Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Performance Anxiety - Performance Art in Twenty-First Century Catalogs and Archives27949564

Uploaded by

Nina RaheOriginal Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Performance Anxiety - Performance Art in Twenty-First Century Catalogs and Archives27949564

Uploaded by

Nina RaheCopyright:

Available Formats

Performance Anxiety: Performance Art in Twenty-First Century Catalogs and Archives

Author(s): Christina Manzella and Alex Watkins

Source: Art Documentation: Journal of the Art Libraries Society of North America ,

Spring 2011, Vol. 30, No. 1 (Spring 2011), pp. 28-32

Published by: The University of Chicago Press on behalf of the Art Libraries Society of

North America

Stable URL: https://www.jstor.org/stable/27949564

REFERENCES

Linked references are available on JSTOR for this article:

https://www.jstor.org/stable/27949564?seq=1&cid=pdf-

reference#references_tab_contents

You may need to log in to JSTOR to access the linked references.

JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide

range of content in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and

facilitate new forms of scholarship. For more information about JSTOR, please contact support@jstor.org.

Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of the Terms & Conditions of Use, available at

https://about.jstor.org/terms

Art Libraries Society of North America and The University of Chicago Press are collaborating

with JSTOR to digitize, preserve and extend access to Art Documentation: Journal of the Art

Libraries Society of North America

This content downloaded from

200.144.238.164 on Thu, 11 Nov 2021 18:03:03 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

Performance Anxiety: Performance Art in Twenty-First

Century Catalogs and Archives_

Christina Manzella and Alex Watkins

How does one document performance art, which is not an object but an interaction between artist and viewers? After the perfor

mance, the work is preserved in various videos, photographs, eyewitness accounts, and remaining artifacts. It is these remains that

enter the archive and the catalog, and which must be described and interrelated to give an idea of the original performance. This

article addresses several practical and philosophical concerns that are raised by this process of integration and their ramifications.

Introduction making it impermanent.3 What then of performance art and

its apparent refusal to remain other than in the memories of

Performance art, with its ties to both the fine and performing viewers?

arts, exists in four dimensions and as a multisensory experi

ence. By nature, it is an ephemeral activity, which, in a culture The Performance Art Record

obsessed with materiality and posterity, proves problematic. It

raises questions about how the librarian or archivist records art Performance art can be found mostly in visual resources

and can preserve an impression of it for future generations. Must collections and museum catalogs. A museum may stage the

performance art as part of its nature disappear? How can the performance, collect an art object created during the perfor

immaterial, the fleeting, be captured and preserved, and does mance, or acquire a video of the performance. In its catalog it

would ideally link these items to the now vanished performance

that in some way change it? Does performance art perhaps exist

after the fact solely in its documentation to the extent that the that generated them. However, the nature of performance art

documentation and the performance merge and become one in raises serious obstacles to its being cataloged. Here, organizing

the same? These are difficult questions which cannot be easily and documenting works of art can be a struggle at odds with

answered or dismissed. performance art's natural tendency to disappear. It can only be

re-experienced through mediation by various media that capture

The Stakes of Performance Art Documentation some element of the performance. A complete set of documenta

tion allows for a fuller understanding of the performance. Every

Documentation is often the only way that many people, piece of evidence makes each other piece function better, "each

even scholars, will ever interact with a work of performance art.

document touches at its root the idea of the original, and then

Performance art and documentation need each other. "The body moves out from there, diverging in various ways, connecting to

art event needs the photograph to confirm its having happened; other documents, and producing an accumulation that is best

the photograph needs the body art event as an ontological understood collectively."4

'anchor' of its indexicality."1 This argument that Amelia Jones The performance art record will by necessity consist of several

makes convincingly points to the key role good documentation interconnected records. The central record is that of the work?

plays in the understanding of past performances. There is no that is the idea, as described by the Functional Requirements for

evidence of a performance ever having happened without docu Bibliographic Records (FRBR), the entity-relationship metadata

mentation. Without the physical remnants, it is as if something model developed by the International Federation of Library

never existed; the remains, unlike in societies with oral histories,

Associations and Institutions (IFLA) in 1998.5 Connected to

are the great legitimizers.2 Further, if that documentation cannot this overarching artistic idea are expressions of the work. In the

be found or is not well organized, the performance cannot be case of performance art this may be individual performances of

re-experienced. The stakes for performance art documentation the same performance piece. After this level FRBR proceeds to

are much higher than those for objective art, which exists inde manifestations, physical items. Performance art does not exist in

pendently of its evidence. physical form; however, it can leave behind physical remains.

