Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Downbeat Nystagmus: Aetiology and Comorbidity in 117 Patients

Uploaded by

Vinay GOriginal Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Downbeat Nystagmus: Aetiology and Comorbidity in 117 Patients

Uploaded by

Vinay GCopyright:

Available Formats

Downloaded from jnnp.bmj.com on April 25, 2013 - Published by group.bmj.

com

Research paper

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE

provided by Open Access LMU

Downbeat nystagmus: aetiology and comorbidity in

117 patients

J N Wagner, M Glaser, T Brandt, M Strupp

Department of Neurology, ABSTRACT brainstem pathology.2 In a large proportion of

Ludwig-Maximilians University, Objectives: Downbeat nystagmus (DBN) is the most patients, however, no anatomical lesion can be

Klinikum Grosshadern, Munich,

common form of acquired involuntary ocular oscillation identified (so-called idiopathic DBN).3 The patho-

Germany

overriding fixation. According to previous studies, the physiology underlying DBN is still controversial.

Correspondence to: cause of DBN is unsolved in up to 44% of cases. We An inherent asymmetry of peripheral vestibular

Dr J N Wagner, Department of reviewed 117 patients to establish whether analysis of a input has been proposed as well as central

Neurology, Ludwig-Maximilians imbalance in the vertical vestibulo-ocular sys-

University, Klinikum large collective and improved diagnostic means would

Grosshadern, Marchioninistraße reduce the number of cases with ‘‘idiopathic DBN’’ and tem.4–6 Others suggest an imbalance of the smooth

15, D-81366 Munich, Germany; thus change the aetiological spectrum. pursuit system or a mismatch of the coordinate

judith.wagner@ systems of the saccadic burst generator and the

med.uni-muenchen.de Methods: The medical records of all patients diagnosed

with DBN in our Neurological Dizziness Unit between neural eye-velocity-to-position integrator.7–9

1992 and 2006 were reviewed. In the final analysis, only The aetiology of DBN is diverse. Craniocervical

Received 8 June 2007

Revised 23 August 2007 those with documented cranial MRI were included. Their malformations, cerebellar degeneration, vascular

Accepted 29 August 2007 workup comprised a detailed history, standardised pathology, inflammatory disease and intoxication

Published Online First neurological, neuro-otological and neuro-ophthalmological with lithium or antiepileptic drugs have, among

14 September 2007 others, been implicated.3 5 10–12 In one of the first

examination, and further laboratory tests.

Results: In 62% (n = 72) of patients the aetiology was descriptions of this condition, DBN due to

identified (‘‘secondary DBN’’), the most frequent causes cerebellar ectopia (Arnold–Chiari-malformation

being cerebellar degeneration (n = 23) and cerebellar (ACM)) was reported.13 In the first survey on

ischaemia (n = 10). In 38% (n = 45), no cause was found DBN, craniocervical malformations were diagnosed

(‘‘idiopathic DBN’’). A major finding was the high in eight of 27 patients and thus topped the list of

comorbidity of both idiopathic and secondary DBN with underlying aetiologies.14 In one of the most

bilateral vestibulopathy (36%) and the association with comprehensive surveys of this condition to date,

polyneuropathy and cerebellar ataxia even without these disorders remained one of the most frequent

cerebellar pathology on MRI. single identified causes of DBN (ACM in 17 of 62

Conclusions: Idiopathic DBN remains common despite patients).3 In this study, no cause for DBN could be

improved diagnostic techniques. Our findings allow the determined in 27 of 62 patients. These retro-

classification of ‘‘idiopathic DBN’’ into three subgroups: spective studies, however, were performed before

‘‘pure’’ DBN (n = 17); ‘‘cerebellar’’ DBN (ie, DBN plus the general availability of MRI. Thus lacunar

further cerebellar signs in the absence of cerebellar infarctions, demyelinating plaques and other subtle

pathology on MRI; n = 6); and a ‘‘syndromatic’’ form of lesions of the posterior fossa may not have been

DBN associated with at least two of the following: detected. In a small study of 24 patients with DBN

examined by MRI, ACM and cerebellar degenera-

bilateral vestibulopathy, cerebellar signs and peripheral

tion remained the commonest causes of DBN.15

neuropathy (n = 16). The latter may be caused by

multisystem neurodegeneration. To determine if this aetiological spectrum still

holds true in an analysis of a large collective with

thorough imaging or whether the predominance of

Downbeat nystagmus (DBN) is the most common craniocervical malformations can be overturned

form of acquired involuntary ocular oscillations and the number of cryptogenic DBN reduced by

overriding fixation. It is characterised by slow improved diagnostic means, we retrospectively

upward drifts and fast downward phases. Slow analysed the findings in 117 patients who had all

phase velocity increases on lateral and downward undergone cranial MR imaging and standardised

neurological, neuro-ophthalmological and neuro-

gaze and convergence, although there may be

otological examinations.

atypical presentations with enhancement of DBN

on upward gaze or suppression on convergence.1

The most common presenting symptoms are PATIENTS AND METHODS

unsteadiness of gait and to-and-fro vertigo. On To retrospectively determine the frequency of

further inquiry, patients frequently report blurred DBN among congenital and acquired ocular oscilla-

vision or oscillopsia that increases on lateral gaze. tions that override fixation, the files of 4854

DBN is often associated with other oculomotor consecutive patients from our dizziness unit were

disorders, predominantly smooth pursuit deficits analysed.

and impairment of the optokinetic reflex and The medical records of 136 patients diagnosed as

visual fixation suppression of the vestibulo-ocular having DBN in the Neurological Dizziness Unit of

reflex (VOR). the University of Munich over a 14 year period

DBN may be caused by lesions of the vestibul- between 1992 and 2006 were reviewed. A detailed

ocerebellum and, rarely, bilateral paramedian standardised history was taken for all patients. The

672 J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry 2008;79:672–677. doi:10.1136/jnnp.2007.126284

Downloaded from jnnp.bmj.com on April 25, 2013 - Published by group.bmj.com

Research paper

following parameters, all of them relevant to inclusion / Statistics

exclusion of differential diagnoses of vertigo and dizziness, Data were collected and evaluated by means of Excel (Microsoft

were assessed. Corp.) spreadsheet software. Comparison between categorical

1. Vertigo/dizziness/unsteadiness of gait: onset, duration, values was performed using a x2 test. Metric values were

time course, frequency, associated visual and ocular motor compared by a Mann–Whitney U test. Significance was defined

symptoms (including oscillopsia, double vision, blurred as an alpha level of 0.05.

