Professional Documents

Culture Documents

9 Municipality of Tangkal, Lanao Del Norte v. Balindong

Uploaded by

mei atienzaCopyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

9 Municipality of Tangkal, Lanao Del Norte v. Balindong

Uploaded by

mei atienzaCopyright:

Available Formats

THIRD DIVISION

[G.R. No. 193340. January 11, 2017.]

THE MUNICIPALITY OF TANGKAL, PROVINCE OF LANAO DEL

NORTE, petitioner, vs. HON. RASAD B. BALINDONG, in his

capacity as Presiding Judge, Shari'a District Court, 4th

Judicial District, Marawi City, and HEIRS OF THE LATE

MACALABO ALOMPO, represented by SULTAN DIMNANG B.

ALOMPO, respondents.

DECISION

JARDELEZA, J : p

The Code of Muslim Personal Laws of the Philippines 1 (Code of Muslim

Personal Laws) vests concurrent jurisdiction upon Shari'a district courts over

personal and real actions wherein the parties involved are Muslims, except

those for forcible entry and unlawful detainer. The question presented is

whether the Shari'a District Court of Marawi City has jurisdiction in an action

for recovery of possession filed by Muslim individuals against a municipality

whose mayor is a Muslim. The respondent judge held that it has. We reverse.

I

The private respondents, heirs of the late Macalabo Alompo, filed a

Complaint 2 with the Shari'a District Court of Marawi City (Shari'a District

Court) against the petitioner, Municipality of Tangkal, for recovery of

possession and ownership of a parcel of land with an area of approximately

25 hectares located at Barangay Banisilon, Tangkal, Lanao del Norte. They

alleged that Macalabo was the owner of the land, and that in 1962, he

entered into an agreement with the Municipality of Tangkal allowing the

latter to "borrow" the land to pave the way for the construction of the

municipal hall and a health center building. The agreement allegedly

imposed a condition upon the Municipality of Tangkal to pay the value of the

land within 35 years, or until 1997; otherwise, ownership of the land would

revert to Macalabo. Private respondents claimed that the Municipality of

Tangkal neither paid the value of the land within the agreed period nor

returned the land to its owner. Thus, they prayed that the land be returned

to them as successors-in-interest of Macalabo.

The Municipality of Tangkal filed an Urgent Motion to Dismiss 3 on the

ground of improper venue and lack of jurisdiction. It argued that since it has

no religious affiliation and represents no cultural or ethnic tribe, it cannot be

considered as a Muslim under the Code of Muslim Personal Laws. Moreover,

since the complaint for recovery of land is a real action, it should have been

filed in the appropriate Regional Trial Court of Lanao del Norte.

In its Order 4 dated March 9, 2010, the Shari'a District Court denied the

CD Technologies Asia, Inc. © 2021 cdasiaonline.com

Municipality of Tangkal's motion to dismiss. It held that since the mayor of

Tangkal, Abdulazis A.M. Batingolo, is a Muslim, the case "is an action

involving Muslims, hence, the court has original jurisdiction concurrently with

that of regular/civil courts." It added that venue was properly laid because

the Shari'a District Court has territorial jurisdiction over the provinces of

Lanao del Sur and Lanao del Norte, in addition to the cities of Marawi and

Iligan. Moreover, the filing of a motion to dismiss is a disallowed pleading

under the Special Rules of Procedure in Shari'a Courts. 5 cSEDTC

The Municipality of Tangkal moved for reconsideration, which was

denied by the Shari'a District Court. The Shari'a District Court also ordered

the Municipality of Tangkal to file its answer within 10 days. 6 The

Municipality of Tangkal timely filed its answer 7 and raised as an affirmative

defense the court's lack of jurisdiction.

Within the 60-day reglementary period, the Municipality of Tangkal

elevated the case to us via petition for certiorari, prohibition, and mandamus

with prayer for a temporary restraining order 8 (TRO). It reiterated its

arguments in its earlier motion to dismiss and answer that the Shari'a

District Court has no jurisdiction since one party is a municipality which has

no religious affiliation.

In their Comment, 9 private respondents argue that under the Special

Rules of Procedure in Shari'a Courts, a petition for certiorari, mandamus, or

prohibition against any interlocutory order issued by the district court is a

prohibited pleading. Likewise, the Municipality of Tangkal's motion to dismiss

is disallowed by the rules. They also echo the reasoning of the Shari'a

District Court that since both the plaintiffs below and the mayor of defendant

municipality are Muslims, the Shari'a District Court has jurisdiction over the

case.

In the meantime, we issued a TRO 10 against the Shari'a District Court

and its presiding judge, Rasad Balindong, from holding any further

proceedings in the case below.

