Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Ecofeminism and The Eating of Animals

Uploaded by

Megan Nizaguieé Toledano RamirezOriginal Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Ecofeminism and The Eating of Animals

Uploaded by

Megan Nizaguieé Toledano RamirezCopyright:

Available Formats

Hypatia, Inc.

Ecofeminism and the Eating of Animals

Author(s): Carol J. Adams

Source: Hypatia, Vol. 6, No. 1, Ecological Feminism (Spring, 1991), pp. 125-145

Published by: Wiley on behalf of Hypatia, Inc.

Stable URL: http://www.jstor.org/stable/3810037 .

Accessed: 13/06/2014 10:59

Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of the Terms & Conditions of Use, available at .

http://www.jstor.org/page/info/about/policies/terms.jsp

.

JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide range of

content in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and facilitate new forms

of scholarship. For more information about JSTOR, please contact support@jstor.org.

Hypatia, Inc. and Wiley are collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve and extend access to Hypatia.

http://www.jstor.org

This content downloaded from 78.56.45.90 on Fri, 13 Jun 2014 10:59:09 AM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

Ecofeminismandthe

Eatingof Animals1

CAROLJ. ADAMS

In thisessay,I will arguethatcontemporary ecofeministdiscourse,whilepoten-

tiallyadequateto dealwiththeissueof animals,is now inadequatebecauseitfailsto

giveconsistentconceptualplaceto thedominationof animalsas a significantaspect

of thedominationof nature.I will examinesix answersecofeminists couldgivefor

not includinganimalsexplicitlyin ecofeministanalysesand showhow a persistent

patriarchalideologyregardinganimalsas instrumentshas kept the experienceof

animalsfrombeingfully incorporated withinecofeminism.2

Jean: Would you feel raping a woman's all right if it was

happeningto her and not to you?

Barbie:No, I'd feel like it was happeningto me.

Jean:Well, that'show some of us feel aboutanimals.

-1976 conversationaboutfeminismand vegetarianism

Ecofeminismidentifies a series of dualisms:culture/nature;male/female;

self/other;rationality/emotion.Some include humans/animalsin this series.

Accordingto ecofeministtheory,naturehasbeen dominatedbyculture;female

has been dominated by male; emotion has been dominated by rationality;

animals...

Where are animalsin ecofeministtheoryand practice?3

SIx ECOFEMINIST

OPTIONS

Animals are a part of nature. Ecofeminismposits that the domination of

natureis linked to the dominationof women and that both dominationsmust

be eradicated.If animalsarea partof nature,then why arethey not intrinsically

a part of ecofeminist analysis and their freedomfrom being instrumentsof

vol.6, no. 1 (Spring1991)? byCarolJ.Adams

Hypatia

This content downloaded from 78.56.45.90 on Fri, 13 Jun 2014 10:59:09 AM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

126 Hypatia

humansan integralpartof ecofeministtheory?Six answerssuggestthemselves.

I discusseach in turn.

EXPLICITLY

1. ECOFEMINISM THEDOMINATION

CHALLENGES OFANIMALS

A strongcase can be madefor the fact that ecofeminismconfrontsthe issue

of animals'sufferingand incorporatesit into a largercritiqueof the maltreat-

ment of the naturalworld.Considerthe "Nature"issueof Womanof Power:A

Magazineof Feminism,Spirituality, andPolitics(1988). In it we find articleson

animal rights (Newkirk); guidelines for raising children as vegetarians

(Moran);a feminist critiqueof the notion of animal "rights"that arguesthat

the best way to help animals is by adopting broad ecofeminist values

(Salamone); an interview with the coordinatorof a grassrootsanimal rights

organization (Albino); and Alice Walker'smoving description of what it

meansfor a human animalto perceive the beingnessof a nonhuman animal.4

In addition to these articles, a resourcesection lists companies to boycott

because they test their productson animals,identifies cruelty-freeproducts,

and gives the addressesof organizationsthat are vegetarian,antivivisection,

and multi-issue animal advocacy groups. This resource list implicitly an-

nounces that praxisis an importantaspectof ecofeminism.

Or considerone of the earliestanthologieson ecofeminismand one of the

latest.ReclaimtheEarth(1983) containsessaysthat speakto some of the major

formsof environmentaldegradation,such as women'shealth, chemicalplants,

the nuclear age and public health, black ghetto ecology, greening the cities,

and the Chipko movement. The anthology also includes an essayon animal

rights(Benney 1983). The morerecentanthology,Reweavingthe World(1990),

contains an essay proposingthat "ritualand religion themselves might have

been broughtto birthby the necessityof propitiationforthe killingof animals"

(Abbott 1990, 36), as well as MartiKheel'sessaythat exploresthe wayhunting

uses animalsas instrumentsof human (male) self-definition(Kheel 1990).

Still other signs of ecofeminism'scommitmentto animals-as beings who

ought not to be used as instruments-can be found. Greta Gaard identifies

vegetarianismas one of the qualities of ecofeminist praxis, along with an-

timilitarism,sustainableagriculture,holistic health practices,and maintaining

diversity(Gaard 1989). Ecofeministscarrieda bannerat the 1990 Marchfor

the Animals in Washington, D. C. Ecofeminist caucuses within feminist

organizationshave begun to articulate the issue of animal liberation as an

essentialaspect of their program.The EcofeministTaskForceof the National

Women'sStudiesAssociationrecommendedat the 1990 NWSA meeting that

the CoordinatingCouncil adopta policy that no animalproductsbe servedat

any futureconferences,citing ecological, health, and humane issues.

Such ecofeminist attention to praxis involving the well-being of animals

ought not to be surprising.Ecofeminism'sroots in this countrycan be traced

This content downloaded from 78.56.45.90 on Fri, 13 Jun 2014 10:59:09 AM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

CarolJ. Adams 127

to feminist-vegetariancommunities. CharleneSpretnakidentifiesthree ways

the radical feminist communities of the mid-1970s came to ecofeminism:

throughstudyof political theoryandhistory,throughexposureto nature-based

religion, especially Goddessreligion, and from environmentalism(Spretnak

1990, 5-6). A good example of these communitiesis the Cambridge-Boston

women's community. One of the initial ecofeminist texts-Francoise

d'Eaubonne's1974 book Lefeminismeou la mort-was introducedthat yearto

scores of feminists who took Mary Daly's feminist ethics class at Boston

College. That same year, Sheila Collins's A DifferentHeavenand Earthap-

pearedand wasdiscussedwith interestin this community.Collins saw"racism,

sexism,class exploitation, and ecological destruction"as "interlockingpillars

upon which the structureof patriarchyrests"(Collins 1974, 161). In 1975,

RosemaryRadfordRuether'sNew Woman/NewEarthwas also greeted with

excitement. Ruether linked the ecological crisis with the status of women,

arguingthat the demandsof the women'smovement must be united with the

ecological movement. The genesis of the two book-length ecofeminist texts

that link women and animals can be traced to this community and its

associationwith Daly duringthose years.5

Interviewswith membersof the Cambridge-Bostonwomen'scommunity

reveal a prototypicalecofeminismthat locates animalswithin its analysis.As

one feministsaid:"Animalsand the earthandwomenhave all been objectified

and treatedin the sameway."Another explainedshe was "beginningto bond

with the earth as a sisterand with animalsas subjectsnot to be objectified."

At a conceptual level, this feminist-vegetarianconnection can be seen as

arisingwithin an ecofeministframework.To apprehendthis, considerKaren

Warren's(1987) four minimal conditions of ecofeminism. Appeal to them

indicatesa vegetarianapplicationarticulatedby these activist ecofeministsin

1976 and still viable in the 1990s.

Ecofeminismarguesthat there is an importantconnection between the

dominationof womenandthe dominationof nature.The womenI interviewed

perceivedanimalsto be a partof that dominatednature and saw a similarity

in the status of women and animalsas subjectto the authorityor control of

another,i.e., as subordinate:

Look at the way women have been treated.We've been com-

pletely controlled, raped,not given any credibility,not taken

seriously.It's the same thing with animals.We've completely

mutilatedthem, domesticatedthem. Their cycles, their entire

beingsareconformedto humans'sneeds.That'swhat men have

done to women and the earth.

Since ecofeminism is distinguishedby whether it arises from socialist

feminism,radicalfeminism,or spiritualfeminism,manyof the ecofeministsof

1976 identifiedthemselveswithin these classificationsas they extended them

This content downloaded from 78.56.45.90 on Fri, 13 Jun 2014 10:59:09 AM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

128 Hypatia

to include animals.Socialist feministslinkedmeat eating with capitalistforms

of productionand the classistnatureof meat consumption;spiritualfeminists

emphasized the association of goddess worship, a belief in a matriarchy,

harmony with the environment, and gentleness toward animals; radical

feminists associatedwomen'soppressionand animals'oppression,and some

held the position of "naturefeminists"who see women as naturallymore

sensitive to animals.

