Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Basics of Opioid Prescribing - Part II: Pain Management and Opioids

Uploaded by

ga_boxOriginal Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Basics of Opioid Prescribing - Part II: Pain Management and Opioids

Uploaded by

ga_boxCopyright:

Available Formats

Pain Management and Opioids

TOPIC 4 SUMMARY

Basics of Opioid

Prescribing — Part II

INTRODUCTION AND GENERAL PRINCIPLES

Managing opioid therapy in a patient with chronic pain comes with a host of clinical

considerations, including making decisions about short-acting versus long-acting opi-

oids; mitigating and managing the risk for misuse, including addiction and overdose;

and deciding when and how to taper the opioid, if necessary.

SHORT-ACTING VS. EXTENDED-RELEASE/LONG-ACTING OPIOIDS

Opioid analgesics can be divided into two groups: short-acting opioids and extended-

release/long-acting (ER/LA) opioids. Overall, the two types of medications have similar

efficacy and are associated with a similar risk for developing misuse. Thus, the decision

of which type to use depends on the individual clinical scenario, with a goal of meeting

the patient’s specific needs and preferences. Indications for these medications as well as

their features and risks are shown in the table on page 2.

Switching from a Short-Acting Opioid to an ER/LA Opioid

Switching from short-acting to ER/LA opioids is simplest if the same opioid molecule

is used, because there is no concern about lack of cross-tolerance, and thus the patient

can transition to the same total daily dose. Often, patients are even able to transi-

tion to a somewhat lower total daily dose, because the extended-release opioid largely

avoids peaks and troughs in drug levels and, as a result, may provide more-stable and

improved analgesia.

If a patient is switched from a short-acting opioid to a different, ER/LA opioid molecule,

the process is the same as when a patient rotates from one ER/LA opioid to another,

given uncertainty about individual responses to the new opioid in terms of both anal-

gesia and adverse effects. For more details about opioid rotation, see Topic 3: Basics of

Opioid Prescribing — Part I.

Topic 4: Basics of Opioid Prescribing — Part II knowledgeplus.nejm.org 1

SHORT-ACTING OPIOIDS ER/LA OPIOIDS

Indications • Intermittent or occasional pain • Severe pain requiring around-the-clock,

long-term relief when other interventions

• Severe pain in opioid-naive patients

have not provided adequate symptom

control

• Should only be used in patients who have

developed opioid tolerance (defined as

taking at least 60 morphine milligram

equivalents [MMEs] daily of a short-acting

opioid for at least one week)

Features • Analgesia typically lasts 3 to 6 hours • More-stable blood levels, resulting in less

fluctuation in analgesia

• Easier to safely titrate for symptom control

• Reduce risk for opioid withdrawal–

• Provide intermittent relief for (a) pain that

mediated pain

is intermittent and for (b) pain that is

persistent but from which a patient seeks

only intermittent relief

• Can provide around-the-clock pain relief

when dosed at appropriately spaced

intervals

Risks • May lead to end-of-dose lapses in pain • May have increased risk of overdose

control, including waking during the night compared with short-acting opioids,

with pain especially when the dose is initiated or

increased. Should therefore be used with

• Frequent dosing for around-the-clock

particular caution in patients with hepatic

analgesia may be disruptive

or renal dysfunction, sleep apnea, or

• Fluctuations in blood levels may result concomitant use of benzodiazepines or

in withdrawal-mediated symptoms in other sedative hypnotics

physically dependent patients, including

• Higher risk of overdose if a patient

increased pain, distress, irritability, or

disrupts the extended-release mechanism,

other symptoms

leading to rapid absorption of a high dose

of opioid

Examples • Codeine • Fentanyl and buprenorphine patches

• Immediate-release formulations of • Methadone

morphine, hydrocodone, hydromorphone,

• Extended-release formulations of the

oxycodone, oxymorphone, tramadol,

short-acting opioids listed to the left

tapentadol, and fentanyl

Topic 4: Basics of Opioid Prescribing — Part II knowledgeplus.nejm.org 2

RISK OF RESPIRATORY DEPRESSION, SEDATION, AND OVERDOSE

One of the major risks associated with opioid use is opioid overdose, characterized

by sedation, respiratory depression, and potentially death. Opioids cause respiratory

depression by depressing the medullary respiratory center, resulting in reductions in

tidal volume, minute ventilation, and responsiveness to carbon dioxide. Therefore,

patients and family should be educated about manifestations of opioid overdose, ways

to prevent overdose, and use of naloxone if overdose is suspected.

