Professional Documents

Culture Documents

PTSD Assessment in The Military

Uploaded by

Robiul Islam0 ratings0% found this document useful (0 votes)

40 views3 pagesCertain scales have been developed that specifically target military personnel.

PTSD Checklist-Military Version (12).

The Mississippi Scale for Combat-Related PTSD (M-PTSD), specifically a screening and diagnostic instrument for combat-related PTSD (20), which validated as well for treatment seeking (21) and community samples (22).

The Combat Exposure Scale measures the level of war time stress of veterans, an instrument with strong internal consistency (α = 0.85) as well as a high test–retes

Original Title

PTSD Assessment in the Military

Copyright

© © All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

DOCX, PDF, TXT or read online from Scribd

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCertain scales have been developed that specifically target military personnel.

PTSD Checklist-Military Version (12).

The Mississippi Scale for Combat-Related PTSD (M-PTSD), specifically a screening and diagnostic instrument for combat-related PTSD (20), which validated as well for treatment seeking (21) and community samples (22).

The Combat Exposure Scale measures the level of war time stress of veterans, an instrument with strong internal consistency (α = 0.85) as well as a high test–retes

Copyright:

© All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

Download as DOCX, PDF, TXT or read online from Scribd

0 ratings0% found this document useful (0 votes)

40 views3 pagesPTSD Assessment in The Military

Uploaded by

Robiul IslamCertain scales have been developed that specifically target military personnel.

PTSD Checklist-Military Version (12).

The Mississippi Scale for Combat-Related PTSD (M-PTSD), specifically a screening and diagnostic instrument for combat-related PTSD (20), which validated as well for treatment seeking (21) and community samples (22).

The Combat Exposure Scale measures the level of war time stress of veterans, an instrument with strong internal consistency (α = 0.85) as well as a high test–retes

Copyright:

© All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

Download as DOCX, PDF, TXT or read online from Scribd

You are on page 1of 3

Certain scales have been developed that specifically target military personnel.

i. PTSD Checklist-Military Version (12).

ii. The Mississippi Scale for Combat-Related PTSD (M-PTSD), specifically a screening and

diagnostic instrument for combat-related PTSD (20), which validated as well for

treatment seeking (21) and community samples (22).

iii. The Combat Exposure Scale measures the level of war time stress of veterans, an

instrument with strong internal consistency (α = 0.85) as well as a high test–retest

reliability (r = 0.97) (23).

iv. The PK scale, a subscale of the MMPI-2, whose items were selected based on their

ability to differentiate among veterans diagnosed with PTSD and those who were not.

This scale has strong reliability (α = 0.95) and good test–retest reliability (r = 0.94) (7).

v. The SCID PTSD module is frequently used to assess presence of PTSD among veterans

as well (24,25).

vi. Additional scales have been used to target assessment of PTSD among veterans,

including the M-PTSD (26–29), the PK scale (30,31) or the CAPS (29,32).

The prevalence of PTSD diagnosis varies depending on the assessment method. One study

compared three measures of PTSD among American and Korean War prisoners of war (POWs).

It compared an unstructured self-report interview measure, the M-PTSD and the DSM-III-R

SCID instrument. The data showed that partially unstructured interviews and the M-PTSD

yielded PTSD prevalence rates of 31 and 33%, respectively, which were significantly higher than

the rate of 26% yielded by the SCID. Both the unstructured clinical interview and the M-PTSD

had equal accuracy, consistently disagreeing with the SCID from 7 to 15% of assessed cases

(33).

Such differences in rates, depending on the assessment instrument may hold significance.

According to the study (33) there may be different explanations; self-report instruments like the

M-PTSD do not reflect DSM criteria as comprehensibly as the SCID. Symptoms may differ in

both intensity and kind among older and younger prisoners of war. In the paradoxical side, it is

possible for an individual to be diagnosed with PTSD while reporting minimal stress levels; in

fact, subjective stress can be seen as a confounding factor that can have an influence on

diagnosis (34).