vision or loss of sight), associated otological symptoms

(including tinnitus, hearing loss, fullness of the ear),

associated cerebellar symptoms (ataxia, dysarthria) and RESULTS

other concurrent symptoms, such as headache, phonopho- Of a total of 5904 patients in our department between 1992 and

bia, photophobia, nausea and vomiting 2006, 136 had been diagnosed as having DBN. DBN was found

2. Past medical history, with particular reference to migraine, to be the most common form of involuntary fixation

polyneuropathy (PNP), exposure to toxins, ethanol, nystagmus of central origin (table 1). Only those patients

lithium, amiodarone or antiepileptic medication, cardiovas- who had cranial MRI (n = 117) were included in the final

cular risk factors (eg, arterial hypertension, diabetes analysis. They were evaluated for aetiology, epidemiology,

mellitus) and systematic inquiry of other neurological, presentation and associated findings.

ophthalmological, ENT and medical diseases

3. Family history Aetiology

Patients underwent a full and standardised neurological, In 62% (72 of 117) of patients with DBN, a possible (n = 46) or

neuro-otological and neuro-ophthalmological examination with definite (n = 26) causative factor was identified. The most

special emphasis on spontaneous nystagmus with Frenzel’s frequent single identifiable cause of DBN in our patients was

goggles in the primary position, lateral and vertical gaze cerebellar degenerative disease (20%, n = 23). This group

direction, gaze evoked nystagmus, smooth pursuit, saccades, included multisystem atrophy (according to the diagnostic

optokinetic nystagmus, visual fixation suppression of the VOR, criteria of the International Consensus Conference), spinocere-

rebound nystagmus, head shaking nystagmus, head thrust test, bellar ataxia (ataxia with suspected autosomal dominant

eye position in roll with a scanning laser ophthalmoscope and inheritance) and sporadic adult onset ataxia (progressive ataxia

determination of the subjective visual vertical. without established symptomatic cause).16 17 In one patient, the

diagnosis (spinocerebellar ataxia 6) was confirmed by genetic

testing.

Electronystagmography

Degenerative cerebellar disease as a cause for DBN was

Electronystagmography with bithermal caloric testing (30uC

followed in frequency by posterior fossa vascular lesions (9%,

and 44uC) was performed in 71 patients. The mean peak slow

n = 10), and craniocervical malformations with cerebellar

phase velocity (SPV) was determined with Igor Pro Wave Metric

ectopia (7%, n = 8) (fig 1; for a list of individual entities

(V.3.13) software. Vestibulopathy was defined as nystagmus

included in the diagnostic groups listed above see tables 2 and

with an SPV ,5u/s per irrigation.

3).

In 38% (n = 45) of all patients with DBN, no causative factor

Other laboratory tests was identified. In these cases DBN was therefore considered

Specific laboratory tests included cranial MRI (n = 117), idiopathic. As ‘‘idiopathic DBN’’ might represent a distinct

auditory evoked potentials and/or an audiogram (n = 27), nosological entity of unknown aetiology, it will henceforth be

vitamin B12 (n = 50), folate (n = 48), vitamin E (n = 24), considered separately, especially in terms of its association with

glutamic acid decarboxylase antibodies (n = 8), magnesium other neurological symptoms.

(n = 20) and CSF chemistry (n = 62).

PNP was diagnosed in those patients with electromyographic Age and gender

signs of axonal and/or demyelinating PNP and in those with a Median age of all DBN patients was 62 years (range 10–92). In

significantly reduced sense of vibration (4/8 or less in the tuning those with idiopathic DBN, median age was 67 years with a

fork test). peak between the seventh and eighth decade (range 24–92).

Patients with secondary DBN had a mean age of 59 years, with

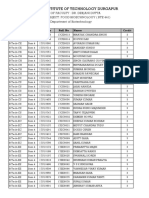

Table 1 Frequency of congenital and/or acquired ocular oscillations in the peak onset in the seventh decade (range 10–82 years) (fig 2).

a total of 4854 consecutive patients seen between 1995 and 2006 in our Thus patients with idiopathic DBN were older than those with

neurological dizziness unit secondary DBN (p,0.001). Whereas the male-to-female ratio

Type of nystagmus/ocular oscillation n was roughly equal in idiopathic DBN, there was a slight female

preponderance in secondary DBN (total male to female: 55% vs

Downbeat nystagmus 101 45%; idiopathic: 51% vs. 49%; secondary: 41% vs 59%).

Upbeat nystagmus 54

Central positional nystagmus 26

Pendular nystagmus 15 Characteristic features of DBN

Congenital nystagmus 12 A typical feature of DBN is enhancement of the SPV on lateral

Torsional nystagmus 12 gaze. Some patients, however, lack enhancement or even

See-saw nystagmus 8 exhibit a reduction in SPV. In our series, SPV increased on

Ocular flutter 8 lateral gaze in 77% (n = 90) of patients and there was no SPV

Square wave jerks 7 enhancement in 18% (n = 21) of patients (n = 41 vs n = 4 in

Opsoclonus 1 idiopathic DBN and n = 49 vs n = 17 in secondary DBN). In six

Periodic alternating nystagmus 1 patients, modulation of DBN on lateral gaze had been

Downbeat nystagmus was the most frequent fixation nystagmus. insufficiently documented. Idiopathic DBN was more often

J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry 2008;79:672–677. doi:10.1136/jnnp.2007.126284 673

Downloaded from jnnp.bmj.com on April 25, 2013 - Published by group.bmj.com

Research paper

Figure 1 Aetiology of downbeat

nystagmus (DBN). Relative frequencies of

idiopathic and secondary DBN are shown.

