Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Buddhist Connections in The Indian Ocean

Uploaded by

gygyOriginal Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Buddhist Connections in The Indian Ocean

Uploaded by

gygyCopyright:

Available Formats

Journal of the Economic and

Social History of the Orient 58 (�0�5) �37-�66

brill.com/jesh

Buddhist Connections in the Indian Ocean:

Changes in Monastic Mobility, 1000-1500

Anne M. Blackburn

Cornell University

amb242@cornell.edu

Abstract

Since the nineteenth century, Buddhists residing in the present-day nations of

Myanmar, Thailand, and Sri Lanka have thought of themselves as participants in a

shared southern Asian Buddhist world characterized by a long and continuous history

of integration across the Bay of Bengal region, dating at least to the third century BCE

reign of the Indic King Asoka. Recently, scholars of Buddhism and historians of the

region have begun to develop a more historically variegated account of Buddhism in

South and Southeast Asia, using epigraphic, art historical, and archaeological evi-

dence, as well as new interpretations of Buddhist chronicle texts.1 This paper examines

* I am grateful to the anonymous reviewers at JESHO for their incisive and helpful comments

during the preparation of this article and to Dr. Paolo Sartori for his dedicated editorial

guidance. Early versions of some of the material discussed here were presented at the Asia

Research Institute of the National University of Singapore, the Department of History at

the National University of Singapore, the Institute for Comparative Modernities at Cornell

University, and Stanford University’s Ho Center for Buddhist Studies. Research contribut-

ing to this article was made possible by a Senior Research Fellowship at the Asia Research

Institute of the National University of Singapore. During that period I benefited from conver-

sations with many colleagues. I offer special thanks to Prasenjit Duara, Michael Feener, Geoff

Wade, Alexey Kirichenko, and Christian Lammerts.

1 “Chronicles” is a term of art, used here to refer collectively to texts composed in Pāli or local

literary vernacular languages derived, directly or indirectly, from the Pāli-language vaṃsa

genre popularized in Laṅkā (now Sri Lanka) during the first millennium CE. In the Buddhist

world, vaṃsas are texts that celebrate the lineage of a place, person, polity, community, and/

or object, typically in relation to Buddhist monastic institutions and royal families. Shared

access, direct or indirect, to Mahāvaṃsa, an early sixth-century Pāli-language text from the

kingdom of Anurādhapura in Laṅkā, led to the popularization of a written style celebrating

monastic-cum-royal institutional developments in the Buddhist world (sāsana).

© koninklijke brill nv, leiden, ���5 | doi �0.��63/�5685�09-��34�374

238 Blackburn

three historical episodes in the eleventh- to fifteenth-century history of Sri Lankan-

Southeast Asian Buddhist connections attested by epigraphic and Buddhist chronicle

accounts. These indicate changes in regional Buddhist monastic connectivity during

the period 1000-1500, which were due to new patterns of mobility related to changing

conditions of trade and to an altered political ecosystem in maritime southern Asia.

Keywords

Buddhism – Buddhist chronicles – Buddhist networks – Indian Ocean – Sri Lanka

Introduction

Writing from self-imposed exile in Laṅkā in 1897, the Siamese monk-prince

Prisdang (Jinavāravaṃsa), formerly a high-level envoy from Bangkok to many

European capitals, celebrated the forthcoming visit of the Siamese king

Chulalongkorn to the island colony as an opportunity to renew long-standing

connections of Buddhist fraternity and amity among the “nations” of Ceylon,

Burma, and Siam. Prisdang sought to make King Chulalongkorn the pro-

tector of Buddhism in the region and to subsume all Buddhist monks from

these three locations in an ecclesiastical council administered from Bangkok

(Blackburn 2010: 167-86). Prisdang’s vision of enduring connections between

Laṅkā, Burma, and Siam would have come as no surprise to most of his monas-

tic colleagues in Laṅkā and Southeast Asia, as the nineteenth century was a

period of intense communication among Buddhist monks in Laṅkā, Burma,

and Siam, as they sought to address intellectual, political, and institutional

challenges to Buddhism linked to French and British colonial projects in the

region (Reynolds 1973; Malalgoda 1976; Blackburn 2010). The Buddhists of

Prisdang’s day studied Buddhist textual reports of historical trans-regional

connection, seeking models and precedents for nineteenth-century activities.

While Prisdang and his monastic colleagues often celebrated unbroken

Buddhist connections in the Indian Ocean region in a manner that empha-

sized continuities with the era of the third-century BCE King Asoka, scholars

of Buddhism and historians of the region have lately begun to forge a more

detailed and temporally sensitive account of Buddhist mobility and religio-

cultural exchange and influence across South and Southeast Asian lands. This

article is intended as a contribution to our understanding of Buddhist mobil-

ity and trans-regional Buddhist institution-building, focusing on the period

between 1000 and 1500. It examines three episodes of trans-regional Buddhist

jesho 58 (2015) 237-266

Buddhist Connections In The Indian Ocean 239

activity recounted in epigraphic and/or Buddhist chronicle sources: the

importation of Buddhist bhikkhus (fully ordained monks) from Ramañña to

Poḷonnāruva, in Laṅkā, during the late eleventh century, the pilgrimage jour-

ney of the Sukhothai Buddhist monk Si Satha to Laṅkā in the early fourteenth

century, and the embassy sent by Bago’s King Dhammazedi to Koṭṭē in Laṅkā in

the late fifteenth century to secure a new monastic higher-ordination lineage

for bhikkhus in Bago. These events are all instances of trans-regional southern2

Asian Buddhist connection, involving ties between Laṅkā and Southeast Asian

Buddhist locations. They might be said to support monk-prince Prisdang’s

invocation of a regional Buddhist history of continuous fraternity and support.

Examined more closely, however, they reveal significant differences, including

the scale of activity, the geographic locus of Buddhist authority in the transac-

tion, and the routes and technologies involved in Buddhist travel. This paper

argues that these three episodes of Buddhist mobility across oceanic space and

the borders of polity reflect changes in the trading and political ecosystem of the

Indian Ocean in the first half of the second millennium CE, as well as the gradual

crystallization of new forms of royal and monastic Buddhist institution-building

that relied on trans-regional communication and the transmission of Buddhist

texts, ideas, and persons. Attending to them closely helps us envision in a more

nuanced manner a dynamic history of Buddhist connection during this period.

1 Bhikkhus from Ramañña

According to Cūlavaṃsa chapters composed in the thirteenth century,3 King

Vijayabāhu I (r. 1058-1114), ruling from Poḷonnāruva after defeating Cōla forces

in the mid-1070s, restored Laṅkā’s Buddhist monastic community by bringing

fully ordained Buddhist monks from Ramañña to recommence a bhikkhu lin-

eage within the island.

2 In the pages that follow, I generally use the term “southern Asia” when referring to the geo-

graphic space encompassing Laṅkā, the southern Indian mainland, and locations typically

referred to as falling within ‘Southeast Asia.’ The mobile persons and communities investi-

gated here understood themselves to function within a broad trans-regional geography that

transcends the boundaries of current academic area studies. The frameworks of “South Asia”

and “Southeast Asia” are of recent vintage, established during the Cold War. Relying on those

frameworks and the anachronistic distinction between them makes it more difficult to rec-

ognize Laṅkā’s historical participation within networks and processes traversing the wider

region.

3 Cūlavaṃsa extends the earlier Mahāvaṃsa chronicle and was composed serially. The chap-

ters describing Vijayabāhu I are in the section composed during the thirteenth century.

jesho 58 (2015) 237-266

240 Blackburn

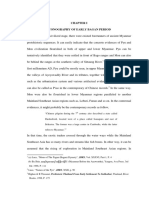

Ava

Bagan

Kengtung

A Bay

G

LIN of Chiang Mai

KA Bengal Bago

BURMA Sukhothai

DELTA

Phitsanulok

T Pathein Mottama

AS

D EL CO

Ayutthaya

Dawai

MA

Kovalam

N

Tennassarim

COROMA

CHAMPA

LAB

A

Nagore

RC

Gulf

Nāgapattanam of

OA

Mantai Siam

ST

Trincomalee

Nakhon Si Thammarat

Anurādhapura Poḷonnāruva

Koṭṭē

LANKA

St

ra

it

of

M Melaka

el

ak

a

0 500 mi

0 500 km

Map of the Bay of Bengal and the Indian Ocean, 1000-1500. We gratefully acknowledge the

assistance of Michael Hradesky, Staff Cartographer, Ball State University.

As there not enough bhikkhus to fulfill the quorum for higher ordination

and other monastic rituals, focused on the stability of the sāsana [Buddhist

tradition], the Ruler of Men had messengers with presents sent to the

realm of Ramañña, into the presence of his friend King Anuruddha. From

there he had brought bhikkhus characterized by moral discipline and

other virtues, with a complete knowledge of the Three Piṭakas [Buddhist

“scriptures”], who were acknowledged as senior monks [theras]. Having

had them reverenced with costly gifts, the Ruler of Men had many acts of

first and final monastic ordination performed (Cūlavaṃsa 60: 4-7).4

4 I have revised the translation in Geiger (1992). This is also reported in Pūjavaliya, Rājāvaliya,

and Nikāya Saṅgrahaya. See also EZ 2.40.

jesho 58 (2015) 237-266

Buddhist Connections In The Indian Ocean 241

Seen from the perspective of Laṅkā’s later Kandyan and colonial periods

(seventeenth-twentieth centuries), characterized by a large volume of ordination

traffic between Kandy, Arakan, Bago, Ayutthaya, Bangkok, Amarapura, and

Mandalay (Malalgoda 1976; Blackburn 2001, 2010), Vijayabāhu I’s overtures to

Ramañña appear unremarkable.

