Professional Documents

Culture Documents

PERSPECTIVE AND TERMINOLOGIES OF PUBLIC PROJECTS (Module 7)

Uploaded by

Dwight Juther RafalOriginal Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

PERSPECTIVE AND TERMINOLOGIES OF PUBLIC PROJECTS (Module 7)

Uploaded by

Dwight Juther RafalCopyright:

Available Formats

ES 312b – Engineering Economy 1st Sem S.Y.

2020-2021

PERSPECTIVE AND TERMINOLOGIES OF PUBLIC PROJECTS

Introduction

Public projects are those authorized, financed, and operated by federal, state, or

local governmental agencies. Such public works are numerous, and although they may be

of any size, they are frequently much larger than private ventures. Since they require the

expenditure of capital, such projects are subject to the principles of engineering economy

with respect to their design, acquisition, and operation. Because they are public projects,

however, a number of important special factors exist that are not ordinarily found in

privately financed and operated businesses. The differences between public and private

projects are listed as follows.

Table 1. Some Basic Differences Between Privately Owned and Publicly Owned Projects

Private Public

Purpose Provide goods or services at a Protect health; protect lives

profit; maximize profit or and property;

minimize cost provide services (at no profit);

provide jobs

Sources of capital Private investors and lenders Taxation; private lenders

Method of financing Individual ownership; Direct payment of taxes;

partnerships; corporations loans without interest; loans

at low interest; self-

liquidating bonds; indirect

subsidies; guarantee of

private loans

Multiple purposes Moderate Common (e.g., reservoir

project for flood control,

electrical power generation,

irrigation, recreation,

education)

Project life Usually relatively short (5 to Usually relatively long (20 to

10 years) 60 years)

Relationship of Direct Indirect, or none

suppliers of capital

to project

Nature of benefits Monetary or relatively easy to Often nonmonetary, difficult

equate to monetary terms to quantify, difficult to equate

to monetary terms

Beneficiaries of Primarily, entity undertaking General public

Project project

Conflict of purposes Moderate Quite common (dam for flood

control versus environmental

preservation)

Conflict of interests Moderate Very common (between

agencies)

Effect of politics Little to moderate Frequent factors; short-term

tenure for decision makers;

pressure groups; financial

and residential restrictions;

etc.

Measurement of Rate of return on capital Very difficult; no direct

efficiency comparison with private

projects

Engr Alvin John R. Villanueva 1

ES 312b – Engineering Economy 1st Sem S.Y. 2020-2021

As a consequence of these differences, it is often difficult to make engineering

economy studies and investment decisions for public-works projects in exactly the same

manner as for privately owned projects. Different decision criteria are often used, which

creates problems for the public (who pays the bill), for those who must make the decisions,

and for those who must manage public-works projects.

Perspective and Terminology for Analyzing

Public Projects

In conducting an engineering economic analysis of any project, whether it is a

public or a private undertaking, the proper perspective is to consider the net benefits to

the owners of the enterprise considering the project. This process requires that the question

of who owns the project be addressed.

Project benefits are defined as the favorable consequences of the project to the

public, but project costs represent the monetary disbursement(s) required of the

government. It is entirely possible, however, for a project to have unfavorable

consequences to the public. The term disbenefits is generally used to represent the

negative consequences of a project to the public.

Self-Liquidating Projects

The term self-liquidating project is applied to a governmental project that is expected

to earn direct revenue sufficient to repay its cost in a specified period of time. Most of

these projects provide utility services—for example, the fresh water, electric power,

irrigation water, and sewage disposal provided by a hydroelectric dam. Other examples

of self-liquidating projects include toll bridges and highways.

Multiple-Purpose Projects

An important characteristic of public-sector projects is that many such projects

have multiple purposes or objectives. One example of this would be the construction of a

dam to create a reservoir on a river. This project would have multiple purposes: (1) assist

in flood control, (2) provide water for irrigation, (3) generate electric power, (4) provide

recreational facilities, and (5) provide drinking water.

Developing such a project to meet more than one objective ensures that greater overall

economy can be achieved. Because the construction of a dam involves very large sums of

capital and the use of a valuable natural resource—a river—it is likely that the project

could not be justified unless it served multiple purposes. This type of situation is generally

desirable, but, at the same time, it creates economic and managerial problems due to the

Engr Alvin John R. Villanueva 2

ES 312b – Engineering Economy 1st Sem S.Y. 2020-2021

overlapping utilization of facilities and the possibility of a conflict of interest between the

several purposes and the agencies involved.