Some of the major risk factors for opioid overdose are:

• Concurrent use of sedative medications, including benzodiazepines

• Coexisting mental health or substance use disorder

• Higher doses of opioids (especially >100 MMEs daily)

• Prior opioid overdose

• Use of ER/LA opioid formulations

• Older age (>65)

• Sleep-disordered breathing

In addition, patients are more likely to overdose during initiation of treatment (espe-

cially the first 2 weeks of treatment with ER/LA opioids), with dose increases, and after

incarceration or rehabilitation (because their opioid tolerance has diminished).

Calculating and Managing Risk

The revised Risk Index for Overdose or Severe Opioid-Induced Respiratory Depression

(RIOSORD) is a validated instrument that uses the risk factors above to estimate the risk

for overdose in opioid-treated patients. When an opioid prescription is necessary in a

patient at high calculated risk for respiratory depression, clinicians should:

• Put interventions in place to reduce risk factors

• Prescribe naloxone

• Consider buprenorphine (a partial opioid agonist) as the best opioid option,

given its ceiling effect and therefore lower risk of respiratory depression

Concurrent use of benzodiazepines is seen in 30% of opioid overdoses nationally.

Therefore, when managing anxiety and related disorders in patients taking opioids,

clinicians should consider approaches other than benzodiazepines, such as psycholog-

ical therapies (e.g., cognitive behavioral therapy, acceptance and commitment ther-

apy, mindfulness-based stress reduction) or a carefully dosed nonsedative medication,

such as a selective serotonin-reuptake inhibitor (SSRI) or a serotonin–norepinephrine

reuptake inhibitor (SNRI).

If a benzodiazepine must be added or continued when an opioid is part of a patient’s

therapy, the patient should be counseled on the added risk and instructed to hold medi-

cation doses if sedated and not increase the dose of either medication without consulting

the prescriber.

Topic 4: Basics of Opioid Prescribing — Part II knowledgeplus.nejm.org 3

Sleep-Disordered Breathing

Opioid-induced changes in respiratory function are also seen during sleep. Sleep-

disordered breathing affects up to 70% of patients on chronic opioid therapy and is

often unrecognized. The two types of sleep apnea, described below, may occur together

and compound patient risk.

• Central sleep apnea can occur because opioids reduce the ventilatory response to

carbon dioxide and hypoxemia, which leads to slowing of one’s breathing and

potential apnea. Risk increases with the opioid dose and with concurrent use of

benzodiazepines, alcohol, or other sedative hypnotics.

• Obstructive sleep apnea can occur because of soft-tissue obstruction in the airway

and is more common with but not limited to higher BMIs.

Common signs and symptoms of sleep apnea include poor concentration, daytime

sleepiness, morning headaches, insomnia, nightmares, snoring, depression, irritability,

mood swings, and difficult-to-control pain related to poor sleep quality.

When sleep apnea is suspected, a sleep study should be performed and medications

adjusted to improve safety.

MONITORING AND MANAGING PSYCHIATRIC COMORBIDITIES IN

CHRONIC PAIN

Chronic pain often leads to increased stress, depression, and anxiety, and preexisting

depression and anxiety are risk factors for the development of chronic pain. Thus, cli-

nicians should screen all patients with chronic pain for psychiatric comorbidities using

a brief, validated assessment tool (see Tools for Clinical Practice below). Effectively

addressing such comorbidities can often reduce the experience of pain.

