Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Philo Module6 Week12 13 1

Philo Module6 Week12 13 1

Uploaded by

BEJERAS GrantOriginal Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Philo Module6 Week12 13 1

Philo Module6 Week12 13 1

Uploaded by

BEJERAS GrantCopyright:

Available Formats

Course Code: CORE8

Course Title: INTRODUCTION TO PHILOSOPHY OF THE HUMAN

PERSON

Course Type: CORE

Pre-requisite: NONE

Co-requisite: NONE

Quarter: 2nd

Course Topic: INTERSUBJECTIVITY

Module: #6 Week: 12-13

Course Subtopic: Meaning of Intersubjectivity

An Intersubjectivity Relationship Across Differences

Genuine Communication and Intersubjectivity

Course Description: An initiation to the activity and process of

Philosophical reflection as a search for synoptic

vision of life. Topics to be discussed include the

human experiences of embodiment, being in the

world with others and the environment, freedom,

intersubjectivity, sociality, being unto death.

Course Outcomes (COs) and Relationship to Student Outcomes

Course Outcomes SO

After completing the course, the student must a b c d

be able to:

4. Demonstrate an appreciation for the talents D I R

of persons with disabilities and those from

the underprivileged sectors of society.

* Level: I- Introduced, R- Reinforced, D- Demonstrated

INTERSUBJECTIVITY

MEANING OF INTERSUBJECTIVITY

Intersubjectivity, a term originally coined by the philosopher Edmund Husserl

(1859–1938) as cited by Cooper-White, Pamela (2014), is most simply stated as

the interchange of thoughts and feelings, both conscious and unconscious,

between two persons or “subjects,” as facilitated by empathy. To understand

intersubjectivity, it is necessary first to define the term subjectivity – i.e., the

perception or experience of reality from within one‟s own perspective (both

conscious and unconscious) and necessarily limited by the boundary or

horizon of one‟s own worldview. The term intersubjectivity has several usages

in the social sciences (such as cognitive agreement between individuals or

groups or, on the contrary, relating simultaneously to others out of two

diverging subjective perspectives, as in the acts of lying or presenting oneself

somewhat differently in different social situations); however, its deepest and

most complex usage is related to the postmodern philosophical concept of

constructivism

According to Baker, Kelly (2016), a good way to think about intersubjectivity is

to imagine how you relate to your family and friends. Maybe your mother

enjoyed playing tennis. She took you with her when she practiced, and you

always had a good time. Growing up, you decided to join the school tennis

team. If your mother had not played tennis with you growing up, you may not

Introduction to Philosophy of the Human Person

S.Y. 2020-2021 Page | 1

have grown to like the sport. Your experience with tennis can be called

intersubjective because it was influenced by another person (your mother). In

order to better understand intersubjectivity, we first need to define a subject

and an object. A subject is the person experiencing an action or event. An

object is what is being experienced. When we say something is objective, we

mean that it is factually true. When we say that something is subjective, we

mean that it is based on an opinion, or a biased viewpoint, not on hard facts.

In literature, subjectivity means that the story is told from a biased viewpoint,

whether it is told by a character or an unnamed narrator. Everyone in the

world has their own subjective viewpoint. Intersubjectivity means that we all

influence and are all influenced by others to some degree. The principle of

intersubjectivity can be applied to almost any decision we make, big or small.

We always have to consider how our actions will affect others. We ourselves are

constantly affected by the actions and words of the people around us.

AN INTERSUBJECTIVITY RELATIONSHIP ACROSS DIFFERENCES

By: PhiloTech (2018)

Jurgen Habermas’s Theory of Communicative Action

Mutual understanding is an important telos of any conversation be it a simple

dialogue or an argumentation. Thoughts are refined, relationship is deepened,

trust in others and confidence in oneself are built through communication.

When people converse bridges are constructed, strangers become friends, and

individuals turn into a society of people. Life-experiences, however, proves that

this is not always the case. In fact, it is common to see individuals with

different backgrounds such as way of thinking, believing, and behaving could

easily come into conflict when they communicate. To avoid arriving at that

point, Jurgen Habermas introduce a path leading to mutual understanding

through his theory of communication. He formulated four tests, or validity

claims on comprehensibility, truth, truthfulness, and rightness that must

occur in conversation to achieve mutual understanding.

