Professional Documents

Culture Documents

This Content Downloaded From 132.174.250.76 On Wed, 20 Apr 2022 06:27:33 UTC

Uploaded by

SERGIO HOFMANN CARTESOriginal Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

This Content Downloaded From 132.174.250.76 On Wed, 20 Apr 2022 06:27:33 UTC

Uploaded by

SERGIO HOFMANN CARTESCopyright:

Available Formats

Who Detects Ecological Change After Catastrophic Events?

Indigenous Knowledge, Social

Networks, and Situated Practices

Author(s): Matthew Lauer and Jaime Matera

Source: Human Ecology , FEBRUARY 2016, Vol. 44, No. 1 (FEBRUARY 2016), pp. 33-46

Published by: Springer

Stable URL: https://www.jstor.org/stable/24762721

JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide

range of content in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and

facilitate new forms of scholarship. For more information about JSTOR, please contact support@jstor.org.

Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of the Terms & Conditions of Use, available at

https://about.jstor.org/terms

Springer is collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve and extend access to Human Ecology

This content downloaded from

132.174.250.76 on Wed, 20 Apr 2022 06:27:33 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

Hum Ecol (2016)44:33-46

DOI 10.1007/s 10745-016-9811 -3

Who Detects Ecological Change After Catastrophic Events?

Indigenous Knowledge, Social Networks, and Situated Practices

Matthew Lauer1 • Jaime Matera2

Published online: 2 February 2016

£> Springer Science+Business Media New York 2016

Abstract Detecting ecological change is a critical first stepIntroduction

in

the process of local-level adaptation, yet few studies have ex

Over the last several decades, indigenous ecological knowl

plored the factors that predict knowledge acquisition following

catastrophic events. This article empirically assesses individual

edge (IEK) has become a burgeoning field of study in a wide

range of academic disciplines and applied pursuits. Disaster

variation in the ability of Solomon Islanders to detect ecological

change following the alteration of local, shallow-water, marine

experts, for example, have begun to appreciate the importance

environments by a major tsunami. We compare the results

ofof

indigenous knowledge for understanding environmental

marine science surveys with local ecological knowledge of the

hazards, reducing disaster risk, and minimizing vulnerability

benthos. We also examine multiple socioeconomic variables,

(Ellen 2007; Mercer et al. 2007). In sustainable development

and employ social network analysis to measure the influence

and natural resource management, it is argued that when local

of social and expert networks. Results show that villagers with

peoples' perceptions, judgments, and rationales about ecolog

salaried work who are at the intersection of local and global

ical processes are integrated into the development of pro

knowledge were the most adept at detecting tsunami-induced

grams, they tend to be more effective ecologically and socially

(Berkes et al. 2000; Brokensha et al. 1980). This is found

changes to benthic surfaces. Social networks had no statistically

significant influence on villagers' abilities to detect change. particularly

We to be the case in most regions of the world now

argue that these results counter common conceptualizationsexperiencing

of rapid social and ecological change.

indigenous knowledge that emphasize its normative, shared,Advocates of IEK emphasize its richness and site specific

inter-generationally transmitted characteristics rather thanity

its as characteristics that enable local resource users to alter

heterogeneity, emergence, and practical application. Our find

their management strategies as ecological conditions change

ings have implications for theory about the foundations of(Berkes

in et al. 2000; Drew 2005). The interplay between local

knowledge, environmental conditions, and management deci

digenous knowledge research and the design of disaster mitiga

sions plays a fundamental role in long-standing, traditional

tion efforts or resource management programs that incorporate

indigenous ecological knowledge. resource management. IEK-informed practices, in some cases,

support the resilience of socio-ecological systems because

they manage for change rather than specific conservation or

Keywords Tsunami • Disaster mitigation - Ecological

societal outcomes by continually adapting management poli

change Indigenous ecological knowledge Solomon Islands ■

cies (Berkes et al. 2000).

Benthos

A fundamental capacity that enables indigenous people to

adapt is ecological change detection, a form of IEK that has

ISI Matthew Lauer been empirically documented in a variety of contexts

mlauer@mail.sdsu.edu (Alexander et al. 2011; Aswani et al. 2014; Lauer and

Aswani 2010). Until the 1990s, IEK studies rarely evaluated

who detects changing ecosystems. Moreover, the variation,

1 San Diego State University, San Diego, CA, USA distribution and evolution of knowledge within traditional

2 California State University Channel Islands, Camarillo, CA, USA communities as well as the pathways by which knowledge

£) Springer

This content downloaded from

132.174.250.76 on Wed, 20 Apr 2022 06:27:33 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

34 Hum Ecol (2016) 44:33-46

flows tended toknowledge

be(Vandebroek and Balick 2012). Knowledge

secondary ero

rath

(for some exceptions see

sion, in particular, is an important Boster

area of research. A signifi

ethnobiological research,

cant body for

of research suggests that as communities are drawnexa

with identifying cross-cultural

into market economies, IEK is displaced by new knowledge r

classification rather

associated with livelihood than the

changes (Reyes-Garcia etal. 2005; dy

tion (e.g., Berlin

Ross 2002;1992). This

Schultes 1994; Zent 2009). gene

For example, Spoon

to the way in which

(2011) showed classic

how the ecological knowledge of the Khumbu IE

knowledge. Typically, knowledg

Sherpa, agro-pastoralists from Nepal, has shifted away from

tive, socially agro-pastoralism towards information and

transmitted values associated sh

trait

or societies, a perspective that

with a growing tourism industry. These changes, however, ha

in the social sciences

were highly variable across (Ellen

the Sherpa population et

and a

More

recently, epistemological

across domains of knowledge. Knowledge erosion appears

aboutapproaches

to vary both to indigenous

at the individual level and across biocultural

mogeneity over

settings. hybridity

Zarger and Stepp (2004) documented that and

even in a c

experiential, and other

highly acculturated setting Tzeltalmodalities

Maya children retain a rich

ing (Ellen et al.

understanding 2000;

of botanical knowledge,Escobar

suggesting that IEK

1993; Ingold 2000; Zent 2009).

may persist among some individuals or segments of a society K

proaches or processural

despite significant cultural and economic perspec

change. Educational

knowledge as settings appear to play an important

dynamic and role in knowledge

situate

emergent, experiential,

transformation. Ohmagari and Berkesand hete

(1997) research among

a result, the Cree women of subarctic

focus of Canada research

revealed how the use of s

shared values, beliefs,

non-local patterns,

language in schools heavily impacted knowledge

of of the to

communities local environment.

understanding

tribution, change, flow,

Very little research, and

however, has empirically em

assessed the

other knowledge.

capacity of local or indigenous people to detect changes after

Our previous large-scale, ecological disruptions.

work in These events may

the Solomperma

practice-based nently

approach to know

alter local ecological conditions, yet little is known

a more comprehensive theoretic

about the extent, accuracy, and rapidity of detection by tradi

ing IEK of thetional local marine

people, and how the related eco

new knowledge propagates.

2009) as well as disaster

Clearly, respons

the type and extent of disturbance will influence

document how knowledge

IEK acquisition:

is slow ecological

not change, such as

only

generationally'shifting

through oral

baselines,' will be detected differently hist

than abrupt,

vised, bodily, non-cognitive

intense ecological disturbances caused by a tsunami. way

cases are overlooked

To explore pathways of by cogniti

knowledge acquisition and its

knowledge. A transmission

situated practice

through communities, researchers in many fields

conceptual space for

have employed these

social network more

analysis, although to date only

ing, it also provides

a handful of studies have a

appliedtheoretica

these techniques to IEK

lematic distinction

(Bodin and Prell 2011; Reyes-Garcia et al. 2013). This is quiteloc

between

knowledge (Agrawal 1995)

surprising considering the explosion of interest in by

network c

practices (Pickering 1995). Tum

studies across the social and natural sciences (Borgatti et al.

"situated messiness" or the "motley" nature of 2009; Wasserman and Faust 1994). One of the most widely

techcnoscientific practice is often overlooked because ofresearched

a concepts in social network studies is centrality,

bias in western thinking towards theory at the expense of the

which refers to the structural prominence or importance of a

actual practice of science. node (e.g., individual, household, organization) in a network.

