Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Pediatric PIV Study Characteristics

Uploaded by

pareshOriginal Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Pediatric PIV Study Characteristics

Uploaded by

pareshCopyright:

Available Formats

Lynelle Foster, RN, BN, MN

Marianne Wallis, RN, BSc(Hons), PhD

Barbara Paterson, RN, EM, NICC, BEd

Heather James, RN, BN, MN

A Descriptive Study of Peripheral

Intravenous Catheters in Patients

Admitted to a Pediatric Unit in One

Australian Hospital

indications for use, dwell time, and reasons for

Abstract removal, together with nursing actions. The

results showed that most PIVs were removed

within 72 hours. In 6.6% of cases, some degree

• • • • of phlebitis was present at PIV removal. The

risk of phlebitis increased when the PIV

Over a 5-month period, 496 peripheral remained in place longer, the child was younger,

intravenous catheters (PIVs) inserted into or medication was administered. The greatest

neonates, infants, and children were risk was age, with neonates being 51/2 times

prospectively studied. Data were collected on more likely to have some degree of phlebitis

demographic patient characteristics, PIV than non-neonates.

Lynelle Foster has worked in the field of infusion therapy since 1992 and is the Clinical Nurse Consultant of Parenteral Therapy at

Gold Coast Hospital in Queensland, Australia.

Marianne Wallis has been the Chair of Clinical Nursing Research at Gold Coast Health Services District and Griffith University,

Queensland, Australia since January 2000.

Barbara Paterson has worked in the field of pediatrics for more than 20 years. She is the Nurse Educator in the Paediatric Unit,

Gold Coast Hospital in Queensland, Australia.

Heather James has been an Associate Lecturer in the School of Nursing, Griffith University, Queensland, Australia since 1999.

Address correspondence to: Lynelle Foster, Parental Therapy Department, Gold Coast Hospital, Office 18, 1st Floor, Southport,

Queensland, QLD 4215 (e-mail: Lynelle_Foster@health.qld.gov.au).

Vol. 25, No. 3, May/June 2002 159

may seem adequate for preventing infections associated

• BACKGROUND TO THE STUDY with PIVs, issues such as the appropriate use of an anti-

septic to prepare the skin before PIV insertion and the

maintenance of the dressing on the PIV exit site also are

T

he setting used for this study was the pediatric implicated.9,10

unit at the Gold Coast Hospital (GCH), Aus- An antiseptic skin solution should always be used

tralia. This pediatric unit admits approximately before insertion of a PIV. A prospective randomized

3,700 patients each year, including neonates, trial of agents used for cutaneous antisepsis demon-

infants, and children. Neonates are defined as babies strated that 2% aqueous chlorhexidine was superior to

younger than 28 days. Infants are in the first year of life, either 10% povidone iodine or 70% alcohol in prevent-

and children are defined as 1 to 16 years of age. All ing catheter-related infection.9 However, the 2% aque-

pediatric medical and nursing services are offered at ous chlorhexidine solution is not yet available in

GCH except chemotherapy initiation, long-term venti- Australia. Direct comparisons of aqueous and alcoholic

lation, and cardiac surgery. solutions of chlorhexidine have not been undertaken.

The Infusion Nursing Standard of Practice, estab- However, an alcoholic chlorhexidine solution combines

lished by the Infusion Nurses Society (INS)1 and Guide- the benefits of rapid action and excellent residual

line for Prevention of Intravascular Device-Related antimicrobial activity.25 To maintain skin integrity and

Infection, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention prevent chlorhexidine absorption in neonates, it is sug-

([CDC]. Atlanta, Ga: US Department of Health and gested that after the solution has been allowed to dry

Human Services; 1996) are used to guide clinical infu- for 30 seconds, it should be removed completely using

sion practice at GCH. The issue of frequency of replace- sterile saline solution.10

ment of peripheral intravenous catheters (PIVs) in The most common dressing type used for PIV exit

children is, however, unresolved with both INS and the sites in adults is a sterile, transparent, semipermeable

CDC. The pediatric nursing staff at GCH identified a membrane dressing. This dressing is popular because it

number of issues related to PIV insertion, use, and dwell reliably secures the catheter, permits continuous visual

time that required further exploration. inspection of the exit site, and repels water.9,11 However,

it is not uncommon in the pediatric population to use

unsterile tape to secure PIVs.12,26,27 Infection control prac-

• LITERATURE REVIEW tices together with the type of catheter play an important

role in the prevention of complications with PIVs.

The epidemiology of intravascular device complications

is less well described for pediatrics than for adults, and

there are limitations to the existing data. First, a thor- • TYPE OF PERIPHERAL INTRAVENOUS

ough search of the literature, the Cochrane Collabora- CATHETER

tion, and the Joanna Briggs Institute failed to identify

any systematic reviews of pediatric PIV use. Second, The guidelines for choosing the appropriate PIV gauge

most identified studies were uncontrolled and either ret- are the same for children as for adults. That is, the

rospective or prospective. Third, most of the available smallest device possible should be used to deliver the

data were gathered only in neonatal or pediatric inten- prescribed therapy.28 Manufacturers market a number

sive care units and not in general pediatric wards.2-6 of peripheral devices, and although personal preference

Research studies investigating issues related to com- is a consideration, the clinician should consider other

plications of peripheral intravenous therapy have factors such as type and duration of therapy when mak-

focused on infection control practices,7-12 types of ing a selection. The winged-steel (scalp and butterfly)

PIVs,13,14 PIV dwell times and patency maintenance,15-20 needles were designed specifically for pediatric use, but

IV administration set changes, the use of add-on IV because of the risk for dislodgement and subsequent

devices,21,22 and the use of IV nursing teams.23,24 These injury, they have been replaced by over-the-needle

are considered individually in the following discussion. PIVs.29 These devices consist of a catheter over an inter-

nal stylet. The original catheters were made from

Teflon, a stiff, fluorine-based plastic that can kink.

