statistics in Medicine, University of Oxford, Wolfson 14. Schulz KF, Chalmers I, Hayes RJ, Altman DG. Empirical evidence of bias.

College, Oxford, United Kingdom; and Ottawa Methods Centre, Clin- Dimensions of methodological quality associated with estimates of treatment ef-

ical Epidemiology Program, Ottawa Hospital Research Institute, Univer- fects in controlled trials. JAMA. 1995;273:408-12. [PMID: 7823387]

sity of Ottawa, Ottawa, Ontario, Canada. 15. Moher D, Pham B, Jones A, Cook DJ, Jadad AR, Moher M, et al. Does

quality of reports of randomised trials affect estimates of intervention efficacy

Grant Support: From United Kingdom National Institute for Health reported in meta-analyses? Lancet. 1998;352:609-13. [PMID: 9746022]

16. Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, Altman DG; PRISMA Group. Preferred

Research and the Medical Research Council; Canadian Institutes of

reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: the PRISMA statement.

Health Research; Presidents Fund, Canadian Institutes of Health Re-

Ann Intern Med. 2009;151:264-9, W64. [PMID: 19622511]

search; Johnson & Johnson; BMJ; and American Society for Clinical 17. Bossuyt PM, Reitsma JB, Bruns DE, Gatsonis CA, Glasziou PP, Irwig LM,

Oncology. Dr. Altman is supported by Cancer Research UK, Dr. Moher et al; Standards for Reporting of Diagnostic Accuracy. Towards complete and

by a University of Ottawa Research Chair, and Dr. Schulz by Family accurate reporting of studies of diagnostic accuracy: The STARD Initiative. Ann

Health International. None of the sponsors had any involvement in the Intern Med. 2003;138:40-4. [PMID: 12513043]

planning, execution, or writing of the CONSORT documents. In addi- 18. von Elm E, Altman DG, Egger M, Pocock SJ, Gøtzsche PC, Vandenbro-

tion, no funder played a role in drafting the manuscript. ucke JP; STROBE Initiative. The Strengthening the Reporting of Observational

Studies in Epidemiology (STROBE) statement: guidelines for reporting observa-

Potential Conflicts of Interest: Disclosures can be viewed at www.acponline tional studies. Ann Intern Med. 2007;147:573-7. [PMID: 17938396]

19. The Standards of Reporting Trials Group. A proposal for structured report-

.org/authors/icmje/ConflictOfInterestForms.do?msNum⫽M10-0379.

ing of randomized controlled trials. JAMA. 1994;272:1926-31. [PMID:

7990245]

Corresponding Author: Kenneth F. Schulz, PhD, MBA, Family Health 20. Rennie D. Reporting randomized controlled trials. An experiment and a call

International, PO Box 13950, Research Triangle Park, NC 27709. for responses from readers [Editorial]. JAMA. 1995;273:1054-5. [PMID:

7897791]

Current author addresses and author contributions are available at www 21. Hopewell S, Clarke M, Moher D, Wager E, Middleton P, Altman DG,

.annals.org. et al; CONSORT Group. CONSORT for reporting randomised trials in journal

and conference abstracts. Lancet. 2008;371:281-3. [PMID: 18221781]

22. Chan AW, Hróbjartsson A, Haahr MT, Gøtzsche PC, Altman DG. Em-

pirical evidence for selective reporting of outcomes in randomized trials: compar-

References ison of protocols to published articles. JAMA. 2004;291:2457-65. [PMID:

1. Jüni P, Altman DG, Egger M. Systematic reviews in health care: Assessing the 15161896]

quality of controlled clinical trials. BMJ. 2001;323:42-6. [PMID: 11440947] 23. Sackett DL. Commentary: Measuring the success of blinding in RCTs: don’t,

2. Chan AW, Altman DG. Epidemiology and reporting of randomised trials must, can’t or needn’t? Int J Epidemiol. 2007;36:664-5. [PMID: 17675306]

published in PubMed journals. Lancet. 2005;365:1159-62. [PMID: 15794971] 24. Schulz KF, Grimes DA. Blinding in randomised trials: hiding who got what.