Memory's legitimacy has decreased as available technolo Performance creates two main types of evidence, documentary

gies have changed the way people record their experiences. It and artifactual. Documentation includes still images, video

has become even more important to leave a legacy, to record recordings and/or audio recordings, which often become stand

"for posterity's sake." Memory alone is not sufficient in the ins for the performance itself. Artifacts include the props and

West because it is seen as tainted by emotion and therefore products used and produced by a performance along with the

fallible?unlike documentation, which, in name itself, implies ephemera that accompany a performance. All these items should

fact. Memory too, like performance, is a "body-based practice," be interconnected through the main work record. The chart in

28 Art Documentation ? Volume 30, Number 1 ? 2011

This content downloaded from

200.144.238.164 on Thu, 11 Nov 2021 18:03:03 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

often simplified, all too often to a single

image. In several cases "such documenta

tion [has] become iconic in its continued

reproduction as complex works were

reduced to singular images."9 This

phenomenon, all too common in repre

sentations of performance art, is exactly

what a good catalog entry will prevent

and a bad one will perpetuate.

Cataloging Cultural Objects, the

data content standards initiative for the

cultural heritage community developed

by the Visual Resources Association,

makes "clearly distinguish[ing] between

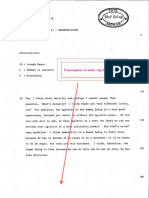

Figure 1: Diagram of "FRBRized" performance records. Work Records and Image Records"

part of its key principles.10 This is never

figure 1 diagrams the performance records' relationships and more important than with performance

their locations in the FRBR model. because of the tendency for the representation to replace the

The first requirement to successfully catalog performance event completely. The performance record should use metadata

art is to determine what constitutes a work of performance art. to make clear that the work of art is a performance event located

A work in the FRBR model is "a distinct intellectual or artistic at a specific place in time and space. The performance can also

creation."6 It is the idea that exists separately from different make use of measurement metadata element types such as dura

expressions of that same creation. The line between what is tion, to more clearly locate the performance in time. Then the

simply another expression and what constitutes a new work performance can be related to its documentation through rela

is negotiable and subjective. "Because the notion of a work is tional metadata elements such as the VRA Core's "Imagels"

abstract, it is difficult to define precise boundaries for the entity. relation type or in multimedia environments through a video

The concept of what constitutes a work and where the line of relation type (not part of VRA Core).11 Without these two sepa

demarcation lies between one work and another may in fact rate entries it is often unclear if the record is of video art or

be viewed differently..."7 To find this line for performance art, performance art. This also serves to relate many images of one

there must be negotiation between performance art's ability to performance and perhaps its video, ensuring that performance

be restaged and each performance's singularity. art is not supplanted by a single iconic image and that the event

A logical structure needs to be created to convey the infor has an autonomous existence.

mation about a performance. This is especially true for famous

performances that the original artist has re-performed many The Material Remains of Performance

times, such as Yoko Ono's Cut Piece. A work of performance Besides documentation, a performance leaves behind

art should be defined mainly using artist and title metadata.

objects, artifacts of the performance. Sometimes these cast-offs

Several performances of the same work by the same artist can

become art objects themselves, lasting evidence of an imperma

be considered expressions of one idea or work. Each individual

nent experience. "Certain collectible artifacts are produced or

expression needs to be differentiated by making use of date and

location metadata elements and connected back to the main used, ephemera created or transformed through acts of perfor

mance."12 Sometimes these objects are as large as an elaborate

entry. Alternatively each performance can be independent, set piece a performance uses, or as small as props manipulated

although this creates a less organized and less "FRBRized" struc

in the act of performance. These pieces are important to catalog

ture. Re-performances by a new artist should be considered a

and to connect to the performance from which they resulted.

new work, even if they are making use of the same idea. The new

Sometimes these objects replace the performance as the main art

artist acts both as a performer and a creator, implicitly recreating

object, displayed and cataloged as works in and of themselves.

the work in his or her own image. The body of the performer

Matthew Barney's Drawing Restraint 14, a. performance in which

and the role of the artist are central to performance art. The new

the artist suspended himself from a bridge to create an image

performances could be viewed, as described by Jessica Santone,

on the wall, has become an installation, not a performance? a

as "reverberations of single past moments rather than as full

drawing on the museum wall.13 Despite the tendency for prod

re-embodiments of the works."8 It is possible to relate these rein

ucts of a performance to supplant the event itself, they are

terpretations through work-to-work relationships.

