Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Apgar Scores: Examining The Long-Term Significance: Kristen S. Montgomery, PHD, RNC, Ibclc

Uploaded by

Anisa Nur AfiyahOriginal Description:

Original Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Apgar Scores: Examining The Long-Term Significance: Kristen S. Montgomery, PHD, RNC, Ibclc

Uploaded by

Anisa Nur AfiyahCopyright:

Available Formats

Apgar Scores: Examining the Long-term Significance

Kristen S. Montgomery, PhD, RNC, IBCLC

Abstract

KRISTEN S. MONTGOMERY is a recent doctoral graduate in The Apgar scoring system was intended as an evaluative

nursing at Case Western Reserve University in Cleveland, measure of a newborn’s condition at birth and of the

Ohio. She resides in Clinton Township, Michigan. need for immediate attention. In the most recent past,

individuals have unsuccessfully attempted to link Apgar

scores with long-term developmental outcomes. This

practice is not appropriate, as the Apgar score is cur-

rently defined. Expectant parents need to be aware of

the limitations of the Apgar score and its appropriate

uses.

Journal of Perinatal Education, 9(3), 5–9; Apgar

scores, newborn, birth, resuscitation.

Virginia Apgar, a physician and anesthesiologist, devel-

oped the Apgar scoring system in 1952 (Apgar, 1953)

to evaluate a newborn’s condition at birth. The Apgar

score is performed at 1 and 5 minutes of life. The purpose

of this paper is to discuss the appropriate use of the

Apgar score and to examine the appropriateness of using

the Apgar score to predict long-term developmental out-

comes.

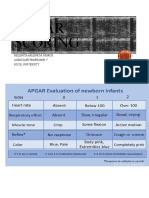

The Apgar scoring system is a comprehensive screen-

ing tool to evaluate a newborn’s condition at birth (see

Table 1). Newborn infants are evaluated based on five

variables: heart rate, respiratory effort, muscle tone, re-

flex irritability, and color. A numerical score of 0–2 is

assigned in each category for a maximum score of 10.

Apgar scoring is best used in conjunction with additional

evaluative techniques such as physical assessment and

vital signs.

In recent years, many researchers have attempted to

correlate Apgar scores with various outcomes including

development (Behnke et al., 1989; Blackman, 1988;

The Journal of Perinatal Education Vol. 9, No. 3, 2000 5

Apgar Scores: Examining the Long-term Significance

Table 1 The Apgar Scoring System (from Apgar, V., to support its use in predicting long-term outcomes.

1966) Please see Table 2 for clarification of selected research

Score terms.

Sign 0 1 2

Color Pale Blue Pink Body; Completely Pink . . . there is also little scientific evidence to support

Blue Extremities

Reflex Irritability None Grimace Vigorous Cry [the Apgar score’s] use in predicting long-term

Heart Rate Absent Slow (< 100) Above 100

outcomes.

Respiratory Effort Absent Slow (irregular) Crying

Muscle Tone Flaccid Some Flexion of Active Motion

Extremities

Score Status Review of the Literature

7–10 Normal According to the American Academy of Pediatrics’ Com-

4–6 Moderately Depressed mittee on Fetus and Newborn and the American College

0–3 Severely Depressed of Obstetricians and Gynecologists’ Committee on Ob-

stetric Practice (1996), the Apgar score should be used

to assess the condition of an infant at birth. These com-

Riehn, Petzold, Kuhlisch, & Distler, 1998), later delin- mittees also warn that the Apgar score should not be

quency (Gibson & Tibbetts, 1998), intelligence (Nel- used as the only measure to evaluate the possibility that

son & Ellenberg, 1981), and neurological development neurological damage occurred during the birthing pro-

(Sommerfelt, Pedersen, Ellertsen, & Markestad, 1996; cess. In addition to low Apgar scores (3 or less for longer

Wolf, M., Beunen, Casaer, & Wolf, B., 1998; Wolf, M.,

Beunen, Casaer, & Wolf, B., 1997; Wolf, M., Wolf, B.,

Bijleveld, Beunen, & Casaer, 1997) for the purposes of

Table 2 Glossary of Selected Research Terms

research. However, individuals have misinterpreted this

research and, in some instances, attempted to apply cau- Causal Relationship

A relationship between two variables such that the presence or

sality (i.e., that low Apgar scores caused later delin- absence of one variable (the ‘‘cause’’) determines the presence

quency or poor neurological outcomes). Causality has or absence, or value, of the other (the ‘‘effect’’).

