Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Research Q2 W2

Uploaded by

Fhilip Job Belos0 ratings0% found this document useful (0 votes)

44 views9 pagesRESEARCH WEEK 2

Original Title

RESEARCH Q2 W2

Copyright

© © All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

DOCX, PDF, TXT or read online from Scribd

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentRESEARCH WEEK 2

Copyright:

© All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

Download as DOCX, PDF, TXT or read online from Scribd

0 ratings0% found this document useful (0 votes)

44 views9 pagesResearch Q2 W2

Uploaded by

Fhilip Job BelosRESEARCH WEEK 2

Copyright:

© All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

Download as DOCX, PDF, TXT or read online from Scribd

You are on page 1of 9

Name: Fhilip Job Belos PRACTICAL RESEARCH 2

ABM – 12

Q2 – W2

Activity 1

1. A

2. D

3. C

4. D

5. B

6. B

7. A

8. A

9. C

10. B

ACTIVITY II

1.(Baraceros, 2016) As Budgen & Brereton said, “reviewing the

literature requires the ability to juggle multiple tasks, from

Finding and evaluating relevant material to synthesizing information

from various sources, from critical thinking to paraphrasing, evaluating,

and citation skills” (p. 31).

2.(Baraceros, 2016) The format of a review of literature may vary from

discipline to discipline and from assignment to assignment.

3.(Baraceros, 2016) it is necessary for you to review information, facts,

data available, or theories that have some relationship with your

hypothesis which you posed in your stated problem or research

question.

4.(Calmorin and Calmorin, 2007) stated, “the investigator should have

the ability to compare between what he should read and include in his

study and what he should not read and does not need to include in his

study.

5.(Write Source 2007) A reliable source should provide information

fairly, covering all sides of a subject. (p. 345)

ACTIVITY III

1. Budgen and Brereton asserted that the ability to handle a variety

of activities is required when studying a literature, from finding

and evaluating relevant material to integrating knowledge from

various sources, through logical reflection to describing, rating,

and citation abilities.

2. The structure of a review article can vary between topic to topic

and program to project.

3. It’s critical to go over any material, statistics, figures, or ideas that

are related to the premise you made in your issue or question of

the study.

4. An researcher has to be capable of distinguishing among what he

might study and include in his inquiry and what he might not read

or be included in his analysis.

5. A credible newspaper should provide correct info across all edges

of a topic.

“The COVID-19 pandemic and its effects on teacher education”

Systematic Review

The COVID-19 epidemic has had a variety of effects on schooling at

all levels. Institutions and teacher educators had to react rapidly to

an unforeseen and ‘forced’ shift from face-to-face to online

education. They also had to create learning environments for

student teachers who were preparing to become teachers, taking

into account the requirements of teacher education programs as

well as the conditions in which both universities and schools had to

operate.

A review of the research on online teaching and learning techniques

in teacher education is presented in this paper. There were a total of

134 empirical research examined. The presence of social, cognitive,

and teaching presence in online teaching and learning practices was

identified.

The findings emphasized the importance of a complete vision of

online education pedagogy that incorporates technology to help

teaching and learning. The findings of this study are examined in

relation to the development of online teaching and learning

techniques. Suggestions for further research will also be considered.

The COVID-19 pandemic has had a variety of effects on education,

particularly teacher education. Teachers and students had to quickly

adapt to remote teaching as a result of the closure of universities

and schools. There is no exception when it comes to teacher

education. The need to design learning settings for student teachers

preparing for teacher education required decisions, choices, and

modifications to fulfill not only student expectations, but also

teacher education requirements and the conditions in which both

universities and schools had to function (Flores and Gago 2020).

The abrupt, unplanned, and ‘forced’ shift from face-to-face to online

teaching has created a variety of obstacles and limits, as well as

opportunities, that must be considered. Existing literature refers to

‘emergency remote teaching’ (Bozkurt and Sharma 2020, I or

‘emergency eLearning’ (Murphy 2020, 492), as well as challenges

such as poor online teaching infrastructure, teacher inexperience,

the information gap (i.e., limited information and resources for all

students), and the complex home environment (Zhang et al. 2020).

