Professional Documents

Culture Documents

This Content Downloaded From 196.191.248.6 On Fri, 06 May 2022 17:05:39 UTC

Uploaded by

Tahir DestaOriginal Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

This Content Downloaded From 196.191.248.6 On Fri, 06 May 2022 17:05:39 UTC

Uploaded by

Tahir DestaCopyright:

Available Formats

Maximizing Tax Revenue while Minimizing Political Costs

Author(s): Richard Rose

Source: Journal of Public Policy , Aug., 1985, Vol. 5, No. 3, Taxation (Aug., 1985), pp.

289-320

Published by: Cambridge University Press

Stable URL: https://www.jstor.org/stable/3998441

JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide

range of content in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and

facilitate new forms of scholarship. For more information about JSTOR, please contact support@jstor.org.

Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of the Terms & Conditions of Use, available at

https://about.jstor.org/terms

Cambridge University Press is collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve and extend access

to Journal of Public Policy

This content downloaded from

196.191.248.6 on Fri, 06 May 2022 17:05:39 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

Jnl Publ. Pol., 5, 3, 289-320

Maximizing Tax Revenue While Minimizing

Political Costs

R I C H A R D R O S E, Public Poliy, University of Strathclyde

ABSTRACT

Tax revenue is a function of laws and administration as well as economic

activity. Four different theories purport to explain revenue-raising in

contemporary Western nations: universal abstractions about economic

systems; national culture: tax-specific characteristics; avoiding political

costs through political inertia. OECD data on taxation in Western

nations since I 955 show that national tax systems do not have sufficient in

common to validate universalistic generalizations Tax-specific influences

can be identified only for a few major sources of revenue. The inertia

persistence of substantial national distinctiveness reflects a non-decision

making approach to tax policy by politicians. The strategy is to rely

primarily upon revenue-buoyant taxes authorized by past legislation

rather than risk the political blame for introducing new taxes to raise large

amounts of needed additional revenue.

Question to Willie Sutton: Why do you rob banks?

Answer: Because that's where the money is.

The need for revenue is a constant of government, and taxes are the

principal source of government revenue. Following the American bank

robber, Willie Sutton, we can say that governments levy taxes because

that's where the money is. Reliable means of raising public money are

essential for the growth of government (cf. Hinrichs, I966; Braun, 1975;

Ardant, I975). The point is fundamental, yet studies of taxation in

developed nations tend to concentrate attention upon the equity, the

efficiency and the economic effects of tax systems. Whatever other criteria

may be applied, in an era of big government policymakers must

necessarily evaluate taxes in revenue terms.

* The research reported herein is part of a programme on the Growth of Government supported

by British Economic & Social Research Council grant HR 7849/I. The author benefited

from being a visiting scholar in the Fiscal Affairs Department of the International Monetary

Fund in 1984, and from comments by James E. Alt, David Heald, John Kay, Joseph Pechman,

Ann Robinson, and Peter Saunders. None of the aforementioned is responsible for the interpretation

herein.

This content downloaded from

196.191.248.6 on Fri, 06 May 2022 17:05:39 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

290 Richard Rose

Although taxes are necessary, they are not popular. Because taxation is

not confined to countries with free elections, any theory explaining

taxation in terms of popular choice is inappropriate for most countries in

the world today. Since citizens in democratic political systems do not pay

taxes voluntarily, knowledge of the psychology of taxation (cf. Lewis,

I982; David, I98I) cannot substitute for the study of tax revenue.'

Because taxation is viewed as politically costly, politicians do not

volunteer to raise taxes, nor need they do so, for large amounts of

government revenue are routinely raised by established tax laws and

administration.

In order to understand how governments maximize tax revenue while

minimizing political costs, theories should be tested comparatively, since

they propose generalizations that are meant to be true of many different

countries, and of many different taxes. The first section of this paper

identifies four broad theories: universalism; national culture and

institutions; tax-specific determination; and taxation by inertia. The

subsequent sections set out evidence providing robust tests of these ideas

by the systematic analysis of revenues from io major taxes in 20 OECD

nations since 1955.

i. Alternative theories of raising tax revenue

A generic model of taxation is inevitably a public policy model, because

the-chief determinants of revenue-raising are in different domains of the

social sciences - law, public administration, and applied economics - as

well as accountancy and business studies, subjects ignored by most social

scientists but certainly not irrelevant in taxation. Tax revenue (TR)

results from the interaction of laws, administrative actions, and economic

activity. At any given point in time, the revenue yield of a given tax is a

function of the law (L) defining the tax rate and base; administrative

actions (A) taken to apply the law to the base; and the economic activity

(E) defined by law as the base for the tax.

(i) TR = f(L, A, E)

We cannot derive the revenue of the fisc solely from knowledge of the

economy. We must also know what the law defines as taxable, what rate of

tax is levied, and the effectiveness of administrators in collecting tax that

is lawfully due.

Total Tax Revenue (TTR) is the sum of revenue yields from dozens of

different taxes levied within a nation.

(2) TTR = YXfs (Li, A, Ei)

This content downloaded from

196.191.248.6 on Fri, 06 May 2022 17:05:39 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

Maximizing Tax Revenue While Minimizing Political Costs 291

It follows that to understand total tax revenue it is necessary to consider

many different taxes, each of which is a function of particular tax laws and

administrative procedures, and a variety of activities within the economy.

The properties of taxation that are most important in revenue-raising

are two. The first is the percentage of a country's total tax revenue raised

by a given tax, a measure of its relative importance. Secondly, the

percentage of the gross domestic product claimed by a given tax is a

measure of tax effort.

Tax revenue can change by increasing or decreasing, or it may remain

relatively static. Whereas measures of change in a tax's share of total

revenue require that the sum of increases be offset by decreases since the

total remains constant at IOO per cent, measures of tax effort can show all

taxes changing in the same direction. It is also possible for a tax to increase

its claim on the national product, yet decrease its contribution to total

revenue.

Four theories will be considered here, each different in their hypotheses

about the behaviour of specific taxes, whether compared within a nation

or cross nationally.

(i) Universalism. If economics is a science like physics, then variations in

time and place should be of little importance; economic laws (sic) should

be universally applicable. There is even greater reason to expect

universalistic propositions to be true among OECD nations, whose

economies and administrative capabilities are relatively similar when

viewed from a global perspective (cf. Chenery and Syrquin, 1975; Taylor,

I 98 I; Goode, I 984). The broadest universalistic hypothesis is that

taxation should be much the same everywhere, and taxes should change

in much the same way.

A modified universalistic hypothesis is that convergence in taxation is

occurring within OECD nations. Convergence theories recognize the

existence of historical differences between nations, and that some OECD

economies are more modern - or have been modern longer - than others.

The reasons for convergence may reflect economic, political or social

factors. For example, Alt (I983: I92) refers to 'the imperative of

redistribution' as a common influence upon taxation in democratic

political systems. It follows from this assumption that progressive taxes

should be increasing in importance, and regressive taxes declining.

(2) Tax-specific homogeneity. Every textbook of public finance devotes

much space to anatomizing the differences between taxes, e.g. direct and

indirect, or taxes with more or less effective tax handles. The implied

corollary is that each type of tax operates much the same regardless of

the country in which it is employed; its principal characteristics are

assumed to be tax-specific rather than universal. A study of the dynamics

of different taxes within the United Kingdom concludes: 'It is therefore

This content downloaded from

196.191.248.6 on Fri, 06 May 2022 17:05:39 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

292 Richard Rose

reasonable to hypothesize that there are greater similarities between the

same tax in different countries than there are between different taxes

within the same country' (Rose and Karran, I983: 47).

