Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Evidence Digests 3

Uploaded by

Grace Managuelod GabuyoOriginal Description:

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Evidence Digests 3

Uploaded by

Grace Managuelod GabuyoCopyright:

Available Formats

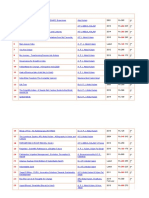

Ziegler v.

Moore 2

Zulueta v. CA 4

People v. Francisco 6

Regala v. Sandiganbayan 8

People v. Sandiganbayan 9

Barton v. Leyte Asphalt & Mineral Oil Co. 12

Mercado vs Vitriolo 14

Krohn v. CA 18

Gonzales v. CA 20

Almonte v. Vasquez 22

Neri v. Senate Committee on Accountability 23

Per Curiam Supreme Court Decision in connection with the letter of the House

Prosecution Panel to subpoena Justices of the Supreme Court 26

Banco Filipino v. Monetary Board 28

Air Philippines v. Penswell 31

Hoffman v. United States 33

Gutang v. People 35

People v. Invencion 38

Lee v. Court of Appeals 40

People v. Gaudia 42

People v. Lising 44

People v. Muit 47

Republic v. Bautista 49

People v. Sabagala 51

People v. Satorre 52

Boston Bank v. Manalo 53

People v. Bernal 55

Dallas Railway and Terminal v. Farnsworth 58

People v. Villacorta Gil 60

People v. Erguiza 64

Tamargo v. Awigan 65

Lejano v. People/ People vs Webb 68

ATENEO LAW 3-B EVIDENCE DIGESTS

BATCH 2017 1 ATTY. EUGENIO VILLAREAL

ZIEGLER V. MOORE

71 Nev. 91 (1059)

Digest Author: Angeline Ibuna

DOCTRINE

‣ The purpose of the Dead Man’s Rule is to prevent the living from obtaining unfair advantage because of death of

the other. Nor shall the living be entitled to the undue advantage of giving his own uncontradicted and

unexplained account of what transpired beyond possibility of contradiction by the decedent.

PARTIES

‣ Plaintiff: Zeigler – one who’s car got hit at the rear

‣ Defendant: Christ – one who hit Zeigler’s car

FACTS

‣ Zigler sued Al Christ for damages alleging that her automobile was struck in the rear by a car negligently operated

by Christ in August 1955 on Highway 40.

‣ Christ answered, denying negligence but admitting a collision between the two cars. He also pleaded Zeigler’s

contributory negligence.

‣ Christ died in May 1957 and Robert Moore (Robert) was substituted as his administrator before trial. At the trial

the court excluded under the dead man's rule certain testimony of Zeigler and of Zeigler’s witness, sheriff Delbert

Moore (Delbert).

‣ An insurance adjuster had taken statements from both Ziegler and the decedent, which statements were written

in longhand by the adjuster and signed by the parties.

‣ Zeigler moved under Rule 34 for an order for the production of these documents so that the same might be

inspected and copied, and assigns error and prejudice in the denial of such motion. (But court said the nature

and contents of the documents were part of court records so a denial of her motion would not be prejudicial to her.

Therefore, discussion on her assigned error is unnecessary)

‣ (It should be noted that Zeigler had been permitted to read the copies of the statements into the record for the

purpose of making an offer of proof. She then offered the copy of her own statement in evidence. An objection was

sustained on the ground that if her direct testimony was inadmissible under the dead man's rule her extrajudicial

statement was, a fortiori, inadmissible.)

‣ Delbert, sheriff of Humboldt County, testified that Christ, after the accident, had come to the office and made an

"accident report" and, in his conversation in making the report, talked to the witness "about how the accident

happened." He was then asked: "What did he tell you?" Objection on the ground "that this witness is rendered

incompetent under the dead man’s rule. This objection was sustained.

‣ The dead man's rule now appears, in pertinent part, in our codes as NRS 48.010 and 48.030, as follows:

‣ "48.010 1. All persons, without exception, otherwise than as specified in this chapter, who, having organs of sense,

can perceive, and perceiving can make known their perceptions to others, may be witnesses in any action or

proceeding in any court of the state. Facts which, by the common law, would cause the exclusion of witnesses, may

still be shown for the purpose of affecting their credibility. No person shall be allowed to testify:

1. When the other party to the transaction is dead.

2. When the opposite party to the action, * * * is the representative of a deceased person, when the facts to be proven

transpired before the death of such deceased person; * * *

‣ 48.030 The following persons cannot be witnesses: 3. Parties to an action * * * against an executor or administrator

upon a claim or demand against the estate of a deceased person, as to any matter of fact occurring before the death

of such deceased person."

‣ The error assigned in sustaining the objection to the testimony of sheriff Delbert as to statements made to him by

the decedent is well taken. The statutory exclusion of the testimony of witnesses under the sections above quoted

has been consistently held by this court not to apply to disinterested third persons. (Zeigler alleged that court

erred in sustaining the objection against Delbert’s Testimony under the Dead Man’s Rule. This court said the rule

does not apply to 3rd persons – in this case, Delbert).

ATENEO LAW 3-B EVIDENCE DIGESTS

BATCH 2017 2 ATTY. EUGENIO VILLAREAL

‣ Robert contends that even if the order excluding Delbert’s testimony was error, it could not possibly have

prejudiced Zeigler because the testimony of Delbert would have only established the fact that an accident occurred

without any inference of negligence.

‣ However, the court held that while it is true that this fact (fact of accident - Christ colliding with the rear of

Zeigler’s car) alone would not necessarily establish negligence on Christ's part, there can be no doubt that it would

constitute a part of such proof. The exclusion of the evidence was therefore prejudicial. New trial must be

ordered.

‣ Robert claims that at the trial, Zeigler was called as a witness in her own behalf to testify to the facts of the

accident and says that the question presented is “whether the survivor of an automobile accident can give

uncontradicted testimony as to the manner in which the collision occurred when the lips of the other party were

sealed by death.”

‣ Zeigler’s testified that at no time prior to the time of collision did she cause the brakes to be applied in a sudden

manner, nor did she indicate that she was going to make either a left or right turn, that her car was suddenly and

without warning hit from the rear.

‣ This offer of proof was objected to in its entirety and likewise denied in its entirety.

‣ Zeigler adds that her testimony is not an attemp to testify that Christ’s car was driven in a reckless manner or that

she is attempting to fix the blame or attach fault to anyone. She is merely testifying that she was driving down the

highway in the proper lane, at reasonable speed when he car was struck in the rear.

‣ Zeigler insists first in this respect that she is not precluded from testifying under NRS 48.010 (1) (a) because the

decedent cannot be said to be "the other party to the transaction" inasmuch as no "transaction" was involved; that

a tort action is not a transaction.

ISSUE/HELD

‣ WN Zeigler is precluded from testifying under the Dead Man’s Rule – NO.

RATIO

‣ Overwhelming weight of authority supports the rule that the dead man's statute applies to actions ex delicto and

that such actions are embraced within the statutory use of the word "transactions."

‣ In Warren v. DeLong, this court there held that the term "transaction" was broader than "contract" and broader

than "tort" and that it might include either or both.

‣ If then we apply the statute to tort actions as well as personal transactions between the parties the testimony of

the plaintiff was properly excluded under the holdings of this court in earlier cases, defining the purpose and

extent of the rule with reference to those matters which the decedent could have contradicted of his own

knowledge.

‣ By the same token, Zeigler’s testimony as to her medical bills, her pain and suffering and matters of like nature

which the decedent could not have contradicted of his own knowledge, was clearly admissible and the rejection of

such testimony was prejudicial error.

‣ Those items were entirely beyond the operation of the reasons for the rule of exclusion repeatedly enunciated by

this court: To prevent the living from obtaining unfair advantage because of death of the other. Nor shall the living

be entitled to the undue advantage of giving his own uncontradicted and unexplained account of what transpired

beyond possibility of contradiction by the decedent.