Difficulties in Evaluating Public-Sector Projects

There are a number of difficulties inherent in public projects that must be considered in

conducting engineering economy studies and making economic decisions regarding those

projects. Some of these are as follows:

1. There is no profit standard to be used as a measure of financial effectiveness. Most

public projects are intended to be nonprofit.

2. The monetary impact of many of the benefits of public projects is difficult to quantify.

3. There may be little or no connection between the project and the public, which is the

owner of the project.

4. There is often strong political influence whenever public funds are used. When

decisions regarding public projects are made by elected officials who will soon be

seeking reelection, the immediate benefits and costs are stressed, often with little or no

consideration for the more important long-term consequences.

5. Public projects are usually much more subject to legal restrictions than are private

projects. For example, the area of operations for a municipally owned power company

may be restricted such that power can be sold only within the city limits, regardless of

whether a market for any excess capacity exists outside the city.

6. The ability of governmental bodies to obtain capital is much more restricted than that

of private enterprises.

7. The appropriate interest rate for discounting the benefits and costs of public projects is

often controversially and politically sensitive. Clearly, lower interest rates favor long-

term projects having major social or monetary benefits in the future. Higher interest

rates promote a short-term outlook whereby decisions are based mostly on initial

investments and immediate benefits.

What Interest Rate Should Be Used for Public Projects?

When public-sector projects are evaluated, interest rates∗ play the same role of

accounting for the time value of money as in the evaluation of projects in the private

sector. The rationale for the use of interest rates, however, is somewhat different. The

choice of an interest rate in the private sector is intended to lead directly to a selection of

projects to maximize profit or minimize cost. In the public sector, on the other hand,

projects are not usually intended as profit-making ventures. Instead, the goal is the

maximization of social benefits, assuming that these have been appropriately measured. The

choice of an interest rate in the public sector is intended to determine how available funds

should best be allocated among competing projects to achieve social goals.

Three main considerations bear on what interest rate to use in engineering

economy studies of public sector projects.

1. The interest rate on borrowed capital

2. The opportunity cost of capital to the governmental agency

3. The opportunity cost of capital to the taxpayers

As a general rule, it is appropriate to use the interest rate on borrowed capital as

the interest rate for cases in which money is borrowed specifically for the project(s) under

Engr Alvin John R. Villanueva 3

ES 312b – Engineering Economy 1st Sem S.Y. 2020-2021

consideration. For example, if municipal bonds are issued specifically for the financing of

a new school, the effective interest rate on those bonds should be the interest rate.

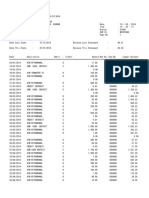

Figure 1. Relative Differences in Interest Rates for Governmental Agencies, Regulated Monopolies, and

Private Enterprises

For public-sector projects, the opportunity cost of capital to a governmental agency

encompasses the annual rate of benefit to either the constituency served by that agency or

the composite of taxpayers who will eventually pay for the project. If projects are selected

such that the estimated return (in terms of benefits) on all accepted projects is higher than

that on any of the rejected projects, then the interest rate used in economic analyses is that

associated with the best opportunity forgone.

If this process is done for all projects and investment capital available within a

governmental agency, the result is an opportunity cost of capital for that governmental agency.

A strong argument against this philosophy, however, is that the different funding levels

of the various agencies and the different nature of projects under the direction of each

agency would result in different interest rates for each of the agencies, even though they

all share a common primary source of funds—taxation of the public.

The third consideration—the opportunity cost of capital to the taxpayers—is based on the

philosophy that all government spending takes potential investment capital away from

the taxpayers. The taxpayers’ opportunity cost is generally greater than either the cost of

borrowed capital or the opportunity cost to governmental agencies, and there is a

compelling argument for applying the largest of these three rates as the interest rate for

evaluating public projects; it is not economically sound to take money away from a

taxpayer to invest in a government project yielding benefits at a rate less than what could

have been earned by that taxpayer.