The second of Warren'sconditions of ecofeminismis that we must under-

stand the connections between the oppressionof women and the oppression

of nature.To do so we mustcritique"the sortof thinking which sanctionsthe

oppression"(Warren1987, 6), what Warrenidentifiesas patriarchalthinking

allegedlyjustifiedby a "logicof domination"accordingto which "superiority

justifies subordination"(Warren 1987; 1990). The women I interviewed

rejected a "logic of domination" that justifies killing animals: "A truly

gynocentricway of being is being in harmonywith the earth,and in harmony

with yourbody,and obviouslyit doesn'tinclude killing animals."

The testimoniesof the women I interviewedofferan opportunityto develop

a radicalfeministepistemologyby which the intuitiveandexperientialprovide

an importantsourceof knowledgethat servesto challenge the distortionsof

patriarchalideology.Many women discussedtrustingtheir body and learning

fromtheir body.They saw vegetarianismas "anotherextension of looking in

and finding out who I really am and what I like." From this a process of

identificationwith animalsarose.Identificationmeansthat relationshipswith

animalsareredefined;they areno longerinstruments,means to our ends, but

beingswho deserveto live and towardwhom we act respectfullyif not out of

friendship.

Feministsrealizewhat it's like to be exploited. Women as sex

objects, animals as food. Women turned into patriarchal

mothers,cows turnedto milk machines. It'sthe same thing. I

think that innatelywomen aren'tcannibals.I don'teat fleshfor

the same reasonthat I don't eat steel. It'snot in my conscious-

ness anymorethat it could be eaten. Forthe same reasonthat

when I'mhungryI don't startchompingon my own hand.

Another describedthe processof identificationthis way:

The objectifyingof women, the metaphorsof women as pieces

of meat, here'sthis object to be exploitedin a way.I resentthat.

I identifyit with waysthat especiallybeef and chickens also are

reallyexploited.The way they stuffthem and ruin their bodies

all so that they can sell them on the capitalistmarket.That is

disturbingto me in the samewaythat I feel that I am exploited.

This content downloaded from 78.56.45.90 on Fri, 13 Jun 2014 10:59:09 AM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

CarolJ. Adams 129

Fromthis processof identificationwith animals'experiencesas instruments

arisesan ecofeminist argumenton behalf of animals:it is not simply that we

participatein a value hierarchyin which we place humansover animalsand

that we must now accede rights to animals, but that we have failed to

understandwhat it means to be a "being"-the insight that propelledAlice

Walkersome yearslater to describeher recognition of a nonhuman animal's

beingness(see note 4). Becominga vegetarianafterrecognizingand identify-

ing with the beingnessof animalsis a common occurrencedescribedby this

woman in 1976:

When I thought that this was an animalwho lived and walked

and met the day, and had watercome into his eyes, and could

make attachmentsand had affectionsand had dislikes, it dis-

gustedme to think of slaughteringthat animal and cooking it

and eating it.

As women describedanimals, they recognizedthem as ends in themselves

ratherthan simplyas means to others'ends.

The third ecofeminist claim Warrenidentifies is that feminist theory and

practicemustincludean ecologicalperspective.Ecofeminismreflectsa praxis-

based ethics: one's actions reveal one's beliefs. If you believe women are

subordinatedyou will workforourliberation;if youbelieve that nature,among

other things, is dominatedyou will judge personalbehavior accordingto its

potential exploitation of nature.In this regard,FrancesMooreLappe'spower-

ful bookDietfora SmallPlanethadhad a profoundeffect on numerousfeminists

I interviewedbecauseit providedan understandingof the environmentalcosts

of eating animals.One stated:"When I was doing my paperon ecology and

feminism,the idea of women as earth,that men have exploited the earthjust

like they've exploited women and by eating meat you areexploiting earthand

to be a feminist means to not accept the ethics of exploitation."What she

recognizesis that ecofeministsmustaddressthe fact that our meat-advocating

culturehas successfullyseparatedthe consequences of eating animalsfromthe

experienceof eating animals.6

2. THE ENVIRONMENTAL OFEATINGANIMALS

CONSEQUENCES

One of ecofeminism'sattributesis its concern with the consequencesof the

domination of the earth. It recognizesthat the patriarchalphilosophy that

links women and nature has measurable,negative effects that must be iden-

tified and addressed.When we consider the consequences of meat produc-

tion-and the way by which each meat eater is implicated in these

consequences-ecofeminism faces the necessityof takingsides:will it choose

the ecocide and environmentaldisasterassociatedwith eating animalsor the

environmentalwisdomof vegetarianism?7

This content downloaded from 78.56.45.90 on Fri, 13 Jun 2014 10:59:09 AM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

130 Hypatia

The relationship between meat eating and environmental disaster is

measurable.8In fact, advocatesfor a vegetariandiet have createdimagesthat

translatethe environmentalprofligacyof meat productionto the level of the

individual consumer:the average amount of water requireddaily to feed a

person following a vegan diet is 300 gallons; the average amount of water

requireddaily to feed a personfollowingan ovo-lacto-vegetariandiet is 1,200

gallons; but the average amount of water requireddaily to feed a person

followingthe standardUnited States meat-baseddiet is 4,200 gallons.Half of

all waterconsumedin the United States is used in the cropsfed to livestock,

"andincreasinglythat wateris drawnfromundergroundlakes,some of which

are not significantly renewed by rainfall"(Lappe 1982, 10). More than 50

percentof waterpollution can be linked to wastesfromthe livestock industry

(includingmanure,erodedsoil, and synthetic pesticidesand fertilizers).

Besidesdepletingwatersupplies,meatproductionplacesdemandson energy

sources:the 500 caloriesof food energyfromone poundof steakrequires20,000

caloriesof fossilfuel. Sixty percentof our importedoil requirementswouldbe

cut if the U. S. populationswitchedto a vegetariandiet (Hurand Fields1985b,

25).

Vegetarians also point to other aspects of livestock production that

precipitateecocide:cattle areresponsiblefor85 percentof topsoilerosion.Beef

consumptionaccountsfor about5 to 10 percentof the humancontributionto

the greenhouse effect. Among the reasons that our water, soil, and air are

damagedby meatproductionarethe hidden aspectsof raisinganimalsforfood.

Beforewe can eat animals,theymust eat and live and drinkwater (and even

burp).9Producingthe crops to feed animalstaxes the naturalworld.Frances

Moore Lappereportsthat "thevalueof raw materialconsumedto producefood

from livestockis greaterthan the value of all oil, gas, and coal consumedin this

country... . One-third of the value of all raw materials consumed for all

purposesin the United States is consumed in livestock foods" (Lappe 1982,

66). Eighty-sevenpercent of United States agriculturalland is used for live-

stock production(includingpasture,rangeland,and cropland).

Not only is the analysisof consequencesan importantaspectof ecofeminist

thought, but for ecofeministsa failureto considerconsequencesresultsfrom

the dualismsthat characterizepatriarchalculture:consumptionis experienced

separatelyfrom production,and productionis valued over maintenance. By

this I mean that as a resultof the fetishizationof commoditiesassociatedwith

capitalistproduction,we see consumptionas an end in itself, and we do not

consider what have been the means to that end: eating (a dead) chicken is

disassociatedfromthe experienceof blackwomenwho as "lunggunners"must

each hour scrape the insides of 5,000 chickens' cavities and pull out the

recentlyslaughteredchickens'lungs.1?Both women workersand the chickens

themselves are means to the end of consumption,but because consumption

has been disembodied,their oppressionsas workerand consumablebody are

This content downloaded from 78.56.45.90 on Fri, 13 Jun 2014 10:59:09 AM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

CarolJ. Adams 131

invisible. This disembodiedproductionof a tangible product is viewed as a

positive indicationof the economy,but maintenance-those actionsnecessary

to sustainthe environment-is neithermeasurednor valued.Currently,main-

tenance of domestic space or environmental space is not calculated in

economic terms- houseworkis not calculatedin the GrossNational Product

in the United States, nor are the environmentalresourceswe value (Waring

1988). We do not measure the negative environmental effects of raising

animalsto be our food, such as the costs to our topsoil and our groundwater.

Maintenanceof resourcesis sacrificedto "meat"production.

An ethic that links maintenancewith production,that refusesto disembody

the commodityproducedfromthe costs of suchproduction,wouldidentifythe

loss of topsoil, water, and the demandson fossil fuels that meat production

requiresand factorthe costs of maintainingthese aspectsof the naturalworld

into the end product,the meat. It would not enforce a split between main-

tenance and production.The cheapnessof a diet basedon grain-fedterminal

animalsexists because it does not include the cost of depleting the environ-

ment. Not only does the cost of meat not include the loss of topsoil, the

pollution of water,and other environmentaleffects, but price supportsof the

dairyandbeef "industry" meanthat the governmentactivelypreventsthe price

of eating animals from being reflected in the commodity of meat. My tax

money subsidizeswar,but it also subsidizesthe eating of animals.Forinstance,

the estimatedcosts of subsidizingthe meat industrywith water in California

alone is $26 billion annually(Hurand Fields 1985a, 17). If waterused by the

meat industrywere not subsidizedby United States taxpayers,"hamburger"

wouldcost $35 per pound and "beefsteak"wouldbe $89.