Propelled by this alternative, practice/processural viewTypically,

of individuals with many non-negative social ties in

knowledge, a raft of recent research has focused on the quan

volving friendship or trust tend to be more effective dissemi

titative measurement of individual variation in knowledge

nators of information (Katona etal. 2011), which is important

(Atran and Medin 2008; Reyes-Garcia et al. 2007). Ethnobi

since studies suggest that occupying central positions within

ological studies in particular have developed increasingly networks

so may result in a higher level of ecological knowledge

phisticated methods and analyses exploring knowledge het (Reyes-Garcia etal. 2013). Many questions remain, however,

erogeneity. Factors such as age, gender, livelihood, residence,

about the extent to which these principles apply to ecological

education, household income, and integration into the market

knowledge in small-scale, traditional communities facing the

economy have been shown to correlate with variation incombined forces of globalization and climate change, or

Springer

This content downloaded from

132.174.250.76 on Wed, 20 Apr 2022 06:27:33 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

Hum Ecol (2016) 44:33^6 35

which have hamlets (Solomon Islands Government

been subjected 2011). Its inhabitants t

bances such are culturally

as indistinguishable from, and genealogically

earthquakes, t

Here we enmeshed with, people

argue that who reside in adjacent Roviana La

concept

dynamic, goon. In both lagoons, Roviana,

active, and an Austronesian language

heterog

and processes

unique toprovides a

the region, is the local vernacular. Solomon Islands mor

theoretical foundation from

Pijin, the lingua franca of the Solomon Islands, is also widely

Islanders spoken. As in most of the Solomonthe

perceived Islands, Vonavona com

ecolo

We examine the

munities rely onfactors

subsistence fishing and horticulture forthat

their i

knowledge, main livelihoods even though extensive social and

including thecultural eff

2007, an 8.1 change has occurred over the past several centuries. Subsis

magnitude earth

30 km off the coast of the western Solomon Islands. Thetence fishing continues to dominate village life, and marine

quake generated a large tsunami that decimated seaside vil

resources provide most of the protein in the local diet. Many

lages and changed marine ecological conditions. In 2006, our

households also engage intermittently with the cash economy,

research team conducted marine science (MS) surveys

undertaking small-scale commercial activities such as

documenting different habitat types and benthic surfaces shell-diving,

in copra-production or the marketing of fish, shell

Vonavona Lagoon, a large lagoon on the western coast offish, fruits or root crops. Logging operations have also prolif

New Georgia Island. After the tsunami we replicated theerated, and provide employment for many islanders.

2006 survey at two equally spaced time intervals (2008 and For this research, social science fieldwork was conducted

2010) to document any changes to the benthos. in 2010 among villagers in three communities located in

southern Vonavona: Kinda, Saika, and Kinamara. The three

Previous analyses comparing IEK and the marine surveys

villages have approximately 110 households with a total pop

indicate that the tsunami changed benthic habitats and that

local Solomon Islanders detected the changes to their seaulation of 500 individuals. Several decades ago these commu

scape. (Aswani and Lauer 2014). This previous research, nities lived together on a small island in the center of the

Lagoon called Repi. In the mid-1990s, however, the site was

however, assessed the abilities of villagers in focus groups.

Below, we explore in more detail the capacity of individualabandoned because it lacked a reliable source of fresh water,

and the population was growing rapidly, causing overcrowd

villagers, rather than focus groups, to detect environmental

changes by considering how specific variables identified in ing and other issues.

the IEK literature (e.g., age, gender, occupation, education, Prior to the 2007 tsunami, our study team conducted MS

etc.) may influence the ability to monitor local ecologies. surveys

In of an inner lagoon reef system that extends off the

addition, we employ social network analysis to ascertainsoutheastern edge of Repi Island. We were studying the region

whether the perpetuation and transmission of knowledgeasispart of a marine resource management initiative that began

shaped by positions within social and expert networks. in 2000 (Aswani et al. 2004). The 10-year initiative culminat

ed in the creation of a network of marine protected areas

(MPAs), including eight MPAs in Vonavona Lagoon. To

Methods achieve this we (and others from the research team including

local counterparts) conducted numerous participatory work

Study Site shops in Vonavona Lagoon to assist local communities in the

establishment and maintenance of their management program.

The Solomon Islands make up the third largest archipelago in The process also involved: a) the development of a local

the Pacific, with six main islands and nearly 1000 smaller non-governmental organization called Tiola Conservation

islets. Vonavona Lagoon lies off the western coast of New Foundation, b) the integration of the management initiatives

Georgia, and is bounded by two smaller islands, Parara to into the regional and national governments' costal manage

the west and Kohinggo to the east (Fig. 1). The 30 km-long ment plans, c) legally codifying the management initiatives in

lagoon contains numerous protected bays, barrier islands, government statutes and legislation, and d) training local

pools, coral reefs, intertidal flats, and passages, and is world counterparts in marine science, anthropology, and the use of

renowned for its marine biodiversity and striking natural beau Geographic Information Systems (GIS). This long-term col

ty (Green et al. 2006). Large portions of the lagoon are shal laboration with local villagers, governmental officials, and

low, (<20 m) and contain a multitude of marine habitats, in Solomon Islander counterparts helped ensure that Vonavona

cluding seagrass meadows, mangroves, freshwater swamps, villagers involved in our study were confident that it would

river estuaries, sand channels, shallow coral reefs, silt-laden benefit their community and region.

embayments, and reef drops. The Repi reefs were initially selected for the benthic sur

Vonavona Lagoon is home to approximately 5,500 people veys because of the diversity of its inner lagoon habitats in

who reside in several main villages and a half-dozen smaller cluding seagrass, coral reefs, sand flats, pools, and silt.

<?} Springer

This content downloaded from

132.174.250.76 on Wed, 20 Apr 2022 06:27:33 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

36 Hum Ecol (2016) 44:33-46

Fig. 1 Solomons Islands with inset o

Moreover, only

Vonavona a biophysic

villagers re

for the bulk of and people's

their protein,ide

and

(Aswani 1998). of

The a named

reefs are land

abo

are easily butubutu

reached by (kint

paddling

common (boundaries).

fishing methods curre

goon Most

include

angling Vonavona

with hook

(vaqara), divingmains within

(suvu), t

spearing

shells (hata). lamana

On average(open

most se

a

marine resourceopen-sea-facing

and consume fres

i

three times per week.

(mainland). With

Our long-term ethnographi

logical categories

15 years) describes

holapana howorVon

san

tualize their grass),

environmentkopi (lag

th

(Fig. 2). Pepeso translates

ovuku (river lite

mou

but is typically employed

(reef drop). as

Thes

that demarcates land-sea

morphology, terr

abi

interior mountain-ridge-tops

plant and o

animal

As is commonly found

different elsewhe

substra

land and sea ecological

ime (algaezones

spec

ceptualized as ngongoto (prim

ontologically dis

as aspects of ovalis),

an integrated

nelaka (w

Springer

This content downloaded from

132.174.250.76 on Wed, 20 Apr 2022 06:27:33 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

Hum Ecol (2016) 44:33-46 37

Pepeso

l 1

Tutupeka Poana Toba Vuragarena

nainland) (lagoon) (barrier (outer barrier/

island) open sea

Sagauru

(reef)

Kulikuliana

(seagrass meadow)

Fig. 2 Cross-section schematic of a generalized pepeso in Vonavona, showing local environmental classifications and their approximate English

equivalents

patu pede (generic term for Turbinaria, Pavona, and of the tsunami described how the lagoon water first reced

Acropora corals), patu vinu (.Acropora corals), patu voa ed from the shoreline then returned as several one-meter

(.Pontes coral formations), tatalo (algae) and zalekoro (grav high pulses or waves. The waves swept into the lagoon,

el). Usually the dominant benthic types identified by local flooding many areas and causing violent currents and ma

people include onone, nelaka, kulikuliana, and patu. Impor jor movements of rubbish- and silt-laden water. A long,

tantly, these dominant benthic types correspond very closely narrow island called Rokama, near the entrance of the

to common marine science benthic categories of sand (onone), lagoon, was permanently cut in half by the tsunami.

silt (nelaka), coral (patu), and seagrass (kulikuliana).

