Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Thoughts On Re-Performance, Experience, and Archivism40856573

Uploaded by

Nina RaheOriginal Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Thoughts On Re-Performance, Experience, and Archivism40856573

Uploaded by

Nina RaheCopyright:

Available Formats

THOUGHTS ON RE-PERFORMANCE, EXPERIENCE, AND ARCHIVISM

Author(s): Robert C. Morgan

Source: PAJ: A Journal of Performance and Art , SEPTEMBER 2010, Vol. 32, No. 3

(SEPTEMBER 2010), pp. 1-15

Published by: The MIT Press on behalf of Performing Arts Journal, Inc

Stable URL: https://www.jstor.org/stable/40856573

JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide

range of content in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and

facilitate new forms of scholarship. For more information about JSTOR, please contact support@jstor.org.

Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of the Terms & Conditions of Use, available at

https://about.jstor.org/terms

Performing Arts Journal, Inc and The MIT Press are collaborating with JSTOR to digitize,

preserve and extend access to PAJ: A Journal of Performance and Art

This content downloaded from

200.144.238.164 on Thu, 11 Nov 2021 17:47:01 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

THOUGHTS ON RE-PERFORMANCE,

EXPERIENCE, AND ARCHIVISM

Robert C. Morgan

term "re-performance" has a catchy refrain, a resonance with an implicit

political if not seductive undercurrent, specifically in relation to art politics.

To perform on some level is everyone's dream. Yet to re-perform - what is

that? Could it be that re-performance implies a fundamental need for artists to

sustain the importance of their work as "live art" through some form of documenta-

tion? Hypothetically, this should include performances of some merit - whether by

Joseph Beuys, Joan Jonas, Gina Pane, Vito Acconci, Dennis Oppenheim, Nam June

Paik, Alison Knowles, Ann Hamilton, or Carolee Schneemann - that are reproduced

synthetically ad infinitum over a period time in places other than from where they

originated. It is a virtual idea to place performance art in an institution - a modern

art museum, for example - where various works may be represented both as archival

software and as ephemeral artifacts, documents, or notices of one kind or another.

Meanwhile, research coming from various institutions appears bent on mining

the same sources while alternative publications and Websites from less predictable

sources are being ignored.

On one level, the topic of re-performance appears to hold the attention of some

observers in denial of more pressing issues, such as the impact of global economy

on the future of a deeply faulted art market, now involving "live art" - a topic that

deserves serious attention. Instead of going this route, it would appear that the topic

at hand has become typically self-indulgent as increasing numbers of mostly younger

performance artists - and museum curators who support them - are scrambling for

appointments with destiny, hoping their work will be placed on virtual call in the

future. One might say that to contemplate the exigencies of performing a work of

body art by an artist from another time at another youthful moment, based on

extant documentation, archived to the teeth, is like transferring a four-by-five-inch

photographic negative into a digital image or copying a reel-to-reel Portapak tape

into a DVD format. As Philip Auslander correctly, though reticently suggests in his

superlative essay published in PA] 84 (September 2006), there is the question as

to whether performances produced on the basis of archival documentation might

lose some of the vitality of the performance, assuming the vitality was there in the

first place.1 Assuming it was there, the question might arise as to what future artist

would want to do it. Would he or she appear like a performance clone functioning

© 2010 Robert C. Morgan PAJ96(2010), pp. 1-15. ■ 1

This content downloaded from

200.144.238.164 on Thu, 11 Nov 2021 17:47:01 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

as a replica of the original? How different is this from those vapid copies of De

Chiricos early pittura metafísica (1911-16) painted decades later by the same art-

ist? In either case, there are simulations - not even convincing ones, but self-willed

fakes. Whether Abramovic or De Chirico, the artists have fashioned replicas of

works created by themselves at another time period that might easily be translated

in terms of a fetish.

In either case, re-performance carries a heavy dose of overdetermination and there-

fore is liable to transform itself into unmitigated kitsch. One might ask: What is

the essential difference between performing a saccharine tableau vivant of Thomas

Couture's Romans in the Decadence of the Empire (1847) in the mid-twentieth cen-

tury - a century after the painting was shown at the Salon in Paris - or re-performing

Acconci's Seedbed (1972) in the twenty-first century? The unforeseeable problem in

both cases is that the historical moment that contextualizes the performance has

inevitably disappeared. One might speculate that a tableau vivant of the Couture

performed a century later would be appreciated primarily in terms of kitsch. Seedbed^

however, presents a slightly different problem in that it is intrinsically unrelated to

kitsch. Unlike the more traditional performing arts, i.e., theatre, music, or opera,

the historical moment for Acconci's Seedbed has become overtly connected to the

works context.

