Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Mal Et Al. - 2019 - Depression and Anxiety As A Risk Factor For Myocardial Infarction-Annotated

Uploaded by

Júlia CostaOriginal Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Mal Et Al. - 2019 - Depression and Anxiety As A Risk Factor For Myocardial Infarction-Annotated

Uploaded by

Júlia CostaCopyright:

Available Formats

Open Access Original

Article DOI: 10.7759/cureus.6064

Depression and Anxiety as a Risk Factor for

Myocardial Infarction

Kheraj Mal 1 , Inayatullah D. Awan 2 , Jaghat Ram 3 , Faizan Shaukat 4

1. Cardiology, National Institute of Cardiovascular System, Sukkur, PAK 2. Psychiatry, Ghulam

Muhammad Mahar Medical College, Sukkur, PAK 3. Cardiology, Ghulam Muhammad Mahar Medical

College, Sukkur, PAK 4. Internal Medicine, Jinnah Postgraduate Medical Centre, Karachi, PAK

Corresponding author: Kheraj Mal, drkheraj@yahoo.com

Abstract

Introduction: Patients having a cardiovascular disease experience negative states of

psychology. An increased incidence of coronary artery disease is attributed to both depression

and anxiety.

Materials and methods: In this retrospective study, the Hospitalized Anxiety and Depression

Scale (HADS) was used to determine anxiety and depression in stable patients of myocardial

1-2

2 notes:

infarction (MI) at the time of their discharge. All responses were based on the patients’

perceptions two weeks prior to acute MI event. SPSS version 21.0 was used for data entry and

analysis.

Results: The mean age of the participants in our study was 49.09±5.61 years. About 52.83%

(n=28) and 58.49% (n=31) participants suffered from anxiety and depression two weeks prior to

their myocardial infarction.

Conclusion: Depression and anxiety can be a risk factor for myocardial infarction in susceptible

individuals. Attention should be given to mental well-being, and a multi-disciplinary

03

management approach should be taken for these patients including psychiatry and psychology.

Julia Santos

Categories: Psychiatry, Cardiology

Keywords: myocardial infarction, depression, anxiety, risk factors

Introduction

Patients with cardiovascular disease (CVD) experience psychological states that are usually

negative. An increased incidence of coronary artery disease is attributed to both depression and

Received 10/25/2019 anxiety [1]. The occurrence and sometimes the progression of CVD are due to anxiety. Coronary

Review began 10/27/2019 artery disease (CAD) can also develop due to anxiety in patients without existing CVD. As

Review ended 10/31/2019

reported by Roest and colleagues in a meta-analysis, including 250,000 subjects and 20 studies,

4-5 Published 11/03/2019

2 notes:

anxiety increases the risk of CAD occurrence by 26% along with other medical factors [2]. Along

© Copyright 2019 with this, CVD can also be developed by depression in people who are initially healthy [3]. The

Mal et al. This is an open access

risk of the onset of CAD is 1.64 times more in patients with symptoms of depression [4].

article distributed under the terms of

the Creative Commons Attribution

License CC-BY 3.0., which permits Despite the fact that there were significant overall findings, only 10 out of 20 studies report a

unrestricted use, distribution, and significant association between anxiety and the occurrence of CAD in multivariate analyses.

reproduction in any medium, provided

This means that there can be a heterogeneous link between these two mental health issues and

the original author and source are

credited. myocardial infarction [1]. Also, inconsistent outcomes have been reported by studies on

depression being a risk factor for myocardial infarction (MI) [5]. To our knowledge, Pakistan

How to cite this article

Mal K, Awan I D, Ram J, et al. (November 03, 2019) Depression and Anxiety as a Risk Factor for

Myocardial Infarction. Cureus 11(11): e6064. DOI 10.7759/cureus.6064

does not have any data available that examines the impact of psychological symptoms like

depression and anxiety in acute MI. Therefore, this study is being performed, keeping in view

the above gaps in knowledge.

Materials And Methods

This retrospective study was conducted in the National Institute of Cardiovascular Disease,

06

Sukkur, from 1st Jan to 30th Sept 2019. All participants of both genders admitted with MI who

Julia Santos were stable at the time of discharge were included in this study after informed consent. The

institutional review board approved the study.

During the study period, 222 patients were admitted with MI. There were 27 mortalities, 58

were excluded as they were smoker, diabetic, hypertensive, or obese (body mass index (BMI) >30

kg/m2), and 84 patients did not consent to participate. The remaining 53 participants were

included in the study.

Hospitalized Anxiety and Depression Scale (HADS) was administered to all participants. All

responses were based on the feelings of the patients two weeks prior to their MI. HADS has

robust psychometric properties and is brief and easy to administer. It consists of 14 items

divided into two 21-point subscales for anxiety and depression, and a score of ≥8 was

considered to be abnormal for either anxiety or depression [6].

