Professional Documents

Culture Documents

This Content Downloaded From 193.205.136.30 On Mon, 12 Apr 2021 20:08:18 UTC

Uploaded by

Daniela CirielloOriginal Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

This Content Downloaded From 193.205.136.30 On Mon, 12 Apr 2021 20:08:18 UTC

Uploaded by

Daniela CirielloCopyright:

Available Formats

The Sexual Arts of Ancient China as Described in a Manuscript of The Second Century

B.C.

Author(s): Donald Harper

Source: Harvard Journal of Asiatic Studies , Dec., 1987, Vol. 47, No. 2 (Dec., 1987), pp.

539-593

Published by: Harvard-Yenching Institute

Stable URL: https://www.jstor.org/stable/2719191

JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide

range of content in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and

facilitate new forms of scholarship. For more information about JSTOR, please contact support@jstor.org.

Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of the Terms & Conditions of Use, available at

https://about.jstor.org/terms

is collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve and extend access to Harvard Journal of

Asiatic Studies

This content downloaded from

193.205.136.30 on Mon, 12 Apr 2021 20:08:18 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

The Sexual Arts of Ancient China

as Described in a Manuscript of

the Second Century B.C.

DONALD HARPER

University of California, Berkeley

N addition to their interest in procreation and in satisfying

mutual desires between man and woman, the ancient Chinese re-

garded sexual relations as a vital part of the therapeutic arts of

physical cultivation. Along with breath cultivation, callisthenic exer-

cises, and dietetics, sexual intercourse was one of the methods for

"nurturing life" (yang sheng RI).' Literature on sexual practice

Much of the research for this article was done during my tenure as a Mellon Fellow in th

Department of Asian Languages, Stanford University, for whose support I am grateful. I

would also like to thank Dr. Li Hsiueh-ch'in 2* of the Institute of History, Chinese

Academy of Social Sciences, and Professor Ch'iu Hsi-kuei AX+ of Peking University for

guidance on matters related to the Ma-wang-tui ,%3EJ manuscripts while I was in Peking

during the summer, 1985.

Abbreviations:

HY Harvard-Yenching Index to the Taoist Canon, Tao tsang tzu muyin-te T i

(Peking, 1936). References are to the number of a text in the Canon as given on pp.

1-37.

KGS Yamada Keiji IEll , ed., Shin hakken Chuigoku kagakushi shiryo no kenkyti f r,

1S144t 40Rt (Kyoto: Ky6t6 Daigaku Jimbun Kagaku Kenkyuisho, 1985),

vol. 1 (Yakuchiu hen Xtr) and vol. 2 (Ronko hen )

PS Ma-wang-tui Han mu po shu A T Y :f%g, vol. 4 (Peking: Wen-wu Press, 1985).

SSCCS Juan Yuan IxdE, ed., Shih-san ching chu shu + ffiet (Taipei: 1-wen Press

reproduction of 1815 ed.).

Physical cultivation practices, as documented mainly in post-Han Taoist scriptures, have

been studied in a classic article by H. Maspero, "Les procedes de 'nourrir le principe vital'

dans la religion taoiste ancienne,"Journal Asiatique 229 (1937): 177-252 and 353-430 (pub-

lished in English in H. Maspero, Taoism and Chinese Religion, trans. F. Kierman [Amherst:

539

This content downloaded from

193.205.136.30 on Mon, 12 Apr 2021 20:08:18 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

540 DONALD HARPER

was classified under the rubric "intra-chamber" (fang chung N r4i) as

one of the four divisions of medical literature in the first century B.C.

catalogue of the royal Han library, coming just ahead of the

literature devoted to the attainment of "divine transcendence" (shen

hsien 1[4). None of the books recorded in these two divisions in the

Han shu M. bibliographic treatise are extant.2 Portions of Chinese

sex manuals which date perhaps from the Later Han and more

assuredly from the Six Dynasties have been preserved. These

sources indicate that the purpose of the sex manuals was principally

to describe the correct way to have intercourse-the way which

would result in general physical well-being-and to warn of the

dangers of indulging in careless sexual activity. Properly executed,

intercourse nurtured the body and promoted health; improperly ex-

ecuted, it led to disease and death.3 Sexual cultivation was also part

University of Massachusetts Press, 1981], pp. 446-554). Maspero also wrote on the pre-Han

yang sheng tradition in "Notes historiques sur les origines et le developpement de la religion

taoiste jusqu'aux Han," in Le Taoisme (Paris: Publications du Musee Guimet, 1950), pp.

201-18 (Taoism and Chinese Religion, pp. 413-26). For more recent studies of earlyyang sheng

theory and practice (as evidenced in Chuang tzu JW#, Lao tzu t#, Li shih ch'un ch'iu g ,

tk, Huai nan tzu dMiT, and other pre-Han and Han sources), see especially, Kusuyama

Haruki WWi 01 , Roshi densetsu no kenkyiu t;#fW . DiFI (Tokyo: S6bunsha, 1979), pp. 21-

67; and Sawada Takio f "Sen-Shin no y6seisetsu shiron: sono shiso to keifu" t

ODt q 9: -7c C , Nippon Chu-goku gakkai hi H * PPM *a 17 (1965): 19-

35. By Han times the various forms of physical cultivation were already incorporated into the

regimen for becoming a hsien 1Ll ("transcendent"). For a general treatment of sexual practice

within the context of ancient physical cultivation, see J. Needham, Science and Civilisation in

China, vol. 2 (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1956): 146-52; R. H. van Gulik, Sex-

ual Life in Ancient China (Leiden: E. J. Brill, 1961), pp. 35-47; and K. M. Schipper, "Science,

Magic, and the Mystique of the Body, " The Clouds and the Rain: the Art of Love in China, ed. M.

Beurdeley (London: Hammond and Hammond, 1969), pp. 14-20.

2 Han shu pu-chu AIM , (reproduction of 1900 woodblock ed., 1-wen Press,

30.80b-82a.

3 The main source for the fragments of the sex manuals is chapter 28 of the tenth ce

Japanese medical compendium Ishimpo WbiL'j (reproduction of the 1859 woodblock e

Tokyo: K6dansha, 1973). On the Ishimpo and its author, Tamba Yasuyori Pfg*m,

Gulik, Sexual Life, p. 122. The book was completed ca. 984 and circulated in manuscript form

until the nineteenth century. Ishihara Akira ;EJqJj, et al., Ishimpo: kan dai-n4ijhachi, bonai 9

,L't:+J-, t~ (Tokyo: Shibundo, 1970) is an annotated Japanese translation of

chapter 28 with illustrations and valuable appendices. This book is the basis for an English

translation of chapter 28 by Ishihara and Howard S. Levy, The Tao of Sex (New York: Harper

and Row, 1970).

The Su nui ching *, (Scripture of the Immaculate Maid) is regarded as the oldest of the

sex manuals quoted in the Ishimpo5 (see nn. 105-06 below) because of references to Su nu and

to a Su shu #- in connection with sexual arts in Later Han sources. Cf. van Gulik, Sexual

Life, pp. 70-79 and pp. 121-25; and Needham, Science 2:147-48.

This content downloaded from

193.205.136.30 on Mon, 12 Apr 2021 20:08:18 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

SEXUAL ARTS 541

of the program for spiritual transformation in Later Han and Six

Dynasties Taoist sects, and the teachings in certain scriptures docu-

ment early Taoist sexual practice.4

Documentation of the practices of physical cultivation in Warring

States and Ch'in-Han times has recently come to light in silk and

bamboo manuscripts discovered in tomb three at Ma-wang-tui .A17

a in Ch'ang-sha AJ:, Hunan (burial dated 168 B.C.). Among a cor-

pus of fifteen texts related to health and medicine, seven treat of the

ancient "nurturing life" practices. Sexual practice is detailed in

four of these texts, and this material undoubtedly exemplifies the

content of the literature classified as "intra-chamber" in the Han

shu bibliographic treatise. Two texts, both written on bamboo slips,

bear a particularly close resemblance to the later sex manuals in

style and content. The Chinese editors of the Ma-wang-tui medical

corpus have assigned the title "Ho Yin Yang" 1 (Conjoining

Yin and Yang) to the first text, and the title "T'ien hsia chih tao

t'an" WT-i="A (Discourse on the culminant way in Under Heav-

en) to the second. I judge them to be the oldest extant Chinese sex

manuals, and to represent the textual antecedents of the sex manu-

als that circulated in the Later Han and Six Dynasties periods.5

4 Although by Han times physical cultivation practices were observed assiduously by

adepts of the hsien longevity cult (and subsequently by Taoist adepts) as a way to realize the

transformation of their body and spirit, related practices for maintaining good health were in

more general use. With respect to sexual arts, both van Gulik, Sexual Life, pp. 78-79, and

Needham, Science 2:147, note the fact that the later sex manuals represented fundamental

ideas of sexual hygiene which could have been practiced by Taoists and non-Taoists alike.