The impact of the earthquake and tsunami on Vonavona Data Collection

Lagoon was significant. Although no villagers died in

Vonavona (nearly 60 lives were taken in other regions) it In 2010 we conducted 58 surveys in Kinamara (w = 28),

was a life-changing event that has had lasting impact includ Kinda (n = 6), and Saika (n = 24) where information was

ing extensive coastal flooding, changes to the local ecology, elicited to show the extent of villagers' IEK and nine

and major property damage, not to mention much human suf socioeconomic variables that, according to previous re

fering and psychological distress. Luckily, the villagers' first search, may influence levels of knowledge: age, gender,

reaction to the earthquake was to flee the coast and seek high number of years of local residence, level of education,

ground, a response that was common across the Western Prov type of occupation, days per week marine food is con

ince and saved many lives (Lauer 2012). Fearing another tsu sumed, days per week spent fishing, monthly income,

nami, Vonavona villagers spent 2 to 3 months living in tem and average weekly expenditure on processed food

porary shelters on high ground near the center of Parara Island (Table 1) (Zent 2013). The number of surveys conducted

and very few people ventured into the lagoon to fish or collect in each community was based on population size and the

marine resources. total sample size represents approximately 50 % of house

Lagoon and coastal areas were heavily impacted. Be holds in the three villages. A relatively even number of

cause of its position relative to the fault, the lagoon sank men and women from different age groups was chosen to

0.51 m (Taylor et al. 2008). This left many low-lying represent all ages over 18 years of age.

areas permanently flooded. The coastal areas of Parara A subsample of these individuals was asked additional

Island suffered much saltwater intrusion killing large questions about their social and expert networks. To generate

swaths of mangrove. Of the three study villages, our subsample for the social network study, we employed a

Kinamara was the most severally impacted with aboutsnowball sampling method where we initially asked 17 re

30 % of the village area permanently flooded, forcingspondents about their social and expert networks. This in

the community to rebuild its dock and relocate a number volved asking informants to name the seven most important

of public buildings such as the community hall and a persons in their lives, starting with the most important, outside

clinic. Fortunately, no houses were destroyed because of their household (for more details about this sampling

they were all located on higher ground. Local descriptions strategy see Atran et al. 2002). We determined this to be their

Springer

This content downloaded from

132.174.250.76 on Wed, 20 Apr 2022 06:27:33 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

38 Hum Ecol (2016) 44:33-46

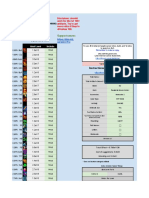

Table 1 Descriptive statistics of all

N= 58 N= 32

Variables Description Min Max Mean Std. Min Max Mean Std.

Dev. Dev.

Dependent

Agreement Agreement between indigenous knowledge 0 5 2.5 1.3 0 5 2.4 1.5

of abiotic and biotic substrates and a 2010

marine science survey.

Explanatory

Age Age of participant in years 24 75 44.7 12.6 31 75 49.7 11.4

Years in village Years the participant has lived in the village 1 75 19.3 18.4 4 75 22.0 20.0

Times per week Fishing Average number of fishing trips per week 0 6 2.4 1.9 0 6 2.5 2.0

Days per Week Fish Consumed Average number days a week a participant 1 7 2.7 1.9 1 7 2.8 2.1

eats fresh fish

Monthly Income (adjusted) Average monthly cash income 0 13000 1106.7 1854.3 0 13000 1275 2375

Money Spent on Processed Food Average amount of money spent on processed15 800 128.8 116.1 20 800 139.0 140.4

food per week

DegreeSN A participant's degree measurement

- - - -

1 11 4.9 2.4

for the social network

BetweennessSN A participant's betweenness measurement

- - - -

0 111.7 27.4 32.7

for their social network

Indegree_EN A participant's degree measurement

- - - -

0 10 1.7 3.0

for the expert network

BetweennessEN A participant's betweenness measurement

- - - -

0 45.7 4.8 11.7

for the expert network

N % of total N % of total

Occupation 1 = Farmer 28 48 % 14 44%

2 = Fisher 6 10 % 3 9 %

3 = Pastor 6 10 % 4 13 %

4 = Housewife 7 12 % 2 6 %

5 = Salaried work 6 10 % 6 19 %

6 = Other 5 9 % 3 9 %

Gender 1 = Male 32 55 % 21 66 %

2 = Female 26 45 % 11 34 %

Education 1 =None 0 0 % 0 0 %

2 = Up to 6th grade 44 76 % 23 72 %

3 = 6th-9th grade 7 12 % 5 16 %

4 = 9th- 11th grade 1 2 % 0 0 %

5 = High school graduate 0 0 % 0 0 %

6 = Trade school 4 7 % 2 6 %

7 = University 2 3 % 2 6 %

social network. We also asked people to indicate whom they To evaluate local knowledge about ecological change as

would turn to find out something they did not understand sociated with the 2007 tsunami, the survey included an elici

about the marine environment. We determined this to be their tation technique where a poster-sized color air photograph of

expert network. Due to time constraints, we were able to find the Repi study area was used as a visual tool to assist all 58

and interview only 15 of these individuals to represent the villagers in identifying benthic substrates. A 61 x 122 cm

total social network sample of 32 individuals. Since half of hard-copy map was created by digitally scanning and rectify

the population in a typical Solomon Islands village is under ing a color aerial photograph (1:25,000) of the southern

the age of 18 (Solomon Islands Government 2011), our social Vonavona lagoon on September 2, 1991. Five polygons were

network sample of 32 individuals was approximately 13 % drawn on the image to demarcate different sites within the

(32 out of 250) of villagers 18 years or older and one-third larger study area (Fig 3). Using the poster-sized map, we

(29 %) of village households (assuming each interviewee rep helped the informants orient themselves to the aerial perspec

resents one household). tive by encouraging them to recognize, identify and name

Springer

This content downloaded from

132.174.250.76 on Wed, 20 Apr 2022 06:27:33 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

Hum Ecol (2016) 44:33-46 39

Fig. 3 Air photograph of r epi reef

Points are the site locations for mar

villages, islands and

documented the entire study site's other

abiotic and biotic substrates phys

map. The informants

before and after the 2007 tsunami. For eachwere

survey, we select the

and name the dominant

ed underwater benth

sample site locations by creating a grid using

language based on

GIS software their

that generated recolle

points every 60 m, for a total of

the benthos. Ideally

982 sampling points across the 253 hawe would

study area. The geo

the lagoon, but because

graphic coordinates high-r

of each sample point location were loaded

able we used into a Trimble Geoexplorer

the 1991 XT GPS receiver.

air Using the GPSphoto

interviews itreceiver,

becamea team consisting of a researcher apparent

and two trained,

mnemonic device or visual aid that enabled the informant to local research divers from nearby Roviana lagoon navigated

orient themselves in the seascape rather than something that by boat to each predetermined field point location and docu

was read or interpreted. In other words, informants did not mented the underwater habitats. At each site al-mxl-m PVC

simply interpret the various shades of color on the image, frame was lowered onto the seabed and the indigenously de

but instead the image served to jog the informants' memory fined substrate and dominant benthic habitat categories (the

about the study reef, an area that they cross frequently (on same categories used in the household survey mapping exer

average once or twice a week) during their fishing trips. cise) were recorded in the local language. If the sampled area

Through this elicitation technique ten dominant substrate had a mix of different habitats, the primary (dominant), sec

types were identified: ime (algae species), kuli gele (Enhalus ondary, and/or tertiary habitats were recorded.

acoroides), kuli ngongoto (primarily Thalassia hemprichii To compare the MS surveys with the responses provided

and Halophila ovalis), nelaka (silt), omomo (algae species), by local informants on the household survey, we used Arc/

onone (sand), patu mateana (dead coral) patu vinu (Acropora GIS 10 to run spatial queries that selected just those points

corals), patu voa (.Pontes coral formations) and tatalo (algae). inside the five study site areas assessed by the informants

For statistical analysis, we reduced these ten categories to four during the household survey. The five study sites contained

useful categories by combining the seagrass and algae species between three and 26 MS survey sample sites for a total of 59

into one category and the coral species into one category, samples (N= 59) each year. Using these data sets we measured

leaving us with the categories: coral, sand, seagrasses and the correspondence between local assessments of benthic

algae, and silt. types elicited through the image interpretation techniques

The three underwater MS surveys conducted by the same and our 2010 MS survey results. We analyzed only the 2010

research team in January 2006, July 2008 and May 2010 MS data set because that was the year in which individual

Springer

This content downloaded from

132.174.250.76 on Wed, 20 Apr 2022 06:27:33 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

40 Hum licol (2016) 44:33—46

Table 2 Dominant abiotic and biotic benthic substrates recorded

villagers were surveyed. Al

during marine science visual surveys (N= 59 for each survey year)

sometimes given in both t

survey indicating

Survey Year a mixture

only the first response, rep

Study site 2006 2008 2010

type. Selecting only the dom

1 sand sand silt

is a common strategy in h

2 sand seagrass/algae sand

2013) because it provides

3 silt silt silt

any changes that occurred to

4 seagrass/algae seagrass/algae seagrass/algae

increasing the complexity o

5 sand sand sand

compared these two data set

if there was agreement betw

and the MS survey, then it

agreement Tukey post-hoc was

it test. All statistical analyses were run in R

coded as 0

five sites version 3.1.1 (2014).