been neither established nor a goal of the currently re- Correlation

ported research in this area. Research in this area has A tendency for variation in one variable to be related to variation

in another variable.

focused on establishing a correlation between these out-

Empirical Evidence

comes and an individual’s Apgar scores. The aim was Evidence that is rooted in objective reality and gathered through

not to demonstrate that low Apgar scores caused or the collection of data using one’s senses; used as the basis for

predicted these conditions; however, some individuals generating knowledge through the scientific approach.

have incorrectly interpreted the research as stating low Population

The entire set of individuals (or objects) having some common

Apgar scores could predict or actually caused certain characteristic(s) (e.g., all RNs in the state of California);

behaviors or deficits. Not only is this inappropriate use sometimes referred to as a universe.

of the Apgar score, there is also little scientific evidence Prediction

One of the aims of the scientific approach; the use of empirical

evidence to make forecasts about how variables of interest will

behave in a new setting and with different individuals.

Relationship

Apgar scoring is best used in conjuction with A bond or a connection between two or more variables.

additional evaluative techniques such as physical Variable

A characteristic or attribute of a person or object that varies

assessment and vital signs. (i.e., takes on different values) within the population under

study (e.g., body temperature, age, heart rate).

6 The Journal of Perinatal Education Vol. 9, No. 3, 2000

than 5 minutes), an infant who is asphyxiated prior to ranged from 36% to 100%, again heart rate having the

delivery would demonstrate severe metabolic or mixed highest rate of consistency. Heart rate measures likely

acidemia (pH < 7.00) via umbilical artery blood sample have greater consistency due to the ease of understanding

and additional neurological manifestations such as sei- and defining exactly what is being assessed. When consis-

zure activity, coma, hypotonia, and finally, evidence of tency scoring was compared between full-term and pre-

multiorgan dysfunction (Committee on Fetus and New- mature newborns, health care providers were found to

born, American Academy of Pediatrics, & Committee have better consistency when assessing full-term new-

on Obstetric Practice, American College of Obstetricians borns (Livingston, 1990). Additionally, full-term new-

and Gynecologists, 1996). Furthermore, research con- borns may represent the ‘‘normal’’ in health care

ducted over 30 years ago (Apgar, 1966; Apgar & James, provider’s minds; hence, full-term newborns may be

1962) provided initial evidence to disclaim the reliability more likely to receive a ‘‘normal’’ score, which accounts

of Apgar scores for predicting long-term outcomes of for the higher rate of consistency in term newborns than

any type (e.g., developmental and neurological). Predic- in preterm newborns.

tion of long-term outcomes was never a goal of the Apgar Another concern is determining who has responsibil-

scoring system. Rather, the goal was to make certain ity for assigning the Apgar score once the infant is born.

that infants were systematically observed for their need According to both Apgar (1966) and the Regan Report

for immediate care at birth. (1987), the person assisting with the delivery of the infant

should not assign the Apgar score. While in some respects

the delivering individual seems the most logical choice,

Reliability of Apgar Scores

bias may be introduced into the score value, because the

According to Jepson, Talashek, and Tichy (1991), the individual who attends the delivery may have a vested

Apgar score as a ‘‘tool’’ (to measure newborn adaptation interest in the outcome.

to extrauterine life) lacks sensitivity and specificity. Sensi- Secondly, the newborn may be given to additional

tivity measures how well the tool captures the infant’s personnel immediately after delivery. This makes de-

condition at birth (stable vs. depressed) and specificity termining the Apgar score considerably more difficult

refers to how well the tool measures the differences be- for the health care provider who is assisting the delivery,

tween the values of the scores (0–2 for each of the five necessitating leaving the mother’s bedside briefly to as-

categories). Additionally, various authors have noted sign the score. Additionally, if the infant remains with

that great variability exists in how individual health care the mother for the first 5 minutes of life, the health care

providers score the assessment (Clark & Hakanson, provider must later remember to document the score,

1988; Livingston, 1990). Clark and Hakanson (1988) often from memory. Both circumstances have the poten-

compared the consistency (inner-rater reliability) of tial to introduce further bias to the already poor consis-

Apgar scoring among various health care disciplines. In tency of the Apgar score.