The distinctive aspects of Taoist sexual cultivation have been noted by Schipper, "The

Taoist Body," History of Religions 17 (1978): 370-71, who distinguishes between intercourse

as a means for the male to cultivate his Yang vitality-the fundamental perspective of the sex

manuals-and the ultimate goal of the Taoist adept, which was to use intercourse as one way

for creating within himself a divine embryo from which the transcendent spirit would emerge.

In this act of sexual transformation, the Taoist male identified with the generative aspect of

feminine sexuality-not a role assumed by the male in the sex manuals (cf. Schipper,

"Science, Magic, and the Mystique of the Body," pp. 20-26). The Huang t'ing ching

(Scripture of the Yellow Court), probably second or third century A.D., is the oldest scripture

to treat of sexual cultivation in Taoism. I refer to the so-called "outer" scripture (Huang t'ing

wai chingyzu ching All E?f), not the later "inner" scripture (Huang t 'ing nei chingyui ching

X '3C41 e R) which was probably composed within the Shang ch'ing ? it sect of Taoism in

the fourth-sixth centuries. Cf. Maspero, "Procedes," pp. 237-39; Schipper, Concordance du

Houang-T'ing King (Paris: Ecole Fran~aise d'Extreme-Orient, 1975), pp. 2-11; and

Needham, Science 5.5 (1983): 83-85.

5 The seven "nurturing life" texts are described in greater detail below, pp. 545-59. For a

survey of the Ma-wang-tui medical corpus, see D. Harper, "The Wu Shih Erh Ping Fang:

This content downloaded from

193.205.136.30 on Mon, 12 Apr 2021 20:08:18 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

542 DONALD HARPER

In order to introduce the Ma-wang-tui sexological materials I pro-

pose to translate the first section from "Ho Yin Yang. " The first sec-

tion of this text serves as a prologue for the seven sections that

follow. It begins with a verse that uses cryptic metaphors to describe

the course of sexual union, and continues with a prose account of

the various technical procedures to be followed during intercourse,

such as the "ten postures" (shih chieh +t) and the "ten refine-

ments" (shih hsiu +fg). The subsequent sections of "Ho Yin Yang"

provide details concerning these procedures. "T'ien hsia chih tao

t'an" is also composed primarily of sections that list numerical

Translation and Prolegomena" (Ph.D. dissertation, University of California, Berkeley,

1982; University Microfilms International, Ann Arbor), pp. 2-42 (the dissertation is a

transcription and translation of a Ma-wang-tui text of recipes for treating various maladies,

assigned the title Wu-shih-erh ping fang Et~iJ-TW by the Chinese editors); Akira Akah

"Medical Manuscripts Found in Han-Tomb No. 3 at Ma-wang-tui," Sudhofs Archiv 63

(1979): 297-301; Yamada Keiji, "The Formation of the Huang-ti Nei-ching," Acta Asiatica

36 (1979): 67-89; and Paul U. Unschuld, "Die Bedeutung der Ma-wang-tui-Funde fur

chinesiche Medizin- und Pharmazie-geschichte, " Perspektiven der Pharmaziegeschichte: Festschrift

fur Rudolf Schmitz zum 65 Geburtstag, ed. P. Dilg (Graz: Akademische Druck- und Verlags-

anstalt, 1983), pp. 389-417. Other manuscripts were also recovered from the Ma-wang-tui

tomb, and transcriptions of all of the manuscripts are being prepared by scholars in China and

published by Wen-wu Press in Peking in the series Ma-wang-tui Han mu po shu (plates of

the original manuscripts are included in each volume and the transcriptions are annotated,

although the notes are not exhaustive). At present, three volumes in the series have been pub-

lished, the most recent being vol. 4 which contains the medical corpus (abbreviated PS in the

present article). For a general description of the tomb three burial (including the contents of

the other manuscripts), see Jeffrey K. Riegel, "A Summary of Some Recent Wenwu and

Kaogu Articles: Mawangdui Tombs Two and Three," Early China 1 (1975): 10-15. For a

summary of the first articles reporting on the medical corpus published in Wen-wu

K'ao-ku ~ti (including preliminary transcriptions of some texts), see D. Harper,

"Mawangdui Tomb Three: Documents, I. The Medical Texts," Early China 2 (1976): 68-

69. Some of the medical texts are published separately in Wu-shih-erh pingfang (Peking: Wen-

wu Press, 1979); and the journal Ma-wang-tui i shuyen-chiu chuan-k'an %, A741fil 1

(1980) and 2 (1981), published in Ch'ang-sha, also provides transcriptions of several medical

texts. The transcriptions and Japanese translations of Ma-wang-tui medical texts in vol. 1 of

KGS are based on the transcriptions published earlier (as is my dissertation on the recipe

manual Wu-shih-erh ping fang), not on those in PS. PS is the only publication to provide

photographs and transcriptions of all of the Ma-wang-tui medical texts, and future work on

the texts will be based on this edition (the thorough annotation in KGS is nonetheless ex-

tremely valuable).

It has been determined that some of the manuscripts were redacted before the end of the

third century B.C., making very plausible the speculation that in them we have recovered

literature on physical cultivation which documents the growth of "nurturing life" theory and

practice during the fourth-third centuries B.C.

This content downloaded from

193.205.136.30 on Mon, 12 Apr 2021 20:08:18 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

SEXUAL ARTS 543

procedures. The division of the sex act into a sequence of procedures,

each with its own numerical subdivisions, is characteristic of the

later sex manuals; and like the Ma-wang-tui texts the procedures

are presented under separate headings within the text. The Ma-

wang-tui texts demonstrate that this approach to intercourse and

this format for the sex manual originated in the ancient "nurturing

life" tradition.6

The interest in studying the first section of "Ho Yin Yang" does

not rest solely in its sexological content. The combination of poetic

and prosaic instructions is significant for the study of early esoteric

literature. The verse represents a form of didactic verse in which

teachings and techniques are encoded in cryptic metaphors which

may be understood only by one initiated in the secrets of a par-

ticular doctrine. There are numerous examples of this type of verse

in later Taoist and occult literature, but none as early as the second

century B.C. The analysis of the cryptic metaphors in "Ho Yin

Yang" reveals the importance of such language in the symbolic

theories of the "nurturing life" tradition as well as in the actual

practice of physical cultivation techniques.7 The use of verse and

metaphorical language within an esoteric tradition is evident in the

Lao tzu t9-T, and the question of the precise intent of that book

hinges on what the original frame of reference may have been. Han

commentaries interpret certain passages as constituting teachings

on physical cultivation. The examples of cryptic language and its ap-

plication in the Ma-wang-tui physical cultivation texts strengthen

the probability that the Lao tzu was an important guide to physical

cultivation in the ancient "nurturing life" tradition.8 The Kuan tzu

6 See the discussion of the format of the sex manuals below, pp. 580-81. The lack

evidence attesting to the existence of a technical sexual literature in the received literature

of the Warring States period has led some to regard the elaboration of sexual cultivation

techniques and the compilation of writings on sexual cultivation as a Han phenomenon (cf.

Schipper, "Science, Magic, and the Mystique of the Body," p. 14). This judgment must be

revised now that we have the Ma-wang-tui texts.

7 The Huang t 'ing ching is the oldest example of Taoist cryptic poetry composed in order

present teachings on meditation and physical cultivation (see p. 564 below). In addition to

those in the "Ho Yin Yang" verse, similar cryptic metaphors occur in other Ma-wang-tui

physical cultivation texts.

8 The "Ho shang kung" YRJ LL commentary to the Lao tzu (second century A.D.) inter

prets a number of lines in the text as referring to specific forms of physical cultivation (Ho

shang kung chu Lao tzu tao te ching ff [ Wu ch 'iu pei chai Lao tzu chick 'eng PR*$

This content downloaded from

193.205.136.30 on Mon, 12 Apr 2021 20:08:18 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

544 DONALD HARPER

9T, "Nei yeh" NV31 (Operat

which physical cultivation theory is couched in metaphorical verse.9

The sexual connotations of the metaphors in "Ho Yin Yang" also

provide insights on the use of the same terms in early prose and

poetry. For example, the term ch'eng k'uang *Xk ("receiving canis-

ter") occurs in "Ho Yin Yang," and I suspect that there are sexual

nuances in the use of the same term in the Shih ching poem

"Lu ming" 1EQ% (Deer cry).10

Before presenting the translation and analysis of the first section

of "Ho Yin Yang," I would like to briefly survey the whole collec-

tion of physical cultivation literature found at Ma-wang-tui. It will

be some time before scholars have been able to evaluate the full

significance of this literature for the history of Chinese hygienics.

However it is already evident that the Ma-wang-tui texts provide a

new footing for the study of this subject and of the aspects of ancient

spiritual and intellectual life affected by it.