Data were analyzed using SPSS Version 21.0 (IBM Corp., Armonk, NY). Mean, and standard

deviation (SD) was calculated for continuous variables such as age and HADS score. Frequencies

and percentages were calculated for categorical variables, including gender, type of MI, and

HADS score.

Results

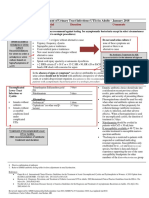

The mean age of participants in our study was 49.1 ± 5.6 years. There were more men than

women (58% vs. 42%). ST elevated MI (STEMI) was more common (55%). As many as 53%

suffered from anxiety and 59% from depression two weeks prior to their MI episode (Table 1).

2019 Mal et al. Cureus 11(11): e6064. DOI 10.7759/cureus.6064 2 of 5

Patient Characteristics Frequency (%)

Age 49.1 ±5.6

Gender

Male 31 (58.5%)

Female 22 (41.5%)

Types Myocardial Infarction

STEMI 29 (54.7%)

NSTEMI 24 (45.3%)

HADS Score

Anxiety (Mean ± SD) 6.9 ± 4.6

Depression (Mean ± SD) 7.2 ± 4.8

Participants with Anxiety 28 (52.8%)

Participants with Depression 31 (58.5%)

TABLE 1: Demographics and Frequencies of Anxiety and Depression

Abbreviations: HADS, Hospitalized Anxiety and Depression Scale; NSTEMI, Non ST Elevated Myocardial Infarction; SD, Standard

Deviation; STEMI, ST Elevated Myocardial Infarction.

Discussion

A complex association exists between anxiety and cardiovascular (CV) health; therefore, a

comparison to assess how strong a relationship exists between anxiety and cardiovascular

disease (CVD) occurrence along with other psychological elements is highly needed. There was

a 46% increased risk of CVD due to depression, as reported by Van der Kooy et al. [7]. Another

study conducted by Roest et al. showed a 55% increased risk of cardiac death in patients with

depression that was comparable to the effect of anxiety [2]. Several mechanisms might explain

the adverse relation between anxiety and heart disease. In various studies, anxiety has been

linked with atherosclerosis, decreased heart rate, and risk of ventricular arrhythmias [8-10].

The results of our study show that 52.83% of patients had anxiety two weeks before they had

myocardial infarction. Anxiety can be a usual reaction to a tense or stressful situation, e.g., an

acute cardiac event. However, if anxiety propels patients to get more involved in treatment

(e.g., daily workout, adherence to therapy), it can be useful for the patients. But if anxiety

persists for long periods of time or if it is in excess, then it can be harmful for psychological

health and the overall well-being of an individual [4]. The risk of the incidence of CVD increases

by 26% in anxious people, as shown by Roest et al. [2]. The risk of cardiac mortality also

specifically increases due to anxiety, as there is a 48% increase in the risk of cardiac deaths in

anxious persons. There also has been a relationship between anxiety and the occurrence of

non-fatal MI [2].

2019 Mal et al. Cureus 11(11): e6064. DOI 10.7759/cureus.6064 3 of 5

As already discussed, 58.5% of patients had depression just two weeks before they had their MI

attack. Depression is linked to an elevated risk of chronic diseases that cover chronic heart

disease (CHD) as well, as shown by a large number of epidemiological studies during the last 10

years. Depression has found to be an independent risk factor for CVD, apart from the

conventional known risk factors that include obesity, smoking, diabetes, sedentary lifestyle,

and hypertension, as reported by Meng et al. [11]. Moreover, the negative impact of depression

over cardiac parameters can be triggered by both biological and behavioral factors. The major

behavioral factors include smoking, non-compliance with cardiac medications, and physical

inactivity [12].

The study was first of its kind to evaluate study depression and anxiety as a risk factor for

myocardial infarction in our demographic region. We tried to eliminate confounding factors by

excluding smokers, diabetic, hypertensive, and obese patients. However, it has its

limitations. First, it was a single-center study; hence, the results cannot be projected to a

broader population. Second, the sample size was small. Third, since it was a retrospective

study, patients may not remember their symptoms, which may have caused bias in calculating

depression and anxiety scores. Despite our best effort, there were still a few confounding

factors such as previous history of MI, family history, and lack of physical exercise. There was a

high rate of non-consent (84/222; 37.8%), which indicates the resistance of the population

towards discussing mental health issues and psychological well-being. Further large scale

prospective trials are needed to understand and establish the definite role of anxiety and

depression in myocardial infarction.