As a result, it has been locked into a period of time related to the history of con-

temporary art. The only recourse by which to unlock this academic connection to

history would be to transcend the moment of its conception through the literary

imagination. In Acconci's case, one might argue in relation to Heidegger's point

regarding hermeneutics: that to get to the original meaning of the texts in the Greek

tragedies of Aeschylus and Euripides, it is necessary to reinterpret these plays less

from the position of their historical moment, than in relation to the present.2 For

this to succeed, one would have to locate an accurate historical equivalent in order

to properly recontextualize the meaning of the work.

While the process of hermeneutics is a delicate one, one cannot ignore it in relation

to the problem of re-performance. The point is that simply reviving a performance

that was essentially within a microcosm of historical time at its first performance

will have difficulty in surviving unless adjustments are made within the ongoing

present. If this proposition were correct, it would mean that the role of the archivist

in performance art is secondary or even tertiary to the experiential component that

allows for this historical equivalent to emerge. To return the vitality to a work by

Acconci would require some adjustments that may be in opposition to the original

intention. As changes occur within the course of history - an idea that appears in

suspension as the presence of media has had a dominant effect - the legitimacy of

re-performance from an archival point of view will most likely require a serious re-

evaluation. Experience in art - what used to be called aesthetics - is still the ultimate

criterion, whether we are referring to John Dewey, Susanne Langer, or John Berger.

Does performance art require an experience to exist within the history of art, or

does it hold some other archival criterion?

2 ■ PAJ 96

This content downloaded from

200.144.238.164 on Thu, 11 Nov 2021 17:47:01 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

Kata Mejía. Top: Healing, at

The Lab Gallery at The Roger

Smith Hotel, New York City.

Right: Kata Mejía, Mending at

A.I.R Gallery, Brooklyn, NY, as

part of the show Feeling what

no longer is, curated by Serra

Sabuncuoglu. Photos: Huston

Ripley. Courtesy the artist.

MORGAN / Thoughts on Re-Performance, Experience, and Archivism H 3

This content downloaded from

200.144.238.164 on Thu, 11 Nov 2021 17:47:01 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

The Ballerina and the Poet from Loves of a Ballerina, 1986 (2.5 minutes) and in From the Archives of

Modern Art, 1989 (18 minutes). 16mm black and white film. Photo: Courtesy Ronald Feldman Fine

Arts, New York.

4 ■ PAJ 96

This content downloaded from

200.144.238.164 on Thu, 11 Nov 2021 17:47:01 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

Given its radical edge there are some who would argue that performance art is dif-

ferent, and that political and ideological issues have emerged in recent years that set

it apart from art in other mediums. This is an argument worth considering, if one

still subscribes to the notion that mediumistic differences are necessarily parallel to

ideological ones. One of the important issues raised by postmodernism - and by

Rosalind Krauss, in particular, in her brilliant analysis of the time-based work of

the Belgian conceptualist Marcel Broodthaers - is that mediumistic pluralities argue

against limiting an ideological point of view to a single medium.3 If Krauss is correct,

which I believe she is, then performance art is less about limiting itself to a single

course of ideology than opening up new thresholds of psychological, narrative and

interactive content.

A good example would be an exhibition, entitled Feeling what no longer is, which

opened at the A.I.R. Gallery in the DUMBO section of Brooklyn in April 2010.

Curated by Serra Sabuncuoglu, the exhibition included seven artists - all women -

four of whom focused on diverse aspects of performance. They included Eleanor

An tin, Elaine Angelopoulos, Kata Mejia, and Sophie Callé. An tin, who lives in

Southern California, is a preeminent figure in the early history of performance art

coming from a feminist perspective. Her fictional narrative based on Eleanora Anti-

nova, a legendary black ballerina in Diaghilev's Ballets Russes, offers an interesting

intervention into the problem of re-performance by transforming her artistic persona

into the genre of silent film. Antin began as a performance artist, not as aspiring

film actress. The distinction is not incidental. By simulating the appearance of silent

film à la Eisenstein, Antin becomes an auteur taking full control of her medium. In

Rudolf Arnheim's famous book, Film as Art, he argues that silent film offers the pos-

sibility of art.4 Because of the absence of sound there are limitations that necessitate

more subtle maneuvers in communicating emotion. Antin appears to have taken

this idea seriously by adding a remarkable sense of irony in the process.