W t9T%Z ed., Taipei: 1-wen Press]). While the exegesis in the "Hsiang erh" MM com

mentary treats the text mainly as a source of orthodox religious doctrine, it also gives

evidence of the significance of the Lao tzu for the practice of meditation and physical cultiva-

tion (Jao Tsung-i, A Study on Chang Tao-ling's Hsiang-er Commentary of Tao Te Ching [Hong

Kong: Tong Nam Publishers, 1956]; the commentary is thought to represent the ideas of the

Celestial Master sect of Taoism in the second century A.D.). Cf. Anna Seidel, La Divinisation

de Lao Tseu dans le Taoisme des Han (Paris: Ecole Frangaise d'Extreme-Orient, 1969), pp

79; and Isabelle Robinet, Les Commentaires du Tao To King (Paris: College de France, Institut

des Hautes Etudes Chinoises, 1977), pp. 24-48. Needham, Science 5.5:130-35, translates ex-

amples of the "Ho shang kung" commentary's interpretation of the Lao tzu as a guide to

physical cultivation. A number of passages in the Lao tzu were clearly written to present

physical cultivation theory, and the early commentaries probably preserve an exegetical tradi-

tion that dates to the time of the book's original composition. To cite one example, Lao tzu,

paragraph 6, on the ku shen @6 ("ravine spirit"), which is explained as a teaching onyan

shen ("nurturing the spirit")-specifically breath cultivation-in the "Ho shang kung" com-

mentary (cf. Robinet, Commentaires du Tao To King, p. 37, and n. 49 below). References to

paragraphs in the Lao tzu are to the Tao te ching ku pen p 'ien MAP*, edited by Fu

(HY665). The significance of the Lao tzu as a digest of knowledge about physical cultivation is

discussed further on pp. 561-63 below. The Ma-wang-tui manuscripts include two editions of

the Lao tzu, but neither edition has a commentary. See Ma-wang-tui Han mu po shu, vol. 1

(1980).

9 Kuan tzu (SPPY ed.), "Nei yeh" F1t, 16.1a-6b. On the nature of the "Nei yeh" as a

treatise on physical cultivation, see W. Allyn Rickett, Kuan-Tzu: A Repository of Early Chinese

Thought (Hong Kong: Hong Kong University Press, 1965), pp. 151-68. Its significance is

discussed further on pp. 561-63 below.

10 Shih ching (SSCCS ed.), "Lu ming" (Mao 161), 9B.2b. See pp. 571-72 below.

This content downloaded from

193.205.136.30 on Mon, 12 Apr 2021 20:08:18 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

SEXUAL ARTS 545

THE MA-WANG-TUI PHYSICAL CULTIVATION LITERATURE

Of the seven Ma-wang-tui texts related to physical cultivation

practices, four occur on two separate sheets of silk and three are writ-

ten on bamboo slips. Let me begin with the bamboo-slip texts,

which in addition to "Ho Yin Yang" and "T'ien hsia chih tao

t'an" include a third text assigned the title "Shih wen" +t (Ten

questions). Titles were assigned by the Chinese editors based on

some feature of each text: "Shih wen" contains ten interviews be-

tween esoteric teachers and rulers (from legendary antiquity down

to the late Warring States); the first line of "Ho Yin Yang" con-

tains these three words; and the words "T'ien hsia chih tao t'an"

are written on a separate slip within that text, where they serve as

the title for the major portion of the whole text.1" The bamboo slips

were discovered in a lacquer box together with the silk manuscripts.

The slips of "Shih wen" (101 slips in all) and "Ho Yin Yang" (thir-

ty-two slips) were found rolled into one bundle with "Shih wen" on

the inside.12 "T'ien hsia chih tao t'an" (fifty-six slips) was in a sec-

ond rolled bundle, on the outside of which were eleven wooden slips

with recipes for charms (assigned the title "Tsa chin fang" -T5).13

" References to the texts written on slips will be to the title of the text, the slip number

within the text, and the page of PS on which the "Transcription" (shih wen Mi.) may be

found; for the texts on silk, the column number within the text will be cited. The "Plates"

(t 'u pan ffiE) of the original texts in the front of PS may be consulted using the approp

slip or column numbers.

12 Because "Shih wen" and "Ho Yin Yang" were discovered in one bundle, the slip

numbers assigned to "Ho Yin Yang" follow consecutively from the last slip of "Shih wen."

PS, "Shih wen," slips 1-101, pp. 145-52; and "Ho Yin Yang," slips 102-33, pp. 155-56.

The slips of both "Shih wen" and "Ho Yin Yang" are about twenty-three cm. long; the

width of the " Shih wen" slips is about 0. 7 cm., while the width of the "Ho Yin Yang" slips is

about one cm. There remains some question as to whether all 133 slips were originally bound

into a single bookmat, or whether two separately bound texts were rolled into one bundle. PS,

p. 152, provides a diagram of the bundle of slips when they were first removed from the lac-

quer box.

13 The slip numbers assigned to "T'ien hsia chih tao t'an" follow consecutively from the

last slip of "Tsa chin fang." PS, "Tsa chin fang," slips 1-11, p. 159; and "T'ien hsia chih

tao t'an, " slips 12-67, pp. 163-67 (slip 17 contains the heading used in assigning the name to

the text). The eleven wooden slips of "Tsa chin fang" vary in length, the longest being about

twenty-three cm.; the width is not uniform along the length of each slip, but varies between

about one and 1.3 cm. The bamboo slips of "T'ien hsia chih tao t'an" are about twenty-eight

cm. long and 0.6 cm. wide. It is unlikely that wooden and bamboo slips of such varying

dimensions were originally bound together to form a single bookmat. PS, p. 160, provides a

This content downloaded from

193.205.136.30 on Mon, 12 Apr 2021 20:08:18 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

546 DONALD HARPER

Like "Ho Yin Yang," the other two bamboo-slip texts are divided

into sections and the section divisions are marked by means of a

large dot (e) placed at the head of the first slip of each section. In

"Shih wen" each interview constitutes a separate section. As noted

above, many of the sections in "T'ien hsia chih tao t'an" are

similar to "Ho Yin Yang."

The ten interviews in "Shih wen" reflect the didactic style of

Warring States rhetorical literature in which an interlocutor, ideally

a ruler, puts questions to a teacher. Among the rulers who solicit in-

struction on physical cultivation are the Yellow God A*, Yao A,

Yui A, and P'an Keng U)W; the teachers include Shun 9, Jung

Ch'eng ti, and P'eng Tsu Ift. The tenth interview is between

Wang Ch'i 3EW and King Chao of Ch'in *C3E (r. 306-251 B.C.),

making the mid-third century B.C. the terminus post quem for the

literature that may have been the source of the interviews in "Shih

wen. " )14 By Han times there existed a large body of esoteric

literature composed in this style, exemplified most clearly in the

received literature by the medical books associated with the Yellow

God."5 The same format is also used in the later sex manuals.

diagram of the appearance of the bundle of wooden and bamboo slips when they were first

removed from the lacquer box.

The first published transcription of the four texts, under the assigned title "Yang sheng

fang" LI)J, is Chou Shih-jung JXtji?, "Ch'ang-sha Ma-wang-tui san hao Han mu chu

chien 'Yang sheng fang' shih wen" :R'X'T itN'*I ' WZ, Ma-wang-tui i

shuyen-chiu chuan-k'an 2 (1981): 2-14. KGS 1:297-362, is a transcription andJapanese transla-

tion of the four texts based on the transcription published by Chou Shih-jung. My own

research on the four texts was also based on this transcription until PS became available in

1986. The transcription in PS (accompanied for the first time with plates of the original slips)

is more accurate than the earlier transcription, and will be the standard edition for future

research (even in the PS edition there remain questions regarding the identification of certain

word/graphs and the reconstructed sequence of slips in the texts).

14 The first eight interviews, which are set in mythological or early historical times, all

depict the interlocutor-ruler seeking advice from the teacher-sage. The ninth and tenth inter-

views, which are set in Warring States times, present a scenario typical of the rhetorical

custom of that time: the teacher obtains an interview with the ruler (the verb is chien Q), the

ruler asks for physical cultivation teachings, the teacher responds, and the ruler expresses his

satisfaction by declaring "excellent" (shan t) after each teaching is given.

Jung Ch'eng is the Yellow God's teacher in the fourth interview (PS, "Shih wen," slips

23-41, pp. 146-47); and Shun is Yao's in the fifth (PS, slips 42-47, p. 148). Both teacher-to-

patron pairs are acknowledged in early legends.

