Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Report Card Ports-2021

Uploaded by

Qoyyum RachmaliaCopyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Report Card Ports-2021

Uploaded by

Qoyyum RachmaliaCopyright:

Available Formats

Ports

80

________

2021 INFRASTRUCTURE REPORT CARD

www.infrastructurereportcard.org

EXECUTIVE SUMMARY

The nation’s more than 300 coastal and inland ports are significant drivers of

the U.S. economy, supporting 30.8 million jobs in 2018 and 26% of the total

GDP. Ports and port tenants plan to spend $163 billion between 2021 and

2025, up by over $8 billion over the last four years. Investments are focused

on capacity and efficiency enhancements as maximum vessel size has doubled

over the last 15 years, and tonnage at the top 25 ports grew by 4.4% from 2015

to 2019. Federal funding has increased through multimodal competitive grant

programs. However, there is a funding gap of over $12 billion for waterside

infrastructure such as dredging over the next 10 years, with additional billions

needed for landside infrastructure. Smaller and inland ports are especially

challenged to maintain their infrastructure and have difficulty competing

for federal grants. Meanwhile, a port’s success is reliant on the infrastructure

outside of its gates, which is often congested or in poor condition. For example,

just 9% of intermodal connector pavement — the portions of roadway that

connect a port to other modes — are in good or very good condition.

INTRODUCTION

The United States’ more than 300 ports1 serve as major liquids and manufactured goods and equipment.

economic drivers and places of employment. According

Port facilities vary widely in terms of productivity,

to the American Association of Port Authorities (AAPA),

footprint, customers, and governance.3 Some ports

seaports contributed $5.4 trillion to the economy, or

are privately owned and operated, while others are

nearly 26% of the total GDP in 2018. The economic

managed by a government or quasi-government

impact of ports is only growing. AAPA estimates that

authority representing a city or state.4 The owner of a

30.8 million jobs were supported by ports in 2018, up

port may lease space or infrastructure to a tenant, most

from 23.1 million in 2014.2

commonly a terminal operator. Terminal operators are

Seaports in the U.S. are often located in or adjacent to responsible for maintaining equipment and buildings, but

large coastal metropolitan areas. By comparison, inland typically partner with a public agency for major capital

ports are located on the Great Lakes or the inland projects.5 The varied ownership structures contribute to

waterway network and are frequently in more rural the uniqueness of each port — the industry saying goes,

areas. Ports thrive on their flexibility to handle a variety “once you’ve seen one port, you’ve seen one port.”

of products, from bulk aggregates and agriculture to

81

________

2021 INFRASTRUCTURE REPORT CARD

www.infrastructurereportcard.org

CAPACITY & CONDITION

Port infrastructure includes docks, piers, channel

harbors, and more. In general, the conditions from

terminal to terminal within a port vary. However, all ports

are challenged to maintain their infrastructure in harsh

marine environments. Corrosion from saltwater and de-

icing salts, constant wet and dry cycles, temperature

variations, and more accelerate the rate of decline of

everything from cranes to wharfs.6 Port owners are

tasked with monitoring the structural integrity of their

infrastructure in these harsh environments.

Many ports can trace their origins back a century or more,

and all owners are pressed to continue to modernize their

infrastructure. Seaports, for example, are consistently

expanded to accommodate larger container ships. Vessel

capacity at container ports is measured in TEUs, or

“twenty-foot equivalents,” which equals one 20-foot

container. Maximum vessel capacity has doubled in size

over the last 15 years, from 10,000 TEUs in 2005 to

almost 20,000 TEUs today.7 As vessels have increased

in size, port infrastructure — including berths, cranes,

and channel depths — have required investment to keep

pace. Today, a growing number of shallow water ports are

dredged to a channel depth of 45 feet or more, which is

necessary for accommodating post-Panamax ships that

are now able to traverse an expanded Panama Canal.8

Other retrofits and modernizations are needed to

accommodate larger ships, including larger cranes.

According to the U.S. Department of Transportation’s

(DOT) Bureau of Transportation Statistics (BTS), in

Creative Commons

2019 the top 25 container ports operated a total of 504

CRANES AT PORT OF GALVESTON IN TEXAS

Many ports can trace their

origins back a century or more,

and all owners are pressed to

continue to modernize their

infrastructure.