Theories of tax-specific determination both particularize and general-

ize. They hypothesize that many differences between taxes will occur

within a nation. Yet the theories also hypothesize that there will be

consistent regularities; a particular tax will everywhere display much the

same characteristics whatever the national context.

(3) National culture. Much legal and institutional analysis of taxation is a

discussion of tax history rather than tax theory. The history examined is

national. The yield of a particular tax in a particular country at a

particular moment in time is explained by reference to the initial

enactment of a tax and subsequent amendments, and by the evolution of

tax administration and economic activity within a particular national

setting. The term culture is a shorthand phrase to describe the

contemporary residue of influences from this past.

In the most literal sense, theories of national culture may be interpreted

as assuming that every country's tax system is unique. But differences can

occur without leading to uniqueness. Differences in the revenue yield from

particular taxes or total tax revenue are differences of degree, not kind.

Only if differences of degree are pervasively important can uniqueness be

demonstrated. In a modified form, such theories can be treated as

hypothesizing national distinctiveness, rejecting the idea of specific

attributes of taxes being important cross-nationally. At a minimum, it is

hypothesized that national differences will persist for many decades, or

even that OECD nations will become increasingly dissimilar in revenue-

raising.

(4) The force of inertia. This theory starts from the universalistic

assumption that politicians wish to avoid the political costs of voting to

raise taxes. But it also accepts that in an era of big government,

policymakers must have large and increasing flows of tax revenue to

finance programmes that tend to increase in cost from year to year. The

problem is: How can politicians maximize tax revenue while minimizing

political costs?

Inertia is here a force in motion, characterizing tax laws and adminis-

trative agencies that remain in force from year to year. A newly elected

government does not need to vote new taxes in order to raise revenue.

It can simply enforce laws enacted by its predecessors. Administrative

structures provide the continuing institutional resource to dojust this. In

law, tax officials cannot do otherwise; bureaucrats are bound to collect

taxes. To emphasize the continuance of tax policies from a nation's past is

to reject universalist theories, for OECD nations differ in their tax

histories. It also means that the government of the day does not choose a

This content downloaded from

196.191.248.6 on Fri, 06 May 2022 17:05:39 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

Maximizing Tax Revenue While Minimizing Political Costs 293

particular tax system. The system is the cumulative result of past laws

enforced by present administration; it is not a choice by today's

governors.

The inertia model of taxation hypothesizes that the simplest thing for

politicians to do is to do nothing, that is, to maintain the nation-specific

structure of taxation that it has inherited from (and therefore can blame

upon) its predecessors. The theory thus rejects the conventional

assumption of political scientists and economists that politicians desire

and do make frequent and visible choices about taxation (cf. Roskamp

and Forte, I98I; Robinson and Sandford, I983; Alt, I983). The 'free

policy choice' that Musgrave thought (I969: I47) available to a country

with a rising national product is not available in a high-spending high-tax

country today. Nor is it necessary. Passivity does not mean defaulting on

tax collection; instead, it means enforcing past laws to provide current

revenue. Seemingly small annual increases can compound into large

revenue increases from one election to the next, or from one decade to the

next (cf. Rose and Karran, I984).

The inertia theory of taxation rejects conventional theories of optimal

taxation. As Martin Feldstein (1976: 77) has emphasized:

Discussions of optimal taxation implicitly assume that the tax laws are being

written de novo on a clean sheet of paper. Such tax design is a guide for tax policy in

the Garden of Eden. The optimal tax laws for the next year are not the same as

they would be if taxes were being introduced for the first time. Optimal taxation

depends on the historical context.

Insofar as OECD nations have differed in their national tax systems in

the past, the inertia hypothesis is that they will continue to differ in the

present. Convergence is explicitly rejected, as well as more comprehensive

universalist theories. Tax-specific determinants of revenue are not

necessarily in conflict with determination by inertia. The two theories can

even be complementary. The inertia theory can explain why major

historical differences from the past persist into the present, whereas

properties of particular taxes can explain why, without any action by

government, the revenue yield of some taxes (e.g. progressive income tax)

can rise and the relative yield of other taxes (e.g. excise taxes with fixed

tariffs) fall.

Whatever the relative aesthetic attractiveness of one or another theory,

validity depends upon empirical testing. As a detailed analysis of taxation

within a single nation emphasizes:

The ways in which actual taxes differ from these theoretical taxes are often of

much greater economic significance than the ways in which theoretical taxes

differ from each other (Kay and King, I983:1).

This content downloaded from

196.191.248.6 on Fri, 06 May 2022 17:05:39 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

294 Richard Rose

Hence, it is important to test theories of taxation across nations, across

categories of taxation, and across time.

2. Testing for universalism and convergence

Contemporary economic theory is universalistic; the basic elements of an

economic system are identified by stipulation, and statements about

relationships normally exclude nation-specific and historical contexts. It

is possible to conceive of differences between economic systems, but these

differences are normally described in abstract terms. Differences between

economic theories usually reflect differences in theoretical assumptions

and interpretations rather than national differences. The basic assumption

of universalism is: all nations are much the same.

Universalist theories may be advanced in a modified form, hypothesiz-

ing a tendency toward convergence in taxation among advanced

industrial nations (Bell, 1973; Kerr, I983). Convergence theories

recognize that while in the past there have been major differences in

taxation between OECD nations, for example, between late and early

industrializers, or between Mediterranean and Northern European

nations, the causes are now remote in time. As 'laggard' OECD countries

become more industrialized, they should more closely approximate

universalistic norms. Convergence theories are particularly appropriate

for the era since the I 950s, which has been marked by a conscious effort to

increase the openness of national economies to international influences,

such as foreign trade and multinational corporations, and the growth of

institutions consciously dedicated to promoting tax harmonization, such

as the European Community, and of institutions diffusing ideas of best

practice among nations, such as the OECD and the International

Monetary Fund.

Theories of national culture emphasize the opposite hypothesis:

nations differ from each other. When one turns from the analysis of an

economic system in the abstract to systematic comparison between

nations, then properties of taxation that are constant by stipulation

become potentially variable. This is true not only of comparisons between

high, middle-income and low-income countries, but also within each

category of nation (cf. Tanzi, I982). According to theories of national

culture, averages calculated from OECD statistics tell us little about

particular countries, for the deviation around the mean is expected to be

great.

The emphasis upon national culture leads to the hypothesis that

OECD nations are diverging in their national tax systems. This follows

from Hinrich's (i 966: i o6f) analysis of the fiscal consequences of

economic development. Traditional societies commonly rely upon force to

This content downloaded from

196.191.248.6 on Fri, 06 May 2022 17:05:39 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

Maximizing Tax Revenue While Minimizing Political Costs 295

extract taxes, and transitional societies rely upon taxes on trade. The

diversity of resources available for taxation in a modern economy is

assumed to offer countries major opportunities to differ in their tax

systems in accord with cultural or other nation-specific characteristics.

The 'politics matters' approach (Castles, I982) offers another theory of

divergence. Control of government over a long period of time by a leftwing

or a rightwing party is hypothesized to create major differences between

national tax systems.

Among the 20 OECD nations selected for analysis here, there is far

more reason to expect an identity, or at least a great similarity of tax

characteristics, than among a global universe. By definition, all OECD

nations are advanced industrial nations, and are subject to political

pressures from a mass electorate.2 The exclusion here of three intermit-

tently democratized and industrializing entrants to OECD, Greece,

Portugal and Turkey, strengthens the presumption.