15 See Seidel, Divinisation, pp. 50-51, for discussion of the teacher-to-patron paradigm in

This content downloaded from

193.205.1fff:ffff:ffff:ffff on Thu, 01 Jan 1976 12:34:56 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

SEXUAL ARTS 547

Although interviews are not included in "Ho Yin Yang," the fact

that it was found together with "Shih wen" suggests that there was

an interrelationship between the two forms of presenting instruction

on physical cultivation."6 The "intra-chamber" division of the Han

shu bibliographic treatise lists a number of titles which include the

names of legendary adepts of sexual cultivation, for example: Jung

Ch'eng Yin tao VMU. (Way of the Yin of Jung Ch'eng), Yao Shun

Yin tao AW2. (Way of the Yin of Yao and Shun), T'ang P'an Keng

Yin tao MMCA (Way of the Yin of T'ang and P'an Keng), and

Huang ti san wang yang Yang fang A 3i7It (Recipes of the

Yellow God and the Three Kings for nurturing the Yang). It is pro-

bable that portions of these lost books were composed of the type of

didactic interview found in "Shih wen."''7 Both Jung Ch'eng and

P'eng Tsu are closely associated with physical cultivation arts,

especially the sexual arts, in later sources; their inclusion in "Shih

wen" provides us with the oldest examples of physical cultivation

teachings ascribed to them.18 Noticeably absent among the teachers

which the role of the Yellow God is regularly that of the inquisitive patron who seeks instruc-

tion in recondite techniques from esoteric teachers. The Huang ti nei ching XVF' 3 (Yello

God's inner scripture) is the classic example of this type of literature. In the first interview of

"Shih wen" (PS, "Shih wen," slips 1-7, p. 145), the Yellow God is taught by the Celestial

Master (i'ien shih IIi), the very title given to the Yellow God's teacher in the medical arts,

Ch'i Po A10 (see Huang ti nei ching su wen W [SPPYed.], "Shang ku t'ien chen lun"

)g=, 1. Ib). This is also the title with which the Yellow God honors a sagacious youngster

in Chuang tzu (SPPYed.), "Hsii Wu-kuei" f5f,, 8.14a. The title Celestial Master also had

great significance in the religious hierarchy of the Later Han Taoist movements (cf. Seidel,

Divinisation, pp. 74-84 and pp. 112-14).

16 The fragments of the Su na ching quoted in the Ishimpo consist mainly of the Yellow God

asking questions of the Immaculate Maid, his teacher in sexual technique. In PS, "T'ien hsia

chih tao t'an," slips 12-14, p. 163, there is an interview between the Yellow Spirit (Huang

shen X*; this name refers to the Yellow God, Huang ti) and the Spirit of the Left (Ts

TA ). We may speculate that in addition to the Ma-wang-tui sex manuals, other vers

sex manuals existed in the second century B.C. which gave greater prominence to didactic in-

terviews in combination with detailed passages on sexual procedures.

17 Han shu 30.80b-81a. In addition, four of the books listed in the "spiritual transcend-

ence" category of the bibliographic treatise bear the name of the Yellow God in their titles

and are probably similarly composed.

18 The account of Jung Ch'eng in the Lieh hsien chuan IJ1fW{ refers to his physical cul

tion arts, including sexual cultivation. See M. Kaltenmark, Le Lie-sien Tchouan (Peking:

Universite de Paris, Centre d'etudes sinologiques de Pekin, 1953), pp. 55-58. Kaltenmark

provides references to Jung Ch'eng's sexual arts in later sources. Maspero, "Procedes," p.

410, argues that the commentary to the Hou Han shu account of Leng Shou-kuang M

This content downloaded from

193.205.136.30 on Mon, 12 Apr 2021 20:08:18 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

548 DONALD HARPER

in "Shih wen" are the Immaculate Maid (Su nul *&) and the Dark

Maid (Hsiian nu A&), the Yellow God's instructresses in sexual

arts as evidenced in several Han literary sources and in a body of

eponymous sexual literature preserved among the fragments of the

later sex manuals.19

In theory and practice the sexual arts were an extension of the

techniques for the absorption of vapor (ch 'i A) and essence (chin

-the basic objective of all forms of ancient Chinese physical cultiva-

tion.20 In the practice of breath cultivation, external vapors were in-

n. 103 below) preserves a fuller description of Jung Ch'eng's sexual arts which was later ex-

purgated from the Lieh hsien chuan (he is followed by van Gulik, Sexual Life, p. 71; and

Needham, Science 5.5: 198). I agree with Kaltenmark's judgment that the lines in question are

the commentator's explanations and not part of the original Lieh hsien chuan text. P'eng Tsu's

arts of physical cultivation are also mentioned in the Lieh hsien chuan (Kaltenmark, Lie-sien

Tchouan, pp. 82-84), but not his skills in sexual cultivation. His knowledge of sexual arts is

noted several times in the Pao p'u tzu TRt * . See, for example, Pao p'u tzu (SPPY ed.),

yen" ; 13.3a, which quotes from a P'eng Tsu ching g?AM (Scripture of P'eng Tsu). H

sexual teachings also appear in the sex manuals quoted in the Ishimpo. For further references

to P'eng Tsu and sex, see van Gulik, Sexual Life, pp. 95-96, and Needham, Science 5.5: 187-

89. It is unlikely that the fragments of a P'eng Tsu literature mentioned by Needham and van

Gulik are pre-Han or Former Han in date. For fuller information on the accounts of P'eng

Tsu and on the P'eng Tsu ching that circulated in Six Dynasties times, see Sakade Yoshinobu

t&1?t4P1, "H6so densetsu to Hoso kei" 1 91 KGS 2:405-62.

19 See van Gulik, Sexual Lire, pp. 74-79, for discussion of the early lore about

maculate Maid, and for references to her, the Dark Maid, and a third Elected Maid (Ts'ai nii

K) as sex instructresses in Later Han and Six Dynasties sources. Books ascribed to th

maculate Maid and Dark Maid are listed in the Pao p 'u tzu along with those of P'eng Tsu and

Jung Ch'eng on physical cultivation arts (Pao p'u tzu, "Hsia lan" Et, 19.2b). The

bibliographic treatise of the Sui shu ` lists works which contain the sexual arts of the two in-

structresses (see n. 105 below). On the tradition that makes the Dark Maid the Yellow God's

instructress in the art of warfare, see Seidel, Divinisation, pp. 40-41. It has been noted that

women appear as the teachers of sexual arts to men in the earliest literature on the sexual

techniques of Western antiquity, and the possibility of a parallel with the Chinese genre has

been suggested (cf. Needham, Science 5.5:187). The absence of women among the teachers in

the Ma-wang-tui texts, and of books attributed to the Immaculate Maid or Dark Maid in the

Han shu bibliographic treatise, makes the conjecture of a parallel with the early Western sex-

ual literature appear unlikely (besides, the Greek and Roman literature teaches men sexual

pleasure, not sexual cultivation in the Chinese sense).

20 In translating ch 'i as "vapor" I am rendering its earliest and most literal meaning as

subtle stuff that manifests itself in clouds, rain, the steam which rises from sacrificial offer-

ings, and other such phenomena. In later cosmological and physiological theory, ch 'i retained

this sense of the vaporous matter that permeated the atmosphere, animating living organisms

when it became concentrated within them. The breath and the air one breathed were ch 'i. In

its earliest form, Chinese breath cultivation entailed the inhalation of the external ch 'i, which

was then circulated throughout the body and finally exhaled. Whether the body absorbed ch 'i

This content downloaded from

193.205.136.30 on Mon, 12 Apr 2021 20:08:18 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

SEXUAL ARTS 549

haled and then circulated through the body; in dietary observances,

the vaporous essence of foods or drugs served to vitalize the body;

and in sexual intercourse, the Yin essence of the woman strength-

ened the Yang essence of the man,who held onto this store of

essence through the practice of semen retention.2'

The techniques described in "Shih wen" include breath cultiva-

tion, dietetics, and sexual cultivation. In the fourth interview Jung

Ch'eng teaches the Yellow God how to achieve a physical form

which is one with the cosmos by practicing breath cultivation:22

through breath cultivation or through other methods, this "physiological" ch'i was concep-

tually identical to the ch 'i that permeated all things in the world. Depending on the context of

its occurrence in specific physical cultivation practices, I sometimes qualify ch 'i as "vaporous

breath," "sexual vapor," etc. According to early sources, ching ("seminal essence") is the

refined essence of ch'i, and a man's semen is one concrete manifestation of ching. The ubi-

quitous term ching ch 'i ", % in physical cultivation literature I render as "vaporous essence. "

When in describing physical cultivation theory I use terms such as "essence," "Yin and

Yang essences," "male and female essences," etc., all refer to the concept of ch'i and ching.

See Onozawa Seiichi ' ,f g , et al., Ki no shiso i, R, (Tokyo: T6ky6 Daigaku Shup-

pankai, 1978), for an excellent survey of ch 'i in traditional Chinese thought. Naturally, the

significance of ch 'i and ching is discussed passim in the writings of Maspero, Needham, and

van Gulik.

Kuan tzu, "Nei yeh," is perhaps the oldest extant treatise on the cultivation of ch'i and

ching. It is the locus classicus for the definition of ching as "refined ch'i" (ibid., 16.2b), and it

describes at length the cosmo-physiological aspects of cultivating ch 'i and ching. Prior to the

discovery of the Ma-wang-tui texts, the Warring States jade inscribed with a short teaching

on the technique for circulating ch'i inside the body (see p. 563 below) provided the oldest

documentation of an actual technique for cultivating ch 'i (as opposed to descriptions of ch 'i in

writings like the "Nei yeh").