The hidden coststo the environmentof meatproductionand the subsidizing

of this production by the government maintain the disembodimentof this

productionprocess.It also meansthat environmentallyconcernedindividuals

are implicated,even if unknowinglyand unwittingly,in this processdespite

theirown disavowalsthroughvegetarianism.Individualtax moniesperpetuate

the cheapnessof animals'bodiesas a food source;consequentlymeateatersare

not requiredto confront the realityof meat production.Tax monies are used

to developgrowthhormoneslike "bovinesomatotropin"to increasecows'milk

productionratherthan to help people learnthe benefitsand tastesof soyfoods

such as soymilk-products that are not ecologicallydestructive.

The problemof seeing maintenanceas productiveoccurson an individual

level as well. Activism is judged productive;maintenance as in cooking,

especially vegetarian cooking, is usually considered time-consuming. "We

don't have time for it- it impedesour activism"protest many feminists in

conversations. By not viewing maintenanceas productive,the fact that the

yearsof one'sactivist life maybe cut shortby relianceon deadanimalsforfood

is not addressed."lThe orderwe place at a restaurantor the purchaseof "meat"

at the meat counteralso sendsthe messagethat maintainingourenvironment

This content downloaded from 78.56.45.90 on Fri, 13 Jun 2014 10:59:09 AM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

132 Hypatia

is not importanteither. A cycle of destructioncontinues on both a personal

and economic-political level for the same reason,the invisible costs of meat

eating.

After conducting the most detailed diet survey in history- the Chinese

Health Project-Dr. T. Colin Campbell concluded that we are basically a

vegetarian species. High consumption of "meat"and dairy products is as-

sociatedwith the riskof chronicillnessessuchascancer,heartdisease,diabetes,

and other diseases.For women, eating animalsand animalsproductsappears

to be especially dangerous.A diet high in animal fats lowers the age of

menstruation-which increases the incidence of cancer of the breast and

reproductiveorganswhile alsoloweringthe ageof fertility(Brody1990;"Leaps

Forward"1990; Mead 1990).

The moment in which I realized that maintenance must be valued as

productivewas while I wascookingvegetarianfood;thus I wasdoing what we

generallyconsider to be maintenance.The problemis to escape from main-

tenance to producethese or any "productive"thoughts.Seeing maintenance

as productive is the other side of recognizingthe ethical importanceof the

consequencesof our actions.

3. THE INVISIBLE

ANIMALMACHINES

A child's puzzle called "Barn"displayschickens wanderingfreely, cows

looking out the barnyarddoor,and smilingpigs frolickingin mud. But this is

not an accuratedepiction of life down on the farm these days. The fissure

betweenimageandrealityis perpetuatedby agribusinessthat does not conduct

its farmingpracticesin this homespunway.Lawsare being passedin various

states that prevent the filming of animalswho are living in intensive farming

situations.(This phrasingis itself representativeof the problemof imageand

reality:"intensivefarmingsituation"usuallymeansimprisonmentin window-

less buildings.)As Peter Singerpoints out, television programsabout animals

focus on animals in the wild rather than animals in the "factoryfarms";

frequentlythe only informationon these "animalmachines"comes frompaid

advertising."The averageviewer mustknow moreaboutthe lives of cheetahs

and sharksthan he or she knows about the lives of chickens or veal calves"

(Singer 1990, 216). The majorityof animalsdominatedby humansno longer

appearto be a partof nature;they aredomesticated,terminalanimalswho are

maintainedin intensive farmingsituationsuntil slaughteredand consumed.

Perhapsas a result,some ecofeministsand most meat eaterssimplydo not see

farmanimalsat all, and thus cannot see them as a partof nature.

It is instructive,then, to remindourselvesof the lives of individualanimals.

Considerthe case of pigs. A breedingsow is viewed, accordingto one meat

companymanager,as "avaluablepiece of machinerywhosefunctionis to pump

out babypigslike a sausagemachine"(Coats 1989,32). Indeed,she does:about

This content downloaded from 78.56.45.90 on Fri, 13 Jun 2014 10:59:09 AM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

CarolJ. Adams 133

100 piglets, averaging"2 1/2 litters a year,and 10 litters in a lifetime"(Coats

1989, 34). Since about 80 million pigs are slaughteredin the United States

yearly,this meansthat at least 3.5 millionpig "mothermachines"arepregnant

twice duringany given year.Forat least ten monthsof each year,the pregnant

and nursing sow will be restricted in movement, unable to walk around.

Though pigs are extremelysocial beings, sows "aregenerallykept isolated in

individualnarrowpens in which they areunableto turnround"(Serpell 1986,

9). She is impregnatedforcefullyeither by physicalrestraintand mountingby

a boar,artificialinsemination,being tetheredto a "raperack"for easy access;

or through "the surgicaltransplantof embryosfrom 'supersows'to ordinary

sows"(Coats 1989, 34).

The now-pregnantsow residesin a deliverycrate about two feet by six feet

(60 cm x 182 cm) (Coats 1989, 36). In this narrowsteel cage, "she is able to

stand up or lie down but is unable to do much else. Despite this, sows appear

to makefrustratedattemptsat nest-building"(Serpell 1986, 7). Prostaglandin

hormone, injected into the sows to induce labor, also "causes an intense

increasein motivation to build a nest" (Fox 1984, 66). After deliveringher

piglets, "she is commonly strappedto the floor with a leather band, or held

down in a lying position by steel bars,to keep her teatscontinuouslyexposed"

(Coats 1989, 39). The newborn piglets are allowed to suckle from their

incarceratedmotherfor anythingfroma few hoursto severalweeks:

In the most intensive systemsthe piglets aregenerallyisolated

within hoursof birthin smallindividualcageswhich arestack-

ed, row upon row, in tiers. ... At 7 to 14 days,the piglets are

moved again to new quarterswhere they are housed in groups

in slightly largercages (Serpell 1986, 8).

Often farmersclip the pigs'tails shortlyafterbirth to avoid the widespread

problemof tail-biting (Fraser1987). It is probablethat tail-bitingresultsfrom

both a monotonousdiet and the pigs'naturaltendencies to root and chew on

objects in their environment.In essence,"thetelos of a hog is the will to root,"

which is frustratedby theirexistencein confinementsheds(Comstock1990,5).

Once onto solid food, the ..."weaners" are grownon in small

groupsin pens until they reach slaughteringweight at around

six to eight months of age. Forease of cleaning, the pens have

concrete or slattedmetalfloors,and no beddingis provided....

Foot deformitiesand lamenessare common in animalsraised

on hard floors without access to softerbedding areas (Serpell

1986, 8-9).

Ninety percent of all pigs are now raisedin indoor,near-dark,windowless

confinement sheds (Mason and Singer 1980, 8), a stressfulexistence that

includes being underfed (Lawrenceet al. 1988) and living in a saunalike

This content downloaded from 78.56.45.90 on Fri, 13 Jun 2014 10:59:09 AM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

134 Hypatia

atmosphere of high humidity (meant to induce lethargy). Porcine stress

syndrome-a form of sudden death likened to human heart attacks-and

mycoplasmicpneumoniaarecommon.Once they are the appropriatesize and

weight, pigs are herdedinto a crowdedlivestock truckand transportedto the

slaughterhouse,where they arekilled.

This informationon the life cycle of these pigsrequiressome sortof response

from each of us, and the sort of responseone has matterson several levels. I

respond on an emotional level with horrorat what each individual pig is

subjected to and sympathizewith each pig, whose extreme sociability is

evidenced by these animals'increasedpopularityas pets (Elson 1990). On an

intellectuallevel I marvelat the languageof automation,factoryfarming,and

high-tech productionthat providesthe vehicle and license for one to fail to

see these animalsas living, feelingbeingswho experiencefrustrationandterror

in the face of their treatment.As a lactatingmother,I empathizewith the sow

whosereproductivefreedomshave been denied and whose nursingexperience

seemsso wretched.As a consumeranda vegetarian,I visualizethis information

when I witnesspeople buyingor eating "ham,""bacon,"or "sausage."

Intensive factoryfarminginvolves the denial of the beingnessof six billion

animals yearly. The impersonalnames bestowed on them-such as food-

producingunit, proteinharvester,computerizedunit in a factoryenvironment,

egg-producingmachine, converting machine, biomachine, crop-proclaim

that they have been removedfromnature.Butthis is no reasonforecofeminism

to fail to reclaimfarmanimalsfromthis oppressivesystem.It merelyexplains

one reasonsome ecofeministsfail to do so.