producing our d

which rangedThe subsample

from (N= 32) of interview respondents who were 0 to 5, w

between indigenous

asked to provide information on social and expert networks knowle

allowed us to calculate two degree and two betweenness cen

trality measures using the social network analysis software

Data Analysis

package UCINet 6 (Borgatti et al. 2002). Degree centrality

identifies the direct connection between two individuals and

Three separate analyses

betweenness centrality were

offers a measure of the importance of

collected from household

individuals that lie in the shortest path between two individ su

was performed

uals. Social and expert with the

network information was used to con s

(iV= 58) to determine

struct two binary adjacency matrices (32 x 32) containingthe

only

agreement the names of those who were both interviewed

between IEKand named as and

point contacts. Those individuals who

agreement scorewere named but not as a

variable and nine socioeconomic variables were selected as interviewed were not included in this analysis. Data from the

independent variables.1 An ordinal logistic regression modelsocial network were treated symmetrically while the expert

was chosen to analyze the effects of the independent variables

network data were treated asymmetrically. The resulting mea

on a respondent's agreement score as this models the proba

sures served as four additional independent variables and were

bility that agreement is less than or equal to a given score, and

added to the variables used in the analysis of the larger sub

hence can be manipulated to provide the odds of a higher

sample and evaluated employing a method similar to that not

score. The equation for such a model is of the form ed above.

P(agree<j)

Iogit[P(agree<j)] = log

1 -P(agree<j)

Results

— Po + P\x\ + ••• + PfXt

The MS surveys showed that benthic substrates in two of the

where j-0, 1, 2, 3, 4 (the probability that agreement is<5 is

five surveys sites changed after the tsunami (Table 2). Site one

equal to one), and x represents an independent variable.

For the first step of the analysis, we conducted bivariate remained unchanged between years 2006 and 2008, but then

shifted from sand to silt in 2010. Site two changed from sand

screenings to consider each potential variable as the sole var

in 2006 to seagrass in 2008 and back to sand in 2010. Sites 3

iable in the model and a likelihood ratio test was run compar

ing each model to a null (intercept only) model. All indepen

5 showed no change over the study period. The agreement

between IEK assessments of substrate surfaces and the MS

dent variables found to be significant at the p< 0.1 level were

then placed in a multi-variable model to examine their signif surveys ranged between 0 (no agreement) to 5 (complete

icance when controlling for the other variables. These models

agreement) with a mean agreement of 2.5.

were optimized so that in order for a variable to remain in the Using a predetermined cutoff point of 90 % confidence

final model it had to be significant at a<0.05. As a final step,

level, a <0.1, for inclusion in a multi-variable analysis, the

a one-way analysis of variance test was run for which the bivariate screening for the full sample (jV=58) revealed that

independent variable occupation was the only significant var

' We considered using data transformation techniques on several vari

iable emerging from the screening analyses. This allowed for ables to provide more normal distributions, but the transformed data did

group-wise comparison of mean agreement scores using a not affect the outcome of our statistical analysis.

Springer

This content downloaded from

132.174.250.76 on Wed, 20 Apr 2022 06:27:33 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

Hum Ecot (2016) 44:33-46 41

Table 3 Results of Bivariate

Screening of Independent 2010 (Af=58) 2010 (Af=32)

Variables tested for significance

Variable Name LR chi-square p-value LR chi-square p-value

in an ordinal logistic regression

model Age 2.052 0.152 1.031 0.310

Gender 0.189 0.664 0.83 0.362

Years in Village 1.829 0.176 2.36 0.124

Education 2.223 0.695 7.213 0.065"

Occupation 19.495 0.002* 20.593 0.001**

Times per week Fishing 0.588 0.443 0.573 0.449

Days per Week Fish Consumed 0.039 0.843 0.059 0.808

Monthly Income 0.015 0.902 0.052 0.819

Money Spent on Processed Food 1.531 0.216 3.547 0.060**

Degree (Social Network)

- -

0.624 0.430

Betweenness (Social Network) - -

0.634 0.426

Indegree (Expert Network)

- -

0.056 0.813

Betweenness (Expert Network)

- -

0.037 0.847

* For the 58 sample screening runs only Occupation proved to be significant

**For the 32 sample screening runs, education, occupation, and money spent on processed food were all found to

be significant at 90 % significance and so were included in a multi-variable model

only the variable occupation had a statistically significantused

re the occupational group 'fisher' as the reference

group to test if fishers had the highest IEK-MS agreement

lationship to the dependent variable IEK-MS agreement score.

score due to the large amount of time they spend

This relationship was found to be a strong one, \2 (5)= 19.49,

p- 0.002. Because only that independent variable showedinteracting

a with the marine environment. Our results,

however, indicated that the odds of salaried workers hav

significant relationship to the dependent variable, no multi

variable work was done with the larger sample. ing a higher IEK-MS score were more than 28 times those

of individuals who fish for a living (Table 5). Importantly,

The bivariate screening for the reduced sample (N- 32)

found that three socioeconomic variables, 'education,'salaried workers also fished quite regularly even though

'occupation,' and 'money spent on processed food' show

they had salaried employment. On average they fished of

2.5 times per week (N= 58), which was just below the

a significant relationship to IEK-MS agreement at the

90 % confidence level (Table 3). These variables were

mean (2.6 times per week) of all respondents (Table 6).

placed in a multi-variable model for which a backward We further analyzed the differences in mean scores for

step-wise reduction was performed. As with the larger

the occupation groups in the larger sample (N= 58) using

sample, a final model showed 'occupation' to be highly

a one-way ANOVA test (Table 5). Mean agreement scores

significantly related to IEK-MS agreement, were

\2 found to be significantly related to occupation, F (5,

(5) = 20.593,/? = 0.001 (Table 4). 52) = 3.95, p = 0.004. A post-hoc Tukey examination of

pair-wise differences found that the groups for which the

Further examination of the occupation variable indicat

mean differed significantly at p< 0.5 were Salaried/Other,

ed that of the six different self-reported occupations un

Salaried/Farmer, and Salaried/Pastor, and Salaried/

dertaken by informants (fisher, farmer, pastor, housewife,

Housewife at/? <0.1. There was no statistically significant

salaried worker, and/or other), in individual comparisons,

difference in means between salaried workers and fisher

only villagers with salaried employment had significantly

men, which was likely due to an outlier (see Fig. 4 and

higher odds of selecting benthic habitats that agreed with

the MS survey than the reference group of fisherman. Wethe Discussion section). Moreover, the higher p-value may

Table 4 Reduction of multi

variable model with three Run 1: Run 2: Run 3:

variables (N= 32)

Variable Chi-Square Pr>ChiSq Chi-Square Pr>ChiSq Chi-Square Pr>ChiSq

Education 5.44 0.1421 5.61 0.132 20.59 0.001

Occupation 16.05 0.0067 18.99 0.0019

SpendProcessed 0.28 0.5946

Food

Springer

This content downloaded from

132.174.250.76 on Wed, 20 Apr 2022 06:27:33 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

42 Hum Ecol (2016) 44:33^16

Table 5 Odds ratios of obtaining

Occupation Odds ratio p-val Adj. p-val Mean Agreement Std Dev

a higher agreement score when

compared to the reference group,

Farmer (n = 28) and0.786 0.77 0.98 2.36 1.19

fishermen, mean agreement

scores for

Fisherman («each

= 6) occupation

reference group

2.67 1.37 - -

(JV=58) 0.318 0.29 0.98 1.83 1.47

Pastor (n = 6)

Housewife (n = 5) 1.023 0.98 0.98 2.57 0.98

Salaried worker (n = 6) 28.526 0.01 0.05 4.33 0.82

Other (n = 5) 0.258 0.21 0.98 1.60 1.14

* Hochberg adjustment is made to the p-values to account for multiple comparisons

be a function of the small sample size and in such cases it (Bicker etal. 2004; Reyes-Garcia etal. 2005). Factors associ

is often better to look at the various means and standard ated with modernity such as years of school, academic skills,

deviations (Table 7). fluency in a non-local language, household income, and dis

It is important to note that the bivariate screening tance

for to markets or towns, have all been shown to be nega

the reduced sample (N= 32) found that none of the social

tively associated with local ecological knowledge (Reyes

network variables had a statistically significant relation

Garcia et al. 2005). The erosion of knowledge has been ex

ship with the dependent variable. We acknowledge, plained

how based on the idea that acculturation and modernization

ever, that time constraints prevented the collection ofdisplace

so ecological knowledge as people acquire the skills

cial network data from every individual and, therefore, a

needed to live in a more market-centered economy.

more thorough analysis of the global pattern of connec However, recent analyses suggest that the relationship is

tions between nodes. Of the two measures of centrality

more complex, and that IEK responds in different ways to

that were calculated, we have much more confidence inthe forces of globalization (Gomez-Baggethun and Reyes

the degree measurement than the betweenness measure Garcia 2013). In some contexts, wage labor may not displace

ment because degree is not affected by an incomplete local ecological knowledge. Such a finding was reported in a

network sample as it measures direct interaction between study among the Tsimane' of the Bolivian Amazon who were

two individuals. Our betweeness measurement, on the employed in wage labor involving the harvest and sale of

other hand, has limited explanatory power when calculat forest products but retained their ethnobotanical knowledge

ed for an incomplete network and should be viewed as (Reyes-Garcia et al. 2007). Likewise, in Roviana Lagoon,

only a rough guideline. modern knowledge about non-subsistence cash crops was in

tegrated into communities without eroding traditional

Discussion

Two particular findings from this research prompt discussion.

