Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Cash Waqfs of Bursa, 1555-1823 Author(s) : Murat Çizakça Source: Journal of The Economic and Social History of The Orient, 1995, Vol. 38, No. 3, The Waqf (1995), Pp. 313-354 Published By: Brill

Uploaded by

Lejla ČauševićOriginal Description:

Original Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Cash Waqfs of Bursa, 1555-1823 Author(s) : Murat Çizakça Source: Journal of The Economic and Social History of The Orient, 1995, Vol. 38, No. 3, The Waqf (1995), Pp. 313-354 Published By: Brill

Uploaded by

Lejla ČauševićCopyright:

Available Formats

Cash Waqfs of Bursa, 1555-1823

Author(s): Murat Çizakça

Source: Journal of the Economic and Social History of the Orient , 1995, Vol. 38, No. 3,

The Waqf (1995), pp. 313-354

Published by: Brill

Stable URL: https://www.jstor.org/stable/3632481

JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide

range of content in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and

facilitate new forms of scholarship. For more information about JSTOR, please contact support@jstor.org.

Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of the Terms & Conditions of Use, available at

https://about.jstor.org/terms

Brill is collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve and extend access to Journal of the

Economic and Social History of the Orient

This content downloaded from

188.252.198.194 on Sat, 16 Jan 2021 23:56:52 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

CASH WAQFS OF BURSA, 1555-1823

BY

MURAT QIZAKQA*)

Bogazigi University, Istanbul

Abstract

By organizing as well as financing expenditures on education, health, welfare and a host

of other activities, cash endowments played a vitally important role in the Ottoman social

fabric and did so without any cost to the state. This article aims at analyzing the way these

endowments functioned and contributed to the society over the long term, covering almost

three hundred years.

1 Introduction

The cash waqf (plural: awqaf) was a trust fund established with money to

promote services to mankind in the name of God. These endowments were

approved by the Ottoman courts as early as the beginning of the fifteenth

century and by the end of the sixteenth, they had reportedly become

extremely popular all over Anatolia and the European provinces of the

empire.

The extent of the geographical diffusion and, specifically, the creation of

waqfs in the Arab provinces, is subject to debate. Originally, it was argued

that the more pious Arab regions refused to have anything to do with this

institution'). This view has been challenged. The widespread establishment

of these waqfs in Aleppo has been documented2) and it is possible that new

research may reveal further examples in other Arab cities.

The endowed capital of the waqf was "transferred" to borrowers who

after a certain period, usually a year, returned to the waqf the principal plus

a certain "extra" amount, which was then spent for all sorts of pious or

social purposes. These vague terms "transferred" and "extra" have been

used deliberately here. For, whether the capital of the endowment was lent

as credit to the borrowers and the return was in fact nothing but the

ordinary interest constitutes another debate.

*) The author is grateful to professors Ahmet Davutoglu. Ethem Eldem, Suraiya Faroqhl,

Mehmet Geng, and Harriet Zurndorfer for their comments, as well as to his assistants Mefail

Hlzhli, Ahmet $eyhun, Asim Yediylldiz and particularly to Fehmi Yilmaz for their valuable

assistance and to Kubilay Dolgun for the computer work. While he is grateful to all of them,

he, alone, is responsible for any mistakes.

1) Mandaville, 1979, p. 308

2) Masters, 1988, p. 162.

? E. J Brill, Leiden, 1995 JESHO 38,3

This content downloaded from

188.252.198.194 on Sat, 16 Jan 2021 23:56:52 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

314 MURAT CIZAKCA

In a society where health, educat

by gifts and endowments, the cash

very survival of the Ottoman so

major Injections of capital to th

tioned.

2. The Legal Background

A. Position of the Classical Jurists

The Ottomans, being devoted Hanefis, conducted their business and

social affairs within the general guide lines established by this school of

thought. It is, therefore, imperative that this analysis should start with a

summary of the classical Hanefi position pertaining to cash waqfs. Let us first

consider the thorny issue of the endowment of moveable assets. The essence

of this problem pertains to the perpetuity of the endowment, the sine qua non

condition for any waqf. Real estate, was thought to be the best asset to

ensure the perpetuity of an endowment. There were, however, three recog-

nized exceptions to this general principle among the Hanefi scholars: first,

the endowment of moveable assets belonging to an endowed real estate,

such as, oxen or sheep of a farm, was permitted; second, if there was a per-

tinent hadis, and third, if the endowment of moveables was the customary

practice, ta'amul, in a particular region. Indeed, exercising judicial

preference, estihsan, Imam Muhammad al-Shaybani had ruled that even in

the absence of a pertinent hadis the endowment of a moveable asset was per-

missible if this was customary practice in a particular location').

Apparently, even custom was not always a required condition, for accord-

ing to al-Sarahsi, Imam Muhammed had, in practice, approved the endow-

ment of moveables even in the absence of custom4). Furthermore, both

Imams Muhammed al-Shaybanl and Abu Yusuf had confirmed, absolutely,

the endowment of moveables attached to a piece of real estate. In view of

this, it is not surprising that we often see such combined cash/real estate

waqfs in the Ottoman records.

Given the acceptability of moveable assets as the basis for creating a waqf,

how does one define a moveable asset? More specifically, can money be con-

sidered a moveable asset and, therefore, be permitted as the basis for the

establishment of a foundation? Imam Zufer answered this question affir-

3) D6ndiiren, 1990.

4) ibzd.

This content downloaded from

188.252.198.194 on Sat, 16 Jan 2021 23:56:52 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

CASH WAQFS OF BURSA, 1555-1823 315

matively and ruled that the endowment of cash was absolutely pe

Zufer went into detail as to how such an endowment could be

he suggested the endowed cash form the capital base of a mudara

ship and any profit realized be spent in accordance with the gene

of the waqf as stated in its charter If the moveable assets endow

originally in a liquid cash form, then they should be sold in the m

and the cash thus obtained could be utilized as the capital of a

In summary, three principles constituted the foundation upon

later Ottoman jurists built the structure of the cash waqfs: the a

moveables as the basis of a waqf, acceptance of cash as a move

and, therefore, approval of cash endowments.

B Establishment of a Cash Waqf

A further debate in the establishment of Ottoman cash waqf

around the question of the irrevocability (liizum-u vakf). Accordi

Hanife, the founder of a waqf or his descendants could revoke th

decision and claim the endowed property back. That is to say,

not irrevocable. Ebu Hanife added, that for a waqf to become

and valid, a court's decision was necessary

Other great jurists of the Hanefi school did not agree with this

Ebu Yusuf, for instance, argued that when Prophet Mohamm

his property, his personal property rights became null and void.

neither the Prophet nor any of the four chalifs or the follow

Prophet, eshab, ever reversed their decision to endow their prope

scholars further argued that the establishment of a waqf was an

act, based upon the hadis pertaining to Omer's endowment.

This legal debate among the great Hanefi scholars was resolv

Ottomans as follows: a man wishing to establish a waqf informed

of his Intention thereby creating the waqf He later revoked his d

demanded the trustee of the waqf return his capital. When the latt

to do so, the case was brought to the court where the request

rejected by the judge who declared that a waqf, once establis

irevocable and definite (liizum ve katiyyet). Thus the condition de

by Ebu Hanife, i.e., the court's decision, was met and the wa

irrevocable and definite5).

There are many instances of the establishment of cash waqfs no

Bursa court registers. One particular case dated 1087/1676 should

5) Barkan-Ayverdi, 1970, p. XXIII).

This content downloaded from

188.252.198.194 on Sat, 16 Jan 2021 23:56:52 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

316 MURAT CIZAKCA

demonstrate the process described

Mehmed Ali b. Hasan, resident of the

had appointed Hasan Qelebi b. Mehmed

to be established with a rather modest c

was to be loaned to borrowers having sat

an "eleven to ten per annum" basis- (meb

iizere rehnz kavi ve kefil-z malt. istiglal v

The return from this investment was t

quet for the poor Muslims in the "zaviye

ing of every 12th Rebiiilevvel. The 50 Es

trustee. Later the endowment's founder

on the belief that the three imams did not consider the establishment of a

waqf with cash a legal act. The trustee responded that according to Imam-i

Ensari quoting imam-1 Ziifer, the cash waqf was legal (sahih). The two

disputants appealed to the court for an opinion. In his application to the

court, Mehmed Ali b. Hasan stated that since a waqf was not considered

irrevocable by Abu Hanife and, therefore, withdrawal from a decision to

establish a waqf was permitted, he wished to do so and demanded his capital

from the trustee of the waqf. The trustee responded by confirming that,

indeed, Abu Hanife had not considered a waqf as definitely irrevocable

(sihhat liizum ifade etmedigi) but Abu Yusuf, the "second imam" and Al-

Shaybani, the "third imam" had ruled that a waqf was both definite and

irrevocable and therefore he requested the decision of the court upholding

the irrevocability of the waqf. The judge ruled that the waqfwas definite and

irrevocable and that any attempt to abolish the waqf was null and void.