4. THE SOCIALCONSTRUCTIONOF EDIBLEBODIESAND HUMANS AS

PREDATORS

Ecofeminismat times evidences a confusion about human nature.Are we

predatorsor arewe not? In an attemptto see ourselvesas naturalbeings,some

arguethat humansaresimplypredatorslike someotheranimals.Vegetarianism

is then seen to be unnaturalwhile the camivorismof other animalsis made

paradigmatic.Animal rights is criticized"forit does not understandthat one

speciessupportingor being supportedby anotheris nature'sway of sustaining

life" (Ahlers 1990, 433). The deeper disanalogieswith carnivorousanimals

remainunexaminedbecausethe notion of humansas predatorsis consonant

with the idea that we need to eat meat. In fact, camivorismis true for only

about 20 percent of nonhuman animals.Can we really generalizefrom this

experience and claim to know precisely what "nature'sway" is, or can we

extrapolatethe role of humansaccordingto this paradigm?

Some feministshave arguedthat the eatingof animalsis naturalbecausewe

do not have the herbivore'sdouble stomach or flat grindersand because

chimpanzeeseat meat and regardit as a treat (Kevles 1990). This argument

This content downloaded from 78.56.45.90 on Fri, 13 Jun 2014 10:59:09 AM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

CarolJ. Adams 135

from anatomy involves selective filtering. In fact, all primatesare primarily

herbivorous.Though some chimpanzeeshave been observed eating dead

flesh-at the most, six times in a month-some never eat meat. Dead flesh

constitutesless than 4 percentof chimpanzees'diet;manyeat insects, andthey

do not eat dairyproducts (Barnard1990). Does this sound like the diet of

humanbeings?

Chimpanzees,like most carnivorousanimals,areapparentlyfarbettersuited

to catching animalsthan are human beings. We are much slower than they.

They have long-projectingcanine teeth for tearinghide; all the hominidslost

their long-projectingcanines 3.5 million yearsago, apparentlyto allow more

crushing action consistent with a diet of fruits, leaves, nuts, shoots, and

legumes.If we do manageto get a hold of preyanimalswe cannot ripinto their

skin. It is truethat chimpanzeesact as if meatwerea treat.When humanslived

as foragersand when oil was rare,the flesh of dead animalswas a good source

of calories.It may be that the "treat"aspectof meat has to do with an ability

to recognizedense sourcesof calories.However,we no longerhave a need for

such dense sourcesof caloriesas animalfat, since ourproblemis not lack of fat

but rathertoo much fat.

When the argumentis madethat eating animalsis natural,the presumption

is that we must continue consuminganimalsbecause this is what we require

to survive,to survivein a way consonant with living unimpededby artificial

culturalconstraintsthat depriveus of the experienceof our real selves. The

paradigmof carnivorousanimalsprovidesthe reassurancethat eating animals

is natural.But how do we know what is naturalwhen it comes to eating, both

because of the social construction of reality and the fact that our history

indicatesa very mixed messageabouteating animals?Some did; the majority

did not, at least to any greatdegree.

The argumentaboutwhat is natural-that is, accordingto one meaningof

it, not culturallyconstructed,not artificial,but something that returnsus to

our true selves-appears in a differentcontext that alwaysarousesfeminists'

suspicions.It is often arguedthat women'ssubordinationto men is natural.

This argumentattemptsto deny social realityby appealingto the "natural."

The "natural"predatorargumentignoressocialconstructionas well. Since we

eat corpsesin a way quite differentlyfromany other animals-dismembered,

not freshly killed, not raw, and with other foods present-what makes it

natural?

Meat is a culturalconstructmade to seem naturaland inevitable. By the

time the argument from analogy with carnivorous animals is made, the

individual making such an argumenthas probablyconsumed animals since

beforethe time she or he could talk. Rationalizationsfor consuminganimals

wereprobablyofferedwhen this individualat age fouror five wasdiscomforted

upon discoveringthat meat came fromdead animals.The taste of dead flesh

precededthe rationalizations,andoffereda strongfoundationforbelievingthe

This content downloaded from 78.56.45.90 on Fri, 13 Jun 2014 10:59:09 AM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

136 Hypatia

rationalizationsto be true.And babyboomersface the additionalproblemthat

as they grewup, meat and dairyproductshad been canonizedas two of the four

basic food groups. (This occurred in the 1950s and resulted from active

lobbyingby the dairyand beef industry.At the turnof the centurythere were

twelve basic food groups.)Thus individualshave not only experienced the

gratificationof taste in eating animalsbut may trulybelieve what they have

been told endlessly since childhood-that dead animals are necessary for

humansurvival.The idea that meat eating is naturaldevelops in this context.

Ideologymakes the artifactappearnatural,predestined.In fact, the ideology

itself disappearsbehind the facadethat this is a "food"issue.

We interact with individual animals daily if we eat them. However, this

statement and its implicationsare repositionedso that the animaldisappears

and it is said that we are interactingwith a formof food that has been named

"meat."In The SexualPoliticsof Meat, I call this conceptualprocessin which

the animal disappearsthe structureof the absent referent.Animals in name

and bodyaremadeabsentas animalsformeat to exist. If animalsarealive they

cannot be meat.Thus a deadbodyreplacesthe live animalandanimalsbecome

absentreferents.Without animalstherewouldbe no meat eating, yet they are

absent from the act of eating meat becausethey have been transformedinto

food.

Animals aremadeabsentthroughlanguagethat renamesdeadbodiesbefore

consumersparticipatein eating them. The absentreferentpermitsus to forget

aboutthe animalas an independententity.The roaston the plateis disembodied

fromthe pig who she or he once was.The absentreferentalsoenablesus to resist

effortsto makeanimalspresent,perpetuatinga means-endhierarchy.

The absentreferentresultsfromandreinforcesideologicalcaptivity:patriar-

chal ideologyestablishesthe culturalset of human/animal,createscriteriathat

posit the speciesdifferenceas importantin consideringwho maybe meansand

who maybe ends, and then indoctrinatesus into believing that we need to eat

animals. Simultaneously,the structureof the absent referentkeeps animals

absent fromour understandingof patriarchalideologyand makesus resistant

to having animals made present. This means that we continue to interpret

animalsfrom the perspectiveof human needs and interests:we see them as

usableand consumable.Much of feministdiscourseparticipatesin this struc-

turewhen failing to make animalsvisible.

Ontology recapitulatesideology. In other words, ideology creates what

appearsto be ontological: if women are ontologized as sexual beings (or

rapeable,as some feministsargue),animalsareontologizedas carriersof meat.

In ontologizing women and animalsas objects, our languagesimultaneously

eliminates the fact that someone else is acting as a subject/agent/perpetrator

of violence. SarahHoaglanddemonstrateshow this works:"Johnbeat Mary,"

becomes "Marywas beaten by John," then "Marywas beaten," and finally,

"women beaten," and thus "battered women" (Hoagland 1988, 17-18).

This content downloaded from 78.56.45.90 on Fri, 13 Jun 2014 10:59:09 AM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

CarolJ. Adams 137

Regardingviolence against women and the creation of the term "battered

women," Hoagland observes that "now something men do to women has

become instead something that is a part of women'snature.And we lose

considerationof John entirely."

The notion of the animal'sbodyasedibleoccursin a similarwayandremoves

the agencyof humanswho buydeadanimalsto consumethem:"Someonekills

animalsso that I can eat their corpsesas meat,"becomes "animalsare killed

to be eaten as meat," then "animalsare meat," and finally "meat animals,"

thus "meat."Something we do to animalshas become insteadsomethingthat

is a partof animals'nature,andwe lose considerationof ourrole entirely.When

ecofeminismacknowledgesthat animalsare absent referentsbut that we are

meant to be predators,it still perpetuatesthe ontologizing of animals as

consumablebodies.

5. CAN HUNTINGBERECONCILED ETHICS?

TO ECOFEMINIST

Ecofeminismhas the potential of situatingboth animalsand vegetarianism

within its theory and practice. But should vegetarianismbecome an essential

aspect of ecofeminism?Are some forms of hunting acceptable ecofeminist

alternativesto intensivefarming?To answerthis questionwe need to recognize

that many ecofeminists (e.g., Warren) see the necessity of refusingto ab-

solutize,a position consistentwith a resistanceto authoritarianismandpower-

over.Thus we can find a refusalto categoricallycondemn all killing. Issuesare

situated within their specific environments.I will call this emphasison the

specificover the universala "philosophyof contingency."

An ecofeminist method complementsthis ecofeministphilosophyof con-

tingency-it is the methodofcontextualization.It maybe entirelyappropriate

to refuseto say"All killing is wrong"andpoint to humanexamplesof instances

when killing is acceptable,such as euthanasia,abortion(if abortionis seen as

killing), and the strugglesof colonizedpeople to overthrowtheir oppressors.

Similarly,it is arguedthat the wayin which an animalis killed to be food affects

whether the action of killing and the consumption of the dead animal are

acceptableor not. Killing animalsin a respectfulact of appreciationfor their

sacrifice,this argumentproposes,does not createanimalsas instrumentalities.

Instead,it is argued,this methodof killing animalsis characterizedby relation-

ship and reflectsreciprocitybetween humansand the hunted animals.Essen-

tially,there areno absentreferents.I will call this interpretationof the killing

of animalsthe "relationalhunt."