If a mood disorder is present:

• Engage the patient in counseling aimed at both mood management and self-

management of pain.

• Consider antidepressant therapy, but be aware of drug–drug interactions.

– Serotonin syndrome may occur when opioids are combined with monoamine

oxidase inhibitors, tricyclic antidepressants, or SNRIs. The risk is greater

with opioids such as tramadol and tapentadol that have nonopioid analgesic

mechanisms involving serotonin or norepinephrine reuptake inhibition.

– Some antidepressants inhibit metabolism through certain cytochrome P-450

pathways, thus increasing blood levels of opioids that utilize these pathways

for elimination.

MONITORING FOR UNSAFE OPIOID USE

When opioid therapy is prescribed, a strict plan should be put into place to monitor for

unsafe opioid use, including misuse and diversion. Key monitoring tools include pill

Topic 4: Basics of Opioid Prescribing — Part II knowledgeplus.nejm.org 4

counts, urine drug testing, and reports from the state’s prescription drug monitoring

program (PDMP). Pill counts involve asking the patient to bring their opioid into the

office, and the number of pills is counted and compared with the expected number of

pills based on the prescribed amount. Urine drug testing is discussed in further detail

in Topic 5: Complex Situations in Opioid Prescribing.

Prescription Drug Monitoring Programs

PDMPs are online systems of searchable information about controlled-substance pre-

scription fills, including the location and date of the fill, the names of the prescriber

and recipient, and the dose and quantity of medications.

States vary in whether they require clinicians to consult PDMPs before prescribing and

at what interval. In addition, some states require reporting of buprenorphine for treat-

ment of opioid use disorder (OUD) within an opioid treatment program and some do

not; methadone used in an opioid treatment program is not reported to PDMPs.

Information of potential concern in a PDMP report may include:

• Multiple concurrent opioid prescriptions

• Prescriptions from different prescribers

• Early refills

• Potentially dangerous drug combinations (e.g., involving opioids,

benzodiazepines, stimulants, and muscle relaxants)

• Filling of opioid prescriptions at unexpected or multiple pharmacies

• Payment for opioid prescriptions with cash rather than through insurance

coverage (if insured)

Next Steps Following Signs of Potential Misuse

When worrisome behavior is noted, clinicians sometimes respond by abruptly discon-

tinuing opioids for that patient, but this may in turn be associated with a transition to

illicit opioids and an increased risk of overdose. Therefore, it is preferable to discuss

findings suggestive of misuse with the patient and, if concerns persist, with other care

providers or significant others who may be able to shed light on the concerns.

The clinician should also assess whether the patient has OUD. The care plan should

be revised as appropriate to both meet the patient’s clinical needs and assure safety; if

OUD is diagnosed, this may include offering or facilitating appropriate treatment and

tapering of opioids.

TAPERING OF OPIOIDS

Tapering of opioids allows a patient to either stop the opioid altogether or to continue

it but at a lower dose. In a patient with physical dependence on opioids, any reduction

in the opioid dose should be done gradually, with a slow taper, to avoid withdrawal

symptoms.

Topic 4: Basics of Opioid Prescribing — Part II knowledgeplus.nejm.org 5

When to Consider a Taper

Tapering may be considered for a variety of reasons:

• Lack of adequate benefit

– Declining function despite pain control

• Presence of opioid-related harms

– Evolution of medical comorbidities that increase opioid-related risks

– Persistent adverse effects from the opioid

– Worrisome opioid-related behaviors; these patients should be assessed for

OUD and considered for transition to opioid agonist treatment for OUD

• Patient desire for a trial off opioids

• Resolution of pain but persistent physical dependence on the opioid

• To determine if a patient with good pain control on stable opioid doses still

requires the opioid

• Suspicion of opioid-induced hyperalgesia

• Unrelenting opioid tolerance without resolution on rotation

Note that many of the reasons to consider a taper of opioids are the same as those for

which clinicians may consider rotation of opioids (i.e., presence of adverse effects or

lack of adequate benefit); thus, clinical judgment must be used to determine the best

course of action for an individual patient. Sometimes initial tapering is appropriate,

but then rotation becomes necessary if elimination of opioids is not successful due to

recurrent pain that is not controlled with other means.