3. Glasziou P, Meats E, Heneghan C, Shepperd S. What is missing from de- Lancet. 2002;359:696-700. [PMID: 11879884]

scriptions of treatment in trials and reviews? BMJ. 2008;336:1472-4. [PMID: 25. Montori VM, Devereaux PJ, Adhikari NK, Burns KE, Eggert CH, Briel M,

www.annals.org 1 June 2010 Annals of Internal Medicine Volume 152 • Number 11 731

Downloaded From: http://annals.org/ on 11/01/2016

Academia and Clinic CONSORT 2010 Statement

et al. Randomized trials stopped early for benefit: a systematic review. JAMA. 1167-70. [PMID: 12775614

2005;294:2203-9. [PMID: 16264162] 31. Hopewell S, Clarke M, Moher D, Wager E, Middleton P, Altman DG,

26. Hollis S, Campbell F. What is meant by intention to treat analysis? Survey of et al; CONSORT Group. CONSORT for reporting randomized controlled

published randomised controlled trials. BMJ. 1999;319:670-4. [PMID: 10480822] trials in journal and conference abstracts: explanation and elaboration. PLoS

27. Nuovo J, Melnikow J, Chang D. Reporting number needed to treat and Med. 2008;5:e20. [PMID: 18215107]

absolute risk reduction in randomized controlled trials. JAMA. 2002;287:2813-4. 32. Boutron I, Moher D, Altman DG, Schulz KF, Ravaud P; CONSORT

[PMID: 12038920] Group. Extending the CONSORT statement to randomized trials of nonphar-

28. Ioannidis JP, Evans SJ, Gøtzsche PC, O’Neill RT, Altman DG, Schulz K, macologic treatment: explanation and elaboration. Ann Intern Med. 2008;148:

et al; CONSORT Group. Better reporting of harms in randomized trials: an 295-309. [PMID: 18283207]

extension of the CONSORT statement. Ann Intern Med. 2004;141:781-8. 33. Gagnier JJ, Boon H, Rochon P, Moher D, Barnes J, Bombardier C;

[PMID: 15545678] CONSORT Group. Reporting randomized, controlled trials of herbal interven-

29. De Angelis C, Drazen JM, Frizelle FA, Haug C, Hoey J, Horton R, et al; tions: an elaborated CONSORT statement. Ann Intern Med. 2006;144:364-7.

International Committee of Medical Journal Editors. Clinical trial registration: [PMID: 16520478]

a statement from the International Committee of Medical Journal Editors [Edi- 34. Zwarenstein M, Treweek S, Gagnier JJ, Altman DG, Tunis S,

torial]. Ann Intern Med. 2004;141:477-8. [PMID: 15355883] Haynes B, et al; CONSORT group. Improving the reporting of prag-

30. Lexchin J, Bero LA, Djulbegovic B, Clark O. Pharmaceutical industry spon- matic trials: an extension of the CONSORT statement. BMJ. 2008;337:

sorship and research outcome and quality: systematic review. BMJ. 2003;326: a2390. [PMID: 19001484]

ANNALS OF INTERNAL MEDICINE JUNIOR INVESTIGATOR AWARDS

Beginning in 2010, Annals of Internal Medicine and the American Col-

lege of Physicians will recognize excellence among internal medicine

trainees and junior investigators with annual awards for original research

and scholarly review articles published in Annals in each of the following

categories:

● Most outstanding article with a first author in an internal medicine

residency program or a general medicine or internal medicine sub-

specialty fellowship program

● Most outstanding article with a first author within 3 years following

completion of training in internal medicine or one of its subspecialties

Selection of award winners will consider the article’s novelty, method-

ological rigor, clarity of presentation, and potential to influence practice,

policy, or future research. Judges will include Annals Editors and repre-

sentatives from Annals’ Editorial Board and the American College of

Physicians’ Education/Publication Committee.

Papers published in the year following submission are eligible for the

award in the year of publication. First author status at the time of

manuscript submission will determine eligibility. Authors should indicate

that they wish to have their papers considered for an award when they

submit the manuscript, and they must be able to provide satisfactory

documentation of their eligibility if selected for an award. Announcement

of awards for a calendar year will occur in January of the subsequent

year. We will provide award winners with a framed certificate, a letter

documenting the award, and complimentary registration for the Ameri-

can College of Physicians’ annual meeting.