Rather than fretting over archival notes, documents and related ephemera, Antin's

The Ballerina and the Poet (1986) opens an alternative window to the future of per-

formance art. Essentially the film becomes the complete embodiment of her actions,

the place where everything is finally said, while ingeniously mixing humor and insight

with a full awareness of simulation. In Antin's case, the concept of re-performance is

irrelevant in that the performance does not need to persist as "live art" beyond the

medium of film. Rather than documenting an action on film or video as seen in the

early body art of Acconci, Nauman, and Oppenheim, Antin goes for the fracture of

the story line - the daily foibles, sexual and otherwise, between a struggling poet and

a ballerina - as a kind of absurdist paradoxical overlay. Antin never removes herself

entirely from the complex premise that she is performing. Thus, we gather both her

artistic intention and the narrative effects enhanced through the medium of film as

a simultaneous event. The fact of temporality throughout her performance never

ceases to exist. Put another way, the language of Eisenstein's "film form" continues

to function for Antin in the terms of a perpetual verb conjugation.

MORGAN / Thoughts on Re-Performance, Experience, and Archivism ■ 5

This content downloaded from

200.144.238.164 on Thu, 11 Nov 2021 17:47:01 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

The Colombian-born performance artist, Kata Mejia, also included in the exhibi-

tion at A.I.R., has a different point of view. While she uses the edited DVD format

to document and thereby perpetuate her performances, each of her works appears

to exist in a separate time and space. For example, Mejia performed a work called

Mending at A.I.R. in which she wore a mask made from a cabbage leaf and then

preceded to sew leaves from four heads of cabbage into one giant cabbage. Of

course, the action was absurd, if not impossible, which was part of her intention.

It was a deeply psychological piece as if to "repair the damage" from the past while

also recognizing that the past cannot be repaired, and that life goes on. Given the

sheer energy and emotional intensity that Mejia employs in her work, it would seem

incredible that another artist could deliver the same quality of content through re-

performance. Her statement suggests the she is the one who understands best what

she is attempting to make happen: "My work uses repetition to deal with compul-

sion and those moments when rational thought is so deeply affected by chaos and

disruption as to cause a state of emergency within us."

In works such as A Mark a Day (2004), performed in Chicago, Mejia spent twelve

hours over a duration of six days (approximately two hours a day) drawing a series

of horizontal bands on the walls of a room, using red pigment on a rag inside her

mouth with her hands tied behind her. In a series of works in 2007 for the LAB

Gallery at the Roger Smith Hotel in New York, she dealt with grieving the loss of

her younger brother who was murdered by a major drug cartel in Medellin. One

work, titled Homage to a Hero (Day 1), involved the artist lying in a pool of black

ink surrounded by candles. At regular intervals she would go from the ink pool

to the adjacent wall and create an impression of her figure, visually reminiscent

of Yves Kleins anthropométrie paintings (1960) performed in Paris. But Mejias

actions were more rigidly systematic than Klein's. In Homage to a Hero, the nearly

exact replications of her impressed figure were lined up equidistantly on two walls

over a two-day period in which she made a public performance an hour-and-a-half

each day. In Homage to a Hero (Day 2), she walked to and from the various inked

impressions leaving her trails in flour on the floor over a four-day period. In a third

performance, titled Healing, she placed her head in a wooden bowl filled with red

paint, then pushed it against the wall, allowing the pigment to spill down to the

floor, whereupon she used her hair as a brush to pull the red paint in even row from

one side of the gallery to another. Here again, one can trace this action to an early

Fluxus work by the Korean-born artist Nam June Paik who also used his head as a

brush in the early sixties.

