Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Manpower Development in Agricultural Engineering in Selected Developing Countries

Uploaded by

pawanroyalOriginal Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Manpower Development in Agricultural Engineering in Selected Developing Countries

Uploaded by

pawanroyalCopyright:

Available Formats

MANPOWER DEVELOPMENT IN AGRICULTURAL ENGINEERING

IN SELECTED DEVELOPING COUNTRIES

MANPOWER DEVELOPMENT IN AGRICULTURAL ENGINEERING

IN SELECTED DEVELOPING COUNTRIES

KREPL,V., Czech University of Life Sciences Prague, Czech Republic

Abstract

The potential and crucial role of agricultural engineering, and therefore of

agricultural engineers, in development has not always been recognized. A number of

spectacular failures in the past involving poorly adapted schemes of agricultural engineering

let planners to neglect and even resist investment in this sector. Yet, to neglect investment in

this sector denies a society the possibility of raising its agricultural performance beyond

subsistence levels. Manpower development is recognized as being of prime importance for the

successful execution of agricultural development programs and continues to constitute a

major component of FAO activities

Objective of the project (2007) is based on the project in manpower area in agricultural

engineering in Zimbabwe, Tanzania, Republic of Congo and Guinea – Conakry as the

FAO follow-up project from 1989.

It is hoped that the ordered approach will allow a more rational analysis of potential

problems in the planning and execution stages of training and educational programs, and so,

in this way, provide a valuable service towards the future development of trained manpower

in agricultural engineering.

Key words: manpower development, agricultural engineering, education and training in

LDCs, education – tool against poverty,

Krepl,V.; ITS CULS Prague, 160 21 Prague 6 Suchdol, Czech Republic 2

MANPOWER DEVELOPMENT IN AGRICULTURAL ENGINEERING

IN SELECTED DEVELOPING COUNTRIES

KREPL,V., Institute of Tropics and Subtropics, Czech University of Life Sciences

Prague, Czech Republic

Introduction

The potential and crucial role of agricultural engineering, and therefore of agricultural

engineers, in development has not always been recognized. A number of spectacular failures

in the past involving poorly adapted schemes of agricultural engineering led planners to

neglect and even resist investment in this sector. Yet, to neglect investment in this sector

denies a society the possibility of raising its agricultural performance beyond subsistence

levels.

Manpower development is recognized as being of prime importance for the successful

execution of agricultural development programs and continues to constitute a major

component of FAO activities. Many developing countries are experiencing high population

growths leading to ever increasing food requirements. Adequately trained personnel are

essential for tackling this situation and the needs are particularly acute for engineers,

technicians and craftsmen, trained in the skills required for the application of engineering to

agriculture.

The desirability of balanced and appropriate agricultural mechanization is now recognized as

a vital ingredient in agricultural development plans. The engineering introduced must be

effective and those charged with the tasks of its management and promotion must be

adequately trained and educated. This publication aim to address the problems associated with

Krepl,V.; ITS CULS Prague, 160 21 Prague 6 Suchdol, Czech Republic 3

planning the manpower resource requirements and the development or establishment of

appropriates training facilities and programs.

The development of Agricultural Engineering - the social and economic context

Agricultural engineering is deeply involved in the process of social and economic change and

has strongly affected development, as now witnessed in the modern world. Viewed in its

broadest context agricultural engineering lay at the heart of the earliest forms of civilization,

which developed around the river systems of the Middle East, Egypt and China.

On the mechanical side, agricultural engineering has its roots in the village blacksmiths and

artisans making hand tools and equipment. Agricultural engineering is still at the black

smiting stage in many developing countries whereas in the developed world, many families of

the more progressive artisans of the last century have developed from their village forges into

some of the largest national and multinational manufacturers of agricultural machinery.

The striking difference between a modern developing economy and most of the developed

nations of the world today is that the developing country, with its developing economy, can

choose its path of development. It may either pursue the path of gradual and slowly

accelerating progress towards higher levels of agricultural mechanization; or, it may attempt

to take immediate advantage of the advances in technology that are available from the

developed world.