Please refer questions to Mary Beth Schaeffer at mschaeffer@acponline

.org.

732 1 June 2010 Annals of Internal Medicine Volume 152 • Number 11 www.annals.org

Downloaded From: http://annals.org/ on 11/01/2016

Annals of Internal Medicine

Current Author Addresses: Dr. Schulz: Family Health International, ment; Isabelle Boutron, Université Paris 7 Denis Diderot,

PO Box 13950, Research Triangle Park, NC 27709. Assistance Publique des Hôpitaux de Paris, INSERM; P.J. Deve-

Dr. Altman: Centre for Statistics in Medicine, University of Oxford,

reaux, McMaster University; Kay Dickersin, Johns Hopkins

Wolfson College Annexe, Linton Road, Oxford OX2 6UD, United

Kingdom. Bloomberg School of Public Health; Diana Elbourne, London

Dr. Moher: Ottawa Methods Centre, Clinical Epidemiology Program, School of Hygiene & Tropical Medicine; Susan Ellenberg, Uni-

Ottawa Hospital Research Institute, Department of Epidemiology and versity of Pennsylvania School of Medicine; Val Gebski, Univer-

Community Medicine, University of Ottawa, 501 Smyth Road, 6th sity of Sydney; Steven Goodman, Clinical Trials: Journal of the

Floor, Critical Care Wing, Room W6112, Ottawa, Ontario K1H 8L6, Society for Clinical Trials; Peter C. Gøtzsche, Nordic Cochrane

Canada.

Centre; Trish Groves, BMJ; Steven Grunberg, American Society

Author Contributions: Conception and design: K.F. Schulz, D.G. of Clinical Oncology; Brian Haynes, McMaster University; Sally

Altman, D. Moher. Hopewell, Centre for Statistics in Medicine, University of Ox-

Analysis and interpretation of the data: K.F. Schulz, D. Moher. ford; Astrid James, The Lancet; Peter Juhn, Johnson & Johnson;

Drafting of the article: K.F. Schulz, D.G. Altman, D. Moher. Philippa Middleton, University of Adelaide; Don Minckler, Uni-

Critical revision of the article for important intellectual content: K.F.

versity of California, Irvine; David Moher, Ottawa Methods

Schulz, D.G. Altman, D. Moher.

Final approval of the article: K.F. Schulz, D.G. Altman, D. Moher. Centre, Clinical Epidemiology Program, Ottawa Hospital Re-

Statistical expertise: D.G. Altman, K.F. Schulz. search Institute; Victor M. Montori, Knowledge and Encounter

Obtaining of funding: D. Moher. Research Unit, Mayo Clinic College of Medicine; Cynthia Mul-

Administrative, technical, or logistic support: D. Moher. row, Annals of Internal Medicine; Stuart Pocock, London School

Collection and assembly of data: K.F. Schulz, D. Moher. of Hygiene & Tropical Medicine; Drummond Rennie, JAMA;

David L. Schriger, Annals of Emergency Medicine; Kenneth F.

APPENDIX: THE CONSORT GROUP CONTRIBUTORS Schulz, Family Health International; Iveta Simera, EQUATOR

TO CONSORT 2010 Network; and Elizabeth Wager, Sideview.

Douglas G. Altman, Centre for Statistics in Medicine, Uni- Contributors to CONSORT 2010 who did not attend the

versity of Oxford; Virginia Barbour, PLoS Medicine; Jesse A. Ber- Montebello meeting: Mike Clarke, UK Cochrane Centre, and

lin, Johnson & Johnson Pharmaceutical Research and Develop- Gordon Guyatt, McMaster University.

www.annals.org 1 June 2010 Annals of Internal Medicine Volume 152 • Number 11 W-293

Downloaded From: http://annals.org/ on 11/01/2016

You might also like

- CONSORT Group CONSORT 2010 Statement Updated GuideDocument8 pagesCONSORT Group CONSORT 2010 Statement Updated GuideSmulskii AndriiNo ratings yet

- Research Methods & Reporting: Consort 2010 Statement: Updated Guidelines For Reporting Parallel Group Randomised TrialsDocument6 pagesResearch Methods & Reporting: Consort 2010 Statement: Updated Guidelines For Reporting Parallel Group Randomised TrialsApohena NoroyaNo ratings yet