Moreover, the judge ruled, this decision was in agreement with the rulings

of all the "strong imams". This verdict finalized the procedure for the bind-

ing establishment of a cash waqf.

C. The Perpetuity Debate

The establishment of cash waqfs by the Ottomans during the 15th century

appears to have taken place, without legal complications. But during the

next century when these waqfs became so popular that they dominated the

ewqaf system, the military judge of the European provinces, Qivizade,

challenged the situation. His view was almost immediately countered by the

Seyhulislam Abussuud Efendi and a fierce debate began. Since the details

of this debate have already been published, they will not be summarized

here 6). Suffice it to say that the debate between these two great jurists and

6) Mandaville, 1979

This content downloaded from

188.252.198.194 on Sat, 16 Jan 2021 23:56:52 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

CASH WAQFS OF BURSA, 1555-1823 317

their followers lasted for more than a century and it remained i

Supported by the state, cash waqfs continued to exist and flouris

now focus our attention on the paradigm of perpetuity, the mos

in the debate, and seek answers to the following questions:

1 Since, one of the main points of the debate concerned the

perpetuity (proponents arguing that these endowments had

chance for survival as any other real estate endowments, and the

believing that they would collapse within a relatively short time)

be possible now, during the last decade of the 20th century,

retroactively which side of the debate was more true?

2. What factors caused their failure or supported their endurance

words, if these endowments, indeed, had rapidly disappeared,

the reasons behind this failure? Why were they so badly man

contrast, they succeeded in surviving for any length of time, then

the reasons for their relative success?

3. In what way did the cash waqfs contribute to the process of cap

accumulation? This question has to be approached from two perspect

i.e., from the point of view of savers as well as users of funds. Mo

specifically, did the savers pool their resources to form joint cash waqfs

did they add their capital to already existing ones? Did the users of capi

have access to several cahs waqfs so as to enlarge the available pool of cap

at their disposal?

4. In the process of transferring funds to entrepreneurs or to the publi

what extent was the Islamic prohibition of riba observed? In other w

are claims that cash waqfs violated the Islamic law justified')?

3 Cash Waqfs zn Historzcal Reality

A. Survival of the Cash Waqfs

Since perpetuity is considered to be the conditto sine qua non of any w

an analysis of the survival rate of the cash waqfs assumes great importa

Unfortunately, with the exception of the Barkan-Ayverdi study, there

published source that is relevant for this paradigm. Even this well-k

study suffers from two weaknesses: first, it covers a time span of merely

years and is therefore inappropriate for an analysis of perpetuity Se

closely related to the first weakness (since it is based upon an analysis of

three tahrtr registers), the fluctuations in the number of waqfs that sur

7) Barkan-Ayverdi, 1970, passim and Mandaville, 1979, passim).

This content downloaded from

188.252.198.194 on Sat, 16 Jan 2021 23:56:52 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

318 MURAT CIZAKCA

may be misleading. These fluctuat

there may have been more than o

waqf not observed in one regist

missing register

Bearing in mind these shortcomings of the Barkan-Ayverdi study, which

concentrated on the Istanbul waqfs, an attempt has been made in this article

to overcome these two weaknesses by a study of the Bursa cash waqfs. To

start with, the time span has been expanded to cover the period 963-

1239/1555-1823, i.e., a period of 268 years. Secondly, the analysis has been

based upon the individual cash waqf Thus, it has been possible to trace the

performance of a waqf over a long period and note often that a waqf that

seemed to have vanished at a certain point in time could be "re-discovered"

at a later period.

The main source used for this study is the set of registers which may be

called aptly the "vakif tahrir defterleri" or the cash waqf censuses. About

seventy volumes of these registers have been identified among the Bursa

Court Registers Collection. In order to facilitate the research, a sample had

to be made and those registers with approximately 20 years in between were

chosen. The details of these registers are presented below.

Table 1

Cash Waqf Census Registers

Year Source

963/1555 A 68/75

994/1585 A 136/163

1078/1667 B 135/350

1104/1692 B 169/385

1105/1693 B 169/385

1163/1749 B 170/386

1181/1767 B 199/423

1200/1785 B 352/736

1201/1786 B 352/736

1220/1805 B 197/802

1239/1823 B 308/548

Having selected our sam

thoroughly examine the deb

century, Qivizade and Sey

clude, some four hundred

accurate. The question t

This content downloaded from

188.252.198.194 on Sat, 16 Jan 2021 23:56:52 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

CASH WAQFS OF BURSA, 1555-1823 319

registered waqfs were perpetual"? But first, the term "perpetual" mu

defined. For all practical purposes, a perpetual waqf is defined her

which survived for more than a century. Thus, those waqfs which ha

vived for at least one hundred years were sought.

In order to find the answer to the problem of perpetuity, altogeth

cash waqfs were entered into the computer This constituted the

population of the research. Within this total population, however

were 761 individual waqfs which were repeatedly identified across seve

ferent years, hence the much larger total population figure. The main

tion can thus be re-stated; what percentage of these 761 waqf

"perpetual"'

In order to answer this question the entire waqf population was ana

by computer To help the computer identify distinct individual waqfs

decided that district (mahalle) would be the primary research unit

were usually several waqfs in each mahalle and each of the latter was

a separate code. The computer was ordered to arrange first the

population according to the mahalles in alphabetical order and sec

produce a chronological list of the waqfs in each mahalle. Wit

chronological list of district waqfs in hand, it was then a simple matt

search for an individual waqf and count the number of its occurrences

different registers and different years.

One of the greatest difficulties encountered in this research was th

tification of the mahalles. This difficulty became quite serious since th

ding clerks often omitted writing the name of the mahalle in which a w

established. Due to these circumstances, it was inevitable that man

could not be included in the research. Thus, the number of perpetual

observed represents a probable minimum of the total reality. This nu

was 148, that is to say, out of 761 individual waqfs, 148 definitely sur

for more than a century This gives us a "perpetuity percentage" o

It is quite clear that had it been possible to incorporate into the g

population those waqfs which could not be traced to a specific mahalle

percentage would have exceeded 20%.

Given this information, can we then pass ajudgement about the sixt

century debate of perpetuity? In other words, was Abussuud Efendi c

in arguing that cash waqfs had as good a chance as real estate waqfs fo

term survival 8)? Obviously, what has been presented above constitute

the first part of the answer to this question-that at least 20% of t

waqfs survived for more than a century For a complete answer, it

8) Mandaville, 1979, p. 299

This content downloaded from

188.252.198.194 on Sat, 16 Jan 2021 23:56:52 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

320 MURAT CIZAKCA

be necessary to determine the su

research has never been attempted

At this point it may be argued tha

have had a far better chance of sur

Efendi must have been wrong to ar

for survival as the former But th

should not be exaggerated. After all

frequent fires, earthquakes and th

they suffered from inelastic revenu

refused to increase their rents and w

port they enjoyed9). In short, erosi

impediment to the survival of the r

addressed separately.

B. Icareteyn Vakzflarz

When a major disaster struck waqf

work would have to be undertak

expenses would naturally have be

revenues of the endowment. The solution was found in an institution known

as the icareteyn vakzflarz, which may be translated as the "double rent

endowments."

The origin of this institution is subject to debate. Gerber has argued

the classical law manuals are silent about the icareteyn vakflart and tha

endowments were invented during the 16th century. According to Ge

these endowments were incorporated into the Ottoman jurisprudence

year 1020/1611-12, with the promulgation of a new law This law, belo

to the orbid of the state law, kanun, and was not an original Isla

concept10). However, this view is challenged by Akgfindiiz who traces

origin to the so-called wcare-z tavile by which the long term renting

endowment property became possible for the first time as early as the

century The zcare-z tavile, a simple method by which the trustee sign

cessive rent contracts in a single session, was approved by the well

Hanefite jurists Mohammed b. El-Fadl and Calfer El-Hindevani. M

over, the concept of a lump sum payment can also be observed in

writings of these early tenth century jurists 1). That wcare-z tavile ev

9) Akarli, 1987, pp. 227-229

10) Gerber, 1988, pp. 172-4.

11) Akgiindiiz, 1988, pp. 356-7

This content downloaded from

188.252.198.194 on Sat, 16 Jan 2021 23:56:52 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

CASH WAQFS OF BURSA, 1555-1823 321

during the next six centuries into the Ottoman icareteyn vakflarz is

an interesting idea which is supported by Klaus Kreiser Drawing ou

tion to a fifteenth centuryfetwa by Seyhiilislam Molla Giirani and

K6priilhi's work, Krelser has informed us that the concept of doub

was well known during the fifteenth and sixteenth centuries12).