82

________

2021 INFRASTRUCTURE REPORT CARD

www.infrastructurereportcard.org

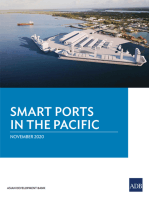

ship-to-shore gantry cranes, and nearly 50%, or 235, Figure 1. Intermodal

were classified as super post-Panamax, or cranes large Connector Pavement Condition

enough to load and unload super post-Panamax ships.9

In general, ports are expanding and adding capacity

across the country. BTS reports the total tonnage

handled at the top 25 ports in the country grew by 4.4%

Fair

from 2015 to 2019.10 This growth is reflective of an 35% Mediocre

industry that is investing in its capacity and growing its 19%

ability to accommodate larger volumes.

While most ports are adding capacity to address growing

freight volumes, their success is contingent on the capacity Good

of, and ease of access to, other modes of transportation 8%

such as roads and rail. On-dock rail allows for containers Poor

37%

to be loaded directly onto rail lines that are adjacent to

Very Good

port terminals. According to BTS, a total of 44 out of the 1%

88 active container terminals at major U.S. ports had on-

dock rail access in 2019. All major ports either have on-

dock rail or are located nearby to rail facilities.11

Intermodal connectors are

Intermodal connectors are the portions of roadways that

the portions of roadways that

link our National Highway System to ports and other

modes. These segments are traditionally underfunded, as link our National Highway

historically they have not fit neatly into existing funding System to ports and other

programs. A 2017 Federal Highway Administration

(FHWA) report collected pavement condition readings modes. These segments are

from the 798 designated freight intermodal connectors and traditionally underfunded, as

found that 37% of pavement condition was rated as poor.

These segments also contend with congestion; FHWA

historically they have not fit

specifically identifies port connectors as having some of the neatly into existing funding

worst congestion, with a 14% speed drop between free-flow

programs.

conditions and slowest daytime conditions.12

FUNDING & FUTURE NEED

Funding for port infrastructure is derived from a variety For the first time, in Fiscal Year (FY) 2019, total Harbor

of sources, including federal, state, and local funding, Maintenance Trust Fund appropriations met the level

as well as private sector revenue streams. Waterside of new receipts and interest. The subsequent CARES

infrastructure needs, namely for dredging, are paid for Act codified the requirement that the money coming in

through the federal Harbor Maintenance Trust Fund must be spent on dredging, as intended by the original

(HMTF). The HMTF collects its revenue through a creation of the Harbor Maintenance Trust Fund. The

0.125% user fee on the value of the cargo in imported 2020 Water Resources Development Act took this a

containers, which equates to approximately $15 per step further, allowing for the use of the unspent balance

container box. Ports, particularly on the East and Gulf of $9.3 billion dollars in the HMTF by 2030.13

coasts, have significant dredging needs, but the fund’s

Landside federal funding is typically provided through

balance has traditionally been used to pay for things

grants. The U.S. DOT’s Better Utilizing Investments

other than port needs, its designated purpose.

to Leverage Development (BUILD) Transportation

83

________

2021 INFRASTRUCTURE REPORT CARD

www.infrastructurereportcard.org

Discretionary Grant program allows for federal Some states have dedicated funding for ports, including

multimodal investment opportunities. The BUILD Florida, Minnesota, Missouri, Virginia, and others.19 20 21 22

program and its predecessor (Transportation Investment Additionally, ports — especially those located inland

Generating Economic Recovery, or TIGER) provide an — have a diversified revenue stream that can include

average of 12% of available funding each round to port housing, urban development, and more.

projects, or roughly $1 billion over the past 11 cycles.14

In general, ports continue to invest in their own

A newer program is the FAST Act’s Nationally infrastructure. A survey conducted by the American

Significant Freight and Highway Projects program, Association of Port Authorities (AAPA) reports

renamed INFRA in 2017. INFRA is designed for large that ports and port tenants plan to spend $163 billion

highway freight projects, but up to $500 million can be between 2021 and 2025, up from the forecasted $154.8

spent on multimodal projects, including those located billion in the 2016-2020 AAPA study. Many ports have

inside a port gate. So far, 16% of available INFRA successfully leveraged the modest increases in available

dollars have been awarded to port projects, or roughly public funding to make more efficient and innovative

$358 million.15 Both INFRA and the BUILD program investments in capacity and condition projects.23 It

are oversubscribed, with approximately $10 or more of should be noted that forecasted capital spending over

requests for every $1 available for award.16 the next four years is contingent on an economic

recovery and the continued availability of federal and

Additionally, federal funding is now available through

state funding.

the U.S. DOT Maritime Administration’s Port

Infrastructure Development Program (PIDP). PIDP ASCE’s 2021 Failure to Act economic study looks at

was authorized in the FY2010 National Defense available funding compared to needs for navigational-