‣ The whole object of the code provision is to place the living and dead on terms of perfect equality, and, the dead

not being able to testify, the living shall not.

‣ In Bright v. Virginia and Gold Hill Water Co. The court here explained, the object of the statute is to prevent one

interested party from giving testimony when the other party's lips are sealed by death.

‣ Exception was given in Goldsworthy v. Johnson, But when the above stated reasons for the rule do not appear, this

court has not hesitated to admit in evidence the testimony of an interested party.

‣ Therefore the rule would not preclude plaintiff 's description of her own actions and the road conditions prior to

the point when within limitations of time or space the decedent could have contradicted her testimony of his own

knowledge.

ATENEO LAW 3-B EVIDENCE DIGESTS

BATCH 2017 3 ATTY. EUGENIO VILLAREAL

ZULUETA V. CA

G.R. No. 107383. February 20, 1996

Digest Author: Lizzie Lecaroz

DOCTRINE

‣ The intimacies between husband and wife do not justify any one of them in breaking the drawers and cabinets of

the other and in ransacking them for any telltale evidence of marital infidelity. A person, by contracting marriage,

does not shed his/her integrity or his right to privacy as an individual and the constitutional protection is ever

available to him or to her.

PARTIES

‣ Plaintiff/Private respondent: Alfredo Martin

‣ Defendant/Petitioner: Cecilia Zulueta

FACTS

‣ Petitioner Cecilia Zulueta is the wife of private respondent Alfredo Martin.

‣ On March 26, 1982, petitioner entered the clinic of her husband, a doctor of medicine, and in the presence of her

mother, a driver and private respondents secretary, forcibly opened the drawers and cabinet in her husband’s clinic

and took 157 documents consisting of private correspondence between Dr. Martin and his alleged paramours,

greetings cards, cancelled checks, diaries, Dr. Martins passport, and photographs. The documents and papers were

seized for use in evidence in a case for legal separation and for disqualification from the practice of medicine

which petitioner had filed against her husband.

‣ Dr. Martin brought this action below for recovery of the documents and papers and for damages against petitioner.

The case was filed with the Regional Trial Court of Manila, Branch X, which, after trial, rendered judgment for

private respondent, Dr. Alfredo Martin, declaring him the capital/exclusive owner of the properties described in

paragraph 3 of plaintiffs Complaint or those further described in the Motion to Return and Suppress and ordering

Cecilia Zulueta and any person acting in her behalf to immediately return the properties to Dr. Martin and to pay

him P5,000.00, as nominal damages; P5,000.00, as moral damages and attorneys fees; and to pay the costs of the

suit.

‣ The writ of preliminary injunction earlier issued was made final and petitioner Cecilia Zulueta and her attorneys

and representatives were enjoined from using or submitting/admitting as evidence the documents and papers in

question.

‣ On appeal, the Court of Appeals affirmed the decision of the Regional Trial Court.

ISSUE/HELD

‣ W/N the papers and documents are inadmissible in evidence-YES

RATIO

‣ Indeed the documents and papers in question are inadmissible in evidence. The constitutional injunction

declaring the privacy of communication and correspondence to be inviolable is no less applicable simply because it

is the wife (who thinks herself aggrieved by her husbands infidelity) who is the party against whom the

constitutional provision is to be enforced.

‣ The only exception to the prohibition in the Constitution is if there is a lawful order from a court or when

public safety or order requires otherwise, as prescribed by law. Any violation of this provision renders the

evidence obtained inadmissible for any purpose in any proceeding.

‣ The intimacies between husband and wife do not justify any one of them in breaking the drawers and cabinets of

the other and in ransacking them for any telltale evidence of marital infidelity. A person, by contracting marriage,

does not shed his/her integrity or his right to privacy as an individual and the constitutional protection is ever

available to him or to her.

‣ The law insures absolute freedom of communication between the spouses by making it privileged. Neither

husband nor wife may testify for or against the other without the consent of the affected spouse while the

marriage subsists. Neither may be examined without the consent of the other as to any communication received

in confidence by one from the other during the marriage, save for specified exceptions.

‣ Petitioner cited the case of Alfredo Martin v. Alfonso Felix, Jr., where the Court ruled that the documents and papers

were admissible in evidence and, therefore, their use by petitioner’s attorney, Alfonso Felix, Jr., did not constitute

malpractice or gross misconduct.

ATENEO LAW 3-B EVIDENCE DIGESTS

BATCH 2017 4 ATTY. EUGENIO VILLAREAL

‣ In this case however, when respondent refiled Cecilias case for legal separation before the Pasig Regional Trial

Court, there was admittedly an order of the Manila Regional Trial Court prohibiting Cecilia from using the

documents Annex A-I to J-7.

‣ Having appealed the said order to this Court on a petition for certiorari, this Court issued a restraining order on

aforesaid date which order temporarily set aside the order of the trial court. Hence, during the enforceability of

this Courts order, respondents request for petitioner to admit the genuineness and authenticity of the subject

annexes cannot be looked upon as malpractice.

‣ Notably, Dr. Martin finally admitted the truth and authenticity of the questioned annexes. At that point in

time, would it have been malpractice for Felix to use Martin’s admission as evidence against him in the legal

separation case pending in the Regional Trial Court of Makati.

‣ Significantly, Dr Martin’s admission was done not thru his counsel but by Dr. Martin himself under oath. Such

verified admission constitutes an affidavit, and, therefore, receivable in evidence against him. Martin became

bound by his admission.

‣ Thus, the acquittal of Atty. Felix, Jr. in the administrative case amounts to no more than a declaration that his

use of the documents and papers for the purpose of securing Dr. Martins admission as to their genuiness and

authenticity did not constitute a violation of the injunctive order of the trial court. By no means does the

decision in that case establish the admissibility of the documents and papers in question.

‣ If Atty. Felix, Jr. was acquitted of the charge of violating the writ of preliminary injunction issued by the trial

court, it was only because, at the time he used the documents and papers, enforcement of the order of the trial

court was temporarily restrained by this Court. The TRO issued by this Court was eventually lifted as the

petition for certiorari filed by petitioner against the trial courts order was dismissed and, therefore, the

prohibition against the further use of the documents and papers became effective again.

ATENEO LAW 3-B EVIDENCE DIGESTS

BATCH 2017 5 ATTY. EUGENIO VILLAREAL

PEOPLE V. FRANCISCO

G.R. No. L-568. July 16, 1947

Digest Author: Elwell Mariano

PARTIES

‣ Accused: Juan Francisco

FACTS

‣ Francisco, who had been previously arrested on charges of robbery was held as a detention prisoner in Mindoro.

‣ He requested permission from the chief to go home to see his wife about procurement of a bail. THis was

granted.

‣ Francisco was allowed to go home with sergeant Pacifico Pimintel to guard him.

‣ When the reached the house, sergeant Pimintel allowed Franciso to see his wife while sergeant remained at the

foot of the stairs.

‣ After a few moments, sergeant Pimintel heard the scream of a woman so went inside the house.

‣ He saw the wife of Francisco bleeding in her right breast. He also saw Francisco lying down with his little son

Romeo, aged one year and a half, lying in his breast.

‣ Francisco was wounded on his belly while his son was wounded and his back and is already dead.

‣ The prosecution, in recommending the capital punishment upon the accused, relies mainly on the:

1. Affidavit which is the virtual confession of the accused (exhibit C)

‣ This is signed and sworn to by Francisco

‣ It contains his admission that he stabbed his son and wife using a scissor and later on stabbed himself as

well. When he entered the house, he lost his senses because he remembered that his uncle told him that his

uncle would order someone to kill him.

2. The record made by the justice of peace of the arraignment where the defendant plead guilty. (Exhibit D)

3. The rebuttal testimony of the wife of Francisco

‣ Sergeant Pimintel testified that the accused confessed to him.

‣ The voluntariness and spontaneity of the confession contained in exhibit C was testified by the justice of the peace

and sergeant Pimintel.