But this evolution did not occur smoothly, and the legality of th

was subject to an Intense debate lasting several centuries b

Ottomans emerged as a world power. The final outcome of the d

that such endowments could be permitted only following the decis

judge and in response to a dire necessity, zaruret. In any case, the p

tion of the 1611-12 law was apparently in response to such a zarure

took the form of a series of fires that caused large scale destructio

waqf property in Istanbul.

The new system was based upon two different types of rents: the

was a large lump sum amount, muaccele, paid promptly to the trus

waqf The second type, miieccele, was the normal annual rent. Acco

afetwa by Abulhay, the muaccele had to be roughly equal to the re

of the waqf property and the relationship between the two rents e

a ratio that varied between 1.30 and 1:112 i"). With the now sub

enhanced revenues of the waqf, the reconstruction work could be c

In order to make rental of a waqf property still attractive to p

tenants, the tenure was lengthened substantially, up to 90 years

Lengthening the tenure to nearly a century created two new p

The first one was the legal problem of circumventing the orthodox

hibition on the long term lease of a waqf. This problem was solved

device, hile-z serzye, which has been explained in detail by Ge

second problem was the more substantial one of confusion and even

of the waqf property over the long run. It goes without saying that

tenure increasing to just under a century, the waqf property

having, in practice, two "owners" which must have led to substa

fusion of property rights. As a result, some real estate waqf prope

have eventually been usurped by the new tenants who rented it as

There is substantial evidence that in Egypt, where the ninety year

was applied, probably, for the first time, this practice led to the e

of pseudo private property14).

12) Kreiser, 1986, p. 221.

13) Kreiser ibid., p. 224.

14) Gibb and Bowen, 1969, vol. I, part II, p. 177

This content downloaded from

188.252.198.194 on Sat, 16 Jan 2021 23:56:52 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

322 MURAT CIZAKCA

Although it is not possible within t

to quantify these arguments, subs

the evolution of the Ottoman wa

status of the person, mutasarrif, w

strictly speaking, when the former

endowment should have been cancel

was permitted. This transfer took th

perty to a third party. Bequeathing

to other relatives was permitted f

such transfers became legal, clearly

tially approached that of private

republican law of endowments, per

property against the payment of a

Until now, we have referred to th

by private individuals. But the grea

the state and need not be repeate

elsewhere 17). All of the above shou

estate waqfs for long term sur

Abussuud Efendi's argumentation

Before moving on to the next topic

vakiflar constituted the origin of th

initiated in the year 1695 and there

during the eighteenth century In t

vakzflarz, tax-farms were auctioned

cele, a large, lump sum payment a

introduced during a period of extre

deficits caused by the long and co

a crucial role in restoring state fina

Concerning the origin of the m

Ottoman financial authorities had

from Egypt "). It has been further

tains to waqf lands20). Thus, it will

as applied in Egypt, constituted the

authorities developed the concept of

15) E. Akarli, 1987, 229; B. Yediyildiz,

16) Hatemi, 1969, p. 81.

17) Cuno, 1992, pp. 21-24, Akarh, 1987

18) Gen?, 1975, passzm.

19) Geng, ibzd., pp. 285-286.

20) Gibb and Bowen, op.czt., p. 177

This content downloaded from

188.252.198.194 on Sat, 16 Jan 2021 23:56:52 UTCUTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

CASH WAQFS OF BURSA, 1555-1823 323

C. The Management of the Cash Waqfs

Having observed the "perpetuity percentage" of the cash w

obvious question to ask at this point is one of management: how w

some twenty percent of the cash waqfs succeeded in surviving for m

a century in the first place? To answer the question we need to take

look at the way these waqfs were managed. More specifically, we w

cerned mainly here with the manner in which the capital of the w

invested by the trustee.

A typical eighteenth century waqf register contains the following

tion: 1 The name of the waqf and the purpose for which it was est

2. The name of the mahalle, district, in which the endowment was r

3 The name of the trustee. 4. The time period covered by the

Original capital of the waqf. 6. Later additions to the capital of

either by individuals or by other waqfs. 7 The balance of the n

thus formed. 8. The return obtained from the Investment of the

capital at the end of the year, the murabaha fi sene-z kamile. 9. Th

for which the annual return was designated, i.e., the expendi

elmesaryf. Finally, in the section known as the zimem, information

borrowers of the endowment capital was given: 10. The names o

rowers. 11. The amount of capital they borrowed. 12. The mahalle

borrowers lived. 13 The religious denomination of the borrowe

their gender. The invaluable wealth of information contained i

census registers stems from the standardized entry of data kept on

of endowments across a time span of nearly three hundred yea

aside the usual changes in the paleography, there are only two dist

discernible between a record kept in the sixteenth century and

eighteenth century; profit was called irad in the former period and

in the latter, and whereas in the earlier period there is no inform

plied about the borrowers, this information is available in the l

the exception of these differences, a sixteenth century waqf census

tains exactly the same type of Information as the one from the ei

century

A typical 18th century cash waqf entry would read like this; mu

mahsulat ve ihracat-z evkaf-z miislimzn bera-z avarzz ve niiziil mahalle-z or

brusa der zaman-z esseyzd halil ag~a el-miitevelli bil vakf el-mezburfi gurre-

el-haram sene 1200 ila gaye-z zilhicce el-serzf ii sene el-merkum, wh

translated, "the account of the revenue and expenditure of th

endowments for the purpose of (assisting) the avarzz and niiziil tax

(residents of the) Orhan Gazi district of the city of Bursa du

This content downloaded from

188.252.198.194 on Sat, 16 Jan 2021 23:56:52 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

324 MURAT CIZAKCA

trusteeship of Esseyid Halil aga, the trus

beginning of the month of Muharrem

of Zilhicce of the same year" 21). Thi

with an initial capital of 2377.5 grus. To

year was added which increased the c

three other waqfs further contributing

tion, 50 grus, was provided by the waqf

of reciting the mevlid. The second one, 8

Hatun, for the same purpose. Finally, t

came from the waqf of Hatim Hatun th

candles for the Orhan Gazi waqf. The to

increased from the original 2377.5 gr

gruq altogether.

This enhanced capital of 2729 gru? w

individuals. These investments generate

fi sene-z kamile, which represented 9 4

of this return of 257.5 grus, altogether

ment of avartz and niiziil taxes, to reci

the trustee and the bookkeeper, an

remaining 171 grus was called the zzyade

ing year to the capital of the endowme

This demonstrates, in brief, how a cas

shell, the endowed capital was distrib

rowers and the return from this invest

purposes. If the return exceeded,

expenses, the remainder was then added

ment the following year. In this brie

which cry out for an explanation. First

the initial capital.

The original capital of an endowmen

either the return of the invested capita

resulting profit was added to the capita

of their revenue to the endowment con

of food to the members of the guild of

the original capital of this endowm

endowments contributed to the capital

grus22). There is no satisfactory expla

21) B. 227/455-1/lb.

22) B. 227/455, p. 2/2b.

This content downloaded from

188.252.198.194 on Sat, 16 Jan 2021 23:56:52 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

CASH WAQFS OF BURSA, 1555-1823 325

phenomenon of the transfer of funds between endowments. Wh

explanation, the increased capital was invested in its entiret

transference to borrowers.

Having observed above that the original capital of the endowment co

be increased either by a reinvestment of the profit generated or by contrib

tions from other endowments, it will be argued here that there must hav

been a relationship between "perpetuity" and enhancement of the init

capital. Put differently, we have the impression that the "perpetual waqfs

owed their survival to the enhancement of their initial capital.

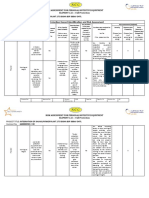

It has been stated above that 148 perpetual waqfs were studied. Of this to

a 25 % sample (36 perpetual waqfs) was created and the relationship betwee

the enhancement of their capital and their perpetuity was examined. T

results of this analysis is presented in Table 2 below Out of these 36 perpet

waqfs only 7, or 19% had not have their initial capital expanded. The

remainder, i.e., 81% of these waqfs had gone through a process of capi

enhancement. Thus our impression that the enhancement of the init

capital appears to have been an important factor in explaining

perpetuity of the endowments was confirmed.

Let us now examine the nature of the return of the invested capital, th

irad or murabaha. Was it based on a certain percentage of the capital inves

i.e., a rate of interest pure and simple or, was it solely the profit generat

by the invested capital? If the former is true, it goes without saying that t

would be in contradiction with the well known Islamic prohibition o

interest. In such a case an explanation concerning how the prohibition

circumvented would be necessary If the latter alternative is correct, i

return equals profit realized, then the return could conceivably entail

only a situation of profit but also a loss thereby causing a potential deplet

of the initial capital as well.