The issue of method provides a way to critique the argumentfor the

relationalhunt. Butfirstlet us acknowledgethat the relationalhunt'sideologi-

cal premise involves ontologizing animals as edible. The method may be

different-"I kill for myselfan animalI wish to eat as meat"-but neither the

violence of the act nor the end result, meat, is eliminated by this change in

This content downloaded from 78.56.45.90 on Fri, 13 Jun 2014 10:59:09 AM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

138 Hypatia

actorsand method.12As I arguein the precedingsection, the ontologizingof

animalsas edible bodiescreatesthem as instrumentsof humanbeings;animals'

lives arethussubordinatedto the human'sdesireto eat them even thoughthere

is, in general,no need to be eating animals.Ecofeministswho wish to respect

a philosophyof contingencyyet resistthe ontologizingof animalscouldchoose

the alternativeposition of saying "Eatingan animal after a successfulhunt,

like cannibalism in emergency situations, is sometimes necessary,but like

cannibalism, is morally repugnant."This acknowledgesthat eating animal

(includinghuman) flesh may occur at raretimes, but resiststhe ontologizing

of (some) animalsas edible.

Applyingthe methodof contextualizationto the idealof the relationalhunt

revealsinconsistencies.Becauseecofeministtheoryis theoryin process,I offer

these critiquessympathetically.It is never pointed out that this is not how the

majorityof people are obtaining their food from dead animals. Though the

ecofeminist ethic is a contextualizingone, the context describinghow we

relate to animals is not provided.Just as environmentalistsmystifywomen's

oppressionwhen they fail to addressit directly,so ecofeministsmystifyhumans'

relationswith animalswhen they fail to describethem precisely.

Ecofeminismhas not relied on the notion of speciesismto critiquecurrent

treatment of animals, though its condemnation of naturism,explicitly and

implicitly, offers a broadly similar critique. The word speciesismhas been

contaminated in some ecofeminists' eyes by its close association with the

movement that resists it, the animal rights movement, which they view as

perpetuatingpatriarchaldiscourseregardingrights. Animal rights, though,

does recognizethe right of each individualanimalto continue living and this

is its virtue. An anti-naturismpositiondoes not providea similarrecognition;

as a resultthe individualanimalkilled in a hunt can be interpreted"to be in

relationship."In other words, hunting is not seen as inconsistent with an

anti-naturistposition, though it would be judged so from an anti-speciesist

position.

An antinaturist position emphasizesrelationships,not individuals;the

relational hunt is said to be a relationship of reciprocity.But reciprocity

involvesa mutualor cooperativeinterchangeof favorsorprivileges.What does

the animal who dies receive in this exchange?

The experienceof sacrifice?How can the reciprocityof the relationalhunt

be verifiedsince the other partneris both voiceless in termsof humanspeech

and furthermorerendered voiceless through his or her death? Once the

question of the willingnessof the silent and silenced partneris raised,so too

is the connection between the relational hunt and what I will call the

"aggressivehunt." Ostensiblythe relationalhunt is differentfromthe aggres-

sive hunt, which is seen to aggrandizethe hunter'ssense of (male) self rather

than valuing any relationshipwith the hunted animal. Yet we can find in

discussions of the relational hunt and the aggressive hunt a common

This content downloaded from 78.56.45.90 on Fri, 13 Jun 2014 10:59:09 AM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

CarolJ. Adams 139

phenomenon:the eliding of responsibilityor agency.Considerthe aggressive

hunters'bible,Meditations

onHunting.In this book,JoseOrtegay Gassetwrites:

To the sportsmanthe death of the game is not what interests

him; that is not his purpose.What interestshim is everything

that he had to do to achieve that death-that is, the hunt.

Thereforewhat was beforeonly a means to an end is now an

end in itself. Death is essential becausewithout it there is no

authentic hunting:the killing of the animal is the naturalend

of the hunt and that goal of hunting itself;not of the hunter

(1985, 96).

The erasureof the subjectin this passageis fascinating.In the end the hunter

is not reallyresponsiblefor willing the animal'sdeath, just as the stereotypic

battereris presumedto be unable, at some point, to stop battering;it is said

that he loses all agency.In the constructionof the aggressivehunt, we aretold

that the killing takesplace not becausethe hunterwills it but becausethe hunt

itselfrequiresit. This is the batterermodel.In the constructionof the relational

hunt, it is arguedthat at some point the animal willingly gives up his or her

life so that the humanbeing can be sustained.This is the rapistmodel. In each

case the violence is mitigated. In the rapist model, as with uncriminalized

maritalrape, the presumptionis that in entering into the relationshipthe

woman has said one unequivocal yes; so too in the relational hunt it is

presupposedthat the animal espied by the hunter at some point also said a

nonverbalbut equallybinding unequivocalyes. The relationalhunt and the

aggressivehunt simply provide alternative means for erasing agency and

denyingviolation.

I have not as yet discussedthe fact that the relational hunt is based on

ecofeminists'understandingof some Native Americanhunting practicesand

beliefs.Butgiven that manyindigenousculturesexperiencedtheirrelationship

with animalsvery differentlythan we do today,even nonhierarchically,why

do environmentalistsgravitateto illustrationsfromNative Americancultures

that were hunting ratherthan horticulturaland predominantlyvegetarian?

Why not hold up as a counterexampleto ourecocidalculturegatherersocieties

that demonstratehumanscan live happilywithout animals'bodies as food?

Furthermore,what method will allow us to accomplishthe relationalhunt

on any large scale? Can we create as an ideal method one developed in a

sparselypopulatedcontinent and imposeit upon an urbanpopulationthat has

by and large eliminated the wildernessin which Native American cultures

flourished?The wilderness no longer exists to allow for duplication. As

RosemaryRuetherposes the question:"Since there could be no returnto the

unmanagedwilderness,in which humanscompetewith animalsas one species

amongothers,without an enormousreductionof the humanpopulationfrom

its present5.6 billion back to perhapsa million or so, one wonderswhat kind

This content downloaded from 78.56.45.90 on Fri, 13 Jun 2014 10:59:09 AM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

140 Hypatia

of massdestructionof humansis expected to accomplishthis goal?"(Ruether

1990, 19).

The problemwith the relationalhunt is that it is a highly sentimentalized

individualsolution to a corporateproblem:what arewe to do aboutthe eating

of animals?We either see animalsas edible bodies or we do not.13

6. AUTONOMYAND ECOFEMINIST-VEGETARIANISM

As long as animals are culturally constructed as edible, the issue of

vegetarianismwill be seen as a conflict over autonomy(to determineon one's

own what one will eat versusbeing told not to eat animals). The question,

"Whodecidedthat animalsshouldbe food?"remainsunaddressed.Ratherthan

being seen as agents of consciousness,raisinglegitimate issues, ecofeminist-

vegetariansareseen asviolating others'rightsto theirown pleasures.This may

represent the true "daughter'sseduction" in our culture-to believe that

pleasureis apoliticaland to perpetuatea personalizedautonomyderivedfrom

dominance. The way autonomy works in this instance appearsto be: "By

choosing to eat meat, I acquiremy 'I-ness.'If you say I can'teat meat then I

lose my 'I-ness.'"Often the basicpremiseof the supposedgender-neutralityof

autonomy is accepted, leaving both the notion of autonomy and the social

construction of animals unexamined. As a result, animals remain absent

referents.

The ecofeminist-vegetarianresponse to this idea of autonomy is: "Let's

redefine our 'I-ness.'Does it requiredominance of others?Who determined

that meat is food?How do we constitute ourselvesas 'I's'in this world?"

Giving conceptual place to the significanceof individualanimalsrestores

the absentreferent.This ecofeministresponsederivesnot froma rights-based

philosophybut fromone arisingfromrelationshipsthat bringaboutidentifica-

tion and thus solidarity.We must see ourselvesin relationshipwith animals.

To eat animalsis to makeof them instruments;this proclaimsdominanceand

power-over.The subordinationof animalsis not a given but a decisionresulting

froman ideologythat participatesin the verydualismsthat ecofeminismseeks

to eliminate. We achieve autonomy by acting independently of such an

ideology.

Ecofeminism affirmsthat individuals can change, and in changing we

repositionourrelationshipwith the environment.This formof empowerment

is preciselywhat is needed in approachingthe issueof where animalsstandin

our lives. Many connections can be made between our food and our environ-

ment, ourpolitics and ourpersonallives. Essentially,the existence of terminal

animals is paradigmaticof, as well as contributingto the inevitability of, a

terminalearth.

This content downloaded from 78.56.45.90 on Fri, 13 Jun 2014 10:59:09 AM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

CarolJ. Adams 141

NOTES

1. Earlierversionsof this paperwere presentedat two conferences:"Ecofeminism:

The Woman/Earth Connection,"April 1990,DouglassCollege(sponsoredby the Rutgers

School of Law-NewarkandWomen's RightsLawReporter), and"Women's Worlds:Realities

and Choices, FourthInternationalInterdisciplinary Congresson Women,"June 1990,

HunterCollege. Thanks to KarenWarren,Nancy Tuana,MelindaVadas,MartiKheel,

Batya Bauman, Greta Gaard, Tom Regan, Neal Barnard,and Teal Willoughbyfor

assistancein thinkingand writingon this topic.