- CONSORT 2010 Statement: Updated Guidelines For Reporting Parallel Group Randomised TrialsDocument8 pagesCONSORT 2010 Statement: Updated Guidelines For Reporting Parallel Group Randomised TrialsAshwini KalantriNo ratings yet

- All Sessions - Bolignao D - The Quality of Reporting in Clinical Research The Consort and Strobe InitiativesDocument7 pagesAll Sessions - Bolignao D - The Quality of Reporting in Clinical Research The Consort and Strobe Initiativesnmmathew mathewNo ratings yet

- Jepretan Layar 2023-08-13 Pada 16.28.32Document28 pagesJepretan Layar 2023-08-13 Pada 16.28.32aceriogtNo ratings yet

- Consort 2010 ESPLANATDocument38 pagesConsort 2010 ESPLANATCesar Garcia EstradaNo ratings yet

- CONSORTDocument37 pagesCONSORTEmanuel MurguiaNo ratings yet

- CONSORT For Reporting Randomized Controlled Trials in Journal and Conference Abstracts: Explanation and ElaborationDocument9 pagesCONSORT For Reporting Randomized Controlled Trials in Journal and Conference Abstracts: Explanation and ElaborationTakdir Ul haqNo ratings yet

- Jepretan Layar 2023-08-08 Pada 10.16.05Document9 pagesJepretan Layar 2023-08-08 Pada 10.16.05aceriogtNo ratings yet

- Reporting of Patient-Reported Outcomes in Randomized Trials: The CONSORT PRO ExtensionDocument9 pagesReporting of Patient-Reported Outcomes in Randomized Trials: The CONSORT PRO ExtensionPAULA ALEJANDRA MARTIN RAMIREZNo ratings yet

- Consort - RoutineDocument20 pagesConsort - RoutineMahadevan DNo ratings yet

- Methodology and Reporting Quality of Reporting Guidelines: Systematic ReviewDocument9 pagesMethodology and Reporting Quality of Reporting Guidelines: Systematic ReviewJose Evangelista TenorioNo ratings yet

- 2014 145 1 1 1 PandisDocument1 page2014 145 1 1 1 PandisAlla MushkeyNo ratings yet

- 2013 Consort ProDocument9 pages2013 Consort ProSiney De la CruzNo ratings yet

- Observational StudyDocument3 pagesObservational StudyWilliam SWNo ratings yet

- Editorial PJP91Document3 pagesEditorial PJP91Selma GhozaliNo ratings yet

- Consort 2010 Explanation and Elaboration - Updated Guidelines For Reporting Paralel Group Randomised Trials (Moher, 2010)Document37 pagesConsort 2010 Explanation and Elaboration - Updated Guidelines For Reporting Paralel Group Randomised Trials (Moher, 2010)Irina GîrleanuNo ratings yet

- Research and Reporting Methods: SPIRIT 2013 Statement: Defining Standard Protocol Items For Clinical TrialsDocument10 pagesResearch and Reporting Methods: SPIRIT 2013 Statement: Defining Standard Protocol Items For Clinical TrialsSimon ReichNo ratings yet

- Penjelasan Consort Utk Artikel KlinisDocument28 pagesPenjelasan Consort Utk Artikel KlinisWitri Septia NingrumNo ratings yet

- Int J Paed Dentistry - 2020 - Jayaraman - Guidelines For Reporting Randomized Controlled Trials in Paediatric DentistryDocument18 pagesInt J Paed Dentistry - 2020 - Jayaraman - Guidelines For Reporting Randomized Controlled Trials in Paediatric DentistryjaberNo ratings yet

- Research Methods & Reporting: Consort 2010 Statement: Extension To Cluster Randomised TrialsDocument21 pagesResearch Methods & Reporting: Consort 2010 Statement: Extension To Cluster Randomised TrialsMarcia MejíaNo ratings yet

- PRISMA-DTA For Abstracts: A New Addition To The Toolbox For Test Accuracy ResearchDocument5 pagesPRISMA-DTA For Abstracts: A New Addition To The Toolbox For Test Accuracy ResearchDEJEN TEGEGNENo ratings yet

