Professional Documents

Culture Documents

COVID 19 Impact On Small Business

Uploaded by

Ginie Lyn RosalOriginal Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

COVID 19 Impact On Small Business

Uploaded by

Ginie Lyn RosalCopyright:

Available Formats

U.S.

SMALL BUSINESS ADMINISTRATION

Issue Brief REGULATION RESEARCH OUTREACH

Issue Brief Number 16

Release Date: March 2021

The Effects of the COVID-19 Pandemic on Small

Businesses

Daniel Wilmoth, Research Economist

Office of Advocacy, U.S. Small Business Administration

In March 2020, the COVID-19 pandemic arrived in the United States. Along with illness and death, the

pandemic brought widespread economic disruption. Businesses closed and unemployment surged to

levels not seen since the Great Depression. As Figure 1 shows, the number of people who were self-

employed and working was 20 percent lower in April 2020 than in April 2019.

This issue brief shows the effects of the COVID-19 pandemic on small businesses. While economic

damage was widespread, the severity varied substantially across locations, industries, and demographic

categories. Locations with larger declines included metropolitan and coastal areas. Industries with larger

declines included restaurants and taxi and limousine services. Differences by location and industry

contributed to differences across demographic categories, with larger declines for Asian and Black

business owners.

Data, methods, and limitations

Many popular sources of data on small businesses are released months or years after the periods they

describe. To provide an account of recent developments, this issue brief relies primarily on employment

data. Data on total employment by industry are available through the Current Employment Statistics

(CES) program and are combined here with 2017 data on the business size composition of industries from

the Statistics of US Businesses (SUSB).

Data on employment, location, industry, and demographic category are available through the Current

Population Survey (CPS). The CPS data analyzed here were accessed through IPUMS.1 One variable in

the data indicates if individuals were self-employed in their most recent job, while a second variable

indicates if individuals were still working at the time of the survey. Business owners who closed their

businesses were recorded as self-employed but not working if they had not obtained other employment

or as no longer self-employed if they had obtained a wage or salary position. Changes over time in the

number of people working and self-employed reflect declines from temporary closure and business

deaths and increases from reopening and business births.

The CPS data provide detailed descriptions of respondents that can be used to analyze specific groups,

such as self-employed individuals living in a particular metropolitan area. However, as the groups

become more specific, the samples become smaller, and the statistics noisier. Sample size was considered

in decisions about what statistics to present. However, the statistics presented still represent a wide

range of sample sizes, and the statistics representing less specific groups, such as the self-employed in

all metropolitan areas, are more precise than the statistics representing more specific groups, such the

self-employed in the New York City area.

Location

Figure 2 shows changes in the number of working self-employed people living inside and outside

metropolitan areas. In April 2020, the number of people in metropolitan areas who were working and

self-employed was 21 percent lower than in April 2019. Outside of those areas, the decline was only 13

percent. In subsequent months, the decline in metropolitan areas continued to exceed the decline outside

of metropolitan areas.

1

Flood, S., Miriam King, Renae Rodgers, Steven Ruggles and J. Robert Warren, Integrated Public Use Microdata

Series, Current Population Survey: Version 8.0. Minneapolis, MN: IPUMS, 2020.

Office of Advocacy Brief Number 16 Page 2 Release Date March 2021

Figure 3 shows declines for the three largest metropolitan areas in the United States. The New York City

area experienced a decline of 44 percent in April 2020. The Los Angeles area did not reach its nadir until

July 2020, with a decline of 36 percent. Like the New York City area, the Chicago area reached its nadir in

April 2020, but with a decline of only 16 percent.

The variations across metropolitan areas in Figure 3 reflect variations across regions. As Figure 4 shows,

the decline was most severe in the Northeast, substantial in the South and West, and least severe in the

Midwest. However, the declines for each of the large metropolitan areas in Figure 3 exceed the declines

for the surrounding regions.