Conclusions

In conclusion, this study suggests depression and anxiety are significantly associated with an

increased risk of myocardial infarction. Because anxiety, depression, and myocardial infarction

are highly prevalent, they have significant implications for public health. Prevention and

treatment of depression and anxiety may reduce myocardial infarction.

Additional Information

Disclosures

Human subjects: Consent was obtained by all participants in this study. Ghulam Muhammad

Mahar Medical College issued approval GMMMC/18/12/16C. Animal subjects: All authors have

confirmed that this study did not involve animal subjects or tissue. Conflicts of interest: In

compliance with the ICMJE uniform disclosure form, all authors declare the following:

Payment/services info: All authors have declared that no financial support was received from

any organization for the submitted work. Financial relationships: All authors have declared

that they have no financial relationships at present or within the previous three years with any

organizations that might have an interest in the submitted work. Other relationships: All

authors have declared that there are no other relationships or activities that could appear to

have influenced the submitted work.

References

1. Celano CM, Daunis DJ, Lokko HN, Campbell KA, Huffman JC: Anxiety disorders and

cardiovascular disease. Curr Psychiatry Rep. 2016, 18:101. 10.1007/s11920-016-0739-5

2. Roest AM, Martens EJ, de Jonge P, Denollet J: Anxiety and risk of incident coronary heart

disease: a meta-analysis. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2010, 56:38-46. 10.1016/j.jacc.2010.03.034

3. Rugulies R: Depression as a predictor for coronary heart disease: a review and meta-analysis .

Am J Prev Med. 2002, 23:51-61. 10.1016/s0749-3797(02)00439-7

4. Wulsin LR, Singal BM: Do depressive symptoms increase the risk for the onset of coronary

disease? A systematic quantitative review. Psychosom Med. 2003, 65:201-210.

2019 Mal et al. Cureus 11(11): e6064. DOI 10.7759/cureus.6064 4 of 5

10.1097/01.psy.0000058371.50240.e3

5. Wu Q, Kling JM: Depression and the risk of myocardial infarction and coronary death: a meta-

analysis of prospective cohort studies. Medicine. 2016, 95:2815.

10.1097/MD.0000000000002815

6. Zhang L, Tu L, Chen J, et al.: Health-related quality of life in gastroesophageal reflux patients

with noncardiac chest pain: Emphasis on the role of psychological distress. World J

Gastroenterol. 2017, 23:127-134. 10.3748/wjg.v23.i1.127

7. Van der Kooy K, van Hout H, Marwijk H, Marten H, Stehouwer C, Beekman A: Depression and

the risk for cardiovascular diseases: systematic review and meta analysis. Int J Geriatr

Psychiatry. 2007, 22:613-626. 10.1002/gps.1723

8. Paterniti S, Zureik M, Ducimetière P, Touboul PJ, Fève JM, Alpérovitch A: Sustained anxiety

and 4-year progression of carotid atherosclerosis. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2001,

21:136-141. 10.1161/01.atv.21.1.136

9. Martens EJ, Nyklícek I, Szsabó BM, Kupper N: Depression and anxiety as predictors of heart

rate variability after myocardial infarction. Psychol Med. 2008, 38:375-383.

10.1017/S0033291707002097

10. Van den Broek KC, Nyklícek I, van der Voort PH, Alings M, Meijer A, Denollet J: Risk of

ventricular arrhythmia after implantable defibrillator treatment in anxious Type D patients. J

Am Coll Cardiol. 2009, 54:531-537. 10.1016/j.jacc.2009.04.043

11. Meng L, Chen D, Yang Y, Zheng Y, Hui R: Depression increases the risk of hypertension

incidence: a meta-analysis of prospective cohort studies. J Hypertens. 2012, 30:842-851.

10.1097/HJH.0b013e32835080b7

12. Freedland KE, Carney RM: Depression as a risk factor for adverse outcomes in coronary heart

disease. BMC Med. 2013, 11:131. 10.1186/1741-7015-11-131

2019 Mal et al. Cureus 11(11): e6064. DOI 10.7759/cureus.6064 5 of 5

Annotations

Depression and Anxiety as a Risk Factor for Myocardial

Infarction

Mal, Kheraj; Awan, Inayatullah; Ram, Jaghat; Shaukat, Faizan

01 Julia Santos Page 1

17/8/2021 0:33

02 Julia Santos Page 1

17/8/2021 0:34

03 Julia Santos Page 1

17/8/2021 0:36

04 Julia Santos Page 1

17/8/2021 0:38

05 Julia Santos Page 1

17/8/2021 0:38

06 Julia Santos Page 2

17/8/2021 0:40

You might also like

- Carcinogenic Mind. The Psychosomatic Mechanisms of Cancer: Contribution of chronic stress and emotional attitudes to the onset and recurrence of disease, how to prevent it and help the treatmentFrom EverandCarcinogenic Mind. The Psychosomatic Mechanisms of Cancer: Contribution of chronic stress and emotional attitudes to the onset and recurrence of disease, how to prevent it and help the treatmentNo ratings yet