Causes of secondary DBN are specified

(percentages refer to frequency relative to

all DBN cases). GAD, glutamic acid

decarboxylase.

associated with enhancement of the nystagmus on lateral gaze SPV decreased when the patient was supine and increased when

than secondary DBN (p,0.05). he was prone. In one patient with idiopathic DBN, SPV

In 64% (n = 29) of patients with idiopathic and 82% (n = 59) increased in both the supine and prone positions while in

of those with secondary DBN, SPV increased on downward and another it decreased in both positions.

decreased on upward gaze. In 6% (n = 3) of patients with

idiopathic and none of those with secondary DBN, SPV

Presenting symptoms and clinical signs

increased on upward gaze. Convergence enhanced SPV in 64%

The most common presenting symptom was unsteadiness of

(n = 29) of patients with idiopathic and 61% (n = 44) of

gait or to-and-fro vertigo (idiopathic 89%; secondary 81%).

patients with secondary DBN. Dependency of SPV on vertical

Most patients with idiopathic or secondary DBN reported

gaze position and convergence was not statistically different

permanent rather than episodic symptoms (93% vs 94%).

between idiopathic and secondary DBN.

Oscillopsia was reported by 44% with idiopathic compared

In nine patients (six with idiopathic, three with secondary

with 38% with secondary DBN.

DBN), dependency of the SPV on head position was tested. In

seven (four idiopathic DBN, three secondary DBN) patients,

Associated neurological findings

Table 2 Details of aetiological entities underlying secondary downbeat Peripheral vestibular deficits

nystagmus A frequent finding in patients with DBN was unilateral or

Aetiology n bilateral vestibulopathy. Vestibulopathy was defined as a

reduced response to caloric irrigation and/or a pathological

Degenerative 23

head thrust test. Forty-five patients had undergone either

Spinocerebellar ataxia 13

caloric irrigation or head thrust tests, 36 had undergone both

Sporadic adult onset ataxia 9

and in 36 patients (28 with secondary, eight with idiopathic

Multisystem atrophy (cerebellar type) 1

Posterior fossa vascular lesions 10

DBN) peripheral vestibular function was not tested. Of those

Craniocervical malformation 8

tested, 32% of patients with idiopathic DBN and 39% with

Arnold–Chiari malformation type I 7

Arnold–Chiari malformation type II 1 Table 3 Localisation of lesions in patients with downbeat nystagmus

Toxic 5 secondary to vascular pathology

Chronic ethanol abuse with cerebellar atrophy 1 Patient

Chronic ethanol abuse without cerebellar atrophy 1 No Localisation

Anticonvulsants (phenytoin, carbamazepine) 2

1 Thrombosis of the basilar artery; ischaemic infarction of the left caudate, left

Amiodarone 1

paramedian mesencephalon, small ischaemic lesions in both cerebellar

Inflammatory/infectious 4 hemispheres

Pancerebellar syndrome post-tick borne encephalitis 1 2 Sudden onset of symptoms, diffuse microangiopathic changes

Cerebellitis of unclear aetiology 1 3 Venous angioma paramedially pontomesencephal; two small ischaemic

Chronic aseptic meningitis 1 lesions in both cerebellar hemispheres

Pontine encephalitis 1 4 Infarction of the left superior cerebellar artery

Neoplastic 4 5 Dissection of both vertebral arteries; infarctions of both cerebellar

Pontomedullary astrocytoma 1 hemispheres

Cerebellar meningeoma 1 6 Infarction of the left anterior and posterior inferior cerebellar artery with

involvement of the left tonsilla, cerebellar peduncle and the pontine

Ependymoma; hydrocephalus 1

tegmentum

Plexus papilloma 4th ventricle 1

7 Infarction of both cerebellar hemispheres and in the area of the right posterior

Episodic ataxia type 2 4 cerebral artery

Paraneoplastic 3 8 Stenosis of the left vertebral artery; defect of the left cerebellar tonsilla.

Paraneoplastic (anti-yo/anti-Purkinje-Cell positive) 2 9 Pontomesencephalic arteriovenous malformation

Paraneoplastic (anti-yo/anti-Purkinje-Cell negative) 1 10 Brainstem haemorrhage on the basis of a pontomesencephalic venous

Other 11 malformation

674 J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry 2008;79:672–677. doi:10.1136/jnnp.2007.126284

Downloaded from jnnp.bmj.com on April 25, 2013 - Published by group.bmj.com

Research paper

Figure 2 Age distribution of patients with downbeat nystagmus (DBN),

presented separately for idiopathic and secondary DBN.

secondary DBN had bilateral vestibular deficits. Of those who

had undergone both caloric irrigation and head thrust tests Figure 3 Overlap of idiopathic downbeat nystagmus with peripheral

(n = 36), 19 had bilateral vestibulopathy. In nine of these, both neuropathy, cerebellar signs and bilateral vestibulopathy. Absolute

numbers are given.

tests showed bilateral vestibular deficits. Eight had pathological

head thrust tests with normal caloric excitability and two

patients exhibited diminished peripheral vestibular caloric (idiopathic DBN 18%, secondary DBN 29%) and head shaking

response with bilateral (n = 1) or unilateral (n = 1) physiological nystagmus (idiopathic DBN 11%, secondary DBN 16%).

head thrust tests.

Ancillary findings

Polyneuropathy Cranial imaging

PNP was frequently associated with DBN (16 patients with A cranial MRI was obtained for all 117 patients. An experienced

idiopathic, 18 with secondary DBN). Patients with known neuroradiologist detected cerebellar atrophy in 27 patients and

aetiologies of PNP, such as diabetes mellitus (n = 9), were other cerebellar lesions in 13 patients. Brainstem lesions were

excluded from this group. The neuropathies diagnosed were present in 11 patients.

heterogeneous, including sensory, motor, demyelinating, axonal

and mixed types. Serum chemistry

Vitamin B12 serum levels were determined in 50 patients. Two

Cerebellar signs had markedly diminished levels (146 pg/ml, 95 pg/ml). B12 was

Cerebellar signs, including limb ataxia and dysarthria, were only slightly reduced in two others (211 pg/ml, 239 pg/ml;

frequently seen in the ‘‘secondary DBN’’ group (limb ataxia in normal range 250–900). Vitamin E levels were determined in 24

70% and dysarthria in 46%). They were also present in patients patients; all were within the normal range or elevated.

with idiopathic DBN (limb ataxia in 42% and dysarthria in Furthermore, magnesium levels were determined in 20 patients,