Approaches to Tapering

The best approach to opioid tapering depends on many variables, including the reason

for the taper (i.e., possible harm vs. lack of adequate benefit), opioid doses used, dura-

tion of opioid use, type of pain, and patient preferences.

The ideal taper allows time for the body to adjust to

declining doses of opioid and thus avoid signs and SIGNS AND SYMPTOMS OF

symptoms of withdrawal, which can be associated WITHDRAWAL:

with increased pain and inability to continue the taper

• Increased heart rate

(see box).

• Increased pupil size

Although withdrawal is most common when there is a • Yawning

sudden, >25% drop in the opioid dose, its occurrence • Rhinorrhea or tears in the eyes

is highly variable. In clinical practice, a taper of 10% • Sweating

per month is often used for patients who have been • Restlessness

taking opioid therapy long-term (for many years) for • Arthralgia

chronic pain; a taper of 10% per week is used for • Gastrointestinal disturbances

patients who have been taking opioids for weeks to • Tremor

months. This pacing is consistent with recommenda- • Irritability or anxiety

tions from the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and • Piloerection

Prevention and is generally well tolerated by patients.

Topic 4: Basics of Opioid Prescribing — Part II knowledgeplus.nejm.org 6

In some cases, withdrawal symptoms still occur, and these are often managed with an

alpha2-adrenergic agonist such as lofexidine, clonidine, or tizanidine.

If a more rapid taper is necessary, many patients appear to tolerate an initial reduction

of 20%, followed every 3 to 5 days by a reduction of 10% to 20% of the remaining dose.

Whatever taper schedule is planned, revision should be made as indicated based on

patient response.

Ultra-rapid tapers have been described, some using sedation or anesthesia, but stud-

ies do not support long-term advantages of these tapers compared with more-gradual

tapers, and they engender both risks of withdrawal and complications of sedation when

used.

Of note, tapers are not necessary when diversion is identified by a non–physically depen-

dent person.

Tapering During Pregnancy

Tapering of opioids is generally best avoided during pregnancy given the risk of preg-

nancy loss; however, if tapering must be pursued, the risk of pregnancy loss is lowest

in the second trimester.

Pain Management During a Taper

Some patients with chronic pain may experience a reduction in pain as opioids are

tapered (presumably due to lessening of opioid-induced hyperalgesia); however, many

patients require intensified pain management with nonopioid therapies while tapering.

Approaches may include:

• Physical approaches, such as exercise, physical therapy, massage, thermal

modalities, and movement therapies (yoga, qi gong, stretching)

• Psychological interventions, such as mindfulness, meditation, and therapies such

as cognitive behavioral therapy, acceptance and commitment, and dialectical

behavioral therapies as indicated

• Nonopioid medications as indicated, including acetaminophen or nonsteroidal

antiinflammatory drugs, SNRIs or tricyclic antibiotics, anticonvulsants, or muscle

relaxants such as tizanidine

• Carefully targeted interventionalist procedures

TOOLS FOR CLINICAL PRACTICE

Assessing Depression and Anxiety

• Patient Health Questionnaire (PHQ)-2: A 2-item questionnaire used to screen for

depression; to be followed by the PHQ-9 if positive

• Generalized Anxiety Disorder (GAD)-2: A 2-item questionnaire used to screen for

anxiety

Topic 4: Basics of Opioid Prescribing — Part II knowledgeplus.nejm.org 7

Assessing Withdrawal

• Clinical Opiate Withdrawal Scale (COWS): An 11-item scale scoring the

frequency and severity of withdrawal symptoms

MME Charts and Calculators

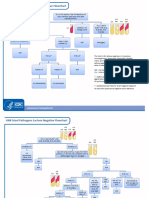

• Calculating Total Daily Dose of Opioids for Safer Dosage (from the U.S.