This is to suggest that despite the intensity of Kata Mejias performances, there are

antecedents that are important, often performed with very different intentions. It

would be like saying that once Pollock poured paint, no one else should do it. But the

course of art does not function that way. Nothing comes out of the void. There are

always antecedents. Whether or not they are stated in the writing of critics is another

matter. But to see the continuity of ideas in art - albeit with different intentions - is

important to clarifying the genre of performance. In this sense, Kata Mejia is no

exception. The appropriation of tools within the course of her own clearly developed

6 ■ PAJ 96

This content downloaded from

200.144.238.164 on Thu, 11 Nov 2021 17:47:01 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

actions are important for her work, and no other artist can repeat it exactly. To re-

perform a work by Kata Mejia would subvert the genre of performance art to the

extent that the content would most likely become diffused.

Although the term "re-performance" is recent, the phenomenon is very much a part

of twentieth-century modernism. From a European perspective, there is little doubt

that the Futurist, Constructivist, Dadaist, and Bauhaus artists were all concerned

with sustaining their work, that is, making it appear "contemporary" well into the

future, and therefore becoming part of Art History. From the perspective of what

Americans call "contemporary art," the idea goes back to the 1960s and 1970s when

performance art and body art were at the forefront of a New York revisionist avant-

gardism. Fluxus was clearly prominent in these endeavors. Artists such as Alison

Knowles, Jackson Mac Low, Dick Higgins, Joseph Beuys, Nam June Paik, Yoko

Ono, Benjamin Patterson, and Philip Corner came from diverse backgrounds in

literature, music, dance, philosophy, and mathematics into performance. Although

the Lithuanian immigrant artist George Maciunas may be credited as the architect

of the Fluxus movement in which these artists performed corporeal actions either as

abbreviated or over an extended duration of time, using subversively charged objects,

ideas and other natural substances, it was Allan Kaprow who most effectively defined

the notion of participatory art in the form of his Happenings. From Kap row's point

of view, the Happenings were meant to parallel urban complexity, chaos, conflict, and

dissidence, and thereby contributed metaphorically to the raw material of advanced

art. In 1961, he explained: "Their form is open-ended and fluid; nothing obvious is

sought and therefore nothing is won, except the certainty of a number of occurrences

to which we are more than normally attentive. They exist for a single performance,

or only a few, and are gone forever as new ones take their place."5

As a seminal post-abstract expressionist artist, Kaprow experimented with several

different concepts and processes ultimately related to a new concept of performance.

He was profoundly influenced by Pollock, less in terms of the paintings than in

the way he moved physically as an artist while in the process of working. This led

Kaprow in 1956 to begin thinking of an art of time - what was later called time-

based art - in the sense that art could be fully temporal. As made clear by the artist,

his art existed for the time of "a single performance, or only a few, and are gone

forever." These neo-dadaist, Gutai-inspired Happenings began while Kaprow was

teaching at Douglass College on the campus of Rutgers University in 1958, and

persisted throughout the decade of the 1960s, where several important Happenings

were staged in New York and elsewhere. By the end of that decade, he decided to

move from New York to California and to accept a position teaching at the newly

founded California Institute of the Arts in Valencia. At the outset of the 1970s,

Kaprow began to reconsider the notion of time and duration in his work and to reflect

on the impermanence of the form he had created more than a decade earlier.

As a result, a new direction emerged in his work influenced by behavioral psychology

and sociology, which his chronicler Michael Kirby called "Activities."6 During this

transitional period in his career, Kaprow realized that the ephemerality of this new,

MORGAN / Thoughts on Re-Performance, Experience, and Archivism ■ 7

This content downloaded from

200.144.238.164 on Thu, 11 Nov 2021 17:47:01 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

Allan Kaprow, Likely Stories, 1975. From the Activity Booklet.

Photo: Courtesy Allan Kaprow Estate and Häuser & Wirth.

8 ■ PAJ 96

This content downloaded from

200.144.238.164 on Thu, 11 Nov 2021 17:47:01 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

MORGAN / Thoughts on Re-Performance, Experience, and Archivism M 9

This content downloaded from

200.144.238.164 on Thu, 11 Nov 2021 17:47:01 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

Allan Kaprow, 18 Happenings in 6 Parts, 1959/2006. Version by André Lepecki.

Aüan Kaprow - Art as Life, Haus der Kunst, Munich, Germany.

Photo: Marino Solokhov. Courtesy Allan Kaprow Estate and Hauser & Wirth.