Vijayabāhu I’s importation of bhikkhus from Ramañña is, however, the first

introduction of non-Lankan monks into the island for ordination purposes

reported in Mahāvaṃsa-Cūlavaṃsa chronicles after the establishment of the

Lankan monastic order at Anurādhapura, in the time of the third-century

BCE King Asoka. Although many other instances of monastic reorganization

or renewal of royal favor to monastics are reported in these chronicles before

the eleventh-century era of Vijayabāhu I, there is no reference to ordination

through or with foreign monks after the foundational acts of Asoka’s son and

emissary Mahinda. Given the extant evidence, we cannot know with certainty

whether foreign monks were used for this purpose earlier but not celebrated as

such in royal-monastic narratives, but there is no reference to such activities in

extant inscriptions or in the Nikāya Saṅgrahaya, a Sinhala-language monastic

history composed in the late fourteenth century. At the least, the thirteenth-

century Cūlavaṃsa treatment of Vijayabāhu I’s activities marks an important

shift in Lankan literary imaginings of the Buddhist world and trans-regional

possibilities for the creation and re-creation of Buddhist institutions.

It is possible that Vijayabāhu I’s move to import bhikkhus from Ramañña

marks the start of such ordination traffic on the island. The timing supports

such a hypothesis, inasmuch as the period of Cōla rule in Laṅkā (1017-69/70)

appears to have been the first occasion in which local rulers of the island’s

Anurādhapura-based polity were displaced by foreign powers for a sustained

period. Cōla rule on the island was long enough to affect at least two genera-

tions of Buddhist monastics. Perhaps Cōla attacks on Buddhist properties—

narrated but probably sensationalized in Cūlavaṃsa (55: 20-22)—and/or the

transfer of the capital eastward from Anurādhapura to Poḷonnāruva inter-

rupted the patronage and ritual systems of Anurādhapura on a scale large

enough to render Buddhist monastic institutional and ritual life dysfunctional.

This would have required the reintroduction of Buddhist monastic ordination

lineages and practices after the end of Cōla rule. Or, perhaps Buddhist monastic

institutional and ritual life did continue on the island during the Cōla era from

the new capital at Poḷonnāruva. In that case, the move by Vijayabāhu I’s court

to introduce a bhikkhu lineage from Ramañña would have provided a means

to replace a Cōla-supported monastic administration with one loyal to the

new court. Vijayabāhu I’s choice of monks from Ramañña followed his earlier

jesho 58 (2015) 237-266

242 Blackburn

overture to the ruler of Ramañña (Cūlavaṃsa 58: 8-10).5 This is the first reference

in the Mahāvaṃsa-Cūlavaṃsa chronicles to such a diplomatic overture to a

location in what we now call Southeast Asia. The name Ramañña refers to

the southern maritime region of what is now Burma, as the same Cūlavaṃsa

author, when describing a twelfth-century Lankan raid on Kusumi (Pathein),

refers to Kusumi (Pathein) and Ukkama (Mottama) as in Ramañña (Cūlavaṃsa

76: 59-67; Epigraphia Zeylanica 3.34).6 It is possible that the Aniruddha men-

tioned in the context of imported Buddhist monks is King Anawrahta of Bagan

(r. 1044-77), given Bagan’s growing interest in southern maritime commercial

centers (Aung-Thwin 2005, 111-3; Hall 2011, 218). Bagan’s efforts to control the

delta may have been recognized at Poḷonnāruva. On the other hand, the name

may have been used to refer to a local ruler in Ramañña at that time or applied

retrospectively by the thirteenth-century author of Cūlavaṃsa on the basis

of reports of Burmese kingship circulating in the Buddhist world by the thir-

teenth century.7

The orientation of Vijayabāhu I towards Ramañña for projects Buddhist

and otherwise is more intelligible when seen in a wider Indian Ocean context.

Laṅkā’s place in the Indian Ocean trading sphere changed during the eleventh

and twelfth centuries. These changes had implications for Lankan military and

diplomatic activities and for how Buddhist persons, ideas, and practices moved

to and from the island. The eleventh century saw a sharp rise in international

trade through the Indian Ocean region, due to the coincidence of three strong,

trade-oriented polities: the Cōlas, the Song, and the Fāṭimids (e.g., Kulke 1999:

5 The Pāli passage is ambiguous, however, as to whether the “ships filled with goods including

diverse items such as camphor and sandalwood” were those carrying gifts from Vijayabāhu I

to Ramañña or received from the latter.

6 Cf. Aung-Thwin (2005: 49). Nikāya Saṅgrahaya, composed in the thirteenth century and

indebted to the Mahāvaṃsa-Cūlavaṃsa chronicle, also refers to Ramañña (in Sinhala,

Aramaṇa) when discussing Vijayabāhu I’s importation of monks (cf. Aung-Thwin (2005: 51).

Note “Kusima” in Cūlavaṃsa’s thirteenth-century Pāli usage (cf. Aung-Thwin 2005: 60).

7 It is unclear what Lankan Buddhists knew about Bagan and other Burmese and Mon sites by

this time and whether any textual accounts of Anawrahta circulated in Laṅkā. The Burmese

and Pāli chronicles from Burma that mention Anawrahta were compiled later. On the tex-

tualization of Anawrahta and the possibility that Buddhists in Bagan, northern Thailand,

and Laṅkā understood themselves as participants in a Buddhist oikoumene starting in the

eleventh century, see Goh (2007: esp. 18). There is, however, no extant textual or epigraphic

record of that understanding so early, as Goh recognizes (59). Goh’s study is a salutary

reminder that we have much to learn about pre-modern southern Asian Buddhists’ concep-

tion of the geographic and political space of Buddha sāsana (the world of Buddhism).

jesho 58 (2015) 237-266

Buddhist Connections In The Indian Ocean 243

20; Ray 1999: 37).8 Smaller ports supplied local and subregional commodities

to larger outlets. Relationships between smaller and larger ports, and the char-

acter and volume of commodity flows, were dynamic, being reconstituted in

response to changing political and military conditions and market demands.

Hall has aptly characterized this trading world as a “poly-centric networked

realm” (2010: 113).9

Competition for control of ports and goods in the region stretching from

India and Laṅkā to insular Southeast Asia resulted in rapidly shifting politico-

military arrangements (including expansion of Cōla power in the region)

and the extension of trade guilds and material forms associated with south-

ern India.10 Archaeological and inscriptional evidence from Laṅkā points to

the eleventh century as a transformative period for the island’s trans-regional

engagements, including a greater impact of the China trade. Bopearachchi

notes that Chinese coins appear in the island’s archaeological record begin-

ning in the eleventh century, including finds at the new political centers that

developed southwest of Anurādhapura and Poḷonnāruva (1996: 72-3). Evidence

from ceramics is also striking. In the late first millennium, Near Eastern and

Chinese ceramics made their way to Lankan ports (including Mantai). By the

eleventh century, however, “the former balance between Chinese and Near

Eastern ceramic goods . . . tipped sharply towards the Chinese” (Prickett-

Fernando 1990: 71).11 Cōla threats to the island from southern India and Laṅkan

courtly engagement with Ramañña are signs of the island’s changing place in

Indian Ocean circuits oriented to the expanding trans-oceanic trade between

Egypt and China. The location of the kingdom of Poḷonnāruva made it read-

ily accessible to such wider oceanic processes. It was connected by riverine

routes to the eastern port of Trincomalee, which came to dominate Lankan

trade during the eleventh century, outstripping the earlier centrality of Mantai

in the northwest (Kirabamune 1985: 101; Kirabamune 2013: 51-2; Bopearachchi

1996: 72).

8 Wade (2009) provides a valuable summary of relevant changes in Song China, includ-

ing new financial systems, internal trade regions, and demographic changes in Fujian.

See Christie (1998a: 253; 1998b: 369) for arguments that the Southeast Asian trade boom

began in the tenth century.

9 See further Abraham (1988), Karashima (2009b), Kulke (1999), Hall (2011), Jacq-

Hergoualc’h (2002), McKinnon (2011), and Wade (2009).

10 See also Sen (2003, 159, 220-4). According to Karashima (2009a), the twelfth century was

the high point of Tamil-language trade guild inscriptions extant in Sri Lanka. See also

Velupillai (1971: 46, 48; 1972: 13, 19-21).