A PTSD-negative clinical interview occurring simultaneously with a PTSD confirmation of

PTSD (or also with a moderate-to-low M-PTSD score) may be indicative of chronic, but stable,

PTSD. Such chronic and stable PTSD may not be clinically relevant and may not require focused

intervention. They recommend to measure symptom intensity with such instruments as the CAPS

(16). Such an approach could decrease PTSD-positive diagnoses among subjects with low levels

of distress (33).

Go to:

Allostasis and PTSD

Allostasis and the Response to Stress

Allostasis refers to the psychobiological regulatory process that brings about stability through

change of state consequential to stress. Psycho-emotional stress can be defined as a perceived

lack, or loss of fit of one's perceived abilities and the demands of one's inner world or the

surrounding environment (i.e. person/environment fit). Traumatic events that trigger PTSD are

perfect examples of such onerous demands that lead to the conscious or unconscious perception

on the part of the subject of not being able to cope (35).

The perception of stress is often associated with psychological manifestations of anxiety,

irritability and anger, sad and depressed moods, tension and fatigue, and with certain bodily

manifestations, including perspiration, blushing or blanching of the face, increased heart beat or

decreased blood pressure, and intestinal cramps and discomfort. These signs mirror the spectrum

of psychobiological symptoms in PTSD. These manifestations are generally associated with the

nature of the stress, its duration, chronicity and severity. A group of symptoms, now referred to

as the sickness behavior, is also noted that is associated with clinically relevant changes in the

balance between the psychoneuroendocrine and the immune systems (35–37).

It was the renowned nineteenth-century French physiologist, Claude Bernard (1813–1878) who

first proposed that defense of the internal milieu (le milieu intérieur, 1856) is a fundamental

feature of physiological regulation in mammalian systems, whence the phrase ‘homeostasis’ was

coined. By the early 1930s, Walter Cannon (1871–1945) proposed that organisms engage in a

dynamic process of adjustment of the physiological balance of the internal milieu in response to

changing environmental conditions. Hans Selye (1907–1982) established the cardinal points of

the ‘Generalized Stress Response’ in his demonstration of concerted physiological responses to

stressful challenges.

Stress alters the regulation of both the sympathetic and the parasympathetic branches of the

autonomic nervous system, with consequential alterations in hypothalamic control of the

endocrine response controlled by the pituitary gland. Autonomic activation and the elevation of

hormones, including those produced by the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis, play a pivotal

role in regulating cell-mediated immune surveillance mechanisms, including the production of

cytokines that control inflammatory and healing events (35,36). In brief, the perception of stress

leads to a significant load upon physiological regulation, including circadian regulation, sleep

and psychoneuroendocrine-immune interaction.

In brief, stress is profound alterations in the cross-regulation and interaction of the hormonal-

immune regulatory axis. The experience of stress, as well as that of traumatic events and the

anxiety-laden recollections thereof, produce a primary endocrine response, which involves the

release of glucocorticoids (GCs). GCs regulate cellular immune activity in vivo systemically and

locally. They block the production of pro-inflammatory cytokines (e.g. interleukin[IL]-1β IL-6)

and TH1 cytokines (e.g. IL-2) at the molecular level in vitro and in vivo, but may have little

effects upon TH2 cytokines (e.g. IL-4). The net effect of challenging immune cells with GC is to

impair immune T cell activation and proliferation, while maintaining antibody production. The

secretion of GC by the adrenal cortex is under the control of the anterior pituitary

adrenocorticotropin hormone (ACTH). Immune challenges release pro-inflammatory cytokines

(e.g. IL-1β, IL-6), which induce hypothalamic secretion of the ACTH inducing factor

corticotropin releasing factor (CRF) in animal and in human subjects. Stressful stimuli also lead

to the significant activation of the sympathetic nervous system and a rise in the levels of pro-

inflammatory cytokines (i.e. IL-1β and IL-6). It follows that the consequences of stress are not

uniform. The psychopathological and the physiopathological impacts of stress may be

significantly greater in certain people, compared with those of others. The impact of stress is

dynamic and multifaceted and the same person may exhibit a variety of manifestations of the

psychoneuroendocrine-immune stress response with varying degrees of severity at different

times. The outcome of stress can be multivalent (35).