21 I apply the term semen retention to the practices associated with huan chingpu nao

T6 ("returning the seminal essence and replenishing the brain"). The purpose of semen reten-

tion was for the man to obtain Yin essence from the woman while at the same time allowing

none of his sexually generated Yang essence (i.e. semen) to escape. He then vitalized his body

by retaining this sexual essence and circulating it. Needham, Science 5.5:197-201, discusses

semen retention in Chinese sexual practice; and on p. 199, n. d, he proposes the terms coitus

conservatus and coitus thesauratus for the two distinctive forms of semen retention. The former

refers to the man's retention of semen by withdrawing after female orgasm without permit-

ting himself to experience orgasm; the latter refers to the practice of pressing the urethra at

the moment of ejaculation so that the semen is not released, but rather is made to pass back

into his body. In Chinese theory the semen was believed to pass up the man's spinal column

to "replenish the brain" (the semen, that is semen as we know it in modern medical science,

actually is diverted into the bladder when the urethra is blocked in this way). It was also possi-

ble for the woman to realize the benefits of sexual cultivation. See p. 585, n. 116, and p. 591,

n. 142, below.

22 PS, "Shih wen," slips 23-32, pp. 146-47. The three passages selected for translation

below represent about half of the text of Jung Ch'eng's teaching, which continues through

This content downloaded from

193.205.136.30 on Mon, 12 Apr 2021 20:08:18 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

550 DONALD HARPER

If his lordship wishes to be long-lived then he must comply with and examine the

way of heaven and earth. The vapor of heaven is monthly exhausted and monthly

filled, thus it is able to live long. The vapor of earth during the year is cold and hot,

and the precipitous and the gentle complement one another,23 thus the earth en-

dures and does not deteriorate. His lordship must examine the intrinsic nature of

heaven and earth and put it into practice with his body.

A wondrous transformation occurs when the adept learns to culti-

vate the vaporous essence:

Essence and spirit overflow like a spring.

Suck in the sweet dew and have it accumulate.

Drink the blue-gem spring and numinous wine-pot and make

it circulate.

According to the Lao tzu, sweet dew (kan lu ttZ) is an exudate pro-

duced from the union of heaven and earth-one of nature's elixirs.

Jung Ch'eng's teaching shows the incorporation of this cosmic

essence into breath cultivation.24 With the terms blue-gem spring

(yao ch 'uan I7%) and numinous wine-pot (ling tsun St) we have e

amples of the cryptic metaphors characteristic of later Taoist and

occult literature. I would identify the blue-gem spring with the yu

ch'ih 31 ("jade pool") in Taoist physiology, which denoted the

reservoir of saliva under the tongue as well as the saliva stored

there. This saliva, a concentrate formed from the transformation of

inhaled vapor, was swallowed and circulated inside the body.

Regular cultivation ensured that this reservoir became an unfailing

source of vitalizing fluid for the body. The same practice appears to

slip 41 (I have not translated several lines which come in between the selected passages, but

within each passage the complete text is translated).

23 "The precipitous and the gentle complement one another" translates hsien i hsiang ch 'ii

J;t. In pre-Han and Han texts hsien i is used to refer to terrain (Shih chi t [reproduc-

tion of the Palace ed., 1-wen Press, Taipei], 71.8a), and also to circumstances of "peril or

ease" (Kuan tzu, "Ch'i fa" tit, 2.2a) or to conduct which is "devious or candid" (I

E, [SSCCS ed.], "Hsi tz'u shang" , 7.9a). For hsiang ch'i in the sense of "mutually

complement," see I ching, "Hsi tz'u hsia" T, 8.24b. The change of temperature over the

seasons and change of terrain across the earth represent the natural activity of the "vapor of

earth." By observing the action of the ch'i of heaven and earth, man learns to cultivate his

own ch'i.

24 Lao tzu, paragraph 32. There are abundant references to the descent of sweet dew as a

token of heaven's blessings in pre-Han and Han sources (see n. 93 for references in Han por-

tent and weft-text literature).

This content downloaded from

193.205.136.30 on Mon, 12 Apr 2021 20:08:18 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

SEXUAL ARTS 551

be referred to in Jung Ch'eng's teaching.25 I suspect that ling

tsun is synonymous with the term hsuian tsun A# ("dark wine-pot"),

which occurs in another passage concerning breath cultivation in

the first interview in "Shih wen. " Hsuian tsun is attested as the name

of a ritual eau de vie in pre-Han texts, a substance which Han com-

mentators identify as the liquid extracted from the moon by means

of reflecting pans. In "Shih wen" both ling tsun and hsuian tsun prob-

ably have the same denotation as the yao ch'uian and the Taoist yui

25 The termyao ch 'ien i 9-J ("blue-gem fore") is given as the name of the reservoir used

breath cultivation in PS, "T'ien hsia chih tao t'an," slip 47, p. 165, in a passage related to

sexual cultivation. The original graph foryao in "Shih wen" and "T'ien hsia chih tao t'an"

is M. The PS transcription proposes the reading Ai for "Shih wen" and J* for

chih tao t'an. " KGS 1:307 and 355, correctly gives the reading A for both occurren

The name "blue-gem spring" suggests the "blue-gem pool" (yao ch 'ih JiiMl) at Mount K'un-

lun where the Queen Mother of the West exchanged a toast with King Mu of the Chou (Mu

t'ien tzu chuan PXf [SPTK ed.], 3.15a). T'ang Taoist adepts also associated the myt

geography of K'un-lun with breath cultivation. Cf. E. H. Schafer, "Wu Yiin's 'Cantos on

Pacing the Void,' " HJAS 41.2 (1981): 405, n. 110, where Schafer explains the use of the

term pi chin ("cyan exudate") to denote the saliva as an allusion to the blue-gem pool at

K' un-lun.

Swallowing saliva was a regular part of the regimen of physical cultivation practiced by

Taoists. The terms "jade pool" or "jade spring" (yii ch'ian 3Ii 7) referred both to the area

beneath the adept's tongue and to the saliva that gathered there. Scriptural authority goes

back to the two Yellow Court scriptures. See Huang t'ing wai ching (HY 332), 1. la; and Huang

t'ing nei ching (HY331), 1.2a. The relevant text in the "outer" scripture is translated and ana-

lyzed in Maspero, "Procedes," pp. 241-42 (Maspero, however, does not emphasize that the

saliva is to be swallowed). Both sources indicate that consuming the saliva of the jade pool

lengthens one's life and prevents sickness. For discussion of the role of saliva ingestion in

Taoist practices see also, Needham, Science 5.5:150-51. The Ma-wang-tui physical cultiva-

tion texts show that saliva ingestion was already part of ancient "nurturing life" practices.

The term "jade spring" occurs in PS, "Shih wen," slip 18, p. 146. According to the

passage, sexual cultivation ensures that the "jade spring" does not become empty, so that

"maladies do not arise, and thus one is able to prolong life. " Another occurrence ofyii ch 'ian

in PS, "T'ien hsia chih tao t'an," slip 21, p. 163, is similar. It appears that in the Ma-wang-

tui physical cultivation texts the "blue-gem spring" is a metaphor for the reservoir of saliva

in the mouth (or the saliva itself), while the "jade spring" denotes yet another receptacle for

the collection of vital essences (including those generated in sexual intercourse). The idea that

the purpose of breath cultivation and sexual cultivation is the same (the absorption of vital

essences to rejuvenate the body), the nose and mouth being the focal point for the former ac-

tivity and the genitals for the latter, is suggested again in a passage from "Shih wen" which

recommends that the adept utilize "penile vapor" when breathing and eating (see n. 30

below). The doubling of breath cultivation with sexual cultivation was also characteristic of

later Taoist practices, and led to a doubling of metaphorical terminology for the receptacles

where the vital essences were stored (cf. Needham, Science 5.5:209-11, discussing the Pao p'u

tzu).

This content downloaded from

193.205.136.30 on Mon, 12 Apr 2021 20:08:18 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

552 DONALD HARPER

ch 'ih.26 Jung Ch'eng's teaching continues with concrete and detailed

instructions for the method of ingesting vapor:

The way for sucking in vapor:

It must be made to reach to the extremities,

So that essence is generated and not lacking,

Above and below are all essence,

Cold and warm are tranquilly generated.

The inhalation must be deep and long,

And the new vapor is easy to hold.

The lodged-inside vapor is that of agedness,

The new vapor is that of longevity.

One who is skilled at cultivating vapor,

Lets the lodged-inside vapor disperse at night,

And the new vapor gather at dawn,

Therewith to penetrate the nine apertures and fill the six

27

magazines.

