Professional Documents

Culture Documents

This Content Downloaded From 200.144.238.1 On Thu, 17 Jun 2021 12:14:24 UTC

Uploaded by

Alessandra ZanchettaOriginal Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

This Content Downloaded From 200.144.238.1 On Thu, 17 Jun 2021 12:14:24 UTC

Uploaded by

Alessandra ZanchettaCopyright:

Available Formats

Age, Sex, and Vocal Task as Factors in Singing "In Tune" during the First Years of

Schooling

Author(s): Graham F. Welch, Desmond C. Sergeant and Peta J. White

Source: Bulletin of the Council for Research in Music Education , Summer, 1997, No.

133, The 16th International Society for Music Education: ISME Research Seminar

(Summer, 1997), pp. 153-160

Published by: University of Illinois Press on behalf of the Council for Research in

Music Education

Stable URL: https://www.jstor.org/stable/40318855

JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide

range of content in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and

facilitate new forms of scholarship. For more information about JSTOR, please contact support@jstor.org.

Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of the Terms & Conditions of Use, available at

https://about.jstor.org/terms

University of Illinois Press and are collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve and extend

access to Bulletin of the Council for Research in Music Education

This content downloaded from

200.144.238.1 on Thu, 17 Jun 2021 12:14:24 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

Bulletin for the Council for Research in Music Education Summer, 1997, No. 133

Age, Sex, and Vocal Task as Factors in Singing "In

Tune9' During the First Years of Schooling

Graham F. Welch, Desmond C. Sergeant, and Peta J. White

Centre for Advanced Studies in Music Education

Roehampton Institute London, London, England

Abstract

An ability to sing "in tune " has often been regarded (whether appropriately or not) as a

characteristic indicator of general musical ability. As such, this particular musical behavior has long

been of interest to music educators and researchers. Previous research studies have reported

significant differences between children in relation to the age and sex of sample populations. In

general, (a) the relative proportion of "in-tune " singers has been found to increase as a function of

age and (b) fewer boys than girls are reported as being able to sing "in tune" for each sampled age

group. The established research literature, however, is characterised by an absence of longitudinal

data. Such data could enable a comparison to be made of how the singing abilities of the same sample

develop and/or remain stable over time.

Accordingly, as part of a larger study of singing development in early childhood, a longitudinal

sample (N=184) were assessed on a variety of vocal pitch matching tasks during each year of their

first 3 years in school (i.e., at age 5, 6, and 7 years. The assessment protocol embraced a specially

constructed test battery of pitch glides, pitch patterns, and single pitches as well as two sample songs,

with vocal pitch accuracy being assessed by a team of judges. The results suggest that (a) vocal pitch

accuracy is task-specific, (b) there is a greater homogeneity in vocal pitch matching abilities between

girls and boys than previously reported and (c) it is only at the age of 7 years that the previously

reported sex difference in favor of girls emerges, and this is only in relation to the sample song

material, not in relation to other more elemental forms of vocal pitch matching.

aSh! He's drunk and singing- a most unpleasant racket.

How clumsy and out of tune!

Hell be sorry for it .... let's teach the untutored oaf how to sing."

(Eurypides, Cyclops)

Introduction

For more than 50 years, "out-of-tune" singing (sometime labelled "grunt-

ing," "growling," "monotoning," "uncertain," and "poor pitch singing") has been

a recurring feature within the music education research literature. This form of

perceived musical "disability" is believed to characterize the musical behaviors

of significant numbers within the population, both child and adult, across all

Western-style societies2 . However, although omnipresent, this "disability" is

known to be variable3 . For example, the proportion of children who sing "out of

tune" (irrespective of definition) is unevenly distributed across the primary

(elementary) and secondary years of schooling. A summary comparison (Welch,

1994a) of sample children aged 7 and 11 years reveals a general consensus

within the research literature that approximately 35% of 7-year-olds in Western

cultures sing out of tune compared with a much smaller percentage of approxi-

mately 7% for sample 11 -year-old populations (with a caveat mat this latter

153

This content downloaded from

200.144.238.1 on Thu, 17 Jun 2021 12:14:24 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

154

proportion does not distin

onset of puberty and con

Closer examination of th

literature reveals clear se

consistently being rated

ger, 1994; Welch & Mur

(Ellis, 1993), England (H

continued to support the

sus that the proportion of

age group4.