important to the creation of complete records. "After the event

these can serve a mnemonic function, triggering memories to be

Image and Video of Performance Art

imagined, or act as 'utopian traces,' demanding multiple re-uses,

In performance art, the evidence and performance are both actually and virtually."14 They help users imagine a work

closely intertwined; therefore, clear relationships need to be they never saw, and they provide a key physical connection to

made between work and image records. Image and video docu long-gone performances like a relic to a saint.

mentation should be closely linked to the performance, without Creating records of props and products of a performance

supplanting performance as the work type. Performances are adds another layer of complexity but also richness to the catalog.

prone to reduction. Their complicated existence means they are Performances can be connected to their artifacts through rela

Volume 30, Number 1 ? 2011 ? Art Documentation 29

This content downloaded from

200.144.238.164 on Thu, 11 Nov 2021 18:03:03 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

tional metadata elements. Unfortunately, no clear relationship mentation?Bruce Nauman's highly detailed instructions from

types exist in VRA Core. Relationships like "componentOf" or his Body Pressure (1974) and a single poster along with written

"designedFor" may be applicable to items created for a perfor accounts of VALIE EXPORT'S Action Pants: Genital Panic (1969)

mance. For items that are produced by a performance, there is for example.19 Museums and other cultural institutions also

no standard relationship type that fits perfectly. The relation have a stake in creating lasting records of performances as they

ship between performance and its creations suggests new types often record such events via film and video. For The Artist Is

such as "productOf" or "producedBy." Creating good records Present, MoMA photographed each person who sat across from

helps sort and organize the performance and its various images, Abramovic. These portraits along with the date and length of

videos, props, and creations. time each person sat can still be viewed on the exhibition's Web

site.20

Performance Ephemera

Performances leave behind all variety of ephemera,

including announcements, press releases, reviews, photographs,

and correspondence. These objects are often preserved in artists'

files which are vital to researchers of local and lesser known

artists who are not well represented in traditional resources.15 It

can be challenging to link performance art records to an artist's

file that may be in a different catalog altogether. The favored

method of access to an artist's file is through the creation of a

MARC record in the library's catalog. This allows not only for

increased description but also for greater consistency and the

ability to share records among libraries.16 One such example of

linking between performance art records and artist's files can be

found in the New York Museum of Modern Art's (MoMA) collec

tion database. A "Further Resources" link from the collection

catalog record leads into a keyword search for an artist's name in

the library catalog; an artist's file (if it exists) will show up in the

results.17 This is clearly not the only use for the link, which also

brings up books and other resources. A direct link to an artist's

file may be preferable, as it can more clearly relate ephemera to

the performance.

Performance Art in the Archive

If an archive is a record comprised of material objects, it

would seem then that an archive would reject performance art

or that performance art, inherently, would reject being archived.

However, an archive is, essentially, evidence of things past, of

what has disappeared. Therefore, if performance art can be

documented, then it can be archived.

In art conservation terms, performance art as a medium

Figure 2: Marina Abramovic: The Artist Is Present, at The Museum of

contains a kind of metaphorical inherent vice: its degradation

Modern Art, 2010. ? 2011 Marina Abramaovic. Courtesy the artist and

from its original form is guaranteed. In archival terms, perfor Sean Kelly Gallery/Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York. Photograph by

mance art "challenge[s] object status and seems to refuse the Alex Watkins.

archive its privileged 'savable' original."18 Both are correct yet not

?ntirely accurate. Performance artists, like so many others, want

These documents, whether by the artist, the museum, or

their work and themselves to be remembered, as evidenced by an audience member, bring up "issues of authorship, medium

their self-documentation and their repeat performances of past and authenticity."21 First, it must be stated that, in the case of

works. In her 2010 show The Artist Is Present, held at the Museum

performance art, a document is not the original and, therefore,

of Modern Art in New York, Marina Abramovic recreated her

acts as a mediator. Secondly, the document, whether authored

Nightsea Crossing (with Ulay, 1982,1985,1986) and directed other by the artist or another party, contains inherent bias, which is

performers in re-stagings of many of her other past works. This

amplified by its medium.22 No one individual or medium can

was done in an attempt to introduce new people to her work, capture every aspect of a four-dimensional, multisensory event.