‣ Furthermore, the statements of Francisco in said Exhibit C were corroborated by the testimony of his wife or

rebuttal.

ISSUE/HELD

1. W/N Exhibit C be given weight to convict Francisco- YES

2. W/N the testimony of Francisco’s wife is admissible despite the prohibition of sec. 26 (d) of Rule 123.- YES

RATIO FOR ISSUE 1

‣ As we construe the evidence, we believe that Exhibit C contains the truth, as narrated by the accused himself who,

at the time of making it, must have been moved only by the determination of a repentant father and husband to

acknowledge his guilt for acts which, though perhaps done under circumstances productive of a diminution of the

exercise of willpower, fell short of depriving the offender of consciousness of his acts.

‣ It was only after almost 1 year that Francisco repudiated his confession. As we find the confession to have been

given voluntarily, we feel justified in concluding that its subsequent repudiation by the accused almost a year

after must have been due to his fear of its consequences to himself, which he not improbably thought might cost

him his own life.

‣ Francisco said that his testimony on the said confession was only extracted from him through force but the Court

did not find sufficient evidence to destroy the categorical testimony of the justice of peace that Exhibit C was

signed by Francisco voluntarily and with full understanding.

ATENEO LAW 3-B EVIDENCE DIGESTS

BATCH 2017 6 ATTY. EUGENIO VILLAREAL

RATIO FOR ISSUE 2

‣ The rule contained in section 26 (d) of Rule 123 is an old one. Courts and textwriters on the subject have assigned

as reasons therefor the following:

1. Identity of interest;

2. The consequent danger of perjury;

3. The policy of the law which deems it necessary to guard the security and confidences of private life even at the

risk of an occasional failure of justice, and which rejects such evidence because its admission would lead to

domestic disunion and unhappiness; and,

4. Because where a want of domestic tranquility exists, there is danger of punishing one spouse through the

hostile testimony of the other.

‣ However, as all other general rules, this one has its own exceptions, both in civil actions between the spouses and

in criminal cases for offenses committed by one against the other. Like the rule itself, the exceptions are backed by

sound reasons which, in the excepted cases, outweigh those in support of the general rule. For instance, where the

marital and domestic relations are so strained that there is no more harmony to be preserved nor peace and

tranquility which may be disturbed, the reason based upon such harmony and tranquility fails. In such a case

identity of interests disappears and the consequent danger of perjury based on that identity is nonexistent.

Likewise, in such a situation, the security and confidences of private life which the law aims at protecting will be

nothing but ideals which, through their absence, merely leave a void in the unhappy home.

‣ It will be noted that the wife only testified against her husband after the latter, testifying in his own defense,

imputed upon her the killing of their little son. By all rules of justice and reason this gave the prosecution, which

had theretofore refrained from presenting the wife as a witness against her husband, the right to do so, as it did in

rebuttal; and to the wife herself the right to so testify, at least, in selfdefense, not, of course, against being

subjected to punishment in that case in which she was not a defendant but against any or all of various possible

consequences which might flow from her silence, namely: (1) a criminal prosecution against her which might be

instituted by the corresponding authorities upon the basis of her husband's aforesaid testimony; (2) in the moral

and social sense, her being believed by those who heard the testimony orally given, as well as by those who may

read the same, once put in writing, to be the killer of her infant child.

‣ By his said act, the husband—himself exercising the very right which he would deny to his wife upon the ground

of their marital relations—must be taken to have waived all objection to the latter's testimony upon rebuttal, even

considering that such objection would have been available at the outset.

‣ Waiver of Incompetency

‣ Objections to the competency of a husband or wife to testify in a criminal prosecution against the other may be

waived as in the case of the other witnesses generally. Thus, the accused waives his or her privilege by calling

the other spouse as a witness for him or her, thereby making the spouse subject to crossexamination in the

usual manner.

‣ It is also true that objection to the spouse's competency must be made when he or she is first offered as a

witness, and that the incompetency may be waived by the failure of the accused to make timely objection to

the admission of the spouse's testimony, although knowing of such incompetency, and the testimony

admitted, especially if the accused has assented to the admission, either expressly or impliedly

‣ Wharton (book author yata to na cited by the court)

‣ "Waiver of objection to incompetency.—A party may waive his objections to the competency of a witness and

permit him to testify. A party calling an incompetent witness as his own waives the incompetency. Also, if,

after such incompetency appears, there is failure to make timely objection, by a party having knowledge of the

incompetency, the objection will he deemed waived, whether it is on the ground of want of mental capacity or

for some other reason. If the objection could have been taken during the trial. a new trial will be refused and

the objection will not be available on writ of error. If, however, the objection of a party is overruled and the

ruling has been excepted to, the party may thereafter examine the witness upon the matters as to which he

was allowed to testify to without waiving his objections to the witness’s competency

‣ When the husband testified that it was his wife who caused the death of their son, he could not, let us repeat,

justly expect the State to keep silent and refrain from rebutting such new matter in his testimony, through the

only witness available, namely, the wife; nor could he legitimately seal his wife's lips and thus gravely expose her

to the danger of criminal proceedings against her being started by the authorities upon the strength and basis of

said testimony of her husband, or to bear the moral and social stigma of being thought, believed, or even just

suspected, to be the killer of her own offspring.

ATENEO LAW 3-B EVIDENCE DIGESTS

BATCH 2017 7 ATTY. EUGENIO VILLAREAL

REGALA V. SANDIGANBAYAN

ATENEO LAW 3-B EVIDENCE DIGESTS

BATCH 2017 8 ATTY. EUGENIO VILLAREAL

PEOPLE V. SANDIGANBAYAN

G.R. Nos. 115439-41. July 16, 1997 “Previous Ethics case: atty-client privilege”

Digest Author: Rose Anne Sy

DOCTRINE

‣ For the application of the attorney-client privilege, the period to be considered is the date when the privileged

communication was made by the client to the attorney in relation to either a crime committed in the past or with

respect to a crime intended to be committed in the future.

‣ The privileged confidentiality does not attach with regard to a crime which a client intends to commit thereafter

or in the future and for purposes of which he seeks the lawyer’s advice.

FACTS

‣ Respondents in the case:

1. Ceferino Paredes was successively the Provincial Attorney of Agusan del Sur then Governor of the same

province, and is at present a Congressman.

2. Atty. Generoso Sansaet was a practicing attorney who served as counsel for Paredes in several instances

pertinent to the criminal charges involved in this case.

3. Mansueto Honrada was the Clerk of Court and Acting Stenographer of the First Municipal Circuit Trial Court in

Agusan del Sur.

‣ Paredes applied for a free patent over a lot of the Rosario Public Land Subdivision Survey. His application was

approved and, pursuant to a free patent granted to him, an original certificate of title was issued in his favor for

that lot which is situated in the poblacion of San Francisco, Agusan del Sur.

‣ The Director of Lands filed an action for the cancellation of Paredes’ patent and certificate of title since the land

had been designated and reserved as a school site in the aforementioned subdivision survey.

‣ TC: nullified patent and title after finding that Paredes had obtained the same through fraudulent

misrepresentations in his application. Pertinently, Sansaet served as counsel of Paredes in that civil case.

‣ An information for perjury was filed against Paredes in the Municipal Circuit Trial Court. Provincial Fiscal was,

however, directed by the Deputy Minister of Justice to move for the dismissal of the case on the ground inter alia of

prescription, hence the proceedings were terminated. In this criminal case, Paredes was likewise represented by

Sansaet as counsel.

‣ Nonetheless, Paredes was thereafter haled before the Tanodbayan for preliminary investigation on the charge

that, by using his former position as Provincial Attorney to influence and induce the Bureau of Lands officials to

favorably act on his application for free patent, he had violated Section 3(a) of Republic Act No. 3019 (Anti-Graft

and Corrupt Practices Act). For the third time, Sansaet was Paredes’ counsel of record.

‣ A criminal case was subsequently filed with the Sandiganbayan charging Paredes with a violation of Section 3(a)

of RA 3019. However, a motion to quash filed by the defense was later granted and the case was dismissed on the

ground of prescription.