II

In its petition, the Municipality of Tangkal acknowledges that generally,

neither certiorari nor prohibition is an available remedy to assail a court's

interlocutory order denying a motion to dismiss. But it cites one of the

exceptions to the rule, i.e., when the denial is without or in excess of

jurisdiction to justify its remedial action. 11 In rebuttal, private respondents

rely on the Special Rules of Procedure in Shari'a Courts which expressly

identifies a motion to dismiss and a petition for certiorari, mandamus, or

prohibition against any interlocutory order issued by the court as prohibited

pleadings. 12

A

Although the Special Rules of Procedure in Shari'a Courts prohibits the

filing of a motion to dismiss, this procedural rule may be relaxed when the

ground relied on is lack of jurisdiction which is patent on the face of the

complaint. As we held in Rulona-Al Awadhi v. Astih: 13

CD Technologies Asia, Inc. © 2021 cdasiaonline.com

Instead of invoking a procedural technicality, the respondent

court should have recognized its lack of jurisdiction over the parties

and promptly dismissed the action, for, without jurisdiction, all its

proceedings would be, as they were, a futile and invalid exercise. A

summary rule prohibiting the filing of a motion to dismiss should not

be a bar to the dismissal of the action for lack of jurisdiction when the

jurisdictional infirmity is patent on the face of the complaint itself, in

view of the fundamental procedural doctrine that the jurisdiction of a

court may be challenged at anytime and at any stage of the action. 14

Indeed, when it is apparent from the pleadings that the court has no

jurisdiction over the subject matter, it is duty-bound to dismiss the case

regardless of whether the defendant filed a motion to dismiss. 15 Thus, in

Villagracia v. Fifth Shari'a District Court , 16 we held that once it became

apparent that the Shari'a court has no jurisdiction over the subject matter

because the defendant is not a Muslim, the court should have motu proprio

dismissed the case. 17

B

An order denying a motion to dismiss is an interlocutory order which

neither terminates nor finally disposes of a case as it leaves something to be

done by the court before the case is finally decided on the merits. Thus, as a

general rule, the denial of a motion to dismiss cannot be questioned in a

special civil action for certiorari which is a remedy designed to correct errors

of jurisdiction and not errors of judgment. 18 As exceptions, however, the

defendant may avail of a petition for certiorari if the ground raised in the

motion to dismiss is lack of jurisdiction over the person of the defendant or

over the subject matter, 19 or when the denial of the motion to dismiss is

tainted with grave abuse of discretion. 20 SDAaTC

The reason why lack of jurisdiction as a ground for dismissal is treated

differently from others is because of the basic principle that jurisdiction is

conferred by law, and lack of it affects the very authority of the court to take

cognizance of and to render judgment on the action 21 — to the extent that

all proceedings before a court without jurisdiction are void. 22 We grant

certiorari on this basis. As will be shown below, the Shari'a District Court's

lack of jurisdiction over the subject matter is patent on the face of the

complaint, and therefore, should have been dismissed outright.

III

The matters over which Shari'a district courts have jurisdiction are

enumerated in the Code of Muslim Personal Laws, specifically in Article 143.

23 Consistent with the purpose of the law to provide for an effective

administration and enforcement of Muslim personal laws among Muslims, 24

it has a catchall provision granting Shari'a district courts original jurisdiction

over personal and real actions except those for forcible entry and unlawful

detainer. 25 The Shari'a district courts' jurisdiction over these matters is

concurrent with regular civil courts, i.e., municipal trial courts and regional

trial courts. 26 There is, however, a limit to the general jurisdiction of Shari'a

district courts over matters ordinarily cognizable by regular courts: such

jurisdiction may only be invoked if both parties are Muslims. If one party is

CD Technologies Asia, Inc. © 2021 cdasiaonline.com

not a Muslim, the action must be filed before the regular courts. 27

The complaint below, which is a real action 28 involving title to and

possession of the land situated at Barangay Banisilon, Tangkal, was filed by

private respondents before the Shari'a District Court pursuant to the general

jurisdiction conferred by Article 143 (2) (b). In determining whether the

Shari'a District Court has jurisdiction over the case, the threshold question is

whether both parties are Muslims. There is no disagreement that private

respondents, as plaintiffs below, are Muslims. The only dispute is whether

the requirement is satisfied because the mayor of the defendant

municipality is also a Muslim.

When Article 143 (2) (b) qualifies the conferment of jurisdiction to

actions "wherein the parties involved are Muslims," the word "parties"

necessarily refers to the real parties in interest. Section 2 of Rule 3 of the

Rules of Court defines real parties in interest as those who stand to be

benefited or injured by the judgment in the suit, or are entitled to the avails

of the suit. In this case, the parties who will be directly benefited or injured

are the private respondents, as real party plaintiffs, and the Municipality of

Tangkal, as the real party defendant. In their complaint, private respondents

claim that their predecessor-in-interest, Macalabo, entered into an

agreement with the Municipality of Tangkal for the use of the land. Their

cause of action is based on the Municipality of Tangkal's alleged failure and

refusal to return the land or pay for its reasonable value in accordance with

the agreement. Accordingly, they pray for the return of the land or the

payment of reasonable rentals thereon. Thus, a judgment in favor of private

respondents, either allowing them to recover possession or entitling them to

rentals, would undoubtedly be beneficial to them; correlatively, it would be

prejudicial to the Municipality of Tangkal which would either be deprived

possession of the land on which its municipal hall currently stands or be

required to allocate funds for payment of rent. Conversely, a judgment in

favor of the Municipality of Tangkal would effectively quiet its title over the

land and defeat the claims of private respondents.