- Suicide Risk in Chronic Heart Failure Patients and Its Association With Depression, Hopelessness and Self Esteem-2019Document4 pagesSuicide Risk in Chronic Heart Failure Patients and Its Association With Depression, Hopelessness and Self Esteem-2019Juan ParedesNo ratings yet

- (Roest2010)Document9 pages(Roest2010)Andoni Trillo PaezNo ratings yet

- Shao2020 PDFDocument7 pagesShao2020 PDFAndrea ZambranoNo ratings yet

- Medi 97 E10919Document4 pagesMedi 97 E10919oktaviaNo ratings yet

- Ansiedade 04Document9 pagesAnsiedade 04Karina BorgesNo ratings yet

- Anxiety and CVDDocument11 pagesAnxiety and CVDFabricio A BorgesNo ratings yet

- Depression, Anxiety, and Stress Among Hawler Medical University, Erbil, IraqDocument10 pagesDepression, Anxiety, and Stress Among Hawler Medical University, Erbil, Iraqkamel abdiNo ratings yet

- Ams 12 24223Document11 pagesAms 12 24223amad markaNo ratings yet

- Anxiety and Depression in Patients With Coronary Heart Disease: A Study in A Tertiary HospitalDocument6 pagesAnxiety and Depression in Patients With Coronary Heart Disease: A Study in A Tertiary Hospitalcindyaperthy22No ratings yet

- Morbid Anxiety As A Risk Factor in Patients With Somatic Diseases A Review of Recent FindingsDocument9 pagesMorbid Anxiety As A Risk Factor in Patients With Somatic Diseases A Review of Recent FindingsAdelina AndritoiNo ratings yet

- Annotated BMRI2021 6698521 1Document8 pagesAnnotated BMRI2021 6698521 1fabiana yarlequeNo ratings yet

- SynopsisDocument24 pagesSynopsis6rqwhg67zvNo ratings yet

- Rozanski 2019 Oi 190464Document12 pagesRozanski 2019 Oi 190464Iki Jam TanganNo ratings yet

- Nihms 1645342Document16 pagesNihms 1645342HandayaniNo ratings yet

- 107PMC-Structural Model of Psychological Risk and Protective Factors Affecting On Quality of Life in Patients With Coronary Heart Disease A Psychocardiology Model-NekoueiDocument10 pages107PMC-Structural Model of Psychological Risk and Protective Factors Affecting On Quality of Life in Patients With Coronary Heart Disease A Psychocardiology Model-NekoueiCristina Teixeira PintoNo ratings yet

- Association Between State and Trait Anxiety and CaDocument1 pageAssociation Between State and Trait Anxiety and CascribidisshitNo ratings yet

- The Relationship Between Depression, AnxietyDocument14 pagesThe Relationship Between Depression, Anxietygerard sansNo ratings yet

- International Journal of Cardiology: A B A B B C D B e D F G H G F I B C DDocument6 pagesInternational Journal of Cardiology: A B A B B C D B e D F G H G F I B C DFrederick WeeNo ratings yet

- Association Between Comorbid Anxiety Diabetes Control and Overall Medical Burden in Population With Serious Mental Illness and DiabetesDocument12 pagesAssociation Between Comorbid Anxiety Diabetes Control and Overall Medical Burden in Population With Serious Mental Illness and DiabetesYuliaNo ratings yet

- Depression After Stroke-Frequency, Risk Factors, and Mortality OutcomesDocument2 pagesDepression After Stroke-Frequency, Risk Factors, and Mortality OutcomesCecilia FRNo ratings yet

- Spinal Cord Injury and Migraine Headache: A Population-Based StudyDocument12 pagesSpinal Cord Injury and Migraine Headache: A Population-Based StudyrranindyaprabasaryNo ratings yet

- Management of Depression in Elderly Stroke Patients: Neuropsychiatric Disease and TreatmentDocument20 pagesManagement of Depression in Elderly Stroke Patients: Neuropsychiatric Disease and TreatmentRDNo ratings yet

- Feng Et Al. - 2019 - Prevalence of Depression in Myocardial Infarction A PRISMA-compliant Meta-Analysis-AnnotatedDocument12 pagesFeng Et Al. - 2019 - Prevalence of Depression in Myocardial Infarction A PRISMA-compliant Meta-Analysis-AnnotatedJúlia CostaNo ratings yet