The process of rural change accompanying agricultural mechanization development is

beset with social and economic difficulties. All engaged in agricultural mechanization

programs should be made aware of the hazards, possibilities, and successes that have emerged

during their establishment.

Krepl,V.; ITS CULS Prague, 160 21 Prague 6 Suchdol, Czech Republic 4

The introduction of new machines has often brought associated social problems. The

Scottish millwright Andrew Meikle patented his threshing machine in 1788 and over the next

30 years, several inventors and craftsmen produced machines in Britain. In 1830, the

threshing machine became a target for the large numbers of unemployed returning from the

Napoleonic wars, and demanding work and higher wages. Hay barns were burned and about

400 machines were destroyed in two years of violence.

More recently, several distressing examples of severe economic conditions have

resulted at least in part from over-hasty and ill-conceived schemes to introduce

mechanization. Massive agricultural machinery imports were organized in the 1960's and

1970's to several developing nations. These soon resulted in high levels of machinery

breakdowns as the existing servicing facilities and number of skilled machinery operators and

managers proved inadequate.

An important historical lesson to be learned from developed economies is the close

interaction between agricultural and industrial development. In an economy dominated by

agriculture it is both natural and necessary for small farmers to obtain their tools and

equipment from local manufacturers and artisans, who can not only supply what is required,

but can also service and repair the goods they have supplied. The promotion of and assistance

towards the local manufacture and servicing of agricultural machinery provides the basis for

the eventual development of a more comprehensive indigenous manufacturing industry.

Some early groupings of agricultural engineers

One of the first groupings of agricultural engineers was the formation of the

Agricultural Engineers Association by Messrs Ransome, Shuttleworth and Fowler in London

on November 2; 1875. The Royal Agricultural Society was founded in 1838, and continues its

Krepl,V.; ITS CULS Prague, 160 21 Prague 6 Suchdol, Czech Republic 5

tradition of awards for innovative agricultural machines which are still exhibited annually at

the Silver Award stand of the UK's Royal Show.

Specialist commercial publications also started to appear such as Farm Implement

News in 1879, published in the United Sates. The first President of the American Society of

Agricultural Engineers (ASAE) took office in 1908. By 1912, another American, Dr Sam

Higginbottom had started a specialist course in agricultural engineering when founding the

Allahabad Agricultural Institute in India.

Development of agricultural engineering as a profession

Agricultural engineering has most commonly been defined as the application of

engineering principles to agriculture. It thus involves many different established branches of

engineering and associated disciplines, and progressed to the stage where its own professional

institutions are established in many countries.

More recently, specialist groups of agricultural engineers have formed societies to

promote professional interchange within their particular discipline - the West Africa Animal

Traction Network, the International Commission on Irrigation and Drainage, the Commission

Internationale du Génie Rural, the International Society for Terrain-Vehicle Systems are

examples of organizations active today.

Members of other Institutions who felt that an area of expertise, which properly belonged

to them, was being poached have often resisted the establishment of the new profession of

agricultural engineering. The ranks of the Mechanical Engineering profession felt that Power

and Machinery lay more appropriately within their domain, while the Civil Engineering

profession have claimed that matters of irrigation and water supply are properly the interest of

Civil Engineers.

Krepl,V.; ITS CULS Prague, 160 21 Prague 6 Suchdol, Czech Republic 6

Present status of agricultural engineering

The establishment of agricultural engineering as a profession is thus comparatively

recent in many countries and indeed it has yet to take place in many of the developing nations.

The professional status of the agricultural engineer varies widely in consequence and

continues to be the subject of debate.

The first ever society of agricultural engineers (the American Society of Agricultural

Engineers, or ASAE) was formed in the United States more than a I00 years ago, but it is

today seriously debating a change of name to reflect the change in emphasis of members'

activities. The term biological engineering or bioengineering are amongst those it has been

suggested be adopted in the new title. Student enrolment in traditional agricultural

engineering courses at the Bachelor's level in both the United States and Britain has dropped

markedly over the last 20 years although the specialist courses offered at Diploma and

Master's level continue to attract considerable interest.