You might also like

- Lesson Bundle Breathing Foundations 1.5 G1aqan PDFDocument57 pagesLesson Bundle Breathing Foundations 1.5 G1aqan PDFTrevor RashadNo ratings yet

- Chapter 5: Stress and Physical and Mental HealthDocument9 pagesChapter 5: Stress and Physical and Mental HealthJuliet Anne Buangin Alo100% (1)

- Effects of Stress and Psychological Disorders On The Immune SystemDocument7 pagesEffects of Stress and Psychological Disorders On The Immune SystemTravis BarkerNo ratings yet

- Outline of Anatomy and Physiology (Semifinal-Final)Document8 pagesOutline of Anatomy and Physiology (Semifinal-Final)Jhason John J. CabigonNo ratings yet

- Cellular respiration and fermentation explainedDocument20 pagesCellular respiration and fermentation explainedTasfia QuaderNo ratings yet

- 7 Drug StudyDocument17 pages7 Drug StudyMa. Mechile MartinezNo ratings yet

- RN, MS, CCRN, Sheree Comer - Critical Care Nursing Care Plan (1998)Document376 pagesRN, MS, CCRN, Sheree Comer - Critical Care Nursing Care Plan (1998)fega.satriaNo ratings yet

- AHA ACLS Written Test: Ready To Study? Start With FlashcardsDocument8 pagesAHA ACLS Written Test: Ready To Study? Start With FlashcardssallyNo ratings yet

- Cell Biology Assays: Essential MethodsFrom EverandCell Biology Assays: Essential MethodsFanny JaulinNo ratings yet

- 165 FullDocument18 pages165 Fullblushing.lilithNo ratings yet

- DNB 29 4 407 20 Hus PDFDocument14 pagesDNB 29 4 407 20 Hus PDFthedi28No ratings yet

- Maladaptive Autonomic Regulation in PTSD Accelerates Physiological AgingDocument12 pagesMaladaptive Autonomic Regulation in PTSD Accelerates Physiological AgingHelena QuintNo ratings yet

- Accepted Manuscript: Une Adrian J. BradleyDocument63 pagesAccepted Manuscript: Une Adrian J. BradleyJuliana MejiaNo ratings yet

- Rastorno DE Estrés Postraumático UNA Revisión DEL Tema Segunda ParteDocument11 pagesRastorno DE Estrés Postraumático UNA Revisión DEL Tema Segunda ParteLeon Suárez AcuarioNo ratings yet

- Posttraumatic Stress Disorder: From Diagnosis To Prevention: Review Open AccessDocument7 pagesPosttraumatic Stress Disorder: From Diagnosis To Prevention: Review Open AccessStardya RuntuwarowNo ratings yet

- Psychooncology PsychoneuroimmunologyDocument4 pagesPsychooncology PsychoneuroimmunologypazNo ratings yet

- Example ANOVADocument7 pagesExample ANOVAmisbahshakirNo ratings yet

- Artikel PTSS 10 QuestionnaireDocument17 pagesArtikel PTSS 10 QuestionnaireTELEPSIHIJATARNo ratings yet

- Stress Induced Immunosupression and Physical PerformanceDocument4 pagesStress Induced Immunosupression and Physical PerformanceJoão OliveiraNo ratings yet

- Reduced Vagal Tone in Women With The FMR1 Premutation Is Associated With FMR1 mRNA But Not Depression or AnxietyDocument16 pagesReduced Vagal Tone in Women With The FMR1 Premutation Is Associated With FMR1 mRNA But Not Depression or Anxiety6 ANo ratings yet

- Brenner 2018Document6 pagesBrenner 2018Yeray GranadoNo ratings yet

- Decreased Premotor Cortex Volume in Victims of Urban Violence With Posttraumatic Stress DisorderDocument6 pagesDecreased Premotor Cortex Volume in Victims of Urban Violence With Posttraumatic Stress DisorderJoeNo ratings yet

- RSCH I PTSPDocument9 pagesRSCH I PTSPAleksa BozinovicNo ratings yet

- The Effectiveness of Interpersonal Psychotherapy For Posttraumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD)Document10 pagesThe Effectiveness of Interpersonal Psychotherapy For Posttraumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD)IJAR JOURNALNo ratings yet