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention)

• Opioid Conversion Calculator (from Oregon Pain Guidance)

• Opioid Conversion Calculator Morphine Equivalents — Advanced (from

Global RPh)

LEARNING RESOURCES

• Opioid Taper Decision Tool: A 3-page guide from the U.S. Department of

Veterans Affairs that outlines sample taper plans and treatments for specific

withdrawal symptoms

• BRAVO! A Collaborative Approach to Opioid Tapering: A 15-page document

(from Oregon Pain Guidance and Dr. Anna Lembke) outlining a safe and

compassionate strategy to approaching opioid tapering with patients

• BRAVO Overview: A one-page overview of the BRAVO approach to opioid

tapering

• DSM-5 OUD Criteria: A complete list of diagnostic criteria for opioid use

disorder

Last reviewed Mar 2020. Last modified Mar 2020. The information included here is

provided for educational purposes only. It is not intended as a sole source on the subject

matter or as a substitute for the professional judgment of qualified health care professionals.

Users are advised, whenever possible, to confirm the information through additional sources.

© 2020 Massachusetts Medical Society. All rights reserved.

Topic 4: Basics of Opioid Prescribing — Part II knowledgeplus.nejm.org 8

You might also like

- Case Study Attendance Score DisputeDocument3 pagesCase Study Attendance Score DisputeSyed Aamir Ahmed0% (2)

- Text A: Sedation: TextsDocument18 pagesText A: Sedation: TextsKelvin KanengoniNo ratings yet

- Vijaya Diagnostic HIV Test ReportDocument1 pageVijaya Diagnostic HIV Test Reportpasham bharat simha reddy100% (1)

- Urge Surfing HandoutDocument1 pageUrge Surfing HandoutRene McLaughlinNo ratings yet

- B.O. No. 1 S. 2023Document3 pagesB.O. No. 1 S. 2023edvince mickael bagunas sinonNo ratings yet

- Analgesic & Anesthetic: Dr. Yunita Sari Pane, MsiDocument92 pagesAnalgesic & Anesthetic: Dr. Yunita Sari Pane, Msiqori fadillahNo ratings yet

- OpioidsDocument35 pagesOpioidsDr-Mohammad Ali-Fayiz Al TamimiNo ratings yet

- Analgesia & Sedation in ICU: OLEH: HidayatiDocument44 pagesAnalgesia & Sedation in ICU: OLEH: HidayatiZoelNo ratings yet

- Adult Pocket Opioid PrescribingDocument19 pagesAdult Pocket Opioid PrescribingAmisha VastaniNo ratings yet

- Sedation, Analgesia & Patient Controlled Analgesia GuideDocument28 pagesSedation, Analgesia & Patient Controlled Analgesia GuideArshad SyahaliNo ratings yet

- Principles of Opioid Management: Symptom GuidelinesDocument45 pagesPrinciples of Opioid Management: Symptom GuidelinesTheresia Avila KurniaNo ratings yet

- Opioids: Addiction and TreatmentsDocument20 pagesOpioids: Addiction and TreatmentsrinaviadrinririnNo ratings yet

- InsomniaDocument32 pagesInsomniaemanmohamed3444No ratings yet

- Integrated Therapeutics IiiDocument67 pagesIntegrated Therapeutics IiiSalahadinNo ratings yet

- Current Treatment Options in The Management of Severe Pain: William Campbell MD, PHD, Frca, Ffarcsi, FfpmrcaDocument10 pagesCurrent Treatment Options in The Management of Severe Pain: William Campbell MD, PHD, Frca, Ffarcsi, FfpmrcaJonathan TulipNo ratings yet

- Pain Provider AcutePainProviderEducationalGuide IB10998Document28 pagesPain Provider AcutePainProviderEducationalGuide IB10998melawatiNo ratings yet