In addition, challenges connected to teachers’ competences in the

use of digital instructional forms (Huber and Helm 2020) and a lack

of mentoring and assistance (Judd et al. 2020) have been observed.

In terms of teacher education, descriptions of how institutions and

stakeholders adapted to the new scenario created by the COVID-19

pandemic (Bao 2020; Flores and Gago 2020; Quezada, Talbot, and

Quezada-Parker 2020; Zhang et al. 2020) as well as training

strategies and innovation experiences (Ferdig et al. 2020) have been

published. While stories of how higher education institutions and

teacher educators reacted to the shift from face-to-face to online

instruction are useful, further research is needed. It is critical to gain

a better understanding of the potential and applications of online

teaching and learning in order to be more informed and productive.

As a result, it is critical to build excellent online teaching and learning

that is the outcome of deliberate instructional design and planning,

rather than relying on emergency online methods (Hodges et al.

2020).

The search was limited to articles published between January 2000

and April 2020 that dealt with online teaching and learning in the

context of teacher education. Because online learning developed

after the development of the World Wide Web and the widespread

usage of the Internet in many homes, the search was confined to this

time period (Bates 2005). This date also coincides with the

emergence of virtual learning initiatives as a result of

internationalisation and competition among European higher

education institutions in the context of European higher education

convergence as a direct result of the Bologna Process (1999).

A search of the databases Web of Science (main collection) and

Education Resources Information Centre was used to choose the

literature for the current review (ERIC). Publications with the terms

‘online learning’ (or the terms ‘digital learning’ or ‘e-learning’ or

‘web-based learning’ or’remote learning’ or ‘distance learning’ or

‘virtual learning’) in the title and that responded to the

descriptors/topics ‘teacher education’, ‘teacher training’, or ‘virtual

learning’ were sought. Although the terms online, e-learning, virtual,

digital, web-based, remote, and distance learning are not

interchangeable, they were considered relevant for the purposes of

this study, which looked at any type of practice in which the teaching

and learning process is mediated by the use of technology in a

remote setting.

The two types of analysis were performed on the publications that

were chosen. First, a descriptive analysis was performed, which

included the creation of a summary table for each of the papers that

detailed the study’s focus, sample characteristics, methods, and

main findings.1 Next, a content analysis (Ryan and Bernard 2000)

was performed, which used the CoI framework (Garrison, Anderson,

and Archer 2000) to sort the data into categories. This involved the

creation of a table that incorporated the findings in regard to online

teaching and learning practices connected to social, cognitive, and

teaching presence, as defined by the CoI framework, for each of the

publications.

This investigation has revealed that several areas of research require

further focus. To begin, more emphasis should be placed on practical

learning areas such as learning design (see also Best and MacGregor

2017). Although the characteristics of online learning design that

were likely to contribute to teaching and learning impact were

highlighted in this study, they were not the primary focus of the

studies analyzed. Second, more attention should be paid to the

pedagogical concerns that contribute to cognitive advances. While

some research (e.g., Baran and Cagiltay 2010; Mumford and Dikilitaş

2020) highlighted educational interventions that fostered reflection

and knowledge acquisition, not all of them gave particular data on

the pedagogical challenges associated with them. Third, further

research is needed to determine the impact of an integrated

pedagogy for online teaching and learning. More studies are

recognizing the different pedagogical approaches required for an

effective online learning experience (e.g., Doering et al. 2009; Niess

and Gillow-Wiles 2014), but more research is needed to examine

issues related to teaching and learning in such an environment using

a comprehensive framework. Finally, a greater emphasis should be

placed on procedural and conceptual teaching experiences. Although

studies that focus on the practicum in the context of online teacher

education (e.g., Rideout et al. 2008; Prilop, Weber, and Kleinknecht

2020; So, Hung, and Yip 2008) address these issues, more research

on experiences with the practicum and other procedural areas (e.g.,

Music, Visual Arts, or Physical Education) would be beneficial.

This research looked at the literature on online teaching and learning

in the context of teacher education, as well as the practices that lead

to positive outcomes. However, due to the large number of studies

under consideration and word limits, this paper has focused on the

most recurrent themes or aspects that were deemed to be the most

relevant for the purpose of this paper and has left out other

important issues (e.g., other online tools such as podcasts, MOOCs,

gamification, or virtual worlds, and descriptions of their affordances

and constraints; the ways in which teachers’ and students’

perspectives are shaped by these tools; the ways in which teachers’

and students’.