Authorization Act but was not appropriated money related improvements, including dredging and lock and

until FY2019. Congress’ FY2019 appropriations bill dam repair. The report shows that unmet waterside

provided $287 for PIDP, and $221 million was available infrastructure needs at coastal ports will be $12.3

the following year.17 18 It should be noted that most billion over the next 10 years.24 Importantly, ASCE’s

PIDP funding is reserved for coastal seaports or Great infrastructure gap estimate does not consider landside

Lake ports, meaning inland ports receive a much smaller investments. In 2018, AAPA’s U.S. member ports

amount of funding. identified $32.03 billion for landside needs.25 Inland

river ports and terminals also have significant needs

that are not reflected in the AAPA estimate.

84

________

2021 INFRASTRUCTURE REPORT CARD

www.infrastructurereportcard.org

In the coming years, port owners and city planners will need to

decide how to handle sea level rise. Relocating an entire port to

higher ground is almost certainly cost-prohibitive, but port owners

may decide to raise docks or relocate facilities offshore. Connecting

modes, such as on-dock rail and service roads, would similarly

need updates to continue providing access to ports.

Creative Commons

OPERATIONS & MAINTENANCE

The USDOT Strategic Plan identifies lifecycle and better at considering resiliency to threats like weather

preventive maintenance as a strategic objective to and earthquakes. The Maritime Administration

keep the nation’s infrastructure in a state of good subsequently instituted a risk-based asset management

repair. To implement this strategic objective, the program and is encouraging port owners and operators

Maritime Administration initiated an internal review in to utilize the risk rating and scoring systems created by

2017 and found that ongoing planning frequently fails the agency.26

to target state-of-good-repair projects and could be

85

________

2021 INFRASTRUCTURE REPORT CARD

www.infrastructurereportcard.org

PUBLIC SAFETY & RESILIENCE

Ports have a key role to play in helping a community In the coming years, port owners and city planners will

recover from a natural or manmade disaster. Goods need to decide how to handle sea level rise. Relocating

can be transported via oceans and inland waterways an entire port to higher ground is almost certainly cost-

to communities in need when other trade routes prohibitive, but port owners may decide to raise docks

are blocked. Similarly, berths can accommodate or relocate facilities offshore. Connecting modes, such

emergency vessels and personnel, as was observed in as on-dock rail and service roads, would similarly need

2020 when the 1,000-bed hospital ship USNS Comfort updates to continue providing access to ports. Some

docked at Port 90 in Manhattan to serve patients limited investments are being made today to head off

during the COVID-19 crisis.27 Ports are also able to potential complications of sea level rise. The Port of

support force deployment in the instance homeland Virginia, for example, is spending $375 million to raise

protection is needed. Nine federal agencies, including their power stations several feet off the ground and

the U.S. Army, U.S. Army Corps of Engineers, and position their data servers as far inland as possible.29

the Maritime Administration work together to ensure

preparedness for national defense emergencies.28

Photo courtesy of Illinois Ports Association

SENECA REGIONAL PORT ON THE ILLINOIS RIVER

INNOVATION

In the U.S., the Ports of Long Beach and Los Angeles through open-sourced platforms can improve

each have one fully automated terminal. Three semi- efficiencies at ports. Such benefits are already being

automated terminals can be found in Virginia and New realized abroad.32 Advanced analytics also aid ports

Jersey.30 Automation stands to add throughput capacity in becoming more resilient as predictive approaches

and provide safety benefits.31 driven by machine learning ensure flexible, responsive,

and adaptive management amid highly complex and

Advanced analytics, such as blockchain, use existing

dynamic scenarios.

and historic data collected with devices and sensors,

86

________

2021 INFRASTRUCTURE REPORT CARD

www.infrastructurereportcard.org

RECOMMENDATIONS

TO RAISE THE GRADE

· Remove the multimodal cap on INFRA funds and increase overall investment in the

Ports INFRA and BUILD programs to ensure ports can effectively distribute and receive

goods as ships continue to grow in size.

· Appropriate funds to the Congressionally authorized projects to ensure that projects

crucial to freight movement are completed in a timely manner.

· Adopt new technologies to reduce wait times at docks, boost efficiency, improve

resilience, and increase security.

· Improve freight and landside connections to strengthen the entire freight system

and reduce congestion that is costly to the economy when moving goods.