- Subthreshold Posttraumatic Stress Disord PDFDocument10 pagesSubthreshold Posttraumatic Stress Disord PDFJørgen CarlsenNo ratings yet

- The Pathogenetic Link Between Stress and Rheumatic DiseasesDocument27 pagesThe Pathogenetic Link Between Stress and Rheumatic Diseaseskj185No ratings yet

- 102 FullDocument10 pages102 FullBney MaharjanNo ratings yet

- Emotion Dysregulation and HRV VeteransDocument12 pagesEmotion Dysregulation and HRV VeteransRafael CapaverdeNo ratings yet

- Brain, Behavior, and Immunity: Thaddeus W.W. Pace, Christine M. HeimDocument8 pagesBrain, Behavior, and Immunity: Thaddeus W.W. Pace, Christine M. HeimmarielaNo ratings yet

- A Meta-Analysis of Risk Factors For Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD) in Adults and Children After EarthquakesDocument20 pagesA Meta-Analysis of Risk Factors For Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD) in Adults and Children After EarthquakesHanifah NLNo ratings yet

- Effects of Psych Interventions on HIV Disease MarkersDocument16 pagesEffects of Psych Interventions on HIV Disease MarkersLaviniaNo ratings yet

- Antioxidants 09 00107 v2Document23 pagesAntioxidants 09 00107 v2Kak LongNo ratings yet

- PRD 12036Document12 pagesPRD 12036Rolando Jorge TerrazasNo ratings yet

- JEPonlineAPRIL2013 WyattDocument12 pagesJEPonlineAPRIL2013 WyattBryan SmithNo ratings yet

- Lykken (1957)Document5 pagesLykken (1957)Tadhg Euan DalyNo ratings yet

- Immune System Contributions To The Pathophysiology of DepressionDocument10 pagesImmune System Contributions To The Pathophysiology of DepressionMoh Hendra Setia LNo ratings yet

- Banerjee 2017Document26 pagesBanerjee 2017Vincent VeldmanNo ratings yet

- Cancer Dan Stress PsikososialDocument15 pagesCancer Dan Stress PsikososialYudha HudayaNo ratings yet

- TMP B187Document9 pagesTMP B187FrontiersNo ratings yet

- Jurnal Hematologi 2 InggrisDocument7 pagesJurnal Hematologi 2 InggrisFajar Nour CholisNo ratings yet

- Blanchard Et Al 1996 Psychometric Properties of The PTSD Checklist (PCL)Document5 pagesBlanchard Et Al 1996 Psychometric Properties of The PTSD Checklist (PCL)Florina AnichitoaeNo ratings yet

- 1993 Wheatley Et Al Stress and IllnessDocument7 pages1993 Wheatley Et Al Stress and Illnessandy19791No ratings yet

- Depression The Predisposing Influence of Stress PDFDocument50 pagesDepression The Predisposing Influence of Stress PDFAkanksha KotibhaskarNo ratings yet

- Higher Cortisol Levels in Abuse-Related PTSD After Traumatic RemindersDocument34 pagesHigher Cortisol Levels in Abuse-Related PTSD After Traumatic RemindersIván CornuNo ratings yet

- Case Study - PTSD Final PaperDocument29 pagesCase Study - PTSD Final PaperMay PerezNo ratings yet

- Moroni2021 Article BeyondNeuropsychiatricManifestDocument8 pagesMoroni2021 Article BeyondNeuropsychiatricManifestrut bNo ratings yet

- Lazarus 1974Document13 pagesLazarus 1974Yudha PratamaNo ratings yet

- Medical Hypotheses 9: 331-335, 1982Document5 pagesMedical Hypotheses 9: 331-335, 1982Omar DaherNo ratings yet

- TMP 3 F13Document10 pagesTMP 3 F13FrontiersNo ratings yet

- World Psychiatry - 2019 - Bryant - Post Traumatic Stress Disorder A State of The Art Review of Evidence and ChallengesDocument11 pagesWorld Psychiatry - 2019 - Bryant - Post Traumatic Stress Disorder A State of The Art Review of Evidence and ChallengesHesti Juwita P.No ratings yet