- Factor Associated With Stress, Anxiety, and Depression Among Medical Students in Tabuk City, 2022Document18 pagesFactor Associated With Stress, Anxiety, and Depression Among Medical Students in Tabuk City, 2022IJAR JOURNALNo ratings yet

- Stress Reduction in The Secondary Prevention of Cardiovascular DiseaseDocument10 pagesStress Reduction in The Secondary Prevention of Cardiovascular DiseaseNeilermindNo ratings yet

- Factors Affecting Post-StrokeDocument12 pagesFactors Affecting Post-StrokeSitti Rosdiana YahyaNo ratings yet

- 435 Full PDFDocument8 pages435 Full PDFRizky Qurrota AinyNo ratings yet

- Makalah Diare Pada AnakDocument15 pagesMakalah Diare Pada AnakWahyu WijayaNo ratings yet

- Wu, Kling - Unknown - Depression and The Risk of Myocardial Infarction and Coronary Death A Meta-Analysis of Prospective Cohort Studies-AnnotatedDocument14 pagesWu, Kling - Unknown - Depression and The Risk of Myocardial Infarction and Coronary Death A Meta-Analysis of Prospective Cohort Studies-AnnotatedJúlia CostaNo ratings yet

- Psycho CardiologyDocument10 pagesPsycho Cardiologyciobanusimona259970No ratings yet

- Late-Life Depression, Mild Cognitive Impairment, and DementiaDocument7 pagesLate-Life Depression, Mild Cognitive Impairment, and DementiaRodrigo Aguirre BáezNo ratings yet

- Anxiete Et Depression Chez Les Patients Hospitalises en CardiologieDocument6 pagesAnxiete Et Depression Chez Les Patients Hospitalises en CardiologieIJAR JOURNALNo ratings yet

- Cardiovascular Disease and Meaning in Life A Systematic Literature Review and Conceptual ModelDocument10 pagesCardiovascular Disease and Meaning in Life A Systematic Literature Review and Conceptual ModelDoctor ArisNo ratings yet

- Journal of A Ffective Disorders: Research PaperDocument7 pagesJournal of A Ffective Disorders: Research PaperLast ChildNo ratings yet

- Pone 0261785Document15 pagesPone 0261785lizardocdNo ratings yet

- Heart & Lung: Care of Patients With Cardiac SurgeryDocument6 pagesHeart & Lung: Care of Patients With Cardiac SurgeryMarina UlfaNo ratings yet

- Factors Associated With Post-Stroke Depression and Fatigue: Lesion Location and Coping StylesDocument8 pagesFactors Associated With Post-Stroke Depression and Fatigue: Lesion Location and Coping StylesnurhayanaNo ratings yet

- Cancer Information Overload and Death Anxiety Predict Health AnxietyDocument8 pagesCancer Information Overload and Death Anxiety Predict Health AnxietyRobynNo ratings yet

- Ijerph 19 11496Document18 pagesIjerph 19 11496Ejemai EboreimeNo ratings yet

- Professional Med J Q 2015 22 6 723 732 PDFDocument10 pagesProfessional Med J Q 2015 22 6 723 732 PDFRaggil SulizaNo ratings yet

- 11.04.2024 OriginalDocument19 pages11.04.2024 Originaltafazzal.eduNo ratings yet

- Depresi Pada LansiaDocument8 pagesDepresi Pada LansiasasadaraNo ratings yet

- Psychological Distress Linked To Fatal Ischemic Stroke in Middle-Aged MenDocument3 pagesPsychological Distress Linked To Fatal Ischemic Stroke in Middle-Aged MenOlivera VukovicNo ratings yet

- Artículo Evidencia de Recaídas (Hardelveld)Document8 pagesArtículo Evidencia de Recaídas (Hardelveld)María CastilloNo ratings yet

- Mental Health in Student Athletes - Associations With Sleep Duration, Sleep Quality, Insomnia, Fatigue, and Sleep Apnea SymptomsDocument16 pagesMental Health in Student Athletes - Associations With Sleep Duration, Sleep Quality, Insomnia, Fatigue, and Sleep Apnea SymptomsReynaldy Anggara SaputraNo ratings yet

- Asai 2006 Burnout - and - Pal - Care - in - Japan - PsychooncolDocument8 pagesAsai 2006 Burnout - and - Pal - Care - in - Japan - PsychooncolDaniela MunteleNo ratings yet

- GMHAT - Cardiac Patients Reino UnidoDocument7 pagesGMHAT - Cardiac Patients Reino UnidoIleana AjaNo ratings yet

- 1 s2.0 S0147956318301559Document7 pages1 s2.0 S0147956318301559Marina UlfaNo ratings yet

- A Review of The Affects of Worry and GAD Upon CV Health and Coronary Heart DiseaseDocument19 pagesA Review of The Affects of Worry and GAD Upon CV Health and Coronary Heart DiseaseDe DawnNo ratings yet