Industry

The CES program reports total employment by industry supersector. Each disc in Figure 5 corresponds

to a different supersector. The vertical axis shows changes in supersector employment between April

2019 and April 2020. The horizontal axis shows the share of employment by small businesses before

Office of Advocacy Brief Number 16 Page 3 Release Date March 2021

the pandemic. The size of each disc corresponds the supersector share of total employment before the

pandemic.

Supersectors with large shares of employment at small businesses before the pandemic experienced large

decreases in employment. Leisure and hospitality had the largest decrease in employment, at 48 percent,

and had the third largest small business share, at 61 percent. Miscellaneous services had the largest small

business share, at 85 percent, and the third largest decrease in employment, at 22 percent.

Figure 6 shows a decomposition of the leisure and hospitality supersector into subsectors. The largest

subsectors were accommodation, accounting for 13 percent of supersector employment, and food services

and drinking places, accounting for 73 percent. Food services and drinking places had a high share of

employment at small businesses, at 64 percent, and a large decrease in employment, at 48 percent.

Although the initial employment decline for food services and drinking places was larger than the

decline for accomodation, food services and drinking places recovered more quickly than other leisure

and hospitality subsectors. Figure 7 shows that by November 2020 the decline for food services and

Office of Advocacy Brief Number 16 Page 4 Release Date March 2021

drinking places remained substantial, at 16 percent, but was significantly smaller than the decline for

accomodation, at 32 percent.

Owner demographics

Figure 8 shows variation across demographic groups in the effects of the pandemic on the self-employed.

The total number of people who were self-employed and working declined by 20.2 percent between

April 2019 and April 2020. The Hispanic group experienced a higher decline, at 26.0 percent. The highest

declines were experienced by the Asian and Black groups, with a decline of 37.1 percent for the Asian

group and 37.6 percent for the Black group.

Figure 9 shows how changes in the number of people self-employed and working varied over time

for the Asian group, the Black group, and everyone else. In the months following April 2020, impacts

continued to be larger for the Asian and Black groups. However, all three categories began to recover, and

Office of Advocacy Brief Number 16 Page 5 Release Date March 2021

differences across the groups generally decreased. The series for the Asian and Black groups are derived

from smaller samples and therefore include more random fluctuations.

Differences across demographic groups in the effects of the pandemic reflect the distributions of groups

across places. Asian and Black business owners were more highly concentrated in places with larger

declines. Before the pandemic, eight percent of the self-employed in metropolitan areas were Asian, and

eight percent were Black. Outside of metropolitan areas, one percent were Asian, and two percent were

Black.

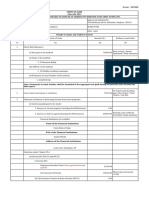

Table 1 shows several large metropolitan areas with severe declines and high concentrations of Asian

or Black business owners. Areas with severe declines and high concentrations of Asian owners included

Los Angeles, New York, and San Francisco. Areas with severe declines and high concentrations of Black

owners included Philadelphia, San Francisco, and Washington, DC.

Office of Advocacy Brief Number 16 Page 6 Release Date March 2021

Differences across demographic groups in the effects of the pandemic also reflect the distribution of

groups across industries. Asian and Black business owners were more highly concentrated in industries

with larger declines. Table 2 shows several industries with severe declines and high concentrations

of Asian or Black business owners. Industries with severe declines and high concentrations of Asian

owners included restaurants and specialized design services. Industries with severe declines and high

concentrations of Black owners included child daycare services and taxi and limousine services.2

The patterns in Tables 1 and 2 are related, because industry composition varies across locations. All of the

industries in Table 2 are concentrated in metropolitan areas.

Discussion

This analysis provides an early and partial account of the effects of the COVID-19 pandemic on small

businesses. Changes in the number of people who are self-employed and working reveal closures but

do not reveal which closures will become permanent. Data on self-employment provide only a partial

account of business activity. In the months and years to come, the release of additional data will enable

further analysis.

The effects of the COVID-19 pandemic are ongoing. While some businesses have largely recovered from

the initial decline, others continue to lag, and some recovered only to experience subsequent declines.