Recent improvements in the quality and properties of

• INFECTION CONTROL PRACTICES polyurethane have resulted in a softer, high-strength

material patented as Vialon, which becomes pliable

Adherence to handwashing and aseptic technique are once inside the vein.6,14 Catheter type, dwell time, and

accepted worldwide as the cornerstone for prevention patency maintenance have been implicated in PIV com-

of IV catheter-related infection. Although this alone plications.

160 Journal of Infusion Nursing

However, outbreaks have occurred, and after these out-

• PERIPHERAL INTRAVENOUS breaks it was recommended that IV administration sets

CATHETER DWELL TIME AND be replaced at 24-hour intervals.

PATENCY MAINTENANCE Researchers currently investigating the frequency of

administration set changes recommend that 48 to 72

The recommendation to replace short PIVs in adults and hours is the acceptable time between changes.11,28 As of

rotate insertion sites every 48 to 72 hours to minimize the this writing, research projects are evaluating 96-hour set

risk of phlebitis is well documented in the litera- changes.21 However, no available data specifically

ture.9,11,15,16,28 However, the recommendation to replace relates to pediatric set changes. Whereas it is established

PIVs routinely in children remains unresolved.11,28 that more frequent PIV and subsequent administration

One comprehensive epidemiologic study30 of 3,094 set manipulations are associated with a greater risk of

adult patients with 5,161 total episodes of PIVs found an infection, the impact of an infusion team on PIV com-

overall phlebitis rate of 2.3% and a catheter-associated plications also has been explored.

bacteremia rate of 0.08%. The study concluded that the

current recommendation to replace adult PIVs every 48

to 72 hours seemed appropriate. However, a prospective • INTRAVENOUS NURSING TEAMS

study of 303 critically ill children with 654 PIV inser-

tions2 established a phlebitis rate at 13%, yet concluded

that PIVs could be maintained safely up to 6 days. Although it has been demonstrated that infusion nurs-

Another pediatric study31 reviewed 525 patients with ing teams reduce catheter-related complications in the

642 PIVs and reported a phlebitis rate of 1.1%. The adult population, no studies were found that explored

findings indicated that the overall risk of complications this topic in the pediatric population. One prospective

was extremely low and would not be reduced by routine controlled study showed a phlebitis rate of 32% in the

PIV replacements. It is difficult to compare these results control group, as compared with a phlebitis rate of

because no standardized scale was used to establish the 15% in the group under the care of the infusion team.37

phlebitis rates. A randomized prospective controlled study24 also

Whether saline or heparin flush solution should be showed a significant reduction in both local and bac-

used to maintain PIV patency and minimize infusion teremic complications of PIVs. The control group was

phlebitis in children remains a matter of controversy.17 reported to have an inflammation rate of 21.7%, as

One pediatric study found no significant differences in compared with a rate of 7.9% for patients whose

PIV patency or phlebitis between saline and heparin flush catheters were maintained by an infusion team member.

solutions.18 However, another study of children with PIVs Another study23 also established a 35% reduction in pri-

demonstrated longer durations of patency in catheters mary nosocomial bloodstream infections. However, all

flushed with 10 U/ml heparin flush solution.19 When PIV these results should be interpreted cautiously because

dwell time and patency maintenance are investigated, IV the definitions for phlebitis and bacteremia varied.

administration set changes should be considered. According to one study, the use of infusion nurses for

insertion of PIVs in children is more cost effective than

the use of registered nurses or medical officers for pro-

vision of this service.38 Unfortunately, the outcomes in

this study were not measured in terms of infection pre-

• INTRAVENOUS ADMINISTRATION vention.

SET CHANGES AND USE Widely used in the pediatric population, PIVs pro-

OF ADD-ON DEVICES vide the means for administering fluids, blood products,

antibiotics, opioids, and other medications. However,

The frequency of IV administration set changes and the serious complications are associated with the insertion

number of times the catheter hub is exposed have an and management of these devices. Infectious complica-

impact on the potential for infection32-34: the more inter- tions are the most serious.

ruptions, the greater the potential for the entry of

microorganisms. The use of injection ports, three-way

taps, and needleless IV access systems all have been

examined in relation to potential risk of infection with • PHLEBITIS

intravascular catheters.35,36 Several investigators have

shown that intrinsic contamination of unused intra- Phlebitis is a condition in which inflammation of the

venous fluid is rare. It has been estimated that the inci- intima of the vein occurs. It is characterized by pain and

dence of catheter-related infection from contaminated tenderness along the course of the vein, erythema, and

intravenous fluids is less than 1 per 1,000 infusions.9 inflammatory swelling with a feeling of warmth at the

Vol. 25, No. 3, May/June 2002 161

site. It can be associated with the administration of age, gender, and diagnosis; factors related to insertion

chemicals (chemical phlebitis), misplacement of the such as site and time of insertion; uses of the catheter;

catheter (mechanical phlebitis), or proliferation of bac- reasons for and timing of removal; adverse events and

teria (bacterial phlebitis).38 nursing actions after removal.

Postinfusion phlebitis also is commonly reported. The INS scale for phlebitis was designed for use with

This condition becomes evident 48 to 96 hours after adults because it includes subjective assessment of

catheter removal.39 Phlebitis is considered important pain.28 One problem encountered by the research team

because it may indicate bacterial colonization, which in was that pain could not be assessed accurately in pre-

turn can lead to catheter-related bloodstream infection verbal children when data were collected by multiple

(CR-BSI).39,40 The final consequences can be prolonged nursing staff rather than one trained research assistant.

hospitalization, costly treatment, loss of necessary Consequently, the registered nurse removing the

access, and sometimes even death. Although guidelines catheter was asked to observe the site and check a vari-

and standards for PIV indications, care, and manage- ety of boxes on a data collection instrument, which

ment are readily available for the adult population, staff included erythema, swelling, pain, streak, and palpable

of the pediatric unit at GCH believe these cannot be cord. The researchers then classified the degree of

generalized to children. This issue prompted the authors phlebitis on the scale depicted in Table 1.

to investigate peripheral intravenous practices in the Retrospectively, the clinical nurse who administered

pediatric unit at their facility. parenteral therapy, electronically accessed all the posi-

tive pediatric blood culture results from AUSLAB

(Pathology and Scientific Services Information System)

during the study period. The purpose of this examina-

• METHOD tion was to investigate whether any of these blood-

stream infections were possibly PIV related.