· Ensure that ports are a part of comprehensive disaster planning. Ports play a critical

role in the aftermath of a disaster, facilitating the movement of people and the

delivery of supplies. Integrating ports into a holistic disaster recovery plan — one

that is developed with all stakeholders and is based on the data and data sharing — is

vital to ensuring a community can quickly recover.

· Port owners and operators should utilize asset management to prioritize limited

funding and pinpoint needed repairs.

· Ensure smaller ports can compete in existing and new competitive grant programs.

· Spend down the balance of the Harbor Maintenance Trust Fund on port projects.

87

________

2021 INFRASTRUCTURE REPORT CARD

www.infrastructurereportcard.org

SOURCES

1. U.S. Department of Transportation, Maritime Administration, “Ports,” accessed

September 29, 2020.

Ports 2. American Association of Port Authorities, “2018 National Economic Impact of the

U.S. Coastal Port System,” March 2019.

3. U.S. Environmental Protection Agency, “Ports Primer 3.1 Port Operations,”

accessed September 29, 2020.

4. American Association of Port Authorities, “Seaport Governance in the United

States and Canada,” February 2012.

5. Bipartisan Policy Center, “A Deep Dive on America’s Ports,” July 2017.

6. Valdez B, Ramirez J, Eliezer A, Schorr M, Ramos R & Salinas R, Journal of Marine

Engineering & Technology, “Corrosion assessment of infrastructure assets in coastal

seas,” 2016, 15:3, 124-134. DOI: 10.1080/20464177.2016.1247635

7. Margaronis S, American Journal of Transportation, “Port of Oakland Welcomes

19,200 TEU MSC Anna, one of the largest container ships to call North America,”

April 17, 2020.

8. U.S. Department of Transportation, Bureau of Transportation Statistics, “Port

Performance Freight Statistics in 2019: Annual Report to Congress 2020,”

January 2021.

9. U.S. Department of Transportation, Bureau of Transportation Statistics, “Port

Performance Freight Statistics in 2019: Annual Report to Congress 2020,”

January 2021, page 26.

10. U.S. Department of Transportation, Bureau of Transportation Statistics, “Port

Performance Freight Statistics in 2019: Annual Report to Congress 2020,”

January 2021, page 28.

11. U.S. Department of Transportation, Bureau of Transportation Statistics, “Port

Performance Freight Statistics in 2019: Annual Report to Congress 2020,”

January 2021, page 27.

12. U.S. Department of Transportation, Federal Highway Administration, Freight

Management and Operations, “Freight Intermodal Connectors Study, Chapter 6.

Summary of Key Findings and Options for Future Research.” April 2017.

13. Congressional Research Service, “Water Resources Development Act of 2020,”

updated January 5, 2021.

14. American Society of Civil Engineers calculations.

15. ASCE internal analysis.

16. Davis J, Eno Center for Transportation, “DOT Announces $1.5 Billion in BUILD

Surface Transportation Grants,” December 11, 2018.

88

________

2021 INFRASTRUCTURE REPORT CARD

www.infrastructurereportcard.org

SOURCES (Cont.)

17. U.S. Department of Transportation, “Maritime Administration Announces More

Than $280 Million in Grants for Nation’s Ports.” U.S. DOT Maritime Administration,

February 14, 2020, press release.

Ports

18. U.S. Department of Transportation, “U.S. Transportation Secretary Elaine L. Chao

Announces Over $220 Million in Grants for America’s Ports,” October 15, 2020,

press release.

19. Florida Department of Transportation, “FSTED Program.”

20. Minnesota Department of Transportation, “Port Development Assistance Program.”

21. Missouri Department of Transportation, “Freight Enhancement Program (FRE).”

22. Virginia Department of Transportation, “Virginia Transportation Funding.”

23. American Association of Port Authorities, “Results of AAPA’s Port Planned

Infrastructure Investment Survey,” April 30, 2020.

24. American Society of Civil Engineers, “Ports and Inland Waterways: Anchoring the

U.S. Economy,” January 2021.

25. American Association of Port Authorities, “2018 National Economic Impact of the

U.S. Coastal Port System,” March 2019.

26. U.S. Department of Transportation, Maritime Administration, Office of Ports

& Waterways, “Risk-Based Lifecycle Management of In-Water Structures,”

presentation given at American Association of Port Authorities Facilities Engineering

Seminar, April 2019.

27. U.S. Army Corps of Engineers, “USNS COMFORT Arrives in New York in Support

of COVID-19 Response Efforts,” Washington Headquarters Services, U.S. Military,

press release, March 30, 2020.

28. U.S. Department of Transportation, Maritime Administration, “National Port

Readiness Network (NPRN),” accessed September 30, 2020.