Almost without exception, however, the available research literature is

based on "snap-shot" studies that have examined particular sample populations

at one given moment in time. Apart from a few adolescent voice studies5,

virtually no longitudinal evidence is available to provide a clear empirical per-

spective on how singing behaviors develop, persist and/or transform over time.

Furthermore, despite a wealth of research literature6 on the efficacy of different

pedagogical approaches to the remediation of out-of-tune singing, our under-

standing of the exact nature and variety of in-tune singing behaviors continues to

require definition, particularly if one adopts a model in which sociocultural

context, musical genre, and musical task are critical to definitions of singing

development and of singing in tune.

Experimental Sample

An initial 3!/2-year study of singing development in early childhood7 fo-

cused on mapping the singing development of groups of children aged 4 to 8

years, taking account of the social and ethnic populations from which they were

drawn, and comparing these to other sample populations aged 3 to 12 years. A

major aspect of the research was a longitudinal study of children during the first

phase of compulsory schooling, embracing Key Stage 1 of the English National

Curriculum for Music (age 5 to 7 years). The longitudinal sample (N= 184; boys

= 87, girls = 97) were drawn from ten Primary schools in the Greater London

area, chosen so as to provide a mixture of social class, ethnicity and urban/subur-

ban locations.

Method

The research protocol was designed to examine the different kinds of sing-

ing competency that are evinced by a range of singing tasks. A review of the

previous research literature had revealed a variety of singing assessment proce-

dures clustered into two main types, specially chosen song material (e.g., rounds,

folk songs, nursery rhymes, national anthems - see Anderson, 1937; Joyner,

1969; Plumridge, 1972; Buckton, 1982; Welch, 1986; Wurgler, 1990; Ellis,

1993) and individual pitches and patterns of pitches/melodic fragments (e.g.,

pitches presented either singly, in pairs, or as a series - see Madsen et al., 1969;

Greer et al., 1973; Yank Porter, 1977; Welch, 1985; Welch et al., 1989). The

testing protocol embraced these two broad categories, with glissandi added (as

schematic pitch contours), ensuring that all the "individual pitches and melodic

fragments/patterns" items were also embedded within the pitch typography of

This content downloaded from

200.144.238.1 on Thu, 17 Jun 2021 12:14:24 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

Welch, Sergeant, and White

pairs of specially const

pattern of a3-f4-d4 wa

The stimuli for singing

to assess the subject's ab

patterns [melodic fragm

two songs. To reduce t

random or testing varia

pitches) were recorded o

to control for direction

grade). The sound source

chorister and electroni

modelled on audio tape b

two weeks prior to testin

Each subject learned a

that their pitches were w

age groups (a3-220Hz t

matter deemed to be sui

words, and comprised s

taught to the children b

in the schools, keeping t

the number of teachi

consistent with practi

"authentic" experience f

exposure to the songs. I

the research team revis

mally on earlier visits)

area away from the clas

data collection situatio

session either singly or,

No starting pitch was pr

and each singer spontan

vocal responses were re

tioned 15-20cm below th

For an evaluation of the

the purely sung acoustic

sis), edited versions of

experienced professiona

against previously agree

Results

Judges' ratings of subjects' vocal pitch accuracy revealed that, in general,

the female and male subjects were consistently close in all three years (see Table

1 and Figure 1), with the greatest differences being attributed to the nature of the

task and the year of testing11. The other findings in relation to the sex of the

subjects were as follows: in years 1 and 2, there were no statistically significant

sex differences in ratings for vocal pitch accuracy, although girls generally had

greater mean ratings for song performance, whereas boys had greater means for

responses to test items (with one exception, single pitches in year 3). However,

This content downloaded from

200.144.238.1 on Thu, 17 Jun 2021 12:14:24 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

156

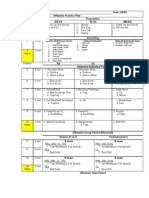

Table 1

Multivariate Analysis of Variance to Test for Interaction Effects Between Year of Test

and Mean Rating Levels of Vocal Pitch Accuracy for Test Battery (Fragments, Single

Pitches, Glides) and Songs Across Sexes (?V= 184; boys = 87, girls = 97)