A convenience sample of 496 PIVs was studied prospec-

tively over a 5-month period from June to October

2000. At the time of this study, PIVs were inserted by

the pediatric medical registrars, remaining in place until • PROCEDURE

the catheter dislodged, infiltrated, or was no longer

required. At GCH, Insyte catheters (BD Medical Sys- All pediatric PIVs inserted during the study period were

tems, Franklin Lakes, NJ) and a needleless IV access eligible for inclusion in the study. Data collection forms

system, Interlink (BD Medical Systems), are the stan- were kept with the admission paperwork, and all regis-

dard items used for both adults and children. tered nurses were asked to complete a form for each PIV

Standard IV medical and nursing practice was main- inserted into each patient. The form was completed by

tained throughout the period of data collection. This the registered nurse caring for the patient with the PIV.

involved applying a dermal anesthetic eutectic mixture If the data collected on a form were found to be

of local anesthetic cream at least 60 minutes before PIV incomplete, a member of the research team audited the

insertion in most children older than 2 years, cleansing medical record or interviewed the staff member involved

the skin with a 70% isopropyl alcohol and 1% to maximize data collection. All staff gave informed con-

chlorhexidine swab, and allowing the area to dry. After sent for these interviews. In a number of cases, it was not

insertion of the PIV, unsterile zinc oxide tape 1 cm wide possible to collect all the information related to patient

was placed in a chevron around the catheter. The area demographics or PIV characteristics. Therefore, in the

approximately 20 to 30 mm distal to the catheter exit Results section of this article, the sample sizes will vary.

site, where the tip of the catheter was estimated to To facilitate follow-up evaluation of adverse events,

reside in the vein, was left exposed to facilitate regular each form was identified with a code number. Only the

observation. An arm board then was splinted to the research team had access to the information linking the

limb with wide adhesive tape to immobilize it. There patient to the data collected. This study was approved

was no dressing covering the PIV exit site. The limb dis- by the Gold Coast Health Service District Human

tal to the PIV exit site was observed hourly. Research Ethics Committee.

• DATA COLLECTION • DATA ANALYSIS

Members of the research team, in consultation with Once collected, data were entered into the Statistical

clinicians, developed the data collection instrument. Package for the Social Sciences, version 10, computer

Data were collected on demographic variables such as program (SPSS Inc., Chicago Ill). Descriptive analyses

162 Journal of Infusion Nursing

TABLE 1 one PIV per admission. Of these PIVs, 152 (30.6%) were

Phlebitis Scale inserted into infants (18.5% in neonates), and 344

(69.4%) into children. The mean age of the non-neonates

Grade Clinical Criteria was 5.5 years (range, 1 month to 16 years; SD 4.88 years).

0 0 or 1 sign (erythema, swelling, pain) In this sample, 234 (47.6%) of the catheters were inserted

1 2 signs into girls and 258 (52.4%) into boys. Because this sample

2 3 signs was drawn from a general pediatric population, most of

3 2/3 signs plus streak formation the diagnostically related groupings were included.

4 2/3 signs plus palpable cord

Peripheral Intravenous Catheter

were conducted on the univariate data, which included Characteristics

frequencies, percentages, and measures of central ten-

dency such as mean, standard deviation, and mode. The The most common PIVs inserted in this study were 22-

chi-square test for comparison of proportions was used and 24-gauge catheters. As Table 2 shows, 241 PIVs

to determine significant differences between categorical (49.8%) were inserted into veins of the left upper limb,

variables. Odds ratios and the 95% confidence intervals 219 (45.2%) into veins of the right upper limb, and 23

were calculated for a variety of variables to identify the (4.8%) into veins in the lower limbs.

factors associated with phlebitis. The mean dwell time for PIVs was 42.35 (SD 29.22)

hours. However, the range was from 2.5 hours to 189.5

hours (7.89 days). Nearly 13% (12.9%; n = 63) of the

PIVs remained in place longer than 72 hours, and 5.7%

• LIMITATIONS OF THE METHOD (n = 28) of the PIVs were in place more than 96 hours

(4 days).

This study did not include prospective microbiologic In this study, 470 PIVs (98%) were used for the

assays of PIV exit sites or PIV tips. According to the CDC, administration of medications or fluids. Fluid replace-

isolation of the same organism from a semiquantitative or ment therapy was administered through 451 PIVs

quantitative culture of a catheter segment and from a (91.3%). In addition, 273 PIVs (57.5%) were used for

peripheral blood culture is required for diagnosis of CR- medication administration, 49.8% for IV antibiotics,

BSI.11 In this study, these microbiologic assays were not and 8.2% for a wide variety of other IV medications

conducted prospectively because of funding limitations. including opioids, corticosteroids, bronchodilators,

Therefore, the results related to CR-BSI are only estimates. antiviral agents, insulin, sedatives, antiepileptics, diuret-

ics, antiemetics, and paralyzing agents.

• RESULTS Complications

Demographic Patient Characteristics The most common reason for the removal of a PIV was

that it was no longer required (74.6%; n = 370), either

The sample consisted of 496 PIVs inserted into 436 pedi- because treatment had stopped or the patient was being

atric patients. No more than four different PIVs in any discharged from hospital. A total phlebitis score was

patient were included in the study. Most patients had only calculated for all the PIVs (Table 3).