It is clear from the title and the averments in the complaint that Mayor

Batingolo was impleaded only in a representative capacity, as chief

executive of the local government of Tangkal. When an action is defended

by a representative, that representative is not — and neither does he

become — a real party in interest. The person represented is deemed the

real party in interest; 29 the representative remains to be a third party to the

action. 30 That Mayor Batingolo is a Muslim is therefore irrelevant for

purposes of complying with the jurisdictional requirement under Article 143

(2) (b) that both parties be Muslims. To satisfy the requirement, it is the real

party defendant, the Municipality of Tangkal, who must be a Muslim. Such a

proposition, however, is a legal impossibility.

The Code of Muslim Personal Laws defines a "Muslim" as "a person who

testifies to the oneness of God and the Prophethood of Muhammad and

professes Islam." 31 Although the definition does not explicitly distinguish

between natural and juridical persons, it nonetheless connotes the exercise

of religion, which is a fundamental personal right. 32 The ability to testify to

CD Technologies Asia, Inc. © 2021 cdasiaonline.com

the "oneness of God and the Prophethood of Muhammad" and to profess

Islam is, by its nature, restricted to natural persons. In contrast, juridical

persons are artificial beings with "no consciences, no beliefs, no feelings, no

thoughts, no desires." 33 They are considered persons only by virtue of legal

fiction. The Municipality of Tangkal falls under this category. Under the Local

Government Code, a municipality is a body politic and corporate that

exercises powers as a political subdivision of the national government and

as a corporate entity representing the inhabitants of its territory. 34

Furthermore, as a government instrumentality, the Municipality of

Tangkal can only act for secular purposes and in ways that have primarily

secular effects 35 — consistent with the non-establishment clause. 36 Hence,

even if it is assumed that juridical persons are capable of practicing religion,

the Municipality of Tangkal is constitutionally proscribed from adopting,

much less exercising, any religion, including Islam.

The Shari'a District Court appears to have understood the foregoing

principles, as it conceded that the Municipality of Tangkal "is neither a

Muslim nor a Christian." 37 Yet it still proceeded to attribute the religious

affiliation of the mayor to the municipality. This is manifest error on the part

of the Shari'a District Court. It is an elementary principle that a municipality

has a personality that is separate and distinct from its mayor, vice-mayor,

sanggunian, and other officers composing it. 38 And under no circumstances

can this corporate veil be pierced on purely religious considerations — as the

Shari'a District Court has done — without running afoul the inviolability of

the separation of Church and State enshrined in the Constitution. 39 acEHCD

In view of the foregoing, the Shari'a District Court had no jurisdiction

under the law to decide private respondents' complaint because not all of

the parties involved in the action are Muslims. Since it was clear from the

complaint that the real party defendant was the Municipality of Tangkal, the

Shari'a District Court should have simply applied the basic doctrine of

separate juridical personality and motu proprio dismissed the case.

WHEREFORE, the petition is GRANTED. The assailed orders of the

Shari'a District Court of Marawi City in Civil Case No. 201-09 are REVERSED

and SET ASIDE. Accordingly, Civil Case No. 201-09 is DISMISSED.

SO ORDERED.

Velasco, Jr., Bersamin, Reyes and Caguioa, * JJ., concur.

Footnotes

* Designated as Fifth Member of the Third Division per Special Order No. 2417

dated January 4, 2017.

1. Presidential Decree No. 1083 (1977).

2. Rollo , pp. 39-47.

3. Id. at 48-53.

4. Id. at 57-A.

CD Technologies Asia, Inc. © 2021 cdasiaonline.com

5. En Banc Resolution promulgated by the Supreme Court on September 20, 1983.

6. Rollo , p. 76.

7. Id. at 84-89.

8. Id. at 6-37.

9. Id. at 96-105.

10. Id. at 122-123.

11. Id. at 6-8.

12. Id. at 96-97, citing the Special Rules of Procedure in Shari'a Courts, Sec. 13 (a)

& (f).

13. G.R. No. L-81969, September 26, 1988, 165 SCRA 771.

14. Id. at 777. Citations omitted.

15. RULES OF COURT, Rule 9, Sec. 1.

16. G.R. No. 188832, April 23, 2014, 723 SCRA 550.

17. Id. at 565-566.

18. Republic v. Transunion Corporation, G.R. No. 191590, April 21, 2014, 722 SCRA

273, 279.