- QUIPsDocument10 pagesQUIPsS.ANo ratings yet

- Cheklist 2016Document3 pagesCheklist 2016Ida Yustina FalahiNo ratings yet

- The CARE Guidelines - Consensus-Based Clinical Case Reporting Guideline DevelopmentDocument4 pagesThe CARE Guidelines - Consensus-Based Clinical Case Reporting Guideline DevelopmentInna SholichaNo ratings yet

- E013318 FullDocument25 pagesE013318 FullKarina Mejía EscobarNo ratings yet

- PRISMA 2020 Checklist: TitleDocument6 pagesPRISMA 2020 Checklist: TitleGlabela Christiana PandangoNo ratings yet

- E100046 FullDocument8 pagesE100046 FullweloveyouverymuchNo ratings yet

- Contoh ArtikelDocument6 pagesContoh ArtikelMilka Salma SolemanNo ratings yet

- CONSORT 2010 ChecklistDocument2 pagesCONSORT 2010 ChecklistReza Ishak EstikoNo ratings yet

- Research Methods & ReportingDocument1 pageResearch Methods & ReportingSergio LoaizaNo ratings yet

- CERTDocument10 pagesCERTalex ormazabalNo ratings yet

- Panduan Manuskrip KualitatifDocument2 pagesPanduan Manuskrip KualitatifNur HidayatNo ratings yet

- 2015SysRevsMoherPRISMAP StatementDocument10 pages2015SysRevsMoherPRISMAP StatementBharat TradersNo ratings yet

- Effectiveness of The Open Bite Treatment in Growing Children and Adolescents. A Systematic ReviewDocument14 pagesEffectiveness of The Open Bite Treatment in Growing Children and Adolescents. A Systematic Reviewhasan.abomohamedNo ratings yet

- Outpatient Appointment Systems in Healthcare - A Review of Optimization StudiesDocument32 pagesOutpatient Appointment Systems in Healthcare - A Review of Optimization Studiesgabrieelcrazy100% (1)

- The PRISMA Statement For Reporting Systematic ReviDocument39 pagesThe PRISMA Statement For Reporting Systematic RevirafafvuNo ratings yet

- CONSORT ChecklistDocument2 pagesCONSORT Checklistziana alawiyah75% (4)

- CERT Explanation and ElaborationDocument10 pagesCERT Explanation and ElaborationMaude GohierNo ratings yet

- Baccaglini Et Al 2010Document9 pagesBaccaglini Et Al 2010Amanda AiresNo ratings yet

- Normalization and Weighting The Open Challenge in LCADocument7 pagesNormalization and Weighting The Open Challenge in LCAdanielsmattosNo ratings yet

- Evidence Summaries Tailored To Health Policy-Makers in Low-And Middle-Income CountriesDocument8 pagesEvidence Summaries Tailored To Health Policy-Makers in Low-And Middle-Income Countriesapi-31366992No ratings yet

- The CONSORT Statement: ArticleDocument4 pagesThe CONSORT Statement: ArticleiikhsanhNo ratings yet

- Examiner Alignment and Assessment in Clinical Periodontal Researchhefti - Et - Al-2012-Periodontology - 2000Document20 pagesExaminer Alignment and Assessment in Clinical Periodontal Researchhefti - Et - Al-2012-Periodontology - 2000Dr. DeeptiNo ratings yet

- AGREE Reporting ChecklistDocument5 pagesAGREE Reporting ChecklistAngyP0% (1)

- CONSORT 2010 ChecklistDocument2 pagesCONSORT 2010 ChecklistPimlaphatmh SongNo ratings yet

- PRISMA For Abstracts PDFDocument13 pagesPRISMA For Abstracts PDFVirgínia MouraNo ratings yet

- Adler - Et - Al - (2014) The IPCC and Treatmentof Uncertainties Topics and Sourcesof DissensusDocument14 pagesAdler - Et - Al - (2014) The IPCC and Treatmentof Uncertainties Topics and Sourcesof DissensusRoberto LorenzoNo ratings yet

- CONSORT - Estudos in VitroDocument8 pagesCONSORT - Estudos in Vitroaka88No ratings yet

- Quality Assurance and Quality Control in Neutron Activation Analysis: A Guide to Practical ApproachesFrom EverandQuality Assurance and Quality Control in Neutron Activation Analysis: A Guide to Practical ApproachesNo ratings yet