Many of these courses are however designed for future activities outside the more

traditional fields of agricultural mechanization or soil and water engineering. Topics such as

agricultural water management, information technology for the rural sector, rural engineering,

environmental engineering, experiment station operations management, are but a few of the

options currently available at different institutions of education.

Language can further affect the status of the profession within a country. For example

the French equivalent of "Génie Rural" normally involves activities of installation and

operation of large-scale irrigation schemes, road engineering and rural buildings. A

professional however working in environmental control systems, agricultural machinery

design or manufacture or perhaps post harvest processing is likely to adopt an alternative title

for his profession.

Krepl,V.; ITS CULS Prague, 160 21 Prague 6 Suchdol, Czech Republic 7

The Spanish equivalent normally used is "Ingeniería Agrícola" which creates great

confusion with the professional agronomist who has the title "Ingeniero Agronomo" . In many

Hispanic countries this leads to considerable problems in recruiting good agricultural

engineers into the public sector as their salary scales are often similar or only marginally

higher than those of the "Ingeniero Agronomo". In contrast, if he was classified as an

"Ingeniero Civil" or an "Ingeniero Mecánico", the scale would be considerably higher. This

situation can of course have an adverse effect on student recruitment into agricultural

engineering courses as those with a strong interest in engineering are likely to opt for the

mechanical or civil engineering courses offering better prospects.

Specific features of Manpower Development.

The questionnaire test was provided in the end of eighties by the FAO, AGSE Department.

For provability the above mentioned test the questioner for year 2007 was modified from

original questioner from 1989.

The test was apply for the same country: Zimbabwe, Tanzania, Democratic Republic of

Congo and Guinea - Conakry.

Results

The replies received indicated a general agreement to several questions:

- All countries projected in 1989 additional requirements for the number of graduates with

employment foreseen mainly in the Ministry and Regional Offices (15%), industry and

Krepl,V.; ITS CULS Prague, 160 21 Prague 6 Suchdol, Czech Republic 8

agricultural services (28%) and the extension and advisory services (24%).

Results from 2007 presents in the same question move to up in – Ministry and Regional

Offices 18% (+ 3%), Industry and Agricultural Services 32% ( + 4%), Research and

Development 13% (+ 3%). On the opposite site is Extension/ Advisory Services 17%

(- 7%)!!!

- Most countries suggested in 1989 a broad coverage of agricultural engineering subjects at

the undergraduate level, although their opinions on specialization at the postgraduate level

were divided.

Result from 2007 presents in the same question a similar suggestion, only order of countries

is changed.

- All countries suggested in 1989 improvements to the quantity and quality of practical

training for educational courses.

Results from 2007 presents in the same question the same suggestion, so that the practical

training could be as a part of regular Agricultural Engineering Education Programme.

- The majority of countries reported in 1989 that they lacked sufficient technicians at the

certificate and diploma levels, although there was a wide variation both in estimates of

existing numbers and requirements.

Result from 2007 presents in the same question similar or the same answers. The annotated

findings are summarized below.

Krepl,V.; ITS CULS Prague, 160 21 Prague 6 Suchdol, Czech Republic 9

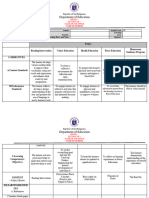

Summary of Country Questionnaire Replies

Question ZIM URT PRC GUI

No. of agricultural engineering graduates

- National University 0 23 0 21

- Foreign University 32 48 67 97

Where employed: (percentages)

Ministry & Reg. Offices 19 12 12 73

Industry & Agro. Services 29 36 53 12

Extension/Advisory Services 9 23 13 6

Teaching 19 10 9 3

Research and Development 14 6 3 2

Farming 9 12 5 3

Other 1 1 5 1

Total number of Agricultural Engineering

graduates in the following years:

1990 80 127 46 168

1991 - 1995 102 97 53 177

1996 – 2000 163 279 99 331

Where they worked 1991 -1995 (percentages)

- Ministry & Regional Offices 15 12 16 33

- Industry & Agricultural Services 57 44 23 17

- Extension/Advisory Services 19 17 14 22

- Teaching 5 7 12 15

- Research and Development 13 17 14 8

- Farming 8 12 14 8

- Other 1 2 -- 2

Are there any officially estimated requirements

for Agricultural Engineering graduates?