1. Comprehensibility pertains to the use of ordinary language. If the

meaning of a word or statement is defined by the ordinary language in

which both speaker and hearer are familiar with then, for sure,

understanding will be achieved, especially, if the ordinary language is the

native language of both speaker and hearer.

2. Truth refers to how true the uttered statement in reference to objective

facts. If customer asks a waiter for a glass of water, the request will

surely be understood and it will be granted.

3. Truthfulness pertains to the genuine intention of the speaker which is

essential for the hearer‟s gaining trust. Sincerity in relationship is an

important aspect in achieving mutual understanding and it is assessed

by considering the congruence of the expressed meaning and the

speaker‟s agenda.

4. Rightness‟ pertains to the acceptable tone and pitch of voice and

expressions. Filipinos, generally, are intimidated, irritated, and even

threaten when someone talk with a high pitch or a loud voice as in a

shouting manner.

Introduction to Philosophy of the Human Person

S.Y. 2020-2021 Page | 2

Martin Buber’s I-Thou Relationship

The onset of industrialization and the growth of large urban cities, for Martin

Buber, has dehumanized the modern man by converting him from subjects

into objects through the instrumentality of the machine as “machines which

were invented in order to serve men in their work were no longer, like tools, an

extension of man‟s arm but man became that extension doing the bidding of

the machines”(See Curtis & Boultwood, 1975). The way man treats the

machine as an object becomes also his way of treating the other human

person. To radically break from these prevailing attitudes in order to establish

an ethical principle on human relationship anchored on the dignity of the

human person, Buber introduces his I-Thou philosophical theory.

1. The first mode, which Buber calls “experience” (the mode of „I–it‟), is

the mode that modern man almost exclusively uses. Through experience,

man collects data of the world, analyses, classifies, and theorizes about

them. This means that, in terms of experiencing, no real relationship

occurs for the “I” is acting more as an observer while its object, the “it” is

more of a receiver of the I‟s interpretation. The “it” is viewed as a thing to

be utilized, a thing to be known, or put for some purpose. Thus, there is

a distance between the experiencing “I” and the experienced “it” for the

former acts as the subject and the latter as a passive object, a mere

recipient of the act (Buber, 1958:4). Since there is no relationship that

occurs in experience, the “I” lacks authentic existence for it‟s not socially

growing or developing perhaps only gaining knowledge about the object.

So, for Buber, unless the “I” meets an other “I”, that is, an other subject

of experience, relationship is never established. Only when there is an I-I

encounter can there be an experience (Buber, 1958, pp. 5-7).

2. In the other mode of existence, which Buber calls “encounter” (the

mode of I–Thou), both the “I” and the „other‟ enter into a genuine

relationship as active participants. In this relationship, human beings do

not perceive each other as consisting of specific, isolated qualities, but

engage in a dialogue involving each other‟s whole being and, in which,

the „other‟ is transformed into a “Thou” or “You” (Buber, 1958, p. 8). This

treating the other as a “You” and not an “it” is, for Buber, made possible

by “Love” because in love, subjects do not perceive each other as objects

but subjects (Buber, 1958, pp. 15-16). Love, for Buber, should not be

understood as merely a mental or psychological state of the lovers but as

a genuine relation between the loving beings (Buber, 1958, p. 66). Hence,

for Buber, love is an I-Thou relation in which both subjects share a sense

of caring, respect, commitment, and responsibility. In this relationship,

therefore, all living beings meet each other as having a unity of being and

engage in a dialogue involving each other‟s whole being. It is a direct

interpersonal relation which is not mediated by any intervening system of

ideas, that is, no object of thoughts intervenes between “I” and

“Thou”(Buber, 1958, p. 26). Thus, the “Thou” is not a means to some

object or goal and the “I”, through its relation with the “Thou”, receives a

more complete authentic existence. The more that I-and-Thou share their

reality, the more complete is their reality.