Whereas national culture theories hypothesize that OECD nations

should differ in their level of aggregate taxation, universalist theories

hypothesize that all countries should take much the same proportion of

the gross domestic product in tax. There is a great deal of similarity in the

tax effort of OECD countries today. In I982 the average nation claimed

38.4 per cent of its national product in taxation; the standard measure of

dispersion around the mean, the coefficient of variation, is very low, o. i 8.

The outliers - Sweden, claiming 50.3 per cent of GDP in taxation, and

Japan, 27.6 per cent - are just that, exceptions to a common pattern. In

1955, the earliest year for which OECD provides detailed comparative

data on tax revenues3, the average nation's tax was one-third lower, 25.2

per cent of the national product. But this difference in aggregate taxation

did not reflect greater diversity among nations. The coefficient of

variation was also low, o. i6. A high similarity in aggregate tax effort has

been maintained, even though individual nations have varied consider-

able in their ranking compared to the moving OECD mean.4

In order to test whether a nation's total tax yield is relatively

homogeneous and thus adequately represented by an aggregate measure

of total tax, it is necessary to examine the principal types of taxes that

collectively constitute the aggregate yield. To do this is sometimes

misleadingly referred to as disaggregation; it is better viewed as

non-aggregation, the inspection of particular taxes before they disappear

in the melting pot of total revenue.

OECD provides the most comparable and comprehensive tax data for

empirically testing theories of revenue-raising (OECD, 1984; Messere,

I983). The assignment of national revenues to tax categories is done after

discussion with staff from relevant national ministries. IMF accounts

itemize taxes in more detail; however, the greater the number of tax

This content downloaded from

196.191.248.6 on Fri, 06 May 2022 17:05:39 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

296 Richard Rose

categories enumerated, the smaller the average proportion of revenue

contributed by any one category. For example, in France the IMF (I983:

284-85) reports tax revenues under I 37 different headings, but 82 of these

categories produces less than O.OI per cent of revenue, and only nine

contribute as much as I.0 per cent to total tax revenue. The IMF

categories are thus too detailed to be useful here.

The median OECD country levies 20 different types of taxes. France

and Britain rank highest, levying 26 and 25 types of taxes, and New

Zealand and Australia rank lowest, levying I4 and I5 taxes respectively.

It could be hypothesized that the higher the level of taxation, the greater

the number of taxes used, as the pressure for more revenue drives

government to seek money in more and more ways; in fact, this is not the

case. The correlation between tax revenue as a proportion of a country's

gross domestic product and the number of taxes used is very low, o.o8. Nor

does the multiplication of taxing jurisdictions increase the number of

taxes; the correlation is o.oo between the sub-national (that is, regional

and local) share of total tax revenue and the number of taxes.

The tax categories employed here have been aggregated from the initial

47 OECD categories on the basis of two criteria, a revenue yield of more

than one per cent of total tax revenue, and use by at least half of OECD

countries. The io tax categories are: income tax, corporation tax, social

security, payroll, property, wealth, VAT and sales, customs, excise, and

otherwise unclassified. To have settled on only two categories, such as

direct and indirect taxes, would have assumed that the components of

each category were empirically similar in revenue yield across nations.

This has elsewhere been shown not to be so (Rose, I984: I07). Examining

the revenue yields of each category of taxes demonstrates that no

substantial source of tax revenue is omitted by the choice of this level of

aggregation. The median contribution to the 20 national tax systems by

the residual unclassifiable category is 0.2 per cent.

If the national tax systems of OECD countries are identical or very

similar, as universalist theories propose, then the proportion of revenue

contributed by each category of taxation should be much the same

cross-nationally, even if the amount that each contributes to national

revenue differs. The similarity in total tax revenue is consistent with this

assumption but not proof, for similarities in aggregate could simply

represent a tendency for cross-national differences to cancel out. For

example, if half the countries were low in income tax and high in sales tax

and the other half the opposite, all could have much the same aggregate

revenue, whilst having two very different types of national tax systems.

In fact, there are substantial cross-national differences in the minimum

and the maximum amount of revenue raised by specific taxes (Table i).

For income tax, which contributes an average of 33 per cent of revenue,

This content downloaded from

196.191.248.6 on Fri, 06 May 2022 17:05:39 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

Maximizing Tax Revenue While Minimizing Political Costs 297

the variation is between 6I per cent in New Zealand and I3 per cent in

France; for seven taxes the minimum contribution to national revenue is

less than one per cent in at least one country.

A central assumption of universalist theories of taxation is that the

proportion of revenue raised by a given tax is much the same in every

country. The cases at the extreme ends of the range in Table i are assumed

to be exceptions to a tendency for all nations to converge around the mean.

This assumption can be tested by regarding the mean amount of revenue

that different tax categories contribute to the total tax revenue of OECD

nations as the elements of a Standard Tax System. In the Standard Tax

System, income tax contributes 33 per cent of total revenue, social security

24 per cent, and so forth, down to i per cent from payroll taxes and

otherwise unclassifiable taxes (Table i).

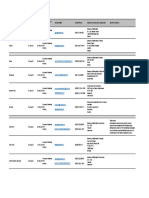

TABLE I. Cross-national variations in the use of specific taxes

National Range

Tax Mean Highest Lowest

(as % contributed to

Income 33 6i New Zealand 13 France

Social security 24 45 Italy o Australia, NZ

VAT and sales I4 22 Denmark o Japan

Excise I 2 25 Ireland 2 Luxembourg

Corporation 8 i6 Norway 3 Denmark

Property 3 I I UK 0.004 Italy

Wealth and estate 2 7 Switzerland o.8 Canada

Customs 2 6 Spain o.s Norway

Payroll I 6 Austria o ii countries

Unclassifiable I 4 Japan o 6 countries

Source: Data for this and other tables, unless otherwise noted, collected by the Fiscal Affairs

Division of OECD, and published most comprehensively in Revenue Statistics of OECD

Member Countries (Paris: OECD, 1984). The analysis is the responsibility of the author.

The extent to which a given national tax system is identical to the

Standard Tax System can be measured by a simple distance index, the

arithmetic sum of the differences between the percentage of total revenue

raised by a particular type of tax in the standard system, and a particular

country's share. For example, if a country raises 38 per cent of its tax

revenue from income tax instead of the average of 33 per cent, it is 5 per

cent distant from the Standard, and if it raises 2 per cent from payroll taxes

instead of the I per cent average, this contributes another I per cent to the

total distance. The index thus controls fully for the revenue importance of

each type of tax. The greater the similarity between a country's National

Tax System and the Standard Tax System, the closer the index is to o; the

greater the difference, the higher the index number.

This content downloaded from

196.191.248.6 on Fri, 06 May 2022 17:05:39 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

298 Richard Rose

Universalistic theories posit that the actual distance of OECD nations

from the Standard Tax System should be low for nearly every country,

and consistently so through the years. In its weaker form, convergence

theories predict that whatever the differences among OECD nations in

1955, substantial convergence toward the Standard Tax System should

have occurred since.