19. Tung Ho Steel Enterprises Corporation v. Ting Guan Trading Corporation, G.R.

No. 182153, April 7, 2014, 720 SCRA 707, 720.

20. Republic v. Transunion Corporation, supra at 279.

21. Francel Realty Corporation v. Sycip, G.R. No. 154684, September 8, 2005, 469

SCRA 424, 431.

22. Monsanto v. Lim, G.R. No. 178911, September 17, 2014, 735 SCRA 252, 265-

266.

23. Art. 143. Original jurisdiction. —

(1) The Shari'a District Court shall have exclusive original

jurisdiction over:

(a) All cases involving custody, guardianship, legitimacy,

paternity and filiation arising under this Code;

(b) All cases involving disposition, distribution and settlement of

the estate of deceased Muslims, probate of wills, issuance of letters of

administration or appointment of administrators or executors

regardless of the nature or the aggregate value of the property;

(c) Petitions for the declaration of absence and death and for the

cancellation or correction of entries in the Muslim Registries

mentioned in Title VI of Book Two of this Code;

(d) All actions arising from customary contracts in which the

parties are Muslims, if they have not specified which law shall govern

their relations; and

CD Technologies Asia, Inc. © 2021 cdasiaonline.com

(e) All petitions for mandamus, prohibition, injunction, certiorari,

habeas corpus, and all other auxiliary writs and processes in aid of its

appellate jurisdiction.

(2) Concurrently with existing civil courts, the Shari'a District

Court shall have original jurisdiction over:

(a) Petitions by Muslims for the constitution of a family home,

change of name and commitment of an insane person to an asylum;

(b) All other personal and real actions not mentioned in

paragraph 1 (d) wherein the parties involved are Muslims except

those for forcible entry and unlawful detainer, which shall fall under

the exclusive original jurisdiction of the Municipal Circuit Court; and

(c) All special civil actions for interpleader or declaratory relief

wherein the parties are Muslims or the property involved belongs

exclusively to Muslims.

24. CODE OF MUSLIM PERSONAL LAWS, Art. 2 (c).

25. CODE OF MUSLIM PERSONAL LAWS, Art. 143 (2) (b).

26. Tomawis v. Balindong , G.R. No. 182434, March 5, 2010, 614 SCRA 354, 364-

365.

27. Villagracia v. Fifth Shari'a District Court, supra note 16 at 566.

28. A real action is one that affects title to or possession of real property, or an

interest therein. RULES OF COURT, Rule 4, Sec. 1.

29. RULES OF COURT, Rule 3, Sec. 3.

30. Ang v. Ang, G.R. No. 186993, August 22, 2012, 678 SCRA 699, 708-709.

31. CODE OF MUSLIM PERSONAL LAWS, Art. 7 (g).

32. Victoriano v. Elizalde Rope Workers' Union , G.R. No. L-25246, September 12,

1974, 59 SCRA 54, 72.

33. Citizens United v. Federal Election Comm'n , 558 U.S. 310, 466 (2010), J.

Stevens, dissenting.

34. LOCAL GOV'T CODE, Sec. 15.

35. Ang Ladlad LGBT Party v. Commission on Elections, G.R. No. 190582, April 8,

2010, 618 SCRA 32, 59.

36. CONSTITUTION, Art. III, Sec. 5. No law shall be made respecting an

establishment of religion, or prohibiting the free exercise thereof. The

free exercise and enjoyment of religious profession and worship, without

discrimination or preference, shall forever be allowed. No religious test shall

be required for the exercise of civil or political rights.

37. Rollo , p. 57-A.

38. Torio v. Fontanilla, G.R. No. L-29993, October 23, 1978, 85 SCRA 599, 615.

39. CONSTITUTION, Article II, Sec. 6.

CD Technologies Asia, Inc. © 2021 cdasiaonline.com

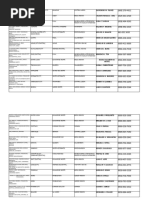

You might also like

- Affidavit of UndertakingDocument65 pagesAffidavit of UndertakingAtty. Bernardino BeringNo ratings yet

- Rayos V City of Manila DigestDocument2 pagesRayos V City of Manila Digestcaaam823No ratings yet

- Administrative Law in Tanzania. A Digest of CasesFrom EverandAdministrative Law in Tanzania. A Digest of CasesRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (12)

- Venue of ActionsDocument8 pagesVenue of ActionsJaime PinuguNo ratings yet

- Certificate of Good Moral CharacterDocument7 pagesCertificate of Good Moral CharacterAlfons Janssen Alpoy Marcera100% (1)

- Simple Guide for Drafting of Civil Suits in IndiaFrom EverandSimple Guide for Drafting of Civil Suits in IndiaRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (4)

- Jurisdiction Over Concubinage May Be Raised At Any StageDocument2 pagesJurisdiction Over Concubinage May Be Raised At Any StageAngelette BulacanNo ratings yet