Introduction to Philosophy of the Human Person

S.Y. 2020-2021 Page | 3

Emmanuel Levinas’ Face of the Other

Levinas grounds his ethics in a criticism of Western philosophical tradition

which subordinates the personal relation with concrete person who is an

existent to an impersonal relation with an abstract “Being” (Levinas,

1961/1979, p. 36). For instance, whenever we deal with someone, we use the

values and beliefs that we inherited from our society and used them as our

basis in relating with “others”. Certain times, we use them also as standard in

which we judge “other‟s” actions and character as good or bad. For Levinas,

these social values and beliefs are abstract “concept” that blurred our sight and

hinder us in seeing, accepting, and relating humanely with “others” for we give

more importance to those concepts than to “concrete person” who deserves

more our attention. In relating with others, we also apply our own “analytical

or judgemental categories” focusing more on what “I think” is good behaviour,

right living, correct thinking that the “other” must elicit for him/her to be

accepted (Levinas, 1961/1979, p. 46). This, however, for Levinas, is turning the

other‟s otherness into a “same” or like everyone else. This attitude also brings

back the other to oneself in a way that when one means to speak of the other,

one is actually only “speaks of oneself”, that is, of his own image (Levinas,

1991, pp110-111). It is in this case, that the other‟s “otherness” is radically

negated. To this kind of ontological approach, Levinas wishes to substitute a

non-allergic relation with alterity, that is, one that caters for the “other‟s

infinite otherness” (Levinas, 1961/1979, p. 38). What Levinas suggests is for us

to adopt a genuine face-to-face encounter with the “Other”. He believes that it

is only in responding to the command of the face of the „Other‟ that an

authentic ethics could be made. He even claimed that the meaning of ethics is

in responding to the needs of the “Other”, to be subjected to the “Other”, and to

be responsible to the “Other” without expecting anything in return (Levinas,

1982, pp. 98-99).

GENUINE COMMUNICATION AND INTERSUBJECTIVITY

By: Balchan, Michael (2016)

“Words are, in my not-so-humble opinion, our most inexhaustible source of

magic. Capable of both inflicting injury, and remedying it.” – Albus

Dumbledore, J.K. Rowling

The Magic of Genuine Communication

Communicating honestly, genuinely, and authentically is powerful. Opening

ourselves up might be scary, but it also opens the door to creating true

connections to those around us, and leading happier, fuller lives. Honest and

effective communication can help us to:

Explore who we are. Trying to describe in words what we‟re thinking or

feeling can help us get a better understanding of those things ourselves.

Create more intimate, relationships. Relationships are about authentic

connection, about two people sharing their true selves with one another.

This requires being willing to say what we‟re really thinking and feeling.

As Kristen often reminds me, she‟s “not a mind reader!”

Introduction to Philosophy of the Human Person

S.Y. 2020-2021 Page | 4

Become better leaders. Gail Kelly, one of the most powerful women in

the world 1), shares, “This digital age requires leaders to be visible and

authentic and to be able to communicate the decisions they‟ve made and

why they‟ve made them.”

Get what we want. When we let others know exactly what we‟re looking

for, it makes it easier for them to help us get it. It also creates a clear

vision to work towards.

Have more success. In the words of self-development pioneer Paul J.

Meyer, “Communication – the human connection – is the key to personal

and career success.”

Practicing Genuine Communication

With a little practice, we can all become better communicators.

“Communication is a skill that you can learn,” explains Brian Tracy. “It‟s like

riding a bicycle or typing. If you‟re willing to work at it, you can rapidly improve

the quality of every part of your life.” Rather than jumping right into potentially

uncomfortable or difficult conversations, try starting in situations where the

stakes are lower. For example:

Communicate more honestly with yourself by writing in a journal.

Whether once a day, once a week, or once a month – create space for

reflection and let the words flow out unrestricted.

Talk to a tree, or to a pet (like a dog). Sometimes all we need is

someone or something to listen to us, even if they can‟t understand – or

talk back.

Write a letter to someone you care about. It can be a gratitude letter,

or just a note sharing something that you haven‟t felt comfortable

sharing before. You don‟t even have to send it.

Practice listening. Everyone communicates differently according to their

own background, beliefs, and situation. Pay attention to how the people

around you are interacting, both in their body language, eye-contact, and

the things they say – or don‟t say. “To effectively communicate,”

according to Tony Robbins, “we must realize that we are all different in

the way we perceive the world, and use this understanding as a guide to

our communication with others.”

Introduction to Philosophy of the Human Person

S.Y. 2020-2021 Page | 5

HOMEWORK 3:

Song Analysis: Love Me for Who I Am

Instructions: Listen to the song “ Love Me for Who I Am” by The

Carpenters. Then answer the questions that follow.