11 See also Kanazawa (2004) and Karashima (2004).

jesho 58 (2015) 237-266

244 Blackburn

This context illuminates connections between the Poḷonnāruva court

of Vijayabāhu I and Ramañña, as well as the unprecedented reference to

trans-regional Buddhist monastic reordination in Cūlavaṃsa’s chapters on

Vijayabāhu I. The shift of the northern Lankan royal center from Anurādhapura

to Poḷonnāruva—thus providing better access to eastern trading sectors

through Trincomalee, contemporary with the expanding speed and volume

of Indian Ocean trade—greatly altered conditions in which Lankan Buddhist

institution-building and reorganization occurred. The introduction of

bhikkhus from Ramañña to Poḷonnāruva to establish a new lineage of fully

ordained Buddhist monks in Vijayabāhu I’s realm signals an early phase of

intensifying high-level Buddhist connections between the island and main-

land Southeast Asia.12

2 A Sukhothai Pilgrim to Laṅkā

The undated Sukhothai inscription no. 2 records the Buddhist devotional activ-

ities of a high-placed monk, Venerable Si Satha, born into the leading family of

the neighboring Rat kingdom, which had helped to secure Sukhothai’s inde-

pendence from Khmer control during the eleventh century. The inscription

celebrating Si Satha’s activities is remarkable; it is the only extant Sukhothai

inscription that rivals royal epigraphs in its detailed account of religious

patronage and the patron’s person. Vickery has suggested that the inscription

was intended to glorify Si Satha’s family line, in a context of regional familial

rivalry (1978, 212); the inscription readily supports this reading.13 It is also strik-

ing for reporting Si Satha’s activities in a narrative style indebted to biographies

of Buddha Gautama and to Gautama’s previous life as Bodhisattva Vessantara

(Griswold and Prasert 1992: 387-9). In inscription no. 2, Si Satha’s construction

and reconstruction of Buddhist devotional sites includes travels in the area of

Sukhothai and Si Sajjanalai, as well as Sīhala (Laṅkā).

Si Satha’s journey to Laṅkā probably occurred in the mid-fourteenth cen-

tury. Sukhothai inscription no. 2 portrays him as of the generation of King

Mahā Dhammarāja I, enthroned in 1347. According to Jinakālamālī, a monk

12 I do not discuss here the possible travels to Laṅkā from Bagan by the monk Uttarajīva

and novice Chapada during the late twelfth century. This account appears only in later

Burmese and Pāli sources and, as Win remarks (2002, esp. 88-9), there is no epigraphic

reference to a Chapada until 1240 (which may or may not refer to Uttarajīva’s co-traveler)

and the name Uttarajīva does not appear in Bagan inscriptions. Cf. Goh (2007, 42).

13 See also Griswold and Prasert (1992: 342-96) and Blackburn (2007).

jesho 58 (2015) 237-266

Buddhist Connections In The Indian Ocean 245

trained in Ramañña by a Lankan monk reached Sukhothai in the late 1330s or

early 1340s (Buddhadatta 1962: 84-5). If this is correct, it would probably have

encouraged the interest of Mahā Dhammarāja I (r. 1347-?) in Lankan Buddhist

sites, which is evident in Sukhothai inscription no. 3 (dated 1357) (Griswold

and Prasert 1992: 448-65).14 Reports of Lankan Buddhist sites and institu-

tions circulating at this time informed Si Satha’s journey to Laṅkā. Moreover,

if Si Satha was a rival to the line of King Mahā Dhammarāja I, as inscription

no. 2 suggests, a merit-making journey to Laṅkā was a natural response to the

Sukhothai politics of his time. It provided high status through a competitive

merit-making that trumped King Mahā Dhammarāja I’s indirect contact with

Lankan Buddhism, while providing an excellent reason for Si Satha’s departure

from Sukhothai.15 According to face 2 of insciption no. 11, he spent ten years

in Laṅkā.

Si Satha’s journey is a sign of changes underway in the relationship of Tai

and Lankan Buddhist institutions, as Tai Buddhists began to make direct con-

tact with Laṇkā and Lankan Buddhist institutions, rather than mediating their

contact with desirable Lankan Buddhism through southern maritime realms

such as Nakhon Si Thammarat and Mottama. Inscriptions no. 2 and 11 are our

first extant evidence in chronicles or inscriptions of direct monastic contact

between Tai regions and Laṅkā. These possibilities for direct contact continued

to develop, as we see from monastic-lineage texts composed in Chiang Mai and

Kengtung in the northern Thai and Pāli languages and celebrating the travel

of monks from Chiang Mai and Kengtung to Laṅkā in the 1420s (Buddhadatta

1962; Swearer and Premchit 1977; Sao Saimong 1971). This journey resulted in

the creation of the new monastic higher-ordination lineage associated with

Wat Pa Däng, in what is now northern Thailand and the Burmese Shan States.

The possibility of direct contact between monks from Tai territories and their

counterparts in Laṅkā created a new flexibility in the constitution and recon-

stitution of Buddhist monastic lineages and Buddhist institutions in Tai lands.

Obtaining new ordinations from the island—described as more pure and

authoritative than those existing previously on local soil—was an effective

ritual-cum-political tactic. As discussed below, during the fifteenth century Tai

monastic leaders and royal courts resorted to Lankan Buddhist monastic lin-

eages and Buddhist institutions to reorganize monastic administration in Tai

territories and to neutralize monks and temples associated with political rivals.

14 See also Coedès (1924: 84-90) and Blackburn 2007.

15 The inscriptions of Sukhothai King Mahā Dhammarāja I reveal his fascination with pro-

ducing copies of Lankan Buddhist relic sites in his realm. See Blackburn (2007).

jesho 58 (2015) 237-266

246 Blackburn

The emerging possibilities of Buddhist trans-regional connection indicated

by Si Satha’s voyage to Laṅkā should be understood in relation to changes in

the Indian Ocean trading environment during this time, as well as to shifts

in regional political formations. Trading practices and political relationships

shifted significantly during the late thirteenth and fourteenth centuries in the

area encompassing the Bay of Bengal, Laṅkā, and the Malay Peninsula. As to

Buddhist transactions between Tai territories and Laṅkā, the most important

development during this period was the gradual rise of Ayutthaya in the lower

Menam River Basin, with access to the Gulf of Siam. The early years of the four-

teenth century—the era of Si Satha and Mahā Dhammarāja I at Sukhothai—

saw the rise of the kingdom that Charnvit calls Ayodhya, a pre-Ayutthayan polity

able to control Menam River Basin traffic and access to the Gulf of Siam that

gained strength in the river basin region over several decades through trade and

effective marriage alliances with other nearby polities (Charnvit 1976: 83-6).16

Despite tensions with Sukhothai and Chiang Mai, Ayutthaya came to func-

tion as a key entrepôt for maritime Southeast Asia, linked to China, Champa,

a vast riverine network stretching north and northwest from the mouth of

the Chao Phraya River, and the Malay Peninsula. This coincided with growing

Chinese participation in trade within Southeast Asia (Heng 2009: 129), which

helped reshape port polities in the wider Malay region (213). This extension of

Ayutthaya’s power involved attacks on locations in insular and lower penin-

sular Southeast Asia during much of the fourteenth and part of the fifteenth

centuries (Baker 2003: 46-8). By the 1460s Ayutthaya “dominated the affairs of

the upper Malay Peninsula,” annexing the Tenassarim (1460s) and Dawai (1488)

regions (Hall 2011: 235; see also Heng 2009: 138). Ayutthaya’s rise altered the

routes available for Tai Buddhist traffic to Laṅkā, as the inscriptions celebrat-

ing Si Satha themselves suggest. According to face 2 of Sukhothai inscription

no. 11, Si Satha traveled to Laṅkā by way Kalinga (Orissa), Cōla lands, and the

kingdom of Malala (Griswold and Prasert 1992: 410-11); we have no information

about his first port of departure.17 He is explicitly reported to have returned via

Tennasarim (Tanāvsrī) and Ayutthaya (Ayodyā Sri Rāmadebanagara) (412-13).18

The possibility of generating wealth by dominating sectors of the Indian

Ocean trade catalyzed the reorganization of political relations also in what

16 On the maritime trading roots of Ayutthaya’s rise see also Vickery (2010: 293; 2004: 23) and

Baker (2003). On tributary missions to China from Sukhothai and Xian-guo (eventually,

Ayutthaya), see Fukami (2004: 63).

17 Griswold and Prasert locate the Malala kingdom on the Malabar coast.

18 See also Coèdes (1924: 149).

jesho 58 (2015) 237-266

Buddhist Connections In The Indian Ocean 247

is now Burma.19 Despite warfare with the southern polity of Bago through

the fourteenth and into the early fifteenth century, Bagan’s successor king-

dom, Innwa, was unable to maintain control of the delta port of Pathein at

the mouth of the Irrawaddy River on the Indian Ocean, providing access to

and from northern Burma (Fernquist 2008). Contemporary with the rise of

Ayutthaya in the fourteenth century was the emergence of Bago as a major pol-

ity in maritime Burma, which extended its reach in the south throughout the

century (Lieberman 1.126: 130-1; Fernquist 2006: esp. 50-1; Fernquist 2008: esp.

85-93, Aung-Thwin 2005: 310-11).20 The fourteenth century was thus a transfor-

mative century with respect to regional Buddhist mobility, a century charac-

terized by the final decline of Cōla power in the region and the consolidation

of two larger Buddhist-inclined polities—Ayutthaya and Bago—active in the

Burma delta, the Malay Peninsula, and the Gulf of Siam. Both were invested

in Buddhist institutions and participated substantially in Indian Ocean trade.

3 King Dhammazedi’s Embassy to Koṭṭē

According to manuscript texts of the Kalyāṇi Inscriptions21 (KI) in 1475, Bago’s

King Dhammazedi sent an embassy of twenty-two senior bhikkhus, with

younger monks and attendants, to the court of Koṭṭē, in Laṅkā, to make devo-

tional offerings at the island’s most celebrated pilgrimage locations and to

obtain a pure monastic higher ordination suitable for Dhammazedi’s realm.