In fact, the national tax systems of OECD nations are heterogeneous;

the average OECD nation was 42 per cent distant from the Standard Tax

System in I982 (Table 2). The Standard Tax System is an analytical

abstraction rather than a good guide to the tax practices of most OECD

countries. Deviations from the Standard Tax System are greatest in New

Zealand (65 per cent), Australia (64 per cent) and Denmark (6 I per cent),

which do not make much use of a social security tax. France is very far

from the norm (6o per cent) for the opposite reason, relying upon social

security taxes for 43 per cent of total revenue as against 24 per cent in the

TAB L E 2. National distance from standard tax system

Convergence (-)

Distance Distance Distance Divergence (+)

Index, I955s Index, 1965 Index, 1982 I955-82a i965-82

New Zealand 30 55 65 +35 +IO

Australia 36 50 64 +26 +14

Denmark 56 54 6i +5 +7

France n.a. 65 6o n.a. -5

Spain n.a. 44 50 n.a. +6

Finland 29 34 49 +20 +I5

Japan 36 44 48 + I2 +4

Italy 57 52 46 -I I -6

Luxembourg n.a. 40 40 n.a. 0

Austria 59 40 39 -20 -I

Netherlands 27 3I 39 + I 2 +8

Ireland 72 64 38 -34 -26

Canada 34 40 37 +3 -3

Norway 35 43 35 0 -8

Switzerland 28 4I 33 +5 -8

United Kingdom 24 35 3I +7 -4

Germany 45 26 29 -i6 +3

USA 44 37 28 -i6 -9

Sweden 6i 44 25 -36 -i9

Belgium 48 47 23 -25 -24

Average 42 44 42 -i.6 -2

a In I955 excise and customs must be collapsed into a single category, and data for three

countries is missing. If the i982 data is formatted to match that for 17 countries in I955,

the Distance Index is on average only one per cent less.

(The distance index is calculated by subtracting the share of revenue yielded by a given

tax in a given country from the average OECD share of revenue raised by the tax, as reported

in Table i, and summing the results without regard to the sign.)

This content downloaded from

196.191.248.6 on Fri, 06 May 2022 17:05:39 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

Maximizing Tax Revenue While Minimizing Political Costs 299

Standard System. Belgium and Sweden deviate least from the Standard

Tax System, 23 and 25 per cent respectively.

In theory, nations could differ from the Standard Tax System because

they grouped into two clusters, for example, according to leftwing or

rightwing governments, or Romance or Anglo-Saxon tax cultures.5 The

extent to which nations high on one tax are similarly positioned on

another can be assessed by a comprehensive correlation matrix of the

share of revenue each tax contributes to its national tax systems. Among

the 36 correlations in the matrix, only three are statistically significant, and

only one theoretically interesting, which is the -o.8i correlation between

the proportion of revenue coming from income tax and social security. But

this difference is not the basis for a typology differentiating national tax

systems as a whole.6 The test for homogeneity reveals heterogeneity

between tax systems.

The disparaties emphasized by historians of national tax systems

suggest that distance from the Standard Tax System was even greater in

the past. But when national tax systems are compared across time to test

for relative convergence since 1955, no convergence is found (Table 2). In

1955 the mean distance was 42 per cent. The country closest to the

Standard then was Britain, an old industrial nation (24 per cent), and the

country furthest, agrarian Ireland (72 per cent). In the next decade

changes occurred within every national tax system. The net effect was a

slight divergence; the mean distance index rose from 42 per cent to 44 per

cent in I965. France had become the nation most different from the

Standard, and Germany the country least distant. The change between

I965 and I982 was slight, averaging two per cent toward the Standard.

After more than a generation of active international economic collabora-

tion and trade, the average OECD nation was 42 per cent distant from a

Standard Tax System in I982, the same as in I955.

Nations are as likely to diverge from the Standard Tax System as to converge.

Between 1955 and I982, seven of the 17 nations examined moved toward

the Standard System, but nine moved away from it, and one did not

change. In the period from I965 to I982, one nation did not change its

distance, eleven moved toward the Standard System, and eight diverged.

There are as many countries moving away from the Standard Tax System

as toward it.

The absence of an identity between tax systems of OECD nations is

consistent with theories that explain tax systems as products of national

cultures. The initial choice of taxes can reflect past cultural conditions.

The inertia of laws and administration can make a particular national

mixture persist. Differences between nations would thus be perpetuated

as a consequence of inertia within a nation. But the distance index also

shows the limits of national influences. Whilst the mean distance of 42 per

This content downloaded from

196.191.248.6 on Fri, 06 May 2022 17:05:39 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

300 Richard Rose

cent is a substantial departure from o, it is far from the maximum. While

countries differ in the extent to which they make use of particular taxes,

usually the differences are a matter of degree, not kind.

Insofar as national cultures are important, then they should affect all

taxes equally. This does not mean that all taxes should raise an equal

amount of revenue; revenue distribution is so skewed that the coefficient of

variation for the revenue yield within national systems is over I.oo in all

but one OECD country. A few big taxes produce most revenue, and a

large number make only small contributions to the fisc.

The most appropriate test for the influence of national cultures is

dynamic; all taxes should change in the same direction through time. This

is consistent with the ordinary citizen's complaint that taxes are going up,

which implies that all taxes of a government are going up.

When changes in the share of revenue contributed to the national tax

system are compared across OECD nations since I955, the results show

no uniformity within a national culture. Instead of shares remaining

uniform in response to uniform cultural pressures, in the average country

three taxes increase their contribution to the revenue, and five decrease

their share. In 14 of 20 nations, more taxes have decreased their

contribution to the national tax system than increased it. For every

example of a tax increasing in relative significance within a nation, at least

one counter-example can normally be cited.

Since any increase in the share of a national tax system necessarily

requires a decrease to offset growth, the stronger test of a common

national propensity for taxes to change in the same direction is to examine

the proportion of the national product collected by each tax. Given that

total revenue as a proportion of the national product has risen on average

by one-half in the period under review, all taxes could be going up on this

measure.

Within every OECD country taxes move in opposite directions in their

claim on the national product. On average, 4.9 taxes have increased their

share of the national product, and 3.I have contracted since I955. No

country has had all its taxes increase claims on the national product.

Notwithstanding the fact that within a nation all taxes are subject to many

common political, administrative, and economic influences, there is no

homogeneity in the movement of taxes within a national culture.

3. Testing for tax-specific homogeneity

Theories of tax-specific homogeneity start from the recognition that taxes,

like nations, can be differentiated in a host of ways. Taxes may be levied on

products or on services or on people; on sellers or buyers; on individuals or

households or corporate entities; directly or indirectly; progressively or

This content downloaded from

196.191.248.6 on Fri, 06 May 2022 17:05:39 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

Maximizing Tax Revenue While Minimizing Political Costs 30I

regressively; by fixed or ad valorem rates; by centralized or decentralized

administration; and with greater or lesser popularity among the

electorate.

The corollary of within-nation differences between taxes is between-

nation similarity within a specific tax category. A tax that is defined as

direct will be direct in Australia or Austria, and a tax regarded as

progressive should have the same effect in Sweden or Switzerland;

properties of specific taxes are independent of national context. While

national laws may vary the rate of a tax or its coverage, a social security

tax remains a social security tax whatever its rate and coverage, as

long as it is an earmarked tax entitling a person to receive social security

benefits.

In this revenue-oriented study of taxation, the most important

difference is between taxes making a substantial contribution to the total

revenue yield, here described as major taxes, and taxes that make a minor

contribution. When comparing taxes, we should not impose a false

equality, discussing each tax as if it were of equal importance to the fisc.

Nor would it here be appropriate to treat at length theoretically

interesting taxes that have little impact upon total revenue, as is often

done in proposals for tax reform.

Even though every nation has dozens of taxes, 83 per cent of revenue in

the average OECD nation is derived from four major taxes: income tax,

social security, VAT and sales, and excise, which together account for

32.O per cent of the national product. The four major taxes produce more

than nine-tenths of the revenue in Sweden, Finland, Denmark, Belgium

and Germany. The degree of concentration is not an artefact of the level of

aggregation. When the 137 IMF tax categories employed in France are

examined, four-income tax, employers and employees social security, and

General Value Added Tax - account for 79 per cent of total tax revenue

(IMF, I983: 284).