Several lines laterJung Ch'eng states that the breath cultivation per-

formed at dawn should be done so that "stale vapor (ch'en ch'i M)

is daily expended and new vapor (hsin chi i T) is daily replen-

ished. " In the passage above, the word su M, literally "lodged over-

night, " is used to describe the stale residue of vapor which the adept

26 In the received literature both hisuan tsun and hsiian chiu 9; ("dark liquor") occur. Th

fact that hsuian tsun also denotes the numinous fluid, not simply the wine-pot which holds the

fluid, is discussed by Ch'en Ch'i-yu P** ap. the occurrence of hsiian tsun in Lu shih ch'un

ch'iu chiao shih . (Shanghai: Hsiieh lin Press, 1984), "Shih yin" Ai , 5.273. I have not

found references in the received literature for the association of the term with breath cultiva-

tion. In PS, "Shih wen," slip 5, p. 145, the "dark wine-pot" is generated when the vapor of

the "spirit wind" (shenfeng MRP) has been sucked into the mouth and stored in the heart. The

teaching continues: "Drink (the dark wine-pot), not exceeding five (swallows). The mouth in-

variably finds the taste sweet. Make it reach the five depositories, and the body then becomes

extremely quiescent. " The instruction to drink and circulate the dark wine-pot parallels the

use of the blue-gem spring and numinous wine-pot in Jung Ch'eng's teaching. In my judg-

ment, both passages are concerned with swallowing saliva.

27 According to ancient physiological theory, the six magazines (liufu Ale, ) were the int

nal zones of the body responsible for receiving, transmitting, and transforming vital essences.

Huang ti nei ching su wen, "Chin kuei chen yen lun" kfA JA 1.16a, identifies them as

(nominal correlates in Western physiology are given where applicable): tan t (gall bladder),

wei ' (stomach), ta ch'ang ;kC (large intestine), hsiao ch'ang I'Mj (small intestine), p'ang

kuang "K (bladder), and san chiao , ("three burners"). A listing of the liufu in the Han

shih waz chuan OJk,Y-, quoted in T'aip'ingyii lan tTP% (Peking: Chung-hua shu-chii

1960), 363.2b, givesyen hou OPP (gullet) instead of san chiao.

This content downloaded from

193.205.136.30 on Mon, 12 Apr 2021 20:08:18 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

SEXUAL ARTS 553

must expel before ingesting a fresh supply.28 That the world itself

went through a similar process of ingesting and expelling vapor was

believed in later Taoist breath cultivation theory. The day was divid-

ed into periods of living vapor (sheng ch 'i 4L%) and dead vapor (ssu

ch 'i KE%), which were the times when heaven and earth breathed in

and breathed out. The adept coordinated his breathing regimen

with the cycle of cosmic respiration. He ingested the living vapor

generated at the time of the cosmic inhalation and ejected the dead

vapor along with the expulsion of cosmic exhaust. Once again Jung

Ch'eng's teaching, which associates the cultivation of the breath

with the cycle of night and day, anticipates Taoist physical cultiva-

tion theories. 29

Jung Ch'eng's teaching concludes with further details regarding

the methods of ingesting vapor. In the other nine interviews esoteric

teachers instruct their interlocutors in a variety of physical cultiva-

tion methods. In the sixth interview P'eng Tsu praises the vitalizing

properties of semen, stating that "of human vapor, none can com-

pare with the essence of the penis (chuin ching WN)"; and he re

28 Chuang tzu, "K'o i" tM , 6. la, uses the phrase "spit out the old and ingest th

(t'u ku na hsin 0:f.3O-) to describe exhaling and inhaling in the practice of breath cult

(the passage criticises people who practice various forms of physical cultivation obsessively in

order to become long-lived like P'eng Tsu). Needham, Science 5.5:154, notes the proverbial

significance of this phrase in later literature on breath cultivation. Jung Ch'eng's teaching

does not describe the precise technique for exhaling the "lodged-inside" vapor. Dawn was re-

garded as the ideal time for breath cultivation (but not the only time; see n. 29 below), and I

suspect that letting the lodged-inside vapor "disperse at night" means that the adept is sup-

posed to exhale this vapor just as night is ending in preparation for ingesting new vapor at

dawn. The silk text on breath cultivation (see n. 36 below) states that there are harmful

vapors in the atmosphere which must be expelled before the adept ingests the beneficial

vapors. These harmful vapors are mentioned in Jung Ch'eng's teaching (slips 32-33, p. 147).

Presumably both exhaling the stale vapor from the body and expelling harmful vapors from

the air would have preceded any act of ingesting new vapor, whether at dawn or at other

designated times.

29 On the Taoist theories, see Maspero, "Procedes," pp. 354-61. One method divided the

day at midnight (making midnight to noon the time of the living vapor, and noon to midnight

the time of the dead vapor). Another treated the period from sunrise to sunset as the time of

the living vapor, and breath cultivation could be carried out at both sunrise and sunset. The

silk text on breath cultivation (see n. 36 below) describes ingesting vapor at both sunrise and

sunset; and Jung Ch'eng's teaching refers subsequently to performing breath cultivation at

daybreak, sunset, and midnight. The reference to letting the new vapor "gather at dawn" in

the part of Jung Ch'eng's teaching just quoted probably represents the ideal, the vapor of

dawn being regarded as the most potent.

This content downloaded from

193.205.136.30 on Mon, 12 Apr 2021 20:08:18 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

554 DONALD HARPER

mends that the adept draw upon his supply of "penile vapor" when

breathing and eating.30 Ideas that are related to later Taoist theories

(of the sort I have already discussed in Jung Ch'eng's teaching) oc-

cur throughout the "Shih wen" teachings. To mention only one,

P'eng Tsu refers to spiritual transformation as hsing chieh JfW

("release from the physical form")-a term attested in a Shih chi P

nd passage concerning the hsien cult which corresponds to the term

shih chieh PR ("release from the corpse") in Taoist writings.3" The

physical cultivation teachings in "Shih wen" also bear formal titles.

For example, the teaching on breath cultivation which the Celestial

Master (T'ien shih WM11) presents to the Yellow God is called the

"way of consuming spirit vapor" (shih shen ch 'i chih tao P#X}).32

Titles which include the term chieh Yin 1 ("coition with the

Yin") refer to sexual practice, as in the title of Ts'ao Ao's Ai

teaching: "way of coition with the Yin and cultivating spiritual

vapor" (chieh Yin chih shen ch/'i chih tao '

Several of the interviews in "Shih wen" contain textual parallels

with the sexological material in "Ho Yin Yang" and "T'ien hsia

chih tao t'an." The latter two texts will be discussed below and the

30 PS, "Shih wen," slips 48-5 1, p. 148. The passage describes a morning regimen in w

the potency of the semen serves to reinforce the vaporous breath. The result is "like the nur-

turing of the red infant (ch'ih tzu I;f)." P'eng Tsu's teaching is clearly related to Lao tzu

paragraph 55, in which the "red infant" is presented as the ideal of physical cultivation. The

Lao tzu cites the fact that the infant "does not yet know of the conjoining of female and male

and yet the penis rises (chiin tso f'i)" as a sign of the perfection of ching "seminal essence. "

31 PS, "Shih wen," slips 56-57, p. 148. The text states that those who are able to achieve

longevity through cultivation techniques eventually become a "spirit" (shen E), and "there-

fore they are able to be released from the physical form. " Subsequent lines describe the spirit

flight of the transformed adept. Although the word hsien "transcendent" does not occur in

the text, the reference to hsing chieh and the description of spirit flight are both indicative of the

spiritual goals of the hsien cult. Shih chi 28. lOb, mentions occult specialists at the time of Ch'in

shih huang ti * Q who possessed recipes "for the way of transcendence and for release

from the physical form and fluxed transformation" (hsien tao hsing chieh hsiao hua MgiW

IL). The commentary cites Fu Ch'ien #, (second century A.D.), who equates hsing chieh

with shih chieh Pg. For the Taoist adept, shih chieh marked the moment when the immortal

physique was perfected and the mortal body sloughed off, leaving behind a husk-like corpse

(or an object such as a sword or staff) as evidence of the adept's apotheosis. Cf. Maspero,

"Procedes," pp. 178-81; and Needham, Science 5.1 (1974): 294-304 (which details the

alchemical background of the shih chieh transformation).

32 PS, "Shih wen," slip 7, p. 145.

33 Ibid., slip 22, p. 146.

This content downloaded from

193.205.136.30 on Mon, 12 Apr 2021 20:08:18 UTCC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

SEXUAL ARTS 555

parallels between all three texts identified. It is worth noting now

that while there are many parallels in "Ho Yin Yang and "T'ien

hsia chih tao t'an," there are also significant differences between

the parallel passages. For example, the section on the shih hsiu "ten

refinements" in "Ho Yin Yang" corresponds generally to the pa tao

Ai- ("eight ways") in "T'ien hsia chih tao t'an," minus two. Yet

the differences are great enough to indicate that the texts do not

represent two versions of the same ur-text, and thus that they had in-

dependent origins in earlier literature on sexual cultivation.34

As for the eleven wooden slips of "Tsa chin fang," several of the

recipes provide instructions for preparing philters which can be

used to "obtain" (te M) or to "seduce" (mei W) the object of desire.