- Guidelines For Reporting Outcomes in Trial Reports The CONSORT-Outcomes 2022 ExtensionDocument13 pagesGuidelines For Reporting Outcomes in Trial Reports The CONSORT-Outcomes 2022 ExtensionDaniel Vedovello FrungilloNo ratings yet

- 806 FullDocument3 pages806 FullMarli VitorinoNo ratings yet

- CONonSORT 2010 Explanation and Elaboration Updated Guidelines For Reporting Parallel Group Randomised TrialsDocument28 pagesCONonSORT 2010 Explanation and Elaboration Updated Guidelines For Reporting Parallel Group Randomised Trialsaisyah salsabilaNo ratings yet

- Research Methods & ReportingDocument28 pagesResearch Methods & ReportingRinawati UnissulaNo ratings yet

- Reference Intervals Current Status, Recent Developments and Future Considerations (2016)Document12 pagesReference Intervals Current Status, Recent Developments and Future Considerations (2016)Duy HoangNo ratings yet

- 1 s2.0 S1013905223002031 MainDocument9 pages1 s2.0 S1013905223002031 MainBethania Mria Bergamin MartinsNo ratings yet

- Goldacre - 2019 - COMPare A Prospective Cohort Study Correcting and Monitoring 58 Misreported Trials in Real TimeDocument16 pagesGoldacre - 2019 - COMPare A Prospective Cohort Study Correcting and Monitoring 58 Misreported Trials in Real TimeIvonneNo ratings yet

- 2020 - Dos - Santos - Et - Protocol Registration Improves Reporting Quality of Systematic Reviews in DentistryDocument8 pages2020 - Dos - Santos - Et - Protocol Registration Improves Reporting Quality of Systematic Reviews in DentistryJimmy TintinNo ratings yet

- Learning Curve Case StudyDocument31 pagesLearning Curve Case StudyRowena CahintongNo ratings yet

- A Guide To Establishing Event-Based SurveillanceDocument28 pagesA Guide To Establishing Event-Based SurveillanceAlirio BastidasNo ratings yet

- Standards For Public Health Information ServicesDocument54 pagesStandards For Public Health Information ServicesAlirio BastidasNo ratings yet

- Situational Awareness During Mass-Casualty Events: Command and ControlDocument1 pageSituational Awareness During Mass-Casualty Events: Command and ControlAlirio BastidasNo ratings yet

- Jamia: EditorialDocument2 pagesJamia: EditorialAlirio BastidasNo ratings yet

- Defining Community Acquired Pneumonia Severity On Presentation To Hospital: An International Derivation and Validation StudyDocument6 pagesDefining Community Acquired Pneumonia Severity On Presentation To Hospital: An International Derivation and Validation StudyAlirio BastidasNo ratings yet

- Michael S. Niederman Severe Pneumonia Lung Biology in Health and Disease, Volume 206Document450 pagesMichael S. Niederman Severe Pneumonia Lung Biology in Health and Disease, Volume 206Alirio Bastidas0% (1)

- Vlaidación ISAACDocument10 pagesVlaidación ISAACAlirio BastidasNo ratings yet

- Pole Nutrition Nitro Verge SHRED, 5 Lbs - The Fit Fuel Nutrition PDFDocument1 pagePole Nutrition Nitro Verge SHRED, 5 Lbs - The Fit Fuel Nutrition PDFRahul GuptaNo ratings yet

- Alternative Mode of Instruction For Physical EducationDocument5 pagesAlternative Mode of Instruction For Physical EducationAllan Gabriel LariosaNo ratings yet

- Dissertation Proposal TextDocument2 pagesDissertation Proposal TextJithin ThomasNo ratings yet

- Program Kerja Pkrs Baru 2022Document16 pagesProgram Kerja Pkrs Baru 2022physioterapyNo ratings yet

- Product: Acetaminophen (Usp) CODE: 106480: Section 01: Chemical Product and Company IdentificationDocument3 pagesProduct: Acetaminophen (Usp) CODE: 106480: Section 01: Chemical Product and Company IdentificationGuntur WibisonoNo ratings yet

- Solutions of Eco Therapy: General MetricsDocument3 pagesSolutions of Eco Therapy: General MetricsHaseem AjazNo ratings yet