First, our results suggest that Solomon Islanders who earn

salaries tend to be the most adept at detecting ecological

changes associated with infrequent, large-scale disturbances

like tsunamis. This is contrary to research linking market in

tegration and increased levels of modernity to the loss of IEK

Table 6 Days per week

fishing by occupation Occupation Mean days per

(N= 58) week fishing

Farmer 2.1 (m = 28)

Fisherman 4.2 (n = 6)

Pastor 1.7 (n = 6)

T I | | | p

Housewife 1.9 (n = 7) 1 2 3 4 5 6

Salaried worker 2.5 (« = 6) Occupation

Other 3.1 (n = 5) Fig. 4 Boxplot s

Average days fishing 2.6 (N= = 58) different occu

for all participants Pastor; 4 - Hou

outlier in Occup

Springer

This content downloaded from

132.174.250.76 on Wed, 20 Apr 2022 06:27:33 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

Hum Ecol (2016) 44:33^6 43

Table 7 Tukey post-hoc

salaried workers, much more compariso

than most villagers, to glob

scores between Occupation groups

al knowledge about current affairs and government poli

Occupation Difference lower CL Upper CL p adj cies and initiatives.

Comparison Interestingly, results of the statistical analysis revealed an

outlier with a considerably higher IEK-MS agreement score

6-5 -2.733 -4.854 -0.613 0.005'

than others in her occupation group. While it is not unusual to

5-1 1.976 0.401 3.551 0.006'

remove or manipulate outliers for statistical analysis, one of

5-3 2.500 0.478 4.522 0.007'

the main points of this study was to understand variability in

5-4 1.762 -0.186 3.710 0.098'

knowledge, thus we believe that removal of data points simply

5-2 1.667 -0.355 3.688 0.162

because they are extreme in comparison to others does not

6-2 -1.067 -3.187 1.054 0.673

necessarily mean that the value is invalid or erroneous. While

6-4 -0.971 -3.022 1.079 0.726

outliers may change the nature of the statistical relationship

6-1 -0.757 -2.457 0.943 0.774

between two variables, particularly in a small sample size or if

3-2 -0.833 -2.855 1.188 0.825

they are illegitimate (i.e., due to sampling error), we decided to

4-3 0.738 -1.210 2.686 0.870

retain it to demonstrate the importance of understanding the

3-1 -0.524 -2.099 1.051 0.921

social context of each of these data points. In this particular

1-2 -0.310 -1.885 1.266 0.992

case, the outlier is a middle-aged woman who self-reported

4-1 0.214 -1.265 1.694 0.998

that fishing is her primary occupation. Importantly, she was

6-3 -0.233 -2.354 1.887 0.999

the only respondent in this occupational category born in

4-2 -0.095 -2.043 1.853 1.000

Munda, one of the largest towns in the region, and, as

discussed above, a source of other "types" of knowledge.

1 - Farmer; 2 - Fisherman; 3 - Pastor; 4 - Housewife; 5 - Salaried

worker; 6 - Other Her link to a more urbanized center may have exposed her

*p<0.1 to global knowledge about the effects of the tsunami, suggest

**p< 0.05 ing that she may not be a statistical anomaly, but rather an

***/><0.01 important case for understanding IEK in the region.

One kind of global knowledge that salaried workers (and

possibly the woman mentioned above who was bom in Mun

ethnobotanical knowledge (Furusawa 2009). In these cases, da) would have been exposed to after the 2007 tsunami was

the introduction of new knowledge did not necessarily dis the national news media. Numerous radio and newspaper re

place local ecological knowledge; rather, if people had ports emphasized that the tsunami had a significant impact on

sustained contact with the natural environment, they main the reefs and marine habitats of the western Solomon Islands.

tained their IEK. Importantly, Vonavona villagers who earn These reports generally did not give details about changes in

salaries maintain a regular relationship with the marine envi specific areas, but they could have made salaried individuals,

ronment. On average individuals earning salaries fished who would more frequently be exposed to these news reports,

2.5 days per week, which is near the mean for the entire sam more aware that tsunamis cause ecological change. We should

ple (2.6). point out that, in the western Solomons, IEK about tsunamis is

Although individuals who earn salaries fish frequently, minimal. Tsunami-related knowledge is not encoded in the

this does not explain why they would be more adept at language (i.e., the Roviana language does not have a word

detecting change than other villagers who also fish regu for 'tsunami') and there is no known oral history or myths

larly. This may be due to the unique position salaried recounting large destructive waves occurring after earth

workers play in Solomon Island communities. Most sala quakes (Lauer 2012). The lack of local knowledge is attribut

ried work requires that people leave their home villages able to the rarity of tsunamis in this region. Although earth

and live in urban areas like Gizo and Honiara. In our quakes are frequent in the western Pacific, there has not been a

sample, however, individuals earning salaries largelived inor greater magnitude) earthquake, capable of gener

(7.0

their villages. They included two schoolteachers, ating

two gova tsunami, in over 100 years (Taylor et al. 2008). It

ernment workers, one mechanic, and one person standswho

to reason, then, that exposure to global knowledge

worked at a small, nearby eco-resort. Even though about the tsunami (especially through print and television

these

people permanently resided in the villages, their news) and its effects could have sensitized salaried workers

jobs re

quired them to take frequent trips to town centersto ecological

like changes associated with the tsunami more than

Munda or Gizo to collect pay checks. In addition, other

teachers

villagers who rely solely on IEK.

The second

and government employees occasionally travel to town to important finding is that measures of net

work centrality

receive training, and mechanics need access to markets to were not positively associated with eco

logical

buy spare parts. These visits to urban centers exposechange detection abilities. This result contrasts

Springer

This content downloaded from

132.174.250.76 on Wed, 20 Apr 2022 06:27:33 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

44 Hum Ecol (2016) 44:33 46

with a large the village to contacts in of

body town. But salaried

socialworkers did not ne

structural mention anyone outside of theinfluences

position three villages during the net

edge disperses through

work survey interviews. a com

Reyes-GarciaIf weet conceptualizeal. 2013).

habitat change detection as a situated Im

studies conceive of

practice, it is reasonable to suggestknowled

that a person's aptitude

information that flow

might not be influenced by their position in a throug

social or expert

et al. 2009), anetwork (see Boster 1986:434). Changes in benthic habitats

conceptualizatio

mise that would unlikely be a broad topic of conversation

knowledge is because a the

corp

instructionsway inthat

which Vonavona villagersare distin

generate knowledge about

day-to-day activities. This

their marine environment is grounded in the actual activity of c

expressed quite clearly

fishing. To be a successful fisher in the Solomon Islands, in a

indigenous habitat

knowledge,

identification and monitoring is crucial. Each habitat w

"cumulative has different species associated

body of with it that follow certain en

knowled

through vironmental parameters such as changes

generations by in tide andcultu

moon

relationshipphases, of living

and each requires being

different baits and gear types (see

one another and with their environment" (Berkes Lauer and Aswani 2009 for a detailed description). Habitat

1993:3). A growing body of literature, however, questions change is common in these dynamic environments, and fish

this conceptualization of knowledge. Scholars from a ers must develop the ability to perceive habitat changes and

number of disciplines disagree with the assumption that adapt their practices accordingly (Lauer and Aswani 2010).

knowledge is "in the head," separated from the lived-in Even though fishers most certainly memorize certain aspects

world (Ellen et al. 2000; Ingold 2000; Kightley et al. of the local environment like the name and location of fishing

2013; Lave 1988; Richards 1993; Scott 1998; Stone grounds, and other nomenclature (e.g., fish names and behav