Source of variance F value p

Sex 0.02 0.893

Test-type 261.96 <0.001

Test-year 31.67 <0.001

Sex by test-type 3. 1 89 0.760

Sex by test-year 0.89 0.389

Test-type by test-year 1 1 .32 O.001

Sex by test-type by test-year 0.92 0.454

Table 2

Differences Between Mean Ratings for Vocal Pitch Accuracy

by Sex for Test Battery Items and Songs (t tests)

Year I Year 2 Year 3

Test item p Sex* p Sex* p Sex*

Test battery and songs together .230 boys .729 boys .904 boys

Songs (x2) .394 girls .249 girls .016 girls

Test battery: .342 boys .708 boys .782 boys

Fragments

Simple glides (i.e., uni- or bi-directional) .237 boys .038 boys .315 boys

Complex glides (multidirectional) .512 boys .597 boys .440 boys

Single pitches '.887 boys .325 boys .684 girls

♦indicates the group (male/female) with the larger mean rating

significant differences are indicated in bold

sex differences emerged in the data between the songs and the batt

in (a) year 2, with boys being rated significantly better in pitchin

(p=.038; but a non-significant difference in other years) and (b)

girls achieving significantly higher ratings for their vocal pitch acc

singing (p=.0\6; see Table 2). Closer inspection of this sex diff

singing in year 3 revealed that the mean ratings for the sample boy

linearly across all 3 years, whereas the means for the girls had r

tively constant (see Table 2 and Figure 1).

Discussion

The reasons underlying the decline in the boys' mean ratings for vocal pitch

accuracy in the song singing condition relative to girls across the 3 years are

unclear. Boys' general vocal pitch accuracy for all test items across the 3 years

was very similar to that of the girls, with both sexes showing a steady improve-

This content downloaded from

200.144.238.1 on Thu, 17 Jun 2021 12:14:24 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

Welch, Sergeant, and White

Figure 1 . Ratings for songs an

ment in each year of testin

girls (see Figure 1). It is on

artifact (i.e., in the singing

each year and (b) declined

years). It may be that th

associated with the sex of

female) who were the prim

and that boys' increasing

negative by-product of the

subject taught by female t

song singing combines lang

competency development

development. For example,

these sex differences in so

aspect of linguistic develop

reading competency bein

(Sammons, 1995).

Nevertheless, irrespective

female subjects in song sing

is of the homogeneity of

This content downloaded from

200.144.238.1 on Thu, 17 Jun 2021 12:14:24 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

158

vocal pitch tasks. There

study of children's singi

age 5 with broadly simila

maintained across the f

singing. However, this p

statistically significant,

observed in the data. Of

nature of the task and

research literature of a

singers is not generally su

singing. On the contrary

between the sexes than h

It may be that there is

girls' rather than boys

artifacts. The lack of dif

matching tasks (as exam

that any such difference

to be cultural in origin ra

Notes

barker, A. (1984) p. 83.

2For the purposes of this introduction, a "deficit" model of singing "disabil-

ity" (i.e., singing "out-of-tune") is being used as this is the model that most

characterizes the majority of studies within the research literature. In this cus-

tomary "deficit" model, the focus is on a lack of ability, on what certain children

and adults appear to be unable to accomplish with their singing voices when

compared with others who are "normal" in that they are able to sing "in-tune."

An alternative perspective is one that views, singing competency as a multifac-

eted developmental process in which variation is normal, being socially and

culturally located in relation to specific musical tasks, with vocal skill acquisition

subject to development over time in relation to appropriate experience (see

Welch, 1994b).

3For a recent comprehensive review of the research literature on "out-of-

tune" singing, see Welch and Murao (1994).

4A caveat is that the research literature on "out-of-tune" singing is firmly

located in Western musical aesthetics and genres. Singing development and

abilities in relation to non-Western musics may be different because of differing

musical traditions and structures. Although singing is a commonplace human

activity, it is also culturally diverse and so definitions of "out-of-tune" singing

may be equally culturally variable.5

5Naidr et al, 1965; Frank & Sparber, 1970; Rutkowski, 1984; Huff-Gackle,

1991; Cooksey, 1993.

6See, for example, Rupp, 1992; Phillips, 1992; Young, 1993; Moore, 1994;

Welch, 1994a; Rossiter, 1995.

7The project, Singing Development in Early Childhood, was originally

funded by the Leverhulme Trust (1990-1994) under research grant F569A, and

subsequently as part of an award (R2014) from the Roehampton Institute London

Research Committee (1994-1997).