Furthermore, despite the rapidly changing practices in this area and

the relatively few papers published during the period 2000–2010 (n

= 36), this review included literature published between January

2000 and April 2020, suggesting that these papers do not accurately

reflect the current state of online learning. Furthermore, the

inclusion of papers until April 2020 excludes more recent research

that look at challenges related to online teaching and learning in the

context of the COVID-19 epidemic. Understanding the particularities

of the period and the decisions made in the transition from face-to-

face to online format requires understanding the context and

circumstances in which higher education institutions had to establish

these practices. Because teacher education is an iterative and

complex process that must look “backwards, forwards, inside-out,

and outside-in” to respond to the changing needs of a world that is

“moving, blurring, and shifting” (Ling 2017, 562), acknowledging and

addressing the current and changing exceptional circumstances that

teachers and students are experiencing in these unprecedented

times is necessary and would provide valuable information to

continue informing future online practices.

You might also like

- Principles of Blended Learning: Shared Metacognition and Communities of InquiryFrom EverandPrinciples of Blended Learning: Shared Metacognition and Communities of InquiryNo ratings yet

- Teaching in Blended Learning Environments: Creating and Sustaining Communities of InquiryFrom EverandTeaching in Blended Learning Environments: Creating and Sustaining Communities of InquiryRating: 5 out of 5 stars5/5 (5)

- Covid 19 y Educacion de Profesores Revision de La Literatura PDFDocument23 pagesCovid 19 y Educacion de Profesores Revision de La Literatura PDFMilton Figueroa GNo ratings yet

- Ej 1332714Document17 pagesEj 1332714stephaniejoyremigioNo ratings yet

- Integrating Technology ProblemsDocument6 pagesIntegrating Technology ProblemsHyacinth Kaye NovalNo ratings yet

- Perspective On Blended Learning Among The College Students of Siargao Island Institute of Technology SY:2021-2022Document41 pagesPerspective On Blended Learning Among The College Students of Siargao Island Institute of Technology SY:2021-2022Maricel NogaloNo ratings yet

- Rapanta2020 Article OnlineUniversityTeachingDuringDocument23 pagesRapanta2020 Article OnlineUniversityTeachingDuringMichelle Gliselle Guinto MallareNo ratings yet

- Effective Online PedagogiesDocument7 pagesEffective Online PedagogiesIrbaz KhanNo ratings yet

- Nurmawulansari Rahadian 20202244071 ELTAnalysis X2Document4 pagesNurmawulansari Rahadian 20202244071 ELTAnalysis X2Kevin PraditmaNo ratings yet

- Students', Teachers', and Parents' Adaptation to Sudden Shift in Learning During CovidDocument12 pagesStudents', Teachers', and Parents' Adaptation to Sudden Shift in Learning During CovidTsaniaNo ratings yet

- Literature Review On e Learning PDFDocument12 pagesLiterature Review On e Learning PDFafdtktocw100% (1)

- Implementation of Online Home-Based Learning and Students' Engagement During The COVID-19 Pandemic: A Case Study of Singapore Mathematics TeachersDocument12 pagesImplementation of Online Home-Based Learning and Students' Engagement During The COVID-19 Pandemic: A Case Study of Singapore Mathematics TeachersREVATHI A/P RAJENDRAN MoeNo ratings yet

- IELTS Reading TaskDocument2 pagesIELTS Reading Taskmuhammed taiyeNo ratings yet

- Literature Review On Online TicketingDocument5 pagesLiterature Review On Online Ticketingc5sq1b48100% (1)

- Chapters I To Iii 2022Document55 pagesChapters I To Iii 2022Vladimer PionillaNo ratings yet

- Review of Related Literature and StudiesDocument5 pagesReview of Related Literature and Studiesczarina romeroNo ratings yet

- (17552281 - Learning and Teaching) The Effectiveness of Online Teaching and Learning ToolsDocument18 pages(17552281 - Learning and Teaching) The Effectiveness of Online Teaching and Learning ToolsMahamud AliNo ratings yet