Engr Alvin John R. Villanueva 4

You might also like

- Engineering Economics LECTURE 12-13: Huma Fawad Hitec, Taxila September 2015 - January 2016Document48 pagesEngineering Economics LECTURE 12-13: Huma Fawad Hitec, Taxila September 2015 - January 2016Raja Umair RaufNo ratings yet

- Glossary WASH Financing CourseDocument7 pagesGlossary WASH Financing CourseJhonny AguanesNo ratings yet

- Week 13Document5 pagesWeek 13Abrar AhmadNo ratings yet

- Bot Structures: What Is A BOT?Document8 pagesBot Structures: What Is A BOT?mhabeeb9127No ratings yet

- Large Project Financiers: Chapter 4: Who Finances Large Projects?Document33 pagesLarge Project Financiers: Chapter 4: Who Finances Large Projects?k bhargavNo ratings yet

- " F R E P ": Inancing The Enewable Nergy RojectsDocument6 pages" F R E P ": Inancing The Enewable Nergy Rojectsanjana meenaNo ratings yet

- 04+lecturer HUST Vietnam+DERISKINGDocument65 pages04+lecturer HUST Vietnam+DERISKINGTiên NguyễnNo ratings yet

- Using Project Finance To Fund Infrastructure InvestmentsDocument16 pagesUsing Project Finance To Fund Infrastructure InvestmentsThomasNo ratings yet

- Investment For African Development: Making It Happen: Nepad/Oecd Investment InitiativeDocument37 pagesInvestment For African Development: Making It Happen: Nepad/Oecd Investment InitiativeAngie_Monteagu_6929No ratings yet

- Construction FinanceDocument14 pagesConstruction FinanceReginaldNo ratings yet

- Chapter 1Document13 pagesChapter 1ibrahim JimaleNo ratings yet

- Lecture 12 - Handouts - Project FinanceDocument3 pagesLecture 12 - Handouts - Project FinanceXie DoNo ratings yet

- 005 An FundingDocument27 pages005 An Fundingapi-3705877No ratings yet

- Vaibhav Project ReportDocument51 pagesVaibhav Project Reportvaibhavsoni20No ratings yet

- Modeling Government Subsidies and Project Risk For Financially Non-Viable Build-Operate-Transfer (BOT) ProjectsDocument8 pagesModeling Government Subsidies and Project Risk For Financially Non-Viable Build-Operate-Transfer (BOT) ProjectsEko Putra SiburianNo ratings yet

- ECO 304 Lecture 1 2023Document31 pagesECO 304 Lecture 1 2023lubisithembinkosi4No ratings yet

- Mg611 - Engineering Project ViabilityDocument6 pagesMg611 - Engineering Project ViabilityIBRAHIM NYIRENDANo ratings yet

- PDI Complete SlidesDocument151 pagesPDI Complete SlidesAbrar AkmalNo ratings yet

- TET 407 - Energy Financing & TradingDocument31 pagesTET 407 - Energy Financing & TradingMonterez SalvanoNo ratings yet

- EDHEC 2023 Project Finance Course Intro. Lecture 1Document48 pagesEDHEC 2023 Project Finance Course Intro. Lecture 1Louis LagierNo ratings yet

- Project Finance 1 Network of Contracts PDFDocument41 pagesProject Finance 1 Network of Contracts PDFSam DhuriNo ratings yet

- Presentation PPP English SC Po - 2022 - 4Document25 pagesPresentation PPP English SC Po - 2022 - 4Rebeca CastiñeiraNo ratings yet

- Financing PPP ProjectsDocument42 pagesFinancing PPP ProjectsNikita Eunice Ndyagenda100% (1)

- Afdb PresentationDocument19 pagesAfdb PresentationMohamed ShedidNo ratings yet

- Project Finance - How It Works, Definition, and Types of LoansDocument7 pagesProject Finance - How It Works, Definition, and Types of LoansP H O E N I XNo ratings yet

- Infrastructure Finance: One Crore Ten CroreDocument38 pagesInfrastructure Finance: One Crore Ten Croreprashant456No ratings yet

- Class 6 Notes 04072022Document4 pagesClass 6 Notes 04072022Munyangoga BonaventureNo ratings yet

- Ce22 - 09 - Pem 3 PDFDocument27 pagesCe22 - 09 - Pem 3 PDFNathan TanNo ratings yet

- Project FinanceDocument63 pagesProject FinanceAdeel Ahmad100% (2)

- Topic 8d Infrastructure Projects ProcurementDocument29 pagesTopic 8d Infrastructure Projects Procurementmohammad hamizanNo ratings yet

- GX Ps Funding and Financing Smart Cities 20181Document74 pagesGX Ps Funding and Financing Smart Cities 20181Not So SenseLessNo ratings yet

- Public Private PartnershipDocument16 pagesPublic Private Partnershipsakib rony100% (1)

- (A4ID) Public-Private PartnershipDocument6 pages(A4ID) Public-Private PartnershipFathurohman OcimhNo ratings yet

- Lecture 9 18042020 051242pm 29112020 123126pm 31052022 095838amDocument23 pagesLecture 9 18042020 051242pm 29112020 123126pm 31052022 095838amSyeda Maira Batool100% (1)