TABLE 2

Frequencies and Percentages for Catheter Insertion Sites

Veins Used Insertion Site Frequency (%)

Right hand 171 (35.3)

Metacarpal, dorsal venous arch, tributaries of cephalic and basilic

Left hand 216 (44.6)

Right arm 48 (9.9)

Cephalic, basilic, median antebrachial

Left arm 25 (5.2)

Right foot 11 (2.3)

Saphenous, median, marginal, dorsal arch

Left foot 12 (2.5)

Other 1 (0.2)

Total 484 (100.0)

Vol. 25, No. 3, May/June 2002 163

TABLE 3

Frequencies and Percentages of Phlebitis Scale Scores

Grade Clinical Criteria Frequency (%) Cumulative %

0 0 or 1 sign (erythema, swelling, pain) 463 (93.4) 93.4

1 2 signs 26 (5.2) 98.6

2 3 signs 2 (0.4) 99.0

3 2/3 signs plus streak formation 5 (1.0) 100.0

4 2/3 signs plus palpable cord 0 (0.0) 100.0

Total 496 (100.0)

Some degree of phlebitis was present at the removal PIV was in place longer than 72 hours, the risk was

of 33 PIVs (6.6%). Of this group, most (5.2%) were doubled. However, a PIV dwell time of 96 hours did not

associated with grade 1 phlebitis. Two PIVs (0.4%) increase the risk, and a dwell time less than 48 hours did

were associated with grade 2 phlebitis, and five PIVs not reduce the risk.

(1%) with grade 3 phlebitis. No palpable cord was doc-

umented as present for any patient. Because PIV

phlebitis has a demonstrated association with CR- Nursing Actions After Removal

BSI,35,36 blood culture reports also were reviewed.

A retrospective review of positive blood cultures Although it is clear that nurses observed signs of phlebitis

from patients in the study reported via the AUSLAB sys- when removing the 33 PIVs, no exit site skin swabs or

tem during the study period showed that a source for PIV tips were collected to confirm whether these inci-

infection was not found in most cases. Each patient dences were related to bacteria. Although a specific item

from whom a blood culture was collected had a PIV in on the form required nurses to record why a swab was

place. The most common organism isolated was coagu- not sent for culture if a catheter exit site was red or

lase-negative Staphylococcus (ie, normal skin flora). swollen, this item was completed only twice. The first of

This suggests a high rate of specimen contamination at these two completed items included the comment “did

collection, but it also could imply that a PIV may have not persist,” and the second included the comment “IV

been the source. infiltration with no obvious signs of infection.”

For this study, 29 positive blood cultures were ana-

lyzed. In two neonates, a CR-BSI may have developed

from a PIV. The first neonate, during a 32-day length of

stay in a special care nursery, had a PIV in place for 38 • DISCUSSION

hours. This neonate was recorded as having grade 3

phlebitis, and coagulase-negative Staphylococcus was The purpose of this study was to describe PIV use, man-

isolated from the blood culture 3 days after PIV removal. agement, and associated incidence of phlebitis in the

The second neonate had a 36-day length of stay in a spe- pediatric unit at GCH. The studied sample included

cial care nursery. The PIV was in place for 24 hours. neonates, infants, and children. This study was con-

Although this neonate scored zero on the phlebitis scale, cerned with the use, management, and complications of

evidence in the medical record stated that the IV exit site peripheral intravenous catheterization in a general pedi-

was pink. Coagulase-negative Staphylococcus also was atric population. It is clear from the results that most

isolated from the blood 4 days after the PIV was PIVs inserted into neonates, infants, and children are

removed. In both cases, no other source of infection was used more frequently for fluid administration than for

found. There was no record whether the clinical symp- drug administration. The most common drugs adminis-

toms of infection resolved on removal of the PIV. tered are antibiotics, but a wide range of drugs may be

The odds ratios of risk factors associated with given occasionally via the PIV.

phlebitis are shown in Table 4. These data suggest that Whereas most catheters are inserted into the left

phlebitis is related to age, administration of medications upper limb of the child, a large minority are inserted

through the catheter, and PIV dwell time. into the right upper limb. Although handedness does

Neonates and infants, as compared with children not develop until approximately the age of 3 years,41 a

older than 1 year, had more than five times the risk of large proportion of children older than 3 years still have

phlebitis. Administration of IV medication means that PIVs inserted into their dominant hand. This would

the patient had more than double the risk of phlebitis. have implications for the play and learning experiences

The data regarding dwell time is more complicated. If a in which children could engage during hospitalization.

164 Journal of Infusion Nursing

TABLE 4

Univariate Analysis of Risk Factors for Phlebitis

Risk Factor Frequency of Phlebitis Unadjusted Odds Ratio (95% CI) P

Neonate

Non-neonate 16 1.0

Neonate 17 5.58 (2.70–11.55) ⬍ .0001

Age, y

ⱖ1 11 1.0

⬍1 22 5.12 (2.41–10.86) ⬍ .0001

Gender

Female 18 1.0

Male 15 0.74 (0.36–1.51) .515

Catheter size, g

ⱖ 22 28 1.0

⬍ 22 2 0.53 (0.12–2.27) .562

Catheter site

Catheter not in hand 7 1.0

Catheter in hand 26 0.926 (0.39–2.20) 1.000

Drug administration

No drugs 5 1.0

Drugs 28 4.5 (1.17–11.88) .002

Dwell, h

ⱕ 72 23 1.0

⬎ 72 9 2.91 (1.28–6.62) .017

ⱕ 96 30 1.0

⬎ 96 2 1.1 (0.25–4.86) 1.000

ⱕ 48 18 1.0

⬎ 48 14 0.50 (0.24–1.04) .092

CI, confidence interval.

One of the greatest difficulties in examining complica- It is acknowledged that differentiating among

tions such as phlebitis associated with PIVs is the lack of mechanical, chemical, and bacterial phlebitis can be

a common definition. The INS phlebitis scale,28 which clinically difficult, but timely collection of microbio-

ranks degree of phlebitis by how many signs or symptoms logic evidence can assist diagnosis. This study did not

are present, did not function sufficiently with this popula- prospectively assess CR-BSI. However, retrospective

tion because pain assessment in preverbal children is dif- analysis shows that CR-BSI may have developed in two

ficult. The scale developed by the authors of this study neonates from a PIV during the study period. Further-

seems to have utility for use with children. The overall more, it is necessary to educate healthcare professionals

phlebitis rate determined by this instrument was 6.6%. regarding the possible infection risks associated with

The risk of phlebitis increased according to how long the PIVs, thereby increasing their awareness of the require-

PIV had been in place, how young the child was, and ment to collect a PIV exit site skin swab and a PIV tip

whether medication had been administered. The greatest for microbiologic culture when appropriate.

risk was age. Neonates were 51/2 times more likely to have

some degree of phlebitis than non-neonates.