2007; Zarger 2011). In fact, Solomon Islanders' own con iors, gear types), this information is continually regenerated

ceptions of knowledge parallel this view in that they privwithin the context of frequent fishing forays and inseparable

from the process of perceiving subtle variations in environ

ilege the perceived outcomes of practical activities rather

than the metaphysical or abstract (Hviding 1996; Lauer

mental conditions as they unfold while out on the lagoon

and Aswani 2009). A variety of labels such as tacit fishing. Fishing is almost never taught formally or transmitted

knowledge, metis, situated practices, or skill have through oral instruction; rather it is acquired by youngsters

emerged that stress how knowledge and knowing is intrin through watching and fishing with others who are more adept.

sically dynamic, performed, and improvised, and cannot By the time a fisher is in his mid- to late-teens, he or she has

be separated from the context in which they are applied. developed the sensibilities and dispositions necessary to detect

From this processural or practice perspective, knowledge currents, wind conditions, bait fish movements, or habitat

is never fully stable and durable. It is continually regen change, but this knowledge is not a topic of conversation

erated, a process that entails what has been described as and is not necessarily orally transmitted. Moreover, as stated

"situated messiness" (Tumbull 2000:39), where new in above, tsunami-induced changes are typically not within the

formation about the environment or improvements in horizon of a Solomon Island fisher's environmental sensibil

technique intermingle with more established modalities ity. It was the exposure of salaried workers to the global dis

of knowing. course about the effects of tsunamis that tuned them into the

This alternative conception of knowledge encourages us to possibility that environments might change after tsunamis. A

approach the ecological change detection we assessed in situated-practice approach to knowledge provides a theoreti

Vonavona Lagoon not as bits of information about the envi cal basis to understand not only why a fisher's social network

ronment, but rather a situated practice. Therefore, villagers (in this article defined as important social acquaintances) has

who earn salaries and, as a result, were exposed to media little influence on his or her skills, but also how IEK and

reports about ecological change associated with the tsunami global knowledge can intermingle.

were not receivers of specific information about the effects of When we consider the results of our social network analy

the tsunami on the local marine ecology, rather their reper sis from a practice-based approach to IEK, it suggests that a

toires of understanding were expanded, altering their percep different kind of social network may be more important, such

tion of the environment in a way that sensitized them to the as a fisher's fishing partners. It is within what Lave and

possibility of tsunami-induced ecological changes. Our results Wenger (1991) call 'communities of practice' that skills and

suggest that this process of sensitization was driven by sala expertise are maintained and regenerated. For fishers, their

ried workers' exposure to print, TV, and online news media primary community of practice would be the group of fishers

rather than through their social networks. It is quite possible

with whom they fish on a regular basis. An important avenue

that salaried workers' social networks might extend outside of future research would be to explore the effect these various

Springer

This content downloaded from

132.174.250.76 on Wed, 20 Apr 2022 06:27:33 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

Hum Ecol (2016) 44:33-46 45

kinds of social (2011). Linking Indigenous and Scientific Knowledge

networks of Climate

have o

Change. Bioscience 61: 477-484.

and modalities of knowing.

Aswani, S. (1998). Patterns of Marine Harvest Effort in Southwestern

To conclude, we highlight

New Georgia, Solomon Islands: Resource Management or an i

Our results suggest that some

Optimal Foraging? Ocean and Coastal Management 40: 207-235.

at detecting change and

Aswani, S., and Lauer, M. (2014). Indigenous there

people's Detection of

useful in the Rapid Ecological Change. Conservationof

design Biology 28: 820-828.

resou

Aswani, S., M. Lauer, P. Weiant, L. Geelen, and S. Herman. (2004). The

disaster risk-reduction mit

Roviana and Vonavona marine resource management project, final

against importing assumptions

report, 2000-2004. Department of Anthropology, University of

knowledge and about

California, Santa Barbara. who are

experts. The Atran, S., and Medin,

fact D. L. (2008). The Native

that Mind and the Cultural

salaried

are Construction

exclusively of Nature. Life and Mind. MIT Press, Cambridge.

fishers were

Atran, S., Medin, D., Ross, N., Lynch, E., Vapnarsky, V., Ek, E. U., Coley,

ecological change

after the t

J., Timura, C., and Baran, M. (2002). Folkecology, Cultural

spread assumptions that local

Epidemiology, and the Spirit of the Commons: A Garden

most experience

Experiment engaging

in the Maya Lowlands, 1991-2001. Current wit

and Wagner Anthropology 43: 421-450.Even

2003). local

Berkes, F. 1993. Traditional Ecological Knowledge in Perspective. In

consider salaried workers as f

Inglis, J. (ed.), Traditional Ecological Knowledge Concepts and

individuals would have been m

Cases. International Program on Traditional Ecological

on our 'expert network'

Knowledge: International Development Research Centre, socia

Ottawa,

volved in Ont., Canada, pp. 1-10.

resource management

cognizant Berkes, F., Colding,

the J., and Folke, C. (2000). Rediscovery

these of kinds of Traditional of

Ecological Knowledge as Adaptive Management. Ecological

edge generation in indigenous

Applications 10: 1251-1262.

edge may put Berlin,

be put

B. (1992). Ethnobiological into pract

Classification: Principles of

intersection of local

Categorization of Plants and Animalsand glob

in Traditional Societies.

IEK as a complex,

Princeton University multifacet

Press, Princeton.

more Bicker, A.,sensitive,

inclusive, Sillitoe, P., and Pottier, J. (2004). Investigating Local

and,

Knowledge: New Directions, new Approaches. Ashgate, Aldershot.

agement that policies contribut

Bodin, O., and Prell, C. (2011). Social Networks and Natural Resource

communities over the

Management: Uncovering the Social Fabric long-ter

of Environmental

Governance. Cambrdige University Press, Cambridge.

Borgatti, S. P., M. G. Everett, and L. C. Freeman. (2002). Ucinet for

Acknowledgments Windows: Software Many

for social network analysisthanks

for supportingBorgatti,

this S. P., Mehra, A., research.

Brass, D. J., and Labianca, G. (2009). NetworkIn p

Tungama Gua, and Analysis in theLawrence

Social Sciences. Science 323: 892-895. Buka

Campanella and Ben Nugent

Boster, J. S. (1986). for

Exchange of Varieties and Information thei

Between

Campbell for

her Aguaruna

assistance with

Manioc Cultivators. American Anthropologist 88: 428 sta

Sore, Permanent 436.Secretary of the S

ment, Conservation,

Brokensha, D., Warren, D. and Meteoro

M., and Werner, O. (1980). Indigenous

input of three anonymous reviewe

Knowledge Systems and Development. University Press of

Human Dimensions

America, Washington. and Social

#0827022) and San Diego State Univ

Davis, A., and Wagner, J. R. (2003). Who Knows? On the Importance of

support for this research.

Identifying "Experts" When Researching Local Ecological

Knowledge. Human Ecology 31: 463-489.

Compliance With Ethical

Drew, J. (2005). Standar

Use of Traditional Ecological Knowledge in Marine

Conservation. Conservation Biology 19: 1286-1293.

Conflict of interest The authors h

Ellen, R. F. (ed.) (2007). Modem Crises and Traditional Strategies: Local

proval for this research was granted

Ecological Knowledge in Island Southeast Asia. Berghahn Books,

dation. InformedNew consent

York. was obtain

this study.

Ellen, R., Parkes, P., and Bicker, A. (eds.) (2000). Indigenous

Environmental Knowledge and its Transformations: Critical

Anthropological Perspectives. Harwood Academic Publishers,

Amsterdam.

Escobar, A. (1999). After Nature: Steps to an Anti-Essentialist Political

Ecology. Current Anthropology 40: 1-30.

References

Furusawa, T. (2009). Changing Ethnobotanical Knowledge of the

Roviana People, Solomon Islands: Quantitative Approaches to its

Agrawal, A. (1995). Dismantling the Divide Between Indigenous and Correlation With Modernization. Human Ecology 37: 147-159.

Scientific Knowledge. Development and Change 26: 413-439. Gomez-Baggethun, E., and Reyes-Garcia, V. (2013). Reinterpreting

Alexander, C., Bynum, N., Johnson, E., King, U., Mustonen, T., Neofotis, Change in Traditional Ecological Knowledge. Human Ecology 41:

P., Oettle, N., Rosenzweig, C., Sakakibara, C., and Shadrin, V. 643-647.