2. I will defendthese claimsby appealing,in part,to interviewsI conductedin 1976

of morethan seventy vegetariansin the Boston-areawomen'scommunity.These inter-

views are intendedas testimonyto the fact that ecofeminism'stheoreticalpotential,as

well as its history,is clearlyon the side of animals.They also attest to the importanceof

first-personnarrativein (eco)feministtheorybuilding(see Warren1990). Among those

interviewedwereactivistsand writerssuch as JudyNorsigianand WendySanfordof the

BostonWomen'sHealth BookCollective, LisaLeghorn,KateCloud,KarenLindsey,Pat

Hynes,MarySue Henifin, KathyMaio,SusanLeighStarr,and manyothers.

3. My startingpoint in this essayis not that of animalrightstheory,which seeksto

extendto animalsmoralconsiderationsbasedon theirinterests,sentiency,andsimilarity

with humans.My writingis informed by this argument,but my startingpoint here is that

ecofeministsseek to end the perniciouslogic of dominationthat has resultedin the

interconnectedsubordinationof womenandnature.Fromthis startingpoint, I recognize

manyother issuesbesidesthat of animals'subordinationas problematic.In fact, mythesis

arisesbecausethe ecofeministanalysisof naturerequiresa morevocal namingof animals

asa partof that subordinatednature.ThusI amnot patchinganimalsonto an undisturbed

notion of humanrights,butamexaminingthe placeof animalsin the fabricof ecofeminist

ethics-a startingpoint that alreadypresumesthat the exploitationof natureentailsmore

than the exploitationof animals.

My emphasis here is on ideology.An ideology that ontologizes what are called

"terminal"animals as edible bodies precedesthe issuesassociatedwith animal rights

discourseandecofeministtheory.Myattemptis to exposethis ideology,not throughwhat

ecofeministsand environmentalistssee as the animal rightsstrategyof ethical exten-

sionism from humansto some nonhumans,but by exploringthe resultof the human-

animal dualismthat has precipitatedboth the animal rightsmovement as well as the

suspicionsof it amongthose who favora morebiotic wayof framingthe problemof the

oppressionof nature.The problemis thateach time the bioticenvironmentalistdiscourse

is willingto sacrificeindividualanimalsas ediblebodies,it demonstratesthe reasonthat

argumentsfor rightsand interestsof individualanimalshave been so insistentlyraised

and endorsesan ideologythat is a partof the logic of dominationthey ostensiblyresist,

while participatingin the human-animaldualism.

4. Walkerappearsto mean by this concept that each animal possessesa unique

individuality,sentiency,andcompletenessof self in one'sselfandnot throughothers,and

should exist as such for human beings,not as imagesor as food. Since the concept of

personhoodis extremelyproblematicfromthe perspectiveof feministphilosophy,I will

not use that term though I think that in a general,less philosophicallybaseddiscourse,

this is what my sourcesmean when talkingabout"beingness."

5. My own The SexualPoliticsof Meatbeganas a paperfor Daly'sclasson feminist

ethics (see Adams 1975). In her book The Rapeof theWild,Daly'sclose friendAndree

This content downloaded from 78.56.45.90 on Fri, 13 Jun 2014 10:59:09 AM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

142 Hypatia

CollardappliesDaly'sfeministphilosophyof biophiliato animals.As earlyas 1975Collard

wasworkingon the intersectionof the oppressionof womenandoppressionof animals.

6. Warren'sfourth point, that ecological movements must include a feminist

perspective,is not as apparentin the 1976 interviews.The animalliberationmovement

tracesits roots to Singer's1975 text AnimalLiberation;thus the feministcritiqueof this

movement was not readilyapparentin 1976 because the movement itself was in its

gestationalperiod.Subsequentfeministwritingsapplya feministcritiqueto the animal

liberationmovementwhile agreeingwith the premisethat the exploitationof animals

must be challenged (Kheel, Collard, Corea, Donovan, Salamone). The politics of

identificationis a de factocritiqueof argumentson behalfof animalsbasedon dominant

philosophies,since it does not attempt to establish criteriafor rights but speaks to

responsibilityand relationships.In The SexualPoliticsof Meat, I use feminist literary

criticismas an antidoteto "rights"language.I am currentlydevelopingan (eco)feminist

philosophyof animalrights.

7. Some environmentalists have argued that the complete conversion to

vegetarianismwill precipitatea populationcrisisand thus is less ecologicallyresponsible

than meateating(Callicott 1989,35). This assumesthat we areall heterosexualandthat

womennever will have reproductivefreedom.

8. For environmentalissuesassociatedwith meat productionsee Akers (1983),

Pimental(1975, 1976), Hurand Field (1984, 1985), Krizmanic(1990a and 1990b).

9. A by-productof livestockproductionis methane,a greenhousegas that can trap

twentyto thirtytimesmoresolarheat thancarbondioxide.Largelybecauseof theirburps,

"ruminantanimalsarethe largestproducersof methane,accountingfor 12 to 15 percent

of emissions,accordingto the E.P.A."(ONeill 1990,4).

10. Ninety-five percent of all poultryworkersare black women who face carpal

tunnel syndrome and other disorderscaused by repetitive motion and stress (Clift

1990; Lewis 1990, 175).

11. On this see Robbins(1987) and poet AudreLorde's(1980) descriptionof the

relationshipbetweenbreastcancerand high-fatdiets.

12. While some might arguethat the methodof the relationalhunt eliminatesthe

violenceinherent in other formsof meat eating, I do not see how that term, as it is

commonlyusedtoday,can be seen to be illegitimatelyappliedin the context in which I

use it here. I use violentin the sense of the AmericanHeritageDictionary's definition:

"causedby unexpectedforceor injuryratherthan by naturalcauses."Even if the animal

acquiescesto her/hisdeath, which I arguewe simplydo not know,this death is still not

a resultof naturalcausesbut of externalforcethat requiresthe useof implementsandthe

intent of which is to cause mortalinjury.This is violence, which kills by woundinga

beingwho wouldotherwisecontinue to live.

13. One of the anonymousreviewersraisedthe issuethat plantshave life, too. Due

to spaceconstraintsmy responseto this point had to be omitted;interestedreadersmay

writeto me forthis information.It is importantto acknowledgehoweverthat the greatest

amountof plantexploitationisdueto the growingof plantfoodsto feedterminalanimals.

REFERENCES

Abbott,Sally.1990.The originsof God in thebloodof the lamb.InReueaving

theworld,3540.

IreneDiamondandGloriaFemanOrenstein,eds.SanFrancisco: SierraClubBooks.

This content downloaded from 78.56.45.90 on Fri, 13 Jun 2014 10:59:09 AM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

CarolJ. Adams 143

Adams,Carol. 1975. The oediblecomplex:Feminismand vegetarianism.In Thelesbian

reader.Gina Covina and LaurelGalana,eds. Oakland,CA: Amazon.

. 1990. The sexualpoliticsof meat.New York:Continuum.

Ahlers, Julia. 1990. Thinking like a mountain:Towarda sensible land ethic. Christian

Century(April 25): 433-34.

Akers,Keith. 1983. A vegetarian sourcebook.New York:G. P.Putnam'sSons.

Albino, Donna. 1988.C.E.A.S.E:Buildinganimalconsciousness.An interviewwithJane

Lidsky.Womanof Power.9: 64-66.

Barnard,Neal. 1990. The evolution of the human diet. In The powerof yourplate.

Summertown,TN: BookPublishingCo.

Benney,Norma. 1983.All of one flesh:The rightsof animals.In Reclaimtheearth.Leonie

Caldecottand StephanieLeland,eds. London:The Women'sPress.

Brody,JaneE. 1990. Hugestudyindictsfat and meat.TheNew YorkTimes.May8.

Callicott,J. Baird.1989.Indefenseof thelandethic.Albany:State Universityof New York

Press.

Clift,Elayne.1990.Advocatebattlesforsafetyin minesandpoultryplants.New Directions

for Women(May/June):3.

Coats,C. David. 1989.OldMacDonald's factoryfarm.New York:Continuum.

Collard,Andree, with Joyce Contrucci. 1988. Rapeof the wild:Man'sviolenceagainst

animalsandtheearth.London:The Women'sPress.

Collins, Sheila. 1974.A differentheavenandearth.ValleyForge:JudsonPress.

Comstock, Gary. 1990. Pigs and piety: A theocentric perspectiveon food animals.

Presentedat the Duke Divinity School conference,"Good News for Animals?"

October3-4, 1990.

Corea,Genoveffa.1984. Dominanceand control:How our culturesees women,nature

and animals.TheAnimals'Agenda(May-June):37.