Although the phlebitis rate with the current sample

falls between results from other studies, it is difficult to

• RECOMMENDATIONS

make comparisons because no standardized phlebitis

FOR FUTURE RESEARCH

scale was used. One study31 in a general pediatric popu-

lation (excluding neonates) reported a 1.1% phlebitis The first recommendation from this study is for the

rate with PIVs. Another study conducted in a pediatric development of a standard definition for phlebitis asso-

intensive care unit reported a phlebitis rate of 13%.2 ciated with pediatric PIVs so that further epidemiologic

Vol. 25, No. 3, May/June 2002 165

studies may be accurately compared in this important tenance of peripheral infusion devices. Pediatr Nurs.

area of research. Second, randomized controlled trials 1995;21(4):383-389.

in this population are necessary to explore the link 18. Kleiber C, Hanrahan K, Fagan C, Zittergruen MA. Heparin versus

saline for peripheral IV locks in children. Pediatr Nurs.

between phlebitis and CR-BSI in the future.

1993;19(4):405-409.

ACKNOWLEDGMENT 19. Danek GD, Norris EM. Pediatric IV catheters: efficacy of saline

flush. Pediatr Nurs. 1992;18(2):111-113.

The authors thank Tracy Bladen, Clinical Nurse, Par- 20. Lundgren A, Wahren LK, Ek AC. Peripheral intravenous lines: time

enteral Therapy, Gold Coast Hospital, Queensland, in situ related to complications. J Intraven Nurs. 1996;19(5):229-

Australia for her contribution to this article. 238.

21. Lai KK. Safety of prolonging peripheral cannula and IV tubing use

from 72 hours to 96 hours. Am J Infect Control. 1998;26(1):66-70.

R E F E R E N C E S

22. McLane C, Morris L, Holm K. A comparison of intravascular pres-

1. Infusion Nurses Society. Infusion nursing standards of practice. J sure monitoring system contamination and patient bacteraemia

Intraven Nurs. 2000;23(6S). with use of 48- and 72-hour system change intervals. Heart Lung.

2. Garland JS, Dunne WM, Havens P, et al. Peripheral intravenous 1998;27(3):200-208.

catheter complications in critically ill children: a prospective study. 23. Meier PA, Fredrickson M, Catney M, Nettleton MD. Impact of a

Paediatrics. 1992;89(6):1145-1150. dedicated intravenous therapy team on nosocomial bloodstream

3. Schlager TA, Hidde M, Rodger P, Germanson TP, Donowitz LG. infection rates. Am J Infect Control. 1998;26(4):388-392.

Intravascular catheter colonisation in critically ill children. Infect 24. Soifer NE, Borzak S, Edlin BR, Weinstein RA. Prevention of periph-

Control Hosp Epidemiol. 1997;18:347-348. eral venous catheter complications with an intravenous therapy

4. Fox M, Molesky M, van Aerde JE, Muttitt S. Changing parenteral team. Arch Intern Med. 1998;158(5):473-477.

nutrition administration sets every 24 hours versus every 48 hours 25. Larsen EL, Buta AM, Gullette DL, Laughon BA. Alcohol for surgi-

in newborn infants. Can J Gastroenterol. 1999;13(2):147-151. cal scrubbing? Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol. 1990;11:139-143.

5. Sheehan AM, Palange K, Rasor JS, Moran MA. Significantly 26. Livesley J, Richardson S. Securing methods for peripheral cannulae.

improved intravenous catheter performance in neonates: insertion Nurs Standard. 1993;7(31):31-34.

ease, dwell time, complication rate, and costs. J Perinatol. 27. Callaghan S. A Comparative Study of Peripheral Intravenous

1992;12(4):369-376. Device Securement in the Paediatric Population. Poster presentation

6. Stanley MD, Meister E, Fuschuber K. Infiltration during intra- INS annual meeting; April 30-May 3, 2001; Indianapolis, Ind.

venous therapy in neonates: comparison of Teflon and vialon 28. Intravenous Nurses Society. Infusion Nursing Standards for Prac-

catheters. South Med J. 1992;85(9):883-886. tice. J Intraven Nurs. 2000;23:6S.

7. Civetta J, Hudson-Civetta J, Ball S. Decreasing catheter-related 29. Wheeler C, Frey AM. Intravenous therapy in children. In: Terry J,

infection and hospital costs by continuous quality improvement. Baranowski L, Lonsway RA, Hedrick C, eds. Intravenous Therapy:

Crit Care Med. 1996;24:1660-1665. Clinical Principles and Practice. Philadelphia: WB Saunders;

8. Collignon P. Intravascular catheter-associated sepsis: a common 1995:467-504.

problem. Med J Aust. 1994;161:374-378. 30. Tager IB, Ginsberg MB, Ellis SE, et al. An epidemiological study of

9. Maki DG. Infections caused by intravascular devices used for infu- the risks associated with peripheral intravenous catheters. Am J Epi-

sion therapy: pathogenesis, prevention, and management. In: Bisno demiol. 1983;118(6):839-851.

A, Waldvogel F, eds. Infections Associated With Indwelling Medical 31. Shimandle RB, Johnson D, Baker M, Stotland N, Karrison T,

Devices. 2nd ed. Washington, DC: ASM Press; 1994:155-205. Arnow PM. Safety of peripheral intravenous catheters in children.

10. Lund C, Kuller J, Lane A, Lott JW, Raines DA. Neonatal skin care: Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol. 1999;20:736-740.

the scientific basis for practice. JOGNN. 1999;28(3):241-254. 32. Mermel LA. Prevention of intravascular catheter-related infections.

11. Pearson ML. Hospital infection control practices advisory commit- Ann Intern Med. 2000;132(5):391-402.

tee. Guideline for the prevention of intravascular device related 33. Salzman MB, Isenberg HD, Shapiro JF, Lipsitz PJ, Rubin LG. A

infections. Am J Infect Control. 1996;24:262-293. prospective study of catheter hub as the portal of entry for microor-

12. Wood D. A comparative study of two securement techniques for ganisms causing catheter-related sepsis in neonates. J Infect Dis.

short peripheral intravenous catheters. J Intraven Nurs. 1997;20(6): 1993;167:487-490.