and to create new documentation and new memories, which

Additionally, some recorders have an agenda to fulfill with

will carry on her existence. She is not only concerned with her their document creation, while others bring with them personal

own work living on but with others' as well. In her perfor experience which colors the way in which they perceive a partic

mance Seven Easy Pieces (2005) at the Guggenheim Museum in ular happening. These documents also bring up the issue of

New York, Abramovic brought back to life five performances when something becomes a new work.23 Peggy Phelan argues

by other artists, one by herself, and introduced a new piece of that, "Performance cannot be saved, recorded, documented or

her own. She did these re-performances through available docu

30 Art Documentation ? Volume 30, Number 1 ? 2011

This content downloaded from

200.144.238.164 on Thu, 11 Nov 2021 18:03:03 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

otherwise participate in the circulation of representations of they might have felt moved to speak. Perhaps. The body of

representations: once it does so, it becomes something other than this text is a residue, that which is left. An act of remem

performance/'24 This is especially obvious in video recordings of bering and rewriting, and of retracing myself.28

performance pieces, in which the document can be "described as

performative."25 To replay a recording of a performance is a new Notes

performance, one with a new author and medium. Instead, what

seems more accurate in keeping to the integrity of the original 1. Amelia Jones, "'Presence' in Absentia: Experiencing

and therefore more relevant to the archive is this idea of repeat Performance as Documentation," Art Journal 56, no. 4 (Winter

1997): 16.

and re-performances.

2. Rebecca Schneider, "Archives: Performance Remains,"

The Living Archive Performance Research 6, no. 2 (2001): 100-101.

3. Ibid., 101.

In repeating and directing re-stagings of her own perfor 4. Jessica Santone, "Marina Abramovic's Seven Easy Pieces:

mances and in re-performing others' performances, Marina Critical Documentation Strategies for Preserving Art's History,"

Abramovic is, in essence, creating a living archive. Ritual and Leonardo 41, no. 2 (April 2008): 150-51.

(ritual) repetition are ways in which oral histories and tradi

5. FRBR (Functional Requirements for Bibliographic

tions of non-Western, typically tribal, cultures live on. For artists, Records) is a 1998 recommendation of the International

"re-performance proposes a dynamic, living document as a solu

Federation of Library Associations and Institutions (IFLA)

tion to the past's disappearance; it allows a re-experiencing of to restructure catalog databases to more closely reflect the

the work in a time-based, body-based, ephemeral medium and conceptual structure of information resources. FRBR uses an

makes available new experiences of memory."26 This is a notion entity-relationship model of metadata for information objects,

not implicit in the traditional archive, but rather one emerging

instead of the single flat record concept underlying current

with new technologies in much the same way that documenta

cataloging standards. The FRBR model includes four levels of

tion is being changed by them. With the "stockpiling of recorded

representation: work, expression, manifestation, and item. For

speech, image, gesture, the establishment of Oral archives,' and

additional information, see http://www.oclc.org/research/

the collection of 'ethnotexts' ... the recuperation of 'lost histo

activities/past/orprojects/frbr/default.htm and http://

ries'" is being accomplished.27 With the West's desire to retain

www.ifla.org/publications / functional-requirements-f or

everything, to amass "stuff," especially stuff with cultural value,

bibliographic-records.

the archive has had to adapt to the changing ways of doing so.

6. International Federation of Library Associations

If documentation is a collective effort in which multiple frag

and institutions (IFLA) Study Group on the Functional

ments by multiple authors come together to create an essence Requirements for Bibiographic Records, "Functional

of the original whole, then the archive can successfully, at least

Requirements for Bibliographic Records," http://www.ifla.

as much as is possible, preserve performance art. If the archive

org / publications / functional-requirements-f or-bibliographic

is willing to accept not just material remains but physical (re) records.

embodiments of performances, then performance art will not 7. Ibid.

only allow itself to be archived but will expand the scope of the

8. Santone, "Marina Abramovic's Seven Easy Pieces/' 148.

field. The two will not simply coexist but, in effect, will be able 9. Ibid.

to elaborate their individual aims while mforming society about

10. Visual Resources Association, "Ten Key Principles of

their culturally specific desires.

CCO," http: / /www.vrafoundation.org/ccoweb/tenkey.html.