Name: _____________________________ Grade &Section: ________________

LOVE ME FOR WHAT I AM

By: The Carpenters

We fell in love We either take each other

On the first night that we met For everything we are

Together we've been happy Or leave the life we've made

I have very few regrets behind

The ordinary problems And make another start

Have not been hard to face

But lately little changes You've got to love me for

Have been slowly taking place what I am

For simply being me

You're always finding Don't love me if what you

something intend

Is wrong in what I do Or hope that I will be

But you can't rearrange my life And if you're only using me

Because it pleases you To feed your fantasy

You're really not in love

You've got to love me for what I So let me go, I must be free

am

For simply being me And if you're only using me

Don't love me for what you To feed your fantasy

intend You're really not in love

Or hope that I will be So let me go, I must be free

And if you're only using me

To feed your fantasy You're really not in love

You're really not in love So let me go, I must be free

So let me go, I must be free

If what you want

Isn't natural for me

I won't pretend to keep you

What I am I have to be

The picture of perfection

Is only in your mind

For all your expectations

Love can never be designed

Is there a connection between the song and our topic Intersubjectivity?

and How?

___________________________________________________________________

___________________________________________________________________

___________________________________________________________________

___________________________________________________________________

___________________________________________________________________

___________________________________________________________________

Introduction to Philosophy of the Human Person

S.Y. 2020-2021 Page | 6

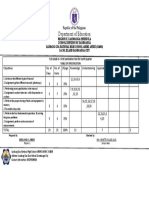

SELF-ASSESMENT

Encircle

your

Answer

FORM

Read each statement and check ( ) the box that reflects your work today.

Name: Date:

Section:

Strongly

Disagree Agree

Agree

1. I found this work interesting.

2. I make a strong effort.

3. I am proud of the results.

4. I understood all the instructions.

5. I followed all the steps.

6. I learned something new.

7. I feel ready for the next assignment.

www.ldatschool.ca/executive-function/self-assessment/

Introduction to Philosophy of the Human Person

S.Y. 2020-2021 Page | 7

Reference Book:

Introduction to the Philosophy of the Human Person

Brenda Corpuz, Diwa Learning System Inc. 2016,

Jose Romero Joven & Ramonito Canete Perez, Books Atbp.

Publishing Corporation

Brenda B. Corpuz, BSE, MAEd, Phd et.al. OBE Publishing

Online Reference:

Cooper-White, Pamela (2014), Intersubjectivity | SpringerLink

Retrieved from: link.springer.com › 978-1-4614-6086-2_9182

Baker, Kelly (2016), Intersubjectivity: Definition & Examples - Video &

Lesson ...

Retrieved from: study.com › academy › lesson › intersubjectivity-definition-

examples

PhiloTech (2018), Intersubjectivity: Introduction to the Philosophy of

the Human Person

Retrieved from: https://philotech119334246.wordpress.com/2018/10/

12/intersubjectivity/

Balchan, Michael (2016), The Magic of Genuine Communication

Retrieved from: michaelbalchan.com › communication

Introduction to Philosophy of the Human Person

S.Y. 2020-2021 Page | 8

You might also like

- The Autobiography MILES DAVIS With Quincy TroupeDocument219 pagesThe Autobiography MILES DAVIS With Quincy TroupevzeNo ratings yet

- Lesson 7 The Human Person in Society IntersubjectivityDocument19 pagesLesson 7 The Human Person in Society IntersubjectivityPrice Junior100% (1)

- The Human Person and Intersubjective Human RelationDocument17 pagesThe Human Person and Intersubjective Human RelationAndrea Gienel MontallanaNo ratings yet

- Intersubjectivity HandoutDocument5 pagesIntersubjectivity HandoutBatchie BermudaNo ratings yet

- Lesson 13 - Intersubjectivity - (Part 1) - Hand OutsDocument25 pagesLesson 13 - Intersubjectivity - (Part 1) - Hand OutsMARICEL SONGAHIDNo ratings yet

- Branch Office Desk Assembly GuideDocument10 pagesBranch Office Desk Assembly GuideiambrennanhicksonNo ratings yet

- IntersubjectivityDocument52 pagesIntersubjectivityOrly G. UmaliNo ratings yet

- Intersubjectivity LessonDocument58 pagesIntersubjectivity LessonClarence Imperial100% (1)

- The Self and Others..Document33 pagesThe Self and Others..Bj TorculasNo ratings yet

- Final Action ResearchDocument11 pagesFinal Action ResearchKARENNo ratings yet

- IntersubjectivityDocument40 pagesIntersubjectivityAlisa Bosconovitch100% (5)

- Introduction To The Philosophy of The Human Person: Quarter 2 - Week 3Document5 pagesIntroduction To The Philosophy of The Human Person: Quarter 2 - Week 3bey lu0% (1)