10 ■ PAJ 96

This content downloaded from

200.144.238.164 on Thu, 11 Nov 2021 17:47:01 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

smaller scale work required a more clearly defined set of notations. The Activities

were more precise in their movements and gestures than the Happenings. While

his work continued to flourish in Europe - particularly in Germany - Kaprow was

falling out of favor in the New York art world. Although less in vogue here, his new

work with its emphasis on subjectivity, the body, narrative interpretation, cultural

specificity, and shifting cultural contexts would play an instrumental role in how

his works would be interpreted and understood in Europe. Without intending it,

Kaprow was re-emerging again, this time at the forefront of postmodernism.

In contrast to media-publicized Happenings, such as Courtyard (1962) and House-

hold (1964), the lesser known Activities of the seventies offered a more structuralist

investigation into everyday routines and private interactions. Whereas the Happen-

ings generally involved large groups of participants improvising in relation to vari-

ous loosely built constructions involving wooden scaffolding covered in tar paper

or discarded objects, within a given space, the Activities consisted of predetermined

actions based on highly structured routines derived from everyday life. In works such

as Comfort Zones and Echo-Logy (both from 1975), Kaprow understood the importance

of creating a time-based performance in which a set number of participants interacted

with one another, often through repetition. In Comfort Zones, for example, a male

participant rushes toward a standing female, swerving to avoid her, while trying to

make eye contact. This process is repeated until eye contact is actually made, and

the female participant says the word "now." It was essential that the participants

in Kaprow's Activities were not professional actors. Rather they performed in the

vernacular sense of enacting a role according to a given set of explicit instructions.

(In each case, Kaprow published something similar to "how-to" booklets in which

instructions were accompanied by documentary photographs that described the

actions of the participants.)

The recent incarnation of re-performance comes largely as a result of the extraordinary

packaging and publicity given to Marina Abramovic's Seven Easy Pieces (2005) at

the Guggenheim and her retrospective, titled The Artist is Present, at the Museum of

Modern Art in New York in early 20 10.7 In Seven Easy Pieces, which occurred over

a week's time in November, Abramovic re-presented five works by artist-colleagues,

including Bruce Nauman, Vito Acconci, Valie Export, Gina Pane, and the late Joseph

Beuys. On the sixth and seventh evenings, she re-performed and re-interpreted Lips

of Thomas (original 1973/74) and a new work, titled Entering the Other Side (2005).

The questions and eventual debate centering on the issue of re-performance became

startlingly clear over the course of the week. In contrast to the archival approach to

performance, Abramovic took considerable liberties in terms of how she re-staged

the various events - changing this, adding that - while at the same time inserting,

subtracting and improvising new possibilities and ideas for a re-interpretation of the

original events, both in her own work and in the works by the other artists. There

were, of course, contradictions in these performances in terms of her stated inten-

tions, but these did not seem to interfere with the power of the various works.

MORGAN / Thoughts on Re-Performance, Experience, and Archivism ■ 11

This content downloaded from

200.144.238.164 on Thu, 11 Nov 2021 17:47:01 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

On the other hand, the contradictions seemed to accurately align themselves with

Heidegger's position regarding the Greek plays. To keep these works alive meant

that the artist had to perpetually envision them within the present. From a critical

perspective, Seven Easy Pieces was somehow intentionally, conceptually, visually, and

dramatically more clear than the youthful models used in The Artist is Present to

reconfigure a selection of the more "static" works in her oeuvre, including both her

singular performances and those done with her partner, Ulay, from roughly the mid-

1970s to the late- 1980s. In spite of the artists attempts to engage her performance

students in a kind of physical and mental preconditioning, such as walking nude

in the forest and swimming in cold water, the aura surrounding these vignettes was

remarkably unconvincing. From the perspective of this visitor, there was no energy,

no real spunk.