11. The VRA Core is a data standard for the cultural

Conclusion

heritage community that consists of a metadata element set

The catalog and the archive can adapt to performance art to (units of information such as title, location, date, etc.), as well as

the benefit of both. They are vital for performances to continue, an initial blueprint for how those elements can be hierarchically

to live on. Performances do not have to disappear. Yes, the structured. The element set provides a categorical organization

original can never be re-experienced, but the performance can for the description of works of visual culture as well as the

carry on in its documents, extending its influence through time. images that document them. See Library of Congress, "VRA

The catalog and the archive are key in bringing together the Core 4.0 Element Description and Tagging Examples," http://

documents and objects that let performance be re-experienced www.loc.gov/ standards/vr acore/ schemas.html.

in the imagination. In preserving and making accessible the full 12. Paul Clarke and Julian Warren, "Ephemera: Between

range of experiences a performance offers in its afterlife, they Archival Objects and Events," Journal of the Society of Archivists

can better continue the living memory of the performance. From 30, No. 1 (April 2009): 55.

its documentation, the performance can be studied, evaluated, 13. San Francisco Museum of Modern Art, "Matthew

reinterpreted, re-imagined, remembered, and re-performed. The Barney: Drawing Restraint 14," http://www.sfmoma.org/

performance carries on, as expressed eloquently by performance artwork/125734.

artist Kira O'Reilly: 14. Clarke and Warren, "Ephemera," 55.

The work continues to exist in its remains, memories and 15. Kent C. Boese, "Art Ephemera: Relics of the Past, or

Treasures for Posterity?" Art Documentation 25, no. 1 (Spring

objects. The bloodied brandy glasses and table cloth. The

2006): 34.

now fading scars on my body. The stories the guests may or

16. Ibid., 35.

may not have told after the event; private anecdotal accounts

Volume 30, Number 1 ? 2011 ? Art Documentation 31

This content downloaded from

200.144.238.164 on Thu, 11 Nov 2021 18:03:03 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

17. Dadabase, catalog of the Museum of Modern Art Heathfield, Adrian, ed. Small Acts: Performance, the Millennium

Library, http: / / arcade.nyarc.org/ search~S8. and the Marking of Time. London: Black Dog, 2000.

18. Schneider, "Archives: Performance Remains," 101. Jones, Sarah, Daisy Abbott, and Seamus Ross. "Redefining the

19. Santone, "Marina Abramovic's Seven Easy Pieces/' Performing Arts Archive." Archival Science 9, no. 3/4 (2009):

148-49. 165-71.

20. Museum of Modern Art, "Marina Abramovic: The Artist MacDonald, Corina. "Scoring the Work: Documenting Practice

is Present?Portraits," http: / /www.moma.org/interactives / and Performance in Variable Media Art." Leonardo 42, no. 1

exhibitions /2010 / marinaabramovic /. (2009): 59-63.

21. Santone, "Marina Abramovic's Seven Easy Pieces/' 147. Stapleton, Paul. "Dialogic Evidence: Documentation of

22. Ibid., 151. Ephemeral Events." Body, Space & Technology 7, no. 2 (2008):

23. IFLA Study Group, "Functional Requirements." 1-13.

24. Peggy Phelan, Unmarked: The Politics of Performance White, Layna. "Cataloging Contemporary Art: A Sense of Time

(London: Routledge, 1993), 146. and Place." VRA Bulletin 34, no. 1 (Spring 2007): 148-53.

25. Santone, "Marina Abramovic: Seven Easy Pieces" 147.

26. Ibid., 151.

27. Schneider, "Archives: Performance Remains," 102. Christina Manzella,

Graduate Student,

28. Kira O'Reilly, "Unknowing (remains)," in Small Acts:

Performance, the Millennium and the Marking of Time, 120, ed. School oflnformation and Library Science,

Pratt Institute,

Adrian Heathfield (London: Black Dog, 2000).

Brooklyn, New York,

Additional Sources Consulted christina.n.manzella@gmailxom

Auslander, Philip. "The Performativity of Performance Alex Watkins,

Documentation." PAJ: A Journal of Performance and Art 28, Graduate Student,

no. 3 (September 2006): 1-10. School oflnformation and Library Science,

Biesenbach, Klaus. Marina Abramovic: The Artist is Present. New Pratt Institute,

York: Museum of Modern Art, 2010. Brooklyn, New York,

Cook, Jacqueline. "Art Ephemera, aka Ephemeral Traces of alexwatkins@gmail. com

'Alternative Space': The Documentation of Art Events

in London 1995-2005, in an Art Library." PhD diss.,

Goldsmiths, University of London, 2007. http: / /eprints.

gold.ac.uk/3475/.