29. Phillips E, Wall Street Journal, “At the Water’s Edge, Seaports Are Slowly Bracing for

Rising Ocean Levels,” February 11, 2019.

30. Mongelluzzo B, Journal of Commerce, “More North American port automation

expected,” July 4, 2019.

31. Leonard M, Supply Chain Dive, “Brief: Moody’s: With port automation comes

political risk.” June 27, 2019.

32. Port of Rotterdam, Carbon Neutral in 3 Steps, accessed September 29, 2020.

89

________

2021 INFRASTRUCTURE REPORT CARD

www.infrastructurereportcard.org

You might also like

- Literature Survey Port OperationsDocument14 pagesLiterature Survey Port Operationspragya89No ratings yet

- Economic Issues of Proposed Arena: Prepared ForDocument8 pagesEconomic Issues of Proposed Arena: Prepared ForMatt DriscollNo ratings yet

- ASCE Failure To Act Ports Report FINALDocument48 pagesASCE Failure To Act Ports Report FINALMichael RojasNo ratings yet

- GLobal Trade Magazine June 2021Document14 pagesGLobal Trade Magazine June 2021AditNo ratings yet

- Maritime Port Network Resiliency and Reliability ThroughDocument17 pagesMaritime Port Network Resiliency and Reliability Throughfabricioace1978No ratings yet

- Disadvantage of Water TransportationDocument20 pagesDisadvantage of Water TransportationCouncil of Tourism StudentsNo ratings yet

- Chapter 2 MonjardinDocument9 pagesChapter 2 MonjardinPyron Ed Daniel SamaritaNo ratings yet

- Research Report Updated PDFDocument24 pagesResearch Report Updated PDFkunalsukhija21No ratings yet

- Port Competition Revisited: Hilde Meersman, Eddy Van de Voorde & Thierry VanelslanderDocument23 pagesPort Competition Revisited: Hilde Meersman, Eddy Van de Voorde & Thierry VanelslanderPhileas FoggNo ratings yet

- 5-Analysis of The CompetitionDocument9 pages5-Analysis of The CompetitionSidhant NarangNo ratings yet

- Inland Waterways 2021Document9 pagesInland Waterways 2021Qoyyum RachmaliaNo ratings yet

- Alternative Sea and Land-Bridges in Central AmericaDocument7 pagesAlternative Sea and Land-Bridges in Central AmericashannonNo ratings yet

- Hinterland ConceptDocument39 pagesHinterland ConceptChairunnisa MappangaraNo ratings yet

- Bangladesh Waterways AssessmentDocument24 pagesBangladesh Waterways AssessmentRAJIB DEBNATHNo ratings yet

- Competition Excess Capacity and The PriceDocument25 pagesCompetition Excess Capacity and The PriceAli Raza HanjraNo ratings yet

- The Insertion of A Satellite Terminal in Port Operations - Port Economics, Management and PolicyDocument5 pagesThe Insertion of A Satellite Terminal in Port Operations - Port Economics, Management and PolicymerrwonNo ratings yet

- Research in Transportation Business & Management: Yuhong Wang, Jason Monios, Mengjie ZhangDocument10 pagesResearch in Transportation Business & Management: Yuhong Wang, Jason Monios, Mengjie ZhangAntonio Carlos RodriguesNo ratings yet

- Submarine Cables: Critical Infrastructure For Global CommunicationsDocument11 pagesSubmarine Cables: Critical Infrastructure For Global CommunicationsvipskulangelNo ratings yet

- What Are The Trends in Liner Shipping Industry in 2022Document6 pagesWhat Are The Trends in Liner Shipping Industry in 2022Sanskrita VermaNo ratings yet

- AMEGA - Project Teaser - Jun 17Document2 pagesAMEGA - Project Teaser - Jun 17turbo111No ratings yet

- Transportation Engineering Assignment No. 2Document3 pagesTransportation Engineering Assignment No. 2Rona Mae GabogenNo ratings yet

- Design of Alternative Warehouse LayoutDocument8 pagesDesign of Alternative Warehouse LayoutrajkumarNo ratings yet

- PortMiami EPA Shore Power Project Application - 3.16.21Document47 pagesPortMiami EPA Shore Power Project Application - 3.16.21Miami HeraldNo ratings yet

- PROJECT REPORT - International Container Transhipment TerminalDocument83 pagesPROJECT REPORT - International Container Transhipment TerminalBibin Babu50% (2)