- Depression and Cardiovascular Disease: A Clinical ReviewDocument11 pagesDepression and Cardiovascular Disease: A Clinical ReviewmonicaNo ratings yet

- Effect of Stress, Depression and Type D Personality On Immune System in The Incidence of Coronary Artery DiseaseDocument12 pagesEffect of Stress, Depression and Type D Personality On Immune System in The Incidence of Coronary Artery DiseaseHéveny de Souza SilvaNo ratings yet

- Maturitas: SciencedirectDocument6 pagesMaturitas: SciencedirectDaniel QuirogaNo ratings yet

- 404 1609 1 PBDocument5 pages404 1609 1 PBRohamonangan TheresiaNo ratings yet

- New Research in Psychooncology: Current Opinion in Psychiatry April 2008Document6 pagesNew Research in Psychooncology: Current Opinion in Psychiatry April 2008JoseNo ratings yet

- New Research in Psychooncology: Current Opinion in Psychiatry April 2008Document6 pagesNew Research in Psychooncology: Current Opinion in Psychiatry April 2008José Carlos Sánchez-RamirezNo ratings yet

- JSL 047Document15 pagesJSL 047Alí Jorkaeff Hernández LópezNo ratings yet

- Panic Disorder: A Common Yet Underdiagnosed and Misunderstood Psychological Illness in PakistanDocument3 pagesPanic Disorder: A Common Yet Underdiagnosed and Misunderstood Psychological Illness in PakistanSharii AritonangNo ratings yet

- Post Stroke DepresiDocument9 pagesPost Stroke DepresiSitti Rosdiana YahyaNo ratings yet

- Poststroke Depression: A ReviewDocument9 pagesPoststroke Depression: A ReviewSnehaNo ratings yet

- Wu, Kling - Unknown - Depression and The Risk of Myocardial Infarction and Coronary Death A Meta-Analysis of Prospective Cohort Studies-AnnotatedDocument14 pagesWu, Kling - Unknown - Depression and The Risk of Myocardial Infarction and Coronary Death A Meta-Analysis of Prospective Cohort Studies-AnnotatedJúlia CostaNo ratings yet

- Sun Et Al. - 2020 - Depression and Myocardial Injury in ST-segment Elevation Myocardial Infarction A Cardiac Magnetic Resonance Imaging-AnnotatedDocument10 pagesSun Et Al. - 2020 - Depression and Myocardial Injury in ST-segment Elevation Myocardial Infarction A Cardiac Magnetic Resonance Imaging-AnnotatedJúlia CostaNo ratings yet

- Feng Et Al. - 2019 - Prevalence of Depression in Myocardial Infarction A PRISMA-compliant Meta-Analysis-AnnotatedDocument12 pagesFeng Et Al. - 2019 - Prevalence of Depression in Myocardial Infarction A PRISMA-compliant Meta-Analysis-AnnotatedJúlia CostaNo ratings yet

- Borderline Personality Disorder: Clinical Guidelines For TreatmentDocument22 pagesBorderline Personality Disorder: Clinical Guidelines For TreatmentJúlia CostaNo ratings yet

- LKJHHDocument5 pagesLKJHHVishnu SharmaNo ratings yet

- Feaces and Urine Test: Diarrhea That Lasts More Than A Few Days, Poop That Contains Blood or Mucus, StomachDocument3 pagesFeaces and Urine Test: Diarrhea That Lasts More Than A Few Days, Poop That Contains Blood or Mucus, StomachDhioPrimaNo ratings yet

- SchistosomiasisDocument3 pagesSchistosomiasisBeRnAlieNo ratings yet

- Meddra Important Medical Event Terms List Version 241 enDocument691 pagesMeddra Important Medical Event Terms List Version 241 enLuis Antonio Camacho CamachoNo ratings yet

- Register PasienDocument4,526 pagesRegister PasienSri nur HidayatiNo ratings yet

- Disease Detectives Cheat SheetDocument2 pagesDisease Detectives Cheat Sheetgolumnaa76% (58)

- Non Experimental DesignDocument52 pagesNon Experimental DesignAmal B Chandran100% (1)

- Notifiable Conditions FormDocument3 pagesNotifiable Conditions FormDarius DeeNo ratings yet

- UTI Guideline Example 2 Appendix B PDFDocument4 pagesUTI Guideline Example 2 Appendix B PDFamira catriNo ratings yet

- Frequency: Student Doctor Yazmine Lee, MD3 Washington University of Health and ScienceDocument38 pagesFrequency: Student Doctor Yazmine Lee, MD3 Washington University of Health and SciencePretty LeeNo ratings yet