This content downloaded from

200.144.238.1 on Thu, 17 Jun 2021 12:14:24 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

Welch, Sergeant, and White

8Two versions of the tapes were prepared to test for directional reversals

(i.e., ascending/descending, prime/retrograde). Two further versions of the tapes

were prepared to take account of ordering effects during years 2 and 3 of the

longitudinal study.

9In the first year of testing, all the five-year-old subjects learned the same

two songs. In the second and third years, teachers were given a choice of a wider

selection of alternative pairs of songs, including the original two.

10Welch(1979).

1 lrThe main findings of the longitudinal study in relation to the test items and

year of testing are discussed elsewhere (see Welch, Sergeant, & White, Singing

Development in Early Childhood: A Longitudinal Study [forthcoming]).

12The gender effects and bias within school music (with the exception of

music technology) as a predominantly "feminine" subject area may be found in

several research studies (for example: Finnegan, 1989; Archer & Macrae, 1991;

Bruce & Kemp, 1993).

References

Anderson, T. (1937). Variations in the normal range of children's voices, variations in

range of tone audition, variations in pitch discrimination. Doctoral dissertation,

University of Edinburgh.

Archer, J., & Macrae, M. (1991). Gender perceptions of school subjects among 10-11 year

olds. British Journal of Educational Psychology, 61, 99-103.

Barker, A. (1984) Greek musical writings: 1 The musician and his art. Cambridge: CUP.

Bruce, R., & Kemp, A. (1993) Sex-stereotyping in children's preferences for musical

instruments. British Journal of Music Education, 10(3), 213-217.

Buckton, R. (1982). Sing a song of six-year-olds. Wellington: New Zealand Council for

Educational Research.

Cooksey, J. M. (1993). Do adolescent voices 'break' ordo they 'transform'?. Voice, 2(1),

15-39.

Ellis, E. (1993). 'Droners' and singers. Doctoral dissertation, University of Belfast.

Finnegan, R. (1989). The hidden musicians. Cambridge: CUP.

Frank, F., & Sparber, M. (1970). Stimmumfange bei Kindern aus neuer sicht. [Vocal

ranges in children from a new perspective.] Folia Phoniatrica, 22, 397-402.

Greer, R. D., Dorow, L., & Hanser, S. (1973). Music Discrimination Training and the

Music Selection Behaviour of Nursery and Primary Level Children. Bulletin of the

Council for Research in Music Education, 35, 30-43.

Howard, D. M., Angus, J. A., & Welch, G. F. (1994). Singing pitching accuracy from

years 3 to 6 in a primary school. Proceedings, Institute of Acoustics 1 994 Autumn

Conference, Windermere, 24-27 November, 1994. 16(5) 223-230.

Huff-Gackle, L. (1991). The adolescent female voice: The characteristics of change and

stages of development. The ChoralJournal, 57(8), 17-25.

Joyner, D. R. (1969). The monotone problem. Journal of Research in Music Education,

77,115-124.

Madsen, C, Wolfe, D. E., & Madsen, C. H. (1969). The effect of reinforcement and

directional scalar methodology on intonational improvement. Bulletin of the Council

for Research in Music Education, 18, 22-33.

Moore, R. S. (1994). Selected research on children's singing skills. In G. F. Welch & T.

Murao (Eds.), Onchi and singing development (pp. 41-48). London: David Fulton.

Naidr, J., Zboril, M., & Secik, K. (1965). Die pubertalen veranderungen der stimme bei

jungen im verlauf von 5 jahren. [Pubertal voice changes in boys over a period of five

years.] Folia Phoniatrica, 17, 1-18.

This content downloaded from

200.144.238.1 on Thu, 17 Jun 2021 12:14:24 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

160

Norioka, Y. (1994). A surve

& T. Murao (Eds.), Onchi

Fulton.

Phillips, K. H. (1992). Teach

Plumridge, J. M. (1972). Th

published material for chi

sity of Reading.

Rossiter, D. R. (1995) Real-

thesis, University of York.

Rupp, C. E. (1992). The effe

of head voice placement i

University of Missouri at

Rutkowski, J. (1984). Two-y

of Cooksey's theory for

Proceedings, Research Sy

State University of New Y

Sammons, P. (1995). Gende

progress: A longitudinal

Educational Research Jou

Trollinger, L. M. (1994). Se

terly Journal of Music Tea

Welch, G. F. (1979). Vocal

13-31.