- Review WHOPainLadder OpioidsandNonOpioidsDocument13 pagesReview WHOPainLadder OpioidsandNonOpioidsamajida fadia rNo ratings yet

- The Key To Freeing Your Life From AddictionDocument22 pagesThe Key To Freeing Your Life From AddictionBrainyBlondieNo ratings yet

- Opiates 2008Document102 pagesOpiates 2008drdavemcdowellNo ratings yet

- Anesthetic DrugsDocument7 pagesAnesthetic DrugsSpahneNo ratings yet

- Presentation 3Document21 pagesPresentation 3AnishaNo ratings yet

- Opiod Analgesics &antagonistsDocument58 pagesOpiod Analgesics &antagonistsVictoria ChepkorirNo ratings yet

- Analgesia 2Document3 pagesAnalgesia 2DanielleNo ratings yet

- Unit 2-CNS and ANS (Part 3) Modified 2021Document30 pagesUnit 2-CNS and ANS (Part 3) Modified 2021Donia ShormanNo ratings yet

- 8-Page Version - HHS Guidance For Dosage Reduction or Discontinuation of OpioidsDocument8 pages8-Page Version - HHS Guidance For Dosage Reduction or Discontinuation of OpioidsAnonymous YsPsAHLNo ratings yet

- Opioid PharmacologyDocument47 pagesOpioid PharmacologyEva K. Al KaryNo ratings yet

- COX-2 Inhibitors: Examples Parecoxib (Dynastat) Celecoxib (Celebrex) Etoricoxib (Arcoxia)Document31 pagesCOX-2 Inhibitors: Examples Parecoxib (Dynastat) Celecoxib (Celebrex) Etoricoxib (Arcoxia)Ben Man JunNo ratings yet

- Conscious Sedation: Hayel Gharaibeh, MD. Anesthesia ConsultantDocument84 pagesConscious Sedation: Hayel Gharaibeh, MD. Anesthesia ConsultantKhaled GharaibehNo ratings yet

- Sedation and Analgesia in ICUDocument22 pagesSedation and Analgesia in ICUmuthu74_inNo ratings yet

- Substance Related DisorderDocument35 pagesSubstance Related Disorderزينب عيسىNo ratings yet

- Opioid Analgesics & AntagonistsDocument13 pagesOpioid Analgesics & AntagonistsVidi IndrawanNo ratings yet

- Opioid Analgesics & AntagonistsDocument13 pagesOpioid Analgesics & AntagonistsafiniherlyanaNo ratings yet

- 6.2 Opioid & Non-OpioidsDocument18 pages6.2 Opioid & Non-OpioidsAsem AlhazmiNo ratings yet

- Conscious sedation techniques and risksDocument84 pagesConscious sedation techniques and risksKhaled GharaibehNo ratings yet

- DruggggggDocument43 pagesDruggggggmonesabiancaNo ratings yet

- Nursing-Process-Focus-Drug-Study-Template special areaDocument8 pagesNursing-Process-Focus-Drug-Study-Template special areaRose RanadaNo ratings yet

- DR Tommy - Cancer PainDocument60 pagesDR Tommy - Cancer PainrisalbaluNo ratings yet

- Management of Seizures in Palliative Care: Journal ClubDocument63 pagesManagement of Seizures in Palliative Care: Journal ClubleungsukhingNo ratings yet

- Opioid Pharmacology: How To Choose and How To UseDocument39 pagesOpioid Pharmacology: How To Choose and How To UseUtibeNo ratings yet

- 1PainAssessment - Pharmokinetics - 2018 Jeannies EditDocument54 pages1PainAssessment - Pharmokinetics - 2018 Jeannies EditApostolos T.No ratings yet

- Acute Post-Op Pain ManagementDocument4 pagesAcute Post-Op Pain Management1234chocoNo ratings yet