Davis, Karen.1988. Farmanimalsand the feminine connection. The Animals'Agenda

(January-February): 38-39.

d'Eaubonne,Francoise.1974. Feminismordeath[Lefeminismeou la mort].In New French

feminisms:An anthology.ElaineMarksand Isabellede Courtivron,eds. New York:

Shocken Books, 1981.

Donovan,Josephine.1990. Animal rightsand feministtheory.Signs15 (2): 350-75.

EcofeministTaskForceRecommendation-Itemno. 7. 1990. Presentedto the National

Women'sStudiesAssociationnationalmeeting,June,Akron, Ohio.

Elson,John. 1990. This little piggyate roastbeef: Domesticatedporkersare becoming

the latestpet craze.Time.(January22): 54.

Fox, MichaelW. 1984. Farmanimals:Husbandry, behavior,andveterinary

practice(view-

pointsof a critic).Baltimore:UniversityParkPress.

Fraser,David. 1987. Attractionto bloodas a factorin tail-bitingby pigs.AppliedAnimal

Behaviour Science17:61-68.

Gaard, Greta. 1989. Feminists, animals, and the environment:The transformative

potential of feminist theory. Paper presentedat the annual convention of the

National Women'sStudies Association, Towson State University, June 14-18,

Baltimore.

Goodyear,Carmen.1977. Mankind?CountryWomen(December):7-9.

Hoagland,SarahLucia.1988. Lesbianethics:Towardnew values.Palo Alto: Institutefor

LesbianStudies.

Hur, Robin. 1985. Six inches from starvation:How and why America'stopsoil is

disappearing.Vegetarian Times(March):45-47.

This content downloaded from 78.56.45.90 on Fri, 13 Jun 2014 10:59:09 AM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

144 Hypatia

Hur,Robin and Dr. David Fields. 1984. Are high-fatdiets killing ourforests?Vegetarian

Times(February):22-24.

. 1985a. America'sappetite for meat is ruining our water. VegetarianTimes

(January):16-18.

.1985b. How meat robsAmericaof its energy.Vegetarian Times(April):24-27.

Kevles, Bettyann. 1990. Meat, moralityand masculinity.The Women'sReviewof Books

(May): 11-12.

Kheel,Marti.1987. Befriendingthe beast.Creation(September-October):11-12.

. 1988.Animal liberationandenvironmentalethics:Can ecofeminismbridgethe

gap?Paperpresentedat the 1988 annualmeetingof the WesternPoliticalScience

Association,March10-12, 1988.

. 1990. Ecofeminismand deep ecology:Reflectionson identity and difference.

Reweavingtheworld128-37. IreneDiamondand GloriaFemanOrenstein,eds. San

Francisco:SierraClub Books.

Krizmanic,Judy.1990a.Is a burgerworth it?Vegetarian Times152(April):20-21.

. 1990b. Why cutting out meat can cool down the earth. VegetarianTimes

152(April):18-19.

Lappe,FrancesMoore. 1982. Dietfor a smallplanet:Tenthanniversary edition.New York:

BallantineBooks.

Lawrence,A. B., M. C. Appleby,and H. A. Macleod.1988. Measuringhungerin the pig

using operantconditioning:The effect of food restriction.AnimalProduction47:

131-37.

Leapsforward:Postpatriarchal eating. 1990. Ms. (July-August):59.

Lewis,Andrea. 1990. Lookingat the total picture:A Conversationwith health activist

BeverlySmith. In The blackwomen'shealthbook:Speakingfor ourselves.EvelynC.

White, ed. Seattle:The Seal Press.

Lorde,Audre. 1980. Thecancerjournals.Argyle,NY:Spinsters,Ink.

Mason,Jimand PeterSinger.1980.Animalfactories.New York:CrownPublishers.

Mead,Nathaniel. 1990. Special report:6,500 Chinese can't be wrong.Vegetarian Times

158 (October):15-17.

Moran,Victoria.1988. Learninglove at an earlyage:Teachingchildrencompassionfor

animals.Womanof Power9: 54-56.

Newkirk,Ingridwith C. Burnett. 1988. Animal rights and the feminist connection.

Womanof Power9: 67-69.

O'Neill, Molly. 1990. The cow'srole in life is called into questionby a crowdedplanet.

New YorkTimes.(May6, 1990) Section 4: 1, 4.

Ortegay Gasset,Jose. 1985.Meditations on hunting.HowardB. Wescott,trans.New York:

CharlesScribner'sSons.

Pimental,David. 1975. Energyand land constraintsin food proteinproduction.Science

190: 754-61.

. 1976. Land degradation:Effectson food and energy resources.Science194:

149-55.

Pimental, David, P. A. Oltenacu, M. C. Nesheim, John Krummel,M. S. Allen, and

Sterling Chick. 1980. The potential for grass-fedlivestock:Resourceconstraints.

Science207: 843-848.

Robbins,John. 1987. Dietfor a new America.Walpole:Stillpoint.

Ruether,Rosemary.1975. New woman/newearth:Sexistideologies and humanliberation.

New York:SeaburyPress.

This content downloaded from 78.56.45.90 on Fri, 13 Jun 2014 10:59:09 AM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

CarolJ. Adams 145

. 1990. Men, women and beasts: Relations to animals in Western culture.

Presentedat the Duke Divinity School conference, "Good News for Animals?"

October3, 1990.

Salamone,Connie. 1973. Feministas rapistin the modem malehunterculture.Majority

Report(October).

. 1982. The prevalenceof the naturallaw within women:Women and animal

rights.In Reweavingthewebof life:Feminismandnonviolence.Pam McAllister,ed.

Philadelphia:New Society Publishers.

.1988. The knowing.Womanof Power9: 53.

Serpell,James. 1986. In the companyof animals:A studyof human-animal

relationships.

Oxford:BasilBlackwell.

Shiva,Vandana.1988.Stayingalive:Women,ecologyanddevelopment. London:ZedBooks.

2d ed.New York:A New YorkReviewBook.

Singer,Peter.(1975) 1990.Animalliberation.

Spretnak,Charlene.1990.Ecofeminism:Ourrootsandflowering.In Reweaving theworld.

IreneDiamondandGloriaFemanOrenstein,eds.San Francisco:SierraClubBooks.

Walker,Alice. 1986. Am I Blue,Ms. July30.

.1988a. Why did the Balinesechicken crossthe road?Womanof Power9: 50.

Waring,Marilyn.1988.If womencounted:A newfeministeconomics.San Francisco:Harper

& Row.

Warren,KarenJ. 1987. Feminismandecology:MakingconnectionsEnvironmental Ethics

9:3-21.

.1990. The powerand the promiseof ecologicalfeminism.Environmental Ethics

12: 125-46.

This content downloaded from 78.56.45.90 on Fri, 13 Jun 2014 10:59:09 AM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

You might also like

- The Human Animal Earthling Identity: Shared Values Unifying Human Rights, Animal Rights, and Environmental MovementsFrom EverandThe Human Animal Earthling Identity: Shared Values Unifying Human Rights, Animal Rights, and Environmental MovementsNo ratings yet

- Carol J. Adams, Lori Gruen - Ecofeminism. Feminist Intersections With Other Animals and The Earth-Bloomsbury (2014)Document339 pagesCarol J. Adams, Lori Gruen - Ecofeminism. Feminist Intersections With Other Animals and The Earth-Bloomsbury (2014)favillesco100% (3)

- Ecofeminism RevisitedDocument8 pagesEcofeminism RevisitedCarl CabasagNo ratings yet

- Rain Without Thunder: The Ideology of the Animal Rights MovementFrom EverandRain Without Thunder: The Ideology of the Animal Rights MovementRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (11)

- Dominion over Wildlife?: An Environmental Theology of Human-Wildlife RelationsFrom EverandDominion over Wildlife?: An Environmental Theology of Human-Wildlife RelationsNo ratings yet

- Karen J. Warren - The Power and Premise of Ecological FeminismDocument22 pagesKaren J. Warren - The Power and Premise of Ecological FeminismEmilioAhumada100% (2)

- A Brief Survey of Ecofeminism PDFDocument4 pagesA Brief Survey of Ecofeminism PDFAnonymous Bc9MjRClNo ratings yet

- Introduction To Environment Assignment 1Document50 pagesIntroduction To Environment Assignment 1Midway HorsesNo ratings yet

- Animals and Women Feminist Theoretical Explorations by Carol J. Adams Josephine DonovanDocument276 pagesAnimals and Women Feminist Theoretical Explorations by Carol J. Adams Josephine DonovanĪśvari AmazonaNo ratings yet

- Agarwal, B 1992 TheGenderAndEnvironmentDebateDocument41 pagesAgarwal, B 1992 TheGenderAndEnvironmentDebateSipokazi NongauzaNo ratings yet

- EcofemenismDocument7 pagesEcofemenismapi-269529445No ratings yet

- Political Theory and EcologyDocument14 pagesPolitical Theory and EcologyDHRUV CHOPRANo ratings yet