‣ Teofilo Gelacio, a taxpayer who had initiated the perjury and graft charges against Paredes, sent a letter to the

Ombudsman seeking the investigation of the three respondents for falsification of public documents.

‣ He claimed that Honrada, in conspiracy with his co respondents, simulated and certified as true copies certain

documents purporting to be a notice of arraignment and transcripts of stenographic notes supposedly taken

during the arraignment of Paredes on the perjury charge. These falsified documents were annexed to Paredes’

MR of the Tanodbayan resolution for the filing of a graft charge against him, in order to support his contention

that the same would constitute double jeopardy.

‣ In support of his claim, he attached to his letter a certification that no notice of arraignment was ever received

by the Office of the Provincial Fiscal of Agusan del Sur in connection with that perjury case; and a certification

of Presiding Judge that said perjury case in his court did not reach the arraignment stage since action thereon

was suspended pending the review of the case by the DOJ.

‣ IMPT: Respondents filed their respective counter-affidavits, but Sansaet subsequently discarded and repudiated

the submissions he had made in his counter-affidavit. In a so-called Affidavit of Explanations and

Rectifications, Sansaet revealed that Paredes contrived to have the graft case under preliminary investigation

dismissed on the ground of double jeopardy by making it that the perjury case had been dismissed by the trial

court after he had been arraigned therein.

ATENEO LAW 3-B EVIDENCE DIGESTS

BATCH 2017 9 ATTY. EUGENIO VILLAREAL

‣ For that purpose, the documents which were later filed by Sansaet in the preliminary investigation were prepared

and falsified by his co-respondents in this case in the house of Paredes. To evade responsibility for his own

participation in the scheme, he claimed that he did so upon the instigation and inducement of Paredes. This was

intended to pave the way for his discharge as a government witness in the consolidated cases, as in fact a motion

therefor was filed by the prosecution pursuant to their agreement.

‣ The Ombudsman approved the filing of falsification charges against all the respondents. The proposal for the

discharge of respondent Sansaet as a state witness was rejected by the Ombudsman on this evaluative legal

position:

‣ Taking his explanation, it is difficult to believe that a lawyer of his stature, in the absence of deliberate intent to

conspire, would be unwittingly induced by another to commit a crime. As counsel for the accused in those criminal

cases, Atty. Sansaet had control over the case theory and the evidence which the defense was going to present.

Moreover, the testimony or confession of Atty. Sansaet falls under the mantle of privileged communication between

the lawyer and his client which may be objected to, if presented in the trial.

‣ The Ombudsman refused to reconsider that resolution and decided to file separate informations for falsification

of public documents against each of the respondents. Thus, three criminal cases were filed in the graft court.

However, the same were consolidated for joint trial in the Second Division of the Sandiganbayan.

‣ A motion was filed by the People for the discharge of respondent Sansaet as a state witness. It was submitted

that all the requisites therefor, as provided in Section 9, Rule 119 of the Rules of Court, were satisfied insofar as

respondent Sansaet was concerned.

‣ The basic postulate was that, except for the eyewitness testimony of respondent Sansaet, there was no

other direct evidence to prove the confabulated falsification of documents by respondents Honrada and

Paredes.

‣ Unfortunately for the prosecution, Sandiganbayan, hewing to the theory of the attorney-client privilege adverted

to by the Ombudsman and invoked by the two other private respondents in their opposition to the prosecutions

motion, resolved to deny the desired discharge on this ratiocination:

‣ From the evidence adduced, the opposition was able to establish that client and lawyer relationship existed

between Atty. Sansaet and Ceferino Paredes, Jr., before, during and after the period alleged in the information. In

view of such relationship, the facts surrounding the case, and other confidential matter must have been

disclosed by accused Paredes, as client, to accused Sansaet, as his lawyer in his professional capacity. Therefore,

the testimony of Atty. Sansaet on the facts surrounding the offense charged in the information is privileged.

ISSUE/HELD

‣ W/N the projected testimony of respondent Sansaet, as proposed state witness, is barred by the attorney-client

privilege - No.

RATIO

‣ As already stated, Sandiganbayan ruled that due to the lawyer-client relationship which existed between herein

respondents Paredes and Sansaet during the relevant periods, the facts surrounding the case and other

confidential matters must have been disclosed by Paredes, as client to Sansaet, as his lawyer. Accordingly, it found

no reason to discuss it further since Atty. Sansaet cannot be presented as a witness against accused Paredes

without the latter’s consent.

‣ The Court is of a contrary persuasion. The attorney-client privilege cannot apply in these cases, as the facts thereof

and the actuations of both respondents therein constitute an exception to the rule.

‣ It may correctly be assumed that there was a confidential communication made by Paredes to Sansaet in

connection with the criminal cases for falsification, and this may reasonably be expected since Paredes was the

accused and Sansaet his counsel. Indeed, the fact that Sansaet was called to witness the preparation of the falsified

documents by Paredes and Honrada was as eloquent a communication, if not more, than verbal statements being

made to him by Paredes as to the fact and purpose of such falsification. It is significant that the evidentiary rule

on this point has always referred to any communication, without distinction or qualification.

‣ In the American jurisdiction from which our present evidential rule was taken, there is no particular mode by

which a confidential communication shall be made by a client to his attorney. The privilege is not confined to

verbal or written communications made by the client to his attorney but extends as well to information

communicated by the client to the attorney by other means.

‣ Nor can it be pretended that during the entire process, considering their past and existing relations, no word at all

passed between Paredes and Sansaet on the subject matter of that criminal act. The clincher for this conclusion is

the undisputed fact that documents were thereafter filed by Sansaet in behalf of Paredes as annexes to the MR in

ATENEO LAW 3-B EVIDENCE DIGESTS

BATCH 2017 10 ATTY. EUGENIO VILLAREAL

the preliminary investigation of the graft case before the Tanodbayan. Also, the acts and words of the parties

during the period when the documents were being falsified were necessarily confidential since Paredes would not

have invited Sansaet to his house and allowed him to witness the same except under conditions of secrecy and

confidence.

‣ A distinction must be made between confidential communications relating to past crimes already committed, and

future crimes intended to be committed, by the client. Corollarily, it is admitted that the announced intention of

a client to commit a crime is not included within the confidences which his attorney is bound to respect.

‣ The CA appears, however, to inaccurately believe that in the instant case it is dealing with a past crime, and that

respondent Sansaet is set to testify on alleged criminal acts of Paredes and Honrada that have already been

committed and consummated. For the application of the attorney-client privilege, the period to be considered is

the date when the privileged communication was made by the client to the attorney in relation to either a

crime committed in the past or with respect to a crime intended to be committed in the future. In other words,

if the client seeks his lawyer’s advice with respect to a crime that the former has theretofore committed, he is

given the protection of a virtual confessional seal which the attorney-client privilege declares cannot be broken by

the attorney without the clients consent. The same privileged confidentiality, however, does not attach with

regard to a crime which a client intends to commit thereafter or in the future and for purposes of which he

seeks the lawyer’s advice.

‣ Statements and communications regarding the commission of a crime already committed, made by a party who

committed it, to an attorney, consulted as such, are privileged communications. Contrarily, the unbroken stream

of judicial dicta is to the effect that communications between attorney and client having to do with the clients

contemplated criminal acts, or in aid or furtherance thereof, are not covered by the cloak of privileges ordinarily

existing in reference to communications between attorney and client.

‣ In the present cases, the testimony sought to be elicited from Sansaet as state witness are the communications

made to him by physical acts and/or accompanying words of Paredes at the time he and Honrada, either with the

active or passive participation of Sansaet, were about to falsify, or in the process of falsifying, the documents

which were later filed in the Tanodbayan by Sansaet and culminated in the criminal charges now pending in

respondent Sandiganbayan. Clearly, therefore, the confidential communications thus made by Paredes to

Sansaet were for purposes of and in reference to the crime of falsification which had not yet been committed

in the past by Paredes but which he, in confederacy with his present co-respondents, later committed. Having

been made for purposes of a future offense, those communications are outside the pale of the attorney-client

privilege.