280-285. 34. Linares J, Stiges-Serra A, Garau J, Perez JL, Martin R. Pathogenesis

13. Langeweg JA, Vaessen HH, Ionescu TI. Complications in the use of of catheter sepsis: a prospective study with quantitative and semi-

intravenous catheters for major surgery: a clinical study. J Anaesth. quantitative cultures of catheter hub and segments. J Clin Micro-

1996;10(4):239-243. biol. 1985;21:357-325.

14. McKee JM, Shell JA, Warren TA, Campbell VP. Complications of 35. Danzig LE, Short, LJ, Collins K, et al. Bloodstream infections

intravenous therapy: a randomised prospective study: vialon vs. associated with a needleless intravenous infusion system in

teflon. J Intraven Nurs. 1997;12(5):288-295. patient’s receiving home infusion therapy. JAMA. 1995;273(23):

15. Bregnezer T, Cohen D, Sackman P, Widmer A. Is routine replace- 1862-1864.

ment of peripheral intravenous catheters necessary? Arch Intern 36. Chodoff A, Pettis AM, Schoonmaker D, Shelly MA. Polymicrobial

Med. 1998;158:151-156. gram-negative bacteremia associated with saline solution flush used

16. Mermel LA. Prevention of intravascular catheter-related infections. with a needleless intravenous system. Am J Infect Control.

Infect Dis Clin Pract. 1994;3:391-398. 1995;23:357-363.

17. Gyr P, Smith K, Pontious S, Burroughs T, Mahl C, Swerczek L. Dou- 37. Tomford JW, Hershey CO, McLaren CE, Porter DK, Cohen DI.

ble-blind comparisons of heparin and saline flush solutions in main- Intravenous therapy team and peripheral venous catheter-associated

166 Journal of Infusion Nursing

complications: a prospective controlled study. Arch Intern Med. 40. Perucca R, Hedrick C, Terry C, Johnson J. Infection control. In:

1984;144(6):1191-1194. Terry J, Baranowski L, Lonsway RA, Hedrick C, eds. Intravenous

38. Frey AM. Success rate for peripheral IV insertion in a children’s hos- Therapy: Clinical Principles and Practice. Philadelphia: WB Saun-

pital. J Intraven Nurs. 1998;21(3):160-165. ders; 1995:140-150.

39. Perdue M. Intravenous complications. In: Terry J, Baranowski L, 41. Needham R. Growth and development. In: Behrman RE, Kliegman

Lonsway RA, Hedrick C, eds. Intravenous Therapy: Clinical Prin- RM, Arvin AM, eds. Nelson Textbook of Pediatrics. 15th ed.

ciples and Practice. Philadelphia: WB Saunders; 1995:419-446. Philadelphia: WB Saunders; 1996:49.

Vol. 25, No. 3, May/June 2002 167

You might also like

- Jaeger Et Al 2017Document6 pagesJaeger Et Al 2017rachid hattabNo ratings yet

- Effect of Reusing Suction Catheters On The Occurrence of Pneumonia in ChildrenDocument9 pagesEffect of Reusing Suction Catheters On The Occurrence of Pneumonia in ChildrenSitti Rosdiana YahyaNo ratings yet

- Peripheral Intravenous Cannulation and Phlebitis RiskDocument9 pagesPeripheral Intravenous Cannulation and Phlebitis RiskSantosh YadavNo ratings yet

- Ventilator-Associated Pneumonia in Low Birth Weight Neonates at A Neonatal Intensive Care Unit: A Retrospective Observational StudyDocument6 pagesVentilator-Associated Pneumonia in Low Birth Weight Neonates at A Neonatal Intensive Care Unit: A Retrospective Observational StudyLuize KrulciferNo ratings yet

- JPediatrNeurosci132176-312375 084037Document6 pagesJPediatrNeurosci132176-312375 084037afriska chandraNo ratings yet

- Positive Effect of Care Bundles On Patients With Central Venous Catheter Insertions at A Tertiary Hospital in Beijing, ChinaDocument10 pagesPositive Effect of Care Bundles On Patients With Central Venous Catheter Insertions at A Tertiary Hospital in Beijing, ChinaElfina NataliaNo ratings yet

- Pal Ese 2011Document8 pagesPal Ese 2011retta tataNo ratings yet

- The Pediatric Sedation Unit: A Mechanism For Pediatric SedationDocument9 pagesThe Pediatric Sedation Unit: A Mechanism For Pediatric SedationSantosa TandiNo ratings yet

- Turning Frequency in Adult Bedridden Patients To Prevent Hospital-Acquired Pressure Ulcer: A Scoping ReviewDocument12 pagesTurning Frequency in Adult Bedridden Patients To Prevent Hospital-Acquired Pressure Ulcer: A Scoping ReviewfajaqaNo ratings yet

- Principles of A Paediatric Palliative Care Consultation Can Be Achieved With Home TelemedicineDocument5 pagesPrinciples of A Paediatric Palliative Care Consultation Can Be Achieved With Home TelemedicineAditha Fitrina AndianiNo ratings yet

- Group 7 PART 1 MSN 201 Coursework 3T2019 PDFDocument13 pagesGroup 7 PART 1 MSN 201 Coursework 3T2019 PDFGracie Sugatan PlacinoNo ratings yet

- 1 s2.0 S2452247318300384 Main PDFDocument4 pages1 s2.0 S2452247318300384 Main PDFDinny ApriliaNo ratings yet

- Ijnrd 8 125Document13 pagesIjnrd 8 125Muhammad Halil GibranNo ratings yet

- Side-to-Side Refluxing Nondismembered Ureterocystotomy A Novel Strategy To Address Obstructed Megaureters in Children. 2017. ESTUDIO CLINICODocument9 pagesSide-to-Side Refluxing Nondismembered Ureterocystotomy A Novel Strategy To Address Obstructed Megaureters in Children. 2017. ESTUDIO CLINICOPaz MoncayoNo ratings yet