A cash waqf could invest its capital in one of these three methods:

mudaraba 2. bida'a 3 muamele-z 'serzyye. The first two methods are well kno

forms of Islamic finance and need not be explained here. The third expres

sion, on the other hand, is a general terminology covering various method

by which money could be lent to borrowers within the framework of Islam

jurisprudence. While these muamele-z serzye methods were permitted by t

jurists, it seems they were simple legal devices intent on obeying the lette

of the law while violating its spirit.

One of the most popular of these devices was known as istzglal, and

been described as follows:

This content downloaded from

188.252.198.194 on Sat, 16 Jan 2021 23:56:52 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

326 MURAT CIZAKCA

Table 2

Capital Enhancement and Perpetuzty

(a)

H. Year Waqf's Name From other Reinvested

Waqfs Profit

1078 V AVARIZ-I MAH. ABDAL MEHMET 0.00 0.00

1201 V AVARIZ-I MAH. ABDAL MEHMET 100.00 60.50

1239 V AVARIZ-I MAH. ABDAL MEHMET 1915.00 0.00

1078 V AVARIZ-I MAH. AHMET DAI 0.00 0.00

1163 V AVARIZ-I MAH. AHMET DAI 0.00 31.50

1181 V AVARIZ-I MAH. AHMET DAI 0.00 34.00

1201 V AVARIZ-I MAH. AHMET DAI 0.00 644.00

1239 V AVARIZ-I MAH. AHMET DAI 0.00 0.00

1078 V AVARIZ-I MAH. ALACA HIRKA 1530.00 0.00

1105 V AVARIZ-I MAH. ALACA HIRKA 0.00 0.00

1163 V AVARIZ-I MAH. ALACA HIRKA 0.00 21.00

1181 V AVARIZ-I MAH. ALACA HIRKA 0.00 11.00

1200 V AVARIZ-I MAH. ALACA HIRKA 0.00 0.00

1201 V AVARIZ-I MAH. ALACA HIRKA 0.00 0.00

1239 V AVARIZ-I MAH. ALACA HIRKA 535.00 0.00

1104 V MESCID MAH. ALACA HIRKA 0.00 0.00

1105 V MESCID MAH. ALACA HIRKA 0.00 0.00

1239 V MESCID MAH. ALACA HIRKA 0.00 0.00

1078 V AVARIZ-I MAH. ALACA MESCID 140.00 0.00

1104 V AVARIZ-I MAH. ALACA MESCID 0.00 0.00

1105 V AVARIZ-I MAH. ALACA MESCID 0.00 0.00

1201 V AVARIZ-I MAH. ALACA MESCID 440.00 0.00

1239 V AVARIZ-I MAH. ALACA MESCID 1805.00 0.00

963 V MESCID MAH. ALACA MESCID 0.00 0.00

1104 V MESCID MAH. ALACA MESCID 0.00 0.00

1105 V MESCID MAH. ALACA MESCID 0.00 0.00

1239 V MESCID MAH. ALACA MESCID 403.00 0.00

1078 V AVARIZ-I MAH. AHMET PASA 0.00 0.00

1181 V AVARIZ-I MAH. AHMET PASA 0.00 0.00

1200 V AVARIZ-I MAH. AHMET PASA 0.00 0.00

1078 V AVARIZ-I MAH. ALI PASA 90.00 0.00

1078 V AVARIZ-I MAH. ALI PASA 0.00 0.00

1163 V AVARIZ-I MAH. ALI PASA 20.00 0.00

1181 V AVARIZ-I MAH. ALI PASA 20.00 0.00

1201 V AVARIZ-I MAH. ALI PASA 188.00 0.00

1239 V AVARIZ-I MAH. ALI PASA 294.00 77.50

(b)

1078 V MESCID VE AVARIZ-I MAH. ARABLAR 0.00 0.00

1163 V MIHRAB VE AVARIZ MAH. ARABLAR 0.00 0.00

1181 V MIHRAB-I AVARIZ-I MAH. ARABLAR 0.00 16.00

1200 V MUHIMMAT-I MESCID VE AVARIZ MAH. A 103.00 0.00

This content downloaded from

188.252.198.194 on Sat, 16 Jan 2021 23:56:52 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

CASH WAQFS OF BURSA, 1555-1823 327

H. Year Waqf's Name From other Reinvested

Waqfs Profit

1239 V MESCID VE AVARIZ-I MAH. ATTAR HUSAM 0.00 0.00

1104 V MESCID VE AVARIZ-I MAH. ATTAR HUSAM 0.00 0.00

1105 V MESCID VE AVARIZ-I MAH. ATTAR HUSAM 0.00 0.00

1163 V MESCID VE AVARIZ ATTAR HUSAM 10.00 0.00

1239 V MESCID VE AVARIZ-I MAH. ATTAR HUSAM 0.00 0.00

1104 V AVARIZ-I MAH. AYSI BIN FENARI 0.00 0.00

1105 V AVARIZ-I MAH. AYSI BIN FENARI 0.00 0.00

1181 V AVARIZ-I MAH. AYSI BIN FENARI 0.00 8.00

1201 V AVARIZ-I MAH. AYSI BIN FENARI 0.00 0.00

1220 V AVARIZ-I MAH. AYSI BIN FENARI 0.00 0.00

1239 V AVARIZ-I MAH. AYSI BIN FENARI 0.00 0.00

1078 V AVARIZ-I MAH. BASCI IBRAHIM 0.00 0.00

1105 V AVARIZ-I MAH. BASCI IBRAHIM 0.00 0.00

1181 V AVARIZ-I MAH. BASCI ELHAC IBRAHIM 0.00 0.00

1239 V AVARIZ-I MAH. BASCI IBRAHIM 0.00 0.00

1078 V MESCID VE AVARIZ MAH. BILECIK 664.00 0.00

1104 V MESCID-I SERIF VE AVARIZ MAH. BILECIK 0.00

1163 V MIHRAB VE AVARIZ BILECIK 335.00 28.00

1181 V MIHRAB-I AVARIZ-I MAH. BILECIK 0.00 66.00

1201 V MIHRAB VE AVARIZ MAH. BILECIK 0.00 46.00

1239 V MESCID MAH. BILECIK 0.00 0.00

1078 V AVARIZ-I MAH. CAMII KALE 18.00 0.00

1105 V AVARIZ, IMAM.HATM, MUEZZIN CAMII KALE 0.00 0.00

1181 V AVARIZ-I MAH. CAMII KALE 0.00 0.00

1239 V AVARIZ-I MAH. CAMII KALE 290.00 0.00

1078 V AVARIZ VE MESCID MAH. CIRAG BEY 0.00 0.00

1181 V AVARIZ-I MAH. CIRAG BEY 0.00 91.00

1201 V AVARIZ-I CIRAG BEY 179.00 422.50

1239 V AVARIZ-I MAH. CIRAG BEY 0.00 0.00

1105 V MESCID VE SEM VE IMAM MAH. CEKIRGE 0.00 0.00

1239 V MESCID MAH. CEKIRGE 0.00 0.00

1105 V MESCID VE AVARIZ-I MAH. COBAN BEY 0.00 0.00

1163 V MIHRAB VE AVARIZ-I MAH. COBAN BEY 0.00 0.00

1181 V MIHRAB VE AVARIZ MAH. COBAN BEY 0.00 41.50

1239 V MESCID VE AVARIZ MAH. COBAN BEY 0.00 59.00

(c)

1078 V MESCID MAH. CELEBILER 0.00 0.00

1181 V MIHRAB-I MAH. CELEBILER 0.00 0.00

1078 V AVARIZ-I MAH. ELVAN BEY 1810.00 0.00

1163 V AVARIZ-I MAH. ELVAN BEY 0.00 121.00

1201 V AVARIZ-I MAH. ELVAN BEY 0.00 0.00

1104 V AVARIZ-I MAH. EBU SAHME 0.00 0.00

1200 V AVARIZ-I MAH. EBU SAHME 20.00 147.50

1239 V AVARIZ-I MAH. EBU SAHME 2555.00 353.50

This content downloaded from

188.252.198.194 on Sat, 16 Jan 2021 23:56:52 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