In these KI texts, the decision to send the embassy is framed in terms of the

19 See Hall (2010: esp. 113) on the rise of “more port-centered regional states” and Hall (2006:

esp. 455).

20 Note, however, Hall’s distinction between Ayutthaya and Bago with respect to the degree

of upstream control achieved by the former (2011: 234).

21 The manuscripts used to prepare the existing print edition of the KI are later and of

uncertain date, bearing an unclear relationship to the extant epigraphs containing nar-

ratives of King Dhammazedi’s embassy. The epigraphs themselves are in poor condition

and have not yet been systematically compared to KI manuscripts; see the comments

by Temple (1893) regarding a comparison of the stones and manuscripts. No mention of

Dhammazedi’s embassy has yet been found in the literary and inscriptional records of

Laṅkā. Nonetheless, the details about Lankan geography, monastic leadership, and the

Lankan court at Koṭṭē are accurate and consistent with other, Lankan, literary sources

from the period. See Sannasgala (1964) and Ilangasinha (1992). The KI’s treatment of

Buddhist history, monastic discipline, and the technical details of Buddhist ritual life sug-

gest that it draws on a variety of Buddhist genres, including vinaya commentary. This

composite character of the KI deserves further attention.

jesho 58 (2015) 237-266

248 Blackburn

heterogeneity and impurity of existing monastic lineages in the kingdom

(Taw Sein Ko 1893: 33-4, 155-6), and the king’s desire to secure the future of the

Buddha sāsana (39, 207).

Having appropriately invited experienced and competent bhikkhus, hav-

ing had them properly bring the extremely pure Lankan upasampadā

and establish it in this Ramaññadesa . . . I would make the sāsana, having

become clean and pure, able to extend to the limit of its 5000-year extent

(40, 207).22

King Dhammazedi is explicitly compared to the Indic King Asoka and the

Lankan King Parakramabāhu I) (r. 1153-1186) (38-9, 159, 207). This compari-

son sets the scene for King Dhammazedi’s intentions, as both Asoka and

Parakramabāhu I are portrayed in Mahāvaṃsa-Cūlavaṃsa chronicle-traditions

as rulers strong enough to control all Buddhist monks in their polity through a

royally sponsored act of monastic “purification.”

The KI describes Dhammazedi’s realm specifically as including the

Haṃsavati maṇdala, the Kusima maṇdala, and the Muttima maṇdala (34, 155-6),

thus encompassing the entire Burma delta region, from Pathein to Mottama.

The monks sent from Bago received higher ordination at the hands of Lankan

bhikkhus in Koṭṭē (210). This replaced their earlier monastic ordination status,

creating a new company of bhikkhus ordained at the Lankan Kalyāṅī ritual

boundary and ritually prepared to ordain other Bago monks in their Kalyāṇī

lineage. Upon returning to Bago the following year, the new ordinands partici-

pated in Dhammazedi’s elaborate reorganization of monastic life in his realm.

According to the KI report, monastic ritual sites were replaced, authority for

monastic ordination put in the hands of the king and the new Kalyāṇī com-

pany of monks, and local conferral of monastic higher ordination outside the

Kalyāṇī lineage expressly forbidden (52, 241-2).

The embassy to Koṭṭē and subsequent reordination of Buddhist monks in

the sphere of King Dhammazedi’s control was closely related to the recent

political history of Bago. The incorporation of Burma delta areas in Bago’s

control was a gradual process. The broadest control by the court at Bago was

attained during Dhammazedi’s reign (Aung-Thwin 2005, 311). From at least

the late first millennium onwards in the southern Asian region—as shown

by examples from Anurādhapura (Gunawardena 1979), Bagan (Aung-Thwin

1985), Chiang Mai (Swearer and Premchit 1978), and Kandy (Blackburn

2001)—achieving and retaining political and economic control in Buddhist-

22 I have modified the translation given by Taw Sein Ko.

jesho 58 (2015) 237-266

Buddhist Connections In The Indian Ocean 249

oriented kingdoms characterized by substantial monastic institutional pres-

ence required the state to control monastic administration and property. King

Dhammazedi sought to use the new Kalyāṅī ordination lineage brought from

Koṭṭē to assert control over Buddhist monks in his realm. Bhikkhus ordained in

earlier ordination lines lost monastic seniority and control over Buddhist insti-

tutions and property; monastic assignments could be made according to new

hierarchies introduced through the imported ordination line. This is explicitly

remarked in the KI. The Kalyāṇī bhikkhus fresh from their Lankan ordination

refuse to ordain any monks who do not first resume lay status. Within the new

monastic hierarchy, this protected the seniority of the monks associated with

the new Kalyāṇī lineage (52, 241).23

The embassy from Bago to Koṭṭē is an important indication of the matura-

tion of Buddhist connections and institutional ties linking mainland Southeast

Asia and Laṅkā during the first half of the second millennium. The scale of

Dhammazedi’s activities—the size of the embassy, the ability of his court to

command transportation technologies, and the extent to which a new monas-

tic order was institutionalized within the kingdom to further court control of

the monastic community—was remarkable. While the paucity of evidence

demands cautious comparison, it appears that both the size and local institu-

tional impact of the late-fifteenth-century Bago embassy were unprecedented.

It also required a command of wealth and maritime transportation sufficient

to support the grand overture to Koṭṭē. The scale of Indian Ocean trade by

the late fifteenth century, and the place of Bago in it, helped make possible

Dhammazedi’s Lankan adventure.24

The account of Tomé Pires, composed largely in the 1510s in Melaka, por-

trays a trading world in which Bago and Ayutthaya control the Burma delta

and northern Malay Peninsula, while Melaka serves as the key port of insu-

lar Southeast Asia and the main entrepôt between western India and China

(Cortesão 1944: esp. 97-105).25 At that time, well after the wars between Innwa

and Bago, Bago controlled three ports within the Burma delta region: Pathein

23 See also Aung-Thwin (2005: 115-6).

24 Hall suggests (2010: 134-7), drawing partly on Holt (1991) and Ilangasinha (1991), that

Dhammazedi was drawn to Koṭṭē in part by the fame of Koṭṭē’s court and Buddhist insti-

tutions, developed during the reign of King Parakramabāhu VI (r. 1412-68). This is possi-

ble, but we have as yet no evidence of whether or how reports of Parakramabāhu VI or the

still more famous Buddhist royal patron and centralizing force, King Parakramabāhu I

(r. 1153-86) circulated in the Buddhist world beyond Laṅkā. Chronicles thus far available

from Tai, Mon, and Burmese areas do not highlight the activities of these rulers.

25 See also the account of Barbosa from the early sixteenth century (Stanley 1866, 188).

jesho 58 (2015) 237-266

250 Blackburn

(Cosmin), Yangon (Dagon), and Mottama (Martaban). Other evidence sug-

gests that the division of power between Bago and Ayutthaya portrayed by

Pires existed already in the last third of the fifteenth century. Inscriptions

from Tenassarim dated from 1462 to 1466 strongly suggest the influence of the

Ayutthayan court there by this time (Vickery 1973: esp. 51-7),26 while Bago had

gradually consolidated control of the delta region (Fernquist 2006: esp. 50-1;

2008: esp. 85-93).

It is possible to distinguish more sharply between two scales of trade in the

Indian Ocean region after the rise of Melaka,27 and this helps us identify more

clearly the arena for Buddhist movements involving Bago and Laṅkā. Long-haul

trade between Cambay and Melaka circumnavigated Laṅkā before entering

the Straits of Melaka. At the same time, there were various shorter trade routes

that involved Lankan kingdoms and Buddhist-oriented polities in Southeast

Asia possessing maritime access. These shorter routes functioned partly to

provide goods from various Indian Ocean subregions to Cambay and Melaka,

via strong intermediary ports such as those on the Malabar and Coromandel

coasts, at Bengal, in Bago, and further south, on the Malay Peninsula. The

shorter trade routes could also serve more local needs, transporting goods not

destined for the larger east-west trade. It is possible that the voyages of Zheng

He and his activities along the Lankan coast also encouraged increased trade

after 1411 by securing sea lanes (Hall 2010: 113-4 n.12).28

Koṭṭē and Bago appear to have been bound together in the late fourteenth

and early fifteenth centuries partly through a rice-based trading relationship

routed via the Coromandel Coast. The reliance of parts of Laṅkā on imported

rice dated at least to the twelfth century (Nainar 1942: 17-8, 41; Strathern 2009,

52, citing de Silva 1995). Judging from Pires’s slightly later account, areca nuts

were among the prized Lankan commodities, traded on the Coromandel

Coast in return for rice and other commodities (Cortesão 1944: 84-6). Rice was

Bago’s major export. Bago’s port at Pathein traded with Bengal and ports on

India’s eastern coast, while her port at Mottama sent rice to Melaka (97-8).