- Rajesh RA3 Q5 AssessedDocument6 pagesRajesh RA3 Q5 AssessedLogesh RajNo ratings yet

- Preparing For The Port of The FutureDocument12 pagesPreparing For The Port of The FutureB SNo ratings yet

- Transportation and Freight ReportDocument30 pagesTransportation and Freight ReportbernardngyijieNo ratings yet

- C1mem42019 10 Williams-RichardsDocument26 pagesC1mem42019 10 Williams-RichardsKacper KonopaNo ratings yet

- Gulftainer's PowerPoint Presented To JaxPort Officials in MarchDocument55 pagesGulftainer's PowerPoint Presented To JaxPort Officials in MarchThe Florida Times-UnionNo ratings yet

- Inland Waterways and The Global Supply ChainDocument24 pagesInland Waterways and The Global Supply ChainBambang Setiawan MNo ratings yet

- Logi 1Document12 pagesLogi 1DanielaAndreaRoldanNo ratings yet

- Smart Ports Web Version PDFDocument58 pagesSmart Ports Web Version PDFvelisbarNo ratings yet

- Ogola Daniel Bekesuomowei 01Document11 pagesOgola Daniel Bekesuomowei 01OGOLA DANIEL BNo ratings yet

- Automation of The Road Gate of An Inland Container DepotDocument18 pagesAutomation of The Road Gate of An Inland Container DepotjeevanNo ratings yet

- Transportation Research Part A: Wenjie Li, Ali Asadabadi, Elise Miller-HooksDocument23 pagesTransportation Research Part A: Wenjie Li, Ali Asadabadi, Elise Miller-HooksIrfan AkbarNo ratings yet

- Role of Ports in The 21st CenturyDocument47 pagesRole of Ports in The 21st CenturyknowsieybearNo ratings yet

- Daniel Alejandro Baena Piña Port Management Final Exam MAY-2020Document6 pagesDaniel Alejandro Baena Piña Port Management Final Exam MAY-2020Brayan Javier Castro CedeñoNo ratings yet

- Chapter 1 - IntroductionDocument7 pagesChapter 1 - IntroductionokongaonakNo ratings yet

- Port Performance IndicatorsDocument20 pagesPort Performance IndicatorsPMA Vepery100% (1)

- Papers On Port AutomationDocument22 pagesPapers On Port AutomationSrikanth DixitNo ratings yet

- Review of Maritime Transport 2021-1-30-19-24Document6 pagesReview of Maritime Transport 2021-1-30-19-24alin grecuNo ratings yet

- BPA Terminal Velocity Mar 2022Document18 pagesBPA Terminal Velocity Mar 2022mow_roNo ratings yet

- Maritime in MyanmarDocument5 pagesMaritime in MyanmarHein Thaw100% (1)

- TN JPR Krihs Paper 2Document27 pagesTN JPR Krihs Paper 2Lee YqNo ratings yet

- Thesis Title Related To Marine TransportationDocument8 pagesThesis Title Related To Marine Transportationbser9zca100% (2)

- Introduction in Port ManagementDocument41 pagesIntroduction in Port ManagementAlifa Alma Adlina75% (4)

- Letter From Ports of LA and Long Beach To California Air Resources BoardDocument5 pagesLetter From Ports of LA and Long Beach To California Air Resources BoardThe Press-Enterprise / pressenterprise.comNo ratings yet

- Port Management Is TheDocument2 pagesPort Management Is TheAnonymous Hd3sjEZNNo ratings yet

- Individual Assignment 3 - 04211841000015 - Raka Adhwa Ardhya MaharikaDocument11 pagesIndividual Assignment 3 - 04211841000015 - Raka Adhwa Ardhya MaharikaRaka Adhwa MaharikaNo ratings yet

- The Requirement For Hydrographic Surveys in Ports and AnchoragesDocument12 pagesThe Requirement For Hydrographic Surveys in Ports and AnchoragesSameer AnjumNo ratings yet

- ESCO India China BangladeshDocument8 pagesESCO India China Bangladeshmbacrack2No ratings yet

- Availability Payment - PortDocument11 pagesAvailability Payment - PortrachmanmuhammadariefNo ratings yet

- Port PlanningDocument58 pagesPort PlanningGenki Diy100% (1)

- The Role of Private Off Dock Terminals On Port Efficiency (A Study of Sifax Off Dock Nig, LTD.)Document11 pagesThe Role of Private Off Dock Terminals On Port Efficiency (A Study of Sifax Off Dock Nig, LTD.)IJEMR JournalNo ratings yet