328 MURAT CIZAKCA

H. Year Waqf's Name From other Reinvested

Waqfs Profit

1163 V MIHRAB VE AVARIZ MAH. FAZULLAH PASA 395.00 0.00

1200 V MOHIMAT-I MESCID VE AVARIZ MAH. P 80.00 0.00

1239 V MESCID VE AVARIZ-I MAH. FAZULLAH P 900.00 0.00

1078 V AVARIZ-1 MAH. FILBOZ 0.00 0.00

1105 V AVARIZ-I MAH. FILBOZ 0.00 0.00

1181 V AVARIZ-I MAH. FILBOZ 14.00 39.50

1201 V AVARIZ-I MAH. FILBOZ 0.00 0.00

1104 V AVARIZ-I MAH. GAZI HUDAVENDIGAR 0.00 0.00

1105 V AVARIZ-I MAH. GAZI HUDAVENDIGAR 0.00 0.00

1181 V AVARIZ-I MAH. GAZI HUDAVENDIGAR 0.00 7.50

1200 V AVARIZ-I GAZI HUDAVENDIGAR 0.00 100.00

1239 V AVARIZ-I MAH. GAZI HUDAVENDIGAR 1200.00 305.00

1105 V MESCID VE AVARIZ-I MAH. H. MEHMET KARA 0.00 0.00

1163 V MIHRAB VE AVARIZ 0.00 4.50

1239 V MESCID VE AVARIZ-I HOCA MEHMET KARA 0.00 0.00

1105 V AVARIZ-I MAH. HACI SEYFEDDIN 0.00 0.00

1181 V AVARIZ-I MAH. HACI SEYFEDDIN 0.00 0.00

1201 V AVARIZ-I MAH. HACI SEYFEDDIN 0.00 0.00

1239 V AVARIZ-I MAH. HACI SEYFEDDIN 0.00 21.50

1105 V MESCID MAH. HACI SEYFEDDIN 0.00 0.00

1181 V MIHRAB-I MAH. HACI SEYFEDDIN 50.00 18.50

1200 V MIHRAB-I MAH. HACI SEYFEDDIN 0.00 0.00

1201 V MIHRAB-I MAH. HACI SEYFEDDIN 0.00 0.00

1239 V MESCID MAH. HACI SEYFEDDIN 0.00 23.00

1078 V AVARIZ-I MAH. HOCA YUNUS 300.00 0.00

1181 V AVARIZ-I MAH. HOCA YUNUS 0.00 0.00

1239 V AVARIZ-I MAH. HOCA YUNUS 485.00 9.50

(d)

1104 V AVARIZ-I MAH. HACI SUBHI 0.00 0.00

1181 V AVARIZ-I MAH. HACI SUBHI 0.00 0.00

1201 V AVARIZ-I MAH. HACI SUBHI 0.00 0.00

1239 V AVARIZ-I MAH. HACI SUBHI 0.00 17.00

1078 V MESCID VE AVARIZ-I MAH. HOD 750.00 0.00

1181 V MIHRAB-I AVARIZ-I MAH. HOD?? 0.00 0.00

1239 V MESCID VE AVARIZ-I MAH. HOD 0.00 0.00

1104 V MESCID MAH. HOSKADEM MAKRAMAVI 0.00 0.00

1105 V MESCID MAH. HOSKADEM MAKRAMAVI 0.00 0.00

1181 V MIHRAB-I MAH. HOSKADEM MAKRAMAVI 0.00 0.00

1201 V MUHIM.MESC. MAH. HOSKADEM MAKRAMAVI 150.00 0.00

1078 V AVARIZ VE CESME MAH. HACI ISKENDER 0.00 0.00

1181 V AVARIZ-I MAH. HACI ISKENDERO.00 0.00

1078 V AVARIZ-I MAH. HACILAR 117.00 0.00

1104 V AVARIZ-I MAH. HACILAR 0.00 0.00

1163 V AVARIZ-I MAH. HACILAR 0.00 6.00

This content downloaded from

188.252.198.194 on Sat, 16 Jan 2021 23:56:52 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

CASH WAQFS OF BURSA, 1555-1823 329

H. Year Waqf's Name From other Reinvested

Waqfs Profit

1181 V AVARIZ-I MAH. HACILAR 0.00 0.00

1201 V AVARIZ-I MAH. HACILAR 80.00 0.00

1239 V AVARIZ-I MAH. HACILAR 0.00 0.00

963 V MESCID MAH. HACI BABAO.00 0.00

963 V MESCID MAH. HACI BABA 0.00 0.00

1239 V MESCID MAH. HACI BABA 0.00 56.00

1105 V AVARIZ-I MAH. IMARET-I AYSI BEY 0.00 0.00

1181 V AVARIZ-I MAH. IMARET-I AYSI BEY 0.00 4.00

1239 V AVARIZ-I MAH. IMARET-I AYSI BEY 140.00 0.00

1078 V AVARIZ-I MAH. INCIRLICE 0.00 0.00

1105 V AVARIZ-I MAH. INCIRLICE 0.00 0.00

1181 V AVARIZ-I MAH. INCIRLICE 0.00 0.00

1200 V AVARIZ-I MAH. INCIRLICE 0.00 0.00

1078 V MESCID MAH. KAVAKLI 1200.00 0.00

1104 V MESCID MAH. KAVAKLI 0.00 0.00

1105 V MESCID MAH. KAVAKLI 0.00 0.00

1163 V MIHRAB-I MAH. KAVAKLI 0.00 0.00

1181 V V MIHRAB-I MAH. KAVAKLI 0.00 11.50

1201 V MIHRAB-I MAH. KAVAKLI 0.00 134.00

1239 V MESCID MAH. KAVAKLI 0.00 51.50

In 17th century Bursa istzglal des

construed as a sale: the borrowe

estate, supposedly as a sale, but

his debt after one year, the asset

leased the asset to the borrower (

the "rent" which was often exactl

In short, we have here a simple in

as security23).

Thus, through istiglal and othe

waqfs to lend money (on inter

they actually lend money on in

the answer to this question by e

search also shed light upon a

historians and jurists. This deb

which claimed that the cash w

authors were then joined by M

The views of these historians th

thus violated Islamic law becam

23) Gerber, 1988, p. 128.

This content downloaded from

188.252.198.194 on Sat, 16 Jan 2021 23:56:52 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

330 MURAT CIZAKCA

jurists specializing in Islamic law

published in Turkish in a recent b

Istanbul, the historians' views we

methods by which the cash waqfs

had been scrutinized carefully b

legal. More specifically, it was a

by some of the terminology used

for instance, which some historia

or interest, simply meant that

transferred as karz-z hasene, lendi

profit to be earned by the invest

back by the borrower to the waqf.

the borrower was required to mak

cipal plus a share of this profit.

translated as "eleven out of ten",

for every ten dirhems earned by the

should be returned to the waqfP5

The crucial word here is "earn

amount returned to the waqfby t

earned, then this would be a prof

for yet another debate.

Once again, we are in a position

the profit/capital ratios for each

the return of the capital was in t

expect that the profit/capital rati

ing the ever changing amounts of

capital. If the return, however, w

expect to see more or less constan

stant returns to the invested capi

Before we start this analysis, h

between judicial and economic i

exhibit a constant trend and the r

must be remembered that this pe

a judicial one. This is because, as

issue had been resolved centuri

methods of lending which mode

pertain in actual fact to economic

24) Qizakga-Qiller, 1989

25) D6ndiiren, 1990.

This content downloaded from

188.252.198.194 on Sat, 16 Jan 2021 23:56:52 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

CASH WAQFS OF BURSA, 1555-1823 331

was concerned these instruments were permitted and not cat

interest. Most of the Ottoman jurists had no doubts about the

these instruments.

To find an answer to the question of whether the murabaha or irad con-

stituted an economic interest, 1563 waqfs and their respective profit/capit

ratios covering the period 1078-1220/1667-1805 had been entered into t

computer This evaluation constituted a major part of an earlier study26

Only four of these waqfs exhibited significant fluctuations while all the rest

i.e., 1559 of them, produced returns of between 9 and 12 per cent. Thu

we conclude, although the financial Instruments utilized by the cash waqfs

were considered to be legal and approved by the courts, these constant rati

strongly suggest that an economic interest prevailed. The details a

presented below

Table 3

Economic Interest Rates in Bursa

Year Average profit/capital ratio

(economic interest)

963/1555 10.8%

1078/1667 10.8%

1104/1692 10.8%

1105/1693 10.6%

1163/1749 11.5%

1181/1767 11.1%

1200/1785 11.5%

1201/1786 11.0%

1220/1805 11.5%

1239/1823 13.0%

At this point it would

observation. First of all,

in Bursa is diametrically

observed in the West2

should constitute the s

to have existed a secon

conclusion is suggested b

ing among the sarraf i

higher than the Bursa in

26) Qizakga, ISAV, 1993,

27) Clark, 1991, pp. 213, 2

This content downloaded from

188.252.198.194 on Sat, 16 Jan 2021 23:56:52 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

332 MURAT CIZAKCA

sions: first, the cash waqfs were

market interest rate and were n

limit imposed by their founders.

rates of interest prevailing in the

lower rate. Consequently, it would

Bursa cash waqf and to lend the

interest, say, to the sarrafs, bank

We will investigate this speculati

fice to note that evidence from ot

sider, for instance, the forthcomi

has shown that the trustee of a w

poor at 20 or 30% "interest" ther

that only 10% "interest" be cha

attention of the court and the trustee was accused of fraud.