- Art:10.1186/s12895 015 0026 XDocument8 pagesArt:10.1186/s12895 015 0026 XjesikaNo ratings yet

- Posttraumatic Stress Disorder Epidemiology, Pathophysiology, Clinical Manifestations, and DiagnosisDocument9 pagesPosttraumatic Stress Disorder Epidemiology, Pathophysiology, Clinical Manifestations, and Diagnosisisa_horejsNo ratings yet

- Stress in The Indian Armed Forces: How True and What To Do?: EditorialDocument3 pagesStress in The Indian Armed Forces: How True and What To Do?: EditorialYashobhit SharmaNo ratings yet

- Trident University Courtney Riddle Module 4: Session Long Project PSY101: Intro To Psychology Professor: Wajma Aslami March 8, 2020Document7 pagesTrident University Courtney Riddle Module 4: Session Long Project PSY101: Intro To Psychology Professor: Wajma Aslami March 8, 2020coffeeandstrangeNo ratings yet

- Nihm Molekular Neurobiologi Deprsi 2007Document10 pagesNihm Molekular Neurobiologi Deprsi 2007srihandayani1984No ratings yet

- Salivary Cortisol and A-Amylase: Subclinical Indicators of Stress As Cardiometabolic RiskDocument8 pagesSalivary Cortisol and A-Amylase: Subclinical Indicators of Stress As Cardiometabolic RiskmalakNo ratings yet

- Early Life Stress and Pediatric Posttraumatic Stress DisorderDocument16 pagesEarly Life Stress and Pediatric Posttraumatic Stress DisorderDra. María José CastilloNo ratings yet

- Posttraumatic Stress Disorder and Depression Following Trauma: Understanding ComorbidityDocument7 pagesPosttraumatic Stress Disorder and Depression Following Trauma: Understanding ComorbiditySharon AdeleNo ratings yet

- Emotion Modulation in PTSD: Clinical and Neurobiological Evidence For A Dissociative SubtypeDocument8 pagesEmotion Modulation in PTSD: Clinical and Neurobiological Evidence For A Dissociative SubtypeKarla Katrina CajigalNo ratings yet

- Dar2019 Article PsychosocialStressAndCardiovasDocument17 pagesDar2019 Article PsychosocialStressAndCardiovaskarine schmidtNo ratings yet

- HPA Axis in MDDDocument6 pagesHPA Axis in MDDMarie SalomonováNo ratings yet

- Psych On Euro ImmunologyDocument26 pagesPsych On Euro ImmunologyWhisperer BowenNo ratings yet

- PDF 157105 89671Document14 pagesPDF 157105 89671Krikunov KaNo ratings yet

- ART07Document9 pagesART07Natalia PanchueloNo ratings yet

- Literature Review Post Traumatic Stress DisorderDocument7 pagesLiterature Review Post Traumatic Stress Disorderc5r08vf7100% (1)

- Psychological Stress During Exercise Lymphocyte Subset Redistribution in FirefightersDocument7 pagesPsychological Stress During Exercise Lymphocyte Subset Redistribution in FirefightersFlorentina SisuNo ratings yet

- Implementing StrategyDocument14 pagesImplementing StrategyRobiul IslamNo ratings yet

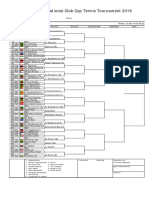

- Mens Singles DrawDocument1 pageMens Singles DrawRobiul IslamNo ratings yet

- BPL - Jully-2019 - Reschedule - FixtureDocument1 pageBPL - Jully-2019 - Reschedule - FixtureRobiul IslamNo ratings yet

- Big CertificateDocument1 pageBig CertificateRobiul IslamNo ratings yet

- ListDocument1 pageListRobiul IslamNo ratings yet

- Udemy Certificate 2Document1 pageUdemy Certificate 2Robiul IslamNo ratings yet

- Udemy Certificate 2Document1 pageUdemy Certificate 2Robiul IslamNo ratings yet

- Basophilia and RBC Maturation StagesDocument6 pagesBasophilia and RBC Maturation StagesDANIELLE JOYCE BACSALNo ratings yet