The experiential aspect of Seven Easy Pieces somehow did not translate to The Artist

is Present, either in terms of the student poses (in which shifts were arranged to give

necessary breaks to these mostly nude participants) or in Abramovic s own perfor-

mance in the Marron Atrium of MoMA where she sat across from museum-goers

with a table between them at regular intervals during museum hours throughout

the course of the exhibition, which was nearly three months. Again, the title piece

performed in the retrospective felt static in the sense that the use of endurance seemed

more imposed than natural. Apparently, the artist was seeking to offer a kind of

transformative experience for her mostly youthful visitors, possibly related to what

she believed they might expect from a Guru in northern India or from an aboriginal

shaman living in central Australia or the Amazon region of Brazil. In any case, a

certain visible posing at the table became inevitable - in spite of the artist's attempts

to avoid it - given the large audience that perpetually stood in this central meeting

space between the rising towers of static art world on all sides. In a way, one might

understand that for a performance artwork to enter a museum over time it would

summarily need to be static. Over the years, attempts to give kinesis or action to

museum interiors have revealed some interesting moments, but the tendency of the

object/viewer relationship continues to predominate through it all.

Concurrently, the revival of interest in re-performance - which arguably had its con-

temporary origins as a self-conscious intention with Kaprow's Activities, and later,

beginning in 1988, in variations on 18 Happenings in 6 Parts (original 1959) - has

emerged as a pronounced, if not competitive pursuit in the field of archivism (author's

word), especially among institutions focused on collecting and maintaining works

of modern and contemporary art. As a result we now have artists' notes, e-files,

sketches, and statements being catalogued along with all manner of photographs,

posters, fliers, cards, relics, properties, vestiges, flight menus, press kits, clippings,

reviews, essays, and publications under the now legitimated institutional category of

performance art. Given the expansion of archival departments in various prestigious

institutions, such as The Museum of Modern Art in New York, archivists doggedly

pursue the acquisition of documents while organizing Smithsonian-style interviews

and symposia with performance artists, entrepreneurs, curators, academic theorists,

organizers, fund- raisers, and - budget permitting - art critics.

12 ■ PAJ 96

This content downloaded from

200.144.238.164 on Thu, 11 Nov 2021 17:47:01 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

Top: Marina Abramovic and Ulay, Point of Contact. Originally performed in 1980 for one hour

at De Appel Gallery, Amsterdam. Production image (black and white) for 16mm film transferred

to video (color, silent). 19:06 min. © 2010 Marina Abramovic. Courtesy Marina Abramovic and

Sean Kelly Gallery/ Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York. Bottom: Point of Contact, reperformed

continuously in shifts throughout the exhibition Marina Abramovic: The Artist Is Present at MoMA,

March 14- May 31, 2010. Pictured in this image: Matthew Rogers, Rebecca Davis (left to right).

Photo: Scott Rudd. Courtesy Museum of Modern Art, New York.

MORGAN / Thoughts on Re-Performance, Experience, and Archivism ■ 13

This content downloaded from

200.144.238.164 on Thu, 11 Nov 2021 17:47:01 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

Relative to 18 Happening in 6 Parts, and its venues of re-performance, there have

been several different attempts, including one sponsored by the University of Texas at

Arlington (1988) and performed in New York as part of the Preceding retrospective

(partially sponsored by Zabriskie Gallery) and a second sponsored by Performa in

New York in 2007. In contrast to the posthumous 2007 re-creation of the Happening,

the artist decided that for the earlier Arlington/New York performance, he would

work according to a structural mode and radically alter the surface appearance of

the original Happening in the Reuben Gallery in New York. Instead of translucent

plastic compartments in a static interior space as in 1959, the artist elected to go

out-of-doors into the streets of Manhattan and have the participants arrange meet-

ings with one another in which they exchanged pockets full of hay throughout the

course of a day. (Given that cell phones were not prevalent even three decades later,

these meetings proved somewhat precarious.) Later in the afternoon, the partici-

pants reconvened at a loft in lower Manhattan to discuss their encounters and the

meaning of the event. This was, indeed, a re-performance, but radically different

in its appearance from the original version.8 This suggests that Kaprow understood

the structural basis of his work as a work of art that could transcend the obvious

appearance of stasis. In 1988 - nearly thirty years after the original - kinesis replaced

stasis in terms of its spatial referent.

In recent years, the artist Tino Sehgal has made his presence known in New York

after working throughout Europe for several years. It was the decision of the Guggen-

heim Museum of Art to introduce him with a couple of works, one older, titled

Kiss (2002), and a second, titled This Progress (2006). Generally, Sehgal presents his

work in terms of nearly invisible events, intimate exchanges, and songs (more like

ditties, really), either within the context of existing exhibitions or, in the case of

Guggenheim, as an addendum to an ongoing fiftieth-year celebration of the museum

architecture and its architect, Frank Lloyd Wright.9 There are no objects in Sehgals

performative works. There are no statements, no placards on the wall, no catalogues.