(Ministry figure) 190 220 No 100

(University figure) No 300 No No

(FAO figure) 200 300 100 150

Priority sectors of Agricultural Engineering

(1 = highest):

- Agricultural mechanization 2 3 3 3

- Soil and water engineering 2 3 3 3

- Storage and processing 4 4 3 3

- Rural structures 4 4 3 3

- Management and planning 3 4 3 4

- Other: Agro-industries 5 5 5 5

Renewable energy 5 6 5 6

Krepl,V.; ITS CULS Prague, 160 21 Prague 6 Suchdol, Czech Republic 10

Graph No.1

Number of graduates in Agricultural Engineering according to placement 1989

Graph No. 2 Number of graduates in Agricultural Engineering according to placement 2004

Krepl,V.; ITS CULS Prague, 160 21 Prague 6 Suchdol, Czech Republic 11

Graph No. 3 Research questioner results

References:

- APPLEBEE, A. N. 1996. Curriculum as conversation: transforming traditions of teaching

and learning. Chicago, IL, USA, University of Chicago Press.

- ARGYRIS, C. & SCHON, D. A. 1998. Organisational learning II: theory, method and

practice. Reading, UK, Addison-Wesley.

- BAGCHEE, A. 1999. Agricultural extension in Africa. World Bank Discussion Paper No.

231. Africa Technical Department Series. Washington, DC, World Bank.

Krepl,V.; ITS CULS Prague, 160 21 Prague 6 Suchdol, Czech Republic 12

- CLEAVER, K. M. 2003. A strategy to develop agriculture in sub-Saharan Africa and a

focus for the World Bank. World Bank Technical Paper No. 203. Washington, DC, World

Bank.

- CURRY, B. K. (ed.) 1999. Instituting enduring innovations: achieving continuity of

change in higher education. Report Seven, Syracuse, NY, USA, ASHE-ERIC Higher

educational Reports.

- FAO. 1998.Rerport of the global consultation on agricultural extension. Rome, FAO.

- FAO. 1999. Training for agriculture and rural development. Economics and Social

Development Series No. 54. Rome, FAO.

- KOLB, D. 2001. Experiential learning: experience as a source of learning and

development. Englewood Cliffs, NJ, USA, Prentice Hall.

- KRANZ Jr., R. G. 1999. A theoretical context for designing curricula in the agricultural

and life sciences. In Lunde, J.L., Baker, M., Buelow, F.H. & Hayes, L.S. (eds.) 1995.

Resharping curricula: realization programmes at three Land Grant Universities, p. 4-12.

Bolton, USA, Anker Publishing Company.

- KUNKEL, H.O., MAW, I.L. & SKAGGS, C.L. (eds.) 1996. Revolutionizing higher

education in agriculture: a framework for change. Ames, IA, USA, Iowa University Press.

- MACADAM, R.D. & BAWDEN, R.J. 1995. Challenges and response: developing a

system for educating more effective agriculturists. Prometheus, 3(1).

- SHORT, K.G. & BURKE, C. 2002. Creating curriculum: teachers and students as a

community of learners. Portsmouth, NH, USA, Heinemann.

- STEELE, R.E., ONYANGO, C.A., KEREGERO, K.J.B. & DLAMINI, B.M. 1999.

Preparing African agricultural and extension educators to meet future challenges: an

analysis of university programmes in Kenya, Tanzania

Krepl,V.; ITS CULS Prague, 160 21 Prague 6 Suchdol, Czech Republic 13

Authors’ address:

Doc. Ing. Vladimir KREPL, CSc.