The complement of a few taxes raising a large amount of money is that a

large number of taxes account for a very limited fraction of revenue.

Corporation tax, property tax, wealth and estate tax, customs, payroll,

and a miscellany of unclassifiable taxes altogether contribute only

one-sixth of total revenue in the average OECD nation.

Theories of tax-specific similarities hypothesize that a given tax has

much the same properties across national boundaries; it should therefore

raise much the same proportion of total revenue and make much the same

claim on the national product in every OECD nation. The cross-national

coefficient of variation for a specific tax should thus be substantially

less than I.29, the coefficient of variation in the contribution of taxes to a

nation's revenue.

There is a degree of homogeneity in the revenue yield of major taxes in

This content downloaded from

196.191.248.6 on Fri, 06 May 20hu, 01 Jan 1976 12:34:56 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

302 Richard Rose

OECD nations (Table 3). Income tax, in most nations the principal

source of revenue, shows the lowest coefficient of variation for its share of

total revenue (0.35), and the national product (0.38). The taxes ranking

second and third in relative homogeneity - VAT and sales, and excise -

are also major taxes. The two taxes next in relative homogeneity,

corporation tax and social security, are also above-average in the

proportion of total revenue raised. The more money a tax claims, the less

variation it shows cross-nationally.7

TABLE 3. Testing for homogeneity in types of taxes, I955-I982

As % National Tax System As % GDP

Ig5sa i965 1982 I955a 1965 1982

(coefficient of variation) (coefficient of variation)

Major Taxes

Income tax .40 .38 .35 .40 .47 .38

Social Security .73 .64 .6o .82 .7 I .63

VAT and Sales .74 .53 .42 .79 .63 .49

Excise ( 35) 40 52 (-32)b .41 .53

Minor taxes

Corporation .43 .52 .56 .43 .42 .6 i

Property .95 I.I0 I . I 7 .92 I.IO i.i8

Wealth & estate .43 .43 .65 .45 .35 .62

Customs (n.a.) .87 .91 (n.a.) .8o .87

Payroll 2.28 2.35 1I73 2.38 2.45 1.75

Other I.87 2.02 I .57 I .78 I.7I 1.52

a No data available for France, Luxembourg and Spain.

b 1955 data combined for excise and use and customs.

The taxes that vary most from country to country are those that

contribute least to the national revenue, payroll tax, otherwise unclassi-

fiable taxes, customs, and property taxes. The mean coefficient of

variation of minor taxes' contribution to the national tax system is i. i o,

more than twice that for the four major taxes, 0.47. The mean

coefficient of variation for the minor taxes' claim on the national prod

is I.o9; for the four major taxes, it is less than half, 0.5I.

Insofar as a specific type of tax has generic attributes, it should change

in the same direction regardless of the national context. Only if this

occurs, can homogeneity persist. The simplest test is how a given tax

changes its claim on the national product from I955 to I982. By that

criterion, only two major taxes - income tax, and VAT and sales - can

claim to be completely consistent across national boundaries, going up in

every OECD nation. In the past quarter-century, social security has also

increased nearly everywhere. The fourth major tax, excise, takes an

increasing share of the national product in eight countries, and a

This content downloaded from

196.191.248.6 on Fri, 06 May 2022 17:05:39 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

Maximizing Tax Revenue While Minimizing Political Costs 303

decreasing share in nine. Among minor taxes, there is a general tendency

for their share of the national product to decline, but this tendency is

limited in extent. There is consistent decline in customs, but for each of the

other taxes there are changes in opposite directions (Table 4).

A rise in the percentage contribution that some taxes make to national

revenue will necessarily cause a fall in the share of others. Only two major

taxes - income tax and social security - consistently increase their

contribution to total revenue; excise taxes show a tendency to decline; and

the share of VAT and sales tax increases in half the countries and declines

in the other half (Table 4). The share of minor taxes consistently declines;

this is most marked with customs and property taxes.

TABLE 4. The direction of change in types of tax across nations, I955-82

As % Nat'l Tax gystema As % GDPb

Type of Tax Up Down Up Down

Major

Income tax 14 3 I7 0

Social security I4 2 15 I

VAT & Sales 8 8 o5 0

Excisec 4 I3 8 9

Minor

Corporation 4 I 3 6 i i

Property I I I 6 5

Wealth & estate 2 15 4 12

Customsc O i6 2 I4

Payroll 3 2 4 I

Other 1 4 0 3

a Excludes cases in which a tax contributed less than one per cent of a nation's total tax revenue in

both I955 and 1982, and three countries for which no data was available in I955.

b Excludes cases in which a tax claimed less than 0.5 per cent of a country's GDP in both

I955 and I982.

Figures for customs and excise categories are for the I965-82 period.

Another way to test whether or not a specific tax is becoming more

homogeneous is to compare the coefficient of variation at three different

points of time, I955, I965 and I982. Insofar as the coefficient is declining

in size, then there is a tendency toward convergence in the use of specific

types of tax.

Here again patterns of change differ between major and minor taxes

(Table 3). For income tax, social security, and VAT and sales, the

coefficient of variation has fallen on both measures. By contrast, for each

of the minor taxes the coefficient of variation has increased or remained

very high. Whilst nations do not converge toward the Standard Tax

System, three major taxes - income taxes, social security and VAT - have

This content downloaded from

196.191.248.6 on Fri, 06 May 2022 17:05:39 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

304 Richard Rose

consistently and increasingly shown homogeneity in their contribution to

national revenue and their claim on the national product.

From a policymaker's perspective, consistency within a nation is more

important than cross-national commonality in a specific tax. Within a

national tax system, consistency of revenue is fundamental, because it is

revenue that determines the extent to which expenditure can be financed

without raising taxes or borrowing more. If budget-makers can be

confident in estimating tax revenue from year to year, then they can

budget incrementally, whereas if revenue is unstable, as in poor countries,

then budgeting is much more difficult (Caiden and Wildavsky, I 980; Rose

and Page, i982).

The consistency of a series of annual observations of revenue yields for

each tax can be measured by a least squares regression line (see Rose and

Karran, I983: 39ff). Since annual tax data is available from OECD only

since i 965, the trend analysis must start then. Goodness of fit (that is, an r2

value of .50 or greater) is here regarded as evidence of consistency in a

tax's share of the national tax system or of the national product. A

consistent trend may be up (here defined as an increase of greater than 25

per cent from the base); down (a decrease of greater than 25 per cent); or

stable (no more than plus/minus 25 per cent change). Irregular patterns in

tax revenues (an r2 of less than .50) can be of two different sorts. A cycle is a

non-linear pattern of change producing little net change, because of

fluctuations up and down (a cumulative change of no more than 25 per

cent from the base). Alternatively, when cumulative change up or down is

substantial (greater than a 25 per cent alteration), then the pattern is

unstable, being large in scale but irregular in pattern.

When patterns of change in particular taxes are examined across

OECD nations, few taxes consistently follow the same course. Each tax

normally registers a change in four or five different ways (Table 5). Only

two taxes - income tax and social security - show the same pattern of

change in as many as three-quarters of the countries examined; both

consistently increase. Three-fifths of all changes in taxes are consistent,

but a consistent trend may be down or flat instead of up.