- Chapter 5 EconomyDocument37 pagesChapter 5 EconomyAidi RedzaNo ratings yet

- Chapter-I: Basic Principles in Engineering Economics 1.1. Quantifying Alternatives For Easier Decision MakingDocument22 pagesChapter-I: Basic Principles in Engineering Economics 1.1. Quantifying Alternatives For Easier Decision MakingAli HassenNo ratings yet

- Financing and Investing in Infrastructure Week 1 SlidesDocument39 pagesFinancing and Investing in Infrastructure Week 1 SlidesNeindow Hassan YakubuNo ratings yet

- Credit Enhancement PracticesDocument30 pagesCredit Enhancement PracticesWondim TesfahunNo ratings yet

- 08 Torontoseminar SkinnerpaperDocument10 pages08 Torontoseminar Skinnerpapermita000No ratings yet

- Project Finance TrainingDocument62 pagesProject Finance Trainingjude loh wai sengNo ratings yet

- Chapter 1 Project Economics and Finance 2Document14 pagesChapter 1 Project Economics and Finance 2ENGINEER'S MINDSNo ratings yet

- Dalberg ChallengeDocument8 pagesDalberg ChallengeAbhishekNo ratings yet

- Advantages & Limitations of The Different Public Private Partnership RisksDocument52 pagesAdvantages & Limitations of The Different Public Private Partnership Riskscyrus dresselhausNo ratings yet

- Hidden ValueDocument3 pagesHidden ValueWilrose GorumbaNo ratings yet

- Chapter 1Document16 pagesChapter 1Alif MohammedNo ratings yet

- Chapter 1Document16 pagesChapter 1ልደቱ ገብረየስNo ratings yet

- Risk Gaps First Loss Protection MechanismsDocument16 pagesRisk Gaps First Loss Protection MechanismsMarius AngaraNo ratings yet

- Chapter 10Document28 pagesChapter 10fahad noumanNo ratings yet

- Greenbankworkshop For WebDocument100 pagesGreenbankworkshop For Webdineshjain11No ratings yet

- PAWCM PPT 3 - Principles of Project FinanceDocument44 pagesPAWCM PPT 3 - Principles of Project FinanceYashodhan JoshiNo ratings yet

- The Plus and Minus of Project Finance: by Barry N. Machlin and Brigette A. Rummel, Mayer Brown LLPDocument6 pagesThe Plus and Minus of Project Finance: by Barry N. Machlin and Brigette A. Rummel, Mayer Brown LLPJoão ÁlvaroNo ratings yet

- Project FinanceDocument3 pagesProject FinanceSonam GoyalNo ratings yet

- Chapter 1 Project Economics and FinanceDocument60 pagesChapter 1 Project Economics and FinanceENGINEER'S MINDSNo ratings yet

- What Is Public Private PartnershipDocument7 pagesWhat Is Public Private PartnershipShubham KumarNo ratings yet

- Electricity EconomicsDocument5 pagesElectricity Economicskennyajao08No ratings yet

- Summary Project Finance in Theory and PracticeDocument30 pagesSummary Project Finance in Theory and PracticeroseNo ratings yet

- Mohan Kumar G.: A Seminar byDocument39 pagesMohan Kumar G.: A Seminar byAnshul BhallaNo ratings yet

- MainPresentationMoldova PDFDocument159 pagesMainPresentationMoldova PDFMUKESH KUMARNo ratings yet

- Es 312B - Engineering Economy 1 Semester, S.Y. 2020-2021Document6 pagesEs 312B - Engineering Economy 1 Semester, S.Y. 2020-2021Dwight Juther RafalNo ratings yet

- The Benefit Cost Ratio (Module 8)Document5 pagesThe Benefit Cost Ratio (Module 8)Dwight Juther RafalNo ratings yet

- Inflation and Price ChangesDocument7 pagesInflation and Price ChangesDwight Juther RafalNo ratings yet

- Module 3Document34 pagesModule 3Dwight Juther RafalNo ratings yet

- Module 12Document10 pagesModule 12Dwight Juther RafalNo ratings yet

- Interest and Annuity TablesDocument19 pagesInterest and Annuity TablesDwight Juther RafalNo ratings yet

- ES 312b - Engineering Economy 1 Sem S.Y. 2020-2021Document2 pagesES 312b - Engineering Economy 1 Sem S.Y. 2020-2021Dwight Juther RafalNo ratings yet

- Module 2Document8 pagesModule 2Dwight Juther RafalNo ratings yet

- V Series: Three Wheel, Counterbalanced Lift TruckDocument126 pagesV Series: Three Wheel, Counterbalanced Lift TruckВиктор МушкинNo ratings yet