- LAS Intro-to-Philo Grade-12 Week-3 4Document7 pagesLAS Intro-to-Philo Grade-12 Week-3 4PatzAlzateParaguyaNo ratings yet

- Module 6Document4 pagesModule 6ganda dyosaNo ratings yet

- Intersubjectivity 1Document4 pagesIntersubjectivity 1School Desk SpaceNo ratings yet

- Intersubjectivity Day 1 Students Copy With MDL ActivityDocument28 pagesIntersubjectivity Day 1 Students Copy With MDL Activityinayra22No ratings yet

- Intersubjectivity: Martin BuberDocument2 pagesIntersubjectivity: Martin BuberJessica DelremedioNo ratings yet

- Hand Out - Module-3-Intersubjectivity-Wk-3-Final-P.10Document8 pagesHand Out - Module-3-Intersubjectivity-Wk-3-Final-P.10LilowsNo ratings yet

- Introduction To The Philosophy Q2 W2Document5 pagesIntroduction To The Philosophy Q2 W2Raia Marie Jillian OximasNo ratings yet

- Lesson 12: Freedom of The Human Person Time Frame: Week 14Document3 pagesLesson 12: Freedom of The Human Person Time Frame: Week 14Jondave Sios-eNo ratings yet

- INTERSUBJECTIVITY As OntologyDocument3 pagesINTERSUBJECTIVITY As OntologyZoey HeishNo ratings yet

- IPHP LAS Q4 Wk3.v4Document10 pagesIPHP LAS Q4 Wk3.v4Jennette BelliotNo ratings yet

- LESSON 2. 1 and 2 Philo of IntersubjectivityDocument7 pagesLESSON 2. 1 and 2 Philo of IntersubjectivityJayvie AljasNo ratings yet

- Students IntersubjectivityDocument22 pagesStudents IntersubjectivityDominic CorreaNo ratings yet

- IntersubjectivityDocument51 pagesIntersubjectivitySaVaGe KittyNo ratings yet

- Scp-Topics: 2 Quarter: IntersubjectivityDocument4 pagesScp-Topics: 2 Quarter: IntersubjectivityMode John CuranNo ratings yet

- Philosophy NotesDocument5 pagesPhilosophy NotesApril CarreonNo ratings yet

- Lesson 13 Intersubjectivity Part 1Document25 pagesLesson 13 Intersubjectivity Part 1billondomaejeanNo ratings yet

- Inter SubjectivityDocument10 pagesInter SubjectivityJomarie BualNo ratings yet

- 2 2-IntersubjectivityDocument29 pages2 2-Intersubjectivitylarashynefernandez7No ratings yet

- Intersubjectivity of Human Relations in Accepting DifferencesDocument61 pagesIntersubjectivity of Human Relations in Accepting DifferencesBon Lister FactorinNo ratings yet

- SHS2QN#3 (Philo11)Document3 pagesSHS2QN#3 (Philo11)paulinabeatrix10No ratings yet

- Lesson 13 - Intersubjectivity - (Part 1) - Hand OutsDocument25 pagesLesson 13 - Intersubjectivity - (Part 1) - Hand OutsAlfredo QuijanoNo ratings yet

- Lesson 2 IntersubjectivityDocument6 pagesLesson 2 IntersubjectivityveneeshakeithNo ratings yet

- Buber Levinas and The I Thou RelationDocument24 pagesBuber Levinas and The I Thou Relationorlando garciaNo ratings yet

- 3 The Phenomenology of Intersubjective RelationshipDocument2 pages3 The Phenomenology of Intersubjective RelationshipLynnil Ann CaniculaNo ratings yet

- Local Media7206356050706637850Document99 pagesLocal Media7206356050706637850Ry WannaFlyNo ratings yet

- Module 2Document5 pagesModule 2Loie LyndonNo ratings yet

- Philo Q2 Inter-Subjectivity-1Document24 pagesPhilo Q2 Inter-Subjectivity-1Sherrylein SagunNo ratings yet

- Lesson 3 IntersubjectivityDocument4 pagesLesson 3 Intersubjectivityruth san joseNo ratings yet

- Introduction To The Philosophy - Q2 - W2Document8 pagesIntroduction To The Philosophy - Q2 - W2JessaLorenTamboTampoyaNo ratings yet