From the point of view of national policymakers, consistency in the

principal sources of revenue, whether the trend be up, down or flat, is

more important than cross-national consistency within analytic categor-

ies. When national tax systems are examined, on average, 7 I per cent of

revenue comes from taxes that are predictably consistent within a nation

in their claim on the national product. In six of 20 nations, more than

nine-tenths of revenue comes from consistent taxes. Aggregate revenue as

a proportion of GDP is even more consistent; the goodness of fit (r2) for

total revenue averages .79. Taxes differ from each other in their pattern of

change, but there is sufficient consistency among major sources of revenue

This content downloaded from

196.191.248.6 on Fri, 06 May 2022 17:05:39 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

Maximizing Tax Revenue While Minimizing Political Costs 305

TABLE 5. Patterns of change in taxes' share of the national product 1965-82

Consistenta Not Consistent

Steady Stable Steady Cyclicalb Unstablec

increase decrease

Major

Income tax I6 I O 3 0

Social security 14 I 0 2 I

VAT & Sales 10 2 0 7 I

Excise I 5 4 7 3

Minor

Corporation 2 I 3 7 7

Property 2 I 5 7 3

Wealth & estate 2 2 5 6 5

Customs I I I3 3 2

Total N 48 14 30 42 22

(Trends calculated only for taxes accounting for at least 0.5 per cent of GDP in both I965

and 1982).

a Consistent change: r2 trend line fit of .5o or greater. Steady increase if change is cumulatively

greater than 25 per cent, Decrease if down more than 25 per cent, and Stable if ? 25 per cent

of base.

b Cyclical pattern: r2 is less than .50 and cumulative change is less than ? 25 per cent of base.

c Unstable: r2 is less than .50, and the cumulative change is more than ? 25 per cent of base.

for budget-makers to be reasonably confident about a continuing flow of

revenue.

Consistency in many revenue sources does not mean that revenue-

raising is completely routine. The consistent decline in some taxes

requires an increase in the yield from others in order to maintain a steady

stream of aggregate revenue. The question thus arises: What kind of

theory would best describe the way in which governments already raising

large sums in taxation in I955 have increased revenues substantially in

the years since?

4. Minimizing political costs through taxation by inertia

The government's need for revenue is not a question of political values or

political choice; in the first instance it is a given. A condition of taking

office is that a politician swears to uphold the law, tax code and all. A new

government also inherits major programmes of the mixed economy

welfare state, such as pensions, health care and education (Rose, I985).

Most of these programmes are popularly regarded as 'good' goods, since

everybody can expect to benefit from them. Since public programmes are

big, the need for tax revenue is big too. In political as well as economic

terms, taxes are the cost of providing the benefits of government.

This content downloaded from

196.191.248.6 on Fri, 06 May 2022 17:05:39 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

306 Richard Rose

The first problem facing politicians today is how to minimize political

costs while maximizing tax revenue. The object is damage limitation or

blame-sharing (Kavanagh, I980). Twenty years ago many economists

confidently advised that tax revenue could be increased almost effortlessly

through Keynesian policies that would increase the national product, tax

revenue, public expenditure, and take-home pay. Today there is no longer

general confidence that it is practicable to have 'policy without pain'

(Heclo, 198I: 397; see also Rose and Peters, I978). Politicians elected

on a tax-cutting programme feel the pain most, for even if a few margin-

al tax cuts are delivered, in an era of big government taxes remain

big.

Non-decisionmaking is preferred to decision-making in taxation.8 The inertia of

established tax laws and administration continues as long as elected

officeholders do nothing to mount an equal force to stop or redirect it.Just

as uncontrollable spending commitments continue, whatever the wishes

of the government of the day (Rose and Karran, I 984), so too the revenue

to finance these programmes is provided by the inertia of tax laws and

administration. Whether or not the existing tax structure is optimal from

an economist's point of view, it is usually optimal from a politician's point

of view. Doing nothing enables a politician to avoid identification with

proposals to levy new taxes or increase the rates of existing taxes. If

keeping out of trouble is a basic law of politics, then not making decisions

is one way to avoid trouble - in the short run at least. Introducing new

taxes or repealing established taxes cause political controversy, and

uncertainty about revenue flows.

The inertia of established laws minimizes political costs. Laws on the

statute book persist from year to year; the great majority of revenue laws

are old laws (cf. Rose, I 984a). Contemporary governments are committed

to enforce a great repertoire of tax legislation that obligates officials to

collect and citizens to pay income tax, social security, sales, excise wealth,

property, and other taxes. The statute book provides the legal authority

for taxation, identifies the economic activities subject to tax, and the

specific rate to be applied to that base. It also leaves the responsibility for

enacting tax legislation with past governments.

By sustaining familiar taxes, inertia tends to make taxation politically

acceptable, or at least less unacceptable. New tax proposals can induce

anxiety by their unfamiliarity, and novel tax proposals are uncertain of

popular acceptance or effective implementation. By definition, an existing

tax law has been approved by the legislature and the executive, and it has

also been implemented by administrators. Familiarity increases accept-

ance, if only by a process of resignation. For example, British taxpayers

are so inured to high levels of taxation that six years out of seven a majority

expect taxes to rise further (Gallup Poll, I985: 28-29).

This content downloaded from

196.191.248.6 on Fri, 06 May 2022 17:05:39 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

Maximizing Tax Revenue While Minimizing Political Costs 307

The administrative apparatus needed to collect revenue is also

sustained by the inertia of government organization. Tax officials can

annually collect a predictable amount of revenue at a known cost in

personnel and taxpayer friction; the imperfections of tax administration

are unlikely to differ much from those of other administrative activities of

government (cf. Hood, 1976). Moreover, where resistance is encountered

in collecting revenue from one type of tax, government can shift the

burden to taxes with more effective tax handles. Reliance upon

established administrative procedures greatly facilitates tax administra-

tion, and familiarity tends to produce a predictable response from

taxpayers. Countries frequently scoffed at by Anglo-Saxons for their

failure to collect large sums in income tax, such as France and Italy, are

able to collect as much or more of their total national product in taxation

as Britain and America.

Government must maintain a predictably consistent cash flow because

it is continuously spending billions of its national currency. The inertia of

established taxes makes revenue flows much more predictable. This is

particularly important for taxes that provide the major portion of national

revenue. The two taxes that together usually account for more than half a

nation's total revenue - income tax and social security - are also the two

taxes that almost invariably produce a consistent stream of revenue

(Table 5).

Taxation by inertia explains why OECD nations rely upon a wide

variety of different tax structures to raise high levels of aggregate revenue,

and why there is no convergence between national tax systems. At any

point in time, policymakers are risk-averse. Because they do not want to

forfeit a substantial amount of tax revenue or cut programme expenditure,

politicians refrain from repealing established taxes. Nor do they wish to

introduce new taxes with a substantial impact upon revenue because,

whatever their net effect, the gross cost of a new tax is expected to have a

large and unfavourable impact upon the electorate. In the short term the

logic of the situation is clear: do nothing.

Notwithstanding the considerable furore about high taxes and govern-

ment expenditure in the I970s, political decisions to alter tax laws

normally have a limited revenue impact. For example, the highly

publicized approval of Proposition I 3 in California in I 978 affected only a

limited portion of a single revenue source of one taxing authority in one

state of the United States. The I98I Reagan tax changes have generated

larger marginal changes in revenue, but from a long-term perspective,

they are very much the exception (Witte, I985), and were based upon

supply-side arguments unlikely to have much credibility in future (cf.

Stein, I984; Greider, I982).