- Data Book: Automotive TechnicalDocument1 pageData Book: Automotive TechnicalDima DovgheiNo ratings yet

- Is.14785.2000 - Coast Down Test PDFDocument12 pagesIs.14785.2000 - Coast Down Test PDFVenkata NarayanaNo ratings yet

- Gis Tabels 2014 15Document24 pagesGis Tabels 2014 15seprwglNo ratings yet

- Installation and User's Guide For AIX Operating SystemDocument127 pagesInstallation and User's Guide For AIX Operating SystemPeter KidiavaiNo ratings yet

- Data Mining - Exercise 2Document30 pagesData Mining - Exercise 2Kiều Trần Nguyễn DiễmNo ratings yet

- Syed Hamid Kazmi - CVDocument2 pagesSyed Hamid Kazmi - CVHamid KazmiNo ratings yet

- ISP Flash Microcontroller Programmer Ver 3.0: M Asim KhanDocument4 pagesISP Flash Microcontroller Programmer Ver 3.0: M Asim KhanSrđan PavićNo ratings yet

- Bismillah SpeechDocument2 pagesBismillah SpeechanggiNo ratings yet

- Pthread TutorialDocument26 pagesPthread Tutorialapi-3754827No ratings yet

- AutoCAD Dinamicki Blokovi Tutorijal PDFDocument18 pagesAutoCAD Dinamicki Blokovi Tutorijal PDFMilan JovicicNo ratings yet

- Marley Product Catalogue Brochure Grease TrapsDocument1 pageMarley Product Catalogue Brochure Grease TrapsKushalKallychurnNo ratings yet

- RCC Design of Toe-Slab: Input DataDocument2 pagesRCC Design of Toe-Slab: Input DataAnkitaNo ratings yet

- Powerpoint Presentation R.A 7877 - Anti Sexual Harassment ActDocument14 pagesPowerpoint Presentation R.A 7877 - Anti Sexual Harassment ActApple100% (1)

- Rehabilitation and Retrofitting of Structurs Question PapersDocument4 pagesRehabilitation and Retrofitting of Structurs Question PapersYaswanthGorantlaNo ratings yet

- Vicente, Vieyah Angela A.-HG-G11-Q4-Mod-9Document10 pagesVicente, Vieyah Angela A.-HG-G11-Q4-Mod-9Vieyah Angela VicenteNo ratings yet

- Safety Data Sheet: Fumaric AcidDocument9 pagesSafety Data Sheet: Fumaric AcidStephen StantonNo ratings yet

- Belimo Fire & Smoke Damper ActuatorsDocument16 pagesBelimo Fire & Smoke Damper ActuatorsSrikanth TagoreNo ratings yet

- Bank Statement SampleDocument6 pagesBank Statement SampleRovern Keith Oro CuencaNo ratings yet

- Design & Construction of New River Bridge On Mula RiverDocument133 pagesDesign & Construction of New River Bridge On Mula RiverJalal TamboliNo ratings yet

- Econ 1006 Summary Notes 1Document24 pagesEcon 1006 Summary Notes 1KulehNo ratings yet

- C Sharp Logical TestDocument6 pagesC Sharp Logical TestBogor0251No ratings yet

- BSBOPS601 Develop Implement Business Plans - SDocument91 pagesBSBOPS601 Develop Implement Business Plans - SSudha BarahiNo ratings yet

- Test Bank For American Corrections Concepts and Controversies 2nd Edition Barry A Krisberg Susan Marchionna Christopher J HartneyDocument36 pagesTest Bank For American Corrections Concepts and Controversies 2nd Edition Barry A Krisberg Susan Marchionna Christopher J Hartneyvaultedsacristya7a11100% (30)

- Capsule Research ProposalDocument4 pagesCapsule Research ProposalAilyn Ursal80% (5)

- Hosts 1568558667823Document5 pagesHosts 1568558667823Vũ Minh TiếnNo ratings yet

- Ficha Tecnica 320D3 GCDocument12 pagesFicha Tecnica 320D3 GCanahdezj88No ratings yet

- PovidoneDocument2 pagesPovidoneElizabeth WalshNo ratings yet

- Remuneration Is Defined As Payment or Compensation Received For Services or Employment andDocument3 pagesRemuneration Is Defined As Payment or Compensation Received For Services or Employment andWitty BlinkzNo ratings yet

- CPE Cisco LTE Datasheet - c78-732744Document17 pagesCPE Cisco LTE Datasheet - c78-732744abds7No ratings yet