Pires’s depiction of the intersection of Bago’s and Laṅkā’s interests at

Coromandel Coast ports is supported by the detailed account of maritime trans-

portation found in the KI, according to which travel to Bago was possible via the

seaport of Nāgapattanam and other outlets on the southeastern Indian coast.29

26 Cf. Coedès (1965).

27 I am grateful to Engseng Ho for his comment on this point.

28 See also Wade (2012). One man’s pirate is, of course, another’s entrepreneur.

29 Two ships left Laṅkā for Bago. The ship sent by the Lankan king with royal gifts for

his counterpart at Bago was shipwrecked in what KI calls the Silla (Sīhaḷa?) Strait,

jesho 58 (2015) 237-266

Buddhist Connections In The Indian Ocean 251

The KI mentions specifically two port administrators (paṭṭanādhikarinō [sic])

at Nāvutapattanam—Mālimparakāya and Pacchaḷiya—who were already con-

nected to Dhammazedi’s court at Bago via two ships sent annually for trade.30

These port administrators housed and cared for the shipwrecked party return-

ing from Laṅkā and arranged their onward journey to Bago.

Conclusion

Hall suggests that the period from 1300 to 1500 was characterized by “expansive

human networking” in the Bay of Bengal maritime region and that “sojourn-

ing merchants” and “religious clerics” played a central role in the integrity of

Indian Ocean port-polity networks during this period (2010: 138). According

to Hall, various types of “community interests,” beyond the “exclusively com-

mercial,” characterized this maritime space (139), one marked by Buddhist as

well Chinese, Persian and Yemeni-linked networks, and South Indian Muslim

and Hindu sojourners.

Hall’s discussion of merchant sojourners and religious clerics is suggestive

for the three episodes of Buddhist movement within southern Asia discussed

above, helping us to imagine better the interlocking interests, agencies, and

flow of ideas that were involved in the movement of Buddhist monks—as well

as their ritual forms and institutionally transformative lineages—in the Indian

between Laṅkā and the southeast coast of the Indian peninsula. This, in turn, triggered

a relay between ports on the eastern Indian coast and Bago, stopping at Nāgapattanaṃ

(Nagapattinaṃ), site of a long-famous coastal Buddhist temple-monastery, and

Nāvutapattanaṃ. From there, one party continued to Bago from Pathein, while another

went to Kōmālapattanaṃ and thence to Bago. According to Subbarayalu (personal

communication via O. Bopearachchi, June 2013), Nāvutapattanaṃ may be Nagur

(Nagore), a little north of Nagapattinam, mentioned as Tiru-Naavuur (see “Leyden

Plates.” Epigraphia Indica 22 (1933-34). Kōmālapattanam is probably Kovalam, north of

Mamallapuram. Kovalam is mentioned as a paṭṭanam (emporium), along with some

other paṭṭanams in a Vijayanagara inscription at Pennesvaramadam, Krishnagiri Taluk,

Krishnagri District, dated 21 July 1367 (see Krishnagiri District Inscriptions, Chennai 2007,

no. 77b/1973). I am grateful to Professors K. Subbarayalu, K. Rajan, S. Rajagopal, and

O. Bopearachchi for their assistance in this matter, and to Prof. B. Wentworth for discus-

sions of these references.

30 “[T]wo officers of the port had sent people for trade annually through two ships; sending

a gift to King Rāmādhipati [Dhammazedi] and experiencing his royal favor, they were

devoted to King Rāmādhipati. Thus, having given the senior monks robes and meals and

a place to reside, they served them” (45, 211-12). I have modified Taw Sein Ko’s translation.

jesho 58 (2015) 237-266

252 Blackburn

Ocean subregion encompassing the Bay of Bengal, the Burma delta, the Malay

Peninsula, and the Gulf of Siam. Although we do not yet possess adequate evi-

dence to link firmly the episodes of Buddhist mobility discussed above with

specific sojourning communities and mercantile interests, the instances of

Buddhist monastic movement addressed in this article do suggest a growth in

royally-supported Buddhist monastic movement in the region from the elev-

enth century, with larger and more elaborate Buddhist embassies to Laṅkā

developing during the fifteenth century. It is possible that the increasing scale

and ambition evident in the Buddhist embassies of the fifteenth century,

including that from Bago to Koṭṭē and the Chiang Mai/Kengtung monastic

cohort that traveled a half-century earlier, was due partly to the expansion and

consolidation of trading communities in the maritime space and its connected

riverine and overland routes, traveled by Buddhist monks. These communities

would have been in a position to support—financially, technologically, and

sometimes devotionally—large-scale, high-status Buddhist missions in the

region, supplementing whatever resources were provided by royal and monas-

tic patrons.

It is worth considering (in addition to the role of merchant communities)

as one of the conditions favoring the emergence of more substantial missions

in the fifteenth century, the ways in which the Buddhist-oriented royal courts

of Tai, Mon, and Burmese areas were linked through relations of competitive

imitation within the arena of Buddhist kingship. As noted earlier, Bago and

Ayutthaya had, by the fifteenth century, developed as flourishing maritime

kingdoms supportive of Buddhist ritual sites and monastic establishments.

These polities were rivals for trade, labor, and land. They were, along with

Chiang Mai, also rivals for recognition as the leading Buddhist righteous mon-

arch in the region.31 This is evident from the Buddhist titles adopted by the

kings of Bago, Ayutthaya, and Chiang Mai and the ways in which Buddhist

texts associated with Bago and Chiang Mai narrated the activities of their

rulers as continuous with the example of Buddhist kingship set by the Indic

King Asoka.32

31 On links and rivalries among these polities see, for instance, Aung-Thwin (2005: 125-30),

Wyatt (2004), Wyatt and Aroonrut (1995), Hall (2011), Charnvit (1976), Griswold (1965), and

Dhida (1982). Economic and other links between Chiang Mai and Bago offer promising

avenues for further investigation. I am grateful to professors U Hto La and Sarasawadee

Ongsakul for conversations about the overland-riverine economic ties between Bago and

Chiang Mai.

32 See, for instance, the translations in Cushman (2000), Jayawickrema (1968), and Taw Sein

Ko (1893). See also Aung-Thwin (2005: 115).

jesho 58 (2015) 237-266

Buddhist Connections In The Indian Ocean 253

There are striking temporal conjunctions between royally sponsored con-

struction of Buddhist buildings in these kingdoms, royally sponsored Buddhist

monastic reordination rituals, and Buddhist-related diplomatic contact

among these kingdoms. According to the Jinakālamālī and Tamnān Wat Jet Yòt,

Chiang Mai’s King Tilokarāja (r. 1441/2-87) in 1455 began construction of Wat

Bodhārama, a monastery and devotional site constructed over twenty years,

which—in name, ground plan, and architectural style—evoked Buddha’s

enlightenment site at Bodh Gaya, on the Indian mainland (Griswold 1965:

182-6; Jayawickrama 1968: 139-40; Buddhadatta 1962: 98; Hutchinson 1951: 43;

Blackburn 2007). During the same period, closely following Tilokarāja’s inau-

gural work at Wat Bodhārama in Chiang Mai,33 the Bago King Dhammazedi

sent a mission to Bodh Gaya via Laṅkā, with the assistance of a Sīhala (Lankan)

merchant residing at Bago, to obtain exact descriptions of the Buddhist sites

and monuments at Bodh Gaya, resulting in the construction of the Mahā Bodhi

Temple at Bago (Griswold 1965: 186-7).34

A growing mutual interest in foundational Indian Buddhist sites at Chiang

Mai and Bago during this period was matched by a striking conjunction

of large-scale royally sponsored Buddhist monastic reordinations held in

Ayutthaya, Chiang Mai, and Bago. Monks from Chiang Mai, Kengtung, and

“Kambojja” (perhaps the Lopburi area) traveled to Koṭṭē in Laṅkā, with the sup-

port of the monastic leaders of Chiang Mai and Ayutthaya. Upon their return

to Chiang Mai in 1424, the Chiang Mai monks were drawn into a royally spon-

sored reordination of Chiang Mai bhikkhus during the reign of King Sām Fang

Kän (r. 1401-41) and into the reorganization of local monastic administration

and hierarchy (Buddhadatta 1962: 93-5; see also Blackburn 2007). Throughout

the northern region, the newly imported Lankan higher ordinations enabled

the reorganization of local monastic ritual practice and hierarchy (Swearer

and Premchit 1977; Saimong 1981). Forty years later, towards the middle of

the reign of the Ayutthaya King Trailokarāja (r. 1448?-88), during a period of

increasing military threat from Chiang Mai and the relocation of Ayutthaya’s

capital to the north, near Sukhothai, Trailokarāja engaged in grand Buddhist

merit-making schemes to assure the protection of his realm (Charnvit 1976:

137-8; Cushman 2000: 17). According to Prachum Chotmaihet Samai Ayudhya

(Collected Ayudhyan Records) cited by Charnvit, King Trailokarāja in 1465

33 This occurred sometime between 1458 and 1472, according to the Burmese and Mon

sources Dhammacetimaṅ-atthuppatti and Nidāna Ārambhakathā (cited in Griswold 1965:

186-7).