‣ Furthermore, Sansaet was himself a conspirator in the commission of that crime of falsification which he, Paredes

and Honrada concocted and foisted upon the authorities. It is well settled that in order that a communication

between a lawyer and his client may be privileged, it must be for a lawful purpose or in furtherance of a lawful

end. The existence of an unlawful purpose prevents the privilege from attaching. In fact, it has also been pointed

out to the Court that the prosecution of the honorable relation of attorney and client will not be permitted under

the guise of privilege, and every communication made to an attorney by a client for a criminal purpose is a

conspiracy or attempt at a conspiracy which is not only lawful to divulge, but which the attorney under certain

circumstances may be bound to disclose at once in the interest of justice.

‣ It is evident, therefore, that it was error for respondent Sandiganbayan to insist that such unlawful

communications intended for an illegal purpose contrived by conspirators are nonetheless covered by the so-

called mantle of privilege. To prevent a conniving counsel from revealing the genesis of a crime which was later

committed pursuant to a conspiracy, because of the objection thereto of his conspiring client, would be one of the

worst travesties in the rules of evidence and practice in the noble profession of law.

Other stuff about State Witnesses:

‣ The Court is reasonably convinced that the other requisites for the discharge of Sansaet as a state witness are

present and should have been favorably appreciated by the Sandiganbayan.

‣ Sansaet is the only cooperative eyewitness to the actual commission of the falsification charged in the criminal

cases pending before respondent court, and the prosecution is faced with the formidable task of establishing the

guilt of the two other co-respondents who steadfastly deny the charge and stoutly protest their innocence. There

is thus no other direct evidence available for the prosecution of the case, hence there is absolute necessity for the

testimony of Sansaet whose discharge is sought precisely for that purpose. Said respondent has indicated his

conformity thereto and has, for the purposes required by the Rules, detailed the substance of his projected

testimony in his Affidavit of Explanations and Rectifications.

ATENEO LAW 3-B EVIDENCE DIGESTS

BATCH 2017 11 ATTY. EUGENIO VILLAREAL

BARTON V. LEYTE ASPHALT & MINERAL OIL CO.

“Kalaban got a letter between the lawyer and client, and used it against them.” GR No. L-2137

Digest Author: Johnny T

DOCTRINE

‣ The preservation of secrecy of communication is entirely in the hands of the client, when it comes to an atty -

client relationship. Thus those who are bound by this are under a duty not to violate it. BUT this DOES NOT extend

to 3rd persons - even if they surreptitiously (sneaky sneaky) read or obtained possession of it.

PARTIES

‣ Barton – US citizen, who resides in manila

‣ Leyte – Defendant Corporation with valuable deposit of bituminous limestone and other asphalt products, located

on the Island of Leyte and known as the Lucio mine.

FACTS

‣ Leyte Asphalt Company. is the owner of a valuable deposit of asphalt products, located on the Island of Leyte. On

April 21, 1920, the company, addressed a letter to Barton, authorizing him to sell their products in Australia and

New Zealand

‣ On April 21, 1920, William Anderson, as president and general manager of the Leyte addressed to Barton,

authorizing the latter to sell the products of the Lucio mine in the Commonwealth of Australia and New Zealand

upon a scale of prices indicated in said letter. The letter stated that Barton would be the sole an exclusive sales

agency for bituminous limestone.

‣ After this contract was executed, Barton also asked to be the exclusive sales agent in Japan. The Company replied

that they would give him the same commissions as those that he is making in Australia, BUT it would not give him

exclusive agency since there were others that were saying that they could also sell in Japan.

‣ Meanwhile Barton had embarked for San Francisco and upon arriving at that port he entered into an agreement

with Ludvigsen & McCurdy, of that city, whereby said firm was constituted a subagent and given the sole selling

rights for the bituminous limestone products of the defendant company for the period of one year from November

11, 1920

‣ Barton alleges that during the life of the agency indicated in Exhibit B, he rendered services to the Leyte in the way

of advertising and demonstrating the products and expended large sums of money in visiting arious parts of the

world for the purpose of carrying on said advertising and demonstrations, in shipping to various parts of the

world samples of the products of Leyte, and in otherwise carrying on advertising work. For these services and

expenditures Barton sought to recover the sum of $16,563.80. Which he claims to recover as expenses.

‣ During trial, the Company offered in evidence a carbon copy of a letter dated June 13, 1921, written by Barton to

his attorney, Frank Ingersoll about his profits. In this case he said that his profits should be 85 cents per ton

(which was less than what he was claiming). The authenticity of this city document is admitted, and was offered

in evidence by the attorney of Leyte company.

‣ The counsel of Barton then announced that he had no objection to the introduction of this evidence if counsel for

the Company would explain where this copy was secured. Upon this the attorney for the Company informed the

court that he received the letter from the former attorneys of the Barton without explanation of the manner in

which the document had come into their possession.

‣ The lawyer of Barton then threatened that unless there was explanation of how such letter came into the

possession of the company, they would object to its introduction on the ground of the attorney-client privilege. As

the counsel for the company failed to explain, the counsel of Barton objected to the introduction, and was

sustained by the trial court judge. ( So the letter was not admitted)

ISSUE/HELD

‣ W/N the court in error for EXCLUDING the document? YES (Note: The lower court excluded the document on the

ground that it was privileged communication.)

RATIO

‣ We are of the opinion that this ruling was erroneous; for even supposing that the letter was within the privilege

which protects communications between attorney and client, this privilege was lost when the letter came to the

hands of the adverse party. And it makes no difference how the adversary acquired possession. The law protects

the client from the effect of disclosures made by him to his attorney in the confidence of the legal relation, but

ATENEO LAW 3-B EVIDENCE DIGESTS

BATCH 2017 12 ATTY. EUGENIO VILLAREAL

when such a document, containing admissions of the client, comes to the hand of a third party, and reaches the

adversary, it is admissible in evidence.

‣ The law provides subjective freedom for the client by assuring him of exemption from its processes of disclosure

against himself or the attorney or their agents of communication. This much, but not a whit more, is necessary for

the maintenance of the privilege. Since the means of preserving secrecy of communication are entirely in the

client's hands, and since the privilege is a derogation from the general testimonial duty and should be strictly

construed, it would be improper to extend its prohibition to third persons who obtain knowledge of the

communications. One who overhears the communication, whether with or without the client's knowledge, is not

within the protection of the privilege. The same rule ought to apply to one who surreptitiously reads or obtains

possession of a document in original or copy.

‣ Although the precedents are somewhat confusing, the better doctrine is to the effect that when papers are offered

in evidence a court will take no notice of how they were obtained, whether legally or illegally, properly or

improperly; nor will it form a collateral issue to try that question.

‣ Digest Author’s Note: The main facts of the case detail various international transactions that Barton did on behalf of

Leyte. There is a super long and complicated discussion of this in the original. I did not add it here kasi its more

international commercial transactions than evid.

ATENEO LAW 3-B EVIDENCE DIGESTS

BATCH 2017 13 ATTY. EUGENIO VILLAREAL

MERCADO VS VITRIOLO

A.C. No. 5108 May 26, 2005

Digest Author: Clarence Tiu

DOCTRINE

‣ Where legal advice of any kind is sought from a professional legal adviser in his capacity as such, the

communications relating to that purpose, made in confidence by the client, are at his instance permanently

protected from disclosure by himself or by the legal advisor except the protection be waived.

‣ Factor of the Rule on Attorney-Client Privilege

1. There exists an attorney-client relationship, or a prospective attorney-client relationship, and it is by reason of

this relationship that the client made the communication.