Czech University of Life Sciences Prague

Institute of Tropics and Subtropics

165 21 Prague 6 Suchdol

Czech Republic

krepl@its.czu.cz

word count: 2511

Krepl,V.; ITS CULS Prague, 160 21 Prague 6 Suchdol, Czech Republic 14

You might also like

- Appropriate Tech For African WomenDocument109 pagesAppropriate Tech For African WomenjimborenoNo ratings yet

- NABARD (Volume 10)Document44 pagesNABARD (Volume 10)Bharadwaj A S R SNo ratings yet

- AE1 - Module1-Development of Agricultural EngineeringDocument6 pagesAE1 - Module1-Development of Agricultural EngineeringSittie Farhani UsmanNo ratings yet

- A T0408e PDFDocument71 pagesA T0408e PDFAlexis kabayizaNo ratings yet

- Career As An Agricultural, Optical, Or Nuclear EngineerFrom EverandCareer As An Agricultural, Optical, Or Nuclear EngineerNo ratings yet

- Proj LaizaDocument15 pagesProj LaizaIlidio SamboNo ratings yet

- Fractal Modernisation Model of Industrial Areas’ Environment in Developing CountriesFrom EverandFractal Modernisation Model of Industrial Areas’ Environment in Developing CountriesNo ratings yet

- Project FinalDocument66 pagesProject FinalLogheswaran StNo ratings yet

- Characteristics of The Agricultural Sector of The 21st CenturyDocument12 pagesCharacteristics of The Agricultural Sector of The 21st Centuryalizey chNo ratings yet

- Agriculture EngineerDocument30 pagesAgriculture EngineerWaheed BukhariNo ratings yet

- The Agricultural Mechanization in Ecuador: An Initial Vision of DiscussionDocument3 pagesThe Agricultural Mechanization in Ecuador: An Initial Vision of DiscussionFaviKamuendoNo ratings yet

- Rural Development Putting Theory Into PracticeDocument16 pagesRural Development Putting Theory Into PracticeNomcebo DhlaminiNo ratings yet

- The role of agricultural engineering in driving economic growthDocument47 pagesThe role of agricultural engineering in driving economic growthSpinozaNo ratings yet

- Farm Structures in Tropical Climates - Ch1Document11 pagesFarm Structures in Tropical Climates - Ch1Kevin YaptencoNo ratings yet

- Case StudyDocument5 pagesCase StudyaumanlynheartNo ratings yet

- Article Agriculture EngineeringDocument3 pagesArticle Agriculture Engineeringghiffari ghaniNo ratings yet

- Journal of Global History explores machines, modernity, and sugar in the Greater CaribbeanDocument26 pagesJournal of Global History explores machines, modernity, and sugar in the Greater CaribbeanDes HNo ratings yet

- Powering Accra's Future: Projecting Electricity DemandDocument118 pagesPowering Accra's Future: Projecting Electricity DemandMichael Adu-boahenNo ratings yet

- Strategies For Agricultural Developmentt: Vernonw. Ruttan and Yujiro HayamiDocument20 pagesStrategies For Agricultural Developmentt: Vernonw. Ruttan and Yujiro HayamiRakkel RoseNo ratings yet

- The future role of biofuels in the new energy transition: Lessons and perspectives of biofuels in BrazilFrom EverandThe future role of biofuels in the new energy transition: Lessons and perspectives of biofuels in BrazilNo ratings yet

- Module 5 AE 12Document8 pagesModule 5 AE 12Ron Hanson AvelinoNo ratings yet

- AgricultureDocument1 pageAgricultureThế Nhân TrầnNo ratings yet

- Retrospective and Perspectives of Teaching in Machinery Automation Mechatronics and Agricultural Robotics in MexicoDocument4 pagesRetrospective and Perspectives of Teaching in Machinery Automation Mechatronics and Agricultural Robotics in Mexicocuauhtemoc negreteNo ratings yet

- Literature Review On Farm MechanizationDocument7 pagesLiterature Review On Farm Mechanizationorlfgcvkg100% (1)

- Agricultural Implements and Machines in the Collection of the National Museum of History and Technology Smithsonian Studies in History and Technology, No. 17From EverandAgricultural Implements and Machines in the Collection of the National Museum of History and Technology Smithsonian Studies in History and Technology, No. 17No ratings yet