their study, groups of health care providers were visually Often the nurse or someone from the department of

shown case presentations and then asked to assign Apgar neonatology assigns the Apgar score. Most frequently

scores to the infants who were presented. Pediatricians in a normal, full-term delivery, this would be the nurse.

and pediatric house staff had a consistency rating of Nurses, at least in the Clark and Hakanson (1988) study,

68%, obstetricians and obstetric house staff had a consis- had a poor consistency rate. Questions regarding the

tency rating of 46%, intensive care nursery staff had a accuracy of the Apgar score play a role in limiting the

consistency score of 42%, obstetric nurses 36%, and long-term predictive value.

community hospital nurses a consistency rating of 24%.

Livingston examined how consistent two health care

Intended Uses of the Apgar Score

providers were in assigning scores when compared to

one another. In this study, the consistency of scores As the Apgar score was developed and refined over the

ranged from 55% to 82% with heart rate having the years since its inception, the intended use has always

best rate of consistency at 82% for the 1-minute scores been the same: to evaluate a newborn’s condition at

(Livingston, 1990). For the 5-minute score, consistency birth. Some clinicians like to use the Apgar score as a

The Journal of Perinatal Education Vol. 9, No. 3, 2000 7

Apgar Scores: Examining the Long-term Significance

guide to their resuscitative efforts; however, this is not need for immediate attention. In the most recent past,

an intended use of the Apgar score. The novice prac- individuals have unsuccessfully attempted to link Apgar

titioner may mistakenly believe that resuscitative efforts scores with long-term developmental outcomes. This

should not begin until the 5-minute Apgar score is deter- practice is not appropriate as the Apgar score is currently

mined. Experienced clinicians realize this would severely defined. Expectant parents need to be aware of the limi-

delay resuscitative efforts and compromise the potential tations of the Apgar score and its appropriate uses.

for full recovery of neurological function. It is important

to be both careful and consistent with language.

Directions for Future Research

Educating the Public Future research is needed to increase the consistency

among health care providers assigning Apgar scores.

Letko (1996) notes that much of the public, especially This would take a training program and periodic practice

expectant parents, has some level of familiarity with the sessions to establish and maintain inner-rater reliability

Apgar score. However, as Letko also points out, many of each professional whose role is to assign the scores.

of these parents-to-be do not adequately understand the Enhanced consistency would be a first step to evaluating

score or its capacities for predicting long-term outcomes. the effectiveness of Apgar scores. At present, Apgar

Parents need to receive the appropriate education scores serve as a somewhat useful screening tool for

through the popular media, childbirth classes, and health health care providers to communicate with each other

care providers. It is imperative that parents have appro- about what a newborn’s status was like at birth and as

priate information so they are not disappointed when a mechanism to make certain that someone is systemati-

their child receives a score of 9, believing that their child cally observing the condition of the new infant.

is somehow inadequate because he or she did not receive

a score of 10. Parents need to understand that a score

from 7–10 indicates a normal newborn at birth and that Acknowledgement

it is rather infrequent for a newborn to receive a score

The author thanks Raquel Mayne, BSN, graduate of

of 10. For example, most infants have some level of

New York University Division of Nursing, for her assis-

blueness to their extremities and will not initially be

tance with article retrieval.

completely pink. This point can be covered when dis-

cussing the general appearance of a newborn. This

anticipatory guidance can assist the parents in their un- References

derstanding and promote a positive birthing experience,

by avoiding potential disappointment. Anonymous. (1996) Use and abuse of the Apgar score. Com-

mittee on Fetus and Newborn, American Academy of Pedi-

atrics, and Committee on Obstetric Practice, American

College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. Pediatrics, 1,

It is imperative that parents have appropriate 141–142.

information so they are not disappointed when their Apgar, V. (1953). A proposal for a new method of evaluation

of the newborn infant. Current Researches in Anesthesia

child receives a score of 9, believing that their child and Analgesia, 32, 260–267.

is somehow inadequate because he or she did not Apgar, V. (1966). The newborn scoring system: Reflections and

advice. Pediatric Clinics of North America, 113, 645–650.

receive a score of 10. Apgar, V., & James, L. (1962). Further observation of the

newborn scoring system. American Journal of Diseases of

Children, 104, 419–428.