Welch, G. F. (1985). Variabili

to sing in tune. Bulletin

238-247.

Welch, G. F. (1986). A developmental view of children's singing. British Journal of

Music Education, 3(3), 295-303.

Welch, G. F. (1994a). Onchi and singing development: Pedagogical implications. In G. F.

Welch & T. Murao (Eds.), Onchi and singing development (pp. 82-95). London:

David Fulton.

Welch, G. F. (1994b). The assessment of singing. Psychology of Music, 22(\), 3-19.

Welch, G. F., Howard, D. M., & Rush, C. (1989). Real-time visual feedback in the

development of vocal pitch accuracy in singing. Psychology of Music, 17(2), 146-

157.

Welch, G. F., & Murao, T. (Eds.). (1994). Onchi and singing development. London: David

Fulton.

Yank Porter, S-. (1977). The effect of multiple discrimination training on the pitch-match-

ing behaviour of uncertain singers. Journal of Research in Music Education, 25,

68-81.

Young, S. (1993). Music in the classroom at key stage 2. In J. Glover & S. Ward (Eds.),

Teaching music in the primary school (pp. 101-133). London: Cassell.

This content downloaded from

200.144.238.1 on Thu, 17 Jun 2021 12:14:24 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

You might also like

- Cross-Cultural Perspectives On Pitch Memory: Sandra E. Trehub, E. Glenn Schellenberg, Takayuki NakataDocument13 pagesCross-Cultural Perspectives On Pitch Memory: Sandra E. Trehub, E. Glenn Schellenberg, Takayuki NakataKhristianKraouliNo ratings yet

- Advancing Interdisciplinary Research in Singing: A Performance PerspectiveDocument6 pagesAdvancing Interdisciplinary Research in Singing: A Performance PerspectivePaulo VianaNo ratings yet

- Música y Lenguaje ComparaciónDocument23 pagesMúsica y Lenguaje Comparaciónmartha diazNo ratings yet

- Francois Et Al 2013 - 8 Years Old With 2 Years StudyDocument6 pagesFrancois Et Al 2013 - 8 Years Old With 2 Years StudyfarawaheedaNo ratings yet

- Vocal Improvisation and Creative Thinking by Australian and American University Jazz SingersDocument13 pagesVocal Improvisation and Creative Thinking by Australian and American University Jazz SingersDévényi-Bakos BettinaNo ratings yet

- The Perceived Impact of Playing Music While Studying: Age and Cultural DifferencesDocument17 pagesThe Perceived Impact of Playing Music While Studying: Age and Cultural DifferencesSimaan HabibNo ratings yet

- Congenital AmusiaDocument21 pagesCongenital Amusiabulletproof_headacheNo ratings yet

- Dankovicova 2007Document49 pagesDankovicova 2007JEREMY SHANDEL BECERRA DELGADONo ratings yet

- Pre-K Music and The Emergent ReaderDocument11 pagesPre-K Music and The Emergent ReaderAli Erin100% (1)

- University of Illinois Press, Council For Research in Music Education Bulletin of The Council For Research in Music EducationDocument14 pagesUniversity of Illinois Press, Council For Research in Music Education Bulletin of The Council For Research in Music EducationJeon KookNo ratings yet

- Texto InglesDocument4 pagesTexto InglesRaimundo LimaNo ratings yet

- Attitudes of Children Toward Singing and Choir Participation and Assessed Singing SkillDocument13 pagesAttitudes of Children Toward Singing and Choir Participation and Assessed Singing Skillli manniiiNo ratings yet

- Neurología y CantoDocument19 pagesNeurología y CantoSebastián Andrés León RojasNo ratings yet

- Sweet-AdolescentFemaleChanging-2015Document20 pagesSweet-AdolescentFemaleChanging-2015stephenieleevos1No ratings yet

- Auditory Perception by Children: Robert G. PetzoldDocument6 pagesAuditory Perception by Children: Robert G. PetzoldpapuenteNo ratings yet

- Do You Hear What I Hear Adams Pedersen Narboni ReprintDocument8 pagesDo You Hear What I Hear Adams Pedersen Narboni ReprintCamille ComasNo ratings yet