- Digitalization of Agricultural Industry – the Vector of Strategic Development of Agro-Industrial Regions in RussiaDocument141 pagesDigitalization of Agricultural Industry – the Vector of Strategic Development of Agro-Industrial Regions in Russiaprofos24No ratings yet

- New Ways for Indigenous Manufacturing: How Research Revelations Have Defined a Future PathFrom EverandNew Ways for Indigenous Manufacturing: How Research Revelations Have Defined a Future PathNo ratings yet

- Power Tillers For Demining in Sri Lanka: Participatory Design of Low-Cost TechnologyDocument28 pagesPower Tillers For Demining in Sri Lanka: Participatory Design of Low-Cost TechnologyMohd HafizzNo ratings yet

- Flowers of Evil Industrialization and Long Run Development - Raphael FranckDocument39 pagesFlowers of Evil Industrialization and Long Run Development - Raphael FranckTHE LENHANo ratings yet

- Agricultural Mechanization: An Overview of the Role of Mechanization in Agricultural DevelopmentDocument18 pagesAgricultural Mechanization: An Overview of the Role of Mechanization in Agricultural DevelopmentlucyNo ratings yet

- Proceedings from the International Conference on Advances in Engineering and Technology (AET2006)From EverandProceedings from the International Conference on Advances in Engineering and Technology (AET2006)Jackson MwakaliNo ratings yet

- PLAN 423 - Module 4 and 5 UpdatedDocument39 pagesPLAN 423 - Module 4 and 5 UpdatedABCD EFGNo ratings yet

- Mokyr Et Al. (2022 EJ) The Wheels of Change. Technology Adoption, Millwrights and The Persistence in Britains IndustrialisationDocument33 pagesMokyr Et Al. (2022 EJ) The Wheels of Change. Technology Adoption, Millwrights and The Persistence in Britains IndustrialisationPietro QuerciNo ratings yet

- Challenges Facing Labour-Intensive Public Works Programmes and Projects in South AfricaDocument9 pagesChallenges Facing Labour-Intensive Public Works Programmes and Projects in South AfricaAoru SamuelNo ratings yet

- 1950 Readings Agri Economics 1950 Prof Ramanna First Class Ag Econ 101 StudentsDocument174 pages1950 Readings Agri Economics 1950 Prof Ramanna First Class Ag Econ 101 Studentsडॉ. शुभेंदु शेखर शुक्लाNo ratings yet

- Technological Forecasting & Social ChangeDocument19 pagesTechnological Forecasting & Social Changelukman hakimNo ratings yet

- Industrial RevolutionDocument9 pagesIndustrial RevolutionRiffat Hayat MalikNo ratings yet

- guelph-ae-68-02_editedDocument29 pagesguelph-ae-68-02_editedHeena KapoorNo ratings yet

- Precision Agriculture Technologies For Crop and Livestock Production in The Czech RepublicDocument18 pagesPrecision Agriculture Technologies For Crop and Livestock Production in The Czech RepublicLiv CBNo ratings yet

- Agricultural Mechanization in AfricaDocument32 pagesAgricultural Mechanization in AfricaSsemwogerere CharlesNo ratings yet

- Fce 571 Report NarokDocument45 pagesFce 571 Report Narok1man1bookNo ratings yet

- Resurgent Africa: Structural Transformation in Sustainable DevelopmentFrom EverandResurgent Africa: Structural Transformation in Sustainable DevelopmentNo ratings yet

- Technology Transfer and Change in the Arab World: The Proceedings of a Seminar of the United Nations Economic Commission for Western Asia organized by the Natural Resources, Science and Technology Division, Beirut, 9-14 October 1977From EverandTechnology Transfer and Change in the Arab World: The Proceedings of a Seminar of the United Nations Economic Commission for Western Asia organized by the Natural Resources, Science and Technology Division, Beirut, 9-14 October 1977A. B. ZahlanNo ratings yet