- Q3 M6 PhilosophyDocument4 pagesQ3 M6 PhilosophyDonna Lyn Domdom PadriqueNo ratings yet

- Philo Q2 M3 Lessons ActivityDocument8 pagesPhilo Q2 M3 Lessons ActivityKrystal ReyesNo ratings yet

- Lesson 13 - Intersubjectivity - (Part 1) - Hand OutsDocument25 pagesLesson 13 - Intersubjectivity - (Part 1) - Hand OutsMARY JOSEPH OCONo ratings yet

- INTERSUBJECTIVITYDocument1 pageINTERSUBJECTIVITY523001727No ratings yet

- Chapter 6: Intersubjectivity: The Philosophical Concept of IntersubjectivityDocument5 pagesChapter 6: Intersubjectivity: The Philosophical Concept of IntersubjectivityLuna TremeniseNo ratings yet

- Philo Q2 Inter-Subjectivity (1) - 1Document30 pagesPhilo Q2 Inter-Subjectivity (1) - 1Sherrylein SagunNo ratings yet

- Intersubjectivity - Intro To PhiloDocument15 pagesIntersubjectivity - Intro To PhiloMARY JOSEPH OCONo ratings yet

- Group-3Document37 pagesGroup-3Marilyn RonquilloNo ratings yet

- IPHP LAS Q3 Week 6Document4 pagesIPHP LAS Q3 Week 6Russell CasupananNo ratings yet

- Exploring The Intricacies of Intersubjectivity in Philosophy A Formal AnalysisDocument11 pagesExploring The Intricacies of Intersubjectivity in Philosophy A Formal AnalysisGeron BigayNo ratings yet

- Disciplines and Ideas in Social Sciences: Dissq1W7Document11 pagesDisciplines and Ideas in Social Sciences: Dissq1W7FrennyNo ratings yet

- Phil-2130 Final Exam, 2023SDocument5 pagesPhil-2130 Final Exam, 2023Sahmedahmed976666No ratings yet

- Intersubjectivity: Objective Subjective Object Subject Subject Subjective ObjectiveDocument1 pageIntersubjectivity: Objective Subjective Object Subject Subject Subjective ObjectiveHannah Beatriz QuiambaoNo ratings yet

- HVXDFHHCCFGJHJDocument8 pagesHVXDFHHCCFGJHJmileslicarte3No ratings yet

- Chapter 5 The Human Person As An Intersubjective BeingDocument5 pagesChapter 5 The Human Person As An Intersubjective BeingMARIE ERICKA ARONANo ratings yet

- Exploring The Intricacies of Intersubjectivity in Philosophy A Formal AnalysisDocument11 pagesExploring The Intricacies of Intersubjectivity in Philosophy A Formal AnalysisGeron BigayNo ratings yet

- 6 Kingfisher and Skylark ST., Zabarte Subd., Brgy. Kaligayahan, Novaliches, Quezon CityDocument4 pages6 Kingfisher and Skylark ST., Zabarte Subd., Brgy. Kaligayahan, Novaliches, Quezon CityImyourbitchNo ratings yet

- Day 1 MDL Intersubjectivity Authentic Dialogue An Element of Interpersonal RelationshipDocument35 pagesDay 1 MDL Intersubjectivity Authentic Dialogue An Element of Interpersonal Relationshipalecxisalbano16No ratings yet

- Hermeneutics-Phenomenology and Symbolic InteractionismDocument35 pagesHermeneutics-Phenomenology and Symbolic InteractionismJulliane Lucille GrandeNo ratings yet

- Intersubjectivity: Lesson 6Document76 pagesIntersubjectivity: Lesson 6Precious Leigh VillamayorNo ratings yet

- Passion Before Prudence: Commitment Is the Mother of MeaningFrom EverandPassion Before Prudence: Commitment Is the Mother of MeaningNo ratings yet

- First of AllDocument3 pagesFirst of AllBEJERAS GrantNo ratings yet

- Raw DataDocument9 pagesRaw DataBEJERAS GrantNo ratings yet

- Philo Module8 Week16 17Document9 pagesPhilo Module8 Week16 17BEJERAS GrantNo ratings yet

- Philo Module2 Week3 4 1Document15 pagesPhilo Module2 Week3 4 1BEJERAS GrantNo ratings yet

- By: Lumen Learning: Introduction To Philosophy of The Human PersonDocument7 pagesBy: Lumen Learning: Introduction To Philosophy of The Human PersonBEJERAS GrantNo ratings yet