- Gender Stereotypes Influence Musical Instrument ChoicesDocument13 pagesGender Stereotypes Influence Musical Instrument ChoicesFausto Gómez GarcíaNo ratings yet

- Neurocognition of Major-Minor and Consonance-DissonanceDocument18 pagesNeurocognition of Major-Minor and Consonance-DissonanceVictor BarrosNo ratings yet

- Everyday Music InfancyDocument25 pagesEveryday Music InfancySistemassocialesNo ratings yet

- Automatic assessment of vocal parametersDocument9 pagesAutomatic assessment of vocal parametersTiago BicalhoNo ratings yet

- Construction of MusicDocument8 pagesConstruction of MusicArdian AriefNo ratings yet

- Music Cognition in Childhood: January 2016Document28 pagesMusic Cognition in Childhood: January 2016João Pedro ReigadoNo ratings yet

- GerryUnrauTrainor 2012 PDFDocument11 pagesGerryUnrauTrainor 2012 PDFLaura F MerinoNo ratings yet

- Abeles - 2009 - Are Musical Instrument Gender Associations ChanginDocument13 pagesAbeles - 2009 - Are Musical Instrument Gender Associations ChanginkehanNo ratings yet

- The Child-Voice in Singing treated from a physiological and a practical standpoint and especially adapted to schools and boy choirsFrom EverandThe Child-Voice in Singing treated from a physiological and a practical standpoint and especially adapted to schools and boy choirsNo ratings yet

- Congential AmusiaDocument14 pagesCongential AmusiaCatherineNo ratings yet

- Annotated Bibliography Final 5Document23 pagesAnnotated Bibliography Final 5api-385015476No ratings yet

- Music Lessons Enchance IQ SchellenbergDocument5 pagesMusic Lessons Enchance IQ SchellenbergClarissa Dewi100% (1)

- Acoustic Similarity of Inner and Outer Circle Varieties of Child-Produced English VowelsDocument17 pagesAcoustic Similarity of Inner and Outer Circle Varieties of Child-Produced English Vowelshye-sook parkNo ratings yet

- Hill, Griffith, Miguel, 2019 - Using Equivalence-Based Instruction To Teach Piano Skills To ChildrenDocument21 pagesHill, Griffith, Miguel, 2019 - Using Equivalence-Based Instruction To Teach Piano Skills To ChildrenVinicius Pereira de SousaNo ratings yet

- Using Songs and Movement to Teach Reading to Aboriginal ChildrenDocument17 pagesUsing Songs and Movement to Teach Reading to Aboriginal ChildrenDiahNo ratings yet

- Neuroscience in Music EducationDocument11 pagesNeuroscience in Music Educationvanessa_alencar_6No ratings yet

- Bruce and Kemp - 1993 - Sex-Stereotyping in Children's Preferences For MusDocument5 pagesBruce and Kemp - 1993 - Sex-Stereotyping in Children's Preferences For MuskehanNo ratings yet

- Factors and Abilities Influencing Sightreading Skill in MusicDocument17 pagesFactors and Abilities Influencing Sightreading Skill in MusicTeresaPeraltaCalvilloNo ratings yet

- This Content Downloaded From 131.161.195.134 On Sun, 13 Jun 2021 15:15:11 UTCDocument8 pagesThis Content Downloaded From 131.161.195.134 On Sun, 13 Jun 2021 15:15:11 UTCCleiton XavierNo ratings yet

- Article With Peer Commentary and Response Absolute Pitch in Infancy and Adulthood: The Role of Tonal StructureDocument9 pagesArticle With Peer Commentary and Response Absolute Pitch in Infancy and Adulthood: The Role of Tonal StructureDaniele PendezaNo ratings yet

- MacPeherson Factors and Abilities Influencing SightrDocument16 pagesMacPeherson Factors and Abilities Influencing SightrLau_mdiNo ratings yet

- 1993 Wolk Coexistence of Disordered PhonologyDocument13 pages1993 Wolk Coexistence of Disordered PhonologyElianaNo ratings yet

- The Whole is Not Different From its PartsDocument17 pagesThe Whole is Not Different From its PartsFarlley DerzeNo ratings yet

- Relationship Between HumorDocument14 pagesRelationship Between HumoreloinagullarNo ratings yet

- Music Our Human SuperpowerDocument6 pagesMusic Our Human SuperpowerLuis Eduardo MolinaNo ratings yet