It is possible to find literally thousands of endowment documents, vakjf

names, which impose a maximum level of economzc interest to be charged

Consider the following cases: In the month of Safer, 919/1513, El-H

Sfileyman b. El-Hac (?) endowed 70 000 silver dirhems. Of this, 30 0

dirhems was to be spent for the construction of a school and the remainin

40.000 was to be loaned as muamele-z seryye and zstzglal with 10% ann

murabaha. The revenue thus obtained was to be spent as follows; 3 dirhem

daily wage to the teacher of the school, 1 dirhem to his assistant, 1 dirhem

to the person who recites the Kur'an, and 2 dirhems to the trustee of the

endowment 29).

Another original document found among the Bursa Court Registers 3

informs us that a certain Mfikrime Hatun binti Abdiilhalik had endow

91.000 silver coins issued during the reign of Sultan Selim. This capital wa

to be loaned in muamele-z serzyye and its istirbah was to be ensured. The ann

return, rzbh, was not to exceed or fall below 12.5%. The trustee was h

responsible that in loaning to borrowers, riba, interest, was to be avoid

under all circumstances. Thus, we are informed that a maximum rate w

imposed by the founders of the waqfs themselves and that this rate was l

than the prevailing market rate.

Looking at the situation from a purely economic point of view, it may

suggested that if other institutions, like the sarraf, existed that fully exploi

the high market demand for capital by charging higher rates of interest,

then eventually such institutions would expand at the expense of the c

28) Jennings, title unknown.

29) A 23/25, 61b.

30) A 21/27, 33a, dated 3 Sevval 923/1517

This content downloaded from

188.252.198.194 on Sat, 16 Jan 2021 23:56:52 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

CASH WAQFS OF BURSA, 1555-1823 333

waqfs which due to moral and religious considerations were n

ted to charge beyond a maximum rate. We will have more to

argument when we consider the decline of the cash waqfs.

4. Injection of Capital into the Economy

A. The Trustees as Borrowers

The points just made may be investigated further by a careful an

the borrowers. It has been indicated above that after the year 1

Bursa waqf tahrzr registers contain a section for each waqf that in

about the persons who borrowed the capital of the endowment.

carefully into these sections it should be possible to identify freque

rowers, or those who borrowed regularly from a multitude of endo

These individuals were most likely the ones who borrowed at the lo

offered by the cash waqfs of Bursa and lent this cash at the higher

the sarrafs of Istanbul. The careers of two trustees extending from

to 1200/1785 in the district of Timurtas in Bursa illustrates this po

First of all, we note that these persons had administered as many

different endowments. Thus, it seems, the trusteeship had by

emerged as a distinct profession. Halil Efendi received 69 grus

akges salary, mevacib, annually from these establishments in the y

Eighteen years later, in 1181, he was still managing seven found

the same district and his annual salary had increased to 76 grus

akges. But he was not satisfied by this-he had begun borrowing

very foundations that he administered. The total amount he bor

1181 amounted to 14 grus and was obtained from two different fou

In the year 1200/1785, a certain Ahmet Efendi replaced Hali

mentioned above. This Ahmet Efendi served as the trustee of six ca

in the same Timurtas district. Four of these six endowments were t

as those managed previously by Halil Efendi. Ahmet Efendi earned

of 50.5 grus from these endowments, considerably less than Hal

76 grus, 360 akges. But Ahmet Efendi was a much greater borr

borrowed a total of 79 grus, far in excess of Halil Efendi's 14 gr

four of the endowments he was managing

These two cases give us the impression that not only had tru

emerged as a distinct profession, but also that trustees were em

major borrowers as the eighteenth century progressed. This in

tendency for trustees to borrow is also confirmed by a more

analysis involving a 25% sample for the years 1749-1823 The d

presented below.

This content downloaded from

188.252.198.194 on Sat, 16 Jan 2021 23:56:52 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

334 MURAT CIZAKCA

Table 4

Capztal Borrowed by the Trustees

(25 % Sample)

Year Total Amount Borrowed Amount Borrowed %

Akre Grus by the Trustees

1749 48.247 31.902 1.217 gr. 4

1767 117.084 7.553 gr. 6

1785 30.301 2.771 gr. 9

1823 154.052 15.669 gr. 10

Table 4 reveals that the r

Amount Borrowed", stead

to 10% in 1823, indicating

of the waqf capital.

Table 4 is supported by th

who borrowed capital as a p

Table 5

Number of Trustees Who Borrowed Capital

Year Total Number of Borrowers No. of Trustees %

1749 625 15 2

1767 1623 93 5

1785 395 21 5

1823 714 47 6

Thus, we lea

borrowed c

Tables 4 and

by the trust

Table 6

Credit per Capita Borrowed by the Trustees

Year Number of Borrowers Amount Borrowed Credit per cap.

1749 15 1.217 gr. 81 gr.

1767 93 7.553 gr. 81 gr.

1785 21 2.771 gr. 132 gr.

1823 47 15.669 gr. 333 gr.

This content downloaded from

188.252.198.194 on Sat, 16 Jan 2021 23:56:52 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

CASH WAQFS OF BURSA, 1555-1823 335

Based upon the last three tables, we can now conclude that t

were becoming more and more significant as borrowers. Sinc

trolled the cash waqfs it must have been relatively easy for them

capital from these institutions. The rate at which they borrowed

to have been substantially lower than the prevailing market r

quently, it is argued here that the trustees must have earned

amounts by exploiting the difference between the two rates o

existing in the capital market.

B. Capital Injection

All the information presented above supports the fact that cash

responsible for a large scale injection of capital into the economy

An attempt will be made to quantify this statement.

Table 7 represents, once again, the results of an analysis m

25% random sample. The columns with total figures may reve

tion that is not complete due to the possibility of a loss of registe

ing to the year in consideration. The figures in the first thre

therefore, should be viewed as minimum figures. Columns four t

considerably more important. Column four indicates the aver

of capital that was received by a borrower. Column five indicates

amount increased by 43% from 1163/1749 to 1200/1785. It s

given year, 10 to 12 persons, on average, borrowed from a single

umn six). But some waqfs provided credit to as many as 37 to

within a given year (column seven).

Table 7

Injection of Capital by Cash Waqfs (in grus)

I II III IV V VI VII

Sample Size Total Credit Total No of Credit Change Average Maximum

No of Waqfs Provided (Gr) Borrowers per cap in cpc No of No of

1749-85 Borrowers Borrowers

1749 59 31902 599 53 10 37

1767 154 117084 1662 70 43% 11 42

1785 32 30031 395 76 12 39

If we take 1767 as the y

tion, and multiply 166

number of borrowers f

This content downloaded from

188.252.198.194 on Sat, 16 Jan 2021 23:56:52 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

336 MURAT CIZAKCA

tion of the total number of bor

clude that in a given year durin

thousand persons were provided w

city of Bursa.

To obtain a figure for the tota

should also multiply the credit

by four. This gives us almost h

wonder about the relative signifi

with the data provided by Mehm

cloth press, mukataa-z resm-i menge

tevabii, for the years 1757-1788,

economy of Bursa by the cash wa

amount withdrawn by the state t

But the redistributive function o

the cash injected into the econo

credit to a select group. On t

privileged few was voluntarily re

tion occurred simultaneously. Evi

below

In this context an assessment of the more than six thousand. persons who

were provided with credit needs to be made. Indeed, what does this figure

imply? Unfortunately, a reliable estimation of Bursa's population for the

18th century is not available. The only estimate this author is aware of has

been made by Erder based upon the reports of French travellers. Accord-

ingly, in the early eighteenth century, Bursa had a population of about

50 000 to 65 00032). By the end of the next century this figure had reached

76.00033). Thus, it would be reasonable to argue that for most of the eigh-

teenth century Bursa probably had a population of about 65-70,000 In view

of these numbers, we can conclude that about 8.5% to 9% of the total

population of Bursa resorted to the cash waqfs of the city as a source of

credit.

At this point, however, we must point out another difficulty in

analysis-the repetitiveness of the data. We do not know if these approx-

imately six thousand borrowers were six thousand separate individuals or

if a particular group of people borrowed from a multitude of endowments

in a given year. The answer to this question is important also from another

perspective: capital pooling.

31) Geng, 1975, p. 273.

32) Erder, 1976, p. 60.

33) Cuinet, 1894, vol. IV, p. 120.