- The Feminist Care Tradition in Animal Ethi - UnknownDocument406 pagesThe Feminist Care Tradition in Animal Ethi - UnknownAlberto VillarrealNo ratings yet

- Ethics and the Beast: A Speciesist Argument for Animal LiberationFrom EverandEthics and the Beast: A Speciesist Argument for Animal LiberationRating: 5 out of 5 stars5/5 (1)

- Ecofeminist Philosophy © Rita D. Sherma © Care - GtuDocument6 pagesEcofeminist Philosophy © Rita D. Sherma © Care - GtuKath GloverNo ratings yet

- How Ecofeminism Works: Winifred Fordham MetzDocument9 pagesHow Ecofeminism Works: Winifred Fordham MetzAleksandraZikicNo ratings yet

- Appunti Lezione Storia Delle DonneDocument58 pagesAppunti Lezione Storia Delle DonneAnna Pia RuoccoNo ratings yet

- Sexual Selections: What We Can and Can’t Learn about Sex from AnimalsFrom EverandSexual Selections: What We Can and Can’t Learn about Sex from AnimalsRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (8)

- The Vegan Studies Project: Food, Animals, and Gender in the Age of TerrorFrom EverandThe Vegan Studies Project: Food, Animals, and Gender in the Age of TerrorRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (5)

- Agarwal 1992Document41 pagesAgarwal 1992DHRUV KAYESTHNo ratings yet

- Thinking Veganism in Literature and Culture: Towards a Vegan TheoryFrom EverandThinking Veganism in Literature and Culture: Towards a Vegan TheoryEmelia QuinnNo ratings yet

- Sexy Orchids Make Lousy Lovers: & Other Unusual RelationshipsFrom EverandSexy Orchids Make Lousy Lovers: & Other Unusual RelationshipsRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (1)

- Consistency in Ecofeminist Ethics ConteDocument15 pagesConsistency in Ecofeminist Ethics ConteMaroun BadrNo ratings yet

- Flourishing With Awkward Creatures: Togetherness, Vulnerability, KillingDocument11 pagesFlourishing With Awkward Creatures: Togetherness, Vulnerability, Killingjuann_m_sanchezNo ratings yet

- Invasive Plant Medicine: The Ecological Benefits and Healing Abilities of InvasivesFrom EverandInvasive Plant Medicine: The Ecological Benefits and Healing Abilities of InvasivesRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (5)

- Ec of em Revisited FFDocument29 pagesEc of em Revisited FFSha HernandezNo ratings yet

- EcofeminismsDocument3 pagesEcofeminismsJessikaNo ratings yet

- EcofeminismoDocument8 pagesEcofeminismoveronicaliz29No ratings yet

- HypatiaDocument20 pagesHypatiaGrey NataliaNo ratings yet

- Ecofeminism - WikipediaDocument24 pagesEcofeminism - WikipediaSaumyabrata GaunyaNo ratings yet

- International, Indexed, Multilingual, Referred, Interdisciplinary, Monthly Research JournalDocument2 pagesInternational, Indexed, Multilingual, Referred, Interdisciplinary, Monthly Research Journaldr_kbsinghNo ratings yet

- Visionary Plant Consciousness: The Shamanic Teachings of the Plant WorldFrom EverandVisionary Plant Consciousness: The Shamanic Teachings of the Plant WorldRating: 5 out of 5 stars5/5 (1)

- Animal Rites: American Culture, the Discourse of Species, and Posthumanist TheoryFrom EverandAnimal Rites: American Culture, the Discourse of Species, and Posthumanist TheoryRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (6)

- Ecofeminist Thought & PracticeDocument19 pagesEcofeminist Thought & PracticeLizaNo ratings yet

- EcofeminsimDocument28 pagesEcofeminsimSharifa Sultana Pinky100% (1)

- Through a Vegan Studies Lens: Textual Ethics and Lived ActivismFrom EverandThrough a Vegan Studies Lens: Textual Ethics and Lived ActivismNo ratings yet

- FT Lecture VDocument20 pagesFT Lecture Vmameb7362No ratings yet

- Critical Perspectives On Veganism: Edited by Jodey Castricano and Rasmus R. SimonsenDocument420 pagesCritical Perspectives On Veganism: Edited by Jodey Castricano and Rasmus R. SimonsenCarla Suárez FélixNo ratings yet

- Ecofeminism - Britannica Online EncyclopediaDocument5 pagesEcofeminism - Britannica Online EncyclopediaAzher AbdullahNo ratings yet

- Hotel Transportation and Discount Information Chart - February 2013Document29 pagesHotel Transportation and Discount Information Chart - February 2013scfp4091No ratings yet

- Bio1 11 - 12 Q1 0501 FDDocument23 pagesBio1 11 - 12 Q1 0501 FDIsabelle SchollardNo ratings yet

- ListwarehouseDocument1 pageListwarehouseKautilya KalyanNo ratings yet

- Responsibility Accounting Practice ProblemDocument4 pagesResponsibility Accounting Practice ProblemBeomiNo ratings yet

- Sample Quantitative Descriptive Paper 1Document20 pagesSample Quantitative Descriptive Paper 1oishimontrevanNo ratings yet

- Emergency War Surgery Nato HandbookDocument384 pagesEmergency War Surgery Nato Handbookboubiyou100% (1)

- MS 1979 2015Document44 pagesMS 1979 2015SHARIFFAH KHAIRUNNISA BINTI SYED MUHAMMAD NASIR A19EE0151No ratings yet

- Non-Binary or Genderqueer GendersDocument9 pagesNon-Binary or Genderqueer GendersJuan SerranoNo ratings yet

- Purpose in Life Is A Robust Protective Factor of Reported Cognitive Decline Among Late Middle-Aged Adults: The Emory Healthy Aging StudyDocument8 pagesPurpose in Life Is A Robust Protective Factor of Reported Cognitive Decline Among Late Middle-Aged Adults: The Emory Healthy Aging StudyRaúl AñariNo ratings yet

- Invertec 200 260 400tDocument16 pagesInvertec 200 260 400tJxyz QwNo ratings yet

- Public Speaking ScriptDocument2 pagesPublic Speaking ScriptDhia MizaNo ratings yet

- Mil-Std-1949a NoticeDocument3 pagesMil-Std-1949a NoticeGökhan ÇiçekNo ratings yet

- Evaluation of Whole-Body Vibration (WBV) On Ready Mixed Concrete Truck DriversDocument8 pagesEvaluation of Whole-Body Vibration (WBV) On Ready Mixed Concrete Truck DriversmariaNo ratings yet

- ReclosersDocument28 pagesReclosersSteven BeharryNo ratings yet

- Case Study of Flixborough UK DisasterDocument52 pagesCase Study of Flixborough UK Disasteraman shaikhNo ratings yet

- 27nov12 PA Task Force On Child Protection ReportDocument445 pages27nov12 PA Task Force On Child Protection ReportDefendAChildNo ratings yet

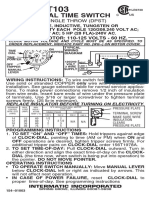

- T103 InstructionsDocument1 pageT103 Instructionsjtcool74No ratings yet

- NHT Series High-Throughput Diffusion PumpsDocument12 pagesNHT Series High-Throughput Diffusion PumpsJosé Mauricio Bonilla TobónNo ratings yet

- Compounds and Chemical FormulasDocument35 pagesCompounds and Chemical Formulasjolina OctaNo ratings yet

- HandbookDocument6 pagesHandbookAryan SinghNo ratings yet

- Guarantor Indemnity For Illness or DeathDocument2 pagesGuarantor Indemnity For Illness or Deathlajaun hindsNo ratings yet

- Sore Throat, Hoarseness and Otitis MediaDocument19 pagesSore Throat, Hoarseness and Otitis MediaainaNo ratings yet

- Final PR 2 CheckedDocument23 pagesFinal PR 2 CheckedCindy PalenNo ratings yet

- Subhead-5 Pump Motors & Related WorksDocument24 pagesSubhead-5 Pump Motors & Related Worksriyad mahmudNo ratings yet

- 18-MCE-49 Lab Session 01Document5 pages18-MCE-49 Lab Session 01Waqar IbrahimNo ratings yet

- Oral Airway InsertionDocument3 pagesOral Airway InsertionSajid HolyNo ratings yet

- தமிழ் உணவு வகைகள் (Tamil Cuisine) (Archive) - SkyscraperCityDocument37 pagesதமிழ் உணவு வகைகள் (Tamil Cuisine) (Archive) - SkyscraperCityAsantony Raj0% (1)

- Esc200 12Document1 pageEsc200 12Anzad AzeezNo ratings yet

- Unit 5.4 - Incapacity As A Ground For DismissalDocument15 pagesUnit 5.4 - Incapacity As A Ground For DismissalDylan BanksNo ratings yet

- Red Bank Squadron - 01/22/1942Document28 pagesRed Bank Squadron - 01/22/1942CAP History LibraryNo ratings yet