34 For descriptions and images of the Bodh Gaya replicas at Chiang Mai and Bago, as well as

other locations, see Griswold (1965).

jesho 58 (2015) 237-266

254 Blackburn

organized a monastic ordination35 of more than two thousand men, including

his own temporary ordination (Charnvit 1976: 138-9; see also Cushman 2000: 17).36

The ordination ceremony was led by a Lankan monk, said to have been brought

from the island to the northern Ayutthayan capital of Phitsanulok. As Charnvit

notes, this bypassed the leaderships of the Sukhothai monastic community,

previously dominant in the north of the Ayutthayan realm. King Trailokarāja

was thus able to establish, near the military border with Chiang Mai, a new

monastic community at Phitsanulok, loyal to his administration. In addition

to its strategic value in the Ayutthayan realm, the ordination ceremony was

obviously intended as a larger diplomatic gesture to neighboring polities. The

rulers of Chiang Mai, Bago, and Luang Prabang reportedly sent gifts on the

occasion of King Trailokarāja’s temporary monastic ordination (Charnvit 1976:

138-9). Given Trailokarāja’s proximity to Chiang Mai and Sukhothai monastic

institutions at this time, his choice to ordain a new company of Buddhist monks

in the northern area of his kingdom with the support of a Lankan Buddhist

ritual officiant was probably informed by the earlier history of royal Buddhist

overtures to Laṅkā at Sukhothai and Chiang Mai, including the 1423-4 Chiang

Mai mission. King Trailokarāja’s monastic undertaking occurred just a decade

before King Dhammazedi’s massive reordination of bhikkhus under his control

at Bago in the new Kalyāṇī lineage from Koṭṭē (see previous section).

The episodes of Buddhist mobility discussed in this article, running from

the eleventh-century importation of Buddhist monks by the Poḷonnāruva King

Vijayabāhu I, through the fourteenth-century pilgrimage of the Sukhothai

monk Si Satha, to King Dhammazedi’s fifteenth-century embassy to Koṭṭē, sug-

gest that the first half of the second millennium was a transformative period

that saw the creation of new Buddhist institutional linkages in the Indian

Ocean Buddhist world, as new regimes of trade drew Laṅkā into faster and

closer connection with Burmese, Mon, peninsular Malay, and Tai locations.

Although we do not yet have adequate evidence from Buddhist sources to

support the view that “fifteenth-century Sri Lanka under Parakramabāhu VI

assumed significance as the acknowledged center of a conceptual Bay of

Bengal Theravada Buddhist cultural cosmopolis network” (Hall 2010: 139),37 it

35 This probably included the reordination of existing bhikkhus, but this is not clear in

Charnvit (1976); I do not have direct access to the Thai source.

36 Temporary royal ordination, especially in times of military or political duress, was not

uncommon in Tai areas, as shown in the inscriptions of Sukhothai and in Chiang Mai’s

Jinakālamālī. See also Blackburn (2007).

37 On the anachronism of “Theravāda Buddhist” applied outside narrow technical monastic

contexts before the nineteenth century, see Skilling 2012.

jesho 58 (2015) 237-266

Buddhist Connections In The Indian Ocean 255

is clear that the island played a significant role in the religious and maritime

trade networks of the period, including those of Hindus and Muslims as well

as Buddhists.

The changing patterns of trade referred to in this article help clarify how

such religious networks were constituted during the early second millennium.

Tilman Frasch argues that a long-standing Buddhist network in the Bay of

Bengal, active since the third century CE, fell into decline towards the end of the

thirteenth century, due in part to the disintegration of the Burman kingdom of

Bagan (1998, 92).38 Further investigation of inscriptions and monastic-lineage

texts from Burman territories is necessary in order to develop a clearer picture

of trans-regional Buddhist mobility involving Buddhist institutions at Bagan

and Innwa from the late thirteenth century on.39 The material presented in this

essay, however, indicates that, even if the northern inland Burman area became

less active in the trans-regional Buddhist mobility of the Bay of Bengal and the

Indian Ocean regions, Buddhist networks across this seascape remained viable

and were, in fact, strengthened by the conjunction of new trading patterns and

new political centers that grew up along the southern coastal areas of what

is now Sri Lanka, Burma, and Thailand. Further research is needed to clarify

whether Lankan Kandyan monastic overtures to Bago, Arakan, and Ayutthaya

in the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries should be understood as another

new chapter in trans-regional Buddhist mobility (Frasch 1998: 90), or whether

they may be understood as an extension, during the Dutch-English colonial

period, of the new patterns of southern Asian Buddhist traffic that developed

between the eleventh and the fifteenth centuries.

With respect to the new patterns of trans-regional Buddhist mobility that

developed during the first half of the second millennium, Buddhist sources clar-

ify the logic of overtures to Laṅkā at this time. According to the political theory

implied by Buddhist-royal histories like the chronicle texts referred to above,

the consolidation of royal power by a Buddhist-oriented monarch (whether or

not freshly consecrated) required several interventions in Buddhist arenas:

public merit-making activities that signaled the right to rule and protected the

ruler and the realm; the reorganization of monastic administration in order to

ensure that high-ranking monks (sometimes also functioning in court admin-

istration and/or as landholders) were loyal to the throne; and “purification” of

the monastic community as a sign of the ruler’s devoted wish to extend the

vitality and longevity of the Buddhist tradition. “Purification” of the monas-

tic community and the reorganization of monastic administration typically

38 See also Goh (2007: 53).

39 I am grateful to Alexey Kirichenko for preliminary conversations on this matter.

jesho 58 (2015) 237-266

256 Blackburn

occurred together. One effective means of accomplishing both was to intro-

duce a new monastic higher-ordination lineage from another Buddhist loca-

tion held in esteem. Such goals evidently shaped King Dhammazedi’s approach

to Koṭṭē in the 1470s and King Sām Fang Kän’s response to the monks returning

from Koṭṭē in the 1420s. They may have influenced King Vijayabāhu I’s over-

tures to Ramañña in the late eleventh century.

It is striking that, in a period of approximately fifty years during the fifteenth

century, Bago, Chiang Mai, and Ayutthaya all took steps to consolidate their

authority according to the Buddhist political theory outlined above. In doing

so, all resorted to Laṅkā as the source for a new monastic higher-ordination

lineage capable of “purifying” and reorganizing monastic administration in the

realm. Why did they focus on Laṅkā in this way? Laṅkā’s authoritative posi-

tion was due partly to the island’s long-standing and positive image within

Buddhist contexts. Laṅkā had a long and impeccable pedigree as a center

of Buddhist life. It was celebrated by early Buddhist chronicles (in Sanskrit

as well as Pāli) as a site honored by Gautama Buddha himself, said to have

predicted Lankan guardianship of Buddhist teachings. Laṅkā’s lineages of

Buddhist monks and nuns descended from the famous Indian Mauryas. The

island had played host to the most famous commentator on authoritative

Pāli Buddhist texts, Buddhaghosa, whose fifth-century Lankan compositions

traveled gradually outwards through Southern Asia. At least in Pāli-language

works, Laṅkā was the location most frequently and thoroughly described after

northeastern India/Nepal, the site of Gautama Buddha’s first activities, and

reports of Laṅkā were carried around Asia by pilgrims such as the seventh-

century traveler Yijing.

Another factor was the regional decline of Buddhist intellectual and ritual

centers concomitant with the rise of Islam in northeastern India and insular

Southeast Asia from the thirteenth century onward. Although it is now clear

that earlier arguments for the wholesale displacement of Buddhism by Islam

in northeastern India during this period were overstated, massive monastic

centers such as that at Nālanda no longer received large-scale royal patronage.

On the islands of Java and Sumatra, earlier Buddhist centers gave way to sul-

tanates oriented towards Islam. Therefore, when royal courts of Tai, Mon, and

Burmese lands sought to import new monastic higher ordination lineages that

could be used to “purify” and reorganize Buddhist monasticism in their king-

doms, they faced a shrinking Buddhist world.40 If they wished to use monastic

higher ordination lineages that shared their existing use of Pāli as a scriptural/

liturgical language and that could argue for historical connections to the third-

40 I am grateful to Geoff Wade and Alexey Kirichenko for conversations on this point.

jesho 58 (2015) 237-266

Buddhist Connections In The Indian Ocean 257

century BCE monastic community of the Indian King Asoka, they could look

only among their mainland neighbors or to Laṅkā.

Laṅkā was a strategic choice. In addition to the positive historical associa-

tions that had long existed around Lankan Buddhist monks and institutions,

the island was generally distant from political and military conflicts on the

Southeast Asian mainland. There is no evidence of aggression from Laṅkā

against Tai, Mon, or Burmese polities, apart from Poḷonnāruva’s raid on the

Burma delta.41 Long described as a center of Buddhist education and monas-

tic practice, with deep historical links to early Indian Buddhist lineages and

institutions, Laṅkā was ideologically close. Lankan kingdoms were, however,

usually politically distant from mainland competition and aggression, without

the military might to intervene in the region of the Burma delta and the Gulf

of Siam.42 Thus, Laṅkā’s desirability in Buddhist ideological terms was further

enhanced by the island’s relative weakness in politico-military terms. It stood

outside the fraught history of mainland diplomatic and military adventuring

that characterized kingdoms in what is now Burma and Thailand, including

the dominant Buddhist-oriented polities of the fourteenth and fifteenth cen-

turies: Chiang Mai, Ayutthaya, and Bago.

Bibliography

Abraham, Meera. 1988. Two Medieval Merchant Guilds of South India. Delhi: Manohar.

Andaya, Leonard Y. 2008. Leaves of the Same Tree: Trade and Ethnicity in the Straits of

Melaka. Honolulu: University of Hawai’i Press.

Aung-Thwin, Michael. 2005. The Mists of Ramañña: The Legend That Was Lower Burma.

Honolulu: University of Hawai’i Press.

———. Pagan: The Origins of Modern Burma. Honolulu: University of Hawai’i Press.