- Africa: The African Union and New Partnership For Africa's Development (NEPAD) - The Power FootprintDocument58 pagesAfrica: The African Union and New Partnership For Africa's Development (NEPAD) - The Power FootprintdanielraqueNo ratings yet

- Hand Pump Maintenance 1977 PDFDocument40 pagesHand Pump Maintenance 1977 PDFmvqfernandesNo ratings yet

- 05 HarwoodDocument25 pages05 HarwoodChemutai EzekielNo ratings yet

- 1 - AM Strategy - CIGR - APCAEM PDFDocument17 pages1 - AM Strategy - CIGR - APCAEM PDFTinton Tonika SurbaktiNo ratings yet

- Marin 2015Document16 pagesMarin 2015salsabila fitristantiNo ratings yet

- Landes - The Industrial Revolution 1972 - Introduction PDFDocument20 pagesLandes - The Industrial Revolution 1972 - Introduction PDFcapelloNo ratings yet

- ECONOMICS-III Project On: Industrialisation and Its RoleDocument15 pagesECONOMICS-III Project On: Industrialisation and Its RoleDeepak Sharma100% (1)

- Future of Robotics Agriculture 1Document36 pagesFuture of Robotics Agriculture 1Asma RafiqNo ratings yet

- Industrialization in BangladeshDocument33 pagesIndustrialization in Bangladeshjaberalislam57% (7)

- Agricultural Robotics:: The Future of Robotic AgricultureDocument36 pagesAgricultural Robotics:: The Future of Robotic Agriculturesrinitha mothukuNo ratings yet

- Industrial Revolution Thesis StatementDocument7 pagesIndustrial Revolution Thesis Statementafcmqldsw100% (2)

- The Product Cycle and the Rise and Fall of New England's Textile IndustryDocument22 pagesThe Product Cycle and the Rise and Fall of New England's Textile IndustryK60 Lê Ngọc Minh KhuêNo ratings yet

- Stockdale PDFDocument50 pagesStockdale PDFRavi ShenkerNo ratings yet

- Manpower Development in VLSI Ni India: A Case Study: K.C.ShetDocument2 pagesManpower Development in VLSI Ni India: A Case Study: K.C.ShetpawanroyalNo ratings yet

- Budget Planner - Overview / Help: InstructionsDocument7 pagesBudget Planner - Overview / Help: InstructionspawanroyalNo ratings yet

- TECHNICAL SPECIFICATIONS FOR AN AIR TO AIR HEAT EXCHANGERDocument1 pageTECHNICAL SPECIFICATIONS FOR AN AIR TO AIR HEAT EXCHANGERpawanroyalNo ratings yet

- Insulation Block (Hysil) L B H Number of Hysil Block D (Diameter of Chamber)Document1 pageInsulation Block (Hysil) L B H Number of Hysil Block D (Diameter of Chamber)pawanroyalNo ratings yet

- Castable CalculationDocument4 pagesCastable CalculationpawanroyalNo ratings yet

- Cement Process Engineering Vade-Mecum: 3. QualityDocument22 pagesCement Process Engineering Vade-Mecum: 3. QualityRaúl Marcelo VelozNo ratings yet

- PR GRI P07-08 How To Optimise A Ball ChargeDocument6 pagesPR GRI P07-08 How To Optimise A Ball ChargepawanroyalNo ratings yet

- 02-1 Combustion and Fuels September 2010Document26 pages02-1 Combustion and Fuels September 2010pawanroyalNo ratings yet

- Responses to Empiricism and Structuralism in Social SciencesDocument13 pagesResponses to Empiricism and Structuralism in Social Sciencesphils_skoreaNo ratings yet

- B.Tech (ECE) Course Scheme & Syllabus as per CBCSDocument168 pagesB.Tech (ECE) Course Scheme & Syllabus as per CBCSRatsihNo ratings yet

- 65-1501 Victor Reguladores FlujometrosDocument7 pages65-1501 Victor Reguladores FlujometroscarlosNo ratings yet

- Dominos Winning StrategiesDocument185 pagesDominos Winning StrategiesY Ammar IsmailNo ratings yet