Edgar Degas

Sculpture

Suzanne Glover Lindsay,

Daphne S. Barbour &

Shelley G. Sturman

With Barbara H. Berrie,

Suzanne Quillen Lomax &

Michael Palmer

Edgar Degas is perhaps best known as a painter, but his most

widely known work is a sculpture, Little Dancer Aged Fourteen. It

is the only sculpture Degas ever showed publicly, though more

than one hundred others were found in his studio after he died.

This groundbreaking volume includes essays on Degas' life and

work, his sculptural technique and materials, and the story of the

sculptures after his death.

National Gallery of Art Systematic Catalogues

408 pages. 221 color illus. 209 halftones. 91/2x11.

Cloth $99.00 978-0-691-14897-7

Distributed for the National Gallery of Art, Washington

See our E-Books at

rcss. ri ncc to . edu

32 Art Documentation ? Volume 30, Number 1 ? 2011

This content downloaded from

200.144.238.164 on Thu, 11 Nov 2021 18:03:03 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

You might also like

- The Object as a Process: Essays Situating Artistic PracticeFrom EverandThe Object as a Process: Essays Situating Artistic PracticeNo ratings yet

- Agency: A Partial History of Live ArtFrom EverandAgency: A Partial History of Live ArtTheron SchmidtNo ratings yet

- Still Life: Ecologies of the Modern Imagination at the Art MuseumFrom EverandStill Life: Ecologies of the Modern Imagination at the Art MuseumNo ratings yet

- The Body at Stake: Experiments in Chinese Contemporary Art and TheatreFrom EverandThe Body at Stake: Experiments in Chinese Contemporary Art and TheatreJörg HuberNo ratings yet

- The Mind of the Artist Thoughts and Sayings of Painters and Sculptors on Their ArtFrom EverandThe Mind of the Artist Thoughts and Sayings of Painters and Sculptors on Their ArtNo ratings yet

- Curriculum: Contemporary Art Goes to SchoolFrom EverandCurriculum: Contemporary Art Goes to SchoolJennie GuyNo ratings yet

- The Idea of Art: Building an International Contemporary Art CollectionFrom EverandThe Idea of Art: Building an International Contemporary Art CollectionNo ratings yet

- Art and Sustainability: Connecting Patterns for a Culture of ComplexityFrom EverandArt and Sustainability: Connecting Patterns for a Culture of ComplexityNo ratings yet

- Artisan or Artist?: A History of the Teaching of Art and Crafts in English SchoolsFrom EverandArtisan or Artist?: A History of the Teaching of Art and Crafts in English SchoolsNo ratings yet

- The Development of Aesthetic Experience: Curriculum Issues in Arts EducationFrom EverandThe Development of Aesthetic Experience: Curriculum Issues in Arts EducationNo ratings yet

- Abstraction in Reverse: The Reconfigured Spectator in Mid-Twentieth-Century Latin American ArtFrom EverandAbstraction in Reverse: The Reconfigured Spectator in Mid-Twentieth-Century Latin American ArtNo ratings yet

- Provoking the Field: International Perspectives on Visual Arts PhDs in EducationFrom EverandProvoking the Field: International Perspectives on Visual Arts PhDs in EducationNo ratings yet

- The Greening of Art: Shifting Positions Between Art and Nature Since 1965From EverandThe Greening of Art: Shifting Positions Between Art and Nature Since 1965No ratings yet

- Experimental Collaborations: Ethnography through Fieldwork DevicesFrom EverandExperimental Collaborations: Ethnography through Fieldwork DevicesNo ratings yet

- The Concept of the New: Framing Production and Value in Contemporary Performing ArtsFrom EverandThe Concept of the New: Framing Production and Value in Contemporary Performing ArtsNo ratings yet

- Inheriting Dance: An Invitation from PinaFrom EverandInheriting Dance: An Invitation from PinaMarc WagenbachNo ratings yet

- The Aesthetic Imperative: Relevance and Responsibility in Arts EducationFrom EverandThe Aesthetic Imperative: Relevance and Responsibility in Arts EducationRating: 1 out of 5 stars1/5 (1)

- Algorithmic and Aesthetic Literacy: Emerging Transdisciplinary Explorations for the Digital AgeFrom EverandAlgorithmic and Aesthetic Literacy: Emerging Transdisciplinary Explorations for the Digital AgeNo ratings yet