Blackburn, Anne M. 1999. Looking for the Vinaya: Monastic Discipline in the Practical

Canons of the Theravāda. Journal of the International Association of Buddhist

Studies. 22/2: 281-309.

———. 2001. Buddhist Learning and Textual Practice in Eighteenth-Century Lankan

Monastic Culture. Princeton University Press.

41 The chronicles of Nakhon Si Thammarat (Wyatt 1975) are late compositions, extant only

in poor manuscript witnesses. I am not yet persuaded that Laṅkā made military incur-

sions into Nakhon Si Thammarat in the twelfth century or made that polity a tributary of

the island.

42 I have benefited from discussions with Chris Hinkle, Drew Johnson, and Steve Collins on

this point.

jesho 58 (2015) 237-266

258 Blackburn

———. 2007. Writing Histories from Landscape and Architecture: Sukhothai and

Chiang Mai. Buddhist Studies Review 24/2: 192-225.

———. 2010. Locations of Buddhism: Colonialism and Modernity in Sri Lanka. Chicago:

University of Chicago Press.

———. 2012. Lineage, Inheritance, and Belonging: Expressions of Monastic Affiliation

from Laṅkā. In How Theravāda is the Theravāda?, ed. Peter Skilling, Jason Carbine,

Claudio Cicuzza, and Santi Pakdeekham. Chiang Mai: Silkworm Books: 275-96.

———. Forthcoming. Sīhaḷa Saṅgha and Laṅkā in Later Premodern Southeast Asia. In

Buddhist Dynamics in Premodern Southeast Asia, ed. D. Christian Lammerts.

Singapore: Institute for Southeast Asian Studies.

Baker, Chris. 2003. Ayutthaya Rising: From Land or Sea? Journal of Southeast Asian

Studies 34/1: 41-62.

Bauer, Christian. 1991a. Notes on Mon Epigraphy I. Journal of the Siam Society 79/1: 31-83.

———. 1991b. Notes on Mon Epigraphy II. Journal of the Siam Society 79/2: 61-77.

Bode, Mabel. 1996. Sāsanavaṃsa. Oxford: Pali Text Society.

Bopearachchi, O. 1996. Seafaring in the Indian Ocean: Archaeological Evidence from

Sri Lanka. In Tradition and Archaeology: Early Maritime Contacts in the Indian

Ocean, ed. H.P. Ray and J.F. Salles. Delhi: Manohar Publications: 59-77.

Buddhadatta, A.P. 1962. Jinakālamālī. London: Pali Text Society.

Chamberlain, James R. 1991. The Ram Khamhaeng Controversy: Collected Papers.

Bangkok: Siam Society.

Carswell, John, Siran Deraniyagala, and Alan Graham, ed. 2013. Mantai: City by the Sea.

Aichwald: Archaeology Department of Sri Lanka.

Charnvit Kasetsiri. 1976. The Rise of Ayudhya: A History of Siam in the Fourteenth and

Fifteenth Centuries. Kuala Lumpur: Oxford University Press.

Christie, Jan Wisseman. 1998a. The Medieval Tamil-Language Inscriptions in Southeast

Asia and China. Journal of Southeast Asian Studies 29/2: 239-68.

———. 1998b. Javanese Markets and the Asian Sea Trade Boom of the Tenth to

Thirteenth Centuries AD. Journal of the Economic and Social History of the Orient

41:3: 344-81.

Coedès, Georges. 1965. Documents épigraphiques provenant de Tenasserim. In

Felicitation Volumes of South-East Asian Studies Presented to His Highness Prince

Dhaninivat Kromamun Bidyalabh Bridhyakorn. Bangkok: Siam Society: 2: 203-9.

———, ed. and trans. 1924. Recueil des inscriptions du Siam, I. Bangkok: National

Library of Thailand.

Collins, Steven. 2003. What is Literature in Pāli? In Literary Culture in History:

Reconstructions from South Asia, ed. Sheldon Pollock. Berkeley: University of

California Press: 649-88.

Cortesão, Armando, trans. and ed. 1944. The Suma Oriental of Tomé Pires: An Account of

the East: From the Red Sea to Japan, Written in Malacca and India in 1512-1515. London:

Hakluyt Society.

jesho 58 (2015) 237-266

Buddhist Connections In The Indian Ocean 259

Cushman, Richard D., trans. 2000. The Royal Chronicles of Ayutthaya. Bangkok: Siam

Society.

Cūlavaṃsa. 1925. Ed. Wilhelm Geiger. London: Pali Text Society.

Daniels, Christian. 2000. The Formation of Tai Polities Between 13th to 16th Centuries:

The Role of Technological Transfer. Memoirs of the Toyo Bunko 58: 51-98.

Davidson, Ronald. 2002. Indian Esoteric Buddhism: A Social History of the Tantric

Movement. New York: Columbia University Press.

De Silva, C.R. 1985. Muslim Traders in the Indian Ocean in the Sixteenth Century and

the Portuguese Impact. In The Muslims of Sri Lanka, ed. M.A.M. Shukri. Beruwala:

Jamiah Naleemia Institute: 147-65.

Dewaraja, Lorna. 1990. Muslim Merchants and Pilgrims in Serandib c. 900-1500 AD. In

Sri Lanka and the Silk Road of the Sea, ed. Senake Bandaranayake et al. Colombo: Sri

Lanka National Committee for UNESCO and Central Cultural Fund: 191-8.

———. 1988. The Kandyan Kingdom of Sri Lanka, 1707-1782. Colombo: Lake House.

Dhida Saraya. 1982. The Development of the Tai States from the Twelfth to the Fifteenth

Centuries. Unpublished Ph.D. diss., University of Sydney.

Epigraphia Zeylanica, Being Lithic and Other Inscriptions of Ceylon. 1904-84. 7 vols.

Colombo: Ceylon Government Printer.

Feener, R. Michael. 2010. South-East Asian Localizations of Islam and Participation

within a Global Umma, c. 1500-1800. In The New Cambridge History of Islam, ed.

David O. Morgan and Anthony Reid. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press:

3:470-503.

——— and Michael F. Laffan. 2005. Sufi Scents Across the Indian Ocean: Yemeni

Hagiography and the Earliest History of Southeast Asian Islam. Archipel 70: 185-208.

Fernquest, Jon. 2008. The Ecology of Burman-Mon Warfare and the Premodern

Agrarian State (1383-1425). SOAS Bulletin of Burma Research 6/1-2: 70-118.

———. 2006. Crucible of War: Burma and the Ming in the Tai Frontier Zone (1382-

1454). SOAS Bulletin of Burma Research 4:2:27-81.

Frasch, Tilman. 1998. A Buddhist Network in the Bay of Bengal: Relations between

Bodhgaya, Burma, and Sri Lanka, c. 300-1300. In From the Mediterranean to the China

Sea: Miscellaneous Notes, ed. Glaude Guillot, Denys Lombard, and Roderick Ptak.

Wiesbaden: Harrassowitz, 69-92.

———. 2002. Coastal Peripheries during the Pagan Period. In The Maritime Frontier of

Burma: Exploring Political, Cultural and Commercial Interaction in the Indian Ocean

World, 1200-1800, ed. Jos Gommans and Jacques Leider. Leiden: KITLV Press: 590-78.

Fukami Sumio, 2004. The Long 13th Century of Tambralinga: From Javaka to Siam.

Memoirs of the Toyo Bunko, 62: 45-79.

Geiger, Wilhelm, trans. 1992. Cūḷavaṃsa, Being the More Recent Part of the Mahāvaṃsa.

London: Pali Text Society.

Goitein, S.D., and Mordechai Akiva Friedman. 2008. Indian Traders from the Middle

Ages: Documents from the Cairo Geniza. Leiden: Brill.

jesho 58 (2015) 237-266

260 Blackburn

Goh, Geok Yian. 2007. Cakkravatiy Anuruddha and the Buddhist Oikoumene: Historical

Narratives of Kingship and Religious Networks in Burma, Northern Thailand, and

Sri Lanka (11th-14th Centuries). Unpublished Ph.D. diss., University of Hawai’i.

Grabowsky, Volker. 2010. The Northern Tai Polity of Lan Na (Ba-ba Da-dian) in the 14th

and 15th Centuries: The Ming Factor. In Southeast Asia in the Fifteenth Century: The

China Factor, ed. Geoff Wade and Sun Laichen. Singapore: National University of

Singapore Press: 197-245.

Griswold, A.B. 1965. Holy Land Transported. Colombo: Gunasena and Sons.

——— and Prasert ṇa Nagara. 1992. Epigraphical and Historical Studies. Bangkok:

Historical Society.

Gunawardana, R.A.L.H. 1990. Seaways to Serendib: Changing Patterns of Navigation in

the Indian Ocean and Their Impact on Precolonial Sri Lanka. In Sri Lanka and the

Silk Road of the Sea, ed. Senake Bandaranayake et al. Colombo: Sri Lanka National

Committee for UNESCO and Central Cultural Fund: 25-43.

———. 1979. Robe and Plough: Monasticism and Economic Interest in Early Medieval Sri

Lanka. Tucson: University of Arizona Press.

Gutman, Pamela. 2002. The Martaban Trade: An Examination of the Literature from

the Seventh Century until the Eighteenth Century. Asian Perspectives 40/1: 108-18.