This content downloaded from

188.252.198.194 on Sat, 16 Jan 2021 23:56:52 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

CASH WAQFS OF BURSA, 1555-1823 337

In view of the difficulty presented by the Muslim names, in searchi

an answer to this problem, it was necessary to develop a method that

reveal specific information about each one of the more than six th

borrowers. This study was facilitated by the availability of two ad

types of information. the name of the district, mahalle, in which the b

resided and his profession. To facilitate the research further, a sampl

to be taken. This time four of the most popular Turkish names were

Ahmet, Mehmet, Ali and Mustafa. The computer was then ordered

all the Ahmets, together with the names of the endowments from whi

borrowed, the name of the district in which each one lived,

the profession of each one and the amount borrowed by each. The same

process was repeated for each of the other names. As a result, 133

individuals were identified by professions. Leaving aside one interesting

case whereby a mother and a son had borrowed from the same endowment,

it became clear that only one individual, a certain Ali Molla, had borrowed

from two different endowments in the year 1767. This gives us a ratio o

7.5 per thousand. Thus, within the obvious constraints of our sample, it is

concluded that capital pooling was practiced by only 7.5 per thousand of the

borrowers. This gives, as a very rough estimate, the impression that out of

the 6648 borrowers only about fifty were involved in capital pooling. In

view of what has been explained above about the increasing importance of

the trustees as borrowers, it can be argued that most of these fifty borrowers

plausibly belonged to this particular profession. This argument is supported

by a previous study which showed that another profession that would have

been most likely to utilize the cash waqf sources, i.e., the silk sector, rarely

did so. In fact, the ratio Silk Credits/Total Credits never exceeded 3%

during the period 1749-178514).

5 The Social Dimension

In this section we will concentrate on the way the cash waqfs prov

important social services to the society. All the registers analyzed in this

cle contained valuable information about such expenditures. To search

the basic patterns of social spending by the cash waqfs, once again, a 25

sample was created and each item of expenditure revealed by the sam

data was categorized. This process was repeated for each year in the h

that the resulting table would inform us about changing social values of

Ottoman society in Bursa.

34) Qizakra, 1993, p. 722.

This content downloaded from

188.252.198.194 on Sat, 16 Jan 2021 23:56:52 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

338 MURAT CIZAKCA

The first column of Table 8 shows the various

made by the cash waqfs. A brief explanation

Administration: In this category the salaries o

paid by the cash waqfs are included. An item ref

the account fee, is included under administra

accountant's service fee. This item is interestin

in akpes, the Ottoman coin of the classical peri

Education: This item is quite straightforward.

by the endowments to teachers. In passing, it m

was considered to be largely a waqf respons

teacher, muallim, or a professor, miiderrs, to a

with the conditions laid down by the founder o

tion usually stated the salary to be paid to the

pay a lower salary whereas an increase was p

schools, were ranked according to the salary th

employed, increasing the salary meant that

raised35). The increased expenditure was financ

fit of the waqf, assuming it was sufficient for t

extra profits earned by other foundations. T

enhancement of some endowments throu

others-a process documented in Table 2 abov

Food: Many founders wished for food to be pr

ticular district. Some small foundations did

festivities while others offered food daily to an

sion of food was particularly popular among

to do guild member established a waqf, he woul

be provided to the members of his guild.

Family- Some founders wished that the endow

to family members for generations to come.

in the literature as the ehli vakzflar The questi

the foundations were ehli and what percentage

has puzzled researchers for sometime36).

Justice: Some endowments assigned salaries

This item designates such expenditures as well a

known as mahpus ve zindan. The latter pertains

for prisoners.

35) Baltaci, 1976, p. 28.

36) Roded, 1989, p. 62-65.

This content downloaded from

188.252.198.194 on Sat, 16 Jan 2021 23:56:52 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

Table 8

Expenditure Analysts of Cash Waqfs (I)

Expenditure 994/1585 1078/1667 1163/1749 1181/1767 1201/

Category AKQES Akge Grub Akqe G

Administration 16 persons 20 prs 5 prs 57 p

14.396 6634 28 5 4770 107 10.322 207 8085 12

Education 17 persons 15 prs 1 prs 6 prs - 14 prs 2 prs 15

64380 9344 40 435 2825 4734 209

-o 11 prs. 3 prs. 12 prs. - 35 prs. 2 prs 22 pr

Food 7038 9 - 189 5 - 820 5 1660 602

1 prs - - - - - - -

Family540 - - - - -

Justice1180

1 prs -

- prs

-3

1 prs

360 -

Maintenance

12 610 18 757 309 105 492 180 1140 5 180

Miscellaneous 5 persons 66 prs 4 prs 54 prs 2 prs 113 prs 1 prs 69 prs

1.860 7430 5 4135 92 10.100 45 7045

10 persons 16 prs 1 prs - 7 prs 1 prs 6 prs 1 prs 3

9 060 8216 17 - 44 5 404 29 1080

Rent - 8 prs. -1 prs 2 prs 1 prs 2 prs. 5 p

1464 3 340 15 245 5

Religion 27 pe

29 381 69.646 376 4670 791.5 1184 2712 7021

Social (Ams) - - - - - - 5 prs 1 prs 4 pr

- - - 118 1008 37

Tax 30 prs. 7 prs. 23 prs. - 37 prs - 23 p

102558 240 - 10945 - 16955

Trustees 30.674

24 persons 51 prs 11 prs 1 prs 59 prs 4 prs 106 prs 7

32.930 162 241 388 1587 828 6586

Water Works 8 prs 1 prs - 7 prs - 41 prs - 28 pr

4960 40 149 - 506 - 163

Workers - -S-

- - 28

-

prs.

- -

1 prs.

340

8 prs.

1

1 prs.

110

TOTAL 103 persons 372 70 116 prs 242 prs 264 559 1

162 361 270697 1228 13 921 3 394 24 157 8 390 38 114

This content downloaded from

188.252.198.194 on Sat, 16 Jan 2021 23:56:52 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

340 MURAT CIZAKCA

Maintenance: This item includ

maintaining a mosque, a school

cleaning etc., are all grouped un

Miscellaneous: This is just what

in the traditional Ottoman coin, a

Mosque: Expenses specific to

category.

Rent, mukataa-z zemin: This t

mukataalh vakyflar, a rather co

endowments vertically co-exist

belongs to a waqf and the buildin

who also initiates his own endowm

we designate the former as the lo

it is clear that the upper endowm

Table 8 the mukataa-z zemin was

paid by the endowments, this e

Religion: This category encom

functionaries such as the Hafiz, vazz

melek.

Social Services: Here, some municipal services such as the repairs of the

pavements, public baths as well as the payments of alms to the poor of the

district or to the poor attached to a certain zaviye are included.

Tax: Many endowments reserved a substantial part of their outlay for

helping the residents of a certain district towards the payment of their avarzz

ve niizul taxes.

Trustees: The trustees of some foundations were assigned salaries. The

expenses for such salaries are included in this category

Water works: Provision of water, or the repairs of water canals etc., con-

stituted an important expense item for many foundations.

Workers: Some founders reserved a specific annual amount for cleaners,

repairers etc. This way they ensured the proper maintenance of religious or

educational buildings either endowed by themselves or by others.

Columns two to seven contain detailed information about the expenditure

for each of the categories just explained for a specific year. While the second

column is unique in that its expenses are expressed only in the classical

Ottoman coin akCe, the others are split into two sections containing both the

former and the gruzs, a coin modelled after the European Groschen38).

37) Oztfirk, 1983, p. 107

38) Pamuk, 1992.

This content downloaded from

188.252.198.194 on Sat, 16 Jan 2021 23:56:52 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

CASH WAQFS OF BURSA, 1555-1823 341

The rows (categories) are also divided into two sections. The

tion designated as "persons", gives us the number of individua

paid regular salaries, in akCes or in grus, by the waqfs under

category being considered. The lower part shows the total amo

either coin by the waqfs to all individuals included in the particula

At the bottom of the table we have a row reserved for the gran

The upper part of this row gives the total number of Indivi

salaries in all categories by all the waqfs. The lower part, on the o

shows the total amount of salaries paid by all the waqfs to all the

As usual, the wide fluctuations observed in both sections simply r

fact that the original data included in the registers varied In size

to year Consequently, if we are to Interpret this data it is essent

entire Table 8 should be expressed in percentages. This has bee

the outcome can be seen in Table 9.

Table 9 simply converts the data presented in the previous t

percentages. Let us now take each category and interpret it. We star

the expenses of the waqfs earmarked for administration, i.e., the fi

First of all, we note in column one that for the year 994/1585 the

umn is entirely missing. In view of the monetary history of the pe

is quite normal"39). The columns pertaining to later periods contain b

and grus figures.

Row 1/column 1 indicates that in the year 994/1585, 15% of the p

who were paid salaries by the waqfs were in the administration

These individuals however, received only 9% of the 162.361 akfes i.e

expenditure of all the waqfs Included in the sample for that yea

percentages in this table are rounded up). In the following years we

two major trends: beginning with 1163/1749 the akCe figures for th

tage of persons paid stabilize around 40-49 % with a slight tendency

while the grus figures stabilize around 4%. This high percentage for

figures is caused by the fact that the administration category w

always paid in akCes even in the later periods when this particular c

supposed to have disappeared entirely"4). If as Pamuk claims, the ak

indeed, become merely a unit of account, then an explanation

endurance of this coin in waqf registers in such large percentages w

the nineteenth century is needed.