- Psychological Science: Music Lessons Enhance IQDocument5 pagesPsychological Science: Music Lessons Enhance IQSoporte CeffanNo ratings yet

- Kratus Compositional Strategies Used by Children PDFDocument10 pagesKratus Compositional Strategies Used by Children PDFmanuel1971No ratings yet

- Music's Effects on Language LearningDocument11 pagesMusic's Effects on Language LearningNabilah Mohd NorNo ratings yet

- Musical Learning and Language Development: Jenny R. SaffranDocument5 pagesMusical Learning and Language Development: Jenny R. SaffranDaniele PendezaNo ratings yet

- The Effect of Music On Second Language Vocabulary AcquisitionDocument8 pagesThe Effect of Music On Second Language Vocabulary AcquisitionForefront PublishersNo ratings yet

- Works Works: Swarthmore College Swarthmore CollegeDocument16 pagesWorks Works: Swarthmore College Swarthmore CollegejajajaneinNo ratings yet

- Music and Language Learning Window Birth to Age 10Document6 pagesMusic and Language Learning Window Birth to Age 10Miljana RandjelovicNo ratings yet

- This Content Downloaded From 137.189.171.235 On Fri, 09 Apr 2021 19:23:00 UTCDocument7 pagesThis Content Downloaded From 137.189.171.235 On Fri, 09 Apr 2021 19:23:00 UTCAurora SeasonNo ratings yet

- Carol Hayward - Sight Reading PDFDocument11 pagesCarol Hayward - Sight Reading PDFMatthew Moore100% (1)

- Chen-Hafteck, L. (1997) - Music and Language Development in Early ChildhoodDocument14 pagesChen-Hafteck, L. (1997) - Music and Language Development in Early ChildhoodDani Ruiz CorchadoNo ratings yet

- The Biology and Evolution of Music: A Comparative PerspectiveDocument43 pagesThe Biology and Evolution of Music: A Comparative PerspectiveMakai Péter KristófNo ratings yet

- PreferencesDocument11 pagesPreferencesapi-478106051No ratings yet

- Anderson and Fuller - 2010 - Effect of Music On Reading Comprehension of Junior PDFDocument10 pagesAnderson and Fuller - 2010 - Effect of Music On Reading Comprehension of Junior PDFalexstipNo ratings yet

- The Biology and Evolution of Music: A Comparative PerspectiveDocument43 pagesThe Biology and Evolution of Music: A Comparative PerspectiveHoja de ChopoNo ratings yet

- Effects of Perceptual Experience On Children's and Adults' Perception of Unfamiliar RhythmsDocument8 pagesEffects of Perceptual Experience On Children's and Adults' Perception of Unfamiliar RhythmsmoiNo ratings yet

- Articole MeloterapieDocument46 pagesArticole MeloterapiePatricia Andreea BerbecNo ratings yet

- Model Oup-Accepted-Manuscript-2016Document11 pagesModel Oup-Accepted-Manuscript-2016mengying zhangNo ratings yet

- Fisher-ImpactsVoiceChange-2014Document15 pagesFisher-ImpactsVoiceChange-2014stephenieleevos1No ratings yet

- Musical Predispositions in InfancyDocument17 pagesMusical Predispositions in InfancydanielabanderasNo ratings yet

- This Content Downloaded From 200.144.238.1 On Thu, 17 Jun 2021 12:26:33 UTCDocument13 pagesThis Content Downloaded From 200.144.238.1 On Thu, 17 Jun 2021 12:26:33 UTCAlessandra ZanchettaNo ratings yet

- 2004peretz EtalDocument19 pages2004peretz EtalAlessandra ZanchettaNo ratings yet

- AzulaoDocument1 pageAzulaoAlessandra ZanchettaNo ratings yet

- IMSLP747655-PMLP29257-00. Gloria, RV589 - Conductor ScoreDocument87 pagesIMSLP747655-PMLP29257-00. Gloria, RV589 - Conductor ScoreAlessandra ZanchettaNo ratings yet

- O-Line Grading SystemDocument3 pagesO-Line Grading SystemCoach Brown100% (2)

- Open TuningsDocument17 pagesOpen TuningsRonald OttobreNo ratings yet

- Music8 LAS Q3 Wk4Document2 pagesMusic8 LAS Q3 Wk4Marl Rina EsperanzaNo ratings yet