2. The client made the communication in confidence

3. The legal advice must be sought from the attorney in his professional capacity

PARTIES

‣ Complainant: Rosa Mercado, a client of the respondent

‣ Respondent: Atty. Julito Vitriolo, a Deputy Executive Director of the Commission on Higher Education (CHED)

FACTS

‣ Mercado is a Senior Education Program Specialist of the Standards Development Division, Office of Programs and

Standards while respondent is a Deputy Executive Director IV of the Commission on Higher Education (CHED)

‣ Mercado's husband filed a case for annulment of their marriage with the RTC of Pasig City.

‣ Later, the counsel of Mercado, died. Thus, Atty. Vitriolo entered his appearance before the trial court as

collaborating counsel for complainant.

‣ Eventually, this annulment case had been dismissed by the trial court, and the dismissal became final and

executory

‣ Atty. Vitriolo filed a criminal action against Mercado before the Office of the City Prosecutor, Pasig City for

violation of Articles 171 and 172 (falsification of public document) of the RPC.

‣ Vitriolo alleged that Mercado made false entries in the Certificates of Live Birth of her children and allegedly

indicated in said Certificates of Live Birth that she is married to a certain Ferdinand Fernandez, when in truth,

she is legally married to Ruben G. Mercado and their marriage

‣ In her defense, Mercado denied the accusations of Vitriolo against her. She denied using any other name than

"Rosa F. Mercado." She also insisted that she has gotten married only once, to Ruben G. Mercado. She also cited

other charges against Vitriolo that are pending before or decided upon by other tribunals

1. Libel suit before the Office of the City Prosecutor, Pasig City

Administrative case for dishonesty, grave misconduct, conduct prejudicial to the best interest of the service,

pursuit of private business, vocation or profession without the permission required by Civil Service rules and

regulations, and violations of the "Anti-Graft and Corrupt Practices Act," before the then Presidential

Commission Against Graft and Corruption

2. Complaint for dishonesty, grave misconduct, and conduct prejudicial to the best interest of the service before

the Office of the Ombudsman, where he was found guilty of misconduct and meted out the penalty of one

month suspension without pay

3. The Information for violation of Section 7(b)(2) of Republic Act No. 6713, as amended, otherwise known as the

Code of Conduct and Ethical Standards for Public Officials and Employees before the Sandiganbayan

‣ Also, Rosa F. Mercado filed an administrative complaint against Atty. Julito D. Vitriolo, seeking his disbarment

from the practice of law with the Supreme Court. The complainant alleged that respondent Vitriolo maliciously

instituted a criminal case for falsification of public document against her, a former client, based on confidential

information gained from their attorney-client relationship.

‣ Mercado alleged that said criminal complaint for falsification of public document disclosed confidential facts

and information relating to the civil case for annulment, then handled by Vitriolo as her counsel. This

prompted complainant Mercado to bring this action against respondent. She claims that, in filing the criminal

ATENEO LAW 3-B EVIDENCE DIGESTS

BATCH 2017 14 ATTY. EUGENIO VILLAREAL

case for falsification, respondent is guilty of breaching their privileged and confidential lawyer-client

relationship, and should be disbarred.

‣ Respondent filed his Comment/Motion to Dismiss where he alleged that:

1. The complaint for disbarment was all hearsay, misleading and irrelevant because all the allegations leveled

against him are subject of separate fact-finding bodies

2. The pending cases against him are not grounds for disbarment, and that he is presumed to be innocent until

proven otherwise.

3. The decision of the Ombudsman finding him guilty of misconduct and imposing upon him the penalty of

suspension for one month without pay is on appeal with the Court of Appeals. He adds that he was found

guilty, only of simple misconduct, which he committed in good faith.

4. His filing of the criminal complaint for falsification of public documents against complainant does not violate

the rule on privileged communication between attorney and client because the bases of the falsification case

are two certificates of live birth which are public documents and in no way connected with the confidence

taken during the engagement of respondent as counsel. According to respondent, the complainant confided to

him as then counsel only matters of facts relating to the annulment case. Nothing was said about the alleged

falsification of the entries in the birth certificates of her two daughters. The birth certificates are filed in the

Records Division of CHED and are accessible to anyone.

‣ The SC referred the administrative case to the Integrated Bar of the Philippines (IBP) for investigation, report and

recommendation

‣ The IBP Commission on Bar Discipline set two dates for hearing but complainant failed to appear in both. The

Investigating Commissioner thus granted respondent's motion to file his memorandum, and the case was

submitted for resolution based on the pleadings submitted by the parties.

‣ Subsequently, the IBP Board of Governors approved the report of investigating commissioner Datiles, finding the

respondent guilty of violating the rule on privileged communication between attorney and client, and

recommending his suspension from the practice of law for one (1) year.

‣ Complainant, upon receiving a copy of the IBP report and recommendation, wrote Chief Justice Hilario Davide, Jr.,

a letter of desistance. She stated that after the passage of so many years, she has now found forgiveness for those

who have wronged her.

ISSUES/RATIO

1. W/N the complainant’s letter of desistance is a ground to absolve the respondent from guilt- NO

2. W/N the respondent violated the rule on privileged communication between attorney and client when he filed a

criminal case for falsification of public document against his former client- NO, the complaint was

unsubstantiated

RATIO FOR ISSUE 1

‣ The Court is not bound by any withdrawal of the complaint or desistance by the complainant. The letter of

complainant to the Chief Justice imparting forgiveness upon respondent is inconsequential in disbarment

proceedings.

RATIO FOR ISSUE 2

‣ Discussion on the nature of the relationship between attorney and client and the rule on attorney-client privilege

that is designed to protect such relation

‣ In engaging the services of an attorney, the client reposes on him special powers of trust and confidence. Their

relationship is strictly personal and highly confidential and fiduciary.

‣ The relation is of such delicate, exacting and confidential nature that is required by necessity and public

interest.

‣ Only by such confidentiality and protection will a person be encouraged to repose his confidence in an

attorney. The hypothesis is that abstinence from seeking legal advice in a good cause is an evil which is fatal to

the administration of justice.Thus, the preservation and protection of that relation will encourage a client to

entrust his legal problems to an attorney, which is of paramount importance to the administration of justice.

‣ One rule adopted to serve this purpose is the attorney-client privilege: an attorney is to keep inviolate his

client's secrets or confidence and not to abuse them.Thus, the duty of a lawyer to preserve his client's secrets

and confidence outlasts the termination of the attorney-client relationship, and continues even after the

client's death.

ATENEO LAW 3-B EVIDENCE DIGESTS

BATCH 2017 15 ATTY. EUGENIO VILLAREAL

‣ It is the glory of the legal profession that its fidelity to its client can be depended on, and that a man may safely

go to a lawyer and converse with him upon his rights or supposed rights in any litigation with absolute

assurance that the lawyer's tongue is tied from ever disclosing it.With full disclosure of the facts of the case by

the client to his attorney, adequate legal representation will result in the ascertainment and enforcement of

rights or the prosecution or defense of the client's cause.

‣ On the rule of Attorney-Client Privilege, . Dean Wigmore cites the factors essential to establish the existence of the

privilege: “Where legal advice of any kind is sought from a professional legal adviser in his capacity as such, the

communications relating to that purpose, made in confidence by the client, are at his instance permanently protected

from disclosure by himself or by the legal advisor except the protection be waived.”

‣ In fine, the factors are as follows:

1. There exists an attorney-client relationship, or a prospective attorney-client relationship, and it is by

reason of this relationship that the client made the communication

‣ Matters disclosed by a prospective client to a lawyer are protected by the rule on privileged communication

even if the prospective client does not thereafter retain the lawyer or the latter declines the employment.

‣ The reason for this is to make the prospective client free to discuss whatever he wishes with the lawyer

without fear that what he tells the lawyer will be divulged or used against him, and for the lawyer to be

equally free to obtain information from the prospective client.

‣ On the other hand, a communication from a (prospective) client to a lawyer for some purpose other than on

account of the (prospective) attorney-client relation is not privileged.