13%)—that is, those patients who did not have cerebellar all of which were normal.

lesions on MRI or evidence of cerebellar disease in other Glutamic acid decarboxylase antibody levels were determined

technical investigations. in eight patients. Markedly raised serum levels were detected in

Notably, there was considerable overlap between idiopathic a 56-year-old male with a history of chronic lymphocytic

DBN, cerebellar signs, bilateral vestibulopathy and peripheral leukaemia (80.2 U/ml; normal range ,0.9).

neuropathy (fig 3). Thirteen patients had DBN associated with

varying combinations of two of these disorders and, in three Spinal fluid

patients, with all three of them. A spinal tap was performed in 62 patients. Six patients had a

raised cell count (range 8–229 cells), nine patients raised CSF

Associated neuro-ophthalmological findings protein (range 50–150 mg/dl) and six patients had CSF specific

The most frequent ophthalmological findings associated with oligoclonal bands. The diagnoses in patients with pathological

DBN were saccadic vertical and horizontal smooth pursuit CSF included cerebellitis, pontine encephalitis and paraneoplas-

(idiopathic DBN 97% and secondary DBN 99%), impaired tic disease.

vertical optokinetic reflex (idiopathic DBN 85%, secondary DBN

87%) and impaired horizontal fixation suppression of the VOR Drugs

(idiopathic DBN 73%, secondary DBN 70%). Other pathologies Amiodarone toxicity was the cause of DBN in one patient,

included incomplete ocular tilt with deviation of the subjec- whose nystagmus disappeared after discontinuation of the drug.

tive visual vertical and/or ocular torsion (idiopathic DBN In two of nine patients on anticonvulsive medication at the

38%, secondary DBN 41%), dysmetric/slowed saccades (idio- time of diagnosis, drug toxicity was deemed responsible for the

pathic DBN 31%, secondary DBN 59%), rebound nystagmus DBN: a 73-year-old female with blood phenytoin levels of

J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry 2008;79:672–677. doi:10.1136/jnnp.2007.126284 675

Downloaded from jnnp.bmj.com on April 25, 2013 - Published by group.bmj.com

Research paper

30.3 mg/ml and a 58-year-old female on carbamazepine and Recent therapeutic advances with 4-aminopyridine, a potassium

vigabatrin. channel blocker, support this hypothesis. This agent may

enhance the inhibitory output of floccular Purkinje cells on

vestibular nuclei and thus alleviate DBN.25

DISCUSSION

On the basis of our findings that DBN frequently coexists

This retrospective study has shown that despite improved

with BVP, we suggest a potential pathophysiology of idiopathic

diagnostic means, especially the use of high resolution MRI, the

DBN. In our collective, DBN was predominantly associated

percentage of patients in whom no aetiology of DBN could be

with high frequency vestibular deficits. This is particularly

determined, so-called ‘‘idiopathic DBN’’, remains high (38%).

interesting in the light of recent findings on murine CACNA1A

This parallels values obtained in earlier studies performed before

mutants, in which calcium currents through P/Q channels are

the general availability of MRI and/or with smaller samples

reduced.26 27 These channels are particularly numerous in

(idiopathic DBN in 25–44% of patients).3 14 15 While our study

cerebellar Purkinje cells. The mutants ‘‘tottering’’ and ‘‘rocker’’

has reaffirmed the preponderance of cerebellar degeneration,

exhibit an upward elevation of average vertical eye position, a

posterior fossa vascular lesions and cerebellar ectopia among the

finding possibly analogous to DBN in humans. In these

causes of secondary DBN, it has also found new aspects

mutants, VOR gain is reduced only at high stimulus frequen-

connected with the comorbidity, classification and possible

cies. This parallel supports the view that a channelopathy

pathomechanisms of DBN.

might be the underlying cause in some cases of idiopathic

DBN, a hypothesis that is further backed by the finding that

Association of DBN with bilateral vestibulopathy, cerebellar 4-aminopyridine not only decreases DBN SPV but also improves

ataxia and polyneuropathy horizontal and vertical VOR gain.28

A major finding of this study was the association of idiopathic Another interesting feature of the murine mutants described

as well as secondary DBN with bilateral vestibulopathy (BVP), by Stahl and colleagues26 27 is that they exhibit no or little

as demonstrated by head thrust tests or caloric irrigation. The vertical eye displacement at birth. With advancing age,

prevalence of DBN and BVP is not known. In our neurological however, the ocular upward elevation increases. DBN, and

ocular motor and dizziness unit, BVP accounts for 4% and DBN particularly idiopathic DBN, in humans is a disorder of the

for 2.3% of the diagnoses. The common comorbidity of BVP and elderly (fig 2). Therefore, we suggest that a genetic polymorph-

DBN (32% in idiopathic and 39% in secondary DBN) suggests a ism of the CACNA1A gene predisposes to development of DBN,

common pathomechanism. This is supported by a recent study which becomes manifest if additional degenerative changes

on 255 patients with BVP, 17 (7%) of whom also had DBN.18 develop with ageing. Further genetic and molecular studies need

Apart from BVP, cerebellar ataxia and dysarthria were to be performed to prove these hypotheses.

identified as frequent concurrent symptoms. The association

of DBN with cerebellar symptoms is not surprising as DBN is

caused by a cerebellar, namely Purkinje cell, dysfunction. Forty- Clinical resume

two per cent of patients who fulfilled the criteria of so-called Neurologists should be familiar with DBN as it is the most

idiopathic DBN had cerebellar symptoms, although usually common form of involuntary central fixation nystagmus. They

subtle ones. In this group of patients, MRI detected no should always look for DBN in a patient complaining of gait

cerebellar atrophy or other cerebellar lesions. At this point, unsteadiness as this is the most common presentation.

however, we cannot exclude the fact that at least a subgroup of Particular attention should be paid to associated BVP, cerebellar

these patients presented at an early stage of a cerebellar symptoms and PNP. On the basis of our results, we suggest a

degenerative disease before overt cerebellar atrophy. Therefore, subgrouping of ‘‘idiopathic DBN’’: (1) patients with ‘‘pure’’

follow-up-studies are required. DBN who have no other signs or symptoms except for the