- Salmonella: What Is Salmonella Infection (Salmonellosis) ?Document9 pagesSalmonella: What Is Salmonella Infection (Salmonellosis) ?Bijay Kumar MahatoNo ratings yet

- ApplicationForm AP3Document1 pageApplicationForm AP3Clash Of Clans Master100% (4)

- Cap MRDocument7 pagesCap MRZachary CohenNo ratings yet

- Introduction Buerger's DiseaseDocument2 pagesIntroduction Buerger's DiseaseJoseph Eric NardoNo ratings yet

- EPI Abhishek Gupta 08Document29 pagesEPI Abhishek Gupta 08Abhishek GuptaNo ratings yet

- Quarter 4 Worksheet 1: Sean Albert P. Valeza English - 10 Grade 10 - Liberality Science, Technology, Engineering (STE)Document2 pagesQuarter 4 Worksheet 1: Sean Albert P. Valeza English - 10 Grade 10 - Liberality Science, Technology, Engineering (STE)Albert ValezaNo ratings yet

- 37th Annual Research and Education Forum ProgramDocument36 pages37th Annual Research and Education Forum ProgramCharles SeguiNo ratings yet

- Pcol 2 PrelimsDocument6 pagesPcol 2 PrelimsMa. Andrea Julie AcasoNo ratings yet

- 02 Breast PDFDocument15 pages02 Breast PDFANAS ALINo ratings yet

- Pedia Prevous Board Questions PDFDocument103 pagesPedia Prevous Board Questions PDFJulius Matthew LuzanaNo ratings yet

- Dengue FNCPDocument1 pageDengue FNCPleo0% (1)

- Hidrosefalus Pada AnakDocument7 pagesHidrosefalus Pada AnakDintaNo ratings yet

- Mammaprint in IndonesiaDocument52 pagesMammaprint in IndonesiaYuliaji Narendra PutraNo ratings yet

- EMTCT FrameworkDocument68 pagesEMTCT Frameworkokwadha simionNo ratings yet

- Davao Doctors College Nursing Program Nursing Care PlanDocument7 pagesDavao Doctors College Nursing Program Nursing Care PlanSHININo ratings yet

- Dengue by KhushalDocument33 pagesDengue by Khushalikram ullah khanNo ratings yet

- Lesson Plan ON Seek Health Services For Routine Health Checkups, Immunization, Counseling, Diagnosis, Treatment, Follow UpDocument33 pagesLesson Plan ON Seek Health Services For Routine Health Checkups, Immunization, Counseling, Diagnosis, Treatment, Follow Uprevathidadam55555No ratings yet

- Icmr Specimen Referral Form For Covid-19 (Sars-Cov2) : (If Yes, Attach Prescription If No, Test Cannot Be Conducted)Document2 pagesIcmr Specimen Referral Form For Covid-19 (Sars-Cov2) : (If Yes, Attach Prescription If No, Test Cannot Be Conducted)DevNo ratings yet

- CrohnsDocument19 pagesCrohnsLauren LevyNo ratings yet

- Tuberculosis in Infancy and ChildhoodDocument55 pagesTuberculosis in Infancy and ChildhoodIna AguilarNo ratings yet

- Summary of The Body Keeps the Score: Brain, Mind, and Body in the Healing of Trauma by Bessel van der Kolk MDFrom EverandSummary of The Body Keeps the Score: Brain, Mind, and Body in the Healing of Trauma by Bessel van der Kolk MDRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (167)

- Summary: No Bad Parts: Healing Trauma and Restoring Wholeness with the Internal Family Systems Model by Richard C. Schwartz PhD & Alanis Morissette: Key Takeaways, Summary & AnalysisFrom EverandSummary: No Bad Parts: Healing Trauma and Restoring Wholeness with the Internal Family Systems Model by Richard C. Schwartz PhD & Alanis Morissette: Key Takeaways, Summary & AnalysisRating: 5 out of 5 stars5/5 (5)

- Rewire Your Anxious Brain: How to Use the Neuroscience of Fear to End Anxiety, Panic, and WorryFrom EverandRewire Your Anxious Brain: How to Use the Neuroscience of Fear to End Anxiety, Panic, and WorryRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (158)

- My Grandmother's Hands: Racialized Trauma and the Pathway to Mending Our Hearts and BodiesFrom EverandMy Grandmother's Hands: Racialized Trauma and the Pathway to Mending Our Hearts and BodiesRating: 5 out of 5 stars5/5 (70)

- The Upward Spiral: Using Neuroscience to Reverse the Course of Depression, One Small Change at a TimeFrom EverandThe Upward Spiral: Using Neuroscience to Reverse the Course of Depression, One Small Change at a TimeRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (141)