‣ Instructive is the case of Pfleider v. Palanca,where the client and his wife leased to their attorney a 1,328-hectare

agricultural land for a period of ten years. In their contract, the parties agreed, among others, that a specified

portion of the lease rentals would be paid to the client-lessors, and the remainder would be delivered by counsel-

lessee to client's listed creditors. The client alleged that the list of creditors which he had "confidentially" supplied

counsel for the purpose of carrying out the terms of payment contained in the lease contract was disclosed by

counsel, in violation of their lawyer-client relation, to parties whose interests are adverse to those of the client.

As the client himself, however, states, in the execution of the terms of the aforesaid lease contract between the

parties, he furnished counsel with the "confidential" list of his creditors. We ruled that this indicates that client

delivered the list of his creditors to counsel not because of the professional relation then existing between them,

but on account of the lease agreement. We then held that a violation of the confidence that accompanied the

delivery of that list would partake more of a private and civil wrong than of a breach of the fidelity owing from a

lawyer to his client.

2. The client made the communication in confidence

‣ The mere relation of attorney and client does not raise a presumption of confidentiality. The client must

intend the communication to be confidential.

‣ A confidential communication refers to information transmitted by voluntary act of disclosure between

attorney and client in confidence and by means which, so far as the client is aware, discloses the

information to no third person other than one reasonably necessary for the transmission of the

information or the accomplishment of the purpose for which it was given.

‣ Our jurisprudence on the matter rests on quiescent ground. Thus, a compromise agreement prepared by a

lawyer pursuant to the instruction of his client and delivered to the opposing party, an offer and counter-

offer for settlement, or a document given by a client to his counsel not in his professional capacity, are not

privileged communications, the element of confidentiality not being present.

3. The legal advice must be sought from the attorney in his professional capacity

‣ The communication made by a client to his attorney must not be intended for mere information, but for the

purpose of seeking legal advice from his attorney as to his rights or obligations. The communication must

have been transmitted by a client to his attorney for the purpose of seeking legal advice.

‣ If the client seeks an accounting service, or business or personal assistance, and not legal advice, the

privilege does not attach to a communication disclosed for such purpose

‣ Applying all these rules to the case at bar, we hold that the evidence on record fails to substantiate

complainant's allegations, as shown by the following:

1. The complainant did not even specify the alleged communication in confidence disclosed by respondent. All

her claims were couched in general terms and lacked specificity.

ATENEO LAW 3-B EVIDENCE DIGESTS

BATCH 2017 16 ATTY. EUGENIO VILLAREAL

2. She contends that respondent violated the rule on privileged communication when he instituted a criminal

action against her for falsification of public documents because the criminal complaint disclosed facts relating

to the civil case for annulment then handled by respondent. She did not, however, spell out these facts which

will determine the merit of her complaint.

3. Complainant failed to attend the hearings at the IBP.

‣ Without any testimony from the complainant as to the specific confidential information allegedly divulged

by respondent without her consent, it is difficult, if not impossible to determine if there was any violation of

the rule on privileged communication. Such confidential information is a crucial link in establishing a breach

of the rule on privileged communication between attorney and client. It is not enough to merely assert the

attorney-client privilege. The burden of proving that the privilege applies is placed upon the party asserting

the privilege The Court cannot be involved in a guessing game as to the existence of facts which the

complainant must prove.

ATENEO LAW 3-B EVIDENCE DIGESTS

BATCH 2017 17 ATTY. EUGENIO VILLAREAL

KROHN V. CA

G.R. No. 108854; June 14, 1994

Digest Author: Helen Toledo

PARTIES

‣ Petitioner - Ma. Paz Fernandez Krohn

‣ Respondents - Court Of Appeals and Edgar Krohn, Jr.

FACTS

‣ A confidential psychiatric evaluation report is being presented in evidence before the trial court in a petition for

annulment of marriage grounded on psychological incapacity. The witness testifying on the report is the husband

who initiated the annulment proceedings, not the physician who prepared the report.

‣ The subject of the evaluation report, Ma. Paz Fernandez Krohn, invoking the rule on privileged communication

between physician and patient, seeks to enjoin her husband from disclosing the contents of the report.

‣ In 1964, Edgar Krohn, Jr., and Ma. Paz Fernandez were married. They had three children. Their blessings

notwithstanding, the relationship between the couple developed into a stormy one. Ma. Paz underwent

psychological testing purportedly in an effort to ease the marital strain. The effort however proved futile until

they finally separated in fact.

‣ Edgar was able to secure a copy of the confidential psychiatric report on Ma. Paz prepared and signed by Drs.

Cornelio Banaag, Jr., and Baltazar Reyes. In 1978, presenting the report among others, he obtained a decree

("Conclusion") from the Tribunal Metropolitanum Matrimoniale in Manila nullifying his church marriage with Ma.

Paz on the ground of "incapacitas assumendi onera conjugalia due to lack of due discretion existent at the time of

the wedding and thereafter." The decree was later confirmed and pronounced "Final and Definite."

‣ Meanwhile, the then CFI (now RTC) of Pasig, Br. II, issued an order granting the voluntary dissolution of the

conjugal partnership.

‣ In 1990, Edgar filed a petition for the annulment of his marriage with Ma. Paz before the trial court. In his

petition, he cited the Confidential Psychiatric Evaluation Report which Ma. Paz merely denied in her Answer as

"either unfounded or irrelevant."

‣ At the hearing, Edgar took the witness stand and tried to testify on the contents of the Confidential Psychiatric

Evaluation Report. This was objected to on the ground that it violated the rule on privileged communication

between physician and patient. Subsequently, Ma. Paz filed a Manifestation expressing her "continuing objection"

to any evidence, oral or documentary, "that would thwart the physician-patient privileged communication rule,"

and thereafter submitted a Statement for the Record asserting among others that "there is no factual or legal basis

whatsoever for petitioner (Edgar) to claim 'psychological incapacity' to annul their marriage, such ground being

completely false, fabricated and merely an afterthought."

‣ The trial court issued an Order admitting the Confidential Psychiatric Evaluation Report in evidence and ruling

that respondent did not object thereto on the ground of the supposed privileged communication between patient

and physician but rather that it was irrelevant.

ISSUE/HELD

‣ Whether or not the Report is admissible – YES, since the prohibition does not apply to the husband.

RATIO

‣ Petitioner argues that since Sec. 24, par. (c), Rule 130, of the Rules of Court prohibits a physician from testifying on

matters which he may have acquired in attending to a patient in a professional capacity, "WITH MORE REASON

should be third person (like respondent-husband in this particular instance) be PROHIBITED from testifying on

privileged matters between a physician and patient or from submitting any medical report, findings or evaluation

prepared by a physician which the latter has acquired as a result of his confidential and privileged relation with a

patient."

‣ She further argues that to allow her husband to testify on the contents of the psychiatric evaluation report "will

set a very bad and dangerous precedent because it abets circumvention of the rule's intent in preserving the

sanctity, security and confidence to the relation of physician and his patient." Her thesis is that what cannot be

done directly should not be allowed to be done indirectly.

‣ Private respondent Edgar Krohn, Jr., however contends that "the rules are very explicit: the prohibition applies

only to a physician. Thus . . . the legal prohibition to testify is not applicable to the case at bar where the person

sought to be barred from testifying on the privileged communication is the husband and not the physician of the

ATENEO LAW 3-B EVIDENCE DIGESTS

BATCH 2017 18 ATTY. EUGENIO VILLAREAL

petitioner." In fact, according to him, the Rules sanction his testimony considering that a husband may testify

against his wife in a civil case filed by one against the other.

‣ Besides, private respondent submits that privileged communication may be waived by the person entitled thereto,

and this petitioner expressly did when she gave her unconditional consent to the use of the psychiatric evaluation

report when it was presented to the Tribunal Metropolitanum Matrimoniale which took it into account among

others in deciding the case and declaring their marriage null and void. Private respondent further argues that

petitioner also gave her implied consent when she failed to specifically object to the admissibility of the report in

her Answer where she merely described the evaluation report as "either unfounded or irrelevant." At any rate,

failure to interpose a timely objection at the earliest opportunity to the evidence presented on privileged matters

may be construed as an implied waiver.