- Image Evolution: Technological Transformations of Visual Media CultureFrom EverandImage Evolution: Technological Transformations of Visual Media CultureNo ratings yet

- Engineering Nature: Art and Consciousness in the Post-Biological EraFrom EverandEngineering Nature: Art and Consciousness in the Post-Biological EraNo ratings yet

- The Lure of the Social: Encounters with Contemporary ArtistsFrom EverandThe Lure of the Social: Encounters with Contemporary ArtistsNo ratings yet

- CHANGES (English edition): Berliner Festspiele 2012 – 2021. Formats, Digital Culture, Identity Politics, Immersion, SustainabilityFrom EverandCHANGES (English edition): Berliner Festspiele 2012 – 2021. Formats, Digital Culture, Identity Politics, Immersion, SustainabilityNo ratings yet

- Surface: Matters of Aesthetics, Materiality, and MediaFrom EverandSurface: Matters of Aesthetics, Materiality, and MediaRating: 5 out of 5 stars5/5 (1)

- Images and Identity: Educating Citizenship through Visual ArtsFrom EverandImages and Identity: Educating Citizenship through Visual ArtsRachel MasonNo ratings yet

- Objects in Air: Artworks and Their Outside around 1900From EverandObjects in Air: Artworks and Their Outside around 1900No ratings yet

- Art Without Borders: A Philosophical Exploration of Art and HumanityFrom EverandArt Without Borders: A Philosophical Exploration of Art and HumanityNo ratings yet

- Art Education in a Postmodern World: Collected EssaysFrom EverandArt Education in a Postmodern World: Collected EssaysRating: 5 out of 5 stars5/5 (1)

- Art History and Fetishism Abroad: Global Shiftings in Media and MethodsFrom EverandArt History and Fetishism Abroad: Global Shiftings in Media and MethodsNo ratings yet

- Using Art as Research in Learning and Teaching: Multidisciplinary Approaches Across the ArtsFrom EverandUsing Art as Research in Learning and Teaching: Multidisciplinary Approaches Across the ArtsNo ratings yet

- Inside The Space ReadingsDocument16 pagesInside The Space ReadingsNadia Centeno100% (2)

- Thoughts On Re-Performance, Experience, and Archivism40856573Document16 pagesThoughts On Re-Performance, Experience, and Archivism40856573Nina RaheNo ratings yet

- Transcription of Audio Clip Begins BelowDocument25 pagesTranscription of Audio Clip Begins BelowNina RaheNo ratings yet

- Yoko Onos Cut Piece From Text To Performance and Back AgainDocument14 pagesYoko Onos Cut Piece From Text To Performance and Back AgainPua Barquera MondragónNo ratings yet

- The Implicit Body As Performance - Analyzing Interactive Art20869455Document8 pagesThe Implicit Body As Performance - Analyzing Interactive Art20869455Nina RaheNo ratings yet

- Some Relations Between Conceptual and Performance Art777718Document6 pagesSome Relations Between Conceptual and Performance Art777718Nina RaheNo ratings yet

- Once More... With Feeling - Reenactment in Contemporary Art and Culture20068513Document14 pagesOnce More... With Feeling - Reenactment in Contemporary Art and Culture20068513Nina RaheNo ratings yet

- Scoring The Work - Documenting Practice and Performance in Variable Media Art20532590Document6 pagesScoring The Work - Documenting Practice and Performance in Variable Media Art20532590Nina RaheNo ratings yet

- Performance, a Personal History: Bonnie Marranca's ReflectionsDocument18 pagesPerformance, a Personal History: Bonnie Marranca's ReflectionsNina RaheNo ratings yet

- Marina Abramović's "Seven Easy Pieces" - Critical Documentation Strategies For Preserving Art's History20206555Document7 pagesMarina Abramović's "Seven Easy Pieces" - Critical Documentation Strategies For Preserving Art's History20206555Nina RaheNo ratings yet

- Donald Kelly - Intellectual History in A Global AgDocument14 pagesDonald Kelly - Intellectual History in A Global AgFedericoNo ratings yet

- Marketing and Social Structure in Rural China - 施坚雅 - 18206650 - zhelper-SearchDocument115 pagesMarketing and Social Structure in Rural China - 施坚雅 - 18206650 - zhelper-Search张阴松No ratings yet