Behnke, M., Eyler, F., Carter, R., Hardt, N., Cruz, A., &

Summary Resnick, M. (1989). Predictive value of Apgar scores for

developmental outcome in premature infants. American

The Apgar scoring system was intended as an evaluative Journal of Perinatology, 6, 18–21.

measure of a newborn’s condition at birth and of the Blackman, J. (1988). The value of Apgar scores in predicting

8 The Journal of Perinatal Education Vol. 9, No. 3, 2000

developmental outcome at age five. Journal of Perinatology, Fetal acidemia and neonatal encephalopathy. Zeitschrift fur

8, 206–210. Geburtshilfe und Neonatologie, 202, 187–191. (abstract).

Clark, D., & Hakanson, D. (1988). The inaccuracy of Apgar Sommerfelt, K., Pedersen, S., Ellertsen, B., & Markestad, T.

scoring. Journal of Perinatology, 8, 203–205. (1996). Transient dystonia in non-handicapped low-

Gibson, C., & Tibbetts, S. (1998). Interaction between mater- birthweight infants and later neurodevelopment. Acta Pae-

nal cigarette smoking and Apgar scores in predicting of- diatrica, 85, 1445–9.

fending behavior. Psychological Reports, 83, 579–586. . Watch those Apgar scores: Evidence. (1987).

Regan Report on Nursing Law, 27, 4.

Jepson, H., Talashek, M., & Tichy, A. (1991). The Apgar

score: Evolution, limitations, and scoring guidelines. Birth: Wolf, M., Beunen, G., Casaer, P., & Wolf, B. (1998). Neonatal

Issues in Perinatal Care, 18, 83–92. neurological examination as a predictor of neuromotor out-

come at 4 months in term low-Apgar-score babies in Zim-

Letko, M. (1996). Understanding the Apgar score. Journal

babwe. Early Human Development, 51, 179–186.

of Obstetrical, Gynecological, and Neonatal Nursing, 25,

Wolf, M., Beunen, G., Casaer, P., & Wolf, B. (1997). Neurolog-

299–303.

ical findings in neonates with low Apgar in Zimbabwe.

Livingston, J. (1990). Interrater reliability of the Apgar score European Journal of Obstetrics, Gynecology, & Reproduc-

in term and premature infants. Applied Nursing Research, tive Biology, 73, 115–119.

3, 164–165.

Wolf, M., Wolf, B., Bijleveld, C., Beunen, G., & Casaer, P.

Nelson, K., & Ellenberg, J. (1981). Apgar scores as predictors (1997). Neurodevelopmental outcome in babies with a low

of chronic neurologic disability. Pediatrics, 68, 36–44. Apgar score from Zimbabwe. Developmental Medicine &

Riehn, A., Petzold, C., Kuhlisch, E., & Distler, W. (1998). Child Neurology, 39, 821–826.

The Journal of Perinatal Education Vol. 9, No. 3, 2000 9

You might also like

- LSD Book PDFDocument878 pagesLSD Book PDFJeff Prager100% (7)

- The Basics: A Comprehensive Outline of Nursing School ContentFrom EverandThe Basics: A Comprehensive Outline of Nursing School ContentRating: 5 out of 5 stars5/5 (3)

- Caars Obser (S) Int.Document7 pagesCaars Obser (S) Int.Farida LarryNo ratings yet

- Tennis Elbow Exercises PDFDocument2 pagesTennis Elbow Exercises PDFalizzxNo ratings yet

- NCM 112 Lecture Module 4 Cellular AberrationDocument16 pagesNCM 112 Lecture Module 4 Cellular AberrationMeryville JacildoNo ratings yet

- Hops (Humulus lupulus): Monograph on a herb reputed to be medicinalFrom EverandHops (Humulus lupulus): Monograph on a herb reputed to be medicinalNo ratings yet

- Affidavit of Undertaking LsiDocument1 pageAffidavit of Undertaking LsiMary Cris Tamayo Arbuyes100% (3)

- CHN Top Rank Reviewer Summary by Resurreccion, Crystal Jade R.NDocument4 pagesCHN Top Rank Reviewer Summary by Resurreccion, Crystal Jade R.NJade SorongonNo ratings yet

- Micro Teaching TopicDocument11 pagesMicro Teaching TopicSiddula JyothsnaNo ratings yet

- APGAR Score and Ballard Score: K. C. JanakDocument41 pagesAPGAR Score and Ballard Score: K. C. JanakJanak Kc50% (2)