Springer

This content downloaded from

132.174.250.76 on Wed, 20 Apr 2022 06:27:33 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

46 Hum Ecol (2016) 44:33-46

Goodman, A., A Deadlock? Quantitative Research

Purkis, J. S. fromJ.,

a Native Amazonian

and Phi

Sensing. Guide for

Society. Human A Mapping,

Ecology 35: 371-377. Mo

Springer, New Reyes-Garcia, V., Molina, J. L., Calvet-Mir, L., Aceituno-Mata, L.,

York.

Green, A., P. Lokani, W.

Lastra, J. J., Ontillera, R., Parada,Atu, P.

M., Pardo-de-Santayana, M., Ram

(2006). Solomon Rigat, Islands

M., Valles, J., and Gamatje, T.marine

(2013). "Tertius Gaudens": asse

survey conducted GermplasmMay Exchange Networks and 13 to

Agroecological June

Knowledge

Country Report No.Among Home1/06. Gardeners in the Iberian Peninsula. Journal of

Gupta, A. (1998). Ethnobiology and Ethnomedicine 9: 53.

Postcolonial Developm

of Modern India.

Richards,Duke University

P. (1993). Cultivation: Knowledge or Performance? In Hobart, Pr

Hays, T. E. (1976). M. An Empirical

(ed.), An Anthropological Critique ofDevelopment: The GrowthMetho

Categories in Ethnobiology.

of Ignorance. Routledge, London, pp. 61-78. America

Hobart, M. (ed.) Ross,

(1993). An

N. (2002). Lacandon-Maya Intergenerational Anthropo

Change and the

The Growth of Ignorance.

Erosion of Folkbiological Knowledge. In Stepp,Routledge

J. R., Wyndham,

Hviding, E. (1996). E. S., andGuardians of

Zarger, R. K. (eds.), Ethnobiology and Biocultura! Mar

Politics in Maritime

Diversity. International SocietyMelanesia.

of Ethnobiology, Athens, pp. 585 U

Honolulu. 592.

Ingold, T. (2000). The Perception of the Environment: Essays onSchultes, R. E. (1994). Burning the Library of Amazonia. The Sciences

Livelihood, Dwelling and Skill. Routledge, London. 34:24-31.

Katona, Z., Zubcsek, P. P., and Sarvary, M. (2011). Network Effects and Scott, J. C. (1998). Seeing Like a State: How Certain Schemes to Improve

Personal Influences: The Diffusion of an Online Social Network. the Human Condition Have Failed. Yale University Press, New

Journal of Marketing Research 48: 425-443. Haven.

Kightley, E., Reyes-Garcia, V., Demps, K., Magtanong, R., Ramenzoni,

Solomon Islands Government. (2011). Report on the 2009 population

V., Thampy, G., Gueze, M., and Stepp, J. (2013). An Empirical and housing census: Basic tables and census description.

Comparison of Knowledge and Skill in the Context of Traditional Solomon Islands National Statistics Office

Ecological Knowledge. Journal of Ethnobiology and Spoon, J. (2011). The Heterogeneity of Khumbu Sherpa Ecological

Ethnomedicine 9: 71. Knowledge and Understanding in Sagarmatha (Mount Everest)

Lauer, M. (2012). Oral Traditions or Situated Practices? Understanding National Park and Buffer Zone, Nepal. Human Ecology 39: 657

how Indigenous Communities Respond to Environmental Disasters. 672.

Human Organization 71: 176-187. Stone, G. D. (2007). Agricultural Deskilling and the Spread of

Lauer, M., and Aswani, S. (2009). Indigenous Ecological Knowledge as Genetically Modified Cotton in Warangal. Current Anthropology

Situated Practices: Understanding fishers' Knowledge in the 48: 67-103.

Western Solomon Islands. American Anthropologist 111:317-329. Taylor, F. W., Briggs, R. W., Frohlich, C., Brown, A., Hornbach, M.,

Lauer, M., and Aswani, S. (2010). Indigenous Knowledge and Long Papabatu, A. K., Meltzner, A. J., and Billy, D. (2008). Rupture

Term Ecological Change: Detection, Interpretation, and Responses Across arc Segment and Plate Boundaries in the 1 April 2007

to Changing Ecological Conditions in Pacific Island Communities. Solomons Earthquake. Nature Geoscience 1: 253-257.

Environmental Management 45: 985-997. Tumbull, D. (2000). Masons, Tricksters and Cartographers: Comparative

Lave, J. (1988). Cognition in Practice: Mind, Mathematics, and Culture in Studies in the Sociology of Scientific and Indigenous Knowledge.

Everyday Life. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge. Harwood Academic, Amsterdam.

Lave, J., and Wenger, E. (1991). Situated Learning: Legitimate Peripheral

Vandebroek, I., and Balick, M. J. (2012). Globalization and Loss of Plant

Participation Learning in Doing. Cambridge University Press, Knowledge: Challenging the Paradigm. PLoS One 7, e37643.

Cambridge. Wasserman, S., and Faust, K. (1994). Social Network Analysis: Methods

Mercer, J., Dominey-Howes, D., Kelman, I., and Lloyd, K. (2007). The and Applications. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge.

Potential for Combining Indigenous and Western Knowledge in Zarger, R. (2011). Learning Ethnobiology. In Anderson, E. N., Pearsall,

Reducing Vulnerability to Environmental Hazards in Small Island D., Hunn, E., and Turner, N. (eds.), Ethnobiology. Wiley-Blackwell,

Developing States. Environmental Hazards 7: 245-256. Hoboken, pp. 371-387.

Ohmagari, K., and Berkes, F. (1997). Transmission of Indigenous Zarger, R., and Stepp, J. (2004). Persistence of Botanical Knowledge

Knowledge and Bush Skills Among the Western James Bay Cree Among Tzeltal Maya Children. Current Anthropology 45:413-418.

Women of Subarctic Canada. Human Ecology 25: 197-222. Zent, S. (2009). A Geneology of Scientific Representations of Indigenous

Pickering, A. (1995). The Mangle of Practice: Time, Agency, and Knowledge. In Heckler, S. (ed.), Landscape, Process, and Power:

Science. University of Chicago Press, Chicago. Re-Evaluating Traditional Environmental Knowledge. Berghahn

Reyes-Garcia, V., Vadez, V., Byron, E., Apaza, L., Leonard, W. R., Perez, Books, New York, pp. 19-67.

E., and Wiikie, D. (2005). Market Economy and the Loss of Folk Zent, S. (2013). The Processsural Perspectives on Traditional

Knowledge of Plant Uses: Estimates from the Tsimane' of the Environmental Knowledge: Continuity, Erosion, Transformation,

Bolivian Amazon. Current Anthropology 46: 651-656. Innovation. In Ellen, R., Lycett, S. J., and Johns, S. E. (eds.),

Reyes-Garcia, V., Vadez, V., Huanca, T., Leonard, W. R., and McDade, T. Understanding Cultural Transmission in Anthropology: A Critical

(2007). Economic Development and Local Ecological Knowledge: Synthesis. Berghahn Books, New York, pp. 213-265.

Springer

This content downloaded from

132.174.250.76 on Wed, 20 Apr 2022 06:27:33 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

You might also like

- Not Just An Engineering Problem - The Role of Knowledge and Understanding of Ecosystem Services For Adaptive Management of Coastal ErosionDocument16 pagesNot Just An Engineering Problem - The Role of Knowledge and Understanding of Ecosystem Services For Adaptive Management of Coastal ErosionSoy tu aliadoNo ratings yet

- Biodiversity Loss and Its Impact On Humanity: Nature June 2012Document11 pagesBiodiversity Loss and Its Impact On Humanity: Nature June 2012Alejandro PerezNo ratings yet

- Newman HumanDimensions 2021Document10 pagesNewman HumanDimensions 2021CHrisNo ratings yet

- Journal of Arid Environments: Carina Llano, Víctor Dur An, Alejandra Gasco, Enrique Reynals, María Sol Z ArateDocument9 pagesJournal of Arid Environments: Carina Llano, Víctor Dur An, Alejandra Gasco, Enrique Reynals, María Sol Z ArateBenjan't PujadasNo ratings yet

- Global Environmental Change: A B C D e F GDocument16 pagesGlobal Environmental Change: A B C D e F Gmariajose garciaNo ratings yet

- How To Partner With People in Ecological ResearchDocument8 pagesHow To Partner With People in Ecological ResearchAndré Luiz SilvaNo ratings yet

- Rmrs 2017 Hoagland s002Document15 pagesRmrs 2017 Hoagland s002Erik NandaNo ratings yet

- Conservation Biology and Traditional Ecological Knowledge: Integrating Academic Disciplines For Better Conservation PracticeDocument9 pagesConservation Biology and Traditional Ecological Knowledge: Integrating Academic Disciplines For Better Conservation PracticeSombra del CronopioNo ratings yet