The row denoting education reveals that the percentage of person

education category paid regular salaries by the waqfs, declined subst

39) ibtd., passzm.

40) ibid passim.

This content downloaded from

188.252.198.194 on Sat, 16 Jan 2021 23:56:52 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

Table 9

Expenditure Analysis for Cash Waqfs (II)--The R

Expenditure 994/1585 1078/1667 1163/1749 1181/1767 12

Category Akge Gru? Akqe Gr

Administration % of persons 0.15 - 0.05 0.07 0.49 0.06 0.42 0.0

% of total expenditure 0.09 0.02 Ox.02 0.34 0.03 0.42 0.

Education % of persons 0.16 - 0.04 0.01 - 0.02 - 0.02

% of total expenditure 0.40 0.03 0.03 - 0.01 - 0.03

Food % of persons - - 0.03 0.04 - 0.05 - 0.06 0.0

% of total expenditure - 0.02 0.007 - 0.06 - 0.10

Family% of %total

of persons

expenditure - - 0.003 . . ..-- -

- - 0.002

Justice % of

% of total expenditure persons

- - 0.004 - - - 0.0004 0

Maintenance % of persons 0.04 0. 17 0.21 0.02 0.21 0.008 0.2

% of total expenditure 0.08 "0.07 0.25 0.008 0.14 0.007 0.

Miscellaneous % of persons

% of total expenditure 0.05

0.01 0.03 0.004 - 0.03

0.30 0180.41

0.06

0.0

Mosque %expenditure

% of total of persons 0.10

0.06 - 0.03 0.01 - 0.02

- 0.01 0.040.003

Rent % of persons -? - 0.02 . - 0.004 0.008 Ox.002

% of total expenditure - - 0.05 - 0.0009 0.01 0.0002

Religion % of persons 0.26 - 0.22 0.31 0.02 0.24 0.008 0.28

% of total expenditure 0.18 - 0.26 0.31 0.34 0.23 0.05 0.

Social (Aims) % of persons - - - - - - - 0.009 0.006

% of total expenditure - - - - - - 0.01 0.0

Tax % %of

oftotal

persons - - 0.08

expenditure - - 0.10 - 0.10

0.38 0.20 - 0.0

- 0.32 -

Trustees % of persons 0.23 - 0.14 0.16 0.009 0.24 0.015 0.19

% of total expenditure 0.19 - 0.12 0.13 0.017 0.11 0.06 0

Water Works % of persons - - 0.02 0.01 - 0.03 - 0.07

% of total expenditure - - 0.02 0.03 - 0.04 - 0.0

Workers % of persons - -- - 0.11 0.002 0.05 0

% of total expenditure -. - - - 0.01 0.0001 0.003

TOTAL persons 103 - 372 70 116 242 264 559 1

P I...

expenditure 162.361 - 270697 1228 1

This content downloaded from

188.252.198.194 on Sat, 16 Jan 2021 23:56:52 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

CASH WAQFS OF BURSA, 1555-1823 343

in akCe terms from 16 % to 2 % This decline in the number o

the education sector supported by the waqf system was matched

more dramatic decline in the percentage of the total expenditu

to education. In the year 1585, 40% of the total expenditure i

the cash waqf system was allocated to this sector This perce

reduced dramatically to 7 % almost three hundred years later

1823. Actually, the sharpest decline, from 40% to 3%, appea

occurred between 1585 and 1667. These figures are in akpes. Bu

does not differ much if we look at the grus figures. By the time

begins to be expressed in grus, in the year 1667, the percentage o

expenditure allocated to education has already been reduced to

At the end of the period, in the year 1823, this percentage had b

reduced to 1%. Thus, we conclude that between 1585 and 1823

lost its relative importance within the Bursa cash waqf system su

Why did the inhabitants of Bursa so consistently reduce the

on education? A partial answer may have been provided by Ma

who has informed us that in the year 1715, with two imper

Ahmed III deliberately downgraded the medreses of Bursa and

granted the Istanbul medreses a monopolistic right to select an

Ottoman religious intelligensia41). However, while this d

downgrading may help us explain the situation during the eighte

tury, it is of no use in explaining the even more serious decli

in the earlier period, between 1585 and 1667. The reasons for

decline are not known and call for a separate research.

In sharp contrast to education the food sector appears to hav

a greater importance within the system. Considering first the ak

we note that the percentage of persons supported by the cash wa

from 3% in the year 1667, to 0.9% at the end of the period i

this decline should not mislead us as it may simply reflect the fa

the food sector, unlike the administration sector observed abo

was used less in the later periods. This hypothesis is confirmed

at the more reliable grus figures, which start with 4% in the yea

increase to 6% in 1823 Now, in reviewing the percentage of to

allocated to food by the cash waqfs in the lower section of th

increasing relative importance of this sector becomes more ob

centrating on the more reliable grus figures we note that this per

increased from 0 7 % in 1667 to 20% at the end of the period in 1

education and food appear to have followed diametrically oppo

41) Zilfi, 1988, pp. 60-61.

This content downloaded from

188.252.198.194 on Sat, 16 Jan 2021 23:56:52 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

344 MURAT CIZAKCA

The next row illustrating the ex

families is most revealing. We ha

year 1667. Even that is a negligib

does not contain any information

cussed distinction42) between the

and charitable waqfs, appears t

Indeed, the data tends to reveal

lished in this city were charitabl

to provide a livelihood for the

negligible. But, we will have m

"trustees" category below.

Justice constitutes another cat

among the founders of the cash w

negligible amounts were allocate

Looking first at the akCe figur

involved in maintenance and suppo

and 2 % throughout the period. L

however, we notice a modestly

by the end of the period. In rev

diture allocated to maintenance, an

figures, we note that after an all

declines to 145% where it stays u

The expenditures for the next c

observed administration, were m

This is also confirmed by the akC

stituted some 40% of the total ex

latter never exceeded 3% Why

administration and miscellaneous

is not known.

In the next category the mosque, all the evidence, whether in akCes or

grus, indicates declining trend of both expenditures and the number of p

sons supported by the system.

The very low figures for the rent category indicate that the cash waqfs p

negligible amounts toward rent.

Although tthe next category is simply identified as religion, it basically

consists of salaries paid by the waqfs to persons who fulfilled religious fun

tions. These expenses appear to have followed a cyclical trend over the lon

run. Looking first at the percentage of individuals active in this categ

42) Roded, 1989, pp. 62-65.

This content downloaded from

188.252.198.194 on Sat, 16 Jan 2021 23:56:52 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

CASH WAQFS OF BURSA, 1555-1823 345

who were paid in gru,s, we note a slight decline between 1667

then the ratio increased and eventually reached 38% by

period. Thus, more than a third of all persons supported by t

were in this category A similar story is revealed by the lower

column. The percentage of total expenditures (in akCes) al

category increased steadily from 18% in 1585 to 34% in the y

we observe the maximum. Afterwards, there is a decline to 1

of the period. This percentage is, by the way, equal to what w

with at the beginning of the period. As for the payments in

starts with 31% In 1667 and then continues with minor flu

the end of the period. Based upon this data it can be concl

one third of all the resources of the cash waqf system in Bur

to the "religion" category and that this category malntain

importance throughout the period.

The sample reveals no data on the category of social spending

1767. Nothwithstanding this, we observe an increasing tre

the year 1767 to 7% by the end of the period.

The next category tax, actually comprises avarzz and niizul ta

there was collective responsibility These taxes were appor

the districts, mahalles, and every household was held responsib

ment of these taxes. Consequently, any attempt, no matter h

to relieve the residents of a certain district from this burden must have been

greatly appreciated. Thus, it can be safely argued that a person who

establishes a waqf for this purpose must have enjoyed an instant boost in his

social standing These arguments are confirmed by the enormous

popularity of the avarzz-niizul waqfs among the founders. Looking at the grus

figures beginning with 1667, we note that for more than a century, until

1786, the percentage of the total expenditure allocated to this category was

maintained. But why there was such a dramatic decline between 1786 and

1823, the end of the period, is not known and calls for a separate research.

The next row reveals that throughout the period between 13 % and 24%

of persons receiving salaries from cash waqfs were the trustees themselves.

The percentage of the total expenditure allocated to this category varied

around an arithmetic mean of 12% (in grus) between 1667 and 1823 This

is not a negligible percentage and casts a shadow of doubt upon the earlier

conclusion drawn concerning the hayrz vs. ehli waqfs. It was concluded above

that the number of ehli, family endowments was negligible. But then we

encounter these figures of 24% and 12% pertaining to the trustees. Could

it be that these two categories were linked somehow3 Could it be that the

trustees who were paid such a substantial percentage of the total expen-

This content downloaded from

188.252.198.194 on Sat, 16 Jan 2021 23:56:52 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

346 MURAT CIZAKCA