- Critical Thinking: How to Effectively Reason, Understand Irrationality, and Make Better DecisionsFrom EverandCritical Thinking: How to Effectively Reason, Understand Irrationality, and Make Better DecisionsRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (39)

- Summary: The Myth of Normal: Trauma, Illness, and Healing in a Toxic Culture By Gabor Maté MD & Daniel Maté: Key Takeaways, Summary & AnalysisFrom EverandSummary: The Myth of Normal: Trauma, Illness, and Healing in a Toxic Culture By Gabor Maté MD & Daniel Maté: Key Takeaways, Summary & AnalysisRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (9)

- Feel the Fear… and Do It Anyway: Dynamic Techniques for Turning Fear, Indecision, and Anger into Power, Action, and LoveFrom EverandFeel the Fear… and Do It Anyway: Dynamic Techniques for Turning Fear, Indecision, and Anger into Power, Action, and LoveRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (250)

- An Autobiography of Trauma: A Healing JourneyFrom EverandAn Autobiography of Trauma: A Healing JourneyRating: 5 out of 5 stars5/5 (2)

- The Worry Trick: How Your Brain Tricks You into Expecting the Worst and What You Can Do About ItFrom EverandThe Worry Trick: How Your Brain Tricks You into Expecting the Worst and What You Can Do About ItRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (107)

- Breaking the Chains of Transgenerational Trauma: My Journey from Surviving to ThrivingFrom EverandBreaking the Chains of Transgenerational Trauma: My Journey from Surviving to ThrivingRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (30)

- Redefining Anxiety: What It Is, What It Isn't, and How to Get Your Life BackFrom EverandRedefining Anxiety: What It Is, What It Isn't, and How to Get Your Life BackRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (153)

- The Autoimmune Cure: Healing the Trauma and Other Triggers That Have Turned Your Body Against YouFrom EverandThe Autoimmune Cure: Healing the Trauma and Other Triggers That Have Turned Your Body Against YouNo ratings yet

- Vagus Nerve: A Complete Self Help Guide to Stimulate and Activate Vagal Tone — A Self Healing Exercises to Reduce Chronic Illness, PTSD, Anxiety, Inflammation, Depression, Trauma, and AngerFrom EverandVagus Nerve: A Complete Self Help Guide to Stimulate and Activate Vagal Tone — A Self Healing Exercises to Reduce Chronic Illness, PTSD, Anxiety, Inflammation, Depression, Trauma, and AngerRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (16)

- Binaural Beats: Activation of pineal gland – Stress reduction – Meditation – Brainwave entrainment – Deep relaxationFrom EverandBinaural Beats: Activation of pineal gland – Stress reduction – Meditation – Brainwave entrainment – Deep relaxationRating: 5 out of 5 stars5/5 (9)

- The Complex PTSD Workbook: A Mind-Body Approach to Regaining Emotional Control & Becoming WholeFrom EverandThe Complex PTSD Workbook: A Mind-Body Approach to Regaining Emotional Control & Becoming WholeRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (49)

- Feeling Great: The Revolutionary New Treatment for Depression and AnxietyFrom EverandFeeling Great: The Revolutionary New Treatment for Depression and AnxietyNo ratings yet

- Don't Panic: Taking Control of Anxiety AttacksFrom EverandDon't Panic: Taking Control of Anxiety AttacksRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (12)

- Winning the War in Your Mind: Change Your Thinking, Change Your LifeFrom EverandWinning the War in Your Mind: Change Your Thinking, Change Your LifeRating: 5 out of 5 stars5/5 (561)

- Somatic Therapy Workbook: A Step-by-Step Guide to Experiencing Greater Mind-Body ConnectionFrom EverandSomatic Therapy Workbook: A Step-by-Step Guide to Experiencing Greater Mind-Body ConnectionNo ratings yet

- The Anatomy of Loneliness: How to Find Your Way Back to ConnectionFrom EverandThe Anatomy of Loneliness: How to Find Your Way Back to ConnectionRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (163)

- Overcoming Unwanted Intrusive Thoughts: A CBT-Based Guide to Getting Over Frightening, Obsessive, or Disturbing ThoughtsFrom EverandOvercoming Unwanted Intrusive Thoughts: A CBT-Based Guide to Getting Over Frightening, Obsessive, or Disturbing ThoughtsRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (48)

- Emotional Detox for Anxiety: 7 Steps to Release Anxiety and Energize JoyFrom EverandEmotional Detox for Anxiety: 7 Steps to Release Anxiety and Energize JoyRating: 5 out of 5 stars5/5 (6)

- Beyond Thoughts: An Exploration Of Who We Are Beyond Our MindsFrom EverandBeyond Thoughts: An Exploration Of Who We Are Beyond Our MindsRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (7)