Haider, Najaf. 2007. The Network of Monetary Exchange in the Indian Ocean Trade,

1200-1700. In Cross Currents and Community Networks: The History of the Indian

Ocean World, ed. Himanshu Prabha Ray and Edward A. Alpers. Delhi: Oxford

University Press: 181-205.

Hall, Kenneth R. 2011. A History of Early Southeast Asia: Maritime Trade and Societal

Development, 100-1500. Lanham: Rowman and Littlefield.

———. 2010. Ports-of-Trade, Maritime Diasporas, and Networks of Trade and Cultural

Integration in the Bay of Bengal Region of the Indian Ocean: c. 1300-1500. Journal of

the Economic and Social History of the Orient 53: 109-45.

———. 2006. Multi-Dimensional Networking: Fifteenth-Century Indian Ocean

Maritime Diaspora in Southeast Asian Perspective. Journal of the Economic and

Social History of the Orient 49/4: 454-81.

Hazra, Kanai Lal. 1981. History of Theravada Buddhism in South-East Asia. Delhi:

Munshiram Manoharlal.

Heng, Derek Thiam Soon. 2009. Sino-Malay Trade and Diplomacy from the Tenth

through the Fourteenth Century. Athens: Ohio University Press.

Hettiaratchi, S.B. 2003. Studies in Cheng-Ho in Sri Lanka. In Zheng He xia Xiyang guoji

xueshu yantaohui lunwen ji (Papers from the International Academic Conference on

Zheng He’s Voyages to the Western Ocean), ed. Chen Xin-xiong and Chen Yu-nü.

Taipei: Daw Shiang.

Ho, Engseng. 2006. Genealogy and Mobility Across the Indian Ocean. Berkeley: University

of California Press.

jesho 58 (2015) 237-266

Buddhist Connections In The Indian Ocean 261

Holt, John Clifford. 2004. The Buddhist Visnu. New York: Columbia University Press.

Hultzsch, E. 1902-3. A Vaishnava Inscription at Pagan. Epigraphia Indica 7: 197-98.

Hutchinson, E. 1933. Journey of Mgr. Lambert, Bishop of Beritus, from Tenasserim to

Siam in 1662. Journal of the Siam Society 26/2: 215-17.

Indrapala, K. 1985. The Role of Peninsular Indian Muslim Trading Communities in the

Indian Ocean Trade. In The Muslims of Sri Lanka, ed. M.A.M. Shukri. Beruwala:

Jamiah Naleemia Institute.

———. 1971-2. South Indian Mercantile Communities in Ceylon, Circa 950-1250.

Ceylon Journal of Historical and Social Studies n.s. 1/2: 101-13.

———. 1963. The Nainativu Tamil Inscription of Parakramabahu I. University of Ceylon

Review 21/1: 63-70.

Ilangasinha, H.B.M. 1992. Buddhism in Medieval Sri Lanka. Delhi: Sri Satguru.

Ishii, Yoneo. 2003. A Note on the Identification of a Group of Siamese Port-Polities

along the Bay of Thailand. Memoirs of the Research Department of the Toyo Bunko 61:

75-82.

Jacq-Hergoualc’h, Michel, 2002a. Trans. Victoria Hobson. The Malay Peninsula:

Crossroads of the Maritime Silk Road. Leiden: Brill.

———. 2002b. The Mergui-Tennaserim Region in the Context of the Maritime Silk

Road: From the Beginning of the Christian Era to the End of the Thirteenth Century

AD. In The Maritime Frontier of Burma: Exploring Political, Cultural and Commercial

Interaction in the Indian Ocean World, 1200-1800, ed. Jos Gommans and Jacques

Leider. Leiden: KITLV Press: 79-92.

———, Michel, Tharapong Srisuchat, Thiva Supajanya, and Wichapan Krisanapol.

1996. La région de Nakhon Si Thammarat (Thaïlande péninsulaire) du Ve au XIVe

siècle. Journal Asiatique 284/2: 361-435.

Jayawickrema, N.A. 1968. The Sheaf of Garlands of the Epochs of the Conqueror. London:

Pali Text Society.

Kanazawa Yoh. 2004. Chinese Trade Ceramics Discovered in Sri Lanka. In In Search of

Chinese Ceramic-Sherds in South India and Sri Lanka, ed. Karashima Noboru. Tokyo:

Taisho University Press: 56-8.

———. 2004. Mantai and Polonnaruva. In In Search of Chinese Ceramic-Sherds in South

India and Sri Lanka, ed. Karashima Noboru. Tokyo: Taisho University Press: 59-60.

Karashima. Noboru. 2009a. Medieval Commercial Activities in the Indian Ocean. In

Nagapattinam to Suvarnadwipa: Reflections on the Chola Naval Expeditions to

Southeast Asia, ed. Hermann Kulke, K. Kesavapany, and Vijay Sakhuja. Singapore:

Institute for Southeast Asian Studies: 20-60.

———. 2009b. South Indian Merchant Guilds in the Indian Ocean and Southeast Asia.

In Nagapattinam to Suvarnadwipa: Reflections on the Chola Naval Expeditions to

Southeast Asia, ed. Hermann Kulke, K. Kesavapany, and Vijay Sakhuja. Singapore:

Institute for Southeast Asian Studies: 135-57.

jesho 58 (2015) 237-266

262 Blackburn

Kirabamune, Sirima. 2013. The Role of the Port City of Mahatittha (Mantai) in the

Trade Networks of the Indian Ocean. In Mantai: City by the Sea, ed. John Carswell,

Siran Deraniyagala, and Alan Graham. Aichwald: Archaeology Department of

Sri Lanka: 40-52.

———. 1985. Muslims and the Trade of the Arabian Sea with Special Reference to Sri

Lanka from the Birth of Islam to the Fifteenth Century. In The Muslims of Sri Lanka,

ed. M.A.M. Shukri. Beruwala: Jamiah Naleemia Institute: 89-112.

Kirichenko, Alexey. 2005. History in the Retrospect of Discipline: Constructing the

Genealogy of Transmission of the Buddhist Teaching in the Nineteenth Century

Myanmar. In Asiatica: Papers on Oriental Philosophies and Cultures. Issue 1: Prof.

Evgeny A. Torchinov 50th Anniversary Commemoration Volume. St. Petersburg:

St. Petersburg University Press (in Russian).

———. 2009. What’s in a Name? The Evolution of Nomenclature and Scope of

Lordship in Indigenous Burmese Discourse. Paper presented at the Association of

Asian Studies, Chicago.

———. 2011. Change, Fluidity, and Unidentified Actors: Understanding the Organiza-

tion and History of Upper Burmese Saṃgha from the Seventeenth to the Nineteenth

Centuries. Paper presented at the Association of Asian Studies, Honolulu.

———. 2013. Travels of “Sīhaḷa Monk” Sāralaṅka and Buddhist Transregionalism in

Eighteenth-Century Burma. Paper presented at the Asia Research Institute work-

shop “Orders and Itineraries: Buddhist, Christian and Islamic Networks in Southern

Asia, 900-1900,” Singapore.

———. Forthcoming a. New Spaces for Interaction: Contacts between Burmese and

Sinhalese Monks in the Late Nineteenth and Early Twentieth Centuries. Institute for

Southeast Asia Working Papers, Singapore.

———. Forthcoming b. Dynamics of Monastic Mobility and Networking in Upper

Myanmar of the Seventeenth and Eighteenth Centuries. In Buddhist Dynamics in

Premodern Southeast Asia, ed. D. Christian Lammerts. Singapore: Institute of

Southeast Asian Studies.

Kulasuriya, Ananda S. 1976. Regional Independence and Elite Change in the Politics of

14th Century Sri Lanka. Journal of the Royal Asiatic Society 2: 136-55.

Kulke, Hermann. 1999. Rivalry and Competition in the Bay of Bengal in the Eleventh

Century and Its Bearing on Indian Ocean Studies. In Commerce and Culture in the

Bay of Bengal, 1500-1800, ed. Om Prakash and Denys Lombard. Delhi: Manohar: 17-36.

Lammerts, Dietrich Christian. 2005. The Dhammavilāsa Dhammathat: A Critical

Historiography, Analysis, and Translation of the Text. M.A. Thesis, Cornell University.

Law, Bimala Churn. 1952. The History of the Buddha’s Religion (Sāsanavaṃsa). London:

Luzac.

Leider, Jacques P. 2008. Forging Buddhist Credentials as a Tool of Legitimacy and

Ethnic Identity: A Study of Arakan’s Subjection in Nineteenth-Century Burma.

Journal of the Economic and Social History of the Orient 51: 409-59.

jesho 58 (2015) 237-266

Buddhist Connections In The Indian Ocean 263

Lieberman, Victor B. 2003-9. Strange Parallels. 2 vols. Cambridge: Cambridge University

Press.

———. 1976. A New Look at the Sāsanavaṃsa. Bulletin of the School of Oriental and

African Studies 39/1: 137-49.

Malalgoda, Kitsiri. 1976. Buddhism and Sinhalese Society, 1750-1900: A Study of Revival

and Change. Berkeley: University of California.

Manatunga, Anura. 2009. Sri Lanka and Southeast Asia during the Period of the

Polonnaruva Kingdom. In Nagapattinam to Suvarnadwipa: Reflections on the Chola

Naval Expeditions to Southeast Asia, ed. Hermann Kulke, K. Kesavapany, and Vijay