- Inter-Modal Transport Terminal: Research No.2Document13 pagesInter-Modal Transport Terminal: Research No.2mark josephNo ratings yet

- An Assessment of Maritime Transport Facilities Along The Fako Coastal Belt of CameroonDocument12 pagesAn Assessment of Maritime Transport Facilities Along The Fako Coastal Belt of CameroonInternational Journal of Innovative Science and Research Technology100% (1)

- Inland Waterways Infrastructure and FundingDocument1 pageInland Waterways Infrastructure and Fundingahong100No ratings yet

- (P) Massive Traffic Jam at Ports, How To Unclog Logistics chain-WARTSILADocument18 pages(P) Massive Traffic Jam at Ports, How To Unclog Logistics chain-WARTSILAHilna I'anatul SyavillaNo ratings yet

- Course Handout: Personal Safety and Social ResponsibilityDocument86 pagesCourse Handout: Personal Safety and Social Responsibilityiftakhar oma100% (1)

- Concrete Gravity PlatformsDocument16 pagesConcrete Gravity PlatformsDavid J100% (1)

- D IV SMT III - Kecakapan Bahari Sesi 1 - Anchor ArrangementsDocument17 pagesD IV SMT III - Kecakapan Bahari Sesi 1 - Anchor ArrangementsWeslyNo ratings yet

- M&O Charts and Publications DepartmentDocument3 pagesM&O Charts and Publications DepartmentKing KingNo ratings yet

- Crane SynopsisDocument17 pagesCrane Synopsisgsrawat123No ratings yet

- Coating Performance Standard (CPS) : Guide For The Class NotationDocument11 pagesCoating Performance Standard (CPS) : Guide For The Class NotationGilberto Zamudio100% (1)

- Cas Vs CapDocument3 pagesCas Vs Capcc100% (1)

- Tips and Tactics Ship DesignDocument2 pagesTips and Tactics Ship DesignSW-FanNo ratings yet

- 4 Matching QuestionsDocument27 pages4 Matching QuestionsAshok YNo ratings yet

- The Use of Visual Aids To Navigation v5Document78 pagesThe Use of Visual Aids To Navigation v5Xue Feng Du100% (1)

- Wardiaryofadmir194142germ 1. CiltDocument354 pagesWardiaryofadmir194142germ 1. CiltZafer CandemirNo ratings yet

- Analysis of The Philippine Transportation SystemDocument15 pagesAnalysis of The Philippine Transportation Systemallen2912No ratings yet

- (30 Questions) Word Problems Part 2Document20 pages(30 Questions) Word Problems Part 2Steffi ClaroNo ratings yet

- Fasilitas Pelabuhan Dan FungsinyaDocument98 pagesFasilitas Pelabuhan Dan FungsinyaDiego Maradona MahardutaNo ratings yet

- Engexam - info-FCE Listening Practice Test 3Document6 pagesEngexam - info-FCE Listening Practice Test 3Lâm DuyNo ratings yet

- Tanker Pacific, Singapore: OdessaDocument45 pagesTanker Pacific, Singapore: OdessaOnofrei GabrielNo ratings yet

- Types of Ship and Port Material Handling Equipment & TechnologyDocument36 pagesTypes of Ship and Port Material Handling Equipment & TechnologyKaren Shui100% (20)

- Mobile Suit Gundam Vol. 2 - EscalationDocument91 pagesMobile Suit Gundam Vol. 2 - EscalationThịnh LưuNo ratings yet

- Kendriya Vidyalaya Air Force Station, Ojhar Question Bank Term Ii 2020-21 Name of Student: - Class: V Subject - EnglishDocument84 pagesKendriya Vidyalaya Air Force Station, Ojhar Question Bank Term Ii 2020-21 Name of Student: - Class: V Subject - EnglishRamLalJatNo ratings yet

- Adelantamiento de FloridaDocument442 pagesAdelantamiento de FloridacalianiNo ratings yet

- In Coastal Shipping: A Leading Multimodal PlayerDocument6 pagesIn Coastal Shipping: A Leading Multimodal PlayersrikumarNo ratings yet

- Topic 3Document21 pagesTopic 3Ivan SimonNo ratings yet

- Travel, Trip, Journey PDFDocument3 pagesTravel, Trip, Journey PDFjojibaNo ratings yet

- Mofazzal CV - 2019 Update PDFDocument3 pagesMofazzal CV - 2019 Update PDFGusti Ryandi AriefNo ratings yet

- Damen Interceptor 1503Document2 pagesDamen Interceptor 1503Hendi HendriansyahNo ratings yet