- Apgar ScoreDocument5 pagesApgar ScoreVania IhwanahNo ratings yet

- Neonatal Resuscitation and Adaptation Score Vs Apgar: Newborn Assessment and Predictive AbilityDocument7 pagesNeonatal Resuscitation and Adaptation Score Vs Apgar: Newborn Assessment and Predictive Abilityweni100% (1)

- It's Time To Reevaluate The Apgar ScoreDocument2 pagesIt's Time To Reevaluate The Apgar ScoreCandy RevolloNo ratings yet

- Art 2017963Document2 pagesArt 2017963Dias SeptariiaNo ratings yet

- ScoreDocument7 pagesScorefernin96No ratings yet

- APGAR Score - StatPearls - NCBI BookshelfDocument4 pagesAPGAR Score - StatPearls - NCBI BookshelfChiki CacaNo ratings yet

- The Apgar Score and Its Components in The Preterm Infant: PediatricsDocument7 pagesThe Apgar Score and Its Components in The Preterm Infant: PediatricsSepnitaYantiSitumeangNo ratings yet

- APGARDocument6 pagesAPGARPaola MoraNo ratings yet

- The Apgar Score: PediatricsDocument6 pagesThe Apgar Score: PediatricsDiana GarciaNo ratings yet

- Apgar Score 1Document4 pagesApgar Score 1punku1982No ratings yet

- Wiki Apgar Score01Document3 pagesWiki Apgar Score01Leevon ThomasNo ratings yet

- Journal Medicine: The New EnglandDocument5 pagesJournal Medicine: The New EnglandTillahNo ratings yet

- Five-Minute Apgar Score As A Marker For Developmental Vulnerability at 5 Years of AgeDocument7 pagesFive-Minute Apgar Score As A Marker For Developmental Vulnerability at 5 Years of AgePipit Dwi NurjayantiNo ratings yet

- Clinical Gestational Age Assessment in Newborns UsDocument5 pagesClinical Gestational Age Assessment in Newborns UsAchmad Teguh Fikri PratamaNo ratings yet

- Evaluation of Apgar Score in Neonates Born To Teenage MothersDocument4 pagesEvaluation of Apgar Score in Neonates Born To Teenage MothersMarlie SilmaroNo ratings yet

- Jurnal Apgar ScoreDocument4 pagesJurnal Apgar ScoreMaulidianaIndahNo ratings yet

- The APGAR Score and Infant MortalityDocument8 pagesThe APGAR Score and Infant MortalityOscar SanabriaNo ratings yet

- The Motor Control Assessment: An Instrument To Measure Motor Control in Physically Disabled ChildrenDocument5 pagesThe Motor Control Assessment: An Instrument To Measure Motor Control in Physically Disabled Childrennandhini raguNo ratings yet

- Apgar Scoring: Helenita Arlene M. Moros Associate Professor V Bicol UniversityDocument20 pagesApgar Scoring: Helenita Arlene M. Moros Associate Professor V Bicol UniversityAubrey MitraNo ratings yet

- 32 Weeks' Gestational Age Infants: An Open Label RandomizedDocument6 pages32 Weeks' Gestational Age Infants: An Open Label Randomizedsaigoptri5No ratings yet

- Apgar Score Components at 5 Minutes: Risks and Prediction of Neonatal MortalityDocument10 pagesApgar Score Components at 5 Minutes: Risks and Prediction of Neonatal MortalityAnggaNo ratings yet

- Neonatal Neurobehavioral Examination A NDocument7 pagesNeonatal Neurobehavioral Examination A NRheza NarwangsaNo ratings yet

- FMX 055Document6 pagesFMX 055BelleNo ratings yet

- ApgarDocument4 pagesApgarjaysille09100% (1)

- Tugas Pertemuan 2 Dan 3 AkbidDocument10 pagesTugas Pertemuan 2 Dan 3 AkbidRena Nana RenaNo ratings yet

- NCMA - 217A - Journal Reading - APGAR SCORING - : Name of Student: Neme Ñ O, Esther Cohlinne L. Level: BSN 2y 1-7Document2 pagesNCMA - 217A - Journal Reading - APGAR SCORING - : Name of Student: Neme Ñ O, Esther Cohlinne L. Level: BSN 2y 1-7LOMA, ABIGAIL JOY C.No ratings yet