The third clinical entity frequently coexistent with DBN was oculomotor disorders commonly associated with floccular

PNP (36% in idiopathic and 25% in secondary DBN). These disorders (ie, impaired smooth pursuit, optokinetic reflex and

numbers may be biased by the advanced age of our sample. In a fixation suppression of the VOR); (2) a ‘‘cerebellar’’ form (ie,

community based survey, PNP had a prevalence of 19% in a DBN associated with cerebellar ataxia or dysarthria but without

population between the ages of 65 and 74 years who had no cerebellar atrophy on routine MRI). This form may be a distinct

disease known to cause PNP.19 nosological entity or the early manifestation of another

Among the group fulfilling the current criteria for idiopathic cerebellar degenerative disease. Follow-up studies will be needed

DBN, a subgroup of 16 patients (36%) were identified in whom to clarify this issue; and (3) a ‘‘syndromatic’’ form (ie, DBN

DBN was associated with two or all of the following disorders: associated with at least two of the following: BVP, cerebellar

cerebellar signs, BVP and/or PNP. In a recent study on four signs and/or PNP). The association of these disorders suggest

patients with cerebellar ataxia and bilateral vestibulopathy, that this syndrome may reflect a multisystem neurodegenera-

three patients also had sensory neuropathy and one patient tion or channelopathy.

DBN.20 In these patients, however, MRI revealed cerebellar

Acknowledgements: We thank Judy Benson for copyediting the text.

atrophy. Thus to the best of our knowledge this is the first

sample of patients with the specific association of DBN, BVP, Competing interests: None.

PNP and cerebellar signs without imageable cerebellar atrophy.

REFERENCES

1. Leigh RJ, Zee DS. Nystagmus due to vestibular imbalance. In: Leigh RJ, Zee DS.The

Pathomechanisms of DBN neurology of eye movements. Philadelphia: Davis, 2006:480–93.

DBN has long been associated with cerebellar lesions, particu- 2. Bertholon P, Convers P, Barral FG, et al. Post-traumatic syringomyelobulbia and

larly with those of the floccular and parafloccular lobes.8 21–23 inferior vertical nystagmus. Rev Neurol (Paris) 1993;149:355–8.

3. Halmagyi GM, Rudge P, Gresty MA, et al. Downbeating nystagmus. A review of 62

Several models of the pathomechanism of DBN have been

cases. Arch Neurol 1983;40:777–84.

suggested, among them an imbalance in the smooth pursuit 4. Bohmer A, Straumann D. Pathomechanism of mammalian downbeat nystagmus due

system, or a central or peripheral vestibular imbalance.4–7 24 to cerebellar lesion: a simple hypothesis. Neurosci Lett 1998;250:127–30.

676 J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry 2008;79:672–677. doi:10.1136/jnnp.2007.126284

Downloaded from jnnp.bmj.com on April 25, 2013 - Published by group.bmj.com

Research paper

5. Baloh RW, Spooner JW. Downbeat nystagmus: a type of central vestibular 18. Zingler VC, Cnyrim C, Jahn K, et al. Causative factors and epidemiology of bilateral

nystagmus. Neurology 1981;31:304–10. vestibulopathy in 255 patients. Ann Neurol 2007;61:524–32.

6. Pierrot-Deseilligny C, Milea D. Vertical nystagmus: clinical facts and hypotheses. 19. Mold JW, Vesely SK, Keyl BA, et al. The prevalence, predictors, and consequences

Brain 2005;128:1237–46. of peripheral sensory neuropathy in the older patients. J Am Board Fam Pract

7. Zee DS, Friendlich AR, Robinson DA. The mechanism of downbeat nystagmus. Arch 2004;17:309–18.

Neurol 1974;30:227–37. 20. Migliaccio AA, Halmagyi GM, McGarvie LA, et al. Cerebellar ataxia with bilateral

8. Kalla R, Deutschlander A, Hufner K, et al. Detection of floccular hypometabolism in vestibulopathy: description of a syndrome and its characteristic clinical sign. Brain

downbeat nystagmus by fMRI. Neurology 2006;66:281–3. 2004;127:280–93.

9. Glasauer S, Hoshi M, Kempermann U. Three-dimensional eye position and slow 21. Takemori S, Suzuki M. Cerebellar contribution to oculomotor function.

phase velocity in humans with downbeat nystagmus. J Neurophysiol 2003;89:338– ORL J Otorhinolaryngol Relat Spec 1977;39:209–17.

54. 22. Zee DS, Yamazaki A, Butler PH, et al. Effects of ablation of flocculus and

10. Williams DP, Troost BT, Rogers J. Lithium-induced downbeat nystagmus. Arch paraflocculus of eye movements in primate. J Neurophysiol 1981;46:878–99.

Neurol 1988;45:1022–3. 23. Bense S, Best C, Buchholz HG, et al. 18F-fluorodeoxyglucose hypometabolism in

11. Alpert JN. Downbeat nystagmus due to anticonvulsant toxicity. Ann Neurol

cerebellar tonsil and flocculus in downbeat nystagmus. Neuroreport 2006;17:599–

1978;4:471–3.

603.

12. Chrousos GA, Cowdry R, Schuelein M, et al. Two cases of downbeat nystagmus

24. Ito M, Nisimaru N, Yamamoto M. Specific patterns of neuronal connexions involved

and oscillopsia associated with carbamazepine. Am J Ophthalmol 1987;103:221–4.

in the control of the rabbit’s vestibulo-ocular reflexes by the cerebellar flocculus.

13. Cogan DG, Barrows LJ. Platybasia and the Arnold–Chiari malformation. AMA Arch

Ophthalmol 1954;52:13–29. J Physiol 1977;265:833–54.

14. Cogan DG. Down-beat nystagmus. Arch Ophthalmol 1968;80:757–68. 25. Strupp M, Schuler O, Krafczyk S, et al. Treatment of downbeat nystagmus with 3,4-

15. Bronstein AM, Miller DH, Rudge P, et al. Down beating nystagmus: magnetic diaminopyridine: a placebo-controlled study. Neurology 2003;61:165–70.

resonance imaging and neuro-otological findings. J Neurol Sci 1987;81:173–84. 26. Stahl JS. Eye movements of the murine P/Q calcium channel mutant rocker, and the

16. Gilman S, Low P, Quinn N, et al. Consensus statement on the diagnosis of multiple impact of aging. J Neurophysiol 2004;91:2066–78.

system atrophy. American Autonomic Society and American Academy of Neurology. 27. Stahl JS, James RA. Neural integrator function in murine CACNA1A mutants.