- Wicked Problems in Design ThinkingDocument18 pagesWicked Problems in Design ThinkingVagner GodóiNo ratings yet

- Alculturation of M&ADocument13 pagesAlculturation of M&AkrystelNo ratings yet

- Kostas Axelos - Play As The System of SystemsDocument6 pagesKostas Axelos - Play As The System of SystemsSan TurNo ratings yet

- Caste and Class in India (D.D. Kosambi)Document8 pagesCaste and Class in India (D.D. Kosambi)sohaib_nirvan100% (1)

- Vaughan Williams Folk Music No 986Document4 pagesVaughan Williams Folk Music No 986ASDASD DDNo ratings yet

- Review of Ehrhard by Decleer PDFDocument41 pagesReview of Ehrhard by Decleer PDFBhaktapur CommonsNo ratings yet

- Does the Past Have Useful EconomicsDocument29 pagesDoes the Past Have Useful EconomicsAdam JohnosonNo ratings yet

- The Art of Ingmar Bergman PDFDocument27 pagesThe Art of Ingmar Bergman PDFThaiz Araújo FreitasNo ratings yet

- Gottfried Michael Koenig Aesthetic Integration of Computer-Composed ScoresDocument7 pagesGottfried Michael Koenig Aesthetic Integration of Computer-Composed ScoresChristophe RobertNo ratings yet

- Language Interaction Social ProblemDocument3 pagesLanguage Interaction Social ProblemTripty Rani RoyNo ratings yet

- Byzantines and Arabs in The Time of The Early Abbasids PDFDocument21 pagesByzantines and Arabs in The Time of The Early Abbasids PDFmikah9746553No ratings yet

- Fabbri 1982Document14 pagesFabbri 1982Alexandre FerreiraNo ratings yet

- A Model For The Analysis of Folklore Performance in Historical ContextDocument13 pagesA Model For The Analysis of Folklore Performance in Historical ContextAna Savić100% (1)

- 03 Brender 2010 Chile Formation of The Chicago Boys PDFDocument13 pages03 Brender 2010 Chile Formation of The Chicago Boys PDFpagieljcgmailcomNo ratings yet

- Orientalism Reconsidered Author(s) : Edward W. Said Source: Cultural Critique, Autumn, 1985, No. 1 (Autumn, 1985), Pp. 89-107 Published By: University of Minnesota PressDocument20 pagesOrientalism Reconsidered Author(s) : Edward W. Said Source: Cultural Critique, Autumn, 1985, No. 1 (Autumn, 1985), Pp. 89-107 Published By: University of Minnesota PressJoerg BlumtrittNo ratings yet

- Elwin Rogers On NovalisDocument9 pagesElwin Rogers On NovalisWilliam Joseph CarringtonNo ratings yet

- Gita WestDocument12 pagesGita WestSuvradip DasguptaNo ratings yet

- Carine Defoort PDFDocument22 pagesCarine Defoort PDFmufufu7No ratings yet

- Wilson and Graham An Interview With Artist Fred Wilson PDFDocument10 pagesWilson and Graham An Interview With Artist Fred Wilson PDFmary mattinglyNo ratings yet

- Clement Greenberg - Necessity of 'Formalism' (1971)Document6 pagesClement Greenberg - Necessity of 'Formalism' (1971)CristinaMateiNo ratings yet

- 310343Document68 pages310343plotini7No ratings yet

- Using Background Music To Affect The Behavior of Supermarket ShoppersDocument7 pagesUsing Background Music To Affect The Behavior of Supermarket ShoppersIulian BogdanNo ratings yet

- Mulgan Lycophron and Greek Theories of Social ContractDocument9 pagesMulgan Lycophron and Greek Theories of Social Contractasd asdNo ratings yet

- IASTE Journal Explores How Soviets Adopted Regional Styles Under Socialist RealismDocument16 pagesIASTE Journal Explores How Soviets Adopted Regional Styles Under Socialist RealismSouthern FuturistNo ratings yet

- The Teachers of Umar SuhrawardiDocument19 pagesThe Teachers of Umar Suhrawardivlad-bNo ratings yet

- Rawlinson's Memoir on Babylonian and Assyrian InscriptionsDocument192 pagesRawlinson's Memoir on Babylonian and Assyrian InscriptionsBhagawant KamatNo ratings yet

- Notation Material and Form, Ramati, FreemanDocument7 pagesNotation Material and Form, Ramati, FreemanLila Lila100% (1)