- Acupressure and Preoperative Parental AnxietyDocument5 pagesAcupressure and Preoperative Parental AnxietyridaagustinaaNo ratings yet

- Alexandra P. DobellDocument11 pagesAlexandra P. DobellAlexPsrNo ratings yet

- Knowledge and Application of Apgar ScoreDocument5 pagesKnowledge and Application of Apgar Scorefebiola sihiteNo ratings yet

- gmTIMP CorrelationDocument7 pagesgmTIMP CorrelationArtur SalesNo ratings yet

- Electroencephalographic Characteristics in Preterm Infants Born With Intrauterine Growth Restriction 2014 The Journal of PediatricsDocument7 pagesElectroencephalographic Characteristics in Preterm Infants Born With Intrauterine Growth Restriction 2014 The Journal of PediatricsfujimeisterNo ratings yet

- The Active Movement Scale: An Evaluative Tool For Infants With Obstetrical Brachial Plexus PalsyDocument10 pagesThe Active Movement Scale: An Evaluative Tool For Infants With Obstetrical Brachial Plexus PalsyVale Rivas MartinezNo ratings yet

- Limitations of APGAR ScoringDocument2 pagesLimitations of APGAR ScoringFatima Llana TolentinoNo ratings yet

- Apgar ScoreDocument6 pagesApgar Score105070201111009No ratings yet

- Improving Neonatal Care by Advancing The Apgar ScoDocument1 pageImproving Neonatal Care by Advancing The Apgar ScoMor OB-GYNNo ratings yet

- Clinical Rating Scale For Head Control-A Pilot Study: December 2007Document7 pagesClinical Rating Scale For Head Control-A Pilot Study: December 2007pt.mahmoudNo ratings yet

- Research Article Skin-to-Skin Care by Mother vs. Father For Preterm Neonatal Pain: A Randomized Control Trial (ENVIRON Trial)Document6 pagesResearch Article Skin-to-Skin Care by Mother vs. Father For Preterm Neonatal Pain: A Randomized Control Trial (ENVIRON Trial)nadia kurniaNo ratings yet

- 9Document8 pages9jaya panchalNo ratings yet

- APGAR Written ExerciseDocument4 pagesAPGAR Written ExerciseJerald FernandezNo ratings yet

- Apgar Score AssignmentDocument7 pagesApgar Score AssignmentKpiebakyene Sr. MercyNo ratings yet

- SNAPPE-II Score For Neonatal Acute Physiology WithDocument3 pagesSNAPPE-II Score For Neonatal Acute Physiology WithwennyNo ratings yet

- Functional Assessment TestsDocument17 pagesFunctional Assessment TestsAlessa Dela CruzNo ratings yet

- Apgar ScoreDocument33 pagesApgar ScoredianavemNo ratings yet

- Psychometric Properties of The Pediatric Motor Activity Log Used For Children With Cerebral PalsyDocument9 pagesPsychometric Properties of The Pediatric Motor Activity Log Used For Children With Cerebral PalsyMaria DarribaNo ratings yet

- Aurora 2012Document7 pagesAurora 2012Phạm Văn HiệpNo ratings yet

- Systemic Effects of Perinatal Asphyxia: Editorial CommentaryDocument3 pagesSystemic Effects of Perinatal Asphyxia: Editorial CommentaryYasser AlghrafyNo ratings yet

- Agri 31 4 163 171Document9 pagesAgri 31 4 163 171Eray YüceelNo ratings yet

- A Comparison of Emergence Delirium Scales Following General Anesthesia in ChildrenDocument8 pagesA Comparison of Emergence Delirium Scales Following General Anesthesia in ChildrenNongnapat KettungmunNo ratings yet

- 472-Article Text-1092-1-10-20200520Document4 pages472-Article Text-1092-1-10-20200520asmita sainiNo ratings yet

- Stanford Sleepiness Scale - Pdf-PrevodDocument2 pagesStanford Sleepiness Scale - Pdf-PrevodSvetlana AndjelkovićNo ratings yet

- Apgar ScoreDocument5 pagesApgar ScorelakshmyNo ratings yet

- Possible Effect of Acupuncture in Autism Spectrum DisorderDocument3 pagesPossible Effect of Acupuncture in Autism Spectrum DisorderPaul NguyenNo ratings yet