Clin Auton Res 1998;8:359–62. Ann N Y Acad Sci 2005;1039:580–2.

17. Abele M, Burk K, Schols L, et al. The aetiology of sporadic adult-onset ataxia. Brain 28. Kalla R, Glasauer S, Schautzer F, et al. 4-Aminopyridin improves downbeat

2002;125:961–8. nystagmus, smooth pursuit, and VOR gain. Neurology 2004;62:1228–9.

BMJ Careers online re-launches

BMJ Careers online has re-launched to give you an even better online experience. You’ll still find our

online services such as jobs, courses and careers advice, but now they’re even easier to navigate and

quicker to find.

New features include:

c Job alerts – you tell us how often you want to hear from us with either daily or weekly alerts

c Refined keyword searching making it easier to find exactly what you want

c Contextual display – when you search for articles or courses we’ll automatically display job adverts

relevant to your search

c Recruiter logos linked directly to their organisation homepage – find out more about the company

before you apply

c RSS feeds now even easier to set up

Visit careers.bmj.com to find out more.

J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry 2008;79:672–677. doi:10.1136/jnnp.2007.126284 677

Downloaded from jnnp.bmj.com on April 25, 2013 - Published by group.bmj.com

Downbeat nystagmus: aetiology and

comorbidity in 117 patients

J N Wagner, M Glaser, T Brandt, et al.

J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry 2008 79: 672-677 originally published

online September 14, 2007

doi: 10.1136/jnnp.2007.126284

Updated information and services can be found at:

http://jnnp.bmj.com/content/79/6/672.full.html

These include:

References This article cites 27 articles, 11 of which can be accessed free at:

http://jnnp.bmj.com/content/79/6/672.full.html#ref-list-1

Article cited in:

http://jnnp.bmj.com/content/79/6/672.full.html#related-urls

Email alerting Receive free email alerts when new articles cite this article. Sign up in

service the box at the top right corner of the online article.

Topic Articles on similar topics can be found in the following collections

Collections

Brain stem / cerebellum (562 articles)

Neuromuscular disease (1032 articles)

Peripheral nerve disease (520 articles)

Drugs: CNS (not psychiatric) (1436 articles)

Editor's choice (85 articles)

Notes

To request permissions go to:

http://group.bmj.com/group/rights-licensing/permissions

To order reprints go to:

http://journals.bmj.com/cgi/reprintform

To subscribe to BMJ go to:

http://group.bmj.com/subscribe/

You might also like

- Alinhador Fixturlaser DirigoDocument2 pagesAlinhador Fixturlaser DirigoJossesmsNo ratings yet

- Melissa Gomroki CVDocument2 pagesMelissa Gomroki CVapi-618835422No ratings yet

- Palliative Sedation Therapy in The Last Weeks of Life: A Literature Review and Recommendations For StandardsDocument19 pagesPalliative Sedation Therapy in The Last Weeks of Life: A Literature Review and Recommendations For StandardsMárcia MatosNo ratings yet

- Inbound 2197063521713227868Document11 pagesInbound 2197063521713227868NylNo ratings yet

- Construction Site PremisesDocument78 pagesConstruction Site PremisesDrew B Mrtnz67% (6)

- 11 - FORAGERS by Sam BoyerDocument106 pages11 - FORAGERS by Sam BoyerMurtaza HussainNo ratings yet

- Galactic Handbook and Synchronized MeditationsDocument91 pagesGalactic Handbook and Synchronized Meditationslapiton100% (10)

- NOTES - Freedom and ResponsibilityDocument7 pagesNOTES - Freedom and ResponsibilitySonnel CalmaNo ratings yet

- Arizona Independent Republic Nov 30 1938 P 42Document1 pageArizona Independent Republic Nov 30 1938 P 42Hailey LongNo ratings yet

- Expert System Assessing Threat Level of Attacks On A Hybrid SSH HoneynetDocument19 pagesExpert System Assessing Threat Level of Attacks On A Hybrid SSH HoneynetCoder CoderNo ratings yet

- Fs 4-2Document6 pagesFs 4-2api-598987483No ratings yet

- OHS-PR-09-03-F07 JOB SAFE PROCEDURE (02) Access Road and Structure PadDocument14 pagesOHS-PR-09-03-F07 JOB SAFE PROCEDURE (02) Access Road and Structure Padmohammed tofiqNo ratings yet

- Gan & Romano-8 Modern MathematiciansDocument2 pagesGan & Romano-8 Modern MathematiciansJerica GanNo ratings yet

- Practice of Washing of Hand Using Liquid Detergent Among Pupils in Owerri Municipal A Tool For Health Promotion and Health SecurityDocument5 pagesPractice of Washing of Hand Using Liquid Detergent Among Pupils in Owerri Municipal A Tool For Health Promotion and Health SecurityInternational Journal of Innovative Science and Research TechnologyNo ratings yet

- Ball and Beam WorkbookDocument31 pagesBall and Beam WorkbookCicero MelloNo ratings yet

- Handwriting Differences in Individuals With Presence and Absence of Antisocial BehaviourDocument37 pagesHandwriting Differences in Individuals With Presence and Absence of Antisocial BehaviourEditor IJTSRDNo ratings yet

- VJpSdQX3edKaXNEa 289Document40 pagesVJpSdQX3edKaXNEa 289Jesslyn AmbrocioNo ratings yet

- Cell MetabDocument21 pagesCell MetabgassemNo ratings yet

- EErcDocument108 pagesEErcRohit Ramesh KaleNo ratings yet

- Sexual abuse of females in organizations and its impact on job satisfactionDocument24 pagesSexual abuse of females in organizations and its impact on job satisfactionNatasha kumariNo ratings yet

- Medically Unexplained Symptoms Assessment and ManagementDocument6 pagesMedically Unexplained Symptoms Assessment and ManagementMatheus AzevedoNo ratings yet