Future impacts of the pandemic, including whether business closures become permanent, will depend

in part on policy responses. The federal response has already included $525 billion3 in emergency funds

extended through the Paycheck Protection Program and $194 billion4 through the Economic Injury

Disaster Loan program, with an additional $284 billion5 in Paycheck Protection Program funds available.

2

For further analysis, see Fairlie, Robert W., The Impact of COVID-19 on Small Business Owners: Continued Losses the

Partial Rebound in May 2020. NBER Working Paper 27462, July 2020.

3

US Small Business Administration, Paycheck Protection Program (PPP) Report. August 8, 2020.

4

US Small Business Administration, Disaster Assistance Update Nationwide EIDL Loans. November 23, 2020.

5

US Small Business Administration, SBA and Treasury Announce PPP Re-Opening; Issue New Guidance. Press

Release Number 21-02, January 8, 2021.

Office of Advocacy Brief Number 16 Page 7 Release Date March 2021

In December 2020, the first vaccine was approved for use in the United States, bringing the end of the

pandemic in sight. However, the effects of the pandemic will continue long after it ends. The pandemic

changed patterns of consumption and forced businesses to find new ways of serving their customers.

Some businesses have died, some have been born, and many that survive will have been permanently

changed.

Office of Advocacy Brief Number 16 Page 8 Release Date March 2021

You might also like

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)From EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Rating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (98)

- Multiple ChoiceDocument1 pageMultiple ChoiceGinie Lyn RosalNo ratings yet

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeFrom EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (5795)

- Assignment No. 5 History 003Document4 pagesAssignment No. 5 History 003Ginie Lyn RosalNo ratings yet

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeFrom EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (537)

- 1-Spreadsheet Basics, Linking and Charts ExerciseDocument8 pages1-Spreadsheet Basics, Linking and Charts ExerciseGinie Lyn RosalNo ratings yet

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureFrom EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (474)

- History Assignment 4Document2 pagesHistory Assignment 4Ginie Lyn RosalNo ratings yet

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceFrom EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (588)

- Assignment 7 - RosalDocument4 pagesAssignment 7 - RosalGinie Lyn RosalNo ratings yet

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealFrom EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (74)

- Parental-Consent-Template - Copy - WPS PDF ConvertDocument1 pageParental-Consent-Template - Copy - WPS PDF ConvertGinie Lyn RosalNo ratings yet

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryFrom EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (231)

- Application Letter - WPS OfficeDocument1 pageApplication Letter - WPS OfficeGinie Lyn Rosal100% (1)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceFrom EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (895)

- ACT112.QS2 With AnswersDocument6 pagesACT112.QS2 With AnswersGinie Lyn Rosal89% (9)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItFrom EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (838)

- Jonnah Mae Q. Pinongpong: Ccts CardDocument1 pageJonnah Mae Q. Pinongpong: Ccts CardGinie Lyn RosalNo ratings yet

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingFrom EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (400)

- 112 ReconSeatworkDocument2 pages112 ReconSeatworkGinie Lyn RosalNo ratings yet

- June 2019 QPDocument20 pagesJune 2019 QPMengzhe XuNo ratings yet

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersFrom EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (345)

- Ofc-007 Employment Application For Ship PersonnelDocument5 pagesOfc-007 Employment Application For Ship PersonnelMoldoveanu Robert-AdrianNo ratings yet

- Group 11 - Section A - BRM Project Proposal - Premium HotelDocument9 pagesGroup 11 - Section A - BRM Project Proposal - Premium Hotelpeacock yadavNo ratings yet

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaFrom EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (45)

- Your Boarding PassDocument1 pageYour Boarding PassAbou Alela Mohamed50% (2)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnFrom EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (234)

- IT Return - FAST Builder - 2022Document3 pagesIT Return - FAST Builder - 2022Shakir MuhammadNo ratings yet

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyFrom EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (2259)

- Sole Proprietorship Final AccountDocument4 pagesSole Proprietorship Final Accountsujan BhandariNo ratings yet