- Factors for Successful Nonsurgical Treatment of Pediatric Peritonsillar AbscessDocument4 pagesFactors for Successful Nonsurgical Treatment of Pediatric Peritonsillar AbscessruthameliapNo ratings yet

- Study of Clinical Profile of Late Preterms at Tertiary Care Hospital, BangaloreDocument11 pagesStudy of Clinical Profile of Late Preterms at Tertiary Care Hospital, BangaloreInternational Journal of Innovative Science and Research TechnologyNo ratings yet

- Journal Yolanda 2 - Trends in The Management of Peritonsillar Abscess in Children A Nationwide Population-Based Study in TaiwanDocument6 pagesJournal Yolanda 2 - Trends in The Management of Peritonsillar Abscess in Children A Nationwide Population-Based Study in TaiwanfrediNo ratings yet

- Jurnal Uro 2Document8 pagesJurnal Uro 2Lisa HikmawanNo ratings yet

- Vesicoureteral Reflux: The RIVUR Study and The Way ForwardDocument3 pagesVesicoureteral Reflux: The RIVUR Study and The Way ForwardRohit GuptaNo ratings yet

- Diuretico en DBPDocument10 pagesDiuretico en DBPUriel MartzNo ratings yet

- APA-109-236Document12 pagesAPA-109-236yuwengunawan7No ratings yet

- Original Research: Neonatal Peripherally Inserted Central Catheter Practices and ProvidersDocument13 pagesOriginal Research: Neonatal Peripherally Inserted Central Catheter Practices and ProvidersWinarti RimadhaniNo ratings yet

- Non InvasiveventilationDocument10 pagesNon InvasiveventilationpiusputraNo ratings yet

- .A Retrosp Stu On The Long-Term Placem of Peripher Inse Central...Document6 pages.A Retrosp Stu On The Long-Term Placem of Peripher Inse Central...Ane MartinezNo ratings yet

- Oral Care Interventions and Oropharyngeal Colonization in Children Receiving Mechanical VentilationDocument12 pagesOral Care Interventions and Oropharyngeal Colonization in Children Receiving Mechanical VentilationAdila amalitaNo ratings yet

- The Incidence of Peripheral IntravenousDocument5 pagesThe Incidence of Peripheral IntravenousAlvin Josh CalingayanNo ratings yet

- 1980 220X Reeusp 52 E03360Document5 pages1980 220X Reeusp 52 E03360Miguel Angel Tipiani MallmaNo ratings yet

- Single-Site Laparoscopic Percutaneous Extraperitoneal Closure of The Internal Ring Using An Epidural Needle For Children With Inguinal HerniaDocument5 pagesSingle-Site Laparoscopic Percutaneous Extraperitoneal Closure of The Internal Ring Using An Epidural Needle For Children With Inguinal HerniaFarizka Dwinda HNo ratings yet

- Jurnal IV CatheterDocument9 pagesJurnal IV Cathetereneng latipa dewiNo ratings yet

- Appropriateness of Use of An AntimicrobialDocument3 pagesAppropriateness of Use of An AntimicrobialKurt Maverick De LeonNo ratings yet

- 10.7556 Jaoa.2011.111.1.44Document5 pages10.7556 Jaoa.2011.111.1.44DianaNo ratings yet

- Medi 96 E5864Document6 pagesMedi 96 E5864mono1144No ratings yet

- Effect of Fasting Time Before Anesthesia On Complicated Post OperativDocument6 pagesEffect of Fasting Time Before Anesthesia On Complicated Post OperativsantiNo ratings yet

- Development of A Clinical Practice Guideline For Testing Nasogastric Tube PlacementDocument9 pagesDevelopment of A Clinical Practice Guideline For Testing Nasogastric Tube PlacementSean EurekaNo ratings yet

- Seven Ebp HabbitsDocument155 pagesSeven Ebp HabbitskincokoNo ratings yet

- Al-Natour - 2016 - Peritoneal DialysisDocument3 pagesAl-Natour - 2016 - Peritoneal Dialysisridha afzalNo ratings yet

- Investigation On The Status of Oral Intake Management Measures During Labor in ChinaDocument5 pagesInvestigation On The Status of Oral Intake Management Measures During Labor in Chinacesar aNo ratings yet

- HSR2 5 E649Document9 pagesHSR2 5 E649Samsul BahriNo ratings yet

- Australian Critical CareDocument9 pagesAustralian Critical CareLisa MaghfirahNo ratings yet

- Yeh 2019Document5 pagesYeh 2019sigitdwimulyoNo ratings yet

- SepsisDocument9 pagesSepsisArief FidiantoNo ratings yet

- Development of A Nursing Care Protocol For Care of Neonates With Esophageal Atresia/ Tracheo - Esophageal FistulaDocument14 pagesDevelopment of A Nursing Care Protocol For Care of Neonates With Esophageal Atresia/ Tracheo - Esophageal FistulaSanket TelangNo ratings yet

- Pediatric Anesthesia - 2022 - Weatherall - Developing An Extubation Strategy For The Difficult Pediatric Airway Who WhenDocument8 pagesPediatric Anesthesia - 2022 - Weatherall - Developing An Extubation Strategy For The Difficult Pediatric Airway Who WhenPamela Mamani FloresNo ratings yet

- A Clinical Study of Intussusception in ChildrenDocument18 pagesA Clinical Study of Intussusception in ChildrenIJAR JOURNALNo ratings yet

- Paediatric Mechanical Ventilation in The Intensive Care UnitDocument5 pagesPaediatric Mechanical Ventilation in The Intensive Care UnitAndres RiveraNo ratings yet

- CholeraDocument7 pagesCholeraDewa Ayu Pradnya DewiNo ratings yet

- Ear Wax Removal: Help Patients Help ThemselvesDocument25 pagesEar Wax Removal: Help Patients Help ThemselvesYelvira DevitaNo ratings yet

- Jacinto DKK 2014Document7 pagesJacinto DKK 2014dahlia habibahNo ratings yet

- Artigo 2 CinhalDocument7 pagesArtigo 2 CinhalSara PereiraNo ratings yet

- Post Operative FastingDocument7 pagesPost Operative FastingUsama SaeedNo ratings yet