‣ The treatise presented by petitioner on the privileged nature of the communication between physician and

patient, as well as the reasons therefor, is not doubted. Indeed, statutes making communications between

physician and patient privileged are intended to inspire confidence in the patient and encourage him to make a

full disclosure to his physician of his symptoms and condition. Consequently, this prevents the physician from

making public information that will result in humiliation, embarrassment, or disgrace to the patient.

‣ Petitioner's discourse while exhaustive is however misplaced. Lim v. Court of Appeals clearly lays down the

requisites in order that the privilege may be successfully invoked:

1. The privilege is claimed in a civil case;

2. The person against whom the privilege is claimed is one duly authorized to practice medicine, surgery or

obstetrics;

3. Such person acquired the information while he was attending to the patient in his professional capacity;

4. The information was necessary to enable him to act in that capacity; and,

5. The information was confidential and, if disclosed, would blacken the reputation (formerly character) of the

patient.

‣ In the instant case, the person against whom the privilege is claimed is not one duly authorized to practice

medicine, surgery or obstetrics. He is simply the patient's husband who wishes to testify on a document executed

by medical practitioners. Plainly and clearly, this does not fall within the claimed prohibition. Neither can his

testimony be considered a circumvention of the prohibition because his testimony cannot have the force and

effect of the testimony of the physician who examined the patient and executed the report.

‣ Counsel for petitioner indulged heavily in objecting to the testimony of private respondent on the ground that it

was privileged. In his Manifestation before the trial court, he invoked the rule on privileged communications but

never questioned the testimony as hearsay. It was a fatal mistake. For, in failing to object to the testimony on the

ground that it was hearsay, counsel waived his right to make such objection and, consequently, the evidence

offered may be admitted.

ATENEO LAW 3-B EVIDENCE DIGESTS

BATCH 2017 19 ATTY. EUGENIO VILLAREAL

GONZALES V. CA

G.R. No. 17740, October 30, 1998

Digest Author: Irvin Velasquez

PARTIES

‣ Petitioners: Abad Gonzales, Dolores Abad, and Cesar Tioseco – Siblings of the deceased Ricardo

‣ Private Respondents – Honoria Empaynado (common law wife of deceased Ricardo), Cecilia H. Abad – Child of

Honoria with the deceased Ricardo, Marian H. Abad – Child of Honoria with the deceased Ricardo

‣ Jose Libunao, not a party, deceased legitimate husband of Honoria, claimed to be the father of Cecilia and Marian,

by the petitioners

‣ Dolores Saracho, not a party, mother of Rosemarie Abad

‣ Rosemarie S. Abad – Another child of the deceased from another woman

FACTS

‣ Petitioner Abad Gonzales, Dolores Abad, and Cesar Tioseco sought the settlement of the intestate estate of their

brother (Ricardo Abad), before the CFI Manila

‣ They claim that they were the only heirs of Ricardo Abad as he allegedly died a bachelor, leaving no descendants or

ascendants

‣ The petitioners executed an extra-judicial settlement of the estate of their late mother (Lucila de Mesa). They

managed to cancel TCT’s and caused them to be transferred to their names. They also executed Real Estate

Mortgages on these properties.

‣ The private respondents (Honororia Empaynado, Cecilia, Marian, Rosemarie Abad) charge the petitioners for

deliberately concealing the existence of three children fathered by the deceased

‣ They filed a motion to set aside proceedings and for leave to file opposition in the petition for settlement of the

intestate estate of Ricardo Abad (the deceased brother of the petitioners) where they allege that Honoria

Empaynado had been the common-law wife of Ricardo for 20 years before his death and that they had two

children (Cecilia and Marian). They also disclosed the existence of Rosemarie Abad, a child allegedly

fathered by Ricardo with another woman (Dolores Saracho).

‣ The respondents later on discovered that petitioners had managed to cancel TCT’s by extra-judicially partitioning

their mother’s estate. Thus, they also filed a motion to annul the said extra-judicial partition, the TCT’s that they

caused to be transferred in their names, and the real estate mortgages that they caused to be annotated therein.

‣ The CFI ruled that Cecilia, Marian and Rosemarie to be acknowledged natural children of the deceased, and named

them as the only surviving legal heirs. The court also annulled the TCT’s the petitioners obtained after extra-

judicial settlement of their mother’s estate.

‣ The petitioners filed for an MR, which was denied, as well as two notices of appeal both denied for being filed out

of time. They filed for a petition for certiorari before the CA but was denied lack of merit.

‣ Arguments of Petitioners:

‣ They submit that Cecilia and Marian are not the illegitimate children of Ricardo, the decased, and Honoria, but

the legitimate children of the spouses Jose Libunao (now deceased) and Honoria Empaynado

‣ Petitioners in contesting Cecila, Marian and Rosemarie Abad’s filiation, submit that the husband of Honoria

(Jose Libunao) was still alive when Cecilia and Marian were born (Cecila born 148, Marian born 1954). They

claim that Jose died sometime in 1971

‣ THEIR EVIDENCE:

1. Applications for enrolment at Maputa Institute of Technology of children of Honoria Empaynado with her

late husband Jose which were accomplished in 1956 and 1958.

2. They claim that had Jose been dead during the time when said applications were accomplished, the

enrolment forms would have stated so. Thus they conclude that Jose must have still been alive in 1956 and

1958

3. They also presented joint affidavit of two persons who stated their knowledge of Jose’s death in 1971

ATENEO LAW 3-B EVIDENCE DIGESTS

BATCH 2017 20 ATTY. EUGENIO VILLAREAL

4. They also presented an affidavit of a doctor declaring that in 1935, he had examined the deceased (Ricardo)

and found him to be infected with gonorrhea and that he had become sterile because of the disease (thus he

could not have fathered the alleged natural children)

‣ Arguments of Respondents:

‣ They claim that Jose died sometime in 1943 (before the alleged natural children were born)

‣ They claim that Ricardo acknowledged the children as his natural children

‣ THEIR EVIDENCE:

1. Individual income statements and assets of Ricardo and

2. Individual tax returns where he declared his legitimate wife (Honoria) and his legitimate dependent

children (Cecila and Marian, and Rosemarie Abad)

3. Insurance for Cecilia, Marian

4. Trust fund payable to Marian and Cecilia

5. Bank deposits for Cecilia and Marian

‣ As to the Doctor’s affidavit (about the gonorrhea), the same was objected to by private respondents as being

privileged communication under Section 24 (c), Rule 130 of the Rules of Court.

ISSUES/HELD

‣ Whether or not the pieces of evidence as presented by petitioners are conclusive evidence to establish a

presumption that the children are the legitimate children of Honoria and Jose? NO. The evidence presented by

petitioners to prove that Jose died in 1971 are far from conclusive.

RATIO

‣ Failure to indicate on an enrolment form that one’s parent is “deceased” is not necessarily proof that said parent

was still living during the time said form was being accomplished.

‣ The the joint affidavits presented by petitioners as to the supposed death of Jose Libunao in 1971 is not competent

evidence to prove the latter’s death at that time, being merely secondary evidence. Jose Libunao’s death certificate

would have been the best evidence but they failed to present the same, although there is no showing that said

death certificate has been lost or destroyed as to be unavailable as proof of Jose Libunao’s death. More telling, while

the records of Loyola Memorial Park show that a certain Jose Bautista Libunao was indeed buried there in 1971,

this person appears to be different from Honoria Empaynado’s first husband, the latter’s name being Jose Santos

Libunao. Even the name of the wife is different. Jose Bautista Libunao’s wife is listed as Josefa Reyes while the wife

of Jose Santos Libunao was Honoria Empaynado.

‣ As to the Doctor’s affidavit, the same is inadmissible in evidence. (Rule 130 Sec 24 (c)) The rule on confidential

communications between physician and patient requires that:

1. The action in which the advice or treatment given or any information is to be used is a civil case;