He refuses to call his work performance art or happenings. Rather they exist as a

kind óf "staged situation," thus recalling the spontaneous conversion pieces of the

conceptual artist Ian Wilson from the late- 1960s and 1970s.10

In short, there would be very little to archive, but infinite possibilities to re-perform.

The question for the future of this art may hinge on whether or not Sehgals "staged

situations" will continue to have vitality once they have outlived their historical

moment or what some might call a trend. Yet there is another possibility. Maybe

the art of the future will forego the necessity of spunk in favor of blankness. Indeed,

there are signs of this happening in other reaches of the art world as contemporary

art is moving ever closer to becoming a form of economic totalism, thus completely

erasing any need to discern qualitative differences. If such a scenario would to become

possible, then re-performance might become the simulation of what art once was

and thus the disappearance of any need for originality or diversity within the human

experience. Without the tactile world, there can no history; and where there is no

history, there can no art.

14 ■ PAJ 96

This content downloaded from

200.144.238.164 on Thu, 11 Nov 2021 17:47:01 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

Can archivism save art from disappearing? It depends on what we really want to

do, and on what we hope to achieve. What is the positive side to having virtual

museums? Do we really need to save all the objects, actions, and documents so they

can be instantly programmed for re-performance in the future? This is, of course,

within the realm of possibility. But the question still remains whether anyone would

care enough to retrieve them. In many ways, this is a question larger than art, but

one that is unavoidable if art is to remain the repository of experience by people in

future generations who will live, love, care, work, think, and play, very much like

ourselves.

NOTES

1. Philip Auslander, "The Performativity of Performance Documentation," PAJ: A Jou

of Performance and Art 84 (September 2006).

2. Richard E. Palmer, Hermeneutics, Chicago, IL: Northwestern University Press, 19

3. Rosalind Krauss, "A Voyage on the North Sea" Art in the Age of the Post-Medium C

dition. London: Thames and Hudson, 1999.

4. Rudolf Arheim, Film As Art, Berkeley, CA: University of California Press, 19

[1933].

5. Allan Kaprow, "Happenings in the New York Scene" in Essays on The Blurring of Art

and Life, Jeff Kelley, ed., Berkeley, CA: University of California Press, 1993, 16-17.

6. Michael Kirby, "The Activity: A New Art Form" in The Art of Time, New York: Dut-

ton, 1969.

7. Both works are extensively documented and discussed in Marina Abramovic: The Artist

is Present, Klaus Biesenbach, ed., New York: The Museum of Modern Art, 2010. The exhibi-

tion of The Artist is Present ran from March 14-May 31, 2010.

8. E-mail, dated May 29, 2010, sent from Tamara Bloomberg, representing the Allan

Kaprow Estate, regarding details on the 1988 Arlington/New York re-performance of

18 Happenings in 6 Parts.

9. Tino Sehgal was shown at the Guggenheim Museum, New York, January 29- March

10, 2010.

10. "Ian Wilson" in Ursula Meyer, ed., Conceptual Art, New York: Dutton, 1972, 220-221.

ROBERT C. MORGAN is an international critic, curator, and artist, who

lives in New York City. He holds an advanced degree in Sculpture (MFA),

a PhD in contemporary art history, and is Adjunct Professor of Fine Art

at Pratt Institute in Brooklyn, New York. As a critic, he is the author of

many books, including Art into Ideas: Essays on Conceptual Art, The End of

the Art World, The Artist and Globalization, and Bruce Nauman (ed.), with

numerous essays translated into eighteen languages. Morgan has curated

over seventy exhibitions and, in 1999, received the first Areale award for

International Art Criticism in Salamanca (Spain).