- Civil Procedure Digests PDFDocument250 pagesCivil Procedure Digests PDFJong PerrarenNo ratings yet

- Answer Ad CautelamDocument7 pagesAnswer Ad CautelamChristoffer Allan Liquigan100% (2)

- 1 Heirs of Babai Guimbangan v. Municipality of KalamnsigDocument4 pages1 Heirs of Babai Guimbangan v. Municipality of KalamnsigRioNo ratings yet

- 5 Mindanao Shopping Destination Corporation Vs Rodrigo R. DuterteDocument2 pages5 Mindanao Shopping Destination Corporation Vs Rodrigo R. Dutertemei atienzaNo ratings yet

- Magsino V Vinluan 2009 IBP ElectionsDocument15 pagesMagsino V Vinluan 2009 IBP ElectionsWuiseNo ratings yet

- People of The Philippines, Petitioner vs. Cora Abella Ojeda, RespondentDocument3 pagesPeople of The Philippines, Petitioner vs. Cora Abella Ojeda, Respondentmei atienza100% (1)

- Pepsi-Cola Bottling Co. vs. Municipality of Tanauan, LeyteDocument2 pagesPepsi-Cola Bottling Co. vs. Municipality of Tanauan, Leytemei atienzaNo ratings yet

- 2 People vs. ComilingDocument3 pages2 People vs. Comilingmei atienzaNo ratings yet

- 2 People vs. ComilingDocument3 pages2 People vs. Comilingmei atienzaNo ratings yet

- Remedial Law CasesDocument63 pagesRemedial Law CasesRoberto Suarez II100% (1)

- Comment On AppealDocument5 pagesComment On Appealmikhael SantosNo ratings yet

- Mobil Phils Vs City Treasurer of MakatiDocument3 pagesMobil Phils Vs City Treasurer of Makatimei atienzaNo ratings yet

- Certificate of AppearanceDocument3 pagesCertificate of AppearanceLoraine AnnaNo ratings yet

- 9 Taisei Shimizu vs. COADocument1 page9 Taisei Shimizu vs. COAmei atienza100% (1)

- Corpo - Digest MarkDocument21 pagesCorpo - Digest MarkMc BagualNo ratings yet

- Calimlim Vs RamirezDocument2 pagesCalimlim Vs RamirezJerik SolasNo ratings yet

- Antiporda Vs Hon. Garchitorena G.R. No. 133289Document3 pagesAntiporda Vs Hon. Garchitorena G.R. No. 133289Jimenez Lorenz0% (1)

- EO70 Briefing For BARMM As of 13 Oct 22Document57 pagesEO70 Briefing For BARMM As of 13 Oct 22Quarter BillNo ratings yet

- Case DigestDocument5 pagesCase DigestCharles RiveraNo ratings yet

- Shari'a Court Lacks Jurisdiction Over MunicipalityDocument2 pagesShari'a Court Lacks Jurisdiction Over MunicipalityakimoNo ratings yet

- Civil Procedure Case DigestDocument333 pagesCivil Procedure Case DigestCentSering100% (2)

- Philippine Long Distance Telephone Company, Inc. vs. City of BacolodDocument1 pagePhilippine Long Distance Telephone Company, Inc. vs. City of Bacolodmei atienzaNo ratings yet

- Rufo de La Cruz Integrated School: Learning Action Cell (LAC) Session Minutes of The MeetingDocument10 pagesRufo de La Cruz Integrated School: Learning Action Cell (LAC) Session Minutes of The MeetingLadylee GepigaNo ratings yet

- Municipality of Tangkal v. BalindongDocument4 pagesMunicipality of Tangkal v. BalindongkathrynmaydevezaNo ratings yet

- Shari'a Court Jurisdiction Over Municipality Land DisputeDocument3 pagesShari'a Court Jurisdiction Over Municipality Land DisputeAngelo John M. ValienteNo ratings yet

- Barangay Clearance Documents from Kauswagan, Lanao del NorteDocument8 pagesBarangay Clearance Documents from Kauswagan, Lanao del NorteJefferson FilipinasNo ratings yet

- 12 Pascual vs. Pangyarihan AngDocument1 page12 Pascual vs. Pangyarihan Angmei atienzaNo ratings yet

- TANGKAL G.R. No. 193340Document6 pagesTANGKAL G.R. No. 193340Fayruzah AbsaryNo ratings yet

- Sharia Court Jurisdiction DisputeDocument3 pagesSharia Court Jurisdiction DisputeAngeline LimpiadaNo ratings yet

- 40 Do Municipal Corporations Acquire Separate and Distinct Personalities From The Officers Composing It - Municipality of Tangkal, Lanao Del Norte v. BalDocument4 pages40 Do Municipal Corporations Acquire Separate and Distinct Personalities From The Officers Composing It - Municipality of Tangkal, Lanao Del Norte v. BalTootsie GuzmaNo ratings yet