- Orthotropic Steel Deck Box Girder FabricationDocument9 pagesOrthotropic Steel Deck Box Girder FabricationIndra MishraNo ratings yet

- Name of Ship / Flag: Srikandi Indonesia / IndonesiaDocument4 pagesName of Ship / Flag: Srikandi Indonesia / IndonesiaJoy Mitrady PanjaitanNo ratings yet

- Solutions: Grain CargoesDocument3 pagesSolutions: Grain CargoesKirtishbose Chowdhury100% (1)

- Coal Terminal Information at Nacala-a-VelhaDocument9 pagesCoal Terminal Information at Nacala-a-Velhabob sapriNo ratings yet

- Grade 11 - Summative 2 (Gulshan Anar) - 1Document2 pagesGrade 11 - Summative 2 (Gulshan Anar) - 1Asiyat PachalovaNo ratings yet

- The Power of Our Supreme Court: How Supreme Court Cases Shape DemocracyFrom EverandThe Power of Our Supreme Court: How Supreme Court Cases Shape DemocracyRating: 5 out of 5 stars5/5 (2)

- A Student's Guide to Law School: What Counts, What Helps, and What MattersFrom EverandA Student's Guide to Law School: What Counts, What Helps, and What MattersRating: 5 out of 5 stars5/5 (4)

- Dictionary of Legal Terms: Definitions and Explanations for Non-LawyersFrom EverandDictionary of Legal Terms: Definitions and Explanations for Non-LawyersRating: 5 out of 5 stars5/5 (2)

- Essential Guide to Workplace Investigations, The: A Step-By-Step Guide to Handling Employee Complaints & ProblemsFrom EverandEssential Guide to Workplace Investigations, The: A Step-By-Step Guide to Handling Employee Complaints & ProblemsRating: 3 out of 5 stars3/5 (2)

- Legal Writing in Plain English: A Text with ExercisesFrom EverandLegal Writing in Plain English: A Text with ExercisesRating: 3 out of 5 stars3/5 (2)

- Admissibility of Expert Witness TestimonyFrom EverandAdmissibility of Expert Witness TestimonyRating: 5 out of 5 stars5/5 (1)

- Torts: QuickStudy Laminated Reference GuideFrom EverandTorts: QuickStudy Laminated Reference GuideRating: 5 out of 5 stars5/5 (1)

- Commentaries on the Laws of England, Volume 1: A Facsimile of the First Edition of 1765-1769From EverandCommentaries on the Laws of England, Volume 1: A Facsimile of the First Edition of 1765-1769Rating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (6)

- Legal Forms for Starting & Running a Small Business: 65 Essential Agreements, Contracts, Leases & LettersFrom EverandLegal Forms for Starting & Running a Small Business: 65 Essential Agreements, Contracts, Leases & LettersNo ratings yet

- Employment Law: a Quickstudy Digital Law ReferenceFrom EverandEmployment Law: a Quickstudy Digital Law ReferenceRating: 1 out of 5 stars1/5 (1)

- How to Make Patent Drawings: Save Thousands of Dollars and Do It With a Camera and Computer!From EverandHow to Make Patent Drawings: Save Thousands of Dollars and Do It With a Camera and Computer!Rating: 5 out of 5 stars5/5 (1)

- Nolo's Deposition Handbook: The Essential Guide for Anyone Facing or Conducting a DepositionFrom EverandNolo's Deposition Handbook: The Essential Guide for Anyone Facing or Conducting a DepositionRating: 5 out of 5 stars5/5 (1)

- Legal Guide for Starting & Running a Small BusinessFrom EverandLegal Guide for Starting & Running a Small BusinessRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (9)

- Flora and Vegetation of Bali Indonesia: An Illustrated Field GuideFrom EverandFlora and Vegetation of Bali Indonesia: An Illustrated Field GuideRating: 5 out of 5 stars5/5 (2)

- So You Want to be a Lawyer: The Ultimate Guide to Getting into and Succeeding in Law SchoolFrom EverandSo You Want to be a Lawyer: The Ultimate Guide to Getting into and Succeeding in Law SchoolNo ratings yet

- Solve Your Money Troubles: Strategies to Get Out of Debt and Stay That WayFrom EverandSolve Your Money Troubles: Strategies to Get Out of Debt and Stay That WayRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (8)

- Legal Writing in Plain English, Third Edition: A Text with ExercisesFrom EverandLegal Writing in Plain English, Third Edition: A Text with ExercisesNo ratings yet