The immediate problem facing any government is not that of designing

This content downloaded from

196.191.248.6 on Fri, 06 May 2022 17:05:39 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

308 Richard Rose

a tax structure or reforming it; it is to finance the ongoing costs of

government. In OECD nations the base cost is big; the first charge upon

the fisc is to maintain a steady flow of revenue to meet base costs. Only if

the great bulk of revenue is produced by the inertia of established tax laws

and administrative procedures can politicians begin to consider marginal

changes in taxation.

There is a fundamental disequilibrium in the market for tax reform.

There is a low demand from politicians to redesign or reform taxes and

Washington, where many such proposals are floated, is the national

capital where political institutions make comprehensive redesign least

likely. Proponents of tax reform recognize that unless five stringent

political conditions are satisfied, their goal is 'virtually impossible' (Aaron

and Galper, I985: 132). In universities there are incentives for optimal

taxation theorists to generate ideas for new tax legislation, for they gain

academic visibility by doing so (Peacock, I 98 I). But politicians prefer the

political invisibility of non-decisionmaking. Nor is tax reform popular

with the mass electorate. According to one American survey (David,

I 98 I: 21 I), less than ten per cent think that tax reform will affect their own

taxes. The status quo can mobilize strong defenders when it is attacked,

for the simple reason that it is there. Those who benefit from the existing

tax laws will not welcome the withdrawal of such exemptions, and those

who fear that new legislation will be unfavourable to their interests will

also oppose change.9

A theory of taxation by inertia must do more than explain the

maintenance of a steady flow of revenue. It must also demonstrate how the

inertia force of existing laws can provide a steady increase in revenue. Of

the three terms in the public policy model of taxation, the increase cannot

come from raising the rates or expanding the base, for that would require

positive action by politicians. Administration also requires positive

government action, and tends to be difficult to alter in the short term.

Changes in economic activity are thus the principal potential source for

change in total tax revenue.

Changes in the economy affect revenue by altering the base of a

particular tax. In the era under review here, two changes have been of

greatest importance, economic growth and inflation. By contrast with

expenditure, which may be discussed in volume (or so-called 'real') terms

unrelated to the money sums paying for public goods and services, taxes

are levied in actual current money (Clarke, 1973: 159). Inflation can

increase the value of the tax base, thus generating more actual revenue

without any action by policymakers to change the law. In addition, the

expansion of the economy can increase the economic base. In most years

the economy's tax base expands because of both inflation and economic

growth.

This content downloaded from

196.191.248.6 on Fri, 06 May 2022 17:05:39 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

Maximizing Tax Revenue While Minimizing Political Costs 309

But the structure of a nation's economy is no more a unidimensional

entity that changes uniformly in all its parts than is a national tax system.

Different parts of an economy are differentially affected by economic

growth. For example, increased capital investment can reduce the yield

from social security taxes, if fewer workers are required to produce a given

volume of goods. Inflation also effects parts of the economy differentially.

In a dynamic economy invariant features of tax laws have special

significance. An excise tax denominated in fixed-money terms, such as a

tobacco tax, will reduce its relative contribution to the fisc if rate and base

are unaltered, whereas revenue from progressive taxes will increase, as the

inflation of money wages increases the amount of income subject to tax at

progressively higher rates.

In order to account for changes in total tax revenues, it is necessary to

consider to what extent a tax is buoyant (that is, tends to generate

disproportionately more revenue than that accounted for by the rate of

economic growth and inflation) or not buoyant (that is, it increases

relatively less than the rate of economic growth and inflation).

The presence or absence of buoyancy in tax revenue is of crucial

political importance. Without buoyancy, politicians would have to

become identified with positive initiatives to raise taxes, actions that

would be politically unpopular. By contrast, if revenue is buoyant, then a

government's total tax revenue can increase without any public decision

on its part.'0

Of the nine taxes reviewed in this paper, one would be expected to be

unusually buoyant, the progressive income tax, and three would be

expected to be relataively buoyant - VAT and sales taxes, social security

tax, and corporation tax- because they are denominated as percentages of

cash flows. Payroll tax, wealth tax, and property tax would be buoyant

only insofar as there was provision for an annual revaluation of the base of

the tax, and the tax rate was a percentage of the base. Two taxes, customs

and excise, would be expected not to be buoyant, since they are

denominated in fixed-money rates unlikely to be raised annually to keep

up with inflation and growth.

The buoyancy of a tax's contribution to total national revenue, i.e., its

propensity to rise faster than the increase in the national product due to

the conjoint effect of economic growth and inlation, can be indicated by

dividing the percentage increase in the current-money revenue yield of a

given tax by the percentage increase in the current-money value of the

gross domestic product during the same period (cf. Aguirre et al. I 98 I: 3).

If the percentage increase is the same for both terms, then the value will be

I.00; the tax will be neither buoyant nor depressed. If the resulting ratio is

greater than I.00, then the tax will be relatively buoyant, and if less than

I.00, it will be depressed relative to the economy as a whole. Comparing

This content downloaded from

196.191.248.6 on Fri, 06 May 2022 17:05:39 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

310 Richard Rose

individual taxes with the change in the money value of the total national

product controls for the effects of both economic growth and inflation.

Within every OECD nation, tax revenue has grown more rapidly than

nominal income since I 955. However, the general tendency for most taxes

to grow faster than nominal national income is not true of all taxes. Even

though all taxes are influenced by the same rate of national inflation and

economic growth, there is a high degree of variation in the buoyancy of

taxes within a nation."'

TABLE 6. The differential buoyancy of tax types,

1955-I982

Buoyancy ratio across I7 countriesa

Tax Type Mean Stand. Dev. Coeff. variation

Major taxes

Income tax 2.34 .90 .39

Social security 4.54 6.56 I.44

VAT & Sales I.58 .55 35

Excise (I965-82) 1.00 .40 .40

Minor taxes

Corporation I.1o .73 .66

Customs (I965-82) .45 .37 .83

Wealth & estate .83 .54 .65

Property .97 .57 .58

Payroll .67 .96 I.42

Unclassified .69 1.40 2.03

Total Taxes I .58 0.28 .I8

a Extreme increases resulting from the introduction of VAT in

Ireland and a payroll tax in Sweden are excluded from the

calculation of means.

Specific taxes tend to vary greatly in their buoyancy ratios. Two taxes -

income tax (mean buoyancy ratio of 2.34) and social security (4.54) - are

well above the buoyancy ratio for total taxation, and VAT and sales (I .58)

is equal to it (Table 6). The other major tax, excise, and one minor tax,

corporation, have also tended to be more buoyant than the nominal

income of society. By contrast, five minor tax categories have been less

buoyant than national economies. There are cross-national differences in

the degree of buoyancy of specific types of taxes. The coefficients of

variation tend to be higher for minor taxes, and excepting social security

taxes,'2 there is little cross-national variation in the buoyancy of major

taxes.

Of primary political importance is the fact that the three taxes r

highest with respect to buoyancy - income, social security and VAT and

This content downloaded from

196.191.248.6 on Fri, 06 May 2022 17:05:39 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

Maximizing Tax Revenue While Minimizing Political Costs 3I I

sales - were already among the most important taxes in I 955. When a few

major taxes grow faster than the economy and most taxes grow more

slowly than the economy, then revenue will increasingly be concentrated

upon a very few taxes of primary political importance. Policymakers can

collect more revenue from fewer taxes by relying upon the buoyancy of

taxes placed on the statute books long ago.