- Shari'a Court's jurisdiction over case against Muslim mayorDocument4 pagesShari'a Court's jurisdiction over case against Muslim mayorMichelle Joy ItableNo ratings yet

- G.R. No. 173979 February 12, 2007 AUCTION IN MALINTA, INC., Petitioner, WARREN EMBES LUYABEN, RespondentDocument4 pagesG.R. No. 173979 February 12, 2007 AUCTION IN MALINTA, INC., Petitioner, WARREN EMBES LUYABEN, RespondentAlfred DanezNo ratings yet

- Auction in Malinta, Inc. vs. Warren Embes LuyabenDocument4 pagesAuction in Malinta, Inc. vs. Warren Embes LuyabenjafernandNo ratings yet

- Civil Procedure CasesDocument4 pagesCivil Procedure CasesLois DNo ratings yet

- 124079-1998-Municipality of para Aque v. V.M. RealtyDocument10 pages124079-1998-Municipality of para Aque v. V.M. RealtyShawn LeeNo ratings yet

- Esquivel v. OmbudsmanDocument10 pagesEsquivel v. OmbudsmanPrinceNo ratings yet

- Santos Vs AransanzosDocument5 pagesSantos Vs Aransanzosabigael severinoNo ratings yet

- Radiowealth Finance Company, Inc. vs. Pineda, JR PDFDocument7 pagesRadiowealth Finance Company, Inc. vs. Pineda, JR PDFEmir MendozaNo ratings yet

- 16 - Banares vs. Balising, G.R. No. 13264, March 13, 2000Document6 pages16 - Banares vs. Balising, G.R. No. 13264, March 13, 2000Michelle CatadmanNo ratings yet

- Vivencio B Villagracia Vs 5th Sharia District Court and Roldan E Mala Represented by His Father Hadji Kalam T MalaDocument5 pagesVivencio B Villagracia Vs 5th Sharia District Court and Roldan E Mala Represented by His Father Hadji Kalam T MalajohneurickNo ratings yet

- People Vs EduarteDocument5 pagesPeople Vs EduarteEller-jed M. MendozaNo ratings yet

- Dacoycoy Vs CADocument4 pagesDacoycoy Vs CAKier Christian Montuerto InventoNo ratings yet

- O o o O: Venancio Figueroa y Cervantes, Petitioner People of The Philippines, Respondent FactsDocument10 pagesO o o O: Venancio Figueroa y Cervantes, Petitioner People of The Philippines, Respondent Factssally deeNo ratings yet

- PP vs. Hon. EduarteDocument5 pagesPP vs. Hon. Eduartechristian villamanteNo ratings yet

- Republic of The Philippines Manila Third Division: Supreme CourtDocument4 pagesRepublic of The Philippines Manila Third Division: Supreme CourtArbie Mae SalomaNo ratings yet

- CFI Judge Authority to Rule on City Tax ValidityDocument7 pagesCFI Judge Authority to Rule on City Tax ValidityBenedick LedesmaNo ratings yet

- Monsanto Vs Zerna, GR No.142501, December 7, 2001Document9 pagesMonsanto Vs Zerna, GR No.142501, December 7, 2001Jason BUENANo ratings yet

- 6.) Cruz - v. - Court - of - AppealsDocument10 pages6.) Cruz - v. - Court - of - AppealsBernadette PedroNo ratings yet

- 1 - Land Bank of The Philippines v. Court of Appeals G.R. No. 221636Document5 pages1 - Land Bank of The Philippines v. Court of Appeals G.R. No. 221636Shash BernardezNo ratings yet

- 1 CasesDocument11 pages1 Casesnaim indahiNo ratings yet

- Manalang Vs RickhardsDocument3 pagesManalang Vs RickhardsCJ KhaleesiNo ratings yet

- I.18 San Miguel Corp Vs Avelino GR No. L-39699 03141979 PDFDocument3 pagesI.18 San Miguel Corp Vs Avelino GR No. L-39699 03141979 PDFbabyclaire17No ratings yet

- 6.-Racpan v. Barroga-HaighDocument3 pages6.-Racpan v. Barroga-HaighJo Ellaine TorresNo ratings yet

- RULES ON VENUEDocument27 pagesRULES ON VENUERed NavarroNo ratings yet

- Petitioner Vs Vs Respondents: First DivisionDocument5 pagesPetitioner Vs Vs Respondents: First DivisionRobert Jhon Castro SalazarNo ratings yet

- Lpc-Case Digest OutputDocument10 pagesLpc-Case Digest OutputKarl Lorenzo BabianoNo ratings yet

- Radiowealth Finance Co. Inc. v. Nolasco, G.R. No. 227146, November 14, 2016Document4 pagesRadiowealth Finance Co. Inc. v. Nolasco, G.R. No. 227146, November 14, 2016CHRISTY NGALOYNo ratings yet