- Orchidometer - Useful Office Practice Tool For Assessment of Male PubertyDocument7 pagesOrchidometer - Useful Office Practice Tool For Assessment of Male Pubertymichgirl90No ratings yet

- Effect-Of-Aspirin-On-Hypothalamic PSCDocument5 pagesEffect-Of-Aspirin-On-Hypothalamic PSCCaioNo ratings yet

- Sharma2011 Article GrowthAndNeurosensoryOutcomesODocument6 pagesSharma2011 Article GrowthAndNeurosensoryOutcomesOSayak ChowdhuryNo ratings yet

- Color Density Spectral Array For Early EvaluationDocument7 pagesColor Density Spectral Array For Early EvaluationMunna KendreNo ratings yet

- Population IssuesDocument17 pagesPopulation IssuesDennis RañonNo ratings yet

- Clinical Outcomes in A Specialist Male Genital Skin Clinic: Prospective Follow-Up of 600 PatientsDocument5 pagesClinical Outcomes in A Specialist Male Genital Skin Clinic: Prospective Follow-Up of 600 PatientsMeta SakinaNo ratings yet

- Soal Simulasi Ii PDFDocument8 pagesSoal Simulasi Ii PDFFarhan Fitrianto NugrohoNo ratings yet

- Hazardous Incidents RegisterDocument1 pageHazardous Incidents RegisterNitinNo ratings yet

- Hfle Dip EdDocument37 pagesHfle Dip EdKai Jo-hann BrightNo ratings yet

- Askep LukaDocument32 pagesAskep LukaMetha SusantiNo ratings yet

- Scribd 8Document2 pagesScribd 8Frejoles, Melva MaeNo ratings yet

- 9th Grade Final Exam: Study GuideDocument58 pages9th Grade Final Exam: Study GuideGa SunshineNo ratings yet

- Aloe Ferox Web BrochureDocument2 pagesAloe Ferox Web BrochureCHETAN DHOBLENo ratings yet

- Ta2 Speaking WritingDocument3 pagesTa2 Speaking Writingvohiep14122004No ratings yet

- HSP XYZ' Quality Policy Manual: DraftDocument5 pagesHSP XYZ' Quality Policy Manual: DraftHafizuddin HasniNo ratings yet

- Axis Traction Device For Delivery ForcepsDocument3 pagesAxis Traction Device For Delivery ForcepsRomeo Avecilla CabralNo ratings yet

- Of Malaya: Design and Analysis of Wudu' (Ablution) Workstation For Elderly in MalaysiaDocument70 pagesOf Malaya: Design and Analysis of Wudu' (Ablution) Workstation For Elderly in MalaysiaArchitect01 MYConstructionNo ratings yet

- Adapted Mentoring Coaching Precepting 2022 SVDocument9 pagesAdapted Mentoring Coaching Precepting 2022 SVapi-648595816No ratings yet

- Tracheostomy CareDocument7 pagesTracheostomy CareJoanna MayNo ratings yet

- 29 RT Kritikal Japan AffDocument120 pages29 RT Kritikal Japan AffEvan JackNo ratings yet

- MedicalandsocialaspectsDocument9 pagesMedicalandsocialaspectsTiti ArsenaliNo ratings yet

- Communication: Improving Patient Safety With SbarDocument7 pagesCommunication: Improving Patient Safety With Sbarria kartini panjaitanNo ratings yet

- Write Up CystDocument2 pagesWrite Up CystMinhwa KimNo ratings yet

- Lily Chu and David K Robinson: Industrial Choices For Protein Production by Large-Scale Cell CultureDocument8 pagesLily Chu and David K Robinson: Industrial Choices For Protein Production by Large-Scale Cell CultureCarina OliveiraNo ratings yet

- Ringkasan Promosi CCHC GT, CP & SR Nov 2023Document73 pagesRingkasan Promosi CCHC GT, CP & SR Nov 2023Adnin MonandaNo ratings yet

- Shape NejmDocument11 pagesShape NejmMicaela Cavii CaviglioneNo ratings yet

- Capstone Project: Rattanakorn Somchue Grade 11 Section 1106 Internship at Dentistry Department at Police General HospitalDocument15 pagesCapstone Project: Rattanakorn Somchue Grade 11 Section 1106 Internship at Dentistry Department at Police General Hospitalapi-514261788No ratings yet

- Admit CardDocument3 pagesAdmit CardSHUBHAM KANSARINo ratings yet