Concentration on revenue-raising from income tax, social security, and

VAT and sales has increased greatly from I 955 to I 982 (Table 7). In 1955,

these three major taxes on average contributed only 51 per cent of total tax

revenue, and the pattern was similar among all OECD countries. More

than a quarter-century of economic growth and inflation has increased the

contribution of buoyant taxes to an average of 7 I per cent of total taxation,

and has done so consistently among OECD nations. As the fisc's need for

money has increased, it has been able to rely more and more upon a few

buoyant taxes already raising large amounts of revenue.

The buoyancy of major taxes has been an important condition for

increasing the capacity of governments to mobilize more and more

TABLE 7. The increasing concentration of tax revenue, 1955-1982

Degree of Concentrationa

National Tax System Mobilization of GDPa

1955 1982 Increase I955 1982 Increase

% % % % ~~~~% %

Belgium 75 83 8 I8 39 21

Sweden 55 82 26 14 41 27

Italy 52 82 29 i6 31 15

Germany 64 8I I8 20 30 I I

Netherlands 59 8I 22 15 37 2I

Denmark 46 78 32 II 35 24

Switzerland 6i 76 I5 12 24 I2

Austria 6o 76 15 I8 3I I3

Finland 58 73 15 I6 27 I I

New Zealand 50 72 22 I4 24 II

USA 47 72 25 I I 22 I I

Norway 58 65 7 i6 3I 15

Ireland 2 I 64 43 5 25 2 I

UK 4I 59 I8 12 23 II

Canada 40 58 i8 9 20 10

Japan 36 56 20 6 15 9

Australia 42 52 I0 10 I6 6

Mean 51 7I -'20 13 28 I5

Std. Dev. I3 10 4 7

Coeff Var. 0.25 0.14 0.32 0.27

a Percent that three principal buoyant taxes - income tax, social security, and VAT and Sales -

contribute to the National Tax System and claim from the Gross Domestic Product respectively.

Statistical calculations based on figures before rounding off.

This content downloaded from

196.191.248.6 on Fri, 06 May 2022 17:05:39 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

3I 2 Richard Rose

revenue. Whereas in 1955 income tax, social security and VAT and sales

on average claimed 13 per cent of the national product, by I 982 their claims

more than doubled, accounting for 28 per cent of the national product.

The extra money generated by these buoyant taxes has not only led to a big

gross increase in revenue, but also helped to replace revenue lost by

taxes that have failed to grow as much as a buoyant economy.

Non-decisionmaking is relative not absolute; although inertia forces

keep boosting revenue, there is no hidden-hand mechanism assuring that

revenue will always rise pari passu with expenditure claims. And

policymakers also want to intervene to make changes in taxation at the

margin. Three different forms of political intervention can be identified:

borrowing, altering the tax rate and base, or repealing laws or adopting

new tax laws.'3 Whilst each is a subject for political debate, if only because

they are the delimited areas within which choices can be made, their

impact upon total revenus is marginal.

Borrowing. When inertia processes of taxation fail to generate a

sufficient revenue to meet expected expenditure, governments can resort

to borrowing to fund the deficit. This is readily explained by a

non-decisionmaking model, for borrowing avoids the need to make a

decision about matters that are both visible and likely to be politically

unpopular, such as increasing taxes or cutting public expenditure.

Whereas conventional Keynesian economic prescriptions justify borrow-

ing as a cyclical and therefore occasional measure to stimulate the

economy, non-decisionmaking treats borrowing as a continuously

desirable political strategy.

Since the slowing down of rates of economic growth with the world

recession of the early 1970S, governments have relied more and more upon

borrowing to finance revenue shortfalls. (Price and Chouraqui, 1983;

Saunders and Klau, I985: Tables I, I9). National tolerance for deficit

finance tends to be variable; in I982 financial deficits ran as high as 13.7

per cent of GDP in Ireland and I I.9 per cent in Italy, three to five times the

level causing anxieties in Britain and America. Whatever the tolerance,

borrowing has its limits; the cumulative effect of higher deficits is an

increase in debt interest payments. This cost is now substantially greater

than public expenditure on defence in OECD nations, and it is projected

to catch up with spending on health or education (OECD, I985).

Altering the tax rate or tax base. Because such changes only require

amendments to existing statutes, they involve far fewer difficulties than

the enactment of new tax statutes. Administrative procedures are

unaltered, except for the revision of published tax tables, forms and

procedures. The revenue yield from an altered rate is almost as

predictable as the yield from an unaltered rate. Political criticism of

altering the rate upwards can be met with the argument that the revenue is

This content downloaded from

196.191.248.6 on Fri, 06 May 2022 17:05:39 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

Maximizing Tax Revenue While Minimizing Political Costs 313

needed to meet increased expenditure, and a challenge to critics to

propose an alternative tax yielding an equivalent increase in revenue, or

programme cuts making the increase unnecessary. Proposals to reduce

the rate of a tax are difficult to oppose politically, especially if introduced

shortly before a general election.

In an era of inflation, amending the tax laws is inevitable. Inflation

destabilizes taxation by generating too much (sic) revenue. Not only does

it increase the current money yield but also it brings far more people into

the tax net, and pushes people in middle-income brackets into progres-

sively higher tax brackets. On a priori political grounds, one might expect

politicians to respond by annually cutting tax rates or raising tax

exemptions in current money terms, while actually securing some

increase in revenue due to inflation and growth. Headlines would speak of

tax cuts, while the fine print of the budget kept revenue rising.

In fact, politicians in Western nations have usually sought to remove

from their hands the annual responsibility for such decisions, indexing

income tax systems by writing into legislation automatic increases in tax

allowances affecting marginal tax rates. Once a system of indexing is part

of a tax statute, then tax changes will occur without any decision being

taken by politicians of the day. Thus, politicians cannot claim any

political credit for cutting (sic) tax rates. In an inflationary era, proposals

to reduce rates are not perceived as a benefit, but rather as a stimulus to a

larger debate about who is to blame for inflation, and about what taxes

ought to be. Politicians have preferred to deny themselves credit for

adjusting tax rates in order to avoid such annual controversies. Inasmuch

as indexing systems are almost inevitably imperfect, this non-decision-

making approach reduces but does not destroy the buoyancy of

principal revenue sources (Tanzi, I 980).

Altering the tax base is another means of active political intervention in

the revenue-raising process. At any given point in time, statutes define

which economic activities are liable to taxation (the tax base) and which

are not (tax allowances, or more controversially, tax expenditures; cf.

OECD I984a, Surrey and McDaniel, I985).

The exemption of a portion of income from taxation is as old as the

income tax, and allowance for the deduction of mortgage-interest

payments to home-owners is also long established. Proposals to reform or

abolish tax expenditures need to mobilize great political force in order to

overcome the inertia force of statutory definitions of the tax base. The

substantial academic criticism of a variety of tax allowances has not

generated sufficient counterforce to repeal existing statutes (see Wildav-

sky, I985). Even the historically extreme tax revision proposals circulat-

ing in Washington in 1985 propose a reduction of tax allowances to

broaden the tax base, but not the abolition of such electorally popular

This content downloaded from

196.191.248.6 on Fri, 06 May 2022 17:05:39 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

314 Richard Rose

concessions as tax relief for mortgages. In effect 'reform' is about a tax

swap, reducing tax expenditures in returning for reducing tax rates, so

that the revenue effect in aggregate is meant to be nil.

The annual budget of the British Chancellor of the Exchequer provides

an unusual opportunity to test the extent to which there is scope for

politicians to choose to alter revenue yields of taxes, for the Chancellor

publishes the expected impact on revenue of each change proposed, and

Parliament almost invariably endorses the Chancellor's proposals. Thus,

the British government can effectively choose how much or how little it