- Ecol Appl 2003Document12 pagesEcol Appl 2003Cristobal Garcia GarciaNo ratings yet

- Jurnal Internasional-DikonversiDocument24 pagesJurnal Internasional-Dikonversisarinah srnhNo ratings yet

- Traditional Ecological Knowledge and Community Resilience To Environmental eDocument11 pagesTraditional Ecological Knowledge and Community Resilience To Environmental eganjarruntikoNo ratings yet

- Ecological Succession in A Changing World: Cynthia C. Chang - Benjamin L. TurnerDocument7 pagesEcological Succession in A Changing World: Cynthia C. Chang - Benjamin L. TurnerRismatul JannahNo ratings yet

- Weaving Indigenous Knowledge and Sustainability SciencesDocument12 pagesWeaving Indigenous Knowledge and Sustainability SciencesNurullina FajriNo ratings yet

- 2021 - Intersecting Social Science and ConservationDocument16 pages2021 - Intersecting Social Science and ConservationJuan Reyes ValentinNo ratings yet

- 2017 Human Influences On EvolutionDocument13 pages2017 Human Influences On EvolutionVale ContrerasNo ratings yet

- Grigoratou Et Al 2022Document5 pagesGrigoratou Et Al 2022Muhamad FaiqNo ratings yet

- The Desert Experience Evaluating The Cultural Ecosystem Services of DrylandsDocument15 pagesThe Desert Experience Evaluating The Cultural Ecosystem Services of DrylandsDanira Rios QuijadaNo ratings yet

- Remote Communities Vulnerability to Global ChangesDocument13 pagesRemote Communities Vulnerability to Global Changesmichael17ph2003No ratings yet

- Weaving IndigenousDocument12 pagesWeaving IndigenoushanmusicproductionsNo ratings yet

- Improving The American Eel Fishery Through The Incorporation of IndigenousDocument18 pagesImproving The American Eel Fishery Through The Incorporation of IndigenoussergiolefNo ratings yet

- Philippines Article PDFDocument13 pagesPhilippines Article PDFAmeflor DumaldalNo ratings yet

- Arthur JL2021Document31 pagesArthur JL2021Carlos Sanz AlcaideNo ratings yet

- Local Ecological KnowledgeDocument23 pagesLocal Ecological KnowledgePrio SambodoNo ratings yet

- Alternatif approach to co-designDocument7 pagesAlternatif approach to co-design杨淑惠No ratings yet

- Environmental Sociology An IntroductionDocument12 pagesEnvironmental Sociology An IntroductionEditor IJTSRDNo ratings yet

- Clam Hunger and The Changing Ocean: Characterizing Social and Ecological Risks To The Quinault Razor Clam Fishery Using Participatory ModelingDocument29 pagesClam Hunger and The Changing Ocean: Characterizing Social and Ecological Risks To The Quinault Razor Clam Fishery Using Participatory Modelingmarianamt1992No ratings yet

- Meijeretal.-2021-Mangrove-mudflatconnectivityshapesbenthiccommuDocument12 pagesMeijeretal.-2021-Mangrove-mudflatconnectivityshapesbenthiccommuRowena BrionesNo ratings yet

- Creating Space For Interdisciplinary Marine and Coastal Research Five Dilemmas and Suggested ResolutionsDocument15 pagesCreating Space For Interdisciplinary Marine and Coastal Research Five Dilemmas and Suggested ResolutionsWen VelaNo ratings yet

- Berkes 2000 - Rediscovery of TEK As Adaptive ManagementDocument13 pagesBerkes 2000 - Rediscovery of TEK As Adaptive ManagementJona Mae VictorianoNo ratings yet

- Panarchy and Community Resilience - BerkesDocument9 pagesPanarchy and Community Resilience - BerkessnoveloNo ratings yet

- Fmars-08-543075 220605 002413Document18 pagesFmars-08-543075 220605 002413Divvya IndranNo ratings yet

- Ecological Literacy and Socio Demographics Who Are The Most Eco Literate in Our Community and WhyDocument15 pagesEcological Literacy and Socio Demographics Who Are The Most Eco Literate in Our Community and WhyMaría Teresa Muñoz QuezadaNo ratings yet

- Jurnal Biodiversitas SulawesiDocument26 pagesJurnal Biodiversitas SulawesiAndini DwiyantiNo ratings yet

- BoillatDocument17 pagesBoillat20 15No ratings yet

- Cole 2021Document16 pagesCole 2021Romi MitroliaNo ratings yet

- Rediscovery of Traditional Ecological Knowledge As Adaptive Management, 2000Document12 pagesRediscovery of Traditional Ecological Knowledge As Adaptive Management, 2000Sol JeniNo ratings yet

- Wang 2021Document12 pagesWang 2021A.Rahmat MuhammadNo ratings yet

- Shirk - Et - Al - 2012 - Public Participation in Scientific ResearchDocument20 pagesShirk - Et - Al - 2012 - Public Participation in Scientific ResearchMaicon Luppi100% (1)

- Incorporating ecosystem services into environmental management of deep-seabed miningDocument18 pagesIncorporating ecosystem services into environmental management of deep-seabed miningNaomy ChristianiNo ratings yet

- Es 2013 5846 PDFDocument6 pagesEs 2013 5846 PDFHéctor Navarro AgullóNo ratings yet

- This Content Downloaded From 132.174.250.76 On Wed, 20 Apr 2022 06:27:19 UTCDocument16 pagesThis Content Downloaded From 132.174.250.76 On Wed, 20 Apr 2022 06:27:19 UTCSERGIO HOFMANN CARTESNo ratings yet

- Pereira 2010Document7 pagesPereira 2010Oumayma BensalahNo ratings yet

- Influence of Green Infrastructure On Residents' Endorsement of The New Ecological Paradigm in Lagos, NigeriaDocument15 pagesInfluence of Green Infrastructure On Residents' Endorsement of The New Ecological Paradigm in Lagos, NigeriaJournal of Contemporary Urban AffairsNo ratings yet

- Unanue Et Al 2016 FinalDocument13 pagesUnanue Et Al 2016 FinalDaniela ZuninoNo ratings yet

- Understanding Mental Constructs of Biodiversity: Implications For Biodiversity Management and ConservationDocument12 pagesUnderstanding Mental Constructs of Biodiversity: Implications For Biodiversity Management and ConservationDeisy QuevedoNo ratings yet

- Conservation Biogeography: Assessment and Prospect: Special PaperDocument22 pagesConservation Biogeography: Assessment and Prospect: Special PaperRoknuzzaman RabbyNo ratings yet

- Enviro Toxic and Chemistry - 2009 - Ares - Time and Space Issues in Ecotoxicology Population Models Landscape PatternDocument13 pagesEnviro Toxic and Chemistry - 2009 - Ares - Time and Space Issues in Ecotoxicology Population Models Landscape PatternRodel Delos ReyesNo ratings yet

- RSPB 2019 1882Document10 pagesRSPB 2019 1882CubeBoxNo ratings yet

- Terrestrial Biomes A Conceptual ReviewDocument13 pagesTerrestrial Biomes A Conceptual ReviewbrunoictiozooNo ratings yet

- Ocean & Coastal Management: Annisa Triyanti, Maarten Bavinck, Joyeeta Gupta, Muh Aris MarfaiDocument9 pagesOcean & Coastal Management: Annisa Triyanti, Maarten Bavinck, Joyeeta Gupta, Muh Aris MarfainurilNo ratings yet

- Silabus PDFDocument56 pagesSilabus PDFFiani B'LoversNo ratings yet

- Addressing The Interplay of Poverty and The Ecology of LandscapesDocument12 pagesAddressing The Interplay of Poverty and The Ecology of LandscapesNataliaNo ratings yet

- Integrating Ecosystem Service Importance and Ecological Sensitivity To Identify Priority Areas For Ecological Conservation and Restoration in MiyunDocument14 pagesIntegrating Ecosystem Service Importance and Ecological Sensitivity To Identify Priority Areas For Ecological Conservation and Restoration in Miyunvenuri silvaNo ratings yet

- Coria 2012Document9 pagesCoria 2012nizar hardiansyah nasirNo ratings yet

- Burke Etal 2021Document11 pagesBurke Etal 2021Fabi BêlemNo ratings yet

- Adaptation To Variable Environments Indus Northwest India (Petrie Et Al, Feb2017Document30 pagesAdaptation To Variable Environments Indus Northwest India (Petrie Et Al, Feb2017Srini KalyanaramanNo ratings yet