- AnalgesicDocument62 pagesAnalgesicAnjum IslamNo ratings yet

- AnalgesicsDocument50 pagesAnalgesicsDocRNNo ratings yet

- Sedation Reading TestDocument22 pagesSedation Reading TestJyothy AthulNo ratings yet

- (Anes) Pain ModuleDocument2 pages(Anes) Pain Modulealmira.s.mercadoNo ratings yet

- Opioids: Dr. Yuri Clement, Pharmacology Unit, FMSDocument40 pagesOpioids: Dr. Yuri Clement, Pharmacology Unit, FMSUnixa BraunNo ratings yet

- Unit 2 Anesthetic Drugs Pharmacy-IIDocument73 pagesUnit 2 Anesthetic Drugs Pharmacy-IIAsad MirajNo ratings yet

- Symptom Mangement For Shortness of Breath/AnxietyDocument6 pagesSymptom Mangement For Shortness of Breath/AnxietySandra SalterNo ratings yet

- Anxiolytic and Hypnotic DrugsDocument3 pagesAnxiolytic and Hypnotic Drugsskoee dbswjNo ratings yet

- Opioid and Non-Opioid Analgesics in The ICUDocument2 pagesOpioid and Non-Opioid Analgesics in The ICUSanj.etcNo ratings yet

- Sedative Hypnotic PoisoningDocument37 pagesSedative Hypnotic PoisoningDeepa WilliamNo ratings yet

- Analgesic, Sedatives, and Hypnotics: Opioid AnalgesicsDocument10 pagesAnalgesic, Sedatives, and Hypnotics: Opioid Analgesicsqgkfjfn6frNo ratings yet

- Conscious Sedation: A Brief Overview Janette Lafroscia, Rces, Rcis, RcsDocument26 pagesConscious Sedation: A Brief Overview Janette Lafroscia, Rces, Rcis, RcsrnvisNo ratings yet

- Opioid Withdrawal ClinicalKeyDocument14 pagesOpioid Withdrawal ClinicalKeykuldip SinghNo ratings yet

- Drug StudyDocument38 pagesDrug StudyRobie Rosa TabagoyNo ratings yet

- Drugs_Materials_-_Prescription_of_Opioids_2017_AAOMS_White_Paper_Document2 pagesDrugs_Materials_-_Prescription_of_Opioids_2017_AAOMS_White_Paper_Cathleen LiNo ratings yet

- AnalgesicDocument56 pagesAnalgesicMuhammad hilmiNo ratings yet

- Pain Management in Surgical PatientsDocument35 pagesPain Management in Surgical Patientssuleman2009100% (1)

- Fentanyl & CongenersDocument30 pagesFentanyl & Congenersnacimay21No ratings yet

- Indelicato 2002Document5 pagesIndelicato 2002Poly ArenaNo ratings yet

- Tapering Off BuprenorphineDocument12 pagesTapering Off BuprenorphineBranislav KovacevicNo ratings yet

- Managing Pain in Palliative CareDocument45 pagesManaging Pain in Palliative CarecaturprianwariNo ratings yet

- Analgesia and Anesthesia for the Ill or Injured Dog and CatFrom EverandAnalgesia and Anesthesia for the Ill or Injured Dog and CatNo ratings yet

- HTTPS: - Dacemirror - Sci-Hub - TW - Journal-Article - Soares2017 PDFDocument10 pagesHTTPS: - Dacemirror - Sci-Hub - TW - Journal-Article - Soares2017 PDFdarinsafinazNo ratings yet

- Seligman Attributional Style QuestionnaireDocument14 pagesSeligman Attributional Style QuestionnaireAnjali VyasNo ratings yet

- GNR Stool Pathogens Lactose Negative FlowchartDocument2 pagesGNR Stool Pathogens Lactose Negative FlowchartKeithNo ratings yet

- GMLOPS 2023 - 07 Company Rebranding Revised Panel Rates - Apr2023Document3 pagesGMLOPS 2023 - 07 Company Rebranding Revised Panel Rates - Apr2023KOONo ratings yet