- 16 Rayos v. City of Manila20220106-11-Rqr0ctDocument5 pages16 Rayos v. City of Manila20220106-11-Rqr0ctEd Therese BeliscoNo ratings yet

- Third Division June 6, 2018 G.R. No. 234499 RUDY L. RACPAN, Petitioner SHARON BARROGA-HAIGH, Respondent Decision Velasco, JR., J.: Nature of The CaseDocument9 pagesThird Division June 6, 2018 G.R. No. 234499 RUDY L. RACPAN, Petitioner SHARON BARROGA-HAIGH, Respondent Decision Velasco, JR., J.: Nature of The CaseRemy BedañaNo ratings yet

- Rayos Vs City of ManilaDocument2 pagesRayos Vs City of ManilaJiHahn PierceNo ratings yet

- Quiambao Vs OsorioDocument4 pagesQuiambao Vs Osoriohainako3718No ratings yet

- Auction in Malinta v. Luyaben PDFDocument5 pagesAuction in Malinta v. Luyaben PDFBianca BncNo ratings yet

- Bernardo Manalang v. Elvira Tuason De Rickards Ruling on Ejectment CasesDocument2 pagesBernardo Manalang v. Elvira Tuason De Rickards Ruling on Ejectment CasesLily CallaNo ratings yet

- Court Rules on Venue DismissalsDocument72 pagesCourt Rules on Venue DismissalsMerGonzagaNo ratings yet

- Saint Mary Crusade V Hon. Teodoro RielDocument5 pagesSaint Mary Crusade V Hon. Teodoro RielRaiza SunggayNo ratings yet

- Supreme Court Decisions on JurisdictionDocument55 pagesSupreme Court Decisions on JurisdictionAlmarius CadigalNo ratings yet

- De Guzman Vs Ochoa Rule 15 19Document4 pagesDe Guzman Vs Ochoa Rule 15 19Lsly C WngNo ratings yet

- Ramon V. Sison For Petitioner. Public Attorney's Office For Private RespondentDocument52 pagesRamon V. Sison For Petitioner. Public Attorney's Office For Private RespondentDiego FerrerNo ratings yet

- 125839-1996-Catholic Bishop of Balanga v. Court ofDocument12 pages125839-1996-Catholic Bishop of Balanga v. Court ofCeslhee AngelesNo ratings yet

- Jardine Davis Insurance vs. AliposaDocument2 pagesJardine Davis Insurance vs. Aliposamei atienzaNo ratings yet

- Coca Cola Bottlers vs. City of ManilaDocument2 pagesCoca Cola Bottlers vs. City of Manilamei atienzaNo ratings yet

- Digital Telecommunications Vs Province of Pangasinan-DigestDocument3 pagesDigital Telecommunications Vs Province of Pangasinan-Digestmei atienzaNo ratings yet

- Progressive Development Corporation vs. Quezon CityDocument2 pagesProgressive Development Corporation vs. Quezon Citymei atienzaNo ratings yet

- Pepsi Cola vs. City of ButuanDocument3 pagesPepsi Cola vs. City of Butuanmei atienzaNo ratings yet

- Drilon vs. LimDocument2 pagesDrilon vs. Limmei atienzaNo ratings yet

- Accused-Appellant.: People of The Philippines, Plaintiff-Appellee, vs. John Happy Domingo Y CaragDocument1 pageAccused-Appellant.: People of The Philippines, Plaintiff-Appellee, vs. John Happy Domingo Y Caragmei atienzaNo ratings yet

- 14 Luz R. Yamane Vs BA Lepanto Condominium CorporationDocument3 pages14 Luz R. Yamane Vs BA Lepanto Condominium Corporationmei atienzaNo ratings yet

- NPC vs. Provincial Government of BataanDocument2 pagesNPC vs. Provincial Government of Bataanmei atienzaNo ratings yet

- 4 Chua v. Spouses GoDocument11 pages4 Chua v. Spouses Gomei atienzaNo ratings yet

- Respondent.: Teresita Alcantara Vergara, Petitioner, vs. People of The PhilippinesDocument3 pagesRespondent.: Teresita Alcantara Vergara, Petitioner, vs. People of The Philippinesmei atienzaNo ratings yet

- FPIC vs. CADocument1 pageFPIC vs. CASara Andrea SantiagoNo ratings yet

- Oposa V FactoranDocument22 pagesOposa V FactorantheresagriggsNo ratings yet

- 3 Hygienic Packaging Corp. v. Nutri-Asia, Inc.Document20 pages3 Hygienic Packaging Corp. v. Nutri-Asia, Inc.mei atienzaNo ratings yet

- 1 Daniel vs. E.B. VillarosaDocument6 pages1 Daniel vs. E.B. Villarosamei atienzaNo ratings yet