- BECE Past Questions RME Objectives 2013-WPS OfficeDocument11 pagesBECE Past Questions RME Objectives 2013-WPS OfficeBENNo ratings yet

- Barron's - 2022.09.26Document63 pagesBarron's - 2022.09.26EDGAR BAUTISTA LEONNo ratings yet

- Bioterrorism An IntroductionDocument6 pagesBioterrorism An IntroductionEditor IJTSRD100% (1)

- PEER: Issue Brief: Mississippi Department of Corrections Accountability Program InventoryDocument49 pagesPEER: Issue Brief: Mississippi Department of Corrections Accountability Program InventoryRuss LatinoNo ratings yet

- Assessment and Feedback in Higher EducatDocument67 pagesAssessment and Feedback in Higher EducatSonja AndjelkovNo ratings yet

- Z-TV Guide 2022Document9 pagesZ-TV Guide 2022Cooperation and Conflict LabNo ratings yet

- SNCO COVID-19 Community Indicator Report 12-9-2021Document4 pagesSNCO COVID-19 Community Indicator Report 12-9-2021Michael K. DakotaNo ratings yet

- Barren Island Ph1 Safety FactsheetDocument2 pagesBarren Island Ph1 Safety FactsheetKevin ParkerNo ratings yet

- Ricci Psichiatriabun - It.enDocument122 pagesRicci Psichiatriabun - It.enCosmin DeaconuNo ratings yet

- 1 s2.0 S2590116822000030 MainDocument19 pages1 s2.0 S2590116822000030 MainJIANG LYUNo ratings yet

- Structure-Mapping: A Theoretical Framework For Analogy : Bolt Beranek and Newman IncDocument16 pagesStructure-Mapping: A Theoretical Framework For Analogy : Bolt Beranek and Newman IncVioleta PrietoNo ratings yet

- EMERALD TrialDocument13 pagesEMERALD TrialCristian MuñozNo ratings yet

- Univ317 Final 5Document3 pagesUniv317 Final 5Bagas KaraNo ratings yet

- Commonwealth V Malone May 1946Document44 pagesCommonwealth V Malone May 1946MindSpaceApocalypseNo ratings yet

- Alkaloids: DR N AhmedDocument23 pagesAlkaloids: DR N AhmedMohammad SamirNo ratings yet

- Birdflu 666Document406 pagesBirdflu 666sligomcNo ratings yet

- Mid TernDocument13 pagesMid TernRevy CumahigNo ratings yet

- Test Series: April, 2021 Mock Test Paper 2 Final (Old) Course Paper 1: Financial ReportingDocument16 pagesTest Series: April, 2021 Mock Test Paper 2 Final (Old) Course Paper 1: Financial ReportingPraveen Reddy DevanapalleNo ratings yet

- Essential guide to implementing newborn screening nationwideDocument300 pagesEssential guide to implementing newborn screening nationwideJosanne Wadwadan De CastroNo ratings yet

- Lanka Arrests 12 Fishermen Stalin Asks PM To Intervene: U'khand, Goa Go To Booths TodayDocument12 pagesLanka Arrests 12 Fishermen Stalin Asks PM To Intervene: U'khand, Goa Go To Booths TodayS AkashNo ratings yet

- AccountingDocument15 pagesAccountingRahul agarwalNo ratings yet

- Own Own Body Own Final ComprimidoDocument20 pagesOwn Own Body Own Final Comprimidoapi-609236458100% (1)

- Typical goals of malware and their implementationsDocument47 pagesTypical goals of malware and their implementationsSaluu TvTNo ratings yet

- Grizzly Industrial, 15" Planer Instruction ManualDocument45 pagesGrizzly Industrial, 15" Planer Instruction ManualkatfishisgreatNo ratings yet

- ChargesDocument62 pagesChargessudhirNo ratings yet

- Clinical Assessment of Antibiotic Use in CKD PatientsDocument8 pagesClinical Assessment of Antibiotic Use in CKD PatientsMITA RESTINIA UINJKTNo ratings yet

- CGL 2020 GST Inspector, Po & Examiner State Wise VacancyDocument8 pagesCGL 2020 GST Inspector, Po & Examiner State Wise VacancyAmlan DuttaNo ratings yet

- Enduro World Series 2022 - #3 Val Di Fassa - Day 1Document30 pagesEnduro World Series 2022 - #3 Val Di Fassa - Day 1MTB-VCONo ratings yet

- Financial Analysis of Indian Oil CorporationDocument29 pagesFinancial Analysis of Indian Oil CorporationNikshith HegdeNo ratings yet

- Manual Therapy: Critical Assessment Profession of Physical Therapy Role TheDocument10 pagesManual Therapy: Critical Assessment Profession of Physical Therapy Role TheManuel Silva HérnandezNo ratings yet

- A1 Speaking Book FINALDocument60 pagesA1 Speaking Book FINALVũ Quốc ĐạiNo ratings yet

- TiC CMS RecsDocument4 pagesTiC CMS RecsJakob EmersonNo ratings yet

- Colorado Health Foundation 2022 Pulse PollDocument97 pagesColorado Health Foundation 2022 Pulse PollMichael_Roberts2019No ratings yet

- Bài tập tự động hóa sản xuất - 0001-0001Document1 pageBài tập tự động hóa sản xuất - 0001-0001Minh NhậtNo ratings yet

- 10 1021@acs Iecr 0c00181Document42 pages10 1021@acs Iecr 0c00181JUAN EDUARDO LEON HUAMANINo ratings yet

- Harris SX-1 Operators ManualDocument46 pagesHarris SX-1 Operators ManualLuis AhmedNo ratings yet

- Business License Revocation Letter. Naomi I. Halter.1Document3 pagesBusiness License Revocation Letter. Naomi I. Halter.1T RNo ratings yet

- Guide to Writing Effective Essays for English Proficiency TestsDocument25 pagesGuide to Writing Effective Essays for English Proficiency Testslê myNo ratings yet

- Representations and Implications of Papers Written by E.T. Whittaker in 1903 and 1904 (Latex PDFDocument6 pagesRepresentations and Implications of Papers Written by E.T. Whittaker in 1903 and 1904 (Latex PDFMark TitlemanNo ratings yet