- The Role of Delayed Cord Clamping in Improving The Outcome in Preterm BabiesDocument5 pagesThe Role of Delayed Cord Clamping in Improving The Outcome in Preterm BabiesJehangir AllamNo ratings yet

- Ventilator-Associated Pneumonia in Low Birth Weight Neonates at A Neonatal Intensive Care Unit A Retrospective ObserDocument6 pagesVentilator-Associated Pneumonia in Low Birth Weight Neonates at A Neonatal Intensive Care Unit A Retrospective ObserDevi Arnes SimanjuntakNo ratings yet

- Pediatric Nasogastric Tube Placement and Verification: Best Practice Recommendations From The NOVEL Project: CONSENSUS RecommendationsDocument9 pagesPediatric Nasogastric Tube Placement and Verification: Best Practice Recommendations From The NOVEL Project: CONSENSUS RecommendationsDoraNo ratings yet

- Use of Short Peripheral Intravenous Catheters: Characteristics, Management, and Outcomes WorldwideDocument7 pagesUse of Short Peripheral Intravenous Catheters: Characteristics, Management, and Outcomes WorldwidemochkurniawanNo ratings yet

- American Journal of Infection Control: Major ArticleDocument5 pagesAmerican Journal of Infection Control: Major ArticleSianiiChavezMoránNo ratings yet

- Prehospital Antibiotic Prophylaxis For Open Fractures: Practicality and SafetyDocument11 pagesPrehospital Antibiotic Prophylaxis For Open Fractures: Practicality and SafetyMarco Culqui SánchezNo ratings yet

- Australian GuidelinesDocument12 pagesAustralian GuidelinesMaria Agostina EspecheNo ratings yet

- Consensus Paper For Oral CareDocument10 pagesConsensus Paper For Oral CareDaniela AccorgiNo ratings yet

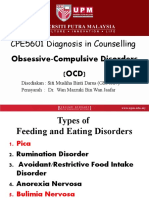

- CPE5601 Diagnosis and Treatment of Feeding and Eating DisordersDocument16 pagesCPE5601 Diagnosis and Treatment of Feeding and Eating DisordersSiti MuslihaNo ratings yet

- SS 6e Manager Sample-ChapterDocument32 pagesSS 6e Manager Sample-ChapterIrmita Prameswari Wijayanti100% (2)

- Food AdministrationDocument23 pagesFood AdministrationRareNo ratings yet

- Gordon'S Functional Health PatternDocument10 pagesGordon'S Functional Health PatternDave SapladNo ratings yet

- Dahlar Release Bag 500 - MSDSDocument7 pagesDahlar Release Bag 500 - MSDSApol Aguisanda JrNo ratings yet

- 10.1007@s11065 020 09443 7Document14 pages10.1007@s11065 020 09443 7José NettoNo ratings yet

- Module 7 Mental Health and Well-Being in Middle and Late AdolescenceDocument22 pagesModule 7 Mental Health and Well-Being in Middle and Late AdolescenceFaith CubillaNo ratings yet

- PHS 210 EpidemiologyDocument4 pagesPHS 210 EpidemiologySera GoldNo ratings yet

- Health 10 - Q2 - WK5Document2 pagesHealth 10 - Q2 - WK5graceNo ratings yet

- Ncp. Pedia.Document2 pagesNcp. Pedia.Czarina MayoNo ratings yet

- CV and Educational Background of Tomas M. MadayagDocument12 pagesCV and Educational Background of Tomas M. MadayagJovel TomNo ratings yet

- The Association Between Income and Life Expectancy in The United States 2001 To 2014Document17 pagesThe Association Between Income and Life Expectancy in The United States 2001 To 2014Noemi HidalgoNo ratings yet

- Factorial Design Fiction ManuscriptDocument5 pagesFactorial Design Fiction Manuscriptdave_scribedNo ratings yet

- Clinical Pharmacy Thesis TopicsDocument6 pagesClinical Pharmacy Thesis Topicsbsk561ek100% (2)

- The Durex Story Stretching The MarketDocument4 pagesThe Durex Story Stretching The MarketShwetaGoudNo ratings yet

- PUDV3134Document1 pagePUDV3134rakesh adamalaNo ratings yet

- History of CounsellingDocument7 pagesHistory of Counsellingsam sangeethNo ratings yet

- Padlan Getigan and PartnersDocument4 pagesPadlan Getigan and PartnersMichaelandKaye DanaoNo ratings yet

- Roger A. Mackinnon, Robert Michels, Peter J. Buckley-The Psychiatric Interview in Clinical Practice (2015)Document724 pagesRoger A. Mackinnon, Robert Michels, Peter J. Buckley-The Psychiatric Interview in Clinical Practice (2015)Selma Churukova92% (12)

- Margolin GR 11 NegDocument22 pagesMargolin GR 11 NegbhupatinNo ratings yet

- Working Environmental HazardsDocument5 pagesWorking Environmental HazardsSri100% (1)

- Tips For Triage NursesDocument4 pagesTips For Triage NursesCamille05No ratings yet

- Hormonal TherapiesDocument39 pagesHormonal TherapiesJalal EltabibNo ratings yet

- JHA For Tiling WorkDocument1 pageJHA For Tiling WorkMuhammad Suffyanazwan80% (5)

- Bwcs Feedback Final September 2023Document56 pagesBwcs Feedback Final September 2023Babloo50% (2)

- Scalp Acupuncture BasicsDocument27 pagesScalp Acupuncture BasicsGanga SinghNo ratings yet

- Using Technology To Study Cellular and Molecular BiologyDocument138 pagesUsing Technology To Study Cellular and Molecular BiologybheeshmatNo ratings yet

- IQVIA CH - November 14th 2023Document75 pagesIQVIA CH - November 14th 2023alina.rxa.tdrNo ratings yet

- Dysfunctional Uterine Bleeding History CollectionDocument4 pagesDysfunctional Uterine Bleeding History CollectionAnitha BalakrishnanNo ratings yet

- Regenics Pitch DeckDocument32 pagesRegenics Pitch DeckGrayson MillerNo ratings yet