- Jurnal Keputihan 1Document6 pagesJurnal Keputihan 1Muh AqwilNo ratings yet

- Lesson No.4 Food and Kitchen Safety: Wash HandsDocument5 pagesLesson No.4 Food and Kitchen Safety: Wash HandsAMORA ANTHONETHNo ratings yet

- Obamacare. The Pennsylvania State Nurses Association (PSNA), Representing More Than 217,000Document2 pagesObamacare. The Pennsylvania State Nurses Association (PSNA), Representing More Than 217,000Governor Tom WolfNo ratings yet

- Grossarth-Maticek, Eysenck - 1995 - Self-Regulation and Mortality From Cancer, Coronary Heart Disease, and Other Causes A Prospective STDocument15 pagesGrossarth-Maticek, Eysenck - 1995 - Self-Regulation and Mortality From Cancer, Coronary Heart Disease, and Other Causes A Prospective STMaría Reynel TarazonaNo ratings yet

- Main Findings: Gender Equality Index 2017Document56 pagesMain Findings: Gender Equality Index 2017Vesna27No ratings yet

- Bioceramics For Clinical Application in Regenerative DentistryDocument8 pagesBioceramics For Clinical Application in Regenerative DentistrypoojaNo ratings yet

- 10weekupperbodyforwomen PDFDocument1 page10weekupperbodyforwomen PDFStefania MirabelaNo ratings yet

- Frankenfoods? The Debate Over Genetically Modified CropsDocument4 pagesFrankenfoods? The Debate Over Genetically Modified CropsbobNo ratings yet

- Ban On Corporal Punishment in Schools in BhutanDocument2 pagesBan On Corporal Punishment in Schools in BhutanNorbuwangchukNo ratings yet

- Combustia EsofagianaDocument5 pagesCombustia EsofagianaM CarpNo ratings yet

- Literature Review On Protein Energy MalnutritionDocument8 pagesLiterature Review On Protein Energy Malnutritionafdttjujo100% (1)

- Nurse Student Exercise BookDocument16 pagesNurse Student Exercise BookA GNo ratings yet

- A Manual On Clinical Surgery 9th EditionDocument660 pagesA Manual On Clinical Surgery 9th EditionBandac Alexandra33% (3)

- BSWG English 3rd & 4th Semester (2021-2022)Document6 pagesBSWG English 3rd & 4th Semester (2021-2022)Ravi PandeyNo ratings yet

- Application Form For Medical ReimbursementDocument7 pagesApplication Form For Medical ReimbursementTravel IndiaNo ratings yet

- Critique On Bullying ArticlesDocument4 pagesCritique On Bullying ArticlesAi ÅiNo ratings yet

- Pamantasan NG Lungsod NG Valenzuela: College of Arts and Science Social Work DepartmentDocument3 pagesPamantasan NG Lungsod NG Valenzuela: College of Arts and Science Social Work DepartmentRonn SerranoNo ratings yet

- (De Gruyter Studies in Organization - 28) Gerald E. Caiden - Administrative Reform Comes of Age-De Gruyter (1991)Document360 pages(De Gruyter Studies in Organization - 28) Gerald E. Caiden - Administrative Reform Comes of Age-De Gruyter (1991)turnitin kuNo ratings yet

- Application:: Case Analysis. Read and Analyze The Given Case. Answer Each of The QuestionsDocument1 pageApplication:: Case Analysis. Read and Analyze The Given Case. Answer Each of The Questionsnikko canda100% (6)

- Đề & ĐA-Word FormationDocument10 pagesĐề & ĐA-Word FormationHà Thư LêNo ratings yet

- Cheung 2005Document7 pagesCheung 2005miranda gitawNo ratings yet

- 100 Women Who Care Charitable Organizations Database - November 18 20201916Document4 pages100 Women Who Care Charitable Organizations Database - November 18 20201916willbarry01No ratings yet

- The State of Mental Health in The Philippines PDFDocument4 pagesThe State of Mental Health in The Philippines PDFKatrina Francesca SooNo ratings yet

- The Wrong Answer: by Harold D. Foster, PHD © 2003Document6 pagesThe Wrong Answer: by Harold D. Foster, PHD © 2003JOSH USHERNo ratings yet