- Unlocking Potentials of Hibiscus FlowerDocument7 pagesUnlocking Potentials of Hibiscus FlowerAli Abdoulaye100% (1)

- Module 6 - Layout DecisionsDocument40 pagesModule 6 - Layout DecisionsMuhammad FaisalNo ratings yet

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaFrom EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (266)

- Acco 20133 - Unit Iii & Iv - CreateDocument35 pagesAcco 20133 - Unit Iii & Iv - CreateHarvey AguilarNo ratings yet

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerFrom EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (271)

- 4 Case StudiesDocument4 pages4 Case StudiesAritra ChatterjeeNo ratings yet

- SS&CGTO - Intelligence WingDocument4 pagesSS&CGTO - Intelligence WingIrfan RazaNo ratings yet

- Excel Demo Diving Into PBIDocument135 pagesExcel Demo Diving Into PBIRahul ChauhanNo ratings yet

- Wallstreetjournal 20160115 The Wall Street JournalDocument55 pagesWallstreetjournal 20160115 The Wall Street JournalstefanoNo ratings yet

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreFrom EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (1090)

- Business Meetings - ESL Lesson PlanDocument5 pagesBusiness Meetings - ESL Lesson PlankamawoopiNo ratings yet

- Mercy Daviz Project Report Secretarial Audit RevisedDocument60 pagesMercy Daviz Project Report Secretarial Audit Revisedmercydaviz100% (1)

- A Study On Lifting of Corporate Veil With Reference To Case LawsDocument7 pagesA Study On Lifting of Corporate Veil With Reference To Case LawspriyaNo ratings yet

- Understanding Financial Statements, Taxes, and Cash Flows:, Prentice Hall, IncDocument50 pagesUnderstanding Financial Statements, Taxes, and Cash Flows:, Prentice Hall, IncYuslia Nandha Anasta SariNo ratings yet

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)From EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Rating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (121)

- Cover Letter FIRST GOOD DRAFT DLADocument1 pageCover Letter FIRST GOOD DRAFT DLAevelynbarthNo ratings yet

- Oneplus 9R - Arjun BhallaDocument1 pageOneplus 9R - Arjun BhallaRohan MarwahaNo ratings yet

- Chapt 25 Bonds PayableDocument124 pagesChapt 25 Bonds PayablelcNo ratings yet

- Directory - Database - List of Machinery & Equipment Manufacturers in India - 6th EditionDocument3 pagesDirectory - Database - List of Machinery & Equipment Manufacturers in India - 6th EditionJosh MathewsNo ratings yet

- The Procurement ProcessDocument83 pagesThe Procurement ProcessSean SinsuatNo ratings yet

- Types of Business OwnershipDocument27 pagesTypes of Business Ownershipmaria cacaoNo ratings yet

- Epsf Form12bb 903949Document2 pagesEpsf Form12bb 903949MALLA SAI YASWANTH REDDYNo ratings yet

- Emirates Ticket 1Document4 pagesEmirates Ticket 1jkhdaudhiNo ratings yet

- Week 2 The Vertical Boundaries of The Firm (Student)Document48 pagesWeek 2 The Vertical Boundaries of The Firm (Student)yenNo ratings yet

- F-IDS-PERD-010 APPLICATION FOR BOI REGISTRATION (BOI FORM 501) - AttachmentsDocument15 pagesF-IDS-PERD-010 APPLICATION FOR BOI REGISTRATION (BOI FORM 501) - AttachmentsAj IVNo ratings yet

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesFrom EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (821)

- Pages From Marx - Capital - Vol - 3Document2 pagesPages From Marx - Capital - Vol - 3Abelard BonaventuraNo ratings yet

- International Trade Law in Nigeria by IsochukwuDocument12 pagesInternational Trade Law in Nigeria by IsochukwuVite Researchers100% (1)

- Business Benefits InternationallyDocument6 pagesBusiness Benefits InternationallyDaiyang Melodias MohamadNo ratings yet