- Chapter 3 Fluids and Electrolytes - Acid-Base BalanceDocument8 pagesChapter 3 Fluids and Electrolytes - Acid-Base BalanceDiony CruzNo ratings yet

- Effect of Systolic and DiastolicDocument20 pagesEffect of Systolic and Diastoliccupuwatie cahyaniNo ratings yet

- 5 Emergency Neurological Life Support Intracranial HypertensionDocument11 pages5 Emergency Neurological Life Support Intracranial HypertensionEmir Dominguez BetanzosNo ratings yet

- Chemiosmotic TheoryDocument42 pagesChemiosmotic TheoryM.PRASAD NAIDUNo ratings yet

- P4-Obesity and The Regulation of Body MassDocument8 pagesP4-Obesity and The Regulation of Body MassOcta RenitaNo ratings yet

- Blood ComponentsDocument2 pagesBlood ComponentsParul ShahNo ratings yet

- Antiarrhythmic DrugsDocument42 pagesAntiarrhythmic DrugsDr Hotimah HotimahNo ratings yet

- Physiological Changes of PregnancyDocument40 pagesPhysiological Changes of PregnancyAita AladianseNo ratings yet

- Training HorsesDocument70 pagesTraining HorsesHernan AndresNo ratings yet

- St. Paul College Nursing ABG Analysis & Acid-Base ImbalanceDocument7 pagesSt. Paul College Nursing ABG Analysis & Acid-Base ImbalanceCharina AubreyNo ratings yet

- MCQ Pharmacology mbbs Study GuideDocument137 pagesMCQ Pharmacology mbbs Study GuideBlakk FaraciNo ratings yet

- Pediatric Hematology, 3rd Ed. 2006Document2 pagesPediatric Hematology, 3rd Ed. 2006Henny HansengNo ratings yet

- Principles of Animal Physiology Canadian 3rd Edition Moyes Test Bank 1Document342 pagesPrinciples of Animal Physiology Canadian 3rd Edition Moyes Test Bank 1evelyn100% (52)

- PapersDocument12 pagesPapersmahad saleemNo ratings yet

- 2018 ACC-AHA-HRS Guideline On The Evaluation and Management of Patients With Bradicardia y Trastornos de La Conduccion CardiacaDocument181 pages2018 ACC-AHA-HRS Guideline On The Evaluation and Management of Patients With Bradicardia y Trastornos de La Conduccion CardiacaDra. Maclo Salido R1MFNo ratings yet

- Medical Conditions and High-Altitude Travel Luks Et Al NEJM 2022Document10 pagesMedical Conditions and High-Altitude Travel Luks Et Al NEJM 2022Juan Francisco RivoltaNo ratings yet

- Respiratory Distress Syndrome (Hyaline Membrane Disease)Document98 pagesRespiratory Distress Syndrome (Hyaline Membrane Disease)Miraf MesfinNo ratings yet

- Bag Technique DefinitionDocument12 pagesBag Technique DefinitionFrank CaculbaNo ratings yet

- Autonomic Nervus System: Dr. Meida Sofyana, MbiomedDocument26 pagesAutonomic Nervus System: Dr. Meida Sofyana, MbiomedAyu Tiara FitriNo ratings yet

- A Case Presentation On Acute Coronary Syndrome and Myocardial InfarctionDocument55 pagesA Case Presentation On Acute Coronary Syndrome and Myocardial InfarctionAsniah Hadjiadatu AbdullahNo ratings yet

- PROTOCOL of Management of Critical CasesDocument131 pagesPROTOCOL of Management of Critical Casesaziz.shokry.mosaNo ratings yet

- CH 13 Cardiovascular System Lecture - ACCESS - EDITSDocument73 pagesCH 13 Cardiovascular System Lecture - ACCESS - EDITSVarel JoanNo ratings yet

- Rem SleepDocument3 pagesRem SleepAbhisek RoyNo ratings yet