- Ecological Systems Theory by Bronfenbrenner: Prepared By: Karen B. Reginaldo Jung PuertoDocument20 pagesEcological Systems Theory by Bronfenbrenner: Prepared By: Karen B. Reginaldo Jung Puertochristian ferrerNo ratings yet

- Vale FormDocument1 pageVale FormRANDY BAOGBOGNo ratings yet

- Nursing Care of The Older Adult in Wellness: Geriatric Nursing AssessmentDocument36 pagesNursing Care of The Older Adult in Wellness: Geriatric Nursing AssessmentRuby Corazon Ediza100% (6)

- DLP Eng3 - q3 Cot 2 Giving Possible Solutions To A ProblemDocument6 pagesDLP Eng3 - q3 Cot 2 Giving Possible Solutions To A ProblemNardita Castro100% (1)

- List of Allianz Efu Network (Panel) Hospitals: Hospital Name Address Telephone # KarachiDocument6 pagesList of Allianz Efu Network (Panel) Hospitals: Hospital Name Address Telephone # KarachiFaizan BasitNo ratings yet

- RX Kianbradleyjowett 20240319 080316 0000Document1 pageRX Kianbradleyjowett 20240319 080316 0000cleofeleighclarkNo ratings yet

- NCM 103 Administering Intramuscular MedicationDocument16 pagesNCM 103 Administering Intramuscular MedicationAdrynnette Cruz-LastimadoNo ratings yet

- Serial KillersDocument25 pagesSerial KillersCarrie Davis Dellinger100% (1)

- Sentence Combining 1 - Copy 1Document2 pagesSentence Combining 1 - Copy 1haneen saqerNo ratings yet

- Thesis Statement For Nickel and DimedDocument8 pagesThesis Statement For Nickel and Dimedafkntwbla100% (2)

- Example Letter of Medical NecessityDocument4 pagesExample Letter of Medical Necessitystarlette.hara100% (1)

- List of Visiting DoctorDocument3 pagesList of Visiting Doctordulal pramanickNo ratings yet

- SOP For Antimicrobial Effectiveness TestingDocument4 pagesSOP For Antimicrobial Effectiveness TestingGencay ErginNo ratings yet

- Centric Relation Registration With Intraoral Central Bearing On Curved vs. Flat Plates With Rim Trays in Edentulous PatientsDocument8 pagesCentric Relation Registration With Intraoral Central Bearing On Curved vs. Flat Plates With Rim Trays in Edentulous PatientsCamila MuñozNo ratings yet

- Abbott PIMA CD4 BR NewDocument2 pagesAbbott PIMA CD4 BR NewangelinaNo ratings yet

- Scheme of WorkDocument26 pagesScheme of WorkLogun Kayode SundayNo ratings yet

- Sub-Adventitial Divestment Technique For Resecting Artery-Involved Pancreatic Cancer: A Retrospective Cohort StudyDocument11 pagesSub-Adventitial Divestment Technique For Resecting Artery-Involved Pancreatic Cancer: A Retrospective Cohort StudyMatias Jurado ChaconNo ratings yet

- English Assignment Direct and Indirect SentencesDocument6 pagesEnglish Assignment Direct and Indirect SentencesSasmita Novalis ArrizqiNo ratings yet

- Approach To Child With Headache: Dr. Vijaya Kumar Chikanbanjar 2nd Year Resident Department of PediatricsDocument49 pagesApproach To Child With Headache: Dr. Vijaya Kumar Chikanbanjar 2nd Year Resident Department of Pediatricsar bindraNo ratings yet

- Turkey's Growing Healthcare Sector Driven by Private ProvidersDocument69 pagesTurkey's Growing Healthcare Sector Driven by Private ProviderssbulenterisNo ratings yet

- Australian VSK 2018 LRDocument13 pagesAustralian VSK 2018 LRmuhamadrafie1975No ratings yet

- Performance Appraisal FormDocument3 pagesPerformance Appraisal FormGautam Dutta100% (1)