- Aarzu's SheetDocument17 pagesAarzu's SheetaritrasixthsenseNo ratings yet

- Bridal Ballad ExplicationDocument3 pagesBridal Ballad Explicationceline_ouchNo ratings yet

- CAT27100X - Plots and PaydataDocument82 pagesCAT27100X - Plots and PaydataRik Mertens100% (17)

- D 7 P R 1 1 A: 3-37 Control Relays & Timers General Purpose Plug-In RelaysDocument10 pagesD 7 P R 1 1 A: 3-37 Control Relays & Timers General Purpose Plug-In Relaysrodruren01No ratings yet

- Strategic Business Analysis TutorialsDocument4 pagesStrategic Business Analysis TutorialsAin FatihahNo ratings yet

- List of CEO of Top Business CompaniesDocument4 pagesList of CEO of Top Business CompaniesRaj98% (330)

- Star Fleet - A Print & Play Card GameDocument13 pagesStar Fleet - A Print & Play Card Gamekalel21No ratings yet

- Sunbeam Beadmaker Instruction & Recipe BookletDocument43 pagesSunbeam Beadmaker Instruction & Recipe BookletAlberto SalibyNo ratings yet

- Movement AnalysDocument4 pagesMovement AnalysDanNo ratings yet

- Lenovo B470 Wistron LA470 UMA&Optimus 10250-1 48.4KZ01.011 Rev-1 Schematic PDFDocument102 pagesLenovo B470 Wistron LA470 UMA&Optimus 10250-1 48.4KZ01.011 Rev-1 Schematic PDFابراهيم السعيديNo ratings yet

- Ygg 03Document40 pagesYgg 03JemGirl100% (1)

- Simons-Voss Product Catalogue 2012 enDocument57 pagesSimons-Voss Product Catalogue 2012 enSamir ShammaNo ratings yet

- Contemporary Philippine Arts From The Regions: Quarter 1 - Module 3Document24 pagesContemporary Philippine Arts From The Regions: Quarter 1 - Module 3Taj NgilayNo ratings yet

- Satanic CRAIYON AI READS Various Text Converted To DECIMAL - HEX NCRS and PRODUCES ACCURATE OUTPUT/STEREOTYPESDocument140 pagesSatanic CRAIYON AI READS Various Text Converted To DECIMAL - HEX NCRS and PRODUCES ACCURATE OUTPUT/STEREOTYPESAston WalkerNo ratings yet

- Downloaded From Manuals Search EngineDocument88 pagesDownloaded From Manuals Search Enginepadrino07No ratings yet

- Teleprotection TDocument9 pagesTeleprotection TRichard SyNo ratings yet

- Practice PlanDocument2 pagesPractice Plansin8683% (6)

- Weekly meal plan with breakfast, lunch and dinner optionsDocument1 pageWeekly meal plan with breakfast, lunch and dinner optionsAps RaoNo ratings yet

- Top Medal WinnersDocument24 pagesTop Medal WinnersRitwik GhoshNo ratings yet

- TaydaelectronicsDocument3 pagesTaydaelectronicsshaniquabeallNo ratings yet

- Luxury Hotel Thesis PresenationDocument7 pagesLuxury Hotel Thesis PresenationShaik UmaruddinNo ratings yet

- B.A. (Hons.) Karnatak MusicDocument11 pagesB.A. (Hons.) Karnatak Musicsap tmNo ratings yet

- Marvel - Ultimate Alliance 2 Cheats, Codes, Unlockables - PlayStation 3 - IGNDocument7 pagesMarvel - Ultimate Alliance 2 Cheats, Codes, Unlockables - PlayStation 3 - IGNABernardo VinasNo ratings yet

- SITHCCC013 Assessment 2 - Practical Observation-EditedDocument27 pagesSITHCCC013 Assessment 2 - Practical Observation-EditedSanshuv KarkiNo ratings yet

- Module Dressmaking 9Document16 pagesModule Dressmaking 9Wendy ArnidoNo ratings yet

- Adidas Entry Into North AmericaDocument9 pagesAdidas Entry Into North AmericaGladys WangariNo ratings yet

- Accommodation Inspection Report: Office of The RentalsmanDocument2 pagesAccommodation Inspection Report: Office of The Rentalsmanranisushma1986No ratings yet