Perhaps this love magic accounts for "Tsa chin fang" being placed

together with "T'ien hsia chih tao t'an."35

Turning now to the texts on silk, the first sheet of silk contains a

text on breath cultivation and a chart with color illustrations of peo-

ple performing exercises. The breath cultivation text, assigned the ti-

tle "Ch'iieh ku shih ch'i" Mr-AX (Abstaining from grain and con-

suming vapor), details a macrobiotic technique in which the adept

eschews grains and other foodstuffs while instead ingesting subtle

34 PS, "Ho Yin Yang," slips 118-19, p. 156 (shih hsiu); and "T'ien hsia chih tao t'an,"

slip 46, p. 165 (pa tao). Both sections list the ways for the man to thrust his penis (see p. 588

below). "T'ien hsia chih tao t'an," slips 44-45, p. 165, contains a different list of shih hsiu, the

content of which is not related to penile movements. In addition to significant differences be-

tween shared content, "T'ien hsia chih tao t'an," slips 25-39, pp. 164-65, contains a lengthy

passage on the "eight benefits and seven detriments" (pa i ch 'i sun AlN-Lf) in sexual cu

tion that occurs nowhere else in the Ma-wang-tui physical cultivation texts. Sections on the

"eight benefits" and "seven detriments" in Ishimpo 28.19a-21b, attest to their importance in

the later sex manuals.

35 PS, "Tsa chin fang, " slip 11, p. 159, states that one may "obtain" one's object of desire

by placing the person's left eyebrow in liquor and drinking it. The word for "seduce" is writ-

ten wei A (*miwar) in the text, which should be read as homophonous mei X (*miar). The

phonological reconstructions are of archaic Chinese as given in B. Karlgren, Grammata Serica

Recensa (Stockholm: Museum of Far Eastern Antiquities, 1957). "Tsa chin fang," slip 7, p.

159, states that by drinking a potion of the ashes of dove-hen tail-feathers one can "seduce"

one's object of desire. These philters are similar to the "seduction drugs" (meiyao W) of

medieval times, recipes for which are preserved in Ishimpo 26.17b-21a, in the section

"Hsiang ai fang" +fl,kiJ (Recipes for mutual love). There are other types of char

chin fang"; for example, slip 6, p. 159, which states that one can defeat an adversary in litiga-

tion by writing down the person's name and inserting the name in one's shoe (thereby

magically trampling the person).

This content downloaded from

193.205.136.30 on Mon, 12 Apr 2021 20:08:18 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

556 DONALD HARPER

cosmic vapors. The names of these vapors, which vary with the

seasons, are found in the Ch'u tz'u VP and in fragments of a lost

Han opuscule on breath cultivation.36 The exercise chart, assigned

the title "Tao yin t'u" 4i 1 1 (Chart of guiding and conducting), il-

lustrates postures which were used in ancient taoyin. Taoyin exer-

cises constituted an external complement to the internal circulation

of vapor in breath cultivation. The names of exercises associated

with taoyin in pre-Han and Han sources appear among the captions

to the illustrations, for example the hsiung ching AM ("bear ram-

ble") and the niao shen ,1EP ("bird stretch"). Similar forms of

dietetics, breath cultivation, and exercise are found in later Taoist

literature.37 The silk sheet also contains a text describing the

"ducts" (mo T-R) that convey the ch 'i "vapor" through the bo

36 PS, "Ch'ueh ku shih ch'i," columns 1-9, p. 85. See Harper, "The Wu Shi

Fang," pp. 7-13, for further information on the silk texts (including references to transcrip-

tions and studies as of 1982). In addition to the two sheets of silk with texts related to physical

cultivation, there is a third sheet that contains the Wu-shih-erh pingfang and four other texts

related to physiology and therapy. Because the silk fabric was partly disintegrated, the state of

preservation varies from text to text (assignment of column numbers within a text is based on

extant text, meaning that in some places an unknown number of columns are missing from a

severely damaged portion). "Ch'iieh ku shih ch'i" describes a procedure for "abstention

from grain" in which the adept eats the herb shih wei gig ("stone leather"; genus Pyrrosia)

and inhales cosmic vapors. Many of the names of the vapors that are imbibed correspond to

those in the Ling-yang Tzu-ming ching RWf E, a lost work quoted by Wang I T- (se

century A.D.) in his commentary to the occurrence of the vapor names in Ch'u tz'u (SPPYed.),

"Yuan yu" AMA, 5.4a. For other fragments of the Ling-yang Tzu-ming ching, see Kaltemnark

Lie-sien Tchouan, pp. 183-87 (ap. the account of Ling-yang Tzu-ming). "Ch'uleh ku shih

ch'i" also identifies harmful vapors for each season that must be expelled before ingesting the

beneficial vapors (these harmful vapors are mentioned in Jung Ch'eng's teaching in "Shih

wen"; see n. 28 above). Chuang tzu, "Hsiao-yao yu" Lt& , 1.7a, describes spirit b

who do not eat the five grains, but instead "sip the wind and drink the dew"; such ideas were

put into practice in the macrobiotic techniques of the hsien cult. "Abstention from grain"

(also known as pi ku MR) as part of breath cultivation was also important in Taoism

Needham, Science 5.5:137 and passim).

37 PS, "Plates," pp. 49-52; and "Transcriptions," p. 95 (a table of the caption titles). A

full-size reproduction of the fragments of the chart, a reconstruction of it, and several

research essays, have been published separately in Anonymous, Tao yin t'u | I U (Peking

Wen-wu Press, 1979). The term Taoyin refers both to physical exercises and to the circulation

of vapor in the body (cf. Harper, "The Wu Shih Erh Ping Fang," p. 12 and n. 38). The bear

ramble and bird stretch are mentioned in connection with taoyin in the passage from Chuang

tzu, "K'o i," cited in n. 28 above. Aside from the captions, the chart does not provide any

written explanations of the exercises. However, newly discovered medical manuscripts from a

tomb at Chiang-ling aft in Hupei (burial dated ca. 180 B.C.) include one text on taoyin t

This content downloaded from

193.205.136.30 on Mon, 12 Apr 2021 20:08:18 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

SEXUAL ARTS 557

that form the basis for cauterization therapy. Perhaps this text is

included because of the importance of these same ducts for circulat-

ing the vapor in breath cultivation and in taoyin exercises.38

The second sheet of silk contains two collections of recipes, as-

signed the titles "Yang sheng fang" **LJ (Recipes for nurturing

life) and "Tsa liao fang" *W,ii (Recipes for various treatments).

To isolate only the recipes related to physical cultivation would hard-

ly do justice to the contents of these recipe manuals. Let me list a

few of the categories treated in each text. "Yang sheng fang" pro-

vides many recipes for nutritive tonics to increase one's physical

vigor.39 Among other recipes in the text are: recipes for enhancing

sexual potency,40 for making the paste of gecko (shou kung tF) and

describes exercises which may be depicted in the Ma-wang-tui chart. A transcription of this

text has not yet been published, but there is a brief description of it in Anonymous, "Chiang-

ling Chang-chia-shan Han chien kai-shu" iffiJ*L IN, Wen-wu 1985.1:13-14. On

Taoist taoyin arts, cf. Maspero, "Procedes," pp. 413-27; and Needham, Science 5.5:154-62.

38 It has been assigned the title "Yin Yang shih-l mo chiu ching i pen"

t; (Canon of the eleven Yin and Yang ducts, ed. B), and it is nearly identical with another

silk text which has been designated ed. A. The description of the mo "ducts" and cauteriza-

tion (chiu .) in the Ma-wang-tui medical manuscripts bears witness to an early stage in the

development of the physiological model for the circulation of ch 'i and blood described in the

Huang ti nei ching, where it forms the basis for acupuncture (acupuncture is not mentioned in

the Ma-wang-tui manuscripts). For discussion of the term mo in ancient Chinese medical

theory, see Lu Gwei-djen and Joseph Needham, Celestial Lancets: A History and Rationale of

Acupuncture and Moxa (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1980), p. 22 ff.; Paul U.

Unschuld, Medicine in China: A History of Ideas (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1985),

pp. 73-83; and Yamada Keiji LJ4FHJV , "Shinkyui to t6-eki no kigen" - L MACDL j,

KGS 2:63-73. Reference is made to the ducts several times in the Ma-wang-tui physical

cultivation texts (see n. 114 below). The role of the ducts in physical cultivation, and the

significance of the text on the ducts being placed alongside the Ma-wang-tui taoyin chart, are

discussed in Sakade Yoshinobu W[H-11P, "D6-in k6" iG|I, in Ikeda Suetoshi hakushi koki

kinen toyogaku ronshui t Ff *IJif?# (Hiroshima: Ikeda Suetoshi Hakushi

Koki Kinen Jigy6kai, 1980), pp. 225-39.

39 PS, "Yang sheng fang," columns 1-219 (and some additional text at the end), pp. 99-

119. One of the tonic recipes underscores the value of the egg in ancient dietetics (PS, col-

umns 35-36, p. 102): "Regularly in the morning break a chicken egg and put it into liquor.

Drink it before the meal. On the next day drink two eggs, and on the next after that drink

three. Then once again drink one, the next day drink two, and the next after that drink three.

Continue like this until you have used up forty-two eggs. It makes a person strong and

enhances the beauty of the complexion."

40 PS, columns 81-84, p. 107, is a recipe for a poultice which when applied to the penis

makes it "rear like a startled horse"; and columns 89-91, pp. 107-08, describe two other

preparations which are used during intercourse.