- By: Naft., Joseph (2014) : Introduction To Philosophy of The Human PersonDocument9 pagesBy: Naft., Joseph (2014) : Introduction To Philosophy of The Human PersonBEJERAS GrantNo ratings yet

- Philo Module1 Week2 1Document14 pagesPhilo Module1 Week2 1BEJERAS GrantNo ratings yet

- Philo Module4 Week7 8 1Document10 pagesPhilo Module4 Week7 8 1BEJERAS GrantNo ratings yet

- Philo Module5 Week10 11 1Document13 pagesPhilo Module5 Week10 11 1BEJERAS GrantNo ratings yet

- Science Technology and Society MidtermsDocument16 pagesScience Technology and Society MidtermsDARYL JAMES MISANo ratings yet

- Tos Tle 1ST Sum - Test 4TH QuaterDocument1 pageTos Tle 1ST Sum - Test 4TH QuaterFatima AdilNo ratings yet

- Vocabulary ClothesDocument2 pagesVocabulary ClothesKeeo100% (2)

- Moraga, Cherrie La GueraDocument5 pagesMoraga, Cherrie La GueranizaiaNo ratings yet

- Keynote SpeechDocument9 pagesKeynote SpeechBLP CooperativeNo ratings yet

- Chapter-7 Lovewell KPPDocument21 pagesChapter-7 Lovewell KPPAbid HossainNo ratings yet

- British Politics and European ElectionsDocument245 pagesBritish Politics and European ElectionsRaouia ZouariNo ratings yet

- 2022 Obc GuidelinesDocument3 pages2022 Obc Guidelinesbelle pragadosNo ratings yet

- Dr. X and The Quest For Food Safety Video Review Teacher KeyDocument8 pagesDr. X and The Quest For Food Safety Video Review Teacher KeyemNo ratings yet

- The Earth in The Solar System: Globe: Latitudes and LongitudesDocument10 pagesThe Earth in The Solar System: Globe: Latitudes and LongitudesPranit PrasoonNo ratings yet

- Industrial Cutters: Elaborate Concept Enhancing Your ProductivityDocument11 pagesIndustrial Cutters: Elaborate Concept Enhancing Your ProductivityMoreno markovicNo ratings yet

- Small Area Atlas Bangladesh: Narsingdi ZilaDocument54 pagesSmall Area Atlas Bangladesh: Narsingdi ZilaRakib HasanNo ratings yet

- Unit 34 Digital Marketing - LO2Document14 pagesUnit 34 Digital Marketing - LO2Nabeel hassanNo ratings yet

- SWOT Analysis of Coca Cola: StrengthsDocument6 pagesSWOT Analysis of Coca Cola: StrengthsFaisal LukyNo ratings yet

- Happy Teacher DayDocument1 pageHappy Teacher DayPrincess Joy Andayan BorangNo ratings yet

- 4 KEE101T 201T Basic Electrical EnggDocument158 pages4 KEE101T 201T Basic Electrical EnggFinnyNo ratings yet

- Vocabulary + Grammar Unit 3 Test ADocument2 pagesVocabulary + Grammar Unit 3 Test AMercurioTimeNo ratings yet

- Qulalys Sample ReportDocument6 pagesQulalys Sample Reporteagleboy007No ratings yet

- John Talbot ShakespearDocument3 pagesJohn Talbot ShakespearPartha Pratim BiswasNo ratings yet

- MSD Unit 3 PPT-R1Document46 pagesMSD Unit 3 PPT-R1Vikas RathodNo ratings yet

- Encumbrance Form KDDocument3 pagesEncumbrance Form KDEntertainment world teluguNo ratings yet

- Nonrenewable Energy ResourcesDocument54 pagesNonrenewable Energy ResourcesEUNAH LimNo ratings yet

- Child Centred EducationDocument2 pagesChild Centred EducationHarshita VarshneyNo ratings yet

- Degree: Bachelor of Science MathematicsDocument22 pagesDegree: Bachelor of Science Mathematicssteven7 IsaacsNo ratings yet

- Obj Day 1 Science DLLDocument5 pagesObj Day 1 Science DLLRoss AnaNo ratings yet

- Rules For Writing Out DollarsDocument7 pagesRules For Writing Out DollarsDũng Đào TrungNo ratings yet

- Lemon TreeDocument2 pagesLemon TreeMarjorie ConradeNo ratings yet