- Article Critique Patrick Lyall Siena Heights University Teaching and Technology in Higher Education Liliana ToaderDocument11 pagesArticle Critique Patrick Lyall Siena Heights University Teaching and Technology in Higher Education Liliana Toaderapi-268595848No ratings yet

- Kang 2020Document17 pagesKang 2020Putri SariniNo ratings yet

- Eresearch: The Open Access Repository of The Research Output of Queen Margaret University, EdinburghDocument10 pagesEresearch: The Open Access Repository of The Research Output of Queen Margaret University, EdinburghRukaya DarandaNo ratings yet

- Teachers Perspective On Blended Learning Post Covid-19Document25 pagesTeachers Perspective On Blended Learning Post Covid-19Geoffrey Acheampong (Snowflake)No ratings yet

- Chapter 2Document4 pagesChapter 2Re MarNo ratings yet

- Facilitating Student Engagement Through PDFDocument25 pagesFacilitating Student Engagement Through PDFMary Joyce GarciaNo ratings yet

- CHAPTER 2 ResearchDocument14 pagesCHAPTER 2 ResearchMiscka Adelle AlaganoNo ratings yet

- Literature Review - Ai Li-Enhance One-On-One Distance Learning With Educational TechnologyDocument18 pagesLiterature Review - Ai Li-Enhance One-On-One Distance Learning With Educational Technologyapi-634793721No ratings yet

- Emmanuel Eng150 Document Annotated Bib BLANK TEMPLATEDocument11 pagesEmmanuel Eng150 Document Annotated Bib BLANK TEMPLATEda xzibitNo ratings yet

- Teachers' Perspectives on Online Learning During the PandemicDocument14 pagesTeachers' Perspectives on Online Learning During the PandemicMUHAMMAD NASRUL AMIN BIN MD NIZAMNo ratings yet

- Chapter 2 RRLDocument16 pagesChapter 2 RRLMa. Cristina NolloraNo ratings yet

- Chen Et Al 38-6Document19 pagesChen Et Al 38-6hakeemNo ratings yet

- Reflections On Educational Practice COVIDocument6 pagesReflections On Educational Practice COVILuis Eduardo MolinaNo ratings yet

- Relationship Between Learning Styles and ObjectsDocument18 pagesRelationship Between Learning Styles and ObjectsJeon BammyNo ratings yet

- The Problem and A Review of Related LiteratureDocument28 pagesThe Problem and A Review of Related LiteratureAlthea MendiolaNo ratings yet

- The Lived Experiences of Junior High School Science Teachers Amidst The COVID-19 Pandemic An Inquiry-Based LearningDocument11 pagesThe Lived Experiences of Junior High School Science Teachers Amidst The COVID-19 Pandemic An Inquiry-Based LearningPsychology and Education: A Multidisciplinary JournalNo ratings yet

- Annotatedbibliography FilippiDocument9 pagesAnnotatedbibliography Filippiapi-501705567No ratings yet

- Watermarked - Preservice Teachers Beliefs About Their Future Teaching Due To Their Massive Online Learning Experience - Sep 01 2023 21 40 38Document17 pagesWatermarked - Preservice Teachers Beliefs About Their Future Teaching Due To Their Massive Online Learning Experience - Sep 01 2023 21 40 38cucu sitimaryamNo ratings yet

- A Framework For DesignDocument2 pagesA Framework For Designaleem_80No ratings yet

- Challenge Based Learning in Higher Education– ADocument11 pagesChallenge Based Learning in Higher Education– APanagiotis PantzosNo ratings yet

- Students' Perceptions of Online Learning: A Comparative StudyDocument20 pagesStudents' Perceptions of Online Learning: A Comparative StudyToscanini MarkNo ratings yet

- Elearning MendeleyDocument6 pagesElearning MendeleyPrezzNo ratings yet

- Fulfillments and Failures of Virtual Learning Environment (VLE) : A Systematic ReviewDocument12 pagesFulfillments and Failures of Virtual Learning Environment (VLE) : A Systematic ReviewInternational Journal of Recent Innovations in Academic ResearchNo ratings yet