- 5 Batama Farmer's Cooperative Marketing Association, Inc. v. RosalDocument9 pages5 Batama Farmer's Cooperative Marketing Association, Inc. v. Rosalmei atienzaNo ratings yet

- Respondent.: Teresita Alcantara Vergara, Petitioner, vs. People of The PhilippinesDocument3 pagesRespondent.: Teresita Alcantara Vergara, Petitioner, vs. People of The Philippinesmei atienzaNo ratings yet

- PEOPLE OF THE PHILIPPINES, Plaintiff-Appellee, vs. GOLEM SOTA and AMIDAL GADJADLI, Accused-AppellantsDocument2 pagesPEOPLE OF THE PHILIPPINES, Plaintiff-Appellee, vs. GOLEM SOTA and AMIDAL GADJADLI, Accused-Appellantsmei atienzaNo ratings yet

- PEOPLE OF THE PHILIPPINES, Plaintiff-Appellee VS. ISABELO PUNO y GUEVARRA, Alias "Beloy," and ENRIQUE AMURAO y PUNO, Alias "Enry," Accused-AppellantsDocument3 pagesPEOPLE OF THE PHILIPPINES, Plaintiff-Appellee VS. ISABELO PUNO y GUEVARRA, Alias "Beloy," and ENRIQUE AMURAO y PUNO, Alias "Enry," Accused-Appellantsmei atienzaNo ratings yet

- 8 Montenegro vs. COADocument1 page8 Montenegro vs. COAmei atienzaNo ratings yet

- 5 Qatar Airways vs. CIRDocument1 page5 Qatar Airways vs. CIRmei atienzaNo ratings yet

- 2013 Nce Examinees-WebDocument312 pages2013 Nce Examinees-WebFiedder MangudadatuNo ratings yet

- Class Schedule 2023-2024Document6 pagesClass Schedule 2023-2024Almairah SumpinganNo ratings yet

- PawndirDocument26 pagesPawndirRaj BautistaNo ratings yet

- Accomplishment 2019-2020Document35 pagesAccomplishment 2019-2020CHERISH JANE LOMOLJONo ratings yet

- Brgy Id-001Document2 pagesBrgy Id-001Mandy NoorNo ratings yet

- 2019 Executive Order 5 - Municipal Peace and Order Council (Mpoc)Document2 pages2019 Executive Order 5 - Municipal Peace and Order Council (Mpoc)Ashreffah Diacat100% (1)

- Patrol 101 SOP for Linamon Municipal Police StationDocument15 pagesPatrol 101 SOP for Linamon Municipal Police StationOga TatsumiNo ratings yet

- List of Philippine Municipalities by Income ClassDocument30 pagesList of Philippine Municipalities by Income Classfredelino jumbas50% (2)

- Rufu Dela Cruz Intervention Plan Increases MasteryDocument6 pagesRufu Dela Cruz Intervention Plan Increases MasteryVENGIE PAMANNo ratings yet

- PANOLOON - CLASS PROGRAM SY 2023 2024 EditedDocument9 pagesPANOLOON - CLASS PROGRAM SY 2023 2024 EditedARCELIE PALMANo ratings yet

- Grpsale0121418ncr (GS) PDFDocument26 pagesGrpsale0121418ncr (GS) PDFNullus cumunisNo ratings yet

- Weekly Learning Monitoring ToolDocument6 pagesWeekly Learning Monitoring ToolJaneDandanNo ratings yet

- Summer Reading Camp Action PlanDocument4 pagesSummer Reading Camp Action PlanCharlyn AyingNo ratings yet

- Smea PROPOSALDocument4 pagesSmea PROPOSALNoeme VillarealNo ratings yet

- Certificates LayoutDocument8 pagesCertificates LayoutJam R LoremaNo ratings yet

- Fireline Established 2019 MayDocument15 pagesFireline Established 2019 MayAlga Zalli Datu-daculaNo ratings yet

- Arts 4 - Quarter1Document44 pagesArts 4 - Quarter1Rhey GalarritaNo ratings yet

- Alonto FamilyDocument4 pagesAlonto FamilyZane Wilson Avanzado BarredoNo ratings yet

- Cumulative MGB Brgy List 15 December 2021 2AMDocument196 pagesCumulative MGB Brgy List 15 December 2021 2AMEnp Titus VelezNo ratings yet

- RA-114731 - PROFESSIONAL TEACHER - Secondary (English) - Pagadian - 9-2019 PDFDocument69 pagesRA-114731 - PROFESSIONAL TEACHER - Secondary (English) - Pagadian - 9-2019 PDFPhilBoardResultsNo ratings yet

- AKAP Resolution For DonationDocument2 pagesAKAP Resolution For Donationnorhana solaiman-imam100% (1)

- Sports Implementation PlanDocument4 pagesSports Implementation PlanEve MejosNo ratings yet

- Office of The Municipal MayorDocument4 pagesOffice of The Municipal MayorNiniay MohammadNo ratings yet