MORGAN / Thoughts on Re-Performance, Experience y and Archivism ■ 15

This content downloaded from

200.144.238.164 on Thu, 11 Nov 2021 17:47:01 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

You might also like

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)From EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Rating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (121)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryFrom EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (231)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceFrom EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (588)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaFrom EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (266)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItFrom EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (838)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerFrom EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (271)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingFrom EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (400)

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeFrom EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (5794)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyFrom EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (2259)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeFrom EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (537)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreFrom EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (1090)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersFrom EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (345)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnFrom EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (234)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesFrom EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (821)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceFrom EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (895)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaFrom EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (45)

- Kingmaker With Mike Rashid - 4 Weeks To Fighting ShapeDocument6 pagesKingmaker With Mike Rashid - 4 Weeks To Fighting ShapeRayNo ratings yet

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureFrom EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (474)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealFrom EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (74)

- The Great Gatsby - Oraganized Crime in The 1920sDocument14 pagesThe Great Gatsby - Oraganized Crime in The 1920sapi-359544484No ratings yet

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)From EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Rating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (98)

- Amanpulo FactsheetDocument6 pagesAmanpulo FactsheetAlexNo ratings yet

- Antrieb Actuators O & M CatalogueDocument12 pagesAntrieb Actuators O & M Catalogueysr3ee6926100% (3)

- Up PeriscopeDocument145 pagesUp Periscoperemow100% (4)

- Actor NotesDocument2 pagesActor NotesMICHAEL PRITCHARDNo ratings yet

- FINAL EDIT 2011grad ScriptDocument15 pagesFINAL EDIT 2011grad ScriptYemmy96% (56)

- Selection1 PDFDocument198 pagesSelection1 PDFjONATHANNo ratings yet

- Technology Features: New AF System & Wide ISO Speed RangeDocument8 pagesTechnology Features: New AF System & Wide ISO Speed RangeАлександар ДојчиновNo ratings yet

- Starch and Cereals Recipe BookDocument21 pagesStarch and Cereals Recipe BookWinsher PitogoNo ratings yet

- DX DiagDocument21 pagesDX Diagstax9936No ratings yet

- The Hundred Dresses - IIDocument3 pagesThe Hundred Dresses - IIBIHI CHOUDHURINo ratings yet

- Filmes e Series 2022Document5 pagesFilmes e Series 2022Diogo SilvaNo ratings yet

- Cts Spare Stock - Kasi Sales - 31!12!19.Document7 pagesCts Spare Stock - Kasi Sales - 31!12!19.saptarshi halderNo ratings yet

- New Year's EveDocument1 pageNew Year's EveEdyta MacNo ratings yet

- AutoTap ManualDocument54 pagesAutoTap ManualDaniel BernardNo ratings yet

- According To PlutarchDocument10 pagesAccording To Plutarchwillrg9No ratings yet

- The 28-Day Crossfit Program For BeginnersDocument2 pagesThe 28-Day Crossfit Program For BeginnersAditya Pratap SinghNo ratings yet

- DeepinMind NVR Datasheet DS-7608NXI-M2 - XDocument8 pagesDeepinMind NVR Datasheet DS-7608NXI-M2 - XKunal GuptaNo ratings yet

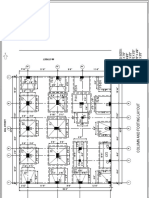

- Column and Footing LayoutDocument1 pageColumn and Footing LayoutV.m. RajanNo ratings yet

- Paul ButterfieldDocument9 pagesPaul ButterfieldgojuilNo ratings yet

- PARAMORE-Rose Color Boy Bass TabDocument1 pagePARAMORE-Rose Color Boy Bass TabGerardo Herrera-BenavidesNo ratings yet

- Sach-A2 (Có Đáp Án)Document41 pagesSach-A2 (Có Đáp Án)Đức Luận TạNo ratings yet

- Defa Wahyu PratamaDocument2 pagesDefa Wahyu PratamaShandi RizkyNo ratings yet

- God Is Here by Darlene ZschechDocument1 pageGod Is Here by Darlene ZschechEmanuel ScomparinNo ratings yet

- Music, Arts, Pe & HealthDocument7 pagesMusic, Arts, Pe & HealthKesh AceraNo ratings yet

- Crazy Gang PDFDocument3 pagesCrazy Gang PDFstartrekgameNo ratings yet

- Huawei Modem E960 UpgradeDocument13 pagesHuawei Modem E960 Upgradebearking80No ratings yet

- Cosmos Club Partners, The Savile Club - Reciprocal ClubsDocument17 pagesCosmos Club Partners, The Savile Club - Reciprocal ClubsSinead MarieNo ratings yet

- BLT Press Opening 2023Document2 pagesBLT Press Opening 2023Mirna HuhojaNo ratings yet