- Jurnal Scopus 1Document16 pagesJurnal Scopus 1amelamelia234567No ratings yet

- Trends and Issues of Blended Learning With Reference To Covid 19 PeriodDocument9 pagesTrends and Issues of Blended Learning With Reference To Covid 19 PeriodIJAR JOURNALNo ratings yet

- Chapter - 2 Review of LiteratureDocument57 pagesChapter - 2 Review of LiteraturePreya Muhil ArasuNo ratings yet

- Redesigning Teaching Practices in Higher Education Amidst Pandemic: The Case of Technologically Challenged InstructorsDocument18 pagesRedesigning Teaching Practices in Higher Education Amidst Pandemic: The Case of Technologically Challenged InstructorsShella Mae LozadaNo ratings yet

- To Check by The AdviserDocument19 pagesTo Check by The AdviserJohn Michael PerezNo ratings yet

- 8 SSP BSR c23Document15 pages8 SSP BSR c23Agsaoay, Ericka Mae A.No ratings yet

- Students Perceptions Case StudyDocument19 pagesStudents Perceptions Case Studyapi-286737609No ratings yet

- Web-Based Instruction: Analyzing Students Satisfaction and Learning InterestDocument9 pagesWeb-Based Instruction: Analyzing Students Satisfaction and Learning InterestPaper PublicationsNo ratings yet

- Implementing OER in Digital EducationDocument4 pagesImplementing OER in Digital EducationHarsa W. RamadhanNo ratings yet

- QCA Teachers Perception 2022Document19 pagesQCA Teachers Perception 2022Katerina LvuNo ratings yet

- Online Learning Performance and Satisfaction: Do Perceptions and Readiness Matter?Document23 pagesOnline Learning Performance and Satisfaction: Do Perceptions and Readiness Matter?M HasanNo ratings yet

- (2021) Leijon, Gudmundsson, Staaf, Christersson - Challenge based learning in higher education– A systematic literature review. Innovations iDocument11 pages(2021) Leijon, Gudmundsson, Staaf, Christersson - Challenge based learning in higher education– A systematic literature review. Innovations iiepaNo ratings yet

- Perspective and Challenges of College Students in The Online LearningDocument10 pagesPerspective and Challenges of College Students in The Online LearningPsychology and Education: A Multidisciplinary JournalNo ratings yet

- Review of Smart Learning: Patterns and Trends in Research and PracticeDocument16 pagesReview of Smart Learning: Patterns and Trends in Research and PracticeTaregh KaramiNo ratings yet

- Online Learning MethodologyDocument8 pagesOnline Learning MethodologyTani ArefinNo ratings yet

- Updated Blended Learning and PBL in A High School Science Class Literature ReviewDocument9 pagesUpdated Blended Learning and PBL in A High School Science Class Literature Reviewapi-520658920No ratings yet

- A Focus Upon E-Learning PP 7-20Document15 pagesA Focus Upon E-Learning PP 7-20Erika LealNo ratings yet

- Order #441446986Document17 pagesOrder #441446986David ComeyNo ratings yet

- Reshaping Assessment Practices in A Philippine Teacher Education Institution During The Coronavirus Disease 2019 CrisisDocument7 pagesReshaping Assessment Practices in A Philippine Teacher Education Institution During The Coronavirus Disease 2019 CrisisMella Mae GrefaldeNo ratings yet

- E-Learning Literature and Studies ReviewDocument10 pagesE-Learning Literature and Studies ReviewDick Jefferson Ocampo PatingNo ratings yet

- Daftar PustakaDocument8 pagesDaftar PustakaAbiezer AnggaNo ratings yet

- Prof. Hanumant Pawar: GeomorphologyDocument15 pagesProf. Hanumant Pawar: GeomorphologySHAIK CHAND PASHANo ratings yet

- Class NoteDocument33 pagesClass NoteAnshuman MukherjeeNo ratings yet

- Odato G-7 LP HomonymsDocument11 pagesOdato G-7 LP HomonymsIvy OdatoNo ratings yet

- Frontal - Cortex Assess Battery FAB - ScaleDocument2 pagesFrontal - Cortex Assess Battery FAB - Scalewilliamsa01No ratings yet