- Perpus Pusat Bab 1 Dan 2Document62 pagesPerpus Pusat Bab 1 Dan 2imam rafifNo ratings yet

- Paper ESEE2017 CLJLand MLDocument12 pagesPaper ESEE2017 CLJLand MLMatheus CardimNo ratings yet

- Solving Systems of Linear Equations in Two VariablesDocument13 pagesSolving Systems of Linear Equations in Two VariablesMarie Tamondong50% (2)

- Consumer Behavior Quiz (01-16-21)Document3 pagesConsumer Behavior Quiz (01-16-21)litNo ratings yet

- ST 30 PDFDocument2 pagesST 30 PDFafiffathin_akramNo ratings yet

- Ryan Ashby DickinsonDocument2 pagesRyan Ashby Dickinsonapi-347999772No ratings yet

- 2.5 PsedoCodeErrorsDocument35 pages2.5 PsedoCodeErrorsAli RazaNo ratings yet

- SP-1127 - Layout of Plant Equipment and FacilitiesDocument11 pagesSP-1127 - Layout of Plant Equipment and FacilitiesParag Lalit SoniNo ratings yet

- TS4F01-1 Unit 4 - Document ControlDocument66 pagesTS4F01-1 Unit 4 - Document ControlLuki1233332No ratings yet

- DLL Catch Up Friday Grade 4 Jan 19Document7 pagesDLL Catch Up Friday Grade 4 Jan 19reyannmolinacruz21100% (30)

- Plastiment BV40Document2 pagesPlastiment BV40the pilotNo ratings yet

- NSTP Law and ROTC RequirementsDocument47 pagesNSTP Law and ROTC RequirementsJayson Lucena82% (17)

- (Earth and Space Science (Science Readers) ) Greg Young-Alfred Wegener. Uncovering Plate Tectonics-Shell Education - Teacher Created Materials (2008)Document35 pages(Earth and Space Science (Science Readers) ) Greg Young-Alfred Wegener. Uncovering Plate Tectonics-Shell Education - Teacher Created Materials (2008)Peter GonzálezNo ratings yet

- UntitledDocument1 pageUntitledMoizur RahmanNo ratings yet

- Nozomi Networks Smart Polling Data SheetDocument4 pagesNozomi Networks Smart Polling Data SheetFlávio Camilo CruzNo ratings yet

- Z22 Double-Suction Axially-Split Single-Stage Centrifugal PumpDocument2 pagesZ22 Double-Suction Axially-Split Single-Stage Centrifugal Pumpmartín_suárez_110% (1)

- HXPM8XBBYY19065T2CDocument1 pageHXPM8XBBYY19065T2CЕвгений ГрязевNo ratings yet

- The Collector of Treasures - Long NotesDocument3 pagesThe Collector of Treasures - Long NotesAnimesh BhakatNo ratings yet

- Container Generator Qac Qec Leaflet EnglishDocument8 pagesContainer Generator Qac Qec Leaflet EnglishGem RNo ratings yet

- ICs Interface and Motor DriversDocument4 pagesICs Interface and Motor DriversJohn Joshua MontañezNo ratings yet

- ECSS E ST 32 10C - Rev.1 (6march2009) PDFDocument24 pagesECSS E ST 32 10C - Rev.1 (6march2009) PDFTomaspockNo ratings yet

- Optimization of Lignin Extraction from Moroccan Sugarcane BagasseDocument7 pagesOptimization of Lignin Extraction from Moroccan Sugarcane BagasseAli IrtazaNo ratings yet

- Concrete Strength Tester Water-Cement RatioDocument50 pagesConcrete Strength Tester Water-Cement RatioBartoFreitasNo ratings yet

- Training Catalog Piovan AcademyDocument24 pagesTraining Catalog Piovan AcademyKlein Louse AvelaNo ratings yet

- Acer Aspire 1710 (Quanta DT3) PDFDocument35 pagesAcer Aspire 1710 (Quanta DT3) PDFMustafa AkanNo ratings yet

- Tia PortalDocument46 pagesTia PortalAndré GomesNo ratings yet