- Chapter 8Document57 pagesChapter 8بو تركيNo ratings yet

- 723 FullDocument11 pages723 Fullclaudia velaNo ratings yet

- cVEMP y oVEMP en ESCLEROSIS MULTIPLEDocument8 pagescVEMP y oVEMP en ESCLEROSIS MULTIPLEJaneth GuzmanNo ratings yet

- Ni602201-1217753 032257Document10 pagesNi602201-1217753 032257Vinay GNo ratings yet

- WdweDocument7 pagesWdweVinay GNo ratings yet

- CP Angle SOLDocument8 pagesCP Angle SOLVinay GNo ratings yet

- 55 Year Old Male With Back Pain and RadiculopathyDocument7 pages55 Year Old Male With Back Pain and RadiculopathyVinay GNo ratings yet

- Bhagavad Gita - With Sri Shankaracharya CommentaryDocument508 pagesBhagavad Gita - With Sri Shankaracharya CommentaryEstudante da Vedanta100% (24)

- CerebellumDocument10 pagesCerebellumVinay GNo ratings yet

- Comparing The Efficacy of Short Segment Pedicle.43Document5 pagesComparing The Efficacy of Short Segment Pedicle.43Vinay GNo ratings yet

- My File TDocument1 pageMy File TVinay GNo ratings yet

- My File To DownloadsDocument1 pageMy File To DownloadsVinay GNo ratings yet

- My File TDocument1 pageMy File TVinay GNo ratings yet

- My File To DownloadsDocument1 pageMy File To DownloadsVinay GNo ratings yet

- Gane SanDocument7 pagesGane SanVinay GNo ratings yet

- My File To DownloaDocument1 pageMy File To DownloaVinay GNo ratings yet

- My File To DownloadDocument1 pageMy File To DownloadVinay GNo ratings yet

- My FileDocument1 pageMy FileVinay GNo ratings yet

- My FileDocument1 pageMy FileVinay GNo ratings yet

- 0610 m16 QP 62Document12 pages0610 m16 QP 62faryal khanNo ratings yet

- Chapter 14 Chemical EquilibriumDocument29 pagesChapter 14 Chemical EquilibriumlynloeNo ratings yet

- S2 Papers FinalizedDocument149 pagesS2 Papers FinalizedRaffles HolmesNo ratings yet

- A Review: HPLC Method Development and Validation: November 2015Document7 pagesA Review: HPLC Method Development and Validation: November 2015R Abdillah AkbarNo ratings yet

- Common Mistakes in Dimensional Calibration MethodsDocument16 pagesCommon Mistakes in Dimensional Calibration MethodssujudNo ratings yet

- Textile Internship Report AlokDocument39 pagesTextile Internship Report AlokRahul TelangNo ratings yet

- Tejas: Practice Sheet JEE PhysicsDocument3 pagesTejas: Practice Sheet JEE PhysicsAshree KesarwaniNo ratings yet

- Essay - DnaDocument2 pagesEssay - Dnaapi-243852896No ratings yet

- List of Students Allotted in Open Elective Subjects (B. Tech and M. Tech (Dual Degree) Integrated MSc. - 4th Semester - Regular - 2018 - 19) - 2 PDFDocument26 pagesList of Students Allotted in Open Elective Subjects (B. Tech and M. Tech (Dual Degree) Integrated MSc. - 4th Semester - Regular - 2018 - 19) - 2 PDFArpan JaiswalNo ratings yet

- MidtermDocument3 pagesMidtermTrisha MondonedoNo ratings yet

- Philips HF C-Arm BrochureDocument2 pagesPhilips HF C-Arm Brochuregarysov50% (2)

- BAlochistanDocument14 pagesBAlochistanzee100% (1)

- Musical Siren Project Report Under 40 CharactersDocument10 pagesMusical Siren Project Report Under 40 Charactersvinod kapateNo ratings yet

- GLOBAL GAME AFK IN THE ZOMBIE APOCALYPSE GAME Chapter 201-250Document201 pagesGLOBAL GAME AFK IN THE ZOMBIE APOCALYPSE GAME Chapter 201-250ganesh sarikondaNo ratings yet

- MD R2 Nastran Release GuideDocument276 pagesMD R2 Nastran Release GuideMSC Nastran BeginnerNo ratings yet

- Detecting Oil Spills from Remote SensorsDocument7 pagesDetecting Oil Spills from Remote SensorsFikri Adji Wiranto100% (1)

- Chemistry of Food Changes During Storage: Group 7Document22 pagesChemistry of Food Changes During Storage: Group 7Sonny MichaelNo ratings yet

- Managed Pressure Drilling MPD BrochureDocument5 pagesManaged Pressure Drilling MPD Brochureswaala4realNo ratings yet

- Understanding of AVO and Its Use in InterpretationDocument35 pagesUnderstanding of AVO and Its Use in Interpretationbrian_schulte_esp803100% (1)

- Well Rounded.: 360 CassetteDocument12 pagesWell Rounded.: 360 CassetteMonty Va Al MarNo ratings yet

- Rajagiri Public School Unit Test PhysicsDocument3 pagesRajagiri Public School Unit Test PhysicsNITHINKJOSEPHNo ratings yet

- PMR205 DR Shawn BakerDocument31 pagesPMR205 DR Shawn Bakerspiridon_andrei2011No ratings yet

- Barney's Great Adventure - Barney Wiki - WikiaDocument2 pagesBarney's Great Adventure - Barney Wiki - WikiachefchadsmithNo ratings yet

- Week 7: Nurses Role in Disaster: Home Mitigation and PreparednessDocument10 pagesWeek 7: Nurses Role in Disaster: Home Mitigation and PreparednessRose Ann LacuarinNo ratings yet

- Bosch EBike Product Catalogue MY2021 enDocument92 pagesBosch EBike Product Catalogue MY2021 enIvanNo ratings yet

- State of The Art in Roller Compacted Concrete (RCC) PDFDocument226 pagesState of The Art in Roller Compacted Concrete (RCC) PDFEduardoDavilaOrtegaNo ratings yet

- EE 102 Cabric Final Spring08 o Id15Document10 pagesEE 102 Cabric Final Spring08 o Id15Anonymous TbHpFLKNo ratings yet