- Troubleshooting Edge Quality: Mild SteelDocument14 pagesTroubleshooting Edge Quality: Mild SteelAnonymous U6yVe8YYCNo ratings yet

- UNIT-I Problems (PSE EEE)Document6 pagesUNIT-I Problems (PSE EEE)Aditya JhaNo ratings yet

- Defibrelator ch1Document31 pagesDefibrelator ch1د.محمد عبد المنعم الشحاتNo ratings yet

- Srikanth Aadhar Iti CollegeDocument1 pageSrikanth Aadhar Iti CollegeSlns AcptNo ratings yet

- Cost-Time-Resource Sheet for Rumaila Oil Field Engineering ServicesDocument13 pagesCost-Time-Resource Sheet for Rumaila Oil Field Engineering ServicesonlyikramNo ratings yet

- CLASS 10 CH-1 ECO DEVELOPMENT Question AnswersDocument8 pagesCLASS 10 CH-1 ECO DEVELOPMENT Question AnswersDoonites DelhiNo ratings yet

- Practical Research 2: Quarter 1 - Module 1Document35 pagesPractical Research 2: Quarter 1 - Module 1Alvin Sinel Belejerdo90% (10)

- David Kassan DemoDocument3 pagesDavid Kassan DemokingkincoolNo ratings yet

- Chemistry SyllabusDocument9 pagesChemistry Syllabusblessedwithboys0% (1)

- Microsoft MB-210 Exam Dumps With Latest MB-210 PDFDocument10 pagesMicrosoft MB-210 Exam Dumps With Latest MB-210 PDFJamesMartinNo ratings yet

- El 5036 V2 PDFDocument86 pagesEl 5036 V2 PDFCriss TNo ratings yet

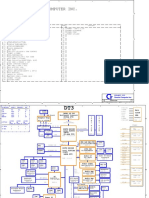

- Acer Aspire 1710 (Quanta DT3) PDFDocument35 pagesAcer Aspire 1710 (Quanta DT3) PDFMustafa AkanNo ratings yet

- 2018 General Education Reviewer Part 10 - 50 Questions With Answers - LET EXAM - Questions & AnswersDocument10 pages2018 General Education Reviewer Part 10 - 50 Questions With Answers - LET EXAM - Questions & AnswersScribdNo ratings yet

- Yearly Lesson Plan LK Form 5Document26 pagesYearly Lesson Plan LK Form 5Nur'ain Abd RahimNo ratings yet

- Creating Quizzes in MS PowerPointDocument6 pagesCreating Quizzes in MS PowerPointZiel Cabungcal CardañoNo ratings yet

- Management Quality ManagementDocument7 pagesManagement Quality ManagementJasmine LimNo ratings yet

- SP-1127 - Layout of Plant Equipment and FacilitiesDocument11 pagesSP-1127 - Layout of Plant Equipment and FacilitiesParag Lalit SoniNo ratings yet

- Coursebook 1Document84 pagesCoursebook 1houetofirmin2021No ratings yet

- Theoretical Foundation in Nursing: LESSON 8Document4 pagesTheoretical Foundation in Nursing: LESSON 8Gabriel SorianoNo ratings yet

- Sub Net Questions With AnsDocument5 pagesSub Net Questions With AnsSavior Wai Hung WongNo ratings yet

- 3G FactsDocument17 pages3G Factsainemoses5798No ratings yet

- Ambiguity in Legal Translation: Salah Bouregbi Badji Mokhtar University Annaba - Algeria - Salihbourg@Document14 pagesAmbiguity in Legal Translation: Salah Bouregbi Badji Mokhtar University Annaba - Algeria - Salihbourg@MerHamNo ratings yet

- Generac Generac CAT MTU Cummins KohlerDocument3 pagesGenerac Generac CAT MTU Cummins KohlerJuly E. Maldonado M.No ratings yet

- Robinair Mod 10324Document16 pagesRobinair Mod 10324StoneAge1No ratings yet

- Test Paper Trigonometric Functions and Equations PDFDocument9 pagesTest Paper Trigonometric Functions and Equations PDFkaushalshah28598No ratings yet