This content downloaded from

193.205.136.30 on Mon, 12 Apr 2021 20:08:18 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

558 DONALD HARPER

cinnabar used to detect illicit intercourse,4" for compounds which

are taken to increase one's speed on a journey,42 and for magic

charms to accomplish similar ends.43 "Yang sheng fang" also con-

tains one passage on sexological knowledge in which King T'ang is

the interlocutor and another in which the interlocutor is Yi.44

In addition to recipes for nutritive tonics, "Tsa liao fang" pro-

vides recipes for protecting oneself from the deadlyyu N and other

poisonous creatures, mostly by means of magic.45 There are also in-

structions for the burial of the placenta following the birth of a

child.46 Matters related to childbirth are further detailed in a third

41 PS, column 60, pp. 104-05. The two recipes given are similar to those in received

literature, e.g. Huai-nan wan pi shu iXf, quoted in T'aip 'ingyii lan 946.3a-b (ap. shou

kung "protector-of-the-palace"). It was believed that the paste left a mark on the woman

which vanished only if she engaged in intercourse.

42 pS, "Yang sheng fang," columns 172-88, p. 115.

43 PS, columns 189-96, p. 116. Three of the five recipes give incantations to be chanted

before departure, and the Pace of Yu (Yu pu r%+f) is performed in conjunction with two of

the incantations (this magical dance-step also appears in the recipe manual Wu-shih-erh ping

fang). For further information on the Pace of Yu in pre-Han and Han magico-religious tradi-

tion see Harper, "The Wu Shih Erh Ping Fang," pp. 98-101; and "A Chinese Demonography

of the Third Century B.C.," HJAS 45.2 (1985): 469-70 (and n. 25).

44 PS, "Yang sheng fang," columns 197-217, pp. 117-18. Both passages contain material

related to "Shih wen," "Ho Yin Yang," and "T'ien hsia chih tao t'an." Column 202 lists

several terms that denote parts of the female genitals; and following column 217, there is a

diagram of the female genitals with labels identifying the parts. Both sets of terms are in

fragmentary condition, but are clearly related to the twelve terms for parts of the genitals

listed in "T'ien hsia chih tao t'an," slips 59-60, p. 166. Some of the terms are identical with

those used in the later sex manuals, e.g. mai ch'ih O; ("wheat tooth") and ku shih VI

("grain kernel"). See Ishimpo28.10b-12a (sec. "Lin yul" MIM) and 14b-16a (sec. "Chiu fa"

A&it). Ishihara, Ishimpo, bonai, p. 267, gives a labeled diagram of the female genitals along

with modern identifications for the Chinese terms (see also Maspero, "Procedes," p. 384).

45 PS, "Tsa liao fang," columns 1-79, pp. 123-29. Columns 58-70, pp. 127-29, deal with

the yii and its harmful relatives. Shuo wen chieh tzu chu XAfQ;4tS (reproduction of 1872

woodblock ed., Shanghai: Ku-chi Press), 13A.58b-59a, describes theyui, also known by the

name tuan hu E ("short bow") and several other names, as resembling a turtle with thr

legs which mortally wounds people by shooting them with its ch 'i "vapor. " It was regarded as

a denizen of the South, and in column 69 an incantation identifies theyii as inhabiting Ching-

nan i1TI (i.e. Ch'u). We may surmise that it represented an everpresent hazard to the

residents of Ch'ang-sha in Han times. Edward H. Schafer, The Vermilion Bird (Berkeley: Uni-

versity of California Press, 1967), p. 111, notes that theyui was the "most feared of the bogies

of the south" among men of T'ang, and discusses some of the possible identifications for the

creature (or creatures) known as yi.

46 PS, "Tsa liao fang," columns 40-42, p. 126. The text refers to it as the "method for the

diagram on burying the placenta according to Yui's interment" (Yui ts'ang mai pao t'ufa &M

fl?li). The placenta must be cleansed, sealed in a clay jar, and properly buried, for any

This content downloaded from

193.205.136.30 on Mon, 12 Apr 2021 20:08:18 UTCC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

SEXUAL ARTS 559

text on the silk sheet, assigned the title "T'ai ch'an shu" A IF

(Book of the production of the fetus), which describes the growth

of the fetus and various methods for conceiving infants and deter-

mining their sex. The method for burying the placenta, oriented

in a specific direction determined by the date of birth, is illustrated

in a diagram in "T'ai ch'an shu."47

It should be evident from my survey that the seven texts I identify

as texts on physical cultivation-"Shih wen," "Ho Yin Yang,"

"T'ien hsia chih tao t'an," "Ch'iieh ku shih ch'i," "Tao yin t'u,"

"Yang sheng fang," "Tsa liao fang" -do not constitute an isolated

set of esoteric writings within the corpus of Ma-wang-tui medical

literature. That is, the particular concerns of "nurturing life"

theory appear to be integrated into the general field of health science

as it existed in the second century B.C. Inasmuch as the techniques

and recipes in the texts were surely put to use by their owner, the

study of this literature will prove invaluable in reconstructing a por-

trait of the spiritual and intellectual trends of the period. Given the

firm terminus ante quem of 168 B.C. (the date of the tomb three burial)

and the likelihood that the physical cultivation texts are redactions

of older texts, they provide unprecedented documentation of the

harm to the placenta affects the well-being of the infant. Further, the placenta must be buried

in a particular direction whose auspiciousness is determined by the month of birth. The

diagram in "T'ai ch'an shu" illustrates how to determine the correct direction for each of the

twelve months (see n. 47 below). Ishimpo 23.19a-b, cites a passage from the Ch'an ching &K

in which Yu teaches a mother how to bury the placenta so that her children will no longer die

in infancy. "Tsa liao fang" and the diagram in "T'ai ch'an shu," which is labeled "Yui

ts'ang, " attest to the antiquity of the legend associating Yu with the proper burial of the in-

fant's placenta.

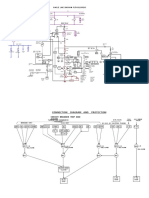

47 PS, "T'ai ch'an shu," pp. 133-39. A line drawing of the "Yui ts'ang" diagram is on p.

134. There is a box for each month, and within each box numbers are assigned to the twelve

directions. Certain directions are labeled ssu tE ("death"). According to "Tsa liao fang, " the

placenta should be buried in the direction with the highest number. Thus consulting both text

and diagram, the placenta of an infant born in the first month should be buried in the direc-

tion NNE 3/4 E, which is assigned the number 120 (while both ENE 3/4 N and E are labeled

ssu).

The written portion of "T'ai ch'an shu" is on columns 1-34, pp. 136-39. The growth of

the fetus over a ten month period is described in a teaching presented to Yu in columns 1-13.

The passage is remarkably similar to two seventh-century descriptions of gestation: Ch'ao

Yuian-fang's At7) Chu pingyuan hou lun MAMMA (Peking: Jen-min Wei-sheng Press,

1985), 41.1141-52 (sec. "Jen chen hou" AMR{f); and Sun Ssu-mo's , Ch'ien chinfang

-T!& (HY 1155), 2.18b-30a (sec. "Hsii Chih-ts'ai chu yuieh yang t'ai fang" ; X

n A f)

This content downloaded from

193.205.136.30 on Mon, 12 Apr 2021 20:0Jan 1976 12:34:56 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

560 DONALD HARPER

links between pre-Han "nurturing life" hygiene and the practices

of Taoist adepts. With respect specifically to the literature on sexual

arts, it is possible for the first time to identify with precision the pre-

Han origins of the theory and practice described in the later sex

manuals.

THE FIRST SECTION OF "HO YIN YANG"

The first line of the first section of "Ho Yin Yang" states that

what follows is a "recipe for whenever one will be conjoining Yin

and Yang." The enumeration of sexual procedures in "Ho Yin

Yang" does indeed provide a guide for accomplishing the sexual

union of feminine Yin and masculine Yang. While "T'ien hsia chih

tao t'an" contains similar information, it does not have the well-or-

dered organization of "Ho Yin Yang. " Neither do the references to

sexual procedures in the interviews of "Shih wen" summarize the

sex act from start to finish. Thus of the three bamboo-slip texts,

"Ho Yin Yang" offers the most concise yet thorough account of sex-

ual practice in the ancient "nurturing life" tradition.

The essentials of the technique are covered in the first section,

first in verse and then in prose. The subsequent seven sections of

"Ho Yin Yang" elaborate on procedures named in the prose

passage of the first section. The verse is composed mostly of rhym-

ing trisyllabic phrases-a monosyllabic verb followed by a bisyllabic

object-in which the verbs are hortatory and the objects designate

regions on the female body. The verse appears to teach the male

partner how to proceed with his mate from foreplay to penetration

and on to the final goal of sexual cultivation. These stages of inter-

course are also described in the prose passage, thus reiterating what

has already been conveyed in highly metaphorical poetry.

The use of poetry in "Ho Yin Yang" can be related generally to

the role of rhymed passages which occur throughout rhetorical and